Abstract

Discipline in the higher education classroom is a widely debated phenomenon, especially since it is defined interchangeably with classroom management, which is pertinent to schooling in non-adult institutions. This research aimed to apply the principles of discipline in a higher education context to study the impact of attitude and behaviour on learning conditions while embracing partnered approaches with adult learners to maintain its relevance. The consequences of misbehaviour under the key concepts of disruption and safety in the classroom were examined. This study was conducted within a healthcare professional programme in the UK where theoretical learning is partnered with practical settings to inform evidence-based practice. Within the practical context, the frequency of claims highlighting the impact of undisciplined behaviour persists, while the educational approaches of partners to address this are vague. Thus, the overarching aim of this study was to identify whether discipline in the classroom can act as a behavioural strategy to influence attributes outside the classroom. Using a qualitative methodology, the study compares the perceptions of students at varying levels under a critical realist theoretical framework. The data were collected by means of an online open-ended questionnaire as the first step of action (participatory) research, intended to be a platform to guide reflection, action, and further research. Participant responses clearly associate the action of discipline to an intrinsic value and allow the prediction of its influence on behaviour outside the context of the classroom. The findings further substantiate the intrinsic approach of discipline in predisposing attitudes, which are evidenced as plausible influences on the safety felt within the classroom.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Professional attributes are not skills taught on a programme, they are developed through incremental processes intertwined within teaching and learning over sustained durations. “Discipline in the Higher Education Classroom”, is a study conducted within the context of an adult learning environment to analyse the impact of behaviour on safety, performance and goals, which aligns to wider noted controversies in working cultures. Through the application of socio-psychological theories, the study introduces a means of touching the intrinsic compartments of adults to allow a change in attitudes and consequent behaviours. Behaviour which apprehends morals and values are not only valuable in improving learner engagement, work performance and healthcare quality but also influences the conditions within society; in our daily interactions with others. This study is conducted to bring forward a strategic means of transforming adult attributes to reflect professionalism and provide an educated and controlled outlook beyond the shift in skills and knowledge.

1. Introduction

This paper discusses a pedagogical piece of research conducted within an undergraduate healthcare professional programme (Operating Department Practice (ODP)) in a higher education institution in the UK. The research aimed to explore students’ perception of discipline in the classroom and identify the extent to which discipline in the classroom influences behaviour. It also aimed to establish whether discipline can contribute to a psychologically safe environment and whether this and/or discipline itself impacts on learning effectiveness. The existing literature was reviewed to obtain a theoretical understanding of similar contextual studies and determine the relationship between existing findings and those of this research. Research in this area was also appraised to generate knowledge on research method tools regarding the identified limitations of similar studies. This is a qualitative piece of research, under the ontological framework of critical realism, which intends to draw causal patterns from the reality of lived experiences through a systematic thematic analysis. It is the first stage in action (participatory) research, which is intended as a foundation for recognizing issues in current practice, derive solutions, and improve subsequent research. The research received ethical approval as ratified by the institutional research ethics committee.

1.1. Literature review

Discipline originates from the Latin word disciplina meaning “instruction given, teaching, learning, knowledge” and from the Latin discipulus meaning “pupil” (Online Etymology Dictionary, Citation2020, p. 1). Although its definition varies depending on the context, in the abstract form discipline is often described as “the practice of making people obey rules or standards of behaviour and punishing them when they do not” (Collins Dictionary, Citation2020, p. 1). This perspective of discipline has roots in the theories of Skinner (psychologist/behaviourist) (1954 as cited in Ervin et al., Citation2001), that is, of operant conditioning, which is derived from the idea that behaviour can be modified by using reinforcement or punishment. Skinner’s (1954) theory has since been critiqued widely due to its contextual influence, which lacks the functionality of embedding intrinsic motivational values that would sustain the disciplined behaviour out of its context (Kohn, Citation1993). Nonetheless, Skinner’s theory, although liberally, is still applied in remote educational contexts to create an environment of order that is cohesive to learning. Thus, with regards to the principles of classroom management, Doyle (Citation1986) suggested organizing and controlling learners in a learning environment to create and maintain an effective learning experience. Although Doyle (Citation1986) acknowledged the part behaviour plays in this, the rules applied are extrinsic in nature and operated solely for the purposes of enhancing learning. On the other hand, Bossone (Citation1964) argued that discipline is a form of training social conduct, which influences the kind of thinking needed to mould lifelong attributes (Sprick, Citation2013). Although Skinner’s (1954) theory on operant conditioning has been applied in multiple social contexts including the law (Watson, 1920 as cited in Melechi, Citation2020), predicting transferability between contexts requires a transition to intrinsically inclined attitudes. While attitude-behaviour consistency is contingent on broader factors, research suggests that affective attitudes are powerful predictors of behaviour (Lawton et al., Citation2009). Subsequently, Horner (Citation2003) suggested that morals are deeply held intrinsic values that are often an unconscious and immeasurable phenomenon yet underpin present and future. “Values are abstract goals which serve as the guiding principles in people’s lives; which as opposed to attitudes, they are more stable in acting as codes of conduct” (Schwartz, Citation1992, p. 25; Schwartz et al., Citation2012). Watson (Citation1913) argued that although behaviourists approach psychology as purely experimental and measurable as the study of consciousness, its theoretical goal is to predict and control behaviour without recourse to conscious behaviour. Underpinned by these theories, the present study aimed to analyse the meaning students attach to discipline to understand how significant/non-significant the relationship between discipline and intrinsic moral values is, which could be used to predict the transferability of related behaviour outside the classroom. Simultaneously, the contextualization of the findings will determine the causes of attitudes and subsequent behaviour. Proponents of the functional approach in social psychology agree and stress that by knowing what constitutes the basis of an attitude, it is easier to change it (Herek, Citation1987; Katz, Citation1960). They add that changing attitudes is one way of changing human behaviour. Furthermore, the consequences of misbehaviour on learning determine if discipline can be used to enhance this and whether the findings are transferable to wider contexts that work towards cultures of learning whereby peers can learn from mistakes and continuously improve the quality of their performance.

Discovering the impact of discipline/lack of discipline in the classroom provides a basis for how behaviour impacts on goals within this context. The absence of value-based attributes has detrimental effects on the safety and quality of patient care (Cameron, Citation2013); however, in the context of the classroom, absence of these attributes could create conditions whereby learning; the ultimate objective, may be impacted upon thereby preventing interactive learning pedagogies from being fully effective. Since the concepts of “classroom discipline” and “classroom management” are often used interchangeably (Bellon et al., Citation1992), the literature reviewed applies the principles of classroom management to discipline. Nonetheless, both concepts have a similar purpose within the classroom regarding safe learning conditions. Way (Citation2016) made a direct link between discipline and safety and claimed that discipline that allows rules and regulations produces safe, orderly and generally conducive learning environments. Classrooms where students feel safe to take risks in undertaking uncertain and challenging tasks, acquire new knowledge and know that they are valued members of a community are classrooms where learning is optimized (Bransford et al., Citation1999; Ioakimidis & Myloni, Citation2010; Wang et al., 1994 as cited in Norris, Citation2003). Integrated learning is a key focus in healthcare programmes, especially since learning is partnered with practical experiences. Consequently, the need for safety in the classroom has been suggested as a prerequisite for meaningful self-reflection, self-discovery, and student engagement (Garran & Rasmussen, Citation2014). These pedagogical goals necessitate a classroom where students feel safe to experience increasing levels of vulnerability that accompany self-discovery and self-disclosure (Garran & Rasmussen, Citation2014). Regardless of the consensus portrayed in the literature, which argues the need to establish a safe environment, the use of discipline as a means of achieving this has yet to be fully established. Thus far research has applied the principles of classroom management with an emphasis on control and order, whereas the fundamental concern of the research in the present study is discipline concerned with behavioural influence. Hence, this research aimed to identify the extent to which behaviours cause reluctance in engaging with a variety of learning strategies. This corresponds to the practical relevance in the healthcare setting whereby reluctance to raise concerns or questions and challenge approaches have detrimental effects on patient care (Edmondson et al., Citation2016).

