Abstract

Teachers are difficult to change, and this has long been a challenge for many teacher educators because a fundamental maxim of teacher education programs is to promote reflection and change in teachers. Despite the many studies on teacher change, our understanding of teacher change requires further understanding. Based on a narrative inquiry of teacher “Blue”, the present study found that teacher resilience and reflection, as well as continuing professional development learning are the three most important factors that led to her self-initiated change. In addition, Blue’s change as a teacher developed along with her deepened and broadened reflection of her teaching content, and methods, as well as her beliefs about her students and other socio-cultural issues. Rather than refurbishing her entire belief and practice, Blue’s change was a gradual extension of her schema; she built her new ideas upon the old, through constant reflection, teacher learning, and with her resilience.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Teachers find change difficult, and this has long been a challenge of many teacher educators because a principal aim of teacher education programs is to change teachers. Based on a narrative inquiry of a teacher named Blue, the present study found that teacher resilience and reflection, as well as continuing professional development learning, are the three most important factors that led to her self-initiated change. Besides, Blue’s change as a teacher developed along with her deepened and broadened reflection of her teaching content, and methods, as well as her beliefs about the students and other socio-cultural issues. This finding is constructive for future teacher educators in designing a more effective training program.

1. Introduction

The behavior and beliefs of teachers are difficult to change unless they are willing to do so (Richardson, Citation1998). Although the sole aim of most teacher education programs is to change teachers’ practice and belief (Cohen & Hill, Citation2000), the impact of many teacher education programs has only scratched the surface (Guskey, Citation2002). This appears to be especially the case for teachers in foreign language teaching programmes in China. Some university English teachers (UETs) teaching non-English major students in China are said to be reluctant to become more research oriented. One study, for example, found these teachers to have a low engagement rate in research activities (Borg & Liu, Citation2013).

In the higher education system of China, there exists a division in university English teachers: those teaching English major students (including English literature, linguistic, translation etc.) and those teaching English to non-English major students (Cheng, Citation2016). The main participant in the present case study belongs to the latter group, and the UETs mentioned here also refer to the latter community. The former tend to be highly regarded as academics and professionals, while the latter community has a declining status partly because of the development of English learning resources on the internet and the prosperity of the Chinese economy (Liu, Citation2011).

Born in the era of China’s economic expansion, the default career course of those aspiring to be English teachers was to simply teach students to exchange with foreign countries, rather than to become researchers or academics (Liu, Citation2011). Today, however, China has become the second largest economy in the world and one of the most important players in globalization, with universities being more or less influenced by neo-liberalism (Hadley, Citation2015). Therefore, university teachers have rather suddenly had to play the game of “publish or perish” (Lee, Citation2014); however, many of them have no knowledge of how to conduct research (Borg & Liu, Citation2013), and thus many UETs have become confused about their identities (Liu, Citation2011).

With this backdrop, a teacher named Blue (a pseudonym), came to my attention because I was struck by her persistence in changing her teaching beliefs and methods under the new reality. In most of her attempts to change her teaching beliefs and method, she experienced challenges from many stakeholders: the department head, students, colleagues, and even the environment she was in. Essentially, Blue’s case triggered my interest in exploring her story of teacher change. Her persistence when facing the odds might enrich our understanding of teacher change in the face of considerable institutional and administrative pressure.

2. Literature review

2.1. Teacher change

To promote teacher change is the chief aim of all teacher education programs (Griffin, Citation1983; Guskey, Citation2002; Richards, Gallo, & Renandya, Citation2001). Through various formats of training, teachers are expected to refine their practice, attitude, and belief of teaching (Guskey, Citation2002). However, studies on many teacher training programs since the 1970s have found that change is enormously difficult to achieve (Richardson, Citation1998; Cohen & Hill, Citation2000; Hoban, Citation2002). As Gebhard, Gaitan, and Oprandy (Citation1990, p. 14) claimed: “teachers, even with training, do not change the way they teach, but continue to follow the same pattern of teaching.” Meanwhile, there are scholars such as Richardson (Citation1998), who noticed teachers are changing all the time. “Change is complex and multifaceted” (Richards et al., Citation2001, p. 41), and deepening people’s understanding of teacher change is important because it is fundamental to teacher education.

2.2. Strands and factors explaining teacher change

For decades, researchers have explored the issue of teacher change. Some studies have explained the process of teacher change (e.g., Cobb, Wood, & Yackel, Citation1990; Dole & Sinatra, Citation1998; Gregoire, Citation2003; Guskey, Citation1985, Citation1986, Citation2002; Posner, Strike, Hewson, & Gertzog, Citation1982), while others have revealed the factors influencing teacher change (e.g., Bailey, Citation1992; Cheung & Wong, Citation2017; Gregoire, Citation2003). A traditional view originating from Lewin’s (Citation1935) work (psychotherapeutic models producing change) holds that “changes in teachers’ practice are the result of changes in teachers’ beliefs” (Richards et al., Citation2001, p. 41). While Guskey (Citation2002) proposed an alternative process of teacher change, that incorporated the traditional view of teacher change.

Guskey’s (Citation2002) teacher change model is outcome based, emphasizing that the change of teachers’ belief can only happen when teachers are witnessing improvements in students’ learning outcomes after adopting a new classroom practice. There are many studies supporting this hypothesis (e.g., Fullan, Citation1991; Guskey & Sparks, Citation1996). In a critical case of Stein et al. (Citation1996), researchers discovered that over a long period of methodological reform, many in-service teachers were indeed using the methods that the reform developer required; however, over a period of time, the teachers seemed to use them mechanically without any cognitive demand. In light of this, Gregoire (Citation2003) commented that change of practice might not lead to change of beliefs, even though teachers admitted they had seen the benefits of applying new methods, or they admitted their change, which is contradictory to Guskey’s hypothesis (Citation2002).

