Abstract

This cross-sectional study employed a mixed method design to examine perspectives of EFL student teachers at Iranian teacher universities on their future teaching abilities in terms of California Standards for the Teaching Profession (CSTP) that are stated in Commission on Teacher Credentialing. In the current study, 223 (109 female and 114 male) EFL student teachers from six Iranian teacher universities participated in a survey. Twelve interviews were conducted with 12 selected volunteers from surveyed student teachers. The results showed a difference between the perspectives of the female first-year and the male and female last-year groups. The difference was also significant between male and female first-year student teachers. Implications for teacher education are discussed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Iranian teacher training universities (Daneshgah-e-Farhangian) have recently become the only pathway to teaching in public schools in the nation. They are administered under the supervision of Iranian Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology. There are several teacher universities around the nation each have male and female branches. Graduates from these state universities are employed by the Iranian Ministry of Education as public school teachers that they have to work there for 8 years (twice the years of their university education). Moreover, student teachers have to pass eight practical courses on English teaching.

1. Introduction

The quality of education is, by and large, influenced by the quality of teachers’ work (Cochran-Smith & Fries, Citation2005; Goodwyn, Citation1997; Hagger & McIntyre, Citation2006). The vital role of qualified teachers in educational system sheds light on the importance of the characteristics of preservice teacher education programmes (TEPs) (Cochran-Smith & Fries, Citation2005). The purpose of TEPs is to help learners ‘to develop their knowledge, awareness, beliefs, and skills’ and to guide them to integrate these elements together and to put them in practice in real teaching. (Richards, Ho, & Giblin, Citation1996, 242).

Despite the important role of student teachers’ perspectives on their future teaching abilities in determining their real abilities and the fact that Iranian teacher universities programmes have an instrumental contribution in promoting such abilities far too little attention has been paid to the role of these programmes in giving student teachers a new perspective on their teaching abilities. Accordingly, in the current cross-sectional study, we examine these programmes by taking into consideration the student teachers’ perspectives at the beginning and at the end of the programmes. California Standards for the Teaching Profession (CSTP) that are stated in Commission on Teacher Credentialing (Citation2009) are used for this evaluation. CSTP include knowledge of designing curriculum and instruction, supporting diverse learners, using assessment to guide learning, creating a productive classroom environment, and developing professionally that conform to the objectives of Iranian TEPs identified by the Committee on the Unification of Teacher Training Planning (Citation2016). Additionally, Iranian teacher universities curricula for EFL student teachers highlighted them as well.

2. Teaching knowledge and abilities

Shulman (Citation1987) indicated that prerequisites of effective teaching are: (1) “content knowledge”; (2) “general pedagogical knowledge”; (3) “curriculum knowledge”; (4) “pedagogical content knowledge”; (5) “knowledge of learners and their characteristics”; (6) “knowledge of educational contexts”; and (7) “knowledge of educational ends” (8). He insisted that pedagogical content knowledge is a vital part of teaching ability. Teachers who lack pedagogical knowledge are not able to convey the subject knowledge to others easily (Darling-Hammond, Citation2008; Evertson, Hawley, & Zlotnick, Citation1985).

Voss, Kunter, and Baumert (Citation2011) introduced “general pedagogical knowledge” including “knowledge of classroom management, knowledge of teaching methods, knowledge of classroom assessment, knowledge of learning processes, and knowledge of individual student characteristics” (953). While most studies on teacher education made a distinction between different aspects of teaching knowledge, Kumaravadivelu (Citation2012) underlined the importance of such a TE system that enable student teachers to formulate learning and teaching theories based on their own teaching practice and then put their own theories into practice in the classroom.

3. Teacher education

There is a positive relationship between teachers’ participation in preservice TEPs and their teaching abilities (Evertson et al., Citation1985; Goodwin & Oyler, Citation2008). Darling-Hammond (Citation2008) believes “teachers learn just as students do: by studying, doing, and reflecting; by collaborating with other teachers; by looking closely at students and their work; and by sharing what they see”. Concerning professional development, Gao (Citation2015) stressed the vital role of a Chinese TEPs which enabled English student teachers to teach in a variety of local and global contexts.

