Abstract

The present study was aimed at investigating the relationships among perfectionism, reflection and burnout among Iranian EFL teachers. To this end, 156 Iranian EFL teachers completed a battery of questionnaires, namely Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale, Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey and English Language Teaching Reflection Inventory. Data were analyzed through Pearson correlation and multiple regression followed by path analysis. Our results showed that teachers’ reflection was a significant correlate of their burnout with less reflective teachers experiencing more burnout. However, the findings were indicative of no significant relationship between the three aspects of perfectionism and teacher burnout. Further analysis of two path models which were conceptualized and proposed based on our primary findings, revealed a more detailed picture of the multilateral associations among perfectionism, reflection and burnout. Our first model assumed that teachers’ reflection can function as a mediator in the relationship between self-oriented perfectionism and burnout. Our second model presupposed that perfectionism components affect reflection positively, and reflection has in turn a negative effect on teachers’ burnout. Results from path analysis showed that both of the proposed models enjoyed acceptable goodness of fit.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Teaching is a stressful job and teachers have to constantly grapple with its challenges. This may make them so tired, helpless and demotivated that they may decide to leave their profession. Identification of causes of teacher burnout can therefore help policy makers come up with better solutions to prevent it. In this study, we found that perfectionism, especially its socially prescribed dimension, can induce burnout. Reflection, on the other hand, was found to not only mitigate the burnout-inducing effects of perfectionism but also prevent burnout in its own right. These findings could be of value to teacher education programs in helping teachers overcome burnout.

1. Introduction

The past three decades have witnessed a gradual shift from a product-oriented view of teacher education to a process based and dialogic perspective. Teachers who were assumed to be passive recipients of fixed instructional packages which were supposed to work in all contexts were gradually encouraged to take the initiative and play active roles in the life of the classroom by making context-wise decisions, learning from their past teaching experiences and continually revising and improving their practice (Borg, Citation2003). Almost parallel with this shift of perspective in general teacher education, post-method discourse in language teaching gained momentum (Kumaravadivelu, Citation1994). Arguing against the concept of method as pedagogically unwise and socio-politically indifferent, Kumaravadivelu (Citation1994) called for an L2 pedagogy which respects particularities of teaching contexts, provides teachers and learners with social and educational possibilities while taking into account the probable barriers to practicalities of practice. Although intriguing at the theoretical level, the emphasis of these recent trends in education and English language teaching on teachers as independent, dedicated, curious and even omniscient actors in the context of the classroom has not been without criticism (Akbari, Citation2008). Expecting teachers, who are usually overworked and underpaid, to make wise decisions on a regular basis may not only be rather unwise but can make them exhausted and distressed to the extent of leaving their professions and seeking jobs in less stressful non-teaching contexts (Hughes, Citation2001). Reflection is widely suggested as a solution to prevent teachers’ distress, help them make better pedagogical decisions and embolden them to overcome pedagogical challenges and improve their practice. Notwithstanding the theoretical arguments in praise of reflection, not enough empirical studies have however explored its effectiveness (Moradkhani & Shirazizadeh, Citation2017). In this study, we set out to examine if reflection, the theoretically complimented solution to some of the challenges and confusions of teachers, is preventive of teachers’ feeling of occupational exhaustion, technically termed burnout. In our exploration of this issue, given that burnout has been attributed in the literature of educational psychology to unrealistic expectations of one’s self and others (Stoeber & Rennert, Citation2008), we also examine the role of perfectionism as it relates to both teacher reflection and teacher burnout.

