Abstract

Observation is one of the central elements of kindergarten teachers’ education and the profession. Through a survey in Norway, in which 1311 in-service teachers, kindergarten managers, and pedagogy teachers participated (response rate 39.9%), this study examines how the use of and rationale for observation in kindergarten practice and kindergarten teacher training are characterized, as well as which methods are deemed relevant. The results show that the respondents consider observation important, and participatory observation and narrative methodology appear to be the most used and profession-relevant. However, there is a gap between intention and practice in terms of observation, and systematic observation appears to be infrequent. This finding raises the issue of whether teachers in preschools truly execute observation as a method. Differences between the professions in terms of their focus area in observation were revealed, and, surprisingly, children’s learning, as a focus, was the least emphasized.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Observation has a long history in kindergarten teachers' education and profession. This research investigates observation as a professional tool in Norwegian kindergartens and as a topic in kindergarten teacher education. Based on a survey among 1311 in-service teachers, kindergarten managers, and pedagogy teachers, this study determines the use of and rationale for observation in kindergarten practice and teacher training. The results reveal that observation is considered important for several reasons – to obtain knowledge pertaining to children’s development, out of concern for children, as preparation for parent-teacher conferences, for didactic work, and to develop pedagogical praxis. However, it appears that observational work is infrequent and informal, and does not focus on children’s learning. Increasing the opportunities for teachers carry out observation as per kindergarten policy documents is important, to ensure that all children are provided for in accordance with the Kindergarten Act, and to develop pedagogical practice.

1. Introduction

Observation is a well-established tool for professional practice in kindergartens worldwide and is, therefore, also part of the curriculum for preservice teacher education (Bruce et al., Citation2015; Clark, Citation2006; Podmore & Luff, Citation2012). Observation has comprised the foundation for kindergarten teachers’ knowledge base since the very first training programs and is highlighted in policy documents for kindergartens (Birkeland & Ødegaard, Citation2018; Broadhead, Citation2005). The reasons for carrying out observations may vary according to the values and professional mandate established in kindergarten curriculum (Alasuutari et al., Citation2014). It is important for a teacher to be aware of children’s needs, experiences, development, and learning processes, as well as their participation and inclusion in a given group (Alasuutari et al., Citation2014, p. 14). Learning observational skills and using the related tools represent opportunities to systematically and determinedly learn about children’s lives in preschool, as well as further their development and well-being (Birkeland & Ødegaard, Citation2019; Hedegaard, Citation2019; Knauf, Citation2019). Observation is fundamental to the process of pedagogical documentation (Fleet & Harcourt, Citation2018) and is highlighted as a means of learning about children’s perspectives (Clark et al., Citation2005). Observation is necessary for evaluation and quality development (Dalli, Citation2008; Eik et al., Citation2016; Elfstöm, Citation2013; Picchio et al., Citation2012; Sheridan et al., Citation2011) and can be carried out in various formats, some of which are visual and written records, narratives, checklists, and mapping (Bruce et al., Citation2015). However, there is less awareness today of the purpose and characteristics of observation, and its methods that are seen as relevant in kindergarten and kindergarten teacher education (KTE) (Birkeland, Citation2019; Clark, Citation2006; Emilson & Samuelsson, Citation2012). Therefore, we have investigated this topic through a quantitative study in the Norwegian context.

1.1. Kindergarten teacher education

Teacher education today is understood and highlighted as both on-campusFootnote1 (college/university) and in-service education (Lillejord & Børte, Citation2017); the coherence between the two is important (Canrinus et al., Citation2017). Historically, in-service education has occupied a central position in Nordic countries; in Norway, workplace-based learning has officially been positioned as a key element in the six-semester preparation required of kindergarten teachers (Oberhuemer, Citation2015, p. 119).

In Norway, 13 institutions offer KTE. The framework plan for KTE highlights pedagogy and practice as integrated into the six interdisciplinary areas of expertise in the three-year course. Pedagogy teachers and other on-campus teachers of different disciplines, in-service teachers, and the headmaster (manager) of the kindergarten share responsibility for student achievement (Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2012b, p. 8). According to § 3, in the national framework plan regulations for KTE, pedagogy is assigned the particular responsibility of securing coherence and profession-orientation.

Observation is emphasized to allow students to gain insights into the work of the kindergarten teacher, who will ideally use observation as a tool for self-reflection, to monitor the children’s demeanor and their care, and observe their play and learning needs (Norwegian University Council, Citation2018, p. 9). In the kindergarten teacher’s profession, observation is emphasized as an assessment of the health, well-being, experience, development, and learning of children and as a means of ensuring that all children are provided for in accordance with the Kindergarten Act and the current framework plan (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2017, p. 24).

Although profession-oriented and coherent education programs are the primary objectives of KTE (Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2012a, Citation2012b; Norwegian University Council, Citation2018), there is seemingly a lack of coherence with respect to observation. Observation methods emphasized in KTE are diluted or simply not used by kindergarten teachers, and several methods described in the curriculum are perceived by in-service teachers as having little relevance to the profession (Birkeland & Ødegaard, Citation2018).

1.2. Previous research

While play and a holistic approach to learning have been at the forefront in Nordic countries, and early childhood teacher preparation has been in concordance with and built on this tradition (Einarsdottir, Citation2013), these elements have not always been obvious in observational work. Evaluations of children’s abilities have increased (Basford & Bath, Citation2014; Franck & Nilsen, Citation2015; Samuelsson, Citation2010), and observation in concordance with a developmental psychological paradigm still appears to dominate the observational work conducted in Norwegian kindergartens (Birkeland & Ødegaard, Citation2018; Otterstad & Nordbrønd, Citation2015). Several researchers have highlighted that observation and documentation have not focused on the context and relationships in which children participate (Elfstöm, Citation2013; Fleer, Citation2011; Hedegaard, Citation2012; Karila et al., Citation2007; Samuelsson, Citation2010). Based on recent research, which considers children as participants (Fleer & Hedegaard, Citation2010; Garvis et al., Citation2015) and sees their development, learning, and formative development as intertwined with institutional practices (Hedegaard, Citation2019), the importance of developing pedagogical practice is revealed and requires praxis for critical reflection and discussions (Korthagen, Citation2016; Salo & Rönnerman, Citation2013; Sheridan et al., Citation2011). The ability to observe, analyze, and critically evaluate one’s professional practice requires time (Dalli, Citation2008), and teachers’ collegial learning is emphasized as foundational to achieving educational change (Sjølie, Citation2017, p. 56).

