Abstract

Social studies have often been explored as dis-embodied which results in a limited view of what happens in the classroom. Based in Dewey’s transactional view of embodied relationality, Todd’s discussion on the liminality of pedagogical relationships and recent theoretical contributions into embodied learning and body pedagogics, the purpose is to explore students’ embodied engagement as an important but often overlooked aspect of social studies in school. The focus is on pedagogical encounters in terms of how students’ actions acquire a certain function in the classroom. Three embodied engagements— (i) disengaged encounters, (ii) screened encounters, and (iii) educative encounters—are identified and discussed in terms of the liminality of pedagogical encounters.

Public Interest Statement

Because social studies have been explored and treated as dis-embodied, there is a risk that we miss out on complex relational aspects that concrete classroom life is very much about. The focus of this study is on how students’ and teachers’ actions acquire a certain function in the classroom. We share the perspectives of scholars who point out the pedagogical potential of social studies if teaching and learning in the classroom move towards an embodied pedagogy. The results show concrete examples of how being receptive to embodied opportunities have the potential to change and transform teacher-student relationships and help students and teachers to open up new ways of discussing these relations and classroom practices.

1. Introduction

In recent years, scholars interested in social studies as a school subject have shown how teaching and learning in social studies classrooms can be understood through instruction, dialogue, cognition, reflection, concepts, thinking, writing, reading and awareness (e.g. Bickmore & Parker, Citation2014; Brooks, Citation2011; Hess, Citation2002; King, Citation2009; Nokes, Citation2014; Savenije, Van Boxtel, & Grever, Citation2014; Walker Beeson, Journell, & Ayers, Citation2014). Despite these important contributions, our knowledge about the teaching, learning and pedagogy of social studies in classrooms is mostly limited to explorations of cognitive, verbal and/or written aspects of the educational situation.

As recognized by, for example, Ord and Nuttall (Citation2016) issues of embodiment or the embodied nature of education has been surprisingly absent in certain areas of research in teaching and learning, and like many other school subjects, social studies have often been explored as dis-embodied (cf. Almqvist & Quennerstedt, Citation2015; Kazan, Citation2005; Ord & Nuttall, Citation2016). The risk with treating social studies as dis-embodied is that we do not fully understand or embrace its pedagogical potential and as argued by Sharon Todd (Citation2014) miss out on complex and important contextual and relational aspects that concrete classroom life is very much about.

The purpose of this study is to explore embodied engagements in terms of what bodies do and become in a social studies classroom. The focus is on how students’ and teachers’ actions acquire a certain function in the classroom. By way of conclusion, the results of the analysis are discussed in terms of the liminality of pedagogical encounters in classroom practice in order to further scrutinize the pedagogical potential of social studies if teaching and learning in the classroom moves towards what Kazan (Citation2005) term an embodied pedagogy.

The paper is grounded in John Dewey’s transactional view of embodied relationality and Todd’s discussion on the liminality of pedagogical relationships, and builds further on the recent theoretical contributions into embodied learning and body pedagogics of Andersson, Garrison, and Östman (Citation2018) and Shilling (Citation2007, Citation2016) that eschew those ontological dualisms which render the body either a passive product of structural forces or a vehicle of unrestrained agency. In two recent articles, Shilling (Citation2017, Citation2018) addresses the challenge of exploring empirically embodied learning and elaborates on two analytical models developed to explore processes associated with teaching and learning (cf. Andersson et al., Citation2018) and empirically informed investigations to advance sociological writings on the embodied character of cultural formation and transformation. From this perspective, we are particularly concerned to focus on the relationship between those “social, technological and material means through which [education] practices are transmitted, the varied experiences of those involved in this learning, and the embodied outcomes of these processes” (Shilling, Citation2007, p. 13; cf., Citation2017).

In this way, we can “transgress” the separation of mind and body and explore participation in a social studies classroom as always being embodied and thus say something about how embodied pedagogies enfold. In so doing, what is distinctive about our own contribution is that it is an empirical study that enables us to explore the fine-grained detail of how embodied engagements constitute an important but often overlooked aspect of social studies in school. So rather than focusing on what each student learn in the explored situations, we argue that students and teachers always enter pedagogical encounters as some-body. This perspective thus contributes to the field by creating a broadened understanding of teaching, learning and pedagogy in social studies classrooms furthering arguments for an embodied social studies classroom.

2. Theoretical considerations

In this section, the theorisations of the body in educational research are discussed, and a transactional approach to understanding embodied aspects of education is introduced. Todd’s notion of the liminality of pedagogical encounters is also presented as a way of exploring and discussing the pedagogical situation in the classroom in terms of an embodied engagement with practice.

2.1. Theorising bodies

At least since the mid-1990s, theorisations of the body have become more prominent in educational research using, for example, phenomenological (e.g. Stolz, Citation2015; Thorburn & Stolz, Citation2015), post-structural (e.g. De Freitas & Sinclair, Citation2014), ethnomethodological (e.g. Björk-Willén & Cromdal, Citation2009) Bernsteinian (e.g. Evans, Davies, & Rich, Citation2009) somaesthetic (Bresler, Citation2013) Bourdieusian (Shilling, Citation1991, Citation1992) or pragmatic (Quennerstedt, Öhman, & Öhman, Citation2011; Shilling, Citation2004) approaches. From these theoretical strands, numerous authors have criticised the Cartesian intellectualism that implies a dualism between the immaterial mind and the material world and subsequently prioritises mind or conscious intellect. These authors have instead argued that there is no given metaphysical separation between intelligent and bodily conduct, but that we conceptualise in and through our bodies (cf. Evans et al., Citation2009; Kelan, Citation2010; Macintyre Latta & Buck, Citation2008; Zembylas, Citation2007). A growing number of educational scholars are also concerned with how certain perspectives of the body tend to ignore the materiality of bodies and, subsequently, neglect embodied experiences in education (e.g Evans et al., Citation2009; Horn & Wilburn, Citation2005; Kelan, Citation2010; Larsson & Quennerstedt, Citation2012; Macintyre Latta & Buck, Citation2008; O’Loughlin, Citation2013; Ozolins, Citation2013; Wilcox, Citation2009).

In this paper, the intention is not to resolve tensions produced by the epistemological separation of mind and body. Rather, by turning to pragmatism and Dewey’s transactional perspective as one way to explore embodied aspects of pedagogical encounters, teaching, learning and pedagogy in social studies is empirically approached as embodied rather than dis-embodied, and thus taking into account what bodies do and become in social studies classrooms. In this vein, Wilcox (Citation2009) argues that students’ lived experiences are always embodied and that they need to be thoughtfully incorporated into the classroom. If they are not, there is a risk that educators will foster dualisms of inside/outside the classroom and mind/body and fail to see that embodily engaging students is part of their responsibility: “And so we let students sit in the classroom, hoping that the state of their bodies does not reflect the state of their minds” (p. 107). Our interest is accordingly about understanding what is going on in the classroom when teachers and students not only enter as cognitive beings but also in an embodied sense as some-body. In this way we can say something about events in the social science classrooms as being, what Dewey (Citation1938b) called, educative, mis-educative or even non-educative in an embodied sense.

2.2. Education with the body in mind—a transactional approach

For Dewey, education, teaching and learning are complex processes that are simultaneously social, embodied and transactional in nature (Prawat, Citation1999). In the article “Body and Mind” (Citation1928), Dewey acknowledges the body’s role in teaching and learning and stresses the problem with the separation of body and mind: “I do not know of anything so disastrously affected by the habit of division as this particular theme of body-mind” (p. 5). Sullivan (Citation2002) further describes how Dewey considers bodies as transactional, i.e. that bodies and their various (cultural, political and physical) “environments co-constitute one another in dynamic ongoing ways” (Sullivan, Citation2002, p. 202).