Generally speaking, both strands of explanation of teacher change (the traditional and alternative view) seem oversimplified, treating human cognitive change as linear, and filtering out other contributing factors for teacher change. Pajares (Citation1992) and Thompson (Citation1992) once stated that a total teacher change is unlikely to happen because teachers will just selectively accept what they have learned in a training program and build their discriminated knowledge onto their preexisting schema. Therefore, instead of embracing an utter change, the teachers are more likely to merge their original teaching strategy with a new one, producing a somewhat compromised option (Chinn & Brewer, Citation1993; Gregoire, Citation2003; Liu & Xu, Citation2011). Furthermore, teachers’ established belief in their teaching subjects (Fennema & Franke, Citation1992), understanding of their students and classroom discourse (Sowder, Philipp, Armstrong, & Schappelle, Citation1998), and attitude towards a specific teacher change training program (Ashton & Gregoire, Citation2003), are different from other teachers’, and they will all influence teacher change. From a different perspective, contributing factors to teacher change might not be all pedagogical; there could be personal reasons such as “teachers experienc[ing] dissatisfaction with the status quo” and “life changes [leading] to personal growth, which fostered classroom innovations” (Bailey, Citation1992, p. 271).

Considering the complexity, Gregoire (Citation2003) hypothesized a Cognitive-affective model to explain teacher change, based on an adaptation of five models in social psychology (Dissonance Theory, Conceptual change model, Dual-process models, Cognitive reconstruction of knowledge model, and Fazio’s Model). He proposed a cognitive map of teacher’s conceptual change and included an array of pedagogical, emotional, and contextual factors influencing teacher change. However, Gregoire’s (Citation2003) hypothesis was conditional upon teacher change in educational reforms. Cheung and Wong (Citation2017) even found the extent of teachers’ reflection on teaching, students, and social issues determines the actualization of teacher change. The aforementioned strands and contributing factors are definitely not an exhaustive list of debates explaining the process of teacher change. Until today, common ground has not been reached. However, what is worth noticing is that all of these studies of teacher change were either in the background of educational reform, or in response to a certain sponsored teacher training program; notably, studies on self-initiated teacher change were not considered; therefore, examining Blue’s story may shed light on this area.

2.3. Methods and examples strengthening teacher change

There are also many studies that have discussed methods and cases promoting or reporting successful teacher change (Richards et al., Citation2001; Tam, Citation2015; Trigueros & Lozano, Citation2015; Tripp & Rich, Citation2012; Tse, Ip, Tan, & Ko, Citation2012). Tripp and Rich (Citation2012) showed that teachers reviewing video recording of their teaching could assist teacher reflection and facilitate teacher change. Tam (Citation2015) found building a professional learning community, in which teachers support each other, supported teacher change. Richards et al. (Citation2001) found the following methods in teacher training were the top practices improving teacher change: in-service courses, seminars, conferences, student feedback, teachers’ self-discovery activities, trial and error activities, and collaborations. Trigueros and Lozano (Citation2015) looked at teachers through an enactivist paradigm, finding that teachers had raised awareness in subject matters, symbolizing teacher change. Tse et al. (Citation2012) found the evidence of teacher change after they traced a group of Taiwan teachers completing a field trip teacher-training program based in Hong Kong and Taiwan under the collaborations of universities, schools, teachers from both territories, and non-governmental social enterprises. All of these studies are informative to future teacher educators.

2.4. Research questions

In order to further understand the mechanism of teacher change and to narrow down the possible elements instigating teacher change in order to give reference to future teacher training programs, the present case study took an exploratory posture to look at Blue’s self-initiated teacher change story. The following two research questions were designed to guide the data collection and analysis: 1. What are the contributing factors to Blue’s self-initiated teacher change? 2. How did teacher change happen to Blue? What are the characteristics of teacher change in the case of Blue?

3. Research methodology

3.1. Narrative inquiry

The current study adopted the methods of narrative inquiry to explore Blue’s self-initiated teacher change. As Gajek (Citation2014, p. 14) concluded, “We have no other possible means to describe the time we have lived apart from the narrative.” Narrative enquiry is an “experience-near” (Geertz, Citation2000) method recollecting a person’s life, experiences, and emotion from the hero/heroine’s hermeneutic perspective. In the research of teacher education, narrative inquiry investigates teachers’ experience and practical knowledge with abundant and insightful data (Tsui, Citation2007; Xu & Connelly, Citation2009). Blue had undergone ups and downs in her teaching career. She also waded through students’ complaints, criticism from her superiors, and misunderstandings from the colleagues. I believed that Blue was the only person who could revive these past moments and make meaning for her teacher change experience: “through narratives, people tell others who they are… they are themselves and they try to act as though they are who they say they are” (Holland, Ramazanoglu, Sharpe, & Thomson, Citation1998, p. 3). Thus, narrative inquiry was considered the most suitable for the present research.

3.2. Positionality of the author

As narrative includes storytelling, it takes time and confidentiality (Gajek, Citation2014) for the narrator to open-up and to share with the listener his/her private story. In order to raise the trustworthiness of the storytelling, a friendly relationship, or trust, between the narrator and the listener is important (Gajek, Citation2014). The present study is based on the reanalysis of data in an ethnographic study I conducted for my PhD project. I spent nearly one and a half years in the field investigating the pedagogical transition of some UETs from teaching English for General Purposes to English for Academic Purposes (EAP) in Shanghai, and Blue was one of them. At the time of this writing, I had known Blue for three years, and we had become good friends and academic peers. I joined Blue’s EAP teacher community as a researcher in EAP, which facilitated our communication. Apart from the observations and ethnographic interviews on Blue’s teaching, I had most of my unstructured interviews with Blue over lunch or dinner tables, with our conversations recorded. When I was analyzing the data, I sometimes asked Blue to clarify her life story through text messages in social media, which were screen-shot and saved in my PC. I also observed Blue’s teaching many times in classrooms. In support of her teaching, I often updated her with state-of-the-art EAP materials. So the ethnographic foundation provided a naturalistic opportunity for Blue and I to become friends with each other, increasing the trustworthiness of the narrative inquiry, making it both ethnographic- and narrative-oriented, and formulating a methodological triangulation (Liu & Xu, Citation2011).

