Abstract

Organisations providing services for people with intellectual disabilities operate within a context of legal, moral, and institutional frameworks. This article uses an institutional framework to analyse two types of welfare organisations for people with intellectual disabilities in Sweden: inclusive education and disability arts. These two empirical cases show that because disability organisations operate at the intersection of different institutional spheres, their aims and activities are subjected to differing, and at times conflicting, expectations. Using an institutional framework helps to identify the influence of conflicting logics and external roles on the daily encounters that professionals have with people with intellectual disabilities. The findings raise ethical considerations about the moral status of people with intellectual disabilities in contemporary society.

Social disability research in Scandinavia has traditionally been associated with welfare state interventions (Gustavsson, Citation2004; Söder, Citation2013). The funding and legitimacy of this type of research has been primarily derived from its role in monitoring the effectiveness of welfare programs (e.g., Ineland, Sauer, & Molin, Citation2017; Shakespeare, Citation2006). Institutional analysis constitutes a small, growing field of inquiry. This article applies an institutional framework and scrutinises the social effects of institutional context and logics in two types of welfare organisation for people with intellectual disabilities in Sweden: inclusive education and disability arts. Both types of organisation are highly institutionalised, characterised by cultural diversity, and operate at the intersection of different institutional contexts. Ineland (Citation2016) referred to welfare organisations such as these as having hybrid structures. In this particular instance, both aim to include people who might be viewed as “unusual” or “different” (those with intellectual disabilities) within ordinary, mainstream practices (schools and theatres) outside of special arrangements. This means that professionals often need to deal with multiple and contradictory rationales and logics based on differing values in order to fit into this type of institutional environment and be perceived as legitimate in society. How do they achieve this legitimacy, and what standards should be applied to judge the quality of the success of disability organisations?

This article presents findings of two cases studies of Swedish organisations concerned with intellectual disabilities to illustrate the ways that different rationales and expectations of external contexts can influence the identities and activities of disability organisations. The article is primarily analytical in character and the analysis draws on empirical work previously published: Ineland (Citation2015) and Ineland and Silfver (Citation2018) on inclusive education, and Ineland (Citation2005) and Ineland and Sauer (Citation2014) on disability arts. The article offers new insights into disability organisations and the way analysis using institutional frameworks contributes to new understandings about organisational legitimacy and the role of professionals in intellectual disability services.

The institutional context of welfare provision in Sweden

The development of services for individuals with intellectual disabilities in Sweden has been strongly associated with the ideologies of normalisation and integration. Since the 1960s, normalisation has been a key “conceptual banner” (Tøssebro, Citation2016, p. 112) in Swedish disability policy, setting the stage for deinstitutionalisation and dedifferentiation in service provision (Ineland, Citation2016). Community living and “normal” living conditions for all citizens has been strongly emphasised since the 1990s. A “society for all” has been a guiding principle in planning and organising settings and support systems for people with disabilities (Ineland & Hjelte, Citation2018). In recent decades, Sweden has implemented far-reaching legal and policy reforms in respect of people with intellectual disabilities. Disability policy has shifted from a strong belief in large-scale and centralised public services to an increasing emphasis on individual freedom, diversity, and choice. Disability policy has been influenced by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD; United Nations, Citation2006), ratified by Sweden in 2008, which obligates the State to ensure access to support services that range from personal assistance to supporting inclusion in the community and preventing segregation (United Nations, Citation2006). Swedish disability policy has emphasised active citizenship and redistributive and regulatory measures, which have enabled citizens with disabilities to maintain security through social rights, personal autonomy, and influence in public deliberation and decision-making processes (Halvorsen et al., Citation2018; Sépulchre, Citation2018).

Legitimacy and logics in disability organisations

Public organisations providing services for people with intellectual disabilities operate within a context of legal, moral, and institutional frameworks (Ineland, Citation2015; Novotna, Citation2014). Incorporating institutional theories and concepts into research has proven value for understanding the way that regulative, normative, and cognitive elements of institutions become established as guiding principles for action and activities in organisations.

