Abstract

This study aims to develop and glocalize a set of quality indices that can enhance the English language teaching learning output at Iranian private institutions. CIPP (Context, Input, Process, and Product) Model with a progressive/humanist approach was opted by the researchers as the main pattern of thought. This study used concurrent-mix method design. The data collection was conducted through random interviews of 75 Iranian EFL teachers. Also, a questionnaire was distributed to 250 Iranian EFL teachers. Then, the data obtained out of the interviews and the questionnaire were utilized to construct an English language teaching quality indices survey. The content and construct validity of the survey were double checked by seven experts in the field of Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) as well as Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis. The reliability of the survey along with its subscales was estimated by Cronbach Alpha. The final English Language Teaching Quality Indices Survey consisted of 13 constructs and 99 items. By calculating the mean of each construct, the most effective and prominent components that impact the quality of English Language teaching as “must” to be indices in any educational setting were analyzed. Results revealed that “Teachers’ Qualifications and Recruitment” and “Learners’ Needs” were considered as the most prominent indices that affect the quality of English language teaching. Therefore, the results of the study added practical solutions for quality enhancement to the present status under which Iranian private institutions are launched and supervised. Also, the rubric provides a common ground of reference for all the members involved in the educational setting to know what they are expected to do in order to offer a more qualitative enhanced education.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Researches have suggested that to enhance teacher quality and efficiency, institutions need to raise teacher education quality indices like: “Having higher admissible standards for teacher education programs, more rigorous course content in teacher education with increased emphasis on basic skills and subject matter competency testing for teacher certification”. This research has developed an English Language Teaching Quality Indices Survey using teachers’ perspectives. The aim was to provide a common ground of reference for all the members involved in the educational setting to know what they are expected to do in order to offer a more qualitative enhanced education. The last version of the survey consisted of four broad categories, 13 subcategories and 99 items. “Teachers” Qualifications and Recruitment” and “Learners’ Needs” were considered as the most effective components that impact the quality of English Language Teaching as “must” to be indices in any educational setting.

1. Introduction

1.1. Significance of the study

As a great deal of attention is paid to English as a Foreign Language teaching and learning in Iranian educational context and more particularly in the private sections, the current study is aiming to shed light on the importance of quality and what is meant by quality teaching and learning. In fact, quality enhancement is a dynamic term and process which needs to be looked upon and reconsidered continuously according to the century, needs and other technological and educational developments.

Baghazadeh Naini and Dastjerdi (Citation2014) have highlighted that not all the private English institutes act according to the scientific methods, scales, and the newest expertise obtained and worked on in the realm of Applied Linguistics. Moreover, as quality enhancement is a dynamic, ongoing process, all the institutes do need to “determine, verify, modify, and even revise” all the indices that impact the quality of their teaching, learning, and their educational system in general (Baghazadeh Naini & Dastjerdi, Citation2014, p. 1199). Besides, when managers, supervisors, and teachers are provided with a quality indices rubric they will clearly know what they are expected to do and what needs to be improved in their specific area of work. Consequently, the results of the study recommend some hints for teacher educators about the quality indices they need to follow in their training sessions and education. In reference, managers and supervisors working at English language institutions can obtain more insights about how English language teachers think and accordingly update the quality indices for their workplace.

1.2. Statement of the problem

Although English as a foreign language has an important role in Iran in most of the fields, neither the public sections like schools and universities nor the private sections have been able to enhance the quality of teaching and learning (Baghazadeh Naini & Dastjerdi, Citation2014; Sadeghi & Richards, Citation2015). Perhaps one of the reasons for having a low-quality education is due to the fact that there are no indices by which educational quality can be measured.

According to the review of the related literature, many studies have been conducted to find the reasons why teaching English hasn’t been successful in developing countries and more specifically in Iran in relation to the “formal (public) parts of education” that are schools and universities. Therefore, a set of quality indices has been proposed as a guidance to improve the quality of education at schools and universities (Keyzouri, Citation2007; Shafeea, Citation2002; Tabatabaeei & Loni, Citation2015).

On the other hand, a tiny space has been left for the private English language institutions to realize the extent they have been able to live up with the customers’ expectations and the effectiveness of teaching. Maybe, that’s because it is widely believed that private sections are successful in achieving their goals and the pre-set outcomes. Thus, according to the review of literature, there are very few comprehensive, unified rubrics that focus specifically on quality enhancement in order for the institutions to better understand how to act accordingly and promote the effectiveness of their system and output (Atai, Babaii, & Mousavi, Citation2016; Akbari & Yazdanmehr, Citation2011; Baghazadeh Naini & Dastjerdi, Citation2014; Gholami, Sarkhosh, & Abdi, Citation2016; Razmjoo & Riazi, Citation2006; Shishavan & Sadeghi, Citation2009).

In addition, based on a review of literature conducted by Akbari (Citation2015) about various problems related to teaching and learning English in Iranian context, it has become apparent that there are multidimensional reasons of why qualitative teaching and learning outcomes in our educational system is almost missing. The classification consisted of problems related to students, teachers, textbooks, teaching methods, language assessment, curriculum, and political problems.

1.3. Research questions

In reference to the points mentioned previously in the research, the study has aimed at finding the answers to the following research questions:

Q1. What are the existing quality indices in Iranian private English language institutions?

Q2: As an Iranian EFL teacher, what are your perspectives towards quality of language teaching in private institutions?

Q3: What are the most important indices that affect the quality of language teaching in private institutions, according to Iranian EFL teachers?

Q4: Does the designed English Language Teaching Quality Indices Survey enjoy validity and reliability?

Q5: Do the obtained quality indices have the same weight and importance according to the Iranian EFL teachers’ perspectives?

2. Literature review

2.1. National and international researches related to quality, quality indicesand quality enhancement

Considering teacher training programs as one of the first building blocks of establishing quality and enhancing the quality issues in an educational system, a study has been done by Nezakat- Alhossaini and Ketabi (Citation2013). As a result, a companion research has been conducted to compare and contrast EFL teacher training courses by focusing on countries like Iran, Turkey and Australia. The results have revealed that teacher training courses in Iran don’t act according to a pre-determined set of quality indices which directly affect quality and quality enhancement. Therefore, the authorities who are responsible for planning and holding teacher training courses in Iran need to revisit criteria such as “planning for study hours, course content, employment reconsiderations and the degree of practicality needed for such vocational practice of teaching” (Nezakat- Alhossaini and Ketabi, Citation2012, p.535). Turkey depicted to have the same aforementioned problems but Australia had a very exact pre-planned system of teacher training both for pre-service and in-service instructors.

