?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

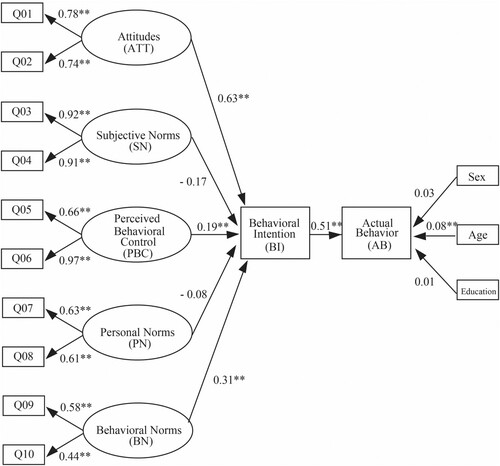

Cities worldwide have introduced or revived light rail transit (LRT) to develop compact city strategies and help address environmental issues, such as increasing CO2 emissions or air pollution. Toyama is such a city that has addressed these issues by establishing a compact city rooted in transportation policies, notably the LRT established in 2006. Although there appears to be a consensus that the LRT contributes to establishing a compact city, contributing factors to ridership remain unclear. This study attempts to identify these factors, using the norm-activation model and theory of planned behaviour as a theoretical grounding, questionnaires for a data collection method and structural equation modelling for data analysis. The findings suggest that attitudes, perceived behavioural control and behavioural norms are significantly associated with the intention to use the LRT, which is, along with age, associated with its actual use. Based on these findings, this study provides theoretical and practical insights for cities wanting to pursue establishing or developing an LRT system.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cities worldwide have introduced or revived light rail transit (LRT) to develop compact city strategies and help address environmental issues such as increasing CO2 emissions or air pollutions (Jaroszynski & Brown, Citation2014; Levinson et al., Citation2012; Novales & Conles, Citation2012; Vigrass & Smith, Citation2005). Such examples include Calgary in Canada (O’Sullivan & Morrall, Citation1996), Denver (Bhattacharjee & Goetz, Citation2012) and Portland (Dueker & Bianco, Citation1999; Thompson, Citation2007) in the United States, Grenoble in France (Denant-Boèmont & Mills, Citation1999), and many other cities (Addie et al., Citation2020; Carpintero & Siemiatycki, Citation2016; Hurst & West, Citation2014; Priemus & Konings, Citation2001).

Denant-Boèmont and Mills (Citation1999) note that ‘there has been a renaissance in light rail, probably motivated by municipal desires for environmental improvement’ (p. 242), as LRT may emit less CO2 and alleviate air pollution by reducing congestion and increase accessibility. This is not only because LRT runs with electricity and thus is more environmentally friendly, but also because it serves for the coordination of urban transport services that may help promote public transportation use and establish compact cities (le Clercq & de Vries, Citation2000; Sakamoto et al., Citation2018; Vigrass & Smith, Citation2005). According to Topalovic et al. (Citation2012), for example, one of the largest benefits of LRT over other transportation modes is that ‘it is an integral component of TOD [transit-oriented development], mixed-use development policies and walkable cityscape design’ (p. 338). LRT may encourage urban growth, mixed-use development, intensification of high densities and revitalization of downtown areas (Cervero & Sullian, Citation2011) through ‘an increase in shopping commerce generated adjacent to the transit line, development of new residential and commercial areas and increased employment nodes’ (Topalovic et al., Citation2012, p. 333). These are the characteristics of compact cities.

Compact cities are defined as high-density urban development and mixed-use cities based on an energy-efficient public transportation system with easy access to local services and employment (Lewis, Citation2014), which discourages private cars and helps reduce fossil fuel emissions (Mouratidis, Citation2018). According to Basu and Ferreira (Citation2021), spatial mismatch, through public transportation catchment points far from home and workplaces, contributes to private car use. Because many industries are far from public transportation catchment areas, there are few opportunities to enter the labour market without a car. Compact city strategies address these issues primarily by strengthening urban intensification and establishing public transportation systems (Mahieux & Mejia-Dorantes, Citation2017).

Compact city strategies are more successful once strong transportation networks are established, with coordinated trains, trams, and buses (Jaroszynski & Brown, Citation2014). LRT may ‘function as a backbone around which other transit services were organized’ (Jaroszynski & Brown, Citation2014, p. 50), while access to LRT is a significant land-use benefit for compact city development (Dueker & Bianco, 1999) because the accessibility of LRT can ‘help increase ridership, therefore catalyzing for redevelopment in selected areas’ (Topalovic et al., Citation2012, p. 333). In addition, Scherer (Citation2010) noted that LRT is favoured by the public over existing public transportation services because of positively perceived features compared with other public transportation modes, such as new and modern designs, visibility, media presence, improved reliability, and comfort. Hence, LRT can play an important role in establishing a compact city.

Despite the importance of LRT in developing a compact city, factors that contribute to LRT ridership have been understudied compared with those of other transportation modes. This study aims to narrow this research gap by analysing citizens’ intention to use and actual use of the LRT in Toyama City using the norm-activation model (NAM) and theory of planned behaviour (TPB). These are two of the most used theories in transportation research because they holistically and comprehensively allow the analysis of psychological factors (i.e., attitudes, norms and perceived behavioural control) that influence intentions to use transportation modes (Bamberg et al., Citation2003, Citation2007; Donald et al., Citation2014; Wall et al., Citation2007). Findings from this study contribute to the existing NAM-TPB theoretical model to explain LRT ridership and provide decision-makers and transportation practitioners with implications, insights, and guidance for the advancement of compact city strategies and/or transportation policies based on LRT.

Toyama’s compact city strategies, rooted in robust transportation policies, notably LRT, are worthy of attention. The city was designated by the national government as an Eco-model city in 2008, an Eco-future city in 2011, and a Sustainable Development Goals Future City in 2018. As the national government sought to develop new plans to solve socio-environmental issues, Toyama City was adopted as a testing ground for national urban policies, including compact city development based on an LRT system. Furthermore, in 2012, Toyama City was selected by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as one of five exemplary cities with compact city policies. In 2014, it was selected as one of 13 model cities for the United Nations Sustainable Energy for All Initiative and was included in Rockefeller’s 100 Resilient Cities Program. In 2016, the city signed a memorandum of understanding with the World Bank for its partnership programme to realize compact city designs and meet the challenges of a rapidly ageing population. Hence, its compact city strategies, based on the well-coordinated transportation system featuring LRT, have been recognized both nationally and internationally.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. We first describe the development of Toyama City’s compact city design, with emphasis on the LRT. We then examine citizens’ intention to use and the actual use of the LRT through the constructs of the extended NAM and TPB. The findings may help policymakers and urban planners better understand citizens’ LRT use and thus elaborate on strategies to promote their LRT use. This study also examines sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., sex, age and education levels) and how these are attributed to or explain transportation behaviours (Chowdhury & Ceder, Citation2016). Notably, we will focus on the LRT because studies on other transportation modes, such as cars, trains, and buses, have widely been conducted but research focusing on the LRT ridership is still less common than the other transportation modes.