Approaching bodies and environment as transactionally co-constituted suggests a move away from interactional perspectives that suggest people and objects exist as hermetically separated entities that bump into yet leave each other unaffected. Instead, a transactional approach implies that people and their environments are always both shaping and being shaped through ongoing transactions. This construction is located in the actor-environment transaction itself and focuses on the influence of contextual conditions on human action. Biesta and Tedder (Citation2006) refer to the latter as “an understanding which always encompasses actors-in-transaction-with-context, actors acting by-means-of-an-environment rather than simply in an environment” (p. 18). Hence, in this study, the students’ environment denotes more than the school or the classroom, and by focusing on embodiment in a transactional perspective, the attention is accordingly turned from bodies as pre-determined metaphysical entities separated from the mind, to what bodies do and become in and through their functional coordination with the environment. In accordance with a transactional perspective, bodies and environments both mutually and simultaneously form and are formed by the other (Andersson et al., Citation2018). In line with this, education can be understood in terms of an embodied engagement and functional coordination with practice (Biesta & Burbules, Citation2003). This implies that education can be explored with “the body in mind” and thus focus on how students’ and teachers’ actions acquire a certain function in a social studies classroom.

2.3. Liminal pedagogical relationships in classroom practice

In anthropology, liminality is often described as the transition between two phases when individuals are in a state of limbo. Anthropologist Victor Turner (Citation1967), for example, explored rituals and expanded theories on “the liminal period” in rites of passage (e.g. birth, puberty, marriage, death). Turner focused on how major life transitions were experienced and how people cope with them and the concept of liminality (i.e. the state of being on a threshold) thus being a condition in tribal communities as well as in contemporary societies (Bigger, Citation2009).

However, as shown by Todd (Citation2014) and Conroy (Citation2004), there are applications of a modified concept of liminality in an educational context. Building on Turner’s notion of the liminal, Conroy, for example, regard the concept “as an ontological space where the normal rules of structure and status do not apply/…/as eruptive, emerging out of those interstices that exist inside bounded space as well as at and across borders” (p. 55). In line with Dewey’s transactional approach, and to further our own concern with the embodied pedagogy of teaching and learning, Todd (Citation2014) instead uses the metaphor of liminality, or the threshold, to emphasise that pedagogical relationships are about encountering the undetermined. These encounters have the potential to change and transform us and thus be what Dewey calls educative (Citation1938b). This is advanced by Howes (Citation2008) as a distinction between educative, miseducative and noneducative experiences (see also Bassey, Citation2010; Scott Webster, Citation2017). What Dewey reminds us of is that learning is not always educative. Instead, “some learning like indoctrination, is miseducative where attitudes like boredom, callousness and close-mindedness emerge and which narrow opportunities for further growth” (Scott Webster, Citation2017, p. 332). While educative embodied pedagogies are about what promotes the growth of further experiences, miseducative embodied pedagogies are about what hinders growth in terms of that we potentially learn, but do not grow (Hildreth, Citation2011). Experiences are thus miseducative since they limit the depth and breadth of future experiences. Noneducative pedagogies, on the other hand, involve experiences that neither supports nor hinders further growth. Howes (Citation2008) further argues that: “it is not the activity ‘per se that is conductive to growth’ (Dewey, Citation1938a/1953, p. 45). It is the teacher’s and student’s communal interaction around the activity and its qualities that constructs purposes and educative experiences” (p. 538). What Dewey reminds us of here is that education is not educative just because students learn. Instead educative refers to the possibility to become something not already decided, and that in this, with Todd’s (Citation2014) words, liminal space, people’s embodied engagements are imperative.

Todd (Citation2014) accordingly argues that such transformative pedagogies occur in an embodied liminal space as disruptive moments that cannot always be fully articulated in words. Educational practices are instead always embodied and in transaction related to other bodies and the environment. Accordingly, any pedagogical encounter, such as the teacher-student relation, can be understood as an embodied engagement. Todd (Citation2014) writes:

The specifically pedagogical, transformative relationship is therefore not about control or predicting the future, about learning a particular piece of subject matter, or about measuring outcomes, although these are all significant aspects of our educational work. It is, rather, about making room within educational discourses for the kind of existential, liminal aspects of the teacher-student relationship which already go on, even if we fail to name or address them (p. 242).

The liminal space can function as a horizon of possibility that guides teachers’ educational work. The teacher-student relationship in classroom situations is always an engagement with a particular context and particular others, and is thus contextual, relational and embodied. This means that students and teachers can be understood as coming into being in educational practice as “live subjects”, or as some-body.

Not unlike Conroy (Citation2004) when stressing the priority teachers must place on the spontaneous and unexpected moments that arise in the classroom—“a pedagogy of spontaneity and of the moment” (p. 61), Todd notes that pedagogical practices are not purely mental processes, but are also socially embedded, embodied and involve uncertainty. In educational theory teaching is usually defined as being successful when a teacher succeeds in fulfilling her intention and bringing about desired changes in students. Simply put, a teacher’s intention is defined as making students learn (Biesta, Citation2006; Garrison & Rud, Citation1995). Of course, having an intention and acting in line with it is no guarantee that the desired change will take place. In an attempt to theorize the teacher-student relationship differently Todd suggests a temporary bracketing of intentionality in order to stress that people’s changes and becoming are not always dependent on certain desired changes—lives change in unpredictable ways and such change can be both disturbing and delightful and “make a difference to who we, as students and teachers, become in the process” (Citation2014, p. 243).

Following Todd and Dewey’s transactional approach, we see pedagogical encounters as open-ended and ongoing processes of continuous readjustment that have the potential to initiate becoming (see Biesta, Field, Hodkinson, Macleod, & Goodson, Citation2011; Hager, Lee, & Reich, Citation2012; Hodkinson, Biesta, & James, Citation2007; Ozolins, Citation2013; Todd, Citation2014). As they are theorised in the study, pedagogical encounters are what students and teachers do and become as a functional coordination with practice.

3. Review of research

3.1. The body’s role in school settings

In many school settings, bodies are often put in the background with regards to studies of teaching, learning and pedagogy in the classroom. Here the scene is dominated by mental functions and processes (e.g. attentions, thoughts, memory, cognition) (Hager et al., Citation2012; O’Loughlin, Citation2013; Ord & Nuttall, Citation2016). As a consequence, students’ learning is regarded as primarily involving the mind and not the body. In this vein, Kazan (Citation2005) argues that “teachers who do acknowledge embodiment […] benefit from a more complex understanding of the students and their classroom” (p. 381). Estola and Elbaz-Luwisch (Citation2003) further state that: “Because body has been considered more as a ‘problem’ or a ‘sin’ than a ‘treasure’, there is much that is unsayable about bodies in classrooms” (p. 702), and Kazan (Citation2005) even goes so far as to say that by not considering the body teaching cannot be done effectively. There is accordingly a knowledge gap in fields predominantly exploring cognitive aspects of learning, and research on teaching, learning and pedagogy in the social studies classroom is one of these fields (cf. Gilbert, Citation2013).

However, there are notable exceptions of fields where the body have been very much in focus in “class room” studies. Within physical education, research on embodied aspects of learning has been obvious exploring aspects from motor learning to socio-cultural and situated aspects on learning (Quennerstedt & Maivorsdotter, Citation2016 for an overview see Ennis, Citation2016). In arts education, aesthetic and multimodal aspects of embodied learning have often been foregrounded (Fleming, Bresler, & O’Toole, Citation2015). Anttila (Citation2015) in an overview on embodied learning in the arts also highlight how arts can touch people on an embodied level and the potential for transformative meaningful experiences in arts education is promoted when embodiment and active practice is foregrounded. In a recent handbook on arts and education (Fleming et al., Citation2015) embodiment is further emphasised using concepts like embodied knowing, emotion, performance, expression and meaning.

