?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examined whether a three-month equine-assisted learning program improved measures of character skills in two independent cohorts of Year 1 youths, in a specialized secondary school for youths with difficulties coping with mainstream curriculum. In 2013, 75 students underwent intervention while 82 students did not. In 2014, 58 students underwent intervention and 59 students were waitlisted in semester 1; cross-over was performed in semester 2. The students were rated a week before, mid-way and a week post-intervention. Results from multi-level modeling indicated that the intervention led to progressive improvements in character skills over the school semester, in the majority of the constructs measured in both the 2013 and 2014 cohorts. The rate of change in measures of character skills over the semester correlated with the grade point average of the students at semester-end. Implications and limitations of the findings are discussed.

Public Interest Statement

In Singapore, youths who have difficulties with the mainstream curriculum are enrolled in pre-vocational schools. One such pre-vocational school, besides cognitive and technical skills, focuses on nurturing of character-building skill sets considered to be critical for community functioning and sustainment of future employment. The present study found that a semester-long structured horse therapy program improves the character skills of Year 1 students, compared to those not enrolled in the program. The positive findings extend to a different cohort of Year 1 students in semester 1 of the following year, as well as a separate student cohort in semester 2. The improvements in character skills related to horse therapy over the semester are associated with higher academic grades at the semester-end. While the results are encouraging, longer-term studies in future and larger cohorts of students at-risk for school or social failure are required to support our findings.

1. Introduction

The Singapore education system mandates six years of Primary school education for all children, to be attended from the ages of 7–12. At the end of the six years, students sit for a national examination that will determine their qualification for Secondary school (Goh & Gopinathan, Citation2008). Each year, 2.2–2.9% of Primary school students (approximately 1,200 children per year) fail this national exit examination (Mourshed, Chijioke, & Barber, Citation2010). Some of these students remain in Primary School and retake the examination one year later. Students who do not complete Primary School or who fail their PSLE may enroll in specialized pre-vocational Schools (Goh & Gopinathan, Citation2008). Currently, there are two pre-vocational schools in Singapore that provide four years of schooling for youths aged 13–16 years (Ministry of Education, Citation2012). English and Mathematics, as well as socio-emotional skills and vocational skills are being taught in these pre-vocational schools.

The students in this study come from one of the two pre-vocational schools. Students from this pre-vocational school were largely from underprivileged backgrounds; about half of them were from families with monthly incomes of less than $1,500 (average monthly median incomes in Singapore in the same year were $6,342) (Department of Statistics Singapore, Citation2015; Leong, Citation2009). More than half of their parents had not received secondary school education (Leong, Citation2009). In a society of widening income gap, many had both parents who worked to make ends meet, with little time for them (Leong, Citation2009). Many of the others were brought up by a step-parent, single parent, or grandparents (Leong, Citation2009).

The curriculum of this pre-vocational school differed from mainstream schools. Not only were the students taught ‘hard’ cognitive skills, focus was on nurturing of “soft” skills. The pioneer teachers and psychologists of the school wanted additional measures of “soft” character skills—beyond the typical academic assessments carried out in mainstream schools—that were important for the students’ success in school, and beyond school. The upshot of the many rounds of discussion among the teachers and school board members was the implementation of the “Habits of Mind”, as measures of character development. Habits of Mind is a concept introduced by Costa and Kallick on developing certain disposition or characteristics that would be useful when faced with challenging situations (Costa & Kallick, Citation2008). The school teachers and psychologists identified five independent Habits of Mind, namely Persistence, Thinking Flexibly, Taking Responsible Risks, Managing Impulsivity and Listening with Understanding and Empathy. The teachers had taken into consideration the challenging circumstances that many of these at-risk students grew up in, with the belief that the cultivation of these five character skills in their students would help develop competencies for lifelong learning, and sustain their future employment.