Institutions exhibit stabilising and meaning-making properties because of the processes set in motion by regulative, normative, and cognitive elements (Scott, Citation1995). These elements form institutional structures, which guide behaviour and resist change. Regulative elements constrain behaviour through laws and rule setting but also monitor actors’ conformity to them. Normative elements are more prescriptive and include values and norms that define goals and objectives and designate appropriate ways to pursue them. Cognitive elements provide a framework of sense-making, routines that are followed because they are taken for granted; other types of behaviour are usually perceived as inconceivable (Scott, Citation1995). An institutional framework for analysis implies that a broader context of social problems is important to take into account. It also helps to understand the relationship between macro-level factors (i.e., political and administrative elements) and the micro-level processes involved in the way organisations (and professionals) adjust to external pressures (Novotna, Citation2014).

Given their cultural diversity and the hybrid nature of their structures, the types of organisations illustrated in this article are required to respond to a variety of expectations and professionals with multiple and contradictory institutional logics (Friedland & Alford, Citation1991; Ineland, Citation2016; Novotna, Citation2014; Reay & Hinings, Citation2009; Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008; Thornton, Ocasio & Lounsbury, Citation2012). Institutional logics refer to socially constructed values and beliefs, which provide meaning to organisational actors (in these cases professionals) about what is rational and appropriate in their daily work with people with intellectual disabilities. Institutional logics establish a framework within which knowledge claims are situated, and provide the rules by which such claims are validated and challenged (Friedland & Alford, Citation1991; Thornton & Ocasio, Citation2008). As suggested by Pache and Santos (Citation2010), institutional logics can place professionals in challenging positions. For example, they need to deal with the dilemma of recognising difference, which has potentially negative implications for individuals associated with stigma, devaluation, and the denial of opportunities. They must also respond to people with intellectual disabilities as “agents” with equal rights and expectations, similar to other citizens, without disregarding their disability and need for adjustment and support to attain equal outcomes in a given situation or assignment (Bigby & Frawley, Citation2010). The formal structures in disability organisations are institutionally embedded, and reflect widespread understandings of social reality, which means that policies and procedures are dependent and reinforced by public opinion and societal recognition (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983). Hence, being perceived as legitimate is important to continued operation in a specific organisational field. Disability organisations, like other welfare organisations, must ensure their values and actions are congruent with socially accepted norms in order to gain or maintain legitimacy (Deephouse & Suchman, Citation2008; Meyer & Scott, Citation1994). The challenge for professionals is to maintain external legitimacy vis-à-vis the broader social context, while reaching consensus internally on how daily work should be carried out (Czarniawska-Joerges, Citation1988; Meyer & Scott, Citation1994).

Intellectual disabilities, inclusive education, and disability arts

Drawing on previous empirical research outlined above, this section illustrates how an institutional framework can be utilised in analysing the social effects of hybrid structures in disability organisations. The analysis has drawn on empirical data derived from descriptive techniques, primarily thematic content analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Inclusive education

Swedish policy has emphasised the inclusion of students with special needs in secondary and upper-secondary comprehensive schools during the last two decades (Hausstätter, Citation2014; Hotulainen & Takala, Citation2014; Ineland, Citation2016). Ideological changes have influenced the role of teachers, who are expected not only to implement ideological imperatives but also to respond to disability and special needs, not as deviances in an ableist environment but as capital and resources in the educational enterprise (Nilholm, Citation2006). A Swedish study (Ineland, Citation2015) analysed an implementation process, where the work aimed at including students with intellectual disabilities from special schools into mainstream compulsory school. The study focused primarily on how teachers involved in the project experienced the implementation process and their work to implement an inclusive environment. The findings showed that respondents supported the idea of inclusion, but simultaneously were ambivalent about how to perceive and work to achieve an “inclusive environment.” Ambitions to implement an inclusive environment were confronted by a propensity to differentiate students with and without intellectual disabilities derived from ethical considerations; inclusive education was socially constructed predominantly as a high-risk activity for students with intellectual disabilities. Although teachers from both special school and compulsory school, in everyday situations, often agreed on a consensual ideology governed primarily by practical and social considerations, most, if not all, respondents highlighted the dramatic effects of unsuccessful inclusion.