In early childhood education issues relating to pedagogies of play have been prominent and in exploring the relation between play and learning the body becomes implicitly present (Pramling-Samuelsson & Asplund-Carlsson, Citation2008). By exploring (e.g. Martlew, Stephen, & Ellis, Citation2011) or criticising (e.g. Stirrup, Evans, & Davies, Citation2017) play-based pedagogies this strand of research has contributed to knowledge about the relationship between children’s actions in play and what they learn. Another apt example is a study by Klaar and Öhman (Citation2012) where they by using Dewey’s theories on educative experiences focus on toddler’s embodied meaning-making in pre-school.

There are also examples of studies of embodied aspects of educational practice in music education (e.g. Mark & Madura, Citation2013), mathematics (e.g. Alibali & Mitchell, Citation2012; De Freitas & Sinclair, Citation2014; Radford, Citation2009), science education (Almqvist & Quennerstedt, Citation2015) and critical literacy (e.g. Enriquez, Johnson, Kontovourki, & Mallozzi, Citation2016; Johnson & Vasudevan, Citation2012; Kazan, Citation2005). Our ambition is to build on the research within these areas and much in the same way as within these school subjects reposition the body in the social sciences in school.

3.2. The body’s role in social studies

Also within social studies, there have been attempts to involve the body in the educational practice focussing on pedagogical models that aim to integrate mind, body and emotions in learning. Broom and Murphy (Citation2015) explore the implications of such models for secondary social studies in Canada and New Zealand and conclude that they promote reflexivity, growth and critical thinking. Similarly, Clingerman (Citation2014) emphasises that in the fields of religious studies, ecology and the environment, the classroom is not a place for disembodied knowledge. The author also argues for a “messiness” of social studies and seeing its value as a cognitive, physical and emotional enterprise. When addressing conflicting perspectives in classroom discussions in citizenship education, Bickmore and Parker (Citation2014) find that teachers offer students embodied, emotional and intellectual engagement with conflicting perspectives by having them play character roles or take ideological positions that are different from their own.

In exploring the role of bodies in social studies classrooms, Elbaz-Luwisch (Citation2004) emphasises the real materials of students’ lives and the body’s implicit knowledge that are waiting to be tapped and used when discussing controversial public issues and conflictual subject matter. Elbaz-Luwisch argues that the lived experience of the body becomes a kind of touchstone: “I find these understandings of the body as the ground, the organizing template for individual and shared experience, useful in orienting to a pedagogy that would pay attention to the body” (Elbaz-Luwisch, Citation2004, p. 22).

In the above examples and models, the importance of embodying social studies is highlighted. However, the studies are still, in contrast to the theories of Dewey or phenomenological ideas, linked to a dualistic body/mind scheme. In this way, they risk maintaining a metaphysical separation between body and mind by arguing for a consideration of both. They accordingly take a different stance towards embodied dimensions of pedagogical practice than the phenomenological or pragmatic theoretical positions used within other subject areas. The risk is that they are blind to students’ corporeal presence, their bodily engagement in the classroom and how students always enter all pedagogical situations as some-body. In this sense our study contributes to the field in focusing the how of the embodied social studies classroom.

4. Method

Recognising that students and teachers enter as and become some-body in pedagogical encounters, this study examines the embodied engagements that occur in a social studies classroom. The focus of the analysis is on pedagogical encounters in terms of how students’ actions acquire a certain function in the classroom. Taking a transactional approach, the study highlights the coordinated embodied engagements with others (teachers, student peers) and the environment (classroom practice, classroom materiality, subject matter, assignments). The insights gained from this particular study could help to develop new knowledge about what is going on in classrooms and thereby re-understand social studies as embodied rather than dis-embodied. The risk is otherwise that we miss out on complex and important contextual and relational aspects that concrete classroom life is very much about (cf. Todd, Citation2014).

4.1. Data collection

The data were collected in an upper secondary school in Sweden during the autumn term of 2015. The empirical material consists of video recorded social studies lessons from two different subject areas (criminology and sociology). In contrast to interviews, video recordings provide data close to social practices and everyday situations. Potter (Citation2002) talks about passing the “dead scientists test” (p. 12). This means that the investigated situation, in contrast to, for example, interviews, would have occurred even if the researcher had been absent. In a transactional perspective the point of departure is the processes that take place in the encounter and the relations that arise in actions in specific events. Of course, video recorded or other observational data is not closer to “reality” than other data. Instead different kinds of data answer different questions. However, getting close to the situation makes it possible to document, view, review and analyse what occurs when students and teachers act-in-context.

The participants in this study were two upper secondary school teachers, one female and one male teacher, from a school in a middle-sized town in Sweden. The teachers had answered positively to a request sent to the principal of the school the previous term about participating in a research study that investigates teaching and learning in a social studies classroom. Both the teachers were in their forties and had worked at the school between ten and fifteen years. They had similar teaching backgrounds and taught different subjects within the social sciences. The female teacher was a social science and history teacher and the male teacher a business economics and social science teacher. They both taught in the Economics Programme and they were familiar with the class from having taught them the previous two years in grade ten and eleven. Thus, the teachers knew the students well, they had an open manner and were flexible in responding to students’ needs. Students seemed to appreciate their teachers that brought a relaxed atmosphere to the classroom.

One of the greatest pitfalls in conducting empirical research successfully is the inability to gain access to the research field, in this case to teaching practices and teachers (Johl & Renganathan, Citation2010). The success of data gathering depends directly on the possibilities of finding informants and gaining access to the research site, and on how well the researcher can build and maintain relationships with the participants (teachers and students). In this study, the researchers used “personal access” (Laurila, Citation1997) or a more informal way of obtaining access to the chosen school. In this case, one of the researchers knew relevant individuals at the school from supervising practical work of student teachers. These contacts probably facilitated the process of finding teachers that wanted to participate in the study.

The lessons explored consist of small group activities, whole class lectures and student presentations. The 31 students in the class – 21 girls and 10 boys—are in their third and final year of the Business Management and Economics Programme. The data included in the study originates from seven different lessons and a total of 6 h of video recordings. For a description of the lessons see appendix.

During the longer 75-min lessons (lessons 1, 2, 5 and 6) two researchers participated with one camera on a tripod capturing the collective actions of in the classroom, and one hand camera moving in close in order to capture small group discussions. When the class was divided into small groups the researchers followed one group each. In the three half-class lessons (lessons 3, 4 and 7) one researcher participated filming the group presentations with one camera on a tripod.

4.2. Ethical considerations

From an ethical perspective, video recording as a data collection method requires the consent of the teachers and students involved. The two teachers were informed about the purpose of the study and consented to taking part in it. The students were informed about the study by one of the researchers during a sociology class. On this occasion, the researcher also gave a brief presentation about academic research and writing and discussed the compulsory upper secondary diploma project that the students were about to start planning. This was done in order to inform the students about the research process, stimulate their interest in scientific issues in general and awaken their curiosity about the study in question. The students were provided with information about the intent, nature and scope of the study. All the students were aged 18 and gave their active consent to be part of the study, providing that the camera captured the whole class and not individual students.

4.3. Data analysis

Exploring embodied engagements in a social studies classroom has its challenges. As Estola and Elbaz-Luwisch (Citation2003) state, “attention to the body is a challenge to both the researchers and the methods used” (p. 715). These challenges can be summarised as the difficulty in exploring the dazzling complexity of any educational situation involving verbal and non-verbal actions and communication, teachers and students, teaching aids, the materiality of the classroom as well as the context as a whole (cf. Armour, Quennerstedt, Chambers, & Makopoulou, Citation2017; Quennerstedt et al., Citation2011). In an attempt to manage this complexity we have been guided by two analytical questions: (i) How do aspects of embodied engagements manifest themselves in the social studies classroom? (ii) What do bodies do and become in terms of functional coordination with practice? By way of conclusion, the results of the analysis are also discussed in terms of the liminality of pedagogical encounters in classroom practice.

