Abstract

The aim of the study has been to describe, analyse and discuss the latest research findings on the professional development that is accomplished through collective and cooperative processes among teachers. The research question addressed in this article is: “In which ways do professional development and learning occur in schools, and which improvements may be identified in the practices of teachers related to professional development and learning?”. The theoretical framework for the research is cultural historical activity theory (CHAT). In the CHAT perspective, knowledge is perceived as constructions of meaning and understanding within social interaction. The social interactions and surroundings are seen as decisive for teachers’ (in this case) learning and development. The main argument is that teachers’ professional development can lead to improvements in teachers’ teaching and development of teachers’ pedagogical thinking about students learning and development. To answer the research question, a search was carried out in the field of pedagogy in ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) (performed on 4 January 2018). The search strings “teacher professional development”, “teacher learning” and “professional development” were used and restricted to the time period from 2015 to 2017. This study finds that many factors impact and influence the professional development of teachers. Collective processes in professional learning communities (PLCs) in an environment dominated by trust between the participants are important. Findings moreover show the importance of teachers having influence on planning and initiation of teachers’ professional development. The study also shows that external support has an impact on teachers’ professional development.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This review article focuses on teachers’ collective professional development in school. The article presents research from 23 articles from 2015 to 2017. The articles this review is based on are from four continents with nine taking place in Europa, seven in America, four in Asia, and three in Australia. The research question on which this research is based is twofold. First, I wanted to look more closely at and describe the ways in which teachers’ collective professional development occurs in school. Second, I was interested in finding out what improvements can be identified in the teachers’ practice as a result of professional development. Findings in the study show that there are several factors that influence teachers’ collective professional development. These are structural and cultural conditions of the schools, the intervention’s or the project’s design, collaboration between external resource persons and teachers, and several contextual factors.

1. Introduction

This review article explores the professional development and learning of teachers and examines the opportunities teachers have to learn at their workplace. Teachers’ professional development refers to teachers’ learning, how they learn and how they apply their newly acquired knowledge in practice (Avalos, Citation2011). The definition corresponds to Pedder and Opfer (Citation2011), who state that teachers’ professional development and learning is about the growth and development of teachers’ expertise that lead to changes in their practice to enhance the learning outcome of students. Evans (Citation2010) defines changes in teachers’ practice as changes in knowledge, understanding, skills, behaviour, attitudes, values and convictions.

Research indicates that when teachers’ professional development is contextualized to practice and when opportunities for collective development are created, this is a good approach that can support teachers’ professional development and create improvements in their teaching practice (Darling-Hammond & Richardson, Citation2009). Darling-Hammond and Richardson (Citation2009) also state that when schools support teachers with well-designed, engaging and meaningful professional development opportunities, the teachers will be more able to create the same opportunities for learning and development for their students. Teachers’ professional development is generally based on formal approaches, such as professional development programmes, mentor schemes, courses and workshops and introductions to new methods and techniques (Kennedy, Citation2005; Timperly, Citation2011). According to Kennedy (Citation2005), formal approaches are often determined in advance and there are few opportunities for teachers to be actively involved and participatory in their own learning process (Pedder & Opfer, Citation2011). Teachers can also learn through interactions that occur when teachers teach together, when they collaborate on planning (Little, Citation2012) and through pedagogical discussions about students and teaching (Postholm, Citation2012). This review article focuses on teachers’ professional development and learning in school that takes place in dynamic and on-going processes through interaction in collective processes between the teachers (Little, Citation2012; Timperly, Citation2011). Development and learning are contextualized to the teachers’ practice and take place over time, and according to Fullan (Citation2007) it is only when professional development is contextualized to teachers’ practice that changes in teaching practices can be created. This article excludes isolated activities such as introduction to new programmes or methods and workshops, and rather focuses on the schools’ and teachers’ practice as the basic environment for teachers’ development and learning (Vescio, Ross, & Adams, Citation2008).

While many research findings suggest that teacher collaboration and collective processes contribute to professional development and improvements in teaching (Desimone, Citation2009; DuFour & Fullan, Citation2012¸ Garet, Porter, Desimone, Birman, & Yoon, Citation2001), some research also indicates that schools and teachers are struggling with creating constructive and meaningful interactions between teachers where the aim is to create development and learning (Biesta, Priestley, & Robinson, Citation2015; Bridwell-Mitchell, Citation2015; Van Es, Citation2012). If teachers are to learn together and create development through collaboration and collective processes, the focus cannot be only on the structure of the collaboration and processes, but according to Forte and Flores (2014) it must be an interplay between structure and culture. A culture of learning must be created, and according to Walker (Citation2007), a positive learning culture for teachers depends on the presence and alignment of three different factors: structures, values and relationships. In this context, culture refers to the different ways a group of people act and the beliefs they connected to these actions (Wolcott, 2008). Dobie and Anderson (Citation2015) emphasized the importance of having an open culture where it is permissible to express disagreements, which are important for constructive dialogues, learning and development in teacher collaboration.

Pedder and Opfer (Citation2011) point out that professional development is part of a complex system, and it is necessary to be aware of this complexity when school’s initiate development projects. The complex system involves individual teachers, interactions between teachers, the school as a system and interactions between teachers and the school as a system and the school leaders. In this complex landscape, professional development is seen as constituting processes of learning that lead to the development and greater expertise for teachers. With such an understanding of professional development and learning, the processes will be situated in the teachers’ practice and influenced by many situational factors in the complex system which can support or impede changes in practice. Even though the interest in and popularity of collaboration between teachers and collective learning is growing, some research shows that the changes in practice are small and that major changes rarely occur (Biesta et al., Citation2015; Ermeling & Yarbo, Citation2016; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). Vangrieken, Dorchy, Raes and Kyndt (Citation2015) say that collaboration between teachers creates several benefits with significant impact on their professional development and is thus viewed as an important strategy and approach to teachers’ professional development. This is also emphasized in the International Survey on Teaching and Learning (TALIS) (2013), who found that teachers using collaborative practices are more innovative in their teaching, higher satisfaction at work, and hold stronger self-efficacy beliefs (European—Commission, Citation2013).

