Abstract

This paper reports on factors affecting the working lives of practitioners in health and education in the UK. The context is the increasing evidence of low recruitment, low retention rates and a high incidence of stress amongst expert practitioners in these two public institutions. Similar patterns of practitioner response indicate the systemic nature of the problems besetting these two public institutions. What emerges from the data is a cross-sector phenomenon identified here as a “cry for professional intimacy”, formed as these practitioners give voice to a strong desire to be allowed to refocus on the relational aspects of their work.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper reports on factors affecting the working lives of practitioners in health and education, with a particular focus on the UK experience. It is positioned in the context of the increasing evidence of low recruitment, low retention rates and a high incidence of stress amongst expert practitioners in these two public institutions. It provides a stark view of how professional autonomy has been reduced and the extent to which practitioners at all levels within the health and education service have become technicians of policy. Our common understanding of the importance of “the eco-system of constant human interaction” has been brought to light by our recent experience of the coronavirus pandemic lockdown. The need for a restoration of professional intimacy has become an even greater priority—hence the relevance of this paper.

Cogent 198,774,848

1. Introduction

The surveillance required by the micro-monitoring of public servants such as teachers, nurses, lecturers and doctors through the application of the principles of new public management (NPM) and the increased stress related illness amongst these practitioners, has echoes of Jeremy Bentham’s failed 19th panopticon experiment (Zuboff, Citation1988, Citation2019). Bentham’s prison design offered complete surveillance at very little cost. From the guard tower, a guard could see into every cell, but inmates could not see into the tower; inmates never knew whether or not they were being watched. Eventually the system was abandoned due to an increase in mental illness amongst prisoners.

Of course, unlike those 19th century prisoners, today’s public servants are free to leave or indeed, free never to enter, and this they are doing—retention and recruitment figures in our public services of health and education have never been worse (Nuffield Trust, Citation2016; UCAS, Citation2015).

Throughout this article we use the phrase “expert practitioner” to identify our particular target population, members of the Health and Education workforce who have four or more years of certificated, professional training in their specific area of expertise. Pay and conditions are the most commonly used measures to assess the attractiveness of a job (Jawahar & Stone, Citation2011; Till & Karren, Citation2011), and for this highly qualified employment group, pay has substantially increased over the last ten years. Expert practitioners in health (doctors and nurses), and those employed in education (teachers and university lecturers) (Buchan et al., Citation2008; OECD, Citation2014, Citation2015a, Citation2015b) have had real term increases in pay, yet we continue to have a crisis of staffing both in recruitment and in retention in both these areas (HC, Citation2016: Section17:9; Parkin & Powell, Citation2016; RCN, Citation2015. Frontline First Report. (b), 2015). We continue to have a workforce in these industries which is manifesting more stress and stress-related absence than other sectors of employment (Bailey, Citation2013; Black, Citation2008). It would appear that the conditions of the employment for our expert practitioners in health and education have altered so much that these well-paid, respected professional roles are no longer attractive and are, actually, for some workers, toxic (DfE and the National College for School Leadership, Citation2015; Keogh, Citation2013; Nuffield Trust, Citation2016).

1.1. Socio-political context

Throughout the first part of the 21st century succeeding governments in the UK have embraced the concept of the “free market” as a solution to the spiralling costs of public services (Harvey, Citation2007). New Public Management (NPM) a hybrid set of practices, combining neoliberal market templates with business control systems that emphasize audit and accountability is the organizational platform which has supported this policy direction (Marginson, Citation2013; Verger et al., Citation2019). The pervasion of a “market mentality” (Lacher, Citation1999) into public service provision can be seen in the Education Reform Act of 1988, and in the more recent Academies Act (Department for Education, Citation1988; DfE, Citation2010a). The same shift to a market mentality is apparent in the health sector, manifested in the out-sourcing of service provision enabled by the Health and Social Care Act of 2012 (Department of Health, Citation2012a). As early as 1978, Attili argued that, as capitalism ages and the need for the material products which drove the industrial “Fordist” age diminishes, consumers will develop needs for “services”, their attention switching from the “private consumption” of cars, housing, electrical goods and so on to the “collective consumption” of health and knowledge; he also described how the growth of these new needs would be assiduously nurtured by private providers, often large multinational conglomerates, ensuring that capitalist accumulation continues to function. In the 21st century Harvey states that the primary aim of the neoliberal project is to open up new fields for capital accumulation in domains, such as health and education, which were formerly regarded off-limits to the calculus of profitability (Harvey, Citation2007).

1.2 Profiling the practitioner

In both health and education, practitioners report a deep sense of unease at the increasing application of business practice to their work. This unease is most apparent when the formation of relationships between practitioners and their clients is disturbed. This can be seen in the commentary of GP participants in Solomon’s (Citation2009) study of prescribing where the computer-based data gathering process, carried out to aid fiscal control, had the unintended consequence of deleteriously altering the dynamic of the consultative meeting:

GPs commented that the introduction of the QOF (Quality and Outcomes Framework) had increased paperwork and their use of computers. They reported that looking at the computer during consultations created a communication barrier with the patient. Some GPs reported that patients became resentful and that trust was damaged if they suspected that the GP was driven by guidelines, rather than what was in their own best interest. (Solomon, Citation2009, p. 5)

There is now a third party or presence in the room. This presence is the policy-maker who is assiduously conducting the application of business practice to public service; government guidelines, protocols and targets are present as the patient and practitioner speak. This is a new dynamic which is also familiar in education (Ball, Citation2012; Greany & Higham, Citation2018; Molnar, Citation2006). These practitioners, both in health and education, are concerned with the loss of autonomy that this causes. This micro-monitoring leads to a lack of professional intimacy—how can two people speak honestly and unselfconsciously when a judgmental and controlling third party is present?