In addition, another study conducted by Sallis (Citation2002), highlighted several indices as the origins for reaching quality in an EFL institution:” outstanding teachers, high moral values, excellent examination results, support of parents, business and the local community, plentiful resources, the application of the latest technology, strong and purposeful leadership, the care and concern for pupils and students and a well-balanced and challenging curriculum” (p. 53).

United Kingdom, as another country which hasn’t been successful in having a qualitative educational system, possesses an extremely slow pace in total quality management due to having very low marks (on part of students), financial issues and many complaints from parents, clerks and all the other members who are involved in the educational process. It is rare that universities in the United Kingdom are recognized for outstanding quality management issues. Therefore, Kanji, Malek, and Tambi (Citation1999) have conducted a study mainly focusing on the role of total quality management in UK higher education institutions. To gain the objectives of the study, the researchers have tested the idea of how Total Quality Management principles and concepts can be estimated as a mean to evaluate the quality of the institutions on different aspects of the internal process. The outcome of the paper has revealed that changes made in the crucial success factors mentioned above impact the institutions’ business efficiency.

Another study has been conducted by Being-fang (Citation2000) about quality-oriented education within a TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) context in China. The researcher concluded that an instructor not only should delve into the learners’ competence knowledge but also into their psychological and ideal definition of quality. Also, the results revealed that highlighting the communicative aspects of students’ ability, constructing a brilliant learning environment, and helping learners to establish their own model of learning can surely promote the quality of learning outcome.

Many studies have suggested that to enhance teacher quality and efficiency, institutions need to raise the quality indices related to teacher education like: “ Having higher admissible standards for teacher education programs, more rigorous course content in teacher education, with increased emphasis on subject matter and basic skills and subject matter competency testing for teacher certification” (Ballou & Podgursky, Citation1997, p. 2). Regarding teachers’ recruitment in private and public sectors, it has become vivid that the private sectors have been much more successful in applying a more efficient process of recruiting (Ballou & Podgursky, Citation1997). Also, it has been proved that private institutions do offer a more engrossing and supportive environment.

In the study conducted by Estaji (Citation2010), an assessment rubric for estimating students’ learning outcomes has been constructed to promote assessment quality. Consequently, a survey has been created to discover learners’ perspectives towards the rubric by running semi-structured interviews. “Focusing on their effort, producing work of higher quality, earning a better grade, feeling less anxious about an assignment and guiding feedback from others” were among the learners’ perspectives. Also, Walser (Citation2011) has conducted a research study in which the application of a standard scoring rubric for estimating the quality of university student assignments and projects has been practiced. The outcome of the study pinpointed that the rubric could offer vivid expectations, good feedback, progressive monitoring, and student motivation regarding instructional objectives.

In addition, a Master’s Thesis has been conducted by Althuhami (Citation2011) to evaluate teachers’ performances in the light of quality standards in Saudi Arabia. The research consisted of four aims: “1) identifying the most appropriate standards of EFL Saudi teachers’ performance in the light of quality standards, 2) designing an objective and comprehensive evaluation rubric based on quality standards to evaluate EFL Saudi intermediate teachers’ performance, 3) determining to what extent quality standards are exhibited in the performance of EFL Saudi teachers in the intermediate stage with more than 5 years of experience, and 4) determining whether there are statistically significant differences among EFL Saudi teachers’ performance related to experience” (p. II). The results of the study revealed that teachers’ performances were much better as a result of employing quality standards and evaluation rubrics.

2.2. Theoretical framework of the study

There are several traditions or theories focused on education and quality which may vary according to the context of the study or the way quality in education is viewed. They could be mentioned as quality in humanistic approach, behaviorist approach, indigenous approach, critical approach, adult education approach, economist approach, and the progressive/humanist approach (Barrett, Duggan, Lowe, Nikel, Ukpo, Citation2006; Jain & Prasad, Citation2018). The progressive/humanist tradition focuses more on the educational process. Therefore, to measure quality, one needs to check out the criteria or the processes that the institutions and the classes go through. Also, notions like democracy, learner-centered pedagogies, literacy, numeracy and cognitive skills are extremely pinpointed regarding the aforementioned tradition (Barrett et al., Citation2006). That is, qualitative learning best takes place when learners are actively involved in their learning process by moving towards a social action of a self-construction of meaning, which greatly highlights the humanism and constructivism theories towards learning and education (The Dakar Framework for Action, Citation2000).

Moreover, CIPP evaluation model, which was proposed by Stufflebeam (Citation2002b), is considered as another well-known theoretical model for many studies focused on the quality of either summative or formative evaluation of educational elements in a system from a holistic perspective. Also, the aspect which differentiates this theoretical model from the others is that it places a significant emphasis on context. Besides, the present model utilizes “Context, Input, Process and Product” as the four indices for evaluating teaching and learning along with all the other indices needed as means for quality development. That is, 1) Context evaluation focuses on goals, 2) Input evaluation focuses on plans, 3) Product evaluation focuses on outcomes and 4) Process evaluation focuses on actions. As a result, the researchers decided to opt CIPP model as the main framework of the study because it focuses on “context”. Therefore, the aforementioned model has been applied for setting the categories of the questionnaire under each specific construct, CIPP, with the progressive/humanist approach.

Moreover, except for the stated model and approaches, there is not a comprehensive glocalized rubric for quality and quality enhancement. Therefore, the researchers utilized studies conducted by Language Learning Services outside Formal Education —Requirements (Citation2015), Saglam & Sali (Citation2013), Guidelines for Quality in Language Teaching (Citation2009–2011), Wenglinsky (Citation2000), Shishavan and Sadeghi (Citation2009), Ballou and Podgursky (Citation1997), Podgursky and Springer (Citation2006), Fredriksson (Citation2004), Satterlee (Citation2010), Atai, Babaii & Mousavi (Citation2016), Dakar Framework (Citation2000), Grisay and Mahlck (Citation1991), and Akbari and Yazdanmehr (Citation2011) as patterns of thought in regard to how to develop the constructs and items of the present questionnaire.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

In the present study, sample population was selected from Iranian upper-intermediate EFL teachers, teaching at various private English language institutions. The data were collected from Khorasan Razavi, Tehran, Khorasan Shomali, Khorasan Jonobi, Golestan, Qazvin, Hamedan, Fars, Illam, Ardebil, and Khozestan provinces in Iran. For the qualitative phase of the research, 75 male and female instructors were randomly selected to gain data through interviewing face to face, or sending texts or audio through social networking sites.