Despite the importance of TEPs in developing student teachers’ teaching abilities, Gutierrez Almarza (Citation1996) indicated that student teachers’ knowledge traced back to influences of several sources of knowledge besides TE courses, including the student teachers’ background knowledge; the combination of their previously acquired knowledge and what they learned during their TE; and finally the student teachers’ uses of these different types of knowledge in real context of teaching. Similarly, Borg (Citation2004) drew attention to the fact that many of the beginning teachers adhere to the knowledge which they acquired during their school education by observing their teachers.

Nevertheless, there are always factors that make TEPs less successful than they should be. Murray (Citation2008) took a number of TEPs’ shortcomings into consideration. They stemmed from inadequate preparation in terms of subject knowledge as well as pedagogical knowledge; the fact that the time that is devoted to bring about changes in student teachers’ knowledge is not enough; and neglecting the students’ needs in TE curriculum development. In addition, Yan and He (Citation2010) recognised some shortcomings in a Chinese EFL student teachers’ practical course. Firstly, student teachers hardly find the opportunity to apply their knowledge of teaching in a classroom. Secondly, there was the time devoted to enable student teacher for real teaching was limited. Thirdly, there was a loss of confidence in teaching abilities among school teachers. Insufficiency of supervisors, ineffective assessment, and some students’ unwillingness to work seriously were other shortcomings of this teacher training course.

To evaluate the impact of teacher education institutions, Darling-Hammond (Citation2006) stressed the use of several evaluative measures to gain a proper understanding of the issue. Darling-Hammond, Newton, and Wei (Citation2010) pointed out that in order to have an effective TEPs there should be benchmarks for evaluation of the programmes and they believed that California Standards for the Teaching Profession can be used as such benchmarks.

4. Perspectives on teaching abilities based on California standards for the teaching profession

Student teacher’ perspectives on teaching and what they are supposed to do is not clear. However, these perspectives will influence their actions in the future (Hong Citation2010). In order to develop their professional identity, student teachers should try to examine the actual teaching practice to find the qualities they think important for a teacher to possess. Based on the California Standards for the Teaching Profession (CSTP), good quality of preservice teachers’ preparation plays an important role in teachers’ professional growth and achievement. CSTP include six teaching standards as a range of knowledge and abilities in teaching. The standards are:

“Engaging and Supporting All Students in Learning”;

“Creating and Maintaining Effective Environments for Student Learning”;

“Understanding and Organizing Subject Matter for Student Learning”;

“Planning Instruction and Designing Learning Experiences for All Students”;

“Assessing Student Learning”; and

“Developing as a Professional Educator” (Commission on Teacher Credentialing, p. 3).

Darling-Hammond’s (Citation2006) questionnaire was validated to collect information about the Stanford Teacher Education Program in terms of several aspects of teaching knowledge and competencies. These are in agreement with CSTP. This questionnaire was used in this study to examine Iranian EFL student teachers’ perspectives on their future abilities to teach based on CSTP. The reason for using this questionnaire is that CSTP corresponds closely to the goals of Iranian Teacher education programmes that are stated by the Committee on the Unification of Teacher Training Planning (Citation2016) and reflected in Iranian teacher universities curricula for EFL student teachers as well.

5. Training programmes for iranian EFL student teachers

The information about Iranian teacher education context that is provided in this introductory paragraph has been extracted and translated from “Iranian Teacher Education University Statute” (Asasnameh-e- Daneshgah-e- Farhangian) that was approved by the “Supreme Council of Educational Revolution” in 2012. Iranian teacher universities have recently become the only pathway to teaching in public schools in the nation. They are administered under the supervision of Iranian Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology. There are several teacher universities around the nation each have male and female branches. Graduates from these state universities are employed by Iranian Ministry of Education as public school teachers that they have to work there for 8 years (twice the years of their university education). Moreover, student teachers have to pass eight practical courses on English teaching.

Aliakbari and Tabatabaei (Citation2019)translated the purposes of the Committee on the Unification of Teacher Training Planning (Citation2016) that focus on professional teaching. They state it is expected that B.A. graduate students of TEFL to be able to

identify educational problems in the teaching process and attempt to use appropriate strategies to solve them;

know the principles of Islamic education in order to strengthen good behaviour among students based on these principles;

provide students in the classroom with learning opportunities which suit individual differences, such as differences in ethnicity, culture, and religion;

use the principles of reflective teaching to evaluate their professional practice continuously;

understand the process of cognitive development, enhance problem-solving ability among students, and provide students with learning opportunities that develop their critical and creative thinking;

attempt to create or enrich educational/pedagogical opportunities and develop professionally through using information and communication technology, internet and instructional websites (Committee on the Unification of Teacher Training Planning, pp. 6–7).