The ideology of this New Public Management sits uncomfortably with the knowledge-laden, autonomous nature of the work of “healing” and “teaching”, which, it can be argued, has to be understood both in relation to a public professional identity and the more intimate concept of relational expertise (Edwards, Citation2010). Although recognising the shifting nature of that identity, Edwards states that the knowledge-laden nature of specialist professional practices has to be understood in relation to professional identity and the idea of relational expertise (Edwards, Citation2010). Wilensky (Citation1964) and Evetts (Citation2003) also emphasise the particular combination of higher level skills and acceptance of moral obligation which define the “expert practitioner” and which underpin the criteria for entry into professional bodies such as the British Medical Association, the Royal College of Nursing and the General Teaching Council for Scotland. We further propose that at the core of this role lies a dynamic phenomenon; the combination of specialist knowledge, moral positioning and relational capacity which we describe as the enacting of “professional intimacy”. In their working lives, at the point of interaction with a client, these practitioners inhabit the role of doctor, nurse or teacher—roles which emphasize relationships over structures, and demonstrate an orientation to work where “the needs and demands of patients, clients, students and children are paramount” (Evetts, Citation2003:252).

Evidence suggests that these practitioners can only exercise their knowledge and skills successfully when they are free to create professionally intimate relationships with both colleagues and clients. Kelchtermans (Citation2005) writes that more than any other profession, apart from medicine, teachers’ thoughtful actions reflect emotional involvement and moral judgement, and that their emotional reactions to their work are intimately connected to the view they have of themselves and others. Kelchtermans’ use of the word “intimate” here implies the profound effect that performing the role of teacher or healer has on the psyche of the individual enacting that performance. His language depicts what has been described as the “holistic,” all- pervading nature of the roles of the “teacher” and “healer”. Expert practitioners in health and education, teachers, doctors, nurses, and lecturers, cannot separate themselves from the emotional experiences of their work (Kelchtermans, Citation2005).

Intimate, real behaviour, or display of natural emotions, is present when the feelings engendered by the moral perceptions of the role of teacher, doctor or nurse are commensurate with the feelings engaged during the moments of that interaction and from this arises professional intimacy. The transaction between a health or education practitioner and their client is essentially an emotional one, not a financial one. As indicated in the introduction, this report is positioned in the context of the increasing distress amongst health and education practitioners. Klechterman’s category of practitioner work-role behaviour, that of “intimate behaviour”, can offer an explanation of this distress, as it explains the practitioner’s struggle to convert the anger, boredom or fear caused by a hostile, micro-monitored business-led work environment (engendering feelings which he/she feels to be incompatible with the role of teacher or healer) into the morally acceptable natural emotions of this intimate behavior (Kelchtermans, Citation2005).

There is evidence that the over-zealous application of the contingencies of the business model to these professions tends to devalue the role of the emotional experience and skills of practitioners. For the business model of public services has, at its core, a dichotomy which is implied in Marginson’s comments on the “ubiquitous” international application of NPM, with its inherent clash of market-led action and high levels of practitioner audit (Marginson, Citation2013). It is difficult for practitioners to pay attention to the fine-tuning of the interrelational face-to-face delivery of services that are at the mercy of a volatile market-led funding model.

This is a confusing world for the expert practitioner, whose expertise is concentrated in his/her own particular field. However, in this new world, expert practitioners such as nurses, teachers, doctors and lecturers have been asked to become cognisant of the language of the market, the bank and the accountant (Ball, Citation2013). The structures of checks and balances, which have always surrounded health and education, but which have previously been centred on practice and delivered by professional associations such as the British Medical Association (BMA) and the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS), are now administered by government departments, often implemented by private providers, and have become instruments of fiscal control demonstrating the “market mentality” which now pervading the social policy which shapes our public services (DfE, Citation2010a; Lacher, Citation1999).

1.3. Summary

The context of this research is the low recruitment, low retention and high levels of stress being reported in both these public services and the temporal link between the rise in the incidence of these issues and the introduction of business practice to public services. The objective of this research was to investigate the likelihood of the existence of a cross-sectoral pattern of commentary from practitioners in both health and education regarding changes in their working practice. A similarity of response from participants from health and education would suggest that something more than individual failure on the part of particular practitioners is at work. It would indicate that we face a cross-sectoral structural failure. If this is the case, it is unproductive for policy-makers to assume that problems lie with individual practitioners, just as it is unproductive to offer resilience training to workforces dealing with systemic failure.

There has been a great deal of literature and research looking at the experiences of practitioners in both health and education in the UK. Both sectors report increasing levels of anxiety, depression and burn-out amongst staff (Day & Gu, Citation2010; McManus et al., Citation2002). However, this is the first paper to search for evidence of similarities between them. By gathering together evidence on the perception of their roles from practitioners in each institution we offer research which explores not only the nature of the ongoing distress amongst health and education practitioners in the UK, but to what extent the causes of the distress in these sectors is shared.

2. Methodology

The study described here used the inductive approach towards thematic analysis, in which the research was data driven, rather than being placed under an overarching methodological theory (Boyatzis, Citation1998). However, the ontological position of structuration (Giddens, Citation2013) offered a useful framework for this research into the workforces of two large public service institutions. Giddens states that the study of both text and behaviour should stem from the perceptions of the agents involved in their production; he also accepts that the perceptions of those “purposive” (Giddens, Citation2013:3) agents will have consequences on the structures those agents inhabit. Bhaskar also focuses on the research processes involved in studying “the human agent”, and identifies the epistemological task of the critical realist as that of “freeing these sciences from the intellectual grip of theories secreted by the flat, undifferentiated ontology of empirical realism” (Bhaskar, Citation2008:253). As Bhaskar developed the methodology of critical realism, he explicitly pointed up the parallels between his epistemological approach and the structuration theory of Giddens (King, Citation2010:255; Bhaskar, Citation2008:4). Bhaskar is suggesting that “intransitive generative mechanisms” are like the neurological basis of disease, which will not change regardless of the human interpretation of the cause of that disease; these are the usual subject of the natural sciences. However, “transitive generative mechanisms” are created by human agents in regard to their social behaviour and will, in turn, change that behaviour. They are not directly observable, but for critical realists, their study is admissible on the grounds that their effects are observable. As Braun and Clarke suggest, ‘critical realism acknowledges the ways individuals make meaning of their experience and, in turn, the ways the broader social context impinges on those meanings, while retaining focus on the material and other limits of “reality” (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014:9). Giddens, in aligning himself with the development and application of Bhaskar’s critical realist approach, describes the actions of the social researcher as “firing salvos into reality” (Kaspersen, Citation2000:13).