Considering the quantitative phase of the study, the sample was determined based on the whole population of teachers utilizing Krejcie and Morgan (Citation1970) sample size table. Therefore, a total of 250 ELT teachers including 174 males (69.6%), and 76 females (30.4%) participated in this study. Teachers had different ranges of years of teaching experience: 42 (1–5), 84 (6–10), 76 (11–15), and 48 over 15. They had different academic majors: 176 English Language Teaching (70.4%), 22 English Language Literature (8.8%), 39 English Language Translation (15.6%), and 13 other majors (5.2). In addition, they were in different age ranges: 72 (20–30), 136 (31–40), 37 (41–50) and 5 (Over 50). Moreover, participants had different academic degrees: 66 BA (26.4%), 130 MA (52%), 54 PhD (21.6%).

3.2. Data collection methods

The researchers utilized various methods of data collection for the present study. Each method is elaborated on through the following sections.

3.2.1. Structured interview

Random structured interviews were held among 75 male and female teachers. In addition, the interviews were in English and they were conducted either face to face or via text/audio within social media sites. Also, the average time for each interview was about 10 min. The answers were recorded by the researchers and notes were taken while the participants were elaborating on the answers. Therefore, the interview questions were:

Q1: As an Iranian EFL teacher, what are your perspectives towards quality of language teaching in private institutions?

Q2: What are the most important indices that affect the quality of language teaching in private institutions, according to Iranian EFL teachers?

A thematic, deductive approach for the analysis of data was employed. The obtained results were utilized for constructing the ELTQI Inventory. As a result, this procedure helped the researchers to scrutinize the content validity of the questionnaire.

3.2.2. English language teaching quality indices survey (ELTQIS)

This study used a survey method to gather information about Iranian EFL teachers’ perspectives on quality indices required for private English institutions’ educational system. Therefore, the survey consisted of three sections. The first part was a bio-data category which elicited personal information from the participants. The second part consisted of a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire in English with choices ranging from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree”. The third part was an open-ended question asking the respondent to write any further indices that haven’t been mentioned in the inventory. The results were analyzed by means of thematic analysis.

The validity of the questionnaire was checked by seven TEFL experts, expert validation, and utilizing Exploratory Factor Analysis using SPSS Software. In addition, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was run to see whether the thirteen-factor solution obtained in EFA can be confirmed. The last version of the inventory consisted of four broad categories, CIIP Model, 13 subcategories and 99 items. Also, the reliability was estimated by Cronbach Alpha (.95).

3.2.3. Organization websites which issue private institutions with english language teaching license

The third method of data collection was searching the organization websites in regard to which the candidates can read the requirements and regulations under which they can obtain a license and establish a private English language teaching institution. The name and the link for these organization websites are: 1) Ministry of Education (www.medu.ir, November Citation2018), 2) Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (https://www.farhang.gov.ir, Citation2018), 3) Ministry of Science, Research and Technology (http://www.msrt.ir, Citation2018). That is, the aforementioned step was taken to get the required data in regard to the first question of the study: What are the existing quality indices in Iranian private English language institutions?

3.3. Data analysis methods

The obtained data of the study were analyzed through various ways. Each one is explained fully in the following sections.

3.3.1. Qualitative data analysis

The qualitative data for the present study were gathered in four ways: 1) interviews 2) the open-ended question at the end of the English Language Teaching Quality Indices Survey 3) reviewing the related literature 4) reading the information presented in the organization websites which issue private institutions with English language teaching licenses.

For numbers three and four, the quality indices were directly and exactly mentioned in the sources. Therefore, they were extracted and utilized in the present research. But in regard to the first and third ways of data collection, thematic analysis was utilized. Thematic analysis provides an exact description of the emergent themes and patterns (Boyatzis, Citation1998; Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). According to the description in their study, they have provided six steps for conducting thematic analysis: 1) familiarizing with the data 2) generating initial codes 3) searching for themes 4) reviewing themes 5) defining and naming theme 6) producing the report. As a result, the researchers followed the very exact steps to conduct the thematic analysis of the present study.

3.3.2. Quantitative data analysis

For the quantitative data analysis, first the researchers estimated the normality of data distribution by employing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The reason for opting this test was that the sample size was more than 50 (Wayne, Citation1990). In order to assure the construct validity of the test, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with principal component analysis and varimax rotation was run. Following EFA, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was employed to see whether the 13-factor analysis solution obtained in EFA can be confirmed. For checking the reliability of the designed questionnaire with Likert-type scale (polytomous scores), Cronbach alpha was employed. At the end, descriptive statistics of the English Language Quality Indices Survey was computed including the mean and the standard deviation scores.

3.4. Procedure

The overall data collection procedure ran from May 2018 to March 2019. Each of these procedures is elaborated on fully through the following lines.

3.4.1. Questionnaire construction

In order to conduct the present study, first the researchers utilized a structured interview among the participants of the research, 75 Iranian EFL male and female teachers teaching at the private institutions. The aforementioned data were collected in a variety of ways including: 1) a 10-min face to face interview, 2) text messages sent through social media applications, and 3) a 10-min voice or audio message. That is, ALL participants were given the same structured questions but could respond in a method of choice.

While the responses regarding the qualitative phase of the study were being collected, the researchers simultaneously covered the available review of the related literature to gather the national or international quality indices constructed for enhancing education and more specifically English Language Teaching. In addition, the researchers talked in person to a couple of managers running English language institutions in Iran. The purpose was to find about the quality indices under which managers are provided with a license to launch an institution and the supervising procedure they go through afterwards. Therefore, some related forms were handed to the researchers by the managers. Also, the researchers searched the sites related to Ministry of Education, Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance and Ministry of Science, Research and Technology to get much more additional information. That is, the aforementioned steps were taken to get the required data in regard to the first question of the study: What are the existing quality indices in Iranian private English language institutions?

By the time the essential data were gathered through the three aforementioned ways, the researchers analyzed the obtained information. That is, the data gained through the review of the literature and the interview phase were analyzed and then categorized by means of the emergent themes to be able to fit into the inventory and to be well set under each construct of CIPP Model. The purpose behind such a step was to develop a glocalized quality rubric.

Besides, thematic analysis or the deductive approach was the procedure through which the data analysis was conducted (Boyatzis, Citation1998). A decision was then made concerning the quality constructs and indices in addition to the identification of categories which were made according to the set theory and the previous research findings. In addition, to help insure reliability, three other assistant TEFL professors who were experienced in the field of qualitative research were asked to review the chosen themes and constructs for double-checking the quality indices. Consequently, the needed modifications were applied. What is worth mentioning here is that dynamic assessment throughout the research for developing the inventory was done by the supervisor of the study by means of holding ongoing meetings (Rossman & Rallis, Citation1998).