The research question guiding this review study is twofold: “In which ways do collective professional development and learning occur in schools, and which improvements can be identified in the teachers’ practice?” The aim of the study is to examine and describe findings in recent research and to analyse and discuss the findings related to the research question. First, the following section presents the search strategy for the included research studies. The methodology section also includes the analysis strategy. I then present Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) as a theoretical framework and as a framework for analysis and discussing the findings, before presenting the findings of the study. The theory underlines collective development and is therefore relevant as a theoretical perspective in research considering teachers’ collective professional development. In the analysis and discussion section, the findings presented will be analysed and discussed considering the relevant theory. The article ends with some concluding remarks. In the analysis and discussion, I will also introduce research which supports the findings of the study, but which was not highlighted in the theoretical framework.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search strategy

To answer the research question, I have undertaken searches in the field of pedagogy in ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) (performed on 4 January 2018). The search strings used were “teachers’ professional development”, “teacher learning” and “professional development”, restricted to the time period from 2015 to 2017. Furthermore, “primary education” and “secondary education” were chosen as the school levels for this search. This gave me an overview of published research on teachers’ collective professional development in international periodicals. As I was most interested in finding published articles dealing with teachers’ professional development in general, fields such as “teacher education”, “newly trained teachers”, “learning using technological aids”, “mentor schemes” and “special teaching” were deselected. The search yielded 357 hits. As the title of this article indicates, the focus is on teachers’ professional development in school through collective and collaborative processes. Based on these choices, and after reading the abstracts of the identified articles, I selected a set of 173 articles for thorough reading. After reading the 173 articles, 23 articles were chosen based on this study’s research question and focus, exclusion and selected criteria. Of the selected articles, seven were from 2015, 12 from 2016 and four from 2017. The published studies came from four continents with nine taking place in Europa, seven in America, four in Asia, and three in Australia. The selected articles provide a broad and deep insight into the two-folded research question that seeks answers in which ways teachers’ collective professional development and learning in school occurs and which improvements can be identified in their practice.

2.2. Analysis strategy

When examining the articles, the intention was to highlight the main findings presented in the studies. To develop an understanding and overview of the articles, the content was structured and reduced by coding and categorizing the texts in selective, open and axial analysis processes as described by Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998) in the constant comparative analysis method. The selective analysis process is about identifying a core category. In this study, the core category, teachers’ professional development in school had been chosen in advance. When the core category was predefined, I had to search in the selected articles to fill this category with content. Strauss and Corbin (Citation1990) say that new content can fill predefined categories with new content when using the constant comparative analysis method. The open analysis process formed the basis for three main categories on the same horizontal level: 1) Structural and cultural matters, 2) Design and influence, and 3) Teachers as agents.

The first main category which covers structural and cultural matters in the schools is related to various factors which contribute to and impede teachers’ learning and development. Structural matters are related to such factors as time, resources, workloads and external support. The cultural matters are related to such factors as culture for learning, culture for collaboration and collective processes, goals for shared school visions and trust between teachers and between teachers and leaders. The second main category, design and influence, is related to approaches to the professional development of teachers, the planning and initiation phase, observation and outcome of interventions and teacher orientation relating to students as learners. The final category, teachers as agents, is related to professional identity, teachers’ professional growth and agency in development processes.

In the axial coding process the goal is to specify and define a category, and by finding specific traits in the main categories we can form sub-categories. To pinpoint the sub-categories for each of the three main categories I asked questions about when, how, under what conditions and what does it lead to (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990, Citation1998). These questions structured the descriptions of information in the articles and contribute to creating relations between the main categories and their sub-categories (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990, Citation1998). This study focuses on collective professional development in school so the question when was decided in advance. The question under what condition provides information on the context of the studies, and which structural and cultural assumptions should underpin teachers’ professional development. Most of the selected studies are qualitative studies, and the findings therefore present situational knowledge that must be understood in a contextual setting (Wolcott, Citation2008). By asking how, I provide a description of the activity that contributed to professional development.

In addition to the selective, open and axial analysis process, I have used CHAT and the activity system to analyse and discuss the findings. The first analyses conducted by using the constant comparative method, can according to Charmaz (Citation2014) creates the scale for further analysis. To pursue the analysis across the selected studies, I employed CHAT and the activity system. Through this new layer of analyses (including the axial coding process), central sub-categories emerged under each main category that I will highlight in the findings section. Furthermore, I will describe CHAT and the activity system before I present the articles’ findings based on the previously mentioned categories.

3. Cultural historical activity theory

Cultural historical activity theory (CHAT), developed by Leontiev (Citation1981, 1981), is based on Vygotsky’s thoughts and ideas (Wertsch, Citation1981). In the West, the approach that is based on Vygotsky is called socio-cultural theory. CHAT and socio-cultural theory therefore have the same origin, and both theories emphasize the social surroundings as the basis for development and learning. Socio-cultural theory focuses on mediating actions. In addition to these, culture and history also have important roles in CHAT when attempting to understand and maintain development and learning (Engeström, Citation1999). CHAT finds that internalization and externalization processes are present on all levels of human activities (Engeström, Citation1999; Leontiev, Citation1981). Learning is, according to Vygotsky (Citation1978), a process that starts on the social and external level before learning has been internalized in the individual. Learning on the individual level should be supported within the individual’s zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, Citation1978). By extending Vygotsky’s definition of the zone of proximal development, Engeström (Citation1987) has defined it as follows: “it is the distance between the present everyday actions of the individuals and the historically new form of the societal activity that can be collectively generated […]” (p. 174). With such a definition Engeström clearly stakes out the link between the internalization and externalization processes and emphasizes the collective importance of development. In CHAT Engeström and Sannino (Citation2010) have also developed the concept of expansive learning, which they relate to externalization and creative processes. This means that teachers in collective communities are willing to change and explore their own practice, where they can see opportunities and create something new “that is not there yet” (p. 2).

According to Leontiev (Citation1981), activity is prominent in CHAT, and it may be analysed on three distinct levels: activity, action and operation. In CHAT the importance of goals and actions targeting an object is also underlined, as is the fact that the goals should not be separate from but rather part of the learning and development process. According to Leontiev (Citation1981), what distinguishes one activity from another is their objects, or in Leontiev’s words: “the object of an activity is its true motive” […] (p. 62), and it is therefore the object which motivates and controls the activity itself. An activity exists in action, or to contextualize it to school, we may say that school activities exist in the school’s actions (Leontiev, Citation1981). The activity is realized through actions or a chain of actions which are stimulated by the motive for the activity which is focused on an object. This means that the activity (for example, teaching) represents the motive behind the actions that take place. The actions represent intermediate steps towards the object itself, and the actions are carried out by means of different operations (Leontiev, Citation1981). The operations are then related to the conditions and circumstances where the actions take place, which may give limitations or opportunities for approaching the goal. According to Leontiev (Citation1981), actions occur on the individual level, while activity occurs on the collective level.

Tensions and contradictions are potential sources of development and change, and a driving force in CHAT (Engeström, Citation2001; Engeström & Sannino, Citation2010; Virkunnen & Newnham, Citation2013), and these tensions and contradictions can be made visible by using the activity system as the analysis unit. Engeström and Sannino (Citation2011) give as the rationale that contradictions cannot be solved by combining opposite alternatives, they must be solved by creating something new, or to use their term “thirdness”. The idea of thirdness refers to creating something new and pushing the activity system into a new development phase. In development projects in CHAT where there is research collaboration between researcher and participants, the researcher can be considered a formative interventionist, and may provoke tensions and contradictions by creating and using “mirror data” (Cole & Engeström, Citation2007), functioning as a “collective mirror” for the participants and their practice (Engeström, Citation2000). In this review, CHAT forms the basis of the analysis across the selected articles.

