Abstract

This paper presents a systematic review of 37 empirical studies that explored English teacher identity, and its formation through classroom practices from 1997 to 2020. After excluding 26 non-relevant studies from 63 articles, the remaining research has been analyzed through a systematic process to get salient themes that can be best cognized in terms of identity (re)construction issues among English language teachers, how they implement critical and post-method pedagogy, and reflect it in their classroom practices. More specifically, the following themes emerged: classroom practice as a reflection of teacher identity, native/non-native English speakers’ (NES/NNES) dichotomy, emotional tensions in identity formation, teachers’ knowledge of post-method pedagogy, and post-method barriers. This review also provided practical teaching tips for novice English teachers and teacher educators to better manage their identity tensions as teachers, improve their classroom practices and teacher education programs, and propose areas of investigation for future research. It calls for more in-depth qualitative and quantitative longitudinal studies that employ a positivist psychometric approach to measure and examine different facets of teacher identity development.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Teacher identity formation is ever-changing and a complex process. This review aimed to respond to the following research questions: 1. How do English teachers shape their professional identities when teaching English in different contexts? 2. How are their professional identities developed through critical pedagogy/post-method classroom practices? After selecting and analyzing 37 empirical studies, this review found the salient themes in identity formation and development including classroom practice as a reflection of teacher identity, discussion of existing native/non-native English speakers’ binary, identity-related emotional labors, teachers’ post-method pedagogy knowledge, and its constraints. This systematic review calls for more in-depth qualitative and quantitative longitudinal studies using multiple data collection tools and identity theories to explore English language teacher formation.

1. Introduction

The teacher identity formation is one of the most important issues in educational systems around the world due to its big impact on prospect and in-service teachers’ performance and quality of education in general; therefore, it has been the subject of a great number of research to investigate such construction (Fidler, Citation2002; Muñoz & Chang, Citation2007; Park & Lee, Citation2006; Rothstein, Citation2010; Stronge, Citation2018; Xiong & Xiong, Citation2017). There are many factors involved in (re)shaping teacher identity formation such as ethnographical (gender, age, ethnicity, and educational level); socio-cultural, political, economic, and institutional pressures (Barcelos, Citation2001; Caihong, Citation2011; Danielewicz, Citation2014; Duff & Uchida, Citation1997; Kocabaş-Gedik & Ortaçtepe Hart, Citation2020; Li, Citation2020; Olsen, Citation2008; Safari, Citation2020). Moreover, discriminatory treatment and the idea of who a native English speaker is initially legitimized certain English users while marginalizing the others.

Since English language teaching has been the center of focus for many researchers, it persistently has been questioned, investigated, and studied in terms of world Englishes and categorizing pertinent users (Burt, Citation2005; Crystal, Citation1997; Jenkins, Citation2006; Kachru, Citation1986; Mollin, Citation2006; Rajadurai, Citation2005). Giving a marginalized and inferior validity to different English language users other than English native speakers created a dichotomy between the two (Pennycook, Citation1989). It also caused much emotional and identity-related tensions for nonnative English language teachers (Kocabaş-Gedik & Ortaçtepe Hart, Citation2020). Therefore, numerous researches have been conducted to study the existing binary, its impacts; suggested implications, and even problematized NES/NNES dichotomy by proposing that linguistic identities are multi-faceted, dialogical, and dynamic (Faez, Citation2011; Peker et al., Citation2020).

To go beyond such a simplistic dichotomy, researchers tried to investigate the teachers’ identity through classroom practices; therefore, they questioned the method by making it abstract and labeled it as a concept rather than a concrete term. Finding a gap between methods prescribed by so-called experts and classroom realities in various context, Kumaravadivelu (Citation2003) suggested a post-method through which teachers could bridge between theory and practice by considering sociocultural, political, economic, and institutional realities in a particular context. Implementing such a teaching trend is aligned with critical pedagogy and its viability is sometimes constrained in a real context. Therefore, it calls for more investigation and inquiry. Critically reviewing the empirical articles on teacher identity formation and post-method pedagogy provides a solid grounding for English language teachers worldwide to effectively cope with their identity tensions and improve their classroom practices.

1.1. Scope of this review

Having an analytical view on English teacher educators’ works on teacher identity construction, a huge gap exists between NNES teachers’ attitude toward (none) native-speaking process and their classroom practices. In other words, the former researchers did not discuss and dig deeper into “othering” factors like regional and geographical linguistics, historical aspects, socio-psychological, socio-political, target and native cultural differences and embedded biases, and how teachers implement post-method pedagogy; its notions and limitations in the classroom. Further research and study on such topic considering the above factors can empower NNES teachers to (re)shape a progressive, positivist, and professional identity. Several methods have been used to choose studies to include in and achieve the aim of this study.

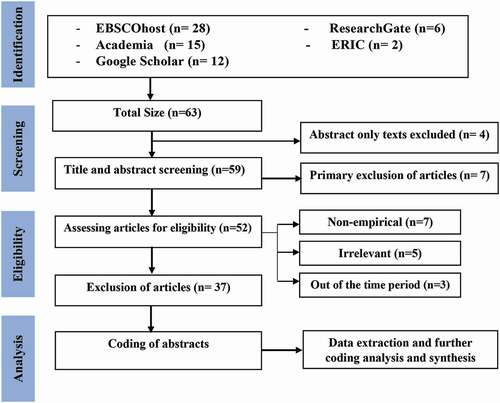

First, the empirical research has been selected by searching many databases (EBSCOhost, Academia, Research Gate, ERIC, and Google Scholar) during spring 2020. The author used a number of keywords to pinpoint the search in a precise horizon including post-method pedagogy, critical pedagogy, teacher identity formation, ESL/EFL, NES/NNES, and classroom practices. After locating the keywords in databases, the abstract of every article has been read. If it contained promising data about teacher identity development, it was searched then through online libraries to obtain full-text article. Alongside this library search for articles, reference sections of retrieved articles are also studied to gain more relevant research.

