?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess teacher perceived skill in classroom assessment practices. Data were collected from a sample of (N = 691) teachers selected from government primary, junior secondary, and senior secondary schools in Botswana. Item response theory models were used to identify teacher response on items that measured their self-perceived skill in classroom assessment practices. Results of the study showed that generally teachers felt more skilled in test construction than other practices such as using classroom assessment results to make informed decisions in their teaching and learning process. Implications of these findings for policy makers and school managers are discussed.

Public Interest Statement

In order to achieve the needed twenty-first century standards of learning, it remains imperative for policy makers to pay attention to teacher competencies particularly their classroom assessment practices. Teachers are held accountable for the quality of student learning process. It is therefore essential for them to attain high levels of competency in assessment practices needed to enhance teaching and learning and attain educational goals. This study assessed teacher perceived skill in classroom assessment practices. Teachers in this study reported to have skill in some assessment practices such as test construction, and less skill in using assessment information to make informed decisions in their teaching and learning process. These results highlight a challenging concern that educators and policy makers must address as a matter of urgency if they want to attain the 21st century educational standards of teaching and learning.

1. Introduction

Teaching is a multifaceted process that requires teacher competencies in measurement and assessment skills. Such skills may include: test planning and construction; grading; interpretation of test results; use of assessment results to inform teaching and learning; interpretation of standardized tests; and communicating results to relevant stakeholders. Teachers are key catalyst of the education process. Their instructional and classroom assessment practices are a means by which the education system is enhanced and defined (Nenty, Adedoyin, Odili, & Major, Citation2007). Teachers adopt a variety of classroom assessment practices to evaluate student learning outcomes, and spend much classroom time engaged in assessment-related activities. Teachers typically control classroom assessment environments by choosing how they assess their students, the frequency of these assessments, and how they provide assessment feedback. For these reasons, it is imperative for them to be competent in classroom assessment practices.

Classroom assessments serve many important purposes, such as grading, identification of students with special learning needs, motivation of students, clarification of student achievement expectations, and monitoring instructional effectiveness (Ohlsen, Citation2007; Stiggins, Citation2001). Indeed, such assessments are an integral part of the teaching and learning process, providing measurement, feedback, reflection, and essential for generating information used for making educational decisions (McMillan, Citation2008; Reynolds, Livingston, & Willson, Citation2009). According to Shepard (Citation2000, p. 5), in order to be useful for teachers, classroom assessments must be transformed in two fundamental ways: “First, the content and character of assessments must be significantly improved, and second, the gathering and use of assessment information and insights must become part of an ongoing learning process.” Classroom assessments are also essential for conveying teacher expectations to students that can stimulate learning (Wiggins, Citation1998). The more information teachers have about their students’ achievements, the clearer the picture about student learning challenges and from where those challenges emanate. For this reason, it is crucial to understand how assessment is used, as failure to do so may lead to an inaccurate understanding of students’ learning, and may ultimately prevent students from reaching their full academic potential (Stiggins, Citation2001).

Botswana, just like other African countries has made tremendous efforts to make educational reforms. Such reforms include the revision of national policy on education. Such revisions lead to the Revised National Policy on Education (Republic of Botswana, Citation1994). This policy encompasses global perspectives to improve national literacy levels. The main aim of this policy is to ensure the development and sustenance of a workforce that possess interpersonal, problem-solving, creative, innovative, and communication skills. The specific aims of Botswana education at school level based on the Revised National Policy on Education RNPE (Republic of Botswana, Citation1994). is to: “(a) Improve management administrative skills to ensure higher learning achievement; (b) improve quality of instruction; (c) implement broader and balanced curricula geared towards developing qualities and skills needed for the world of work; (d) emphasize pre-vocational orientation in preparation for a strengthened post-school technical and vocational education and training; and (e) to improve the response of schools to the needs of different ethnic groups in the society” (p. 4).

The RNPE emphasizes eight key issues that are important for the future development of Botswana’s education: “(1) Access and equity to education for all, (2) Preparation of students for life and world of work, (3) Improvement and maintenance of quality for the education system, (4) Development of training that is responsive to economic development in Botswana, (5) Maintenance of quality education system, (6) Enhancement of the performance and status of the teaching profession (7) Cost sharing between parents and Government, and (8) Effective management of education” (p. 22). The overall objective of Botswana’s education system at national level is to raise the educational standards at all school levels. The specific aim of education at school level is to improve management and administration to ensure higher learning achievement (RNPE, Republic of Botswana, Citation1994). It is clear that Botswana’s education system emphasizes the need for quality in education, for its sustainable development. Probably, one of the emerging issues from the RNPE that is relevant to this study is the enhancement of the performance of teachers.