2.1. Methodological choice

In this research, a thematic analysis was undertaken, based on the five-step process of coding and analysing data set out by Braun and Clarke (Citation2014), using Patton’s approach to establishing heterogeneity (Patton, Citation2002). Boyatzis (Citation1998:4) has observed that thematic analysis is “not another qualitative method but a process that can be used with most, if not all, qualitative methods”. However, thematic analysis has been recognized for some time as a method in its own right, particularly by researchers in health and psychology (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). Thomas and Harden (Citation2008:13) report on its usefulness in their working paper for the ESRC National Centre for Research Methods on the need to use qualitative research “in the evidence base to facilitate effective and appropriate policy and practice”. They demonstrate how what they describe as the thematic synthesis of a number of interview-based studies allowed them to apply a “rigorous, transparent analytic system” (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008:11), with the opportunity to generate “higher order themes” (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008:13) from qualitative material. They conclude that thematic synthesis, built upon “years of methodological development” (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008:13), is a robust technology; their success with this technique suggests that evidence-based research, central to health and education policy-making, can be generated by a variety of methodologies, including those which would be deemed qualitative. They further comment that, although systematic review methods are well developed for certain types of research, such as randomized controlled trials (RCTs), methods for reviewing qualitative research in a systematic way are still emerging amongst much ongoing debate (Thomas & Harden, Citation2005). In their later working paper, Thomas and Harden (Citation2008) offer a positive critique of thematic synthesis as a useful method of bringing qualitative research into the framework for evidence-informed policy and practice.

3. Method and research design

3.1. Context

This research is focused on practitioner experience and grew from a response to the commentary of attendees at biofeedback relaxation workshops in the Midlands. Conducted in schools and universities, funded by Derbyshire Learning Authority and the Association of Teachers and Lecturers, these workshops were part of a stress reduction programme delivered to 400 education and health practitioners. It became apparent that practitioners from both sectors were consistently reporting the same experiences at work, often using the same language. Doctors, teachers, nurses and lecturers all talked of “feeling isolated”, “unsupported”, of becoming “nothing more than box-tickers” and wanting to “get out”.

3.2. Participants

To explore the nature and level of homogeneity of experiences of practitioners in health and education, while avoiding participant bias, a further cohort of thirty-six senior practitioners was identified; none of this cohort had attended or in any way been involved with the stress reduction programme.

The participant sample was chosen to satisfy the following criteria, the first of which also describes the population being studied:

to be an expert practitioner in the Health and Education workforce (having at least 4 years of certificated professional training in a specialist area of health or education)

to have at least ten years of experience of management role/s within the appropriate public service

to enact continued maintenance of direct weekly frontline contact with clients ie teaching, nursing or clinical practice.

The rationale behind the focus on the voice of senior practitioners, rather than early or mid-career professionals, is that senior practitioners have a professional responsibility for the whole practitioner cohort and a practical, executive experience of implementing change. As is common practice in both these workforces, all the participants also continued to use their professional skills in one to one interactions with students, patients or pupils. These factors therefore create amongst this group an opportunity to reflect upon change in the working lives of all expert practitioners in the areas being studied (Blumer, Citation1962).

3.3. Sampling strategy

The approach to potential participants was tested during the first pilot study; an introductory letter to a key practitioner, followed by a snowball sampling technique, was found to be an effective way of recruiting participants. Key employees, including a regional director of nursing and a chairman of a Midlands hospital trust, enabled access to groups of senior hospital staff as potential interviewees. Hospital consultants and directors of nursing took part in interviews and suggested further potential interviewees employed at their level. GP partners were contacted individually by letter and email to places of work, as were head teachers and senior university staff. Advanced Skilled Teachers (ASTs) were contacted individually through Local Education Authority contact lists and through a stall at an AST conference. Early interviewees in these groups also identified further potential participants Table .

Table 1. All participants: role, gender and age

The sample cohort involved hospital consultants, nurse directors, medical directors, GP partners, head teachers and university course leaders from thirty different institutions within six health trusts, five local education authorities, and one multi-academy trust.

Their work locations ranged from the University of Cambridge in the south to NHS Lothian in the north. These practitioners described themselves as “having undergone and/or implemented significant change in the workplace in the last fifteen years”.

3.4. Research questions

The research questions were:

what changes are taking place in the working lives of expert practitioners in health and education?

is there a shared pattern of experience between expert practitioners in both sectors?

3.5. Procedure

3.5.1. Interview schedul e

Following a pilot study with four British Council higher education advisors, a semi-structured interview schedule using guiding questions was developed. These asked participants for reflections on three broad areas of experience: firstly, the form of change in terms of environment and practice; secondly, the cause of change, whether it be bottom up from the practitioners and the clients, or top down from the policy-makers; and thirdly, to examine whether or not these changes have had a positive or negative effect on the working lives of these practitioners.

These practitioners agreed to take part in a one hour interview about changes in their working lives over the last fifteen years. “Changes in your working life” was chosen as a neutral phrase to identify the substantive nature of the subject matter under consideration. The final interview schedule was designed to have three phases, as follows:

Phase 1 was an introductory phase consisting of two “buffer” topics, which would serve the purpose of allowing the interviewee to only not identify themselves but situate themselves in the interview process and begin to reflect on their perception of their role. Phase 2 comprised the main body of the research questions, consisting of five questions dealing directly with the purpose of the inquiry of this research, being to explore the commentary of this participant group on the form of change, the cause of change and the effect of change on the working lives of expert practitioners in Health and Education.

Phase 3: this phase was designed to take a different direction from Phases 1 and 2 and to close the interview with an explicit focus on the participants’ perception of their efficacy at work. Bandura suggests that collective efficacy, being the success of a team or organization, is rooted in the self-efficacy of each member of that team, since “inveterate self-doubters are not easily forged into a collectively efficacious team” (Bandura, Citation1982:143). Since these participants worked in public services as part of interacting teams, their sense of efficacy was crucial to the successful outcome of events. Expert practitioners, per se, possess knowledge and skills at a high level; their feelings of efficacy should therefore, if realistic, be at a commensurately high level. Expert practitioners are decision-makers, they expect to enact change, particularly at the personal level of their pupils, patients and clients. “If they cannot enact change, and therefore have low efficacy, they will desert environments that are unresponsive to their efforts and pursue their activities elsewhere” (Bandura, Citation1982:141). Thus, low perceptions of efficacy may have a significant bearing on the low retention and low recruitment into these public service sectors.

