Abstract

This study examined the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of inclusive education of pre-service teachers in Nigeria and South Africa by surveying 217 Nigerian and 266 South African pre-service teachers using a cross-sectional survey research design. A self-developed questionnaire was used for the data collection. The questionnaire was pilot-tested among pre-service teachers from a public university in Tanzania. Data were descriptively and inferentially analysed (means and standard deviations) using a 2 × 3 factorial multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). The study found a significant interaction between country and gender, with a significant main effect for gender as well as for country. The results indicated a significant MANOVA and a follow-up analysis of the variance test showed a statistically significant difference in the knowledge of pre-service teachers about inclusive education in terms of gender with female pre-service teachers having the highest mean score. The study also indicated a significant difference in the attitudes of pre-service teachers towards inclusive education in terms of their country, with Nigeria having a higher score than South Africa. The implications of a socially just society are discussed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The success of implementing inclusive education largely depends on teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of inclusion. Importantly, teachers’ understanding of the philosophy and practice of inclusive education is influenced by their pre-service training. The literature revealed that pre-service knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of inclusive education vary across regions, provinces, and nations. While no previous studies have wholesomely assessed Nigerian and South African pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perception of inclusive education, this comparative study presents the examination of the knowledge, attitude, and perception of inclusive education among pre-service teachers from a Nigerian public university and a South African public university. The findings revealed a significant difference in the attitudes of pre-service teachers towards inclusive education in terms of their country, with Nigeria having a higher score than South Africa

1. Introduction

Inclusive education in Nigeria and South Africa is a concept based on the philosophy and practice that seeks to enhance the full inclusion of individuals with disabilities into mainstream society without any iota of discrimination and to improve and sustain social justice. Inclusive education is a term that is mostly used to mean an approach that seeks to address the learning needs of all learners irrespective of their abilities or disabilities. Inclusion implies that learners with disabilities (e.g., those with physical, mental and or sensory impairment, mobility limitations, intellectual disabilities, learning disabilities, language and/or behaviour disorders and autism spectrum disorders among others) and their peers without disabilities are given the same privileges and opportunities to learn under the same condition without been marginalised (Opoku et al., Citation2020; Osisanya et al., Citation2015).

According to Ajuwon (Citation2008), Armstrong et al. (Citation2010), and Hamid et al. (Citation2015) the term ‘inclusion’ is a concept that is intimately connected to the larger movement and campaign for equality, human rights, and social justice. However, the concept of inclusion, its popularity, and the mode of realisation of its policy and practice may differ among many African nations, but the goals of inclusive education are considerably alike. The concept of inclusion is based on the Salamanca Framework for Action (UNESCO, Citation1994), which has been enshrined in various African educational policy documents as a guide to direct the activities of pre-service teachers in Africa to enhance the process and product of education for learners with disabilities. In line with this framework, many African countries—particularly Nigeria and South Africa—have embraced inclusive education, as documented in the National Policy on Education (NPE) (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004) and the Education White Paper 6 (Department of Education, Citation2001). These documents stipulate the accommodation of all learners, irrespective of their intellectual, emotional, physical, and linguistic conditions. Interestingly, the NPE in Nigeria and the White paper in South Africa stipulate equalised educational opportunities for all learners at all levels through the integration of learners with disabilities into regular classrooms devoid of artificial barriers along with free education. These are undoubtedly lofty goals that are presented in various policy documents geared towards the provision of quality education for learners with disabilities.

2. Literature review

As a signatory to the international agreement on the Salamanca Framework of Action on Inclusive Education (UNESCO, Citation1994) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) (United Nations, Citation2007), many African nations—including Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa—have adopted and incorporated the principles of the aforementioned international documents and frameworks. The adoption of international instruments is geared towards the advancement of quality education and the reduction of inequalities based on the principles of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4 and 10 (United Nations, Citation2015). Hence, Opoku et al. (Citation2020) observed that access to quality education and the promotion of the rights of people with special needs have been enshrined into various policies and programmes of many African nations such as Nigeria and South Africa.

Based on the United Nations resolution and other international agreements, academics in higher educational institutions in Nigeria and other African countries have continually interrogated the philosophy and practice of inclusive education until the adoption of the revised National Policy on Education in 2004 (Agunloye et al., Citation2011; Eskay, Citation2009; Garuba, Citation2003), the Universal Basic Education Acts of 2008 (Ajuwon, Citation2008), and the National Policy on Special Education (Federal Ministry of Education, Citation2015). According to Agunloye et al. (Citation2011), the adoption and practice of inclusive education in Nigeria was influenced by political instability and socio-economic and cultural constraints. However, tremendous improvements in knowledge and attitude towards the practising of inclusive education have been recorded (Adetoro, Citation2014; Adigun & Adedokun, Citation2013; Eskay, Citation2009).

Much of the observed improvements in knowledge and attitude towards inclusive education has been observed by Adigun and Adedokun (Citation2013), Eskay (Citation2009), and Fakolade et al. (Citation2017). This may be attributed to early, existing institutions of higher learning such as the Federal College of Education (Special) Oyo, which was established in 1977, and the Department of Special Education in various universities and all geopolitical zones in the country that specifically train and prepare teachers for learners with special needs. In addition, the inclusion of a mandatory course that introduces all teacher trainees to the rudiments of special needs education may have contributed to the acceptance of inclusive education in Nigeria. Ajuwon (Citation2012), Oluremi (Citation2015), and Osisanya et al. (Citation2015) further noted that the promotion of positive attitudes towards the practise and implementation of inclusive education in Nigeria has been largely centred on developing teachers’ capacity as major players in the process than parents of learners with special needs.

On the other hand, in South Africa, after the demise and farewell to apartheid in 1994, government policies were largely overhauled based on the tenets of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act No. 108 of 1996 (Republic of South Africa, Citation1996). These tenets discourage any form of discrimination against anyone, including those living with a disability. In furtherance of equality and social justice for all, the Department of Education (Citation2001) initiated reviews of educational policies to accommodate and ensure equal and non-discriminatory access to education for all, irrespective of disabilities. The policy review process resulted in the educational policy referred to as Education White Paper 6, which advocated and promoted the inclusion and maximum participation of learners with disabilities in a regular classroom and the facilitation of their learning needs with the required educational support system (Department of Education (DoE), Citation2005). Interestingly, an inclusive educational policy advanced by the DoE through the Education White Paper 6 presents huge tasks and responsibilities for teachers. In other words, teachers were tasked with the provision and fostering of equal access to learning devoid of barriers and to ensure meaningful participation in the teaching and learning processes.

As indicated by Donohue and Bornman (Citation2014), Hay (Citation2003), and Pillay and Di Terlizzi (Citation2009), a shift from regular classroom teaching to teaching in an inclusive education setting places a strain on teachers. Based on the assertions of the aforementioned studies, it is assumed that educators’ knowledge, perception, and preparedness for inclusive education in South Africa may have been influenced by inadequate knowledge about inclusive education. Regrettably, inadequate knowledge and understanding of inclusive educational practices may further hamper the perception of inclusive educational practices and attitudes towards its philosophies and practices. Studies have raised concerns about the rate at which various educational policies geared towards inclusive education have been implemented (Adetoro, Citation2014; Nketsia & Saloviita, Citation2013; Omede, Citation2016; Walton, Citation2018). Adigun and Adedokun (Citation2013) as well as Ajuwon (Citation2008) expressed concern about the role of teachers in their practising of inclusive education and thus emphasised the need to adequately equip and re-orient the teachers for the intricacies of inclusive education through adequate training and retraining.