As a result, the first draft consisted of 25 categories and 275 unique items. Criteria were validated by seven experts in the field of Teaching English as a Foreign Language, associate and assistant professors. Consequently, according to the aims of the present study, some of the categories and items were extracted from the questionnaire. The comments received were primarily related to sentence wording, coherence of all the items under each construct, and not having repeated items and categories with the same notions. All the comments were applied and modified in the survey. Also, as some of the constructs were mostly related to the “services” an institution offers and not related to the qualitative teaching and learning, they were recognized through expert validation and afterwards omitted. Consequently, the final version of the inventory before doing the Exploratory Factor Analysis consisted of 14 constructs and 113 items. But right after EFA was conducted, the overall number of indices were 13 along with 99 items. The reasons for such omissions are elaborated on in the “Results” section of the study.

Some of the constructs that were omitted were: “When Designing an English Course attention must be Paid to Evaluating and Assessing the English Teaching Services, Advertising about the English Educational Services, Issuing a Receipt, Educational Function, The Educational Performance and Human Resource, Financial and Official Function, The Function of Place, Equipment, Health and Security”. Moreover, the category”21st Century Skills” was added as a new construct and all the items that were focusing on various aspects of the aforementioned issue throughout the questionnaire were listed under the same section. Besides, the categories of “Recruitment” and “Teachers’ Qualifications” as well as the “Institutional Rules and Regulations” and “Fair Payment” were among some of the other categories which were merged as they had the same underlying construct. Afterwards, the reliability of the questionnaire was checked by Cronbach Alpha. And, its validity was estimated by employing EFA and CFA. The results are elaborated on in the result section of the present research.

What is worth mentioning is that the present quality indices rubric was constructed according to the general steps of developing quality rubrics mentioned in the previous parts of the study. And also, the researchers have opted a domain-based approach with an endorsement way for constructing the quality indices as for the constructs and items to be more concrete, understandable and practical (Iranian National standards-Structure and Drafting, Citation2014; Kuhlman & Knezevic, Citation2013).

3.4.2. Data collection

The quantitative phase of the research commenced by randomly distributing the questionnaire to 250 Iranian EFL male and female instructors teaching at private English language institutions. The surveys which were handed into the participants in person took 15 min to be answered.

In addition, the results were analyzed by descriptive analysis using the mean and standard deviation of each index to reveal the weight or the importance of each of the quality index. Then, based on the quality indices obtained through various phases of the study, the researchers developed a glocalized prospective rubric of quality enhancement which consisted of quality indices needed for private Iranian English institutions to reach to a quality teaching, learning output.

3.5. Study design

As the aim of the study was to search for the quality indices required for the educational system of private English institutions in Iran and then develop a prospective quality enhancement rubric by utilizing both qualitative and quantitative processes, structured interviews, and ELTQIS; the researchers have deemed the design of the study to be a concurrent mixed-method one. In fact, this study design provides the researchers with the chance of double-checking and verifying the obtained results. Therefore, researchers can access participants’ deep thoughts except for the quantitative data (Schoonenboom & Johnson, Citation2017). The aforementioned points were the advantages of the conducted study for the researchers.

4. Results

4.1. Qualitative data analysis

4.1.1. The existing quality indices in the iranian private english institutions

In regard to the first research question which focuses on the existing quality indices in Iranian private institutions, the analysis of results illustrated the following points (according to the three organizations which issue licenses for establishing private English language institutions in Iran) (www.medu.ir, November 2018; https://www.farhang.gov.ir; http://www.msrt.ir):

the manager has to have teaching experience which could be contractual, promissory or obligatory,

he has to be an instructor,

he has to have managerial experiences,

he has to have quota of sacrificial work,

he has to be one of the honorable family of martyrs,

he has to have educational background and certificates,

he has to have teaching and researching background,

he has to have compulsory attendance,

he has to be a donor in establishing schools,

he has to have a bachelor of non-governmental university.

Also, the space for the institutes’ substructure area shouldn’t be less than 200 square meter, the institute requires to have the newest technological devices and a good air conditioning.

By the time the contract for establishing the English language institute is obtained and it has started to work and hold classes, observation processes by the organizations which issue licenses for English language institutions commence. After interviewing the managers of several English language institutions, it became apparent that most of these observations focus mainly on Islamic issues rather than the quality of teaching and learning in classes. That is, the majority of the observations look for: 1) the type of classes that are held in the English language institute (not to be mixed), 2) to make sure that gender-specific classes are held on two different buildings, 3) female teachers just teach to female students and male teachers are allowed to teach to male students, and 4) the teachers should have an acceptable appearance. Besides, the inspectors sent by these organizations to English language institutions are not the persons who know English which is considered as one of the other shortcomings of the aforementioned process. Also, the managers mentioned that there is no serious filter for the advertisements the English language institutes make and at times the information presented in their commercials isn’t based on reality. The only issue that matters to the inspectors is how the institute has made use of these organizations’ names in the advertisements. It is worth mentioning that the stated points happen more frequently in smaller cities. That is, in bigger cities like Mashhad the observing issues are nearer to the standard procedures, according to the interviews done. As the last point, these observations are done almost two times in a year, the detailed result of which is sent to the aforementioned organizations.

In addition, according to the aforementioned websites and the obtained observation form, almost half of the items in the survey focus on the above-mentioned points as well as: 1) paying the required taxes on time, 2) the annual license and how to repeat it for the next year, 3) answering to the received letters from these offices soon and the like. Only few points focus for example on paying teachers’ salary on time, about the class size and how equipped they are or other quality issues which affect the teaching learning output.

4.1.2. Iranian EFL teachers’ perspectives towards quality of language teaching in private institutions

The results gained after the analysis of participants’ perspectives highlighted the following points. Quality in English language teaching takes place when:

objectives and aims of education as well as the course are met,

the focus of teaching is on learning social skills so learners can interact and cooperate well in the real world,

learning of subject materials happen,

learners benefit from equal teaching and learning opportunities,

students’ personalities and abilities are flourished,

teaching and learning is economically productive,

teaching and learning contributes to the society,

learning happens in the shortest time,

taught materials are fixed in learners’ long-term memory,

an educational system is managed well,

customers’ satisfaction is met,

customers’ needs and demands are met,

practical teaching and learning happen,

teaching syllabus is based on quality rather than quantity,

teaching has got long-term effects on students and makes them motivated and autonomous,

teaching helps students reach their short term and long-term goals,

teaching is in accordance to the learners’ psychological and physical needs,

teachers utilize the best teaching techniques and resources,

teachers can participate in efficient workshops to update their knowledge in an environment which is friendly and dynamic,

teaching strategies are chosen according to the course goals,

qualified and experienced teachers who can perfectly transmit the subject matter to students,

the educational system and its components are updated within specific time periods,

constructive steps are taken in regard to the feedbacks received in relation to teaching learning output.

