Abstract

Demanding new ventures has been a global challenge, and the government responds to this issue through entrepreneurial education. Among the increasing studies on entrepreneurship, there is a lack of empirical evidence examining how entrepreneurial education prepares students being entrepreneurs. This study elaborates on several predicted variables that can drive students’ entrepreneurial preparation, including entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial knowledge, and entrepreneurial mindset. The methodological approach taken in this study is a quantitative method undergoing a survey model. The benefit of this approach aims to gain an understanding of how entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial knowledge, and entrepreneurial mindset can influence the entrepreneurial preparation of students. The respondents of this study were gathered from vocational students (SMK) in Jakarta of Indonesia were calculated using Structural Equation Modelling Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS). The findings showed that entrepreneurial education plays an essential role in determining knowledge and entrepreneurial mindset that leads to the entrepreneurial preparation of students. The finding also confirmed that entrepreneurial knowledge positively influences the entrepreneurial mindset, entrepreneurial preparation, and successfully mediates the impact of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial preparation. The latest finding is that the entrepreneurial mindset positively influences students’ entrepreneurial preparation.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Entrepreneurship has become a widely recognized machine in alleviating poverty over the world, identifying the factors affecting students’ entrepreneurial preparation has always been a significant interest. This study elaborates on several predicted variables that can drive students’ entrepreneurial preparation in Indonesia. These findings are useful for schools, government, and stakeholders in developing entrepreneurship education for vocational school and providing insight into Indonesia’s increasing entrepreneurs.

1. Introduction

The formation of new ventures is the primary concern of government in both developed and developing countries (Barba-Sanchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, Citation2018; Nowinski et al., Citation2019; Wibowo et al., Citation2019). The fundamental reason is that small and business promotes job opportunities than can lead to a tremendous contribution to economic development, economic growth, and community welfare (Bjørnskov & Foss, Citation2008; Tung et al., Citation2020; Turkina & Thai, Citation2013). Since it was reported an important role in providing new enterprises, entrepreneurial education has been attracted much interest among scholars (Bae et al., Citation2014; Turner & Gianiodis, Citation2018).

Inevitable prior studies have performed a correlation between entrepreneurial education and start-up inception (Harms, Citation2015; Jung & Jung, Citation2018; Mamun et al., Citation2017; Sarooghi et al., Citation2019). The findings showed that entrepreneurial education plays a crucial role in determining entrepreneurial mindset, knowledge, and intention being entrepreneurs. Dealing with this issue, it has gained government attention for enhancing the quality entrepreneurship from various perspectives (e.g., curriculum, teachers, workshops, laboratories, and supporting facilities) (Dinis et al., Citation2013; Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2015).

Accordingly, the Indonesian government presents several endeavors to enlarge the innumerable entrepreneurs by optimizing the entrepreneurial education in all level educations (Syam et al., Citation2018; Utomo et al., Citation2019; Wahidmurni et al., Citation2019; Winarno, Citation2016). In the secondary school level, the government has concerned about revitalizing the vocational high school curriculum to effectively form students being entrepreneurs (Saptono et al., Citation2019; Wibowo et al., Citation2019). The primary reason is that the SMK graduates are young entrepreneurs instead of mid-level skilled workers. Surprisingly, the data from Statistics Indonesia in 2019 showed that the higher unemployment rates were dominated by SMK graduates (BPS, Citation2019). In this regard, several studies argue that the lack of entrepreneurial education failed in enhancing knowledge of entrepreneurship (Ghina et al., Citation2017; Rauch & Hulsink, Citation2015; Rina et al., Citation2019; Tung et al., Citation2020; Walter & Block, Citation2016).

Since the escalating studies on entrepreneurship, there is a lack of empirical evidence examining how entrepreneurial education prepares students being entrepreneurs. This study aims at investigating the relationship entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial knowledge, entrepreneurial mindset, and entrepreneurial preparation. The contributions of this study are three folds. First, it contributes to the existing literature on the determinant factors influencing individuals in setting new ventures by engaging entrepreneurial knowledge, which is missing in the prior studies. Second, a considerable amount of entrepreneurial education in Indonesia has been recognized in university students (Larso & Saphiranti, Citation2016; Patricia & Silangen, Citation2016; Wahidmurni et al., Citation2019), while this empirical work has been conducted in the level of vocational school. The fundamental reason is that the vocational school graduates are expected preparing students in starting business instead of being middle-class worker. Third, this study provides new insights into the critical role of entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention in setting new ventures.