Botswana proposed a set of strategies to meet its aspirations. One of the pillars of Vision 2016 is to have “An educated and informed nation” by the year 2016. This pillar stipulates that Botswana should have quality education that can adapt to the changing needs of the country as well as keep up with the ongoing world-wide changes. The Long-Term Vision (1997) therefore serves as an inspiration for what Botswana should have achieved after 50 years of independence. It envisages an education system that is based on quality curriculum relevant to enhance good learning environments for everyone. Regardless of these, there are some indications that teachers in Botswana still remain behind in some classroom practices, in particular students’ assessment. Nenty et al. (Citation2007) conducted a study to determine the extent to which primary school teachers in Botswana and Nigeria perceive the six levels of Bloom’s cognitive behavior. They were also to ascertain the level to which their classroom assessment practices make use of items that adequately measure these cognitive behaviors. The study showed some significant discrepancy between how teachers perceived each level of Bloom cognitive behavior and how they enhance quality education and the level to which their classroom assessment practices are able to provide skills needed for the development of cognitive behaviors among learners. This study revealed that most of the teachers still showed lack of basic knowledge and competencies in using recommended assessment techniques.

Many arguments regarding how educators view student assessment practices has been raised. For instance, Ohlsen (Citation2007) stated that “policymakers and the public support the use of high-stakes testing as the measure of student and school achievement despite serious reservations on the part of the educational classroom assessment” (p. 4). Stiggins (Citation2001), on the other hand, is of the opinion that policy-makers, school leaders, and the measurement community have neglected classroom assessments. Stiggins also argues that Teachers tend to adopt assessment methods that were used on them as students, this is as if someone out there has declared it natural for teachers to stay within the old assessment comfort zone rather than learn to adopt and use relevant and quality of assessment methods even before they use them in their classrooms. This neglect and practice for Stiggins, has led to low assessment literacy for teachers and resulted in inaccurate assessment of achievement and ineffective feedback for students.

Teachers play an integral role in student assessment, for this reason, their competencies and knowledge skills in classroom assessment practices remain critical. Tigelaar, Dolmans, Wolfhagen, and van der Vleuten (Citation2004) describe teacher competencies as a cohesive set of teacher characteristics, knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed for effective performance in various teaching contexts. Zhang and Burry-Stock (Citation2003) argued that teachers’ perceived skill in classroom assessment practices reflects their perceptions on their skill in conducting classroom assessment practices. Zhang and Burry-Stock explain why teachers may rate their assessment skills as good even if they are found to be incompetent to conduct some assessment practices. When asked about assessment training they received and if such training benefited their classroom practices, teachers generally indicate that assessment training they receive did not adequately prepare them for their classroom assessment practices (Koloi-Keaikitse, Citation2012; Mertler, Citation2009). As educators we are all aware of implications of limited teacher assessment training on teaching and learning. Insufficient teacher training may impact on skill-based assessment needed for sustainable development. It is therefore essential to develop teachers’ assessment competencies and skills to improve their classroom assessment practices to cope with the ever changing twenty-first-century educational needs. Chester & Chester and Quilter (1998) as cited in Susuwele-Banda (Citation2005) argued that it is important to study teacher perceptions of assessment as this can inform educators how different forms of assessments are used or misused and what can be done to improve teacher classroom assessment practices. Darling-Hammond et al. (200) as cited in Koloi-Keaikitse (Citation2016) supports the need for teacher competencies in assessment because if teachers feel prepared when they enter teaching they are most likely to have better sense of teaching efficacy which can ultimately improve their motivation to teach. This study was therefore meant to assess teachers’ response pattern on a self-perceived skills in classroom assessment practices. Teachers’ assessment practices are an essential element for addressing students’ learning needs, and they can ultimately improve the education system and accountability. Understanding teachers’ assessment practices serve as a way of finding out if teachers adopt or use quality assessment methods that can address the learning needs of students (McMillan, Citation2001).