4.1.3. The most important indices that affect the quality of english language teaching in private institutions according to iranian EFL teachers

Moving towards the third research question, the analysis of results revealed that: 1) English Language Learning Environment, 2) Learners’ Needs, 3) Organizational Culture, 4) Textbooks and Supplementary Materials, 5) Instructional Aids and Technology, 6) Institutional Rules and Regulations, 7) Educational Supervisor, 8) Recreational Activities, 9) Institute Management System, 10) Continuing Professional Development, 11) Teaching Activities and Methodologies, 12) Teachers’ Qualifications & Recruitment, 13) 21st Century Skills and Assessment Procedure were among the most recurrent themes/constructs.

What is worth mentioning here is that most of the constructs, whether the components themselves or the underlying items, were among the ones which were thoroughly recurrent throughout the review of the related literature or the ideas gained out of the various interviews. The fact which cross-checks the content validity of the research and the rubric.

On the other hand, moving towards localizing the quality indices questionnaire, some of the constructs mentioned through the interviews shared almost no similarities with the review of the literature. That is, “Recreational Activities” and “Educational Supervisor” constructs, as far as the review of the related literature reveals, are not considered as the indices to affect the quality of language teaching. This could be of two reasons. First of all, as it is mentioned throughout the present research, most of the studies conducted to increase the level of English language teaching quality mainly focus on very limited indices, and not on proposing a comprehensive quality rubric (Atai, Babaii, & Mousavi, Citation2016; Akbari & Yazdanmehr, Citation2011; Baghazadeh Naini & Dastjerdi, Citation2014; Gholami et al., Citation2016; Razmjoo & Riazi, Citation2006; Shishavan & Sadeghi, Citation2009). The second reason may be due to the fact that some of the studies conducted in the realm of quality teaching and learning to reach to the required quality indices are based upon the managers, supervisors or the ones who are in the outer circle of education (Iranian National standards-Structure and Drafting, Citation2014; Language Learning Services outside Formal Education –Requirements, Citation2015). That is, the ones who are not directly involved in teaching and learning in the classroom. This is the point which has made the present study different from the others and therefore has shifted the focus towards teachers.

One of the other differences between the present glocalized rubric and the others found in the review of the literature is the construct named”21st Century Skills”. That is, the items sorted under the aforementioned category were distributed under various categories in the previously conducted studies. The only difference was the name of the construct opted by the present researchers. The reason was that, as mentioned previously in the study, the approach towards developing the present construct was a progressive/humanism one which highly focuses on making 1) learners or the other educational members directly involved in the process of education, 2) learners self-directed, 3) learners autonomous and 4) learners as the ones who can act beyond the classroom walls as good citizens for their society (Motallebzadeh & Kafi, Citation2015).

Moreover, as the constructed questionnaire consisted of one open-ended question with the aim of asking the participants about any further English language teaching indices that have not been included in the rubric, the participants added the following points:

1) Paying attention to learners’ ideas about which specific teacher they like to have classes with, 2) giving learners’ enough freedom about codes of dressing, 3) paying attention to learners’ personalities, 4) supporting learners’ at home by their parents. These were among the factors that could be set under the construct of “Learners’ Needs” in the present rubric. Also, regarding the construct of the “Educational Supervisor” the following points were mentioned: 1) Observing the classes by installing cameras in classrooms, 2) informing the observation sessions to teachers in advance, 3) the educational supervisor along with some other expert teachers in the institution do the observations interchangeably in order to gain objectivity. In addition, providing students with the required textbooks in an easy, quick way in the institutions could be considered as another stated factor by the participants. Of course, the aforementioned issue doesn’t necessarily affect the quality of teaching learning output as it is one of the services an institution may offer.

4.2. Quantitative data analysis

4.2.1. Kolmogorov-smirnov test

To check the normality of data distribution, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed. This test is used to check whether the distribution deviates from a comparable normal distribution. If the p-value is non-significant (p> .05), we can say that the distribution of a sample is not significantly different from a normal distribution, therefore it is normal. If the p-value is significant (p< .05) it implies that the distribution is not normal. Table presents the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Table 1. The final version of the English language teaching quality indices survey

Table 2. The results of K-S test

Table 3. Results of EFA for the English Language Teaching Quality Indices Survey and its Subscales.

Table 4. Goodness of fit indices

As it can be seen, the obtained sig value for all variables is higher than .05. Therefore, it can safely be concluded that the data is normally distributed across all the variables.

4.2.2. Validity and reliability of the english language teaching quality indices survey (ELTQIS)

In order to assure the construct validity of the test, the fourth research question, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with principal component analysis and varimax rotation was run. To find out whether employing factor analysis to extract latent variable was appropriate the Kaiser—Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of Sampling Adequacy was employed. The assumptions of EFA were met in this study. KMO was .80 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant. Scree plot and eigenvalues above 1 were examined to determine the number of factors. Moreover, the highest loading for each item was considered as the appropriate factor for that item. Also, there is a consensus among most statisticians (Pallant, Citation2007; Spada, Barkaoui, Peters, So, & Valeo, Citation2009) that if the value of an item is less than 0.3, that item is suspicious of measuring something else rather than the construct under study. Therefore, it should be omitted. As a result, cross-loadings and loadings less than .30 were removed. Results of the EFA can be seen in Table .

As Table shows, the 13 factors can be regarded as the 13 constructs that the test claims to measure namely: 1) English Language Learning Environment (4 items), 2) Learners’ Needs (4 items), 3) Organizational Culture (4 items), 4) Textbooks and Supplementary Materials (6 items), 5) Instructional Aids and Technology (3 items), 6) Institutional Rules and Regulations (3 items), 7) Educational Supervisor (14 items), 8) Institute Management System (11 items), 9) Continuing Professional Development (5 items), 10) Teaching Activities and Methodologies (6 items), 11) Teachers’ Qualifications and Recruitment (21 items), 12) 21st Century Skills (12 items), 13) Assessment Procedure (6 items). Moreover, 14 items were removed because of low loadings or cross loadings (q5, q8, q17, q37, q42, q44, q51, q55, q57, q79, q83, q91, q100, q110). Therefore, one subscale (Recreational Activities) was deleted and thirteen subscales remained for further analysis.

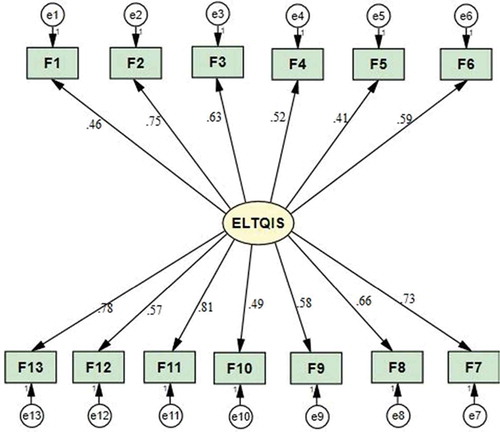

Following EFA, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was run to see whether the thirteen factor solution obtained in EFA can be confirmed. For this purpose, CFA was run to assess the fit of the model. Based on the CFA analysis, the association between each sub-factor and overall variable was analyzed and the results can be seen in Figure .