3.3. Data analysis

The interviews with Blue were conducted in Chinese, including the online text-message interviews. These were later transcribed manually and translated by me, a professional bilingual. During the manual transcription of the interviews, I actually had an overview of all the content, which was helpful to my understanding of the data (O’Reilly, Citation2008). In my second round of data reading, I adopted open-coding methods to categorize different life stages of Blue and most importantly, to identify some main themes from the data. During this process, the following themes were noted: 1) dissatisfaction with the teaching, 2) devising better solutions, and 3) implementing new teaching methods. Then, I streamed various themes under Blue’s different life stages as a storyline. Eleven mini-stories were developed from these and reconstructed. I gave each a title: “The English courses are just not enough for my students”; “Compiling a good textbook of English by myself”; “How to remember as much vocabulary as possible permanently?”; “ Students made a big complaint about me to the university president”; “They have no motivation to study English, except for sitting exams”; “Losing Professorship and studying in the US”; “Correcting students’ learning habits by giving them a more academic environment composed of multiple literacies”; Chances and challenges in establishing an EAP utopia; “Developing an EAP course made me enemies with everybody”; “Chinese universities are not nurturing scholars with an academic spirits”; and “Our EAP spirit: academic honesty, knowledge-pursuing, truth-seeking, and willingness to share”. The 11 mini-stories constituted story constellations (Craig, Citation2007), returning and reviving Blue’s teacher change experience to the readers. During the story composing, I returned the manuscripts to Blue for rechecking and supplementing in order to strengthen the trustworthiness of the story (Creswell, Citation2012) and retell Blue’s story of self-initiated teacher change (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation2000).

4. Findings

Born into a military family, Blue had always excelled in her English class. In the mid-1980s, she was recruited by E University to study international business as a major and English as minor. At the beginning of the 1990s, after four years of undergraduate studies, she was admitted as a postgraduate without the need for any exams. Her postgraduate research area was applied linguistics and her specific research direction was English teaching methodology. What is noteworthy is that her postgraduate studies were the product of cooperation between her Chinese university and the British Council, and one of the requirements of enrolment was that graduates must agree to be teachers and teach at E University after graduation. She taught English at the university for two years, and then moved to university H (HU). With this background, the 11 mini-stories are discussed in detail.

4.1. The English courses are just not enough for my students

Blue moved to HU to teach non-English major students general English, but HU is a science- oriented institute, and English was not regarded as an important subject. English lessons for Blue’s students were very few; students studied English for four hours each week in the classroom, which were reckoned by Blue far from enough to be able to equip students living in a globalized world. Apart from this, Blue ironically told me the textbooks students used only contained 12 articles; students were meant to finish studying them in class within one academic year. “The English courses are just not enough for my students” (Blue interview). Blue judged that such an English course designed by HU could not provide a sufficient amount of English for tertiary level studies.

4.2. Compiling a good textbook of English by myself

Facing such difficulty, Blue looked for solutions. Drawing on her knowledge of input hypothesis theory (Krashen, Citation1985) in Second Language Acquisition (SLA), Blue collected and wrote 100 English articles, covering various topics of life, and she printed and bound them into books for students to study in class. As a supplement to the original textbook, Blue demanded that students read one article every two days. Thus, Blue assumed her students could fully make use of their class and spare time embracing a larger input of authentic English.

4.3. How to remember as much vocabulary as possible permanently?

Teaching English articles, Blue noted that students met many new words in each text, but they seemed not to be able to remember those words: “no matter how diligent the students tried to remember the vocabulary, they forgot it immediately. You know that English teaching in the early days of China was teaching vocabulary… because (students and teachers) believed that vocabulary is the bottleneck to learning English… before students entered the universities, they should have finished learning English grammar, so the only obstacle students had when learning English was how to remember as many new words as possible” (Blue interview). Recalling her old view of English, Blue laughed at herself. However, she had always been an attentive teacher, and at that time, she assumed it could be solved by deepening her understanding of human cognition.

Thus, Blue applied for a visiting scholar position back to E University and began reading the works of a famous psychologist to familiarize herself with human cognition and its relationship with remembering English vocabulary. Meanwhile, Blue used what she had learnt in order to develop questionnaires and experimental exam papers. Blue handed out questionnaires and different kinds of vocabulary tests to her students in classes back in HU, where she retained her post. After collecting all the data, Blue intended to get them analyzed and published; however, surprisingly, Blue’s supervisor in E University published it as the first author while placing Blue as the sixth author.

4.4. Students made a big complaint about me to the university president

One day Blue received a phone call from the university president’s office, saying they had received complaints from her students on their increasing study load, and also that her teaching materials were irrelevant to course textbooks. She was then called to the president’s office. Feeling a little nervous, Blue prepared enough justification for herself; however, the president praised Blue’s approach to teaching as scientific. However, as the curriculum of English was standardized and benchmarked across different universities in Shanghai, there was little that he could do to help her. Later, Blue heard from her colleagues that on the HU blog, some of Blue’s students had complained about her.

4.5. They have no motivation to study English, except for sitting exams

Blue explained in one interview: “I adopted new methods, but the students refused them. They even wondered why their English lessons were becoming more difficult. It is not my teaching methods that matters; no matter what kind of methods I choose, it will not improve their learning as long as they have no motivation.” Looking back at the students’ pre-tertiary education experience, Blue boldly speculated on the reasons for students’ demotivation: “it was the ‘learning for exams’ habit continuing from their pre-tertiary education that disturbs students; without exams, they would not learn; they would not cram on English unless they were to have exams.” Therefore, Blue sensed an urgency to correct students’ learning habits, but at that moment, she could not come up with an approach. In order to attract students’ attention and tailor to their tastes, Blue started to use some social media and online blogs to organize student discussions and English reading, hoping new methods could motivate them, although she later found they did not play a vital role.