Second, the author primarily obtained 63 articles, but further excluded some articles after considering exclusion and inclusion criteria. The exclusion measures were such as, (1) being irrelevant to research questions, (2) non-empirical, (3) abstract only papers as a conference, as preceding papers, editorial, and author response theses and books, (4) unavailable full texts, and (5) out of the designated period. However, the inclusion measures comprised of (1) being related to research inquiry, (2) empirical, (3) full-text papers, and (4) within the selected time period. Therefore, this review included articles published from 1997 to 2020 and did not explore the other research outside of this time span; moreover, it only focuses on empirical studies for inclusion and excludes other non-empirical articles, such as Pennycook (Citation1989), Kumaravadivelu (Citation2003), etc. All researches that are found are bound to the author’s access to particular databases; therefore, there is a big room for researchers to study other related articles that they have availability and access in order to delve deeper into the subject and enlighten various aspect of it.

Finally, despite access limitation and based on prerequisite search conditions, this paper has selected 37 empirical researches that thoroughly depict teacher identity issues of English teachers and their classroom practices. First, the abstracts are coded for primary analysis and then the full-text articles are further read for in-depth data extraction, coding analysis, and synthesis. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart diagram is visually presented in detail ().

2. Focus question and themes

This study is going to explore the following questions:

How do English teachers shape their professional identities when teaching English in different contexts?

How are their professional identities developed through critical pedagogy/post-method classroom practices?

To achieve the aim of this review, the empirical studies have been divided into two categories: First 20 articles are solely based on teacher identity formation, the conflicts, backlashes, adaptation, and development (see ). These studies have been published from 1999 to 2020 and cover a wide range of different topics including NS/NNS discourses, imagined linguistic and professional membership and identities, the transformative potential of teacher identity, problematizing native/nonnative English speaker binary, student-teacher autonomy, and professional identity in mentorship, investigating identity formation through negotiation and positioning self, the discursive identity construction, and so forth.

Table 1. Studies that focus on teacher identity formation

Since teacher identity development cannot be studied in isolation without considering sociocultural, institutional, and pedagogical factors, the rest of the articles is grounded to illustrated teachers’ attitudes, knowledge, and classroom practices considering post-method pedagogy (see ). The following articles are written in the time period from 1997 to 2020. They cover a number of topics such as teacher identity formation through post-method classroom practices, identity formation through critical pedagogy practices (Bartolomé, Citation2004; Kubota, Citation2004; Menard-Warwick, Citation2008; Talmy, Citation2010; Zacharias, Citation2010), identity formation through post-method pedagogy practices, teachers’ knowledge of post-method pedagogy (Barnawi & Phan, Citation2015; Fat’hi et al., Citation2015; Motlhaka, Citation2015; Saengboon, Citation2013) and finally post-method pedagogy barriers (Ajayi, Citation2008; Chen, Citation2014; Duff & Uchida, Citation1997; Gu & Benson, Citation2015; Nishino, Citation2012; Rajabieslami, Citation2016).

Table 2. Studies that focus on teacher identity through post-method pedagogy

3. Results and discussion

This systematic review revealed that English teacher identity formation has been examined recurrently through a qualitative approach due to being a multi-faceted and complex phenomenon. It is also imbued with teachers’ teaching and learning experiences, biographies, values, believes, feelings, and emotional investment about continuous learning and professional development. However, a very few longitudinal studies exist which used multiple data collection tools to dissect this phenomenon and bring new insights into managing identity-related tensions from different perspectives. There is also a big room for conducting quantitative studies to examine teachers’ commitment, self-image, self-efficacy, task-perception, job-satisfaction, and motivation (Hanna et al., Citation2019) and explore identity connections and agentive behaviors with well-being and mental health of English language teachers using different quantitative psychometrical measures. More importantly, this systematic review found that the most salient themes of English language teacher identity and its development through post-method practice were not identified altogether with practical teaching tips.

After a study of 37 empirical research and writing a list of descriptive annotations, the salient themes have been emerged through applying the coding method. Generally, all themes fall into two main categories either teacher identity formation or teacher identity development through post-method pedagogy practices. Five main themes of English language teacher identity further became apparent in post-method era (see ).

4. Teacher identity formation

Encountering many conflicts and experience identity tensions during teacher education programs and after entering to workplaces, English language teachers have gone through processes that are synergic, dynamic, and complex to mold and shape their unique identities (Brutt-Griffler & Samimy, Citation1999). The conflicts might be related to teacher and linguistic identity formation through teaching practices, existing NES/NNES binary, emotional maladjustment, the discrepancy between prior and new experiences as both learner and teacher, racial hierarchy, and high level of expectations from mentors; etc. Each theme is followed by a teaching tip section that provides suggestions for English teachers to better manage identity development and related tensions.

4.1. Classroom practice as a reflection of teacher identity

Kanno and Stuart (Citation2011) found a reciprocal and interwoven affiliation between novice teachers’ identity development and their modifying classroom practice. In this case study, classroom practices caused the teachers to foster their identities, which mutually helped them form their teaching practices. Similarly, Kaya and Dikilitaş (Citation2019) explored the teacher identity formation through three phases: pre-existing, developing, and liberating identities that resonate with behaviorist, cognitivist, and socio-constructivist theories. They found that classroom practice play a pivotal role in identity development since the teacher participant developed his identity from behaviorist to socio-constructivist one in a supportive context where professional development was important in the language program. However, Golombek and Klager (Citation2015) investigated the role of imagination and play in teacher identity-in-activity. They found a paradox in teacher’s identity-in-activity, between students’ goals for understanding grammar and teacher candidates’ goals for teaching it. They claimed by creating an intermediary space, teachers could “play” with the images of their prior experiences and academic trainings on genre-oriented instruction; subsequently, they picture a different identity-in-activity to address students’ needs by self-regulating thoughts about teaching practices. As Morgan (Citation2004) claimed that teacher identity can be also a source for classroom practices. In his study, the issue of “image text” improved active and bilateral recognition and geared it toward pedagogical practices and teacher identity strategic performance, responding to fixed forms adapted by specific learners. Guihang and Miao (Citation2019) connected imagined positionalities to the context in which teachers are practicing their profession. The three identities are suggested for Business English teachers including teaching practitioners and researchers, learners, and businesspeople. Peker et al. (Citation2020) explored four foreign language teaching assistants’ lived experiences through the FLTA program in the USA. The study showed that assistant teachers experienced the following points which helped them shape their identities when practicing in the classrooms: pedagogical shift, cross-cultural awareness, challenges, and goals and expectations.