2. Literature review

2.1. Entrepreneurial education

Entrepreneurial preparation is associated with the readiness of being entrepreneurs, which defined as the confluence set of personal traits that distinguish individuals in preparing for business. In this matter, individuals should have a particular competency in observing and analyzing their environment linked by high creative and productive potential (Ruiz et al., Citation2016). Also, Coduras et al. (Citation2016) and Olugbola (Citation2017) noted that the entrepreneurship readiness is determined by several aspects, including social-psychological, economic, business, and management. These subjects present measures of both qualitative and quantitative variables that have been associated with scientific research in the field of entrepreneurship. For students, those scholars strongly agree that entrepreneurial education affects preparation for entrepreneurs.

How does entrepreneurial education prepare students being entrepreneurs? Several scholars have reached a consensus that education is a scenario and effective means in preparing students to be entrepreneurs (Bazkiaei et al., Citation2020; Hockerts, Citation2018; Jena, Citation2020; Nowinski et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, Chrisman and McMullan (Citation2002) mentioned that the primary goal of entrepreneurial education is not only to grow entrepreneurial intention but also to prepare students being entrepreneurs. Similarly, Barbosa et al. (Citation2008) remarked that entrepreneurial training could strengthen intentions, behavior, improve performance and prepare entrepreneurs.

In addition, Backström-widjeskog (Citation2010) emphasized that entrepreneurship education influences entrepreneurial intentions and prepares students for entrepreneurs in three folds; learning, inspiration, and resources use. Preparing students being entrepreneurs can be improved through practice in the field instead of theory in the classroom (George & Bock, Citation2011). Through practice, entrepreneurship education enables students to have much knowledge and practice it directly. Prior studies confirmed the effect of entrepreneurial education on students’ entrepreneurial preparation (Coduras et al., Citation2016; Ruiz et al., Citation2016).

H1: Entrepreneurial education has a positive impact on entrepreneurial knowledge

H2: Entrepreneurial education has a positive impact on entrepreneurial mindset

2.2. Entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial mindset

According to entrepreneurial human capital (EHC) theory, individuals who have entrepreneurial knowledge are likely to become entrepreneurs (Ni & Ye, Citation2018). Combining entrepreneurial knowledge with various types of information and skills can develop excellent stuff and services to fulfill market desires. These entrepreneurs will also be sharper in seeking out existing opportunities, challenges, and maximizing resources effectively. Some antecedent scholars confirmed that entrepreneurship knowledge influences entrepreneurial readiness, startups, and new business development (Coduras et al., Citation2016; Ruiz et al., Citation2016; Tung et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, an entrepreneurial mindset is a feeling and belief with a unique way of seeking the opportunities and challenges (Nabi et al., Citation2017; Solesvik et al., Citation2013). Researchers agree that the entrepreneurial mindset is included as a holistic recognition of fostering novel ideas, analyzing opportunities and obstacles, and running a business, whereby a person inwardly assesses his or her perspectives derived from holistic thinking instead of practical attributes (Bosman, Citation2019; Davis et al., Citation2016). Additionally, Walter and Block (Citation2016) pointed out that the entrepreneurial mindset is a way of thinking that seeking out opportunities instead of challenges, consider any chances rather than failures, looking for solutions instead of complaining about a problem.

H3: Entrepreneurial knowledge has a positive impact on students’ entrepreneurial preparation

H4: Entrepreneurial knowledge has a positive impact on entrepreneurial mindset

H5: Entrepreneurial knowledge has a positive impact on students’ entrepreneurial preparation

3. Entrepreneurial mindset, entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial preparation

Relevant to the number of previous studies, Fayolle and Linan (Citation2014); Akmaliah et al. (Citation2016) pointed out the notion of entrepreneurial mindset as a certain of mind that orientates individuals’ behavior toward activities and outcomes related to entrepreneurship. Additionally, those scholars also argued that the entrepreneurial mindset is closely linked with how an individual thinks or states of mind (conscious or sub-conscious) or the perspective through which one sees the world, influencing one’s tendencies for entrepreneurship and success in these activities. Solesvik et al. (Citation2013) reported that entrepreneurial education enacts an essential role in enhancing the entrepreneurial mindset. Shepherd et al. (Citation2010) support this view and have verified that the entrepreneurial mindset offers potential insights into the several outcomes and circumstances necessary for entrepreneurial studies.