In Norway, studies on observation have mainly been conducted within qualitative research designs, with a primary focus on its practice in kindergartens (Børhaug et al., Citation2018; Frønes, Citation2017; Lyngseth, Citation2010; Otterstad & Nordbrønd, Citation2015; Ulla, Citation2014). Quantitative studies have highlighted observation as a commonly used tool in kindergartens (Gulbrandsen & Eliassen, Citation2013; Haugset et al., Citation2015), but its methods in use are not apparent. Studies have also highlighted a need for discussion on and clarification of key observation methods, and the methodology kindergarten teachers should utilize to demonstrate their knowledge and skills (Birkeland, Citation2018, Citation2019; Clark, Citation2006). Bjerkestrand et al. (Citation2015) showed that most educational institutions in Norway use the basic methodology book, Observation and Interview in the Kindergarten by Løkken and Søbstad (Citation2013), in which observation is defined as a threefold process: (a) observation through the senses, (b) description of the observation (the record) and (c) interpretation of the observation. The observation methods described in the book are as follows: participatory observation,Footnote2 ongoing protocol (running records), logging,Footnote3 time sampling,Footnote4 rating scales,Footnote5 video, sociogram,Footnote6 and stories from practice (narrative inquiry). However, Birkeland (Citation2018, Citation2019) shows that, in KTE learning settings, the focus was only on a few of these methods. The most commonly used ones were participatory observation, ongoing protocol, and stories from practice. Meanwhile, sociometry and digital tools were less emphasized.

Different mapping tools and programs offered by commercial entities (Åbro, Citation2016), such as TRAS,Footnote7 ALLIN,Footnote8 The Incredible Years,Footnote9 MIO,Footnote10 and Marte Meo, have found their way into kindergartens. Although several researchers have strongly critiqued several of these, especially The Incredible Years (Grindheim, Citation2017; Seland, Citation2017) and TRAS (Pettersvold & Østrem, Citation2012; Vik, Citation2017), their use, as part of observational practices in kindergartens, appears to be widespread (Engel et al., Citation2015; Haugset et al., Citation2015; Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2016; Sandvik et al., Citation2014). In KTE, Birkeland (Citation2018) found that pedagogy teachers were critical of TRAS as a tool for observation.

Børhaug et al.’s (Citation2018) literature review indicates that studies on observation have achieved varying results—most showed that observation was a commonly used method in kindergartens; some, however, found that written observations were infrequent, meaning that they were informal and not in line with the use of observation as a professional tool. It also appears that kindergarten teachers who completed their education more than a decade ago had a larger repertoire of observation methods than those who did within the last ten years. Birkeland and Ødegaard (Citation2018) demonstrated that informal observation was at the forefront of techniques used in kindergartens, and that collective reflections based on written observations were less common. Stories from practice appears to be the most common method and in-service teachers have perceived it as the most relevant to the profession. The sociogram method, on the other hand, is not well known. The focus of the observational work has been the interaction between the children, and not children’s participation, which is statutory in Norway. Furthermore, evaluating adults’ contribution appears to be a blind spot in the observations carried out in Norwegian kindergartens (Kallestad & Ødegaard, Citation2013), which corresponds with findings of studies conducted in other countries (i.e., Buldu, Citation2010; Emilson & Samuelsson, Citation2012; Lewis et al., Citation2019). This highlights the importance of educators’ awareness and active role in children’s learning processes—areas for further development in terms of the observation method used in kindergartens.

1.3. The aim of the study

Although observation is central to KTE and the profession and is considered a prerequisite for pedagogical work with children (Bruce et al., Citation2015; Norwegian University Council, Citation2018; Podmore & Luff, Citation2012), there is a lack of knowledge on how and why it should be used (Birkeland & Ødegaard, Citation2018; Børhaug et al., Citation2018; Frønes, Citation2017), as well as which methods are relevant (Birkeland, Citation2018, Citation2019; Clark, Citation2006). The present study investigated observation in KTE and kindergartens based on a national survey in Norway among pedagogy and in-service teachers, and managers in kindergartens. Our goal was to provide knowledge on it and examine observation as a tool in profession-oriented KTE. Another purpose was to investigate differences in how the various professions evaluated observation as a tool. The research ultimately aimed to answer the following question: Which observation methods are relevant in kindergarten teachers’ education and profession—and what characterizes the use and justification of observation in these fields?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Data for the present quantitative study were gathered through a national survey in 2018; respondents were pedagogy teachers, in-service teachers, and headmasters (managers) in kindergartens who were connected to KTE in Norway. All Norwegian educational institutions that offer KTE were contacted to obtain e-mail addresses (approved by Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD)). Information pertaining to the project was given to potential participants in an informational letter sent via e-mail, which also contained a link to the questionnaire. The data were collected electronically from June–September 2018, during which four reminders were also sent. The survey was carried out by Questback Essentials Norway, and data were delivered to the research group anonymously (i.e., without information about e-mail or IP-address [for further information see https://www.questback.com/information-security/]). It was, therefore, impossible to identify respondents. Participation was voluntary, and respondents had the option to withdraw while the survey was on, but not after it was confirmed as finished. A completed questionnaire was regarded as an active step of participation in the study.