1.1. A brief description of item response theory models

This study is meant to assess teacher’s response pattern in a set of items that measured their perceived skill in classroom assessment practices. In order to gain insights into teacher’s response to their perceived skill in assessment scale, an item response theory (IRT) model was utilized. IRT refers to a set of models that connects observed item responses to a participant examinee’s location on the underlying (latent) trait that is measured by the entire scale (Mellenbergh, Citation1994). IRT models have been found to have a number of advantages over classical test theory (CTT) methods in assessing self-reported outcomes such as teacher beliefs, perceptions, and attitudes (Hambleton, Swaminathan, & Rogers, Citation1991). The major limitation of CTT, however, is that an individual ability (theta) and item level of difficulty cannot be estimated separately. IRT, on the other hand, is a general statistical theory about examinee item and test and how performance relates to the abilities that are measured by the items in the test. IRT models have the potential to highlight whether items are equivalent in meaning to different respondents, they can be used to assess items with different response patterns within the same scale of measurement, therefore can detect different item response patterns in a given scale. IRT models yield item and latent trait estimates (within a linear transformation) that do not vary with the characteristics of the population with respect to the underlying trait, standard errors conditional on trait level, and trait estimates linked to item content (Hays, Morales, & Reise, Citation2000). IRT provides several improvements in scaling items and people. The specifics depend upon the IRT model, but most models scale the difficulty of items and the ability of people on the same metric. Thus, the difficulty of an item and the ability of a person can be meaningfully compared. Parameters of IRT models are generally not sample- or test-dependent, whereas true-score is defined in CTT in the context of a specific test. Thus, IRT provides significantly greater flexibility in situations where different samples or test forms are used. Thus, IRT is regarded as an improved version of CTT as many different tasks may be performed through IRT models that provide more flexible information. General characteristics of IRT model are that: item statistics and the test taker are not dependent of each other; an estimation of amount of error in each measured trait or standard error of measurement (SEM) is available in IRT process. Test items and traits of the test taker are referenced on the same interval scale (Hambleton et al., Citation1991).

There are a variety of IRT models that differ in terms of the type of item response pattern and the amount of item information they will accommodate. All of these models estimate the probability of a particular item response based on the amount of the latent construct. With respect to the items, estimates of location (relative likelihood that an individual will agree with the item) and discrimination (the ability of the item to distinguish between individuals with different levels of the latent trait are provided in the IRT framework. For the purpose of this study, two IRT models, the partial credit model (PCM) and graded response model (GRM) were assessed for relative use. For items with two or more ordered responses such as items in the teacher perceived skills in classroom assessment practices in this current study, Masters (Citation1982) created the PCM that contains two sets of location parameters, one for persons and one for items, on an underlying unidimensional construct (Masters & Wright, Citation1997). The PCM is therefore the simplest and commonly used for ordered response items where a single item discrimination value is estimated for the entire items. This model can be applied in situations where response on an item is measured in dichotomous or polytomous categories. That is,

If used with more than two response patterns, (Likert Scale) a score of 1 is not expected to be increasingly likely with increasing ability because, beyond some point, a score of 1 should become less likely as a score of 2 become more probable result. It follows an order of 0 < 1 < 2 … j < m i of a set of categories that the conditional probability of scoring x rather x−1 increases monotonically throughout ability range (Masters & Wright, Citation1997, p. 102).

The other IRT model commonly used for ordered response items is GRM. As stated in Samejima (Citation2010), graded response is a general theoretical framework proposed by Samejima (Citation1969) to deal with graded item scores 0, 1, 2, m g in the IRT. In a GRM, a response may be graded on a range of scores, as an example, from poor (0) to excellent (9). For survey measurement, a subject may choose one option out of a number of graded options, such as a five-point Likert-type scale: “strongly-disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree” (Mellenbergh, Citation1994). An item in a GRM is described by a slope parameter and between category threshold parameters (one less than the number of response categories). For the GRM, one operating characteristic curve needs to be estimated for each between category thresholds. Each item in a GRM model is described as a slope parameter and between category threshold parameters.

1.2. Purpose of the study

Using IRT, the study identified items that provide the most information about teachers’ perceived skills in classroom assessment practices. In turn, by identifying which skills teachers are most and least confident about, it is hoped to provide educational administrators, policy-makers, and teacher educators with useful information for the planning and conducting of assessment training for teachers. The main research question is; which classroom assessment practices do teachers perceive themselves more skilled?

