Abstract

Electronic portfolios, as digitalized collections of artifacts including resources, demonstrations, and accomplishments that represent an individual, group, or institution activity, can be used to formatively measure learners’ progress and learning with regard to their own production and documentation of educational content. E-portfolios are believed to have considerable potential to provide feedback about learners’ performance throughout the course and also to measure their mastery of the content materials with the help of their active participation in the assessment process. This study intended to gauge the feasibility of EFL learners’ using of e-portfolios in the traditionally exam-oriented context of Iran and also to investigate the potential advantages and challenges of introducing a learning-focused assessment tool to EFL classes. Using mixed methods—questionnaires, semi-structured individual interviews, and focus groups, the current study investigated the learners’ attitudes towards the integration of e-portfolios into their English classes. To that end, the researcher conducted a longitudinal survey by collecting the data from students who attended the Iran language institute (ILI) from 2013 to 2017. To collect the data, 90 EFL learners were given questionnaires seeking their attitudes and experience of using e-portfolios in their English classes, with 50 students participating in the follow-up interviews and 12 students took part in focus groups. The results revealed that e-portfolios were used for documenting many educational activities as diverse as a travel log, storytelling, written compositions, movie reviews, and diaries. Most learners liked e-portfolios as it provided a portrait of the breadth and depth of their learning progress in a more flexible environment in which they could easily reflect on their personal progress by exchanging ideas and feedback. The results of this study can contribute vastly to Iranian syllabus designers to supplement the traditional assessment with a technology-based approach to learning and assessment.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Technology has been used to both help and improve language learning. Technology enables teachers to adapt classroom activities, thus enhancing the language learning process. Technology continues to grow in importance as a tool to help teachers facilitate language learning for their learners. Following the significant importance of technology in language learning, this study aimed to check the impact of using E-portfolios in the traditionally exam-oriented context of Iran and also to investigate the potential advantages and challenges of introducing a learning-focused assessment tool to EFL classes. After analyzing the data, it was revealed that E-portfolios are totally beneficial as they provided a portrait of the breadth and depth of learners’ learning progress in a more flexible environment.

1. Introduction

Electronic portfolios have gained major attention in EFL contexts and are increasingly being utilized to support and promote learning and teaching processes (Hinojosa-Pareja et al., Citation2020; Oh et al., Citation2020). As the flag-carriers of formative assessment, they offer multiple benefits in both formal and non-formal learning syllabuses (Luchoomun et al., Citation2010). Moreover, e-Portfolios in the Iranian educational system have become an essential facet of e-learning systems because they can trigger more student-centered learning, reflective activities, and personalized types of learning among learners with diverse knowledge backgrounds (Stefani et al., Citation2007; Yang et al., Citation2016a). Consequently, the Iranian EFL context has witnessed a long period of practice using the traditional language system which is mainly based on the concept of summative assessment (Firoozi et al., Citation2019; Namaziandost, Rezvani et al., Citation2020). The fast-growing desire of Iranian EFL context towards new teaching-learning-assessment methods requires a significant shift from a traditional testing system to digital learner portfolios as they can promote students’ autonomy by enabling them to be the managers of their virtual learning environment (Namaziandost & Çakmak, Citation2020; Torabi & Safdari, Citation2020; Yang et al., Citation2016b).

In reviewing the definitions regarding e-portfolio, the researchers found out that most of them covered features like students’ digital artifacts (Brown et al., Citation2007), digitalized collections, and a purposeful aggregation of digital items (Gray, Citation2008). Perhaps the best definition of e-portfolio was provided by Lorenzo and Ittelson (Citation2005), as they defined e-portfolio as “a digitized collection of artifacts including demonstrations, resources, and accomplishments that represent an individual, group, or institution” (p. 2). They also add that e-portfolios are “personalized, Web-based collections of work, responses to work, and reflections that are used to demonstrate key skills and accomplishment for a variety of contexts and time periods” (p. 2). The literature seems to reveal a general consensus of three major types of e-Portfolio. In the same vein, Maher and Gerbic (Citation2009) concluded that there are three different types of portfolios: a learning portfolio, a showcase portfolio, and an assessment portfolio. The current study, however, regarded the portfolio as an assessment tool to be used for gauging students’ learning development over the English learning semester.

More importantly, English teachers too use different materials and methods in different situations because of pressures from principals, other school administrators, colleagues, parents, the community, and the media. Herman and Golan (Citation1993), in their comparative study of teachers’ perceptions of the effects of standardized testing, report that teachers in schools which put a high premium on test scores usually receive a lot of pressure to improve their students’ scores from external sources more than teachers in schools with less interest in quantitative student performance. In other words, the teachers believe that testing has affected instructional planning and delivery because of these external pressures. It is for this reason that Hamp-Lyons (Citation1997) suggests that broad forces in education and society be taken into consideration while studying the politics of washback in teaching.

In Iran, expectations of parents and school principals merely revolve around the students’ performance in exams which, as earlier noted, is not grounded incommunicative principles in language teaching. Such demands in turn affect the teachers’ perspective on what good teaching is all about, including what materials and exercises are deemed appropriate and necessary for the students. According to Jahangard (Citation2007), students’ aural and oral skills are not emphasized in Iranian prescribed EFL textbooks. They are not tested in the university entrance examination, as well as in the final exams during the 3 years of senior high school and 1 year of pre-university education. Teachers put much less emphasis, if any, on oral drills, pronunciation, listening, and speaking abilities than on reading, writing, grammar, and vocabulary. The main focus is to make students pass tests and exams, and because productive abilities of students are not tested, most teachers then skip the oral drills in the prescribed books.

Moreover, school authorities and parents in Iran believe that good schools are schools that generate high grades on standardized tests. Since teachers are aware that their students’ outcome is an indicator of the quality of their work, accountability purposes of assessment might dominate teachers’ assessment beliefs. Although teachers are encouraged to use formative assessment during the school year, they seldom utilize this assessment type. Also, no documented research has been conducted on the psychometric properties of standardized tests administered (Farhady & Hedayati, Citation2009 as cited in Saad et al., Citation2013). Even though because of the popularity of discrete point tests and summative testing of students’ learning, teachers still focus on summative assessment and do not have enough knowledge and skill to implement the new assessment system. That is to say, the focus is still on students’ performance on exams rather than their performance in real-life situations. Another major finding was that teachers do not use different testing methods, and this can be regarded as a pitfall in EFL programs.

With such background information on Iran’s pedagogic system, the current study aimed at investigating the feasibility of EFL learners’ using of E-portfolios in the traditionally exam-oriented context of Iran and also to scrutinize the potential advantages and challenges of introducing Mahara as a learning-focused assessment tool to EFL classes. Furthermore, this study tried to investigate the Iranian EFL students’ perceptions and attitudes towards the use of the Mahara e-portfolio platform as an assessment tool.