The empirical data also revealed that the idea of establishing inclusive working methods were agreed upon, but that everyday practices and more traditional pedagogical considerations provided a challenge for the idea to translate into new practices. For instance, inclusive ambitions collided with organising structures, such as the need to sort students into grades (junior, intermediate, and upper levels of compulsory school) and school forms (special school and compulsory school). In sum, the empirical data showed a twofold authority structure; respondents were confronted with contradictory institutional logics that influenced ways of thinking and acting in their daily work. The educational logic was formal or ideological, or both, and expressed through values and norms in educational policies and core concepts such as normalisation, equality, and inclusion. The social logic was pragmatic, if not informal, and emphasised individual needs and abilities, privileging differentiation and disability. This duality caused an ambiguous perception of students with intellectual disabilities (skills, abilities, vulnerability) and ways of implementing inclusive methods of working (when, how, with what social consequences). The respondents were simultaneously administrators of social order (formal policy) and expected to use their discretion to meet and respond to individual needs and preferences (informal support). Since logics are not easily changed, regardless of political rhetoric, this study helps to illustrate some of the challenges of inclusive education, whereby teachers must simultaneously maintain external legitimacy and agree internally on how daily work should be carried out.

Another study in the field of inclusive education (Ineland & Silfver, Citation2018) analysed a new phenomenon in the Swedish educational enterprise: grading students with intellectual disabilities. The Swedish Education Act (Citation2010:800), which came into effect on 1 July 2011, introduced a 5-point grading scale for students in special upper secondary schools. When applying an institutional framework for analysis, the practice of grading was both ambiguous and hybridised. As with inclusive education more generally, grades comprised two institutional logics. A logic of measurement whereby grades were objectively measurable and provided an indication of acquired knowledge among students. In comparison, there was a logic of equality, whereby grades were primarily symbolic, emphasising political ambitions about inclusive school environments in which students were not stigmatised or excluded because of disabilities. These diverse logics affected everyday professional judgement and decision-making. For example, data showed that respondents were conflicted about what to grade (“actual” measurable knowledge or knowledge that students had but found difficult to express due to reduced verbal abilities), how to grade (whether or not, or to what extent their cognitive deficits be considered), when to grade (as respondents had experienced that both motivation and performance among students with intellectual disabilities changed from one day to another), and why they should grade (ethically unsettling, considering that these grades did not have the same legal status as for students in general; i.e., they had no merit for students wanting to apply for higher education). The study argued that grades for students with intellectual disabilities, as stipulated in the Education Act (2010), were based on good intentions, and linked to logics such as normalisation and equality, but without the same legal status as regular grades; they were merely imitations of grades compared to grades for students in general.

Disability arts

The increasing number of disability art practices for people with intellectual disabilities in Sweden has been interpreted as a reflection of the decentralisation of the welfare state (Ineland, Citation2007), which gave greater autonomy to local authorities to individualise services and support (cf. Ineland, Citation2007; Sandvin & Söder, Citation1996). However, the intersection between disability and art may be framed in several ways. The Norwegian scholar Per Solvang (Citation2018) introduced four important and different discourses: art therapy, outsider art, disability art, and disability aesthetics. The current article draws on empirical research on disability art practices, which utilised art therapy and disability aesthetics as intersecting discourses (Ineland, Citation2007; Citation2015; Ineland & Sauer, 2014). Formally, these art practices were “daily activities,”, one of 10 programs offered by the provisions of the Act Concerning Support and Services for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments (LSS) (Citation1993). In Sweden, art practice within the organisational context of welfare provision operates between two institutional spheres, incorporating concepts and ideas from both. Two institutional logics, one artistic and one therapeutic, provide professionals with two templates for ambition and action (Ineland, Citation2005, Ineland & Sauer, 2014). The therapeutic logic is primarily linked to the responsibility that stemmed from the organisation being part of the welfare state and resembles what Hasenfeld (Citation1983) referred to as “people-changing processes”; that the objectives of any given activity are primarily associated with altering the social attributes and behaviours of the clients; in this case, actors with intellectual disabilities. On the other hand, the logic of art is more closely associated with cultural, creative, and artistic aspects of disability arts. The artistic logic is primarily shaped by actors and interests external to the organisations, while the therapeutic logic is derived from disability ideology and hence represents a base for action in the organisational field of disability services more generally. The analysis showed how these dual logics created ambiguity for professional decision-making. The artistic logic portrayed the social meaning of arts and aesthetics as goals in their own right, while the therapeutic logic, rooted in disability ideology, saw arts more as a method with people-changing ambitions (cf. Hasenfeld, Citation1983). For professionals, the situation was challenging; they were expected to design, manage, and lead the daily work of creating future cultural productions at the same time as being responsible for the actors’ wellbeing and putting into practice the intentions stipulated in current disability policy.