2. Method

2.1. Study population and sampling

Teachers were selected from nine educational inspectoral areas in Botswana. The teachers who teach in these schools have different levels of teacher training. Some teachers hold certificate in primary education is the lowest post-secondary training that was meant to give teachers basic skills they need for classroom teaching. This lowest level of teacher training has been replaced by an advanced diploma that has been adopted to enable increased production of teachers trained at a higher level. In this study, some primary school teachers had a certificate in primary education (n = 55); some hold a diploma in primary education (n = 170); and others hold a degree in primary education (n = 40). Those who teach at junior secondary school level, some had a diploma in secondary education (n = 162); some a degree in secondary education (n = 79); and only a few had Master’s degree in education (n = 2). Those who teach at the senior secondary school level had degrees in Humanities, Science, and Social Sciences as well as post graduate diploma in secondary education (n = 175); and a Master’s degree in Education (n = 8). Primary school teachers in Botswana teach one standard (grade) in a given year, and they teach all the subjects. Those who teach in junior secondary and senior secondary schools teach specialized subjects, that they offer to different classes. To ensure that teachers who participated in the study represented all the relevant subgroups stratified random sampling selection method was used to ensure the sample of teachers based on their training, grade level, subjects taught, years of experience, and school level were selected. Teachers were followed in the staffrooms where they work and were invited to participate. A total of (N = 691) teachers agreed to participate. Out of these (n = 265), were primary school teachers. Junior secondary school teachers were (n = 243), while senior secondary school teachers were (n = 183).

2.2. Instrument

The Classroom Assessment Practices and Skills Questionnaire was used as the data collection instrument to assess teachers’ perceived skills in classroom assessment practices. Some of items were adapted from Assessment Practices Inventory (API, Zhang & Burry-Stock, Citation2003). This instrument was created and used in the United States of America to measure teachers’ perceived skills about classroom assessment practices across teaching levels, content areas, and teachers self-perceived assessment skills as a function of teaching experience. The Zhang & Burry-Stock skill scale consists of 67 items measured on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (not at all skilled) to 5 (very skilled). Items were scored so that higher numbers indicated higher perceived skill in classroom assessment practices. In order to ensure that items were content and context relevant for teachers in Botswana based on the language and curriculum, appropriate revisions were made. Based on this revision process, 37 items were found to be irrelevant for Botswana teachers in terms of wording and content hence not used. Of the original remaining items, 21 were without modification and 8 items were modified by changing some of the words to make them context and content relevant to the population of teachers in Botswana. These revised items were used to generate a final set of 29 items and used to measure teachers perceived skills in classroom assessment practices in Botswana.

To check the content-validity of the instrument, the draft questionnaire was given content experts in classroom assessment and teacher training. They were asked to review the items for clarity and completeness in covering most, if not all, assessment and grading practices used by teachers in classroom settings, as well as to establish face and content validity of the instrument and items. Necessary revisions were made based upon their analyses. The draft questionnaire with 29 items was pilot tested with a total sample of 88 teachers from primary school (n = 29), junior secondary school (n = 30), and senior secondary school (n = 29) to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the questionnaire in terms of question format, wording and order of items. It was also meant to help in the identification of question variation, meaning, item difficulty, and participants’ interest and attention in responding to individual items, as well as to establish relationships among items and item responses, and to check item response reliability (Gay, Mills, & Airasian, Citation2009; Mertens, Citation2014). Reliability estimates of teachers’ perceived skill in classroom assessment were estimated using Cronbach’s Alpha, which was α = .95 indicating high levels of internal consistency.

2.3. Data analysis

Prior to conducting the focal analysis to answer research questions regarding teachers response on the self-perceived skill in classroom assessment practices scale, descriptive statistics including means and standard deviations were used to assess for data entry errors. To identify the underlying dimension in the self-perceived in classroom assessment scale, principal axis factoring as a method of factor extraction with Promax with Kaiser normalization rotation methods were used.

The main focus of this study was to assess teachers’ response pattern on a self-perceived skills in classroom assessment practices. Some items in the scale used to measure teacher self-perceived skills in classroom assessment practices were adapted from a set of items that have been used with teachers in the United States. Several steps were followed in modeling the perceived skill in classroom assessment subscale. Chi-square (

χ

2) goodness of fit test for the data with each given model PCM and GRM was calculated to determine how well each model predicted actual item responses. Larger

χ

2 values showed poor fit. Model fit for the PCM and GRM was assessed through Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) of each model. The model with smaller AIC and BIC values was considered a better fitting model than model with larger values. In addition to assessing overall model fit, the relative fit for the PCM and GRM models were compared to determine the model that works well. Relative fit for the two models was compared using relative efficiency (RE) of the two models. RE measured the relative amount of information about each model. In order to calculate the RE of two models, the total test information for each model was calculated. RE reflects how much more (or less) information about teachers perceived skill in classroom assessment practices could be obtained from a more complex model (GRM) as compared to a simpler one (PCM).

The optimal IRT model was selected and used to estimate item parameter values. Individual item information values were assessed to identify items that are optimal for assessing teachers’ perceived skills in classroom assessment practices. Lastly, item characteristic curves (ICC) and item information curves (IIC) for the best and worst discriminating items were calculated and assessed to provide detailed information of item response on these items. Data analysis was conducted using the R (version 12.2) software package (R Development Team, 2012).