To this end, many African institutions of higher learning have institutionalised inclusive education in their teacher education programmes, with the aim of creating adequate human resources in the form of teachers for learners with diverse needs. However, despite legislation and policies, inclusive education in Nigeria and South Africa remains nascent (Walton, Citation2018), and teachers’ attributes and ability to teach in inclusive classrooms have been questioned in scholarly conversations with little attention paid to the knowledge base of these teachers-in-training. This paper explores the knowledge base, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers in Nigeria and South Africa, with a view to ascertaining their readiness to teach learners with diverse educational needs. As stated by Avramidis and Norwich (Citation2002), teachers’ knowledge of inclusive education is essential for the successful implementation and the achievement of the Salamanca Framework of Action. Additionally, the understanding of inclusive education and how policy is translated into practice relies heavily on teachers’ knowledge and thus becomes a prerequisite for the implementation of reforms that influence inclusive practices (Baguisa & Ang-Manaig, Citation2019; Landasan, Citation2016).

Kamenopoulou et al. (Citation2016) and Osisanya et al. (Citation2015) affirm that knowledge and an understanding of inclusion are key factors for its successful implementation; however, Baguisa and Ang-Manaig (Citation2019) state that the knowledge of inclusive education among teacher trainees is very low. Other studies have also criticised the knowledge base of teachers at various levels. For instance, a report by AlMahdi and Bukamal (Citation2019) showed that 17.4% of the candidate teachers from the Bay District in the Philippines had poor knowledge about an inclusive policy, while others demonstrated a moderate understanding of the concept. Earlier studies (Pottas, Citation2005; C. R. Dapudong, Citation2014; Wanjiru, Citation2017) have also reported that many potential teachers exhibit partial knowledge of inclusive education as an educational philosophy that can conveniently accommodate all learners, irrespective of their diverse learning needs or location. According to Wanjiru (Citation2017), teachers from Kenya had insufficient knowledge of what was required for the successful engagement of teachers to drive and achieve the goal of inclusion. Similarly, Timothy et al. (Citation2014) noted that the majority of teachers in Nigeria had limited knowledge about inclusive education, and a study by Hay et al. (Citation2001) among 2577 teachers in South Africa stated that teachers from South Africa lacked definite knowledge about inclusive education (Timothy et al., Citation2014).

No attempt was made by C. R. Dapudong (Citation2014) to underscore the importance of a strong knowledge base for the implementation of inclusive education. Instead, he averred that the success of inclusive education largely depended on teachers’ attitudes, and he favoured a positive attitude towards inclusive education by teachers. Importantly, teachers need to be favourably disposed and sensitive to the dynamics of curriculum adaptation and modification as well as to the characteristics and needs of all learners in order to efficiently work with other stakeholders to ensure the successful implementation of inclusive education. Studies by Avramidis et al. (Citation2000), Haugh (Citation2003), and Srivastava et al. (Citation2017) state that when teachers are adequately prepared, they tend to develop more positive attitudes towards and confidence in teaching in inclusive classrooms. The literature also indicates that there is a strong association between the improved academic performance of learners with disabilities in inclusive schools and the supportive attitudes of their teachers (Bartley, Citation2014; Ross-Hill, Citation2009).

Abang (Citation2005) and Ozoji (Citation2005) note that both positive and negative teachers’ attitudes exist within the same country context, but this variation in attitude is not peculiar to Nigeria, as it is also applicable to other developing and developed country contexts across the world. While most of the studies performed to date (Bartley, Citation2014; C. R. Dapudong, Citation2014; Ross-Hill, Citation2009; Wanjiru, Citation2017) have focused on practising teachers, there is growing evidence of the need to examine student teachers’ attitudes towards teaching in inclusive settings. The results of the study by C. R. Dapudong (Citation2014) indicate that teachers from the eastern seaboard region of Thailand strongly believe that students with special educational needs should have equal opportunities to participate in all school activities. However, this study fails to prove that the variation in the attitudes is based on the teachers’ genders. In other words, Dapudong’s study was of the view that the gender of teachers may not necessarily influence their attitude towards inclusive education, but cultural implications may have necessitated teachers’ actions and attitudes towards the principles and practise of inclusive education.

Cultural perspectives, especially in Africa, have greatly influenced perceptions and attitudes towards disability and the inclusion of persons with disabilities in general classrooms. As indicated by Agbenyega et al. (Citation2005), Avoke (Citation2002), Murphy (Citation1996), Eskay et al. (Citation2012), Jelagat and Ondigi (Citation2017), and Donohue and Bornman (Citation2014), families across different cultures, clans, and ethnic groups in Africa have expressed varied reasons that may have informed their decision towards disabilities and inclusion of persons with special educational needs in the general classroom. As noted by Avoke (Citation2002) and Jelagat and Ondigi (Citation2017), beliefs and spiritual reasons, intergenerational curses and reprisals, and violations of social and cultural taboos from punishment or retribution for past sins from gods may have informed Africans’ attitudes towards people with special needs. Among the Ghanians, particularly those from Northern Ghana, persons with congenital disabilities are considered inhuman (Avoke, Citation2002). Agbenyega et al. (Citation2005) state that such negative beliefs have greatly posed a threat with regard to attitudes towards persons with special needs and inclusion of the same into mainstream society.

Abosi and Ozoji (Citation1990) along with Adetoro (Citation2014) noted the cultural implications of disability in Ghana are not very different from those recorded in Nigeria. In Nigeria, reports from the studies of Abosi and Ozoji (Citation1990) as well as Adetoro (Citation2014) showed that cultural beliefs that attributed disabilities to some local ancient mythology such as witchcraft and retribution for offences of their forefathers from gods cumulate into the social delineation of children with disabilities in the cultures of the Igbos and Yoruba. Similarly, among the Zulus from the province of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, Maher (Citation2009) in his study of aid workers, children, parents, and teachers found that cultural beliefs necessitated the primary ostracization of learners with disabilities and inclusive education for them. Interestingly, irrespective of gender, Makhonza et al. (Citation2019) note that the Yoruba from Nigeria believe in the philosophy of Omoluabi, while the Zulu from South Africa believe in the philosophy of Ubuntu/Botho, which interestingly speaks about humaneness and acceptance of positive attitudes towards all. The philosophy of Omoluabi and Ubuntu/Botho both project the right perspective to positive social interpersonal relationships among members of a community geared towards critical, liberal, and progressive democratic thinking.

Nevertheless, despite the cultural philosophy of Omoluabi among the Yoruba from Nigeria and Ubuntu/Botho among the Zulu from South Africa, studies from both countries have expressed unresolved concerns about teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Thus, while there is yet to be a comparative cross-cultural study from both countries, this present study brought to fore a comparative empirical evidence concerning the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers towards inclusive education in Nigeria and South Africa.