To the best of researchers’ knowledge, no study has been found examining Iranian EFL student teachers’ perspectives on their future abilities to teach, based on necessary standards for the teaching profession. Thus, the purpose of the present study is to examine EFL student teachers’ views on their abilities to teach in a real classroom. In this regard, we conducted an evaluation of the effect of TE programmes on developing student teachers’ teaching abilities, congruent with the standards for the teaching profession, by comparing the perspectives of the first-year EFL student teachers with the last-year ones.

The study seeks to answer the following questions:

What are the first-year EFL student teachers’ perspectives on their future abilities as English teachers?

What are the last-year EFL student teachers’ perspectives on their future abilities as English teachers?

Is there any difference between these two groups concerning their perspectives on their future teaching abilities?

Is there any difference between males and females concerning their perspectives on their future teaching abilities?

6. Method

A mixed-method design was employed to supplement the data collected through a survey questionnaire with in-depth interview data.

6.1. Participants

Two hundred and twenty-three student teachers participated in this study (excluding those participants with incomplete data on the measure) among them 109 participants were female and 114were male student teachers from six Iranian teacher universities (three men’s and three women’s branches). More details about participants’ distribution are presented in Table . We employed a cluster random sampling technique due to geographical distribution of the universities to cover a wide range of geographical areas in our survey.

Table 1. Participants’ distribution in the sample

Participants signed an informed consent form accompanied the questionnaire. Twelve student teachers were selected from volunteers who accepted our invitation to participate in interviews. To ensure confidentiality, pseudonyms have been used for interviewees.

6.2. Data collection and analysis

6.2.1. Quantitative data: survey questionnaire

Darling-Hammond’s (Citation2006) questionnaire was adopted with permission to explore participants’ perspectives on their future abilities in terms of a range of teaching abilities includes five areas of teaching knowledge (as five factors) which are in relation to CSTP, these areas, as stated by Darling-Hammond (Citation2006), are:

Design curriculum and instruction (CSTP, Standards 3, 4)

Support diverse learners (CSTP, Standard 1)

Use assessment to guide learning and teaching (CSTP, Standard 5)

Create a productive classroom environment (CSTP, Standard 2)

Develop professionally (CSTP, Standard 6)

Table 2. Correspondence between Iranian teacher universities objectives, factors of questionnaire, and CSTP

The questionnaire was piloted on 30 (16 first-year, and 14 last-year student teachers) to ensure the appropriateness of items. A teacher trainer who was a TEFL expert and another one who was an expert in educational psychology verified that the content of the questionnaire is in line with what is stipulated by the Committee on the Unification of Teacher Training Planning (Citation2016) as the objectives for Iranian teacher training programmes for EFL student teachers. In addition, Darling-Hammond (Citation2006) confirmed that the factors of her questionnaire match up with CSTP; therefore, the content validity of the questionnaire was established. The 28-item questionnaire administered to 223 participants.

Confirmatory factor analysis with Maximum likelihood extraction and oblimin rotation verified the presence of the underlying five-factor model of the questionnaire. As shown in Table , the Cronbach’s alphas, as a measure of reliability, for all factors were high (α˃.83). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the questionnaire was .97, indicating a high estimate of reliability for the questionnaire with our sample. Descriptive statistics about the variables are reported in Table .

Table 3. Reliability estimates for the five factors of the questionnaire

Table 4. First-year and last-year student teachers’ scores on the perspectives on their future abilities in five areas of English teaching

A 2*2*5 Mixed Between-within (Repeated Measures) ANOVA was used to see whether the four (two male and two female) groups differed in terms of their perspectives on their abilities and also to identify any interaction of gender and group. For quantitative data analysis, the SPSS 21.0 was used.

6.2.2. Qualitative data: semi-structured interviews

Twelve (six first-year and six last-year) out of 223 surveyed student teachers participated in face to face semi-structured interviews. They were selected from the volunteers on the basis of their representativeness to our sample. The interview questions were five factors of the questionnaire and the participants provided detailed responses to the questions (see the Appendix). Confusing concepts such as professional development, productive classroom, etc. were clarified based on what is stipulated in Commission on Teacher Credentialing (Citation2009). The purpose of interviews was to gain a deeper understanding of student teachers’ perspectives and validation of the results of the survey.