2. Review of literature

The literature is unanimous about the advantages of e-Portfolios overprinted portfolios. E-portfolios are regarded as easily accessible assessment tools, with the ability to store multiple media, also they can be easily updated, and surely can be utilized to reference the work of learners. (Mohammed et al., Citation2015; Namaziandost, Hosseini et al., Citation2020). Providing learners with the opportunity to reflect on their own learning and more importantly giving teachers valuable chances to provide detailed feedback on their students’ work are two main advantages of implementing e-portfolios into teaching-learning contexts (Ahn, Citation2004).

Yastibas and Yastibas (Citation2015) outlined 10 specific characteristics of e-portfolios. In their review of the literature, they attributed features like being authentic, controllable, communicative, dynamic, personalized, integrative, multi-purposed, multi-sourced, motivational, and reflective to the implementation of e-portfolio system. They argued that e-portfolio is authentic because students will have the opportunity to take responsibility for their learning, so they are required to establish their e-portfolios, reflect on their learning processes and findings, and improve their learning based upon their reflections (Goldsmith, Citation2007; Reese & Levy, Citation2009). The second feature in which they mentioned in their review was the controllable status of the e-portfolio system. In this regard, students are equipped with the ability to organize their e-portfolios, reflect and assess their learning processes, and make necessary changes to their e-portfolios according to their reflections (Goldsmith, Citation2007). The communicative and interactive characteristics of e-portfolio were categorized as the third feature of e-portfolio. Bolliger and Shepherd (Citation2010) and also Lin (Citation2008) concluded that using e-portfolios is enhancing the communicative and interactive skills of students as they will be required to communicate and interact with their peers and teachers to improve their learning using an e-portfolio system. Fourthly, e-portfolio is considered as a dynamic assessment tool since the construction of e-portfolio is experiencing a developing status as a result of the organization of content, collection and selection of artifacts, the self-assessment and self-reflection of the learning process, and improvement made according to self-assessment and self-reflection (Namaziandost, Sawalmeh et al., Citation2020; Yastibas & Yastibas, Citation2015). The fifth characteristic is the personalized feature of e-portfolios. According to scholars like Goldsmith (Citation2007), Schmitz et al., (Citation2010), and Gray (Citation2008) e-portfolios are regarded as personalized tools as students will have the opportunity to form their e-portfolios on their own. The sixth feature of the e-portfolio system was highlighted in the literature as Goldsmith (Citation2007) puts it, “For students, compiling a portfolio provides the opportunity to connect their work in individual courses to the institutional outcomes. Students describe their ability to understand these connections as well as the connections between their own lives and their academic work’’ (Goldsmith, Citation2007, p. 37). Moreover, e-portfolio is multi-purposed in that it can be applied for the assessment of learners’ learning development and institutions’ education programs (Goldsmith, Citation2007), and for finding job vacancies in the future (Goldsmith, Citation2007; Kocoglu, Citation2008; Lin, Citation2008; Namaziandost, Homayouni et al., Citation2020; Reese & Levy, Citation2009). The eighth facet of the e-portfolio assessment system is its multisource-based platform. According to Goldsmith (Citation2007), the reason behind this naming is that e-portfolio provides learners with feedback on their learning, teachers with the assessment of students’ learning development, and institutions with the chance to evaluate their programs, courses, or departments. Ninth, e-portfolio is motivational since it provides the students with the ownership of their learning and leads to the improvement of their skills (Akçıl & Arap, Citation2009; Bolliger & Shepherd, Citation2010; Rhodes, Citation2011). The final feature of the e-portfolio system is reflectivity. The use of the e-portfolio assessment system promotes self-reflection as students are required to reflect on their learning and assess their learning processes via e-portfolios (Goldsmith, Citation2007; Lin, Citation2008; Reese & Levy, Citation2009).

2.1. E-portfolio representing formative assessment

The term e-portfolio could be regarded as a synonym for formative assessment; however, the e-portfolio system can also serve as a tool for summative assessment (EUfolio, Citation2013). In that view e-portfolios function as the storage of student artifacts (Yastibas & Yastibas, Citation2015). On the other hand, e-portfolios for formative assessment can be attributed to what was mentioned in the European commission guide for the use of e-portfolios also known as EUfolio, it introduced e-portfolio for formative assessment as a “collaborative, continuous discourse between teacher and student” (EUfolio, Citation2013, 5) and as with all forms of formative assessment can be used to revisit the teaching and learning processes to accommodate student needs (Black & Wiliam, Citation2010). An E-portfolio system as a pedagogical tool can also enhance formative assessment in the context of the classroom. The platform promotes feedback in the form of a dialogue which leads to building communication between the student and the teacher. This is in line which that of Marshall and Wiliam (Citation2006) in which they claimed that the main purpose of formative assessment is to develop and foster learning and that the way of feedback providing should involve both the teacher and the student. shows the process of how students normally develop their intended work; in this case, a piece of student writing in the e-Portfolio assessment platform. This development process encompasses all three functions of e-portfolios: Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3.

Figure 1. Adapted from e-portfolios and formative assessment.Footnote1

At Level 1 (student repository), the student can store exemplars of work. This work can be used to generate success criteria; the standards by which work will be judged when finished, to determine its success in the eyes of the student and the teacher. At Level 2 (student workspace), the student is engaged in the creation process while in the student workspace and can seek feedback from peers, teachers, parents, and engage in self-reflection. Once the process is completed, the student can demonstrate their learning at the product stage, and display their product in their showcase (Level 3).

2.2. E-portfolio enhancing learning

The implementation of E-portfolios could benefit learning in many ways as it is based on the use of formative assessment to support the development of reflection and self-regulation, these two entities in turn are regarded as integral parts of the learning process (Welsh, Citation2012). The notion of self-based assessment and its impact on the development of students’ learning has been put forth in several studies (Namaziandost, Razmi et al., Citation2020; Nelson & Schunn, Citation2009; Zohar & Dori, Citation2003). According to Welsh (Citation2012), the main findings of the mentioned studies were based on the concept that active participation in the assessment process assists in the development of higher-order skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

As a platform for student self-assessment, e-Portfolio can assist the students in taking control of their learning and becoming more autonomous (Black et al., Citation2004). The concept was thoroughly scrutinized by Black et al. (Citation2004); they asserted that self-assessment provides the learners with opportunities to work at a metacognitive level engaged in self-reflection, students start developing an outline of their efforts that enables them to direct and manage their artifacts for themselves.

