ABSTRACT

Digital technologies are transforming almost every aspect of people’s lives, with COVID-19 accelerating this transition. For refugees, access and familiarity with these technologies is critical to wider aims of social integration. This article explores digital inclusion during the COVID-19 pandemic, using data from studies conducted in 2020 and 2021 with refugees recently resettled in Australia. Inclusion was mapped against three domains – access, affordability, and literacy – from the annual Australian Digital Inclusion Index. Our study found that many respondents reported comparatively high digital inclusion. However, certain characteristics, such as gender, age, presence of children and country of birth, correlated with lower levels of inclusion within some refugee sub-groups. Our research makes three contributions: it examines levels of digital inclusion among recently arrived refugees during COVID-19; it explores how these levels relate to social links and bonds; and it discusses sample differences according to gender, age, language group and type of digital inclusion.

Introduction

Globally, we are living through a continuing transition towards the ‘information age’, as digital communication technologies transform almost every aspect of people’s lives. The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated this transition. For refugees, as with other people, digital inclusion is arguably ‘a critical aspect of social inclusion’ (Alam & Imran, Citation2015, p. 2; see also Reid, Citation2021), encompassing the effective ability to use ‘online and mobile technologies to improve skills, enhance quality of life, educate, and promote wellbeing, [and] civic engagement […] across the whole of society’ (Thomas et al., Citation2020, p. 8). Australia is marked by generally high digital access, though as recent results from the Australian Digital Inclusion Index (ADII – an annual measure of digital inclusion that examines access, affordability, and digital ability) (Thomas et al., Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2021) indicate, the nation continues to exhibit a digital divide that largely follows the contours of intersectional barriers, especially those relating to income, employment, and education. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the relevance of this divide became more pressing. As many everyday activities that had been performed in-person – including working, learning, shopping, socialising, maintaining contact with family and friends (Settlement Council of Australia [SCoA], Citation2020) – now took place online, levels of digital inclusion became proxies for wider social inclusion. For recent arrivals in Australia, often already isolated from prior social networks due to relocation, the importance of digital inclusion became paramount.

Using data from two phases of research conducted in 2020 and 2021 with participants who had recently resettled in Australia, this article seeks to better understand the digital inclusion of refugees during the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, we expected that newly arrived refugees would be particularly vulnerable to digital exclusion, as they navigate everyday activities in a new context. While the results largely confirmed these expectations, they contained some surprises: overall, many respondents reported comparatively high levels of inclusion, while certain characteristics, such as gender, age, presence of children and country of birth, were found to correlate with experiences of digital exclusion within refugee sub-groups. These findings confirmed responses to an earlier pre-COVID phase of our research among newly arrived refugees (Culos et al., Citation2020), which found that women generally reported greater difficulties accessing essential services due to the combined barriers of limited English language proficiency and limited digital literacy.

To support resettled refugees with integration in Australia, the Australian Government funds specialist settlement programs, delivered primarily by non-government organisations, that operate alongside mainstream and universal services, On arrival, refugees access the Humanitarian Settlement Program (HSP), typically for the first 18 months (Department of Home Affairs, Citation2022). The HSP offers airport reception, access to short-term accommodation, referral to mainstream and universal support services, connections to local community groups and activities, assistance to find long-term accommodation, learn English, gain employment and access education and training, and finally, a general orientation to Australia, including its values and laws. When refugees exit the HSP they are eligible to access the Settlement Engagement and Transition Support program, a national settlement scheme delivered by more than 100 non-government organisations nationally, which provides support for refugees up to five years post-arrival (Department of Home Affairs, Citation2023a). Though gaps remain, over time digital inclusion has gained prominence in the delivery of settlement support. Consultations conducted by the peak body of settlement providers in 2020 found that one-third of settlement providers listed digital inclusion as a key priority, and when discussing all other integration priorities, the impacts of digital inclusion in achieving those priorities was a common theme (SCoA, Citation2020).

The data reported here was collected over two subsequent phases of research (Culos et al., Citation2021, Citation2022), where we explored newly arrived refugees’ sense of welcome and belonging in Australia through surveys, supplementary focus groups and interviews. The surveys were informed by an influential framework of integration originally developed by the UK Home Office in 2004 (Ager & Strang, Citation2008), and updated in 2019 (Ndofor-Tah et al., Citation2019) to include a new domain – digital skills – in recognition of digital technology’s increased importance in refugee integration. The main domains or areas of integration considered under this framework are social connections – further distinguished into bonds, bridges and links – and rights and responsibilities. We extended this framework with an expanded treatment of digital inclusion based on measures of access, affordability and literacy used in the annual ADII (Thomas et al., Citation2020). Bringing together these conceptual frames of social integration and digital conclusion, the first survey was administered in late 2020 (Culos et al., Citation2021), at a time when the effects of COVID-19 on the lives of both refugees in Australia and members of their families in countries of origin/diaspora meant an even greater reliance on digital technologies. We complemented this data collection in the first phase with focus groups with refugee women. The follow-up survey, conducted in late 2021, occurred at a time when some public health restrictions were still in place, and this survey was complemented by family interviews, designed to further explore issues of extended family separation occasioned by border closures and international travel restrictions.

Studying this intersection between social integration and digital inclusion is significant due to the ways digital technologies can enhance integration: developing and maintaining social bonds in the country of resettlement, and allowing refugees to maintain contact with friends and family in their homeland and around the world (Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016). Technology facilitates social bonds and bridges within cultural, ethnic, and religious communities in the receiving country, reducing isolation and connecting newly-arrived refugees to both existing networks of family and friends and receiving country communities (AbuJarour, Krasnova, & Hoffmeier, Citation2018). Refugees also use technologies to establish and reinforce social links to essential services, contributing to independence and trust in social institutions (Almohamed, Vyas, & Zhang, Citation2017). Like others, refugees are reliant on digital technologies and skills to engage with these institutions for finding work and housing, education, and access to government services (Merisalo & Jauhiainen, Citation2020). In an increasingly digital world, and particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, access and affordability of digital technologies is integral to being able to fulfil rights and responsibilities in the receiving country.