2. Literature review

2.1. Perfectionism

From a historical standpoint, perfectionists were mainly characterized as those who set for themselves idealistically high and rather unattainable goals which make them constantly dissatisfied with their perceived failures while disregarding their accomplishments. (Antony & Swinson, Citation1998). As Burns (Citation1980) noted perfectionist individuals cannot stand mistakes inasmuch as only a perceived minor error would be considered as a downright failure even at the expense of questioning their self-worth. Within such a conceptualization, perfectionism has been associated with or conducive to many different psychological problems such as depression (Klibert et al., Citation2014), low self-efficacy (Stoeber, Hutchfield, & Wood, Citation2008), low self-esteem (Ashby & Rice, Citation2002), and burnout (Stoeber & Rennert, Citation2008). The early monodimensional, mostly negative and asocial view of perfectionism was later revised to accommodate more inclusive models of this concept (Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, & Ashby, Citation2001). In one of such well-known later conceptualizations, perfectionism was categorized into self-oriented perfectionism (SOP), other-oriented perfectionism (OOP), and socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP). As an intrapersonal dimension, SOP means imposing idealistic high self-standards for oneself and striving to achieve them impeccably; if these attitudes direct toward others rather than the self so as to insist that things be done flawlessly by others, it is characterized as OOP. SPP, the third dimension, involves developing high standards due to the high expectations that are prescribed by significant others (Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991).

Perfectionism as a multidimensional attribute has been widely investigated within the literature of educational psychology. Many scholars have worked on student samples. For example, Klibert et al. (Citation2014) reported that although all the three components of Hewitt and Flett’s model of perfectionism were positively associated with depression and anxiety among college students, it was only SPP which was significantly related to lower resilience. Miquelon, Vallerand, Grouzet, and Cardinal (Citation2005) also found that SOP leads to self-determined academic motivation, whereas SPP is conducive to non-self-determined academic motivation. SOP has also been found to be positively related to intrinsic motivation while SPP was positively related to extrinsic motivation (Miquelon et al., Citation2005) and negatively correlated with intrinsic motivation (Mills & Blankstein, Citation2000). Seo (Citation2008) reported that college students with high SOP procrastinated less than others and that self-efficacy fully mediated the relationship between SOP and academic procrastination. Investigating the relationship between perfectionism and academic achievement, Witcher, Alexander, Onwuegbuzie, Collins, and Witcher (Citation2007) found that students with high levels of SOP and OOP had the highest achievement on the midterm and final exams of a graduate course. SPP was however negatively correlated with achievement. There are also studies on the role of perfectionism within the context of foreign language learning. In one of the most widely cited researches in this area, Gregersen and Horwitz (Citation2002) showed that highly anxious learners held more perfectionistic views of language learning compared to less anxious ones. In another study by Ghafar Samar and Shirazizadeh (Citation2011), SPP was reported to be negatively associated with foreign language reading anxiety and achievement. Similarly, SOP was negatively correlated with foreign language writing anxiety and achievement (Shirazizadeh, Moradkhani, & Karimpour, Citation2017). Pishghadam and Akhoondpoor (Citation2011) also reported that perfectionism was negatively correlated with speaking, listening, reading and writing in English as a foreign language.

Compared to the studies conducted on students, research on perfectionism within teacher samples is scarce. Flett, Hewitt, and Hallett (Citation1995) investigated perfectionism as it relates to teachers’ stress. They found that SPP was associated with a host of teacher physical and emotional stress-related reactions in teachers. Also, teachers with higher SPP reported more frequent and intense professional distress and lower levels of job satisfaction. Perfectionism has also been found to be related and conducive to burnout among teachers (Stoeber & Rennert, Citation2008). For example in a recent study on English teachers, Mahmoodi-Shahrebabaki (Citation2017) reported that perfectionism was correlated with burnout especially its depersonalization aspect. He also showed that anxiety is a significant mediator in the relationship between perfectionism and teacher burnout.

2.2. Reflection

The available literature on reflection makes it difficult to offer a clear definition of the concept as it encompasses a variety of interpretations. In its simplest form, refection “means thinking about something” while for some “it is a well-defined and crafted practice that carries very specific meaning and associated action” (Loughran, Citation2002, p. 33). Dewey (Citation1933) defined it as the “‘active, persistent and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends’” (p. 9). In simple terms, reflective teachers are therefore those who take their career seriously, make informed pedagogical decisions, look at teaching as a never-ending learning process, learn from their mistakes, and regularly improve their teaching in light of the requirements of the teaching context. More practically, reflective practice can be realized in keeping teaching journals, writing and revising lesson plans, doing classroom observation, making critical friendship with colleagues and holding group discussions, and all activities one can do to evaluate one’s practice and learn more about teaching (Farrell, Citation2008).