Several of the addresses provided by the in-service teachers and a few of the managers were incorrect. In all, 3284 individuals received the questionnaire: 1663 in-service teachers, 1430 managers, and 191 pedagogy teachers.

2.2. The questionnaire

The questionnaire comprised 22 questions, which included background information (profession, further education if one was a manager, highest education level, gender, age group, affiliation by institution and time period for when educated as a kindergarten teacher). In this research, we asked about observation in the following areas: assessment of observation, understanding of participatory observation, relevant methods for KTE/Kindergarten, the use of observation/how often, focus, reasons for observation, transcription, and collective reflection (Table ). The questionnaire was developed based on previous research (Birkeland, Citation2018; Birkeland & Ødegaard, Citation2018) and then adjusted for the current work, to enable the respondents from different professions to answer it. A test panel comprising three experts evaluated the questionnaire, following which some minor changes were made to it.

Table 1. Questions from a national survey on observation as a professional tool in kindergartens and kindergarten education in Norway. Answer categories from the questionnaire are provided, as well as how they were grouped for the analysis

For some questions, the answer categories were grouped prior to the analysis (Table ). If 3% or less answered “Do not know” to a question, those answers were omitted; otherwise, they were included in the analysis. Further information about omitted responses is presented in Table .

Some (n = 32) of the respondents had identified themselves as affiliated to two educational institutions and, for the analysis, we determined which institution to use: the larger one, based on the number of students reflected in NSD’s database for statistics on higher education, was chosen as the current one. A total of 28 respondents had two roles. If both manager and in-service teacher, then they were definedFootnote11 as managers, while both in-service teachers and pedagogy teachers, or both managers and pedagogy teachers, were defined as pedagogy teachers.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for gender, age group, period of preschool teacher education, level of education, and affiliation by institution were provided for profession. The associations between profession and the variables regarding observation were analyzed using Pearson’s chi-squared test. Tests for linear trends were performed using Mantel–Haenszel chi-square analysis to compare periods of preschool teacher education and respondents’ understanding of participatory observation. The statistical significance level was set at α = 0.001, and analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25.

3. Results

A total of 1311 respondents participated in the survey, yielding a response rate of 39.9%. The response rate for each profession is as follows: managers (40.6%), in-service teachers (35.8%), and pedagogy teachers (70.2%). Table shows the characteristics of the respondents. In the sample, 91.4% were female, 44.3% managers, 45.5% in-service teachers, and 10.2% pedagogy teachers.

Table 2. Characteristics of the study sample organized by profession from a national Norwegian survey on observation as a professional tool in kindergartens and kindergarten teacher education from 2018

3.1. Observation as a tool in professional work

Among the respondents, 87.9% answered that observation was a completely necessary tool in their professional work. Only 1.9% regarded observation as completely unnecessary. There were no differences between professions (manager, in-service teacher, and pedagogy teacher) in their assessment of observation as a tool in the professional work. There were also no differences in their assessment of observation and the time period of preschool teacher education.

3.2. Participatory observation

From the respondents, 45.2% considered participatory observation as written or mostly written observation; in other words, they understood it as a form of formal observation (Table ). Differences were revealed between the professions in terms of their understanding of participatory observation. Among in-service teachers, 62.2% mostly understood participatory observation as a non-written form of observation; in other words, they understood it as to be present and see. Approximately half (49.7%) of the managers and a slightly lower number of the pedagogy teachers (43.9%) perceived participatory observation as an unwritten or usually unwritten observation.

Table 3. Understanding of participatory observation by profession and year of preschool teacher education. Data from a national Norwegian survey on observation as a professional tool in kindergartens and kindergarten teacher education, 2018

Analyses of the association between the period of preschool teacher education and respondents’ understanding of participatory observation showed a gradual increase in their perception of observation as an unwritten method as it relates to education today (Table ).

3.3. Relevant observation methods in KTE

Table shows the number of respondents who regarded the various observation methods as “relevant” in KTE. Differences emerged between professions in the following methods: logging, ongoing protocol, photo documentation, sociogram, TRAS, and time sampling. The pedagogy teachers regarded the methods as more important than the managers and in-service teachers, except for TRAS. Of the pedagogy teachers, 35% assessed TRAS as relevant, while 53.7% of the managers and 46.9% of the in-service teachers regarded this method as relevant.

Table 4. Relevant observation methods in kindergarten teacher education. Number and frequency of persons responding “relevant” by profession. Data from a national Norwegian survey on observation as a professional tool in kindergartens and kindergarten teacher education from 2018

3.4. Suitable observation methods in kindergarten

All observation methods except for time sampling and rating scales were assessed as suitable for use in kindergartens (Table ). Differences emerged between the professions in terms of how they assessed the following methods: logging, video observation, TRAS, sociogram, and time sampling. Those in the praxis field (managers and in-service teachers) assessed TRAS as more relevant than the pedagogy teachers. Fewer in-service teachers saw sociogram as a relevant method in kindergartens, compared to managers and pedagogy teachers. Of the in-service teachers, 22.9% answered “do not know” when asked if sociogram was relevant. Nearly half of the respondents did not know if rating scales and time sampling were relevant in kindergartens.

Table 5. Suitable observation methods in kindergarten. Number and frequency of persons responding “well or very well suitable,” by profession. Data from a national Norwegian survey on observation as a professional tool in kindergartens and kindergarten teacher education from 2018

Sociogram was the only method that was assessed differently depending on the period of preschool teacher education (p < 0.001). Of those educated in 1980 or before, 82.5% regarded sociogram as suitable or well suitable, while 75.9%, 57.5%, and 49.6% of those educated during 1990, 2000, and 2010 or later, respectively, considered it a relevant method.