Our research makes three contributions: (1) it examines levels of digital inclusion among recently arrived refugees during the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) it explores the relation of these levels to social bonds; and (3) discusses differences within the sample according to gender, age, language group and type of digital inclusion. Digital inclusion was mapped against three domains – access, affordability and literacy – used in the annual ADII discussed above (Thomas et al., Citation2020), and the findings here are presented under those headings, alongside related findings on social bonds. Our research finds overall that refugees in our samples generally scored well on our digital inclusion measures. Most were able to maintain family and social ties through regular contact using various digital platforms. Almost all refugees reported having access to the internet at home and a sufficient data allowance and, as another measure of digital access, refugee households report having multiple ICT devices. Yet while refugee women and men are equally adept at connecting digitally with family and friends, there were important differences in terms of engaging with commercial and government services online, revealing a gap in digital skills, particularly for women and older age cohorts. Younger refugees generally fare better across all measures of digital skills, with older age associated with poorer digital skills. These findings suggest that, as with the overall population, nuance needs to be brought to an understanding of digital inclusion among refugees in Australia; aggregated responses to measures, while indicative, can also disguise specific barriers with respect to, for example, gender and age.

Literature review

Information and communication technology (ICT) has transformed almost every aspect of people’s lives, as it allows them to access, adapt, create, distribute, and share information and enables communication and group interaction that transcends geographical and temporal barriers. Research with samples of the Australian population suggests a continued if gradually closing digital divide that is sustained along intersectional lines, especially across markers of income, employment and education (Thomas et al., Citation2020). This means, as Felton (Citation2012, p. 5) argues, that ‘students, younger people, employed, higher-educated, and higher-income individuals are more likely to use the internet than lower-educated and lower-income individuals’. Consequently, social inclusion and exclusion have typically – and perhaps exaggeratedly – been characterised as an ‘information’ problem (Alam & Imran, Citation2015; Caidi & Allard, Citation2005; Lloyd, Citation2016). As other scholars have suggested, bridging the digital divide involves not only technological provision – access to and use of devices and connectivity – but also an increasing of the human capital that enables people to reap social and economic benefits (Alam & Imran, Citation2015; Deursen & van Dijk, Citation2015; Reid, Citation2021; Thomas et al., Citation2020).

Such arguments apply no less to refugee populations, as a growing body of literature attests. While digital inclusion of refugees and migrants has been claimed to be an under-researched area in the past (Borkert, Cingolani, & Premazzi, Citation2009; Goodall, Ward, & Newman, Citation2010; Kenny, Citation2017; Leung, Citation2010), it has since received greater academic and political attention, most notably in Europe (Abujarour Citation2018; AbuJarour & Krasnova, Citation2017, Citation2018; AbuJarour, Krasnova, & Hoffmeier, Citation2018; AbuJarour et al., Citation2019; Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016; Beretta, Abdi, & Bruce, Citation2018; Colucci et al., Citation2017; Leurs, Citation2016; Martzoukou & Burnett, Citation2018; Merisalo & Jauhiainen, Citation2020; Stiller & Trkulja, Citation2018) but also in Australia (Alam & Imran, Citation2015; Almohamed & Vyas, Citation2019, Leung, Citation2018; Almohamed et al., Citation2017; Khoir, Du, & Koronios, Citation2014; Lloyd, Citation2016; Lloyd, Kennan, Thompson, & Qayyum, Citation2013; Lloyd, Lipu, & Kennan, Citation2016; Richards, Citation2015; Shariati, Citation2019), New Zealand (Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016) and the United States (Bletscher, Citation2020). This increased focus responds in part to what Schultz et al. have termed a ‘global humanitarian crisis’ (Shultz et al., Citation2020), produced by ‘violence, conflict/war, persecution, or human rights violations’ and ‘climate change’, which has led to, and continues to generate today, an unprecedented number of displaced people undertaking perilous journeys to seek protection. Digital technologies are integral to all phases of these journeys – before, during and after resettlement (Gapsiso & Jibrin, Citation2019; Reid, Citation2021) – and as Shultz et al. (Citation2020) also note, are often key to finding safe passage after a disaster and locating other displaced family members.

This welcome academic attention on forced migration and ICT over the past decade has resulted in the emergence of a new research field, Digital Migration Studies (Alencar, Citation2020; Mancini, Imperato, Vesco, & Rossi, Citation2022, and in the remainder of the review, we describe several dimensions of this literature in relation to digital inclusion and refugees. While we focus on studies conducted in Australia, recent research from other Western countries with refugee resettlement programs are also included, and we note that these contexts differ widely in conditions of resettlement. In our study for example, participants were holders of a permanent protection visa and had secure residency in Australia. For other groups in Australia, and others internationally, these conditions may be very different in terms of experiences and preferences, with flow-on effects into technology use and barriers.

In examining how technologies are used to navigate settlement by both refugees and receiving country settlement organisations, research has emphasised the diversity of digital literacy capacities, and the importance of understanding and assessing different needs, in order to tailor programs and services around specific requirements (Emmer, Kunst, & Richter, Citation2020; Lloyd et al., Citation2016; Reid, Citation2021; SCoA, Citation2020). Differences between the level of digital literacy among refugees can be stark – some have very advanced skills when they arrive in their receiving country, whereas others might have very limited prior experience and knowledge (Shariati, Citation2019). Nevertheless, all newly arrived refugees face a complex infrastructural landscape that differs from their previous experiences of digital technologies (Kennan, Lloyd, Qayyum, & Thompson, Citation2011). Examining how refugees in Australia engage with this unfamiliar setting, Lloyd et al. (Citation2013) found that refugees require assistance in effectively understanding and navigating digital modes of service delivery and information, which is often provided by mediators such as caseworkers, volunteers in settlement services or other community members. Digital modes of service delivery can also support settlement programs during, for instance, periods of transition, settling-in and being-settled (Almohamed et al. Citation2017; Kennan et al. Citation2011).