3.5.2. Setting and time

Health and education practitioners are people sharing the “bounded time and space”, the “locale” of Giddens’ institutional workplace (Giddens, Citation1987). The school, the hospital, the university and even the GP practice, are bounded by the physical structure of their buildings and by the time keeping of the routine which guides each day. Therefore, to reflect the importance of the working space on perception, each interview was conducted in the teaching, consulting or office space of the interviewee. As Circourel states (in Bryman, Citation2008), it can be questioned whether interviews can capture the reality of the everyday working lives of practitioners, as interviews are in themselves an artificial situation. However, by using the usual workplace setting for each participant, it was sought to locate the interviews in the natural work environment. Each participant was invited to use his/her own office space for the interview and only two of the thirty participants and none of the pilot group suggested taking the option of meeting in a quiet workplace breakout area.

The interviewees were asked to allocate one hour for their interview; all interviews lasted at least 1 hour (some went on longer) and were recorded and transcribed within 12 hours by the interviewer.

3.6. Ethical guidelines

In compliance with the ethical codes of the University of Nottingham, procedures were followed in a prescribed way and confidentiality was assured. The voices were anonymized to preserve confidentiality in compliance with these ethical guidelines. Participants were told that they could withdraw themselves or their data at any time from the research. All participants read, discussed and signed a sheet informing them of this prior to the interview and in the presence of the interviewer.

3.7. Establishing theme credibility

All interviews were conducted by one researcher, the principal author of this paper, therefore there was no possibility of establishing theme credibility through interviewer inter-rater reliability (Thomas & Harden, Citation2005). Internal validification requires a demonstration of rigour (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006) and transparency regarding the process of moving from verbatim transcription, to codes and then to overarching themes. To facilitate this, each of the five stages of coding, including the final theme allocation, was interrogated closely by the two co-authors.

Leininger (Citation1994) advises researchers that the credibility of the themes chosen and results generated can be verified externally by member checks with the target population, following Schutz’s advice that to find “consistency between the researcher’s constructs and typification and those found in common sense experience, the model must be recognizable and understood by the ‘actors’ within everyday life” (Schutz, Citation1962: 44–43). It was possible to gather retrospective evidence of instances where the approach indicated by this research, that is, to encourage a relational, practitioner-led approach to change in the workplace, had been used to support efficacy. Figure lists a number of meetings, involving a presentation of this research followed by extensive discussion with groups of teachers, nurses, doctors, lecturers, all practitioners in the public services of Health and Education, which established credibility and tested the robustness of both the method and results through the process of peer debriefing (Lincoln & Guba Citation1985).

The above examples of the cohort group response to the methods and findings of this research demonstrate that external heterogeneity, and therefore validation for the findings of this research regarding the changing experience of the working life of expert practitioners in Health and Education, was established.

4. Results

Thematic analysis, as used here in conjunction with computer aided qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS), seeks to preserve the opportunity for in-depth detailed analysis of individual responses and also gives the opportunity for an identification of trends, patterns and outstanding phenomena (Coffey et al., Citation1996, p. 1) which gives it relevance to the population group being studied.

Fifty hours of digitally recorded data, transcribed and coded manually, provided a frequency of code applications (1,267 over fourteen codes) which supported a useful exploration of response clusters of this particular group through the use of CADQAS.

Table shows a wider picture of the application of coding to the data in order to establish themes. For a significant number of respondents, change to a more relational work practice (code 9), and the right to apply a combination of moral positioning and specialist knowledge, which was categorized as autonomy, (code 11) was linked to a feeling of greater efficacy (code 13). The exercise of specialist knowledge, the application of a professionally defined moral position and the full use of relational capacity lead to perceptions of increased efficacy. In contrast, top-down decision-making (code 10) and system-benefiting change (code 12) were linked by participants to increased feelings of reduced efficacy (code 14) (App 1). This juxtaposition of coded themes informed our understanding of the behaviour and attitudes of our participants. These data indicate that expert practitioners in health and education can only experience self-efficacy when they have a workplace which offers them autonomy and the space and time to create and maintain authentic, professionally intimate, relationships with clients and colleagues.

Table 2. Code Co-occurrence (codes 9–14)

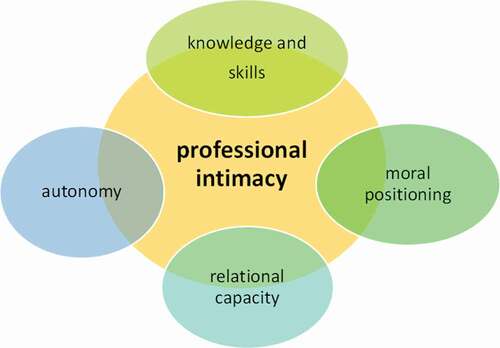

Figure shows the way in which the thematic categories of a) specialist knowledge, b) moral positioning and c) relational capacity, when present in combination, create the phenomenon we identify as professional intimacy.

Although described by participants as functioning as a tripartite mix, each category is discrete and has particular qualities:

Specialist knowledge The specialist knowledge of expert practitioners in health and education is created and supported by extensive, accredited training. It involves assessment of practice and of theoretical knowledge and can be examined through observation, written examination, interview and colleague/client feedback. Practitioner report also indicates the importance of practical experience in building the skills and knowledge of an expert practitioner (Lambert et al., Citation2014).

Moral positioning Moral positioning for expert practitioners in health and education centres around their responsibility to practice safely and without bias. Schneider and Snell (Citation2000) offer an example of an ethical framework for practitioners which asks them to reflect on core beliefs, past action, the reasoned opinion of others and finally to pose the question “what does our culture say about this situation?”

Relational capacity Relational capacity has been usefully described as the reciprocal gifting of respect and attention between the client and the practitioner; “the sharing of the human experience” (Heath, Citation2012). The communication skills of a “good” doctor or teacher have always been recognised as growing from a mixture of personal factors combined with the coaching of senior practitioners and maintained by experience (Slavich & Zimbardo, Citation2012).