3.1. The activity system

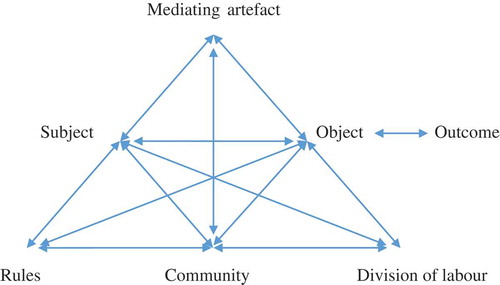

Leontiev developed Vygotsky’s socio-cultural theory while CHAT formed the basis of the activity system theory (Engeström, Citation1987, Citation1999; Engeström & Miettinen, Citation1999). Engeström’s (Citation2001) extension of Vygotsky’s basic triangle (Citation1978), consisting of mediating artefact, subject and object, shows the collective dimension of an activity system. It also shows the close connections between the subject and the social and cultural context, as shown in Figure . The factors that constitute the activity system are “subject”, “mediating artefacts”, “object”, “division of labour/roles”, “community”, “rules” and “outcome”. The upper triangle in the activity system, consisting of “subject”, “mediating artefacts” and “object”, is described as the action triangle (Postholm, Citation2012). The three lower triangles consisting of “rules”, “community” and “division of labour” are the context the actions take place in. Rules include norms and regulations which control the choice of actions in the activity system. Community is the group of individuals interested in the same object or overriding goal. The concept of division of labour makes it possible to distinguish between collective and individual work, and it implies that the work or goal-directed actions are divided between, and conducted by people belonging to the community (Engeström, Citation1987, Citation2001).

Figure 1. The complete activity system (Engeström, Citation1987).

By adding the factor rules, community and division of labour/roles, Engeström (Citation1987, Citation1999, Citation2001) highlights the social aspect of the activity, where an analysis of the interactions between these factors is necessary. The activity system hence becomes an analytical tool that makes the system perspective and participant perspective complementary factors (Engeström & Miettinen, Citation1999). The close connections between the context and the acting subject (which can be either an individual or a group of teachers) shows that context is not reduced to just something that surrounds, but the context is interwoven in the actions taking place, and actions exist only in relation to the context, which is visualized through the three lower triangles in the activity system, Figure , (Cole, Citation1996).

4. Findings

In order to answer the twofold research question in which ways teachers’ collective professional development and learning occur in schools and which improvement can be identified, I developed three main categories. The aforementioned new layer of analysis resulted in important sub-categories under each main category. The developed main categories, with associated sub-categories, form the basis for the presentation of the findings.

4.1. Structural and cultural matters

4.1.1. Time and resources are important but not decisive

In a Dutch interview study with 31 teachers in lower secondary school focusing on the teacher’s perceptions of workplace conditions and how these relate to the teachers’ goals for professional development, Louws, Meirink, van Veen, and van Driel (Citation2017) point out that the structural matters are not as important as cultural matters and leadership in relation to the teachers’ professional development. Structural matters such as resources and time are important but not decisive for the outcome of professional learning. Cultural matters, such as the collaborative culture between teachers (and leaders), collective decisions, goals for shared school visions and an open school culture are highlighted as important factors for professional learning. In a Finnish survey study of 2310 teachers in primary schools, Soini, Pietarinen and Pyhältö (Citation2016) found that it is not enough to create time and resources for increased collaboration and collective processes between teachers and then expect that learning and development will then blossom between the teachers. Findings in this study suggest that spending time on creating a good learning and collaborative culture, where the teachers perceive themselves as professional agents in their own learning process, and where they believe that they may contribute to change and improvement, is important for teachers’ professional development.

In an American study, Takahashi and McDougal (Citation2016) have examined factors that need to be present so that Lesson Study (LS) can have positive influence on teachers’ learning and development. In a pilot study of 15 schools, where they focused on five primary schools and structural factors, they point out that it is important that the school leaders allocate time to implement LS, and that they reduce other duties and tasks. They point out that LS should not come on top of all the other duties teachers have.

In an Irish study, King (Citation2016) has attempted to determine what the necessary factors are for supporting teachers’ professional development and learning that create changes in practice. The study has been conducted among five schools, where each school constitutes a case. Findings in the study show that time must be allocated for collaboration and that this time should be entered in the timetable, but also that allocating time is not in itself enough. Teachers must also be given support in how to use this time efficiently and in a focused way (King, Citation2016).

4.1.2. Trust between teachers and between teachers and school leaders

In a qualitative study of 51 teachers from four primary schools, Hallam, Smith, Hite, Hite, and Wilcox (Citation2015) have examined how trust between teachers influences teacher collaboration and on professional learning communities (PLCs). Their findings show that trust between teachers is a requirement for success in teacher collaboration and PLCs, and when teachers trust each other a strong social supportive resource is created that opens for reflective dialogues. Teachers will then dare to make critical utterances, will dare to point at weaknesses, and a more open culture can contribute to deprivation of teachers’ practices. The study also shows that trust in collaborative teams is developed when the participants successfully complete the assignment and responsibility they have, and when they show mutual friendliness and patience. Findings in the study also suggest that assessing trust and increasing the number of targeted actions to strengthen the collaboration contributes to nurturing trust between the teachers. A Danish study (Andresen, Citation2015) based on 622 focus-group interviews of teachers who have used the LP model (Learning environment and Pedagogical analysis) also underlines the importance of building good relations and trust between the teachers. The clearest finding in this study suggests that the teachers were positively influenced by the collaborative development of competences and professional identity in an environment and atmosphere consisting of trusting colleagues. In this study, the teachers also state that reflections and discussions became more exploratory in an environment dominated by trust. Ning, Lee and On Lee (Citation2016) have conducted a quantitative study in Singapore with 1739 teachers from 28 primary schools and 28 lower secondary schools where they attempt to identify typologies of PLCs based on the values for and engagement in teachers’ professional learning. Findings in the study suggest, similarly to the study by Hallam et al. (Citation2015), that values such as mutual trust and openness between the participants in PLCs had positive effect on teachers’ development and learning. Moreover, findings in the study indicate that an established trust relationship in PLCs based on openness and confidence, where participants dare to join critical discussions and ask questions about the existing practice, creates a positive effect on the individual and collective level of engagement in the professional learning community. In PLCs where no mutual relationship of trust has been established, findings in the study show less engagement in collaborative learning and weaker reflective discussions of the participants.

King (Citation2016) shows that the engagement and involvement of the school leaders is important for teachers’ professional development, and that trust in these processes is key. Takahashi and McDougal (Citation2016) also show that if the head of school clearly communicates his or her enthusiasm to others in the leadership team and to the teachers (and other stakeholders) it will be a significant resource for development activities, contributing positively to the relationship of trust between teachers and the leadership team.

Hallam et al. (Citation2015) have found that the behaviour of the head of school influences teachers’ motivation and on teachers’ learning and collaboration in school, and that this may be linked to trust. The trust the head of school has in the teachers, are positively related to the trust teachers have in their colleagues. The study also finds that the head of school can focus on the importance of trust by being open and inclusive when new teacher teams are composed. This corresponds to findings by Louws et al. (Citation2017), who also find that school leaders should remain aware of how teachers experience the learning environment in the school and how this has impact on the learning and collaborative environment for the teachers. Louws et al. (Citation2017) show that this is a matter of mutual trust between school leaders and teachers.