4.6. Losing professorship and studying in the US

Although the university president empathized with Blue, the students’ complaints irritated her department head because being reported to the president brought disgrace upon the department. Thus, Blue felt a change of attitude towards her head. Unfortunately, just before Blue applied for promotion to professor, she missed the time and venue of the application meeting because no one had informed her, although the rest of the candidates were all there. Blue knew it was not a haphazard accident, but rather a conspiracy against her. Wet eyed and heart broken, even when Blue mentioned this to me, she was unable to control her emotions. Blue chose to take a one-year break and went to study in a prestigious university in the US.

4.7. Correcting students’ learning habits by giving them a more academic environment composed of multiple literacies

Studying in the US, Blue attained a good overview of higher education there. She noticed that undergraduates in her university wisely made use of the library, were involved in group-discussions, and wrote essays based on their research and community service. Blue believed these embodied the ideal academic environment that Blue had been longing for. The American students’ motivation impressed her, compared with the demotivated students who were cramming for exams and memorizing textbooks back in HU. Blue seemed to have some clues about the cause of the problems. In the US, “a university is academic-oriented while Chinese universities are not academic enough; they are more like an extension of high school.”

Blue, thus, decided to transform her English course again in order to reorient her newly enrolled students, showing them the meaning and practice of having an academic mindset in university: “I will lead them to contemplate academic meaning, rather than simply how to spend four years in university; they should consider the essence of university and its meaning to them. This will be the core of my English course. Knowing the academic nature of university, students could know how to study in the university” and forsake their residue learning habits from high school” (Blue interview).

Based on literacy theory learnt in the US, Blue produced a three-semester-long multiple literacies English course outline. Table is an example of the first semester:

Table 1. Blue’s multiple literacies course outline for the first semester

Blue believed the literacy theory could change students’ learning habits and make them more motivated to study English.

4.8. Chances and challenges in establishing an EAP utopia

Returning to China, Blue decided to overhaul her English classes on the basis of her designed multiple literacies outline. Coincidently, the Shanghai Education Bureau initiated an EAP reform across different universities, encouraging non-English major students to stop learning EGP and start studying EAP instead, in order to help them publish their disciplinary papers in international journals. The reform policymakers, however, did not provide a concrete curriculum for each university, nor did they provide systematic teacher training. With similar academic purposes, this reform echoed Blue’s intention. Without gaining the support of the department head in HU, Blue became a leader in developing the multiple literacies based EAP course in HU, utilizing the outline she created in the US.

Quickly organizing some colleagues, they started the reform as an HU EAP team. In order to support their experiments, Blue wrote up a proposal and successfully secured funding from the China Education Ministry. For disseminating her idea and course work, Blue created an official WeChat social media account, befriended all her students and people with interests in EAP, and she shared texts and videos related to EAP with them. She also established an online discussion forum, gathering students to discuss topics in English. Soon, Blue and her team drew much attention; visitors came to learn from them. From Blue’s perspective, she saw an obvious progress in students’ motivation and learning habits. With so much encouragement, Blue and her teammates decided to get their EAP course a code, different from the general English course, which would allow all students in HU to enroll.

4.9. Developing an EAP course made me an enemy with everyone

Just when Blue and her team were reaching some success in teaching English and promoting students’ motivation, they encountered unexpected resistance. Blue commented, “I could never foresee that doing EAP could involve making enemies with everybody. Even on the university bus, not a single teacher dared to sit beside me out of fear. They did not want to show their friendliness to me… sitting beside me as would mean being hostile to the head.”

Because, from the beginning to end, HU did not officially announce that they started the EAP reform, Blue’s behavior incurred unpleasantness from the department members, who suspected she was again making trouble. Blue said her department was suspecting that she was propagating some ideology not suitable in China, and organizing a party among teachers disturbed the unity. With all the misunderstanding, the department advanced documents stipulating the teaching content of English teachers, which had to be in accordance with textbooks. Naturally, Blue’s application for a course code was rejected and Blue’s team members were asked to see the department head, who persuaded them to give up EAP in order to guarantee their position and pay rise. Feeling stressed out, many of Blue’s colleagues quit.

What depressed Blue the most was that during her visit to her sick daughter in the US, the department head clamped down on the rest of Blue’s EAP team by giving them an official order and cancelled all of Blue’s English lessons. In order to settle the conflicts, Blue began to negotiate with the department heads. After several months’ struggle, in which Blue had carefully explained the importance of EAP to the department, the university president intervened. The department agreed to allow a very small quota of students to study EAP, but Blue must teach the required textbooks in class; however, no more teachers in the EAP team decided to participate and the EAP team was eventually dissolved. In addition, many team members refused to sit beside Blue on the university shuttle bus, displaying their loyalty to the department head.

4.10. Chinese universities are not nurturing scholars with an academic spirit

The conflict with the department again dragged Blue into deep thinking. Recalling her research data being grabbed and published by her previous supervisor while she was studying in E university as a visiting scholar; coupled with her team members’ withdrawal regardless of the benefits the course brought to students, Blue asserted that these scholars did not have an appropriate academic spirit: “The external reason why our team was disbanded was the objection from those in a managerial position, but the internal reason was related to our member teachers themselves. They did not understand the essence of EAP… if EAP had become a belief, they would not have given up their lessons in response to an objection from the departmental heads.”

Knowing this result was not a personal phenomenon, Blue assumed that it was the university environment that had failed to educate students into scholars with an academic spirit: “If teachers are like this, how good could their students be?” Blue awoke with an inspiration: “I need to give students an identity as true scholars. With such an identity, they will develop a sense of belonging, which directly leads to motivation and passion for learning.”