Even so, AlMahdi and Bukamal (Citation2019) and Fakolade et al. (Citation2017) do prove the variation and state that a significant difference exists among male and female teachers based on their attitudes towards inclusive education, with female teachers having a higher positive attitude towards inclusive education than males. Irrespective of the gender influence on attitudes towards inclusive education, decisions and actions are taken based on the perceptions of individual teachers about the quality of the education in an inclusive classroom and how such a goal of equal education might be attained and sustained for all children. Hence, how pre-service teachers in developing countries perceive the workability of inclusive education may be a potential factor that moderates their capability to embrace an inclusive classroom. Over the years, there has been an increase in debates about teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education, but many of these debates and studies have centred on the perceptions of practising teachers (Daane et al., Citation2000; N. M. Nel et al., Citation2016; Magumise & Sefotho, Citation2018), with little attention paid to prospective teachers. Blackie (Citation2010) and Daane et al. (Citation2000) have expressed concern about teachers’ negative perceptions of the benefits and effectiveness of inclusive education in schools and teachers’ willingness to accept, accommodate, and effectively teach children with special needs in their classrooms. Previous studies have shown teachers’ negative perceptions about inclusive education, and Cheng (Citation2011) has reservations about teachers’ competency and readiness to teach in an inclusive setting, despite the teachers in that study expressing positive perceptions of and a belief in the benefits of inclusion of special needs students.

Recent studies in Southern Africa (e.g., Adewumi & Mosito, Citation2019; N. M. Nel et al., Citation2016; Magumise & Sefotho, Citation2018; Mphongoshe et al., Citation2015; N. Nel et al., Citation2011) have been unable to agree on how teachers perceive inclusive education programmes. Two studies have reported positive perceptions of inclusive education in Zambia and South Africa, respectively (N. M. Nel et al., Citation2016; Magumise & Sefotho, Citation2018), while Adewumi and Mosito (Citation2019), Mphongoshe et al. (Citation2015), and N. Nel et al. (Citation2011) in their studies found that the perception of some teachers in South Africa about inclusive education was not encouraging. Variations occur in the reports of various studies with respect to the observed differences in either in-service or pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of the workability of inclusive education—especially in secular, multi-ethnic, and pluralistic African societies. These variations are perhaps functions of identity, dignity, and diversity in humans. Hence, research on teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education is still inconclusive, and this is exacerbated by a dearth of cross-national studies that explore the place of pre-service teachers of different genders in the process, implementation, and prospective success of inclusive education programmes in developing African nations. Al Abduljabber (Citation2006) and R. Dapudong (Citation2013) both recommend a cross-national study of inclusive education to further understand the differences in theories and practices of inclusive education.

3. Theoretical framework

The bioecological systems theory (BST) (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, Citation2005) provided the framework for this study. The BST was used to explore the interaction between humans and the environment as it relates to the inclusive school environment. According to Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation2005) theory, there is an interconnectedness of process, person, context, and time, which influences human development through the following five subsystems: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. This process explains the activities of humans in their environments (in this study, universities and countries). ‘Person’ refers to the individual characteristics of humans such as age, gender, race, and how they interact with their immediate environment. ‘Context’ refers to the environmental situation and time in which various processes occur. Bronfenbrenner (Citation2005) believes that the knowledge, attitude, and perception of an individual about a specific concept and context (inclusive education) may be influenced. This theory also attempts to explain the differences in development, competencies, and knowledge of an individual because of the structure of the society in which they live.

Based on Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation2005) theory, Anderson et al. (Citation2014) and Baguisa and Ang-Manaig (Citation2019) were convinced that environmental and contextual factors mediate inclusive educational programs that place high value on the provision of holistic education to learners with disabilities without barriers. Thus, Adigun and Adedokun (Citation2013), Geldenhuys and Wevers (Citation2013), and Singal (Citation2006) posit that Bronfenbrenner’s framework provides a better understanding as it serves as a basis for interrogating the practices of inclusive education vis-à-vis the development of structure, systems, and individuals within the systems. Geldenhuys and Wevers (Citation2013) and Singal (Citation2006) asserted that an exploration of activities within and among the individual with the system will propel desired changes within the system. Therefore, using the BST as a theoretical framework, this study investigated pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about inclusive education in two African countries.

4. Current study

Past studies have examined the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of teachers—especially in-service teachers—regarding the practise of inclusive education in developed countries; notably, some have taken place in developing African countries. However, there is a dearth of comparative cross-sectional studies on the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers about inclusive education. More specifically, how these differ between pre-service teachers from a West African country (Nigeria) and those from a Southern African country (South Africa). Therefore, this study was designed to bridge this research gap by analysing the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers from Nigeria and South Africa in terms of inclusive education. The study sought to understand how the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers from the two countries differed and whether the observed differences were influenced by gender. It is expected that the findings of this study will inform better policy decisions and promote the practise of inclusive education in Africa. In addition, while this study contributes to the existing literature on inclusive education, the findings of this study also provide a better understanding of pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of inclusive education.

5. Materials and methods

6. Research design

A descriptive quantitative research design of a comparative cross-sectional study was adopted for this study. The African countries of Nigeria and South Africa and two publicly funded universities were selected for this study.

6.1. Participants

Pre-service teachers from the faculty of education of a publicly funded university in Nigeria and South Africa were purposively selected for the study. Furthermore, one of the two public universities in Oyo State, Nigeria, was randomly selected. Similarly, in South Africa, a random sampling technique was adopted to select one out of the two publicly funded universities in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. The participants from Nigeria were all native Yoruba speakers from the southwest region of Nigeria, while those from South Africa were from the province of KwaZulu-Natal, and their native language was isiZulu. All participants had English as a language of academic instruction at their universities. Hence, participants had good reading and writing skills in the English language. Using a convenience sampling method (Sedgwick, Citation2013), a total of 483 pre-service teachers were randomly sampled during the second semester of the 2018/2019 academic session. Participants had a mean age of 26.3 years.

6.2. Measures

A structured, self-developed questionnaire, pre-service teachers, and inclusive education was used for data collection. The questionnaire was subdivided into three sections that measured the knowledge (α = 0.73), attitudes (α = 0.81), and perceptions (α = 0.79) of the pre-service teachers about inclusive education. Each section of the questionnaire was designed using a 4-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree.

The knowledge subscale had 12 items, the attitude subscale had 7 items, and the perception subscale had 13 items. Examples of items on the knowledge subscale included: ‘I do not have the knowledge and skills required to teach learners with disabilities’; ‘Inclusive education programmes provide different students with opportunities for mutual communication’; and ‘Inclusive education promotes understanding about disabilities and makes others accept individual diversity’. Examples of items on the Attitude subscale included: ‘Academically-talented students will be isolated in the inclusive classrooms’; and ‘I cannot teach in a school practising inclusion’; ‘I feel that inclusion increases teachers’ workload’; ‘I feel inclusion can work at all schools’; and ‘Learners should be removed from the class to receive any specialised academic support’ were some of the items that formed the perception subscale of the research instrument.

Scores on the knowledge subscale ranged from 27 to 45, attitude subscale scores ranged from 10 to 24, and perception subscale scores ranged from 26 to 43. High scores on the subscales meant that participants were highly knowledgeable about inclusive education, had positive attitudes towards it, and perceived inclusive education to be beneficial and important.

6.3. Validity and reliability of the instrument

The research instrument used for data collection in this study was a self-developed questionnaire. Thus, there is a need to validate the instrument and ensure its reliability. The researcher ensured the content validity of the questionnaire by having it carefully examined by experts in inclusive education, psychology, and social work. The researcher created the questionnaire using a Google form, and 30 (14 males and 16 females) pre-service teachers from the faculty of education of a public university in Tanzania answered the questionnaire between 9 July and 18 July 2019. Responses gathered from the 30 pre-service teachers were subjected to a reliability analysis to determine the internal consistency of the instrument. For this study, the three subscales of the research instrument—knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions—had Cronbach’s alphas of 0.81, 0.73, and 0.79, respectively.