4.4. Analytical steps

The analysis is conducted in three steps: (i) distinguishing pedagogical encounters, (ii) identifying embodied engagements and (iii) categorising embodied engagements by the function of actions-in-context and thus understanding them as educative, miseducative or noneducative.

4.4.1. Step 1—distinguishing pedagogical encounters

According to Todd (Citation2014), pedagogical encounters are characterised by their potential to be transformative. Distinguishing pedagogical encounters in this study is thus about focusing on the actions of students and teachers and their engagement with what Todd calls a particular context and particular others.

In the study, pedagogical encounters involve teacher-student and student-student relations in classroom practice. These potentially transformative practices for such relations are played out materially between bodies in the present in terms of what bodies do and become in the transaction. This step is used for selecting events for further in-depth analysis in step 2.

4.4.2. Step 2—identifying embodied engagements

A transactional approach (Klaar & Öhman, Citation2014; Quennerstedt et al., Citation2011) is used for the verbal and non-verbal actions and communication in the analysis of the video recordings. In transactional investigations, individuals and the environment are described in terms of relations that arise in actions in specific events. In this study, it means focusing on the pedagogical encounter as a form of embodied relationality with others (students and teacher) and the environment (e.g. classroom materiality, subject content, tasks) in classroom practice. The analytical question guiding us in this step is how aspects of embodied engagement are manifested in the social studies classroom.

Analysing what students and teachers do makes it possible to identify the function that their actions acquire in the classroom in terms of embodied engagement. This can involve gestures, body language, postures, communication, student actions, teacher actions, materiality of the classroom, the assignment, or the subject content. However, all aspects of embodied engagement are not relevant in a pedagogical encounter. In this study, we focus on situations in which the body is foregrounded and the action is connected to school subject matter. A student shaking his/her head can be described as an embodied action, but has often no obvious relevance for the pedagogical encounter.

4.4.3. Step 3 categorising embodied engagements

After identifying how aspects of embodied engagement manifest themselves in the social studies classroom, and what kind of function students’ actions acquire in the classroom, the third analytical step involved categorising the different embodied engagements into coherent themes. Each theme can be seen as diverse embodied engagements in the social studies classroom that are analytically separated by the function they have in the explored data. For example, if the teacher is lecturing and the students are sitting in rows at desks in the classroom, or if students are involved in a United Nations assembly role-play, the different functions of the engagement will be categorised as different themes. In order to further understand the embodied engagements as educative, miseducative or noneducative, we finally return to Dewey (Citation1938b) and scrutinize the engagements in terms of what extent they promote or narrow the depth and breadth of further growth of experience i.e. the qualities of the embodied engagement.

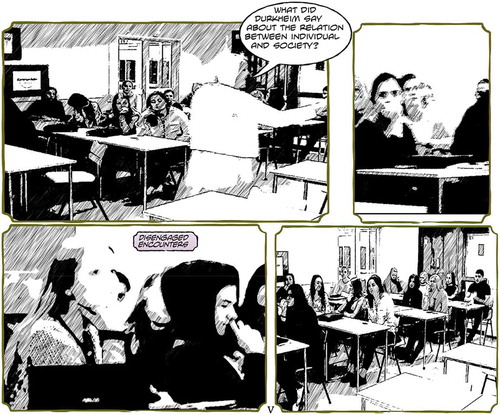

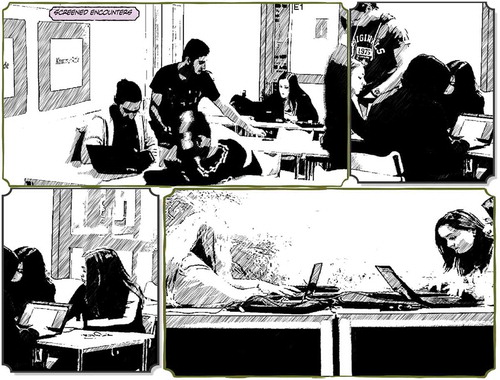

Two or three different situations are exemplified in each theme in order to illustrate some of the differences and complexities within the themes. Inspired by Eklöf (Citation2013) and Gibbs, Quennerstedt, and Larsson (Citation2017) short comic strip sequences created from the video recordings using the program Comic Life 3 are also used in order to complement the written text. The clips were created through all three authors agreeing on sequences particularly suitable to illustrate the themes in terms of the embodied nature of teaching, learning and pedagogy in the classroom. The comic strips are thus used to illustrate the result in a representative way hopefully making the embodied aspects of the results come to life, and as a consequence also avoid some of the ethical issues associated with using film and photo-images for data illustration.

5. Results

In the analysis, three comprehensive themes of embodied engagements are identified: (i) disengaged encounters, (ii) screened encounters and (iii) educative encounters. These embodied engagements are analytically separated by the functions that different actors (and artefacts, context, assignment etc.) have in the transaction. In order to make sense of the complexity of the educational situation, each theme is introduced in terms of what students and teachers do and become as some-body in social studies classroom practice. Within each theme, the functional coordination of students, teachers, classroom settings, tasks and subject content in terms of embodied engagement is then described and illustrated by comic strips in order to at least to some extent convey bodies-acting-in-classroom-settings. Finally, each theme is further scrutinized in terms of the liminality of pedagogical encounters in classroom practice thus recognizing them as educative, miseducative or noneducative.

Presenting embodied engagement separately in this way could indicate clear borders between them. This is however not the case. From a transactional perspective, knowledge about something emerges from transactions with the environment and feeds back into this environment in an unending process. Thus, although transaction never starts or stops, it is still possible to explore the relations that arise in specific events and the functions that these actions acquire. The themes are accordingly not mutually exclusive in classroom practice, but are often, as will be seen, simultaneous and intertwined in real situations.

5.1. Disengaged encounters

In the social studies lessons students as some-body come into being as disengaged. Disengaged here is in a transactional sense where students both disengage themselves through their actions as well as become disengaged from doing social studies by the teaching or by the task at hand. The discipline of the task, seemingly choreographed lessons, the physical positioning of the teacher and students’ presentations all appear to narrow the possibilities for educative encounters. Instead, students’ functional coordination with practice seems disconnected and thus in many senses noneducative (cf. Dewey, Citation1938b).

The disengaged encounters are manifested in the different teaching methods used by the teachers inside and outside the classroom. In the studied lessons, disengagement is predominately, but not always, visible when the classroom practice is “traditionally” teacher-led, or more self-directed, where students are encouraged to take a greater responsibility for their own learning and work individually or in small groups with a certain task. Three situations are used to illustrate this theme: the (teacher-led) lesson, the oral presentation and the student task.

In some of the lessons, as illustrated in Figure , the materiality of the seating arrangements in the classroom and the teacher’s actions has a clear function in students’ embodied engagements. In several of the lessons, the teacher appears to act like an entertainer standing at the front of the class and thus embodying a control of the classroom activities, while the students sit passively in rows and listen to the teacher lecturing about in this case Durkheim’s theories (see Figure ). This mirrors what Kazan (Citation2005) describes as a physical embodied position of authority. The teacher’s questions about previously taught subject content function as instructional cues that tell students what to do and how to do it. The subject content thus becomes a pre-determined knowledge of social studies that should be memorised and controlled, rather than something that allows students to encounter the undetermined. Certain ways of acting are therefore privileged and the students’ collective co-construction is guided towards a disengaged classroom behaviour (sitting still, raising their hands, answering questions and paying attention). This reflects Wilcox warning that educators fail to acknowledge the embodied engagement of students as a remedy of fostering a mind/body dualism.