The call for transferable skills to develop socially receptive behaviour has been on the agenda of many across multiple disciplines (Barnett, Citation2009; Parker, Citation2003; Peach, Citation2010). The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills [DBIS] (Citation2009) reiterated that (higher education institutions) need to develop high-level skill training that develops economic strength while at the same time creating a socially receptive and civilized society. Katz et al. (Citation2019) in their recent study of the peri-operative field, concluded that incivility is a significant barrier to communication, increasing the risks of avoidable errors. The social culture of healthcare has been an increasing concern since the public enquiry in healthcare conduct outlined in the Francis Report (Cameron, Citation2013), which clearly concluded that immoral behaviour has an impact on patient lives. Professional practice in healthcare is unique; there is an expectation that one should be professional within a complex team of hierarchal differences while embracing another’s suffering with compassion and empathy (Stickley & Freshwater, Citation2018). Katz et al. (Citation2019) stated that an atmosphere of intimidation endangers sound decision-making and creates interpersonal conflict that impacts on individual health and well-being. The call for transformation at the root of healthcare education was identified over a decade ago with a gradual move of registered healthcare professionals to graduate (degree-level) outcomes, reflecting the ability to apply critical reasoning and balance alternatives (Council of Deans of Health, Citation2013). The requirement for students to demonstrate value-based attributes has since been crystallized and standardized across healthcare and medical programmes by their respective governing bodies in standards of conduct (General Medical Council [GMC], Citation2021, Health and Care Professions Council [HCPC], Citation2016, and Nursing & Midwifery Council [NMC], Citation2018). Ultimately these standards mandate teaching, learning, and assessment of these attributes as a prerequisite to professional registration. Despite clear statements that attach attributes to a specific task, such attributes are seldom assessed within higher education settings. Challenges fluctuate between the ability to assess attributes by using modular designs and learning by means of outcome-based assessments. Such structures limit the development of skills that refine over a longer interconnected process, risking consigning behavioural conditioning to practice partners, where competencies are achieved within a practical setting and over wider time frames. In theory, bearing in mind that the formation of attributes is an ongoing active process, practice partners are correctly positioned to assess them. However, this is based on the principle that behaviour is learned within a practical setting through observation and experience only, which risks emphasis from evidence-based learning to learning cultural behavioural norms. This was the issue highlighted in the Francis Report (Cameron, Citation2013) and further emphasized by Sir George Berwick (Citation2013) in his political speech where he reiterated the need to shift from cultural norms to a culture of learning. Garnick (Citation2005) agreed and suggested that practice is the way of doing things; it needs to be rationalized with an underpinning theory to make sense of experiences and allow the anticipation of consequences, which in turn supports effective decisions. Educational strategies to train conduct allow the theoretical reasoning of behaviour acting as the cognitive component of attitude-behaviour consistency (Haddock & Maio, Citation2004).

1.2. Rationale and context

The rationale for undertaking this study relates to the author’s suggestion that higher education is transformative in nature. Since professional programmes are aimed at developing professional practitioners, education should go beyond providing and assessing academic standards by developing individuals who have lifelong skills and attributes that are not only fit for practice but also support sustainable professional stability. To consider the use of discipline in the classroom as a preliminary step towards this goal, consideration from a higher education context is required whereby teaching transitions to facilitation of adult learning. The complexity is the emphasis on student-led learning, that is, adopting partnered approaches in learning strategies, which introduces ambiguity and differences in opinion regarding control and responsibility. There are varied views on whether discipline in a higher education classroom is necessary and, to some degree, appropriate. Using discipline to create a controlled environment may result in disparate perspectives than if discipline is utilized as a behavioural conditioning strategy. In light of the differing views associated with the diversity in age groups of students enrolled in professional programmes, it is vital to understand how students perceive the use of discipline in the classroom and to what extent its use or absence impacts on their learning. Additionally, to strategically apply discipline in the classroom requires a well-informed plan that adult learners are happy to adopt. This research aims to explore the perspectives of adult learners to devise a plan using a partnered and inclusive approach.

2. Data and methods

2.1. Application to theoretical framework and research design

This research is based on qualitative methodology since it seeks to explore perceptions formed through observation and experience in the social context of the classroom. Merriam and Tisdell (Citation2015) suggested that perceptions are subject to interpretation and will differ between individuals in the same setting. They explained that reality consists of social, cultural, and experiential factors that act as the reality of their interpretation. Unlike quantitative research, which aims to analyse the what, where, and when, this qualitative framework aims to explore the why and how behind human interpretation and the reasons that govern these (Merriam & Tisdell, Citation2015). As such, this research is based on a critical realist ontology, which Given (Citation2008) described as a postpositivist approach sitting between positivism and relativism/constructivism. To clarify, realism is a positivist approach that believes the participant’s version of reality; it adapts an objective perspective disregarding the social context and other influences that cause that interpretation (Cohen et al., Citation2007/Citation2018). From a relativism perspective, the participant’s interpretation of reality is moved aside by the meaning drawn by the researcher, under the rationale that the researcher cannot demonstrate the psychological and social reality that sits behind the words (Terry et al., Citation2017). However, critical realism embraces the reality in perception and allows latent flexibility by applying causal influences that impact on the reality experienced (Given, Citation2008). The researcher accepts the participant’s interpretation as real yet they interpret it in the social context of the classroom and actively participate in drawing patterns using the characteristics studied by employing existing theory and the knowledge they have gathered in their work as an educator towards a shared clinical profession (ODP). Given (Citation2008) agreed that critical realism is well suited to research that seeks to explain outcomes and patterns and the underlying complex phenomena.

The ontology of critical realism further supports the action/participatory design of this research since it is focused on seeking causal influences on the experience expressed to arrive to solutions. Mertler (Citation2017) described action research as a systematic enquiry conducted by teachers with a vested interest in the teaching and learning process or environment to gather information about how their organization operates, how they teach, and how their students learn. He added that the process allows them to better understand their students and improve their quality and effectiveness. This study relies on active participation to derive knowledge, which is unknown to the researcher challenging the traditional notions of academic expert and participant collaboration, allowing research participants a full or shared input in the process based on a mutual interest (Coleman, Citation2015). The invitation extended to ODP students reflects these statements since students were collectively invited to participate in a study that would help to improve the ODP programme for “our” clinical profession.

2.2. Limitations

The research data were collected from students who were familiar with the researcher in the capacity of lecturer on their programme of study. The fluidity in the interpretation of “discipline” may have influenced the researcher’s way of applying behaviour to healthcare values. Although students had interactions with multiple lecturers, the researcher’s identity was not hidden when encouraging students to participate; thus, students may have recalled this association. On the other hand, this strengthens the claim of the effectiveness in developing intrinsic meaning regarding behaviour, thereby strengthening the claim of addressing practice using theoretical applications. Similar research must consider the researcher’s reflexivity on the findings; further research within a programme of no active involvement should also be considered. Additionally, the questionnaire design limited the opportunity to ask further questions related to safety in the classroom; such valuable answers could have helped to further understand the causes of attitudes and behaviour in the classroom. Future research may wish to employ semi-structured interviews that allow the retrieval of deeper understanding.