Having teacher identity as a resource and its close relationship with classroom practices and teaching context, some teachers even present their identities through job promotion examination as Werbińska (Citation2017) claimed. Using a general teacher identity framework (Affiliation, attachment and Autonomy), the study revealed five repertoires: exam-based, self-positioning, caring-for-other, shift, and making-a-difference. The examinees paid attention to modern and active teaching methods in the exam-based repertoire. In the self-positioning repertoire, they placed themselves either higher or lower than other teachers based on examination criteria. They showed that they take student’s needs into account in the caring-for-other repertoire. They also expressed a high degree of positive change after they started teaching and they unanimously wanted to impact on the learners and make a difference in the two last repertoires. Such repertoires can be interpreted as self-evaluation related to the capability to express their identity and see their roles as teachers.

Reviewing empirical articles on classroom practice as a reflection of teacher identity revealed that most research did not include specific teaching activities, the extend each influences teacher identity formation, and how teachers can reflectively cope with their identity tensions when employing particular practice.

4.1.1. Teaching tips 1

English language teachers could respond well if they consider the following points concerning identity formation through classroom practices:

The teachers could incorporate within themselves that identity is a dynamic, ever-changing, and malleable construct. It reiterates that teachers’ identity is not static and changes through personal and professional lives. Therefore, it could be highly effective if teachers look at the classroom practices as opportunities to shape a strong well-founded professional identity.

Self-evaluation and self-reflection play an important role in the identity development process. If teachers want to reflect upon their classroom practices, they could videotape how they teach identifying their strengths and weaknesses. This process cannot happen in isolation but involve other teachers and colleagues in discussion to better understand self, attach meaning to classroom practices, and explore what works and what does not (Kaya & Dikilitaş, Citation2019).

Teacher identity formation also varied from one teaching context to another. If teachers are willing to manage their identity tensions and gain professional development for their identity construction, universities and colleges can create a suitable environment for English teachers to fill existing gaps (Guihang & Miao, Citation2019).

4.2. Native/Non-native English Speakers’ (NES/NNES) dichotomy

The existing binary between NES/NNES has been the subject of numerous research like Brutt-Griffler and Samimy (Citation1999), Pavlenko (Citation2003), Park (Citation2012), Maduranga (Citation2013), Wolff and De Costa (Citation2017), and Lawrence (Citation2020). Most of these research articles aimed to explore discursive construction of identity formation regarding NES/NNES dichotomy, their relationship, and strategies to tackle relevant challenges and even problematize the existence of such a dichotomy.

Many English language teachers have trouble identifying their self-image as legitimate English language users, and some get caught in the trap of the NES/NNES dichotomy. Exploring imagined linguistic and professional membership and identities in pre and in-service ESL/EFL teachers in TESOL program, some English teachers positioned by the traditional discourse of linguistic competence falling into either NES or NNES communities (Pavlenko, Citation2003); however, they devoted persistent efforts to question such a binary and division; build a new relationship with various contexts and analyzed reasons of their powerlessness and create an agency as EL teachers (Brutt-Griffler & Samimy, Citation1999; Wolff & De Costa, Citation2017; Zacharias, Citation2010). Similarly, Lawrence (Citation2020) explored the existence of such a dualistic attributive mentality by comparing two English teachers’ identities: a non-native’ English speaker, and a “native” English speaker through a linguistic ethnographic framework. Interestingly, the teachers both positioned themselves at the institutional level where a clear distinction was made between native and non-native English speakers and also at the classroom level where they exerted agency to a significant extent which in turn, they used it as a coping strategy to show resilience toward identity-biased attributions.

The teachers have tried many ways to negate the existing binary and explored possible ways to shape their professional identities. For instance, foreign English teachers can also experience the same sort of unequal power dynamic and emotional challenges. Although have been privileged because of their ethnicity in the Korean context, they remained as others when learning Korean. These teachers also tried to find a satisfactory position by learning Korean and get into the state of being tolerant; therefore, it was important to extend the notion of self in an attempt to bridge cultural, ethnic, and community divisions and reach to a better mutual understanding in a new context (Gray, Citation2017). Some teachers created an imagined bilingual and multi-competent community membership to legitimize their language users’ status (Pavlenko, Citation2003). Remarkably, some non-native English teachers came up reflecting their identities through discursive, but effective use of writing rules (Supasiraprapa & Decosta, Citation2016). Legitimating multilingual teacher identities in the mainstream classrooms, Higgins and Ponte (Citation2017) claimed that teachers’ linguistic backgrounds deeply constructed their perspectives on multilingualism in their classrooms; nonetheless, it indicated that given an opportunity to examine and experience multilingual teachings created new room for teachers’ critical self-reflection on connections between different teachers’ professional identities, various languages and learning involvements for both teachers and multilingual students.

However, some researchers problematized native speakerism, a power-related and ideological notion and the dichotomy of NNS/NNES, a source of discrimination in the first place. Maduranga (Citation2013) problematized the validity of such a division. Using a qualitative approach including an interview and survey questionnaire, participants in the study were exposed to listen to six speeches of fluent English speakers (three American and three non-American living in the United States). Then the participants evaluated them based on accented-ness, fluency, competence, intelligibility, correctness, and pleasantness. The study revealed that particular patterns that illustrated inner native speaker division were much more extreme than NNS/NNES dichotomy. Investigating in a different lens, Kim (Citation2017) claimed that critical practices can demystify native speakerism within NNES teachers during their teacher education program. Therefore, such findings and mindset no longer give validity to the existing binary.