4.1.3. External support

The study by Takahashi and McDougal (Citation2016) points to the importance of schools connecting to external support persons who have experience with LS, or persons they describe as knowledgeable others.Footnote1 Important functions for external resource persons will be to facilitate and organize the LS work, to be supporting players during the various phases of LS, and to give lectures and make comments on the teams’ research meetings. Another important task for the knowledgeable other or the external is to indicate the next step in the teachers’ work and discuss together with the teacher’s appropriate approaches. An Australian interview study (Widjaja, Vale, Groves and Doig, Citation2015) with a focus on teachers’ professional growth after having used LS, also shows that external support has positive impact on teacher development. Findings in the study show that external support from experts with broad knowledge and experience of LS was very important for the learning and development of the participants. LS was a new method for the teachers for organizing their collaboration and working on problem-solving tasks was also new to them. Findings in the study show that the external support played a significant role when designing problem-solving tasks, finding an observation focus and creating good and meaningful discussions between the teachers.

Gonzàlez, Deal and Skultey (Citation2016) have carried out a qualitative study using video analysis of a study group with five teachers. Ten video-analysis sequences were analysed over a period of 10 months, where the focus was on the practices and actions the researcher introduces to facilitate for and create high-quality discussions between the teachers. There are two findings from the study that I would like to highlight because they show the importance of external support. First, the findings show that the external support persons should not adopt a neutral position but rather contribute arguments outlining their understanding of the events in the video recording which may lead to agreement and disagreement in the study group. The aim is that this discussion might open for other ways of studying the recording. Second, findings show that the quality of the discussions rose when the external person did not only limit the dialogue to a discussion on the observations in the video recordings, but also opened for relations to be made between the observations and the next teaching session. The researchers in this study say that when external resource persons manage to open discussions where different representations of teaching can take place and that they are linked to students’ learning and thinking, a good foundation is created for high-quality discussions.

In Visnovska and Cobb’s (Citation2015) 5-year study of 12 lower secondary teachers from six different schools and two external mathematics experts in the USA, they examined how teachers’ development of their teaching practice corresponds to supportive teaching in the full class, and how this can be supported and developed. The study points out that the foremost duty of the expert is to link the teachers’ actions, comments and questions in teaching situations to overriding educational issues (such as when do you make a decision to stop—when do you make decisions to proceed—where can you get them turn it up a notch and challenge the students—who do you take into consideration). Findings in the study also show that by relating the actual actions to overriding questions, the external expert can introduce new perspectives, facilitate new dialogues and ask questions which challenge the teachers’ thinking.

4.1.4. Collaborative or collective learning

In a quantitative study, Meijs, Prinsen, and de Laat (Citation2016) gave 110 Dutch teachers a questionnaire to ascertain their attitude to social learning and whether they see it as suitable for teachers’ professional development. Results from the study show that 30% were very positive to it, 66.4% were somewhat positive and 3.6% answered that social learning did not suit them. Almost all the teachers indicated that they liked to collaborate with others to improve their knowledge, and the researchers concluded that social learning is an approach to professional development which suits teachers well. In a school district in Canada where all the schools and the teachers were ordered to work with PLCs as the approach to teachers’ professional development, Kelly and Cherowski (Citation2015) conducted a case study where they followed one of the schools throughout one school year. The researchers point out that the PLCs were presented and controlled from the school-district administration, and claim that little preparation was done to understand what it means to work in a PLC. Even if the teachers had positive experiences in the various professional learning communities, findings from the study show that there is a need to establish a culture for social and professional learning among the teachers. The authors also found that whether PLCs are perceived as positive or negative is in many ways dependent on the existing culture for collaboration in the school.

In an Australian case study in three innovative schools, Owen (Citation2015) examined the teachers’ professional development by engaging in professional learning communities where the action-learning method was used. Findings from the study show that the teachers emphasize the importance of the team in PLCs. The collective work contributed to changing the teachers’ convictions and to developing common values. Moreover, findings show that the collaborative processes towards embracing new ideas and creating new teaching actions contributed to collective learning in the teacher teams. The teachers’ greatest “epiphany” occurred when they planned new activities and taught/observed together, and particularly when they discovered that what they had planned became too dull and unchallenging for the students, acknowledging that they needed to do something else.

4.2. Design and influence

4.2.1. The teachers’ influence on planning of design and the initiation phase

King (Citation2016) points to findings relating to systemic factors which support or impede implementation of new ideas and which determine whether this is lasting and becomes part of the school’s culture. Findings in the study show that to achieve the best possible conditions for the teachers’ professional development, the design of the innovation must be viable, focused, highly structured and labour friendly/applicable, and it must have a clear framework. King (Citation2016) finds that the importance of the design and the approach should reflect the importance of working with teachers on their skill level and according to their previous knowledge. When the purpose of professional development is to change the practices of the teachers, which King (Citation2016) calls a third-order activity, findings in the study show that in the design and initiation phase it is important to understand how professional development of third-order activity can be supported and understood. She also points out that in the design of the innovation the focus and planning should be directed more on the result and desired impact of the innovation, the outcome, and that the teachers should be included in this process, as this may contribute to a clearer direction and a better result.

Takahashi and McDougal (Citation2016) draw attention to the importance of the initiation phase when schools embark on development projects, and they try to explain why LS projects do not always enjoy the same level of success outside Japan. They believe that much of the explanation can be found in the fact that when Japanese teachers start with LS, they must: 1) study LS as a method thoroughly, 2) read relevant research and theory on the subject field they are focusing on, and 3) examine available curriculum and material or artefacts in advance of and during the processes. They believe that this is highly important if the participants are to know exactly what they are embarking on and what is expected of them, and if they are to obtain a broader insight into and overview of the topics they will be focusing on. Takahashi and McDougal (Citation2016) state that these requirements are far more prominent in Japan than in Western countries when introducing LS as a method for teachers’ professional development. They also point out that the project’s design must have support functions, internal and external, and the processes in the project must feature a progression that is clear to both teachers and leaders. When LS and similar projects are school-based, Takahashi and McDougal (Citation2016) point to the importance of the school having prepared an overriding research question and goal which will be the governing force for the work in the various teacher teams. It should not be governing in the sense of choice of methods or the use of artefacts but in the sense of giving the project a direction to move in.

Findings in the study by Owen (Citation2015) show that an innovative approach involving thinking in new ways about teaching and learning and testing ideas about teaching had a positive effect on the learning of both teachers and students. Furthermore, the findings show that it is important that teachers have influence on the design of innovations and that they take part in planning the interventions. This created an understanding of the responsibilities of the teachers relating to other team members, and an understanding of shared leadership and division of labour. Not least, it created a shared desire to change and improve practice through innovative research in collective processes.

