?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In most rural communities, women are the sole managers of water supply and sanitation and determine household water management choices and practices. This study investigated the perceptions and household water management practices among womenfolk within rural communities located in the Central Tongu district and the Ada East districts of Ghana. Data collection instruments included household surveys, direct observation and focus group discussions of women within the study communities. The data were analysed using statistical tools embedded in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software. Results indicate that socio-demographic factors such as age, education, occupation and cost of water sources shaped household water management decisions. Furthermore, respondents’ perception of climate variability and climate adaptation was low and this, in turn, influenced household water management practices. The paper recommends that capacity building workshops be organized for rural women within the study communities to equip them with the skills to increase their income and in due course, improve their water management choices. Additionally, we suggest the promotion of climate variability and adaptation sensitization workshops of suitable household water management adaptation measures by government and Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) among rural communities.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Women traditionally are the managers of household water and sanitation. This research article focuses on the household water management choices and practices of women within four rural communities in Ghana. It was found that age, education, occupation, the cost of water sources, and respondents’ perceptions of climate variability and adaptation influenced household water choices and practices among rural women. Organizing adult literacy trainings and capacity building workshops for rural women within the study communities can help equip rural women with the knowledge and skills to increase their income and eventually improve their water management choices. Moreover, the promotion of education and awareness campaigns on climate variability and adaptation sensitization workshops by government and Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) among rural communities will help improve the understanding of climate variability and help in the adoption of suitable household water management adaptation measures by rural women.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

In most rural communities, women are the sole managers of water supply and sanitation services and are responsible for determining sources and hygienic quality (Ray, Citation2007). Water is an indispensable asset, and in these rural households, it is needed not only for drinking but also for cleaning, cooking and food production including livestock keeping (Fan, Liu, Wang, Geissen, & Ritsema, Citation2013) As primary managers, women are not only responsible for water sourcing, but are also responsible for informal healthcare that may result from poor water quality (Kongolo & Bamgose, Citation2002; WHO & UNICEF, Citation2016). Thus, water provision and for that matter, water and public health considerations become very relevant for women in fulfilling their socially constructed gender roles at the local level (Nzengya & Aggarwal, Citation2013). What is more alarming, when women’s access to water is restricted, it leaves them with no choice than to accept lower quality water and this situation is not different for public health issues.

In recent times, research has shown that there are several challenges to women’s access to water and water management. Studies show that these challenges, including distance to suitable water sources (Nzengya & Aggarwal, Citation2013), time and cost constraints (Van Houweling, Hall, Diop, Davis, & Seiss, Citation2012) water scarcity (Arnell et al., Citation2014), among others all affect their access to water. However, increasingly, climate drivers like changes in the hydrological cycle and non-climatic drivers such as population increase, socio-economic influences and land-use change, are causing major shifts leading to a reduction in the sustainability of water sources. According to Arnell et al. (Citation2014), the reliability of water supply is predicted to decline as a result of increased variability of available surface water. Likewise, a number of studies also posited that climate change and climate variability will lead to a reduction in raw water quality (Bates, Kundzewicz, Wu, & Palutikof, Citation2008; Campbell-Lendrum et al., Citation2014; Webersik, Citation2010).

Also, with water availability a key determinant of health, particularly in developing countries, studies show that over a million avoidable deaths could be prevented with universal access to water and sanitation management (Montgomery, Bartram, & Elimelech, Citation2009). Evidence suggests that participation is a very important ingredient for achieving desired results; thus with the involvement of women—traditionally placed close to the knowledge regarding natural resource management especially in rural communities—it is imperative their views are included on key issues regarding water and its management. Further, the importance of involving women in water and public health management has been receiving international recognition from the UN more expressly in the Sustainable Development Goals (Boateng et al., Citation2013).

In Ghana, the role women play in the education, management and safeguarding of water was highlighted in its effort to achieve its MDG target for access to safe drinking water (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2015). With the succeeding SDGs, the enhanced role of women has been championed across water management endeavours by various Government and Non-governmental Organizations. However, it is important to note that climate change and climate variability can derail all progress made in the water and sanitation sector and public health management in Ghana especially in the rural areas (Asante & Amuakwa-Mensah, Citation2015). Additionally, water management practices can be impacted not only by climatic factors but also by socio-economic changes that may come about as a result of climate change and climate variability (Parry, Citation2007).

Currently, only a few studies have focused on the linkage between climate variability, water availability and household water management challenges affecting rural women in Ghana (Ministry of Environment Science, Technology and Innovation Ghana [MESTI], Citation2013). To plan for future climate and health implication on local communities, guided research on the effects climate variability could have on rural water management practices is needed to help build resilience in local communities. Thus, this paper sought to;

Examine the factors influencing household water management decisions among rural womenfolk.