The articles related to Native/Non-native English speaker (NES/NNES) dichotomy themes are generally qualitative and did not include quantitative and a more positivist approach to examine the existence of such a binary among English language teachers through a psychological lens. The systematic review found very few studies that problematized this existing dualistic attributive mentality among English language teachers.

4.2.1. Teaching tips 2

The following points can respond effectively to the tensions that teachers encounter regarding NNS/NNES dichotomy.

Reexamining NNS teachers’ experiences and self-representation, adopting discursive practices that position NNS professionals at the center, studying ESL and EFL contexts and their participants’ diversity and finally posing implications for L2 teachers in various teaching contexts could assist the teachers to shape a well-rounded identity (Brutt-Griffler & Samimy, Citation1999).

If teachers of English want to manage the identity tensions effectively, they could first accept the fact that NNS and NNES teachers have distinct qualities; for instance, non-native English speakers are better at explaining the grammar and structure than native English counterparts. It will be useful to develop and maintain a positive and constructive mindset toward such a binary. This mentality helps the teachers cope with the related tensions.

Teacher educators and candidates could also explore the possible reasons that some students fell into the trap of false NEST/NNEST binary while some engage in process of imagining the multi-competent identity. In the light of this awareness, educators can question or validate the reasons for teachers’ emotional labors (Pavlenko, Citation2003).

Building and promoting criticality on NNS/NNES dichotomy through narrative writing and classroom discussion during teacher education programs could also assist English language teachers better respond to the tensions (Li, Citation2020; Wolff & De Costa, Citation2017);

Moreover, it will be helpful for English teachers to better shape their identities and tackle the emotional and academic challenges better, if institutions facilitate the process of building relationships outside of the organization’s confines and avoid NES/NNES labeling to prevent discriminatory behaviors (Lawrence, Citation2020).

4.3. Emotional tensions in identity formation

Emotional tensions within NNESTs are depicted in the study of Wolff and De Costa (Citation2017). Studying the effects of emotions on participant’s teacher identity construction and investigating how it developed and became manifest in implementing teaching strategies. Through a narrative approach, the study pondered over reflective relations between participants’ feelings and identity formation. The results revealed that emotional conflicts were constituents of teacher identity construction and they were more common for non-native English speakers. The participant highly and effectively resolved tensions accepting a new teacher status, designing locally situated strategies like democratic and learner-centered and moving beyond her teacher identity. The researcher suggested that teacher educators can assist NNESTs address the sense of insecurity by engaging them in professional reflexivity “to develop a sense of agency; however, despite struggling with emotional conflicts according to Jones (Citation2016), some teachers showed little emotional values toward children in their teaching collective beliefs in the same regional context. Therefore, the author called for achieving an effective metalanguage by which such values will be better clarified during discussion and reflection. Warner (Citation2016) in his study claimed that striving to keep up with excellent qualities enforced by teacher educators and teacher candidates” colleagues led to some emotional tensions; however, they started forming their identities as compared to excellent teacher prototypes.

In a similar vein, Li (Citation2020) explored the teacher identity formations of two Chinese English teachers through a narrative inquiry. The study examined the dynamic interplay among three constructs of emotions, belief, and identity. One of the teacher’s identities was constructed by the emotions of being inferior and her beliefs in correct speaking and authentic use of English compared to native English speakers. Such unequal power-relations caused her some emotional challenges while struggling to create a sense of rightfulness in his profession, which influenced her well-being negatively. The other teacher’s identity has been gone through various emotional labors due to work pressure caused by a competitive customer-oriented market. He experienced mixed emotions of frustration and usefulness when teaching his students. The reasons that encouraged him to be a teacher were lack of power in the community and feeling of invisibility. The teacher identity development of both English teachers was formed by a set of feelings and beliefs that they experienced through their personal and professional experiences; therefore, the study showed that a dynamic, ever-changing, and complex relationship exists among teachers’ beliefs and emotions and identities.

Reviewing these empirical articles revealed that most authors have adopted a narrative approach to examine related identity tensions among English language teachers. However, almost no study investigated emotional labors using psychological measures and lenses, for example, neuropsychology, psychoanalysis, and social-cognitive model.

4.3.1. Teaching tips 3

Positioning the relationship of teacher identity development and emotions as focal points of other future studies could help novice teachers or teacher candidates to embrace their teacher identities, feelings, and adapt related and effective strategies (Jones, Citation2016).

Thinking about idealistic expectations of a perfect teacher and experiencing related emotional discharges hinder teacher candidates from taking full advantage of their practicum. Sometimes, it could end up to their refusal. It will be effective if the teacher candidates become familiar with English classrooms’ realities and acquire practical experiences instead (Delgado, Citation2016).

If teacher educators modify TESOL programs as more emotionally responsive, culturally suited, context-specific, and encourage criticality, integrate field experiences during teacher education program and promote post-method pedagogy, it could help English teacher candidates better shape their identities and manage the identity tensions (Park, Citation2012).

5. Teacher identity development through critical pedagogy/post-method classroom practices

The teacher identity plays a pivotal role in preparing teachers to teach for addressing social justice, and educators can explore and reimagine possible ways that the content and course projects help them shape the related ideologies (Quan et al., Citation2019). Critical pedagogy questions power relations in every aspect of education either teacher and students in particular or schools, curriculum, and policy makers in general to provide equity and social justice. It transforms both teachers and students to change agents; however, in particular, post-method pedagogy calls for reviewing teachers’ perspectives toward the concept of method, the content, learners, and the context. Since teaching context and learners are socio-culturally different and theories are not closely connected to realities of practice sites, prescribed methods by so-called experts do not work well. Therefore, teachers should be in search of an alternate for method and theorize what they practice and practice what they theorize. Kumaravadivelu (Citation2005) also addresses some problems and implements post-method condition such as pedagogical hinders, which refers deeply rooted beliefs of teacher educator role models to future teacher and ideological barriers that denote teachers’ mindset on what is ideal and valid as knowledge. Despite illustrating guidelines, identifying barriers, and associated problems for such pedagogy, it cannot effectively fill the gap between theory and actual practice. Here are some empirical studies that discuss critical and post-method pedagogies’ actual classroom practices, barriers, concerns, and implications.

