Abstract

Over recent years, pragmatic knowledge has been a major area of interest within the field of second language acquisition. Despite this, most studies available in the literature have only focused on testing and analyzing L2 learners’ knowledge of speech acts such as request and suggestion structures. However, pragmatic competence stretches beyond these structures to encompass more significant issues including conversational implicatures, a key element in interactional conversations. This paper seeks to remedy the problem by analyzing the effects of explicit vs. implicit instructions of implicatures on developing intermediate EFL learners’ pragmatic competence in a pre-test, post-test, and delayed-post-test equivalent-groups research design. The participants were 63 intermediate EFL learners randomly assigned into two experimental groups and a control group. The first experimental group received explicit instructions on conversational implicatures and the second one received implicit instructions. The results revealed that the explicit group outperformed the implicit group. Accordingly, explicit instruction had priority over implicit instruction leading to a significant increase in learners’ pragmatic competence development. The results also indicated that explicitly instructed materials enjoyed significantly greater chances of retention after a one-week delay.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Language is a special medium that enables humans to communicate appropriately and to achieve communicative goals effectively. However, in some conversational situations, speakers may step away from the intended purposes and say something that they do not mean literally, which is called conversational implicature. In such cases, listeners adopt some strategies to infer the real intention of the speakers. Thus, it is essential to provide learners of a new language with adequate and appropriate instructions to promote their communicative abilities and to enable them to become aware of what speakers are really willing to convey. In this study, we analyzed the effects of explicit vs. implicit instructions of conversational implicatures on developing intermediate English as a foreign language learners’ pragmatic competence. It was found that explicit instruction had priority over implicit instruction and led to a significant increase in learners’ pragmatic competence development.

1. Introduction

For many years, learning a second language was defined in terms of individuals’ mastery of grammatical and structural properties of a language. However, attentions have been recently directed towards the achievement of communicative, interactional abilities, and pragmatic competence (Kecskes, Citation2015; Qi & Lai, Citation2017; Ziafar, Citation2018) which is defined as “ … the ability to communicate appropriately in a social context. Learning how to use pragmatic features adequately in a particular setting is paramount for language users in order to achieve communicative purposes effectively.” (Beltrán-Planques & Querol-Julián, Citation2018, p. 80). Accordingly, pragmatic competence has to be fully developed if appropriate communication is the ultimate goal in a conversational setting. According to Ziafar (Citation2018), pragmatic competence also refers to the utilization of language (pragmalinguistics) in order to achieve conversational intentions in specific contexts (sociopragmatics). However, in some conversational situations, speakers may step away from the intended purposes and say something that they do not mean literally. In such cases, listeners are to adopt some strategies to infer the real intention of the speakers. The discrepancy between what is said and what is implied is a challenging subject that is given full consideration in Grice’s pragmatic theory (Grice, Citation1975). Furthermore, insufficient contextual knowledge or lack of awareness of social conventions, norms, and communicative patterns may lead an L2 learner to an impoverished understanding and incorrect inferencing in a particular communicative setting. Thus, it is essential to provide learners with adequate and appropriate instructions to promote their communicative and functional accuracy and to enable individuals to become aware of what speakers are really willing to convey. Additionally, lack of pragmatic knowledge and inferencing skills are salient causes of misunderstanding in everyday conversations.

Accordingly, many scholars and researchers have analyzed learners’ comprehension of the targeted conversational implicatures and have examined the role of pragmatic instruction in the processes of communication and interaction (Katsos & Bishop, Citation2011). On the other hand, a great number of studies have supported the indispensable impact of implicit and explicit instructions on the acquisition of pragmatic competence as well as conversational implicatures (e.g., Glaser, Citation2014; Kecskes, Citation2015; Qi & Lai, Citation2017; Taguchi & Yamaguchi, Citation2019; Ziafar, Citation2018). Additionally, appropriate instructions provided by instructors will help learners cope with probable difficulties they may face during interactional communications and will increase their pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic knowledge. In recent years, many studies have analyzed the effects of different types of instructional strategies and different types of corrective feedback in the development of pragmatic knowledge (Eslami-Rasekh, Citation2004; Da Silva & Jose, Citation2003; Yoshimi, Citation2001).

Studies have revealed that conversational implicatures, an integral part and a critical aspect of pragmatic competence (Taguchi & Yamaguchi, Citation2019), are one of the major sources of difficulty in students’ understanding of speakers’ intentions and opinions. Hence, conversational implicatures, as a form of contextualized inferences, have to be taken into consideration by teachers and learners.

Most studies available in the literature have only focused on testing and analyzing L2 learners’ knowledge of speech acts such as request and suggestion structures. However, pragmatic competence stretches beyond these structures and encompasses more significant issues including conversational implicatures, a key element in interactional conversations. Furthermore, from a methodological perspective, previous studies suffer from some frequently reported limitations such as lack of control group and delayed post-test assessment, and the use of self-report measures. In an attempt to remedy these drawbacks and to expand the scope of research in the realm of pragmatics research, this study aimed at investigating the effects of implicit and explicit interventionist instructions on comprehension of conversational implicatures among a sample of Iranian EFL learners.

1.1. Pragmatic competence

Pragmatic competence is a challenging concept that has been discussed by many different scholars. Morris (Citation1938) introduced the first scientific definition for pragmatics and referred to it as “the discipline that studies the relations of signs to interpreters, while semantics studies the relations of signs to the objects to which the signs are applicable” (p. 77). Crystal (Citation2008) also defines it as “the study of language from the point of view of users, especially of the choices they make, the constraints they encounter in using language in social interaction, and the effects their use of language has on the other participants in an act of communication” (p. 379). In other words, pragmatics is a scientific branch discussing how individuals use their languages in order to talk to and communicate with one another in various socio-cultural environments and consequently how they apply some strategies to interpret speakers’ utterances and expressions.