Examine household water management practices adopted by rural women as a result of changing climate variability.

Make recommendations that will enhance household water management among rural women in the face of changing climate variability.

2. Conceptual framework

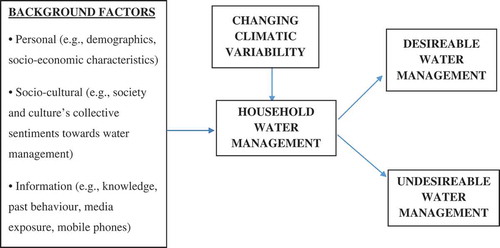

The conceptual framework (Figure ) for the study of household water management practices among rural women is adapted from Lowe et al. (Citation2015), Household Water Consumption model. The study perceived rural household water management is influenced by personal (demographic, socio-economic characteristics), Socio-cultural (society and cultural collective sentiments towards water usage and conservation) and Information (knowledge, past behaviours, media exposure, mobile phones) as well as environmental factors (changing climatic variability). These elements consciously influence the resulting management practices which lead to desirable or undesirable water management practices in the face of changing climatic variability. Conversely, we conceive that most rural womenfolk decide to carry out household water management practices as a strategy to safeguard water and enhance its use.

Figure 1. A conceptual model of household water management practices adapted from Lowe, Lynch, and Lowe (Citation2015).

3. Profile of the study area

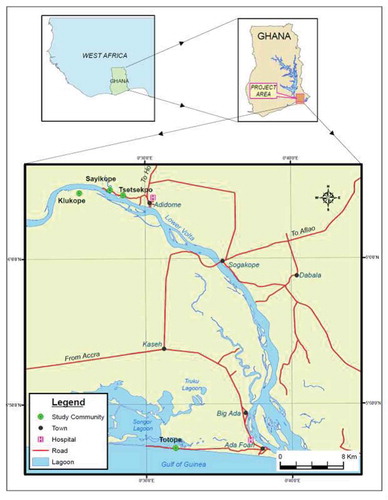

The study areas were Tsetsekpo, Sayikope and Klukope in the Central Tongu District in the Volta Region and Totope as a control community in the Ada East District of the Greater Accra region shown in Figure . All study sites were selected based on the presence or absence of potable drinking water, the availability of a health facility, and the socio-demographic characteristics of the community inhabitants.

4. Tsetsekpo, Sayikope and Klukope

4.1. Area characteristics

Tsetsekpo, Sayikope and Klukope are rural settlements located in the Central Tongu district of the Volta region of Ghana. They lie within latitudes 5047N to 60N and longitude 0025 E to 0045E. The climate is tropical and is greatly influenced by the South–West Monsoons from the south Atlantic sea and the dry Harmattan winds from the Sahara. There are two rainy seasons, the major rainy season from mid-April to early July and the minor rainy season from September to November. Average annual rainfall is 900−1100 mm, mean temperature is 27ºC and average relative humidity is 80%. Geologically, the area is characterized by clay, nepheline, gneiss, sand, granite and oyster shell deposits. Tsetsekpo, Sayikope and Klukope are located along the River Volta System in the Lower Volta Basin.

4.2. Economic activities

Agriculture is the leading sector in the economy in this area. Fishing used to be the main occupation of inhabitants in the study area. The presence of water weeds and siltation over much of the lower Volta as a result of the construction of the Akosombo and Kpong dams has adversely affected the ecology of the area. Subsequently, this has led to the demise of the fishing industry and oyster farming in the area (CTDA, Citation2010). According to the study profile, most of the indigenes have shifted to producing maize and vegetables on a small scale. Farming is mostly dependant on simple labour-intensive production techniques using indigenous farm implements and indigenous farming practices. The use of rudimentary agricultural practices and the lack of deposition of alluvial silt on the flood plains have resulted in low farm yields. The lack of deposition of alluvial silt is due to the cessation of the annual flooding of the Volta River. Also, the lack of appropriate post-harvest handling leads to high levels of post-harvest losses. Most farmers have hence turned to cattle rearing as an alternative source of income. This has brought about massive over-grazing resulting in soil erosion and degradation. The situation is further impaired by poor farming practices adopted by the people which include over-cultivation and bush burning. Other inhabitants are also involved in charcoal production or small-scale mining of oyster shells as alternative sources of income. It is also important to note that wood fuel and charcoal are the main sources of energy for cooking. Charcoal burning, fuelwood collection, bushfires and poor farming practices have led to an alarming rate of deforestation in the area.