Critical pedagogy has been discussed in a number of empirical articles to address identity formation, social inequity, power relations, and cultural issues. Remaining linguistic identity as salient, teacher identity can be transformed through the negotiation of critical pedagogy in teacher education programs; therefore, teacher educators should design TESOL programs to address language aspects and incorporate critical pedagogy to shape teacher identities (Zacharias, Citation2010).

Talmy (Citation2010) claimed that there is a hegemonic ESL hierarchy that planned racial identifications based on racial hierarchy not only in high schools but also in larger context Hawaii; therefore, racism has been as a resource in Hawaii public high schools by old-timer ESL students and even teachers sometime treated such behaviors indifferently. Bartolomé (Citation2004), however, emphasized on political and ideological clarities of teachers about students of the minority. In his study, teachers had a quite acceptable level of awareness about asymmetrical power relations. They created a sustainable even-handed and supportive “learning playground” for all students regardless of their gender, race, social class, and economy. They also problematized the dominant ideologies such as white supremacy or meritocratic descriptions of social hierarchy and turned down the insufficiency and incapability of their students’ perceptions.

Cultural variety in the classroom is also a pivotal reality in critical pedagogy. Teachers are responsible for addressing such realities with respect and tolerance and delving into deeper cultural stratus by questioning power relations rather than looking at the culture on the surface (Kubota, Citation2004). Exploring to understand transnational teachers’ overlapping relationships between their life experiences and their intercultural competence, Menard-Warwick (Citation2008) studied their intercultural identity and ways they address cultural issues in the classroom. Both subject participants defined themselves as being bicultural, but used two distinct approaches to address cultural topics like subjective comparison and students’ cultural changes through globalization. Teachers need to consider pedagogical resources that intercultural teachers use to teach English in their classrooms and transform the learners into change agents.

A number of future implications have been proposed to address critical pedagogy in teacher education programs and actual classroom practices. Transforming teacher identity, teacher education programs, and practicum by implementing and teaching important critical pedagogy practices (Bartolomé, Citation2004; Zacharias, Citation2010). Therefore, the TESOL program should not be color-blind. It would be helpful if both teacher educators and ESL teacher address and incorporate race and racism issues into classroom practices to help students get rid of the existing hierarchy and shape identities free of racialization (Talmy, Citation2010). Moreover, teachers candidates could get intercultural knowledge in the TESOL program by sharing intercultural autobiographies and personal statements; working on memoirs and films depicting lived experiences in their classrooms (Menard-Warwick, Citation2008) and encouraging them to teach in a different dominant culture (Gu & Benson, Citation2015; Menard-Warwick, Citation2008).

5.1. Teachers’ knowledge of post method pedagogy

Saengboon (Citation2013) studied the understanding of the post-method pedagogy of Thai EFL university lecturers and explored to what extent such understanding reflects their teaching practices. The study showed the lecturers had a satisfactory understanding level of post-method pedagogy and they mostly emphasized the significance of teaching the English language with passion and a sense of caring. He called for studying Tai EFL students’ interest in learning English and their teachers’ understanding of existing methods is a good preliminary stage to explore and implement post-methods pedagogy. Fat’hi et al. (Citation2015) also claimed that teachers showed a high level of willingness toward post-method pedagogy and the study revealed a meaningful constructive correlation between EL teachers’ post-pedagogical insights and their reflection in teaching.

Motlhaka (Citation2015) studied post-method pedagogy for the professional development of ESL university lecturers to improve their learners’ English language proficiency level. The study showed that it was necessary to include both learners in post-method pedagogy and empower students in this regard. In a related vein, Barnawi and Phan (Citation2015) found the two target teachers used different approaches to teach English despite their Western TESOL training. They were aware of post-method pedagogy and used context-sensitive approaches based on the learners’ needs and potentials. Barnawi and Phan (Citation2015) also questioned the enlightening and educational role of such TESOL programs while emphasizing participants’ and teacher educators’ ongoing engagement, meaningful interactions, and reflections over pedagogies during their training and classroom practices.

Connecting theory to practice is one of the pivotal issues in post-method pedagogy. Some teachers can make such connections, while some fail to practice what they theorize. Jones (Citation2016) investigates whether teachers can connect theory to practice and how they improve teaching values. The study showed that teacher candidates connected the two effectively by the intervention of method-cases. Personalized learning and professional value development were also emerged as a result of teachers’ practices. The study emphasized that case-method pedagogy led to teacher preparation and enabled them to connect theories to practice in particular contexts and classrooms.

After critically reviewing the studies about teachers’ knowledge of post-method pedagogy, most articles did not measure English language teachers’ understanding of the parameters of particularity, practicality, and possibility and their levels in depth. They also did not explore the relationship between such knowledge with teachers’ actual critical pedagogy practice in a quantitative manner. The current studies heavily relied on teachers’ narrative reports.

5.1.1. Teaching tips 4

Introducing alternative teacher identity choices, activism, and critical pedagogies into teacher education programs can develop candidates’ positionalities towards their classroom practices due to incorporating both their own and their students’ identities;

Case-method pedagogy helps teacher candidates improve emotional values toward children in their teacher identities (Jones, Citation2016);

It is promising in terms of effectively implementing critical pedagogy if the teachers continuously take into account students’ choices and essential factors such as the role of teachers as transformative intellectuals, and contextualize the content and activities, improve learner autonomy, increase linguistic input and learning opportunity, appreciate adventure learning, and finally, recognize students’ cultures (Motlhaka, Citation2015);

Reflecting upon their classroom practices and disseminating their successes and pitfalls through forums and journals help teachers avoid replicating the prescribed concept of the method (Fat’hi et al., Citation2015).