Hence, context as a multidimensional concept, including social, cognitive, cultural, linguistic, and non-linguistic factors is an indispensable element that plays an important role while individuals attempt to formulate and interpret linguistic expressions and meanings (Jaswal & Markman, Citation2001; Namaziandost, Razmi, Heidari, & Tilwani, Citation2020). Garcia (Citation2004) describes pragmatics “as a discipline focusing on the full complexity of social and individual human factors, latent psychological competencies, and linguistic features, expressions, and grammatical structures, while maintaining language within the context in which it was used” (p. 8).

Studies have also revealed that socio-cultural awareness is one of the most important elements leading to learners’ understanding, comprehension, and effective meaning interpretation (Taguchi, Citation2012). In other words, pragmatic growth is defined in terms of learners’ knowledge of linguistics, socio-cultural matters and discourse. In a similar vein, Van Dijk (Citation1977) highlighted two key processes of context analysis and utterance analysis in the theory of pragmatic comprehension and proposed that if accurate comprehension is the priority and if learners are intended to have appropriate interpretation of speakers’ intention, feeling, and attitude, they need to develop awareness of not only the societal rules, conventions, and physical setting, but also of the structural properties of an utterance.

1.2. Conversational implicatures

Conversational implicatures, interpreted as context dependent and non-truth conditional concepts (Briner, Citation2012), are considered to be one of the key issues in the field of pragmatic competence and conversation analysis (Safont, Citation2005; Salazar, Citation2003; Wishnoff, Citation2000). This concept is defined by Oxford dictionary (Crystal, Citation2008) as “The action of implying a meaning beyond the literal sense of what is explicitly stated.”. However, learners have been found to experience difficulty while comprehending implicatures and their hidden meanings. Hence, many studies have focused on the importance of learner’s pragmatic comprehension and their abilities to draw some inferences about the conversational utterances. Grice (Citation1975) was the first who introduced the term implicature as a kind of conversational concept and interpreted it as something a speaker has in his/her mind and implies it in a non-literal way. He also made a distinction between generalized implicatures and conversational implicatures:

Conversational implicatures depend on particular contextual features …. And generalized implicatures … that seem to be more controversial and at the same time more valuable for philosophical purposes, because they will be implicatures that would be carried by an utterance of a certain form, though, as with all implicatures, they are not to be represented as part of the conventional meaning of the words or forms in question. (Grice, Citation1981, p. 185)

Grice (Citation1975) proposed the idea that while audiences are able to equate speakers’ articulations with the exact meanings of linguistic expressions and phrases embedded in the utterances, the idea of standard interpretation is fulfilled. Based on this idea, he proposed the prominent theory of cooperative principle that has been a promising avenue in pragmatics research. He argues that cooperation is a necessary interactional element. While people are communicating with clear purposes, they use some principles to draw sound inferences and to make valid interpretations. During this process, they pay attention to different contextual clues and apply their own past experiences and knowledge. Gricean cooperative principle is based on four conversational maxims. These maxims are as follows:

Maxim of Quality: Be truthful. Not to say false or incorrect matters.

Maxim of Quantity: Be as informative as possible. Not to say unnecessary information

Maxim of Relation: Be relevant.

Maxim of Manner: Avoid ambiguity. Be clear, brief, and orderly.

Grice (Citation1975) adds “Make your conversational contribution such as required at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk of exchange in which you are engaged” (p. 41). However, under some conditions, Gricean Maxims are not always present and one or some of them may be absent during an interactional communication. In fact, sometimes, speakers may deliberately avoid using some maxims in their utterances (Darighgoftar & Ghaffari, Citation2012). Mey (Citation2001) refers to this condition and clarifies that “good authors have always something up their sleeves, and may allow themselves deliberate omissions, misleading statements, uninformative or dis-informative remarks and all sorts of narrative tricks in order to better develop the plot” (p. 78).

Communication and appropriate interaction are the main building blocks of human life. To convey ideas and opinions, to express wants and needs and to develop social relationships, individuals follow different conversational patterns and procedures including cooperative principles. However, as explained by Grice (Citation1975), sometimes these cooperative principles are not fulfilled by the individuals, specifically when the speakers intend to convey their intentions indirectly or aim to persuade listeners to draw some inferences from their utterances. For instance, while somebody tells a joke, writes a book, makes a movie or is engaged in politeness situations, he/she may violate or flout one or several maxims in order to persuade individuals and leave an effective impression on them (Sobhani & Saghebi, Citation2014). It is worth noting that scholars have drawn a line between flouting a maxim and violating it.

Despite engaging in cooperative conversations, individual may sometimes prefer not to obey the rules. The refusal to observe or to follow the maxims in a standard conversation as an intentional act is called non-observance of maxims or breaking maxims (Agustina & Ariyanti, Citation2016; Dornerus, Citation2005). Grice (Citation1975) proposed five ways of breaking a maxim:

Flouting maxims: under this condition, the speaker attempts to draw the interlocutor’s attention to the conversational implicature and to the meanings which are not literally or directly stated in their utterances (Agustina & Ariyanti, Citation2016).

Violating maxims: In this case, the speaker is determined to mislead and deceive the listener and sometimes to persuade him/her to do/not to do certain acts and behaviors or to make certain decisions (Dornerus, Citation2005; Thomas, Citation2014).

Opting out of a maxim: In this case, the speaker decides not to use one or several maxims. In fact, the speaker is reluctant to give requested information (Thomas, Citation2014).

Infringing: Due to cognitive impairments or the lack of effective communication skills, sometimes speakers unintentionally fail to observe a maxim. Under such conditions, it is said that they infringe the maxims (Thomas, Citation2014).

Suspending: Sometimes the speaker does not express all necessary requested information. In fact, he/she suspends a maxim because of some cultural issue, prohibitions or taboos (Thomas, Citation2014).

2. Review of literature

The importance of teaching pragmatics to language learners is discussed and highlighted by many scholars and prominent researchers (Bardovi-Harlig, Citation2001; Norris & Ortega, Citation2000; Trosborg, Citation2003; Yoshimi, Citation2001). Pragmatics, known as a social language, refers to learner’s ability to communicate effectively and appropriately with different people in different contexts. Accordingly, linguistic competence alone does not guarantee that learners are communicatively competent and are capable enough to interact, comprehend, and convey intended ideas. According to Crandall and Basturkmen (Citation2004), “a learner of high grammatical proficiency will not necessarily show concomitant pragmatic competence—a real concern given that people are more forgiving; it seems, of grammatical mistakes than of pragmatic failure” (p. 41). Previous studies have highlighted the explicit–implicit dichotomy and have provided evidence for the effects of explicit and implicit instructional techniques on learners’ pragmatic knowledge.