6.4. Data collection procedures

Data were collected from students from the faculty of education of a public university in Nigeria and South Africa between 14 July and 30 September 2019. Students who had completed the mandatory six-month professional practice in teaching were randomly sampled, and they responded to the questionnaire in English and not in their native languages. The questionnaire was initially designed using a Google form for easy access by the participants; yet, the response was low, and it became imperative to print the questionnaire for the respondents. The online response rate of the participants was 126 (26.09%), while the paper instrument received a response rate of 73.91%. The participants were duly informed about the essence of the study and gave their consent prior to participating in it.

6.5. Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to determine the measures of central tendencies (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation) of the independent and dependent variables. The independent variables were gender (male vs. female) and country (Nigeria vs. South Africa), while the dependent variables were knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions. Inferential statistics using the 2 × 3 factorial MANOVA were generated to determine the differences in the participants’ locations and genders vis-à-vis their knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of inclusive education in their country of residence. A MANOVA was used to assess the differences in the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of male and female pre-service teachers regarding inclusive education in Nigeria and South Africa. The assumptions of the MANOVA were assessed for multivariate normality, homogeneity of variance, and the quality of the variance error of the dependent variables across the independent variables. The MANOVA was considered suitable for the analysis of data collected in this study because of the dimensions of the variables examined. According to Grice and Iwasaki (Citation2007), a MANOVA is suitable for the analysis of data with one or more factors (each with two or more levels) and two or more dependent variables. The IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22, was used to analyse the data generated from the questionnaire.

7. Results

7.1. Demographic distribution of the participants

A total of 217 pre-service teachers from Nigeria and 266 pre-service teachers from South Africa participated in the study. This population of participants across the two countries was divided into Nigeria (44.93%) and South Africa (55.07%). A total of 56.20% and 42.48% of men participated in the study from Nigeria and South Africa, respectively. Similarly, 95 (43.80%) female pre-service teachers from Nigeria responded to the research instrument, while in South Africa, 153 (57.52%) female pre-service teachers participated in the study. The study demonstrated a range of 27 to 45, 10 to 24, and 26 to 45 for the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions subscales, respectively. This study showed no evidence of either ceiling or floor effects for knowledge (M = 35.93, SD = 3.52); attitudes (M = 17.50, SD = 2.29); or perceptions (M = 34.39, SD = 3.96). Further revelations in show that pre-service teachers from South Africa had higher mean scores on knowledge (M = 36.28, SD = 3.49) about inclusive education than Nigerians (M = 35.51, SD = 3.53). However, pre-service teachers from Nigeria had a greater mean value than their counterparts in South Africa for their attitudes (Nigeria, M = 17.92, SD = 2.24; South Africa, M = 17.49, SD = 2.29) about and perceptions (Nigeria, M = 35.75, SD = 3.53; South Africa, M = 33.28, SD = 3.96) of inclusive education. Across gender divides, shows that female pre-service teachers had higher mean scores on the knowledge subscale (M = 36.69, SD = 3.86) than their male counterparts, while male pre-service teachers had higher mean scores on the attitudes subscale (M = 18.11, SD = 2.25), as well as the perceptions subscale (M = 35.80, SD = 3.47).

Table 1. Results for the test of homogeneity of variances

Table 2. 2 × 3 Factorial MANOVA test

7.2. Statistical assumptions

Insight into the multivariate normality assumption was determined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The Shapiro–Wilk test was employed to test the univariate normality of the dependent variables (knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to determine the normality of distribution because the dataset was less than 2,000. The MANOVA assumptions revealed that data were normally distributed for knowledge (w = .985, p = .000), attitudes (w = .972, p = .000), and perceptions (w = .982, p = .000) based on the Shapiro–Wilk test. Furthermore, the MANOVA assumptions were tested using the Mahalanobis distance, which gave a maximum value of 11.893. The value of 11.893 was less than the critical value of 13.82 in the Mahalanobis distance; consequently, it was assumed that the multivariate normality assumption was met. The assumption that the dependent variables would be correlated with each other was determined using the Pearson (bivariate) correlation in the moderate. The correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation among the variables (p < 0.001), suggesting the suitability of the MANOVA. Additionally, the Box’s M test value of 180.99 was associated with a p-value of 0.000, which was interpreted as a non-significant (Huberty & Petoskey, Citation2000) established guideline. Thus, the covariance matrices between the groups were assumed to be equal for the purposes of the MANOVA. Furthermore, a Levene’s test was performed to assess whether the null hypothesis that indicated an error variance of the dependent variable was equal across groups. The statistical report in shows that the assumption was observed to have been met for the participants’ attitudes towards inclusive education (p > 0.05) but not for the knowledge and perceptions of the participants (p < 0.05) towards inclusive education.

There is an established assumption in the MANOVA that when there are two independent variables and the multivariate test statistics are unequal, the Wilks’ lambda distribution cannot be used to test for significance; instead, Pillai’s trace must be employed to test for significance. Hence, Pillai’s trace was chosen to test the significant interactions in the study. As reported in , there was a significant interaction between the countries (Nigeria and South Africa) and the genders (male and female) of the participants (Pillai’s trace = 0.016, F = 2.64; p = 0.05, η2 = 0.016). This implies that 1.6% of the variance in pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about inclusive education could be explained by the interactive effects of location (Nigeria vs. South Africa) and gender. Therefore, the results showed minimal effects.

To further reveal the significant main effects of the gender and country location of the participants, the results in show a significant main effect for gender (Pillai’s trace = 0.044, F = 7.304; p = 0.001, η2 = 0.044) and country (Pillai’s trace = 0.133, F = 24.43; p = 0.001, η2 = 0.133). This result could be seen as having a total of 4.4% and 13.3% variance in pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about inclusive education, which could be explained by their gender differences and country specificities, respectively. The obtained degree of variance in the pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about inclusive education was indicative of the cultural influence on pre-service teachers about inclusive classrooms/education (Aurah & McConnell, Citation2014; Cohen, Citation1988). Subsequently, a univariate analysis was conducted as a follow-up protocol to ascertain the differences between gender (male vs. female) and countries (Nigeria vs. South Africa) across the dependent variables.

The univariate result revealed a statistically significant difference in the knowledge of the pre-service teachers about inclusive education with regard to gender (F = 20.175, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.40), with female pre-service teachers having a higher mean score. Furthermore, demographic results showed that female participants from Nigeria had a higher mean score when compared with South African female pre-service teachers. This implies that South African female pre-service teachers had a slightly lower level of knowledge about the concept and intricacies of inclusive education than their counterparts in Nigeria. Unlike female participants, South African male pre-service teachers had a higher mean score for inclusive education knowledge than their Nigerian counterparts. Correspondingly, a significant difference was found among participants from the two countries, and the effect size was determined to be 40%.

The study also found a significant difference in the attitudes (F = 12.423, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.250) of the pre-service teachers towards inclusive education based on their country, with Nigeria having a higher score than South Africa. This implies that pre-service teachers from Nigeria had a relatively higher positive disposition towards inclusion than their South African counterparts, with an effect size of 25%. While the study showed a statistically significant difference in the attitudes of pre-service teachers towards inclusive education, no statistically significant difference was found for gender differences across the two countries. Similarly, the perceptions of inclusive education between the two countries were significantly different (F = 50.99, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.096). The study revealed that pre-service teachers from Nigeria had a higher score on how they perceived the inclusive education programme than those from South Africa. A further univariate analysis was also conducted to assess if there was a significant interaction between the countries (Nigeria vs. South Africa) and gender (male vs. female). The results in Table 3 reveal that there was no significant interaction between country and gender across the knowledge (F = 4.709, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.10), attitudes (F = 1.469, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.030), and perceptions (F = 0.549, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.001) of the pre-service teachers towards inclusive education.