In studies of refugee technology use, two common themes can be identified in relation to purpose: (1) the facilitation of community bridges and organisational links in the receiving country; and (2) maintenance of existing social bonds. In relation to the first of these, refugees use technology to adjust to a new living environment, and to solve everyday problems related, for instance, to shopping (Shariati, Citation2019), transport (Massmann, Citation2018), health check-ups, online banking and job search (Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016). Technologies have been used to learn the local language (Massmann, Citation2018) as well as to acquire knowledge about the receiving society and comply with laws and regulations (Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016; Lloyd et al., Citation2013). As examples of social bonds, technology also allows refugees is to maintain contact with friends and family in their homeland and around the world (Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016; Shariati, Citation2019), with resulting positive impacts on well-being and reduced feelings of family separation (Shariati, Citation2019). In addition, access to the internet allows refugees to monitor events in their home country and to stay politically involved (Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016). This access also facilitates communication within refugees’ ethnic communities, often geographically dispersed in the receiving country, allowing them to share settlement experiences and advice with more experienced refugees, which in turn can ‘assist refugees to become less isolated, less marginalised and more a part of mainstream society’ (Shariati, Citation2019, p. iv). While smartphones are the main device which refugees use during displacement and early resettlement (Abujarour, Citation2018; Bacishoga, Hooper, & Johnston, Citation2016; Emmer et al., Citation2020; Massmann, Citation2018; Shariati, Citation2019), once they become more settled, they may use a broader range of devices, as Massmann (Citation2018) has argued in a study on refugees’ ICT use in the Netherlands.

Research has indicated that these affordances vary within refugee populations, with differences in inclusion occurring on the basis of gender, age and education (O’Mara, Hurriyet, & Borland, Citation2010). A study of Iranian refugees in Australia (Shariati, Citation2019) has shown that women demonstrated lower digital skills and interacted less with Australian government departments than men, despite similar rates of tertiary education, reflecting a more general relationship between tertiary education and digital inclusion within the wider Australian community (Thomas et al., Citation2019). Shariati attributes this gender divide to traditional cultural gender roles that see women’s primary responsibility in looking after the house and the family – though as our results show, the tendency of women with children to report higher levels of digital inclusion suggests other factors may also be involved.

With regards to age, Alam and Imran (Citation2015) found that older refugees in regional Australia were more reluctant to use the internet, while younger refugees attributed high value to the availability of internet access. Examining younger newly arrived refugees in Australia, Kenny (Citation2017, p. 8) found that digital technologies were integral to multiple aspects of settlement: ‘maintaining important connections to family and friends overseas, connecting to local opportunities and resources, developing broader social networks and skills, and accessing information and tools to support their language acquisition and general knowledge about Australian culture and society’. Alongside a general affinity for technology, younger resettled refugees are more likely to need to build new bridges and links, while also sustaining existing bonds, across a range of communication functions and platforms.

Studies among the broader Australian community have shown that those with higher education are most likely to be digitally included and thus receive more benefits from ICT-based services (Thomas et al., Citation2019); refugees are often educationally disadvantaged because of their displacement, and consequently may show low levels of digital inclusion (Leung, Citation2020). In addition, many refugees face language and literacy barriers – both often related to the level of education – when resettling in a new country, which adds further challenges to their digital inclusion. Some differences with regards to digital inclusion have also been linked to cultural backgrounds, with Emmer et al. (Citation2020) finding that participants from Syria and Iraq in their study were more likely to use technologies throughout their settlement journey than refugees from central Asia. Such findings suggest conditions of technology access and use in countries of origin are likely a helpful predictor for levels of post-settlement digital inclusion.

Measures of Australian migrant, and specifically of refugee, digital inclusion have gradually been refined, alongside the emergence of dedicated annual population surveys. Where the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Citation2018) had gathered information on digital inclusion each year from 1996 through to 2017 through the Household Use of Information Technology (HUIT) survey, since 2015 digital inclusion has been measured by a separate Australian Digital Inclusion Index (ADII) survey (see Thomas et al., Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2021). Developed by RMIT University, Swinburne University of Technology and a major Australian telecommunications company, and administered across measures of access, affordability, and digital ability, the ADII has increasingly sought to examine specific barriers to inclusion across specific population groups. The 2020 ADII found that migrants – people who were born in non-main English-speaking countries and spoke a language other than English at home – demonstrated a high level of digital inclusion that was above the Australian average. However, due to the diversity of this group, internal differences were not captured by the Index. An associated ADII case study of 164 migrants who arrived in Australia after 2005 and were settled in a regional city revealed that newly arrived migrants experience higher rates of digital exclusion, mainly related to affordability (Thomas et al., Citation2019). Conversely, study participants demonstrated a high level of digital ability and 87% (cf. 48% national average (NA)) felt that ‘computers and technology gave them more control over their lives and a similar proportion (86%, cf. 35% NA) are committed to learning about new technologies’ (Thomas et al., Citation2019, p. 21). As Thomas et al. (Citation2019, p. 22) further note, activities among migrants differed in important ways from Australia’s general population: ‘the level of engagement in some functional activities, such as email, internet banking and online commerce and transactions was substantially below the national average. However, the use of the internet for searching for information related to education, employment, health and other essential government and technical services and activities was above the national average’.

Our own results largely echo these findings, with the exception of affordability – though participants did discuss the high cost of devices, and costs of connectivity were not reported as major difficulties. This may relate to the average length of stay, costs of access in countries of origin, or other cohort-specific characteristics, and in any case underscore the complexity of refugee experience in relation to different facets of inclusion. Our research also explores in greater detail than how ABS or ADII measures the relationship between digital inclusion and the maintenance of social bonds, and how this relation may also differ across gender, age and language groups. In examining the influence of these factors, it addresses a degree of homogenisation that exists in national studies towards refugees, illustrating the great internal diversity of this population and contributing to a more calibrated understanding of what digital inclusion barriers might exist for certain refugee groups, and what strategies may be effective in overcoming them.

Methods

This article reports on data collected over two phases of a study conducted by, in partnership with, a non-government organisation providing on-arrival services to refugees via the Humanitarian Settlement Program, funded by the Australian Government. As discussed in the Introduction, the first phase of the research focussed on general measures of bonds, bridges and links, while the second phase examined additional measures of digital inclusion. This focus was motivated by the fact that the daily life of people in Australia was impacted by COVID-19 related restrictions and lockdowns which amplified the role digital technologies played in managing everyday tasks such as working, learning, socialising, and accessing services. Our research includes quantitative and qualitative data: two telephone surveys (conducted in late 2020 and late 2021) with former clients of, and four follow-up in-person focus groups with refugee women (conducted in early 2021).