4.11. Our EAP spirit: academic honesty, knowledge-pursuing, truth-seeking, and willingness to share

“In order to establish a scholarly identity, students have to understand that scholars’ only stance is academic honesty, knowledge-pursuing, truth-seeking, and willingness to share”. Blue wrote these characteristics into the official WeChat account, hoping her students could develop as true scholars. Being restricted from teaching EAP in class, Blue invented new methods to spread her ideas and organize academic activities. Utilizing the WeChat account Blue had been managing, she posted almost all of her EAP course materials onto it, engaging students to learn after class. Alongside the original series WeChat feeds like “Academic Vocabulary” and “BBC news listening,” Blue included new series to help students to reflect on their identity: “World beyond China,” “Studying abroad,” and “Critical thinking.” Blue believed that by exposing students to these WeChat feeds, their worldview and academic English could be increased.

Blue helped her students establish a student society entitled the EAP club (EAPC), attracting students in HU to participate in the academic, English-related activities the club organized. In this vein, Blue could continue her EAP teaching in the name of student society activities regardless of the restrictions from the department. In the EAPC, Blue frequently invited role model teachers from different universities (I was also invited) to share with students their English learning experiences and research ideas. In the name of the EAPC, Blue also organized a student research conference, inviting students to present their own research. With the help of the university president, Blue led the EAPC in winning a bid for translating Chinese documents into English for the Chinese Academy of Engineering, giving student members a chance to use their academic English in real disciplinary contexts.

This is not an exhaustive list of Blue’s EAP activities, which may have contributed to their identity formation as scholars: “I just feel establishing a scholarly identity among students is the everlasting mission of EAP teaching; if they (students) consider themselves as scholars and are proud of such an identity, my EAP teaching is successful. Because the more students learn language or words, the quicker they forget; however, an established identity is permanent, they may be motivated to learn on and on” (Blue interview).

Blue’s story is not finished, as long as she is teaching, she will not stop thinking and changing. Hearing of her many positive and negative experiences, I could not help wondering so I asked her: “What made you keep on changing your teaching?” The answer she gave me resonated: “My purpose has always been to improve teaching and learning.” Just as straightforward as any philosophy behind a phenomenon, Blue’s answer was simply the intentions of a good teacher.

5. Discussion

5.1. What are the contributing factors to blue’s self-initiated teacher change?

5.1.1. Teacher resilience

The teacher resilience Blue had when facing challenges could be a factor leading to her self-initiated change. Blue underwent several rounds of change in belief as well as in practice. The fuses of each round of change were the challenges she encountered, e.g., the English textbooks were too simple for students to learn; finding English vocabulary too difficult for students to remember, students’ resistance to learn extra English; students having problematic learning habits; unsatisfactory academic environment; and unscholarly behavior of teachers in universities. Unlike some other teachers who might bury their dissatisfaction and compromise with the challenges, Blue was resilient, unsatisfied and outspoken, which led her seek solutions and an alternative direction, which is somewhat identical to Bailey’s (Citation1992, p. 271) finding that “teachers experienced dissatisfaction with the status quo,” which contributes to teacher change. However, not every teacher when having dissatisfaction with the status quo can stand up to fight back. In the current study, Blue’s resilience played an important role.

Teacher resilience is a developmental quality or capacity “to successfully overcome personal vulnerabilities and environmental stressors” (Oswald, Johnson, & Howard, Citation2003, p. 50), which helps teachers to “maintain their commitment to teach” (Brunetti, Citation2006, p. 813). Though resilience is not an innate quality, the developmental feature it has owes much to individuals’ dynamic adjustment to challenging contexts (Mansfield, Beltman, Price, & McConney, Citation2012). As Blue told me about the motivation underpinning all her changes: “My purpose has always been to improve teaching and learning;” sticking to this commitment, she overcame the challenges posed to her by dynamic adjustment to the circumstances, in other words, by constant self-initiated teacher change.

Except for the grit aspect of teacher resilience, strategizing is another aspect important to teachers. As Castro, Kelly, and Shih (Citation2010, p. 263) pointed out, teacher resilience also means “specific strategies individuals employ when they experienced an adverse situation.” In other words, teachers have meta-learning skills to find solutions, or at least, they have some clues of how to seek help. Such quality was also revealed in Blue’s case. For example, Blue referred to the input hypothesis in order to increase students’ exposure to English after noticing a deficiency in textbooks; she knew how to learn from psychology experts in order to tackle students’ word memorizing. Blue was also aware of the functionality of social media in engaging students when she was banned from teaching EAP in class. These actions opened vessels for Blue to go on learning.

5.1.2. Teacher CPD learning

Blue reported her two experiences as a visiting scholar, i.e., studying psychology in E university and her literacy studies in the US, as providing her with food for thought in producing changes in her belief and practice. The visiting scholar experience could be seen as a form of continuing professional development (CPD) learning. CPD activities “are aimed … at adding to their [teachers’] professional knowledge, improving their professional skills and helping them to clarify their professional values so that they can educate their students more effectively” (Bolam, Citation2000, p. 267). Previous studies have found participating in CPD training could, to some extent, facilitate teacher change: Similar to Blue’s change after returning from learning in the US, Tse et al. (Citation2012) recorded a group of Taiwan teachers’ inspiration and change after observing Hong Kong teachers’ lessons. Richards et al. (Citation2001) also found that in-service courses or other forms of CPD training were useful in promoting teacher change.

5.1.3. Teacher reflection

Teacher reflection is the catalyst of Blue’s self-initiated change. When external challenges (such as improper textbooks, students’ demotivation, department barriers) occurred to Blue, she always thought deeply about the reasons behind the challenges and deliberated over possible ways out before/while taking any actions, and this process of mental work could be seen as Blue’s reflection. Such reflection actually underpinned all of Blue’s mental and strategic movements in teacher change, connecting all of her understanding of socio-cultural issues and collecting all of her wisdom to figure out the most appropriate English course for her students. Similar to Cheung and Wong (Citation2017, p. 1137) who claimed teacher reflection “is the link connecting various factors of teacher change”.