The “Equine-Assisted Learning” (EQUAL) program was subsequently co-developed by the Singapore Equestrian Federation and the school, with the aims of cultivating the five selected Habits of Mind. This program is a combination of mutually inclusive interventions of therapeutic riding, hippotherapy, and equine-assisted psychotherapy. Therapeutic riding involves learning how to ride and horsemanship, and has been suggested to contribute to positive behavioral and socio-emotional outcomes in at-risk children (Kaiser, Smith, Heleski, & Spence, Citation2006). Besides being responsible for ensuring the safety of the students, the employees and volunteers involved in EQUAL provide instructions on the interaction with the horses, including grooming, mounting, trotting and lunging. Hippotherapy refers to the use of equine movement to engage the sensory, neuromotor and cognitive systems to achieve functional outcomes, as part of an integrated program (American Hippotherapy Association, Citation2016). The improvements in sensory and muscular systems as a result of the equine movement have been postulated to confer psychological and social benefits and the student’s ability to learn (Granados & Agís, Citation2011). Equine-assisted psychotherapy is carried out by psychologists employed by the equestrian federation, with the goal of harnessing the horse–human interactions to achieve therapeutic or educational outcomes (Fine, Citation2006). Through a series of structured activities, the psychologists would work with the students in a group setting to relate what has been learnt and applied through the horse–human interactions, such as Persistence and Taking Responsible Risks (in learning how to ride and dealing with the horses) to everyday academic and life situations. Overall, the EQUAL program was designed with the goal of incorporating non-verbal experiential horse-related experiential learning to the behavioral outcomes targeted by school.

Although used for years in the treatment of physical and psychiatric ailments, empirical evidence from well-conducted studies of equine-related therapy, or even animal-assisted therapy on the whole, remain scarce and inconclusive (Anestis, Anestis, Zawilinski, Hopkins, & Lilienfeld, Citation2014; Kamioka et al., Citation2014; Selby & Smith-Osborne, Citation2013; Whalen & Case-Smith, Citation2012). Till date, findings from studies of equine-related therapy on youths at-risk for school or social failure are limited by their small sample sizes (Bachi, Terkel, & Teichman, Citation2012; Kaiser et al., Citation2006). In the one larger scale study of at-risk youths (Trotter, Chandler, Goodwin-Bond, & Casey, Citation2008), the interpretation of the finding is clouded by selection bias (students could choose their form of therapy between equine-related intervention and classroom counseling), high unreported drop-out rates and lack of multiple comparison testing (Anestis et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, the costs of this complementary approach to character-building are substantial, as it involves the use of equestrian facilities and several staff to carry out the EQUAL intervention. Also, the logistics of such an intervention are more complicated than classroom-based interventions—students have to be transported to a ranch setting for the equine-related intervention to be carried out. Hence, there is a need to carry out longitudinal studies with adequate sample sizes to examine whether a structured equine-related intervention can lead to significantly positive improvements in character skills in a “real-world” school setting, so as to inform future educational policies and provide a framework for cost-effectiveness studies.

Hence in this study, we sought to determine the effectiveness of a structured horse-related intervention in a specialized school for youths at-risk for academic or life failure. The EQUAL intervention was incorporated in the school curriculum in the second semester of 2013 and also carried out over two semesters in 2014, with a three-month washout period (including semester break) in between. To address our question, we first examined whether there is an improvement in the targeted Habits of Minds measures over the semester. We then examined the relationship between the rate of change in Habits of Minds scores over the semester with the grade point average of the students at each semester-end.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

A pioneer batch of Year 1 students received EQUAL intervention in 2013 semester 2. Out of the entire cohort of 157 students l, 75 students from 4 randomly chosen classes (45 males and 30 females) attended EQUAL and the remaining 82 students from the other 4 classes (58 males and 27 females) formed the non-intervention group. (Under the Singapore school system, students within the same class follow similar lesson schedules. They attend the same lessons at the same time as a class.) In 2014, a new cohort of 58 students from four-randomly chosen classes (38 males and 20 females) received EQUAL in semester 1, and 59 subjects from the remaining four-classes (38 males and 21 females) received EQUAL in semester 2. A three-month interval, which included a one-month school semester break in between the two semesters, served as the “washout” period.

All the students in the Year 2013 and Year 2014 were born in the years 2000 and 2001, respectively. As Singapore is a multi-racial society, and in view of Article 12 of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore “ Equal Protection: the guarantee of equality before law, regardless of religion, race, descent and place of birth”, the school has specifically requested that information on ethnicity be withheld from publications for racial sensitivity purposes. Nevertheless, the students are assigned into classes that had a racial quota, in adherence to the ethnic integration policy implemented by the Singapore Government (Sim, Citation2015). The school has also requested for confidentiality of existing medical conditions of the students. That said, none of the students have any severe physical or mental disability.

This study was approved by the SingHealth Institution Review Board after evaluating the study protocol for exemption, and waiver of consent for need to obtain written informed consent from parents/guardians of the children to participate in this study and for their data to be used for research purposes.