4.3. Sources of water

According to the District Assembly (CTDA, 2010), the main sources of water supply in the District are wells, dams, rainwater and the Volta river. The Volta River serves as an important source of water supply to the towns and villages, which are located along its banks. Dams, wells and streams, however, supply villages situated further from the river. With low rainfall and, these sources of water supply tend to be unreliable particularly during lengthy dry seasons. Pipe-borne water has now however been provided to the villages of Tsetsekpo and Sayikope through a DANIDA funded water project, and the villagers use this water source together with the Volta River. Klukope, on the other hand, is still wholly dependent on wells and the Volta River.

5. Totope

5.1. Area characteristics

Totope is located in the Ada East district which is in the Eastern part of the Greater Accra Region. Its coordinates are Latitudes 5°45 South and 6°00 North and from Longitude 0°20 West to 0°35 East. The village is situated on a low sand dune between the Songor lagoon and the sea. Due to the proximity of the sea and other waterbodies, humidity is relatively high at about 80%. The temperatures in the area range between 23°C and 28°C, but this can further increase to 33° during the dry season. Average inter-annual rainfall is also about 750 mm.

5.2. Economic activities

The major occupations of the inhabitants include farming, fishing, fish processing and livestock rearing.

5.3. Sources of water

Despite being surrounded by the Songor lagoon and the sea, pipe-borne water is the only available source of water for drinking and all household needs due to the saline content of the surrounding waterbodies.

6. Materials and methods

6.1. Study design

For the purpose of this study, the research design employed both quantitative and qualitative approaches to data collection. Quantitatively, a cross-sectional survey was conducted to administer a semi-structured questionnaire to women in selected households. On the qualitative side, some of the community women were engaged in focus group discussions. The use of a mixed method was to complement each other and reinforce the outcome of the analysis.

7. Sample and sampling procedure

The study population consisted of four communities. Three (Tsetsekpo, Sayikope and Klukope) within the Central Tongu district and one (Totope) to serve as a control community in the Ada-East district. The four communities were purposively selected due to their homogenous socio-demographic characteristics. According to the databases of both the Central Tongu district Assembly (CTDA) and the Ada East Municipal Assembly (AEDA), all the selected communities have similar characteristics of water-related issues. Based on the 2010 population census figures (Ghana Statistical Service [GSS], Citation2010), 1,200 households were present in the study communities. A total of 301 respondents were interviewed. One hundred and fifty respondents were interviewed in Totope, 64 in Tsetsekpo, 37 in Sayikope and 50 respondents in Klukope.

Using the formula below, a total of 301 household respondents were sampled:

where “N” represents the total households within all four communities and “e” is the margin of error.

But as the total number of households were 1,200,

The sample size for the various communities was arrived at by proportionate sampling. This was calculated with the formula:

For example, calculating the sample size for Totope:

This was then repeated for all the other communities. The sample size of the different communities that were selected are shown in Table

Table 1. Name of communities, number of households and number of questionnaires administered.

To select respondents from households within the communities, systematic sampling was used. To arrive at the interval between the houses in which respondents would be drawn (that is the Xth number) the following formula was used.

This procedure was repeated for all the communities. The total number of households surveyed was limited both by the availability of funds and time constraints. However, it was ensured that responses were a representative sample of households across the selected communities (Neumann et al., Citation2014).

8. Study participants

Even though households were used as the unit of sampling in this study, women were the sole respondents interviewed as representatives of households in this study. This is because women normally have the primary obligation of managing the households’ water and this makes them generally more knowledgeable about issues pertaining to household water practices (Peletz, Citation2006). Also, women comparatively suffer more than men during water crises, therefore, it was appropriate that their views were taken.

9. Ethical considerations

Participants in the study were asked for their informed consent before interviews took place. They were informed of the freedom to withdraw from the study at any time. Furthermore, permission was sought from the heads of communities before the study commenced.

10. Data collection

For the survey, the questionnaires were first pretested to check for errors and inconsistencies, with some womenfolk in Sota, a rural community in Dodowa with similar characteristics to the study population. After pre-testing, the research instruments were revised which was used to gather the information from the women in Tsetsekpo, Sayikope, Klukope and Totope.

The revised questionnaire contained both closed and open-ended questions and was administered to the women in the various households. The questionnaire was to gain information on the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, including their ages, educational and income levels, marital status among others. In addition, information on their knowledge and perception of climate variability and attitude towards water management practices was also collected. The interviews were carried out with the assistance of trained research assistants fluent in the local language.