For the telephone surveys, a sample was generated from records of former participants of delivery of the Humanitarian Settlement Program. Criteria for participation included that participants were no longer being supported by and were over 18 years of age. We also excluded any participants who had been referred back for complex case support. For each survey a stratified sample was selected by place of residence (regional/metropolitan), gender, visa type and language spoken at home, and within each of the groups, random participants were selected to reach strata targets. In each survey, we matched the average residency of our sample with waves of the Building a New Life in Australia – a longitudinal study of refugees conducted by the Department of Social Services (Citation2023) – which was the source of many measures in our survey instrument and allowed for comparisons of our surveys with a contemporary refugee dataset. The research received ethics approval from and prior to the research being conducted, all participants received Participant Information Sheets and consented to collection of their data for the purposes of research.

The two surveys included questions on digital access (internet connection, number and type of ICT devices), digital affordability (data allowance) and digital ability (use of ICT), drawn from the now- discontinued Australian Bureau of Statistics Household Use of Information Technology (HUIT) survey. Questions from the more recent annual ADII were not publicly available at the time of the study, so direct comparisons with a more contemporary dataset of the Australian population were not possible. Where relevant, we compared findings with the last HUIT, conducted in 2017.

Both surveys also included questions examining the relationship of technologies to social bonds (maintaining contact with friends and family) and social links (digital interactions with services and other institutions in Australia). In the 2021 survey, we added new questions around capability of using the internet, taken from the Building a New Life in Australia study (Department of Social Services, Citation2023). In this second phase, we also conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with seven refugee families who arrived in Australia to explore aspects of digital inclusion among other aspects of their post-arrival and COVID-19 experience. Interview participants were mainly from Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan, and had diverse language backgrounds, including Arabic, Assyrian, Dari, Hazaragi and Kurdish/Kurmanji. Interviews with at least two family members were conducted online in-language by bilingual research assistants.

A breakdown of the key demographics of the respondents for both telephone surveys can be found in . All respondents were holders of an Australian permanent resident visa. The average length of residency in Australia of refugee respondents in the two surveys differed, with 2021 respondents resident for up to four years, compared to two years for 2020 respondents. This difference in average residency in Australia is considered when interpretating our findings below.

Table 1. Survey demographics.

As part of the first phase of the research, qualitative data was also collected through four focus groups with refugee women in February 2021, to better understand the technology needs and challenges of refugees in Australia. Female participants were recruited among the 2020 survey respondents on a voluntary basis, and the focus groups were conducted in four different languages: Kurdish/Kurmanji, Tibetan, Arabic, and Assyrian and included 21 participants. In the subsequent research phase, we conducted seven family interviews drawn from our 2021 survey respondents, and while the focus was not directly on digital inclusion, these also provided insights on technology use during the pandemic.

Findings

Survey results are presented here under three headings: (1) Digital Access and Affordability, (2) Digital Use and Abilities, and (3) Digitally-Mediated Social Bonds. The first two sections broadly align with ADII categories of access, affordability and ability; as we ask relatively few questions about affordability, those results are included with access. Overall respondents reported high levels of access, and neither survey nor interview responses suggested this access was unaffordable. In relation to uses and abilities, responses varied more widely, and we discuss these alongside differences due to gender, age, presence of children, and country of origin. Digital use in some cases also indicates the degree to which social links – to government and other institutional services – are facilitated by technology. In the third section, we discuss how digital inclusion relates to social bonds, and in particular maintenance of ties to friends and family, where again we note gendered differences.

Digital access and affordability

The survey results showed that 95% of the respondents in 2020 and 98% in 2021 had access to the internet on the household level (). This rate is higher than that found in the HUIT in 2016/17 (86%) and higher compared to other Australian households as measured in the ADII 2020 (88%), though slight differences in question wording may account for this increase. Household internet users ranged between one and nine, with an average of 3.9.

Table 2. Do you or any member of your household have access to the internet at home, whether through a computer, mobile phone or other device?

In the follow-up focus groups in the first phase of research, participants emphasised that internet services were much more accessible in Australia compared to their countries of origin. This assessment indicates that self-reported evaluations in relation to internet accessibility of newly arrived refugees may skew positively, because of their comparison to limited or no access in their homelands. Our survey did not show any significant differences in access due to gender, place of residence or language groups, though access did correlate with age – younger respondents reported higher rates of access to internet at home.

Respondents were also asked about the number and type of digital devices in their household, and reported that mobiles/smartphones were more common than desktop/laptops and tablets among respondents (). This confirms prior research identifying mobile phones as the most common devices among refugees (Abujarour, Citation2018; Bacishoga et al., Citation2016; Emmer et al., Citation2020; Massmann, Citation2018; Shariati, Citation2019). There were no differences in terms of gender but there was a difference in terms of household composition. Households with children under 18 had more tablets (average 0.9 with children under 18, compared to 0.4 without children under 18), though the number of desktop/laptop computers was very similar (average 1.4 with children under 18, compared to 1.3 without). The average number of mobiles/smartphones and desktop/laptops computers in the households of respondents were all higher in 2021, perhaps a reflection of longer residency in Australia among respondents.

Table 3. Average number of devices used by the household to access the internet, by type (* not asked in 2021 survey).

Tablets, desktops, and laptops are vital for remote schooling, that was in place due to COVID-19 public health restrictions for several months preceding the 2021 survey. Our findings in the previous 2020 survey indicated that families with school-aged children had fewer of these devices. Encouragingly, though also possibly an effect of the different cohort with a longer average residency, the 2021 survey shows a welcome increase overall compared to 2020, with households with school-aged children having slightly greater access to these devices.

The families we interviewed in late 2021 noted the importance of ICT during the pandemic, describing how digital platforms provided them with health and medical advice, and updates on restrictions and rules, vaccine availability, testing locations, contact tracing and other support services. Through technology, children had access to school and adults to vocational learning (e.g. TAFE) during lockdowns. Social media enabled one Afghan couple, for example, to keep updated on Australia’s policies and changes regarding visa applications before, during and after the evacuation of Kabul in August 2021. Email and other messaging platforms allowed them to follow up the family’s visa application for relatives with a lawyer.