The E-portfolio-based assessment platform provides learners with peer-to-peer dialogue and peer assessment. In the same vein, Stefani et al. (Citation2007) concluded that peer-commenting on students’ artifacts is an outstanding encouragement for enhancing the quality and effort that students devote to their work. Moreover, those who comment learn as much from devising their comments as those who receive feedback on their work. In line with the importance of self and peer-based assessment, there is another study conducted by Welsh (Citation2012) in which she asserted that self- and peer-based formative assessment could be regarded as an effective way of promoting self-regulation in students and that this process was fostered by the implementation of the e-portfolio assessment platform.

2.3. Attitudes towards implementing E-portfolio system

Exploring the students’ perceptions towards the implementation of the E-portfolio assessment platform has gained an attraction in the field of educational technology. One study conducted by Wang and Jeffrey (Citation2017) did shed light on college students’ attitudes towards the adoption of e-portfolios in English assessment and learning. The results of their study revealed that the vast majority of participants showed a preference for the e-portfolio assessment platform in comparison to paper-based examinations.

Another investigation conducted by Welsh (Citation2012) was an attempt to explore the students’ perceptions of using the PebblePad e-portfolio platform to promote self- and peer-based formative assessment. In her investigation, the researcher aimed at documenting the experiences of assessment and feedback and PebblePad application on the course and detailing the effect of these on students’ ability to self-regulate learning. The findings of her study indicated that the implementation of the E-portfolio-based assessment platform has the potential to enhance students’ self-regulation.

Even though the implementation of the E-portfolio assessment platform has gained prominence among educators (Yancey, Citation2009), in some cases, teachers expressed that they were excessively overburdened with the workload from the application of the e-portfolio assessment platform (Cambridge, Citation2009; Chang et al., Citation2012) or solely demonstrated that they were lacking necessary training about the proper usage of E-portfolio assessment system (Fong et al., Citation2014). Yancey (2009) carried out a study to show how an e-portfolio assessment platform can be utilized to gather reflections from students. In her review of e-portfolio implementation, she concluded that students who reflected were more engaged and reported more benefits of learning.

2.4. Challenges of E-portfolios implementation

The e-portfolio-based assessment is difficult to implement over a short period (Poole et al., Citation2018). Lorenzo and Ittelson (Citation2005) did shed light on various challenges of implementing e-portfolio system, claiming that before the implementation of e-portfolio assessment, factors like focusing on “hardware and software, support and scalability, security and privacy, ownership and intellectual property, assessment, adoption and long-term maintenance” (p. 8) should be taken into consideration.

Love and Cooper (Citation2004) outlined common challenges that must be addressed before implementing e-portfolios in the context of teaching-learning. They concluded that (1) the focus of implementing the e-portfolio assessment system remains exclusively on the technical side rather than the administrative side; (2) e-portfolio may be utilized for content management purposes, ignoring the fact that it should be an interactive learning tool at the same time; (2) in the design of e-portfolios the Stakeholders’ views or needs are not met or simply ignored; (3) finally e-portfolio assessment system is not fully integrated into the syllabus (Love & Cooper, Citation2004).

Building on the reviewed studies on the feasibility of implementing e-portfolios into the teaching learning contexts, two research questions are demonstrated and addressed.

How do the Iranian EFL students perceive the usability of e-portfolios?

What were their general attitudes towards the integration of e-portfolios in English learning assessment?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

To carry out this research, 160 intermediate EFL learners out of 300 annual students taught English using the Mahara e-portfolio assessment platform in 2013–2017 years were selected through random sampling. The participants were selected from five English language institutes, and their level of general English proficiency was intermediate. Indeed, in each year 2013–2017, the first 32 students who expressed their consent participated in the study. Their age range was between 16 and 18 years old and they were both males and females who were taught English at five English Language Institutes in Ahvaz, Iran. clearly shows the information regarding the participants:

Table 1. Information regarding the participants in the study

3.2. Instruments and materials

3.2.1. E-portfolio platform: Mahara

Mahara is an open-source online e-portfolio system. The developers of Mahara made it free to be used worldwide for educational assessment. Technically speaking, the developers provided the users with a PHP-based project, in other words, the users should run the project on a host with a specific domain. To use the platform, the researchers managed to create their website to host the Mahara e-portfolio system. Consequently, with the help of a web designer, the Mahara went online and it could be reached through https://folioet.ir. It is worthy of mentioning that the web designer had to make some modifications to the PHP project. Some values were added to the original project to make it more applicable to the educational context. The Mahara system encompasses a mechanism that enabled the students to take part in the peer assessment process in an innovative manner. To be able to use their e-portfolio, the students had to create their accounts on the website. Mahara provided each student with his/her e-portfolio in which he/she could store online evidence of achievement. Regarding the Mahara platform, the pieces of evidence that students already stored on the website were called “assets” and could be shared only with individuals chosen by the student. The researchers did manage to establish a feature of subgrouping on the e-portfolio platform of Mahara to provide the students with the opportunity of classifying their assignments and developed pieces of evidence. All in all, each subgroup was given its own named e-portfolio file encompassing four labeled core task folders. During each cohort, students were required to upload their responses to the assigned tasks to their profile on the Mahara platform. Moreover, the completed tasks could be assessed by other students to meet the standards of the peer-correction approach, besides, the teacher was able to evaluate the uploaded pieces of evidence using his profile on the Mahara platform, in other words, teacher correction also was in play for the sake of formative assessment.

3.2.2. Questionnaires

To acquire the quantitative data, two questionnaires (Appendiix 1 and Appendix 2) were administered to students. At the end of the semester, 90 students out of 160 were selected and given the Learners and Learning Student Questionnaire (LLSQ) and an Assessment Feedback Experience Questionnaire (AFEQ). The first one was a constructive questionnaire utilized throughout the semester to gauge the quality of teaching, whereas the second sought to scrutinize the students’ perceptions of the assessment and feedback regarding the use of Mahara. The two questionnaires used in the current study were adapted from Welsh (Citation2012) with minor modifications. The reliability of this questionnaire was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha (r = .896).

The LLSQ questionnaire included 44 items and grouped in six categories comprising nominal and ordinal variables: personal details, including individual identification number, age, gender, 4 items were given for the sake of tutor group; usability of Mahara was covered by 10 items; feedback was measured by the help of 6 items; core tasks were aimed by giving 6 items; the assessment was explored using 5 items, and 11 items were dedicated for learning and teaching. The numerical values were assigned to the participants’ responses for each questionnaire item. Therefore, if a learner marked strongly agree, he received 5 for that item. For agree, numerical values of 4, for neutral, 3, for disagree, 2, and for strongly disagree, 1 were assigned.