Hence, professionals faced multifaceted questions in their daily work, such as to what extent actors should be able to decide work processes, what should be the content and orientation of any given production, what should be perceived as quality and success in daily work? Hybrid structures caused ambivalence, but also made it possible to become aware of and respond to a wider spectrum of expectations. In general, disability arts in Sweden, due to its institutional context of welfare, must simultaneously grapple with producing art for an external audience as something that is meaningful in its own right, and art as a method of working to improve the wellbeing of people with intellectual disabilities. Metaphorically, it is possible to view disability arts as a balancing act between the cultural and ideological imperatives, suggesting that its legitimacy is rooted at the intersection between product and process, art and therapy.

Discussion and implications for research

This article has argued the value of applying an institutional framework in disability research. A common trait for disability organisations, evident in the two cases presented, is the tendency to operate at the intersection of different institutional spheres. Thus, organisational aims and activities are subjected to a variety of expectations and interests stemming from different environmental backgrounds. By conforming to institutional logics, organisations gain the legitimacy (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983, Citation1991; Scott, Citation1994, Citation1995) important for societal support. However, contradictory institutional logics pull organisations and professionals in different directions and promote competing ideas about what is desirable and appropriate in a given context. For example, inclusive education must respond to students both as regular students and as students with special needs. Disability arts must respond to people with intellectual disabilities as both actors or artists, or both, and clients of the welfare state.

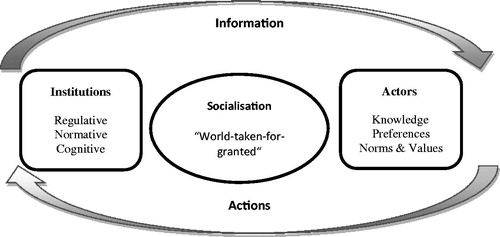

This article has also illustrated how the analytical potential of social disability research may be broadened through the application of institutional perspectives and concepts. Not least because institutional frameworks both emphasise and acknowledge actors and institutions as intertwined in organisational contexts. This external–internal relationship is shown in . The model implies a dialectical relation between institutions (and their regulative, normative, and cognitive elements) and the way actors (professionals) think and act within a scope of professional credibility. These elements form institutional structures, which guide behaviour and resist change. The model also suggests that professional activities and preferences are institutionally embedded; that institutions provide stability and meaning to their social reality.

Figure 1. Actors and institutions in disability organisations: a dialectical approach. The model was inspired by Hodgson (Citation1998).

Regulatory elements constrain behaviour through laws and rule-setting and thus provide a basis for legitimacy by connecting service provision to legal frameworks (e.g., the Act Concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments [LSS] [Citation1993]). Normative elements include values and norms, emphasise the role of social obligations, and articulate what is appropriate and desirable in a given organisational context. Hence, they are more prescriptive in character. Cognitive elements provide a framework of sense-making by shaping commonly held beliefs and assumptions that are rarely questioned. Consequently, routines are followed because they are taken for granted, while other types of behaviour are usually perceived as inconceivable (cf. Scott, Citation1995).

