Abstract

Concept development workshops were held at various universities around Cape Town, South Africa since 2017. The aim of the workshops was to develop new concepts using an art-making process. The student protests in South Africa in 2015 and 2016 opened up pertinent social issues, but left many universities in a stagnated place where lecturers and students are too afraid to converse and unable to think creatively about ways forward. Issues of specifically social transformation and decolonisation came to the fore during the student protests, but because of the sensitivity of the topics, people were unwilling to participate or engage. The concept development workshops served as an experimental space where lecturers and students engaged in serious conversations, but in a playful manner. The workshops opened up spaces for bodily and cognitive engagements and became a way to be/think/act differently, which opened up new possibilities to move forward. This article will take the reader through the same concept development process as though the reader is part of the workshop. The reader can then participate and also learn about what other participants did in previous workshops.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article will take the reader through a concept development process as though the reader is part of a workshop. The workshop serves as an experimental space where participants engage in serious topics, but in a playful manner. The reader can participate in the workshop and also learn about what other participants did in previous workshops. The workshop follows a process of exploring, playing around with terms, adding something and relating it to something else (Deleuze, Citation1995, p. 139). The workshop has the potential to open up spaces for bodily and cognitive engagements and become a way to be/think/act differently in relation to topics such as social transformation and decolonisation.

1. Introduction

The need for alternative ways of engaging with concepts such as social transformation and decolonisation resulted from students and lecturers at various universities around Cape Town becoming stagnant and afraid to converse spontaneously and unable to think about ways forward. This article describes the process of concept development that helped students and lecturers to think differently about social issues in their own context. In this article, readers are also invited to go through this concept development process themselves. So, please sit down in a comfortable space with a large piece of paper and a variety of artmaking pens with which to write or draw. We are following a process of exploring, playing around with terms, adding something and relating it to something else (Deleuze, Citation1995, p. 139).

2. The workshop: rationale

We start with thinking about what concepts are, how they develop and what they are used for. Many countries in the Global South often refer to concepts that are developed in the Global North and it is important to intra-act with them to use them to diffract one through the other and to reconfigure them to think about our own context. However, it might become necessary to also develop our own indigenous concepts in Africa and the Global South so that they are put in conversation with one another. This workshop aims to, through an artmaking process, encourage the development of concepts that might shift or influence our being/thoughts/actions and ultimately our research endeavours.

Jackson and Mazzei’s book, Thinking with theory in qualitative research (Citation2012), stresses the need for qualitative researchers to use interpretive theories to guide their studies rather than using a rigid methodology where one assumes that data can speak for themselves and themes just emerge from data (cited in Taguchi & St. Pierre, Citation2017, p. 4). Taguchi and St. Pierre (Citation2017, p. 4) argue for “thinking without method” that opens up space to invent new concepts and to allow for entanglements with a variety of non-human forces. Manning (Citation2014) warns against putting the conditions or terms of research before exploring and experimentation, because it will produce more of the same.

The creation of concepts open up new avenues to understand issues from more perspectives in our own context. St. Pierre (Citation2015) argues that in post-qualitative (or new empirical and new materialist) research, the methodology should not dominate the research. She believes in experimentation; “putting the concepts and theories of experimental ontology to work”—“it is in the experimental moment of not knowing what to do next … that [we] will push toward the new and different in our work and lives” (St. Pierre, Citation2015, p. 92). Rajchman (Citation2008, cited in St. Pierre, Citation2015, p. 84) argues that coming up with new concepts is a “pragmatic experimental matter, something we must actually do for which there precedes no determination, no model, no ‘we’, not even an ‘I’”. St. Pierre (Citation2015, p. 84) sums this up by saying there is no model (no method, no research design, no “I”) that exists ahead of experimental work that pushes toward the new and different.

Taguchi and St. Pierre (Citation2017, p. 1) wrote about their exploration of how to “do research” using postconstructionist, posthumanist and new feminist material/empirical approaches that do not “begin with the cogito of preexisting, formalized, systematized, instrumental empirical social science research methodologies”. They argue that concepts could be used as method; a “reconceptualized way of doing educational inquiry: a way where concepts—acts of thought—are practices that reorient thinking, undo the theory/practice binary, and open inquiry to new possibilities” (Taguchi & St. Pierre, Citation2017, p. 1).

