Abstract

In the area of foreign languages, it is necessary to develop the digital competence of future teachers in order to improve the teaching-learning process that they will carry out with their students. However, different intrinsic variables of teachers can influence their use of information and communication technologies (ICT). The main objective of this study is to analyse the use of ICT by future primary education teachers. The secondary objective is to find out whether age, gender and motivation affect their use of ICT. Non-experimental research has been carried out with a sample of 134 future teachers, specifically those teaching foreign languages. The results show that the future teachers of foreign languages have a pedagogical digital competence in the use of medium-low ICT, their most used technological devices being laptops and projectors. Moreover, they do not use Web 2.0 tools when teaching languages. Regarding gender, it can be seen that there are no significant differences, while the age variable does influence the level of pedagogical digital competence. In addition, it has been confirmed that motivation constitutes an essential variable at the pedagogical digital competence level, both in terms of the use of technological devices, as well as the use of Web 2.0 tools and of Learning Management Systems.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Despite the large number of researches on the digital competence of the teacher, few studies have focused on knowing the use they make specifically of Web 2.0 tools in the area of foreign language. This study investigates the level of use that teachers make of Web 2.0 tools and web resources in the area of foreign language. It was revealed that teachers of foreign languages have a level of digital competence medium-low whose most used technological devices being laptops and projectors. In addition, the results showed that there are no differences in the level of digital competence according to the gender of the teachers, however, age and motivation influences their level of competence.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interest

1. Introduction

Times have changed, and, with them, so has education. In the last few decades, new methodologies have been introduced in this field to help meet the requirements of new educational systems. Current information and communication technologies (hereinafter, ICT) have made it possible to work with and analyse large amounts of data and to disseminate the results via digital media. With regards to education, ICT need to include a methodological component in order to impact students learning significantly (Blau & Shamir-Inbal, Citation2017; Koh, Chai, Benjamin, & Hong, Citation2015; Shyshkina, Citation2018).

The use of these methodological and innovative changes should be explored in all areas, but might be of particular benefit in the field of foreign language learning, as ICT appears to be a suitable way to improve students’ learning and knowledge acquisition in this field (Barr, Citation2016; Kori, Pedaste, Leijen, & Tõnisson, Citation2016; Naqvi, Citation2017; Sampaio & Almeida, Citation2016). Altun (Citation2015) suggests that the integration of technology into the process of teaching and learning foreign languages leads to increased motivation and, therefore, to a more efficient achievement of learning goals. Hence, in order to enhance the quality of education, it is essential for foreign language teachers to have a wide range of competencies and to be able to put them to use in the classroom to meet students’ needs (Instefjord & Munthe, Citation2017; Proshkin, Glushak, & Mazur, Citation2018; Tondeur et al., Citation2017).

Thus, teachers are required to use ICT for pedagogical and educational purposes. Nonetheless, studies have revealed that the level of digital pedagogical competence shown by teachers is lower than expected (Guillén-Gámez, Mayorga-Fernández, & Álvarez-García, Citation2018; Pinto-Llorente, Sánchez-Gómez, García-Peñalvo, & Casillas-Martín, Citation2017; Sadaf, Newby, & Ertmer, Citation2016; Salomaa, Palsa, & Malinen, Citation2017; Siddiq, Scherer, & Tondeur, Citation2016).

Although several authors state that variables such as gender (Cuhadar, Citation2018; Lin, Duh, Li, Wang, & Tsai, Citation2013; Tondeur, Van de Velde, Vermeersch, & Van Houtte, Citation2016), age (Cabero & Barroso, Citation2016; Gudmundsdottir and Hatlevick, Citation2018; John, Citation2015; Scherer, Siddiq, & Teo, Citation2015) and motivation; can affect pre-service teachers’ pedagogical digital competence, no consensus has yet been reached regarding these variables. Nevertheless, all previous research literature seems to be in agreement that motivation plays an essential role in the use of ICT in educational settings (Altun, Citation2015; Blackwell, Lauricella, Wartella, Robb, & Schomburg, Citation2013; Hsu, Tsai, Chang, & Liang, Citation2017; Naqvi, Citation2017; Tømte, Enochsson, Buskqvist, & Kårstein, Citation2015).

In light of this, the purpose of this study is to analyse foreign language pre-service teachers’ pedagogical digital competence by exploring one of the most important subdimensions of this competence: the use of Web 2.0 tools in the context of education. Furthermore, different variables (gender, age and motivation) have been analysed under the assumption that they may influence how pre-service teachers’ use these tools.