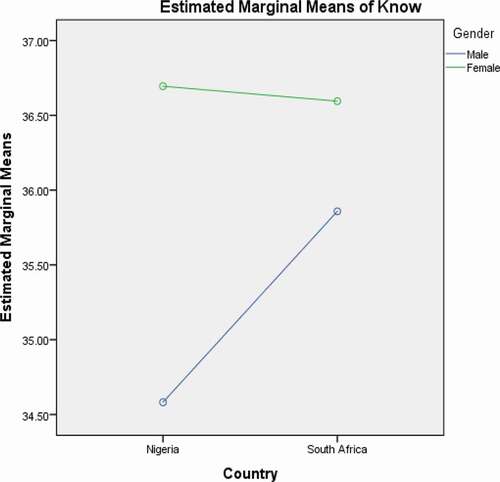

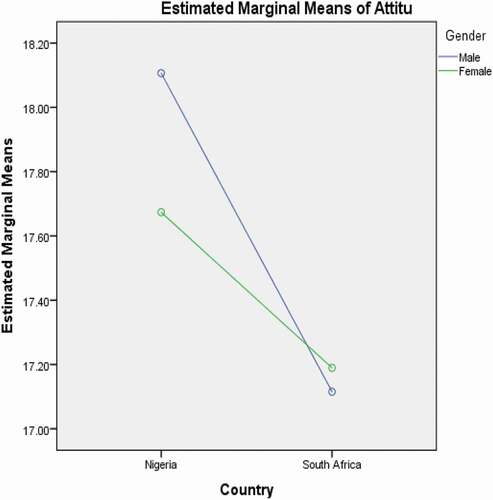

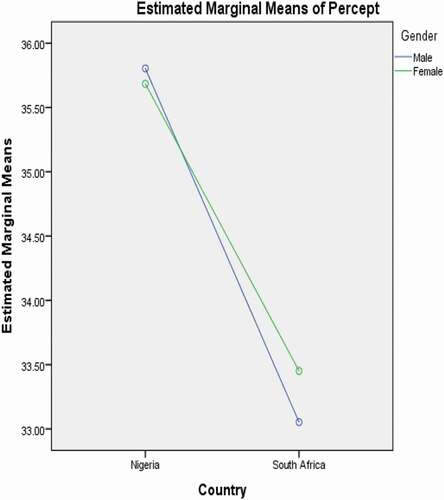

In addition, a simple slope was plotted to obtain a better understanding and clarity of the overall pattern of the interactions and to further establish the factor that predicted whether the participants’ location (Nigeria or South Africa) was significantly related to the dependent variables. A graphical presentation of the graphs in show no parallel slopes, while present interactive slopes. This was an attestation that only the attitudes and perceptions of the pre-service teachers had significant interactions across country and gender. In , no interaction was found between male and female participants vis-à-vis their countries. Although both male and female pre-service teachers from South Africa had better knowledge and perhaps an understanding of inclusive education than their Nigerian counterparts.

Figure 1. Simple plot of interaction effects between country and gender on knowledge of inclusive education

Figure 2. Simple plot of interaction effects between country and gender on attitudes towards inclusive education

Figure 3. Simple plot on interaction effects between country and gender on perception about inclusive education

show the interaction between the country and gender of the participants, respectively. The simple slope in indicates a high-level interaction between country and gender and how participants perceived inclusive education. It also showed that male and female pre-service teachers from Nigeria had a more positive attitude towards inclusive education than those from South Africa. However, shows a lower level of interaction between the independent variables (country and gender) and the perceptions of the participants about inclusive education.

8. Discussion

Based on the recommendations of Al Abduljabber (Citation2006) and R. Dapudong (Citation2013) to engage in cross-national studies to provide further understanding of the theories and practices of inclusive education, this study employed the BST (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979, Citation2005) to provide an understanding of the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers across two African countries. Unlike previous studies (Baguisa & Ang-Manaig, Citation2019; Kamenopoulou et al., Citation2016; Pottas, Citation2005; C. R. Dapudong, Citation2014; Wanjiru, Citation2017) that actively probed the understanding and beliefs of in-service teachers about inclusive education, this study specifically investigated and established the relationship between gender, knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of inclusive education among pre-service teachers from Nigeria and South Africa.

The comparison of the knowledge of the male and female pre-service teachers from the two countries revealed no significant interaction between males and females vis-à-vis their countries. Although female pre-service teachers from Nigeria had slightly better knowledge of inclusive education, the overall results showed that the pre-service teachers from South Africa were more knowledgeable about inclusive education than the pre-service teachers from Nigeria. This suggests that teachers in South Africa are more likely to embrace inclusive education and meaningfully contribute to achieving the goals of inclusive education and social justice than their counterparts in Nigeria.

It should be noted that both the African countries examined in this study have cultural beliefs of being humane. In the Yoruba extraction in Nigeria, this is referred to as ‘Omoluabi’ and in South Africa it is referred to as ‘Ubuntu/Botho’. Truly, ‘humaneness’ is embedded in African societies and has been incorporated into educational philosophies and curricula (Department of Education, Citation2001; Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN), Citation2004). These concepts of Omoluabi and Ubuntu/Botho (Makhonza et al., Citation2019) encourage citizens to love, support, value, and care for persons with disabilities and are geared towards inclusion. However, the findings from this study that presented pre-service teachers from South Africa as being more knowledgeable about inclusive education may have been predicated on the dynamics of South Africa as a nation where people of different races/ethnicities (e.g., white, Indian, and black) live, go to school, and work in harmony—especially in the post-apartheid era.

In South Africa, the curriculum of ‘life orientation’ (Department of Education, Citation2001) in schools (grades R to 12) is predicated on the values of social justice, human rights, and inclusivity as a central part of the organisation, planning, and teaching at all South African schools. The foregoing may therefore have contributed to the knowledge of South African pre-service teachers about persons with disabilities. The findings of this study negate the findings of AlMahdi and Bukamal (Citation2019), Baguisa and Ang-Manaig (Citation2019), C. R. Dapudong (Citation2014), Pottas (Citation2005), and Wanjiru (Citation2017) who affirmed that teachers did not have adequate knowledge about inclusive education. A previous study in Kenya (Wanjiru, Citation2017) established that teachers had insufficient knowledge of inclusive education, and an earlier study of inclusive education in South Africa also revealed poor knowledge among South African teachers (Hay et al., Citation2001).

In line with the findings of Hay et al. (Citation2001), Mayat and Amosun (Citation2011) also reported that the academic staff of a South African university lacked awareness of how to transition students with disabilities into its civil engineering programme. Although Mayat and Amosun (Citation2011) study participants expressed their readiness to teach students with disabilities, they were concerned about how such students would cope with rigorous academic activities in the engineering faculty’s lecture rooms. The findings regarding the Nigerian pre-service teachers’ low levels of knowledge about inclusive education confirmed those of the study by Ajuwon (Citation2012), who noted that there was much to be done to improve teachers’ preparedness for inclusive teaching programs. At the time of the study by Ajuwon (Citation2012), the teachers undergoing training in Nigeria were found to have little knowledge of inclusive education. Unfortunately, the present study confirmed that pre-service teachers’ knowledge of inclusive education was still low in comparison to that of South African pre-service teachers.