Based on Van Manen’s (Citation1977) categorization of three levels of teacher reflection (technical, practical, and critical), Cheung and Wong (Citation2017) discovered that the higher the level of teacher reflection their participants had, the higher the chances these participant teachers had to explore new teaching methods, and vice versa. Similarly, Cheung and Wong (Citation2017) found that teachers with lower level (technical and practical level) reflections were inclined to work on students’ knowledge learning, which was similar to Blue’s earlier attempts in changing students’ textbooks and word memory methods. Teachers striving for higher-level reflection (critical level) were proactive in thinking about “worth of knowledge and social circumstances useful for students” and initiative in adopting new teaching methods (Cheung & Wong, Citation2017, pp. 1137–1143). The latter was identical to Blue’s reflection on her students’ learning habits in the academic environment in her university, and her creation of a multiple-literacies-based EAP course. Thus, Blue underwent a lower to a higher level reflection and, thus, teacher reflection has played a key role in Blue’s teacher change.

5.2. How did teacher change happen to blue? What are the characteristics of teacher change in the case of blue?

Unlike the literature that has hypothesized teacher change as a linear process, i.e., either change of belief determined by change of practice (Foley, Citation2010) or change of belief based on the learning outcome of changed practice (Guskey, Citation2002), Blue’s process of teacher change was not a linear process. It was even difficult to distinguish whether Blue’s belief changed first, her practice changed first, or whether changes happened simultaneously. However, this is not important in the current study. Blue’s teacher change developed along with the deepened and broadened reflection about her teaching content, teaching methods, students and other socio-cultural issues.

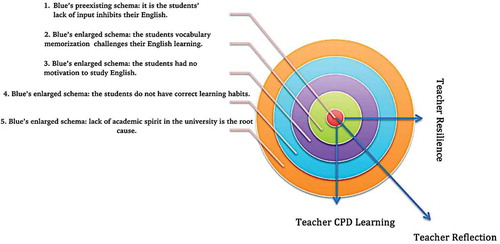

What is noteworthy is that even though Blue eventually developed multiple literacies based on the EAP course, she did not utterly abandon her previous ideas of what it means to be an English teacher. As shown in Table , vocabulary learning was still seriously included in the outline of Blue’s EAP course, which retained the vocabulary learning that was once a key area of her English teaching. Similarly, Blue used to make great efforts in increasing English input for students. Thus, in her EAP course on WeChat, she continued to post authentic English materials to students every day. Blue adopted social media and other online platforms to engage students learning of English, while she also ran a WeChat account teaching students EAP online. It seems that Blue’s change was somewhat an extension of her schema; she built her existing ideas on the new one through constant reflection, teacher learning, and with her resilience. Such a finding is similar to Pajares (Citation1992) and Thompson’s (Citation1992) idea that teachers select new knowledge and build them onto their preexisting schema. While Thompson (Citation1992) did not call such a development teacher change, he said teachers do not change, but supplement original schema when meeting new knowledge.

Perhaps Blue’s story could tentatively provide another angle to look at teacher change, as Figure illustrates: teacher change is a constant widening of preexisting schema like an enlarging concentric circle. Teachers’ original beliefs and practice is extended and supplemented along with their heightened reflections, continuous CPD learning, and a resilience to adjust to the contexts as they go on teaching. Thus, this concentric circle model (based on Blue’s evolution as a teacher) as a whole represents a teacher’s belief and practice of teaching and learning.

6. Implications

Hoban (Citation2002, p. 1) claims “after being presented with a multitude of ideas… many teachers fall into a repetitive pattern of teaching in conventional way they were taught at school,” and indeed, teachers are reluctant to change unless they themselves feel it is necessary and they themselves are the initiators of the change (Richardson, Citation1998). Alternatively, because teachers themselves know their classes and students more than anyone else, they selectively accept new methods introduced to them (Thompson, Citation1992) and merge the selection into their established system of belief and theory (Gregoire, Citation2003). Although there are many research studies exploring the mechanisms of teacher change, including the present study, the mechanisms of teacher change remain elusive. However, locating this mechanism may not be the key; as long as the contributing factors of teacher change and teachers’ selective rendering of change are known, an effective teacher education program can still be developed.

As the present study shows, teacher reflection was the catalyst of Blue’s change. Leading teachers to become reflective practitioners seems very important. Cheung and Wong (Citation2017) have stressed that the higher the level of reflection teachers develop, the more likely they bring change into classrooms. As teaching is such a complex and skills-demanding issue, it always requires teachers’ good judgment about what to teach and how to teach (Pollard et al., Citation2014); it also requires teachers’ constant reflection, even at the technical and practical levels (Van Manen, Citation1977). Apart from considering classroom discourse and wider social influences, teachers as reflective practitioners should also possess “open-mindedness, responsibility, and whole-heartedness” (Pollard et al., Citation2014, p. 116). Such a disposition is also related to some psychological factors of teacher resilience (e.g., Brunetti, Citation2006; Chong & Low, Citation2009; Gu & Day, Citation2007; Sinclair, Citation2008).

Teacher resilience as another factor sustaining Blue to initiate change has also been a target of researchers, but they seldom suggest how to develop teachers’ resilience (Mansfield et al., Citation2012). Teacher resilience is not only determined by logistical factors such as teachers’ workload or school management, but it is also closely related to, for example, altruism (Brunetti, Citation2006; Chong & Low, Citation2009), strong internal motivation (Gu & Day, Citation2007), perseverance and grit (Sinclair, Citation2008), and flexibility (Le Cornu, Citation2009). Therefore, methods to develop teachers’ internal quality or morality should be considered by future researchers and teacher educators.