Finally, the content analysis technique was used in order to find repeated patterns or themes in our data. Cohen, Manion, and Morrison (Citation2007) guideline was followed for content analysis. The steps of the study based on this guideline are as follows: first, the research questions were posed; then, transcription of 12 interviews were selected as the corpus; next, the sample texts based on research questions were selected for analysis; the text was generated during the 25 to 40-min interviews in Persian while the answers were audio-recorded (by permission) and translated into English after transcription; sentence was selected as the unit of analysis; afterwards, sentences were analysed to extract codes (e.g., supervisors’ support); then, the texts were coded and recoded several times by the authors and those codes with common features were grouped into same categories (e.g., insufficient guidance from supervisors); subsequently, the data were analysed based on the identified codes and categories; then, main codes and/or categories were summarised; finally, inferences were made from analyses. In this study inter-coder reliability was .89 that shows a high rate of agreement between the authors as two coders. Quantitative findings as well as the results of content analysis of interviews’ transcriptions are presented and discussed below.

7. Results

7.1. Quantitative findings

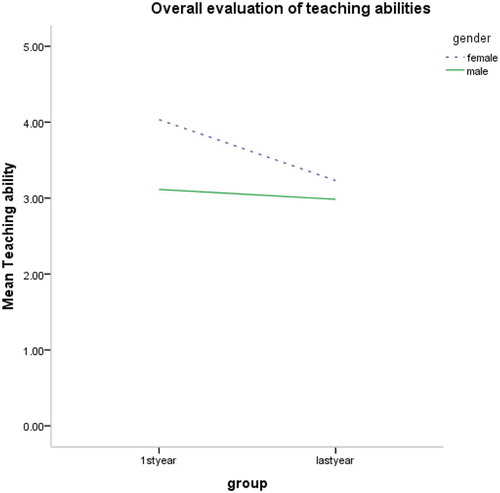

Descriptive statistics provides an overview of student teachers’ perspectives on their abilities and the impact of TE programmes in this regard (see Table ). Overall evaluations’ mean scores of the groups revealed that female first-year student teachers had the highest score, it means that they had higher expectations than their male counterparts. Female last-year student teachers, male first-year student teachers, and male last-year student teachers ranked second, third, and fourth, respectively.

A 2*2*5 Repeated Measures ANOVA performed to see whether there were differences between two groups on their perspectives on their abilities in a range of teaching abilities. We also examined the difference between males and females regarding this issue as well.

The multivariate test compared the mean differences between two groups as well as males and females on the five factors of the instrument. It suggested that there was not a significant interaction effect between perspectives on teaching ability, group, and gender (p ˃ 0.1). However, significant differences at a multivariate level were found for student teachers’ evaluations on their teaching abilities on five areas of teaching knowledge [Wilks’ lambda = .96, F (4, 216) = 2.65, p = .03, η2 = .05]; however, the effect size was small.

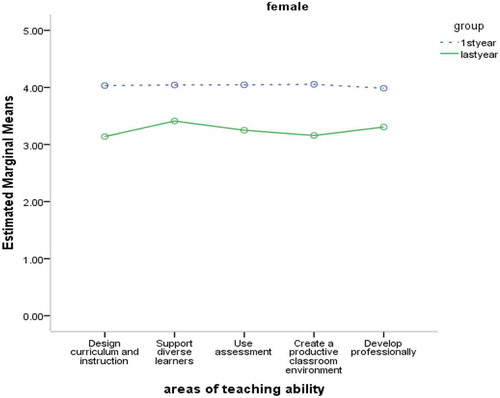

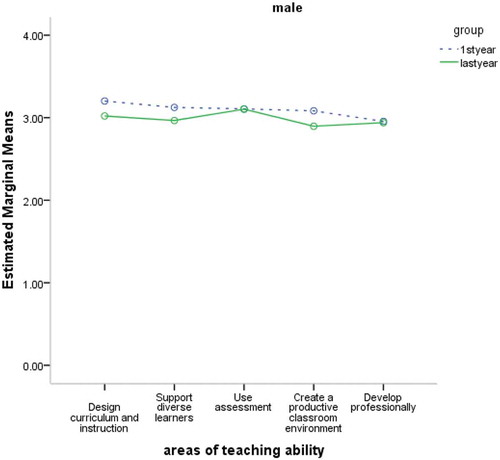

Follow-up univariate analyses revealed that there were statistically significant main effects for group [F (1,219) = 15.28, p < .0005, η2 = .07] and gender [F (1,219) = 28.09, p < .0005, η2 = .11] with a medium and large effect sizes, respectively (See Figure ). There was also a statistically significant interaction effect between group and gender [F (1,219) = 8.7, p = .004, η2 = .04] with medium effect size.