4.2.2. Focus on students as learners in the teachers’ professional development

In his study, Doecke (Citation2015) has considered the link between storytellingFootnote2 and teachers’ professional development. He claims that teachers’ discussions and dialogues about what creates meaning for students in their learning processes contribute to changing the focus on teaching and learning from being teacher oriented to being student-oriented. Findings from the study show that this approach may contribute to developing a reflective awareness about the teaching of teachers and about students as learners. A Finnish survey study (Soini et al., Citation2016) shows that if teachers do not see students as active participants in the construction of the learning environment in the classroom, or as active participants in their own learning process, the students’ opportunities for meaningful learning will not only be reduced, but this may also impede the teachers’ development. This finding is supported by an American study by Wilson, Sztajn, Edgington, Webb and Meyers (Citation2017), which examines the discussions about teachers in a professional development setting on the learning trajectories (LTs) of students in mathematics. Their aim was to examine whether the teachers’ discursive patterns about students as learners change by engaging in the students’ learning trajectories. Findings in the study show that teachers tend to focus on what students do not understand and are unable to do, and then may make definitive evaluations and claims about what they can do and what they cannot do. Teachers also often refer to students as performing low or high, or under or above the class average. Discursive patterns which explain academic results by explaining that they are inherent in the students contribute to reinforcing the belief that some students can learn, and some cannot (Wilson et al., Citation2017). Wilson et al. (Citation2017) show in the study that by focusing on and changing the discourse to be about students as learners, the teachers stated that this increased their sense of ownership in the teaching and they were then better equipped to develop teaching practices that would coax out the students’ thinking and ideas. Findings in the study also show that it was necessary to change patterns and ways of discussing students as learners in order to develop learning opportunities of both teachers and students. Wilson et al. (Citation2017) also point out that the lack of specific norms and ways of discussing students as learners contributed to limiting the effect of the development of teachers and argue that it is necessary to establish specific ways of discussing matters to create a clearer focus and encourage discussions on students as learners.

The study by Visnovska and Cobb (Citation2015) points out that even if teachers participate in professional development projects, it is difficult to understand students thinking, and what they actually have understood. The study highlights the usefulness of considering the practices of teachers on two different levels. One level is what actually occurs due to actions in the classroom, which is described as online activities, and the second level is what occurs outside the classroom in the form of individual and collective planning, analysis of students works, diagnosis of students understanding and thinking and prediction of planned activities, which is described as offline activities. The researchers discovered that teachers who participated in the study found it difficult and challenging to work on the offline level. They found that the teachers lacked good methods and patterns for conducting student-oriented discussions which would capture students’ thinking, prior knowledge, understanding, ideas and engagement. This also corresponds to findings in Wilson et al. (Citation2017).

Four experienced teachers participated in a qualitative study conducted by Witterholt, Goedhart, and Suhre (Citation2016) in a Dutch primary school over a period of six months. The purpose of the study was to examine and develop teaching practice by focusing on inquiry-based activities in the teaching. When they started, all the teachers used traditional methods based on textbooks and teacher-oriented practice, and they had little or no experience with inquiry-based teaching. Findings show that changes occurred in two of the teachers. The changes were related to going from focusing on the teacher’s perspective in the teaching to focusing on the students’ perspective, and from focusing on the tasks in the textbooks to focusing on how to guide students’ learning by designing good tasks and refining their own teaching. The other two teachers were unable to cast aside previous patterns where the teaching mainly was based on the textbook. Witterholt et al. (Citation2016) state that the readiness of the teachers, or being ready for inquiry-based teaching, was influenced by two essential factors: first, the teachers’ practical knowledge, and second, which view teachers have on students as learners and students as active in their own learning process. Owen (Citation2015) shows that having a positive attitude to students as learners contributes to changes and improvements in the teaching. Her findings show that through joint planning and teaching, the teachers became more aware of how and which type of tasks gave the students the opportunity to work as explorers and investigators, which also influenced the teachers’ attitude to allowing students to solve problems and tasks themselves, and not take over. The teachers’ students particularly pointed out that teaching in pairs created greater learning opportunities. This allowed them to get a “second” explanation to enhance their understanding, and the interaction—the comments and interactions between the teachers—contributed to a more positive, more pleasant and more entertaining teaching climate in the classroom. For the teachers, it was an epiphany to find that the students profited from a “second” explanation that they could take with them into other teaching situations.

4.2.3. The observations of the teachers in the classroom

In a qualitative Scottish study, Philpott and Oates (Citation2017) studied teachers’ professional development in PLCs using Learning RoundsFootnote3 as method. Findings in the study indicate that teachers fail to pay enough attention to observations of the effect teachers’ actions have on students learning and thinking in teaching situations. The researchers suggest that the reason for these failed observations may be that the focus and discussions of teachers were generally on technical details and the teachers’ actions in the classroom, with little attention being focused on the relation between the teacher’s actions and the response and thinking of the students relating to the actions. Philpott and Oates (Citation2017) maintain that weak observations may lead teachers to accept practices that basically are not good due to the lack of attentiveness when it comes to the way the students see things, which in turn may undermine their learning and the opportunities the teachers have to focus on the students as learners. The LS study by Widjaja et al. (Citation2015) points out that the strong student focus in all phases and processes was new and unknown for the teachers. Findings show a strong focus on students in the observations contributed to changes and improvements to the teachers. Findings particularly highlight the importance of predicting student responses and thinking in the planned learning activities which also increased the focus of the observations. Here it is explicitly pointed out that the teachers learned more about their students by changing from a teacher-oriented perspective on teaching, tasks and planning to a student-oriented perspective with a focus on problem-solving tasks to encourage the students’ thinking and understanding.

Findings in the studies by King (Citation2016) and Owen (Citation2015) show that when teachers are involved in and moved from delivering the curriculum to developing the curriculum for their students, seen in light of the students’ progression (Owen, Citation2015) and the teachers’ observations, they experience an epiphany. The teachers’ agency was also enhanced, an aspect which I will describe in the next category.

4.3. Teachers as agent

4.3.1. Professional identity

Andresen (Citation2015) points to a teacher’s identity as an important phenomenon in his or her development and learning. Findings in the study suggest that a teacher’s identity is closely linked to their learning, as identity and learning are mutually connected. When teachers in the study feel they are in a position to influence their own learning and own practice, this contributes to strengthening their professional identity. An American case study with three teachers and a student teacher who met six times over a semester to discuss and reflect on video recordings of the teaching performed by the teachers considers identity as an essential factor for teachers’ learning (Steeg, Citation2016). Findings in the study show that the professional identity and confidence of the teachers are decisive for whether tensions and contradictions are highlighted and how they are highlighted and discussed. Steeg (Citation2016) also points out that the teacher team developed a collective identity through discussions and reflections which enabled them to oppose and teach “a little” against the standardized practice existing in the school. When the professional identity and values of teachers express fear and resistance against entering uncertain territory, or the desire to avoid the uncertain, it is according to Ning et al. (Citation2016) a strong indicator of low engagement and quality in PLCs.