Although the concept of reflection has been around for many decades in the literature of teacher education, empirical studies on if and how it influences, and is influenced by, the various dimensions of teachers and teaching are relatively recent. This line of inquiry is even narrower and younger within English language teaching with the majority of such studies published in the past decade. A review of the findings of this stream of research shows that reflection is associated with several positive qualities in teaching. For instance, Abednia, Hovassapian, Teimournezhad, and Ghanbari (Citation2013) explored the perceptions of six EFL teacher as to the benefits of journal writing as a form of critical reflection. Writing journals were found to contribute to teachers’ self-awareness, understanding of teaching issues, reasoning skills, and improved teachers’ dialog with the teacher educator. Group reflection was also reported to help novice English teachers gain a better understanding of the challenges they may encounter in the early years of their teaching and become better prepared to overcome them (Farrell, Citation2016). Motallebzadeh, Ahmadi, and Hosseinnia (Citation2018) reported that reflection is positively linked to teaching effectiveness among EFL teachers. Kheirzadeh and Sistani (Citation2018) also found that EFL teachers’ reflectivity is positively linked to their students’ achievements. Refection has also been reported to be negatively correlated with burnout (Mahmoodi & Ghaslani, Citation2014; Shirazizadeh & Moradkhani, Citation2018) and positively linked to self-efficacy (Moradkhani, Raygan, & Moein, Citation2017).

2.3. Burnout

Although celebrated as self-satisfying and rewarding, teaching is a stressful job compared to many other professions (Johnson et al., Citation2005). Chronic occupational stress leads to burnout which is defined as “erosion of engagement that what started out as important, meaningful, and challenging work becomes unpleasant, unfulfilling, and meaningless” (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, Citation2001, p. 416). Maslach and Jackson (Citation1981) conceptualized burnout as composed of emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DEP) and lack of personal accomplishment (LPA). According to Maslach et al. (Citation2001), EE as a central dimension of burnout is featured as a state of being overwhelmed and emotionally drained by job demands. DEP as an interpersonal dimension refers to detached, impersonal and uncaring feelings teachers have about their students and colleagues. LPA refers to a kind of harbouring negative attitudes toward one’s effectiveness and productivity at work. Burnout has been examined in various contexts and in relation to many individual, contextual and transactional factors (Chang, Citation2009). Work overload, student misbehaviour, introversion, neuroticism (Fernet, Guay, Senécal, & Austin, Citation2012), ineffective relationship with colleagues, improper working conditions (Betoret, Citation2006), time pressure and low self-efficacy (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, Citation2010) are some of the variables associated with teacher burnout.

Teacher burnout has also been widely investigated within the context of English language teaching as such a context may induce not only the stress of teaching but also the pressures associated with mastery over content which is usually not teachers’ first language (Ghanizadeh & Jahedizadeh, Citation2016). Both contextual and personality variables were reported to induce burnout among EFL teachers (Cano-García, Padilla-Muñoz, & Carrasco-Ortiz, Citation2005). Burnout among EFL teachers was also reported to be inversely associated with self-regulatory strategies (Ghanizadeh & Ghonsooly, Citation2014), emotional labor strategies and emotion regulation (Ghanizadeh & Royaei, Citation2015). In a study on Iranian EFL teachers, Khajavy, Ghonsooly, and Fatemi (Citation2017) explored the relationship between burnout and a host of affective motivational factors. They reported that while enjoyment, pride, and the three types of motivation namely altruistic, intrinsic and extrinsic were negatively correlated with all three dimensions of burnout, anxiety, anger, shame and boredom were positively linked to the different dimensions of this syndrome.

The review of literature suggests that perfectionism may be conducive to various maladaptive behaviours like burnout. Reflection, on the other hand, has been reported, in the majority of studies, as conducive to positive attributes in teachers. It can therefore be hypothesized that reflection may be able to act as a buffer against the possible burnout inducing effects of perfectionism. However, there is, to the best of our knowledge, no study that has examined the bivariate, multivariate and causal relationships among perfectionism, reflection and burnout. We therefore aimed at filling this lacuna by answering the following questions:

Is occupational burnout among Iranian EFL teachers related to their perfectionism and reflection?