The second questionnaire, AFEQ, was adapted from Welsh (Citation2012) followed a similar format but used instead a 6-point Likert scale. Participants were asked to give their comments regarding core tasks (eight items were covered for this topic); information about progress (five items dedicated to this end); study habits (six items); authorship of feedback (five items dealt with this topic); speed concerning offered feedback (one item covered this topic); grading criteria (six items dealt with this issue); the correlation between students’ perception and the shape of teaching (1 item); and students’ attitude towards the quality of their learning (1 item). It is worth mentioning that the reliability of AFEQ was confirmed by conducting Cronbach’s alpha (r = .916).

The two questionnaires were administered, in a closed session, and a return rate of 100% (n = 90) was achieved. The obtained results from the administration of the questionnaires provided the researchers with a demonstration of the sample attributed to each student cohort. To confirm the reliability, questionnaires were not changed throughout the 5 years. To assure content validity, a draft was sent to 30 Iranian EFL students for piloting, at the same language institute as the participants. This produced productive suggestions for the improvement of the questionnaires (e.g., the time needed for completion, length, wording). The administration of the questionnaires was an attempt to explore the extent to which these students utilized the e-portfolios during the implementation stage and their perceptions and attitudes towards the integration of e-portfolios in the EFL context.

3.2.3. Semi-structured individual interviews

The semi-structured interviews were conducted with 50 participants who were chosen via stratified sampling out of 160. Indeed, stratified sampling was carried out based upon three criteria: age, gender, and level of English proficiency. During all the 5 years of the study, the interviews covered 60 hours. To document the interviews, the researchers utilized an audio recorder. To assure reliability, Interview questions were not changed. gives further information about those participants participated in the semi-structured interviews:

Table 2. Information regarding the participants in the semi-structured interviews by sex, age, and year

3.2.4. Focus groups

To obtain the qualitative results from the focus groups, 20 students from the 2017 cohort were invited to participate in two focus groups of six. Consequently, a list of topics and questions was delivered to the participants for the sake of directing the conversations. To obtain more information about the use of Mahara as an assessment platform, two main notions were discussed thoroughly: (1) students’ application of Mahara e-portfolios platform for EFL learning; (2) students’ perceptions and attitudes towards the use of e-portfolio as a substitute for assessment. Finally, all the conversations were documented using an audio-recorder for further analysis.

3.3. Data collection procedure

The current study was conducted at the English language institute, Ahvaz, Iran. The study was carried out with the help of 160 students who were randomly chosen from a pool of 300 students studying English as a foreign language. All the 160 students were taught using the E-portfolio assessment platform each year (2013–2017). The e-portfolio system used, Mahara, is a fully featured e-portfolio, weblog, resume builder, and social networking system. These students were instructed to submit all the course assignments and projects into the secure online repository, and submissions were scanned with a plagiarism tool. Ninety questionnaires were returned. Then, the questionnaires were coded and input into SPSS (version 25). Findings obtaining from the questionnaires were utilized to inform the later focus groups. Moreover, among the 160 selected participants, 50 participants were selected to take part in the individual semi-structured interviews. Nearly 4200 minutes of audio recording were generated, each interview lasting around 30 minutes. All the required 12 questions were answered by the participants taking part in the semi-structured interviews. Both the transcription and analysis were conducted in the source language (Persian) to avoid any loss of meaning. Later, quotes from the interviews and the focus group were translated into English for presentation in this article. Students and teachers were required to select pieces from a student’s combined work throughout learning English as a foreign language, to provide proof that the intended educational goals have been met. The e-portfolios may include:

written compositions

guided writings

diaries

emails or letters to friends

story writing and reflection papers

transcripts of video or audio reports from BBC News, CNN, and VOA

The students’ e-portfolios were focusing on student reflection through the writing of journals and self- and peer-evaluations. During all the cohorts, students who were taught English through the e-portfolio assessment platform were assessed based on two judgment grounds, E-portfolio’s performance, and their paper-based examination, with the former accounting for 70 marks and the latter accounting for the other 30 marks, putting e-portfolio assessment platform at the top place of the conclusion about students’ performance during English learning.

3.4. Data analysis

To analyze the data, Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) software version 25 was used. Firstly, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) test was used to check the normality of the data. Secondly, descriptive statistics including means and standard deviation were calculated. Finally, qualitative analysis was used for the attitude questionnaire.

4. Results

4.1. Questionnaires

The findings of the questionnaire were gathered as the first step of the data collection procedure. To corroborate the results of the administered questionnaires with the notion of feedback, the seven principles of good assessment and feedback practice detailed by Nicol and Milligan (Citation2006) and by Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick (Citation2006) were cross-referenced with the research questions and the resulting framework used to provide grounds for the analysis of LLSQ and AEFQ findings.

4.2. Results of first research question

RQ1. How do the Iranian EFL students perceive the usability of e-portfolios?

One of the “principles of good assessment and feedback practice” (Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick, 2006) is as follows:

“Good feedback practice encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning” (p. 1).

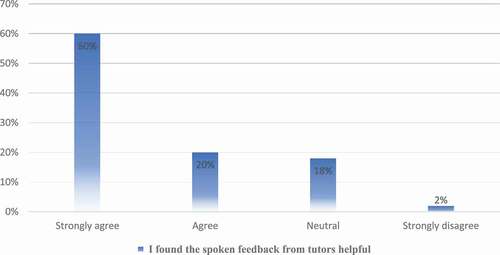

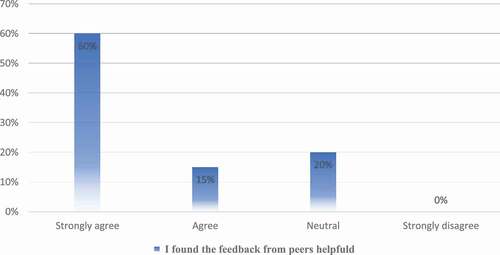

The 5-year questionnaire investigations showed similar trends to Welsh (Citation2012). The students mostly had strongly positive attitudes toward the feedback providing the nature of the E-portfolio assessment platform. The results obtained from the LLSQ questionnaire can be seen in . As it is shown in , the majority of the participants found the received feedback either from their peers or tutor helpful.

Table 3. Participants’ perceptions about feedback providing E-portfolios (n = 90)

As shown in , the researchers did manage to elicit the students’ perception towards different kinds of feedback offered by peers and tutor, in doing so questions 12 to 16 of LLSQ were dedicated to this purpose. Results from the LLSQ revealed that 80% of the respondents found the spoken feedback from tutors helpful (), 75% found peer feedback helpful ().

4.3. Results of second research question

RQ2. What were the students’ general attitudes towards the integration of e-portfolios in English learning assessment?