2.2. Intervention

The EQUAL program was sponsored by Temasek Cares, Tote Board, Lee Foundation, Far East Organization, Singapore Business Foundation, Keppel Ltd, and generous donors from the community. EQUAL was chaired by Dr Melanie Chew, Ms Harpreet Bedi, Dr Jade Kua, Ms Melissa Tan and Professor Lim Soo Ping, who worked with the teachers of the pre-vocational School to design and align the EQUAL program to the school’s focus on Habits of Mind. The program comprises 48 h of horse-related activities, delivered in 16 weekly sessions at three hours per session. During these sessions, a class grouping of 20–40 students takes part in three separate activities. Each activity is designed to illustrate, train and reinforce a Habit of Mind. As an example of a 3 h session, the students are first gathered in an assembly during which they are briefed on the schedule for the day. Then they are split into three groups. Each group will participate in all three activities, with the three groups rotating among the three activities. The activities vary but they generally form three streams: Horse Play (students engage in individual or group goal-directed exercises with loose horses in an open arena), Stable Management (students interact with horses in an enclosed stable environment) and Riding (students learn gymnastics and exercises mounted on a horse). During each activity, and at the end of each session, the staff comprising of professional instructors, psychologists and trained volunteers will help the students to recognize, learn and practice Habits of Mind. This is done by allowing the students to point out the Habit of Mind that is the rationale behind that particular activity, and then linking the newly learned Habit of Mind to everyday situations. For instance, in one such lesson, the students are made to associate the mindset involved in successful interaction with the horses to Listening with Understanding and Empathy. In another lesson, the students will learn that the successful acts of saddling the horse, mounting, riding and dismounting involve impulse control and will be encouraged to apply act of Managing Impulsivity during the lesson to situations encountered in school. Parental informed consent was sought before the students embarked on the EQUAL intervention, as part of a routine school practice for any external activities.

All of the exercises are set down in the EQUAL Manual, which can be provided upon request. The overall structure of the 16 lessons and the content for each lesson was documented, as well as the logistics involved e.g. costs, manpower count, skills that are required in program facilitators, and the potential risks to the participant. It is a policy that all students who attend EQUAL receive a consistent program, regardless of which group and year cohort they are in. The details of adherence of the EQUAL intervention to the guidelines on treatment fidelity, which are put forth by the Behavioral Change Consortium of the National Institute of Health (Borrelli, Citation2011; Borrelli et al., Citation2005), are described in Appendix A.

2.3. Data collection

The Habits of Mind measures were scored at three time-points during the semester for all subjects undergoing EQUAL intervention, namely before intervention (Week 1 or 2), mid-way through the three-month intervention period (Week 8) and a week post-intervention (Week 12). Subjects from the other classes not receiving intervention were also assessed at the same time-points during the semester.