2. Related works

2.1. Approach to the concept of pedagogical digital competence

The concept of digital competence, as one of the seven key competencies specified by Ferrari (Citation2013), must be examined first to provide context for this study. Scholars and researchers have not yet reached a unanimous consensus regarding digital competence. In fact, a wide variety of terms are found in the literature just to refer to the concept of digital competence, such as digital literacy (Sefton-Green et al., Citation2016; Hartley, Citation2017) or digital skills (Damodaran & Burrows, Citation2017; Van Deursen & Van Djik, Citation2014). Digital competence could be roughly defined as the capacity to use ICT maintaining up-to-date knowledge of them. Several studies describe what pedagogical digital competence should encompass. Erstad (Citation2010) and Van Dijk (Citation2015) remark on the idea that digital competence should incorporate a creative component, and students are presumed to be able to learn by means of technology. According to Ottestad, Kelentrić, and Guðmundsdóttir (Citation2014), digital competence would enable the teacher to promote the students’ digital skills by working with academic material at the same time. Hence, an approach to digital competence literacy in pedagogical contexts is necessary in order to provide students with effective skills.

Pedagogical digital competence is defined as the ability to carry out and improve the teaching process using technology (From, Citation2017). Krumsvik (Citation2014), who has made relevant contributions to the area of digital competence in Norway, believes that there is a great difference between what the digital competence of teachers should be compared to that of other technology users. The author states that, for teachers, pedagogical digital competence involves their individual proficiency in using ICT alongside their pedagogical training and awareness of learning strategies.

2.2. Pedagogical digital competence in foreign language teaching

It is not hard to find studies focusing on the use of a certain digital tool to transform and improve foreign language teaching, such as digital storytelling (Castaneda, Citation2013), computer-assisted language learning (CALL) (Evans, Citation2009) or task-based language learning in digital environments (Seedhouse, Citation2017). However, there are very few studies that focus specifically on foreign language pre-service teachers’ pedagogical digital competence. O’Dowd (Citation2013, Citation2015), for instance, considered the competences of telecollaborative teachers. Blake’s (Citation2013) focus was on a better and more efficient use of technology to enrich foreign language learning by providing contact with the target language. At a teacher education programme in Norway, Røkenes and Krumsvik (Citation2016) examined how four groups of postgraduate pre-service teachers used information and communication technologies to teach English as a foreign language in secondary schools. They found differences among students in their mastery of ICT -supported teaching of English as a foreign language. Pinto-Llorente et al. (Citation2017) carried out a study based on a sample of 358 pre-service teachers in the framework of blended learning teaching of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in primary education. Their aim was to find out what their perception was regarding the use of ICT to teach English grammar. They arrived at the conclusion that, although most pre-service teachers claimed that they had not used information and communication technologies before, they regarded its use as positive, emphasising its advantages in blended learning to improve the teaching of grammar. Bucur and Popa (Citation2017), based on a sample of 135 Romanian university students of English as a foreign language, concluded that future English teachers in Romania should pay special attention to the practical problems associated with combining digital skills with specific strategies for foreign language learning. Tømte et al. (Citation2015), in their survey of 61 pre-service teachers, concluded that languages were especially suitable to be taught online.

2.3. Pedagogical digital competence according to gender, age and motivation

Different pre-service teacher-related variables influence their approach to ICT as a potential way to improve teaching. Some studies state that gender, age and motivation have a significant impact on pedagogical digital competence. Tondeur et al. (Citation2016), for instance, using a sample of 1138 university students from Belgium, found that there were, indeed, gender-related differences, and stated that, in general terms, women’s attitudes towards ICT are not as positive as those of men. On the same note, Balta and Duran (Citation2015) indicated that, while male teachers show higher levels of digital competence, their female peers are more likely to integrate ICT into their teaching practice. In this vein, Lin et al. (Citation2013) concluded that female pre-service teachers are more confident in their pedagogical digital knowledge, but less so in their personal digital competence compared to men. Cuhadar (Citation2018), in his study of a sample of 832 pre-service teachers attending teacher education programmes in Turkey, discovered that males perceived the level of ICT training and support received during their university education was higher than that perceived by females. Similar studies agree with this gender-based difference in the use of information and communication technologies in teacher education (Akbulut, Odabasi, & Kuzu, Citation2011). On the other hand, a number of studies on pre-service teachers’ inclusion and emphasis on the use of ICT did not find any significant differences in this regard (Antonietti & Giorgetti, Citation2006; Sang, Valcke, Van Braak, & Tondeur, Citation2010; Siddiq et al., Citation2016).

In relation to age, researchers arrived at differing conclusions. For example, Cabero and Barroso (Citation2016) state that the ICT skills of younger teachers are better than those of their older counterparts. Gudmundsdottir and Hatlevik (Citation2018), after testing 356 Norwegian newly qualified pre-service teachers, attest that those who had graduated recently tended to be more confident about integrating ICT into the learning process. On the other hand, researchers such as John (Citation2015), when analysing pre-service teachers’ attitude towards ICT and its implementation in the classroom, discovered that the 30 to 50 age group had a more positive attitude towards its inclusion in the teaching process compared to the under-30 and over-50 groups. Similarly, Siddiq et al. (Citation2016) concluded that, even though older teachers believe that they are less competent in the use of technology, they are aware of its usefulness in the teaching process. Nonetheless, in contrast, several studies show a negative correlation between age and pre-service teachers’ attitude towards ICT (O’bannon & Thomas, Citation2014; Siddiq et al., Citation2016; Vanderlinde, Aesaert, & Van Braak, Citation2014).

