Abstract

While many studies indicate that “virtual exchanges” also known as telecollaboration are useful for developing intercultural communicative competence, there is a paucity of research on how learners acquire new knowledge related to their own culture and society before interacting with online foreign exchange partners. This study explores the potential of applying an inquiry-based strategy in developing students’ intra-cultural awareness to enhance the quality of their intercultural communication. A quasi-experimental design involving undergraduate students in Japan (n = 112) was developed to assess the effectiveness of an inquiry-based telecollaboration using explicit instruction in experimental group compared with unassisted intra-cultural telecollaboration in control group. Quantitative results indicated that while several outcomes on telecollaborative tasks and intra-cultural learning were not significantly different across conditions, students learning in an inquiry-based environment reported higher levels of engagement as well as confidence toward potential intercultural communication. Qualitative results also showed deeper intra-cultural learning in the experimental group. The findings suggest that while allowing students to engage in an online exploration of their culture could improve the quality of future intercultural exchanges by expanding students’ intra-cultural knowledge, the integration of an inquiry-based framework could have additional positive effects on learner engagement, deeper learning, and confidence toward intercultural communication.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In recent years, virtual exchanges also known as telecollaboration have been gaining popularity among scholars, teachers, and students engaged in foreign language education because it facilitates the use of Internet-mediated communication tools to connect language and culture learners in geographically distant locations. Telecollaboration, as currently viewed in academic and classroom settings, places greater emphasis on the development of learners’ intercultural communicative competence.

The problem with this approach is that this process may not consider the possibility that learners engaged in online intercultural exchanges could have limited knowledge about certain aspects of their own lingua-culture. We propose that, for learners to effectively share lingua-cultural knowledge with their online peers, an inquiry-based model of intra-cultural telecollaboration could support the construction of learners’ lingua-cultural knowledge and provide a stronger foundation for intercultural learning and communication. To test this model, we have conducted a quasi-experimental study in Japan using mixed methods.

1. Introduction

Due to decreased international travel and face-to-face intercultural communication in the face of the global pandemic, telecollaboration is expected to gain even more popularity among scholars, teachers, and students engaged in foreign language and intercultural communication education. Telecollaboration allows learners to engage with representatives of other cultures in geographically distant locations through accessible synchronous and asynchronous information and communication technology. The main objective of such telecollaborative exchanges is not only to provide a platform for foreign language practice but also to promote the development of intercultural communicative competence through cross-cultural interaction (Byram, Citation1997), exchange (Belz & Thorne, Citation2006), and structured tasks (O’Dowd & Dooly, Citation2020; O’Dowd & Waire, Citation2009). Such projects, typically facilitated by their respective institutions, provide learners the opportunity to learn about other cultures and their socio-linguistic norms without leaving the supportive context of their foreign language classroom (O’Dowd, Citation2012; Thorne, Citation2010).

While the foreign language and intercultural communicative learning aspects of telecollaboration have been extensively studied by researchersto date, intra-cultural learning has not been sufficiently addressed in the literature on technology-mediated language learning and communication (e.g., Yeh et al., Citation2020). In particular, the examination of the most recent systematic reviews of telecollaboration (e.g., Çiftçi, Citation2016; Çiftçi & Savaş, Citation2018; Lewis & O’Dowd, Citation2016) indicates that the intra-cultural learning aspect in an online intercultural exchange setting is the least academically researched, if not entirely neglected. Apparently, there is a need to further explore telecollaboration through the prism of intra-cultural reflection, given that online exchanges and foreign language instruction are no longer about producing near-native speakers but, in the words of Byram (Byram, Citation1997, 12), intercultural speakers can ‘see and manage the relationships between themselves and their own cultural beliefs, behaviours, and meanings […] and those of their interlocutors.’

Intracultural learning, therefore, refers to learning about one’s own culture and socio-linguistic norms, which helps learners to explore their own cultural heritage and identities and share these with representatives of other cultures (Collier et al., Citation1986). It is an important step toward enabling learners to become intercultural communicators and share ideas with people from different cultural backgrounds (Guth & Helm, Citation2010; O’Dowd & Dooly, Citation2020). Recent research suggests that intra-cultural learning can enhance learners’ communication skills, enrich their discussion when talking to foreigners, and boost their confidence toward communication through acquisition of in-depth knowledge and appreciation of cultural diversity (Su, Citation2018; Yeh et al., Citation2020). Belz (Belz & Thorne, Citation2006) contends that telecollaboration pieces together language and inter- and intra-cultural learning to help learners become more effective communicators.