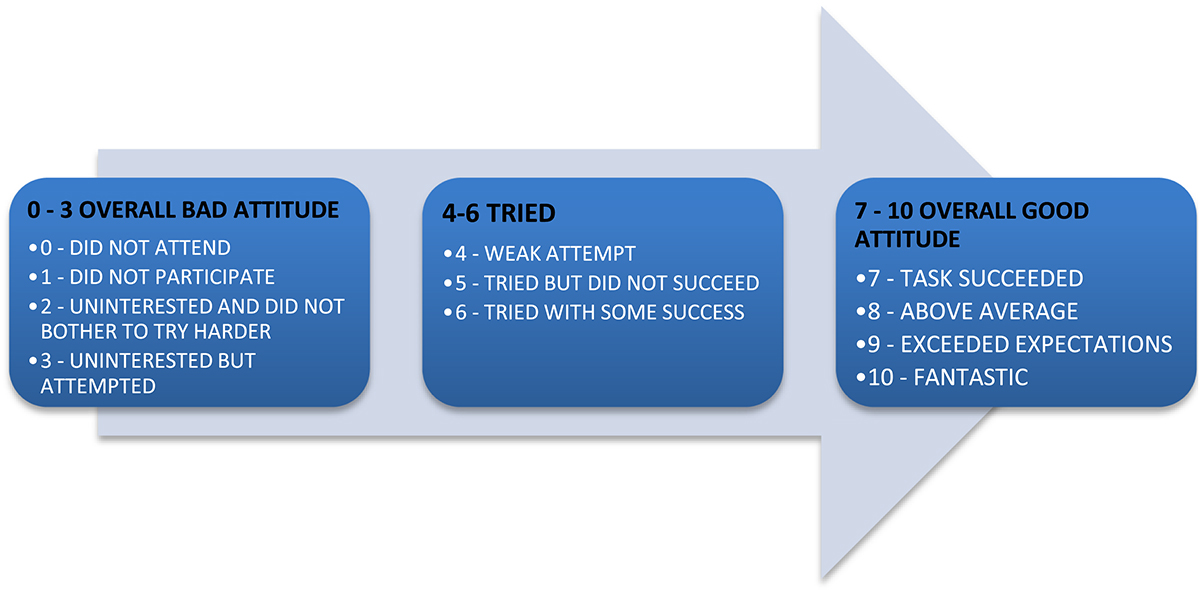

The five selected Habits of Mind: Persistence, Thinking Flexibly, Taking Responsible Risks, Managing Impulsivity, and Listening with Understanding and Empathy, were scored on a 10-point fully anchored Likert scale (scale of 0–10, with higher scores indicating better Habits of Mind). The scoring was based on rubrics that the school has given permission for release (detailed in Appendix A). To ensure standardization across the different classes and fair scoring, all the form teachers across the classes, together with the teacher aide and an EQUAL trainer (who would also collate independent Habits of Minds scores from the EQUAL facilitators) would conduct periodic benchmarking exercises at each time-point, by calculation of intra-class correlations of the Habits of Mind scores (see Appendix A).

Subsequent analysis of the outcomes of the intervention was performed by an investigator (N.F. Ho) not involved in the intervention or data collection, and had only access to anonymized data.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R version 3.2 (The R Core Team, Citation2015). To test possible gender differences between the intervention and non-intervention group student participants of year 2013, as well as year 2014, Yates-corrected χ 2 tests were used.

To examine whether equine therapy resulted in changes in each Habit of Mind measure over time in each semester, a linear mixed-effect model (conditional three-level growth model) was fitted (Singer & Wilett, Citation2003). Linear mixed-effect models are extensions of traditional linear regression models, with individual-level terms introduced to the regression models to account for the variability in change among individuals. Here, this multi-level model embodies different sub-models about how the construct measured in an individual student changes over time, and how these changes vary between all students across the different classes. Various research questions are asked in the model fitted below: level 1 questions about within-student changes over time, level 2 questions about between-student changes within a class, and level 3 questions about between-class changes.

2.4.1. Level 1 (within-student)

where Scores ijk represent the Habit of Mind score at time-point i for student j in class k; Time ijk represents the time-point in which the Habit of Mind is measured, i.e. pre-intervention, mid-intervention, and post-intervention for student j in class k; β 0jk refers to the score for student j at pre-intervention; r ijk refers to the within-student deviation between the observed and predicted scores (random error) at time i for student j in class k.

2.4.2. Level 2 (between-student, within-class)

where γ 00k refers to the mean at of the scores at time i across the students in class k; γ 01k refers to fixed regression coefficient of the gender of student j in class k; γ 10 refers to the average rate of change in scores across all the students within class k; μ 0jk refers to the between-student random error in class k; μ 1j refers to the between-student variation over time for class k.

2.4.2. Level 3 (between-class)

where, η 000 refers to the grand mean; η 100 refers to the grand intercept; ζ 000k refers to the between-class random error; ζ 000k refers to the between-class random error over time.

2.4.4. Substitute level 3 into level 2, and then level 1 models

In the model fitted, the fixed-effect variables included intercept, intervention, time, interaction between intervention and time, and gender; random-effect variables included slope of time, and intercept of time, student and class (as ratings are performed at different time-points on the students, which are nested within eight classes). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the linear mixed-effect model to determine whether there is statistical evidence of an interaction between intervention and time. To correct for multiple testing across the five Habits of Mind constructs, the Holm–Bonferonni method was used, which corrected for family wise error rate at an alpha of p < 0.05.

To examine the relationship between the rate of change in Habits of Mind over the semester and academic performance at the end of the semester, the students’ individual grade point averages were regressed on the individual slope estimates of the longitudinal change in each construct (i.e. the η

101 extracted from the above linear-mixed effect models), adjusting for gender.

To correct for multiple testing across the five Habits of Mind constructs, the Holm–Bonferonni method was used, which corrected for family wise error rate at an alpha of p < 0.05.

3. Results

No differences in gender were found between students in the non-intervention and intervention group in both the 2013 and 2014 cohorts.