Entrepreneurship education in all levels of education play three prominent roles in enhancing the mindset of entrepreneurship. First, it creates an entrepreneurial culture that pervades all projects. Additionally, entrepreneurial education allows students to learn more about entrepreneurship itself. Lastly, through specialized courses for individuals, it provides greater chances for them to present new ventures (Klofsten, Citation2000). To improve entrepreneurial intentions and readiness being entrepreneurs, schools, or universities need to promote cross-curricular courses accompanied by a particular business training program (Barba-Sanchez & Atienza-Sahuquillo, Citation2018).

H6: Entrepreneurial mindset has a positive impact on students’ entrepreneurial preparation

H7: Entrepreneurial knowledge mediates the influence of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial preparation

3.1. Method

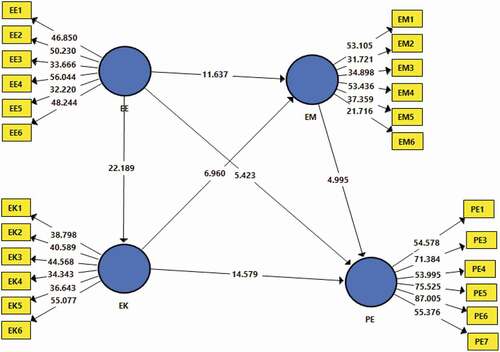

This study used a quantitative research method employing a survey model. The benefit of adopting this approach gains a detailed understanding of how entrepreneurial education, entrepreneurial knowledge, and entrepreneurial mindset influences students’ entrepreneurial preparation (see Figure ). The dependent variable used in this study is entrepreneurial preparation (PE), while entrepreneurial education (EE), entrepreneurial knowledge (EK), and entrepreneurial mindset (EM) predicated as the independent variable. The project employed a convenience sample of 480 vocational school students (SMK) of the second- and third-year study in Jakarta, Indonesia. After removing approximately 6.25% of missing data, approximately 450 responses from participants can be used for further data analysis. The demographic of respondents is provided in Table .

Table 1. The demographic profile of respondents

To calculate respondent reactions to entrepreneurial preparation (PE), we adapted seven indicators from Tung et al. (Citation2020), while to measure entrepreneurial education (EE), we engaged instruments adopted from Hasan et al. (Citation2017); Denanyoh et al. (Citation2015). Furthermore, students’ entrepreneurial knowledge (EK) was measured by items adapted from Roxas (Citation2014). Lastly, to understand the students’ entrepreneurial mindset (EM), we employed items from Mathisen and Arnulf (Citation2013). Each construct was measured using the five-point Likert Scale from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Lastly, we regressed using Structural Equation Modelling Partial Least Squares (SEM-PLS) undergoing SmartPls (version 3.0) to estimate the relationship between variables.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Results

The demographic respondents in this study are provided in Table . In general, this study’s respondents were students with the range age of 15 to 17 years old and are dominated by females with a percentage of almost double than males. Additionally, from the table, it can be known that the subject study of vocational students in Indonesia was divided into three: office administration, marketing, and business program as the most popular subject. Lastly, the highest percentage of parents’ occupation was an entrepreneur with almost reaching 50% of respondents.

4.1.1. The outer and inner assessment model

The assessment of the predictive model is divided into two: the outer assessment model and the inner assessment model. We evaluated four criteria for the outer assessment model, including convergent validity, discriminant validity, composite reliability and construct reliability (see Table ). The results of convergent validity can be seen that all variables, namely entrepreneurial education (EE), entrepreneurial knowledge (EK), entrepreneurial mindset (EM), and entrepreneurial preparation (PE), have loading factor which ranging between 0.724 and 0.912. It implies that the variables satisfy the convergent validity (loading factor >0.70) (Chin & Marcoulides, Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2013). Additionally, from Table , it can be known that the AVE value for all variables is higher than 0.5, which meaning that the variables meet the discriminant validity criteria.

Table 2. Results of Measurement (Outer) Model

Furthermore, EE, EK, EM, and PE have the CR score of 0.950, 0.943, 0.920, and 0.956, respectively (>0.70), which implies that those variables meet the composite reliability criteria (Chin & Marcoulides, Citation1998, Citation1998; Hair et al., Citation2013). Indeed, Cronbach Alpha (α) scores of EE, EK, EM, and PE are 0.937, 0.928, 0.895, and 0.944, respectively (>0.70), which means that it has satisfied the composite reliability criteria (see Table ). In addition, the convergent validity is provided in Table . In more detail, it is known that the loading value of the variables EE, EK, EM, and PE is greater than 0.70, which implies that these variables meet the convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2013).

Table 3. Discriminant Validity

4.1.2. The collinearity and R-squared test

The collinearity test is attempted to understand the presence of collinearity in the model. The result of the collinearity test, it can be concluded that the value of VIF is ranging between 1.49 and 3.99 < 5.00, which implies that the collinearity is not apparent, and the construct of the variable is valid. Meanwhile, the R-squared test is intended to indicate the strength of correction from predictions with the category 0.67 (substantial), 0.33 (moderate), and 0.19 (Weak) (Chin & Marcoulides, Citation1998). The result of the R-square test showed that EK has a value of 0.441, which implies that 44.1% variable EK can be moderately explained by the variable of EE. Meanwhile, the R-square value of EM is moderately explained by EE and EK with a score of 0.633. Lastly, the variable of PE is moderately predicted by EE, EK, EM with a percentage of 52.1%.

4.1.3. The size effect test (f2)

The size effect test (f2) aims to determine the extent of the influence of the latent predictor variable (exogenous latent variable) on the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2013). In this study, the size effect (f2) is divided into three categories: small (0.02), medium (0.15), and large effect (0.35). The test results show that the f2 values of EE, EK against EM were 0.613, which implies that it provides a large effect size. Furthermore, the f2 values of EE, EK, EM, against PE were 0.717, which showed a large effect size.

4.1.4. Predictive relevant test (Q2)

The predictive test (Q2) aims to measure how the observed value produced by the model and also its parameter estimates. For the Q-square predictive relevant test (Q2), we followed the criteria from Hair et al. (Citation2013) and Chin and Marcoulides (Citation1998), which the value of Q2 > 0 shows that the model is having predictive relevance value and vice versa. Based on the model testing results, it is known that the Q2 value of each variable is greater than 0, thus showing that the model has a predictive relevance value.

4.1.5. The coefficient path analysis

The path analysis is aimed to evaluate the constructed model of this study. For the SEM-PLS, the bootstrapping procedure has come to estimate the value of t-statistic and t-value. Table and Figures illustrate the value of the path coefficient (p-value) from the relationship between variables is significant with the value of 0.000.

Table 4. The summary of testing results

5. Discussion

This study provides evidence on how entrepreneurial education, mindset, and knowledge affect students in preparing for entrepreneurs in Indonesia. From the analysis, this study confirmed that the seven hypotheses proposed were accepted. The first finding is that entrepreneurial education positively influences entrepreneurial knowledge. This result broadly supports the work of other studies in this area linking entrepreneurial education with entrepreneurial knowledge (Tung et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2012). The primary reason is that entrepreneurship education plays an essential role in equipping students as potential entrepreneurs with much-needed knowledge and skills to manage business later. This also results in line with the prior study by Keat et al. (Citation2011), which revealed that entrepreneurship education provides students with the knowledge, skills, and motivation to pursue careers in the field of entrepreneurship.

With respect to the first hypothesis, it is found that entrepreneurial education has an impact on the entrepreneurial mindset. The finding of this study is relevant with the prior studies by Nowinski et al. (Citation2019), Hockerts (Citation2018), Ruiz et al. (Citation2016), Coduras et al. (Citation2016), and Walter and Block (Citation2016), which pointed out that entrepreneurial education acts an important role in developing mindset being entrepreneurs. In short, entrepreneurial education not only enhances knowledge, attitudes, and competencies but also inclines motivation to engage an entrepreneurial mindset. Similarly, Solesvik et al. (Citation2013), Haynie et al. (Citation2010), and Fayolle and Gailly (Citation2015); Moberg et al. (Citation2014) reported that entrepreneurial education promotes a person to concern on a decent career path.

The third finding of the study showed that entrepreneurial education can influence students’ entrepreneurial preparation. This result is an agreement with a prior study by RezaeiZadeh et al. (Citation2017), which mentioned that entrepreneurial education plays a vital role in explaining students prepare for entrepreneurship. The result of this study is arguably due to the fact that entrepreneurial education does not only provides knowledge, attitudes, and character of an entrepreneur but also equips students with skills that are highly relevant for students in preparing for entrepreneurs. Indeed, this finding corroborates the currents studies by Tung et al. (Citation2020); Ni and Ye (Citation2018) on the critical role of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial preparation.