Regarding the “principles of good assessment and feedback practice” expressed by Nicol and Milligan (Citation2006), another principle was the focus of the current study which is as follows:

“Good feedback practice encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem”. (p. 1)

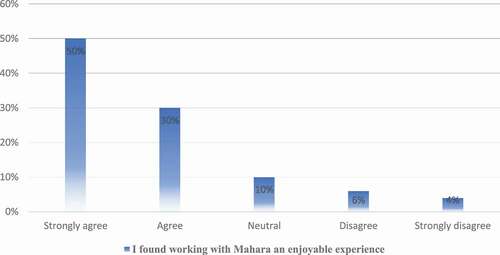

As can be inferred from the data presented in , the majority of the participants demonstrated a positive attitude towards the use of the Mahara E-portfolio assessment platform. Considering the data gathered from administrating the LLSQ, it was revealed that 80% of the participants found the use of Mahara as an enjoyable task, whereas 10% remained undecided about the impact of implementing Mahara in their educational context (). Moreover, 80% of the students who tried using Mahara indicated that they received sufficient guidance to help to use the Mahara technology.

Table 4. Participants’ attitudes towards the implementation of E-portfolios (n = 90)

Nicol and Milligan (Citation2006) put forth the idea that “good feedback practice provides information to teachers that can be used to help shape the teaching” (p. 1). In line with the mentioned principle, the researchers worked on the students’ attitude towards the type of instruction they received through the use of Mahara. In doing so, the students’ responses obtained from LLSQ were gathered and analyzed. The obtained results from the administration of LLSQ can be inferred from , as it can be seen in the below table, 90% of the participants were convinced that the learning outcomes of the module have been achieved, whereas 10% of the respondents remained neutral about the question. Regarding the pace of teaching, 80% of the respondents believed that the pace of delivery of the teaching materials was acceptable, while 20% remained undecided about the posed question. Regarding the method that was utilized to assess the students’ performance throughout the study (i.e., Mahara), over 90% of the participants found the used method of assessment appropriate. Moreover, 90% of the respondents believed that the challenge in the module was pitched correctly.

Table 5. Participants’ attitudes towards the use of Mahara in relation to methods of teaching (n = 90)

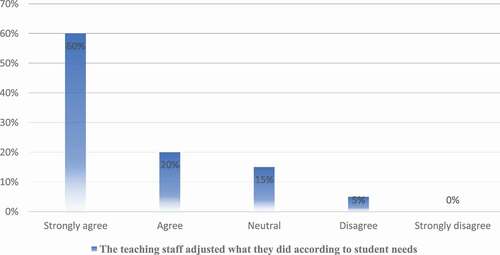

In addition to the completion of the LLSQ, the participants of the study were required to complete the assessment and feedback experience questionnaire (AFEQ). After the administration of the AFEG, the gathered data were then analyzed to be used to scrutinize the students’ attitudes toward the use of Mahara as an assessment platform in English as a foreign language context. About the seven principles of good assessment and feedback practice proposed by Nicol and Milligan (Citation2006), it could be pointed out that there were questions that specifically aimed at gauging the correlation between a good feedback practice and the shape of teaching which were mentioned in AFEQ. demonstrates the responses of the participants regarding question 12 of the AFEQ. As it could be inferred from the data presented in the below figure, 80% of the students found the adjustments made by teaching staff in accordance with their leaning needs, while 15% of the respondents felt undecided about answering the question and 5% were not in favor of the adjustments.

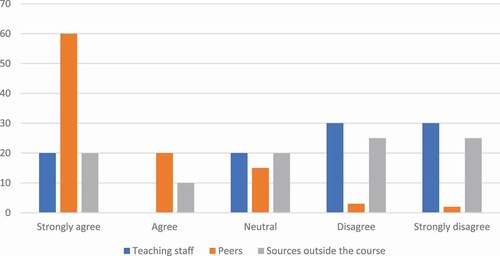

To measure the students’ attitudes towards the sources of feedback they received during the time they were using the Mahara platform as a learning tool, question 20 of the AFEQ was posed. The results obtained from the administered questionnaire regarding question 20 can be seen in , as it can be inferred from the figure below, 80% of the participants concluded that they received feedback on their work from their peers, whereas only 20% of the respondents believed that they sought feedback from teaching staff.

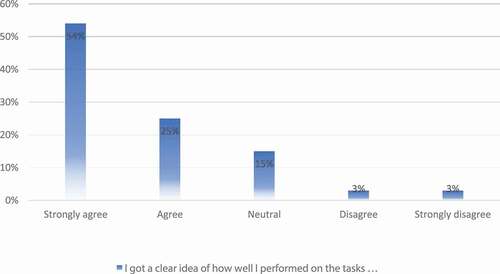

To scrutinize the notion of self-correction concerning the use of the Mahara platform, the data gathered from the administration of the second part of the LLSQ was analyzed, question 2 of the LLSQ2 was the aim in particular. demonstrates the findings of the administrated questionnaire which revealed that 79% of the students were with the idea that the use of Mahara helped them in knowing the level of their gradual performance during their course of their study; however, 15% remained undecided and 6% were not in favor of the notion.

4.4. The qualitative data from interviews and focus groups

Out of 50 students who took part in the semi-structured interviews, 47 individuals (94%) mentioned that the feedback they received from their tutor using the Mahara platform was helpful (). The following comments were selected from students’ responses during the interviews:

Students’ work on Mahara should be made available for tutors as the feedback provided by them could be helpful.

Mahara can provide a chance for my teachers to evaluate my work gradually.

Tutor feedback provided by the Mahara platform helped me during the course of study.

Table 6. Interviewees’ viewpoints as a result of using e-portfolio assessment (questions 5–8) (n = 50)

Moreover, the majority of the participants (95%) taking part in the interviews believed that the feedback submitted by their classmates on Mahara was helpful, whereas 5% considered the peer-feedback unhelpful ().

The Mahara platform made it easier for my classmates to view and assess my work.

It is really interesting that other students can view and evaluate my performance.

The feedback I received from my classmates was totally helpful.

Mahara and self-based assessment

The majority of the participants were with the idea that working with Mahara provided them with an opportunity to evaluate themselves during their semester of learning English as a foreign language. Ninety-seven percent of the students indicated that they were not having any problems with the fact that their work was observed and evaluated by their classmates using the Mahara platform (). The following comments from interviews are selected as representative.

I feel that the observation of my work by my group members is helpful.

Mahar is a good tool for sharing my work with others.

The qualitative data received from the focus groups revealed that the majority of the participants indicated a positive attitude toward the use of Mahara as an assessment tool during their semester of learning English as a foreign language, these findings were in line with the perceptions expressed in the questionnaires and interview results.

6. Discussion

The current study aimed to gauge the feasibility of EFL learners’ using of E-portfolios in the traditionally exam-oriented context of Iran and also to investigate the potential advantages and challenges of introducing Mahara as a learning-focused assessment tool to EFL classes. Moreover, this study was an attempt to scrutinize the Iranian EFL students’ perceptions and attitudes towards the use of the Mahara e-portfolio platform as an assessment tool.