1.1. Toyama’s compact city strategies rooted in the LRT

Toyama City is located in the northern part of Honshu (Japan’s main island), with a population of 415,535 as of 2020 (Toyama City, Citation2021). The city faces socio-environmental problems, such as increased CO2 emissions and air pollution, which are partially attributed to increased private vehicle use and a decrease in the utilization of public transportation. The number of cars owned by Toyama citizens increased by 1.8 times from 138,102 in 1990 to 249,181 in 2005 (Toyama City, Citation2009). Simultaneously, between 1990 and 2006, the city experienced a reverse trend in public transportation usage corresponding to the growth in car ownership with a 33%, 47% and 46% decline in the number of passengers using the West Japan Railway line, private railway and trams, respectively. Buses experienced the most significant decline at nearly 70% during this period (Muro, Citation2009). At the turn of the century, Toyama City had become a predominantly car-dependent society (Shigetou, Citation2020).

Toyama City has been addressing these challenges through compact city strategies aimed at revitalizing urban transportation systems and concentrating city functions, such as commercial, recreational and residential facilities, in the city centre and near public transportation lines, with the most notable being those of the LRT system (Toyama City, Citation2017). To reinvigorate public transportation, Toyama City converted the old tram and train run by the JR Line into LRT in 2006, rendering them user-friendly transportation modes (Muro, Citation2009). Previously, the route distance of the JR West Toyamako Line was 8.0 km and service was provided only in the northern part of the city, with 10 stations and an hourly frequency. The city’s LRT now (as of 2022) comprises a 15 km-long, north–south running line, called Portram, which connects the oceanfront and city centre, and a city loop LRT line called Centram that allows passengers to travel around the city centre. The LRT’s frequency improved to every 10–15 min, whereas the number of stations has been increased to 15. The LRT is also connected to other tram, train and bus lines, creating a far-reaching network of different modes of public transportation, with Toyama Station acting as the main hub.

These integrated lines render the public transportation system convenient for citizens to commute and travel. After the establishment of the LRT and integrated public transportation system, there was a 110% increase in LRT ridership during weekdays and a 230% increase on weekends from 2005 to 2019, compared with the ridership of the former JR Line. Ridership increased by 2.4 times (Arai et al., Citation2020). The number of LRT passengers in their 60s and 70s also increased by 3.5 times compared with the former JR Line (Toyama City, Citation2021). This suggests that citizens, including the elderly, took the LRT more often, presumably because it is a more user-friendly street-level line with no barriers in stations and no elevated steps to enter the trams (Arai et al., Citation2020). Overall, the number of public transportation passengers increased by 15.7% between 2005 and 2018, possibly because of the effects of the LRT and integrated transportation system (Toyama City, Citation2021). However, although these compact city strategies rooted in robust transportation policies helped increase public transportation use and established Toyama as a compact city, the city still has disproportionately high private car dependency, and further promotion of the LRT and other public transportation modalities are thus essential. In this context, the current study investigates possible contributing factors to LRT ridership.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

To implement strategic transportation policies, it is essential to understand the psychological factors that influence human behaviour (Chowdhury & Ceder, Citation2016). For this study, we drew on NAM and TPB as theoretical frameworks because moral and attitudinal factors influence transportation behaviours in a compact city setting (Lewis, Citation2014). NAM and TPB, often combined, have been widely used for transportation behaviour research. For example, a study by Wall et al. (Citation2008) on the interactions between perceived behavioural control and personal-normative motives on travel-mode choice decisions applied both NAM and TPB. Bamberg et al. (Citation2007, Citation2011) studied transportation policy measures and employed a joint theory (i.e., NAM and TPB combined) to augment TPB by adding personal norms from NAM as another determinant of intention. Donald et al. (Citation2014) also studied the psychological factors affecting commuters’ transport mode choice using TPB with personal norms (i.e., the central component of NAM).

TPB constructs are used to examine self-interested behaviour and do not capture the influence of moral elements, whereas NAM is used to examine pro-social behaviour and does not capture attitudinal constructs (Bamberg et al., Citation2007); therefore, it may be effective to combine both to understand and/or explain transportation behaviours (Bamberg et al., Citation2003; Citation2007; Donald et al., Citation2014; Donald & Cooper, Citation2001; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002; Wall et al., Citation2007).

2.1. Norm-activation model (NAM)

NAM presumes that individuals’ awareness of consequence and/or perceived responsibility forms personal norms that may influence their decisions regarding transportation-mode use (Bamberg et al., Citation2011). Personal norms are defined as personalized feelings of obligation or moral responsibility (Donald & Cooper, Citation2001) and are often used to explain transportation behaviour (Bamberg et al., Citation2007; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002; Wall et al., Citation2008). According to a study by Steg and Vlek (Citation1997), car users who are more aware of environmental issues and their consequences feel more obliged to solve the problems caused by car use and reduce their car use. Steg et al.’s (Citation2001) study also showed that awareness of the problems caused by car use significantly influenced actual car use. This was assumed to be because of individuals learning of consequences or feeling moral obligation, causing them to reassess the need or want for their actions. Furthermore, ‘individuals concerned about the environment and who, therefore, wanted to reduce private car use were more likely to reside in high-density neighborhoods in downtown areas’ (Lin, Wang, & Guan, Citation2017, p. 112) and tended to use public transportation modes (Donald et al., Citation2014; Bamberg et al., Citation2007). However, people also deny responsibility when an action is inconvenient or difficult, as it is out of their control (Wall et al., Citation2008). For instance, people who drive private cars state that they have little or no means of public transportation available near their residence or workplace. That is, personal norms alone cannot explain certain transportation behaviours (Heath & Gifford, Citation2002).