A suggestion has been put forward in the current article that institutional analysis has the potential to link micro-level experiences to institutional macro-level circumstances, which opens up avenues for further empirical research. First, further consideration of the pivotal role of legitimacy; how and with what social consequences do disability organisations uphold legitimacy from the outside world, while simultaneously recognising and being sensitive to individual needs and preferences? Second, how is participation and autonomy of people with intellectual disabilities understood, negotiated, and implemented in welfare organisations? Third, how and with what consequences do professionals deal with risk of people with intellectual disabilities being stigmatised, through labelling, differentiation, or compensatory arrangements, without acknowledging and responding to the fact that some individuals have, and will always have, special needs due to their disabilities? Fourth, considering the propensity of cultural diversity and hybrid structures in organisations in the field of disability, how do professionals reconcile conflicting institutional demands in daily work, and what are the driving forces for maintaining or changing their actions (cf. Meyer & Rowan, Citation1977; Meyer & Scott, Citation1994; Palthe, Citation2014; Misangyi, Citation2016)? Finally, institutional analysis helps to critically examine if and how formal structures of disability organisations conceal or mystify essential aspects of service provisions such as distribution of power, social categorisation, and underlying taken-for-granted assumptions about the roles of “client” and “professional.” In summary, by emphasising that service provision for people with intellectual disabilities is located in highly institutionalised organisational settings this article aims to encourage disability researchers to apply an analytical framework from institutional theory. An institutional framework in social disability research holds the potential for critical examination of the extent to which conflicting logics, and the pivotal role of external legitimacy, influence what is considered rational and appropriate among professionals in their daily encounters with people with intellectual disabilities. The answers to these questions are important and raise ethical issues about the moral status of people with intellectual disabilities in contemporary society.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of a larger project headed by Lotta Vikström, Professor of History, Department of Philosophical, Historical and Religious Studies, Centre for Demographic and Ageing Research (CEDAR), Umeå University, Sweden. The project is funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (Grant Agreement No. 647125), “DISLIFE Liveable Disabilities: Life Courses and Opportunity Structures Across Time.” The present study is also part of another project led by Professor Vikström; “Experiences of Disabilities in Life and Online: Life Course Perspectives on Disabled People from Past Society to Present.” The project is funded by the Wallenberg Foundation (Stiftelsen Marcus och Amalia Wallenbergs Minnesfond) [Grant agreement 2012.0141].

The article has received valuable input and benefited from meticulous and insightful critiques from the editor and the anonymous peer-review readers, for which I am most grateful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Act Concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairments (LSS) (1993). FS 1993: 387. Retrieved from: https://www.ornskoldsvik.se/download/18.44a4cd7915743e6a7e926737/1475832232342/Om%20LSS%20på%20Engelska.pdf. [Swedish]

- Bigby, C., & Frawley, P. (2010). Social work and intellectual disability: Working for change. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Czarniawska-Joerges, B. (1988). Ideological control in non-ideological organizations. New York, NY: Praeger.

- Deephouse, D. L., & Suchman, M. C. (2008). Legitimacy in organizational institutionalism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds). The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 49–77). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. doi:10.2307/2095101

- DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1991). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. In W. Powell & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Friedland, R., & Alford, R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In W. Powell & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Gustavsson, A. (2004). The role of theory in disability research – springboard or strait-jacket. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 6(1), 55–70. doi:10.1080/15017410409512639

- Halvorsen, R., Hvinden, B., Beadle-Brown, J., Biggeri, M., Tøssebro, M., & Waldschmidt, A. (2018). Understanding the lived experiences of persons with disabilities in nine countries. London: Routledge.

- Hasenfeld, Y. (1983). Human service organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hausstätter, R. S. (2014). In support of unfinished inclusion. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(4): 424–434. doi:10.1080/00313831.2013.773553

- Hodgson, G. M. (1998). The approach of institutional economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 36, 166–192.

- Hotulainen, R., & Takala, M. (2014). Parents views on the success of integration of students with special education needs. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 18(2), 140–154. doi:10.1080/13603116.2012.759630

- Ineland, J. (2015). Logics and ambivalence: Professional dilemmas during implementation of an inclusive education practice. Education Inquiry, 6(1), 26157–26171. doi:10.3402/edui.v6.26157

- Ineland, J. (2005). Logics and discourses in disability arts in Sweden: A neo-institutional perspective. Disability & Society, 20(7), 749–762. doi:10.1080/09687590500335766

- Ineland, J. (2007). Mellan konst och terapi. Om teater för personer med utvecklingsstörning. [Between art and therapy: Theatre and people with intellectual disabilities]. Institutionen för socialt arbete, Umeå universitet. Akademisk avhandling, Rapport nr 56 [Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University, Department of Social Work].