3.5. Most important observation method

The question regarding which observation method is the most important with respect to safeguarding “Children’s participation,” “Change and develop praxis,” “Children who struggle,” and “Play and well-being” showed that participatory observation was regarded as the most important method for safeguarding “Children’s participation,” “Children who struggle,” and “Play and well-being” (56.1%, 41.3%, and 51.9%, respectively). The method “stories from practice” was seen as the most important (47.8%) for “Change and develop praxis.”

3.6. Use of observation during the last six months

Stories from practice, participatory observation, and TRAS were the methods reported as the most frequently used during the last six months (80.8%, 78.8%, and 55.2%, respectively). Among the commercial tools for observation, The Incredible Years (7.3%), Marte Meo (6.2%), and MIO (2.8%) were used to a lesser extent (<8%), barring TRAS (55.2%) and ALLIN (36.9%).

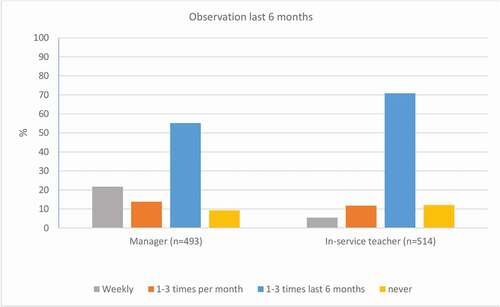

Differences between managers and in-service teachers emerged in terms of how often they had time to perform observations (p < 0.001). Observation was reportedly carried out 1–3 times during the previous six months by 55.2% of the managers and 70.8% of the in-service teachers (Figure ).

3.7. Focus of observations within the last six months

Differences emerged between professions in terms of the focus selected for observation within the last six months (p < 0.001, Table ). In the praxis field, the most frequent focus of observation was the interaction between the children (managers 28.0% and in-service teachers 39.6%). Pedagogy teachers answered that the interaction between adults and children was most often selected as the focus (21.4%), while only 4.7% of the in-service teachers reported this as their focus. Respondents from all the professions answered that children’s learning was focused on the least. Furthermore, in the praxis field, formative development was not often reported as the focus for observations within the last six months (1.7% of managers and 1.9% of in-service teachers), while 19.4% of pedagogy teachers reported it as the focus.

Table 6. Focus in observations (within the last sixmonths) by profession. Sample from a national Norwegian survey on observation as a professional tool in kindergartens and kindergarten teacher education from 2018

3.8. Reasons for observation and written observation

The perception of “Learning about children’s perspectives and participating” as an important or very important reason for performing observation differed by profession (33.9% of the managers, 43.9% of the in-service teachers, and 26% of the pedagogy teachers, p < 0.001). There were no differences between professions in their perception of the other reasons: “Knowledge of children’s development,” “Worry for a child,” “Preparation for parent-teacher conference,” “Didactic work,” “Development of praxis,” “Cooperation with other institutions (educational-psychological service, child welfare services),” and “To maintain awareness of bullying or exclusion.” Of the respondents, 96.6–99.8% reported these reasons as important or very important for observation. There were no differences between the time period of teacher education and perceptions regarding the importance of various reasons for observation.

Furthermore, in managers’ and in-service teachers’ responses regarding the importance of written observations for the reasons mentioned above, in addition to “Children’s well-being,” most (99.6%) regarded written observation as important or very important for worry for the children and cooperation with other institutions; 85.4–98.4% reported it as important or very important for the other reasons mentioned.

3.9. Collective reflections based on written observations in kindergarten

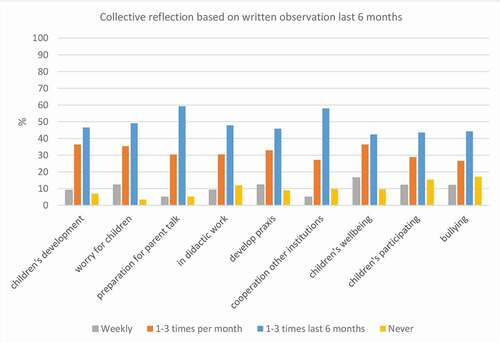

Collective reflections based on written observations carried out for different reasons were most frequently reported as performed 1–3 times within the last six months (Figure ). Furthermore, 12–16.6% of the respondents from the praxis field reported weekly collective reflections based on written observations in the last six months due to worry for children, the development of praxis, assessment of children’s well-being, obtaining knowledge about children’s participation, and awareness of bullying.

4. Discussion

The observation methods assessed for relevance in KTE and suitability in kindergartens are those described in the most commonly used methodology book in KTE in Norway and commercial tools for observation (Åbro, Citation2016). Nearly all respondents assessed participatory observation and stories from practice as relevant methods for both KTE and in kindergartens, while few assessed time sampling and rating scales as relevant. Participatory observation and stories from practice were also reported as the methods used most frequently within the last six months; the commercial tools for observation, barring TRAS and ALLIN, were used infrequently. Although observation was regarded as important as a tool in professional work, most respondents had carried out observations only 1–3 times within the last six months. The main focus in the observational work performed by managers and in-service teachers was the interaction between children; meanwhile, for pedagogy teachers, the interaction between adults and the children was the main focus. Children’s learning was the most infrequent focus for managers, in-service teachers, and pedagogy teachers.

Overall, the results reveal that respondents from all the three professions perceive observation as a necessary tool in professional work, the importance of which is also highlighted in the policy documents for KTE and kindergartens (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2017; Norwegian University Council, Citation2018). Stories from practice was seen as the most important method for changing and developing pedagogical practice and nearly all respondents regarded participatory observation and stories from practice as relevant methods for both KTE and in kindergartens; no differences were found between professions in this regard. However, there were differences between professions in how they understood participatory observation. These results indicate a reduction over recent decades in the understanding of participatory observation as a formal written observation. Although participatory observation was regarded as a relevant method for KTE and kindergartens, we must consider the fact that it was not necessarily defined as a method in the KTE curriculum, based on observation as a threefold process (Løkken & Søbstad, Citation2013).