2.2. Theory of planned behaviour (TPB)

The TPB presumes that intention to perform behaviours can be predicted from (1) attitudes toward, (2) subjective norms of, and (3) perceived behavioural control over a certain behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). TPB variables are assumed to influence transportation use through their effect on people’s usage intention (Donald et al., Citation2014; Egset & Nordfjærn, Citation2019). Attitudes refer to one’s positive or negative feelings or images about a certain behaviour and their affective evaluations that determine their transportation behaviour (Arroyo et al., Citation2020; Beck & Rose, Citation2016; Haustein, Citation2012). The more favourable an individuals’ attitude is toward a certain transportation mode, the higher their intention to use it is (de Oña et al., Citation2021). Whether an individual’s attitude toward a transportation mode is positive or negative depends on factors such as accessibility, availability, comfort, convenience, flexibility, independence, speed, reliability, safety and control (Beck & Rose, Citation2016; Steg, Citation2003).

Perceived behavioural control refers to one’s perception of the ease or difficulty of adopting a behaviour of interest (Ajzen, Citation1991). This includes perceived self-efficacy (the ability to perform a certain behaviour) and perceived controllability (the extent of control to perform a behaviour) (Ajzen, Citation2002). In transportation research, it measures an individual’s perceived ease or difficulty in using a particular mode of transportation and the extent to which they feel restricted in autonomously executing their choice with regard to using the transportation mode (Haustein, Citation2012). For example, time, costs, skills and compatibility with others may influence one’s perceptions of what they can and cannot do; this choice can be made based on the travel distances between their catchment points and homes, workplaces, and other destinations (Clark et al., Citation2016) and the importance of other needs such as carrying heavy loads, making business trips, and taking children to school (Beirão & Cabral, Citation2007; Thøgersen, Citation2014). Subjective norms refer to perceived social approval or disapproval, for example, from family members or friends, of a given behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002; Manstead, Citation2011). They reflect individuals’ motivated action because of the social rewards and punishments associated with the behaviour (Smith et al., Citation2012) and are what should be done injunctively (Demarque et al., Citation2015; Forward, Citation2009). Subjective norms also influence how ‘favourable’ (attitudes) and ‘easy’ (control) the behaviour would be to use transportation modes (Bamberg et al., Citation2007) – attitudes, perceived behavioural control, and subjective norms can influence each other. For instance, if individuals perceive that their personal networks find it favourable or easy to use a certain transportation mode, they may also develop similar opinions toward it (Ababio-Donkor et al., Citation2020).

2.3. Behavioural norms

Besides the original constructs in the NAM and TPB models, behavioural norms were added to the current study because they are considered a significant predictor of the choice of transportation modes (Demarque et al., Citation2015; Eriksson & Forward, Citation2011; Waddell & Wiener, Citation2014). Behavioural norms refer to the perception of what most individuals would do in a given situation (Heath & Gifford, Citation2002) or their personal networks’ behaviours (Rivis & Sheeran, Citation2003) and may be more influential than subjective norms in enabling a certain behaviour (Anable, Citation2005; Eriksson & Forward, Citation2011; Forward, 2009). They can motivate action by informing people about what is likely to be beneficial transportation behaviour (Smith et al., Citation2012). It may thus be more effective to use both behavioural and subjective norms as bases for influencing behaviour rather than either alone (Smith et al., Citation2012) because behavioural and subjective norms are conceptually distinct (Rivis & Sheeran, Citation2003). Newer studies on the TPB also acknowledge the effect of behavioural norms (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation2005; Forward, 2009; Smith et al., Citation2012). Behavioural norms have also proven to be effective in changing transportation behaviour (Demarque et al., Citation2015; Kormos et al., Citation2015; Namgung & Akar, 2014; Waddell & Wiener, Citation2014). For instance, Eriksson and Forward (Citation2011) showed that the addition of behavioural norms increased TPB’s predictive power of public transportation use. Heath and Gifford (Citation2002) also suggested that behavioural norms significantly explain bus use.

3. METHODOLOGY

The current research employs a survey study. Surveys are generally designed to collect data at a point in time, as is the case with the current study. They are useful in gathering data on attitudes and behaviour on a one-shot basis, which can be analysed statistically, representing a wide target population, and providing descriptive, inferential, and explanatory information (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Citation2011).

3.1. Methods and sampling

A survey based on a self-administered online questionnaire was conducted by a research company called Intage (Tokyo, Japan), which owns a database of over 10 million potential respondents recruited through online advertisements. The subjects were those who registered in the data base and responded to the questionnaire (see Appendix A in the online supplemental data). In Toyama City, over 80% of all citizens live in the city centre, which comprises eight residential areas. Citizens from each area were surveyed in September 2020. Before conducting the survey, we obtained ethics approval from our home university. The survey was provided with a consent form to potential respondents in this study as part of a larger study, with the purpose of analysing Toyama citizens’ transportation behaviour, for example, LRT, in relation to socio-demographic and psychological factors, in the context of a compact city. It took a maximum of one hour to complete the questionnaire. We constructed the questionnaire based on the literature review and in consultation with the personnel from Intage. We received 961 responses, with a response rate of 14.7%. Efforts were made to normalize collected data to generate a geographically and sociodemographically representative sample (Mouratidis, Citation2018). Given that the populations and population densities of each area were not equal, we randomly selected samples from among the collected questionnaires, proportional to area population as of June 2020, to render the sample composition similar to the city population (see Appendix B in the online supplemental data). After this adjustment, we used a sample of 777 respondents, with the sample population proportional to that of the city’s districts.

3.2. Variables

There were two dependent variables: (1) actual behaviour, explained by behavioural intention and sociodemographic factors at the level of direct predictors, and (2) behavioural intention, explained by other independent variables at the level of indirect predictors. These independent variables include attitudes; perceived behavioural control; and subjective, behavioural, and personal norms (notably, behavioural intention is an independent variable in relation to actual behaviour, while it is a dependent variable in relation to attitudes; perceived behavioural control; and subjective, behavioural, and personal norms). In the extended NAM-TPB, it was hypothesized that respondents’ attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, personal norms, and behavioural norms led to actual behaviour through behavioural intention regarding future LRT use.

To examine actual behaviour, respondents were asked how often they used the LRT (Bamberg et al., Citation2007). Another question prompted respondents to clarify their intention to use the LRT (Heath & Gifford, Citation2002). Respondents were also asked to provide sociodemographic information (i.e., age, sex and educational level). Attitudes toward LRT use were measured using two questions about respondents’ perceptions on the use of and willingness to use LRT (Bamberg et al., Citation2007; Urbanek, Citation2021), measured on a seven-point Likert scale (−3 = extremely bad, to +3 = extremely good, with higher scores denoting a more favourable evaluation of a particular transportation mode; Donald et al., Citation2014). In addition, respondents were prompted to rate their perceived extent of control over the LRT use. Perceived behavioural control was assessed through two items: (1) distance between respondents’ homes and public transportation catchment points (Chowdhury & Ceder, Citation2016; Mouratidis, Citation2018), and (2) difficulty or ease of using the LRT for commuting (Bamberg et al., Citation2007; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002). These variables were measured on a seven-point Likert scale.