To gain deeper insights into the local perceptions of climate variability on household water management, a qualitative component, in the form of focus group discussions (FGDs) with women in the communities were held in addition to direct observation. Conversely, three FGDs were conducted in Totope, Sayikope and Tsetsekpo. Each FGD had 8 to 20 adult females in each group to provide an in-depth understanding on the socio-cultural and economic issues with respect to issues of their perceptions on climate change and climate variability, water management practices and decisions. FGDs were organized in the villages’ central meeting area. With the agreement of the interviewees, all interviews and FGDs were recorded both in notes and recordings, and later transcribed.

Direct observation was done to observe first-hand the water usage and sanitation practices and also to ascertain the validity of answers provided on the structured interview guide (Adubofour, Obiri-Danso, & Quansah, Citation2013; Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner, Citation2007; Kraan, Citation2009). To clarify certain practices, for example, water storage, further questioning was done using an unstructured interview guide. This was because some of the questions asked had to deal with attitudinal practices relating to sanitation and health; therefore, it was necessary to ensure the accuracy of the answers given during questionnaire administration.

11. Data analysis

The administered interview schedules from the survey were carefully edited and coded. The edited data were then processed and analysed with the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS version 21). Similarly, for the qualitative component, information gathered from the focus group discussions was transcribed from the recorder and analysed based on content analyses. The two approaches enabled the study to provide complete information on the issues.

12. Results and discussion

12.1. Factors influencing household water management decisions among rural womenfolk

The study identified a number of socio-economic, demographic and perception variables that influenced household water management decisions among rural women in a changing climate. The variables were age, education and training, type of occupation and cost of water sources. These characteristics of the respondents were examined in order to provide a basis for differentiating between responses of influencing factors affecting household water management decisions.

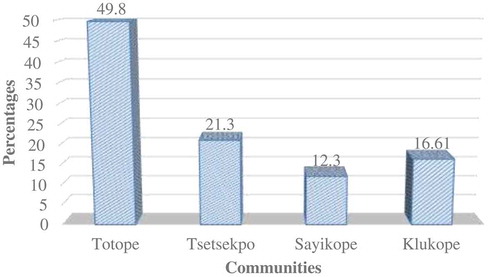

From the study, a total of 301 respondents made up of women were interviewed in the four communities for the survey. Forty-nine point eight (49.8%) were from Totope, with 21.3%, 12.3% and 16.61% being from Tsetsekpo, Sayikope and Klukope, respectively (Figure ).

13. Age

Most of the respondents in the communities surveyed were between the ages of 31 and 40 years with the oldest being 87 and the youngest 20. In line with our findings, Dick and Gao (Citation2013) also found the 31–40 age bracket to be the most prevalent age range for rural women in Sierra Leone and Kongolo and Bamgose (Citation2002) in rural South Africa. Consequently, the age structure plays a major role in household water management decisions of rural women. According to Makutsa et al., (Citation2001), younger women are more open to change than their elders and more likely to adopt improved management decisions, particularly concerning point-of-use water storage and treatment methods. A confirmation of this statement was made by one of the respondents within the 31–40 age bracket from the focus group discussion when she said, “To be frank, I only drink from the Volta River and nowhere else. This is because this is what our ancestors have been drinking and using since time memorial and they survived just fine. So why should we change? It is all this change that is angering the gods and leading to so many problems in society”.

14. Education

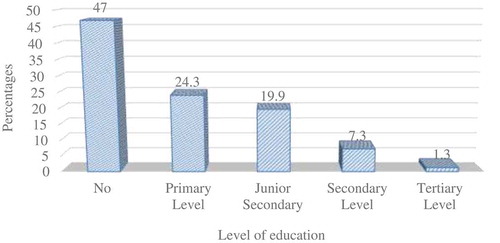

Almost half (47%) of all respondents had no form of formal education. However, 24.3% had obtained the primary level of education, 19.9% had the junior secondary level of education, 7.3% had the secondary level of education and 1.3% the tertiary level of education. Results from the study as shown in Figure indicated that the level of educational attainment in the areas surveyed was generally low. Chi-square analysis between educational levels of respondents and water management decisions showed a significant association at a p value of 0.05 (Table ). This finding correlates with research by Kongolo and Bamgose (Citation2002) who suggested that women’s literacy levels have a role to play in their access to information (Akbar, Minnery, Van Horen, & Smith, Citation2007) and participation (Were et al., Citation2006). Therefore, given the rural woman’s primary responsibility of managing household or domestic chores in these communities, the lack of literacy and some form of water management training will likely marginalize women with little or no education.

Table 2. Summary of Chi-square analysis between socio-economic factors of respondents and household water management choices.