Pre-service teachers in the twenty-first century use ICT not only to convey information, but also to motivate students in their academic activities so that they can successfully accomplish their goals. The attitudes of both teachers and students towards ICT are crucial. Thus, Tømte et al. (Citation2015), in their study based on 61 pre-service teachers, concluded that attitude is essential: willingness and motivation are key elements for pre-service teachers to succeed in using ICT in the classroom. Motivated teachers manage to integrate ICT into their lessons because of their belief in their usefulness in the learning process (Blackwell et al., Citation2013; Sang, Valcke, Van Braak, Tondeur, & Zhu, Citation2011). Similarly, in their conclusions on the analysis of 316 participants, Hsu et al. (Citation2017) stressed the importance of pre-service teachers’ trust, motivation and confidence in their own teaching behaviour.

Within the area of technology, most existing studies focus on the most popular Web 2.0 tools from the perspective of the wider group of pre-service teachers, and not specifically dealing with foreign language learning. Indeed, they do not carry out in-depth analyses regarding future foreign language pre-service teachers’ pedagogical digital competence and the use of Web 2.0 tools in foreign language education. The previously mentioned literature shows a lack of consensus in relation to the results obtained on the issues of gender and age, leading us to the conclusion that further studies in this field of knowledge are required.

3. Method

3.1. Design

A non-experimental, ex-post-facto design has been used (Simon & Goes, Citation2013) in which none of the variables employed have been modified, only the information that was necessary to answer the research questions that have been compiled:

How frequently do foreign language teachers use ICT?

Do variables, such as age, gender and motivation, affect their level of use in their teaching practice?

A descriptive analysis, followed by an inferential analysis, has been carried out. The correlations between variables have been investigated using Spearman to ensure ordinal variables (Norman, Citation2010).

3.2. Participants

The sample is intentionally of a non-probabilistic nature (Bisquerra, Citation2004; Kerlinger, Howard, Pineda, & Mora Magaña, Citation2002). It is composed of 134 Primary Education students from the Faculty of Education at the Pontifical University of Salamanca (UPSA) who are studying Foreign Languages during the 2017–2018 academic year. All of these students (the future primary education teachers) are undertaking, at least, a second university degree, so they are all already teachers of other subjects. The predominant gender of participants is female, with males forming the minority (37.3%). Regarding age, the majority age range is 26–30 years old (28.4%), followed by 31–35 years old (22.4%), 36–40 years old (17.2%), less than 25 years old (16.4%) and older than 40 (15.7%).

3.3. Procedure

The data collection was carried out using Google Forms. This data was treated at a later stage in the statistical program SPSS V.22. In the first instance, students received an email with the relevant link explaining the details of the study and the corresponding survey, asking for their consent to participate, as well as guaranteeing the anonymity of the treatment of the surveys carried out.

3.4. Procedure, statistical and psychometric analysis

The process of design and validation of the instrument was developed following the indications proposed by Carretero-Dios and Pérez (Citation2005). The analysis of the data was done using the statistical programs IBM SPSS v22, AMOS Graphics v22.

3.5. Initial creation of the instrument

The researchers conducted eight meetings of 20 hours in total to justify the creation of the instrument and define what to evaluate, to whom and for what purpose, in order to conceptually delimit the scale to be built. Each researcher defined the construct operationally after a thorough literature review on digital competence and made a proposal of items combining the relevant aspects of the theoretical dimensions. The items were written in precise and appropriate language for the pre-service teachers.

3.6. Dimensions of the instrument

An instrument was developed to measure foreign language teachers’ level of ICT use. The first section included demographic and academic variables, such as gender, age and perception of the motivation level of their teaching practice. Next, the instrument was composed of four dimensions. The first dimension focused on technological devices, including four items (maximum 20 points); the second dimension focused on 2.0 tools, including nine items (maximum 45 points); the third dimension was related to learning management systems (LMS), including five items (maximum 25 points); and the fourth dimension focused on 2.0 tools and specific foreign language apps, including six items (30 points). 24 items in total made up the instrument, and a Likert scale with five points of valuation was used, where value one represented “no use” and value 5 represented “daily/habitually” (maximum 120 points).

3.7. Content validity

Initially, three rounds of evaluation were carried out by experts. In the first one, the construct and the dimensions were evaluated. In the second and third ones, the items were assessed (adequacy and relevance to the dimension and adequacy and wording). Subsequently, the dimensions or items with ratings that had less than 50% agreement among experts were eliminated.