2.3. Methodological integrity

The selection of the data collection method/tool like the methodology is an inductive process that relies on the notion of fitness for purpose (Barbour, Citation2018). This notion is of key importance in the selection of the data collection method employed in this research, especially with its action research design implying an inclusive and collaborative approach (Coleman, Citation2015). Although critical realism is not associated with a specified method, Given (Citation2008) reiterated that the data collected must be free from the researcher’s preconceptions or ideology, thus indicating some level of objectivity. Furthermore, regarding educational research, Saxena et al. (Citation2015) argued that one of the most significant ethical controversies concerns the will to participate, which should be based on the ethical grounds of voluntary participation. Students are in vulnerable positions; they may resort to participation for fear of being disadvantaged by their lecturer who is also acting as the researcher (as in this study); this questions the relationship between authority, power, and morality (Saxena et al., Citation2015). Ramrathan et al. (Citation2017) suggested that ethics are not only a set of rules that need to be accounted for to construct research; they also act as a “moral duty” for rational individuals to act in ways that show respect for others. The aim of research should be to establish the truth surrounding the phenomena, which is a key ethical domain designed to ensure integrity in research (Ramrathan et al., Citation2017). Students involved in the research aim to answer proportionately but may withhold information, which may question the integrity of the findings. Considering the limitations in the context of this research and the participatory emphasis of the action research design, data were collected using electronic questionnaires/surveys to assure anonymity and true voluntary participation, while allowing inclusive and wider participation. This may trigger a superficial response (Xerri, Citation2017) that is controversial to any deep meaningful explanations sought under the critical realist framework (Given, Citation2008). However, since this research acts as the first stage in action research, further research is needed to reinforce its claim(s).

Qualitative data are renowned for their richness, which allows expressions, behaviour, and colloquial demeanour to be captured through forms of communication not fully expressed in the written words (Boynton & Greenhalgh, Citation2004). Methodologies that allow the questions to be phrased differently to generate better understanding favours individuals who struggle to understand and express themselves through the written word. Boynton and Greenhalgh (Citation2004) suggested that research participants must give meaningful answers; this may require professional interviewing techniques to include participants with physical, mental, social, and linguistic impairments. This issue could have been addressed using focus groups which have a key role in social science research because of the ability of keeping a social distance while developing a suggested discussion among the group to understand the meaning and interpretations applied to the research (Liamputtong, Citation2011). Focus groups are also useful to understand causes and solutions (Liamputtong, Citation2011), which correspond to critical realism and the action research design. However, an institutional context poses a risk of individuals being reluctant to express opinions or discuss personal experiences in front of peers; this results in dominant individuals thwarting full participation (Liamputtong, Citation2011; Stalmeijer et al., Citation2014). Controversial topics may also affect how the discussion is handled, adding to the difficulty of managing group dynamics (Stalmeijer et al., Citation2014). Although one-to-one unstructured interviews address concerns of question clarity and group dynamics and indeed garner richer and deeper data (Allen, Citation2017), they also bring about ethical concerns of power difference applied to the context while limiting wider participation due to time constraints.

2.4. Population and sampling techniques

Wide and inclusive participation is a vital component of this study due to the principles of action research suggesting a possibility of change, which not only determines its success and sustainability through the participants included in the study, but also reduces resistance and preserves moral duty (Yahaya, Citation2020). The study population consisted of ODP students who were training as highly skilled allied health professionals who specialize in the perioperative field and have progressively widened practice in emergency and critical areas because of their unique skill set in highly stressful/fast-paced areas. As part of the (ODP) programme, 264 students from 2 sites at the same university were invited to participate in this research; 51 students agreed to participate. All participants’ data were analysed; sampling techniques were not used. Since a vital analytical part of this research is to examine the coherence in findings between the students’ years of study and how discipline is perceived under the critical realist framework, a reminder encouraging participation from year 1 students was sent out to be in close equilibrium with comparable data.

2.5. Data collection tool

The JISC online survey tool (https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/) was used to create and distribute the open-ended questionnaire. JISC was designed specifically for academic research with GDPR compliance certified to the ISO 27001 standard, thus assuring data security. Access to the data for this research was limited to the researcher and research supervisor. As per the BERA guidelines (British Educational Research Association [BERA], Citation2011), participants were provided with an information sheet that clarified the purpose, future use, and accessibility of this research data. Anonymity and possible loss through electronic error were also addressed to optimize full informed consent. When the research was submitted by the participant, this acted as confirmation of informed consent; this was also stated on the information sheet.

2.6. Procedure for administering the instrument and gathering the data

An invitation to participate in the research was sent electronically via the student Blackboard platform by means of an announcement on each programme area, reaching each student with an individual email. The purpose of the research was highlighted as the perceptions of ODP students on discipline in the classroom and if it impacts on their learning experience. This is only a partial purpose of this study; communication detailing the link to intrinsic/extrinsic motivation sought in defining “discipline” may have hindered the answers provided. The survey also consisted of a participant information sheet designed to answer questions regarding security, anonymity, accessibility, and clarity on one’s right to withdraw. The nature of the research and the number of questions were also articulated to provide a realistic estimation of the time required to complete the questionnaire. Participants were given three months (without personal encouragement) before a reminder was sent out using the same procedure, providing a final opportunity to participate and giving two weeks before the survey closed.

2.7. Measures

The design of the questionnaire and the list of questions were inspired by the words of Al Baghal (Citation2017) who stated that the structure of a questionnaire is vital since responders undergo cognitive processes while taking a survey. He stated four key items when designing a survey: how questions should be worded; using different types of questions; how questions should be ordered; and the visual design of the questionnaire. Inspired by this advice, the wording of the questions was formulated to match the student vocabulary; questions were straightforward and only one issue per question was allowed (Newby, as cited in Xerri, Citation2017). Xerri (Citation2017) suggested that the wording of questions is particularly vital when addressing non-factual matters that consist of student attitudes, beliefs, and practices. The wording of the questionnaire was tested by five students who were selected to identify any errors in the interpretation of the questions, thus minimizing ambiguity. Cohen et al. (Citation2007, p. 341) recommended piloting questionnaires to “increase the reliability, validity and practicability of the questionnaire”. The questionnaire was also piloted with four lecturers involved in the programme to ensure that the questions were not worded in ways that prompted answers causing offence, loss of reputation, or loss of anonymity for the lecturers on the programme. Boynton and Greenhalgh (Citation2004) agreed with this method and they pointed out that a study is unethical if it causes undue offence or trauma and breaches confidentiality.