Does the relationship among perfectionism, reflection and burnout fit into a causal model?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants and context

A total of 156 Iranian EFL teachers from both schools and language institute context participated in this study based on convenience sampling. It is worth noting that Iranian schools follow a fixed nation-wide curriculum which allocate only one and a half hour to English per week. Teacher recruitment is usually based on an admission test which includes a range of subjects along with English. Private English institutes, on the other hand, are decentralized and more liberal in their curriculum and offer at least four and a half hours of instruction per week. Institute teachers are most often recruited just based on their language proficiency. School teachers are government employees with high job security while institute teachers are employed based on short-term contracts and regularly screened for quality. Of the total participants, 109 were female and 47 were male. Twenty-six held bachelor’s, 99 held master’s and 26 held PhD degrees in English-related majors; 5 held English certificate. Their teaching experience ranged from less than 2 years to more than 10 years.

3.2. Instruments and data collection

Three questionnaires were employed to gather data for this study. The Persian version (Akbari, Ghafar Samar, Kiany, & Eghtesadi, Citation2011) of Maslach Burnout Inventory-Educators Survey (Maslach, Jackson, & Schwab, Citation1996) was employed for measuring teachers’ level of burnout. This 22 self-report questionnaire measures burnout on three subscales (EE with nine items, DEP with five items, and LPA with eight items; See Appendix for sample items of the original instrument). Responses were based on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from “never” to “once a day”. Teachers’ degree of perfectionism was rated by the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale developed by Hewitt and Flett (Citation1991) which is a 45 item questionnaire rated on seven-point Likert scale (See Appendix for sample items). It measures the three dimensions of perfectionism, namely SOP, OOP and SPP each represented with 15 questions in this scale.

Teachers’ Reflectivity was measured by the English Language Teaching Reflection Inventory (Akbari, Behzadpoor, & Dadvand, Citation2010; See Appendix for sample items). It includes 29 items measuring five components. This questionnaire is a five point Likert scale ranging from “never” to “always”. Practical reflection (six items) refers to the actual practice of reflection through journal writing, lesson reports, audio and video recordings, and group discussions. Cognitive reflection (six items) is concerned with teacher’s activities for their professional growth through attending conferences or doing action research. Affective reflection (3 items) concerns teachers’ attachment to and reflection on their students’ academic progress, and emotional well-being. The metacognitive component of reflection (seven items) deals with teachers’ reflection on their own personality and beliefs, emotional make-up, and identity. Critical reflection (seven items) which is the last component measured by the inventory concerns teachers’ attention to the socio-political aspects of their teaching practice. It should be noted once again that while we used the Persian version of the burnout inventory, the original English version of the other two instruments were used, as there were no validated Persian versions available.

A total of 190 questionnaires were initially distributed both electronically and in print format of which 180 were filled and returned (94% return rate). Of the returned questionnaires, 24 were discarded as they were carelessly done or left unfinished. The remaining 156 appropriately filled questionnaires were carefully examined and teachers’ responses to each of the items were fed into SPSS for statistical analysis.

3.3. Data analysis

After feeding the data into SPSS 21, we used Cronbach’s alpha to evaluate the reliability of answers to different sections of the questionnaires. Descriptive statistics for each of the variables and bivariate correlation between each pair were calculated to provide an overall picture of the data. To answer the first research question, we used correlation followed by multiple regression while the second research question was answered through path analysis using AMOS 22.

4. Results

Table presents the reliability indices and descriptive statistics of the overall scores and the subscales of the three variables examined in this study. To explore the relationship between teacher’s degree of burnout and their degree of perfectionism and reflection, Pearson product-moment correlation was employed. As can be seen, there was a significant negative correlation between teachers’ burnout and their reflection scores (r = −.27). More specifically, from among the three components of burnout, EE and LPA showed a negative correlation with the five dimensions of reflection. Save for the correlations between EE and cognitive reflection (r = −.15), EE and critical reflection (r = −.14) and LPA and critical reflection (r = −.03), all other correlations were statistically significant. Data showed that perfectionism components are not significantly correlated with teacher burnout and its components. Teachers’ total reflection scores were significantly correlated only with SOP (r = .19). Its correlation with OOP (r = .14) and SPP (r = .07) was positive but statistically non-significant.