- Ineland, J. (2016). Hybrid structures and cultural diversity in welfare services for people with intellectual disabilities. The case of inclusive education and disability arts in Sweden. ALTER. European Journal of Disability Research, 10(4), 289. doi:10.1016/j.alter.2016.06.002

- Ineland, J., & Hjelte, J. (2018). Knowing, being or doing? A comparative study on human service professionals' perceptions of quality in day-to-day encounters with clients and students with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities: Joid, 22(3), 246–261. doi:10.1177/1744629517694705

- Ineland, J., & Sauer, L. (2014). Cultural practices for people with intellectual disabilities – an educational challenge. [Kulturella verksamheter för personer med utvecklingsstörning – en pedagogisk utmaning.] Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige [Educational research in Sweden], 19(1), 32–53.

- Ineland, J., Sauer, L., & Molin, M. (2017). Sources of job satisfaction in intellectual disability services: A comparative analysis of experiences among human service professionals in schools, social services, and public health care in Sweden. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities, 43, 421–430. doi:10.3109/13668250.2017.1310817

- Ineland, J., & Silfver, E. (2018). Bedömning och betygssättning av elever med utvecklingsstörning – attityder och erfarenheter från pedagogers perspektivs. [Assessing and grading students with intellectual disabilities: Attitudes and experiences from teachers’ perspective]. Pedagogisk Forskning i Sverige, 1(2), 107–126.

- Meyer, J., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(1), 55–77. doi:10.1086/226550

- Meyer, J. W., & Scott, R. (1994). Institutional environments and organizations. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Misangyi, V. F. (2016). Institutional complexity and the meaning of loose coupling: Connecting institutional sayings and (not) doings. Strategic Organization, 14(4), 407–440. doi:10.1177/1476127016635481

- Nilholm, C. (2006). Special education, inclusion and democracy. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 21(4), 431–445. doi:10.1080/08856250600957905

- Novotna, G. (2014). Competing institutional logics in the development and implementation of integrated treatment for concurrent disorders in Ontario: A case study. Journal of Social Work, 14 (3), 260–278.

- Pache, A.-C., & Santos, F. (2010). When worlds collide: The internal dynamics of organizational responses to conflicting institutional demands. Academy of Management Review, 35(3), 455–476. doi:10.5465/amr.35.3.zok455

- Palthe, J. (2014). Regulative, normative, and cognitive elements of organizations: Implications for managing change. Management and Organizational Studies, 1(2), 59–66. doi:10.5430/mos.v1n2p59

- Reay, T., & Hinings, C. R. (2009). Managing the rivalry of competing institutional logics. Organization Studies, 30(6), 629–652. doi:10.1177/0170840609104803

- Sandvin, J., & Söder, M. (1996). Welfare state reconstruction. In Tøssebro, J., Gustavsson, A. & Dyrendahl, G. (eds.), Intellectual disabilities in the Nordic welfare states: Policies and everyday life. Oslo: Norwegian Academic Press.

- Scott, W. R. (1994). Institutions and organizations: Toward a theoretical synthesis. In R. Scott & M. Meyer (Eds.) Institutional environments and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Scott, W. R. (1995). Institutions and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Sépulchre, M. (2018). Tensions and unity in the struggle for citizenship: Swedish disability rights activists claim “Full Participation! Now!”. Disability & Society, 33(4), 539–5561. doi:10.1080/09687599.2018.1440194

- Shakespeare, T. (2006). Disability rights and wrongs. London: Routledge.

- Söder, M. (2013). Swedish social disability research: A short version of a long story. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 15(sup1), 90–107. doi:10.1080/15017419.2013.781961

- Solvang, P. K. (2018). Between art therapy and disability aesthetics: A sociological approach for understanding the intersection between art practice and disability discourse. Disability & Society, 33(2), 238–253. doi:10.1080/09687599.2017.1392929

- Swedish Education Act. (2010:800). Svensk författningssamling SFS Skollag (2010: 800) [Swedish Code of Statutes Education Act (2010: 800)], Utbildningsdepartementet [Department of Education].

- Thornton, P. H., & Ocasio, W. (2008). Institutional logics. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 99–129). London: Sage.

- Thornton, P. H., Ocasio, W., & Lounsbury, M. (2012). The institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, structure and process. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Tøssebro, J. (2016). Scandinavian disability policy: From deinstitutionalization to non-discrimination and beyond. ALTER. European Journal of Disability Research, 10(2), 111–123. doi:10.1016/j.alter.2016.03.003

- United Nations. (2006). United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: UN. Retrieved from: www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml