Abstract

The training of teachers is one of the most critical factors in improving the quality of teaching and assessment in the classroom. EFL teachers need to be literate in language assessment; this can be achieved through training. A total of 147 Junior High School EFL teachers was surveyed to identify their training needs in assessmen. Semi-structured interviews with 10 randomly selected teachers were also conducted, and analysed using thematic analysis. The study identified three competencies that teachers expected to gain from assessment literacy training: the ability to select tests for use, ability to develop tests’ specification, and ability to develop test tasks and items. More importantly, the study results suggest that teachers need ongoing practical training in a range of topics with different priorities. These findings offer guidance for planning effective teacher training and the design of modules based on teachers’ needs.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Previous studies have discussed the importance of improving teachers’ assessment literacy and considering teachers’ various needs regarding their assessment knowledge and skills. Nonetheless, little is known about EFL teachers’ needs for training in assessment literacy. The current study explores Indonesian junior high school EFL teachers’ training needs for assessment literacy, by examining what teachers expected from assessment literacy training and how these aspects might help them in daily assessment practices. Findings of the study will be significant for school administration, local government and educational regional bodies, in planning effective teacher training and the design of modules based on teachers’ needs.

1. Introduction

Language assessment literacy is a key concept in language assessment (Vogt & Tsagari, Citation2014), as assessment performs a vital role in the teaching and learning process (Lam, Citation2015). Teachers’ assessment literacy comprises their assessment knowledge and skills, and how teachers conceptualise assessment in the context of their classroom practice (Xu & Brown, Citation2016). The success of the assessment will impact on the quality of learning and student achievement; thus, it is imperative that teachers have adequate assessment literacy. The term “assessment literacy” refers to the fundamental principles of assessment and skills, which are needed to assess students’ achievement and development (Stiggins, Citation1991). Stiggins believes that teachers with an appropriate level of language assessment literacy are proficient in the following competencies: 1) setting clear objectives to assess, 2) comprehending the importance of assessing various achievements, 3) choosing a suitable assessment method, 4) collecting data of students’ achievement based on students’ performance, and 5) avoiding bias in the assessment which can arise from a technical issue. Djoub (Citation2017) further describes assessment literacy as teachers having sufficient knowledge to choose what to assess and which method to use, based on specific objectives; and also to determine what decisions will be executed in assessing student achievement. In other words, teachers with good assessment literacy know the right method for collecting reliable data regarding student performance, know how to use assessment results to support student learning, and are able to communicate the assessment results effectively and accurately.

Several studies have been conducted in various contexts, demonstrating significant results regarding teacher assessment literacy. For instance, Yamtim and Wongwanich (Citation2014) investigated the assessment literacy level of primary school teachers in Thailand, indicating that these teachers still have a low level of assessment literacy. M. Rahman (Citation2018) studied the perceptions and practices of assessment literacy among science teachers, and found that the teachers’ perceptions of assessment could be categorised as the assessment of learning (summative); also, that there was no consistency between teachers’ perceptions and their practices in the classroom. In the context of teaching foreign languages, Shim (Citation2009) questioned primary school English teachers in Korea, focusing on their perceptions and practices towards assessment literacy; this revealed that even though the teachers had good literacy, they did not practise their knowledge in the classroom assessment activities. Djoub (Citation2017) examined the impact of teacher literacy on their assessment practices in the classroom, by collecting data from online surveys of foreign language teachers around the world; she found that teachers lacked assessment literacy, as evidenced by their daily assessment practices in class. The teachers in this study mostly conducted assessments with the aim of giving grades, instead of improving students’ learning.

However, research shows teachers still have an inadequate understanding of assessment principles (Popham, Citation2009); hence, they need to improve their assessment literacy. For example, Djoub (Citation2017) found that teachers lacked literacy in assessment, as was evident in their daily assessment practices. Similarly, M. Rahman (Citation2018) reported that there was no consistency between teachers’ perceptions of assessment and their practices. Recognising the importance of teacher assessment literacy, researchers and practitioners have explored what can be done to improve this ability. Even teachers who claimed they had good assessment knowledge expressed the need to have more training in assessment (Zhang, Citation2018). One way to achieve this is to conduct high-quality teacher training, as professional development and training activities would provide teachers with knowledge and skills, as well as supporting the improvement of assessment literacy (Koh, Citation2011; Vogt & Tsagari, Citation2014).

Several studies have therefore investigated the consequences of and need for training EFL teachers in the area of assessment literacy. For example, Koh’s (Citation2011) study emphasised how professional development affected teachers’ assessment literacy. The findings of Koh’s study revealed that the group of teachers who were engaged in a two-year continuous professional development programme had substantially improved their assessment literacy, especially their understanding of authentic assessment. Furthermore, research also indicated that teachers have different interests and needs regarding training. Vogt and Tsagari (Citation2014) found that teachers in their study had inadequate training, and thus conveyed their need to be trained in a different area of language testing and assessment. Similarly, Zhang’s (Citation2018) study revealed that although Chinese language teachers of all levels of assessment knowledge expressed their common need for practical language assessment training, they had different interests in terms of training topics. In more recent research, Firoozi et al. (Citation2019) found that teachers needed training on language assessment knowledge and skills, especially topics such as designing rubrics for assessing speaking and writing skills.

In short, the above studies reaffirm the importance of improving teachers’ assessment literacy and considering teachers’ various needs for assessment knowledge and skills, regarding test design and development, large-scale standardised testing, classroom testing and washback, validity, and reliability. Nonetheless, more studies are needed to explore EFL teachers’ needs for training in assessment literacy, especially in the Indonesian context. In Indonesia, once student teachers have graduated from teacher training institutions and become teachers, they are obliged to participate in teacher trainings to further develop their knowledge and skills (A. Rahman, Citation2016). The government holds trainings for teachers regularly in the areas of teaching, learning and assessment; such as teaching strategies and assessment methods. Schools, in turn, assign their teachers to attend the trainings. However, it is questionable whether such trainings meet EFL teachers’ needs. For instance, Fulcher (Citation2012) argues that teachers are aware of the diversity of needs that are not yet accommodated in the existing trainings provided for them. Therefore, the following research questions should be addressed: What are the EFL-specific training needs in assessment literacy? Are there differences in the assessment training needs of EFL teachers of different ages and educational backgrounds? The present study builds on the 2018 study by Zhang, by employing interviews as a tool to gather more detailed information about teachers’ training needs, and by targeting EFL teachers exclusively as participants. Specifically, this study examines what EFL teachers said their training needs were, after they had participated in several trainings administered by the government. The gathered data are used to design a teacher training programme to form part of EFL teachers’ professional development.

2. Methods

The current study employed a mixed-method research design to explore Indonesian junior high school EFL teachers’ training needs for assessment literacy. “Junior high school” in this context includes the 7th through 9th grades of schooling. To this end, 147 Indonesian junior high school EFL teachers were surveyed, 10 of whom were interviewed. The demography of the participants is summarised in the following Table .

Table 1. Demography of the participants

In the current study, a five-point Likert scale questionnaire by Fulcher (Citation2012) was adopted as the survey instrument, which included three demographic questions and 23 survey items. The 23 survey items were employed to measure four aspects of teachers’ training needs for assessment literacy, with the respective items as follows: test design and development (6 items), large-scale standardised testing (8 items), classroom setting and washback (7 items), and validity and reliability (2 items). Table below summarises the aspects of teachers’ training needs and their indicators.

Table 2. Aspects of teachers’ training needs and their indicators

All the items in the survey were translated into Bahasa Indonesian to help teachers comprehend the information given in the instrument. The translation was read and reread to ensure its readability, and that it reflected the intended meaning of the original questionnaire. The survey was developed and distributed online using Google Forms to facilitate data collection and tabulation (Ningsih et al., Citation2018). The quantitative data collected from the survey were analysed with the Rasch Rating Scale Model, using Winsteps software (Linacre, Citation2018). Prior to analysis, the data were tabulated using Excel, and via the Winsteps application the raw scores for each participant were transformed into log odd units (logit). Rasch analysis was conducted to evaluate the reliability and validity of the inventory, as well as to analyse the participants’ responses regarding their training needs for assessment literacy.

In addition to the survey, semi-structured interviews were conducted to follow up on the findings from the survey. To this end, 10 out of 147 EFL teachers were randomly selected to participate in the interviews. Each interview was on a voluntarily basis, and prior to the interview, teachers were asked for their consent. The interviews were conducted in native Bahasa Indonesia to allow teachers to fully express themselves; this enabled researchers to obtain more detailed information (Murray & Wynne, Citation2001). The interviews were audio-recorded, and lasted 10 to 20 minutes. Prior to the thematic analysis of the data, the interviews were transcribed verbatim. The interview transcripts were read and reread to allow the researcher to comprehend the information given by the participants; then the data were coded and themed, to reflect Indonesian junior high school EFL teachers’ perceptions of training needs for assessment literacy.

3. Results

3.1. Findings from the quantiative study

3.1.1. Instrument reliability

Statistical fit analysis was conducted to understand the reliability of the instrument used for the data collation process. The fit statistics scores reflect the reliability indices reporting the quality of the instrument, the separation indices, and Cronbach’s alpha. Table presents the reliability score, referring to the fit statistics of the measurement.

As shown in Table , person and item separation outputs indicate that the instrument is excellent and reliable. Person reliability obtained a score of 0.96, which means that respondents reflected excellent reliability in answering each item of the instrument, while the item reliability score of 0.97 indicates that the questionnaire items had an excellent ability to measure respondents’ opinions. In addition, the person separation index (5.23) and item separation index (5.66) suggest an excellent spread of data. The high separation index obtained in the current study shows that the instrument had good quality and could distinguish the “person abilities” (Linacre, Citation2012) and “item difficulties” (Boone et al., Citation2014). More importantly, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was high (0.98), indicating a high level of reliability (Sumintono & Widhiarso, Citation2014).

Table 3. Reliability of the instrument

3.1.2. EFL teachers’ specific training needs in assessment literacy

To address the first research question (What are EFL teachers’ specific training needs in assessment literacy?), the logit values obtained from the raw scores were evaluated using Rasch, to help identify and reflect the participant ability measure of the assessment literacy aspects in the questionnaire. The output model produced by Rash allows researchers to identify which items are considered most important by the respondents (see Figure ).

As shown in the above figure, a Wright map was developed to present item-person maps, showing a logit value item (henceforth LVI) for each item and person. The left-hand side of the map reveals the distribution of participants’ evaluation of the questionnaire items, ranging from the least important to the most important. The other side shows the frequency of the participants’ selection of the items. The map indicates three essential items that reflected teachers’ assessment literacy training needs, including “selecting tests for use” (N9, LVI = -0.93), “writing test specifications” (N4, LVI = −1.20), and “writing tasks and items” (N5, LVI = −1.20). These three items are considered as the primary needs of teachers, in improving their comprehension and assessment literacy abilities.

3.1.3. Differences in EFL teachers’ training needs in assessment literacy by participants’ demography

DIF analysis (Differential Item Functioning) was administered to answer the second research question (Are there any differences in assessment training needs among EFL teachers of different ages and educational backgrounds?). DIF analysis facilitates the determination of teachers’ responses to items. In this case, the teacher’s response to each item was valued based on their demographic profile.

3.1.3.1. EFL teachers’ training needs in assessment literacy by age

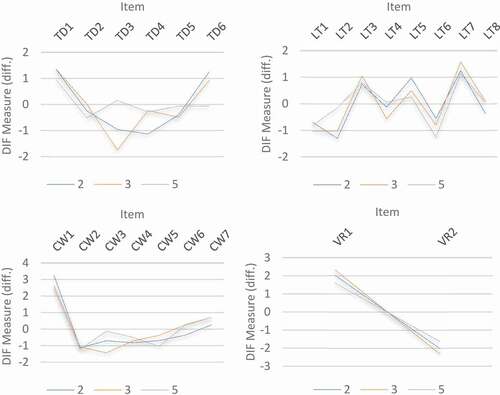

Teachers’ age influenced how they perceived assessment literacy training needs. Figure presents EFL teachers’ training needs according to their age.

Figure 2. EFL teachers’ training needs by their age.

Note: J = <20 years, K = 21–25 years, L = 26–30 years, M = 31–35 years, N = 36–40 years, O = >40 years

In the aspect of Test design and Development (TD), teachers aged <20 years, 26–30 years, and >40 years indicated that “evaluating language tests” (TD3, diff. J = −1.0958, diff. L = −1.0017, diff. O = −1.0051) and “rating performance tests” (TD4, diff J = −1.0958, diff. L = −1.0017, diff. O = −1.0051) were their most important needs, while teachers aged 21–25 years thought that “rating performance test” (TD4, diff. = −1.2904) was the most needed material. In addition, teachers aged 31–35 years considered “evaluating language test” (TD3, diff. = −1.4718) as the most important aspect in assessment literacy, while teachers aged 36–40 required “writing test specifications” (TD5, diff. = −0.8682) in assessment literacy training. “Writing test tasks and items” (TD1, diff. K = 1.988, diff. M = 0.8756, diff. N = 1.2155, diff. O = 1.4234) was considered less important by teachers aged <20 years and 26–30 years, whereas “procedure in test design” (TD6, diff. J = 1.1585, diff. L = 1.2219) was identified as less required material by teachers aged 21–25 years and >31 years.

Furthermore, in the domain of Large-scale and standardised testing (LT), teachers aged <20 years, 31–35 years, and 36–40 years confirmed that “scoring close-response items” (LT6, diff. J = −1.8598, diff. M = −0.7766, diff. N = −0.6853) were the most needed training materials, while teachers aged 21–25 years, 26–30 years, and >40 years old required training in “interpreting scores” (LT2, diff. K = −0.699, diff. L = −1.2105, diff. O = −1.5358). Teachers thought some materials were less required, such as “standard-setting” and “principles of educational measurement”. It is interesting that “standard-setting” (LT3, diff. = 0.831) was viewed negatively by teachers aged <20 years, while teachers aged >20 years were more negative about “principles of educational measurement” (LT7, diff. K = 0.723, diff. L = 1.3179, diff. M = 1.0838, diff. N = 1.2768, diff. O = 1.6431).

Regarding Classroom and Washback (CW) aspects, teachers aged <20 years, 26–30 years, and >40 years tended to choose “classroom assessment” (CW2, diff. J = −2.6284, diff. L = −1.1197, diff. O = −1.2431) as the material they required most. Teachers aged 21–25 years and 31–35 years old desired “ethical considerations” (CW5, diff. K = −1.1178, diff. M = -1.4324) to be discussed in the assessment literacy training. Teachers aged 36–40 years regarded “selecting tests for use” (CW3, diff. = −0.8829) as the most important material. Surprisingly, all teachers agreed that “preparing lessons” (CW1, diff. J = 2.0175, diff. K = 2.7003, diff. L = 2.6101, diff. M = 4.3702, diff. N = 2.4908, diff. O = 3.1193) was less required.

In terms of Validity and Reliability (VR), all teachers thought “validation” (VR2, diff. J = −0.5253, diff. K = −1.8775, diff. L = −0.0019, diff. M = −3.4979, diff. N = −1.6027, diff. O = −2.5379) was the most required material, while perceiving “reliability” (VR1, diff. J = 0.5049, diff. K = 1.8457, diff. L = 0.0044, diff. M = 3.4759, diff. N = 1.5777, diff. O = 2.5285) as being less required.

3.1.3.2. EFL teachers’ training needs in assessment literacy by educational background

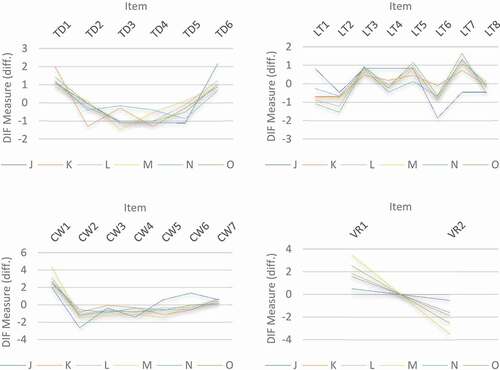

The analysis of DIF also provides results for each indicator based on teachers’ educational background (see Figure ). In the aspect of Test design and Development (TD), the result of the DIF analysis shows that bachelor degree teachers perceived “rating performance tests” (TD4, diff. = −1.1274) as the most important materials to be presented during the training, while teachers with a master’s degree chose “evaluating language tests” (TD3, diff. = −1.738), and teachers with other educational backgrounds mentioned “deciding what to test” (TD2, diff. = −0.5102). Despite the differences in most important materials, teachers across educational backgrounds considered that “writing test tasks and items’ materials” was less important (TD1, diff. 2 = 1.3387, diff. 3 = 1.3456, diff. 5 = 0.9546).

In addition, for Large-scale standardised testing (LT) indicators, teachers with a bachelor’s degree asserted that “interpreting scores” (LT2, diff. = −1.2924) was the most needed material, while teachers with a master’s degree confirmed they required “test analysis” (LT1, diff. = −1.0228), and teachers with other educational backgrounds considered “scoring close-response items” (LT6, diff. = −1.2437). The materials related to “principles of educational measurement” (LT7, diff. 2 = 1.2449, diff. 3 = 1.5745, diff. 5 = 1.1248) were identified as less required by teachers from all educational backgrounds.

Furthermore, in the domain of Classroom and Washback (CW), bachelor’s degree and other educational background teachers similarly indicated that “classroom assessment” (CW2, diff. 2 = −1.1159, diff. 5 = −1.2097) was the most important material, while teachers with a master’s degree mentioned “selecting tests for use” (CW3, diff. = −1.4244). The item “preparing learners” (CW1, diff. 2 = 3.2638, diff. 3 = 2.6354, diff. 5 = 2.4464) was considered as less required by all teachers across educational backgrounds. Regarding the aspects of validity and reliability (VR), teachers’ responses across educational backgrounds remained similar. Teachers considered that training materials related to “validation” (items VR2, diff. 2 = −2.0197, diff. 3 = −2.3218, diff. 5 = −1.6315) were more required than those for “reliability” (items VR1, diff. 2 = 2.0197, diff. 3 = 2.3193, diff. 5 = −1.5992).

3.2. Findings from the qualitative study

The qualitative part of the current study was conducted to further investigate teachers’ needs and perceptions of training in assessment literacy. Several themes regarding these issues emerged from the 10 interviews, as discussed below.

3.2.1. The importance of teacher training in assessment

All interviewed teachers acknowledged the importance of and the need for training in assessment literacy, in order to upgrade their knowledge and skills. For example, Dewi, a teacher in a public junior school, stated: “Such teachers’ training is very much needed, as my colleagues assess students as they wish. They do not follow the guidelines issued by the ministry because they do not fully understand how to do good assessment practice.” Similarly, Gina affirmed that “I need training, because until now, I have still not fully understood the appropriate instruments to be used to assess different language elements and skills”. Another teacher, Adel, expressed that she had gained more knowledge, skills and confidence by attending training, and hoped to receive more regular training. She said: “All teachers need that kind of training. I attended one training this year, and I must say I learned a lot. I became more confident in assessing my students.”

3.2.2. Training content

Most teachers expressed their concern about the appropriateness of the training, in terms of the content presented. Several teachers found the training topics were not relevant to their needs; for instance, Toni commented: “some topics are not relevant to our needs. We do not need to learn about statistics. What we need are assessment tools we can use in the classroom.” In the same vein, Rina asserted that learning about high-stake testing is useful, but she wanted more training time to be allocated to assessing the four language skills.

However, several teachers commented on the practicality of the training content, indicating that although the contents of the training they attended were of relevance, they were less practical. As Dedi said, “the contents of most training/workshops I attended were too theoretical. Learning about theories of assessment and testing is not enough. We come home and we’re still confused”. Another teacher, Dini, also expressed a similar concern: “I expected more practical things from a training, where I can practise designing classroom tests, creating rubrics, and others.”

All teachers interviewed also declared that they required up-to-date content. As the current education emphasises teaching higher-order thinking skills (HOTs), teachers participating in the interview expressed an urgent need to learn about assessing HOTs. Gina said, “The government, the districts always talk about HOTs, and that teachers must be able to teach and assess HOTs, so I think teachers should receive more training on this”. Another frequently mentioned topic was the use of ICT in assessment; as Elli commented: “this is just the era of ICT. My students all have a smartphone and use it to find resources for their homework and other things. They are the millennial generation. ICT can facilitate students’ learning. I want to be able to use technology to teach and assess my students. So far, I’ve learned to use Google Forms and have tried to use it. However, I need to learn more about other tools.” Furthermore, another teacher commented: “I need to learn how to search for good assessment resources on the Internet, and perhaps to learn some online platforms I can use to assess my students.”

3.2.3. Duration of training

Training length emerged as an essential issue for the teachers, with most declaring that they had a one-off short duration of training ranging from 2 h to 1 day. Several teachers stated that this type of training is less useful for them; as Lili said: “the trainings I have attended mostly lasted for 2 days to a half-day. We were there just listening to the resource person, and went home. No module, no practice, no follow up. Not useful.” Likewise, one teacher emphasised the need for a more extended and continuous training model, where teachers have the opportunity to practise and be mentored. Rina said: “I do not mind learning some theories of assessment for a day, but there should be a follow-up training which is more practical, where I can go home with a product, such as assessment tasks that I can use in my classroom.”

3.2.4. Training opportunities

Most teachers felt they needed more training opportunities. For instance, Ela said: “I want to attend training on assessment. However, where should I go? I rarely get any information about training. If any, for example, training is conducted by the district office, only certain English teachers are assigned by the district to attend the training.” Other teachers confirmed this view that not all teachers were given the opportunity to attend training. Dina asserted, “getting into workshops and training is not easy. Let’s say there are six English teachers in one school, sometimes only one or two teachers are appointed to go. The rest are expected to stay at school to teach”.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Based on the questionnaire, the training needs for the EFL teachers were classified into the following categories: test design and development; large-scale standardised testing; classroom testing and washback; validity and reliability. Concerning the test design and development category, writing test tasks and items and writing test specifications were the trainings most required by teachers, followed by evaluating language tests. In terms of the large-scale standardised testing category, teachers’ greatest training needs were to learn about test analysis, interpreting scores, and standard-setting. For the classroom testing and washback category, the most needed training concerned selecting tests for use, preparing learners, and classroom assessment, respectively. In this category, the history of language testing was the training content that teachers had no interest in learning about, and teachers wanted to learn more about validity than reliability. In summary, selecting tests for use, writing test specifications, and writing tasks and items were the areas in which teachers most required training. Additionally, qualitative results revealed that teachers wanted up-to-date specific content, such as assessing HOTs and using ICT in assessment, to respond to the demands of the current developments in policy and technology—that is, practical but up-to-date training.

The qualitative findings also revealed similar patterns, with most teachers expressing the need for a practical training approach to help them with the day-to-day practice of classroom assessment. It has been recognised that teachers often experience difficulties relating theories to their actual tasks in the classroom (Grossman et al., Citation2009). However, training practices often require teachers to only listen to theories; thus, they are irrelevant to teachers’ needs (Ayvaz-Tuncel & çobanoglu, Citation2018), as several teachers in this study experienced. Furthermore, teachers also commented that the duration of the training they participated in was mostly one-shot and sporadic one or two-day instructions. Thus, to be able to accommodate teachers’ need for practical instruction, the duration of the training should be planned accordingly. These findings suggest that teacher training in assessment needs to shift to continuous hands-on and practical instruction, potentially involving follow-up sessions. As Koh (Citation2011) found in her study, ongoing and sustained professional training provided teachers with the opportunities to survey and practise appropriate assessment methods in their classroom context.

As the interviewed teachers acknowledged the importance of training in assessment, they also showed great interest in participating in more training. Nonetheless, they did not have many opportunities to attend training, due to a lack of information about such programmes. Several teachers could not attend training every time the opportunity arose, because the school policy required teachers to take turns, so that students were not left unattended. These findings are broadly in line with those of Vogt and Tsagari (Citation2014), who found that teachers received an insufficient amount of training; hence, they learnt about assessment from colleagues and through daily classroom assessment practice.

The results of Rasch analysis showed that teachers of different ages and educational backgrounds have specific needs in terms of assessment literacy training. Nonetheless, most teachers opted for a practical type of training. In terms of age groups, it was found that teachers of different ages shared common training needs relating to the test design and development category—except for the younger teachers aged below 20 years old, who were more interested in learning about classroom testing and washback. This may be because they had limited experience, so they wanted to learn about more advanced knowledge in assessment.

Concerning the correlation between teachers’ training needs and their academic qualifications, teachers with a bachelor’s degree or master’s degree in English Education chose items within the test design and development category as their top training needs, while the most needed training for teachers with other educational backgrounds fell under the classroom testing and washback category. This may be because teachers with an English Education background had more knowledge in language assessment fundamentals, and felt the need for training in designing and developing a test to put their knowledge into practice.

Overall, this study offers insights into EFL teachers’ needs regarding assessment literacy training. Teachers in this study are keen to keep pace with professional activities, and welcome the opportunities to participate in training sessions that accommodate their needs. Thus, the findings of the present study emphasise the importance of placing teachers’ needs at the heart of the training design process. The government has made professional development mandatory for all teachers. However, a needs analysis should be conducted to identify teachers’ needs and interests. Based on the results of the needs analysis, the government or training institutions may create a variety of training contents to cater for teachers’ different needs. Teachers from different educational backgrounds, for example, should be enabled to choose training contents that suit their individual needs for assessment literacy. The training structure should also be made flexible, through a mixture of online and offline modes of training. Furthermore, as top-down one-off conventional training has brought dissatisfaction to teachers (Muijs et al., Citation2014), the government should provide more support for school-based professional development activities. This structure would give EFL teachers more options and control over their professional development training.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of Republic of Indonesia during the research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Siti Zulaiha

Siti Zulaiha is a senior lecturer at the Graduate School of University of Muhammadiyah Prof. DR. HAMKA (UHAMKA), Jakarta, Indonesia. She obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Queensland, Australia. Siti is currently a unit head of quality assurance at the Department of English Education at Graduate School, UHAMKA. Her research interest includes language assessment and the teaching of English as a foreign language.

Herri Mulyono

Herri Mulyono is a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Teacher Training and Pedagogy of the University of Muhammadiyah Prof. DR. HAMKA (UHAMKA), Jakarta, Indonesia. He obtained his Ph.D. from the University of York, UK. His research interests include the use of technology to enhance foreign language teaching and learning and teachers’ professional development. He is currently the head of the Scientific Publication Support and Enhancement Unit at the University.