The fourth hypothesis is that entrepreneurial knowledge positively influences an entrepreneurial mindset. This study confirms the previous study by Cui et al. (Citation2019) that showed entrepreneurial knowledge is associated with students’ entrepreneurial mindset. Indeed, this result is relevant to the entrepreneurial human capital theory, which stated that individual level of knowledge is directly proportional to the high entrepreneurial mindset (Rashid, Citation2019). Additionally, Boldureanu et al. (Citation2020) noted that an entrepreneur’s knowledge capacity is needed for him/her to successfully run their business. Businesses are related to uncertainty, so entrepreneurs with their knowledge can plan various strategies. Our findings also reinforce the majority of similar studies that entrepreneurial knowledge influences the entrepreneurial mindset that ultimately creates startups and new business development (Ni & Ye, Citation2018).

In addition, the prior estimation confirmed that entrepreneurial knowledge influences prepare for an entrepreneur. This study is in line with an antecedent study by Coduras et al. (Citation2016) and Tung et al. (Citation2020) that entrepreneurship knowledge positively impacts the preparation for entrepreneurs. A possible explanation for this might be that prospective entrepreneurs who have entrepreneurial-related knowledge such as how to start a business, develop products or services that are good to meet the tastes and market demands, will have a high entrepreneurial intention, compared to those who do not have any at all. Furthermore, Ni and Ye (Citation2018); Boldureanu et al. (Citation2020) argued that entrepreneurs who have entrepreneurship knowledge and skills not only improve preparing for entrepreneurs but also the main capital when running their businesses.

The sixth hypothesis showed that entrepreneurial mindset positively influences prepare for entrepreneurs. This finding is relevant with significant results from some studies by Fayolle and Linan (Citation2014); Akmaliah et al. (Citation2016). The entrepreneurial mindset is a unique way of thinking about seeking opportunities instead of challenges, looking at chances rather than failures, and providing solutions to present a difference instead of complaining about problems (Walter & Block, Citation2016). Haynie et al. (Citation2010) also argue that the entrepreneurial mindset offers potential insights into the various outcomes and situations fundamental to preparing for entrepreneurs.

The last hypothesis is set out with the aim of assessing the importance of entrepreneurial knowledge in mediating entrepreneurial education and prepare for entrepreneurs. This result is consistent with the previous findings by Opoku-Antwi et al. (Citation2012); Walter and Block (Citation2016), that entrepreneurial education not only affects entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial intention but also prepares for entrepreneurs, both directly and indirectly. The result is also relevant to the findings of Turker and Selcuk (Citation2009); Remeikiene et al. (Citation2013) that entrepreneurial education not only offers useful knowledge about business startups but also contributes to the development of personal characteristics of entrepreneurs; therefore, the level of business startup for business students is increasing. Moreover, Tung et al. (Citation2020) showed that business knowledge influences preparing for entrepreneurs through changes in entrepreneurial knowledge, entrepreneurial mindset, and entrepreneurial. This finding also corroborates the findings of Klofsten (Citation2000), who remarked that entrepreneurial education improves students’ preparation for entrepreneurs.

5.1. Theoretical and practical implication

The findings of this study have both theoretical and future practices. First, the evidence of this study suggests that entrepreneurial knowledge encompasses the way of thinking, which affecting a positive mindset for entrepreneurship (Bosman, Citation2019). Additionally, entrepreneurial knowledge plays an essential role as a predictor and mediator in preparing new ventures (Tung et al., Citation2020). In addition to the theoretical practice, these findings recommend several practical implications for schools, government, and stakeholders. In terms of schools, the study findings suggest that entrepreneurship education in Indonesia should involve the updated materials relevant to the fourth industrial era. This matter will equip students with more excellent entrepreneurial knowledge and entrepreneurial mindset. Another important practical implication is that the entrepreneurship model using life-based learning (Yoto et al., Citation2019), such as inviting success stories of entrepreneurs or company visits, will enhance the students’ entrepreneurial mindset and intention being entrepreneurs. Schools also need to bring in successful entrepreneurs to share their various experiences, from pioneering to developing their businesses. For the government and stakeholders, the revitalization of entrepreneurship curricula in schools is needed to synergize and link business, education, and the industrial world. Lastly, the government and stakeholders need to become a mediator for school cooperation with the business and the industrial world. This becomes an effective way to control and contribute to the birth of new entrepreneurs from vocational schools.

6. Conclusion

This study examines the constellation between variables with seventh hypotheses, where all are accepted. Based on the results of hypothesis testing, we found that entrepreneurial education positively influences entrepreneurial knowledge (Tung et al., Citation2020), entrepreneurial mindset (Nowinski et al., Citation2019), and students’ entrepreneurial preparation (Ni and Ye (Citation2018). This finding also found that entrepreneurial knowledge positively influences the entrepreneurial mindset, prepares for entrepreneurs (Coduras et al., Citation2016), and mediates the impact of entrepreneurial education and prepares for entrepreneurs (Walter and Block (Citation2016). The latest finding is that entrepreneurial mindset positively influences preparing for entrepreneurs (Klofsten, Citation2000).