15. Type of occupation

Most of the respondents worked in the informal sector (89%) with only 3% having white-collar jobs. Eight per cent (8%) were also unemployed or pursuing an education (Table ). The most common occupation among respondents was farming (30.9%) followed by fish processing (27.9%) with the least common occupation among respondents being tailoring (1.3%). As all the study sites were predominantly rural, a large majority of the respondents were employed in the agricultural sector informally as subsistent farmers. According to Elum, Modise, and Marr (Citation2017), women are generally more involved in agricultural production in Africa than men. This is consistent with findings by Service (Citation2014) that in Ghana, mostly women are employed as skilled agriculture and fishery workers in the rural communities. Elum et al. (Citation2017) and Hart and Aliber (Citation2012) also subsequently established in their study that almost two-thirds of individuals involved in agriculture production in South Africa were women. The sources of occupation have a part to play in determining the well-being of the households and decisions made by women folk on household water management. From the study findings, this paper established, that the occupation of respondents had an association with which decisions they took in relation to household water management (Table ). Further explaining the phenomenon, studies by the International Labour Organization (Citation2004) and Koskei, Koskei, Koske, and Koech (Citation2013), proposed that rural small-scale farmers seldom attract substantial income for family needs. Thus, the low incomes of farm households are closely linked with the affordability of basic services such as access to potable water and education.

Table 3. Summary of employment and occupation characteristics.

A majority of the respondents (68%) interviewed were farmers. Agriculture is an area particularly vulnerable to climatic variability in Ghana (Asante & Amuakwa-Mensah, 2015). This issue is further compounded by the use of inadequate tools and water management practices in rain-fed crop production (Müller-Kuckelberg, Citation2012). One respondent from the focus group discussion in Sayikope restated this view when she said “Without rain, all the crops wither and die. Without the rain to water our crops, we cannot get money to trade or even go to school to improve ourselves and get money. We really need irrigation machines to help us on our farms”. Farm yields are directly impacted as a result of weather elements impacts on agricultural production and financial gain and therefore can affect household water management decisions (Karfakis et al., Citation2012).

16. Income

In all four communities, households had an average monthly income of GH₵ 334.93 (71 US dollars), which is reportedly lower than the GH₵ 525 (111.3 US dollars) of rural cocoa-growing households suggested by Smith, Anker, and Anker (Citation2017). Cooke, Hague, and McKay (Citation2016) and Smith et al. (Citation2017) posited that this might be because cocoa farmers and farmers of cash crops earn more than farmers engaged in food crop production due to the value of cash crops. According to these authors, the economic status of households is closely linked with the affordability of services such as water (Kimenyi & Mbaku, Citation1995; Kremer et al., Citation2011). Thus, women with no reliable source of income are likely to use water from unimproved sources and therefore stand a higher risk of facing water management issues.

Household expenditure (proxy of household welfare) is the principal factor of household water security; thus, lower income means households are likely to rely on unimproved sources of water because it might be cheaper (Kimenyi & Mbaku, Citation1995; Kremer et al., 2011). Likewise, the results from the study as shown in Table revealed an association between the income level of respondents and their household water choices significant at a p value of 0.05. In line with our findings, Lawrence, Meigh, and Sullivan (Citation2002) concluded that even improved water sources might be provided, it is possible that people may remain “water poor”. This may not be because there is no safe or potable water in their area, but because they are “income poor” and hence cannot afford potable water. This reiterates the view of some of the respondents from the focus group discussions held in Tsetsekpo who said that “River Volta is the source of water that is used the most. This is because without money or funds, the pipe-borne water cannot be bought. This also explains why we use the pipe-borne water for drinking and water from the River Volta for everything else”.

17. Cost of the water source

Table shows that the main water sources studied in the communities were public pipe-borne points, the Volta River and the Aklakpa stream. Some of these water sources could be accessed free of charge whereas others had to be paid for before being utilized. In one community (Klukope), since the only source of water was the Aklakpa stream, the cost of the water source had no influence on women’s household water management choices and decisions. Likewise, in the control community (Totope) with the only source of water being pipe borne water, women had no other choice but to purchase it hence cost was also not an influencing factor in their household water choices.

Table 4. Summary of sources of water used within the communities

In the other communities (Tsetsekpo and Sayikope) however, there were options between a paid water source (pipe borne water) and a free source (River Volta). In these communities, women reported, that the costs of water tended to sway their choice of a water source. Pipe borne water was priced at (0.29Ghc/cm3 or US$0.07/cm3) and the women complained that this was too expensive (Table ). Even though this figure might seem affordable, it is important to take into account that according to the municipal profile, poverty is widespread as most inhabitants are rural smallholder farmers with relatively meagre incomes (CTDA, 2010). One of the women re-emphasized this point when she said “Even though we have pipe borne water in our village. It’s not cheap. At the moment, water in a 34cm3 bucket, costs 50Ghp and 1Ghc for a plastic basin. We wish it could stay the same price otherwise; we would be unable to pay for pipe-borne water. We can’t spend all our money on water. If the price should increase, it would be extremely difficult to continue using pipe-borne water. Even now at 50Ghp, it is extremely expensive, and it makes it impossible for some people in Tsetsekpo to use pipe-borne water”. Another respondent also said “To be honest, if the price should go any higher, I will, in fact we will all go back to using the River Volta”. This observation is consistent with Van Houweling et al. (Citation2012), who assert that water costs tend to influence the water choices and management decisions utilized by rural women.