The items in a polytomous scale are a series of cumulative comparisons (Samejima, Citation1969) and are based on the following model equation.

where X j = Item response; K = Threshold for selected item response; θ = Given ability (theta); a j = Item discrimination; δ Xj = Difficulty parameter for an item.

Items in this study items were rated on a 1–5 scale (not skilled to very skilled) and had four response dichotomies: (a) Category 1 versus Categories 2, 3, 4, and 5; (b) Categories 1 and 2 versus Categories 3, 4, and 5; (c) Categories 1, 2, and 3 versus Categories 4 and 5; (d) Categories 1, 2, 3, and 4 versus Category 5. The GRM considers the probability of endorsing each response option category, (xj) or higher as a function of a latent trait (P~j (01). In this study, the items asked teachers to indicate their perceived skill in classroom assessment practices using a five-point response scale that ranged from “1: not skilled” to “5: very skilled,” with a neutral category at 3 (somewhat skilled). The assumption was that the more perceived skill in classroom assessment practice teachers were, the higher the response on the alternative chosen. The probability of endorsing a 1 (not skilled) was expected to increase monotonically the less perceived skill in classroom assessment practice an individual teacher was. The probability of endorsing a 5 (very skilled) was expected to increase monotonically when an individual teacher had higher perceived skill in a classroom assessment practice being measured by an individual item. To give a response of 2 (little skilled) was a function of being above some threshold between 1 (not skilled) and 2 (little skilled) and below some threshold between 2 (little skilled) and 3 (somewhat skilled).

3. Results

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to reduce a large number of items to generate factors that can be analyzed and interpreted with ease, as well as to determine the underlying factor structure of the items in the questionnaire (Field, Citation2005; Thompson, Citation2005). Data were factor-analyzed with principal axis factoring to provide more information that is easy to interpret for each section (Cureton & D’Agostino, Citation1983). Promax oblique factor rotation method commonly used when factors are correlated (Field, Citation2005; Thompson, Citation2005), was used on the “skill” of assessment practices subscales. Based on Kaiser’ theory of (eigenvalues > 1) criterion, the 29 items from Skill in assessment subscale converged into six factors that accounted for 53% of variance in item responses after extraction. Factor loading values greater than .40 showed that an item loaded on a particular factor (see Table ). Cronbach’s Alpha estimates of the self-perceived skills appear in (Table ) show that construction of essay items had the lowest reliability estimate.

Table 1. Factor loadings for exploratory factor analysis with promax oblique rotation of self-perceived skill in classroom assessment practices

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha estimates for the self-perceived skill factors

Model fit between PCM and GRM was assessed. The null hypothesis that model fit was the same for the PCM and the GRM was tested, and rejected. Model fit for the models was also compared using AIC and the BIC. The AIC and BIC values were smaller for the GRM, indicating that GRM was a better fitting model for the data than the PCM (see Table ). Finally, model information for the PCM and GRM were compared to determine which provides the most information about the measured latent trait, perceived assessment skills. Results showed that the PCM provides 84.5% as much information as the GRM (see Table ).

Table 3. Model fit indexes for partial credit model and graded response model

Table 4. Model information partial credit model and graded response model

Based on the model fit and model information results, the GRM was selected to estimate item parameters for teachers’ perceived skill in classroom assessment practices scale. The GRM is potentially a useful item response model when items are conceptualized as ordered categories (e.g. with a Likert-type rating scale). The results showed that the 29 items in the perceived skill in classroom assessment subscale varied in their discrimination and location values. The range in discrimination estimates was between 1.007 and 2.050 (see Table ). The items that best differentiated teachers with regard to their perceived skill in classroom assessment were primarily those that asked about their perceived skills in using and communicating assessment results. Specifically, Item13 (Using assessment results when planning teaching), Item 14 (Communicating classroom assessment results to others), Item 7 (Revise Items based on Item Analysis), and Item 11(Using assessment results for decision--making) had the highest discrimination values. Similarly, these items also provided more information in estimating the latent trait of teachers’ perceived skill with assessments compared with other items. An indication that compared to others or based on type of training they received, some teachers felt more skilled in using assessment results when planning their teaching, felt more competent in communicating assessment results to other stakeholders, may have received adequate training in item analysis, and felt that they have the needed competency to use assessment results to inform educational decisions (see Table ).