Kaburise (Citation2014), in a study, discussed the effect of explicit and implicit classroom instruction on African students’ pragmatic ability. Kaburise maintained that helping learners to develop their pragmatic competence should not be ascribed to priority of one instructional strategy over the other. Both explicit and implicit instructional strategies play principal roles in the process of learners’ progress. They have to be regarded as two sides of a continuum. At the beginning, learners should be provided with explicit instruction, adequate explanations, and clarifications and then they may be gradually engaged in implicit procedures and activities. Also, learners should be encouraged to engage in meaningful conversational interactions. This continuum opens a window through which we can see learners’ pragmatic development and communicative competence.

In a similar vein, Khatib and Baqerzadeh Hosseini (Citation2015) conducted a quantitative study of pragmatics, investigating how explicit and implicit teaching will influence learners’ production of speech acts. To this end, 80 EFL learners were assigned into 4 experimental groups. Results on a pretest and posttest revealed that although both metapragmatic explanation and input enhancement had positive effects on the individuals’ pragmatic competence, explicit instruction had superiority over the implicit one.

To analyze the effect of focus on form (implicit) vs. focus on forms (explicit) pragmatic instruction techniques on the development of pragmatic comprehension and production, Rafieyan (Citation2016) conducted an experimental study on 52 undergraduate students of English. Students were assigned into two experimental groups, each of them receiving explicit or implicit instruction. Assessment of designed completion tasks and multiple-choice pragmatic comprehension tests indicated that although both types of instructional strategies led to pragmatic development, the group whose members received metapragmatic explanations and focus on forms instructional strategies outperformed the group with focus on form teaching strategies. The fact is that pragmatic knowledge has often been limited to testing L2 learners’ knowledge of speech acts. However, pragmatic competence stretches beyond speech acts to encompass more issues such as pragmatic functions, and non-literal meanings like implicatures and their related cultural elements.

Nonetheless, Kubota (Citation1995) was among the first who studied the teachability of conversational implicatures and suggested that teachers should be aware of the fact that explicit instruction and consciousness raising tasks play significant roles in the process of pragmatic development. According to Kubota, exposure to pragmatic examples, input, and knowledge can help students learn pragmatic cues and implicatures.

Analyzing the effect of explicit and implicit instructional approaches, Schmidt (Citation1990) highlighted the facilitative role of noticing in adult learners of a second language. Schmidt proposed the noticing hypothesis and stated that “subliminal language learning is impossible, and that noticing is the necessary and sufficient condition for converting input to intake” (p. 129).

In line with the above arguments, two basic approaches are introduced in the field of second language teaching. These two approaches are related to the implicit and explicit instructional strategies. Ellis (Citation1994) makes a distinction between implicit/explicit dimensions. Implicit learning is the “acquisition of knowledge about the underlying structure of a complex stimulus environment by a process which takes place naturally, simply and without conscious operations.” (p. 1). On the contrary, explicit instruction is a “conscious process where the student’s attention is focused on specific items/patterns and they are engaged in making and testing hypothesis” (Ellis, Citation1994, p. 3).

An analysis of the empirical studies shows that there has been a lot of controversy over the effectiveness and priority of either of these two approaches. On one hand, many researchers believe that if learners desire to be fluent and accurate in their production and comprehension, they have to pay attention to different properties of the target language (Schmidt, Citation1990). On the other hand, others argue that language learning is an unconscious process and learning takes place without learners’ attention or awareness (Seliger, Citation1979). Taken together, Bowles (Citation2011) suggests that implicit knowledge involves automatic processing and is more structured than explicit knowledge which entails controlled processing and learners are more confident when their arguments, judgments, and understandings are based on implicit knowledge.

2.1. Research questions and hypothesis

Considering the above-mentioned ideas and literature, the following questions were addressed in the present study:

Q1) which type of interventionist instruction (explicit or implicit instruction) leads to better understanding of conversational implicatures?

It was hypothesized that there is no statistically significant difference between explicit and implicit instructional strategies.

Q2) Do the students retain instructed materials after one week?

It was hypothesized that intermediate EFL learners would forget instructed materials after one week.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Participants

A group of 63 intermediate level female students, ranging in age from 17 to 21 years (M = 18.96, SD = 1.35), studying English at a language institute in Yazd were selected based on the availability of students and their level of proficiency. To ensure the homogeneity of the groups, a Quick Oxford Placement Test (QOPT) was given to the participants at the beginning of the research. The results of the placement test are summarized in Table . The participants were then assigned to three groups according to their level of general L2 proficiency, age, and the pre-test scores to receive different types of instructions on conversational implicatures. The groups and the nature of the instructions are discussed below.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the participants

3.2. Instruments

As mentioned above, prior to data collection, the participants were given the QOPT. The group assignment was based on the proficiency level screening. Accordingly, the three groups in this study were not different in terms of level of proficiency, F (2, 60) = .054, p > .05. To factor out any age-related effects, the researchers also ensured there were no statistically significant age differences among the three groups, F (2, 60) = .571, p > .05. the descriptive statistics of the participants are presented in Table .