Separate gender analyses showed that the mean score for the female first-year group (M = 4.03, SD = .94) was statistically different from the mean score for the female last-year group (M = 3.23, SD = .89). For males, there was not statistically significant difference between first-year and last-year groups (See Figures and ).

7.2. Qualitative findings: student teachers’ perspectives on their future language teaching abilities

Five questions conform to five factors of Darling-Hammond’s (Citation2006) questionnaire were answered by interviewee student teachers:

How well do you think teacher universities programmes (will/have) develop(ed) your ability to:

design curriculum and instruction?

support diverse learners?

use assessment to guide learning and teaching?

create a productive classroom environment?

develop professionally?

The responses were coded and categorised based on genders and groups besides questions; however, gender and group-based categorization revealed more information.

7.2.1. Female first-year student teachers

Anita (in question 1) projected a positive image of her school teachers as a model and wished to take advantage of the programme to develop her teaching abilities. She has also an optimistic perspective on her future abilities as an English teacher, her knowledge, and her personality traits. Elena had high expectations of the programmes and practical courses. In question five she apparently, does not understand what professional development is.

7.2.2. Male first-year student teachers

Parsa (in question 1) and Ali (in question 4) did not have positive images of the programmes because they believed that successful teaching depends on their own efforts and competencies and teacher training could not have a dramatic effect in this regard.

Ali (in question 1) and Parsa (in questions 2, 3, and 4) stated real experience of teaching is more effective than theoretical courses. Ali’s response to question five reveals that he had no vivid imagination of what professional development is about. He also had doubts about of the significance of training programmes on supporting diverse learners and creating productive classrooms. Parsa had not optimistic perspectives on the future outcomes of the programmes. As shown by the data, the first-year student teachers’ responses had two sources: their views of teaching practice and their opinions about the programmes.

In summary female student teachers linked successful teaching to their positive personality traits as well as to the training programme. Notwithstanding, some of them wished to become like their school teachers and some others had no vivid imagination of the teaching profession. They had optimistic perspectives on their future abilities as an outcome of the programme. They also had positive images of practical courses.

Their male counterparts were pessimism about the significant influence of the programmes on their future teaching abilities, because they believed teaching experience is more important than academic training and that successful teaching is a result of personal efforts rather than learning theories at university. Some male student teachers had no clear idea about what teaching abilities are.

7.2.3. Female last-year student teachers

Lida constantly expressed her worries about her teaching abilities. These worries were linked to the fact that she was not satisfied with her experience of practical courses (in question 1), she felt doubt about what would happen in the real teaching context (in questions 3) and she was not confident about her future abilities (in question 1). She had a complaint about practical courses in which she had limited responsibilities and received little immediate and/or constructive feedback from school teachers and supervisors (in question 2). In responses to questions two to five, she stated that her teaching knowledge and abilities in some areas of teaching were developed; however, she was not sure whether these abilities would help her in real teaching context. She said the programmes had not lived up to her expectations (in question 5).

Dina was more self-confident than Lida in terms of theoretical knowledge she had learned from different courses; however, similar to Lida, she was not sure whether she had the ability to apply her knowledge effectively in the real context of teaching (in questions 1, 2, and 3). She indicated that more time and practical courses were needed in order to make the programme highly effective (in question 5).

7.2.4. Male last-year student teachers

Vahid (in questions 1, 2, 3, and 5) acknowledged that he gained broad theoretical knowledge in all above-mentioned areas of teaching knowledge; however, he complained about teacher trainers’ lack of considerable expertise (in question 5) as well as practical courses in terms of time, supervisors’ guidance and school teachers’ support (in questions 1, 2, and 3). He also criticised the programmes for failing to encourage student teachers to be creative (in question 4). Future ability to put theories into practice was his main worry (in questions 2 and 3).