As relates to the obtained results from the administration of the LLSQ questionnaire, the students found the peer feedback they received via the use of e-portfolio platforms helpful (). Moreover, the participants who answered the AFEQ questionnaire indicated that they actively sought feedback on their work from peers in comparison to other sources of feedback (). This finding corroborates the ideas of Yancey (2009), who suggested that students who reflected were more engaged and reported more benefits of learning. In explaining the benefit of the peer-feedback provided by the e-portfolio platforms, it could be mentioned that the E-portfolio platform can offer a feedback cycle within its assessment system which will provide the learners with opportunities to collaborate and share their works with their group members. This is in accordance with the findings of Bolliger and Shepherd (Citation2010) and also Lin (Citation2008) who expressed that the use of e-portfolios can lead to the enhancement of the communicative and interactive skills of students as they will be required to communicate and interact with their peers and teachers to improve their learning using an e-portfolio system. To illustrate, it is noteworthy of mentioning that the Mahara e-portfolio platform which could be regarded as the flag-carrier of formative assessment could replace the teacher-led assessment.

In dealing with the research question, students were found to have a strong positive attitude toward the use of Mahara as an assessment platform in the context of learning English as a foreign language. According to the questionnaire results (), the interview and focus group data (), e-portfolio assessment provided the students with opportunities to take control of their leaning, in other words, they were equipped with the ability to self-regulate the pace of their development in response to the instruction that they have already received when attending their teacher-led classrooms. This finding is in agreement with Wang and Jeffrey (Citation2017) findings which showed that students demonstrated a preference for e-portfolio assessment platforms in comparison to paper-based examinations. In explaining the notion of self-regulation provided by the use of the e-portfolio platforms, it could be asserted that active participation in the assessment process, i.e., the use of e-portfolio platforms, leads to the development of higher-order skills including analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. To put it in another way, during the use of the e-portfolio assessment platform students were able to take the control of their development as a result of instruction. As relates to the results obtained from the administration of the LLSQ, the participants expressed that they found working with the e-portfolio platform an enjoyable experience (). These findings would appear to be linked to the nature of the e-portfolio assessment platform, particularly, the three levels of the e-portfolio process outlined by Abrami and Barrett (Citation2005) namely, repository, workspace, and showcase. Mahara as a representative of the e-portfolio platform provided the students with electronic storage for their works during learning English, also, it was a tool that privileged the students with an ability engage in peer-learning, reflect on their learning development (self-correction), and the artifacts of their peers (peer-correction). Moreover, the e-portfolio platform played a significant role in helping the students to showcase their proficiencies, capabilities, accomplishments, and products during their semester of learning English as a foreign language. All in all, it could be concluded that the main reason behind students’ strong preference toward Mahar in comparison to their previously teacher-led assessment formats was the fact that the e-portfolio assessment platform offered all of the above-mentioned features whereas the traditional assessment methods were not equipped with such characteristics.

More importantly, the use of e-portfolios in English language courses promotes the use of the target language because students are engaged in learning (Schmitz et al., Citation2010). According to Goldsmith (Citation2007), e-portfolios require students to be responsible for organizing and producing the material for a specific purpose, evaluating their work, and reflecting on their findings of their own learning process, experiences, and skills. Consequently, e-portfolios contribute to students’ taking control of their own education and motivating themselves to study (Cepik & Yastibas, Citation2013). Students who prepare e-portfolios in their listening and speaking courses take the responsibility of organizing and preparing their own portfolios, which enables them to participate in learning activities actively. They become aware of their strengths and weaknesses in their e-portfolios because e-portfolios require self-assessment and self-reflection as Rhodes (Citation2011) and Cepik and Yastibas (Citation2013) have stated. They try to overcome their weaknesses and reflect on what they have done in their e-portfolios. According to Lin (Citation2008), e-portfolios can promote interaction and collaboration in class, which motivates and encourages students to complete and improve their e-portfolios benefitting from their peers. The use of e-portfolios in language learning courses enables students to collaborate and interact with their peers and teachers during the e-portfolio process.

E-portfolios are good activities because they encourage students to use the target language outside the classroom. Students need to utilize the target language in a communicative and independent way because they communicate their ideas about the assignments in a way they design and organize on their own. This indicates that students can improve their use of language and master it as Baturay and Daloğlu (Citation2010) have mentioned. The use of language in this way may change students’ point of view about the language. They replace the view that the language is a set of linguistic rules and a classroom subject with the view that the language is used to communicate ideas, as Gonzalez (Citation2009) has emphasized. Teachers keep track of their students’ learning process because e-portfolios store their works (Baturay & Daloğlu, Citation2010). Therefore, they can follow whether their students improve themselves or not. When students complete their e-portfolios, they can also follow their own progress. They have a chance to show their products to their peers and teachers, so this can make them satisfied and motivated.

6.1. How can the Mahara platform shape the ways of teaching?

From the data presented in , it was found that students can provide invaluable information about ways to improve the delivery of instructional content regarding EFL teaching as the participants of the current study demonstrated their attitudes toward notions like the pace of teaching, learning outcomes, the balance of learning and teaching and the selected methods of teaching. This finding is in agreement with Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick’s (2006) findings which suggested that good feedback practice can offer information for teachers that can be utilized to shape the practice of teaching. Consequently, the e-portfolio assessment platform with its feedback providing nature could offer the students opportunities to help teachers reestablish their ways of teaching.

One limitation of the current study was the challenge that was attributed to the use of the e-portfolio assessment platform and that was the grading of students’ performance. In other words, some of the participants expressed that they were not sure about the scalability and the rubrics for which they were going to be assessed using the e-portfolio platforms. These findings were confirmed by Lorenzo and Ittelson (Citation2005) who outlined the scalability issue as one of the challenges attributed to the use of the e-portfolio system. The researchers addressed the issue by providing the students with constructive information regarding the assessment rubrics concerning the use of the e-portfolio assessment platform.

7. Conclusion

The current study was an attempt to explore the feasibility of implementing an e-portfolio assessment platform in the Iranian context and also to scrutinize the Iranian EFL students’ attitudes and perceptions toward the use of Mahara as an assessment tool. Furthermore, this study set out to determine the extent to which the e-portfolio can help students develop their self-regulation as a result of being exposed to high-quality feedback from their peers. The findings of the present study suggest that Mahara as an assessment system could be regarded as a powerful candidate to replace the traditionally exam-oriented assessment systems as it provides learners with opportunities to engage, cooperate, and share their performance with others during their course of learning. Another significant finding to emerge from this study is that learners showed a strong preference over the use of Mahar as opposed to their previous assessment platforms and reported a positive agreement for the use of the Mahara e-portfolio platform in their EFL context.