Professional intimacy is a dynamic phenomenon. It is when these three categories exist in combination that the subsequent enactment of professional intimacy takes place. This enactment led to perceptions of increased self-efficacy in our participants and enabled their daily practice in health and education.

4.1. Participant commentary

The effect of the lack of this combination of factors is made apparent in this commentary by a head teacher. Far from enjoying the professional freedom promised to her by the Academies Act (Cameron, Citation2015), this head teacher of a new academy finds that her work is controlled even more closely by policy-makers:

It makes me so angry. Because I know—and it is awful, that there are certain criteria to meet or boxes to tick and if you don’t nail those … it … whatever happens nothing else we do matters because the category you are in if you don’t hit those boxes, if you don’t—well, essentially, you don’t get any money. There’s no triangulation, though—when I plan things I look at the key stake holders, the pupils—and if you are not doing it for the pupils—well, what’s the point? (MTA, Head Teacher)

For this Midlands Head, the “transformation” of education has become the “translation of policy into action” (Perryman et al., Citation2017) as policy makers feed a continual flow of initiatives and new targets to practitioners. This participant displays the surge of anger and frustration she is experiencing as her specialist knowledge is sidelined. She cannot exert her professional judgment because the control for her role has been taken from her and given to policy makers, and she “has to hit [their] boxes”. She asks ’if you are not doing it for the pupils—well, what’s the point?’ expressing the moral position she takes as a teacher. A position thwarted by the ethos of the new business-based regime. However, throughout her interview, counterpointing the repeated expressions of anger and frustration, another powerful element persisted. Namely, the search by this expert practitioner for an opportunity to exercise her relational capacity:

… and when I have a bad day or I have a difficult conversation I just take myself off, disappear, go into classrooms or hang off the door of the canteen and talk to pupils. You know, teachers will say to me “I’ve got a good day today—I’m teaching, not doing paperwork.” (MTA, Head Teacher)

She seeks out these moments to nurture herself as a teacher as much as to offer motivational support to the pupil. This is a symbiotic relationship. The increased sense of self efficacy this head teacher and her staff feel when they are “teaching not doing paperwork” is found in a synthesis of the “work role intimacy” identified as existing for expert practitioners in health and education (Kelchtermans, Citation2005) combined with, and supported by, their moral positioning and their substantive knowledge and training. It can be argued that it is this combination which allows the enactment of the “transformative nature of practice” (Stevenson, Citation2010) as a form of dyadic exchange between the practitioner and the client. A hospital consultant describes his concerns over changes in the nature of his role. He makes explicit how, in the past, the relationship with his patients was a satisfying experience for him:

Yes, we are losing the human skills, if you like. I am deeply sad that they (new doctors) are losing out on the opportunity, or the fun, of doing things the humanistic way … These changes, these protocols, targets, are making our relationship (between the practitioner and the client) unromantic, if you know what I mean …. That relationship used to give me great satisfaction. Humanity is all about interacting with another human being, isn’t it? You tell me your problem, and I can help you because I have a knowledge base and I will start talking … (KWN, Hospital Consultant)

The consultations this hospital practitioner has with his patients are no longer satisfying to him; the “fun” of doing things “the humanistic way” has been lost. The consultant goes on to explain that he fears that this quality is also being lost from co-colleague relationships:

It’s become like the airline industry—I got you from Dublin to London and I don’t know where you went afterwards … . fragmented … But we are on the same journey in the NHS, aren’t we? You want to meet somebody again and say, “Oh right, how are you? how did you do?” … I don’t remember all my junior doctors now, because they train so quickly their relationship with me is not all that strong. Now it’s all done in lectures, internet, tick boxes, appraisal and so on … . … . there’s a loneliness now, an isolation. When I was training I would sit down and talk to my consultant for hours about this patient and that … . (KWN, Hospital Consultant)

For this consultant system-led change has reduced the emotional quality of his working life, and he fears it has reduced the relationality of the training given to junior doctors. They will not have the opportunity to “sit down and talk to their consultant for hours about this patient and that”; the nature of their interactions with senior colleagues will be shaped through formal “appraisals” and by electronically designed “tick boxes”. The impression given here is that the information gathered about the progress of a junior doctor will be less about particular individual experience and more about fulfilling government targets. Gathering generic information for a government department has also entered into the space where the patient/doctor relationship is formed. This GP is concerned with the way this has made the consultation process less productive for the patient:

Targets, government targets, have altered the patient doctor relationship—because the patient comes in and says I’m a bit worried about my hip—and you say . ‘don’t worry about that Mr Smith—do you smoke? … and let me take your blood pressure—oh not much time left to talk about your hip—never mind—come along next week … but I’d achieved my target—I’ve ticked that box—and I’ve earned some money for the practice (laughs and shakes head) (pause) but you know what’s really important … I believe in touching the patient during a consultation … it’s reassuring … it’s the laying on of hands … and you can’t do that from behind a computer … (PRB, GP Partner)

Unlike the headteacher who is experiencing increasing exasperation, or the sense of loss apparent in the reaction of the consultant, the GP’s response is one of ironic humour, but his disquiet echoes the responses of the GPs in Solomon’s study (Solomon, Citation2009). Will his patients feel he is being “driven by guidelines” not by “their best interests”? Furthermore, he is aware that his behaviour has been shaped, not by professional judgement, but by the offer of direct payment for compliance. The “process” of gathering data has been fulfilled but the particular problems of this patient have not been addressed—an “outcome” will have to wait for a second visit, and the intimacy of touch has been side-lined.