17.1. Household water management practices adopted by rural women as a result of changing climate variability

This paper identified a number of household water management practices adopted by rural women in a changing climate. It was recognized that perceptions of climatic factors and adaptation options had a role to play in which kind of practices women chose to use in a changing climate.

17.2. Women’s perception of climate change and climate variability

The data gathered from the study revealed all respondents perceived there were some changes in climate variability and climate change within their environment. Some of the occurrences they provided as evidences of climate variability and climate change included; low crop yields, low and erratic rainfall, excessive sunshine and heat intensity, late start of the farming period, increase in numerous diseases, loss of the forest cover now as compared to forest vegetation from 10 years ago among other suggestions. It is observed, even though a few (7.3%) attributed the changes in climate variability to an act of God as punishment for wrongdoing by man, many could not associate these changes with any concept (Table ). This is therefore consistent with an assumption by Gyampoh et al., (Citation2009) that even though indigenous people may not understand the concept of climate variability or climate change, they can truly witness and feel its effects.

Table 5. Summary of sources of water used within the communities and the costs.

Table 6. Summary of respondents’ perception of climate change and climate variability

17.3. Women’s perception of adaptation to climate change and climate variability

Even though some of the women acknowledged the presence of climate variability, only a few of them had adopted any practices to adapt or planned to take measures to adapt in terms of household water management (Table ). It should be taken note of that for the purpose of this paper, adaptation is in the context of household water management.

Table 7. Respondents’ views of adapting to climate variability.

This paper agrees with Benebere, Asante, and Odame Appiah (Citation2017), who suggested that people with little or no formal education have no idea of adapting to climate variability because they may have had no prior sensitization on adaptation to climate variability. This may explain why so many women had taken no actions to adapt to climate variability. According to the women, none of them had ever been to a climate change or climate variability sensitization workshop. Alternatively, it is likely the women might have been taking measures to adapt in their own small way but because they did not understand the concept of climate adaptation did not know they were adapting.

17.4. Women’s household water practices as a means of adapting to climate change and climate variability

The data gathered revealed that a large proportion of women (88.7%) had no idea of which household water practices to implement as a means of adapting to climate variability. On the contrary, less than 20% were involved in any practice of adaptation (Table ).

Table 8. Summary of household water practices as a means of adapting to climate change and climate variability within the communities.

Doss and Morris (Citation2001) emphasize that rural folk must first be aware that technology exists and recognize it is profitable for them to be able to adapt their water management practices to climate variability or climate change.

It is worth noting that a few women mentioned the increased number of storage vessels as a household water management option. Vincent et al., (Citation2013) define coping mechanisms as short-term strategies typically designed to maintain survival. The women’s choice of increased water vessels can, therefore, be deemed as a coping mechanism since it will likely not withstand the impacts of climate variability in the long term.

Even though rain-water harvesting (RHW) is a globally recognized adaptation option, it was observed that less than 1% of women were applying it. This observation is in agreement with Kahinda, Taigbenu, and Boroto (Citation2010) who assert that RWH currently has limited application in Africa despite the great potential it has of lessening the impacts of climate change as an adaptation option.

18. Conclusions

From the perspective of the objectives, the following conclusions were drawn. Socio-economic and demographic variables such as age, education, type of occupation, income levels and the cost of the water exerted influence directly or indirectly on household water management decisions among rural women within the study communities. Also, we observed that the women’s perceptions of changing climatic factors were quite low. Moreover, it was discovered that most of the women did not engage in any active household water management practices to adapt to climate change. Lastly, a few respondents who thought they were adapting, were not but actually employing coping mechanisms.

19. Recommendations

On the basis of the findings of the study, the paper recommends the organization of adult literacy trainings and capacity building workshops for rural women within the study communities. These learning and training workshops will help equip rural women with the knowledge and skills to increase their income and in due course to improve their water management choices (Ogundele, Akingbade, & Akinlabi, Citation2012)

In addition, we suggest the promotion of climate variability and adaptation sensitization workshops by the government and Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) among rural communities as the study revealed that the perceptions of climate change by rural women are influenced by their observation and access to information. Hence, climate education will vastly improve the understanding of climate variability and help in the adoption of suitable household water management adaptation measures by rural women.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed substantially and equally to the completion of this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the research assistants who helped with the data collection and The Open Society Foundation under the “B4C—Climate Change and Sustainable Development” project for partly funding this study. We would also like to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Karyn E. Quansah

Karyn E. Quansah is co-founder and research assistant at Zerowerks, a non-profit organisation based in Ghana. Her research interests include environmental sustainability, water, sanitation and hygiene (WSH) with an empirical focus on climate change and climate variability especially among rural inhabitants.