5.2. Post-method barriers

Rajabieslami (Citation2016) studied teachers’ perception of the post-method feasibility. The study revealed that there was a discrepancy between teachers’ expectations of post-method pedagogy and classroom realities. The study also described post-method pedagogy restrictions such as: tests, materials, and mainstream teacher education. In other words, assessment, and textbooks did not encourage post-method pedagogy; therefore, they needed to be revised to better fit into post-method pedagogy as well as teacher education programs were required to be redesigned and they should have raised awareness about the restrictions and ways to tackle them most effectively by the medium of practicum. In a related vein, Chen (Citation2014) revealed that although teachers expressed their agreement with post-method micro-strategies, their classroom practices were more teacher-centered rather than student-centered as opposed to post-method pedagogy disciplines. Their students also generally claimed that their teachers did not appropriately implement the micro-strategies.

Nonetheless, EL teachers tried different strategies in their classroom because of their autonomy and decision-making. The author recommended that well-experienced teachers share their practical knowledge with novice teachers to increase post-method teaching efficacy. The researcher concluded that this study could be conducted by middle school teachers to discuss and examine more post-method strategies. Nishino (Citation2012) noted that teachers’ beliefs were sometimes inconsistent with practices in teaching context and cannot connect theory to practice effectively. The author studied Japanese high school teachers’ perceptions and classroom practices were related to communicative language teaching (CLT) and its socio-cultural issues. The study revealed that the teachers’ schooling, learning experiences, professional coursework, and contextual factors such as entrance exam impacted their beliefs and classroom practices regarding CLT.

Social-cultural factors also influence the way teachers implement teaching practices and post-method pedagogy in general. Ajayi (Citation2008) claimed despite teachers in his study were sensitive to the significance of their learner’s socio-cultural-lived experiences, but the integration of social-cultural perspectives into classroom practices was constrained by inappropriate teachers’ autonomy, insufficient ESL teachers, inadequate methods of assigning students in ESL class despite different language proficiency, the pressure of covering the curriculum, limitations of curriculum and textbook, restricted access to technology, the unfamiliarity of language instructions to students, and finally the adverse effect of assimilation to the English language as alienation to students’ own community. Gu and Benson (Citation2015), also stated that identity construction was influenced by socio-cultural factors and formed by social discourses about teachers and their profession; however, they found differences between two focus groups’ identity formations and their teaching beliefs in case of their engagement in learning to teach, their alignment with social discourses and envisioning alternatives for methods.

Duff and Uchida (Citation1997) also studied the intricate correlations between teachers’ sociocultural identities and their classroom practices and related cultural transitions to the classrooms. The study revealed that there were intricacy and inconsistency related to EFL teachers’ sociocultural identities and their representation in classroom practices, their attempt to make a socio-cultural connection to target culture; their enthusiasm for having personal and educational authority to tackle cultural practices, and finally, between teachers’ cultural knowledge and classroom practices.

5.2.1. Teaching Tips 5

Providing demo lessons to learn the practical use of new teaching approach and giving freedom to form a criticality toward traditional methodologies in their context during in-service training could help teachers promote post-method pedagogy (Nishino, Citation2012);

It will be very helpful if a teacher is assigned to explore possible reasons behind particular learning activities to meet students’ learning styles, expectations and also choose effective teaching techniques accordingly (Nishino, Citation2012);

The administrators could reduce teacher workload to open space for their professional development. Successful reform in English education requires understanding teachers’ complex perceptions, specific context, and rethinking of the entrance exam (Nishino, Citation2012);

It teacher educators want to provide critical perspectives to negotiate both curriculum and teachers’ sociocultural identities, they can examine cultural foundations of EFL curriculum and the related discourses and practices (Duff & Uchida, Citation1997);

Adopting educational policies to students’ sociocultural realities, recruiting qualified teachers, wisely choosing textbooks reflecting multi-socio-cultural contexts, providing technological tools to encourage meaning-making negotiation, and increasing emotional investment can positively influence enacted pedagogy (Ajayi, Citation2008);

Suppose teachers want to achieve and implement critical pedagogy. In that case, they could critique power interplays, question school practices and social discourses that marginalized their competency, recognize the potential benefits of being non-native English teachers, have exchange programs in multicultural contexts for teacher candidates, take the benefits of socio-historical background, and finally empower their students to shape their bilingual identities (Gu & Benson, Citation2015).

6. Conclusion

A review of literature has shown that teacher identity formation is a fluid, , and multi-faceted process and is persistently shaped by discursive negotiations, classroom practices, and socio-cultural factors. English language teachers persistently try to develop their professional identity to not fall into the trap of a false NES/NNE dichotomy. Therefore, many researchers sought to legitimize nonnative English speakers as multi-competent users and some tried to problematize the existence of such dichotomy. Besides, English language teachers

Post-method and critical pedagogy have also been two sites of struggle for English language teachers to form their identities and reflect them through such pedagogical practices. Furthermore, there have been some barriers to implement related pedagogical practices; therefore, English teachers sometimes fail. The challenges include the inconsistency of curriculum and textbooks with post-method and critical pedagogy, fixed and predetermined assessment, administrative rules, and extreme hegemony of power.

This review has some limitations. First, access to recent studies was limited due to library restrictions. Second, most articles were not empirical and relevant to this study’s scope, topic, and aim. Finally, there were a few researches on teacher identity development through the lens of critical pedagogy.