The researchers developed a 20-item test to gather data on identification of conversational implicatures (Appendix A). First, conversations and listening activities presented in each unit of students’ textbook were carefully analyzed and appropriate implicatures were extracted. To validate the researcher-developed test, the measure was e-mailed to 7 university professors specializing in pragmatics in second language research in Iran. All 7 professors had published at least one original article in a top-tier journal related to pragmatics research. Five professors replied and confirmed the validity of the instrument. We did not receive e-mails from the remaining 2 experts. The experts were provided with an acceptability judgment form to score each item. The form was a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 where 1 represented very low level of acceptability and 5 denoted very high acceptability level (1 = totally unacceptable, 2 = unacceptable, 3 = undecided, 4 = acceptable, 5 = highly acceptable). To demonstrate consistency among observational ratings provided by 5 coders, Fleiss’ Kappa was conducted. The overall Kappa estimate was .61 which indicates a substantial level of inter-rater reliability (O’Neill, Citation2017). The average acceptability scores for all the items were 4 or higher except for the item 18 which was 3.60. The grand mean obtained for all items was 4.68 (Min = 3.60, Max = 5). The Chronbach’s Alpha was found to be .70 for the 20-item instrument scored by 5 raters. The resulting 20-item test confirmed by experts was used to gather data in pre-test, post-test, and delayed post-test sessions.

3.3. Procedures

This study focused on the effect of both explicit and implicit interventionist instructions on learners’ understanding of conversational implicatures and aimed at describing how each of these strategies would result in better comprehension. Based on the treatment conditions, participants were assigned into two experimental groups and one control group. Each group received different types of instructions as follows:

E. Group 1: Interventionist Explicit Teaching

E. Group 2: Interventionist Implicit Teaching

C. Group: No treatments were assigned

Before beginning the treatment, students were given the pre-test (see Appendix A). The same test was used to gather data in post and delayed post-test assessments. During the test, students were asked to read some conversations between two persons and to recognize the exact hidden meanings of some implicatures and to identify the speakers’ intentions. The purpose of the administration of this test was to make sure that learners had no prior experience in learning implicatures and to ascertain the learners were neither familiar with conversational implicatures nor able to make correct inferences or to understand speakers’ intentions clearly. There were not statistically significant differences among the three groups concerning the pre-test scores, F (2, 60) = 1.75, p > .05. The results of the pre-test scores as well as the descriptive statistics are summarized in Table .

Having implemented the proficiency screening, pre-test, and group assignment, the instructor began the treatment process by presenting different types of instructions for each group as follows:

3.3.1. E. Group 1: interventionist explicit teaching

At the beginning, some listening conversations were played for the students and separate handouts including conversational implicatures were given to them. Handouts also included some explanations and practices and had to be returned after each treatment session. Then the instructor described the pedagogical goals of the lesson, clarified her expectations, and discussed important issues of interest including cooperative principles, conversation maxims, and communicative patterns in an explicit way. Students’ questions were also answered. Then each conversation was read by the teacher and their hidden and indirect meanings were explained to the students. Some multiple-choice questions were also given to the individuals for which respondents were asked to select the options in which speakers’ intention were clearly and accurately explained. In the event of participants’ request, Persian translation of implicatures or conversational phrases were also discussed.

3.3.2. E. Group 2: interventionist implicit teaching

During the instruction process, while individuals were not aware of the lesson objectives, some listening conversations were played and separate handouts were given to them. Then, based on the presented listening parts, students were asked to answer some multiple-choice and comprehension-based questions. Students’ incorrect choices and answers were then corrected. In these questions, respondents had to choose the options and provide answers that would reflect speakers’ ideas and their true intention in a best and most proper way. Although students were not provided with explicit explanations, adequate range of examples and practices were included in their handouts.

3.3.3. C. Group: no treatments were assigned

The members of this group were not provided with any kind of treatment. However, they took the pretest, post-test, and the delayed post-test.

3.4. Data collection

This study was conducted in a pre-test, post-test, and delayed-post-test design. The same test was administered for the three assessments (Appendix A). The two types of instructional strategies were assigned as the independent variables and students’ pragmatic competence was considered as the dependent one. After the immediate post-test, students were left on their own for one-week period. Then, the delayed post-test was given to see whether the students could retain the instructed information and if materials were forgotten over a period.

4. Results

4.1. The investigation of the first null hypothesis

Concerning the first research question, a null hypothesis was made stating that there is not a significant difference between explicit and implicit instructional strategies, while students are exposed to conversational implicatures. Therefore, an immediate post-test was designed and related data were obtained and analyzed. A one-way between-groups analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was utilized to explore the effectiveness of two teaching approaches in EFL learners’ use of implicatures.

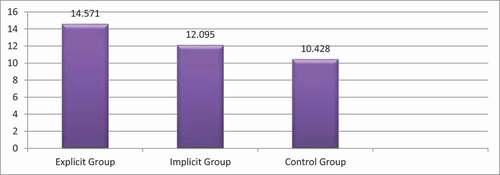

The independent variable was instruction type (explicit, implicit, and control group). The dependent variable was scores on immediate post-test administered following the completion of the interventions. Pre-test Scores on the implicature and QOPT scores were used as covariates to control for individual differences in implicature use and language proficiency. Before conducting the ANCOVA, assumptions of normality, linearity, homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test, p = .962) as well as independence of the covariate and treatment effect (pre-test covariate: F (2, 60) = 1.752, p = .182, and QOPT covariate: F (2, 60) = .054, p = .948), and homogeneity of regression slopes were probed. The results did not show any violation of the assumptions. The descriptive statistics of the immediate post–test and the graphical illustration are indicated in Table and Figure .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the participants’ scores on immediate post-test

The ANCOVA results indicated that the pre-test covariate was not significantly related to participants’ immediate post-test scores F (1, 58) = .379, p > .05, r = −.05, partial η2 = .006. Conversely, the QOPT covariate was significantly related to the participant’s post-test scores, F (1, 58) = 100.82, p < .01, r = .56, partial η2 = .63. There was also a significant effect of group membership on the use of implicatures after controlling for the effects of pre-test and proficiency covariates, F (2, 58) = 74.24, p < .01, partial η2 = .72.

Planned contrasts revealed that explicit instruction significantly increased the use of implicature compared to no instruction in control group, t (58) = 12.10, p < .01, and the implicit instruction, t (58) = 2.49, p < .01. Additionally, the implicit instruction significantly increased the post-test scores compared to the instruction presented in control group t (58) = 5.01, p < .01.

Based on the above analysis, both types of instructional strategies were effective. In fact, the treatment groups outperformed the control group. Results also proved that explicit instruction was more effective than the implicit one and helped learners perform better in immediate post-test. In other words, there is a significant difference among the performance of explicit, implicit, and the control groups.

4.2. The investigation of the second null hypothesis

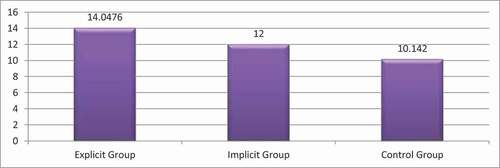

The second hypothesis stated that the intermediate EFL learners would forget instructed materials after 1 week. A one-way between-groups ANCOVA was used to probe the second hypothesis related to the delayed post-test scores. The descriptive statistics of the scores on delayed post-test are shown in Table and Figure . Prior to the ANCOVA, assumptions of normality, linearity, homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test, p = .491) as well as independence of the covariate and treatment effect (pre-test covariate: F (2, 60) = 1.752, p = .182, and QOPT covariate: F (2, 60) = .054, p = .948), and homogeneity of regression slopes were investigated. No violation of assumptions was observed.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the participants’ scores on delayed post-test

The ANCOVA results revealed that the pre-test covariate was not significantly related to participants’ delayed post-test scores F (1, 58) = .151, p > .05, r = .11, partial η2 = .035. However, the QOPT covariate was significantly related to the participant’s delayed post-test scores, F (1, 58) = 47.17, p < .01, r = .44, partial η2 = .45. There was also a significant effect of group membership on the use of implicatures after controlling for the effects of pre-test and proficiency covariates, F (2, 58) = 48.68, p < .01, partial η2 = .63.

Planned contrasts revealed that explicit instruction significantly increased the use of implicature compared to no instruction in control group, t (58) = 9.84, p < .01, and the implicit instruction, t (58) = 3.95, p < .01. Additionally, the implicit instruction significantly increased the post-test scores compared to the instruction presented in control group t (58) = 4.38, p < .01.

In sum, the analyses revealed that there exist significant differences among the performances of the three groups after controlling for the effects of pre-test and proficiency covariates. In fact, learners who received explicit instruction had not forgotten instructed materials after 1 week. In other words, in case of implicatures learning, the effect of explicit instruction lasted for a long time and instructed information had not faded away after a one-week interval.

5. Discussion

With respect to the first research question, the first hypothesis stated that that there is not a statistically significant difference between the performance of those who received explicit instruction and those who received implicit one. In order to test this hypothesis, scores of the three groups were analyzed. Results indicated that the groups obtained significantly different mean scores (EG: 14.57; IG:12.09; CG: 10.42) and had performed differently in the immediate post-test.

It was revealed that those who were provided with explicit instruction had better performance than those who had implicit instruction. Additionally, the ANCOVA and variable contrasts revealed that although both experimental groups outperformed the control group, explicit teaching was more effective than the implicit one while individuals were intended to learn about implicatures.

Accordingly, based on the above information and in line with many previous studies (Ghobadi & Fahim, Citation2009; Khatib & Baqerzadeh Hosseini, Citation2015; Kia & Salehi, Citation2013; Salemi et al., Citation2012; Takahashi, Citation2001a & Citation2001b) that have analyzed the effects of different types of instructional strategies, it is proved that both types of instructional strategies help learners enhance their pragmatic competence and understand conversational implicatures correctly. This finding, however, is in contrast with the one reported by Ziafar (Citation2018). Ziafar acknowledges that the mainstream research is in favor of explicit instruction of implicatures, while his findings run contrary to majority of the research reported in the literature. In the present investigation, learners had better performance on the post-test compared to the scores obtained on pre-test session. In other words, although both types of explicit and implicit instruction had significant effects on learners’ comprehension and understanding of implicatures, explicit instruction had a more significant effect on Iranian EFL learners’ pragmatic understanding. In fact, with regard to the mastery of conversational implicatures, explicit instruction has superiority over implicit instruction.

To address the second question and to analyze the second hypothesis, a delayed post-test was designed to analyze students’ performances after 1 week of instruction and obtained scores of the three groups were statistically analyzed. The results of the test manifested that students of each group had performed differently from one another (EG:14.74; IG:12.00; CG: 10.14). The ANCOVA test also indicated that there were statistically significant differences among the three groups regarding the performance on the conversational implicatures. In other words, students who were provided with explicit or implicit instructional strategies had not forgotten the materials. However, the explicit instruction was more effective than the implicit one and the learners provided with explicit explanations and adequate range of examples and activities could retain instructed materials for longer period of time.

In the present study, general language proficiency was found to be a determining factor in the participants’ understanding of conversational implicatures. This effect was evident in the analyses of both hypotheses discussed above. This finding echoes the impact of level of proficiency in detection of conversational implicatures reported by Ziafar (Citation2018).

Conversation and interactional communication are the building blocks of pragmatics known as a social language. In line with the findings of this study, in a dynamic environment, individuals interact in an appropriate and purposeful communicative setting to share information, to gain support, and to make their intended impressions (Beltrán-Planques & Querol-Julián, Citation2018). Additionally, as confirmed by our data, speakers could be instructed explicitly to follow certain patterns and produce utterances that are clear, relevant, and truthful. During this process, interlocutors have to pay attention to different physical, contextual, and nonverbal clues, and if necessary, ask for some clarifications and some inferences. However, sometimes the speakers implicate their ideas and express their main intention in a persuasive way. In fact, what they mean is completely different from what they literarily express. In this case, learners meet some pragmatic difficulties and may not be able to communicate in an appropriate, goal-oriented direction. Therefore, implicatures are not explicitly stated, and this calls for application of implicit instructions to help EFL learners promote their awareness of conversational implicatures (Taguchi & Yamaguchi, Citation2019). Accordingly, both explicit and implicit instruction can benefit the learners in identification of implicatures. As Kaburise (Citation2014) maintains, these two types of instructions operate as two ends of a continuum, and learners in the beginning levels of language learning should be provided with explicit instructions and as they become more proficient in language use and raise awareness of implied information communicated in conversational interactions, they may be presented with implicit instructions. Since the participants in our study were at an intermediate level of proficiency, we believe the significant effect of explicit instruction over implicit can be partly due to the participants’ level of proficiency. Another interesting line of this study acknowledges that pragmatic competence must be conceived of as a complex construct that stretches beyond speech acts and encompasses more challenging issues such as pragmatic functions, non-literal meanings, and conversational implicatures as well as their situated cultural elements.