3.8. Construct validity

An exploratory factorial analysis (EFA) was carried out through the analysis of the main axis with oblimin rotation. The results obtained with the sample adequacy index (KMO) was 0.740, and the Bartlet sphericity test was significant (sig = 0.000), indicating that the correlation matrix exceeded the conditions for carrying out this analysis. After the analysis, it was decided to group the items with the greatest factorial load in each factor, despite the fact that they also saturate in other factors with lower values. Likewise, values lower than 0.30 were eliminated from the matrix (Field, Citation2009). It has been found that the four resulting factors explain 47.59% of the total variance.

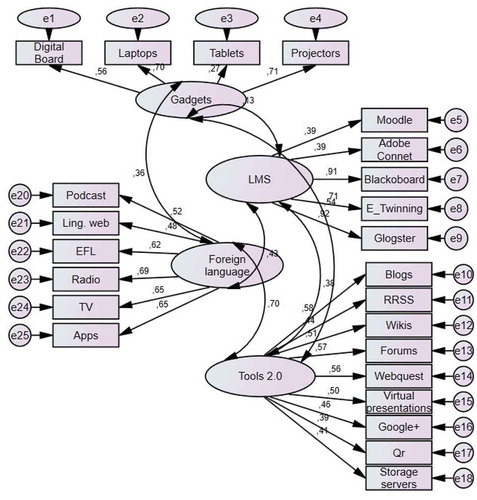

Following with the validity of the instrument, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out. Several indices have been considered recommended by Brown (Citation2014): value for the statistical adjustment minimum discrepancy/degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF, 1.83); incremental adjustment index (IFI, 0.79); comparative adjustment index (CFI, 0.79); and the mean square root of the approach error (RMSEA, 0.07). Also, it is a good model fit which would provide a significant result at a 0.05 threshold (Barrett, Citation2007). The structure of the confirmatory factor analysis is available in the annex of the article. In addition, it has been observed that the correlations between the different latent factors are significant (technological devices and learning management systems, r = 0.133; technological devices and Web 2.0 tools, r = 0.539); technological devices and Web 2.0 tools in a foreign language, r = 0.358; learning management systems and Web 2.0 tools, r = 0.382; Web 2.0 tools in foreign language and learning management systems, r = 0.435; and Web 2.0 tools in foreign language and Web 2.0 tools, r = 0.700).

3.9. Reliability analysis

In addition, the psychometric properties of the instrument were analysed to assess the reliability of the test. Its reliability was tested using internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) where the parameters obtained were: α = 0.86 (instrument total), α = 0.61 (technological devices), α = 0.75 (virtual learning platforms), α = 0.74 (Web 2.0 tools) and α = 0.78 (Web 2.0 tools focused on English).

4. Results

Each of the following tables show the descriptive parameters obtained in each of the dimensions that make up the instrument, including the mean (M), typical deviation (TD), the correlation between teacher motivation in their teaching practice and their level of use of ICT; the correlation between the age of the teaching staff and their level of use of ICT; and, finally, the difference of means in the level of use of ICT according to gender. This was carried out to find out whether there were any statistically significant differences.

It can be observed from Table that the pedagogical digital competence in Web 2.0 tools is medium-high (M = 14.55), being similar for both genders. Specifically, teachers perceive that their use of laptops has a higher pedagogical digital competence level (M = 3.99), followed by projectors (M = 3.88), with digital tablets being the least used (M = 2.82). Regarding gender, no significant differences were found in this Web 2.0 tools dimension (sig 0.469). In terms of how motivation affects pedagogical digital competence, it can be observed that there is a significant effect in both genders’ use of 2.0 tools with a moderate correlation (r = 0.404); that is to say, the coefficient of determination (R2) determines that the motivation variable represents 16.3% of the variability of the pedagogical digital competence (R2 = 0.163). With respect to age, the effect is small, although it is significant (r = —0.187), determining 3.50% of the variability in the pedagogical digital competence (R2 = 0.035).

Table 1. Results in the pedagogical digital competence of teachers in the technological devices dimension.

Regarding the use of Web 2.0 tools dimension, it can be seen in the Table that the pedagogical digital competence of teachers is medium-low (M = 19.79), and is very similar in both genders. Specifically, virtual presentations are the most used (M = 3.34), followed by storage servers (M = 2.81) and blogs (M = 2.46). Regarding gender, there are no significant differences (sig 0.630). In terms of how motivation affects the pedagogical digital competence, it can be observed that there is a significant effect on both genders’ use of Web 2.0 tools, with a high correlation (r = 0.595); that is to say, it represents 35% of the variance of the pedagogical digital competence (R2 = 0.354). Regarding age, it can be observed that it is also negatively correlated with the level of use of Web 2.0 tools (r = —0.292), mainly for females (r = —0.324), representing 11% of the variance of the pedagogical digital competence.

Table 2. Results in the pedagogical digital competence of teachers in the tools dimension 2.0.