We continue with an engagement of what concepts are and how they develop. The creation of concepts has a long history, and concepts migrate and are reappropriated over time. Concepts originate from what Deleuze called the “thought flow” (Smith, Citation2014, p. 183), which is the continuous flow of thought in the universe. We are not the sole authors of our thinking, but concepts are extracted from the thought flow and rearranged in new combinations to create new meaning. Some examples of concepts are Deleuze and Guattari’s “rhizome” or Braidotti’s “nomad”. Jackson and Mazzei (Citation2012) borrowed the concept “plugging in” from Deleuze and Guattari and further developed it. Many of Deleuze and Guattari’s concepts originated from the work of Spinoza. Concepts can have layered and multiple meanings and can change over time and are always in a process of becoming (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1994). Deleuze (Citation1995) says that the identity of concepts lies in experimentation, in their intrinsic variability and mutations. Deleuze promotes a philosophy of difference and therefore his concepts should be in a process of continuous variation.

Concepts should not have a fixed identity, but have consistency; a structure that is “problematic, differential and temporal” (Smith, Citation2014, p. 179). The aim “is not to rediscover the eternal or the universal, but to find the conditions under which something new is produced (creativeness)” (Smith, Citation2014, p. 180). Deleuze (Citation1995) argues that there are two kinds of concepts that are extracted from the thought flow: universals and singularities. Deleuze refers to a straight line as a universal and a fold as a singularity. Folds vary and every fold is different, a “continuous variation” (cited in Smith, Citation2014, p. 180). According to Deleuze (Citation1995, pp. 156–157), “every moment, every individual, every event is absolutely new and singular”, but singularities are likely to become regularised and made ordinary, and it is this lessening of the singular to the ordinary that Deleuze calls the “mechanism of capture: the inevitable processes of stratification, regularization, normalization”.

We are now thinking about the creative process that will be used to develop new or often unexpected thoughts and concepts. Deleuze (Citation1995) argues that the identity of concepts lies in experimentation, in their intrinsic variability and mutations. Every moment or event is singular, but singularities are likely to become regularised and made ordinary. All actions (living our lives, researching, reading, writing, creating art) should be based on experimentation, engaging variation and allowing mutation, and working against methodisation and normalisation. Jackson and Mazzei (Citation2012, p. vii) refer to Deleuze’s zigzag concept and describe it as follows: “The zigzag is the lightning bolt spark of creation and the ‘crosscutting path from one conceptual flow to another’, a path set off by the spark of creation, unpredictable, undisciplined, anti-disciplinary, and non-static.” An art process is a process of making and unmaking, and of experimenting—where “mistakes” are welcomed and where the “mistakes” are used to unsettle the self.

Hofstadter (Citation1985) argues that making variations on a theme is the crux of creativity. When concepts enter a new domain, they start migrating and developing in unexpected ways. Hofstadter (Citation1985, p. 237) also talks about “slippability”, where concepts slip into one another, with often unpredictable results. I agree with Hofstadter (Citation1985, p. 237) that it is the variety (e.g. alternating between going slow/medium/fast, running/walking/resting, writing/playing/not writing) to which we expose ourselves that is the crux of creativity. Exploring each possibility in depth is crucial, but to keep on digging in the same hole cannot result in the new. If we continue to use the same creative art methods, or to use the same theories to plug in the same concepts as method, or use writing as research in the same way, it will also not result in the desired creativity over a longer period.

The concept development process includes aspects of “play” in tandem with seriousness, which introduces spaces for challenges and possibilities (see Henricks, Citation2006, p. 218). Hicks (Citation2004, p. 288) considers play as a “theoretical tool”. Hicks (Citation2004, p. 289) argues that play “involves self-conscious interaction between the maker, his or her physical environment, and the work of others”, but it is also about a “disciplined curiosity”. Play reminds us that we can imagine differently. Serious play is fundamental to artistic practice and it could become fundamental to all scholarly and pedagogical practice. Creative activity happens anyway in all of us; in this process we aim to make it more explicit. Andrew (Citation2011, pp. 158–159) refers to Joseph Beuys that argues:

Gradually people will learn that creativity is not just a leisure-time problem but a stratum of their own being. They will also learn that there are different strata; thinking is a structured thing, with intelligence on the lowest level, and on the highest level intuition, inspiration and imagination.