2.8. Data analysis

Data were analysed through thematic analysis within a critical realist framework. Thematic analysis is a commonly used method to analyse social sciences data and is used to identify themes in qualitative data using a sequential process (Terry et al., Citation2017). Thematic analysis is generally a flexible process that is typically applied to experiential designs, regardless of the theoretical stance (Mills et al., Citation2010; Terry et al., Citation2017). However, as suggested by Roberts et al. (Citation2019), the theoretical stance allows data to be approached at appropriate levels and offers clarity in how the themes are arrived at, thus assuring rigour in analysis. Although a confirmed approach for the ontology of critical realism has not been exemplified, Terry et al. (Citation2017) noted that an inductive approach at a semantic level is appropriate for experiential designs and referred to a deductive approach at a latent level for critical frameworks. The data have been approached through a combined inductive and deductive approach and examined at both the semantic and latent levels. The appropriateness of this approach meets the criteria used by Roberts et al. (Citation2019) in their research carried out under a critical realist ontology. Although the codes were derived from participant responses (bottom up), the questions were formatted to prompt responses related to the predicted themes and were thus deductive in nature. Ultimately, to derive causal patterns under a critical realist framework relies on a back and forth approach to the initial hypothesis, while examining the data at latent levels (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Given, Citation2008). Latent levels of examination have also been applied due to the researcher’s position within the programme of research. Terry et al. (Citation2017) rationalized that the level at which the data are examined does not denote superiority but must be appropriate to the analytical purpose and research question. Braun and Clarke (Citation2012) stages of thematic analysis were followed to guide the process of coding and develop themes. The data have been approached with familiarization; similar meanings were clustered at the semantic and latent levels and grouped under codes. Due to the similarities presented and superficiality, given that they were responses to a survey, multiple coding was not required. The themes were constructed deductively, while new themes were included via an inductive process. Combining these approaches allowed the development of new knowledge, which fell outside the predicted themes of deductive reasoning, thus allowing a more complete analysis while distancing the researcher’s reflexive influence. The coding was done manually by the author.

3. Results

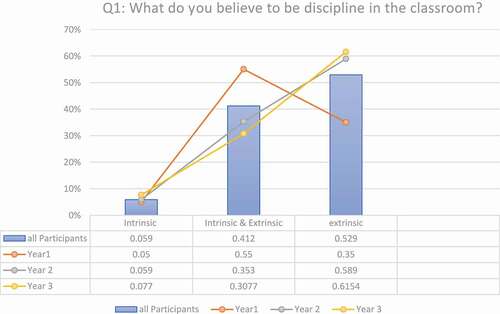

Participants were asked what they believed discipline in the classroom to be (). This was to find out the meaning attached to discipline and determine the context applied in answering questions directly related to discipline. The responses suggest that discipline holds both extrinsic and intrinsic values at a proportionally equal level. The extrinsic theme was applied to describe discipline as a superficial feature more attuned to classroom management, such as “rules/guidelines regarding time keeping/attendance classroom behaviour and etiquette” (549545–549536-60876047).

However, students also defined discipline as an extrinsic measure reasoned through morals as “listen to each other and to be fair, to show respect by not talking over anybody while they are, stay off phones” (549545–549536-54692189).

The reference to moral values, such as “mutual respect” (549545–549536-60811105) and ‘fairness’ (549545–549536-60810260), evidences the intrinsic influence of discipline, which coincides with Kohn’s (Citation1993) philosophical view that for operant conditioning to work outside the context of use wherein reinforcement/punishment is seized, it requires intrinsic motivation to do so. This aspect was reiterated by Alexio and Norris (Citation2009) who highlighted that discipline should and could be used as a tool for moral reasoning to induce behaviour in society, which is less bound by the fear of restraint but associated with the social good of others. With regard to the epistemology that behaviour can only be influenced outside the social context if it has intrinsic meaning, the data captured substantial intrinsic application to the concept of discipline, thus indicating a profound influence outside the context of the classroom. On the contrary, linking discipline to extrinsic features intensifies the debate of theoretical and practical inconsistency.

To explore the coherence in findings, age and year of study were studied. A fundamental pattern was noted from the year of study; whereas year 1 pupils frequently applied moral reasoning (intrinsic) to explain the extrinsic features of discipline, this connection decreased in later years of study (). This could be linked to progressive student autonomy over the course of the programme, which coincides with the perspectives of Darling-Hammond et al. (Citation2020), who explained that the brain and human capacities grow over the developmental spectrum (psychomotor/cognitive/affective). During latter years, deeper cognitive/affective models are engaged in, which take their relevance from behaviourist approaches suited to psychomotor domains, problem-solving, and deeper reflection. However, Darling-Hammond et al. (Citation2020) clarified that the experience within each domain works in interactive ways; what happens in one domain influences another. This rationale is crucial in understanding that although the intrinsic influence of discipline cannot be generically applied to a full programme, it is a firm foundation within the psychomotor domain (Bloom’s taxonomy) of learning, which Simpson (Citation1972) described as the level of learning where motor responses are calibrated with motivation through co-ordination and adaptation. As suggested by Darling-Hammond et al. (Citation2020), understanding the learning processes of each domain and how they interact with each other contributes to the accurate use of influence, which reflects supportive designs for learning environments.

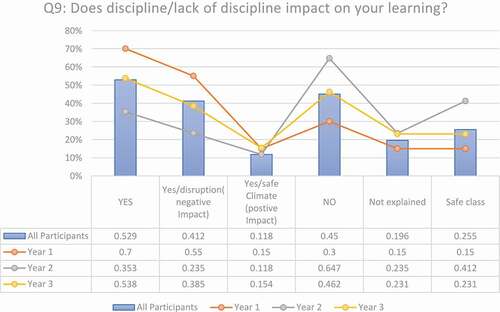

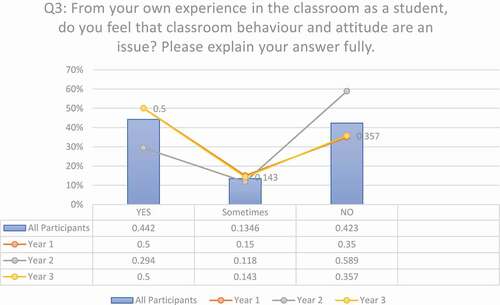

To derive an understanding of the impact of discipline on learning in the context of the classroom, participants were asked questions both directly and indirectly. At a direct level, students were asked if discipline/lack of discipline impacted on their learning and why (). At the same time, they were asked to draw on their experiences to determine whether classroom behaviour and attitude are issues and why (). Behaviour and attitude, rather than discipline, were used due to the uncertainty of how discipline is interpreted by individuals. Boynton and Greenhalgh (Citation2004) agreed with the use of themes that link to the phenomenon in question, especially where there may be variance in meaning. Both questions had similar responses and related to the impact on the goal (learning) within the context. These were expressed at both direct/indirect levels as ‘I feel that lack of discipline has had some knock in effect on my studies. I feel because of the constant talking within my cohort, that I am unable to ask questions and discuss my queries’ (549545–549536-60810364).

“The classroom bad behaviour and attitude is an issue because it disrupts a day program. Tutor is unable to perform lecture and students are missing out” (549545–549536-60811105).

These responses refer to common themes recognized in the literature as acts of classroom misbehaviour (Elias & Schwab, 2006 as cited in Debreli & Ishanova, Citation2019) while also reflecting discontent with the management of disruptions: ‘Yes. Poor punctuality/disruptive behaviours are tolerated, it can be disruptive to others’ (549545–549536-54695207).