Similarly, Kaveh expressed dissatisfaction with the programme. He indicated that taking a large number of general courses was unnecessary (in questions 1 and 4), teacher trainers were not competent (in questions 1 and 3), and practical courses did not meet some standards (in question 4). In response to question five he said, unfortunately, his expectations of the programmes were not fulfilled. Similar to Vahid, Kaveh was doubtful whether he would be good at utilising his teaching knowledge and ability (in questions 2 and 3). The data suggested that males ascribed their lack of outstanding teaching ability to the quality of the programmes, and females were anxious about not being well-prepared to demonstrate their teaching abilities in the real classroom.

In summary, both male and female last-year student teachers acknowledged they acquire appropriate theoretical knowledge of teaching; however, uncertainty about teaching abilities, was one main females’ worry. They expressed their dissatisfaction with the programmes in terms of incompetent teacher trainers, their limited responsibilities in practical courses and limited feedback from school teachers and supervisors.

Their male counterparts criticised the programmes for incompetent teacher trainers, ineffective practical courses in terms of time and supervisors, and unnecessary general courses that they had to take. They also expressed their worries about their future abilities in putting their knowledge into practice. Both males and females believed the programmes failed to fulfil their expectations.

8. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine Iranian EFL student teachers’ perspectives on their future teaching abilities in terms of five areas of teaching knowledge including designing curriculum and instruction, supporting diverse learners, using assessment to guide learning, creating a productive classroom environment, and developing professionally. Comparing the first-and last-year EFL student teachers’ views on their future teaching abilities provided insights into the effectiveness of TE programmes for EFL student teachers as well.

The results showed that female first-year student teachers had more positive perspectives on their future abilities than males. As results revealed both males and females indicated that their personal traits would have a vital impact on their learning outcomes; however, females had more optimistic perspectives on their abilities in the future, mostly as a result of teacher training. In a similar vein, Kalaian and Freeman (Citation1994) showed that female student teachers were more optimistic than men regarding the outcomes of their training programmes at the beginning of these programmes. Seemingly, females had a simple image of teaching in their background that overlooked the complicated situation of real teaching (Hong Citation2010). Similarly, Gutierrez Almarza (Citation1996) pointed out that student teachers have a background knowledge that has been formed based on their experience of being taught as pupils or it has been acquired from their teachers or other pupils. This knowledge gives them an over-simplified picture of what teaching is like (Borg, Citation2004).

One factor that very probably affected the results is the distinctive characteristic of those who enter the TE university through Iranian National University Entrance Examination. As students received a salary as they enter these universities and their employment by Iranian Ministry of Education is guaranteed, these universities are among the most competitive universities in Iran, especially for female applicants and only top students in Entrance Exam have the opportunity to enter these universities. Most of these students set high standards for themselves in many aspects of their life including their education and their future abilities. These idealistic views might affect the results of the study.

It was also revealed that females last-year student teachers had slightly more positive perspectives than did males. The results showed that males believed that the reason for their lack of full abilities is the TE programmes; however, females admitted that they suffered from a lack of confidence in their abilities. This result is in line with, Kalaian and Freeman (Citation1994) who indicated that male student teachers were more self-assured than females regarding their teaching abilities, however, females acquired more than males from TE programmes. In the interview section of our study, females first-year student teachers expressed that they would be teachers with high teaching abilities and their confidence was more than their male counterparts, but this confidence is weaker for last-year females. The reason might be the over-simplified picture of teaching that they had in their mind which conflicted with a real-world situation that they encountered later during TE practical courses. Further reason that was also given by the student teachers is that insufficient feedback provided by their supervisors and school teachers undermined their confidence.

The finding is in line with Yayli (Citation2012) who noted that student teachers became less self-confident after the experience of practical courses. As Tang (Citation2003) pointed out, if student teachers experience demanding job of teaching but do not receive adequate support from their supervisors and school teachers, their confidence in their abilities will weaken and according to Hagger and McIntyre (Citation2006) this situation will result in student teachers’ dissatisfaction.