There was a significant difference in the attitudes of the pre-service teachers towards inclusive education, based on the countries in which the study participants were located, with Nigeria achieving a higher score than South Africa. In this study, the pre-service teachers from Nigeria were better disposed of inclusive education than their South African counterparts. This was surprising, given the finding that the South African pre-service teachers had better knowledge of inclusive education, so it was expected that they would exhibit commensurate attitudes towards inclusive education. Yet, it was shown that the Nigerian pre-service teachers had better dispositions to inclusive education. The more positive attitudes of the Nigerian pre-service teachers may have been informed by the country’s legislation and educational policies (Srivastava et al., Citation2017), school factors (Deng & Holdsworth, Citation2007; Ngcobo & Muthukrishna, Citation2011), or personal experiences gathered in support of underprivileged individuals. In particular, those who were internally displaced or had sustained disabilities as a result of experiencing various communal clashes, insurgencies, and terrorism in Nigeria.

Earlier studies in Western China and Vietnam (Deng & Holdsworth, Citation2007; Villa et al., Citation2003) revealed differences in the attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education in the Asian region. A more positive attitude towards the inclusion of children with disabilities was found in Western China, and Deng and Holdsworth (Citation2007) attributed the result obtained to a concerted effort by special needs education teachers and the involvement of community leaders. Previous studies have shown the influence of positive attitudes towards the education of learners with disabilities (Abang, Citation2005; Avramidis et al., Citation2000; Haugh, Citation2003; Ozoji, Citation2005; C. R. Dapudong, Citation2014; Srivastava et al., Citation2017). The findings of the present study support those of C. R. Dapudong (Citation2014), who indicated that teachers from Thailand had a positive attitude towards inclusion in regular school programmes and participation in all school activities.

The present study paralleled Sharma et al.’s (Citation2006) study, where differences were also found in the attitudes of pre-service teachers towards inclusive education. Sharma et al.’s (Citation2006) cross-national study sampled pre-service teachers from Hong Kong, Singapore, Canada, and Australia. In these four developed countries, Sharma et al. (Citation2006) found that trainee educators from Canada had more positive attitudes towards inclusive education than those from Kong, Singapore, and Australia. In a follow-up study, Sharma et al. (Citation2012) noted that pre-service teachers from Singapore had a poorer attitude towards inclusive education than those from Australia.

Variations in the attitudes towards inclusive education by pre-service teachers from Botswana and Ghana were assessed by Kuyini and Mangope (Citation2011). In their study, Kuyini and Mangope (Citation2011) observed a more positive attitude towards inclusive education in pre-service teachers from Ghana than in those from Botswana. No significant differences were associated with gender differences between the two countries. In the current study, male pre-service teachers from Nigeria showed a more positive attitude towards inclusive education than their female counterparts, while in South Africa females had a better disposition towards inclusive education than their male counterparts. This finding with respect to South Africa agrees with the studies of Tamar (Citation2008) and Fakolade et al. (Citation2009), who reported a more positive attitude towards inclusive education by female teachers.

Similarly, the perceptions of inclusive education were significantly different between the two countries (Nigeria and South Africa). The study revealed that pre-service teachers from Nigeria had higher scores on how they perceived an inclusive education programme than those from South Africa. Correspondingly, a significant interaction existed between gender and the perception of inclusive education, and the female pre-service teachers from South Africa had a more positive perception of inclusive education than their Nigerian counterparts. This finding corroborated the findings of Cheng (Citation2011) and Peck et al. (Citation1992), who found positive perceptions of inclusive education among teachers.

In fact, Cheng (Citation2011), although expressing reservations about teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education because they were not competent to teach in inclusive classrooms, remarked that teachers with positive perceptions of inclusive education believed that inclusion was beneficial to learners with disabilities. Magumise and Sefotho (Citation2018) and N. M. Nel et al. (Citation2016), in their studies among teachers from two different Southern African countries, could not conclude on the ratings of their participants’ perceptions of inclusive education. The present study differs from the findings of Blackie (Citation2010) and Daane et al. (Citation2000), who stated that teachers had negative perceptions of the benefits and effectiveness of inclusive education in schools. Moreover, this study identified a variation in the perceptions of male and female pre-service teachers in both countries studied, while Rambo (Citation2012) found no significant difference between male and female teachers’ perceptions of inclusion.

9. Conclusion and recommendations

The current study provided evidence that there was a large discrepancy in the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers about inclusive education, especially among those who had been exposed to the teaching practice (Nigeria) or professional practice (South Africa) modules of their training. The study highlighted the influence of gender on the knowledge base, attitudes, and perceptions of third-year undergraduate students who participated in the study. Efforts must be made to ensure that all pre-service teachers have an equal understanding of, develop the same attitudes towards, and adopt the philosophy of inclusive education.

The findings of this study have implications for education in Africa. That is, the faculties of education in the various African universities need to intensify their efforts to scale up the content of their curricula in order to furnish trainee teachers with the knowledge of the intricacies of inclusive education and what is attainable in real inclusive classroom scenarios. While both Nigeria and South Africa have enacted policies aimed at strengthening their just and egalitarian societies and at ensuring that children with disabilities are not stereotyped based on the segregation of their educational facilities, the institutions of higher learning and training of would-be teachers should scale up their curricula. The content of the curricula should be reinforced with activities geared towards the adequate preparation of trainee teachers for the task of teaching learners with disabilities. Pre-service teachers must be guided in modelling the pedagogy needed for the successful implementation of inclusive education.

10. Limitations of the study

The limitations of this study include the involvement of just two regions of Africa (west: Nigeria; south: South Africa). In addition, only pre-service teachers who had partaken in the practical aspect of the teacher training—teaching practice in Nigeria and professional practice in South Africa—were involved in the study. Future studies should consider comparative cross-national studies to explore the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers from countries in all regions of Africa. Moreover, such studies should involve teacher trainees from the first year to the final year of study and other demographic variables (with or without gender) should be assessed using more refined research instruments.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Olufemi Timothy Adigun

Olufemi Timothy Adigun PhD is currently a Postdoctoral Research Fellow of the Department of Special Needs Education, University of Zululand, South Africa under the mentorship of Prof D. R. Nzima. Olufemi has a passion for deaf studies and inclusive educational processes and has published research articles on deaf-related issues. He is a member of the Association of Sign Language Interpreters in Nigeria (ASLIN), the Educational Sign Language Interpreters in Nigeria (ESLIAN), and the World Association of Sign Language Interpreters (WASLI).

References

- Abang, T. B. (2005). The exceptional child: Handbook of special education. Fab Anieh.

- Abosi, C., & Ozoji, E. (1990). A study of student-teachers attitudes towards the blind. Journal of Special Education and Rehabilitation, 2, 23–19.

- Adetoro, R. A. (2014). Inclusive education in Nigeria—A myth or reality? Creative Education, 5(20), 1777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.520198

- Adewumi, T. M., & Mosito, C. (2019). Experiences of teachers in implementing inclusion of learners with special education needs in selected fort beaufort district primary schools, South Africa. Cogent Education, 6(1), 1703446. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1703446

- Adigun, O. T., & Adedokun, A. P. (2013). Teaching basic sciences in the inclusive classroom. Journal of Special Education, 11(1), 55–64.