In participants from the higher education sector we found the same disquiet, a fear that the “marketplace mentality” has superseded the “moral positioning” of the expert practitioner. This university course leader suggests that changes in his working day are tied up with this marketplace ideology:

… but you know, these changes happen because there is money to be made in this place and in schools, there’s money to be made so we all have to go along with it (less individual contact time) but you know—what is really important? How do I really work professionally? How do I communicate to this person what is required from a thesis so they can interpret the situation of the viva? But you have to judge … so the person feels that they are moving somewhere … that’s about the dance of relationships. For us (lecturers) bureaucracy has taken over—a bureaucracy to guarantee quality—lecturers have been reduced to functionaries. Audits everywhere. (GRP University Course Leader)

Less contact time means that there is less time for interaction with students. The relationship between the supervisor and the student, something of deep interest and concern to this participant, has been marginalised, like the moments of touch in a GP consultation. The contract between the practitioner and client is broken, and what has been put in its place are audits. Working well with colleagues also relies upon successful and satisfying interpersonal dynamics (Ashforth & Humphrey, Citation1993; Bandura, Citation1982). How those dynamics work to create a productive and enjoyable harmony for a team of practitioners can be further understood in the commentary of this Nurse Director:

… you know when you are in a room and you are having a meeting and you know each other and the conversation is like the flow of music. You know when one person leans forward, you know that’s their sign that they want to say something … you get to read those messages so the music almost flows. Pause. But it’s what keeps you going. It’s hard, this job. Pause. You know, every shift my staff deal with hard stuff … people’s pain and fear—but that flow—it’s the glue. Without it we won’t get through (PJK Nurse Director)

“We won’t get through” implies the bleak future envisaged by this Nurse Director. “The glue” she describes, the essential nature of being connected to other members of her team, is also described by practitioners in education. This head teacher likens the underpinning of a successful school to the ecosystem underneath a forest:

You see I am a biologist by trade and I think that we (teachers) are like a forest. Trees all connect to each other through a huge underground network of fungi and other stuff. You can’t see it but it is there. If this isn’t being nurtured any more then—the forest dies. It won’t be noticeable at first but eventually it will be gone. That is what is happening to education. No one is nurturing what it means to be a teacher. All the thousands of interactions and exchanges that take place every day. No-one at the top knows about them anymore. It will look alright for a while—all singing and all dancing—great data—but then it will be dead. No forest—no teachers (BWP headteacher).

The ecosystem of constant human interaction, the “thousands of interactions and exchanges that take place every day” in schools, universities, hospitals and GP surgeries, is where the support, advice and knowledge essential to practice is situated and the social identity of the practitioner is reinforced by these exchanges.

The practitioners interviewed for this study describe the success of their daily work as teachers and healers as depending on the application of their knowledge during the “dance of relationships”, and the “flow of the music” of conversations. This is the “humanistic way of doing things”; the business-mediated world of public service may, in the end, offer nothing more than an “arid wasteland” where clients as well as practitioners struggle to maintain their social identity (Zuboff, Citation2019).

5. Discussion

The term “professional intimacy” describes a dynamic interaction which is set in motion by the presence, not only of the enabled practitioner, but of a client who has confidence in the authenticity of the transaction. Using the sociobiological prism of Rose (Citation2013), the roles of the “teacher” and the “healer” can be seen as fundamental to our society, necessary to group survival, their function enacted through meetings between these practitioners and their clients It can be argued that the “altruism” identified as one of the aspects of professional behaviour by Ritzer and Walczak (Citation1988) is not an incidental, heroic element of human behaviour, but an essential tool for group survival (Trivers, Citation1971). Our public services of Health and Education, the school, the hospital, the university, can be seen as the contemporary socio-political manifestations of the social drive towards this altruism; the role of the teacher and healer within these structures could therefore be seen to be an ongoing application of human altruism. It can be argued that the particular properties of professional intimacy allow this application of altruism to take place in the “daily milieu” of work by expert practitioners with clients in these public institutions.

However, the privileging of business practice in the delivery of public services has shifted the idea of what being an expert practitioner entails. The 21st-century expert practitioner in health and education sits between the intimate and unique nature of face-to-face interaction with clients, students, patients and pupils, and the transformation of these “instantiations” (Giddens, Citation2013) into abstracted events, assessed on a quantitative scale of success. Their perception of the reality of their role has to accommodate the request, first to make, and then to explain, defend or justify these abstracted ordinal interpretations of their behaviour. These abstracted ordinal interpretations of their professional actions, where care, attention and professional judgment are quantified into aims and targets, are made all the more compelling as “the language of expertise [the expertise, in this instance, of the data interpretation of accountancy] plays a role here; its norms and values seeming compelling because of their claim to be a disinterested truth” (Miller & Rose, Citation2008:35).

This form of control forcibly translates the objectives of one party (in this case the professions of healing and teaching) into terms acceptable to others (the business-compliant state) to such an extent that certain norms, such as service, altruism and dedication, may be supplanted by others, such as competition and financial rationalisation (Moffat et al., Citation2014:696). Arguably this procedure sets up a cognitive dissonance within the expert practitioner (Festinger, Citation1957). When someone is forced to do (publicly) something they (privately) really don’t want to do, dissonance is created between their cognition (I didn’t want to do this) and their behaviour (I am doing it). Forced compliance occurs when an individual performs an action that is inconsistent with his or her beliefs (Festinger, Citation1964; Festinger & Carlsmith, Citation1959). The clash of two ideologies, that of “service” and “business” is clear. It can be argued that the aggressive implementation of business practice (Rifkin, Citation2000; Vujnovic, Citation2017), combined with sophisticated consumer feedback software (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004), has led to the creation of an “experience economy” (Boswijk et al., Citation2005; Pine & Gilmore, Citation1998) where a simple commodity can be transformed into “an experience”, enhancing both its emotional and its fiscal value. Being taught, learning, is also an “experience”. But a teacher, unlike a merchandiser, is not “staging an experience” to “captivate the customer” (Pine & Gilmore, Citation1998). A teacher is seeking to transform lives, to satisfy real needs; the fundamental ethos of education, as with healing, is that it is truly transformational (Mezirow, Citation2000; Slavich & Zimbardo, Citation2012; Stevenson, Citation2010).

It is worth noting, that, notwithstanding the apparent dominance of the business model, the qualities of “altruism, autonomy, authority over clients, general systemic knowledge, distinctive occupational culture” (Ritzer & Walczak, Citation1988:6) remain enshrined in the accepted behaviour of professionals. They are made evident in the ethical statements of professional bodies like the British Psychological Society (Citation2006), the Royal College of Nursing (Vryonides et al., Citation2014), the British Medical Association Medical Ethics Department (Citation2014), and the Chartered College of Teaching (Hazell, Citation2017). Even by those promoting the competitive business model, these qualities are seen as prime factors in a good outcome for a client (Schleicher, Citation2012). The “neoliberal model” (Ball, Citation2013:5) and “neoliberal rationality” (Lemke, Citation2001:201), recognized as a danger to the autonomy of the expert practitioner (Ball, Citation2013), may prioritize the client as “consumer” (Ball, Citation2013) and seek to “commodify” the functions of Health and Education but the enduringly relational, client-based nature of these public services means that the actions of the individual practitioner are still central to the success of each service as a whole. Practitioners may suffer from low morale and feel powerless but they are more influential than they realise. However, the landscape of their working lives is changing, and their opportunities to shape the future are rapidly diminishing.