This process of actively finding relations or forcing new connections could relate to what St. Pierre (Citation2015, p. 92) calls the “physicality of theorising”. It is the creative, material, tangible and embodied process and not only the I (cognitively) alone that creates concepts. Tools, materials and person are actors in the concept-/art-making process, but with “tools and materials” being actors with agency. For example, working with paper itself can bring us to new ideas. Hickey-Moody and Page (Citation2015, p. 2) argue that the interrelation between bodies and things is vital.

In the workshop we also think of other creative processes and experimentation that other authors explored. Gannon and Lampert (Citation2017, p. 203) refer to various writers who argue that the act of writing in itself is a method of inquiry “through which we come to know, perhaps more, and certainly differently than in conventional academic prose”. The same can be said of creating art; art is a “seductive and tangled method of discovery” (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005, p. 967). Creative and analytic are not contradictory and incompatible modes (Richardson & St Pierre, Citation2005, p. 967). Ulmer (Citation2017, p. 5) describes her experimental process (based on Barad’s agential cuts, Citation2007) of physically cutting words apart that led her to richer encounters with concepts and the role of prepositions and prefixes in creating concepts. Plugging in seemingly unrelated things or cutting words apart could create conditions in which something new is produced or seen from a new perspective.

Truman and Springgay (Citation2016, p. 261) argue that walking and movement could provide a way to open up non-visual senses to defamiliarise everyday actions to “rethink and re/move what has become habitual”. Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1994) refer to a plane of immanence, which is open to “ceaseless transformations and experimentations” (Truman & Springgay, Citation2016, p. 263). The chance of making the senses more receptible might be better when bodily movement is involved. However, we can also walk new pathways without noticing the familiar, or alternatively we can open ourselves, bodily and cognitively, to be amazed by what we are able to see, feel, smell, hear and think. For instance, after reading theory and an active walking experience during the day, a half-sleep, half-conscious mode, such as before waking up in the mornings after a good night’s sleep, could be a breeding place for creating unusual relations or relationships between previously unrelated things. The unconscious mind is then randomly making unusual connections for us.

3. The workshop: the process

I will now explain the practical part of the concept development process. All concepts will be mapped on a large piece of paper so that new concepts can be formed by combining previous ones. The mapping might help to see the entanglements or “action between (not in-between)” (Hickey-Moody & Page, Citation2015, p. 4) of theory, material and self. The exercise involves linking existing ideas with various given ideas in a step-by-step manner. At the end of the linking exercise, participants will choose a title for their chosen concept and write a paragraph explaining the concept in a layered manner. The concept will then be further developed in more depth in the participants’ own time.

In the process that we follow we are aiming for a more flattened ontology. A flat ontology suggests that humans are not the centre of being, but are relational to other beings (objects, nature, animals, etc.) that exist in their own right. MacLure (Citation2013, p. 660) argues that “[w]ords collide and connect with things on the same ontological level, and therefore language cannot achieve the distance and externality that would allow it to represent—i.e. to stand over, stand for and stand in for—the world”. According to Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987, p. 23), there is no clear division between a “field of reality (the world) and a field of representation (the book) and a field of subjectivity (the author)”. Jackson and Mazzei (Citation2012) call it an assemblange of connections between multiplicities.

The concept development process can also be described as a process of diffraction. Haraway (Citation2004, p. 69) argues that “diffraction is a mapping of interferences, not of replication, reflection or reproduction”. It shifts our focus and reflects on concepts from the outside, but being part of it—a relational understanding (Barad, Citation2007). Bozalek and Zembylas (Citation2017, p. 123) argue that diffraction offers “an enlarged vision of making a difference in the world as it provides additional affordances through its connection of the discursive and the material, with knowledges making themselves intelligible to each other in creative and unpredictable ways”.