6. Conclusion

This study analyzed the effect of two interventionist instructional strategies; explicit and implicit instruction on learners’ pragmatic competence and development in one of the most significant conversational concepts, conversational implicatures. It was indicated that explicit instruction favors Iranian intermediate learners better than the implicit one when the learners are involved in conversational interactions. It was also revealed that experimental group receiving explicit instruction out-performed the implicit instruction group in the identification of conversational implicatures. Another line of the findings in this study showed that consciousness-raising tasks which were employed by the teacher led to deeper understanding on the part of the learners and improved their performance. This study revealed that meta-pragmatic explanations and consciousness raising tasks, provided by the teacher during the course of instruction, were effective in leading learners to comprehend implicatures and understand speakers’ intentions appropriately.

Our findings come with instructional implications, too. According to Alcon (Citation2007), classroom as one of the most effective learning environments helps learners go through different developmental stages and raises students’ awareness of pragmatic abilities. In this environment, by acknowledging students’ needs, learning styles, and personality factors, the instructor is responsible to attract learners’ attention to necessary materials and to keep them motivated in the classroom (Razmi, Jabbari, & Fazilatfar,Citation2020). For this reason, teachers are expected to employ different types of instructional strategies to improve learners’ pragmatic competence and make them familiar with relevant principles and concepts. In order to provide the learners with appropriate instructions on the use of implicatures, teachers need to develop their understanding of pragmatic competence. Teacher educators can play a significant role by giving explicit instruction about areas of pragmatics to assist the teachers in professional development and pragmatic awareness (Vásquez & Sharpless, Citation2009).

Due to some limitations, the findings of the present study must be interpreted with caution. First, there were limitations concerning the sample. The small-scale sample size is insufficient to make reliable generalizations. Further exploration is required to investigate the findings with a larger sample size. Moreover, all participants were intermediate-level institute learners. It deserves further research to test whether the same finding would apply to learners of different L2 proficiency levels. Second, since this study was experimental in nature, it did not utilize qualitative approaches to collect data. Future research should adopt multiple qualitative and quantitative measures to enhance the validity of the findings. Third, the administration of the same test for pre, post, and delayed tests makes the assessments vulnerable to practice effect. The assessment of parallel reliable measures is recommended to cope with this limitation. Finally, the findings of the study were based on the scores on teacher-made instrumentation that are decontextualized non-real-life measures (Taguchi & Yamaguchi, Citation2019). Future research should expand and enhance the instrumentation methods to apply real-life measures in assessing the L2 implicatures.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors confirm that the ideas expressed in the submitted article are their own and not those of an official position of the institution or funder.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shamila Ziashahabi

Shamila Ziashahabi is a PhD student at Yazd University, Iran. Her areas of interest are pragmatics, discourse analysis, and conversation analysis.

Ali Akbar Jabbari

Ali Akbar Jabbari is an associate professor in the Department of Foreign Languages at Yazd University, Yazd, Iran. He is currently the head of the Faculty of Foreign Languages. He received his PhD in second language acquisition from Durham University, UK. His research interest is second and third language acquisition. He has published articles in top-tier international journals.

Mohammad Hasan Razmi

Mohammad Hasan Razmi is a PhD candidate at Yazd University. His areas of interest are psycholinguistics and discourse analysis. He has published articles in Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, International Journal of Psychology, Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, and Iranian EFL Journal.

References

- Agustina, M., & Ariyanti, L. (2016). Flouting maxim to create humor in movie This Means War. Language Horison, 4(2), 38–20. https://jurnalmahasiswa.unesa.ac.id/index.php/language-horizon/article/viewFile/14950/13525

- Alcon, E. (2007). Incidental focus on form, noticing and vocabulary learning in EFL classroom. International Journal of English Studies, 7, 41–60. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1072187.pdf

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2001). Evaluating the empirical evidence: Grounds for instruction in pragmatics? In K. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.), Pragmatics in language teaching (pp. 13–32). Cambridge University Press.

- Beltrán-Planques, V., & Querol-Julián, M. (2018). English language learners’ spoken interaction: What a multimodal perspective reveals about pragmatic competence. System, 77, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.01.008

- Bowles, M. (2011). Measuring implicit and explicit linguistic knowledge: What can heritage language learners contribute? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 33(2), 247–271. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263110000756

- Briner, B. J. (2012). Introduction to pragmatics. Wiley Blackwell.

- Crandall, E., & Basturkmen, H. (2004). Evaluating pragmatics-focused materials. ELT Journal, 58(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/58.1.38

- Crystal, D. (2008). A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics (6th ed.). Blackwell Publishing.

- Da Silva, B., & Jose, A. (2003). The effect of instruction on pragmatic development: Teaching polite refusal in English. Second Language Studies, 22(1), 55–106. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/40659/Bacelar%20de%20Silva%20%282003%29_WP22%281%29.pdf

- Darighgoftar, S., & Ghaffari, F. (2012). Different homeopathic characters violate cooperative principles differently. International Journal of Linguistics, 4(3), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v4i3.1932

- Dornerus, E. (2005). Breaking maxim in conversation: A comparative study of how scriptwriters break maxims in Desperate Housewives and That 70th Show. Unpublished Postgraduate Dissertation. Karlstad Universteit.

- Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

- Eslami-Rasekh, Z. (2004). Face keeping strategies in reaction to complaints: English and Persian. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 14(1), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1075/japc.14.1.11esl

- Garcia, P. (2004). Meaning in academic contexts: A corpus-based study of pragmatic utterances [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Northern Arizona University.

- Ghobadi, A., & Fahim, M. (2009). The effect of explicit and implicit teaching of English thanking formulas‖ on Iranian EFL intermediate level students at English language institutes. System, 37(3), 526–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2009.02.010

- Glaser, K. (2014). Inductive or deductive? The impact of method of instruction on the acquisition of pragmatic competence in EFL. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. In P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and semantics, volume 3: Speech acts (pp. 41–58). Academic Press.