References

- Adubofour, K., Obiri-Danso, K., & Quansah, C. (2013). Sanitation survey of two urban slum Muslim communities in the Kumasi Metropolis, Ghana. Environment and Urbanization, 25(1), 189–16. doi:10.1177/0956247812468255

- Akbar, H., Minnery, J. R., Van Horen, B., & Smith, P. (2007). Community water supply for theurban poor in developing countries: The case of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Habitat International, 31(1), 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2006.03.001

- Arnell, N. W., Benito, G., Cogley, J. G., Döll, P., Shadrack, J., & Mwakalila, S. (2014). IPCC WGII AR5 chapter 3: Freshwater resources. UK: University of Cambridge Press

- Asante, F., & Amuakwa-Mensah, F. (2015). Climate change and variability in Ghana: stocktaking. Climate, 3(1), 78-99.

- Bates, B. C., Kundzewicz, Z. W., Wu, S., & Palutikof, J. P. (2008). Climate Change and Water: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Geneva: IPCC Secretariat.

- Benebere, P., Asante, F., & Odame Appiah, D. (2017). Hindrances to adaptation to water insecurity under climate variability in peri-urban Ghana. Cogent Social Sciences, 3(1), 1394786. doi:10.1080/23311886.2017.1394786

- Boateng, J. D., Brown, C. K., & Tenkorang, E. Y. (2013). Socio-economic status of women and its influence on their participation in rural water supply projects in Ghana. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 2(2), 871-890.

- Campbell-Lendrum, D., Chadee, D., Honda, Y., Liu, Y., Olwoch, J., Revich, B., & Rainer, S. (2014). IPCC WGII AR5 chapter 11: Human health: Impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. UK: University of Cambridge Press.

- Central Tongu District Assembly (2010). District Assembly profile. Retrieved from http://www.ghanadistricts.com/Home/District/176

- Cooke, E., Hague, S., & McKay, A. (2016). The Ghana poverty and inequality report. ASHASI, UNICEF, University of Sussex: https://www.unicef. org/ghana/Ghana_Poverty_and_Inequality_Analysis_FINAL_Matc h_2016 (1). pdf

- Dick, T. T., & Gao, J. (2013). The potential of women’s organization for rural development in Sierra Leone. Evropejskij Issledovatel, 42(2–3), 487–496.

- Doss, C. R., & Morris, M. L. (2001). How does gender affect the adoption of agricultural innovations? The case of improved maize technology in Ghana. Agricultural Economics, 25(1), 27–39. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2001.tb00233.x

- Elum, Z. A., Modise, D. M., & Marr, A. (2017). Farmer’s perception of climate change and responsive strategies in three selected provinces of South Africa. Climate Risk Management, 16, 246–257. doi:10.1016/j.crm.2016.11.001

- Fan, L., Liu, G., Wang, F., Geissen, V., & Ritsema, C. J. (2013). Factors affecting domestic water consumption in rural households upon access to improved water supply: Insights from the Wei River Basin, China. PLoS ONE, 8((8)), e71977. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0071977

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2010). Population and housing census. Ghana: Accra.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2014). Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 6 (GLSS 6), Main Report. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service.

- Gyampoh, B. A., Amisah, S., Idinoba, M., & Nkem, J. (2009). Using traditional knowledge to cope with climate change in rural Ghana. Unasylva, 60(281/232), 70-74.

- Hart, T., & Aliber, M. (2012). Inequalities in agricultural support for women in South Africa. Human Sciences Research Council policy brief, November, 2012.

- International Labour Organization. (2004). Working Out Of Poverty in Ghana: The Ghana Decent Work Pilot Programme. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

- Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2), 112–133. doi:10.1177/1558689806298224

- Kahinda, J. M., Taigbenu, A. E., & Boroto, R. J. (2010). Domestic rainwater harvesting as an adaptation measure to climate change in South Africa. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C, 35(13–14), 742–751. doi:10.1016/j.pce.2010.07.004

- Karfakis, P., Lipper, L., Smulders, M., Meybeck, A. L. J., Redfern, S., & Gitz, V. (2012, April 23–24). The assessment of the socioeconomic impacts of climate change at household level and policy implications. Paper Presented At The Building Resilience For Adaptation To Climate Change In The Agriculture Sector. Proceedings of a Joint FAO/OECD Workshop, Rome, Italy.