Table 1. Correlation matrix, reliability index and descriptive statistics of the measured variables

The first research question of the study concerned the relationship between burnout and the two variables of perfectionism and reflection. As noted earlier, all the correlations between dimensions of perfectionism and burnout were not only small but also non-significant (see Table ) suggesting that in our sample, teachers’ perfectionistic tendencies are not linked to their occupational burnout. However, to further investigate this link and verify the absence of such a relationship, we analysed the data using multiple regression. The results of this further analysis also indicated that perfectionism components are not related to teachers’ burnout and hence none of the components of perfectionism can be a significant predictor of burnout.

In the next stage of our analysis, we focused on the relationship between reflection and burnout. Initial exploration of the data through correlation had demonstrated that reflection is inversely related to burnout suggesting that reflective teachers are at lower risks of occupational burnout. To further examine this relationship and see which dimensions of reflection better predict teacher burnout, we used multiple regression. The findings of the regression model showed that metacognitive and practical dimensions of reflections were the two significant predictors of teachers’ burnout. Metacognitive reflection accounted for 9% of the variance in total burnout scores. The addition of practical dimension increased this shared variance to about 11%. We then entered each of the burnout components to the regression model as dependent variables separately to examine if and how much of their variance can be accounted for by the different aspects of reflection. Of the five components of reflection, only practical reflection was found to be a significant predictor of EE (R2 = 0.05). None of reflection components, however, could predict DEP as a dependent variable indicating that their contributions to the prediction of DEP were statistically non-significant. In the case of LPA, metacognitive reflection was the only best predictor in the regression model (R2 = 0.13). Table summarizes the regression models.

Table 2. Summary of regression models for the second research question

The second research question of this study deals with evaluating a multivariate model of the relationships among the variables of the study. In other words, we set out to examine if teacher burnout is caused, in a mediated and unmediated manner, by teachers’ perfectionistic tendencies and reflectivity. In light of the findings of the first research question, we developed two possible models of the relationships among the variables.

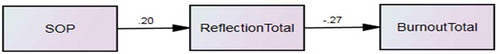

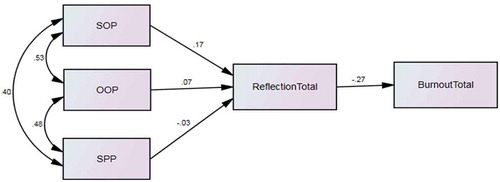

The first model assumed that SOP prevents burnout through the mediation of reflection (see Figure ). The second model, which is an extended version of the first model, assumes that all three types of perfectionism are conducive to, or maybe preventive of, burnout through the mediation of reflection (see Figure ).

Figure 2. A mediated model of the links between the three types of perfectionism, reflection and burnout.

Both models were evaluated through path analysis. A number of fit indices were checked to see if the data fits the proposed models. The findings revealed that both models are acceptably fit (See Table ). More specifically, analysis of the first model confirmed that SOP is conducive to reflection which in turn can prevent burnout.

Table 3. Fit indices of the models

Findings of the evaluation of the second model also showed that SOP and OOP are conducive to reflection which protects teachers against burnout; the effect of SPP on burnout is, however, quite the opposite. As implied from the path indices in the second model, SPP reduces reflectivity and by so doing can be conducive, albeit minimally, to teacher burnout.

5. Discussion

This study examined how perfectionism and reflection are related to burnout among Iranian EFL teachers. Possible links between perfectionism and reflection were also examined. The findings showed that reflection is inversely linked to burnout suggesting that reflective teachers are at lower risks of burnout. Similar to this finding, Shirazizadeh and Moradkhani (Citation2018) also reported that although EFL teachers encountered several demotivating impediments to reflection, reflective teachers are more likely to survive the daily stressors of their profession. The inverse relationship between reflection and burnout may be discussed in light of several positive attributes such as professional identity (Olsen, Citation2012) and self-efficacy (Moradkhani et al., Citation2017). Reflection requires the devotion of time and resources by the teacher to identify the problems and come up with solutions. This is almost impossible without the teacher being dedicated and emotionally attached to his job. Teachers’ professional identity is therefore highly related to, and in some aspects synonymous with reflection (Olsen, Citation2012). As defined by Beijaard, Meijer, and Verloop (Citation2004), teacher identity is developed through interpretation and reinterpretation of who the teacher is and who he desires to become. It can therefore be implied that identity formation is also a reflective process (and reflection an identity developing process) which makes teachers more emotionally attached to their roles and influences their worldviews (Holland & Lachicotte, Citation2007). It is then no surprise that a reflective teacher identifies more with his job, is more emotionally attached to his role, views the challenges of teaching as foods for thought and motivators of learning and improvement, and hence is less vulnerable to stressors and less prone to burnout. High levels of reflection may protect teachers against burnout not only through deeper identity roots and stronger emotional attachment but also through boosting their self-efficacy and strengthening them against possible causes of burnout (El Helou, Nabhani, & Bahous, Citation2016; Moradkhani et al., Citation2017).