The findings indicate a definite similarity in the level of dissatisfaction encountered by year 1 and 3 students, which is considerably higher than that encountered by year 2 students (). The similarity between year 1 and year 3 is generally explained by Doyle (Citation1986 as cited in Moles, Citation1989) and further by Lopes and Oliveira (Citation2017), who reiterated that when students are expected to develop high-level cognitive and demanding classroom work, the likelihood of misbehaviour increases. During year 1, new concepts and skills are introduced and learning within the psychomotor domain takes place. Students learn to combine new concepts in physical, mental, and vocal demeanour that equates to increased co-ordination (Simpson, Citation1972). At year 3, students are expected to study higher-level concepts within the cognitive and affective domains, which require deeper cognitive reasoning and evaluative approaches (Simpson, Citation1972). The notable decrease in dissatisfaction by year 2 students may be explained by the relaxation of intensity that is typical of their learning domain (Bloom’s taxonomy in Simpson, Citation1972). The link between engagement in learning and disruptive behaviour is strengthened in some student responses indicating that “if people find the session boring they may get distracted and then this contributes to a wider attention problem which could affect the way other people learn too” (549545–549536-61629682).

Gore and Parkes (Citation2008) agreed with this explanation and referred to disruptive behaviour as a consequence rather than a precondition of effective didactics. Lopes and Oliveira (Citation2017) added that teachers who focus on the engagement of students in class content consequently prevent misbehaviour from occurring.

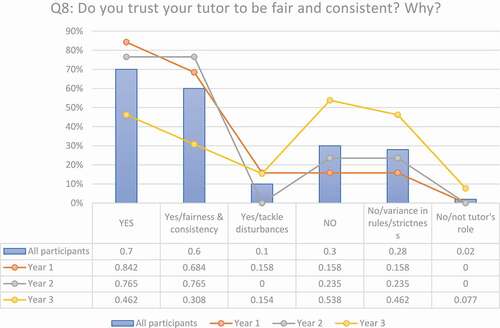

To add to this understanding, students were asked their opinion on the tutor’s approach to discipline specifying fairness and consistency (). This coincides with previous research suggesting that although students are usually the source of lack of discipline due to underlying problems, they are not the only source (Debreli & Ishanova, Citation2019). Discipline is synchronous to the actions taken by the tutor to end lack of discipline and restore order (Kulinna et al., Citation2006). Lopes and Oliveira (Citation2017) stipulated that discipline is as much reliant on the characteristics, clarity, and conduct of the tutor, as the comprehension of students within the classroom. Students reported tutor attributes positively in the main addressing that “Generally, tutors are consistent regarding classroom behaviour/attitude and in my experience they have addressed issues with students who were being disruptive, which resulted in much improvement in classroom discipline. It makes me confident that if further issues would arise, they will be sorted” (549545–549536-56207586).

Overall, statements indicate that fairness and consistency are perceived as being enacted through the handling of disruption. However, several responses pointed out the lack of consistency between tutors’ rules.

‘I feel that the approach to discipline varies greatly between tutors as each has their own style. Some are more vocal about enforcing etiquette while others are more “laid back”. That’s an observation and not a criticism as I think different teaching styles create different learning opportunities for students. However, for consistency in relation to etiquette, it might help for tutors to facilitate us as a group to revisit the agreed “ground rules” and discuss these on a regular basis’ (549,545–549,536-5,471,380).

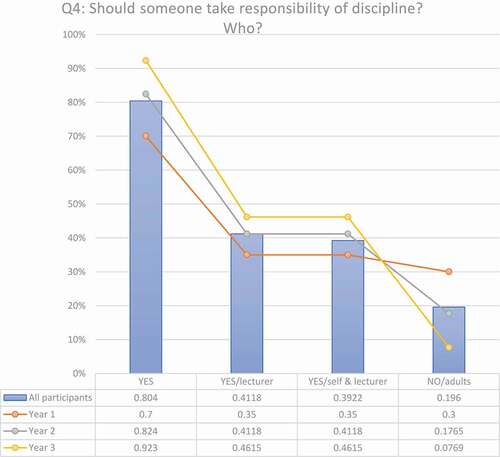

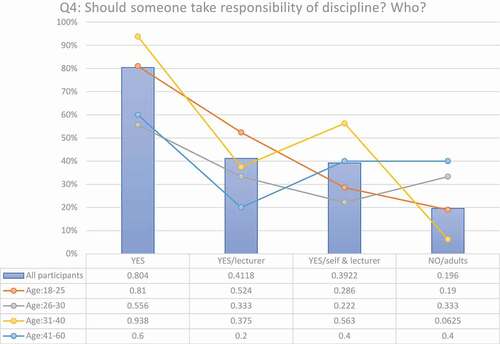

Research by Irby and Clough (Citation2015) similarly stated that consistency between tutors is important to help students understand and comply with school rules and expectations. However, earlier studies indicated that collaborative understanding between teacher and student allows control to be obtained through involvement in the process, whereby students are prompted ‘to take responsibility for their actions but need active involvement of a kind but firm teacher’ (Wolfgang & Glickman, Citation1986, p. 9). This perspective coincides with participants’ responses, which clearly articulate favour in collaborative approaches ().

“I think that the responsibility should lie with students and lectures and there should be an agreed set of rules to maximise learning” (549545–549536-60809313).

“This is a difficult issue as we are all adult learners. I feel this means we are not only responsible for our own behaviour but also have a role in reminding others about agreed etiquette. However, this is not easy from a peer perspective, therefore input from tutors is useful to maintain etiquette” (549545–549536-54713808).

These perspectives further correspond to studies on student-led learning (McCabe & O’Connor, Citation2014), which describe partnership as a productive, critical, and reflexive means of encouraging an educational relationship (Baeten et al., Citation2010; McCabe & O’Connor, Citation2014).

Age characteristics further highlight a distinctive relationship between the age of students and who they feel should take responsibility of discipline (). Students in the younger age range (18–30 years) felt that responsibility of discipline should be taken by the lecturer. This is reasoned through comments such as “The lecturer is leading the session and delivering the lesson/sharing knowledge so they should take the lead and responsibility” (549545–549536-54686298) and “the lecturer as it is there class” (549545–549536-54694536).

This disparity was clarified by Monaco and Martin (Citation2007, p. 45), who explained that millennial students (born between 1981 and 2002) have special characteristics and are generally “sheltered” individuals who work best with structure, clear rules, and regulations (Blue & Henson, Citation2015). Smith-Stoner and Molle (Citation2010) added that although millennials are self-confident, they have high expectations from their tutors and need affirmation.