4. The workshop: forcing unusual relations

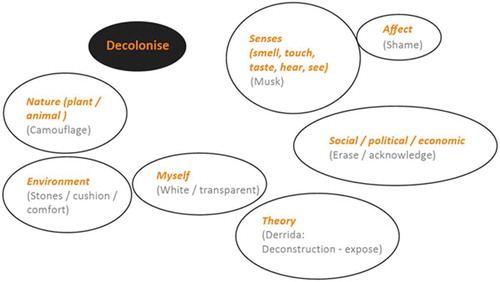

We are now going over to writing and drawing on the piece of paper. Use whatever pens you prefer. I am inviting you to think of an idea about which you are pondering in your own teaching/researching. I am showing you an example (see Figure ) of a process that I went through myself when I developed the workshop. I chose the idea “decolonise”. Firstly, decolonise was linked with a sense (smell, touch, taste, hear and see). What does decolonise smell or taste like? Decolonised, to me, smells like musk and tastes like soil.

Figure 1. Example of the linking exercise with the given links in orange and possible answers in grey.

The links should happen spontaneously without trying to think logically. It could sometimes end up rather funny or even uncomfortable, but the linking should keep flowing without trying to make logical links. The aim is to get away from linear, logical thinking. Every circle in Figure represents a new link (text in orange) to your chosen idea—in my case, decolonise. See the reactions to the given links in grey. I linked decolonise with Derrida’s deconstruction and how deconstruction exposes and opens up possibilities, because I was at that stage reading Jackson and Mazzei’s Thinking with theory in qualitative research (Citation2012). When I for instance linked decolonise with an animal, the idea of a chameleon that can camouflage itself came up in my mind. When I linked it with the immediate environment in which I found myself, I thought how I was trying to be as comfortable as possible on the stony beach and how that linked with “decolonise”. I tried to come to terms with my own discomfort and uneasiness with decolonisation, but I kept feeling the stones below me and that reminded me of my reality. After I made all the links, one by one, I then chose a few keywords from my piece of paper. The words that I chose were camouflage/contrast/comfort/expose/acknowledge. I then used these words to create new combined words: conflage or camoupose. Combining words is only one way of creating a title for the concept. I then wrote a few sentences on my formed concept and it resulted in this: This is a feeling of being both very visible and transparent; feeling both exposed and wanting to camouflage myself. I seek both comfort and discomfort. It is a feeling of needing to settle the situation, but also unsettling the status quo. I call this in-between condition a “conflage” (or “camoupose”). This concept then needs to be thought through and further elaborated on.

I am asking you now to go through this process step by step. Firstly link your idea with a sense. Write down whatever comes in your mind or draw a picture if you prefer. Make all the links mentioned in the ovals. Take your time and let the ideas flow spontaneously without pondering whether they are making sense or are logical. If the link is humorous, laugh; if it is bizarre, enjoy the moment. Be fully in the space of experimentation and anti-disciplinary play. Allow your unconscious mind to make unpredictable connections. The sense making might happen hours or days later. This serious playing could remind us that we can imagine differently.

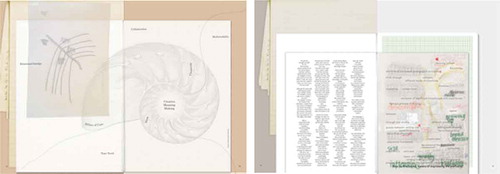

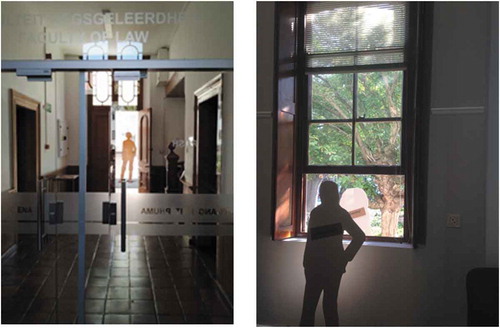

I also want to ask you to include another step that is not part of Figure before you choose your keywords. Get up, go to your book shelve and choose any unrelated book and link it with your chosen idea. At a workshop that I presented in the past, an unexpected thing happened. I took old library books with me that were to be shredded so that participants could choose a random book and link that with their chosen idea, but it worked out differently. For the workshop I used the back of old printed maps to recycle the paper, but the participants were so intrigued by the maps that they also linked their ideas with names or images on the maps. The words “electrified”, “railway” and “key” became further links. Participants also used the names of the places on the maps such as “Nooitgedacht” (meaning never thought of it) or “Tweespruit” (meaning two springs) and forced new meanings. These were linked with social issues such as transformation and insider/outsider (Figure ), which resulted in a pop-up art installation in the Law faculty building.