This study attempts to empirically test the use of inquiry-based learning during an intra-group online exchange (i.e., telecollaboration) and assess its impact on nurturing students’ intra-cultural learning to enhance the quality of future intercultural communication. The current research employed a classroom-based quasi-experimental design using mixed methods. It involved five intact undergraduate online classes assigned to the experimental condition (i.e., participating in a five-phase inquiry-based telecollaboration) and the control condition (i.e., participating in a telecollaborative exchange not requiring an in-depth inquiry). Moving telecollaboration in this direction could expose not only challenges (Çiftçi & Savaş, Citation2018), but also opportunities by increasing teachers’ role in prompting, guiding, and communicating with students. The goal is to model and encourage deeper reflection, with both teachers and learners provided with ongoing and experiential reflective opportunities (Çiftçi & Savaş, Citation2018; Godwin-Jones, Citation2019). It should also be noted that the study itself is not the inquiry-based model; what is presented here is a study on the model and the effects it had on students’ intracultural learning and possible future intercultural communication.

2. Literature review

2.1. Telecollaboration in higher education

Increase in Internet speed and the transition to Web 2.0—which refers to websites that emphasise user-generated content, participatory culture, growth of social networks, multi-directional communication, and significant diversity in content types (Cormode & Krishnamurthy, Citation2008)—has popularised the use of telecollaboration to promote language learning among instructors and learners who use it as an economical and accessible means of contact and collaboration with speakers of other languages (Dooly, Citation2017; Furstenberg & Levet, Citation2010; Liaw & Master, Citation2010). Telecollaborative projects involving the use of interactive Internet technologies are being implemented to link foreign and second-language learners in institutionalised settings in different countries to engage in cost-effective exchanges for developing intercultural awareness and linguistic proficiency (Kern, Citation2006; Liaw & Master, Citation2010; O’Dowd, Citation2012).

O’Dowd and Waire (Citation2009) identified three categories of tasks to systematise telecollaborative exchange: (1) information exchange, (2) comparison/analysis, and (3) collaboration/product creation. Information exchange tasks involve authoring “cultural autobiographies,” conducting online interviews, engaging in informal discussions, and exchanging stories. Comparison/analysis tasks include comparing parallel texts and questionnaires, analysing cultural products and translating. Collaboration/product creation includes working together to create products, transforming text genres, conducting “closed outcome” discussions, and making cultural adaptations.

Studies over the past two decades have provided important information on the benefits of telecollaboration in higher education, including expanding L2 pragmatic competence among foreign language learners (Belz & Kinginger, Citation2003; Cunningham, Citation2016; Kim & Brown, Citation2014), enhancing grammatical proficiency (Lee, Citation2002), vocabulary (Dussias, Citation2006), and spoken communication (Abrams, Citation2003). Other studies have reported positive outcomes in enhancing students’ independent learning and developing multiliteracies that include digital, organisational, and critical skills (Guth & Helm, Citation2010).

2.2. Intra-cultural communication and intra-cultural learning

The introduction of the concept of intercultural communicative competence has led to a focus on raising learners’ awareness of how their own cultural background and assumptions may impact their attitudes towards and communication with people from other cultures (Alred et al., Citation2003; Corbett, Citation2003). A key characteristic of intercultural communicative competence is the fact that it prepares learners for exposure to all cultures, including their own (Mughan, Citation1999). This is where the notion of intra-cultural communication gains prominence; thus, at least in theory, it should emerge as a crucial component in online intercultural exchange projects.

Samovar and Porter (Citation2001) defined intra-cultural communication as communication that takes place between members of the same dominant culture, but with different values, as opposed to intercultural communication, which is the communication between two or more distinct cultures. According to Kecskes (Citation2012), this approach has led to a common but misinformed perception of inter-culturality as the main reason for miscommunication (House, Citation2003; Kecskes, Citation2008). Intra-cultural communication is dominated by preferred ways of saying things and, according to Kecskes (Citation2008), it helps to organise thoughts within a particular speech community. This occurs differently in intercultural communication because the development of “preferred ways” requires time and conventionalisation within a speech community due to the flexibility of human languages (Kecskes, Citation2012).

Intra-cultural communication is intertwined with the notion of intra-cultural learning. All knowledge and information are formed or received by learners at a certain time via family, school, or media (Pinker, Citation1999). This is especially true regarding learners’ own culture, native language, and norms of communication. This knowledge forms unwittingly through daily repetitive exposure, as evidenced by an average, healthy child less than six years who already can speak her mother tongue without ever attending a language class (Chaney, Citation2001). Typically, by early adolescence, this native cultural knowledge has already been formed to the extent that it allows the person to communicate with other members of the same community not only grammatically but also in culturally appropriate ways. The process of L1 lingua-cultural knowledge development slows by early adulthood but does not end completely (Crawford-Lange & Lange, Citation1987). Byram (Citation1997) proposed the concept of “critical cultural awareness,” defined as “an ability to evaluate critically and based on explicit criteria, perspective, practices and products in one’s own and other cultures and countries” (53). Similarly, Risager (Citation2007) suggested that intercultural competence comprises knowledge, skills, and attitudes at the interface between several cultural areas, including the students’ own culture and a target culture.