This study came up with some future implications and called for further in-depth quantitative and qualitative longitudinal studies using multiple theories and research instruments to delve deeper into English teacher identity formation, reflection through classroom practices, and post-method and critical pedagogy. Most existing studies did not examine English language teacher identities using a robust and comprehensive psychoanalytic approach to examine identity formation and related post-method practices. English language teachers experience unique journeys to develop their professional identities. Therefore, their narratives will help many teachers around the world manage the tensions and emotional labors they experience when teaching the English language. The more teachers are engaged in the dialogue about the identity development, related emotional labors, and tensions, the better they would dismantle false ideology around NES/NNES dichotomy, change the discriminatory behaviors, demystify the nuances of their unique professional identity, and promote their agentive behavior to bring about institutional and social change.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jawad Golzar

Jawad Golzar is a faculty member at the English Department, Herat University, Afghanistan. He holds a master’s degree in TESOL, and he has obtained it through Fulbright Scholarship from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA. He has participated in numerous academic, personal and professional development programs within the past few years. His research interests include teacher identity, educational technology, writing self-efficacy, and issues related to giving voices to others.

References

- Ajayi, L. (2008). ESL theory-practice dynamics: The difficulty of integrating sociocultural perspectives into pedagogical practices. Foreign Language Annals, 41(4), 639–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2008.tb03322.x

- Barcelos, A. F. (2001). The interaction between students’ beliefs and teacher’s beliefs and dilemmas. In B. Johnston & S. Irujo (Eds.), Research and practice in language teacher education: Voices from the field (pp. 69–86). University of Minnesota, Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition.

- Barnawi, O. Z., & Le Ha, P.(2015). From western TESOL classrooms to home practice: A case study with two ‘privileged’ Saudi teachers. Critical Studies in Education, 6 6 56(2), 259–276.https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2014

- Bartolomé, L. I. (2004). Critical pedagogy and teacher education: Radicalizing prospective teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 31(1), 97–122. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ795237

- Brutt-Griffler, J., & Samimy, K. (1999). Revisiting the colonial in the postcolonial: Critical praxis for nonnative-English-speaking teachers in a TESOL program. TESOL Quarterly, 33(3), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587672

- Burt, C. (2005). What is international English? TESOL & Applied Linguistics, 5(1), 1–20. https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/SALT/article/view/1582

- Caihong, H. (2011). Changes and characteristics of EFL teachers’ professional Identity: The cases of nine university teachers. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 34(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal.2011.001

- Chen, M. (2014). Postmethod pedagogy and its influence on EFL teaching strategies. English Language Teaching, 7(5), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v7n5p17

- Crystal, D. (1997). English as a global language. Cambridge University Press.

- Danielewicz, J. (2014). Teaching selves: Identity, pedagogy, and teacher education. SUNY Press.

- Delgado, L. D. F. (2016). Exploration of learner teacher autonomy and professional identity through mentoring: Expectations and perceptions of ESOL learner teachers. The Global Journal of English Studies, 2, (2). https://www.academia.edu/32373098/Exploration_of_Learner_Teacher_Autonomy_and_Professional_identity_through_Mentoring_Expectations_and_Perceptions_of_ESOL_Learner_Teachers

- Duff, P. A., & Uchida, Y. (1997). The negotiation of teachers’ sociocultural identities and practices in postsecondary EFL classrooms. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 451–486. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587834

- Faez, F. (2011). Are you a native speaker of English? Moving beyond a simplistic dichotomy. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 8(4), 378–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2011.615708

- Fat’hi, J., Ghaslani, R., & Parsa, K. (2015). The Relationship between post-method pedagogy and teacher reflection: A case of Iranian EFL teachers. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 2(4), 305–321. http://jallr.com/~jallrir/index.php/JALLR/article/view/82

- Fidler, P. (2002). The relationship between teacher instructional techniques and characteristics and student achievement in reduced size classes. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED473460

- Golombek, P., & Klager, P. (2015). Play and imagination in developing language teacher identity-in-activity. Ilha Do Desterro A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, 68(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2015v68n1p17

- Gray, S. (2017). Always the other: Foreign teachers of English in Korea, and their experiences as speakers of KSL. The Asian EFL Journal Quarterly, 19(3), 1–30. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/main-editions-new/volume-19-issue-3-september-2017-quarterly-journal/

- Gu, M., & Benson, P. (2015). The formation of English teacher identities: A cross-cultural investigation. Language Teaching Research, 19(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168814541725

- Guihang, G., & Miao, Z. (2019). Identity construction of Chinese business English teachers from the perspective of ESP theory. International Education Studies, 12(7), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v12n7p20

- Hanna, F., Oostdam, R., Severiens, S. E., & Zijlstra, B. J. (2019). Domains of teacher identity: A review of quantitative measurement instruments. Educational Research Review, 27(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.01.003

- Higgins, C., & Ponte, E. (2017). Legitimating multilingual teacher identities in the mainstream classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 101(S1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12372

- Jenkins, J. (2006). Current perspectives on teaching world Englishes and English as a lingua franca. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 157–181. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264515

- Jones, S. A. (2016). Pedagogy for teacher education: Making theory, practice and context connections for English language teaching. AsTEN Journal of Teacher Education, 1(2), 72–89. http://po.pnuresearchportal.org/ejournal/index.php/asten/article/view/295

- Kachru, B. B. (1986). The alchemy of English: The spread, functions, and models of non-native Englishes. Pergamon.

- Kanno, Y., & Stuart, C. (2011). Learning to become a second language teacher: Identities-in-practice. The Modern Language Journal, 95(2), 236–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01178.x

- Kaya, M. H., & Dikilitaş, K. (2019). Constructing, reconstructing and developing teacher identity in supportive contexts. The Asian EFL Journal January, 1(21), 58–83. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/main-editions-new/2019-main-journal/volume-21-issue-1-2019/

- Kim, H. K. (2017). Demystifying native speaker ideology: The critical role of critical practice in language teacher education. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 14(1), 81–97. http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2017.14.1.6.81

- Kocabaş-Gedik, P., & Ortaçtepe Hart, D. (2020). “It’s Not Like That at All”: A poststructuralist case study on language teacher identity and emotional labor. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2020.1726756

- Kubota, R. (2004). Critical multiculturalism and second language education. In B. Norton & K. Toohey (Eds.), Critical pedagogies and language learning (pp. 30–52). Cambridge University Press.