Both male and female student teachers recognised that they had acquired theoretical knowledge base for teaching; however, it was not clear to them how they could put this knowledge in to practice in the real context of teaching. This is the reason why they indicated in interviews that practical courses were more beneficial than other general or theoretical courses. This result is in the line of Shulman’s (Citation1998) finding that student teachers acknowledge the usefulness of practical knowledge they acquired but they do not admit that theoretical knowledge may have equal value as a practical one. Additionally, this finding is supported by Kömür (Citation2010) as well as Tang, Wong, and Cheng (Citation2016). Darling-Hammond (Citation2006) drew attention to this fact that the theoretical as well as practical knowledge that student teachers acquired during their teacher training become valuable as they enter the actual practice of teaching, because teachers teach better when they follow an “accepted practice (or routines) for a while to feel secure and to be able to move to the next stages of development and professional growth” (Akbari, Citation2007, 200). This fact is supported by Aliakbari and Tabatabaei (Citation2019) as well.

9. Conclusions

This research project was conducted to compare first-year and the last-year EFL student teachers’ perspectives on their future teaching abilities as a requisite qualification for the teaching profession. The results may shed light on the effectiveness of Iranian TE programmes in developing teaching abilities in EFL student teachers. The results revealed that the effect of programmes was below the first-year EFL student teachers’ expectation. However, there are explanations for these results that ascribed the student teachers’ dissatisfaction to other factors besides the TE programmes’ impact.

9.1. Limitations and recommendations for further research

There are, however, limitations to the current study. First, a longitudinal study might give a more accurate picture of the programme. Second, our findings depend on the attitude survey and interviews data, there are some complicated aspects of teaching that may not be captured on by these measures and other measures like observations of teachers’ actual teaching may reveal much information. Third, we only examine the student teachers’ perspectives in terms of five areas of teaching knowledge and abilities, further research into other areas of teaching abilities is recommended.

9.2. Educational implications

Despite these limitations the present research, its implications for TE cannot be ignored. Fortunately, in recent years, Iranian teacher universities raise their standards for both acceptance as well as certifications. This has the potential benefit of enhancement of the quality of TE (Shulman, Citation1987) and consequently enhancement of the quality of teaching and learning. A further implication of the study is that student teachers should be exposed to the realistic challenges of teaching to understand the complexity of teaching practice and modify the simplified picture of teaching in their mind (Kömür, Citation2010; Lindqvist, Weurlander, Wernerson, & Thornberg, Citation2017; Namaghi, Citation2009).

In addition, EFL Teacher educators must, on the one hand, insist upon theoretical aspects of teaching (Shulman, Citation1998); on the other hand, link the theories to the practice of teaching (Bråten & Ferguson, Citation2015; Darling-Hammond, Citation2006; Darling-Hammond et al., Citation2010; Kömür, Citation2010). Furthermore, school teachers and supervisors should provide student teachers with constructive and explicit feedback in order to support them and enhance their confidence in their abilities (Hagger & McIntyre, Citation2006; Tang, Citation2003).

Conflict of interest

The authors acknowledge no conflict of interest in the submission.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend special thanks to Emeritus Professor Darling-Hammond for her kind permission to use her questionnaire for this study. The authors also would like to thank the enthusiastic participants in this study who gave their time and energy for the survey and interviews.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammad Aliakbari

Mohammad Aliakbari is a full professor of Applied Linguistics. He is currently the head of Ilam University. He is interested in second language acquisition theories, teacher education and development and sociolinguistics. He has published extensively in many national and international journals.

Fatemeh Sadat Tabatabaei

Fatemeh Sadat Tabatabaei is a PhD student of TEFL. she is interested in second language acquisition theories, teacher education, identity development and materials development

References

- Akbari, R. (2007). Reflection on reflection: A critical appraisal of reflective practices in L2 teacher education. System, 35, 192–18. doi:10.1016/j.system.2006.12.008

- Aliakbari, M, & Tabatabaei, F. S. (2019). Evaluation of iranian teacher education programmes for efl student-teachers. Journal Of Modern Research in English Language Studies, 6(1), 129-103.