These unexpected ideas were also used by participants in writing poetry and rethinking the research articles on which they were working. Some developed their own concepts that were used in their articles and later continued to apply them in their teaching and research. Afterwards, remember to include some time to think and do free spontaneous writing, putting down all the ideas that crossed your mind during this engagement.

Figure 2. Insider/outsider pop-up art installation of ten figures placed inside and outside the law faculty building.

In some of the workshops I also included working with clay and inkblots with the maps or books (Figures and ). Clay is a very effective medium, as it is not a passive substance; the material itself can bring us to new concepts and understandings. The traces of the clay and the person working with the clay become visible—the skin imprint of the person on the clay and the traces of the clay on the person. They therefore affect and influence each other. The material, but also the process while making, matters, and the making is more important than the final result.

Figure 3. Working with clay, 2018 (part of the reconfiguring scholarship: writing, reviewing and publishing differently workshop sponsored by the cape higher education consortium (CHEC) and organised by Vivienne Bozalek).

In collaboration with other facilitators, we also allow time to read, experience and respond to one another’s concept mappings. Post-it notes were for instance used by fellow participants to respond and contribute to one another’s maps and so the maps grew beyond the initial paper (see Figure ). A constant forcing of concepts together is encouraged to see what newness of being/thoughts/pedagogies might emerge. The difference between a usual mind map and the forcefully linking exercise is that the normal flow of thinking is interrupted by forcefully linking unrelated ideas that could result in new creative ideas. You do not know what your own mind will produce next. Springgay and Zaliwska (Citation2015, p. 137) affirm that “[i]t is the anticipated next, which enables newness to come into existence”.

Figure 5. Growing maps, 2017 (part of the multimodal pedagogies and post-qualitative scholarship in higher education workshop sponsored by CHEC and organised by Vivienne Bozalek).

The process of each workshop should be documented. A publication, with the same title as the course, Reconfiguring scholarship: Writing, reviewing and publishing differently was published by SUN MeDIA in 2018. Each participant showed their process on a double-page spread. A layered effect was specifically chosen to emphasise the importance of process and experimentation. See pages of the publication in Figures and .

5. The workshop: ending the workshop

I am ending the workshop with a short reflection on the process. Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1994) argue that philosophers create concepts and artists create art, and that both are equally creative. It is not only philosophers and artists who are creating concepts and art; we can all create them. In this session we aimed to develop concepts using an art-making process of finding relations and forcing new connections. Creativity is often enhanced when unconventional things (these can be a material object, subject, existing concept or theory) are forced together to form new meanings. Jackson and Mazzei (Citation2012, p. 1) plugged one text into another (theory into data or the other way round), but also plugged in “ideas, fragments, theory, selves, sensations”. The latter relate to the process in which we are now engaged. The final aim for the developed concepts is to not remain a concept, but to become a process (borrowed from Jackson & Mazzei, Citation2012, p. 1).

I hope that these linking exercises and zigzag engagements open up new thoughts and images that you found productive. In a very modest way I tried steering away from the universal by following a simple process of linking unrelated concepts and experimenting in a material, tangible and embodied way. It can be considered as a tool to get unstuck—to take the neuron highways to unexplored side roads. The task of the concept creator/artist/researcher is to “establish non-pre-existent relations between variables” to construct new possibilities and modes of existence (Smith, Citation2014, p. 185). These creative flowing processes often require practice and to manage it in a few hours might be a challenge. It is a slow and evolving process to develop concepts. Not all concepts developed would be usable; possibly only one out of ten might be. However, the linking and relating process that we followed and what we learn from the process of creating concepts could be valuable for opening up new avenues of thinking. The playful art-linking process is simply fostering the conditions for creative production.