4.3.2. The importance of being an agent and daring to be an agent

In her study, King (Citation2016) states that teachers’ professional development undoubtedly is part of a complex system which occurs over time through a variety of processes, and never through individual incidents. Several findings in King’s study (Citation2016) underscore the importance of teachers as agents in processes related to their professional development. First, it is important to acknowledge and appreciate the important role teachers play in change processes which are necessary for improvements and changes in the school. Second, motivation is created in the teachers when their project satisfies their personal and professional needs, and when it is closely connected to practice and students’ learning. Third, importance is attached to the need to help teachers adapt new practices which satisfy individual pupil needs, where the teachers can see opportunities for how the new can be adjusted to existing practices. Fourth, the findings point to the importance of the teachers’ agency when they discover that they need to manoeuvre out of structures, organizations and patterns when it becomes apparent that the students do not understand things in the same way or when there is no meaning-making process for students, and that the teachers have the authority and ability to change their practice.

Philpott and Oates (Citation2017) underline that theory of actionFootnote4 is an important element in Learning Rounds. Several findings in the study show that many of the discussions among the teachers resulted in an implicit theory of action, and that the theories were not challenged by other alternatives or perspectives. Philpott and Oates (Citation2017) point out that an implicit theory of action will never become an object of scrutiny and therefore never present a potential for revision. It will legitimize the school’s culture and authority. The researchers add that an explicit theory of action would have made it possible to examine and revise it and add other alternatives and perspectives, which would have strengthened the teachers’ agency. When teachers lacking other alternatives and perspectives, Philpott and Oates (Citation2017) ask where the alternative discussion should come from when it appears that the teachers have very similar views on teaching and learning, even if they come from different schools. Findings from the study show that teachers may be trapped by the discourse which defines how they frame their actions. They indicate that this discourse, which is the primary resource for the teachers’ conversations and thinking, contributes to limiting the alternative discourse, and that this is a problem for teachers’ agency. The researchers propose that the task of PLCs must be to help teachers escape routines and habits so that they strive to promote alternative discourses, ask questions, have a critical eye and dare to do their own thing and think their own thoughts.

Findings in the study by Soini et al. (2016) show that teacher agency, or professional agency, is a complex entity of linked components that reflect teachers’ efforts to both influence and transform the classroom as a learning environment and reflect on and adjust their own actions. The findings also show that it is not enough to create or support teachers’ motivation for development activities, teacher agency also means that teachers must believe that they are personally competent to change the teaching in the direction they want, and that they believe they can personally contribute to improvements.

4.3.3. Professional growth and autonomous teachers

In an Australian study by Widjaja et al. (Citation2015), their point of departure is the Interconnected Model of Professional Growth,Footnote5 and based on this model they have examined the professional growth of teachers according to their engagement in LS. Findings from the study show that teachers’ development and growth occur step by step and gradually. By showing the connection between the four domains in the model and the dynamic influence of the mediating processes between the participants for development and growth, the potential of LS as a method for teachers’ learning is made clear. Feeney (Citation2016) examined 28 teachers in an American school where the aim was to examine how teachers’ orientation to learning influences teachers’ expansive learning and changes in practice. This is a mixed-method case study consisting of interviews and questionnaires. Relating to teachers’ agency and professional growth, findings in the study show that: professional learning goals must be adjusted to the teachers’ needs, that teachers are autonomous and able to make their own decisions in their learning, that they have high awareness of collaboration and how to support each other, that they decide what and how they should learn to improve practice and that they assume a leadership role and ownership over learning and improvement of practice. In addition, the importance of horizontal leadership (not top-down) and support from colleagues and trust between teachers and leaders are emphasized. Findings in the study also show other factors that can impede development and growth: negative attitudes and lack of commitment, too many activities and tools being juggled at the same time, no clear focus and lack of communication, and whether the local/county or state authorities exert pressure to improve the test result. In addition, the study shows that teacher’s orientation to their own growth has the power to influence and motivate to potentially learning and change in the workplace.

4.3.4. Reflection

Several studies highlight reflection as an essential factor for teachers’ professional development (Soini, et al., 2016; Doecke, Citation2015; Kelly and Cherowski, Citation2015; Owen, Citation2015; Philpott & Oates, Citation2017; Steeg, Citation2016). Soini et al. (2016) point out that reflection is considered to be the main strategy for teachers’ learning, but also that reflection alone does not guarantee changes or improvements in practice. Reflection should be combined with other strategies where teachers as professional agents actively monitor and influence practice and the environment to create better learning for students and teachers. In his article, Doecke (Citation2015) claims that storytelling as a method promotes awareness of who/what I am as a teacher, who my students are and what creates meaning for the teacher and the students, thus contributing to developing reflective awareness. The study also shows that this method may strengthen teachers’ agency through increased awareness of oneself as a teacher and of one’s students, where the teacher reflects on what is a good and desired practice in the existing context. Steeg (Citation2016) discusses the reflection concept, stating that good reflections must include specific content or ideas which teachers should reflect on. Moreover, reflection should include discoveries, examinations and considerations of implications relating to one’s own convictions, experiences, knowledge and values in relation to teaching. In her study, Steeg (Citation2016) promotes video analysis as a good approach for increasing agency in teachers and the opportunities it offers them to reflect on further actions. In their findings, Philpott and Oates (Citation2017) maintain that the lack of discussions and reflections beyond the actions themselves and which include questions about the purpose, values and meaning will impede the professional development of teachers. The researchers point out that the lack of thorough reflection undermines teachers’ agency and reduces teacher autonomy, emphasizing that teachers must practice to acquire competence in conducting meaningful discussions and reflections.

4.4. Analysis and discussion

In responding to the twofold research question in this review study, I will commence with the first part, which focuses on the ways in which teachers’ professional development and learning take place. Activity theory is used as the analysis unit for examining the ways teachers develop and learn in school. To develop a deeper understanding of how to undertake and which factors underpin professional development and learning, I had to apply the entire activity system, both the uppermost action triangle (subject, mediating artefacts and object) and the lowermost triangles (rules, community and division of labour). This was done to clarify the context within which the actions take place and to see how the various factors in the activity system influence what teachers learn, how they learn and develop, and that they influence each other. The selected articles which form the basis for this review article illustrate that generally teacher teams constitute the acting subject. There are different compositions of the teacher teams; they may for example be composed of teachers at the same level, teachers teaching the same subject, or teachers from different schools teaching the same subject. In this review article is teachers’ collective professional development the focus in the selected studies, but with differing perspectives and approaches. The idea of different perspectives means for example that one study focused on the practical knowledge of teachers (Witterholt et al., Citation2016), another focused on analytical competence (Andresen, Citation2015) and several studies focused on developing ideas about the learning and teaching of teachers and new ways of acting in teaching situations (Takahashi & McDougal, Citation2016; Lim et al., 2016; Widjaja et al., Citation2015; Steeg, Citation2016; Owen, Citation2015). According to Leontiev (Citation1981, p. 62), “the object of an activity is its true motive”, which in this context means that the object or the overriding goal guides the actions of the teachers. This means that in processes around teachers’ professional development, teachers’ motivation should be created through the object itself because it is their practice and needs that ideally must be the point of departure. Several of the selected studies focus on the object, but here I choose specifically to examine four of them.