Figure 1. CFA model of ELTQIS.

Note: F1: English Language Learning Environment, F2: Learners’ Needs, F3: Organizational Culture, F4: Textbooks and Supplementary Materials, F5: Instructional Aids and Technology F6: Institutional Rules and Regulations, F7: Educational Supervisor, F8: Institute Management System, F9: Continuing Professional Development, F10: Teaching Activities and Methodologies, F11: Teachers’ Qualifications and Recruitment, F12: 21st Century Skills, F13: Assessment Procedure.

As the model of CFA shows, F11 has the highest loading (B = .81) and F5 has the lowest loading (B = .41). Based on the figure all 13 factors were confirmed. To check the model fit, goodness of fit indices were used. Table shows the goodness of fit indices for CFA model.

As Table shows, all the goodness of fit indices are within the acceptable range. Therefore, the ELTQIS enjoyed perfect validity with empirical data.

Moreover, in order to find the reliability of the designed questionnaire with Likert-type scale (polytomous scores), Cronbach alpha was employed. Table summarizes the information obtained from Cronbach alpha analyses. Salvucci, Walter, Conley, Fink, and Saba (Citation1997) gave a criterion to interpret reliability coefficient as an internal consistency index: “The range of reliability measures are rated as follows: a) Less than 0.50, the reliability is low, b) Between 0.50 and 0.80 the reliability is moderate and c) Greater than 0.80, the reliability is high” (p.115).

Table 5. Results of cronbach alpha indexes after validation

As can be seen, results of Cronbach analyses showed that the designed questionnaire gained acceptable indices of Cronbach reliability ranging from .77 to .92 for all 13 subscales which are moderate and high reliablities.

4.2.3. The weight and importance of the obtained quality indices according to the iranian EFL teachers’ perspectives

Table presents descriptive statistics of ELTQI Survey, the fifth research question, including the mean and the standard deviation scores. The comparison of these scores appears in the following pages.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics of English language teaching quality indices survey

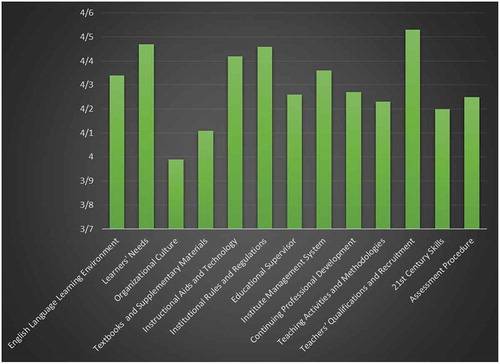

Because the number of items was different in the various subscales of the questionnaire, an average item score was computed for each sub-construct, ranging from 1 to 5. The possible range of score for English Language Learning Environment, Learners’ Needs, and Organizational Culture with four items is between 4 and 20, for Textbooks and Supplementary Materials, Teaching Activities and Methodologies, and Assessment Procedure with 6 items is between 6 and 30, for Instructional Aids and Technology and Institutional Rules and Regulations with three items is between 3 and 15, for Educational Supervisor with 14 items is between 14 and 70, for Institute Management System with eleven items is between 11 and 55, for Continuing Professional Development with five items is between 5 and 25, for Teachers’ Qualifications and Recruitment with 21 items is between 21 and 105, and for 21st Century Skills with 12 items is between 12 and 60. As the table shows, among the 13 indices of the questionnaire, Organizational Culture (3.99) has the lowest mean score and Teachers’ Qualifications and Recruitment (4.53) has the highest mean score. Figure shows the difference between the subscales of the questionnaire.

5. Discussion & conclusion

According to the goals of the research which investigated the current status of Iranian private English institutions and then proposed a glocalized quality enhancement rubric, various significant discussions and conclusions can be drawn upon. As it has been mentioned in the results section, the three organizations under which licenses for English language institutions can be obtained, mostly focus on issues such as 1) paying the taxes on time, 2) replying to the letters received from these organizations on time, 3) informing the organizations about the exact number of learners they have, 4) paying attention to teachers’ and learners’ appearance, 5) not assigning teachers for opposite sexes, 6) not having mixed-gender classes, 7) holding classes for each specific sex on separate buildings or days, and 8) how the English language institutes use the name of these organizations in their advertisements (www.medu.ir, November 2018; https://www.farhang.gov.ir; http://www.msrt.ir). These are among the very prominent factors of why most of the institutions cannot reach to a qualitative, enhanced teaching learning outcome. The reasons why quality is not assured throughout the educational process of English language teaching institutions. This resultant outcome can be due to the fact that the aforementioned indices fall under the managerial or political realm which do not focus on the needs of the inner circle (teachers, students, supervisors and the like). This can be in line with the findings mentioned in researches conducted by Baghazadeh Naini and Dastjerdi (Citation2014) that not all the private English language institutes act according to the scientific methods, scales, and the newest expertise obtained and worked on in the realm of Applied Linguistics. Of course, it has to be stated that these organizations take into account some quality indices that affect the educational processes positively but they are not as highlighted as the other aforementioned indices. That is, these organizations do not closely observe the educational outcome of the institutions. To realize whether learners receive the required quality related to all the educational contexts and factors or not, whether teachers are practically qualified or not except for the certificates they have. And, one of the reasons why these points are not observed and estimated in efficient, consistent ways is that at times, especially in smaller cities, the organization spectators sent to the target English language institutions do not know English themselves or maybe they are not an expert in the field to provide the institution with solutions (As mentioned through the interviews conducted with the managers of several English language institutions).

Besides, as EFL teachers who work in private English language institutions are not satisfied with their workplaces, the organizational culture, the salary as well as not being involved in making educational decisions are among some of the other critical factors of why instructors do not work wholeheartedly in their workplace. Therefore, EFL teachers do not care about learners’ learning outcome or even not caring about spending time, money, and energy on continuing their professional development. The point which most of the managers lack having enough focus on (Yilmaz & Altinkurt, Citation2011, p. 645). Moreover, managers of English language institutions can be majored in various fields of study except for ELT and in case they have the other criteria needed for issuing an institution license, they are easily provided with the allowance. This can be one of the other reasons of not paying attention to hiring qualified teachers and holding workshops and seminars for continuing the professional development of teachers. And in case the supervisor is well qualified, they can hardly reach to a common ground of what specific qualitative factors they need to act accordingly to enhance the quality of their educational outcome (Baghazadeh Naini & Dastjerdi, Citation2014, p. 1199).