Table 5. Item threshold, discrimination values, and information for teachers perceived skills in classroom assessment items

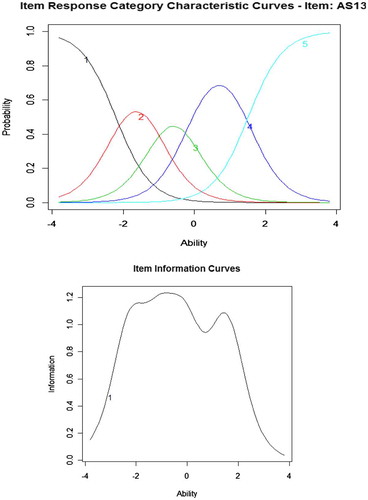

For illustration purposes, Item 13 was used to highlight items that were the highest in discriminating teachers with regard to their perceived skills in classroom assessment practices. Item 13 asked teachers about their perceived skills in using assessment results for planning their teaching. A clear indication that the item was better in measuring teacher competency skills in using assessment results for planning their teaching. The item characteristics curves (ICC) for item 13 showed that teachers with skills greater than or approximately 1.8 felt very skilled in using assessment information, those with skill at 1.7 felt skilled in using assessment information, those who felt somehow skilled were at −1.8 response level, those at −3.9 felt to have little skill and those at −2.0 had no skill in using assessment information. Similarly, the IIC showed that Item 13 provided more information about teachers with less perceived skill in using assessment information when planning their teaching. Perhaps this indicates that some teachers may have received adequate training in using assessment information than other teachers (see Figure ).

Items that did not discriminate teachers with high perceived classroom assessment skills from those with low perceived classroom skills were those that asked teachers about their perceived skills in test construction and calculation of central tendency. These items included Items 1 (Constructing Multiple Choice Items), Item 2 (Constructing Essay Items), Item 27 (Construct True or False Items), and Item 5 (Calculating Central Tendency for Teacher Made Tests). Similarly, these items provided relatively little information for estimating teachers’ perceived assessment skills. These had relatively low threshold values, indicating that based on the kind of training they received and most probably due to their teaching experience most teachers perceived themselves well skilled in constructing multiple choice items, essay items and true or false items, as well as calculating averages for teacher made tests.

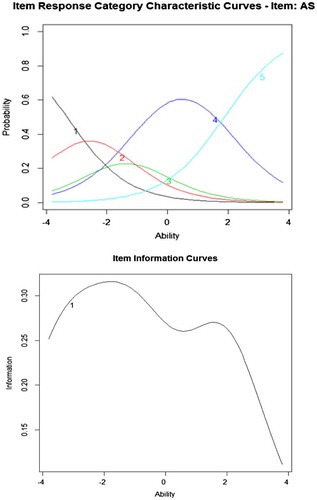

For illustration purposes, Item 1 was used to highlight items that were the lowest in discriminating teachers with regard to their perceived skills in classroom assessment practices. Item 1 asked teachers to indicate their perceived skill in constructing multiple choice items. Results showed this item did not discriminate teachers with the skill from those without skill in constructing multiple choice items. The ICC for item 1 showed that teachers with an ability greater than approximately 1.9 were most likely reported to be very skilled in constructing multiple choice items, and those with ability approximately 1.8 are most likely to report that they are very skilled in multiple choice item construction, while those with an ability less than approximately .5 were most likely to indicate that they were somehow skilled in constructing multiple items. Those who felt they had little skill were at −2.3 response level and those without skill were at −1.9. Similarly, the IIC showed that Item 1 provided more information about teachers for teachers with high perceived skills in constructing multiple choice items. This showed that most of the teachers felt more skilled in constructing multiple choice items. Therefore, Item 1 was not a good item for discriminating teachers with high self-perceived skill in constructing multiple choice items (see Figure ).

4. Discussion and conclusion

IRT was used to evaluate item response patterns on a teacher perceived skill in classroom assessment for Botswana primary and secondary school teachers. Given the value for classroom assessment practices and the need to have a clear understanding of teachers perceived skills in classroom assessment practices (Cavanagh, Waldrip, Romanoski, Dorman, & Fisher, Citation2005; Marriot & Lau, Citation2008; Nenty et al., Citation2007; Rowntree, Citation1987; Zhang & Burry-Stock, Citation2003) and the relative scarcity in this area of research in an African context, the study adds to the understanding of teachers perceived skills in classroom assessment practices.

Teachers continue to be important for bringing change and preparing students for future endeavors. It is therefore imperative to understand their teaching practices particularly how they assess and evaluate student learning outcomes (McMillan, Citation2008; Reynolds et al., Citation2009). Gathering information that can highlight the level of teachers’ classroom assessment competences in conducting classroom assessments is vital to determine their capabilities and inadequacies. Such information can be used by institutions that conduct teachers’ education and professional development to develop teachers’ assessment competencies.