Respondents who reported having household internet were asked if they had sufficient data allowance – a measure of affordability – and approximately nine out of ten respondents (88% in 2020 and 95% in 2021) responded affirmatively. Those who replied no gave reasons of high cost or poor reception. While the family interviews did not mention affordability, it may also be that the integral nature of ICT to family life meant costs of devices, connectivity, and app subscriptions were viewed as ‘proxy’ costs for other activities. During these interviews, participants referred often to digital communications and interactions via text and messaging, social media, apps and websites. Follow-up studies in the post-COVID context may show that competing expenditures and rising costs of digital connectivity, alongside other pressures such as increasing interest rates, mean affordability resurfaces as an issue.

Digital use and abilities

The main reason respondents accessed the internet in the 2020Footnote1 survey were for social media, entertainment, and banking () – findings similar to HUIT 2016/17, though significantly lower than the general population. The starkest difference could be found in purchasing goods and services, whereby only 34% of our survey respondents indicated that they used the internet for online shopping in the past three months, compared to 73% of HUIT respondents. There were no significant gender differences in reasons for using the internet, but women were less likely to nominate uses than men across every indicator. Across all types of internet use, respondents aged 25–34 reported the highest rates, underscoring generally higher levels of inclusion among younger groups.

Table 4. Reasons for accessing the internet in the past three months.

Given the different patterns of ICT use in the 2020 survey (), in the second phase we asked about self-reported digital skills, adapting a question used in Wave 5 of Building a New Life in Australia, a major longitudinal study of refugees carried by the Department of Social Services, to assess these skills.Footnote2

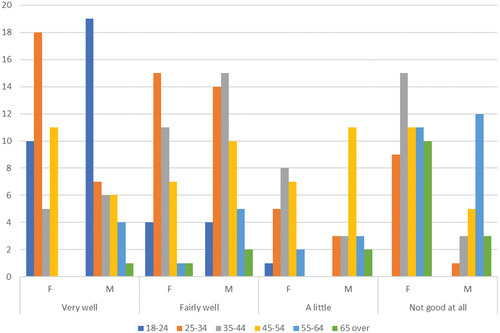

As shown in , respondents reported stronger digital skills in connecting with family and friends, getting news from home, and accessing entertainment. Meanwhile they reported weaker skills in online study, shopping and paying bills, and moderate skills in accessing health and welfare and social services.

Table 5. When you use the internet, how well are you able to … ?

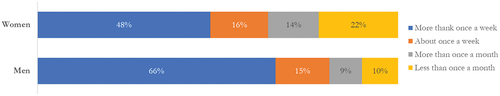

Gender and age played a significant role in knowing how to get access to essential welfare and social services. As shown in below, women tended to report lower levels of access compared to men. Considered across all ages, just over half (51.3%) of women reported being able to access welfare services fairly or very well, compared to two thirds of men (66.9%). These are strongly influenced by age – women and men in the youngest group (18–24) reported similarly high levels of access. With the second youngest group (25–34), gender differences already began to appear: 29.7% of women report having low levels (‘A little’, ‘Not good at all’) of access, compared to 16.0% of men in the same bracket. As we note below, women with children under the age of 18 reported consistently greater levels of access and skill for this as well as for other measures, compared to women without children – even in the same age brackets. This difference was not reported by male respondents, for whom having children under 18 made no difference to stated ability to access welfare. While it is possible cultural and gender factors may influence these results – with older men more likely to access services, and to report being able to do so – this analysis also highlights a specific deficit with respect to women without children that is only partly moderated by age. Women of all ages, in other words, without dependents were less likely to report high levels of access to welfare services than their peers, and this result was largely replicated across other digital skills (able to browse, pay bills, and so on).

Figure 1. When you use the internet, how well are you able to access welfare and social services … ? (number of respondents by gender and age bands).

Older age was also associated with poorer digital skills generally, with participants over 55 having more difficulties. Age had a strong influence on all digital skills measures and is statistically significant on all measures. The skills to learn and study English online declined among age groups over 35–44 years of age, as did the ability to access health services online.

Our research thus confirms findings from other studies that showed a higher rate of digital ability among male refugees (Merisalo & Jauhiainen, Citation2020; Shariati, Citation2019) after a settlement period of two to four years. This difference, though greater in magnitude, corresponds with that of the Australian population, with men reporting higher levels of digital ability than women (Thomas et al., Citation2021). Difficulties accessing government services online were most pronounced among women over 55; over 50% stated that they would not know how to find help online (see ). This highlights the need for older refugee women to receive training/support in navigating online government services, as they are otherwise reliant on private networks to facilitate this access, putting them in a vulnerable, dependent position. Women living with children under 18 reported far less online/internet difficulties compared to other women, indicating the critical role that refugee children hold in facilitating digital inclusion in their families.

Table 6. If you had to would you know how to find and get help through the internet or mobile apps for services you need (e.g. MyGov, TAFE, Medicare)? (by gender).

During focus groups, a number of women indicated the importance of internet connectivity. As one participant in the Assyrian focus group stated:

Life would have been harder, harder and more in chaos, if there wasn’t internet. We didn’t have that easy access to the internet back in Iraq. It’s easier to access the internet here […]. You feel happy in life with all this easy stuff through the internet.

In the Kurdish-Kurmanji focus group, women highlighted the importance of using the internet to ‘further’their skills and knowledge of the world:

So we use it for our study, basically, and also to know the news around the world. What is happening in this country and also other country around the world, just to know what is going on.

The same group of women underscored the importance of digital skills, with many reporting limited ability to navigate the online world. Those women relied on assistance from others, such as family and friends, for access to (i.e. borrowing a device) and use of (i.e. filling in online forms) the internet.

While some women depended on the assistance of others (most commonly their teenage children), others reported reciprocal relationships – receiving but also providing help with digital activities, for instance, to elderly parents. One respondent in the Assyrian group reported using the internet to translate for her mother when attending doctor’s appointments:

When I takes my mum to the doctor’s – for example, a doctor that I have to get the train to get to – I would use the Internet or the dictionary to put the sentences together in English to explain it to the doctor, to convey the message that she wants to in his language.