An implication of the current study is the call for syllabus designers. In other words, the syllabus designers are invited to take into consideration the fast-changing paradigm of assessment. To put it in another way, syllabus designers should bear in mind that the newly developed materials should be in line with innovative ways of assessing the students’ performance. They are strongly urged to consider the use of an e-portfolio assessment platform in the structure of their developed syllabuses. Another significant implication of the present study is for the ministry of Education in Iran (MOEI). The MOEI is strongly invited to provide the grounds for a major shift regarding the assessment system in Iranian schools. The MOEI is urged to take into account the significant role of e-portfolios in improving the EFL context in Iran both in terms of testing and teaching.

This research has thrown up many questions in need of further investigation. It is recommended that further research be undertaken in the following areas: e-portfolio platform and its impact on EFL students’ learning, investigation of other technology-mediated assessment platforms like the PebblePad e-portfolio platform concerning the context of learning English as a second language, implementation of the e-portfolio assessment platform in terms of subjects other than English language learning, like Physics, Biology, and alike.

Finally, it is hoped that the findings of the current study could provide the grounds for a major shift in assessment approaches across the traditionally exam-oriented context of Iran. Moreover, this article could be regarded as proof of the need for an ICT-based assessment platform in the context of Iran.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ehsan Namaziandost

Ehsan Namaziandost was born in Shiraz Province of Iran in 1985. He is a Ph.D. candidate of TEFL at the University of Shahrekord, Iran. His main interests of research are CALL, TEFL, Second Language Acquisition, EFL Teaching and Learning, Language Learning and Technology,Teaching Language Skills, and Language Learning Strategies. His research papers and articles have been published by different international journals. Ehsan did 570 reviews, up to now, for different international journals (See his Publons at: https://publons.com/researcher/3192443/ehsannamaziandost/peer-review/).

Notes

1. Assessment for Learning & e-portfolios. CORE Education (2012): p 24. Accessed 14 April 2015.

References

- Abrami, P., & Barrett, H. (2005). Directions for research and development on electronic portfolios. Canadian Journal of Learning and technology/La Revue Canadienne De L’apprentissage Et De La Technologie, 31(3), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.21432/T2RK5K

- Ahn, J. (2004). Electronic portfolios: Blending technology, accountability & assessment. The Journal, 31(9), 1-19. Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/77087/

- Akçıl, U., & Arap, İ. (2009). The opinions of education faculty students on learning processes involving e-portfolios. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1(1), 395–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.071

- Alan, S., & Sunbul, A. M. (2014). Experimental studies on electronic portfolios in Turkey: A literature review. International Journal of Research in Education and Science, 1(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.21890/ijres.09416

- Barrett, H. C. (2007). Researching electronic portfolios and learner engagement: The reflect initiative. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50(6), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.50.6.2

- Basken, P. (2008). Electronic portfolios may answer calls for more accountability. Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(32), A30–A31. Retrieved from http://www.csun.edu/pubrels/clips/April08/04-17-08E.pdf

- Baturay, M. H., & Daloğlu, A. (2010). E-portfolio assessment in an online English language course. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(5), 413–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2010.520671

- Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2004). Working inside the black box: Assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi Delta Kappan, 86(1), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170408600105

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2010). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009200119

- Bolliger, D. U., & Shepherd, C. E. (2010). Student perceptions of ePortfolio integration in online courses. Distance Education, 31(3), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2010.513955

- Brown, M., Anderson, B., Simpson, M., & Suddaby, G. (2007). Showcasing Mahara: A new open source eportfolio. 82–84. Retrieved from https://www.learntechlib.org/p/46040/

- Cambridge, D., Cambridge, B. L., & Yancey, K. B. (Eds). (2009). Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

- Cepik, S., & Yastibas, A. E. (2013). The use of e-portfolio to improve English speaking skill of Turkish EFL learners. Anthropologist, 16(1–2), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2013.11891358

- Chang, C. C., Tseng, K. H., & Lou, S. J. (2012). A comparative analysis of the consistency and difference among teacher-assessment, student self-assessment, and peer-assessment in a Web-based portfolio assessment environment for high school students. Computers & Education, 58(1), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.005

- Chang, -C.-C. (2001). A study on the evaluation and effectiveness analysis of web-based learning portfolio (WBLP). British Journal of Educational Technology, 32(4), 435–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8535.00212

- EUfolio EUfolio Process Specification. (2013). [Online]. http://mahara.eufolio.eu/artefact/file/download.php?file=39151RetrievedMay11,2019,fromhttps://.google.com/search?hl=en&q=EUfolio+EUfolio+Process+Specification+%5BOnline%5D+2013+Available+from:+http://mahara.eufolio.eu/artefact/file/download.php%3Ffile%3D39151

- Farhady, H., & Hedayati, H. (2009). Language assessment policy in Iran. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 29, 132. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. doi:10.1017/S0267190509090114

- Firoozi, T., Razavipour, K., & Ahmadi, A. (2019). The language assessment literacy needs of Iranian EFL teachers with a focus on reformed assessment policies. Language Testing in Asia, 9(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-019-0078-7

- Fong, R. W. T., Lee, J. C. K., Chang, C. Y., Zhang, Z., Ngai, A. C. Y., & Lim, C. P. (2014). Digital teaching portfolio in higher education: Examining colleagues’ perceptions to inform implementation strategies. The Internet and Higher Education, 20(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.06.003

- Goldsmith, D. J. (2007). Enhancing learning and assessment through e‐portfolios: A collaborative effort in Connecticut. New Directions for Student Services, 2007(119), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.247

- Gonzalez, J. A. (2009). Promoting student’s autonomy through the use of the European Language Portfolio. ELT Journal, 63(4), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn059

- Gray, L. (2008). Effective practice with e-portfolios. Higher Education Funding Council for England, JISC.

- Hamp-Lyons, L. (1997). Washback, impact and validity: Ethical concerns. Language Testing, 14(3), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/026553229701400306

- Herman, J. L., & Golan, S. (1993). The effects of standardized testing on teaching and schools. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 12(20–25), 41–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1993.tb00550.x

- Hinojosa-Pareja, E. F., Gutiérrez-Santiuste, E., & Gámiz-Sánchez, V. (2020). Construction and validation of a questionnaire on E-portfolios in higher education (QEPHE). International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 43(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2020.1735335

- Jahangard, A. (2007). Evaluation of EFL materials taught at Iranian public high schools. The Asian EFL Journal, 9(2), 130–150. Retrieved from http://asian-efl journal.com/June_2007_EBook_editions.pdf

- Kocoglu, Z. (2008). Turkish EFL student teachers’ perceptions on the role of electronic portfolios in their professional development. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 7(3), 71–79. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1102927.pdf

- Lin, Q. (2008). Preservice teachers’ learning experiences of constructing e-portfolios online. The Internet and Higher Education, 11(3–4), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.07.002

- Lorenzo, G., & Ittelson, J. (2005). An overview of e-portfolios. Educause Learning Initiative, 1(1), 1–27. Retrieved from http://electronicportfolio.pbworks.com/f/reading04overview.pdf

- Love, T., & Cooper, T. (2004). Designing online information systems for portfolio-based assessment: Design criteria and heuristics. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 3(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.28945/289

- Luchoomun, D., McLuckie, J., & van Wesel, M. (2010). Collaborative e-learning: E-portfolios for assessment, teaching, and learning. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 8(1), 21–30. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ880096.pdf

- Maher, M., & Gerbic, P. (2009). E-portfolios as a pedagogical device in primary teacher education: The AUT University experience. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 34(5), 4. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2009v34n5.4

- Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2006). English inside the black box. NFER Nelson.