6. Conclusion

The workshops took place during 2017–2019 at various universities around Cape Town, South Africa. The workshops developed progressively after the student protests during 2015–2016, when tension between students and lecturers developed that created a stagnant situation. Because of their playful nature, despite engagement with serous topics, these workshops became a way of narrowing the gaps between students and lecturers. The use of an art process and the development of their personalised concepts that described their understanding of, for instance, social transformation or decolonisation, became an alternative way to engage in an embodied and discursive manner, which enabled the production of new knowledge.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elmarie Costandius

Elmarie Costandius is an associate professor in Visual Arts at the Visual Arts Department at Stellenbosch University, South Africa and coordinates the MA in Visual Arts (Art Education). She studied Information Design at the University of Pretoria and continued her studies at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam, and completed a master’s in Globalisation and Higher Education at the University of the Western Cape. Her PhD in Curriculum Studies (Stellenbosch University) focused on social responsibility and critical citizenship in art education. Elmarie has published in the field of art education, critical citizenship, decolonisation and social justice in local and international journals.

References

- Andrew, D. P. (2011). The artist’s sensibility and multimodality: Classrooms as works of art (Unpublished PhD thesis). University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg.

- Barad, K. M. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bozalek, V., & Zembylas, M. (2017). Diffraction or reflection? Sketching the contours of two methodologies in educational research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(2), 111–10. doi:10.1080/09518398.2016.1201166

- Deleuze, G. (1995). Negotiations, 1972–1990: European perspectives. New York, NY: Colombia University Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. (B. Massumi, Trans.). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. (Original publication 1980.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1994). What is philosophy? (H. Tomlinson & G. Burchell, Trans.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Gannon, S., & Lampert, J. (2017). Academic writing, creative pleasure and the salvaging of joy. In S. Riddle, M. Harmes, & P. Danaher (Eds.), Producing pleasure in the contemporary university (pp. 201–212). Rotterdam: Sense.

- Haraway, D. J. (2004). The haraway reader. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Henricks, T. S. (2006). Play reconsidered: Sociological perspectives on human expression. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Hickey-Moody, A., & Page, T. (2015). Arts, pedagogy and cultural resistance: New materialisms. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hicks, L. A. (2004). Infinite and finite games: Play and visual culture. Studies in Art Education, 45(4), 285–297. doi:10.1080/00393541.2004.11651776

- Hofstadter, D. R. (1985). Metamagical themas: Questing for the essence of mind and pattern. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. A. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives. London: Routledge.

- MacLure, M. (2013). Researching without representation? Language and materiality in post-qualitative methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (Special Issue: Post-Qualitative Research), 26(6), 658–667. doi:10.1080/09518398.2013.788755

- Manning, E. (2014). Against method. YouTube. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZEUZ6PWzJqU

- Rajchman, J. (2008). A portrait of Deleuze-Foucault. In S. OSullivan & S. Zepke (Eds.), Deleuze, Guattari and the production of the new (pp. 80-90). New York: Continuum.

- Richardson, L., & St Pierre, E. A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 959–978). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Smith, D. W. (2014). Concepts and creation. In R. Braidotti & P. Pisters (Eds.), Revisiting normativity with Deleuze (pp. 175–188). London: Bloomsbury.

- Springgay, S., & Zaliwska, Z. (2015). Diagrams and cuts: A materialist approach to research-creation. Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies, 15(2), 136–144. doi:10.1177/1532708614562881

- St. Pierre, E. A. (2015). Practices for the “new” in the new empiricisms, the new materialisms, and post qualitative inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & M. D. Giardina (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry and the politics of research (pp. 75–95). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Taguchi, H. L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2017). Using concept as method in educational and social science inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(9), 643–648. doi:10.1177/1077800417732634

- Truman, S. E., & Springgay, S. (2016). Propositions for walking research. In K. Powell, P. Bernard, & L. Mackinley (Eds.), International handbook for intercultural arts (pp. 259–267). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ulmer, J. (2017). Composing techniques: Choreographing a postqualitative writing practice. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(9), 728–736. doi:10.1177/1077800417732091