3.1. Progressive increase in Habits of Mind scores across the three semesters in 2013 and 2014

Significant equine intervention by time effect were found across the five Habits of Mind examined (all p < 0.0001), which survived correction for multiple comparisons (Table (A) and Figure ). No initial group differences in Habits of Mind scores were found at baseline. For the year 2014 semester 1 cohort, significant intervention by time effect was found for all constructs, except for Managing Impulsivity (Table (B) and Figure ). In semester 2, significant intervention by time effect in the waitlisted group of students was found for all constructs, which survived multiple comparison testing (Table (C) and Figure ). However, unlike the cohort in 2013, the group receiving EQUAL intervention in both semester 1 and 2 exhibited higher baseline measures compared with non-intervention subjects in several Habits of Minds constructs (Semester 1: Thinking Flexibly, Taking Responsible Risks, Managing Impulsivity, Persistence (Figure ); Semester 2: Managing Impulsivity, (D) Persistence, and (E) Listening with Understanding and Empathy (Figure ); p < 0.0001).

Table 1. Statistical values showing an EQUAL intervention-by-time interaction in at-risk youths in (A) 2013 semester 2, and a similar interaction effect in an independent cross-over cohort in (B) 2014 semester 1, and (C) 2014 semester 2

Figure 1. Equine therapy improves Habit of Mind scores over time in one semester in 2013. The teacher ratings for the Habits of Mind constructs: (A) Thinking Flexibly, (B) Taking Responsible Risks, (C) Managing Impulsivity, (D) Persistence, and (E) Listening with Understanding and Empathy, for students of the 2013 cohort who were in the EQUAL program compared with students who did not partake in the program, showed an increase over the semester

Figure 2. Equine therapy improves Habit of Mind scores over time in 2014 semester 1. Higher baseline measures were found in the students about to enroll in the EQUAL program in semester 1 of year 2014 for the following four Habits of Mind constructs: (A) Thinking Flexibly, (B) Taking Responsible Risks, (C) Managing Impulsivity, (D) Persistence, but not (E) Listening with Understanding and Empathy. The teacher ratings for four Habits of Mind constructs (A) Thinking Flexibly, (B) Taking Responsible Risks, (D) Persistence, and (E) Listening with Understanding and Empathy, for those students in the EQUAL program, compared with students not in the program, showed an increase over the semester

Figure 3. Equine therapy improves Habit of Mind scores over time in two semesters in 2014. Higher baseline measures were found in the waitlisted students about to enroll in the EQUAL program in semester 2 of year 2014 for the following three Habits of Mind constructs: (C) Managing Impulsivity, (D) Persistence, and (E) Listening with Understanding and Empathy. The teacher ratings across five Habits of Mind: (A) Thinking Flexibly, (B) Taking Responsible Risks, (C) Managing Impulsivity, (D) Persistence, and (E) Listening with Understanding and Empathy, for those students in the EQUAL program, compared with students not in the program, showed an increase over the semester

3.2. Association between rate of change in character skills and grade point average across the semesters

Across all the five Habits of Mind examined, we found positive correlations between the longitudinal changes in the scores and grade point average across many constructs that survived multiple comparisons (Table , Year 2013 semester 2: Thinking Flexibly, Taking Responsible Risks, Managing Impulsivity, and Listening with Understanding and Empathy; Year 2014 semester 1: Thinking Flexibly, Managing Impulsivity, and Listening with Understanding and Empathy; Listening with Understanding and Empathy; Year 2014 semester 2: Thinking Flexibly, Taking Responsible Risks, Managing Impulsivity, and Persistence.)

Table 2. Correlation between rate of change in scores over the semester and grade-point average (GPA) scores at semester end in Year 1 students in (A) semester 2, and an independent cross-over cohort of Year 1 students in 2014 of (B) semester 1, and (C) semester 2

4. Discussion

The current findings indicate that three months of an equine-assisted learning program resulted in improvements in character skills in two independent cohorts of Year 1 students at-risk for academic and life failure across the three semesters in 2013 and 2014. The rate of change in character measures over the semester is associated with the students’ grade point average at semester-end.