References

- Ayvaz-Tuncel, Z., & çobanoglu, F. (2018). In-service teacher training: Problems of the teachers as learners. International Journal of Instruction, 11(4), 159–13. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.11411a

- Boone, W. J., Staver, J. R., & Yale, M. S. (2014). Rasch analysis in the human sciences. Springer.

- Djoub, Z. (2017). Assessment literacy: Beyond teacher practice. In R. Al-Mahrooqi, C. Coombe, F. Al-Maamari, & V. Thakur (Eds.), Revisiting EFL assessment: Critical perspective (pp. 9–27). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32601-6

- Firoozi, T., Razavipour, K., & Ahmadi, A. (2019). The language assessment literacy needs of Iranian EFL teachers with a focus on reformed assessment policies. Language Testing in Asia, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-019-0078-7

- Fulcher, G. (2012). Assessment literacy for the language classroom. Language Assessment Quarterly, 9(2), 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2011.642041

- Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2009). Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875340

- Koh, K. H. (2011). Improving teachers’ assessment literacy through professional development. Teaching Education, 22(3), 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2011.593164

- Lam, R. (2015). Language assessment training in Hong Kong: Implications for language assessment literacy. Language Testing, 32(2), 169–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532214554321

- Linacre, J. M. (2012). A user’s guide to Winsteps: Rasch model computer programs (version 3.74). Beaverton. Retrieved from https://www.winsteps.com/manuals.html

- Linacre, J. M. (2018). A user’s guide to Winsteps Ministep Rasch-model computer programs (version 4.3.1). Beaverton. Retrieved March 19, 2019 https://www.winsteps.com/a/Winsteps-Manual.pdf.

- Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art - teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.885451

- Murray, C. D., & Wynne, J. (2001). Researching community, work and family with an interpreter. Community, Work & Family, 4(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/713658930

- Ningsih, S. K., Narahara, S., & Mulyono, H. (2018). An exploration of factors contributing to students’ unwillingness to communicate in a foreign language across Indonesian secondary schools. International Journal of Instruction, 11(4), 811–824. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.11451a

- Popham, W. J. (2009). Assessment literacy for teachers: Faddish or fundamental? Theory into Practice, 48(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802577536

- Rahman, A. (2016). Teacher professional development in Indonesia: The influences of learning activities, teacher characteristics and school conditions. [Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Education]. University of Wollongong.

- Rahman, M. (2018). Teachers’ perceptions and practices of classroom assessment in secondary school science classes in. International Journal of Science and Research, 7(6), 254–263. https://doi.org/10.21275/ART20183034

- Shim, K. N. (2009). An investigation into teachers’ perceptions of classroom-based assessment of english as a foreign language in korean primary Education.

- Stiggins, R. J. (1991). Relevant classroom assessment training for teachers. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 10(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1991.tb00171.x

- Sumintono, B., & Widhiarso, W. (2014). Aplikasi model rasch untuk penelitian ilmu-ilmu sosial. (B. Trim Ed.). Trim Komunikata. Second

- Vogt, K., & Tsagari, D. (2014). Assessment literacy of foreign language teachers: Findings of a European study. Language Assessment Quarterly, 11(4), 374–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2014.960046

- Xu, Y., & Brown, G. T. L. (2016). Teacher assessment literacy in practice: A reconceptualization. Teaching and Teacher Education, 58, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.010

- Yamtim, V., & Wongwanich, S. (2014). A study of classroom assessment literacy of primary school teachers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 2998–3004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.696

- Zhang, L. (2018). Investigating the training needs of assesment literacy among Singaporean Primary Chinese language teachers. In K. C. Soh (Ed.), Teaching Chinese language in Singapore: efforts and possibilities (pp. 167–177). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8860-5