This study should be helpful in identifying classroom assessment skills that teachers perceive to possess as well as those for which they feel less competent. As noted previously, the Teachers Perceived Skills in Classroom Assessment scale was previously used with teachers in the United States. However, the construct has not been widely studied among African teachers. It is essential for researchers, educators, and policy-makers in the African context to have a clear understanding of the perceived skills teachers hold about certain classroom assessment practices. Understanding teachers’ perceptions about their perceived skills in classroom assessment practices is very important as it can open avenues informing policy and practice for addressing the needs that teachers have as they wrestle with their day-to-day classroom assessment practices.

Overall results of this study revealed that items that assessed teachers’ perceived skills in the use and communication of assessment results provided the most information for identifying which teachers feel most (and least) confident about classroom assessment practices. Additionally, the results showed that items asking teachers about their perceived skills in test construction and calculation of statistical techniques such as measures of central tendency were the least useful in understanding overall perceptions about assessment skills. These items were relatively “easy,” so that most teachers felt pretty comfortable doing them. Further examination of the results showed that an item that asked teachers about their perceived skill in portfolio assessment proved to be the most difficult for respondents to endorse, an indication that most of the teachers were less skilled in portfolio assessment. Further research to establish why teachers felt least competent in portfolio assessment is highly recommended. This is based on the debates of using traditional forms of assessment such as multiple choice items against alternative assessments such as portfolio assessments. Those who argue for using traditional assessments argue that just like other forms of assessments, traditional tests are also focused on improving the cognitive side of instruction, i.e. the skills and knowledge that students are expected to develop within a short period of time (Segers & Dochy, Citation2001). A study conducted by Kleinert, Kennedy, and Kearns (Citation1999) revealed that teachers expressed levels of frustration in the use of alternative assessments such as portfolio assessment. Some major issues that teachers have against the use of alternative assessments are that they require more time for students to complete, and for teachers to supervise and assess. Teachers are generally also concerned about competencies they have in reliably grading these forms of assessments and that such assessments are more teacher-based than student-based.

These findings have major implications for teacher educators and school managers. For teacher educators these results highlight classroom assessment areas that they may need to focus on as they teach assessment courses. Assessment entails a broad spectrum of activities that includes collection of information for decision-making. The responsibility of teachers is to collect information through various assessment methods that can be used to make informed decisions about students’ learning progress. The question is: are teachers competent enough to use or apply assessment information for making students’ learning decisions? From these results it was very clear that teachers are less confident in using assessment information to make informed instructional and learning decisions.

Teachers depend on the classroom assessment information to improve their instructional methods, and as such, that information plays an important role in student learning. It is apparent that teachers should be made competent in the collection, analysis and use of assessment information. Zhang and Burry-Stock (Citation2003) argued that to be able to communicate assessment results more effectively, teachers must possess a clear understanding about the limitations and strengths of various assessment methods. Teachers must also use proper terminology as they use assessment results to inform other people about the decisions about student learning. For this reason, teacher educators must find ways in which they can improve their assessment training methods that can equip teachers with needed skills for using and communicating assessment results. This finding equally brings major challenges to school administrators who rely on teachers to provide them with information about student learning that they collect from assessment results. If teachers show to be less competent in using and communicating assessment results then how do they inform their mangers about student learning progress?

It is clear that items that assessed teachers’ perceived skills about test construction were not helpful in providing essential information about teachers’ perceived skills in classroom assessment practices. This finding is important because it shows that if school managers want to know assessment areas that teachers may need to be trained on, they may not ask them about their perceived skills in test construction, but rather they may want to establish if teachers are more confident in using assessment information for improving their instructional methods, or whether they are in a position to communicate assessment results for better decision-making about student learning. These results generally imply the need for teacher educators or assessment professional development specialists to focus their attention on assessment training on skills teachers need most and those they have less perceived skills on.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Setlhomo Koloi-Keaikitse

Setlhomo Koloi-Keaikitse is a senior lecture at the University of Botswana with a PhD in Educational Psychology that she obtained from Ball State University (USA). She currently teaches Research Methods and Evaluation courses to both graduate and undergraduate students. She has diverse research interests including scale validation, classroom assessment, program evaluation, indigenous research methodologies, and ethics in human subject research. She is currently working on different research areas such as validation of test anxiety instruments for use in African tertiary institutions, teacher classroom assessment practices, and examination item quality.

References

- Cavanagh, R. , Waldrip, B. , Romanoski, J. , Dorman, J. , & Fisher, D. (2005). Measuring student perceptions of classroom assessment . In annual meeting of the Australian Association for Research in Education, Parramatta.