Where and how the teacher chooses to position herself/himself during the lesson also has a function in terms of what students become as some-body in terms of passive listeners. It also says something about the power relations in the classroom where the teacher becomes the manager of the educational practice (cf. Gore, Citation2001). In many of the lessons the teacher tries to get the attention of the whole class or give instructions to the students. Sometimes the teacher also stands beside the seated students, and Figure shows a (female) teacher hovering over her student(s) as she is about to clarify the assignment since the students does not seem to be working on task.

Where teachers position themselves in the classroom and in relation to the students seems to influence the collective co-constructed engagement and/or disengagement with their social studies class and affects what students as some-body become. The above illustrations show little interaction or engagement between the students and their teacher, but rather indicate how quite traditional structures and relations between teachers as active transmitters and students as passive receivers are maintained.

A clear example of when a task has a function in the collective co-constructed disengagement is when as part of an assessment task students are required to make oral presentations about different Swedish political parties’ opinions on aspects of the legal system. Prior to the examination, the teacher instructs the students on how to make a good presentation and talks about the importance of connecting with the audience. Students are told to face the audience, make eye contact and deliver the presentation in a clear and engaging manner. The students in the audience are not asked to provide feedback or assess their peers, but are simply asked to pay attention and concentrate on the presentations. During the presentations, there is almost no sign of any substantial engagement on the part of the audience. Most of the students find it difficult to stay focused and repeatedly check their mobile phones, talk to the student next to them or simply sit still through the lesson. This is a clear example of when the task, the subject content and the educational situation with an assessed presentation collectively co-construct (dis)engagement and where students as some-body thus become disengaged. Finally, on several occasions, the students work with tasks with which they (or rather, their interest and/or subject knowledge) do not seem to connect. This is visible in how the students interact in verbal and non-verbal communication in relation to the task at hand. This is particularly obvious in lessons when students say out loud that the task is hard or boring, or that he/she does not understand what is to be done. Some of the students either turn towards each other and start chatting or chat with their teacher. In several of the lessons students repeatedly check their mobile phones and some even lie on a bench with their earphones plugged in. The function of the task is that students end up being disconnected disengaged, distanced and uninvolved, and as a result show signs of fatigue or distraction.

In conclusion: disengaged encounters are when students are not engaged in the doing of social studies and when the content, the assignment and the pedagogy used does not involve encountering the undetermined. This does not imply that teacher directed lessons or oral presentations are disengaging per se, but that in our data the functional coordination with the practice can be illustrated in these practices. In the data, this theme does not include any disruptive moments so the transformative potential is less obvious even if of course transformation could happen. However, this is not to say that students are disengaged, disconnected or disaffected by their school experience or indeed that they don’t learn anything, but instead that in the functional coordination with practice they are made disengaged in transaction with others (other students, the teacher) and the environment (classroom materiality, tasks or subject content). In effect, it becomes a collective co-constructed disengagement. In this sense, the theme offers a complex view of engagement and disengagement by implicating the materiality of the learning space and the networking of the objects involved in the transaction rather than implicating the student or indeed the teacher.

5.2. Screened encounters

Within this theme, students as some-body come into being as screened. Here, the functional coordination of the embodied engagement involves the clear function of technology in the classroom. The category consists of how students interact more with and through screens than they do face-to-face. The term “screen” can refer to showing or checking something/somebody, hiding and protecting something/somebody by placing something in front of or around them, as well as blocking someone’s vision or movement. The fact that the term may have different or double meanings emphasises the complex ambiguity of the screen/body relationality and what students as some-body do and become in a transaction with the screen. They become screened from each other and the content while at the same time these encounters open up for other forms of experiences and potential relations. They are accordingly screened from embodied educative experiences and in this sense, the screened encounters potentially become miseducative (cf. Dewey, Citation1938b).

Screened communication is used as a generic term for events during the lessons when the students interact by communicating, gesturing and/or moving (their bodies) with and around a screen as the focal point for their embodied actions. Actions are, for example, working with their computers or laptops, watching or presenting power-point presentations on a white screen, or using their mobile phones during class. Two situations are used to illustrate screened encounters, namely oral presentations and small group activities.

Despite the teacher’s instructions, when students make their oral presentations they often turn towards and completely focus on the screen and not on their audience. The screen/body relation and not the relation between individuals is thus what is in focus in the event, both for the presenter and the audience. On these occasions, the screen blocks face-to-face encounters in that the presenters’ attention, as can be seen in Figure , is totally focused on the computer screen or the power-point presentation on a white screen thus creating a relation to the screen and the content of the presentation rather than in an embodied sense to those presented to. The embodied, screened relation also applies to the audience, who in turn face the white screen and not the presenter(s). Rarely do the presenter(s) and the audience turn towards each other and, in this sense, the materiality of the screen has the collective function of “blocking somebody’s vision”. As mentioned in the theme disengaged encounters, the students in the audience often look at their mobile phones during the presentations, thereby further screening the potential for pedagogical encounters. This relation has been described by Richardson (Citation2010) as an “incorporation of screens into our corporeal schemata” and it is as Richardson argues as if the screens “represent real people and real places” (p. 4).

During the small group activities, the students’ attention is often turned towards a laptop screen or the screens of their smart phones. As illustrated in Figure , students lean forward and position themselves to face the screen more directly. The materiality of the screen thus has the function of being something around the student that blocks any embodied engagement with other students. When the teacher joins the group, the materiality of the screen and the content displayed on the screen remain the centre of attention. This does not mean that communication breaks down, though. On the contrary, the communicative aspect is a key part of the functional coordination of screened encounters, but the space this communication occurs in is digital and screened rather than embodied. The students could just as well been in different rooms.

During the lessons, the screened communication functions as a kind of screen-body/face assemblage, which often challenges traditional notions about how presentations are made and how teacher-students interact. This communication is more in line with Richardson’s (Citation2010) indication of screens as young people’s window-to-the-world. What is made in common in the communication is thus that it is digital.

In conclusion: screened encounters are events in classroom practice when the materiality of the screen blocks face-to-face encounters and also serves as a “shield” or “bodyguard” in the encounter. Richardson (Citation2010) calls this routinely use of screens a corporeal and interfacial modality in public space that effects our different ways to be and become some-body. In some senses, the screens block face-to-face communication in the classroom and can in that sense restrict the educative potential of social studies, and accordingly be miseducative (Dewey, Citation1938b). However, on the other hand, as screens are incorporated into our lived experience of bodily space, where bodies, objects and environments both form and are formed by the other, the screen-body/face assemblage can also be said to create “disruptive moments” (Todd, Citation2014), in this case in the lessons. In this way the screens, as we can see in the next theme (see Figure ), have the potential not to screen, but to create liminal pedagogical and thus educative relationships in classroom practice.

5.3. Educative encounters

The theme educative encounters involve embodied engagements that we have identified as processes in which students as some-body more clearly are involved in relational embodied aspects of education with potential for further growth (Dewey, Citation1938b). These encounters involve an assemblage of embodied, cognitive and affective aspects of relationality and they entail unexpected and disruptive moments that in a different way than the other two themes offer new insights that therefore can potentially transform what students do and become in the classroom. However, it is not that teacher-led lessons, oral presentations from students or working with screens is not potentially educative. This is also part of how embodied engagement is manifested in classrooms, but what makes the situations used as illustrations in this theme educative is when we empirically can identify when the participants are involved in embodied pedagogical relations with potential for further growth (Dewey, Citation1938b).

Two situations, small group activities and oral presentations, are particularly illustrative for this theme, where students as some-body face the undetermined and thus stand at a threshold. In these encounters, the individual transacts with and through the environment, which is clearly visible in how the students interact as some-body in a process that occasions alteration and growth. The situations used for illustration take place in the same lessons as the previous categories, but with different events as illustration. This also shows that situations are intertwined and can change from disengaged or screened encounters to students’ active pedagogical involvement.