The findings of this study also revealed that although perfectionism is not a direct predictor or cause of teacher burnout, it influences burnout through the mediations of reflection. Our causal model further showed that SOP and OOP could be conducive to reflection while SPP may minimally hinder it; the preventive effects of SOP and OOP and the causal effect of SPP on burnout were thus indirect and through reflection. The positive effects of SOP and OOP on reflection can be justified on the ground that teachers with higher levels of these two types of perfectionism may value themselves (self) and their students (significant others) and show more enthusiasm in achieving their professional goals by helping their students overcome the challenges of learning. This higher attachment to their teacher role and their students would necessarily involve them in a wide range of metacognitive and affective reflective activities (Akbari et al., Citation2010). SPP on the other hand is the dimension of perfectionism which is widely reported as a cause of anxiety and failure (Klibert et al., Citation2014). This may eventually distance teachers from their job, colleagues and teaching context, demotivate them to learn and solve problems and make them indifferent and less reflective in the long run. It can therefore be hypothesized that higher levels of SPP may make teachers more anxious, uninterested and helpless and less reflective, hence more vulnerable to burnout and leaving their profession.

In conclusion, the findings of this study provided empirical support for the usefulness of reflection as a versatile tool that helps teachers in the various aspects their professional development. We found that reflection could act as a protective shield against burnout and thus deserves promotion in EFL teacher education programs. Teachers who are obsessed with others’ expectations of them (high in SPP) were also found to be comparatively less reflective and more likely to burnout. These findings call for more attention to helping teachers, especially the early career ones, boost their self-efficacy, value their own thoughts and practice and handle more confidently the feedbacks they receive from others. Teacher education programs should therefore invest more on providing readily accessible and personalized support systems to provide teachers with advice and protect them against striving too hard to meet too unrealistic demands, losing their interest in reflection, devaluing their professional identity, and eventually succumbing to burnout.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohsen Shirazizadeh

Mohsen Shirazizadeh is an assistant professor of applied linguistics at Alzahra University, Tehran, Iran. His research interest includes L2 teacher education and L2 writing.

Mahboubeh Karimpour

Mahboubeh Karimpour holds a master’s degree in applied linguistics from Alzahra University, Tehran Iran. Her research interests include L2 teacher education and language assessment.

References

- Abednia, A., Hovassapian, A., Teimournezhad, S., & Ghanbari, N. (2013). Reflective journal writing: Exploring in-service EFL teachers’ perceptions. System, 41(3), 503–13. doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.05.003

- Akbari, R. (2008). Postmethod discourse and practice. TESOL Quarterly, 42(4), 641–652. doi:10.1002/tesq.2008.42.issue-4

- Akbari, R., Behzadpoor, F., & Dadvand, B. (2010). Development of English language teaching reflection inventory. System, 38(2), 211–227. doi:10.1016/j.system.2010.03.003

- Akbari, R., Ghafar Samar, R., Kiany, G. R., & Eghtesadi, A. R. (2011). Factorial validity and psychometric properties of Maslach burnout inventory–The Persian version. Knowledge Health, 6(3), 1–8.

- Antony, M. M., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). When perfect isn’t good enough. Strategies for coping with perfectionism. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

- Ashby, J. S., & Rice, K. G. (2002). Perfectionism, dysfunctional attitudes, and self‐esteem: A structural equations analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80(2), 197–203. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2002.tb00183.x

- Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(2), 107–128. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

- Betoret, F. D. (2006). Stressors, self‐efficacy, coping resources, and burnout among secondary school teachers in Spain. Educational Psychology, 26(4), 519–539. doi:10.1080/01443410500342492

- Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: A review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching, 36(2), 81–109. doi:10.1017/S0261444803001903

- Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York, NY: Avon Books.