- Grice, H. P. (1981). Presupposition and conversational implicature. In P. Cole Ed., Radical pragmatics (pp. 183–197). Academic Press. (Reprinted in Grice (1989), pp. 269-82.).

- Jaswal, V. K., & Markman, E. M. (2001). Learning proper and common names in inferential versus ostensive contexts. Child Development, 72(3), 768–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00314

- Kaburise, P. (2014). Using explicit and implicit instruction to develop pragmatic ability in non-urban classrooms in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(23), 1235–1241. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3fd4/e499e83c0924dec6b4228eed0407b7b99f89.pdf

- Katsos, N., & Bishop, D. (2011). Pragmatic tolerance: Implications for the acquisition of informativeness and implicature. Cognition, 120(1), 67–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2011.02.015

- Kecskes, I. (2015). How does pragmatic competence develop in bilinguals? International Journal of Multilingualism, 12(4), 419–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2015.1071018

- Khatib, M., & Baqerzadeh Hosseini, M. (2015). The effect of explicit and implicit instruction through plays on EFL learners’ speech act production. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 18(2), 109–140. https://doi.org/10.18869/acadpub.ijal.18.2.109

- Kia, E., & Salehi, M. (2013). The Effect of explicit and implicit instruction of English thanking and complimenting formulas on developing pragmatic competence of Iranian EFL upper-intermediate level learners. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 3(8), 202–215. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282780145_The_Effect_of_Explicit_and_Implicit_Instruction_of_English_Thanking_and_Complimenting_Formulas_on_Developing_Pragmatic_Competence_of_Iranian_EFL_Upper-Intermediate_Level_learners

- Kubota, M. (1995). Teachability of conversational implicature to Japanese EFL learners. Institute for Research in Language Teaching Bulletin, 9, 35–67. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234561388_Teachability_of_Conversational_Implicature_to_Japanese_EFL_Learners

- Mey, J. (2001). Pragmatics: An Introduction. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

- Morris, C. (1938). Foundations of the theory of signs. In O. Neurath, R. Carnap, & C. Morris (Eds.), International encyclopedia of unified science (pp. 77–138). University of Chicago Press.

- Namaziandost, E., Razmi, M. H., Heidari, S., & Tilwani, S. A. (2020). A contrastive analysis of emotional terms in bed-night stories across two languages: Does itaffect learners' pragmatic knowledge of controlling emotions? Seeking implications to teach English to EFL learners. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09739–y d

- Norris, J., & Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative metaanalysis. Language Learning, 50(3), 417–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.00136

- O’Neill, T. A. (2017). An overview of interrater agreement on Likert scales for researchers and practitioners. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00777

- Qi, X., & Lai, C. (2017). The effects of deductive instruction and inductive instruction on learners’ development of pragmatic competence in the teaching of Chinese as a second language. System, 70, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.08.011

- Rafieyan, V. (2016). Effect of focus on form versus focus on forms pragmatic instruction on development of pragmatic comprehension and production. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(20), 41–48. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305735302_Effect_of_'Focus_on_Form'_versus_'Focus_on_Forms'_Pragmatic_Instruction_on_Development_of_Pragmatic_Comprehension_and_Production

- Razmi, M. H., Jabbari, A. A., & Fazilatfar, A. M. (2020). Perfectionism, self-efficacy components, and metacognitive listening strategy use: A multicategorical multiple mediation analysis. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. doi:10.1007/s10936-020-09733-4

- Safont, M. P. (2005). Third language learners: Pragmatic production and awareness. Multilingual Matters.

- Salazar, P. C. (2003). Pragmatic instruction in the EFL context. In A. Martinez-Flor, E. Uso, & A. Fernandez (Eds.), Pragmatic competence and foreign language teaching (pp. 233–246). Servei de Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I.

- Salemi, A., Rabiee, M., & Ketabi, S. (2012). The effects of explicit/implicit instruction and feedback on the development of Persian EFL learners’ pragmatic competence in suggestion structures. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 3(1), 188–199. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.3.1.188-199

- Schmidt, R. (1990). The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 129–158. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/11.2.129

- Seliger, H. (1979). On the nature and function of language rules in language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 13(3), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.2307/3585883

- Sobhani, A., & Saghebi, A. (2014). The violation of cooperative principles and four maxims in Iranian psychological consultation. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics, 4(1), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2014.41009

- Taguchi, N. (2012). Context, individual differences, and pragmatic competence. Multilingual Matters.

- Taguchi, N., & Yamaguchi, S. (2019). Implicature comprehension in L2 pragmatics research. In N. Taguchi (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and pragmatics (pp. 31–46). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Takahashi, S. (2001a). Explicit and implicit instruction of L2 complex request forms. In P. Robinson, M. Sawyer, & S. Ross (Eds.), Second Language Acquisition Research in Japan (pp. 73–100). Japan Association for Language Teaching.

- Takahashi, S. (2001b). The role of input enhancement in developing pragmatic competence. In K. R. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.), Pragmatics in Language Teaching (pp. 171–199). Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas, J. (2014). Meaning in Interaction: An introduction to pragmatics. Pearson Education.

- Trosborg, A. (2003). The teaching of business pragmatics. In A. Martinez-Flor, E. Uso, & A. Fernandez (Eds.), Pragmatic competence and foreign language teaching (pp. 247–281). Servei de Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I.

- Van Dijk, T. A. (1977). Context and cognition: Knowledge frames and speech act comprehension. Journal of Pragmatics, 1(3), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(77)90035-2

- Vásquez, C., & Sharpless, D. (2009). The role of pragmatics in the MA TESOL programs: Findings from a Nationwide Survey. TESOL Quarterly, 43(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2009.tb00225.x

- Wishnoff, R. J. (2000). Hedging your bets: L2 learners’ acquisition of pragmatic devices in academic writing and computer-mediated discourse. Second Language Studies, 19, 127–157. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228550729_Hedging_your_bets_L2_learners'_acquisition_of_pragmatic_devices_in_academic_writing_and_computer-mediated_discourse

- Yoshimi, D. R. (2001). Explicit instruction and JFL learners’ use of interactional discourse markers. In K. R. Rose & G. Kasper (Eds.), Pragmatics in language teaching (pp. 223–244). Cambridge University Press.