The first illustration is a small group activity in which students interact by listening, discussing and asking questions when working on an analysis of a real court case using the authentic court protocols (see Figure ). The court case concerns a doctor’s sexual abuse of several of his patients. The results and the direction of the students’ quite emotional interactions do not seem to be apparent beforehand. Their bodily postures, facial expressions and deliberations about the court case display an embodied presence and engagement with both the content and the task. The students become some-body by deliberating, communicating and engaging in the inquiry and they are not screened in any sense of the word. In the video recordings, it can sometimes be discerned that the ongoing process is not linear but unexpected and complex in relation to the task at hand. The students are in an embodied sense (cf Kazan, Citation2005) “feeling” and “finding” their way in the interaction. This interaction can be described as an embodied liminal space, which through its material and corporeal characteristics facilitates opportunities for alteration (cf. Todd, Citation2014). It is these aspects that constitutes this event as educative.

The teacher moves around the classroom and when he/she is asked by the group to explain something, and as seen in Figure , sits or bends down in order to be at the same level as the students, which seems to create a more communicative relationality between them. Being physically at the same level as the students also appears to make the interaction more personal in that students are more inclined to involve the teacher in the deliberation rather than just asking quick questions.

On some occasions during the previously illustrated oral presentations the students’ verbal and non-verbal actions appear to be undetermined and resemble what Garrison, Östman, and Håkansson (Citation2015) call educative moments. In this event, the students move from a disengaged and screened encounter to an educative encounter when the functional coordination of their (inter)actions open up the space between them and their audience.

As illustrated in Figure , one example is when one of the female students initially takes her hands out of her pockets during the presentation and begins to expressively wave them about to add emphasis to her main analytical points about a particular political party’s views on Swedish law. She uses open gestures that move away from the body and extend out to the audience in an effort to relate to the listeners. She also takes her eyes off the screen and starts to talk more freely without the script and highlights the questions and analytical points they have discovered, rather than just presenting the facts. Others in the group also take it in turns to speak, as if to confirm what has just been said. In this way the focal point shifts from the relation to the screen to the embodied relation between the presenting student, the content of the presentation and the audience. Through communicating, deliberating and making something in common the students in this event become present as some-body and thus making the event educative.

In conclusion: the two illustrations (see Figures and ) can be seen as aspects of an embodied engagement where students as some-body act in a liminal space in which communication and the indeterminacy of the event characterise the relation. This liminality of the pedagogical encounter is something that arises in what Dewey (Citation1938a) would call the indeterminate situation and, in the course of inquiry, out of transactions (p. 106). This is what Todd refers to as the embodied and transcendent aspects of becoming in relation or residing at a threshold where something educative is about to happen. According to Todd, this liminal moment opens up new ways of discussing classroom practices, relations to others (students and teacher) and the environment (e.g. classroom materiality, tasks, subject content) and highlight the embodied and transcendent aspects of becoming:

Thus, it is in relation to our material surroundings that we transcend the limits of ourselves. And this, I think, has something important to say to education, given the concrete realities of classroom life: the relationships to other bodies, other sensibilities, other ideas. What therefore remains to be explored more thoroughly here is precisely this relational, contextual aspect of becoming, and the ways in which metaphors of this liminal space of relationality might provide a more fulsome picture of the existential, transformative character of education (Todd, Citation2014, p. 239).

In a relational sense, transformation is occasioned by people and things that are part of a certain context and materiality. We accordingly contend that in this theme the students as some-body stand at the threshold of something that can potentially be transforming and that it is this that makes the engagement educative.

6. Discussion—social studies with the body in mind

We have argued that all educational situations include embodied interactions with the environment, and that if we do not take this aspect seriously, in research as well as in school, we risk having a limited view of what is taking place in the complexities of classroom practice. Based on Dewey’s view of embodied relationality in teaching and learning, and Todd´s argument that students and teachers always enter pedagogical encounters as some-body, the body is always engaged in education. In this sense, we build on previous research regarding embodied aspects of education in terms of the importance of including and emphasising embodied pedagogies (e.g. Bresler, Citation2013; Evans et al., Citation2009; Kazan, Citation2005; Shilling, Citation2016, Citation2017, Citation2018). What we add in our study is a way to explore and empirically show how embodied pedagogies is manifested in classroom practice.

In research on social studies, however, the body and embodied aspects of classrooms have been notably absent and when included often linked to a dualistic notion of mind/body. When it comes to how embodied engagement appear in terms of what bodies do and become in a social studies classroom, this article accordingly contributes to an understanding of what is going on in social studies classrooms by exploring how students become some-body in social studies in school. In this way, the existing knowledge is deepened by: (a) re-understanding social studies as embodied rather than dis-embodied, (b) naming aspects of social studies that have previously not been named and (c) exploring the educative potential of social studies as students enter classrooms as some-body.

In the analysis, the characteristics of three embodied engagements in a social studies classroom are identified as (i) disengaged encounters, (ii) screened encounters and (iii) educative encounters. At a first glance, the three comprehensive themes do not seem to be surprising. They fit quite nicely with research on embodied learning in teaching and in teacher education if we look at research from fields other than social studies where aspects of knowledge as embodied and what bodies become in educational situations have been prominent (Fleming et al., Citation2015; Pramling-Samuelsson & Asplund-Carlsson, Citation2008). They are also probably recognisable by many teachers in their daily practices. However, what makes in-depth insights possible is the theoretical analysis of the themes and also how the claims we make can continue Andersson et al. (Citation2018) repositioning of the body in teaching and learning in order to treat any educational situation as embodied rather than dis-embodied. It also extends Kazan’s (Citation2005) argument that teachers require a particular attention to embodiment in the classroom and that “as teachers, we enter classrooms with assumptions about our students; that reading bodies is a complicated task; but that reading these bodies is necessary for […] successful pedagogy” (p. 386).

6.1. The liminality of pedagogical encounters

In line with Kazan’s (Citation2005) argument regarding transformative pedagogies and how students embody pedagogical practices in everyday classrooms we, in this study, use the lens suggested by Todd (Citation2014) in order to further scrutinize the pedagogical potential of social studies when teaching and learning in the classroom is handled embodied. Todd’s ideas about the liminality of pedagogical relations are thus used as a metaphor for educational situations where there is a pedagogical potential of undeterminedness. These relations are always also embodied which we in the beginning of the paper argued are exactly what are lacking from research in social studies classrooms. So how can the liminal be understood in a social studies classroom setting? Phrased differently, what can teachers and students do and become? Todd (Citation2014) helps to take us further by arguing that the task is not to define or predict these aspects of relationality, but to bring them to attention, so that they can unfold in the classroom. For students and teachers alike, this means being receptive to embodied liminal opportunities for gaining new insights.

The results show concrete examples of this, for example, in oral presentations and in small group activities, where students as some-body seem to transgress from noneducative encounters or miseducative encounters to a much more active and educative embodied involvement. Students start to interact with the audience when they begin to reflect on and analyse the content. In other situations, the contrast of lying on a bench listening to music on the mobile phone through earplugs during a lesson, or interacting with classmates through embodied deliberation, demonstrate different kinds of engagement, and occasions different becomings.

However, it is important to note that we do not want to create a student versus teacher-centred dichotomy or that the use of the term disengaged sets up a teacher-centred pedagogy as “bad”. We believe that it is possible for students to be genuinely engaged whilst sitting still and listening, and that listening can be a highly active, fully engaged and embodied learning the encounter. And also, as stressed by Conroy (Citation2004), “in acting as a body, I am, consciously or unconsciously, embroiled in my own ambiguous relationship to this body that faces into and engages with the world” (p. 89). Same with being screened, where the screen can be immersive and suck everyone in so that no one is looking at each other but in an embodied sense highly engaged fixated on the screen. Engagement in an embodied sense is accordingly not only something that can be identified through observations so in our data, this aspect was something that was difficult to detect, whilst disengaged and screened encounters were more identifiable. We think that observational data combined with student interviews in direct connection with the observations can be a way around this.