Regarding the use of the learning management systems in the Table , the pedagogical digital competence of the teaching staff is very low (M = 7.78). This is very similar in both genders, with respect to the 25 maximum points to be obtained in this dimension. Specifically, the Moodle platform is the most used by teachers of both genders on a daily basis (M = 1.99), followed by Adobe-Connect (1.63) and Blackboard (M = 1.37), although they represent fairly low values on the 5-point Likert scale. Regarding how motivation affects pedagogical digital competence, it can be observed that there is a significant effect on both genders’ use of the learning management systems, with a moderate correlation (r = 0.355); that is to say, motivation represents 13% (R2 = 0.126) of the variability of the pedagogical digital competence. Regarding age, it can be observed that it is also negatively correlated with the use of learning management systems (r = —0.327); that is to say, age represents 11% (R2 = 0.107) of the variability of the pedagogical digital competence. In terms of gender, it can be seen that there are only statistically significant differences in the use of Adobe Connect (sig 0.013). The effect size (η) has been analysed through the alternative formula proposed by Rosenthal (Citation1994), since Cohen (d) could not be used due to the general assumptions that said formula was violated. The effect size in Adobe Connect is low-moderate (η = 0.374), determining the existing difference: 37% of the variance in this module is explained by gender.

Table 3. Results in the pedagogical digital competence of teachers in the learning management systems dimension

Regarding the use of Web 2.0 tools and mobile applications in the area of foreign languages, Table shows how the total pedagogical digital competence level of teachers is medium (M = 14.30). Specifically, linguistic consultation web pages are the most used by teachers (M = 3.58), followed by web pages for language learning (M = 3.22). Regarding gender, no significant statistical differences were found (sig 0.507). In terms of how motivation affects the pedagogical digital competence in this dimension, it can be observed that there is a significant effect on both genders’ use of these Web 2.0 tools, with a moderate correlation (r = 0.449); that is to say, the level of motivation represents 20% (R2 = 0.0.201) of the variability of the pedagogical digital competence. Regarding age, it can be observed that it is also negatively correlated with the use of these Web 2.0 tools (r = —0.123). In this case, age represents 1.5% (R2 = 0.015) of the variability of the pedagogical digital competence.

Table 4. Results in the pedagogical digital competence of teachers in the dimension tools in the area of foreign languages

In addition to this, an Analysis of the Variance (ANOVA) was carried out from the pedagogical digital competence dependent variable, taking into account the three independent variables studied in this research (gender, age, level of motivation in their teaching practice). Levene determined that the variance of the error in the dependent variable was not equal between the groups (sig 0.001) and, therefore, a contrast was used by Bonferroni. The silver model was significant, in which these three variables explain 50.3% of the variance of the pedagogical digital competence of the foreign language teaching staff (F, 4.336, sig 0.000, effect size η = 0.652). In addition, taking into account the total of the instrument, including the four dimensions (maximum 120 points), the teaching staff has a medium-low ICT level of use (M = 56.17, DT = 11.52).

5. Discussion

After observing the results and responding to the first research question, it is clear that the future foreign language teachers who participated in this study have a pedagogical digital competence in the use of medium-low ICT, which corroborates the results obtained by Sadaf et al. (Citation2016), Siddiq et al. (Citation2016) and Pinto-Llorente et al. (Citation2017), since said teachers continue to have a digital pedagogical competence lower than expected. In this sense, the results of Salomaa et al. (Citation2017) continue to be confirmed due to the fact that, currently, future teachers still do not receive solid initial training in regards to the development of pedagogical digital competence.

In this work, it has been verified that the technological devices mainly used by future teachers are laptops and projectors. They do not tend to use Web 2.0 tools for teaching languages, which has also been pointed out in studies by Hsu et al. (Citation2017) and Naqvi (Citation2017). This situation suggests that future teachers continue to use these devices as tools for teaching without taking advantage of their true pedagogical potential, as stated by Tømte et al. (Citation2015) and Altun (Citation2015). This study confirms this, as there was a low level of pedagogical digital competence in the use of virtual platforms for teaching.

Regarding gender, it can be observed that there are no significant differences in the level of pedagogical digital competence with respect to technological devices, nor in the use of Web 2.0 tools. These results are confirmed by the studies of Antonietti and Griorgetti (Citation2006), Sang et al. (Citation2010) and Sidding, Scherer and Tondeur (Citation2016). Nonetheless, there are some differences with respect to gender in the level of pedagogical digital competence in the use of learning management systems, with women using the Adobe Connect platform to a lesser extent.

This study has demonstrated that age is a variable that influences the level of pedagogical digital competence. Regarding the use of technological devices, it has been observed that there are significant differences between the different age ranges, which corroborates the findings made by Cabero and Barroso (Citation2016) and Gudmundsdottir and Hatlevick (Citation2018). This is in contrast to John (Citation2015), who has stated that middle-aged teachers have a higher level of ICT use than younger teachers. On the other hand, it can be affirmed that age correlates negatively both with the use of Web 2.0 tools and with the use of learning management systems. This is confirmed by the works of O’bannon and Thomas (Citation2014), Vanderlinde et al. (Citation2014) and Siddiq et al. (Citation2016).