Our results are in line with those of previous studies, which showed that in-service teachers considered stories from practice as the method most relevant to the profession (Birkeland & Ødegaard, Citation2018), and that participatory observation, stories from practice, and ongoing protocol were emphasized in KTE (Birkeland, Citation2018, Citation2019). Our study also shows that pedagogy teachers more frequently reported ongoing protocol as a relevant method in KTE, compared to managers and in-service teachers. With respect to the methods showing differences between the professions, pedagogy teachers generally regarded them as more relevant than participants from kindergartens (managers and in-service teachers); the exception was TRAS, for which the opposite result was found. Only 35.0% of pedagogy teachers regarded TRAS as relevant in KTE. Despite the criticism for it (Pettersvold & Østrem, Citation2012; Vik, Citation2017), previous research has shown that commercial tools such as TRAS have been widely used in kindergartens (Engel et al., Citation2015; Haugset et al., Citation2015; Sandvik et al., Citation2014; Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2016); on the other hand, previous research has also shown that pedagogy teachers have been critical of TRAS (Birkeland, Citation2018).

It also appears that rating scales and time sampling are seen as having little relevance for both KTE and kindergartens. This might raise the questions whether these methods should be part of the preparatory education for kindergarten teachers, and why they are perceived as having little relevance in the first place. Birkeland (Citation2018, Citation2019) showed that sociometry and digital tools are not heavily emphasized in KTE; in our study, about 20%in-service teachers did not know whether sociometry was relevant. It also appears that sociometry was regarded as less relevant by those educated in recent years, compared to those educated longer ago, which could indicate that sociometry is less emphasized in KTE today. Digital tools, such as video observation and photo documentation were regarded as relevant methods for use in the kindergarten and in KTE. In profession-oriented and coherent education (Canrinus et al., Citation2017), emphasis on relevant methods is crucial. Overall, the answers regarding methods relevant to KTE and the profession are in accordance, which provides appropriate direction to educational institutions. However, it is also important to consider whether these methods promote an understanding of children as participants in a particular context, as highlighted by several scholars (i.e., Clark, Citation2006; Elfstöm, Citation2013; Fleer & Hedegaard, Citation2010; Garvis et al., Citation2015; Hedegaard, Citation2019; Samuelsson, Citation2010).

Our study reveals observation as an important practice for different reasons, including concern for children, maintaining awareness of bullying, cooperating with other institutions (educational-psychological service and child welfare services), developing praxis, obtaining knowledge of children’s development, preparing for parent-teacher conferences, and as part of didactic work; however, it also shows that in terms of learning about children’s perspectives and participation, only 33.9% managers, 43.9% in-service teachers, and 26% pedagogy teachers consider observation as important or very important. This could indicate that learning about children’s perspectives and participation is less emphasized in the observational work, as also found by Birkeland and Ødegaard (Citation2018). Furthermore, our findings show that respondents consider written observations for the reasons mentioned as important or very important, especially those regarding concern for the children and cooperating with other institutions; this, too, corresponds with the results of Birkeland and Ødegaard (Citation2018).

The main focus of observation in the praxis field (managers and in-service teachers) is the interaction between the children. Pedagogy teachers reported interactions between adults and children as the main focus, while few of the in-service teachers reported it as such. Surprisingly, children’s learning, despite being highlighted in the curricula of both KTE and kindergartens (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2017; Norwegian University Council, Citation2018), has received the least attention from respondents of all three professions—only 0.8% reported it as a focus in observations the last six months. The results also reveal that formative development, which has been an overarching goal in the Kindergarten Act and the framework plan for Norwegian kindergartens since 2011, is not a significant focus for those in the praxis field—only 1.7% managers and 1.9% in-service teachers reported this as a focus in observations carried out the last six months; in addition, children’s participation, which is statutory in Norway, is one of the reasons that got the least consideration for carrying out observations within the last six months. We find these results disturbing, considering that policy documents in Norway highlight children’s participation and learning, as well as their formative development. Our results are in line with those of Birkeland and Ødegaard (Citation2018), who showed that the main focus in observational work carried out in kindergartens was the interaction between the children, and not children’s participation. In addition, according to Kallestad and Ødegaard (Citation2013), the importance of focusing on adults seems to be a blind spot in the observation carried out in kindergartens. This result corresponds to those of studies in other countries (i.e. Buldu, Citation2010; Emilson & Samuelsson, Citation2012; Lewis et al., Citation2019), thus highlighting the importance of educators’ awareness of their role and contribution to children’s learning processes, and the understanding that children’s development, learning, and formative development are intertwined with institutional practices (Hedegaard, Citation2019). As our study shows, only 4.7% in-service teachers reported the interaction between the adult and the children as a focus in observational work in kindergartens, which several scholars (i.e., Elfstöm, Citation2013; Hedegaard, Citation2012; Samuelsson, Citation2010) have highlighted as crucial for transcending the developmental psychology paradigm.

Play and a holistic approach to learning have been at the forefront in Nordic countries, and early childhood teacher preparation has been developed according to this tradition (Einarsdottir, Citation2013); however, our study finds only 9.3% of respondents reporting play as the most frequent focus in the observational work carried out within the last six months. Participatory observation was reported as the most important method for observing play and children’s well-being.

Moreover, despite the perception of observation as important, most respondents carried out observations only 1–3 times the last six months; also, written observations are important, and yet, collective reflections based on written observations were infrequent. Previous research, too, has shown written observations to be infrequent (Børhaug et al., Citation2018), informal observation at the forefront in kindergartens, and collective reflection based on written observations less apparent (Birkeland & Ødegaard, Citation2018). This is not aligned with the importance of written observations and collective reflections, which have been highlighted by scholars as crucial (Birkeland, Citation2019; Bruce et al., Citation2015; Dalli, Citation2008; Eik et al., Citation2016; Korthagen, Citation2016; Salo & Rönnerman, Citation2013; Sheridan et al., Citation2011) and necessary based on observation as a threefold process (Løkken & Søbstad, Citation2013). Visual or written records acquire meaning as the basis for individual and collective reflections and a validation of one’s own interpretations when compared to those of others. A question then may arise, whether teachers in preschools truly employ observation as a method.

5. Strengths and limitations

This study is based on a national survey comprising all kindergarten educational sites in Norway, and to the best of our knowledge, is the largest study on observation in KTE and kindergartens. However, the response rate is low (39.9%) and could have introduced a response bias if the respondents were especially motivated or displayed a more favorable attitude toward observation as a professional tool than non-respondents. We have no information regarding non-respondents, but pedagogy teachers evinced a higher response rate (70.2%) and might evaluate the relevance of observation more highly than those of other professions. However, pedagogy teachers evaluated the relevance of different observational methods both higher and lower compared to the other professions. The estimate regarding the frequency with which observation was used and collective reflections were conducted within the last six months, is only measured among managers and in-service teachers, and may be too high. A statistical significance level of 0.001 was applied to reduce the risk of significant results by chance.

The authors have developed the questionnaire based on the results of previous research. A test panel evaluated the questionnaire and the feedback resulted in only minor adjustments. The wording in the questionnaire was similar to both KTE and kindergarten curricula to avoid misunderstanding; however, its validation could not be advanced, so the results must be interpreted with caution.

After the survey was distributed, we became aware, given the existing concerns regarding the relevance of various methods in KTE, of the fact that the different methods were not accurately presented. The commercial tools Marte Meo and The Incredible Years were combined and corresponded to ALLIN and MIO. These methods are different but could not be analyzed separately. In terms of use, all methods were singular and should, therefore, be included.

6. Conclusion

The present study contributes knowledge regarding observation in KTE and kindergartens based on a sample from Norway and explores the relevance of different methods used in observation. It shows that all methods except for time sampling and rating scales were regarded as relevant for KTE and kindergartens—for the majority, it was participatory observation and narrative methodology (stories from practice). Observation was assessed as an important tool in professional work. Nevertheless, most participants reported that they only had time to carry out observations 1–3 times within the last six months in their kindergarten. However, the results must be interpreted with caution due to a low response rate and the use of a non-validated questionnaire. Increasing opportunities to carry out observation as a method is important, to ensure that all children are provided for in accordance with the Kindergarten Act and the current framework plan, and also to further develop pedagogical practice. For students learning about observation in KTE, the importance of role models also appears to be a challenge when observations are informal and infrequent. The conditions under which pre-service teachers perform observations in the kindergarten context should be of interest for future research. Our question does not investigate the respondents’ ethical considerations regarding the observation, and further research should, therefore, focus on it, especially with respect to photo and video observation. Our study shows children’s learning, formative development, and participation as areas least focused on in observational work, which, according to us, is disturbing, considering the goals and values established in policy documents for KTE and kindergartens.

Data availability

The data set collected and used for this study is available http://dx.doi.org/10.18712/NSD-NSD2746-V2

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Johanna Birkeland

Johanna Birkeland is a postdoctoral fellow at KINDKNOW-Kindergarten Knowledge Centre for Systemic Research on Diversity and Sustainable Futures https://www.hvl.no/en/abou/kindergarten-knowledge-centre/. The article was written when she still was a Ph.D student at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research addresses the coherence between the perception of observation in on-campus kindergarten teacher education and that of in-service training. The research reported in this paper is the final work on her Ph.D. project. The co-authors were her doctoral advisors.

Valborg Baste

Valborg Baste is a researcher and statistician at NORCE Norwegian Research Centre and an associate professor at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research mainly focuses on the use of health registries, epidemiology, and biostatistics.

Elin Eriksen Ødegaard

Elin Eriksen Ødegaard, is the director of KINDKNOW – Kindergarten Knowledge Centre for Systemic Research on Diversity and Sustainable Futures at Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. She is also a visiting professor at UiT – The Arctic University of Norway. Her research interests are Early Childhood Education, Teacher Education, and Visual and Narrative Methodology.

Notes

1. This is referred to as pre-service in some contexts.

2. The observer participates with the children and creates the record directly following the observation.

3. A notebook in which the staff records situations or a child’s activities over time.

4. Visually observing, i.e. every hour, to check (record) the status or activities of a child or a physical area within the kindergarten.

5. A rating scale used to evaluate the quality, frequency, or ease with which a child uses a certain skill.

6. A chart plotting the structure of interpersonal relations in a group situation.

7. TRAS is a tool used in the early chronicling of children’s language development.

8. Alle Med [ALLIN] is a tool used to observe social skills

9. The Incredible Years is a program to reduce behavior problems.

10. MIO is an observation material used in the observation of children’s mathematical development.

11. The highest level was chosen as the current one.

References

- Åbro, C. (2016). Konsepter i pædagogisk arbejde [Concepts in pedagogical work]. Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Alasuutari, M., Markström, A.-M., & Vallberg Roth, A.-C. (2014). Assessment and documentation in early childhood education. Routledge.

- Basford, J., & Bath, C. (2014). Playing the assessment game: An English early childhood education perspective. Early Years, 34(2), 119–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2014.903386

- Birkeland, J. (2018). “Å lære et håndverk”: Pedagogikklæreres perspektiver på observasjon i barnehagelæreutdanningen [“Learning a craft”: Pedagogy teachers’ perspectives on observation in early childhood teacher education]. Nordic Journal of Pedagogy and Critique, 4, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.23865/ntpk.v4.1315

- Birkeland, J. (2019). Observation – A part of kindergarten teachers’ professional skill set. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 7 (3A), 50–59. In A.R. Sadownik, W. Aasen, & A. Visnjic Jevtic (Eds.), Special edition on introducing students to the profession of kindergarten teacher - insights from Norway. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2019.071306

- Birkeland, J., & Ødegaard, E. E. (2018). Under lupen – Praksislæreres observasjonspraksis i barnehagen [Under the magnifying glass – Practice teachers’ observation practice in kindergarten]. Journal of Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 17(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.2160

- Birkeland, J., & Ødegaard, E. E. (2019). Hva er verdt å vite om observasjon i dagens barnehage [What is worth knowing about observation in today’s kindergarten?]. Norwegian Pedagogical Journal, 103(2–3), 108–120. https://doi-org.galanga.hvl.no/10.18261/.1504-2987-2019-02-03-08

- Bjerkestrand, M., Fiske, J., Hernes, L., Pramling Samuelsson, I., Sand, S., Simonsen, B., Stenersen, B., Storjord, M. H. & Ullmann, R. (2015). Barnehagelærerutdanninga. Meir samanheng, betre heilskap, klarare profesjonsretting? Følgegruppen for barnehagelærerutdanningen (KTE. More consistency, better overview, clearer professional direction? Group for follow-through in kindergarten teacher training), Report no. 2, Høgskolen i Bergen, Norway.

- Blair, J., Czaja, R. F., & Blair, E. A. (2014). Designing surveys: A guide to decisions and procedures. SAGE.

- Børhaug, K., Brennås, H. B., Fimreite, H., Havnes, A., Hornslien, Ø., Moen, K. H., & Bøe, M. (2018). Barnehagelærerrollen i et profesjonsperspektiv – Et kunnskapsgrunnlag [The kindergarten teacher role in a professional perspective – A knowledge base]. Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research.

- Broadhead, P. (2005). Developing an understanding of young children’s learning through play: The place of observation, interaction and reflection. British Educational Research Journal, 32(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920600568976

- Bruce, T., Louis, S., & McCall, G. (2015). Observing young children. Sage.

- Buldu, M. (2010). Making learning visible in kindergarten classrooms: Pedagogical documentation as a formative assessment technique. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(7), 1439–1449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.05.003

- Canrinus, E. T., Klette, K., & Hammerness, K. (2017). Diversity in coherence: Strengths and opportunities of three programs. Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0022487117737305

- Clark, A. (2006). Listening to and involving young children: A review of research and practice. Early Child Development and Care, 175(6), 489–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430500131288

- Clark, A., Kjørholt, A., Moss, T., & Moss, P. (Eds.). (2005). Beyond listening: Children’s perspectives on early childhood services. Policy Press.

- Dalli, C. (2008). Pedagogy, knowledge and collaboration: Towards a ground-up perspective on professionalism. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 16(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930802141600

- Eik, L. T., Steinnes, G., & Ødegård, E. (2016). Barnehagelærerens profesjonslæring [Kindergarten teacher’s professional learning]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Einarsdottir, J. (2013). Early childhood teacher education in the Nordic countries. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21(3), 307–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2013.814321

- Elfstöm, I. (2013). Uppföljning och utvärdering för förändring. Pedagogisk documentation som grund för kontinuerlig verksamhetsutveckling och systematiskt kvalitetsarbete i förskolan [Monitoring and evaluation for change. Pedagogical documentation as a basis for continuous work development and systematic quality work in pre-school] [Doctoral thesis]. Stockholms Universitet, Sweden.

- Emilson, A., & Samuelsson, I. P. (2012). Looking for the competent child. Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 5(21), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.476

- Engel, A., Barnett, W. S., Anders, Y., & Taguma, M. (2015). Early childhood education and care policy review: Norway. OECD.

- Fleer, M. (2011). Sociocultural assessment in early years education – Myth or reality? International Journal of Early Years Education, 10(2), 105–120. https://doi-org.galanga.hvl.no/10.1080/09669760220141999

- Fleer, M., & Hedegaard, M. (2010). Children’s development as participation in everyday practices across different institutions. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 17(2), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749030802477374

- Fleet, A., & Harcourt, D. (2018). (Co)-researching with children. In M. Fleer & B. van Oers (Eds.), International handbook of early childhood education ,165-201. Springer.

- Franck, K., & Nilsen, R. D. (2015). The (in)competent child: Subject positions of deviance in Norwegian day-care centres. Early Childhood, 16(3), 230–240. doi:10.1177/1463949115600023

- Frønes, M. H. (2017). Observasjonens betydning i den profesjonelle praksis [The importance of observation in the professional practice]. Journal of Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 14(9), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.1984

- Garvis, S., Ødegaard, E. E., & Lemon, N. (2015). Beyond observation –Narratives and young children. Sense Publishers.

- Grindheim, L. T. (2017). Anger and conflicts in early childhood education: expressing worries about early intervention through the incredible years programs. In J. C. A. Fernando & S. R. M. Costa (Eds.), Anger and anxiety: Predictors, coping strategies, and health effects (pp. 217–238). Nova Science Publishers.

- Gulbrandsen, L., & Eliassen, E. (2013). Kvalitet i barnehager [Quality in kindergartens] (NOVA Report 1/2013). NOVA - Norwegian Social Research. http://www.nova.no/asset/6157/1/6157_1.pdf

- Haugset, A. S., Nilsen, R. D., & Haugum, M. (2015). Spørsmål til Barnehage-Norge2015 [Questions for kindergartens in Norway 2015] (Report 19/2015). Trøndelag Research and development AS. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/tall-og-forskning/forskningsrapporter/sporsmal-til-barnehage-norge-2015.pdf

- Hedegaard, M. (2012). Analyzing children’s learning and development in everyday settings from a cultural-historical wholeness approach. Mind, Culture and, Activity, 19(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2012.665560