Based on these results, entrepreneurship education should be further improved due to the significant role in the readiness of young entrepreneurs from the formal education path. Since the increasing demand for entrepreneurs, entrepreneurship education needs to be propagated by practice and in collaboration with businesses, industries, and startups around the school (Gianiodis & Meek, Citation2020). The primary goal is to foster entrepreneurial knowledge, entrepreneurial mindset, entrepreneurial intention, and students prepare for entrepreneurs. Although data were collected in 30 vocational schools in Jakarta, the findings cannot be generalized to represent real conditions in all vocational schools in the city. This is because we only choose state schools, so future research needs to involve public and private SMK in DKI Jakarta so that research results are more diverse and generalizable. Additionally, the limitation of this study lies in using the solely quantitative method, which can be elaborated using a mixed-method and longitudinal model to provide a better understanding of entrepreneurial preparation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ari Saptono

Ari Saptono is an Associate professor specializing on educational assessment and entrepreneurship at Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. Agus Wibowo is an Assistant professor of entrepreneurship at Faculty of Economics Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. Bagus Shandy Narmaditya is a Lecturer at the Economic Education Program, Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Malang, Indonesia. Rr Ponco Dewi Karyaningsih is an Associate professor at Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Jakarta, Indonesia. Heri Yanto is an Associate professor at Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia.

References

- Akmaliah, Z., Pihie, L., & Arivayagan, K. (2016). Predictors of entrepreneurial mindset among university students. International Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, 3(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0307001

- Backström-Widjeskog, B. (2010). Teachers’ thoughts on entrepreneurship education. Creativity and innovation: Preconditions for entrepreneurial education, 107–120.

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fetap.12095

- Barba-Sanchez, V., & Atienza-Sahuquillo, C. (2018). Entrepreneurial intention among engineering students: The role of entrepreneurship education. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 24(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2017.04.001

- Barbosa, S. D., Kickul, J., & Smith, B. R. (2008). The road less intended: Integrating entrepreneurial cognition and risk in entrepreneurship education. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 16(4), 411–439. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495808000181

- Bazkiaei, H. A., Heng, L. H., Khan, N. U., Saufi, R. B. A., & Kasim, R. S. R. (2020). Do entrepreneurial education and big-five personality traits predict entrepreneurial intention among universities students? Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1801217. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1801217

- Bjørnskov, C., & Foss, N. J. (2008). Economic freedom and entrepreneurial activity: Some cross-country evidence. Public Choice, 134(3–4), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-007-9229-y

- Boldureanu, G., Ionescu, A. M., Bercu, A. M., Bedrule-Grigoruță, M. V., & Boldureanu, D. (2020). Entrepreneurship Education through successful entrepreneurial models in higher education institutions. Sustainability, 12(3), 1267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031267

- Bosman, L. (2019). From doing to thinking: Developing the entrepreneurial mindset through scaffold assignments and self-regulated learning reflection. Open Education Studies, 1(1), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1515/edu-2019-0007

- BPS. (2019). Keadaan Ketenagakerjaan Indonesia Agustus 2019. Badan Pusat Statistik.

- Chin, W., & Marcoulides, G. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–236). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Cho, Y. H., & Lee, J. H. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial education and performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-05-2018-0028

- Chrisman, J. J., & McMullan, W. E. (2002). Some additional comments on the sources and measurement of the benefits of small business assistance programs. Journal of Small Business Management, 40(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-627X.00037

- Coduras, A., Saiz-Alvarez, J. M., & Ruiz, J. (2016). Measuring readiness for entrepreneurship: An information tool proposal. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 1(2), 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.02.003

- Cui, J., Sun, J., & Bell, R. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. The International Journal of Management Education, 100296. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2019.04.001

- Davis, M. H., Hall, J. A., & Mayer, P. S. (2016). Developing a new measure of entrepreneurial mindset: Reliability, validity, and implications for practitioners. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 68(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000045

- Denanyoh, R., Adjei, K., & Nyemekye, G. E. (2015). Factors that impact on entrepreneurial intention of tertiary students in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 5(3), 19–29. https://thejournalofbusiness.org/index.php/site/article/view/693

- Dinis, A., Do Paço, A., Ferreira, J., Raposo, M., & Gouveia Rodrigues, R. (2013). Psychological characteristics and entrepreneurial intentions among secondary students. Education + Training, 55(8/9), 763–780. https://doi.org/10.1108/et-06-2013-0085

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12065

- Fayolle, A., & Linan, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 663–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.024

- George, G., & Bock, A. J. (2011). The business model in practice and its implications for entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 35(1), 83–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00424.x

- Ghina, A., Simatupang, T. M., & Gustomo, A. (2017). The relevancy of graduates’ competencies to the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education: A case study at SBM ITB-Indonesia. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 20(1), 1–24.