- Ziafar, M. (2018). The influence of explicit, implicit, and contrastive lexical approaches on pragmatic competence: The case of Iranian EFL learners. In IRAL - International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching (pp. 1–29). In Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2016-0018

Appendix A.

Each of the items below contains a conversational implicature. Please choose the correct answer by indicating what the assigned sentences mean.

1. Man: Congratulations! I understand you’ve got a job. When will you start to work?

Woman: You must be thinking of someone else. I’m still waiting to hear the good news.

Q: What does the woman mean?

(a) She does not need the job.

(b) She hasn’t got a job yet.

(c) She has got a job.

(d) She is going to start work soon.

2. Woman: Are you coming with me to the museum?

Man: I already have my hands full with this report.

Q: What does the man mean?

He must hand in a full report on the museum.

He is too busy to go along.

He has to put down the report.

He has already gone to the museum.

3. Woman: I think you’ve been working too hard. You should take a vacation. Man: Tell that to the pile of papers on my desk!

Q: What situation is the man in?

He has too much work to do.

He’ll take work with him on his vacation.

He’s already made his vacation plan.

It is hard for him to do his job on the vacation.

4. Woman: Mr. Jones, your student Bill shows great enthusiasm for musical instruments.

Man: I only wish he should have as much for his English lessons.

Q: What do we learn from the conversation about Bill?

He has made great progress in his English.

He is not very interested in English songs.

He is a student of the music department.

He is not very enthusiastic about his English lessons.

5. Woman: I’ve noticed that you get letters from Canada from time to time. Would you mind saving the stamps for me?

Man: My roommate already asked for them.

Q: What does the man imply?

a) He will save the stamps for the woman’s sister.

b) He will no longer get letters from Canada.

c) He cannot give the stamps to the woman’s sister

d) His roommate asked the man to give his letters to the woman’s sister.

6. Woman: Have you met Marge yet?

Man: We are from the same hometown.

Q: What does the man mean?

a) Marge has gone home.

b) Marge feels at home there.

c) He’s known Marge for a long time.

d) They have gone to the same town to meet each other.

7. Woman: Is Dave a friendly guy?

Man: He’s not unfriendly.

Q: Does the man think that Dave is friendly?

Yes, He is very friendly.

John does not know.

No, He is not friendly.

Yes, somehow.

8. Woman: Will Sally be at the meeting this afternoon?

Man: Her car broke down.

Q: Will Sally be at the meeting?

Yes, Certainly.

No, she can’t.

Yes, she comes with her car.

Yes, but she comes with a new car.

9. Woman: If you want that book, we’ll have to order it for you.

Man: Well, I’m leaving on Friday.

Q: What does John mean:

He will order the book.

He will get the book on Friday.

He will not order the book.

He is leaving to get the book on Friday.

10. Woman: Do you like linguistics?

Man: Oh! let’s say I don’t jump for joy before the class.

Q: What does the man mean?

He is uninterested about the linguistic class.

He is indifferent.

He is interested in linguistics.

He is always late for the linguistic class.

11. Woman: Do you like Monica?

Man: She is the cream in my coffee!

Q: Does the man like Monica?

Not at all.

Yes, more than the woman thinks.

No, they just meet for coffee

Yes, and they always meet in a coffee shop

12. Mary: What has happened to my bread?

John: Your cat seems to be happy!

Q: What does John mean?

John ate the bread.

John guess that the cat has eaten the bread.

John does not know.

The cat is waiting to have bread.

13. Woman: Do you want to go to the movies tonight?

Man: My little sister is coming for a visit.

Q: Will the man come to the movies tonight?

Yes, He will come with his sister. John guess that the cat has eaten the bread.

No, he won’t.

His sister is coming for the movies.

His sister is little, so the film is not good for her.

14. Woman: Your room is a mess. When is the last time you tidied your room?

Man: It was when Linda.

Q: What does the man mean?

He hasn’t cleaned his room since Linda visited him.

Linda is the only person who ever comes to see him.

He’s been too busy to clean his room.

Linda is the only person who makes a mess

15. Man: Do you want to turn on the air conditioner or open the window?

Woman: I love fresh air if you don’t mind.

Q: What can be inferred from the woman’s answer?

a) She’d like to have the windows open.

b) She likes to have the air conditioner on.

c) The air is heavily polluted.

d) She loves the fresh air of the room.

16. Woman: We’re informed that the 11:30 train is late again.

Man: Why did the railway company even bother to print a schedule?

Q: What do we learn from the conversation?

a) The train seldom arrives on time.

b) The schedule has been misprint.

c) The speakers arrived at the station late.

d) The time was not printed well on the tickets.

17. Man: Jimmy is going on a journey tomorrow. Shall we have a dinner tonight?

Woman: Do you think it’s necessary? You know he’ll be away just for a few days.

Q: What does the woman mean?

a) Jimmy is going to set out tonight.

b) Jimmy has not decided on his journey.

c) There is no need to have a dinner.

d) He is away and will not come for dinner.

18. Man: Did you like the movie last night?

Woman: I was glad when it was over.

Q: What did the woman think about the movie?

a) She taught the movie was good.

b) She did not enjoy the movie.

c) She liked the end of the movies.

d) She thinks the man should have watched the movie.

19. Man: How was the wedding? I bet it was exciting

Woman: Well …. The cake was OK.

Q: What does the woman think about the wedding?

a) She liked the wedding very much.

b) She did not enjoy the wedding so much.

c) Mary thought that the cake was not so good.

d) Mary does not remember the wedding.

20. Man: You sound busy! Do you like the job?

Woman: My mother wanted me to take it.

Q: Does Mary like the job?

a) Yes, and it was her mom’s suggestion.

b) Yes, she works with her mom.

c) No, she was forced by her mom.

d) No, she does the job instead of her mom.