- Cano-García, F. J., Padilla-Muñoz, E. M., & Carrasco-Ortiz, M. Á. (2005). Personality and contextual variables in teacher burnout. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(4), 929–940. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.06.018

- Chang, M.-L. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: Examining the emotional work of teachers. Educational Psychology Review, 21(3), 193–218. doi:10.1007/s10648-009-9106-y

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Boston: Heath, & Co.

- El Helou, M., Nabhani, M., & Bahous, R. (2016). Teachers’ views on causes leading to their burnout. School Leadership & Management, 36(5), 551–567. doi:10.1080/13632434.2016.1247051

- Farrell, T. S. (2008). Critical reflection in a TESL course: Mapping conceptual change. ELT Journal, 63(3), 221–229. doi:10.1093/elt/ccn058

- Farrell, T. S. (2016). Surviving the transition shock in the first year of teaching through reflective practice. System, 61, 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.system.2016.07.005

- Fernet, C., Guay, F., Senécal, C., & Austin, S. (2012). Predicting intraindividual changes in teacher burnout: The role of perceived school environment and motivational factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(4), 514–525. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.013

- Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Hallett, C. J. (1995). Perfectionism and job stress in teachers. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 11(1), 32–42. doi:10.1177/082957359501100105

- Ghafar Samar, R., & Shirazizadeh, M. (2011). On the relationship between perfectionism, reading anxiety and reading achievement: A study on the psychology of language learning. Language Related Research, 2(1), 1–19.

- Ghanizadeh, A., & Ghonsooly, B. (2014). A tripartite model of EFL teacher attributions, burnout, and self-regulation: Toward the prospects of effective teaching. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 13(2), 145–166. doi:10.1007/s10671-013-9155-3

- Ghanizadeh, A., & Jahedizadeh, S. (2016). EFL teachers’ teaching style, creativity, and burnout: A path analysis approach. Cogent Education, 3(1), 1151997. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2016.1151997

- Ghanizadeh, A., & Royaei, N. (2015). Emotional facet of language teaching: Emotion regulation and emotional labor strategies as predictors of teacher burnout. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 10(2), 139–150. doi:10.1080/22040552.2015.1113847

- Gregersen, T., & Horwitz, E. K. (2002). Language learning and perfectionism: Anxious and non‐anxious language learners’ reactions to their own oral performance. The Modern Language Journal, 86(4), 562–570. doi:10.1111/modl.2002.86.issue-4

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.60.3.456

- Holland, D., & Lachicotte, W. (2007). Vygotsky, mead, and the new sociocultural studies of identity. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, & J. V. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Vygotsky (pp. 101–135). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Hughes, R. E. (2001). Deciding to leave but staying: Teacher burnout, precursors and turnover. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(2), 288–298. doi:10.1080/713769610

- Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S., Donald, I., Taylor, P., & Millet, C. (2005). The experience of work-related stress across occupations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(2), 178–187. doi:10.1108/02683940510579803

- Khajavy, G. H., Ghonsooly, B., & Fatemi, A. H. (2017). Testing a burnout model based on affective-motivational factors among EFL teachers. Current Psychology, 36(2), 339–349. doi:10.1007/s12144-016-9423-5

- Kheirzadeh, S., & Sistani, N. (2018). The effect of reflective teaching on Iranian EFL students’ achievement: The case of teaching experience and level of education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(2), 143–156. doi:10.14221/ajte

- Klibert, J., Lamis, D. A., Collins, W., Smalley, K. B., Warren, J. C., Yancey, C. T., & Winterowd, C. (2014). Resilience mediates the relations between perfectionism and college student distress. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(1), 75–82. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00132.x

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (1994). The postmethod condition: (E) merging strategies for second/foreign language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 28(1), 27–48. doi:10.2307/3587197

- Loughran, J. J. (2002). Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 33–43. doi:10.1177/0022487102053001004

- Mahmoodi, M. H., & Ghaslani, R. (2014). Relationship among Iranian EFL teachers’ emotional intelligence, reflectivity and burnout. Iranian Journal of Applied Language Studies, 6(1), 89–116.