- Cureton, E. E. , & D’Agostino, R. B. (1983). Factor analysis: An applied approach . Psychology Press.

- Field, A. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS . Riverside, CA: Sage.

- Gay, L. R. , Mills, G. E. , & Airasian, P. (2009). Educational research competencies for analysis and applications . Columbus, GA: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Hambleton, R. K. , Swaminathan, H. , & Rogers, H. J. (1991). Fundamentals of item response theory: Measurement methods for the social sciences series (Vol. 2). New York, NY: Sage.

- Hays, R. D. , Morales, L. S. , & Reise, S. P. (2000). Item response theory and health outcomes measurement in the 21st century. Medical Care , 38 , II28–II42.

- Kleinert, H. L. , Kennedy, S. , & Kearns, J. F. (1999). The impact of alternate assessments: A statewide teacher survey. The Journal of Special Education , 33 , 93–102.10.1177/002246699903300203

- Koloi-Keaikitse, S. (2012). Classroom assessment practices: A survey of Botswana primary and secondary school teachers (Doctoral dissertation). Muncie, IN: Ball State University.

- Koloi-Keaikitse, S. (2016). Assessment training: A precondition for teachers’ competencies and use of classroom assessment practices. International Journal of Training and Development , 20 , 107–123.10.1111/ijtd.2016.20.issue-2

- Marriot, P. , & Lau, A. (2008). The use of on-line summative assessment in undergraduate financial accounting course. Journal of Accounting Education , 26 , 773–790.

- Masters, G. N. (1982). A rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika , 47 , 149–174.

- Masters, G. N. , & Wright, B. D. (1997). The partial credit model. In W. van der Linden & R. Hambleton (Eds.), Handbook of modern item response theory (pp. 101–121). New York, NY: Springer.

- McMillan, J. M. (2001). Secondary teachers’ classroom assessment and grading practices. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practices , 20 , 20–32.

- McMillan, J. M. (2008). Assessment essentials for student-based education (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Crown Press.

- Mellenbergh, G. J. (1994). Generalized linear item response theory. Psychological Bulletin , 115 , 300–307. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.300

- Mertens, D. M. (2014). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods . New York, NY: Sage.

- Mertler, C. A. (2009). Teachers’ assessment knowledge and their perceptions of the impact of classroom assessment professional development. Improving Schools , 12 , 101–113.10.1177/1365480209105575

- Nenty, H. J. , Adedoyin, O. O. , Odili, J. N. , & Major, T. E. (2007). Primary teachers’ perceptions of classroom assessment practices as means of providing quality primary and basic education by Botswana and Nigeria. Educational Research and Review , 2 , 74–81.

- Ohlsen, M. T. (2007). Classroom assessment practices of secondary school members of NCTM. American Secondary Education , 36 , 4–14.

- Republic of Botswana . (1994). Revised national policy in education . Gaborone: Botswana Government Printer.

- Reynolds, C. R. , Livingston, R. B. , & Willson, V. (2009). Measurement and assessment in education (2nd ed.). Toronto, OH: Pearson.

- Rowntree, D. (1987). Assessing students: How shall we know them? . New Jersey, NJ: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data.

- Samejima, F. (1969). Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monograph Supplement , 34 , 2.

- Samejima, F. (2010). The general graded response model. Handbook of polytomous item response theory models (pp. 43–76). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Segers, M. , & Dochy, F. (2001). New assessment forms in problem-based learning: The value-added of the students' perspective. Studies in Higher Education , 26 , 327–343.10.1080/03075070120076291

- Shepard, L. A. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educational Researcher , 29 , 4–14.

- Stiggins, R. J. (2001). Student-involved classroom assessment (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Susuwele-Banda, W. J. (2005). Classroom assessment in Malawi: Teachers perceptions and practices in mathematics (Doctoral dissertation). Virginia Tech.

- Thompson, B. (2005). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Understanding concepts and applications . Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Tigelaar, D. E. , Dolmans, D. H. , Wolfhagen, I. H. , & van der Vleuten, C. P. (2004). The development and validation of a framework for teaching competencies in higher education. Higher Education , 48 , 253–268.10.1023/B:HIGH.0000034318.74275.e4

- Wiggins, G. P. (1998). Educative assessment: Designing assessments to inform and improve student performance . San Francisco, CS: Jossey-Bass.

- Zhang, Z. R. , & Burry-Stock, J. A. (2003). Classroom assessment practices and teachers' self-perceived assessment skills. Applied Measurement in Education , 16 , 323–342.10.1207/S15324818AME1604_4