Such mutual support points to the role of social bonds in developing digital inclusion, though it also comes with risks. One participant in the Tibetan focus group for instance mentioned that she often helps other women in the community with online forms and accessing services but is sometimes concerned about the access to their private information and passwords. Despite strong gendered differences, during focus groups women also emphasised that they preferred accessing government services online rather than in person. Even if they required some help with online access, they found this preferable to having to attend in-person appointments or travel to an office. One of the women in the Assyrian focus group mentioned that having access to these services online had helped in the family’s settlement journey in Australia:

A lot of things have been very easy using the internet. Do the net banking, Medicare … if I need something, I would access those services on the internet. But mainly Centrelink services on the internet.

Digitally-mediated social bonds

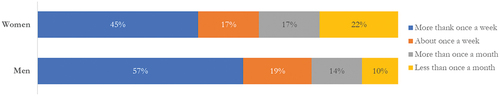

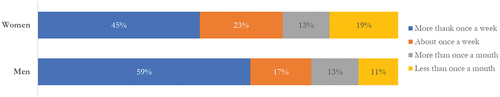

Smartphones, the most common devices used by refugees, are important facilitators of social bonds, as mobile-based services and applications allow for regular contact with friends and family members around the world (Andrade & Doolin, Citation2016; Shariati, Citation2019). Questions about modes and frequencies of contact with family and friends explored these connections in both surveys. Around nine out of ten respondents in the 2020 survey reported using audio/video calls (92%), social media (88%) or text messages (82%) on a daily or weekly basis to stay in touch with friends and family. In the 2021 survey, we separated out contact with family from contact with friends, to get more nuanced insights into the social bonds of refugees. More than four in five respondents in the 2021 survey spoke on the phone (89%), used social media (85%), and exchanged text messages (85%) to stay in touch with family at least weekly (). The frequency of reported contact with friends was lower than with family (72, 69, and 74%, respectively), but still included more than two-thirds of respondents. Refugees are likely to have family members in countries of origin, countries of displacement, other countries and other parts of Australia, and used all three communication methods frequently. We observed an increase in the use of these digital modes of communication from 2020 onwards, which might be related to a higher need for contact with family and friends due to COVID-19 and related restrictions on travel.

Table 7. Women’s online/internet difficulties accessing government services by age (2021 survey).

While no similar relationship was found between gender and maintaining contact with family, t-tests showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in maintaining contact with friends, with men more likely to communicate via all three forms – calls, social media, and text messages – than women (; ). ANOVA tests (p < 0.05) found statistically significant differences in language groups in terms of contact with both family and friends, with Dari/Farsi and Kurdish/Kurmanji language-speaking respondents having less frequent contact. For example, 84% of Arabic and 77% of Assyrian speakers reported texting family members more than once a week; these figures decline to 29 and 24%, respectively, for Dari/Farsi and Kurdish/Kurmanji speakers.

Figure 2. On average, how often do you speak on the phone or video with friends? (by gender, 2021 survey).

Figure 4. On average, how often do you exchange text messages or instant messages with friends? (by gender, 2021 Survey).

Table 8. On average, how often do you … with family members or friends? (2021 Survey).

Conclusion

Our ongoing research on the sense of welcome and belonging of newly arrived refugees in Australia measures their level of digital inclusion and both confirms findings from the existing digital migration studies literature and provides fresh insights into the relationship between refugee settlement and ICT. Our results show comparisons with the general Australian population while also indicating differences within refugee groups based on gender, age and other variables, and we also highlight the critical relationship between digital and social inclusion during COVID-19.

While refugees in our survey samples report high rates of internet access, we have found small but significant differences between refugees resettled in Australia and the rest of the population. For instance, more refugees use smartphones to access and use the internet rather than desktops/laptops/tablets, which has implications for their capacity to participate in education and employment – both of which, following COVID-19, have increasingly moved online. Like the general population, the main reason for accessing the internet were social media, entertainment, and banking; however these uses occurred at significantly lower levels. Refugee women nominated fewer reasons for accessing the internet than men, and reported less confidence in accessing government services online. As a result, they were often dependent on the support of others – most often their children – to navigate digital services. In addition, differences in digital abilities were found across different cohorts, i.e. age, language, and gender groups, highlighting the need for nuanced and tailored digital programs and policies rather than one-size-fits-all approaches. While building upon general population surveys like ADII, our results supply much-needed detail indicating specific areas of exclusion for future policy and service delivery in the Australian context.

Our findings also show how during the pandemic digital inclusion became virtually synonymous with, rather than a subset of, settlement and social integration for refugees. Comparatively, minor differences in the number, type, speed, and level of connectivity of household internet devices could facilitate or obstruct participation in education, employment and communication, and accordingly strengthen or attenuate social bonds, bridges, and links. What might otherwise appear an inconvenience – requiring a visit to a government office to complete health or migration forms – becomes instead an impossibility if households lack digital skills to navigate often opaque online bureaucratic systems. While pandemic lockdowns may be a receding memory, they highlight disparities and inequalities even when, as the ADII reports have shown across Australia’s overall population, digital inclusion is generally rising. Methodologically, the coincidence of digital inclusion and refugee integration suggest further tie-ins between measurement frameworks. Our efforts to integrate two distinct conceptualisations (digital inclusion as access/affordability/ability; and the domains of social bonds/bridges/links in integration) appear here as coincident, but perhaps suggest complementary axes against which an emerging socio-technical inclusion could be mapped. This possibility is reinforced by focus group and interview data, which suggest how, for example, social bonds (e.g. family members) facilitate the digital access and ability of refugees to, in turn, strengthen social links (e.g. access to government, financial, health, and education services).

The post-pandemic situation suggests these two areas of inclusion – social and digital – are now to a greater degree mutually constitutive. Our findings also strengthen the case for considering digital inclusion and the social domains of refugee integration as increasingly closely interconnected for refugees in countries where, like Australia, health, welfare, financial, education, and employment services are largely delivered online. In recognition of this, the Australian Department of Home Affairs (Citation2023b) recently included digital literacy in the framework used to monitor outcomes across major settlement programmes delivered to refugees. Pandemics add further uncertainty to the complexities of forced migration, and individual refugees can be isolated from families and other networks for extended periods. Comparatively, low population densities and large distances also mean settlement in Australia creates additional dependencies upon digital inclusion, compared with, for example, the European contexts. Further work is needed to unpack these complexities in post-pandemic settings, to strengthen support for all forms of inclusion for refugees.