Three kinds of norms, namely subjective, behavioural, and personal norms, were examined. Subjective norms were measured by two items that asked respondents to rate, on a seven-point Likert scale, the extent to which most people significant to them (i.e., friends and family) think positively or negatively of using the LRT when commuting or going out (Donald et al., Citation2014; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002). Behavioural norms were measured using two items that asked about the frequency of LRT use among family and friends (Forward, 2009; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002). With the item for family members, each response was calculated by dividing the number of family members who reported taking the LRT by the total number of family members. The other item asked respondents to estimate the percentage of friends using public transportation to commute to school or work (Kormos et al., Citation2015) on a five-point Likert scale (1: 0–19%; 2: 20–39%; 3: 40–59%; 4: 60–79%; 5: 80–100%; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002). Personal norms were measured using two combined items regarding awareness of the consequences of and responsibility for the problems caused by car use (Anable, Citation2005; Donald et al., Citation2014; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002). Awareness of consequences was measured with one item that asked respondents to rate the extent of their agreement with a statement that described the environmental problems caused by car use on a seven-point Likert scale (Heath & Gifford, Citation2002). Perceived personal responsibility was measured using an item that asked respondents the extent of responsibility they felt for solving the problems caused by car use on a seven-point Likert scale (Heath & Gifford, Citation2002).

3.3. Data analysis

We first present a general description of sociodemographic factors (sex, age and education levels). As in previous transportation studies (Bamberg, Citation2006; Long et al., Citation2011), we used structural equation modelling comprising factor analysis and multiple regression, in which relations of seven variables, namely, attitudes, perceived behavioural control, subjective, personal, and behavioural norms, behavioural intention, and actual behaviour, were estimated.

For factor analysis, the following formula was used:

where xj is an observed variable, aj is a factor loading, fi is a common latent factor, and ej is an error term. The index j indicates each observed variable. The index i indicates each factor. Attitudes are indicated by ATT, subjective norms by SN, perceived behavioural control by PBC, personal norms by PN, behavioural norms by BN, behavioural intention by BI, and actual behaviour by AB.

For multiple regressions,

where b0 and c0 are constants, bp (p = 1, … , 5) and cq (q = 1, … , 5) are coefficients, and e11 and e12 are error terms of those regressions.

The recommended acceptance of the goodness-of-fit of a model with observed data requires that the obtained comparative fit index (CFI) value ranges from 0 to 1. For the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the obtained value was < 0.05, indicating a good fit. Values ranging from 0.08 to 0.10 indicate a mediocre fit, and those > 0.10 indicate a poor fit (Byrne, Citation2011). All data analyses were performed using Mplus software (Version 8.5, Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA).

4. RESULTS

presents descriptive statistics for all variables. shows that approximately 40% of respondents reported negative intention to use the LRT (17.6% + 12.6% + 11.3% = 41.5%), whereas one-third of respondents had positive intention (17.8% + 9.9% + 4.5% = 32.2%). However, slightly over 10% (6.4% + 1.9% + 2.3% = 10.6%) of respondents reported using the LRT at least once a month.

Table 1. Participants’ general demographics (n = 777)

Table 2. Behavioural intention and actual behaviours (n = 777)

depicts the results of the structural equation model with standardized path coefficients. There was a significant positive association between attitudes, perceived behavioural control and behavioural norms with behavioural intention to use the LRT, which was also significantly associated with the actual use of LRT. Conversely, subjective norms and personal norms were not significantly related to behavioural intention.

When standardized, behavioural intention and age have a significant positive association with actual behaviour at 0.51 and 0.09, respectively. The older the respondents, the more they used the LRT. Other sociodemographic variables were not significantly related to actual behaviour. This model provides a chi-square value of 365.208 with 73 degrees of freedom. The CFI value of 0.923 is a better range of the cut-off value of 0–1. The RMSEA value of 0.072 was lower than the upper limit of 0.10. Goodness-of-fit statistics indicate this model fits the data well.

5. DISCUSSION

Findings showed that attitudes, behavioural norms, and perceived behavioural control were significantly associated with behavioural intention to use the LRT. Behavioural intention is then, along with age, significantly associated with actual use. Considering these factors when elaborating on transportation policy strategies and interventions would therefore lead to further LRT use. In the following subsections, we will discuss theoretical and practical implications, which could be used by policymakers and urban planners aiming to promote LRT use.

5.1. Age

Age was the only significant sociodemographic factor in explaining actual LRT use. That is, older respondents tend to ride LRT compared with their younger cohorts. To promote public transportation use, some scholars have suggested targeting youths (e.g., Graham-Rowe et al., Citation2011). This strategy could be valuable in the context of Toyama City because older respondents already used LRT more than younger respondents. Another study on citizens’ car use in Toyama City also found that respondents with tertiary education had a higher tendency to drive cars (Ito & Kawazoe, Citation2022). This implies fewer opportunities to educate adult citizens about transportation choices after reaching adulthood. Moreover, young people may not be fully embedded into a car-centric lifestyle and would be more open to considering health and environmental issues, including those related to transportation modes (Wright & Egan, Citation2000). The behavioural norm–usage intention relationship could also be stronger among youths (Mahieux & Mejia-Dorantes, Citation2017) because of their need to gain peer acceptance (Rivis & Sheeran, Citation2003). For instance, Rivis and Sheeran (Citation2003) note that the intentions of young people are more strongly associated with their perceptions of others’ behaviour than the intentions of older people (p. 227), as children and young adults are more susceptible to social influence than older adults because of young people’s need to establish a self-identity. Policy interventions must therefore address youths receiving basic education. Since 2011, Toyama City has implemented vehicle story lessons to help children to understand vehicles used in a compact city, targeting elementary school students; however, similar educational programs should be extended to junior or senior high school students.