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Forum: Critical language pedagogy: A postmethod perspective on English language teaching. World Englishes, 22(4), 539–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2003.00317.x

- Kumaravadivelu, B. (2005). In defense of postmethod. ILI Language Teaching Journal, 1(1), 15–19.

- Lawrence, L. (2020). The discursive construction of “native” and “non-native” speaker English teacher identities in Japan: A linguistic ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 8(1), 111–125. http://www.ijscl.net/article_38734.html

- Li, W. (2020). Unpacking the complexities of teacher identity: Narratives of two Chinese teachers of English in China. Language Teaching Research, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820910955

- Maduranga, N. K. (2013). Rethinking the ‘native speaker’/’nonnative speaker’ dichotomy. Sri Lanka Journal of the Humanities, 39(1–2), 37–50. http://dlib.pdn.ac.lk/handle/1/4534

- Menard-Warwick, J. (2008). The cultural and intercultural identities of transnational English teachers: Two case studies from the Americas. TESOL Quarterly, 42(4), 617–640. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1545-7249.2008.tb00151.x

- Mollin, S. (2006). English as a lingua franca: A new variety in the new expanding circle. Nordic Journal of English Studies, 5(2), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.35360/njes.11

- Morgan, B. (2004). Teacher identity as pedagogy: Towards a field-internal conceptualization in bilingual and second language education. Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7(2–3), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050408667807

- Motlhaka, H. A. (2015). Exploring postmethod pedagogy in teaching English as second language in south African higher education. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), 517-524. Doi:10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n1p51

- Muñoz, M. A., & Chang, F. C. (2007). The Elusive relationship between teacher characteristics and student academic growth: A longitudinal multilevel model for change. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 20(3–4), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9054-y

- Nagatomo, D. (2011). Japanese teacher of English in Japanese higher education. The Language Teacher, 35(6), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.37546/JALTTLT35.6-5

- Nishino, T. (2012). Modeling teacher beliefs and practices in context: A multimethods approach. The Modern Language Journal, 96(3), 380–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2012.01364.x

- Olsen, B. (2008). Teaching what they learn, learning what they live. Paradigm Publishers.

- Park, G. (2012). “I am never afraid of being recognized as an NNES”: One teacher’s journey in claiming and embracing her nonnative-speaker identity. TESOL Quarterly, 46(1), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.4

- Park, G. P., & Lee, H. W. (2006). The characteristics of effective English teachers as perceived by high school teachers and students in Korea. Asia Pacific Education Review, 7(2), 236–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03031547

- Pavlenko, A. (2003). “I never knew I was bilingual”: Reimagining teacher identities in TESOL. Journal of Language Identity & Education, 2(4), 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0204_2

- Peker, H., Torlak, M., Toprak-Çelen, E., Eren, G., & Günsan, M. (2020). Language teacher identity construction of foreign language teaching assistants. International Online Journal of Education and Teaching (IOJET), 7(1), 229–246. https://iojet.org/index.php/IOJET/article/view/733

- Pennycook, A. (1989). The concept of method, interested knowledge, and the politics of language teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 23(4), 589–618. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587534

- Quan, T., Bracho, C. A., Wilkerson, M., & Clark, M. (2019). Empowerment and transformation: Integrating teacher identity, activism, and criticality across three teacher education programs. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 41(4–5), 218–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2019.1684162

- Rajabieslami, N. (2016). Teachers’ perceptions of the post-method feasibility. Arab World English Journal, 7(3), 238–250. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol7no3.17

- Rajadurai, J. (2005). Revisiting the concentric circles: Conceptual and sociolinguistic considerations. The Asian EFL Journal Quarterly, 7(4), 111–130. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/main-editions-new/revisiting-the-concentric-circles-conceptual-and-sociolinguistic-considerations/

- Rothstein, J. (2010). Teacher quality in educational production: Tracking, decay, and student achievement. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(1), 175–214. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2010.125.1.175

- Saengboon, S. (2013). Thai English teachers’ understanding of “postmethod pedagogy”: Case studies of university lecturers. English Language Teaching, 6(12), 238–250. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v6n12p156

- Safari, P. (2020). Iranian ELT student teachers’ portrayal of their identities as an English language teacher: Drawings speak louder than words. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 19(2), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2019.1650279

- Stronge, J. H. (2018). Qualities of effective teachers (2nd ed.). Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Supasiraprapa, S., & Decosta, P. I. (2016). Metadiscourse and identity construction in teaching philosophy statements: A critical case study of two MATESOL students. TESOL Quarterly, 51(4), 868–896. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.360.

- Talmy, S. (2010). Becoming “local” in ESL: Racism as resource in a Hawaii public high school. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 9(1), 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348450903476840

- Warner, C. K. (2016). Constructions of excellent teaching: Identity tensions in preservice English teachers. National Teacher Education Journal, 9(1), 5–15. https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/003a8836-40db-4b0c-b44f-4211ffada1e1/downloads/1ckfvh3q9_717333.pdf

- Werbińska, D. (2017). A teacher-in-context: Negotiating professional identity in a job promotion examination. Journal of Applied Language Studies, 11(2), 103–123. https://doi.org/10.17011/apples/urn.201708233541

- Wolff, D., & De Costa, P. I. (2017). Expanding the language teacher identity landscape: An investigation of the emotions and strategies of a NNEST. The Modern Language Journal, 101(S1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12370

- Xiong, T., & Xiong, X. (2017). Teachers’ perceptions of teacher identity: A survey of Zhuangang and non-Zhuangang primary school teachers in China. English Language Teaching, 10(4), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n4p100

- Zacharias, N. T. (2010). The teacher identity construction of 12 Asian ES teachers in TESOL graduate programs. The Journal of Asia EFL, 7(2), 177–197