- Gianiodis, P. T., & Meek, W. R. (2020). Entrepreneurial education for the entrepreneurial university: A stakeholder perspective. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 45(4), 1167–1195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09742-z

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Harms, R. (2015). Self-regulated learning, team learning and project performance in entrepreneurship education: Learning in a lean startup environment. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 100, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.02.007

- Hasan, S. M., Khan, E. A., & Nabi, M. N. U. (2017). Entrepreneurial education at university level and entrepreneurship development. Education + Training, 59(7/8), 888–906. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-01-2016-0020

- Haynie, J. M., Shepherd, D., Mosakowski, E., & Earley, P. C. (2010). A situated metacognitive model of the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.001

- Hockerts, K. (2018). The effect of experiential social entrepreneurship education on intention formation in students. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 9(3), 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1498377

- Jena, R. K. (2020). Measuring the impact of business management Student’s attitude towards entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106275

- Jung, Y. S., & Jung, H. Y. (2018). The structural relationships among undergraduates’ individual characteristics, startup education, startup-relevant knowledge and the entrepreneurial intentions. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship, 13(6), 75–87. https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO201811562301707.mp;sp=3291

- Keat, O. Y., Selvarajah, C., & Meyer, D. (2011). Inclination towards entrepreneurship among university students: An empirical study of Malaysian university students. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(4), 206–220. http://www.ijbssnet.com/journals/Vol._2_No._4;_March_2011/24.pdf

- Klofsten, M. (2000). Training entrepreneurship at universities: A Swedish case. Journal of European Industrial Training, 24(6), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590010373325

- Larso, D., & Saphiranti, D. (2016). The role of creative courses in entrepreneurship education: A case study in Indonesia. International Journal of Business, 21(3), 216–225. https://www.craig.csufresno.edu/ijb/Volumes/Volume%2021/V213-3.pdf

- Mamun, A. A., Nawi, N. B. C., Mohiuddin, M., Shamsudin, S. F. F. B., & Fazal, S. A. (2017). Entrepreneurial intention and startup preparation: A study among business students in Malaysia. Journal of Education for Business, 92(6), 296–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2017.1365682

- Mathisen, J.-E., & Arnulf, J. K. (2013). Competing mindsets in entrepreneurship: The cost of doubt. The International Journal of Management Education, 11(3), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2013.03.003

- Moberg, K., Vestergaard, L., Fayolle, A., Redford, D., Cooney, T., Singer, S., ... & Filip, D. (2014). How to assess and evaluate the influence of entrepreneurship education: A report of the ASTEE project with a user guide to the tools

- Nabi, G., Linan, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 16, 277–299. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026

- Ni, H., & Ye, Y. (2018). Entrepreneurship education matters: Exploring secondary vocational school students’ entrepreneurial intention in China. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27(5), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0399-9

- Nowinski, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lancaric, D., Egerova, D., & Czegledi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1365359

- Olugbola, S. A. (2017). Exploring entrepreneurial readiness of youth and startup success components: Entrepreneurship training as a moderator. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 2(3), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.12.004

- Opoku-Antwi, G. L., Amofah, K., Nyamaah-Koffuor, K., & Yakubu, A. (2012). Entrepreneurial intention among senior high school students in the Sunyani Municipality. International Review of Management and Marketing, 2(4), 210–219. https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/irmm/article/view/250

- Patricia, P., & Silangen, C. (2016). The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention in Indonesia. DeReMa (Development Research of Management): Jurnal Manajemen, 11(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.19166/derema.v11i1.184

- Rashid, L. (2019). Entrepreneurship education and sustainable development goals: A literature review and a closer look at fragile states and technology-enabled approaches. Sustainability, 11(19), 5343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195343

- Rauch, A., & Hulsink, W. (2015). Putting entrepreneurship Education where the intention to Act lies: An investigation into the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial behavior. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 14(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0293

- Remeikiene, R., Dumciuviene, D., & Startiene, G. (2013). Explaining entrepreneurial intention of university students: The role of entrepreneurial education. In Active Citizenship by Knowledge Management & Innovation: Proceedings of the Management, Knowledge and Learning International Conference 2013 (pp. 299–307). ToKnowPress.