2.3. Inquiry-based learning and its potential use in intra-cultural telecollaborative exchanges

Inquiry-based learning uses a systemic approach in constructing new knowledge by following certain procedures, methods, and practices (Keselman, Citation2003). Inquiry-based learning according to Pedaste et al. (Citation2012) is a process of discovering new causal relations, with the learner formulating hypotheses and testing them by conducting experiments and/or making observations. Several studies support the effectiveness of inquiry-based learning as an instructional approach (Alfieri et al., Citation2011; Furtak et al., Citation2012). Research has also shown that guided inquiry-based learning can improve different inquiry skills, such as identifying problems, formulating questions, collecting and analysing authentic information, and presenting results and conclusions (Mäeots et al., Citation2008).

An inquiry-based model of online intercultural exchange can promote active learning because participants are expected to collect authentic knowledge by engaging members of their own community and then share the findings with their online exchange partners. Inquiry-based activity creates authentic contexts, and research in cognitive science highlights its role in effective learning (Greeno et al., Citation1996). Edelson et al. (Citation1999) claim that authentic activities provide learners with the motivation to acquire new knowledge, an opportunity to incorporate it into their existing knowledge, and conditions in which to apply this knowledge in real life. While the transmission and reception of knowledge in conventional online intercultural exchange is passive, an inquiry-based model is active. To understand this connection, one should recognise that inquiry itself is a process containing smaller, logically connected units (phases) that guide learners and draw attention to important features of scientific thinking. This set of connections represents an inquiry cycle (Pedaste et al., Citation2015).

Various academic studies of inquiry-based approaches to learning and teaching have attempted to propose different versions of an inquiry cycle. For example, in their meta-analysis of the strengths of over 30 inquiry-based learning frameworks, Pedaste et al. (Citation2015) suggested five distinct general inquiry phases: orientation, conceptualisation, investigation, conclusion, and discussion. An inquiry cycle developed by White and Frederiksen (Citation1998) also identified five inquiry phases, labelled question, predict, experiment, model, and apply.

Because our main concern about the effective implementation of telecollaboration as a medium of intercultural learning is the possible lack of host members’ knowledge of their own culture, the inquiry methods, especially those related to observation, identifying problems, formulating questions, and conducting experiments (interviews, surveys, etc.), provide a framework for the construction of intra-cultural knowledge aimed at enhancing learners’ self-reflection and self-awareness. This telecollaboration model thus introduces an important new phase in the online exchange process that is designed to help host members discover authentic intra-cultural knowledge through inquiry within their own lingua-cultural environment.

As a practice aimed at discovering authentic perspectives within one’s own culture (stereotypes, perceptions, beliefs, norms of behaviour) and language (patterns of verbal and non-verbal communication, geographic peculiarities of language), inquiry-based telecollaboration provides a valuable context generating new intra-cultural knowledge in learners to promote informed intercultural communication. Howeverto date, this field has received very little attention from researchers of telecollaboration.

3. Conceptual framework

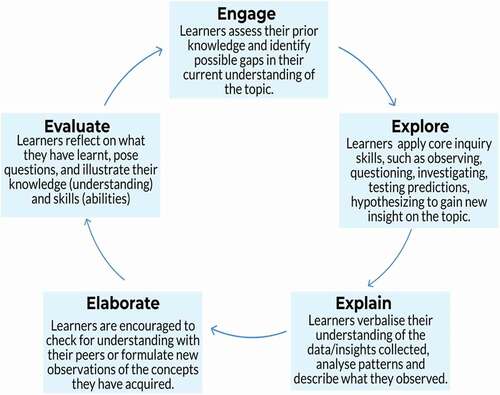

There are many variations proposed as a model for inquiry-based teaching. For this intervention, this study is based on the 5E Inquiry Model (Bybee et al., Citation2006). The model has five phases, which all begin with the letter “e”: engagement, exploration, explanation, elaboration, and evaluation (). This approach is useful for inquiry-based telecollaborative design because it provides a format for online exchange that builds on what learners already know. Since intra-group members already possess some knowledge of their culture, the 5E Inquiry Model helps them revisit that knowledge from other angles and find new patterns and relationships.

Figure 1. 5E inquiry model (adapted from Bybee et al., Citation2006)

The 5E Inquiry model emphasises not only students’ hands-on knowledge acquisition and learning but also the role of instructors in facilitating this process. The role of teachers in the effective implementation of a telecollaborative project can hardly be overestimated. This is reflected in a widely cited definition of telecollaboration as “institutionalised, electronically mediated intercultural communication under the guidance of a lingua-cultural expert for the purposes of foreign language learning and the development of intercultural competence” (Belz & Kinginger, Citation2003, 2)

Even in the context of conventional telecollaborative projects in which a teacher’s active involvement in conducting online tasks is not necessary because learners typically interact entirely with their distant partners (O’Dowd, Citation2013, 6), there is considerable need for instructors’ indirect participation and regular guidance. Right from the early stages of the project, teachers are responsible for designing tasks, choosing tools, and establishing the rules of engagement and a timeframe for self-reflection and group feedback in order to enable productive collaboration and communication between two or more socio-linguistically and culturally distinct groups of learners (Lewis et al., Citation2011, 4). Because inquiry-based telecollaboration adds an additional layer to the design of an online exchange project, that is “intra-cultural inquiry” phase, explicit instruction becomes even more significant.