- Agbenyega, J. S., Deppeler, J., & Harvey, D. (2005). Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education in Africa Scale (ATIAS): An instrument to measure teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education for students with disabilities. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 5, 1–15. https://www.google.com/search?q=Attitudes+Towards+Inclusive+Education+in+Africa+Scale+(ATIAS)%3A+An+instrument+to+measure+teachers%27+attitudes+towards+inclusive+education+for+students+with+disabilities.&rlz=1C1CHBD_enZA899ZA899&oq=Attitudes+Towards+Inclusive+Education+in+Africa+Scale+(ATIAS)%3A+An+instrument+to+measure+teachers%27+attitudes+towards+inclusive+education+for+students+with+disabilities.&aqs=chrome..69i57.932j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#

- Agunloye, O. O., Pollingue, A. B., Davou, P., & Osagie, R. (2011). Policy and practice of special education: Lessons and implications for education administration from two countries. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(9), 90–95. http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_1_No_10_August_2011/13.pdf

- Ajuwon, P. M. (2008). Inclusive education for students with disabilities in Nigeria: Benefits challenges and policy implications. International Journal of Special Education, 23(3), 11–16. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ833673.pdf

- Ajuwon, P. M. (2012). Making inclusive education work in Nigeria: Evaluation of special educators’ attitudes. Disability Studies Quarterly, 32(2), Available at https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3198.

- Al Abduljabber, A. (2006). Administrators’ and teachers’ perceptions of inclusive schooling in Thai. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/theses

- AlMahdi, O., & Bukamal, H. (2019). Pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education during their studies in bahrain teachers college. SAGE Open, 9(3), 2158244019865772. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019865772

- Anderson, J., Boyle, C., & Deppeler, J. (2014). The ecology of inclusive education: Reconceptualising bronfenbrenner. In Zhang H, Chan PWK., Boyle C. (Eds.), Equality in education pp.(23–34). Brill Sense..

- Armstrong, A., Armstrong, D., & Spandagou, I. (2010). Inclusive education: International policy & practice. London.

- Aurah, C. M., & McConnell, T. J. (2014). Comparative study on pre-service science teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs of teaching in Kenya and the United States of America; USA. American Journal of Educational Research, 2(4), 233–239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12691/education-2-4-9.

- Avoke, M. (2002). Models of disability in the labelling and attitudinal discourse in Ghana. Disability & Society, 17(7), 769–777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759022000039064

- Avramidis, E., Bayliss, P., & Burden, R. (2000). A survey into mainstream teachers’ attitudes towards the inclusion of children with special educational needs in the ordinary school in one local education authority. Educational Psychology, 20(2), 191–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/713663717

- Avramidis, E., & Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers’ attitudes towards integration/inclusion: A review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 17(2), 129–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250210129056

- Baguisa, L. R., & Ang-Manaig, K. (2019). Knowledge, skills and attitudes of teachers on inclusive education and academic performance of children with special needs. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 4(3), 1409–1425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2019.43.14091425

- Bartley, V. (2014). Educators’ attitudes towards gifted students and their education in a regional Queensland school. TalentEd, 28(1/2), 24–31. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/ https://doi.org/10.3316/INFORMIT.147676113827100

- Blackie, C. (2010). The perceptions of educators towards inclusive education in a sample of government primary schools. Masters dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. http://hdl.handle.net/10539/11361

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard university press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage.

- Cheng, K. (2011). Shanghai: How a big city in a developing country leaped to the head of the class. In M. S. Tucker (Ed.), Surpassing shanghai: An agenda of American education built on the world’s leading systems (pp. 21–48). Harvard Education Press.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Daane, C. J., Beirne-Smith, M., & Latham, D. (2000). Administrators’ and teachers’ perceptions of the collaborative efforts of inclusion in the elementary grades. Education, 121(2), 331–338. https://go.gale.com/ps/anonymous?p=AONE&sw=w&issn=00131172&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA70450751&sid=googleScholar&linkaccess=fulltext

- Dapudong, C. R. (2014). Teachers knowledge and attitude towards inclusive education: Basis for an enhanced professional development program. International Journal of Learning & Development, 4(4), 1–24. www.macrothink.org/journal/index.php/ijld/article/download/6116/5169.

- Dapudong, R. (2013). Knowledge and attitude towards inclusive education of children with learning disabilities: The case of Thai primary school teachers. Academic Research International, 4(4), 496–512. http://www.iccwtnispcanarc.org/upload/pdf/4567697528Inclusive%20education%20of%20children%20with%20learning%20disability.pdf

- Deng, M., & Holdsworth, J. (2007). From unconscious to conscious inclusion: Meeting special education needs in west China. Disability & Society, 22(5), 507–522. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590701427644

- Department of Education. (2001). Education white paper 6: special needs education building an inclusive education and training system. ELSEN directorate. In Department of education,Government Printer.

- Department of Education (DoE). (2005). Framework and management plan for the first phase of implementation of inclusive education. Government Printer.

- Donohue, D., & Bornman, J. (2014). The challenges of realising inclusive education in South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 34(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15700/201412071114

- Eskay, M. (2009). Special education in Nigeria. Lambert Academic Publishing.

- Eskay, M., Onu, V. C., Igbo, J. N., Obiyo, N., & Ugwuanyi, L. (2012). Disability within the African culture. US-China Education Review, 2(4), 473–484. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED533575.pdf

- Fakolade, O. A., Adeniyi, S. O., & Tella, A. (2009). Attitude of teachers towards the inclusion of special needs children in general education classroom: the case of teachers in some selected schools in Nigeria. International Electronic Journal of elementary education,1(3), 155–169.

- Fakolade, O. A., Adeniyi, S. O., & Tella, A. (2017). Attitude of teachers towards the inclusion of special needs children in general education classroom: The case of teachers in some selected schools in Nigeria. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 1(3), 155–169.

- Federal Ministry of Education. (2015). National policy on special needs education in Nigeria. Abuja. Nigeria: Federal Government of Nigeria. https://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/planipolis/files/ressources/nigeria_special_needs_policy.pdf

- Federal Republic of Nigeria (FRN). (2004). National policy of education. NERDC.

- Garuba, A. (2003). Inclusive education in the 21st century: Challenges and opportunities for Nigeria. Asia Pacific Disability Rehabilitation Journal, 14(2), 191–200.

- Geldenhuys, J. L., & Wevers, N. E. J. (2013). Ecological aspects influencing the implementation of inclusive education in mainstream primary schools in the eastern cape, South Africa. South African Journal of Education, 33(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15700/201503070804

- Grice, J. W., & Iwasaki, M. (2007). A truly multivariate approach to MANOVA. Applied Multivariate Research, 12(3), 199–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22329/amr.v12i3.660

- Hamid, A. E., Alasmari, A., & Eldood, E. Y. (2015). Attitude of pre-service educators toward including children with special needs in general classes: Case study of education faculty–University of Jazan. KSA. International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology, 1(3), 140–145. https://www.academia.edu/15306474/Attitude_of_Pre_Service_Educators_toward_Including_Children_with_Special_Needs_in_General_Classes_Case_study_of_Education_Faculty_University_of_Jazan_K_S_A

- Haugh, P. (2003). Qualifying teachers for the school for all. In T. Booth, K. Nes, & M. Stromstad (Eds.), Developing inclusive education (pp. 97–115). Routledge.

- Hay, J. (2003). Implementation of the inclusive education paradigm shift in South African education support services. South African Journal of Education, 23(2), 135–138. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC31930

- Hay, J. F., Smit, J., & Paulsen, M. (2001). Teacher preparedness for inclusive education. South African Journal of Education, 21(4), 213–218. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC31842

- Huberty, C. J., & Petoskey, M. D. (2000). Multivariate analysis of variance and covariance. In Tinsley, Howard EA, Steven D. Brown, (Eds.), handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling (pp. 183–208). Academic Press..