- RezaeiZadeh, M., Hogan, M., O’Reilly, J., Cunningham, J., & Murphy, E. (2017). Core entrepreneurial competencies and their interdependencies: Insights from a study of Irish and Iranian entrepreneurs, university students and academics. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(1), 35–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0390-y

- Rina, L., Murtini, W., & Indriayu, M. (2019). Entrepreneurship education: Is it important for middle school students? Dinamika Pendidikan, 14(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.15294/dp.v14i1.15126.

- Roxas, B. (2014). Effects of entrepreneurial knowledge on entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal study of selected South –east Asian business students. Journal of Education and Work, 27(4), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.760191.

- Ruiz, J., Soriano, D. R., & Coduras, A. (2016). Challenges in measuring readiness for entrepreneurship. Management Decision, 54(5), 1022–1046. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-07-2014-0493

- Saptono, A., Purwana, D., Wibowo, A., Wibowo, S. F., Mukhtar, S., Yanto, H., Utomo, S. H., & Kusumajanto, D. D. (2019). Assessing the university students’ entrepreneurial intention: Entrepreneurial education and creativity. Humanities and Social Sciences Reviews, 7(1), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2019.7158

- Sarooghi, H., Sunny, S., Hornsby, J., & Fernhaber, S. (2019). Design thinking and entrepreneurship education: Where are we, and what are the possibilities? Journal of Small Business Management, 57, 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12541

- Shepherd, D. A., Patzelt, H., & Haynie, J. M. (2010). Entrepreneurial Spirals: Deviation-Amplifying Loops of an Entrepreneurial Mindset and Organizational Culture. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 34(1), 59–82. doi:10.1111/etap.2010.34.issue-1

- Solesvik, M. Z., Westhead, P., Matlay, H., & Parsyak, V. N. (2013). Entrepreneurial assets and mindsets: Benefit from university entrepreneurship education investment. Education + Training, 55(8/9), 748–762. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2013-0075

- Syam, H., Akib, H., Patonangi, A. A., & Guntur, M. (2018). Principal entrepreneurship competence based on creativity and innovation in the context of learning organizations in Indonesia. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 21(3), 1–13.

- Tung, D. T., Hung, N. T., Phuong, N. T. C., Loan, N. T. T., & Chong, S. C. (2020). Enterprise development from students: The case of universities in Vietnam and the Philippines. International Journal of Management Education, 18(1), 100333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.100333

- Turker, D., & Selcuk, S. S. (2009). Which factors affect entrepreneurial intention of university students?. Journal of European industrial training, 33(2), 142–159. doi:10.1108/03090590910939049

- Turkina, E., & Thai, M. T. T. (2013). Social capital, networks, trust and immigrant entrepreneurship: A cross‐country analysis. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 7(2), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506201311325779

- Turner, T., & Gianiodis, P. (2018). Entrepreneurship unleashed: Understanding entrepreneurial education outside of the business school. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12365

- Utomo, H., Priyanto, S. H., Suharti, L., & Sasongko, G. (2019). Developing social entrepreneurship: A study of community perception in Indonesia. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7(1), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2019.7.1(18).

- Wahidmurni, W., Nur, M. A., Abdussakir, A., Mulyadi, M., & Baharuddin, B. (2019). Curriculum development design of entrepreneurship education: A case study on Indonesian higher education producing most startup funder. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 22(3), 1528–2651.

- Walter, S. G., & Block, J. H. (2016). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.10.003

- Wang, X., Zhang, Y., & Yang, J. (2012). Study on the mechanism between entrepreneurial human capital and new venture performance based on competence perspective. Management Review,24(4), 76–84

- Wibowo, S. F., Purwana, D., Wibowo, A., & Saptono, A. (2019). Determinants of entrepreneurial intention among millennial generation in emerging countries. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 23(2), 1–10.

- Winarno, A. (2016). Entrepreneurship education in vocational schools: Characteristics of teachers, schools and risk implementation of the curriculum 2013 in Indonesia. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(9), 122–127.

- Yoto, Y., Widiyanti, W., Solichin, S., & Tuwoso, T. (2019, January). Development of life-based teaching material on welding fields to form entrepreneurial characters. In 2nd International Conference on Vocational Education and Training (ICOVET 2018). Atlantis Press.