EQUAL is unique in that it is the first program of its kind in Asia, and is part of a school’s core curriculum. Prior to the present study, its perceived success had been largely anecdotal, with positive feedback captured online and on film from participating children, volunteers, teachers and parents over the first three years of its inception. The present findings indicate that the equine-learning program has a significant effect on Habits of Mind measures over the semester in students in 2013 that was replicated in an independent cohort of 2014. We discuss how the EQUAL program could have improved each Habit of Mind construct. Taking Responsible Risks refers to the willingness to attempt safe tasks that are new and different, and not balk at the fear of making mistakes with this attempt (Costa & Kallick, Citation2008). The youths largely come from underprivileged family backgrounds, and would have likely never ridden a horse before. As they attempt to gain the trust of the horses, learn to groom, mount and ride them, the youths would learn that as long as they listen and follow the instructions given, these novel acts might not be intimidating as seemed initially. Persistence is the act of focusing and completing the task on hand. The youths could have gradually gain insight that as long as they stick to the instructor’s instructions during the lessons, and not give up in the tasks, they would eventually be able to master the skills to ride the horse successfully and engage in team games. Listening with Understanding and Empathy requires paying attention to another person’s opinion and to put oneself into the other party’s shoes. The horses elicit a range of emotions and emotions that are similar to humans (Bachi et al., Citation2012). In order to develop rapport with the horse, the youths are required to understand their behavior to gain their trust. Thinking Flexibly refers to the ability to change one’s stance after considering another person’s viewpoint. For instance, in a lesson while the youth is expected to trot the horse, the horse could be unwilling to move due to tiredness or fright; the youth has to learn to interpret the horses’ actions, and to react accordingly. Managing Impulsivity is to think carefully and consider various options before an action. As the youth riding the horse is expected to lead the horse (for instance changing the pace from cantering to trotting, and not collide with other youths in the arena), this calls for him/her to consider the environment around, and to communicate with the horse his/her intention.

The present findings of equine-related behavioral improvements over time agree with those from a randomized controlled study of an 11-week once-weekly equine facilitated learning after-school program on 5th–8th grade children, which included normal children and those at-risk of academic failure (Pendry, Carr, Smith, & Roeter, Citation2014). Parents of the children had rated their social competence pre-test and post-test, and the results of the study had indicated a moderate treatment effect on social competence (Pendry et al., Citation2014). Higher program attendance had also predicted the children’s behavior (Pendry et al., Citation2014), although the outcomes in the waitlisted group were not analyzed. Equine-related intervention has also been shown to increase perception of social support in typically developing youths (without psychological or behavioral problems) (Hauge, Kvalem, Berget, Enders-Slegers, & Braastad, Citation2014).

In the 2013 cohort of students, the baseline measures for both the intervention group and non-intervention group did not vary. However, we did note that in the cohort of 2014 students, across both semesters, higher baseline measures were found in the group that were about to participate in the EQUAL program in a weeks’ time. This suggests that the students were possibly excited about the prospect of participating in the program and may have behaved better. Nonetheless, the gradual improvements in their Habits of Mind mid-way and one-week post-EQUAL intervention in the student cohort of 2014 were still found. This begets the question of whether the behavioral improvements are due to novelty effects i.e. the elation and energy that ensues from a new and exciting experience (Anestis et al., Citation2014; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, Citation2002). Also, the students in the classes involved in the EQUAL program were transported to the ranch while the other students remained in school, and this may give rise to resentful demoralization (e.g. knowledge that they are missing out on a novel experience) (Anestis et al., Citation2014; Cook & Campbell, Citation1979). Alternatively, there was the possibility of an demand effect (McCambridge, de Bruin, & Witton, Citation2012). The teachers were aware that their students were attending the EQUAL program, and might possibly rated the intervention condition group higher if they had preconceived notions of the effectiveness of the intervention (Orne & Whitehouse, Citation2000). Nonetheless, the teachers, the aide and the EQUAL trainers had benchmarking sessions for grading the students pre-, mid- and post-intervention, so the demand effect would have been mitigated. Also, there was a correlation between the rate of change in character skills over the semester and the students’ grade point averages at the end of the semester, suggesting that the EQUAL-related improvements in character skills may have translated into better academic performances.