- Hedegaard, M. (2019). Children’s perspectives and institutional practices as keys in a wholeness approach to children’s social situations of development. In A. Edwards, M. Fleer, & L. Bøttcher (Eds.), Cultural-historical approaches to studying learning and development. Perspectives in cultural-historical research (Vol. 6, pp. 23–41). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6826-4_2

- Kallestad, J. H., & Ødegaard, E. E. (2013). Children`s activities in Norwegian kindergartens part 1: An overall picture. Cultural-Historical Psychology, 9(4), 74–82. https://doi.org/10.17759/chp

- Karila, K., Kinos, J., Niiranen, P., & Virtanen, J. (2007). Curricula of Finnish kindergarten teacher education: Interpretations of early childhood education, professional competencies and educational theory. European Early Childhood Research Journal, 13(2), 133-145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930585209721

- Knauf, H. (2019). Documentation strategies: Pedagogical documentation from the perspective of early childhood teachers in New Zealand and Germany. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48, 11-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-019-00979-9

- Korthagen, F. A. J. (2016). Pedagogy and teacher education. In J. Loughran & M. L. Hamilton (Eds.), International handbook of teacher education (Vol. 1, pp. 311–346). Springer.

- Lewis, R., Fleer, M., & Hammer, M. (2019). Intentional teaching: Can early-childhood educators create the conditions for children’s conceptual development when following a child-centered programme? Australasian Journal of Early Childhood,44(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119841470

- Lillejord, S., & Børte, K. (2017). Lærerutdanning som profesjonsutdanning – Forutsetninger og prinsipper fra forskning [Teacher education as professional education – Prerequisites and principles from research]. Knowledge Center for Education.

- Løkken, G., & Søbstad, F. (2013). Observasjon og intervju i barnehagen [Observation and interview in kindergarten]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Lyngseth, E. J. (2010). Forebyggende muligheter ved dynamisk språkkartlegging med TRAS- observasjoner i barnehagen [Preventive possibilities for dynamic language mapping with TRAS observations in the kindergarten]. Journal of Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 3(3), 219-225. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.292

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2016). Barnehagespeilet 2016 [The mirror of kindergartens 2016]. Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/tall-og-forskning/rapporter/barnehagespeilet/udir_barnehagespeilet_2016.pdf

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2017). Framework plan for kindergartens. Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf

- Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. (2012a). Framework plan regulations for kindergarten teacher education. The Ministry of Education and Research. https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/rundskriv/2012/forskrift_rammeplan_barnehagelaererutdanning.pdf

- Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. (2012b). National guidelines for kindergarten teacher education.. The Ministry of Education and Research. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/rundskriv/2012/nasjonale_retningslinjer_barnehagelaererutdanning.pdf

- Norwegian University Council. (2018). National guidelines for the kindergarten teacher education. Norwegian University Council. https://www.uhr.no/_f/p1/i8dd41933-bff1-433c-a82c-2110165de29d/blu-nasjonale-retningslinjer-ferdig-godkjent.pdf

- Oberhuemer, P. (2015). Seeking new cultures of cooperation: A crossnational analysis of workplace-based learning and mentoring practices in early years professional education/training. Early Years, 35(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2015.1028218

- Otterstad, A. M., & Nordbrønd, B. (2015). Posthumanisme/nymaterialisme og nomadisme – Affektive brytninger av barnehagens observasjonspraksiser [Posthumanism/New materialism and nomadism – Affective breakup of the kindergarten’s observation practices]. Journal of Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 11(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.1214

- Pettersvold, M., & Østrem, S. (2012). Mestrer, mestrer ikke. Jakten på det normale barnet [Competent, or not competent. The pursuit of the normal child]. Res Publica.

- Picchio, M., Giovanni, D., Mayer, S., & Musatti, T. (2012). Documentation and analyses of children’s experiences: An ongoing collegial activity for early childhood professionals. Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development, 32(2), 159–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2011.651444

- Podmore, V. N., & Luff, P. (2012). Observation. Origins and approaches in early childhood. Mc Graw Hill Open University Press.

- Salo, P. J., & Rönnerman, K. (2013). Teachers’ professional development as enabling and constraining dialogue and meaning-making in education for all. Professional Development in Education, 39(4), 596–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2013.796298

- Samuelsson, I. P. (2010). Ska barns kunnskapar testas eller deras kunnande utvecklas i förskolan [Should children’s knowledge be tested or their skills developed in preschool?]. Journal of Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 3(3), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.284

- Sandvik, M., Garmann, N. G., & Tkachenko, E. (2014). Synteserapport om skandinavisk forskning på barns språk og språkmiljø i barnehagen [Scandinavian report of research in children’s language and language environment in the kindergarten]. Høgskolen i Oslo og Akershus. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/tall-og-forskning/forskningsrapporter/synteserapport-om-sprak-og-sprakmiljo.pdf

- Seland, M. (2017). Uenig eller ulydig [Disagree or disobedient?]. In M. Øksnes & M. Samuelsson (Eds.), Motstand [Resistance] (pp. 90–114). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Sheridan, S., Williams, P., Sandberg, A., & Vuorinen, T. (2011). Preschool teaching in Sweden – A profession in change. Educational Research, 53(4), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2011.625153

- Sjølie, E. (2017). Learning educational theory in teacher education. In K. Mahon, S. Francisco, & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Exploring education and professional practice through the lens of practice architectures (pp. 49–61). Springer Nature.

- Ulla, B. (2014). Auget som arrangement – Om blikk, makt og skjønn i profesjonsutøvinga til barnehagelæraren [The eye as an arrangement – About the look, power, and discretion of the professions of kindergarten teachers]. Journal of Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 8(5), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.774

- Vik, N. E. (2017). Språkkartlegging av flerspråklige barn i barnehagen – Fra kontrovers til kompromiss [Language mapping of multilingual children in kindergarten – From controversy to compromise]? Journal of Nordic Early Childhood Education Research, 14(10), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.7577/nbf.1734