- Jelagat, K. J., & Ondigi, S. R. (2017). Influence of socio-cultural factors on inclusive education among students & teachers in nairobi integrated educational programme, Kenya. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education, 7(1),PP 49–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.9790/7388-0701024955

- Kamenopoulou, L., Buli-Holmberg, J., & Siska, J. (2016). An exploration of student teachers’ perspectives at the start of a post-graduate master’s programme on inclusive and special education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(7), 743–755. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1111445

- Kuyini, A. B., & Mangope, B. (2011). Student teachers’ attitudes and concerns about inclusive education in ghana and botswana. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 7(1), 20–37. https://go.gale.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA261951855&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=17102146&p=AONE&sw=w

- Landasan, S. (2016). Extent of implementation of inclusive Education. Unpublished Masters Thesis, Laguna Polytechnic State University, Los Baños, Philippines. https://doi.org/https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2019.43.14091425

- Magumise, J., & Sefotho, M. M. (2018). Parent and teacher perceptions of inclusive education in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 34(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1468497

- Maher, M. (2009). Information and advocacy: Forgotten components in the strategies for achieving inclusive education in South Africa? Africa Education Review, 6(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/18146620902857251

- Makhonza, L. O., Lawrence, K. C., & Nkoane, M. M. (2019). Polygonal ubuntu/botho as a superlative value to embrace orphans and vulnerable children in schools. Gender and Behaviour, 17(3), 13522–13530. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-19745b196c

- Mayat, N., & Amosun, S. L. (2011). Perceptions of academic staff towards accommodating students with disabilities in a civil engineering undergraduate program in a University in South Africa. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 24(1), 53–59. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ941732.pdf

- Mphongoshe, S. J., Mabunda, N. O., Klu, E. K., Tugli, A. K., & Matshidze, P. (2015). Stakeholders’ perception and experience of inclusive education: A case of a further education and training college in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Sciences, 10(1), 66–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09751122.2015.11890341

- Murphy, D. M. (1996). Implications of inclusion for general and special education. The Elementary School Journal, 96(5), 469–493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/461840

- Nations, U. (2007). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Author.

- Nations, U. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Division for Sustainable Development Goals: New York, NY, USA . Available on https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld [Accessed on 21/October/2020]

- Nel, N., Müller, H., Hugo, A., Helldin, R., Bäckmann, Ö., Dwyer, H., & Skarlind, A. (2011). A comparative perspective on teacher attitude-constructs that impact on inclusive education in South Africa and Sweden. South African Journal of Education, 31(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v31n1a414

- Nel, N. M., Tlale, L. D. N., Engelbrecht, P., & Nel, M. Teachers’ perceptions of education support structures in the implementation of inclusive education in South Africa. (2016). KOERS — Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, 81(3), 17–30. Available at:. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19108/KOERS.81.3.2249

- Ngcobo, J., & Muthukrishna, N. (2011). The geographies of inclusion of students with disabilities in an ordinary school. South African Journal of Education, 31(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v31n3a541

- Nketsia, W., & Saloviita, T. (2013). Pre-service teachers’ views on inclusive education in Ghana. Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(4), 429–441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2013.797291

- Oluremi, F. D. (2015). Attitude of teachers to students with special needs in mainstreamed public secondary schools in Southwestern Nigeria: The need for a change. European Scientific Journal, 11(10), 194–209. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/236407134.pdf

- Omede, A. A. (2016). Policy framework for inclusive education in Nigeria: Issues and challenges. Public Policy and Administration Research, 6(5), 33–38. https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/PPAR/article/view/30695/31522

- Opoku, M. P., Nketsia, W., Alzyoudi, M., Dogbe, J. A., & Agyei-Okyere, E. (2020). Twin-track approach to teacher training in Ghana: Exploring the moderation effect of demographic variables on pre-service teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Educational Psychology. 41(3). Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2020.1724888

- Osisanya, A., Oyewumi, A. M., & Adigun, O. T. (2015). Perception of parents of children with communication difficulties about inclusive education in ibadan metropolis. African Journal of Educational Research, 19(1), 21–32. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349255573_Perception_of_parents_of_children_with_communication_difficulties_about_inclusive_education_in_Ibadan_metropolis

- Ozoji, E. D. (2005). Demystifying inclusive education for special needs children in Nigeria’s primary schools. Journal of Childhood and Primary Education, 1(1), 13–14.

- Peck, C., Carlson, P., & Helmstetter, E. (1992). Parent and teacher perceptions of outcomes for typically developing children enrolled in integrated early childhood programs: A statewide survey. Journal of Early Intervention, 16(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/105381519201600105

- Pillay, J., & Di Terlizzi, M. (2009). A case study of a learner’s transition from mainstream schooling to a school for learners with special educational needs (LSEN): Lessons for mainstream education. South African Journal of Education, 29(4), 491–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n4a293

- Pottas, L. (2005). Inclusive education in South Africa: The teacher of the child with a hearing loss. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_nlinks&ref=3592486&pid=S2225-4765201700010000600031&lng=en

- Rambo, C. (2012). Employee related factors influencing their perception on quality management system at nairobi city water and sewage company. University of Nairobi. Retrieved March, 2019 from http://www.ems.uonbi.ac.ke/Node/1403.

- Republic of South Africa. (1996). The constitution act no. 108 of 1996. Government Printer, Pretoria.

- Ross-Hill, R. (2009). Teacher attitude towards inclusion practices and special needs students. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 9(3), 188–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2009.01135.x

- Sedgwick, P. (2013). Convenience sampling. BMJ, 347(oct25 2), f6304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6304

- Sharma, U., Forlin, C., Loreman, T., & Earle, C. (2006). Pre-service teachers’ attitudes, concerns and sentiments about inclusive education: An international comparison of the novice pre-service teachers. International Journal of Special Education, 21(2), 80–93.

- Sharma, U., Loreman, T., & Forlin, C. (2012). Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. Journal of research in special educational needs, 12(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01200.x

- Singal, N. (2006). An ecosystemic approach for understanding inclusive education: An Indian case study. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21(3), 239–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173413

- Srivastava, M., De Boer, A. A., & Pijl, S. J. (2017). Preparing for the inclusive classroom: Changing teachers’ attitudes and knowledge. Teacher Development, 21(4), 561–579. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2017.1279681

- Tamar, T. (2008). Regular teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion of students with special needs into ordinary schools in Tbilisi. Master thesis. University of Oslo. Permanent link: http://urn.nb.no/URN:NBN:no-19775.

- Timothy, A. E., Obiekezie, E. O., Chukwurah, M., & Odigwe, F. C. (2014). An assessment of english language teachers’ knowledge, attitude to, and practice of inclusive education in secondary schools in Calabar, Nigeria. Journal of Education and Practice, 5(21), 33–39. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3483863

- UNESCO. (1994). The salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. UNESCO. http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF

- Villa, R. A., Van Le Tac, P. M., Muc, S., Ryan, N. T. M., Weill Thuy, C., & Thousand, J. S. (2003). Inclusion in vietnam: More than a decade of implementation. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 28(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.28.1.23

- Walton, E. (2018). Decolonising (through) inclusive education? Educational Research for Social Change, 7 31‐45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17159/2221‐4070/2018/v7i0a3

- Wanjiru, N. J. (2017). Teachers’ knowledge on the implementation of inclusive education in early childhood centers in Mwea East Sub-County, Kirinyaga County, Kenya. Unpublished Masters Dissertation, Kenyatta University, Kenya.