So how might the results of this study inform the practices of teachers and teacher educators in social studies, or indeed other subject areas? The results show that some educational situations seem to have a greater pedagogical potential in terms of creating liminality. In order to understand this liminality, embodied engagement needs to be taken into consideration. However, this does not mean that the body always has to be observably active in these engagements. Students enter classrooms as some-body. They also become some-body in classroom practice and, in doing so, have the potential to cross the threshold to something new. We have shown how aspects of embodied engagement are manifested and what bodies do and become in a particular social science classroom. We have accordingly started to unpack and articulate what Todd (Citation2014) argues to be aspects of relations that are already taking place in classrooms but that we fail to name. The results are also in line with Wilcox’s (Citation2009) argument that students’ embodied engagement needs to be thoughtfully incorporated into the classroom. We agree that it seems a waste to “let students sit in the classroom, hoping that the state of their bodies does not reflect the state of their minds” (107).

It can be concluded that a potential for liminal and thus educative embodied encounters in teaching and learning in social studies classrooms is created if the subject content, the forms of education, the task, the materiality of the classroom, students’ previous experiences and the teaching all align as students engage in the educational situation as some-body. These encounters are educative in a way that goes beyond mere instruction and memorising. Based on our results in a social studies classroom, further important questions include: What does the activity do with the students? How do different forms of teaching change embodied engagements? How are liminal pedagogical encounters created? How is listening and watching embodied in liminal ways? This is about understanding embodied engagement as an important but often disregarded aspect of social studies education. If we fail to understand this, there is a risk that social studies will continue to be treated as dis-embodied. As has been argued in this article, this would mean that we have failed to fully understand and make use of the subject’s potential in both research and practice.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the feedback we received from the SMED (Studies of Meaning-making in Educational Discourses) research group and the anonymous reviewers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Louise Sund

The authors are members of the research group SMED (Studies of Meaning-Making in Educational Discourses), a cross-university research group in the field of didactics and educational science at Örebro University. They are all experienced schoolteachers, teacher educators, and researchers. Sund has an interest in environmental and sustainability education and global citizenship education. She currently investigates the challenges that teachers face when addressing global equity and justice issues in their classrooms. Quennerstedt’s and Öhman’s main area of research is within teaching and learning in physical education, and in health education. In their research, questions of health, body, gender, artefacts, subject content, learning processes and governing processes within educational practices has been prominent. They have published in Environmental Education Research, Journal of Moral Education, Sport, Education and Society, Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy and Gender and Education, among others, and they have run several research grant projects.

References

- Alibali, M. W., & Mitchell, J. N. (2012). Embodiment in mathematics teaching and learning: Evidence from learners’ and teachers’ gestures. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 21(2), 247–21. doi:10.1080/10508406.2011.611446

- Almqvist, J., & Quennerstedt, M. (2015). Is there (any)body in science education? Interchange, 46(4), 439–453. doi:10.1007/s10780-015-9264-4

- Andersson, J., Garrison, J., & Östman, L. (2018). Empirical philosophical investigations in education and embodied experience. The cultural and social foundations of education. Basel, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG.

- Anttila, E. (2015). Embodied learning in the arts. In S. Schonmann (Ed.), International yearbook for research in arts education: The wisdom of the many-key issues in arts education (pp. 372–377). New York: Waxmann.

- Armour, K., Quennerstedt, M., Chambers, F., & Makopoulou, K. (2017). What is ‘effective’ CPD for contemporary physical education teachers? A Deweyan framework. Sport, Education and Society, 22(7), 799–811. doi:10.1080/13573322.2015.1083000

- Bassey, M. O. (2010). Educating for the real world: An illustration of John Dewey’s principles of continuity and interaction. Educational Studies, 36(1), 13–20. doi:10.1080/03055690903148480

- Bickmore, K., & Parker, C. (2014). Constructive conflict talk in classrooms: Divergent approaches to addressing divergent perspectives. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42(3), 291–335. doi:10.1080/00933104.2014.901199

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2006). Beyond learning. Democratic education for a human future. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

- Biesta, G. J. J., & Burbules, N. (2003). Pragmatism and educational research. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Biesta, G. J. J., Field, J., Hodkinson, P., Macleod, F. J., & Goodson, I. F. (2011). Improving learning through the lifecourse. London: Routledge.

- Biesta, G. J. J., & Tedder, M. (2006). How is agency possible? Towards an ecological understanding of agency-as-achievement. Working Paper 5. Exeter: The Learning Lives Project.

- Bigger, S. (2009). Victor Turner, liminality, and cultural performance. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 30(2), 209–212. doi:10.1080/13617670903175238

- Björk-Willén, P., & Cromdal, J. (2009). When education seeps into ‘free play’: How preschool children accomplish multilingual education. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(8), 1493–1518. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2007.06.006

- Bresler, L. (Ed.). (2013). Knowing bodies, moving minds: Towards embodied teaching and learning. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Brooks, S. (2011). Historical empathy as perspective recognition and care in one secondary social studies classroom. Theory & Research in Social Education, 39(2), 166–202. doi:10.1080/00933104.2011.10473452

- Broom, C., & Murphy, S. (2015). Social studies from a holistic perspective: A theoretical and practical discussion. The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education, 5(1), 109–119.

- Clingerman, F. (2014). Pedagogy as a field guide to the ecology of the classroom. Teaching Theology & Religion, 17(3), 217–220. doi:10.1111/teth.2014.17.issue-3

- Conroy, J. C. (2004). Betwixt and between: The liminal imagination, education and democracy. New York: Peter Lang.

- De Freitas, E., & Sinclair, N. (2014). Mathematics and the body: Material entanglements in the classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1928). Body and mind. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 4(1), 3–19.

- Dewey, J. (1938a). Logic: The theory of inquiry. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), John Dewey: The later works (Vol. 12, pp. 1-797). Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Dewey, J. (1938b). Experience and education. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Eklöf, A. (2013). A long and winding path: Requirements for critical thinking in project work. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 2(2), 61–74. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2012.11.001

- Elbaz-Luwisch, F. (2004). How is education possible when there’s a body in the middle of the room? Curriculum Inquiry, 34(1), 9–27. doi:10.1111/j.1467-873X.2004.00278.x

- Ennis, C. D. (Ed.). (2016). Routledge handbook of physical education pedagogies. London: Routledge.

- Enriquez, G., Johnson, E., Kontovourki, S., & Mallozzi, C. A. (Eds.). (2016). Literacies, learning, and the body. Putting theory and research into pedagogical practice. New York: Routledge.

- Estola, E., & Elbaz-Luwisch, F. (2003). Teaching bodies at work. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(6), 697–719. doi:10.1080/0022027032000129523

- Evans, J., Davies, B., & Rich, E. (2009). The body made flesh: Embodied learning and the corporeal device. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 30(4), 391–406. doi:10.1080/01425690902954588

- Fleming, M., Bresler, L., & O’Toole, J. (Eds.). (2015). The routledge international handbook of the arts and education. London: Routledge.

- Garrison, J., Östman, L., & Håkansson, M. (2015). The creative use of companion values in environmental education and education for sustainable development: Exploring the educative moment. Environmental Education Research, 21(2), 183–204. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.936157

- Garrison, J. W., & Rud, A. G., Jr. (Eds.). (1995). The educational conversation: closing the gap. Albany, New York: SUNY Press.

- Gibbs, B., Quennerstedt, M., & Larsson, H. (2017). Teaching dance in physical education using exergames. European Physical Education Review, 23(2), 237–256. doi:10.1177/1356336X16645611

- Gilbert, J. (2013). The Pedagogy of the body: Affect and collective individuation in the classroom and on the dancefloor. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(6), 681–692. doi:10.1080/00131857.2012.723890

- Gore, J. M. (2001). Disciplining bodies: On the continuity of power relations in pedagogy. In C. Peachter, R. Edwards, R. Harrison, & P. Twining (Eds.), Learning, space and identity (pp. 167–181). London: Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd.