Also, there are institutions which care about quality teaching and learning and they try to enhance the educational system they work in. For these specific cases, two issues arise. The first one is that in case they want to act according to educational quality indices, some of them are developed by using the managers’, the head of the ministry of education or the supervisors’ ideas towards quality and what constitutes that. Consequently, they do not consider teachers’ and learners’ perspectives who are directly involved in the process of education (Iranian National standards-Structure and Drafting, Citation2014; Language Learning Services outside Formal Education—Requirements, Citation2015). The second problem which may be pinpointed in this regard is that the quality indices present in the review of literature are mainly focusing on very limited indices, and not proposing a comprehensive quality rubric (Atai, Babaii, & Mousavi, Citation2016; Akbari & Yazdanmehr, Citation2011; Baghazadeh Naini & Dastjerdi, Citation2014; Gholami et al., Citation2016; Razmjoo & Riazi, Citation2006; Shishavan & Sadeghi, Citation2009). These are among the very prominent gaps found in the review of the related literature by the researchers which inspired them to conduct the present study.

In addition, Iranian teachers’ definition of “quality” in English language teaching well supports the theoretical model and approach of the present study, CIIP Model with progressive/humanist approach (Barrett et al., Citation2006; Jain & Prasad, Citation2018; Stufflebeam, Citation2002b).

All in all, the results of the present research provide a prospective set of quality enhancement indices for private institutions as a common ground of reference to act accordingly. That is, as proved in the review of the related literature, all these 13 indices do affect and promote the quality of teaching and learning as well as obtaining customers’ expectations (Language Learning Services outside Formal Education —Requirements, Citation2015; Saglam & Sali, Citation2013; Guidelines for Quality in Language Teaching, Citation2009–2011; Wenglinsky, Citation2000; Shishavan & Sadeghi, Citation2009; Ballou & Podgursky, Citation1997; Podgursky & Springer, Citation2006; Fredriksson, Citation2004; Satterlee, Citation2010; Atai, Babaii & Mousavi, Citation2016; Dakar Framework, Citation2000; Grisay & Mahlck, Citation1991; Akbari & Yazdanmehr, Citation2011). Besides, the construct of “Recreational Activities” was omitted after conducting the data analysis by Exploratory Factor Analysis, SPSS Software. This was a highly recurrent theme through the held interviews that teachers believed it affects the quality of teachers’ work.

Considering the weight and importance of each of the indices according to the participants’ perspectives, “Teachers’ Qualifications & Recruitment” gained the highest importance, the result of which is in line with the studies conducted by Shishavan and Sadeghi (Citation2009), Akbari and Yazdanmehr (Citation2011) and Guidelines for Quality in Language Teaching (Citation2009–2011). These results are well supported by the outcome presented through CFA model. That is, F11 (Teachers’ Qualifications & Recruitment) gained the highest loading too (B = .81). Secondly, “Learners’ Needs” is the other index that teachers believed has great impacts on the quality of English language teaching (Guidelines for Quality in Language Teaching, Citation2009–2011; Iranian National standards-Structure and Drafting, Citation2014, Citation2014; Sağlam & Salı, Citation2013). It has to be mentioned that “Learners’ Needs” index deeply supports the theoretical background and approaches taken for the present study. And next in importance is “Institutional Rules & regulations” which is well highlighted in studies conducted by Ballou and Podgursky (Citation1997), Podgursky and Springer (Citation2006) and Fredriksson (Citation2004). What is very interesting here is that through the qualitative phase of the data collection, one of the other recurrent themes that teachers insisted on was the “fair payment and raise” in their salary as a crucial point which affects the quality of their teaching. The item which is categorized under the aforementioned construct. On the other hand, the index of “Organizational Culture” considered to be the least important construct that affects the quality of education from teachers’ point of view, an outcome which didn’t share similarities with the study conducted by Satterlee (Citation2010).

In addition, by analyzing the data to find the indices with the greatest weight and importance, the researchers aimed at proposing the “must to be” indices in any educational setting as a shortcut or as a faster technique for gaining the minimum level of quality.

Over and above, this research can propose many ways to boost the quality of the educational settings in general and teaching and learning outcome in particular. That is the mix-method design which aimed at collecting teachers’ ideas about the required quality indices as well as the indices present in the literature review could propose a comprehensive glocalized quality indices rubric for enhancing the present status of English language teaching from various perspectives. Therefore, the results of the study can help managers, supervisors, and teachers with some general guidelines to follow in order to enhance the quality of English language teaching in every respect. Moreover, pursuing the obtained indices by the members in the institutions can lead to professional development as a result of following the best practice. Also, by suggesting a prospective quality enhancement rubric, the consumers’ needs will be met much more closely. This will lead to a higher quality teaching learning output. Consequently, the results of the study recommend some hints for teacher educators about the quality indices they need to follow in their training sessions and education. In reference, managers and supervisors working at English language institutions can obtain more insights about how teachers think and then update the quality indices for their workplace accordingly.

5.1. Limitations & future research directions

Manifestly, as it is apparent, some (De) limitations are inevitable which may be a hint for further investigations in the field. Among all, a longitudinal study can be conducted with the aim of applying the present quality indices in an institution to check out whether quality enhances after a course of study and across time or not. Also, a set of quality indices can be developed from learners’ (supervisors’ or managers’) perspectives to compare the results of the present study into account and then develop a rubric which is a combination of both. Moreover, a research can be conducted to construct a glocalized quality indices for the contexts of Iranian public schools or universities.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zahra Kafi

Zahra Kafi is a PhD candidate in TEFL at Islamic Azad University of Torbat-e-Heydarieh, Iran. Her prominent fields of research are the quality aspects of teaching and learning, the sociolinguistics criteria towards teaching and learning and teacher education and development.

Khalil Motallebzadeh

Khalil Motallebzadeh is an associate professor at Islamic Azad University of Torbat-e-Heydarieh, Iran. He has so many publications in teacher education, language testing and e-learning. Besides, he is a master trainer of the British Council since 2008.

Hossein Khodabakhshzadeh

Hossein Khodabakhshzadeh is an Assistant professor at Islamic Azad University of Torbat-e Heydarieh, Iran. His research interests are in ELT, FLA, and SLA.

Mitra Zeraatpisheh

Mitra Zeraatpisheh is an assistant professor at Islamic Azad University of Mashhad, Iran. Her research interests include SLA, linguistics, teaching methodologies, and teaching skills.

References

- Akbari, R., & Yazdanmehr, E. (2011). EFL teachers’ recruitment and dynamic assessment in private language institutes of Iran. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 8, 30–51.

- Akbari, Z. (2015). Current challenges in teaching/learning English for EFL learners: The case of junior high school and high school. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 199, 394–23. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.524

- Althuhami, A. D. A. R. (2011). Evaluating EFL intermediate teachers’ performance in the light of quality standards in Saudi Arabia. (Master’s thesis, Taif University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia).