The findings of this real-world study, however, should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, due to the strict confidentiality of student school and medical records, we do not have access to the possible medical conditions of the students within each class (e.g. anxiety disorders, ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, or neurological impairments), as well as the knowledge of their family environment, that could likely shaped their behavior, and confounded the findings. The medical conditions or parental social-economic conditions could have been used to adjust for effects of findings, or to better match the participants in the non-intervention and intervention groups. Second, although more widely used instruments of behavior, social and emotion measures are available (Achenbach, Citation2014; Epstein, Citation2004), the EQUAL program was aligned with the less empirically studied Habits of Mind constructs that were used systematically by the school for the past 10 years in all aspects of the school curriculum. Third, we cannot establish whether the character skills improvements are due to the EQUAL program or mere novelty effects. Further longer term prospective studies of future cohorts of students should continue and should include, beyond Habits of Mind constructs, validated neuropsychological scales that are both student- and parent-rated to gain a more holistic perspective of the impact of equine therapy. To increase the reliability of the findings, a similar study with the same equine educational curriculum could be carried out in another pre-vocational school. To address the incremental efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the present intervention, EQUAL should also be compared with other interventional programs e.g. art or music therapy, over the same time period.

Funding

The manuscript is funded by the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Institute of Mental Health.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

New Fei Ho

New Fei Ho is interested in brain plasticity: how positive experiences can shape the brain’s capacity for growth. She holds several research grants aiming to examine the effects of non-pharmacological interventions on brain plasticity in neuropsychiatric disorders.

Jonathan Zhou

Jonathan Zhou has a special interest in equestrian and hopes that the interaction with the horses can serve as effective and holistic avenues for youths to learn and grow.

Daniel Shuen Sheng Fung

Daniel Shuen Sheng Fung is the Chairman Medical Board, Institute of Mental Health and a Senior Consultant with the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Phek Hui Jade Kua

Phek Hui Jade Kua holds joint appointment as a consultant in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, and Hospital Service Division, Ministry of Health. She is also the program director of Dispatcher-Assisted first Responder program, and is passionate about helping children and youths overcome their odds in life.

References

- Achenbach, T. M. (2014). Child behavior checklist for ages 6–18 (CBCL/6-18) . Burlington, VT: ASEBA, University of Vermont.

- American Hippotherapy Association, I . (2016). Hippotherapy research and supportive evidence . Retrieved from http://www.americanhippotherapyassociation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/HIPPOTHERAPY-RESEARCH-AND-SUPPORTIVE-EVIDENCE_Historical-Doc_for-2010website_JT.pdf

- Anestis, M. D. , Anestis, J. C. , Zawilinski, L. L. , Hopkins, T. A. , & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2014). Equine-related treatments for mental disorders lack empirical support: A systematic review of empirical investigations. Journal of Clinical Psychology , 70 , 1115–1132. doi:10.1002/jclp.22113.

- Bachi, K. , Terkel, J. , & Teichman, M. (2012). Equine-facilitated psychotherapy for at-risk adolescents: The influence on self-image, self-control and trust. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry , 17 , 298–312. doi:10.1177/1359104511404177.

- Borrelli, B. (2011). The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fidelity in public health clinical trials. Journal of Public Health Dentistry , 71 , S52–S63. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00233.x.

- Borrelli, B. , Sepinwall, D. , Ernst, D. , Bellg, A. J. , Czajkowski, S. , Breger, R. , … Resnick, B. (2005). A new tool to assess treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of health behavior research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 73 , 852–860. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.852.

- Cook, T. D. , & Campbell, D. T. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings . Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Costa, A. , & Kallick, B. (2008). Learning and leading with Habits of Mind: 16 Essential characteristics for success . Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD).

- Department of Statistics Singapore . (2015). Key household income trends . Retrieved from https://www.singstat.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-source/default-document-library/publications/publications_and_papers/household_income_and_expenditure/pp-s22.pdf

- Epstein, M. H. (2004). Behavioral and emotional rating scale-2: A strength-based approach to assessment . Austin, TX: PRO-ED.

- Fine, A. H. (2006). Handbook on animal assisted therapy: Theoretical foundations and guidelines for practice (3rd ed.). London: Academic Press Publications.

- Goh, C. B. , & Gopinathan, S. (2008). Education in Singapore: Developments since 1965. In B. Fredriksen & J. P. Tan (Eds.), An African exploration of the East Asian education (pp. 80–108). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Granados, A. C. , & Agís, I. F. (2011). Why children with special needs feel better with hippotherapy sessions: A conceptual review. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine , 17 , 191–197. doi:10.1089/acm.2009.0229.

- Hauge, H. , Kvalem, I. L. , Berget, B. , Enders-Slegers, M. J. , & Braastad, B. O. (2014). Equine-assisted activities and the impact on perceived social support, self-esteem and self-efficacy among adolescents - an intervention study. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth , 19 (1), 1–21. doi:10.1080/02673843.2013.779587.