The third factor that prompted Blue’s self-initiated teacher change, i.e., CPD learning and various kinds of teacher training programs, has been criticized by teacher educators and researchers who doubt its effectiveness in leading to teacher change (Cohen & Hill, Citation2000; Hoban, Citation2002). Thus, researchers and teacher educators should think outside the box and change their expectations of CPD programs. Rather than changing teacher-trainees, they should aim at giving their teacher-trainees suggestions and references, helping them to reflect on their own contexts, and letting them decide the extent to which a certain new method is being adopted. After all, the teachers are relying on their own judgments to survive the complex teaching discourse (Pollard et al., Citation2014).

Blue could be seen as an autonomous teacher in implementing her own self-initiated teacher change. As Richardson (Citation1998) warned: teachers sometimes make changes based on unwarranted assumptions, and “if all teachers make decisions autonomously, the schooling of an individual student could be quite incoherent and ineffective” (Richardson, Citation1998). Thus, perhaps teacher educators, in order to strike a balance between teachers’ autonomy, responsibility, and the community (Richardson, Citation1998) should also teach in a more holistic manner.

7. Conclusion

Teachers find change difficult, and this has long been a challenge of many teacher educators because a principal aim of teacher education programs is to change teachers. Despite the existing studies on teacher change, our understanding of teacher change still needs to be deepened. Blue’s constant self-initiated teacher change might provide readers with another angle to look at teacher change. By answering the two research questions (RQ1. What are the contributing factors to Blue’s self-initiated teacher change? RQ2. How did teacher change happen to Blue? What are the characteristics of teacher change in the case of Blue?), the present narrative inquiry discovered that teacher resilience, teacher reflection and teacher CPD learning were the three most important factors that led to Blue’s self-initiated teacher change. In addition, Blue’s teacher change developed along with her deepened and broadened reflection of her teaching content, teaching methods, and on her students and other socio-cultural issues; rather than refurbishing her entire belief and practice, Blue’s change was a somewhat gradual extension of her schema; she built her new ideas onto the old, through constant reflection, teacher learning, and with her resilience. The present study can provide a different perspective to see teacher change; however, the narrative data came from from only one individual, which may not be representative of other teachers.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yulong Li

Yulong Li is an EdD candidate at the University of Glasgow. He was a lecturer at the Education University of Hong Kong, where he taught and supervised postgraduate students. Yulong maintains a strong interest in educational research. He has publications in the areas of TESOL, EAP, sociolinguistics, teacher development, mobile learning, and education sociology.

References

- Ashton, P. T., & Gregoire, M. (2003). At the heart of teaching: The role of emotion in changing teachers’ beliefs. In J. Raths & A. McAninch (Eds.), Advances in teacher education (pp. 99–15). Ablex, Norwood, NJ: Information Age Publishing.

- Bailey, K. M. (1992). The processes of innovation in language teacher development: What, why and how teachers change. In J. Flowerdew, M. Brock, & S. Hsia (Eds.), Perspectives on Second Language Teacher Education (pp. 253–282). Hong Kong: City Polytechnic of Hong Kong.

- Bolam, R. (2000). Emerging policy trends: Some implications for continuing professional development. Journal of In-Service Education, 26(2), 267–280. doi:10.1080/13674580000200113

- Borg, S., & Liu, Y. D. (2013). Chinese college English teachers’ research engagement. TESOL Quarterly, 47(2), 270–299. doi:10.1002/tesq.2013.47.issue-2

- Brunetti, G. J. (2006). Resilience under fire: Perspectives on the work of experienced, inner city high school teachers in the United States. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(7), 812–825. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.027

- Castro, A. J., Kelly, J., & Shih, M. (2010). Resilience strategies for new teachers in high-needs areas. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 622–629. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.010

- Cheng, A. (2016). EAP at the tertiary level in China: Challenges and possibilities. In K. Hyland & P. Shaw (Eds.), The routledge handbook of English for academic purposes (pp. 208–230). New York: Routledge.

- Cheung, W. S., & Wong, J. L. N. (2017). Understanding reflection for teacher change in Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Management, 31(7), 1135–1146.

- Chinn, C. A., & Brewer, W. F. (1993). The role of anomalous data in knowledge acquisition: A theoretical framework and implications for science instruction. Review of Educational Research, 63(1), 1–49. doi:10.3102/00346543063001001

- Chong, S., & Low, E. (2009). Why I want to teach and how I feel about teaching: Formation of teacher identity from pre-service to the beginning teacher phase. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 8(1), 59–72. doi:10.1007/s10671-008-9056-z

- Cobb, P., Wood, T., & Yackel, E. (1990). Chapter 9: Classrooms as learning environments for teachers and researchers. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, Monograph, 4(4), 125–210. doi:10.2307/749917

- Cohen, D. K., & Hill, H. C. (2000). Instructional policy and classroom performance: The mathematics reform in California. Teachers College Record, 102(2), 294–343. doi:10.1111/tcre.2000.102.issue-2

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2000). Narrative understandings of teacher knowledge. Journal of Curriculum and Supervision, 15(4), 315–331.

- Craig, C. (2007). Story constellations: A narrative approach to contextualizing teachers’ knowledge of school reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(2), 173–188. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.014

- Creswell, J. (2012). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

- Dole, J. A., & Sinatra, G. M. (1998). Reconceptalizing change in the cognitive construction of knowledge. Educational Psychologist, 33(2/3), 109–128. doi:10.1080/00461520.1998.9653294

- Fennema, E., & Franke, M. L. (1992). Teachers’ knowledge and its impact. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 147–164). New York: Macmillan.

- Foley, Y. (2010). Using a multidimensional approach to meet the reading literacy needs of EAL pupils. NALDIC Quarterly, 7(2), 1–14.