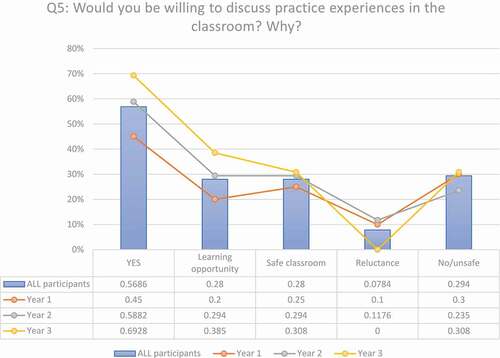

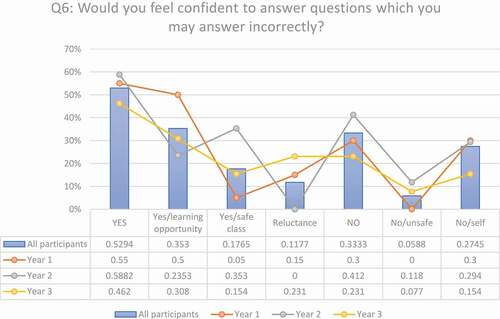

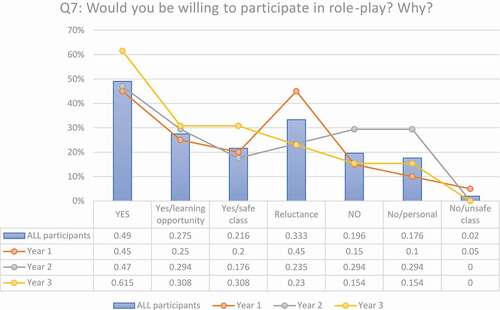

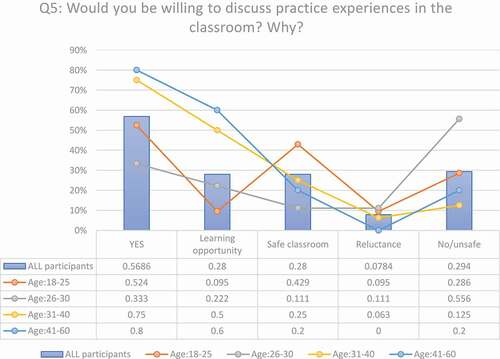

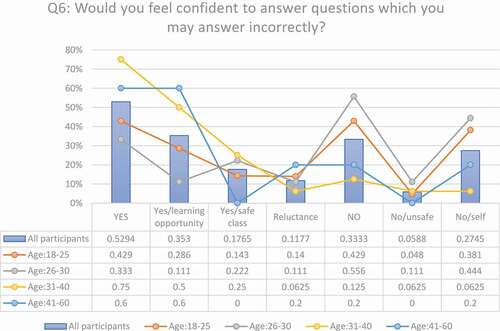

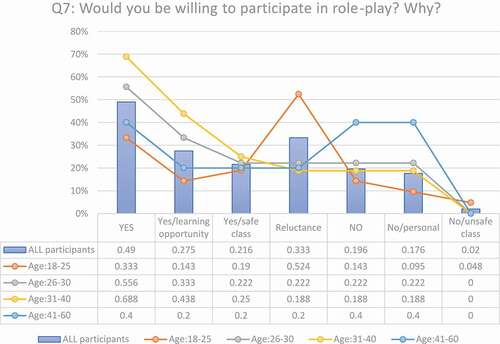

Discipline in the context of the classroom is often used and predicted to have a key influence on the learning conditions that allow students to feel safe in participating in various learning systems. Several questions were formatted to enquire whether students felt psychologically safe in the classroom and whether these were rationalized with concepts of discipline, with a prime focus on behaviour and attributes (questions 5, 6, and 7). Several studies defined psychological safety as the degree to which people view the environment as conducive to interpersonal risky behaviours, such as speaking up or asking for help, which are perceived as salient variables in environments where learning matters (Edmondson et al., Citation2016). Students were asked whether they would be willing to discuss their clinical experiences in the classroom, answer questions regarding uncertainty, and participate in role-play (). Wanless (Citation2016) suggested that comparing the challenge of multiple tasks allows the determination of the level of psychological safety present since it allows an understanding of the interpersonal risk attached to the task. Students expressed confidence in discussing experiences through rationalizing that “it is an important part of learning and we can learn from others experience and also assist in emotional support” (549,545–549,536-60,810,260).

At the same time, a high proportion of students rationalized their confidence to participate by claiming that ‘I feel safe within my group as we talk about confidentiality and having a group to confide in takes away anxieties’ (549545-549536-60813187).

Edmondson (Citation2003) suggested that words expressing, support, empathy, comfort, and trust are associated to increased levels of psychological safety.

However, responses to questions about uncertainty triggered an increased the level of reluctance () through expressions of “I don’t mind being wrong if it’s a learning opportunity … but as mentioned earlier if I thought it would prompt the sniggers from other students I probably wouldn’t say anything” (549545–549536-60837355).

The latter response suggests that reluctance in participation is often based on behaviour predicted from attitudes. The relationship between attitude and behaviour has been rigorously researched by psychologists in the pursuit of predicting behaviour (Lawton et al., Citation2009). However, an interesting perspective is explained through Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, Citation1957), which determines the level of mental discomfort when attitudes are not synchronized with behaviour. The theory suggests that humans rely on restoring the balance of these by changing one or the other, which explains the strength in the relationship between both. This illustrates how students predict behaviour through the prominence of attitudes, which are predispositions held by individuals and often known by students through previous interactions and experiences. Zanna and Rempel (Citation1988:7) agreed; they defined attitudes as “units of social knowledge that are based on experience, convictions and feelings caused by the object of this attitude”. Other students further exemplified the prerequisite of desirable attitude for increased safety in participation by exclaiming “Sometimes, with members of the group I feel comfortable with and ones who are enthusiastic to listen” (549545–549536-60840668).

Understanding the value of attitudes to feelings of safety highlights the importance of discipline, which aims to influence attitude-behaviour consistency through the application of values. Classroom management techniques which may be successfully applied in cases of misbehaviour lack the capacity to control attitudes or reluctance from predicted behaviour. Discipline that intrinsically motivates individuals to rationalize with compassion, respect and fairness acts inherently on the attitudes underpinning consequent behavioural expressions, which classroom management has limited capacity to control.

This is further evidenced by the words of students who claim that “I think it all depends by the teachers if they are able to monitor the situation without let the student feeling to be in error” (549,545–549,536-55,296,943).

However, regardless of rigorous monitoring under classroom management structures, attitudes or intentions cannot be evidenced unless enacted on to allow their management, thus defeating the objective of these measures to create safe learning conditions.

Despite the reference to others in the reluctance to partake in learning tasks, disapproval is further elevated when asked to participate in role-play (), through combined rationales expressing “I’d be nervous as I feel I may be judged by some of the students in the class, I also do not like doing things like that” (549,545–549,536-54,694,536).

Wanless (Citation2016) suggested that intolerable levels of threat towards identity or one’s sense of self are an indication of a high level of lack of safety. The word choices of “uncomfortable” (549,545–549,536-54,779,576), “embarrassing” (549,545–549,536-60,876,047) and “feeling judged” (549,545–549,536-54,694,536) are further outlined in the literature as descriptions of interpersonal lack of safety (Edmondson, Citation2003). Delizonna (Citation2017) explained that when the brain processes provocation, competition, or dismissive subordinates, the amygdala initiates a fight or flight response that shuts down perspective and analytical reasoning. She suggests that it is important to understand the difference between challenge and threat since a challenge works in an opposite direction by increasing the levels of oxytocin in the brain, thereby eliciting trust and trust-making behaviour and positively impacting performance.

Participant responses provided supplementary factors that would alleviate some fears and increase the level of psychological safety such as “I find the role play scenarios OK if it was in small groups but don’t particularly like it when presenting it back to the whole class. I find it a bit embarrassing/awkward” (549,545–549,536-60,876,047) or “reluctant but depends which tutor as some are way nicer than others” (549,545–549,536-54,846,708).

A greater understanding of the various factors associated with different tasks allows tasks to be presented as a challenge rather than posing an unnecessary threat, which not only shuts down learning paradigms but also causes undue stress and trauma (Delizonna, Citation2017).

Patterns that compare year of study and age drew a divergent perspective. The year of study comparison suggests that confidence in participating progresses with each year of study, indicating an apparent link between tenacity in participation and progressing confidence. This is further supported by the age comparison data, which draw a connection between rate of participation and increasing age (). An interesting pattern was noted in the younger age groups, where there was an obvious association between the will to participate and one’s feeling within the classroom, suggesting that younger students are more reliant on safety than mature students (Smith-Stoner & Molle, Citation2010).