The data shows that motivation is an essential variable in the level of pedagogical digital competence development, both in the use of technological devices and in the use of Web 2.0 tools and learning management systems. This motivation significantly affects all the dimensions analysed. These results are in accordance with those of Tømte et al. (Citation2015), since motivation to use ICT is crucial. Nonetheless, despite the fact that future foreign language teachers claim to be very motivated to use ICT, Web 2.0 tools and learning management systems, the analyses show that their use is limited when it comes to teaching languages. These results contradict those obtained by Sang et al. (Citation2011), Blackwell et al. (Citation2013) and Hsu et al. (Citation2017), since, according to these authors, greater motivation equates greater use of ICT.

In short, the second research question can be answered affirmatively because variables, such as sex, age and motivation, significantly influence the level of development of pedagogical digital competence.

6. Conclusions

There is no doubt that ICT today must incorporate transversal tools for the field of education in general, and more specifically with regard to learning a foreign language because they greatly favour the development of linguistic skills (Altun, Citation2015) and enable meaningful learning. In spite of this, this work has demonstrated that future foreign language teachers have a medium-low development of pedagogical digital competence. The result of this is that technologies are still not being used today for pedagogical purposes. The lack of pedagogical use may be due to the fact that the teaching staff do not have a solid initial pedagogical training with regard to the development of digital competence, which implies their limited use of ICT (Salomaa et al., Citation2017), as well as their tendency to only use the best known tools on the market.

To a certain extent, the pedagogical digital competence level continues to be influenced by variables such as gender, age and motivation. From these variables, it can be concluded that motivation is the variable that most influences pedagogical digital competence development (Blackwell et al., Citation2013; Hsu et al., Citation2017; Naqvi, Citation2017), although it is also conditioned by age. Despite that fact that, in general, future teachers have an adequate motivation to use ICT, there is still a lack of pedagogical consistency in their use. All teachers, and specifically foreign language teachers, must make use of the tools available to them to teach languages, since these tools are fundamental for the acquisition of languages (Bucur & Popa, Citation2017; Tømte et al., Citation2015). Therefore, little by little, both from initial training and from continuing education, educational institutions should focus on the training of future teachers based on motivation, ensuring that said teachers see the real benefits of using ICT. This is confirmed by Røkenes and Krumsvik (Citation2016), who state that teachers who use ICT obtain more positive results from their students.

It can be concluded, therefore, that, in order to improve the current situation regarding the level of pre-service teachers’ pedagogical digital competence, greater training is necessary. For this reason, the current study could be furthered by carrying out experimental study pre-tests and post-tests with a control group and an experimental group. This experimentation would consist of specific training that would increase the pedagogical training of pre-service teachers in the use of ICT for language teaching.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Francisco D. Guillén-Gámez

Francisco D. Guillén-Gámez is a Professor who specializes on Information and communication technology applied to education, as well as the evaluation of the digital competence of the teaching staff. Mª José Mayorga-Fernández holds a Ph.D in Pedagogy. Her main lines of research are educational evaluation, didactics and Information and communication technology applied to education. Ana Lugones Hoya holds a Ph.D in Hispanic and English Philology. Her research focuses on new methodologies in FL teaching.

References

- Akbulut, Y., Odabasi, H. F., & Kuzu, A. (2011). Perceptions of preservice teachers regarding the integration of information and communication technologies in Turkish education faculties. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 10(3), 175–17.

- Altun, M. (2015). The integration of technology into foreign language teaching. International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications, 6(1), 22–27.

- Antonietti, A., & Giorgetti, M. (2006). Teachers’ beliefs about learning from multimedia. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(2), 267–282. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2004.06.002

- Balta, N., & Duran, M. (2015). Attitudes of studens and teachers towards the use of interactive whiteboards in elementary and secondary schools classrooms. TOJET: the Turkish Online Journal of Educational Tecnology, 14(2), 15–21.

- Barr, D. (2016). Students and ICT: An analysis of student reaction to the use of computer technology in language learning. IALLT Journal of Language Learning Technologies, 36(2), 19–38.

- Barrett, P. (2007). Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 815–824. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.018

- Bisquerra, R. (2004). Metodología de la investigación educativa. Madrid: Plaza.

- Blackwell, C. K., Lauricella, A. R., Wartella, E., Robb, M., & Schomburg, R. (2013). Adoption and use of technology in early education: The interplay of extrinsic barriers and teacher attitudes. Computers & Education, 69, 310–319. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.07.024

- Blake, R. J. (2013). Brave new digital classroom: Technology and foreign language learning. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Blau, I., & Shamir-Inbal, T. (2017). Digital competences and long-term ICT integration in school culture: The perspective of elementary school leaders. Education and Information Technologies, 22(3), 769–787. doi:10.1007/s10639-015-9456-7

- Brown, T. A. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Bucur, N. F., & Popa, O. R. (2017). Digital competence in learning English as a foreign language–opportunities and obstacles. The 12th international conference on virtual learning (Vol. 156, pp. 257–263). Sibiu.