- Hager, P., Lee, A., & Reich, A. (Eds.). (2012). Practice, learning and change: Practice-theory perspectives on professional learning. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hess, D. (2002). Discussing controversial public issues in secondary social studies classrooms: Learning from skilled teachers. Theory & Research in Social Education, 30(1), 10–41. doi:10.1080/00933104.2002.10473177

- Hildreth, R. W. (2011). What good is growth? Reconsidering Dewey on the ends of education. Education and Culture: the Journal of the John Dewey Society, 27(2), 28–47. doi:10.1353/eac.2011.0012

- Hodkinson, P., Biesta, G. J. J., & James, D. (2007). Understanding learning cultures. Educational Review, 59(4), 415–427. doi:10.1080/00131910701619316

- Horn, J., & Wilburn, D. (2005). The embodiment of learning. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 37(5), 745–760. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2005.00154.x

- Howes, E. V. (2008). Educative experiences and early childhood science education: A Deweyan perspective on learning to observe. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(3), 536–549. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.03.006

- Johl, S. K., & Renganathan, S. (2010). Strategies for gaining access in doing fieldwork: Reflection of two researchers. Electronic Journal on Business Research Methods, 8(1), 42–50.

- Johnson, E., & Vasudevan, L. (2012). Seeing and hearing students’ lived and embodied critical literacy practices. Theory into Practice, 51(1), 34–41. doi:10.1080/00405841.2012.636333

- Kazan, T. S. (2005). Dancing bodies in the classroom: Moving toward an embodied pedagogy. Pedagogy, 5(3), 379–408. doi:10.1215/15314200-5-3-379

- Kelan, E. (2010). Moving bodies and minds - the quest for embodiment in teaching and learning. Higher Education Research Network Journal, King’s Learning Institute, King’s College London 3, 39–46.

- King, J. T. (2009). Teaching and learning about controversial issues: Lessons from Northern Ireland. Theory & Research in Social Education, 37(2), 215–246. doi:10.1080/00933104.2009.10473395

- Klaar, S., & Öhman, J. (2012). Action with friction: A transactional approach to toddlers’ physical meaning making of natural phenomena and processes in preschool. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 20(3), 439–454. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2012.704765

- Klaar, S., & Öhman, J. (2014). Doing, knowing, caring and feeling: Exploring relations between nature-oriented teaching and preschool children’s learning. International Journal of Early Years Education, 22(1), 37–58. doi:10.1080/09669760.2013.809655

- Larsson, H., & Quennerstedt, M. (2012). Understanding movement: A sociocultural approach to exploring moving humans. Quest, 64(4), 283–298. doi:10.1080/00336297.2012.706884

- Laurilla, J. (1997). Promoting research access and informant rapport in corporate settings: Notes from research on a crisis company. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 13(4), 407–418. doi:10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00026-2

- Macintyre Latta, M., & Buck, G. (2008). Enfleshing embodiment: ‘Falling into trust’ with the body’s role in teaching and learning. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 40(2), 315–329. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00333.x

- Mark, M., & Madura, P. (2013). Contemporary music education. Boston, MA: Schirmer Cengage Learning.

- Martlew, J., Stephen, C., & Ellis, J. (2011). Play in the primary school classroom? The experience of teachers supporting children’s learning through a new pedagogy. Early Years, 31(1), 71–83. doi:10.1080/09575146.2010.529425

- Nokes, J. (2014). Preparing novice history teachers to meet students’ literacy needs. Reading Psychology, 31(6), 493–523. doi:10.1080/02702710903054923

- O’Loughlin, M. (2013). Hager and embodied practice in postmodernity: A tribute. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(12), 1219–1229. doi:10.1080/00131857.2013.763591

- Ord, K., & Nuttall, J. (2016). Bodies of knowledge: The concept of embodiment as an alternative to theory/practice debates in the preparation of teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 355–362. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.019

- Ozolins, J. (2013). The body and the place of physical activity in education: Some classical perspectives. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 45(9), 892–907. doi:10.1080/00131857.2013.785356

- Potter, J. (2002). Two kinds of natural. Discourse Studies, 4(4), 539–542. doi:10.1177/14614456020040040901

- Pramling-Samuelsson, I., & Asplund-Carlsson, M. (2008). The playing learning child: Towards a pedagogy of early childhood. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 52(6), 623–641. doi:10.1080/00313830802497265

- Prawat, R. S. (1999). Cognitive theory at the crossroads: Head fitting, head splitting, or somewhere in between? Human Development, 42, 59–77. doi:10.1159/000022611

- Quennerstedt, M., & Maivorsdotter, N. (2016). The role of learning theory in learning to teach. In C. D. Ennis (Ed.), Routledge handbook of physical education pedagogies (pp. 417–427). London: Routledge.

- Quennerstedt, M., Öhman, J., & Öhman, M. (2011). Investigating learning in physical education – A transactional approach. Sport, Education and Society, 16(2), 159–177. doi:10.1080/13573322.2011.540423

- Radford, L. (2009). Why do gestures matter? Sensuous cognition and the palpability of mathematical meanings. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 70(2), 111–126. doi:10.1007/s10649-008-9127-3

- Richardson, I. (2010). Faces, interfaces, screens: Relational ontologies of framing, attention and distraction. Transformations: Journal of Media and Culture, 2010(18), 1–15.

- Savenije, G. M., Van Boxtel, C., & Grever, M. (2014). Sensitive ‘heritage’ of slavery in a multicultural classroom: Pupils’ ideas regarding significance. British Journal of Educational Studies, 62(2), 127–148. doi:10.1080/00071005.2014.910292

- Scott Webster, R. (2017). Valuing and desiring purposes of education to transcend miseducative measurement practices. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(4), 331–346. doi:10.1080/00131857.2015.1052355

- Shilling, C. (1991). Educating the Body: Physical Capital and the Production of Social Inequalities. Sociology, 25(4), 653–672. doi:10.1177/0038038591025004006

- Shilling, C. (1992). Schooling and the production of physical capital. Discourse: Australian Journal of Educational Studies, 13(1), 1–19.

- Shilling, C. (2004). Physical capital and situated action: A new direction for corporeal sociology. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 25(4), 473–487. doi:10.1080/0142569042000236961

- Shilling, C. (2007). Sociology and the body: Classical traditions and new agendas. The Sociological Review, 55(1_suppl), 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00689.x

- Shilling, C. (2016). The rise of body studies and the embodiment of society: A review of the field. Horizons in Humanities and Social Sciences: an International Refereed Journal, 2(1), 1–14.

- Shilling, C. (2017). Body pedagogics: Embodiment, cognition and cultural transmission. Sociology, 51, 1205–1221. doi:10.1177/0038038516641868

- Shilling, C. (2018). Embodying Culture: Body pedagogics, situated encounters and empirical research. The Sociological Review, 66, 75–90. doi:10.1177/0038026117716630

- Stirrup, J., Evans, J., & Davies, B. (2017). Early years learning, play pedagogy and social class. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38(6), 872-886.

- Stolz, S. A. (2015). Embodied learning. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(5), 474–487. doi:10.1080/00131857.2013.879694

- Sullivan, S. (2002). Pragmatist feminism as ecological ontology: Reflections on. Living across and through Skins. Hypatia, 17(4), 201–217.

- Thorburn, M., & Stolz, S. (2015). Embodied learning and school-based physical culture: Implications for professionalism and practice in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 22(6), 721–731. doi:10.1080/13573322.2015.1063993

- Todd, S. (2014). Between body and spirit: The liminality of pedagogical relationships. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 48(2), 231–245. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.12065