4. The aim of study and research questions

This study aims to explore the application of inquiry-based learning in nurturing learners’ intra-cultural awareness to enhance the quality of future intercultural telecollaboration. The research was designed to provide insights into issues that have lacked attention in the literature on telecollaboration and intra-cultural learning. Namely, this study is guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. What factors, conditions and processes are essential to intra-cultural telecollaboration?

RQ2. Are there significant differences between control and experimental groups in terms of students’ perceptions of most engaging and most difficult tasks during intra-cultural telecollaboration?

RQ3. Do students who complete conventional and inquiry-based telecollaborative tasks differ toward intra-cultural learning and is there a relationship between intra-cultural learning and the newly explored conditions (i.e., independent variables)?

RQ4. When the explored correlations are taken into consideration, how well do they predict learners’ intra-cultural learning in control and experimental groups?

RQ5. How well does intra-cultural learning predict learners’ confidence toward intercultural exchange in control and experimental groups?

5. Methods

5.1. Participants

This study adopted a convenience sampling method. The participants included in the final analysis were college freshmen attending a large public university in Japan. The experimental group (n = 56) consisted of two classes enrolled in the English presentation skills freshman online course, whereas the control group (n = 56) consisted of three classes enrolled in the same course. To follow the study’s protocol, all participants were Japanese; international students enrolled in the same course were excluded from the study. Female students (n = 21) represented 38% and male students (n = 35) represented 62% of the participants in the control group, whereas female students (n = 20) represented 36% and male students (n = 36) represented 64% of participants in the experimental group, respectively. All the students were taught by the same instructor, who had more than fourteen years of experience teaching university courses. To comply with the) Institutional Review Board recommendations, no sensitive or personal data were collected. Informed consent forms were distributed and returned electronically due to the social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students were explicitly informed of their rights to withdraw from the study at any time without providing the reasons.

5.2. Research design and procedures

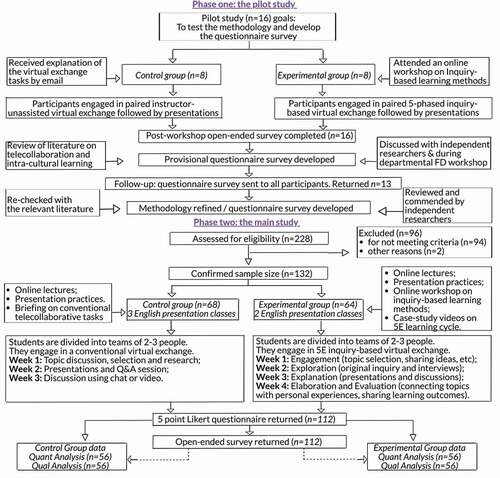

This research employed a classroom-based quasi-experimental design using mixed methods. It involved five intact undergraduate online classes assigned to the experimental condition (participating in a five-phase inquiry-based telecollaboration) and the control condition (participating in a conventional telecollaboration). According to Sato and Loewen (Citation2019) using a quasi-experimental design in a genuine classroom setting allows researchers to deploy interventions and observe participants without causing unnecessary disturbance. Prior to the experiment, the control group received a standard regimen of online lectures with presentation practice and partnered assignments. The experimental group received the same regimen as the control group in addition to receiving instructional videos and practice sessions using the 5E Inquiry model. Students in both groups were given the same reading material—a blogpost titled 13 Reasons Why Japan Is the World’s Most Unique Country—to help them explore, select, and research topics for their individual presentations. However, the students in the control group were not explicitly requested to conduct in-depth inquiries for their final presentations and telecollaborative discussions, whereas experimental group was required to carry out inquiries (such as surveys, interviews, field trips, etc.) in order to back their presentations with real-life data. In the latter’s case, 5E model of inquiry-based learning was applied. Another difference between control and experimental conditions was that the students in the control setting had only three weeks to complete their projects and presentations because there was no formal requirement for them to conduct fieldwork, and their presentations were based on conventional research methods using Internet and other digital sources. Also, the control group required less teacher facilitation, especially in the preparation phase, whereas experimental condition necessitated that more active teacher coordination for students seemed to have more questions about the objectives of each of the 5E phases. All activities in both control and experimental settings were conducted using the Microsoft Teams™ application. The research design is summarized in .