4. Discussion

The central contribution of this research suggests that discipline in the higher education classroom can be used as an effective behavioural strategy to condition behaviour by applying intrinsic moral values to attributes (Alexio & Norris, Citation2009). Students were asked to define discipline in the classroom to determine its predisposition either intrinsically or extrinsically. Intrinsic motivation determines the feasibility of its use as a strategy to develop value-based attributes that in turn allow transferability outside the context of its application (Kohn, Citation1993; Schwartz, Citation1992; Schwartz et al., Citation2012). This idea further addresses the concerns of shaping professional/graduate attributes with educational partnerships, thus allowing consistency and flow between theory and practice. However, this research was not conducted with the intention of exploring whether a theory–practice gap exists. The significance in the proportion of students who rationalized discipline with extrinsic purposes indicates weak cognitive attribution of behaviour to values/moral reasoning, which are integral foundations of healthcare professionalism. Thus, the emergence of this thread reinforces the efforts made to address the presence of incivility and culturally compliant attributes (Cameron, Citation2013; Katz et al., Citation2019).

The contextualization of data has addressed how discipline (that is intrinsically motivated) succeeds classroom management (that is associated with autocracy and control) and incurs similar results in managing disruption while addressing the partnered responsibility sought between tutor and adult learners (Baeten et al., Citation2010; McCabe & O’Connor, Citation2014). A meaningful contribution of this research on safety in the classroom highlights attitudes as contributors to a perceived lack of safety, which due to the concealment of intentions and predisposition is less likely to be controllable by means of classroom management strategies. However, since discipline trains individuals intrinsically through moral abstinence/obligation, it has the innate capacity to underpin attitudes that in turn create safe conditions for learning (Schwartz et al., Citation2012). Along with tutor characteristics, findings have addressed misbehaviour as a consequence of disengagement with learning strategies, which strengthens existing research in the field of misbehaviour (Debreli & Ishanova, Citation2019; Kulinna et al., Citation2006; Lopes & Oliveira, Citation2017). Additionally, safety in the classroom and group size, which although coherent within the context are also useful in raising critical consciousness and deepening understanding of practice, are interlinked. On reflection, the findings are a catalyst for insight since they signify the importance of learning engagement. Learning strategies used between years/levels of learning should be designed in partnership with students rather than employing pre-intended strategies, thereby allowing engagement to be aligned with diversity, pace, and level of cognitive demand, which in turn extracts extrinsic intrusion systematically. At the same time, the interpersonal risk associated with learning strategies must not be underestimated since it outdoes the intended benefits while placing additional strain and stress on learners. The findings provide useful grounds for further research since interpersonal factors have significantly and vividly been applied to reluctance in participation. This provides suggestions for further transformative strategies to develop interpersonal skills, which will not only improve learning engagement but also allow the formation of transferable skills to work within environments known to improve team performance. Ultimately, in healthcare, the development of interpersonal skills will support improvement and address the consequences related to the fear of raising concerns within hierarchical, multidisciplinary teams.

5. Conclusions

This research provides a meaningful contribution to the higher education sector, with an emphasis on professional programmes where learning is aligned to theory and practice. The findings suggest that discipline in the higher education classroom is substantially rationalized with intrinsic purposes that determine strong grounds for transferability outside the context of the classroom. Since values are widely held moral codes of conduct, the findings apply to diverse contexts and disciplines. Ultimately, the findings from this research support the need to intensify the use of discipline to develop respectful and supportive attitudes in individuals; such attitudes inadvertently manage disruptions and create safe learning conditions. The context of an adult learning environment that transitions from a hierarchical establishment of control and order to student-led learning and partnered responsibilities further enhances the claim to move from classroom management to classroom discipline.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fazeela Patel

Fazeela Patel is a lecturer of perioperative studies in higher education, born and based in the UK. Transition from leadership in clinical practice to adult learning has reinvigorated her previous research on “workplace culture”. While culture itself involves multiple facets which are deeply rooted, “Discipline in the Higher Education Classroom: a study of its intrinsic influence on professional attributes, learning and safety” marks a starting point with the future workforce in addressing the wider phenomenon of culture. The author perceives education as pivotal in developing a stature of integrity characterised by one’s attributes and controlled actions. Higher education today appears to be a fast lane with an overwhelming emphasis on the extrinsic acquisition of skills, risking movement from the training of deeper intrinsic enquiry to stagnate cultures. The author has a profound interest in uncovering the roots of education as one that empowers individuals to think deeply with independence and freedom; unconstrained from the influence of cultural norms.

References

- Al Baghal, T. (2017). An introduction to questionnaire design [streaming video]. SAGE Research Methods video. https://methods.sagepub.com/video/an-introduction-to-questionnaire-design

- Alexio, P., & Norris, C. (2009). Moral reasoning development and classroom discipline. Education and Health, 27(21), 9–23. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283074574_Moral_reasoning_development_and_classroom_discipline

- Allen, M. (2017). The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. SAGE Reference.

- Baeten, M., Kyndt, E., Struyven, K., & Dochy, F. (2010). Using student-centred learning environments to stimulate deep approaches to learning: Factors encouraging or discouraging their effectiveness. Educational Research Review, 5(3), 243–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.06.001

- Barbour, R. S. (2018). Quality of data collection. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data collection (pp. 217–229). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Barnett, R. (2009). Knowing and becoming in the higher education curriculum. Studies in Higher Education-Oxford, 34(4), 429–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902771978

- Bellon, J. J., Bellon, E. C., & Blank, M. A. (1992). Teaching from a research knowledge base: A development and renewal process. Maxwell Macmillan International.

- Berwick, D. (2013). Francis Report: PM statement on Mid Staffs Public Inquiry. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/francis-report-pm-statement-on-mid-staffs-public-inquiry

- Blue, C., & Henson, H. (2015). Millennials and dental education: Utilizing educational technology for effective teaching. Journal of Dental Hygiene, 89(Suppl. 1), 46–47. scholar.google.co.uk/scholarq?=millennials+and+dental&hl+en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart

- Bossone, R. M. (1964). What is classroom discipline? The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 39(4), 218–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.1964.11476679

- Boynton, P. M., & Greenhalgh, T. (2004). Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire. BMJ, 328(7451), 1312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7451.1312

- Bransford, J., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R., National Research Council. (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience and school. National Academies Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper (Ed.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

- British Educational Research Association (BERA). (2011). Ethical guidelines for educational research. https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018

- Cameron, D. (2013). Francis Report: PM statement on Mid Staffs Public Inquiry. GOV.UK https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/francis-report-pm-statement-on-mid-staffs-public-inquiry

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Coleman, G. (2015). Core issues in modern epistemology for action researchers: Dancing between knower and known. In H. Bradbury (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of action research. (pp. 392-400). SAGE Publications.

- Collins Dictionary. (2020). Definition of ‘discipline’. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/discipline

- Council of Deans of Health. (2013). Position statement. ODP Pre-registration Programmes Educational Threshold. http://www.councilofdeans.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ODP-BSc-Threshold-position-20131030-final1.pdf

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791

- Debreli, E., & Ishanova, I. (2019). Foreign language classroom management: Types of student misbehaviour and strategies adapted by the teachers in handling disruptive behaviour. Cogent Education, 6(1), 1648629.

- Delizonna, L. (2017, August 24). High-performing teams need psychological safety. Here’s how to create it. Harvard Business Review, https://hbr.org/2017/08/high-performing-teams-need-psychological-safety-heres-how-to-create-it

- Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (DBIS). (2009). Higher ambitions: The future of universities in a knowledge economy.