- Cabero, J., & Barroso, J. (2016). ICT teacher training: A view of the TPACK model/Formación del profesorado en TIC: Una visión del modelo TPACK. Cultura y educación, 28(3), 633–663. doi:10.1080/11356405.2016.1203526

- Carretero-Dios, H., & Pérez, C. (2005). Normas para el desarrollo y revisión de estudios instrumentales. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 5(3), 521–551.

- Castaneda, M. (2013). Digital storytelling: Building 21st-century literacy in the foreign language classroom. Northeast conference on the teaching of foreign languages review.The NECTFL review (Vol. 71, pp. 55–65). Salisbury University.

- Cuhadar, C. (2018). Investigation of pre-service teachers’ levels of readiness to technology integration in education. Contemporary Educational Technology, 9(1), 61–75.

- Damodaran, L., & Burrows, H. (2017). Digital skills across the lifetime: Existing provisions and future challenges, 1 (1) 1–49.

- Erstad, O. (2010). Conceptions of technology literacy and fluency. In International encyclopedia of education (3rd ed., pp. 34–41). Oxford: Elsevier.

- Evans, R. (2009). Foreign language learning with digital technology: A review of policy and research evidence (pp. 7–32). Great Britain: McMillan.

- Ferrari, A. (2013). GIGCOMP. A framework for developing and understanding digital competence in Europe. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. London: Sage Publications.

- From, J. (2017). Pedagogical digital competence–Between values, knowledge and skills. Higher Education Studies, 7(2), 43–50. doi:10.5539/hes.v7n2p43

- Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Hatlevik, O. E. (2018). Newly qualified teachers’ professional digital competence: Implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 214–231. doi:10.1080/02619768.2017.1416085

- Guillén-Gámez, F. D., Mayorga-Fernández, M. J., & Álvarez-García, F. J. (2018). A study on the actual use of digital competence in the practicum of education degree. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 1–18. doi:10.1007/s10758-018-9390-z

- Hall, R., Atkins, L., & Fraser, J. (2014). Defining a self-evaluation digital literacy framework for secondary educators: The DigiLitLecister project. Research in Learning Technology, 22, 1–17. doi:10.3402/rlt.v22.21440

- Hartley, J. (2017). Uses of YouTube digital literacy and the growth of knowledge. In The uses of digital literacy, Transaction Publishers (pp. 110–131). New Brunswick: Routledge.

- Hsu, C. Y., Tsai, M. J., Chang, Y. H., & Liang, J. C. (2017). Surveying in-service teachers’ beliefs about game-based learning and perceptions of technological pedagogical and content knowledge of games. Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 134–143. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.20.1.134

- Instefjord, E. J., & Munthe, E. (2017). Educating digitally competent teachers: A study of integration of professional digital competence in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.016

- John, S. P. (2015). The integration of information technology in higher education: A study of faculty’s attitude towards IT adoption in the teaching process. Contaduría y Administración, 60, 230–252. doi:10.1016/j.cya.2015.08.004

- Kerlinger, F. N. L., Howard, B., Pineda, L. E., & Mora Magaña, I. (2002). Investigación del comportamiento. México: McGraw Hill.

- Koh, J. H. L., Chai, C. S., Benjamin, W., & Hong, H. Y. (2015). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) and design thinking: A framework to support ICT lesson design for 21st century learning. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24(3), 535–543. doi:10.1007/s40299-015-0237-2

- Kori, K., Pedaste, M., Leijen, Ä., & Tõnisson, E. (2016). The role of programming experience in ICT students’ learning motivation and academic achievement. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 6(5), 331–337. doi:10.7763/IJIET.2016.V6.709

- Krumsvik, R. J. (2014). Teacher educators’ digital competence. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58, 269–280. doi:10.1080/00313831.2012.726273

- Lin, T. J., Duh, H. B. L., Li, N., Wang, H. Y., & Tsai, C. C. (2013). An investigation of learners’ collaborative knowledge construction performances and behavior patterns in an augmented reality simulation system. Computers & Education, 68, 314–321. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.011

- Naqvi, S. (2017). Towards an integrated framework: Use of constructivist and experiential learning approaches in ICT-supported language learning. In Conference proceedings. ICT for language learning (pp. 229–234). libreriauniversitaria. it Edizioni.

- Norman, G. (2010). Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 15(5), 625–632. doi:10.1007/s10459-010-9222-y

- O’bannon, B. W., & Thomas, K. (2014). Teacher perceptions of using mobile phones in the classroom: Age matters! Computers & Education, 74, 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2014.01.006

- O’Dowd, R. (2013). Telecollaborative networks in university higher education: Overcoming barriers to integration. The Internet and Higher Education, 18, 47–53. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.02.001

- O’Dowd, R. (2015). Supporting in-service language educators in learning to telecollaborate. Language Learning & Technology, 19(1), 63–82. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/issues/february2015/odowd.pdf

- Ottestad, G., Kelentrić, M., & Guðmundsdóttir, G. B. (2014). Professional digital competence in teacher education. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 9(04), 243–249.