5.2. Attitudes

Similar to previous studies, attitudes were identified as a significant factor in predicting the intention to use public transportation modes (Arroyo et al., Citation2020; Beirão & Cabral, Citation2007; Haustein, Citation2012). Therefore, to promote public transportation use, policy makers should aim at improving the attitudes of citizens toward public transportation use (de Oña et al., Citation2021; Namgung & Akar, 2014). Beirão and Cabral (Citation2007) argue that policy interventions aimed at increasing public transportation use, including the use of the LRT, should influence attitudes by improving its image. As Ibraeva and de Sousa (Citation2014) note, compared with the public’s image of cars (e.g., fast, comfortable), that of public transportation is relatively poor (e.g., slow, uncomfortable). In particular, those who do not use public transportation tend to have a negative image of the public transportation service, perhaps because they are uninformed about it (Beirão & Cabral, Citation2007). To enhance the LRT ridership, one potential intervention is to temporarily offer free/discounted services (Bamberg, Citation2006; Beirão & Cabral, Citation2007; Cats et al., Citation2017; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002; Kormos et al., Citation2015). In the study by Heath and Gifford (Citation2002), ‘once participants begin to use the bus more often as a result of a U-pass [discounted pass] program, they develop less biased, more realistic perceptions of public transportation, and that beliefs about the outcome of using public transportation become more positive’ (p. 2179). In the case of the Netherlands, the provision of free public transportation services increased public transportation use from 11% to 21%, whereas in Tallin, Estonia, public transportation use increased by 14% (Cats et al., Citation2017). In Copenhagen, a free month-long travel card provided to car owners doubled their public transportation use. Thus, providing opportunities for non-public transportation users to try public transportation might help them realize their utility (Thøgersen, Citation2009). Another study on Toyama City’s transportation policies indicated that, as also noted by Scherer (Citation2010), respondents’ attitudes toward the LRT were more positive than toward other public transportation modes. This may be because Toyama City’s LRT has already developed these positive attributes and is an integrated public transportation system; however, there is room for improvement in terms of increasing ridership (Ito & Kawazoe, forthcoming). Toyama provided discounted fare services for one year after the introduction of the LRT, which appeared to help increase the number of passengers. The city should adopt this kind of free/discounted trial strategy periodically.

5.3. Behavioural norms

This study suggested the importance of adding behavioural norms to the TPB because these significantly improve its predictability, as also noted by Rex et al. (Citation2015). Therefore, the significant influence of behavioural norms has implications for the development of policy interventions. For instance, once individuals perceive that the people in their personal networks are regular public transportation users, they would regard this behaviour as ‘normal’ and would be more likely to use public transportation (Waddell & Wiener, Citation2014). Because the perception that other people use the LRT may positively influence citizens’ intention to use it, behavioural norms can create effective messages for the public. A commonly employed tactic in advertising campaigns is to emphasize the prevalence of a particular behaviour (Donald et al., Citation2014).

For example, a study by Goldstein et al. (Citation2008) reported that conveying a behavioural norm message to a hotel’s guests that nearly one-third of the guests reused towels resulted in a significantly higher towel reuse rate. In a compact city such as Toyama, citizens can see others riding the public transportation (notably the LRT, as it runs above the ground in the city centre and draws attention as modern and visible; Scherer, Citation2010), which may enhance behavioural norms to induce its use. Therefore, the establishment of a compact city itself serves as a springboard for public transportation promotion.

5.4. Perceived behavioural control

Our study identified perceived behavioural control as a significant factor in predicting the use of LRT. This finding is supported by Donald et al. (Citation2014) and Taube, Kibbe, Adler, and Kaiser (Citation2018). One possible explanation is that a compact city such as Toyama renders relative behavioural control to passengers with well-coordinated public transportation systems.

To change transportation behaviour, the physical and psychological costs of public transportation use (LRT in this case) need to be addressed because behaviour change is unlikely to occur unless citizens feel that they have control over the adoption of new behaviours (Rex et al., Citation2015). Therefore, facilitating the adoption of LRT by removing barriers related to the physical environment should precede interventions to influence psychological factors. If the transportation experience is negative, it will negatively influence psychological factors (Heath & Gifford, Citation2002). To address these points, enhancing (perceived) behavioural control is essential by establishing a conducive physical environment, including improved bicycle storage and free security marking; improved pedestrian access and street lightning; free parking for multiple-occupant cars; expansion of the car-share scheme to include a nearby hospital; and subsidized buses (Wall et al., Citation2008) as well as reducing the number of parking spaces, increasing parking costs, congestion changes, and bus lanes (Donald et al., Citation2014). In the case of Toyama. City, a well-integrated public transportation system, including LRT, in terms of network, fare, catchment points, and transfers, has been built based on compact city initiatives (Arai et al., Citation2020). It may be time for Toyama City to focus on soft policy measures (e.g., information dissemination).

5.5. Subjective norms

In the current study, subjective norms were found to be insignificant. Although this finding is supported by some previous studies (Donald & Cooper, Citation2001; Waddell & Wiener, Citation2014), other studies have claimed that subjective norms have a significant effect (Eriksson & Forward, Citation2011) and can increase efficacy in explaining transportation-mode choice, especially if subjective and behavioural norms are used together (Shi et al., Citation2017). For instance, Demarque et al. (Citation2015) note that subjective norms may be important as they complement behavioural norms in policy interventions, considering that a behavioural norm alone may lead to a normalization effect, wherein individuals move closer to the norm. In the case of transportation mode choice, depending on the prevailing norm, the presence of a behavioural norm about car-use alone may either prompt frequent car users to reduce driving or prompt infrequent car users to increase their car use. However, when a message communicating a subjective norm is conveyed along with that about a behavioural norm, infrequent car users may be influenced to continue their low car use. Therefore, subjective norms may be critical to supplement behavioural norms, especially in reducing car use, which may enhance public transportation ridership, including LRT (Wright & Egan, Citation2000). Given the findings of the current research that the Toyama’s LRT tends to be used less by younger than older people, the involvement of popular adolescents (e.g., influencers from Toyama) might positively influence subjective norms (Dijkstra et al., Citation2008). Thus, the city’s government could recruit influential adolescents to post positive comments, information, and experiences about the LRT on social networking sites to influence their peers.