- Mason, R., Pegler, C., & Weller, M. (2004). E-portfolios: An assessment tool for online courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(6), 717–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2004.00429.x

- Mohammed, A., Mohssine, B., M’hammed, E. K., Mohammed, T., & Abdelouahed, N. (2015). Eportfolio as a tool of learning, presentation, orientation and evaluation skills. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 328–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.145

- Namaziandost, E., & Çakmak, F. (2020). An account of EFL learners’ self-efficacy and gender in the flipped classroom model. Education and Information Technologies, 25(2), 4041–4055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10167-7

- Namaziandost, E., Homayouni, M., & Rahmani, P. (2020). The impact of cooperative learning approach on the development of EFL learners’ speaking fluency. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 7(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2020.1780811

- Namaziandost, E., Hosseini, E., & Utomo, D. W. (2020). A comparative effect of high involvement load versus lack of involvement load on vocabulary learning among Iranian sophomore EFL learners. Cogent Arts and Humanities, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2020.1715525.

- Namaziandost, E., Razmi, M. H., Heidari, S., & Tilwani, S. A. (2020). A Contrastive analysis of emotional terms in bed-night stories across two languages: does it affect learners’ pragmatic knowledge of controlling emotions? Seeking implications to teach english to EFL learners. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 49(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09739-y.

- Namaziandost, E., Rezvani, E., & Polemikou, A. (2020). The impacts of visual input enhancement, semantic input enhancement, and input flooding on L2 vocabulary among Iranian intermediate EFL learners. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1726606

- Namaziandost, E., Sawalmeh, M. H. M., & Izadpanah Soltanabadi, M. (2020). The effects of spaced versus massed distribution instruction on EFL learners’ vocabulary recall and retention. Cogent Education, 7(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1792261

- Nelson, M. M., & Schunn, C. D. (2009). The nature of feedback: How different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instructional Science, 37(4), 375–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-008-9053-x

- Nicol, D., & Milligan, C. (2006). Rethinking technology-supported assessment practices in relation to the seven principles of good feedback practice. In Innovative assessment in higher education (pp. 84–98). Routledge.

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

- Oh, J.-E., Chan, Y. K., & Kim, K. V. (2020). Social media and E-portfolios: impacting design students’ motivation through project-based learning. IAFOR Journal of Education, 8(3), 41–58. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f1b9/a20e70d10d3a46e2f7c1d214c09c2fd45d4d.pdf

- Poole, P., Brown, M., McNamara, G., O’Hara, J., O’Brien, S., & Burns, D. (2018). Challenges and supports towards the integration of ePortfolios in education. Lessons to be learned from Ireland. Heliyon, 4(11), e00899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00899

- Reese, M., & Levy, R. (2009). Educause center for applied research. Research Bulletin, 2009(4), 1-12. Retrieved from https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/33329/ECAR-RB_Eportfolios.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Rhodes, T. L. (2010). Making learning visible and meaningful through electronic portfolios. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 43(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2011.538636

- Rhodes, T. L. (2011). Making learning visible and meaningful through electronic portfolios. Change, 43(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2011.538636

- Saad, M. R. B. M., Sardare, S. A., & Ambarwati, E. K. (2013). Iranian secondary school EFL teachers’ assessment beliefs and roles. Life Science Journal, 10(3), 1638–1647. Retrieved fromhttps://www.lifesciencesite.com/lsj/life1003/246_B01918life1003_1638_1647.pdf

- Schmitz, C. C., Whitson, B. A., Van Heest, A., & Maddaus, M. A. (2010). Establishing a usable electronic portfolio for surgical residents: Trying to keep it simple. Journal of Surgical Education, 67(1), 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2010.01.001

- Stefani, L., Mason, R., & Pegler, C. (2007). The educational potential of e-portfolios: Supporting personal development and reflective learning. Routledge.

- Torabi, S., & Safdari, M. (2020). The effects of electronic portfolio assessment and dynamic assessment on writing performance. Computer-Assisted Language Learning Electronic Journal, 21(2), 51–69. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7231711/pdf/IJPH-49-323.pdf

- Wang, P., & Jeffrey, R. (2017). Listening to learners: An investigation into college students’ attitudes towards the adoption of e‐portfolios in English assessment and learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(6), 1451–1463. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12513

- Welsh, M. (2012). Student perceptions of using the Pebble Pad e-portfolio system to support self-and peer-based formative assessment. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 21(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2012.659884

- Yancey. (2009). Reflection on Electronic E-portfolios. In Electronic Portfolios 2.0: Emergent Research on Implementation and Impact (pp. 5–16). Stylus Publishing, LLC. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=_3lXTBvIeNkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA5&dq=Yancey+2009+eportfolio&ots=wk2_5323yX&sig=QZuSeUDHkRAdu-GGR-uA6P3HoyM#v=onepage&q=Yancey%202009%20eportfolio&f=false

- Yang, M., Tai, M., & Lim, C. P. (2016a). The role of e-portfolios in supporting productive learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(6), 1276–1286. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12316

- Yang, M., Tai, M., & Lim, C. P. (2016b). The role of e-portfolios in supporting productive learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(6), 1276–1286. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12316

- Yastibas, A. E., & Cepik, S. (2015b). Teachers’ attitudes toward the use of e-portfolios in speaking classes in English language teaching and learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 176, 514–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.505

- Yastibas, A. E., & Yastibas, G. C. (2015). The Use of E-portfolio-based assessment to develop students’ self-regulated learning in English language teaching. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 176, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.437

- Zohar, A., & Dori, Y. J. (2003). Higher order thinking skills and low-achieving students: Are they mutually exclusive? The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 12(2), 145–181. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327809JLS1202_1

Appendix 1.

Learners and Learning Student Questionnaire Part 1

Appendix 2.

Learners and Learning Student Questionnaire Part 2

Assessment and Feedback Experience Questionnaire