- Borg, M. (2004). The apprenticeship of observation. ELT Journal, 58(3), 274–276. doi:10.1093/elt/58.3.274

- Bråten, I., & Ferguson, L. E. (2015). Beliefs about sources of knowledge predict motivation for learning in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 50, 13–23. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2015.04.003

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Fries, K. (2005). The AERA panel on research and teacher education: Context and goals. In M. Cochran-Smith & K. Zeichner (Eds.), Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education (pp. 37–68). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in Education. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2009, August 27). California Standards for the Teaching Profession (CSTP). Retrieved from http://www.ctc.ca.gov/educator-prep/standards/CSTP-2009.pdf

- Committee on the Unification of Teacher Training Planning. (2016). Barnameh-e- darsi dowreh karshenasi-e-peyvasteh amouzesh-e-zaban-e-englisi: Khase daneshgah-e-farhangian [Curriculum for B.A in TEFL: Specific to Teacher University]. Tehran: Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Assessing teacher education: The usefulness of multiple measures for assessing programme outcomes. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(2), 120–138. doi:10.1177/0022487105283796

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). The case for university-based teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions and changing contexts (pp. 333–346). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Newton, X., & Wei, R. C. (2010). Evaluating teacher education outcomes: A study of the stanford teacher education programmeme. Journal of Education for Teaching, 36(4), 369–388. doi:10.1080/02607476.2010.513844

- Evertson, C., Hawley, W., & Zlotnick, M. (1985). Making a difference in educational quality through teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 36(3), 2–12. doi:10.1177/002248718503600302

- Gao, X. (2015). Promoting experiential learning in pre-service teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 41(4), 435–438. doi:10.1080/02607476.2015.1080424

- Goodwin, A. L., & Oyler, C. (2008). Teacher educators as gatekeepers: Deciding who is ready to teach. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions and changing contexts (pp. 468–489). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Goodwyn, A. (1997). Developing English teachers: The role of mentorship in a reflective profession. Buckingham Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Gutierrez Almarza, G. (1996). Student foreign language teacher’s knowledge growth. In D. Freeman & J. C. Richards (Eds.), Teacher learning in language teaching (pp. 50–78). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hagger, H., & McIntyre, D. (2006). Learning teaching from teachers: Realizing the potential of school-based teacher education. New York, NY: Open University Press.

- Hong, J. Y. (2010). Pre-service and beginning teachers’ professional identity and its relation to dropping out of the profession. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1530–1543.

- Kalaian, H. A., & Freeman, D. J. (1994). Gender differences in self-confidence and educational beliefs among secondary teacher candidates. Teaching and Teacher Education, 10(6), 647–658. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(94)90032-9

- Kömür, S. (2010). Teaching knowledge and teacher competencies: A case study of Turkish preservice English teachers. Teaching Education, 21(3), 279–296. doi:10.1080/10476210.2010.498579

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Language teacher education for a global society: A modular model for knowing, analysing, recognizing, doing, and seeing. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., Wernerson, A., & Thornberg, R. (2017). Resolving feelings of professional inadequacy: Student teachers’ coping with distressful situations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64, 270–279. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019

- Murray, F. B. (2008). The role of teacher education courses in teaching by second nature. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education: Enduring questions and changing contexts (pp. 1228–1246). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Namaghi, S. A. O. (2009). A data-driven conceptualization of language teacher identity in the context of public high schools in Iran. Teacher Education Quarterly, 36(2), 111–124.

- Richards, J. C., Ho, B., & Giblin, K. (1996). Learning how to teach in the RSA Cert. In D. Freeman & J. C. Richards (Eds.), Teacher learning in language teaching (pp. 242–259). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57, 1–22. doi:10.17763/haer.57.1.j463w79r56455411

- Shulman, L. S. (1998). Theory, practice, and the education of professionals. The Elementary School Journal, 98(5), 511–526. doi:10.1086/461912

- Tang, S. Y., Wong, A. K., & Cheng, M. M. (2016). Configuring the three-way relationship among student teachers’ competence to work in schools, professional learning and teaching motivation in initial teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 344–354. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.09.001

- Tang, S. Y. F. (2003). Challenge and support: The dynamics of student teachers’ professional learning in the field experience. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19, 483–498. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(03)00047-7

- Voss, T., Kunter, M., & Baumert, J. (2011). Assessing teacher candidates’ general pedagogical/psychological knowledge: Test construction and validation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(4), 952–969. doi:10.1037/a0025125

- Yan, C., & He, C. (2010). Transforming the existing model of teaching practicum: A study of Chinese EFL student teachers’ perceptions. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 36(1), 57–73. doi:10.1080/02607470903462065

- Yayli, D. (2012). Professional language use by pre-service English as a foreign language teachers in a teaching certificate programme. Teachers and Teaching, 18(1), 59–73. doi:10.1080/13540602.2011.622555

Appendix

Participants’ answers to interview questions

Last-year EFL student teachers’ evaluations of their teaching abilities