5.3. The pilot study and questionnaire development

Eight months prior to conducting the main study, the researcher had conducted a pilot study with the aim of testing the methodology, developing the instruments and exploring potential problems in the implementation of the study. Twelve undergraduate and four graduate students had volunteered to attend a half-day online workshop during which they were randomly assigned to control (n = 8) and experimental (n = 8) groups. None of these students were included in the main experiment. To replicate the conditions of the future study, all pilot study participants were Japanese. In addition, two experienced researchers agreed to observe the pilot study and independently review the methods and the instruments. The findings of the pilot survey along with the selected literature on telecollaboration and intra-cultural learning (Belz & Thorne, Citation2006; Byram, Citation1997; Guth & Helm, Citation2010; O’Dowd, Citation2012; O’Dowd & Waire, Citation2009) have been used to design a 68-item original instrument. Two independent researchers also reviewed the instrument and the methods and provided their comments. Comments have also been made during an international FD workshop at the researcher’s university entitled “The Prospects of Telecollaboration in Teaching Intercultural Communication”. Three weeks after the pilot study, its participants were contacted again with a request to complete the newly developed survey. Thirteen (81.3%) out of 16 participants completed and returned the survey. The discussion of survey responses among researchers resulted in modification of 17 items and deletion of 6 items from the final version of the questionnaire.

5.4. Data collection and analysis

5.4.1. Quantitative data

The primary instrument used in this study was a 62-item questionnaire survey, which along with binary and multiple-response questions also included fifty-one 5-point Likert scale questions. The survey questionnaire was distributed on the last day of the course using Microsoft Forms™ among 68 students in the control group and 64 students in the experimental group, respectively. Fifty-six students (82.3%) from control and 56 students (87.5%) from experimental groups returned the completed forms. Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM™). Detailed description of statistical methods used is described in the Results section.

5.4.2. Qualitative data

Along with the 62-item questionnaire, students have also completed an online open-ended survey, which included four prompts, as shown in appendix 3. The students’ responses were treated as qualitative data to explore additional factors. Researchers used MAXQDA Analytics Pro™ Ver.2020, a software program designed for computer-assisted qualitative and mixed method data analysis. Data were examined in line with the procedure for an inductive content analysis. Another independent researcher was hired to assist with the open coding. The two researchers worked independently to examine the students’ responses for recurring general themes and sub-themes. There have been 92 cases (out of 720) that involved a disagreement between researchers during open coding. The interrater reliability test resulted in 87.22% interrater agreement. McHugh (Citation2012) suggested that 80% agreement should be the minimum acceptable interrater agreement.

6. Results

6.1. RQ1. what factors, conditions and processes are essential to intra-cultural telecollaboration? (Exploratory Factor Analysis)

The fifty-one 5-point Likert scale questions in the survey were subjected to the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) using SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM™). Before conducting the PCA, the suitability of the questionnaire items for factor analysis was assessed. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was .74 which is higher than the generally recommended value of .6 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity reached statistical significance. Eight items that did not load were deleted, leaving 43 items for the PCA. The PCA of the remaining questionnaire items showed the existence of 14 components with eigenvalues exceeding 1, explaining 23.4%, 7.6%, 5.9%, 5.4%, 4.1%, 3.9%, 3.5%, 3.1%, 2.9%, 2.6%, 2.5%, 2.2%, 2.1% and 2.0% of the variance. The fourteen-component solution explained a total of 71.04% of the variance.

Following this procedure, a varimax rotation was conducted to assess the underlying structure for the 43 items of the questionnaire and assist in the interpretation of these components (see ). The first component, which seems to index (1) peer-collaboration, had high and moderately high loadings on the six items. The second component, which seemed to index (2) learner engagement, had strong and acceptable loadings on the five items. The third component, which indexed (3) learner demotivation, showed strong and acceptable loadings on six items and the fourth component, which seemed to index (4) intra-cultural learning, had strong loadings on four items. The remaining 10 components seemed to index (5) linguistic preference, (6) attitude toward online exchange, (7) formal academic interactions, (8) peer-questioning, (9) exploration through original inquiry, (10) communicating the inquiry findings, (11) time sufficiency, (12) confidence toward intercultural communication, (13) use of technology, and (14) elaborating on the inquiry findings, and had high and acceptable loadings on many items.

To assess whether the data from the variables in each component form reliable scales, Cronbach’s alphas were computed (see ). α scores of the four scales (e.g., Linguistic preferences, Attitude toward online exchange, and Exploration through original inquiry) have significantly improved after deleting certain items, whereas α scores of two components have slightly improved once some items were deleted. α scores of the four scales (i.e., Formal academic interactions α = .63, Communicating the inquiry findings α = .60, Time sufficiency α = .60, and Use of technology α = .55) did not show minimally adequate reliability, and thus, were omitted from the analysis. As a result of recomputing, Cronbach’s alpha was .86 for Peer-collaboration, .81 for Learner engagement, .74 for Learner motivation, .70 for Intra-cultural learning, .77 for Linguistic preference, .84 for Attitude toward online exchange, .77 for Peer-questioning, and .74 for Exploration through original inquiry, respectively. Ursachi et al. (Citation2015) suggested that α of .60-.70 indicates an acceptable level of reliability, whereas α of .80 or greater a good level of reliability. The results of the PCA and internal consistency reliability provided some support for validity of the instrument in this study. The analysis has also helped to explore a number of factors, processes and conditions that seem to play significant roles during intra-group telecollaboration, which were previously not reported in the literature. Descriptive statistics of variables list refined following the EFA and PCA are shown in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the refined list of variables following the exploratory factor analysis, principal component analysis, and internal consistency reliability test

6.2. RQ2. Are there significant differences between control and experimental groups in terms of students’ perceptions of most engaging and most difficult tasks during intra-cultural telecollaboration?