- Mahmoodi-Shahrebabaki, M. (2017). The effect of perfectionism on burnout among English language teachers: The mediating role of anxiety. Teachers and Teaching, 23(1), 91–105. doi:10.1080/13540602.2016.1203776

- Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1379

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Schwab, R. L. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory-educators survey (MBI-ES). MBI Manual, 3, 27–32.

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

- Mills, J. S., & Blankstein, K. R. (2000). Perfectionism, intrinsic vs extrinsic motivation, and motivated strategies for learning: A multidimensional analysis of university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(6), 1191–1204. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00003-9

- Miquelon, P., Vallerand, R. J., Grouzet, F. M., & Cardinal, G. (2005). Perfectionism, academic motivation, and psychological adjustment: An integrative model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(7), 913–924. doi:10.1177/0146167204272298

- Moradkhani, S., Raygan, A., & Moein, M. S. (2017). Iranian EFL teachers’ reflective practices and self-efficacy: Exploring possible relationships. System, 65, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.system.2016.12.011

- Moradkhani, S., & Shirazizadeh, M. (2017). Context-based variations in EFL teachers’ reflection: The case of public schools versus private institutes in Iran. Reflective Practice, 18(2), 206–218. doi:10.1080/14623943.2016.1267002

- Motallebzadeh, K., Ahmadi, F., & Hosseinnia, M. (2018). The relationship between EFL teachers’ reflective practices and their teaching effectiveness: A structural equation modeling approach. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1424682. doi:10.1080/23311908.2018.1424682

- Olsen, B. (2012). Identity theory, teacher education, and diversity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication. doi:10.4135/9781452218533

- Pishghadam, R., & Akhoondpoor, F. (2011). Learner perfectionism and its role in foreign. language learning success, academic achievement, and learner anxiety. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2(2), 432–440. doi:10.4304/jltr.2.2.432-440

- Seo, E. H. (2008). Self-efficacy as a mediator in the relationship between self-oriented perfectionism and academic procrastination. Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal, 36(6), 753–764. doi:10.2224/sbp.2008.36.6.753

- Shirazizadeh, M., & Moradkhani, S. (2018). Minimizing burnout through reflection: The rocky road ahead of EFL teachers. Teaching English Language, 12(1), 135–154.

- Shirazizadeh, M., Moradkhani, S., & Karimpour, M. (2017). Anxiety and performance in second language writing: Does perfectionism play a role? Foreign Language Research Journal, 7(1), 153–177.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001

- Slaney, R. B., Rice, K. G., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J. S. (2001). The revised almost perfect scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counselling and Development, 34(3), 130. doi:10.1080/07481756.2002.12069030

- Stoeber, J., Hutchfield, J., & Wood, K. V. (2008). Perfectionism, self-efficacy, and aspiration level: Differential effects of perfectionistic striving and self-criticism after success and failure. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(4), 323–327. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.04.021

- Stoeber, J., & Rennert, D. (2008). Perfectionism in school teachers: Relations with stress appraisals, coping styles, and burnout. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 21(1), 37–53. doi:10.1080/10615800701742461

- Witcher, L. A., Alexander, E. S., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Collins, K. M., & Witcher, A. E. (2007). The relationship between psychology students’ levels of perfectionism and achievement in a graduate-level research methodology course. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(6), 1396–1405. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.016

Appendix

Sample items from the instruments

Perfectionism

When I am working on something, I cannot relax until it is perfect.

Everything that others do must be of top-notch quality.

I find it difficult to meet others’ expectations of me.

Reflection

I talk about my classroom experiences with my colleagues and seek their advice/feedback.

I read books/articles related to effective teaching to improve my classroom performance.

I talk to my students to learn about their learning styles and preferences.

As a teacher, I think about my teaching philosophy and the way it is affecting my teaching.

I think about instances of social injustice in my own surroundings and try to discuss them in my classes.

Burnout (We used the Persian translation of the original instrument but original English items are included below)

I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job.

I worry that this job is hardening me emotionally.

I have accomplished many worthwhile things in this job (reverse item).