5.6. Personal norms

Personal norms were not found to be significant in the current study. This finding contradicts those of some previous studies. For instance, Donald et al. (Citation2014) and Bamberg et al. (Citation2007) indicated that personal norms are a significant variable of public transportation-use intention. Zhang, Schmocker, Fujii, and Yang (Citation2016) also showed that personal norms were significantly associated with the intention to use public transportation. On the contrary, this finding – personal norms were insignificant – concurs with the results of some previous studies. For example, Beirão and Cabral (Citation2007) noted that environmental concerns regarding car use did not seem to matter in travel mode choices. This may in part be because the effects of personal norms can be moderated or nullified by other psychological constructs, such as perceived behavioural control (Bamberg et al., Citation2007). If individuals engage in certain actions, they may reassess and consider their physical and/or psychological costs. When these costs are perceived as too high, they may neutralize personal norms by denying the need or personal ability (Bamberg et al., Citation2007). For instance, drivers can claim that they have no public transportation available nearby (Bickerstaff & Walker, Citation2002) and justify the need to use cars (Wall et al., Citation2008). Therefore, policymakers should take measures to improve perceived behavioural control by making the LRT and other public transportation modes more practical (Bamberg, Citation2006) while reducing barriers to using them (Heath & Gifford, Citation2002; Mahieux & Mejia-Dorantes, Citation2017). Toyama City has achieved this with the establishment of the compact city based on the above-stated integrated transportation system; however, awareness of these qualities among the city’s residents may be lacking. To raise their awareness, soft policy measures such as policy campaigns with information dissemination with emphasis on the prevalence of LRT use or the involvement of local young influencers should be further implemented. Given that the constructs of TPB tend to be more influential than those of NAM in influencing the usage-intention of LRT, social marketing measures focused on self-interested motivations (e.g., providing free/discounted tickets) rather than pro-social ones (e.g., showing the images of negative consequences of car use) may be more effective in a compact city context.

5.7. Practical implications and transferability

The current research found attitudes, perceived behavioural control, and behavioural norms to be significant factors that explain the intention to use LRT, perhaps largely because of Toyama’s compact city characteristics, establishment, and provision of well-coordinated public transportation system, along with the concentration of city functions. By definition, a compact city with a well-coordinated public transportation system may provide citizens with behavioural control over public transportation use because many fundamental ‘human activities such as living, working, and shopping’ (Dieleman & Wegener, Citation2004, p. 310) can be performed in the city centre, mostly by sustainable transportation (e.g., public transportation, walking and cycling; Dieleman & Wegener, 2004). In addition, in a compact city, citizens have more opportunities to observe others using public transportation, notably LRT, than a non-compact city, which may in turn positively influence behavioural norms. These factors – perceived behavioural control and behavioural norms – may also help enhance positive attitudes toward public transportation usage. For instance, individuals may have more positive attitudes toward a certain behaviour if they feel that they have more control over the behaviour. Similarly, individuals may have more positive attitudes toward a certain behaviour if their personal networks exhibit the behaviour (Anable, Citation2005).

These findings indicate the importance of the provision of information about the practicality and prevalence of LRT to citizens to enhance positive attitudes toward its use, to positively influence behavioural norms, and to remove barriers impeding its use, thus increasing individuals’ perceptions of behavioural control. Individuals who do not use public transportation, including the LRT, have a negative image of it (Beirão & Cabral, Citation2007). Current research showed that nearly half of respondents never used the LRT, and only approximately one-third of respondents reported a positive intention to do so. Given that positive experiences with the service are more likely to enable people to have positive attitudes toward it, which is likely to lead to its continuous use (Beirão & Cabral, Citation2007), the experience of using the LRT should be incentivized; for example, by offering free service fares (Bamberg, Citation2006; Beirão & Cabral, Citation2007; Cats et al., Citation2017; Heath & Gifford, Citation2002; Kormos et al., Citation2015) or social studies tours as part of transportation education (Ito & Kawazoe, forthcoming).

Considering the significance of these factors, one possible and transferable conclusion is that, in order to explain and promote public transportation usage intention in a compact city environment, it may be appropriate to develop policy interventions drawn from the extended TPB model. For example, with personal or behavioural norm factors, rather than NAT. By seeing significant others using public transportation modes, the behavioural control will be perceived. In addition, behavioural norms and perceived behavioural control enable citizens to have positive attitudes toward public transportation use. Furthermore, given that TPB constructs tend to be significant in influencing the intention to use LRT, it may be effective to focus on self-interested rather than pro-social motivations in a compact city context.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This case study examined psychological and sociodemographic factors affecting LRT use in Toyama City as a compact city and found that attitudes, behavioural norms, and perceived behavioural control were significant factors predicting intention to use the LRT, which is, along with age, associated with its actual use. Drawing from these findings and relevant literature, we explored possible reasons why these variables were significantly associated with LRT use and propose several measures to promote LRT use and discourage car use, mainly constituting soft policy measures. This is largely because Toyama already has advanced hard measures through the establishment of a compact city rooted in a well-integrated public transportation system, as recognized by the Japanese government and international organizations. The city should possibly shift its focus on soft policy measures. This study has several limitations. First, because it relied on a research agency’s respondents for data collection, results may be affected by non-response bias (Mouratidis, Citation2018). We tried minimizing this by randomly sampling within the collected samples and adjusting sample populations to represent geographical and demographic characteristics in the city centre of Toyama. In addition, given that the current research is quantitative, future research should employ qualitative studies for triangulation, for example, by interviewing respondents to their preference for using (or not using) the LRT over other alternatives. Such future studies will reinforce the findings of the current study and allow for the development of more robust policy interventions that further promote LRT use.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.6 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Ababio-Donkor, A., Saleh, W., & Fonzone, A. (2020). The role of personal norms in the choice of mode for commuting. Research in Transportation Economics, 83, 100966.

- Addie, J.-P. D., Glass, M. R., & Nelles, J. (2020). Regionalizing the infrastructure turn: A research agenda. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7(1), 10–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2019.1701543

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (2005). The influence of attitudes on behavior. In D. Albarracín, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The handbook of attitude (pp. 173–221). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Anable, J. (2005). ‘Complacent car addicts’ or ‘aspiring environmentalists’? identifying travel behavior segments using attitude theory. Transport Policy, 12(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2004.11.004

- Arai, Y., Levine, D., Mikimoto, H., & Yamazaki, M. (2020). The development story of Toyama: Reshaping compact and livable cities. World Bank.