In the study by Philpott and Oates (Citation2017), the point of departure for teachers’ processes is that teachers in PLCs start by identifying a problem in their practice, then developing research questions relating to their needs and what they want to change. Moreover, three studies with LS as the approach also show that the point of departure for the actions of the teachers is based on teachers identifying problems and challenges in their practice (Lim et al., 2016; Takahashi & McDougal, Citation2016; Widjaja et al., Citation2015). In these studies, the activity is realized through chains of targeted actions, where the goals focusing on the object and the actions taking place are created by the teachers (Leontiev, Citation1981). In Learning Rounds and Lesson Study, analysing and mapping the historic and present teaching approaches in relation to the challenge are an essential element. This means that the teachers have to examine the teaching culture, teaching procedures, thinking and other factors around the existing teaching. In the activity system, these elements may be linked to the factor rules. Thereafter, it is essential to discuss and consider how the teachers can envision new ways of thinking and acting (Philpott & Oates, Citation2017; Takahashi & McDougal, Citation2016). In the analytical and creative processes taking place here, the interactions occurring between the individuals in the community have consequences which have impact on the factors rules and object in the activity system. Findings in these studies show the importance of the collective processes for teachers’ professional development, and how responsibility and progress depend on the teachers themselves, hence the importance of the community in the activity system. The collective processes in PLCs also have positive effects on teachers’ learning and development and help to strengthen their agency. This is also supported by Kelly and Cherkowski (Citation2015), which suggests that PLCs contribute to strengthening the autonomy of teachers and to creating more self-confidence. This study also shows that it is easier for teachers to address disagreements and contradictions in teams working with common challenges towards a common goal. If we consider this in light of the activity system, it may suggest that the processes in the community contribute to raising the awareness of the teachers’ responsibilities and work duties in the horizontal division of labour. Hence, everyone has a responsibility for establishing and maintaining good and meaningful processes towards the object. This also shows that the factors in the activity system mutually impact each other.

Engeström (Citation2001) states that tensions and contradictions are potential sources of change and development, and that they are a necessary force for expansive learning taking palce and a motivating force in the activity system. Biesta et al. (Citation2015) also point out that teachers often act within a culture of performativity, which impedes important tensions and contradictions that Engeström (Citation2001) believes are vital sources of change. This means that they are caught in a particular discourse or a specified way of thinking and acting, i.e. rules in the activity system. Biesta et al. (Citation2015) believe that this reduces the alternative discussion, and also ask where the alternative discussion will come from when the teachers have very similar views on teaching and learning.

The studies by Takahashi and McDougal (Citation2016), Widjaja et al. (Citation2015), Gonzàlez et al. (Citation2016) and Visnovska and Cobb (Citation2015) point out the importance of using external experts or researchers as support and collaboration partners in development activities in schools. In these studies, the external experts have contributed by introducing new perspectives, creating focused and meaningful dialogues, challenging the thinking and actions of the teachers by questioning their practice, strengthening the observation focus and directing attention on what may be the next step related to the overriding goals. In these studies, the external expert’s function as mediating artefacts in the activity system. These findings show that external experts may lead the teachers in the direction of tensions and contradictions which Engeström (Citation2001) describes as the point of departure for development, and that the alternative discussion which Biesta et al. (Citation2015) call for may be triggered by external experts. Here the external experts introduce new perspectives and challenge the teachers thinking and actions. They also introduce new tensions and contradictions in the activity system which in turn will require that the teachers reconstruct their opinions and perceptions about the activity itself (teaching and learning), which is essential in the activity system (Engeström, Citation2001). Furthermore, opportunities may be created where the teachers will have to analyse and reconstruct the circumstances and conditions their actions take place in and acknowledge the routine processes and habits they have and are not always aware of. This is related to the factor rules in the activity system (Engeström, Citation2001), and to Leontiev’s (Citation1981) concept of operation.

Several studies indicate that the view or perception teachers have of students as learners and students as active or passive in the learning process does not only influence the students’ learning but also the teachers’ learning. One of the studies showed that when teachers refer to students as performing “high” or “low”, or to students who “are able to” and who “are not able to”, these are discourses which define and control the thinking and actions of the teachers, thus placing limitations on their learning and chances to see other perspectives (Wilson et al., Citation2017). They also found that there was a lack of specific norms and ways of discussing students as learners. Another study maintains that the failure to see students as active participants in the construction of learning environments and knowledge will impede the learning of both students and teachers (Soini et al., 2016). In both studies, the factor rules in the activity system influences how teachers discuss students as learners. When teachers feel they must comply with predetermined ways of carrying on a discussion, this also creates limitations on the language as a mediating artefact. The performativity mentioned by Biesta et al. (Citation2015) and the lack of specific norms and ways of discussing students, as shown in the study by Wilson et al. (Citation2017), may contribute to the rules and regulations for what teachers discuss undermining the importance of language as a mediating artefact. It reduces the opportunities for tension and contradictions and alternative perspectives to emerge for the participants in the activity system. Ning et al. (Citation2016) point out that many teachers are afraid of and hesitate to enter uncertain areas and therefore avoid discussing the unknown, what is not readily visible. They find that in such cultures, collaborative learning in professional learning communities will have poor conditions for growth and development. Witterholt et al. (Citation2016) and Philpott and Oates (Citation2017) suggest that the existing culture (rules) and the trust between the participants in the community, help determine the directions teachers follow and contribute to regulating the teachers’ discussions. This means that communities that have a lack of trust in both the horizontal division of labour with colleagues and in the vertical division of labour between teachers and leadership will have poor conditions for collaborative learning. All these findings highlight the problem Biesta et al. (Citation2015) refer to, where they point out that the lack of alternative discussions and perspectives and the lack of the necessary mutual trust will restrict the professional development of teachers. Findings like these shed light on the fact that the factors “rules”, “community” and “division of labour” in the activity system interact, and that an analysis of the interaction between them is necessary if the actions and processes toward the overriding goal are to be strengthened (Engeström, Citation1987, Citation2001, Citation1999).

Several of the studies emphasize that giving teachers opportunities to reflect is a positive factor in the work with teachers’ professional development (Soini, et al., 2016; Doecke, Citation2015; Kelly & Cherkowski, Citation2015; Owen, Citation2015; Philpott & Oates, Citation2017; Steeg, Citation2016). They find that professional development occurs in collective communities and reflections occur through interactions in the community. This means that reflections are linguistic actions that are considered mediating artefacts in the activity system. Some of these studies also underline (Philpott & Oates, Citation2017; Steeg, Citation2016; and Soini, et al., 2016) that reflection should include different elements if they are to have a positive effect on the professional development of teachers. According to Engeström and Sannino (Citation2010), reflection is about making the implicit explicit, and being able to give the uncertain and not yet spoken a language. Postholm (Citation2012) states that being able to reflect implies training in a meta-view of one’s own practice and the practice of others. If the participants in a community do not have mutual trust and are not open with their colleagues, which is required to have deeper reflections where vulnerability, wondering, examinations and new thoughts and perspectives can appear (Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012), this will reduce the importance of reflection as a mediating artefact. It will also inhibit the opportunities the teachers have to question the existing culture, their ways of thinking and acting and the leading discourse about learning prevalent in the school, which in the activity system are described as rules.