6. Conclusion

Throughout this commentary by teachers, doctors, nurses and lecturers on the changing nature of their working lives, there is a discernible, all-pervading theme. We have chosen to describe this theme as a “cry”. A “cry”, sometimes of anger, sometimes of loss, which has, at its core, the desire of these practitioners to be allowed to practice their skills, to apply their knowledge, to further their research: a cry for professional intimacy. Their sense of self- efficacy is fed by the successful practice of their skills and the recognition by their employers, their peers and their clients, that they are practising successfully. These highly-trained and motivated practitioners find that excessive and inappropriate monitoring is counter-productive, creating fear, anger and reducing self-efficacy. The “professional intimacy” they seek is the one-to-one moment of discovery and transformation which happens when thoughtfully applied knowledge or skill changes the life of the recipient. These are reciprocal moments: they are transformational for the teacher, the healer, as well as for the student, the patient, and the pupil (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985; Goold & Lipkin, Citation1999) and they are vital to the success of our national institutions of health and education.

correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fiona Birkbeck

Fiona Birkbeck’s particular research interest is the relationship between social policy and the role of expert practitioners in the public services of health and education. She has contributed to the Masters in Educational Leadership at the University of Nottingham and also to development of the Masters in Medical Education and Research at De Montfort University and developed training programmes on building resilience using biofeedback equipment for the National Education Union, the British Psychological Society and for medical and nursing staff in a number of Acute Hospital Trusts. She is a Cochrane Reviewer (University of Nottingham 2019) and is contributing a chapter to a forthcoming book presenting innovative solutions to the issues facing the delivery of General Practice in the UK. Her writing on social policy and the practitioner can be found the Institute of Mental Health Nottingham blogsite: http://imhblog.wordpress.com/, and in Fostering Resilience through School Leadership, Beyond Survival: http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/education/documents/research/crsc/teacherresilience/beyondsurvival- teachersandresilience.pdf

References

- Ashforth, B. E., & Humphrey, R. H. (1993). Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. The Academy of Management, 18(1), 88–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/258824

- Bailey, A. (2013). More teachers are sick with stress [online]. Teacher Support Network (now Education Support Network). No longer available. Original link http://teachersupport.info/news/09-january-2013/m ore- teachers-are-sick-stress#.URK0LaVjoRl" [1 May 2014]. For further information see: https://www.educationsupportpartnership.org.uk/about-us/press- releases

- Ball, S. J. (2012). Global education Inc: New policy networks and the neo-liberal imaginary. Routledge.

- Ball, S. J. (2013). The education debate (2nd ed.). The Policy Press.

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Bhaskar, R. A. (2008). A realist theory of science (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Black, C. (2008). Black review of the health of Britain’s working age population. The cross-government health, work and well-being programme. TSO.

- Blumer, H. (1962). Society as symbolic interaction. In A. Rose (Ed.), Symbolic interactionism (pp. 179–192). Prentice-Hall.

- Boswijk, A., Thijssen, J. P. T., & Peelen, E. (2005). A new perspective on the experience economy: Meaningful experiences. Pearson Education.

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can thematic analysis offer health and well-being researchers? Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 9, editorial. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4201665/

- British Medical Association Medical Ethics Department. (2014). Medical ethics today: Its practice and philosophy. Wiley.

- British Psychological Society. (2006). Code of ethics and conduct.

- Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Buchan, J., Baldwin, S., & Munro, M. (2008). Migration of Health Workers: The UK Perspective to 2006. Papers, No. 38. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/228550573624

- Cameron, D. (2015). PM speech: This is a government that delivers [online]. Retrieved January 1 2015, from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speech- this-is-a-government-that-delivers

- Coffey, A., Holbrook, B., & Atkinson, P. (1996). ‘Qualitative data analysis: Technologies and representations’. Sociological Research Online. Retrieved December 4, 2015, from. http://www.socresonline.org.uk/1/1/4.html>

- Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2010). The new lives of teachers. Routledge.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

- Department for Education. (1988). The education reform act [online]. Retrieved April 25, 2019, from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/40/contents1988

- DfE. (2010a). The case for change. TSO.

- DfE and the National College for School Leadership. (2015). Teacher Supply Model Part 1 and Part 2 2014-2015. Retrieved November 19, 2015, from. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/teacher-supply-model

- DH. (2012a). Health and Social Care Act 2012 (c. 7) Part 1 – The health service in England 13D Duty as to effectiveness, efficiency etc. (p.19).

- Edwards, A. (2010). Being an expert professional practitioner. The relational turn. Springer.

- Evetts, J. (2003). The sociological analysis of professionalism: Occupational change in the modern world. International Sociology, 18(2), 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580903018002005

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), Article 7. Retrieved March 18 2017, from http://www.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/backissues/5_1/html/fereday.htm

- Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Festinger, L. (ed). (1964). Conflict, decision, and dissonance (Vol. 3). Stanford University Press.

- Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58(2), 203. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041593

- Giddens, A. (1987). Social theory and modern sociology. Polity.

- Giddens, A. (2013). The constitution of society. Outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press.

- Goold, S. D., & Lipkin, M. (1999). The doctor-patient relationship: Challenges, opportunities, and strategies. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14(1), S26–S33. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00267.x

- Greany, T., & Higham, R. (2018). Hierarchy, markets and networks analysing the ‘self-improving school-led system’ agenda in England and the implications for schools. London UCL Press.

- Harvey, D. (2007). Neoliberalism as Creative Destruction. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 610(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206296780

- Hazell, W. (2017, January 18). Chartered college of teaching opens its doors TES. Retrieved June 30, 2018, from. https://www.tes.com/news/chartered-college-teaching-opens-its-doors

- HC. (2016). HC 73 committee of public accounts 2016-2017 3rd report of session training new teachers TSO.