- Arroyo, R., Ruiz, T., Mars, L., Rasouli, S., & Timmermans, H. (2020). Influence of values, attitudes towards transport modes and companions on travel behavior. Transportation Research Part F, 71, 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2020.04.002

- Bamberg, S. (2006). Is a residential relocation a good opportunity to change people’s travel behavior? Results from a theory-driven intervention study. Environment and Behavior, 38(6), 820–840. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916505285091

- Bamberg, S., Ajzen, I., & Schmidt, P. (2003). Choice of travel mode in the theory of planned behavior: The role of past behavior, habit, and reasoned action. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 25(3), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2503_01

- Bamberg, S., Fujii, S., Friman, M., & Gärling, T. (2011). Behavior theory and soft transport policy measures. Transport Policy, 18(1), 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.08.006

- Bamberg, S., Hunecke, M., & Blöbaum, A. (2007). Social context, personal norm and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(3), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.04.001

- Basu, R., & Ferreira, J. (2021). Sustainable mobility in auto-dominated metro Boston: Challenges and opportunities post-COVID-19. Transport Policy, 103, 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.01.006

- Beck, M. J., & Rose, J. M. (2016). The best of times and the worst of times: A new best-worst measure of attitudes toward public transport experiences. Transportation Research Part A, 86, 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.02.002

- Beirão, G., & Cabral, J. A. S. (2007). Understanding attitudes towards public transport and private car: A qualitative study. Transport Policy, 14(6), 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2007.04.009

- Bhattacharjee, S., & Goetz, A. R. (2012). Impact of light rail on traffic congestion in Denver. Journal of Transport Geography, 22, 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.01.008

- Bickerstaff, K., & Walker, G. (2002). Risk, responsibility, and blame: An analysis of vocabularies of motive in air-pollution(ing) discourses. Environment and Planning A, 34(12), 2175–2192. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3521

- Byrne, B. (2011). Structural equation modelling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

- Carpintero, S., & Siemiatycki, M. 2016 The politics of delivering light rail transit projects through public–private partnerships in Spain: A case study approach. Transport Policy, 49, 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.05.001

- Cats, O., Susilo, Y. O., & Reimal, T. (2017). The prospects of fare-free public transport: Evidence from Tallinn. Transportation, 44(5), 1083–1104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-016-9695-5

- Cervero, R., & Sullian, C. (2011). Green TODs: Marrying transit-oriented development and green urbanism. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 18(3), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2011.570801

- Chowdhury, S., & Ceder, A. (2016). Users’ willingness to ride an integrated public-transport choice. Transport Policy, 48, 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.03.007

- Clark, B., Chatterjee, K., & Melia, S. (2016). Changes to commute mode: The role of life events, spatial context and environmental attitude. Transportation Research A, 89, 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2016.05.005

- Cohen, L., Manion, L, & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th Ed). London and New York: Routledge.

- de Oña, J., Estévez, E., & de Oña, R. (2021). Public transport users versus private vehicle users: Differences about quality of service, satisfaction and attitudes toward public transport in Madrid (Spain). Travel Behaviour and Society, 23, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2020.11.003

- Demarque, C., Charalambides, L., Hilton, D. J., & Waroquier, L. (2015). Nudging sustainable consumption: The use of descriptive norms to promote a minority behavior in a realistic online shopping environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.06.008

- Denant-Boèmont, L., & Mills, G. (1999). Urban light rail: Intermodal competition or coordination? Transport Reviews, 19(3), 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/014416499295510

- Dieleman, F., & Wegener, M. (2004). Compact city and urban sprawl. Built Environment, 30(4), 308–323.

- Dijkstra, J. K., Lindenberg, S., & Veenstra, R. (2008). Beyond the class norm: Bullying behavior of popular adolescents and its relation to peer acceptance. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(8), 1289–1299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9251-7

- Donald, I., & Cooper, S. R. (2001). A facet approach to extending the normative component of the theory of reasoned action. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 599–621. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466601165000

- Donald, I., Cooper, S. R., & Conchie, S. M. (2014). An extended theory of planned behaviour model of the psychological factors affecting commuters’ transport mode use. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.03.003

- Dueker, K., & Bianco, M. (1999). Light-rail-transit impacts in Portland: The first ten years. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1685, 171–180.

- Egset, K. S., & Nordfjærn, T. (2019). The role of transport priorities, transport attitudes and situational factors for sustainable transport mode use in wintertime. Transportation Research F, 62, 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2019.02.003

- Eriksson, L., & Forward, S. E. (2011). Is the intention to travel in a pro-environmental manner and the intention to use the car determined by different factors? Transportation Research Part D, 16(5), 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2011.02.003

- Forward, S. E. (2009). The theory of planned behavior: The role of descriptive norms and past behavior in the prediction of drivers’ intentions to violate. Transportation Research Part F, 12, 198–207

- Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., & Griskevicius, V. (2008). A room with a view point: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 472–482. https://doi.org/10.1086/586910

- Graham-Rowe, E., Skippon, S., Gardner, B., & Abraham, C. (2011). Can we reduce car use and, if so, how? A review of available evidence. Transportation Research A, 45(5), 401–418.

- Haustein, S. (2012). Mobility behavior of the elderly: An attitude-based segmentation approach for a heterogeneous target group. Transportation, 39(6), 1079–1103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-011-9380-7

- Heath, Y., & Gifford, R. (2002). Extending the theory of planned behavior: Predicting the use of public transportation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(10), 2154–2189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb02068.x

- Hurst, N. B., & West, S. E. (2014). Public transit and urban redevelopment: The effect of light rail transit on land use in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 46, 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2014.02.002

- Ibraeva, A., & de Sousa, J. F. (2014). Marketing of public transport and public transport information provision. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 162, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.192

- Ito, H., & Kawazoe, N. (2022). Promoting transportation policies in the context of compact city strategies: The case of Toyama City, Japan. Annals of Regional Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-022-01185-z

- Jaroszynski, M. A., & Brown, J. R. (2014). Do light rail transit planning decisions affect metropolitan transit performance? Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2419(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.3141/2419-06

- Kormos, C., Gifford, R., & Brown, E. (2015). The influence of descriptive social norm information on sustainable transportation behavior: A field experiment. Environment and Behavior, 47(5), 479–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916513520416

- le Clercq, F., & de Vries, J. S. (2000). Public transport and the compact city. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1735(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.3141/1735-01

- Levinson, H. S., Allen, J. G., & Hoey, W. F. (2012). Light rail since world War II: Abandonments, survival, and revivals. Journal of Urban Technology, 19(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2011.649911

- Lewis, P. G. (2014). Moral institutions and smart growth: Why do liberals and conservatives view compact development so differently? Journal of Urban Affairs, 37(2), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12172

- Lin, T., Wang, D., & Guan, X. (2017). The built environment, travel attitude, and travel behavior: Residential self-selection or residential determination? Journal of Transportation Geography, 65, 111–122.