- Kimenyi, M. S., & Mbaku, J. M. (1995). Female headship, feminization of poverty and welfare. Southern Economic Journal, 44–52. doi:10.2307/1061374

- Kongolo, M., & Bamgose, O. O. (2002). Participation of rural women in development: A case study of Tsheseng, Thintwa, and Makhalaneng villages, South Africa. Journal of International Women‘S Studies, 4(1), 79–92.

- Koskei, E. C., Koskei, R. C., Koske, M. C., & Koech, H. K. (2013). Effect of socio-economic factors on access to improved water sources and basic sanitation in Bomet Municipality, Kenya. Research Journal of Environmental and Earth Sciences, 5(12), 714–719.

- Kraan, M. L. (2009). Creating space for fishermen’s livelihoods: Anlo-Ewe beach Seine fishermen’s negotiations for livelihood space within multiple governance structures in Ghana. Leiden University: African Studies Centre.

- Kremer, M., Leino, J., Miguel, E., & Zwane, A. P. (2011). Spring cleaning: Rural water impacts, valuation, and property rights institutions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 145-205.

- Lawrence, P. R., Meigh, J., & Sullivan, C. (2002). The Water Poverty Index: An International Comparison.

- Lowe, B., Lynch, D., & Lowe, J. (2015). Reducing household water consumption: A social marketing approach. Journal of Marketing Management, 31, 378–408. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2014.971044

- Makutsa, P., Nzaku, K., Ogutu, P., Barasa, P., Ombeki, S., Mwaki, A., & Quick, R. E. (2001). Challenges in implementing a point-of-use water quality intervention in rural Kenya. American Journal of Public Health, 91(10), 1571-1573.

- Ministry of Environment Science, Technology and Innovation Ghana. (2013). National Climate Change Policy. Accra: Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation.

- Montgomery, M. A., Bartram, J., & Elimelech, M. (2009). Increasing functional sustainability of water and sanitation supplies in rural sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Engineering Science, 26(5). doi:10.1089/ees.2008.0388

- Müller-Kuckelberg, K. (2012). Climate change and its impact on the livelihood of farmers and agricultural workers in Ghana.

- Neumann, L. E., Moglia, M., Cook, S., Nguyen, M. N., Sharma, A. K., Nguyen, T. H., & Nguyen, B. V. (2014). Water use, sanitation and health in a fragmented urban water system: Case study and household survey. Urban Water Journal, 11(3), 198-210.

- Nzengya, D. M., & Aggarwal, R. (2013). Water accessibility and womens participation along the rural-urban gradient: A study in Lake Victoria Region, Kenya. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning, 6(7), 263–273. doi:10.5897/JGRP2013.0408

- Ogundele, O. J. K., Akingbade, W. A., & Akinlabi, H. B. (2012). Entrepreneurship training and education as strategic tools for poverty alleviation in Nigeria. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 2(1), 148–156.

- Parry, M. L. (2007). Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (Vol. 4). United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Peletz, R. L. (2006). Cross-sectional epidemiological study on water and sanitation practices in the Northern Region of Ghana. USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Ray, I. (2007). Women, water, and development. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 32. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.32.041806.143704

- Smith, S., Anker, M., & Anker, R. (2017) Living Wage Report Ghana Lower Volta Area: Context Provided in the Banana Sector. Ghana: The Global Living Wage Coalition

- Van Houweling, E., Hall, R. P., Diop, A. S., Davis, J., & Seiss, M. (2012). The role of productive water use in women‘s livelihoods: Evidence from rural senegal. Water Alternatives, 5(3), 658-677.

- Vincent, K., Cull, T., Chanika, D., Hamazakaza, P., Joubert, A., Macome, E., & Mutonhodza-Davies, C. (2013). Farmers' responses to climate variability and change in southern Africa–is it coping or adaptation? Climate and Development, 5(3), 194-205.

- Webersik, C. (2010). Climate change and security: A gathering storm of global challenges. Santa Barbara, CA: Abc-Clio.

- Were, E., Swallow, B. M., & Roy, J. (2006). Water, women, and local social organization in the Western Kenya highlands (No. 577-2016-39209).

- WHO, UNICEF. (2016). Improved and unimproved water sources and sanitation facilities. Geneva: WHO/UNIFEC Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) for Water Supply and Sanitation.

- World Health Organization, WHO/UNICEF Joint Water Supply, & Sanitation Monitoring Programme. (2015). Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2015 update and MDG assessment. Geneva: World Health Organization.