Digital Inclusion _Addressing Reviewer Comments.docx

Download MS Word (23.6 KB)Disclosure statement

This research involved collaboration between a non-profit organisation and a university. As part of this collaboration, the university received funding from the non-profit organisation. This funding covered costs of employing one of the authors of this article. There are no other financial or non-financial interests to declare.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2024.2345000

Notes

1. This question was not included in the 2021 survey.

2. Our modifications to the original BNLA question were to change wording from ‘What do you use the internet for’ (dichotomous ‘Yes/No’ responses) to a scaled multiple choice variant to measure self-reported ability (‘Very Well’, ‘Fairly Well’, ‘A little’, ‘Not at all’). In addition we removed one item (‘Learn about Australian culture’), and added two others relating to access to health, and welfare and social services.

References

- Abujarour, S. (2018). Digital integration: The role of ICT in social inclusion of refugees in Germany. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329423548_Digital_Integration_The_Role_of_ICT_in_Social_Inclusion_of_Refugees_in_Germany/link/5c07cdf2a6fdcc494fda766b/download

- AbuJarour, S., & Krasnova, H. (2017). Understanding the role of ICTs in promoting social inclusion: The case of Syrian refugees in Germany. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Systems (pp. 1792–1806). Guimarães, Portugal: AIS Electronic Library.

- AbuJarour, S., & Krasnova, H. (2018, August). E-Learning as a means of social inclusion: The case of Syrian refugees in Germany. AMCIS 2018 Proceedings. Retrieved from https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2018/Education/Presentations/28

- AbuJarour, S., Krasnova, H., & Hoffmeier, F. (2018, November). ICT as an enabler: Understanding the role of online communication in the social inclusion of syrian refugees in Germany. Research Papers. Retrieved from https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2018_rp/27

- AbuJarour, S., Wiesche, M., Andrade, A., Fedorowicz, J., Krasnova, H., Olbrich, S., … Venkatesh, V. (2019). ICT-Enabled refugee integration: A research agenda. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 44(June), 874–890. doi:10.17705/1CAIS.04440

- Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(2), 166–191. doi:10.1093/jrs/fen016

- Alam, K., & Imran, S. (2015). The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants: A case in regional Australia. Information Technology & People, 28(2), 344–365. doi:10.1108/ITP-04-2014-0083

- Alencar, A. (2020). Mobile communication and refugees: An analytical review of academic literature. Sociology Compass, 14(8), e12802. m. doi:10.1111/soc4.12802

- Almohamed, A., & Vyas, D. (2019). Rebuilding social capital in refugees and asylum seekers. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 26(6), :41:1–:41:30. doi:10.1145/3364996

- Almohamed, A., Vyas, D., & Zhang, J. (2017). Rebuilding social capital: Engaging newly arrived refugees in participatory design. In Proceedings of the 29th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction, 59–67. OZCHI ’17. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Andrade, A. D., & Doolin, B. (2016). Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. MIS Quarterly, 40(2), 405–416. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.2.06

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Household use of information technology. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/technology-and-innovation/household-use-information-technology/latest-release

- Bacishoga, K. B., Hooper, V. A., & Johnston, K. A. (2016). The role of mobile phones in the development of social capital among refugees in South Africa. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 72(1), 1–21. doi:10.1002/j.1681-4835.2016.tb00519.x

- Beretta, P., Abdi, E., & Bruce, C. (2018). Immigrants’ information experiences: An informed social inclusion framework. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 67(4), 373–393. doi:10.1080/24750158.2018.1531677

- Bletscher, C. (2020). Communication technology and social integration: Access and use of communication technologies among floridian resettled refugees. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 21(2), 431–451. doi:10.1007/s12134-019-00661-4

- Borkert, M., Cingolani, P., & Premazzi, V. (2009). Study on ‘the state of the art of research in the EU on the uptake and use of ICT by immigrants and ethnic minorities (IEM)’, IMISCOE working paper No. 27, International and European Forum on Migration Research. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/library-document/study-state-art-research-eu-uptake-and-use-ict-immigrants-and-ethnic-minorities_en

- Caidi, N., & Allard, D. (2005). Social inclusion of newcomers to Canada: An information problem? Library & Information Sciences Research, 27(3), 302–324. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2005.04.003

- Colucci, E., Smidt, H., Devaux, A., Vrasidas, C., Safarjalani, M., & Castaño Muñoz, J., (2017). Free digital learning opportunities for migrants and refugees: An analysis of Current initiatives and recommendations for their further use ( EUR 28559 EN). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved from https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/684414.

- Culos, I., McMahon, T., Khorana, S., Robertson, S., Baganz, E., Magee, L., and Agha, Y. (2022). Foundations for belonging: Family separation and reunion during the pandemic. Sydney: Settlement Services International and Western Sydney University. https://www.ssi.org.au/images/FFB_Family_during_pandemic_final_screen.pdf

- Culos, I., McMahon, T., Robertson, S., Baganz, E., & Magee, L. (2021). Foundations for belonging: Women and digital inclusion. Sydney: Settlement Services International and Western Sydney University. https://apo.org.au/node/313991

- Culos, I., Rajwani, H., McMahon, T., & Robertson, S. (2020). Foundations for belonging: A snapshot of newly arrived refugees. Sydney: Settlement Services International and Western Sydney University. Retrieved from https://www.ssi.org.au/images/Signature_Foundations_Report_withlink.pdf

- Department of Home Affairs. (2022). Humanitarian settlement program. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of Home Affairs. (2023a). The refugee and humanitarian entrant settlement and integration outcomes framework. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023.

- Department of Home Affairs. (2023b). Settlement engagement and transition support. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of Social Services. (2023). Building a new life in Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Deursen, A., & van Dijk, J. (2015). Toward a multifaceted model of internet access for understanding digital divides: An empirical investigation. The Information Society, 31(5), 379–391. doi:10.1080/01972243.2015.1069770

- Emmer, M., Kunst, M., & Richter, C. (2020). Information seeking and communication during forced migration: An empirical analysis of refugees’ digital media use and its effects on their perceptions of Germany as their target country. Global Media and Communication, 16(2), 167–186. doi:10.1177/1742766520921905

- Felton, E. (2012). Migrants’ use of the Internet in Re-settlement ( Unpublished manuscript). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/216412/1/Migrants_use_of_the_Internet_v31.pdf

- Gapsiso, N., & Jibrin, R. (2019). Information and Communication Technology, migration and social inclusion. Journal of Resources & Economic Development, 2(3), 100–109.