- Long, B., Choocharukul, K., & Nakatsuji, T. (2011). Psychological factors influencing behavioral intention toward future sky train usage in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2217(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.3141/2217-08

- Mahieux, A., & Mejia-Dorantes, L. (2017). Regeneration strategies and transport improvement in a deprived area: What can be learned from northern France? Regional Studies, 51(5), 800–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1177174

- Manstead, A. S. R. (2011). The benefits of a critical stance: A reflection on past papers on the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50(3), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02043.x

- Mouratidis, K. (2018). Is compact city livable? The impact of compact versus sprawled neighbourhoods on neighbourhood satisfaction. Urban Studies, 55(11), 2408–2430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017729109

- Muro, T. (2009). Compact city development using public transport. Japan Railway & Transport Review, 52, 24–31.

- Novales, M., & Conles, E. (2012). Turf track for light rail systems. Transportation Research Record: Journal of Transportation Research Board, 2275(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3141/2275-01

- O’Sullivan, S., & Morrall, J. (1996). Walking distances to and from light-rail transit stations. Transportation Research Record, 1538(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198196153800103

- Priemus, H., & Konings, R. (2001). Light rail in urban regions: What Dutch policy makers could learn from experience in France, Germany and Japan. Journal of Transport Geography, 9(3), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0966-6923(01)00008-4

- Rex, J., Lobo, A., & Leckie, C. (2015). Evaluating the drivers of sustainable behavior intentions: An application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 27(3), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2015.1053342

- Rivis, A., & Sheeran, P. (2003). Descriptive norms as an additional predictor in the theory of planned behavior: A meta-analysis. Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, Social Psychology, 22(3), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-003-1018-2

- Sakamoto, K., Iida, A., & Yokohari, M. (2018). Spatial patterns of population turnover in a Japanese regional city for urban regeneration against population decline: Is compact city policy effective. City, 81, 230–241. https://doi.org/10.14398/urpr.4.111

- Scherer, M. (2010). Is light rail more attractive to users than bus transit: Arguments based on cognition and rational choice. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2144(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.3141/2144-02

- Shi, H., Fan, J., & Zhao, D. (2017). Predicting household PM2.5-reduction behavior in Chinese urban areas: An integrative model of theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory. Journal of Cleaner Production, 145, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.169

- Shigetou, S. (2020). Konpakuto na machidukuri to ekosisutemu no kouchiku [Compact city development and ecosystem construction]. In The Graduate School of Project Design Publishing (Ed.), Toyamashi jigyoukousou kenkyuukai: toyama-gata konpakuto shiti no kousouto jissen [Toyama City project operation study group: The concept and practice of Toyama-style compact city) (pp. 18–29). Sentan Kyouiku Syuppan.

- Smith, J. R., Louis, W. R., Terry, D. J., Greenaway, K. H., Clarke, M. R., & Cheng, X. (2012). Congruent or conflicted? The impact of injunctive and descriptive norms on environmental intentions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(4), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.06.001

- Steg, L. (2003). Can public transport compete with the private car? IATSS Research, 27(2), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0386-1112(14)60141-2

- Steg, L., Geurs, K., & Ras, M. (2001). The effects of motivational factors on car use: A multidisciplinary modelling approach. Transportation Research Part A Policy and Practice, 35(9), 789–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0965-8564(00)00017-3

- Steg, L., & Vlek, C. (1997). The role of problem awareness in willingness-to-change car use and in evaluating relevant policy measures. In J. A. Rothengatter, & V. E. Carbonell (Eds.), Traffic and transport psychology (pp. 465–475). Pergamon.

- Taube, O., Kibbe, A., Adler, M., & Kaiser, F. G. (2018). Applying the Campbell Paradigm to sustainable travel behavior: Compensatory effects of environmental attitude and the transportation environment. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 56, 392–407.

- Thompson, G. L. (2007). Taming the neighborhood revolution: Planners, power brokers, and the birth of neotraditionalism in Portland, Oregon. Journal of Planning History, 6(3), 214–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513206297457

- Thøgersen, J. (2009). Promoting public transport as a subscription service: Effects of a free month travel card. Transport Policy, 16(6), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2009.10.008

- Thøgersen, J. (2014). Social marketing in travel demand management. In T. Gärling (Ed.), Handbook of sustainable (pp. 113–129). Springer.

- Topalovic, P., Carter, J., Topalovic, M., & Krantzberg, G. (2012). Light rail transit in Hamilton: Health, environmental and economic impact analysis. Social Indicators Research, 108(2), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0069-x

- Toyama City. (2009). Konpakuto shithi senryaku niyoru Co2 sakugen keikaku (The CO2 reduction plan by the Toyama Compact City Strategy). <http://www.tkz.or.jp/econowa/detail.php?id=100025#./_upload/100025/kankyou_pic1.jpg.

- Toyama City. (2017). Dainiji Toyama-shi kankyoumiraitoshi keikaku (The second Toyama City’s action plans toward a future model city). http://www.city.toyama.toyama.jp/data/open/cnt/3/9930/1/dai2ji_kankyoumiraitoshikeikaku_honntai.pdf.

- Toyama City. (2021). Toyama-shi no jinkou (Toyama City’s population). https://www.city.toyama.toyama.jp/kikakukanribu/johotokeika/tokei/jinkosetai/R2/shinojinko2001.html.

- Urbanek, A. (2021). Fare-free public transport versus private cars: Zero fares as an instrument of impact on public transport mode share? Springer proceedings in business and economics. In M. Suchanek (Ed.), Transport development challenges in the 21st century (pp. 215–225). Germany.

- Vigrass, J. W., & Smith, A. K. (2005). Light rail in Britain and France: Study in contrasts, with some similarities. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Record, 1930(1), 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361198105193000110

- Waddell, L. P., & Wiener, K. K. K. (2014). What’s driving illegal mobile phone use? Psychosocial influences on drivers’ intentions to use hand-held mobile phones. Transport Research Part F, 22, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2013.10.008

- Wall, R., Devine-Wright, P., & Mill, G. A. (2007). Comparing and combining theories to explain proenvironmental intentions: The case of commuting-mode choice. Environment and Behavior, 39(6), 731–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916506294594

- Wall, R., Devine-Wright, P., & Mill, G. A. (2008). Interactions between perceived behavioral control and personal-normative motives. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2(1), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689807309967

- Wright, C., & Egan, J. (2000). De-marketing the car. Transport Policy, 7(4), 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-070X(00)00029-9

- Zhang, D., Schmocker, J.-D., Fujii, S., & Yang, X. (2016). Social norms and public transport usage: Empirical study from Shanghai. Transportation, 43, 869–888.