- Doyle, W. (1986). Classroom organization and management. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching: A project of the American educational research association (pp. 392–431). Macmillan.

- Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419–1452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00386

- Edmondson, A. C., Higgins, M., Singer, S., & Weiner, J. (2016). Understanding psychological safety in health care and education organizations: A comparative perspective. Research in Human Development, 13(1), 65–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1141280

- Ervin, R. A., Ehrhardt, K. E., & Poling, A. (2001). Functional assessment: Old wine in new bottles. School Psychology Review, 30(2), 173–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2001.12086107

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Garnick, J. (2005). A deeper look at theory and practice. International Association of Sufism. https://ias.org/departments/sufipsychology/spf-articles/a-deeper-look-at-theory-and-practice/

- Garran, A. M., & Rasmussen, B. M. (2014). Safety in the classroom: Reconsidered. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 34(4), 401–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2014.937517

- General Medical Council (GMC). (2021). Code of conduct for Council members. https://www.gmc-uk.org/about/how-we-work/governance/council/code-of-conduct

- Given, L. (Ed.). (2008). The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE Publications.

- Gore, J. M., & Parkes, R. J. (2008). On the mistreatment of management. In A. Phelan. & J. Sumsion (Eds.), Critical readings in teacher education (pp. 1–16). Sense Publishing.

- Haddock, G., & Maio, G. R. (Eds.). (2004). Contemporary perspectives on the psychology of attitudes. Psychology Press.

- Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC). (2016). Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. https://www.hcpc-uk.org/standards/standards-of-conduct-performance-and-ethics/

- Herek, G. M. (1987). Can functions be measured? A new perspective on the functional approach to attitudes. Social Psychology Quarterly, 50(4), 285–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2786814

- Horner, J. (2003). Morality, ethics and law: Introductory concepts. Seminars in Speech and Language, 24(4), 263–274. https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/ https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2004-815580

- Ioakimidis, M., & Myloni, B. (2010). Good fences make good classes: Greek tertiary students’ preferences for instructor teaching method. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 2(2), 290–308. https://iojes.net/?mod=tammetin&makaleadi=&makaleurl=IOJES_207.pdf&key=41356

- Irby, D., & Clough, C. (2015). Consistency rules: A critical exploration of a universal principle of school discipline. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2014.932300

- Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(2), 163–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/266945

- Katz, D., Blasius, K., Isaak, R., Lipps, J., Kushelev, M., Goldberg, A., Fastman, J., Marsh, B., & DeMaria, S. (2019). Exposure to incivility hinders clinical performance in a simulated operative crisis. BMJ Quality & Safety, 28(9), 750–757. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-009598

- Kohn, A. (1993). Punished by rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Kulinna, P. H., Cothran, D. J., & Regualos, R. (2006). Teachers’ reports of student misbehavior in physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 77(1), 32–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2006.10599329

- Lawton, R., Conner, M., & McEachan, R. (2009). Desire or reason: Predicting health behaviors from affective and cognitive attitudes. Health Psychology, 28(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013424

- Liamputtong, P. (2011). Focus groups methodology: Principles and practice. SAGE Publications.

- Lopes, J., & Oliveira, C. (2017). Classroom discipline: Theory and practice. In J. P. Bakken (Ed.), Classrooms: Academic content and behaviour strategy instruction for students with and without disabilities (pp. 231–253). Nova Science Publishers.

- McCabe, A., & O’Connor, U. (2014). Student-centred learning: The Role and responsibility of the lecturer. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(4), 350–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2013.860111

- Melechi, A. (2020, 13 February). Bad behaviourism: Analysing a psychological phenomenon. world.edu. Global education network. https://world.edu/bad-behaviourism-analysing-a-psychological-phenomenon/

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

- Mertler, C. A. (2017). Action research: Improving schools and empowering educators. SAGE Publications.

- Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E. (2010). Encyclopedia of case study research. SAGE Publications.

- Moles, O. C. (1989). Strategies to reduce student misbehaviour. In Office of educational research and improvement (ED). Office of Research, (1-187). eric.ed.gov/?id=ED311608

- Monaco, M., & Martin, M. (2007). The millennial student: A new generation of learners. Athletic Training Education Journal, 2(2), 42–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4085/1947-380X-2.2.42

- Norris, J. A. (2003). Looking at classroom management through a social and emotional learning lens. Theory Into Practice, 42(4), 313–318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4204_8

- Nursing & Midwifery Council (NMC). (2018). Future Nurse: Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/standards-for-nurses/standards-of-proficiency-for-registered-nurses/

- Online Etymology Dictionary. (2020). Definition of discipline. https://www.etymonline.com/word/discipline

- Parker, J. (2003). Reconceptualising the curriculum: From commodification to transformation. Teaching in Higher Education, 8(4), 529–543. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1356251032000117616

- Peach, S. (2010). A curriculum philosophy for higher education: Socially critical vocationalism. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(4), 449–460. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.493345

- Ramrathan, L., Le Grange, L., & Shawa, L. B. (2017). Ethics in educational research. In L. Ramrathan, L. Le Grange, & P. Higgs (Eds.), Education studies for initial teacher education (pp. 432–443). Juta.

- Roberts, K., Dowell, A., & Nie, J.-B. (2019). Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data; a case study of codebook development. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y

- Saxena, D., Singhal, D., & Patel, M. (2015). Comment on student–teacher research: A dilemma between power, ethics, and morality. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, 63(1), 76–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/0301-4738.151485

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theory and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1–65). Academic Press.

- Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Davidov, E., Fischer, R., Beierlein, C., Ramos, A., Verkasalo, M., Lönnqvist, J.-E., Demirutku, K., Dirilen-Gumus, O., & Konty, M. (2012). Refining the theory of basic individual values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 663–688. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029393

- Simpson, E. J. (1972). The classification of educational objectives in the psychomotor domain. Gryphon House.

- Smith-Stoner, M., & Molle, M. E. (2010). Collaborative action research: Implementation of cooperative learning. Journal of Nursing Education, 49(6), 312–318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20100224-06

- Sprick, R. S. (2013). Discipline in the secondary classroom: A positive approach to behaviour management. Jossey-Bass.

- Stalmeijer, R. E., Mcnaughton, N., & Van Mook, W. N. (2014). Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Medical Teacher, 36(11), 923–939. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.917165

- Stickley, T., & Freshwater, D. (2018). Emotional intelligence for health care professions-professional compathy. In L. D. Pool & P. Qualter (Eds.), An introduction to emotional intelligence (pp. 149–160). John Wiley & Sons.

- Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. In C. Willig & W. Stainton Rogers (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 17–37). SAGE Publications.

- Wanless, S. B. (2016). The role of psychological safety in human development. Research in Human Development, 13(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2016.1141283

- Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20(2), 158–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0074428

- Way, S. M. (2016). School discipline and disruptive classroom behaviour: The moderating effects of student perceptions. The Sociological Quarterly, 52(3), 346–375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01210.x

- Wolfgang, C. H., & Glickman, C. D. (1986). Solving discipline problems: Strategies for classroom teachers. Allyn and Bacon.

- Xerri, D. (2017). Using questionnaires in teacher research. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 90(3), 65–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2016.1268033

- Yahaya, Z. S. (2020). Employee inclusion during change: The stories of middle managers in non-profit home care organizations. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 32(3), 165–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822320901442

- Zanna, M. P., & Rempel, J. K. (1988). Attitudes: A new look at an old concept. In D. Bar-Tal & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), The social psychology of knowledge (pp. 315–334). Cambridge University Press.