- Fullan, M. G. (1991). The new meaning of educational change. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Gajek, K. (2014). Auto/narrative as a means of structuring human experience. In M. Kafar & M. Modrzejewska-Swigulska (Eds.), Autobiography-biography-narration research practice for biographical perspectives (pp. 11–32). Krakow, Poland: Jagiellonian University Press.

- Gebhard, J., Gaitan, S., & Oprandy, R. (1990). Beyond prescription: The student teacher as investigator. In J. C. Richards & D. Nunan (Eds.), Second language teacher (pp. 14–25). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Geertz, C. (2000). Local knowledge: Further essays in interpretive anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

- Gregoire, M. (2003). Is it a challenge or a threat? A dual-process model of teachers’ cognition and appraisal processes during conceptual change. Educational Psychology Review, 15(2), 147–179. doi:10.1023/A:1023477131081

- Griffin, G. A. (1983). Introduction: The work of staff development. In G. A. Griffin (Ed.), Staff development, eighty-second yearbook of the National society for the study of education (pp. 48-55). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gu, Q., & Day, C. (2007). Teachers resilience: A necessary condition for effectiveness. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1302–1316. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.006

- Guskey, T. R. (1985). Staff development and teacher change. Educational Leadership, 42(7), 57–60.

- Guskey, T. R. (1986). Staff development and the process of teacher change. Educational Researcher, 15(5), 5–12. doi:10.3102/0013189X015005005

- Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8(3), 381–391. doi:10.1080/135406002100000512

- Guskey, T. R., & Sparks, D. (1996). Exploring the relationship between staff development and improvements in student learning. Journal of Staff Development, 17(4), 34–38.

- Hadley, G. (2015). English for academic purposes in neoliberal universities: A critical grounded theory. London and New York: Springer.

- Hoban, G. F. (2002). Teacher learning for educational change. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Holland, J., Ramazanoglu, C., Sharpe, C., & Thomson, R. (1998). The male in the head: Young people, heterosexuality and power. London: Tufnell Press.

- Krashen, S. D. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London: Longman.

- Le Cornu, R. (2009). Building resilience in pre-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 717–723.

- Lee, I. (2014). Publish or perish: The myth and reality of academic publishing. Language Teaching, 47(2), 250–261. doi:10.1017/S0261444811000504

- Lewin, K. (1935). A Dynamic Theory of Personality. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Liu, Y. (2011). Professional identity construction of College English teachers: A narrartive perspective. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- Liu, Y., & Xu, Y. (2011). Inclusion or exclusion? A narrative inquiry of a language teacher’s identity experience in the ‘new work order’ of competing pedagogies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 589–597. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.10.013

- Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Price, A., & McConney, A. (2012). “Don’t sweat the small stuff:” Understanding teacher resilience at the chalkface. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(3), 357–367. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.001

- O’Reilly, K. (2008). Key concepts in ethnography. London: Sage.

- Oswald, M., Johnson, B., & Howard, S. (2003). Quantifying and evaluating resilience- promoting factors: Teachers’ beliefs and perceived roles. Research in Education, 70(1), 50–64. doi:10.7227/RIE.70.5

- Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. doi:10.3102/00346543062003307

- Pollard, A., Black-Hawkins, K., Hodges, G. C., Dudley, P., James, M., Linklater, H., … Wolpert, M. A. (2014). Reflective teaching in schools. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Posner, G. J., Strike, K. A., Hewson, P. W., & Gertzog, W. A. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66(2), 211–227. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1098-237X

- Richards, J. C., Gallo, P. B., & Renandya, W. A. (2001). Exploring teachers’ beliefs and the processes of change. PAC Journal, 1(1), 41–58.

- Richardson, V. (1998). How teachers change? What will lead to change that most benefits student learning? Focus on Basics, 2(c). Retrieved on from http://ncsall.net/index.html@id=395.html

- Sinclair, C. (2008). Attracting, training, and retaining high quality teachers: The effect of initial teacher education in enhancing student teacher motivation, achievement, and retention. In D. M. McInerney & A. D. Liem (Eds.), Teaching and learning: International best practice (pp. 133–167). Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age Publishing.

- Sowder, J. T., Philipp, R. A., Armstrong, B. E., & Schappelle, B. P. (1998). Middle-grade teachers’ mathematical knowledge and its relationship to instruction: A research monograph. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Stein, M. K., Grover, B. W., & Henningsen, M. (1996). Building student capacity for mathematical thinking and reasoning: An analysis of mathematical tasks used in reform classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 33(2), 455-488.

- Tam, A. C. F. (2015). The role of a professional learning community in teacher change: A perspective from beliefs and practices. Teachers and Teaching, 21(1), 22–43. doi:10.1080/13540602.2014.928122

- Thompson, A. G. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and conceptions: A synthesis of the research. In D. A. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 127–146). New York: Macmillan.

- Trigueros, M., & Lozano, M.-D. (2015). Teacher change: Ideas emerging from a project for the teaching of university mathematics. Teaching in Higher Education, 20(7), 699–710. doi:10.1080/13562517.2015.1069265

- Tripp, T. R., & Rich, P. J. (2012). The influence of video analysis on the process of teacher change. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(5), 728–739. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.01.011

- Tse, S. K., Ip, O. K. M., Tan, W. X., & Ko, H. W. (2012). Sustaining teacher change through participating in a comprehensive approach to teaching Chinese literacy. Teacher Development, 16(3), 361–385. doi:10.1080/13664530.2012.722439

- Tsui, A. B. M. (2007). Complexities of identity formation: A narrative inquiry of an EFL teacher. TESOL Quarterly, 41(4), 657–680. doi:10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00098.x

- Van Manen, M. (1977). Linking ways of knowing with ways of being practical. Curriculum Inquiry, 6(3), 205–228. doi:10.1080/03626784.1977.11075533

- Xu, S., & Connelly, F. M. (2009). Narrative inquiry for teacher education and development: Focus on English as a foreign language in China. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(2), 219–227. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.10.006