- Heath, I. (2012). Love’s labour’s lost: Why society is straitjacketing its professionals and how. Michael Shea Memorial Speech, International Futures Forum. Edinburgh.

- Jawahar, I. M., & Stone, T. H. (2011). Fairness perceptions and satisfaction with components of pay satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26(4), 297–312. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111124836

- Kaspersen, L. B. (2000). Anthony giddens. An introduction to a social theorist. translated by Sampson, S. Blackwell.

- Kelchtermans, G. (2005). Teachers’ emotions in educational reforms: Self- understanding, vulnerable commitment and micro-political literacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(8), 995–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.009

- Keogh, B. 2013. Review into the Quality of Care and Treatment Provided by 14 Hospital Trusts in England: Overview Report [online]. TSO. Retrieved April 10 2016, from. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/bruce-keogh- review/Documents/outcomes/keogh-review-final-report.pdf

- King, A. (2010). The odd couple: margaret archer, Anthony Giddens and British social theory. The British Journal of Sociology, 61(s1), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01288.x

- Lacher, H. (1999). Embedded Liberalism, disembedded markets: Reconceptualising the pax Americana. New Political Economy, 4(3), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563469908406408

- Lambert, T. W., Smith, F., & Goldacre, M. J. (2014). Views of senior UK doctors about working in medicine: Questionnaire survey. JRSM Open, 5(11), 2054270414554049. https://doi.org/10.1177/2054270414554049

- Leininger, M. (1994). Evaluating criteria and critique of qualitative research studies. In J. Y. S. Lincoln & E. G. Guba (Eds.), Naturalistic Inquiry (pp. 1985). Sage.

- Lemke, T. (2001). “The birth of bio-politics”: Michel Foucault’s lecture at the College de France on neo-liberal governmentality. Economy and Society, 30(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140120042271

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Marginson, S. (2013). The impossibility of capitalist markets in higher education. Journal of Education Policy, 28(3), 353–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.747109

- McManus, I. C., Winder, B. C., & Gordon, D. (2002). The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. The Lancet, 359(9323), 2089–2090. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08915-8

- Mezirow, J. (2000). Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. Jossey-Bass.

- Miller, P., & Rose, N. (2008). Governing the present: Administering economic, social and personal life. Polity.

- Moffat, F., Martin, P., & Timmons, S. (2014). Constructing notions of healthcare productivity: The call for a new professionalism? Sociology of Health & Illness, 36(5), 686–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12093

- Molnar, A. (2006). The commercial transformation of public education. Journal of Education Policy, 21(5), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930600866231

- Nuffield Trust. (2016). Health leaders panel: Survey six: Footprints, financing and staffing [online]. Retrieved July 7, 2016, from. http://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/our- work/projects/health-leaders-survey-results-6

- OECD. (2014). Report teaching and learning international survey (TALIS) [online]. Retrieved November 28 2015, from. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/repository/education/library/reports /2014/talis_en

- OECD. 2015a. Education policy outlook 2015: Making reforms happen [online]. Retrieved June 9 2014, from. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264225442-en

- OECD. (2015b). Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2015-en

- Parkin, E., & Powell, T. (2016). General PRACTICE in England commons briefing papers CBP-7194. House of Commons Library.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Perryman, J., Ball, S. J., Braun, A., & Maguire, M. (2017). Translating policy governmentality and the reflective teacher. Journal of Education Policy, 32(6), 745–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1309072

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1998). Welcome to the experience economy. Harvard Business Review, 76(4), 97–105.

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(3), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20015

- RCN, 2015. Frontline First Report. (b). (2015). The fragile frontline. Royal College of Nursing.

- Rifkin, J. (2000). The age of access: The new culture of hypercapitalism where all of life is a paid-for experience. Penguin Putman Inc.

- Ritzer, G., & Walczak, D. (1988). Rationalization and the deprofessionalization of physicians. Social Forces, 67(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579098

- Rose, N. (2013). The human sciences in a biological age. Theory Culture and Society, 30(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276412456569

- Schleicher, A. (2012). Preparing teachers and developing school leaders for the 21st century: Lessons from around the world. OECD.

- Schneider, G. W., & Snell, L. (2000). C.A.R.E. An approach for teaching ethics in medicine. Social Science & Medicine, 51(10), 1563–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00054-X

- Schutz, A. (1962). Collected papers 1: The problem of social reality. Martinus Nijhof.

- Slavich, G. M., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2012). Transformational teaching: Theoretical underpinnings, basic principles, and core methods. Educational Psychology Review, 24(4), 568–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-012-9199-6

- Solomon, J. (2009). An exploration of the relationship between prescribing guidelines and partnership in medicine taking [PhD Thesis]. University of Leeds.

- Stevenson, H. (2010). Working in, and against, the neo-liberal state: Global perspectives on K-12 teacher unions. Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor, 17, 1–10. Retrieved June 26, 2016, from. http://ices.library.ubc.ca/index.php/workplace/article/view/182296

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2005). Methodological issues in combining diverse study types in systematic reviews. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(3), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645570500155078

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Till, R. E., & Karren, R. (2011). Organizational justice perceptions and pay level satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111099619

- Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 40(1), 35–57. https://doi.org/10.1086/406755

- UCAS. (2015). Data and analysis: Undergraduate releases [online]. Retrieved November 19, 2015, from. https://www.ucas.com/corporate/data-and-analysis

- Verger, A., Fontdevila, C., & Parcerisa, L. (2019). Reforming governance through policy instruments: How and to what extent standards, tests and accountability in education spread worldwide. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 248-270. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2019.1569882

- Vryonides, S., Papastavrou, E., & Charalambous, A. (2014). The ethical dimension of nursing care rationing: A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. [online]. Nursing Ethics. 22(8):881–900. Available at: Nurs Ethics. 2015 Dec. Epub 2014 Nov 3. Retrieved March 17 2017, from https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014551377

- Vujnovic, M. (2017). Hypercapitalism. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), The Wiley‐Blackwell encyclopedia of globalization. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470670590.wbeog278.pub2

- Wilensky, H. L. (1964). The professionalization of everyone? American Journal of Sociology, 70(2), 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1086/223790

- Zuboff, S. (1988). In the age of the smart machine: The future of work and power. Basic Books.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism. London Profile Books.