According to Hall and Hord (Citation2006), it is wrong to assume that professional development occurs automatically if it is facilitated for collaboration between teachers. Professional development must be controlled, led and supported, for example, by bridging between the old methods and implementation of the new which will help teachers to gradually engage in new practices and ways of thinking without discarding old ways that function in the existing practice. This is also supported by Robinson (Citation2018), who believes that a focus on improvements in existing practice instead of focus on major changes is a good approach to development and learning. When external experts bring new perspectives and thoughts into the activity system, this may contribute to expanding the teachers’ zone of proximal development as Engeström (Citation1987) has defined it. The “new” will challenge the existing ways of thinking and acting and challenge the teachers to think in new ways about teaching and learning in collective processes, which in turn may generate new understanding and insight into the activity itself. It is also important that the external experts interact with the teachers on their skill level and according to their current knowledge (King, Citation2016), and introduce perspectives and ideas that create meaning to expand the teachers’ zone of proximal development. The study by González et al. (Citation2016) shows how the researchers collected data from the teachers’ practice through observations of teaching and conversations with the teachers. The data reflected the teachers’ practices and their level of skill and knowledge, and thus formed the foundation on which to develop the new perspectives and ideas the external supporting persons presented and showed where there were needs for support and where they could challenge the teachers. This data material, which Cole and Engeström (Citation2007) designate “mirror data”, was returned to the teachers and functioned as a “collective mirror” for the participants (Engeström, Citation2000). The mirror data were the point of departure for encouraging the teachers to reveal their arguments and disagreements and for showing how the researchers and the teachers together could develop research questions focusing on the object. In research within CHAT, researchers are regarded as mediating artefacts in the activity system, and an important task for the researcher is to discover and make tensions and contradictions in the activity system visible to the participants. (Engeström, Citation2001; Engeström & Sannino, Citation2010; Virkkunen & Newnham, Citation2013). This means that the researcher is both involved in the development work together with the teachers and part of the result of the teachers’ professional development. It also means that CHAT researchers do not have a neutral position. The study by Gonzales et al. (Citation2016) shows the importance of the researchers refraining from adopting a neutral position, and that in an active position they could present their arguments, their understanding, their opinions on the actions that took place and their interpretations of collected data. In this way, they acted as mediating artefacts, and they could add new content to the teachers’ activity, teaching.

5. Concluding remarks

This review article has described several supportive factors for the outcome related to teachers’ collective professional development in school. Findings in the review suggest that collective processes in professional learning communities in an environment that places trust between teachers and between teachers and leadership high on the agenda are essential factors for the outcome. Teachers’ participation in planning and design of the approach to professional development is also emphasized as important. Moreover, many findings in the study underline the importance of external support and an approach that supports teachers’ agency in the work of professional development and changes in practice. This indicates that it is not enough for researchers to only undertake research on development and learning processes in school. They must also conduct formative intervention studies, which means that the researchers provoke and maintain an expansive transformation process led and owned by the teachers (Engeström & Sannino, Citation2010), and conduct research on these processes. Another important finding which has significant impact on the teachers’ outcome, and which greatly formed the basis for changes in practice, was when the approach to development and learning focused on students as learners, and how teachers can change their discursive patterns of students as learners from being passive participants to active participants in their own learning processes. More research is needed on how teachers can contribute in planning and design of interventions related to teachers’ collective professional development. In addition, more research is needed to show how external resources, as researchers, in collaboration with teachers can contribute to teachers’ professional development.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kåre Hauge

Kåre Hauge (Department of Teacher Education, Norwegian University of Science and Technology) is an assistant professor in pedagogy. Hauge has in his studies used qualitative approaches where he is concerned both with studying ongoing processes and also supporting and leading development processes together with practitioners in intervention research related to teachers’ professional development, known as development work research (DWR). Hauge uses cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) and pragmatic theory as a framework in his studies. In addition to research projects in collaboration with schools and teachers, he teaches at the university’s teacher education in pedagogy.

Notes

1. A knowledgeable other—an external expert (may also be a researcher or university staff member) who supports and challenges the teachers in their work with Lesson Study, commenting, asking questions and contributing to creating meaningful discussions and reflections (Takahashi, Citation2013).

2. The function of storytelling is to re-conceptualize the classroom in the form of narratives and to envision opportunities beyond the here and now (Doecke & Parr, Citation2009).

3. Learning Rounds means that teachers come together to observe teaching and learning in several classrooms. They start by identifying a problem in practice, observing the problem, debriefing and then focusing on the next step (City, Elmore, Fiarman, & Teitel, Citation2009).

4. Theory of action is a rationale for how the teacher considers the link between what is done and what constitutes a good result in the classroom (City et al., Citation2009).

5. The basic principle in the model is that it features four domains. 1) External domain—external sources of information, mediating artefacts, external experts, collaboration with other schools, 2) personal domain—teacher’s knowledge, convictions, attitudes, values, 3) domain of practice—where the professional experimentation takes place, and 4) domain of consequence—where the teachers recognize emergent results for the students from the experimentation (Clarke & Hollingsworth, Citation2002).

References

- Andresen, B. B. (2015). Development of analytical competencies and professional identities through school-based learning in Denmark. International Review of Education, Journal of Lifelong Learning, 61, 761–20. doi:10.1007/s11159-015-9525-6

- Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over Ten Years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

- Biesta, G. J. J., Priestly, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 624–640. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

- Bridwell-Mitchell, E. N. (2015). Theorizing teacher agency and reform: How institutionalized instructional practices change and persist. Sociology of Education, 88(2), 140–159. doi:10.1177/0038040715575559

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

- City, E. A., Elmore, R. F., Fiarman, S. E., & Teitel, L. (2009). Instructional rounds in education; a network approach to improving teaching and learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Education Press.

- Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional Growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(8), 947–967. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00053-7

- Cole, M. (1996). Cultural psychology: A once and future diciplin. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Cole, M., & Engeström, Y. (2007). Cultural-historical approaches to designing for development. In J. Valsiner & A. Rosa (Eds.), The cambridge handbook of sociocultural psychology (pp. 484–507). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Richardson, N. (2009). Teacher learning: What matters? Educational Leadership, 66(5), 46–53.

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers professional development: Toward better conceptualization and measure. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. doi:10.3102/0013189X08331140

- Doecke, B. (2015). Storytelling and Professional Learning. Changing English, 22(2), 142–156. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2015.1026184

- Doecke, B., & Parr, G. (2009). Crude Thinking’ or reclaiming our story-telling rights: Harold Rosen’s essays on narrative. Changing English, 16(1), 63–76. doi:10.1080/13586840802653034

- DuFour, R., & Fullan, M. (2012). Cultures built to last: Systemic PLCs at work. Bloomington, In: Solution Tree Press.

- Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by Expanding. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit Oy.