A two-tailed Mann-Whitney two-sample rank-sum test was conducted to examine whether there were significant differences between control and experimental groups in terms of students’ perceptions of most engaging and most difficult tasks during telecollaboration. The two-tailed Mann-Whitney two-sample rank-sum test is an alternative to the independent samples t-test but does not share the same assumptions (Conover & Iman, Citation1981). There were 56 observations in the control group and 56 observations in the experimental group. presents the result of the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 2. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test results

The result of the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test for the most engaging tasks during telecollaboration was not significant based on an alpha value of 0.05, U = 1456, z = −0.78, p = .437 (Watching my partners’ presentation), U = 1764, z = −1.32, p = .188 (Asking questions), and U = 1400, z = −1.14, p = .256 (Making my own presentation). Similarly, the result of the two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test for the most difficult tasks during telecollaboration was not significant based on an alpha value of 0.05, U = 1764, z = −1.32, p = .188 (Communicating in English), U = 1568, z = 0.00, p = 1.000 (Discussing topics via online chat), and U = 1568, z = 0.00, p = 1.000 (Using technology). This suggests that the distributions were not significantly different between the groups, further indicating that the use of inquiry-based learning methods during telecollaboration in experimental group did not have any significant effect on this group’s overall perception of the problems and opportunities in the learning environment compared to the control group.

6.3. RQ3. Do students who complete conventional and inquiry-based telecollaborative tasks differ toward intra-cultural learning and is there a relationship between intra-cultural learning and the explored conditions?

A two-tailed Mann-Whitney two-sample rank-sum test was conducted to examine whether there were significant differences in intra-cultural learning between control and experimental groups (see ).

Table 3. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test for intra-cultural learning between groups

The result of the test was not significant based on an alpha value of 0.05, U = 1456.5, z = −0.66, and p = .508. The mean rank for the control group was 54.51 and the mean rank for the experimental group was 58.49. This suggests that the distribution of intra-cultural learning for the control group (Mdn = 3.00) was not significantly different from the experimental group (Mdn = 3.33), further indicating that the students who completed conventional and inquiry-based telecollaborative tasks have reported similar levels of intra-cultural learning after telecollaboration.

A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted between intra-cultural learning and other variables in both control and experimental groups. Cohen’s standard was used to evaluate the strength of the relationships, where coefficients between .10 and .29 represent a small effect size, coefficients between .30 and .49 represent a moderate effect size, and coefficients above .50 indicate a large effect size (Cohen, Citation1988). A Pearson correlation requires that the relationship between each pair of variables is linear (Conover & Iman, Citation1981). This assumption is violated if there is curvature among the points on the scatterplot between any pair of variables.

The result of the correlations in the control group was examined using Holm corrections to adjust for multiple comparisons based on an alpha value of 0.05. A significant positive correlation was observed between peer-collaboration (PC) and intra-cultural learning (ICL) (rp = 0.38, p = .004, 95% CI [0.13, 0.59]). The correlation coefficient between PC and ICL was 0.38, indicating a moderate effect size. This correlation indicates that as PC increases, ICL tends to increase. A significant positive correlation was observed between learner engagement (LE) and ICL (rp = 0.45, p < .001, 95% CI [0.21, 0.64]). The correlation coefficient between LE and ICL was 0.45, indicating a moderate effect size. This correlation indicates that as LE increases, ICL tends to increase. A significant negative correlation was observed between learner demotivation (LD) and ICL (rp = −0.28, p = .035, 95% CI [−0.51, −0.02]). The correlation coefficient between LD and ICL was −0.28, indicating a small effect size. This correlation indicates that as LD increases, ICL tends to decrease. No other significant correlations were found. presents the results of the correlations in the control group.

Table 4. Pearson Correlation results between Intra-cultural learning (ICL) and eight independent variables in control group

The result of the correlations in experimental group was examined using Holm corrections to adjust for multiple comparisons based on an alpha value of 0.05. A significant positive correlation was observed between peer-collaboration (PC) and intra-cultural learning (ICL) (rp = 0.47, p < .001, 95% CI [0.24, 0.65]). The correlation coefficient between PC and ICL was 0.47, indicating a moderate effect size. This correlation indicates that as PC increases, ICL tends to increase. A significant positive correlation was observed between learner engagement (LE) and ICL (rp = 0.61, p < .001, 95% CI [0.41, 0.75]). The correlation coefficient between LE and ICL was 0.61, indicating a large effect size. This correlation indicates that as LE increases, ICL tends to increase. A significant negative correlation was observed between learner demotivation (LD) and ICL (rp = −0.38, p = .004, 95% CI [−0.58, −0.13]). The correlation coefficient between LD and ICL was −0.38, indicating a moderate effect size. This correlation indicates that as LD increases, ICL tends to decrease. A significant positive correlation was observed between attitude toward online exchange (ATOE) and ICL (rp = 0.33, p = .014, 95% CI [0.07, 0.54]). The correlation coefficient between ATOE and ICL was 0.33, indicating a moderate effect size. This correlation indicates that as ATOE increases, ICL tends to increase. A significant positive correlation was observed between exploration through original inquiry (ETOI) and ICL (rp = 0.42, p = .001, 95% CI [0.18, 0.62]). The correlation coefficient between ETOI and ICL was 0.42, indicating a moderate effect size. This correlation indicates that as ETOI increases, ICL tends to increase. No other significant correlations were found. presents the results of the correlations in the experimental group.