- Goodall, K., Ward, P., & Newman, L. (2010). Use of information and communication technology to provide health information: What do older migrants know, and what do they need to know? Quality in Primary Care, 18(1), 27–32.

- Kennan, M. A., Lloyd, A., Qayyum, A., & Thompson, K. (2011). Settling in: The relationship between information and social inclusion. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 42(3), 191–210. doi:10.1080/00048623.2011.10722232

- Kenny, E. (2017). Settlement in the digital age: Digital inclusion and newly arrived young people from refugee and migrant backgrounds. Carlton: Centre for Multicultural Youth (CMY). Retrieved from https://www.cmy.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Settlement-in-the-digital-age_Jan2017.pdf

- Khoir, S., Du, J., & Koronios, A. (2014, March). Study of Asian immigrants’ information behaviour in South Australia: Preliminary results. In iConference 2014 Proceedings (pp. 682–689). Berlin, Germany: iSchools.

- Leung, L. (2010). Telecommunications across borders: Refugees’ technology use during displacement. Telecommunications Journal of Australia, 60(4).58.1–.58.13. doi:10.2104/tja10058

- Leung, L. (2018). Technologies of refuge and displacement: Rethinking digital divides. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Leung, L. (2020). Digital Divides. In K. Smets, K. Leurs, M. Georgiou, S. Witteborn, & R. Gajjala (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of media and migration (pp. 79–84). London: SAGE Publications.

- Leurs, K. (2016). Digital divides in the era of widespread internet access: Migrant youth negotiating hierarchies in digital culture. In M. Walrave, K. Ponnet, E. Vanderhoven, J. Haers, & B. Segaert (Eds.), Youth 2.0: Social media and adolescence: Connecting, sharing and empowering (pp. 61–78). Cham: Springer.

- Lloyd, A. (2016). Reflection on: ‘on becoming citizens: Examining social inclusion from an information perspective. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 47(4), 316–319. doi:10.1080/00048623.2016.1256805

- Lloyd, A., Kennan, M., Thompson, K., & Qayyum, A. (2013). Connecting with new information landscapes: Information literacy practices of refugees. Journal of Documentation, 69(1), 121–144. doi:10.1108/00220411311295351

- Lloyd, A., Lipu, S., & Kennan, M. (2016). On becoming citizens: Examining social inclusion from an information perspective. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 47(4), 304–315. doi:10.1080/00048623.2016.1256806

- Mancini, T., Imperato, C., Vesco, S., & Rossi, M. (2022). Digital communication at the Time of COVID-19: Relieve the refugees’ psychosocial burden and protect their wellbeing. Journal of Refugee Studies, 35(1), 511–530. doi:10.1093/jrs/feab082

- Martzoukou, K., & Burnett, S. (2018). Exploring the everyday life information needs and the socio-cultural adaptation barriers of Syrian refugees in Scotland. Journal of Documentation, 74(5), 1104–1132. doi:10.1108/JD-10-2017-0142

- Massmann, B. (2018). Social integration in an increasingly digital world: How do refugees in the Netherlands think about the opportunities derived from information and communication technologies? ( Bachelor thesis). Retrieved from https://essay.utwente.nl/75812/

- Merisalo, M., & Jauhiainen, J. (2020). Digital divides among asylum-related migrants: Comparing internet use and smartphone ownership. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 111(5), 689–704. doi:10.1111/tesg.12397

- Ndofor-Tah, C., Strang, A., Phillimore, J., Morrice, L., Michael, L., Wood, P., & Simmons, J. (2019). Home office indicators of integration framework 2019. London: Home Office.

- O’Mara, B., Hurriyet, B., & Borland, H. (2010). Sending the right message: ICT access and use for communicating messages of health and wellbeing to CALD communities. Footscray, Australia: Victoria University.

- Reid, K. (2021). Digital inclusion of refugees resettling to Canada: Opportunities and barriers. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IOM).

- Richards, W. (2015). Need to know: Information literacy, refugee resettlement and the return from the state of Exception ( Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://research.usq.edu.au/item/q3131/need-to-know-information-literacy-refugee-resettlement-and-the-return-from-the-state-of-exception

- Settlement Council of Australia. (2020). Supporting the digital inclusion of new migrants and refugees. Retrieved from https://scoa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Supporting-the-digital-inclusion-of-new-migrants-and-refugees.pdf

- Shariati, S. (2019). The impact of information and communication technologies on the settlement of Iranian refugees in Australia ( Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://researchportal.murdoch.edu.au/esploro/outputs/doctoral/The-impact-of-Information-and-Communication/991005545318107891

- Shultz, C., Barrios, A., Krasnikov, A. V., Becker, I., Bennett, A. M., Emile, R., … Sierra, J. (2020). The global refugee crisis: Pathway for a more humanitarian solution. Journal of Macromarketing, 40(1), 128–143. doi:10.1177/0276146719896390

- Stiller, J., & Trkulja, V. (2018). Assessing digital skills of refugee migrants during job orientation in Germany. In G. Chowdhury, J. McLeod, V. Gillet, & P. Willett (Eds.), Transforming digital worlds (pp. 527–536). Cham: Springer.

- Thomas, J., Barraket, J., Parkinson, S., Wilson, C., Holcombe-James, I., Kennedy, J., … Brydon, A. (2021). Australian digital inclusion index: 2021. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT, Swinburne University of Technology, and Telstra.

- Thomas, J., Barraket, J., Wilson, C., Ewing, S., MacDonald, T., Tucker, J., and Rennie, E. (2019). Measuring Australia’s digital divide: The Australian digital Inclusion Index. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT, Swinburne University of Technology, and Telstra. doi:10.25916/5d6478f373869

- Thomas, J., Barraket, J., Wilson, C. K., Holcombe-James, I., Kennedy, J., Rennie, E., … MacDonald, T. (2020). Measuring Australia’s digital divide: The Australian digital inclusion index 2020. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT, Swinburne University of Technology, and Telstra.