- Kaiser, L. , Smith, K. A. , Heleski, C. R. , & Spence, L. J. (2006). Effects of a therapeutic riding program on at-risk and special education children. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association , 228 , 46–52. doi:10.2460/javma.228.1.46.

- Kamioka, H. , Okada, S. , Tsutani, K. , Park, H. , Okuizumi, H. , Handa, S. , … Mutoh, Y. (2014). Effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine , 22 , 371–390. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2013.12.016.

- Leong, L. (2009). The story of northlight—A school of opportunities and possibilities, Part I . Retrieved from https://www.cscollege.gov.sg/Knowledge/Pages/The-Story-of-Northlight-A-School-of-Opportunities-and-Possibilities.aspx

- McCambridge, J. , de Bruin, M. , & Witton, J. (2012). The Effects of demand characteristics on research participant behaviours in non-laboratory settings: A systematic review. PLoS One , 7 , e39116. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039116.

- Ministry of Education, S. (2012, January 16). School drop-out rate after commencement of northlight school and assumption pathway school . Retrieved from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/parliamentary-replies/2012/01/school-drop-out-rate.php

- Mourshed, M. , Chijioke, C. , & Barber, M. (2010). How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better . New York City, NY: McKinsey & Company.

- Orne, M. T. , & Whitehouse, W. G. (2000). Demand characteristics. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of Psychology (pp. 469–470). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press.

- Pendry, P. , Carr, A. M. , Smith, A. N. , & Roeter, S. M. (2014). Improving adolescent social competence and behavior: A randomized trial of an 11-week equine facilitated learning prevention program. The Journal of Primary Prevention , 35 , 281–293. doi:10.1007/s10935-014-0350-7.

- Selby, A. , & Smith-Osborne, A. (2013). A systematic review of effectiveness of complementary and adjunct therapies and interventions involving equines. Health Psychology , 32 , 418–432. doi:10.1037/a0029188.

- Shadish, W. R. , Cook, T. D. , & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental deisngs for generalized causal inference . Boston, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Sim, W. (2015, November 8). The race issue: How far has Singapore come? The Straits Times . Retrieved from http://www.straitstimes.com/politics/the-race-issue-how-far-has-singapore-come

- Singer, J. D. , & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence . New York: Oxford University Press.

- The R Core Team . (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing . Vienna. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/

- Trotter, K. S. , Chandler, C. K. , Goodwin-Bond, D. , & Casey, J. (2008). A comparative study of the efficacy of group equine assisted counseling with at-risk children and adolescents. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health , 3 , 254–284.10.1080/15401380802356880

- Whalen, C. N. , & Case-Smith, J. (2012). Therapeutic effects of horseback riding therapy on gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics , 32 , 229–242. doi:10.3109/01942638.2011.619251.

Appendix A

1. Assessment of treatment fidelity of the equine-assisted learning program (EQUAL) Intervention, adapted from (Borrelli, 2011)

The Behavioral Change Consortium of the National Institute of Health has put forth guidelines for treatment fidelity across five, mutually exclusive domains: Study Design, Provider Training, Treatment Delivery, Treatment Receipt, and Treatment Enactment (Borrelli et al., 2005). The following table indicates the adherence of the EQUAL intervention to these guidelines.

2. Rubrics for evaluating students’ Habits of Mind (taken with permission from the NorthLight school)

3. Inter-rater reliability

During the periodic bench-marking exercise performed pre-, mid-, and post-intervention, the Habits of Minds scores from randomly chosen students would be compared among the from the form teacher, teacher aide, and EQUAL psychologist.

The intra-class correlation among the fixed raters, for each of the Habits of Mind scores of the randomly selected students, is calculated by (BMS – EMS)/BMS + (k−1) × EMS, where BMS: Between-student target Mean Square, EMS: residual sum of squares, and k: number of raters.

The intra-class correlation values for each construct in each semester range from 0.62–0.84.

References

Borrelli, B. (2011). The Assessment, Monitoring, and Enhancement of Treatment Fidelity In Public Health Clinical Trials. J Public Health Dent, 71(s1), S52-S63. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00233.x

Borrelli, B., Sepinwall, D., Ernst, D., Bellg, A. J., Czajkowski, S., Breger, R., … Resnick, B. (2005). A new tool to assess treatment fidelity and evaluation of treatment fidelity across 10 years of health behavior research. J Consult Clin Psychol, 73(5), 852-860. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.852