Table 5. Pearson Correlation results between Intra-cultural learning (ICL) and eight independent variables in experimental group

6.4. RQ4. When the explored correlations are taken into consideration, how well do they predict learners’ intra-cultural learning in control and experimental groups?

A linear regression analysis was conducted to assess whether correlated variables significantly predicted intra-cultural learning in control and experimental groups. The assumption of normality was assessed by plotting the quantiles of the model residuals against the quantiles of a Chi-square distribution, also called a Q-Q scatterplot (DeCarlo, Citation1997). For the assumption of normality to be met, the quantiles of the residuals must not strongly deviate from the theoretical quantiles. Homoscedasticity was evaluated by plotting the residuals against the predicted values (Bates et al., Citation2014; Field, Citation2017; Osborne & Waters, Citation2002). The assumption of homoscedasticity is met if the points appear randomly distributed with a mean of zero and no apparent curvature. Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) were calculated to detect the presence of multicollinearity between predictors. All predictors in the regression model have VIFs less than 5. To identify influential points, Studentized residuals were calculated, and the absolute values were plotted against the observation numbers (Field, Citation2017; Pituch & Stevens, Citation2015). An observation with a Studentized residual greater than 3.25 in absolute value, the 0.999 quantile of a t distribution with 55 degrees of freedom, was considered to have significant influence on the results of the model.

First, a linear regression analysis was conducted to assess whether peer-collaboration, learner engagement, and learner demotivation significantly predicted intra-cultural learning (ICL) in the control group. The results of the linear regression model were significant, F(3,52) = 6.04, p = .001, R2 = 0.26, indicating that approximately 26% of the variance in ICL is explainable by these three independent variables. Peer-collaboration did not significantly predict ICL, B = 0.18, t(52) = 1.57, p = .123. Learner engagement significantly predicted C4, B = 0.31, t(52) = 2.02, p = .049. This indicates that on average, a one-unit increase of learner engagement will increase the value of ICL by 0.31 units. Learner demotivation did not significantly predict ICL, B = −0.16, t(52) = −1.24, p = .219. summarizes the results of the regression model.

Table 6. Results for Linear Regression with selected independent variables predicting intra-cultural learning in control group

Following this, a linear regression analysis was conducted to assess whether peer-collaboration, learner engagement, learner demotivation, attitude toward online exchange, and exploration through original inquiry significantly predicted intra-cultural learning (ICL) in the experimental group. The results of the linear regression model were significant, F(5,50) = 7.71, p < .001, R2 = 0.44, indicating that approximately 44% of the variance in ICL is explainable by these five independent variables. Peer-collaboration did not significantly predict C4, B = 0.02, t(50) = 0.14, p = .887. Learner engagement significantly predicted ICL, B = 0.51, t(50) = 2.91, p = .005. This indicates that on average, a one-unit increase of learner engagement will increase the value of ICL by 0.51 units. Learner demotivation did not significantly predict C4, B = −0.22, t(50) = −1.79, p = .080. Similarly, students’ attitude toward online exchange and exploration through original inquiry did not significantly predict ICL. summarizes the results of the regression model.

Table 7. Results for Linear Regression with selected independent variables predicting intra-cultural learning in experimental group

Thus, the results suggest that learner engagement in both conventional and inquiry-based telecollaborative environments can predict the quality of intra-cultural learning, and yet in the inquiry-based learning environment, this prediction is statistically more robust.

6.5. RQ5. How well does intra-cultural learning predict learners’ confidence toward intercultural exchange in control and experimental groups?

A linear regression analysis was conducted to assess whether intra-cultural learning significantly predicted confidence toward intercultural communication (CTIC) in control and experimental groups. The results of the linear regression model for the control group were not significant, F(1,54) = 1.78, p = .188, R2 = 0.03, indicating that intra-cultural learning did not explain a significant proportion of variation in CTIC in the control group. Since the overall model was not significant, the individual predictors were not examined further. On the other hand, the results of the linear regression model for the experimental group were significant, F(1,54) = 7.90, p = .007, R2 = 0.13, indicating that approximately 13% of the variance in CTIC is explainable by intra-cultural learning. The latter significantly predicted CTIC, B = 0.55, t(54) = 2.81, p = .007. This indicates that on average, a one-unit increase of intra-cultural learning will increase the value of CTIC by 0.55 units. These results suggest that the quality of intra-cultural learning gained during the inquiry-based telecollaboration could predict students’ confidence toward potential intercultural exchange, whereas conventional telecollaboration failed to predict the latter. This further indicates that there must have been a qualitatively different factor during inquiry-based online exchanges (such as enhanced learner engagement, peer-collaboration and/or unique knowledge accumulation during 5E Inquiry phases) that positively affected students’ confidence toward potential intercultural exchange. summarizes the results of the regression model.