- Atai, M. R., Babaii, E., & Mousavi, M. (2016). Exploring standards and developing a measure for evaluating Iranian EFL teachers’ professional competence in the private sector. Iranian Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 5(2),30–5.

- Baghazadeh Naini, M., & Dastjerdi, H. (2014). Teaching methods and educational atmosphere in Isfahan English language institutes: Do teachers and learning facilities make a difference? Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(23), 1198–1205.

- Ballou, D., & Podgursky, M. J. (1997). Teacher pay and teacher quality. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research (pp.1–185).

- Barrett, A. M., Duggan, R. C., Lowe, J., Nikel, J., & Ukpo, E. (2006). The concept of quality in education: A review of the international literature on the concept of quality in education. EdQual RPC.

- Being-fang, G. E. (2000). Quality-oriented education: A TEFL context perspective. Subject Education, 3(007).

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. London: Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Estaji, M. (2010). Assessment rubrics as learning tool to enhance students’ academic performance. TELLSI 10 Conference Proceedings, 521.

- Fredriksson, U. (2004). Quality education: The key role of teachers. Education International Working Papers, 14.

- Gholami, J., Sarkhosh, M., & Abdi, H. (2016). An exploration of teaching practices of private, public, and public-private EFL teachers in Iran. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 18(1), 16–33. doi:10.1515/jtes-2016-0002

- Grisay, A., & Mahlck, L. (1991). The quality of education in developing countries: A Preview of Some Research Studies and Policy Documents. Paris: IIEP.

- Guidelines for Quality in Language Teaching. (2009–2011). Quality in language teaching for adults grundtving learning partnership (pp. 1–40).

- Iranian National standards-Structure and Drafting. (2014). Iranian National Standardization Organization.

- Jain, C., & Prasad, N. (2018). Quality of secondary education in India. Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Kanji, G. K., Malek, A., & Tambi, B. A. (1999). Total quality management in UK higher education institutions. Total Quality Management, 10(1), 129–153.

- Kanji, G. K., Malek, A., & Tambi, B. A. (1999). Total quality management in UK higher education institutions. Total Quality Management, 10(1), 129–153.

- Krejcie, R., & Morgan, D. (1970). Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 30(3), 607–610. doi:10.1177/001316447003000308

- Kuhlman, N., & Knezevic, B. (2013). The TESOL guidelines for developing EFL standards. TESOL International Association.

- Language Learning Services outside Formal Education—Requirements. (2015). Iranian National Standardization Organization.

- Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. (2018, November). Retrieved from https://www.farhang.gov.ir

- Ministry of Education Website. (2018, November). Retrieved from https://www.medu.ir

- Ministry of science, Research and Technology. (2018, November). Retrieved from http://www.msrt.ir

- Motallebzadeh, K., & Kafi, Z. (2015). Place-based education: Does it improve 21st century skills? International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 4, 1.

- Nezakat- Alhossaini, M., & Ketabi, S. (2013). Teacher training system and EFL classes in Iran. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 526–536. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.090

- Pallant, J. (2007). SPSS survival manual. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Podgursky, M. J., & Springer, M. G. (2006). Teacher performance pay: A review. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 26(4), 909–949.

- Razmjoo, S. A., & Riazi, A. M. (2006). Do high schools or private institutes practice communicative language teaching? A case study of Shiraz teachers. The Reading Matrix, 6(3), 340–363.

- Rossman, B. G., & Rallis, S. F. (1998). Learning in the field: An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage.

- Sadeghi, K., & Richards, J. C. (2015). The idea of English in Iran: An example from Urmia. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 37(4),419–434.

- Sağlam, G., & Salı, P. (2013). The essentials of the foreign language learning environment: Through the eyes of the pre-service EFL teachers. Procedia-Social And Behavioral, 93, 1121–1125. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.09.342

- Sallis, E. (2002). Total quality management in education. Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Salvucci, S., Walter, E., Conley, V., Fink, S., & Saba, S. (1997). Measurement error studies at the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES 97–464). U.S. Department of Education, National center for Education Statistics.

- Satterlee, A. G. (2010). Online faculty satisfaction and quality enhancement initiatives. IABR & ITLC Conference Proceedings .Dublin, Ireland

- Schoonenboom, J., & Johnson, R. B. (2017). How to construct a mixed method research design, 69(2), Springer.

- Shishavan, H., & Sadeghi, K. (2009). Characteristics of an effective English language teacher as perceived by Iranian teachers and learners of English. English Language Teaching, 2(4). doi:10.5539/elt.v2n4p130

- Spada, N., Barkaoui, K., Peters, C., So, M., & Valeo, A. (2009). Developing a questionnaire to investigate second language learners’ preferences for two types of form-focused instruction. System, 37, 70–81. doi:10.1016/j.system.2008.06.002

- Stufflebeam, D. L. (2002b). The CIPP model for evaluation. In D. L. Stufflebeam, C. F. Madam, & T. Kellaghan (Eds.), Evaluation models (pp. 279–317). New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Tabatabaeei, O., & Loni, M. (2015). Problems of teaching and learning English in Lorestan Province high schools, Iran. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 47–55.

- The Dakar Framework for Action. (2000). World education forum. Understanding education quality. (2005). EFA Global Monitoring Report

- Walser, T. M. (2011). Using a standard rubric to promote high standards, fairness, student motivation, and assessment for learning. Mountain Rise, 6(3), 1–13.

- Wayne, D. (1990). Kolmogorov-Smirnov one-sample test. Applied nonparametric statistics (2nd ed.). Boston: PWS-Kent.

- Wenglinsky, H. (2000). How teaching matters: Bringing the classroom back into discussions of teacher quality.

- Yilmaz, K., & Altinkurt, Y. (2011). The views of new teachers at private teaching institutions about working conditions. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 11(2), 645–650.

- شفیعا, محمد علی. (1380). شاخص های مناسب برای ارزیابی کیفیت عملکرد در آموزش عالی ایران. موسسه پزوهش و برنامه ریزی آموزش عالی.

- کیذوری, امیرحسین. (1386). معرفي برخي شاخصهاي كيفيت نظام دانشگاهي براي استفاده در بودجه ريزي دانشگاهي. فصلنامه پژوهش و برنامه ريزي در آموز ش عالي،,45.

- عطایی, محمود رضا, بابایی, عصمت, و موسوی, ملیحه. (1393). ارزشیابی صلاحیت حرفه ای مدرسان زبان انگلیسی سطح بزرگسال در بخش خصو صی آموزش زبان ایران. پزوهش های زبانشناختی در زبان های خارجی, 4(2), 243–266.