- Pinto-Llorente, A. M., Sánchez-Gómez, M. C., García-Peñalvo, F. J., & Casillas-Martín, S. (2017). Students’ perceptions and attitudes towards asynchronous technological tools in blended-learning training to improve grammatical competence in English as a second language. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 632–643. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.071

- Proshkin, V., Glushak, O., & Mazur, N. (2018). The modern trends in future foreign language teachers training to ICT usage in their future career. The Modern Higher Education Review, 2, 145–153.

- Røkenes, F. M., & Krumsvik, R. J. (2016). Prepared to teach ESL with ICT? A study of digital competence in Norwegian teacher education. Computers & Education, 97, 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2016.02.014

- Rosenthal, R. (1994). Parametric measures of effect size. The Handbook of Research Synthesis, 621, 231–244.

- Sadaf, A., Newby, T. J., & Ertmer, P. A. (2016). An investigation of the factors that influence preservice teachers’ intentions and integration of Web 2.0 tools. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(1), 37–64. doi:10.1007/s11423-015-9410-9

- Salomaa, S., Palsa, L., & Malinen, V. (2017). Summary. In S. Salomaa, L. Palsa, & V. Malinen (Eds.), Opettajaopiskelijatjamediakasvatus [Teacher Students and Media Education] (Vol. 51). National Audiovisual Institute. Kansallinen audiovisuaalinen instituutti.

- Sampaio, D., & Almeida, P. (2016). Pedagogical strategies for the integration of augmented reality in ICT teaching and learning processes. Procedia Computer Science, 100, 894–899. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.240

- Sang, G., Valcke, M., Van Braak, J., & Tondeur, J. (2010). Student teachers’ thinking processes and ICT integration: Predictors of prospective teaching behaviors with educational technology. Computers & Education, 54(1), 103–112. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.07.010

- Sang, G., Valcke, M., Van Braak, J., Tondeur, J., & Zhu, C. (2011). Predicting ICT integration into classroom teaching in Chinese primary schools: Exploring the complex interplay of teacher‐related variables. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(2), 160–172. doi:10.1111/jca.2011.27.issue-2

- Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Teo, T. (2015). Becoming more specific: Measuring and modeling teachers’ perceived usefulness of ICT in the context of teaching and learning. Computers & Education, 88, 202–214. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.05.005

- Seedhouse, P. (Ed.). (2017). Task-based language learning in a real-world digital environment: The European digital kitchen. Great Britain: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Sefton-Green, J., Marsh, J., Erstad, O., & Flewitt, R. (2016). Establishing a research agenda for digital literacy practices of young children: A white paper for COST action IS1410 (pp. 1–37). Brussels: European Cooperation in Science and Technology.

- Shyshkina. (2018). Holistic approach to training of ICT skilled educational personnel. CEUR workshop proceedings (Vol. 1000, pp. 436–445). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.08717v1

- Siddiq, F., Scherer, R., & Tondeur, J. (2016). Teachers’ emphasis on developing students’ digital information and communication skills (TEDDICS): A new construct in 21st century education. Computers & Education, 92, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.006

- Simon, M. K., & Goes, J. (2013, September 25). Ex post facto research.

- Tømte, C., Enochsson, A. B., Buskqvist, U., & Kårstein, A. (2015). Educating online student teachers to master professional digital competence: The TPACK-framework goes online. Computers & Education, 84, 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2015.01.005

- Tondeur, J., Aesaert, K., Pynoo, B., Van Braak, J., Fraeyman, N., & Erstad, O. (2017). Developing a validated instrument to measure preservice teachers’ ICT competencies: Meeting the demands of the 21st century. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 462–472. doi:10.1111/bjet.2017.48.issue-2

- Tondeur, J., Van de Velde, S., Vermeersch, H., & Van Houtte, M. (2016). Gender differences in the ICT profile of university students: A quantitative analysis. DiGeSt. Journal of Diversity and Gender Studies, 3(1), 57–77. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.11116/jdivegendstud.3.1.0057

- Van Deursen, A. J., & Van Dijk, J. A. (2014). Digital skills: Unlocking the information society. Springer.

- Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2015). A theory of the digital divide. In M. Ragnedda & G. W. Muschert (Eds.), Digital divide max weber and digital divide studies: Introduction. International Journal of Communication (Vol. 9, pp. 2757–2762). University of Southern California, Annenberg Press.

- Vanderlinde, R., Aesaert, K., & Van Braak, J. (2014). Institutionalised ICT use in primary education: A multilevel analysis. Computers & Education, 72, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2013.10.007

Appendix 1