Table 8. Results for linear regression with intra-cultural learning predicting confidence toward intercultural communication

6.6. Qualitative results

By applying a combination of thematic and inductive content analyses, the study qualitatively analysed students’ responses from both control and experimental groups to the four open-ended questions (see appendix 3). A total of 112 students’ responses have been analysed (see appendix 4). Student responses in the control group produced 342 units of meaning, whereas student entries in the experimental group yielded 378 units of meaning. The research focused on examining the students’ entire experiences through control and experimental interventions by fragmenting them into thematic units and categories.

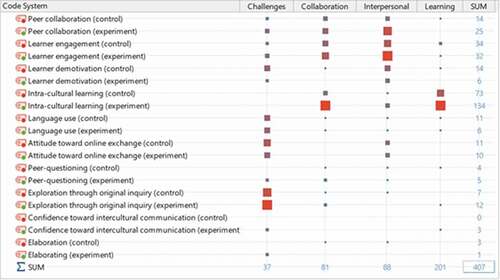

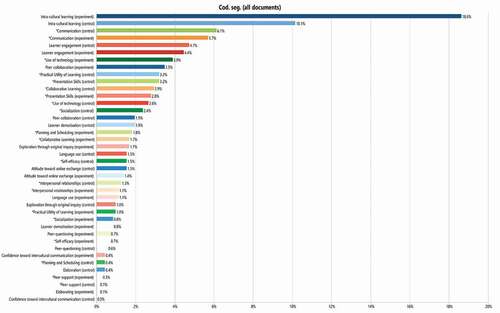

In the first stage of the analysis, the author assisted by another experienced researcher examined the students’ responses for recurring instances of a general nature, followed by a more systematic identification and grouping of such instances across the entire dataset through open coding. In the second stage, the codes related to each main theme were identified and grouped into categories. As a result of analysing 720 units of meaning in total, researchers identified two main categories of themes. The first category included 407 units of meaning (56.52%) that were related to the variables explored in the quantitative part of the study (e.g., peer-collaboration, learner-engagement, intra-cultural learning, language use, peer-questioning, exploration through original inquiries, etc.).

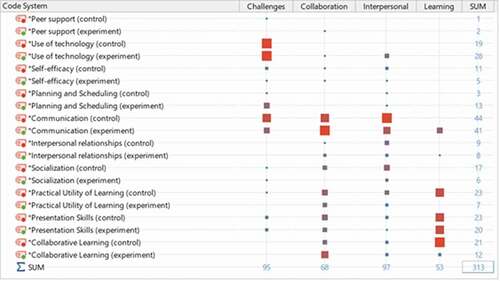

The second category of themes contained 313 units of meaning (43.48%) that were not explored in the final quantitative data but were nonetheless frequently mentioned by the students when responding to the open-ended questionnaire (e.g., peer-support, use of technology, self-efficacy issues, planning and scheduling challenges, presentation skills, communication issues, need for socialization, etc.). The recurrence of a broad set of issues revealed the complex nature of a telecollaborative exchange from both pedagogical, intra- and inter-cultural, technological, cognitive, affective, and socio-cultural perspectives (Avgousti, Citation2018; Bueno-Alastuey & Kleban, Citation2016; Godwin-Jones, Citation2020; Thomas & Yamazaki, Citation2021). Therefore, it is indeed important to apply mixed methods to gain more in-depth insights into students’ challenges and coping strategies when they engage in both inquiry and non-inquiry-based telecollaborative projects.

MAXQDA’s Code Matrix browser was used to visualize the frequency distribution of codes across all qualitative datasets. The matrices, as shown in , provide an overview of how many document segments have been assigned a specific code. A a general overview of code frequencies across groups and related themes is shown in .

The symbols at the conjunction points represent the number of segments that were coded with a specific code. The larger the symbol of a node, the more coded segments were assigned to the code in question. A brief overview of key findings is provided below.

Compared to the control group, the experimental group appeared to report more extensive and in-depth intra-cultural learning. The students in the latter group tended to provide more vivid and concrete examples of their learning experience.

Both groups seemed to have encountered challenges during different stages of intra-cultural telecollaboration. For example, the groups have similarly reported challenges related to the use of technology, communication (including interpersonal), and the exploration through original inquiry. Meanwhile, both groups have similarly reported significant improvement in presentation skills.

Students’ accounts of confidence toward intercultural communication were less evident from the analysed qualitative data.

Collaborative learning seems to have taken place with higher frequency in the control group than in the experimental group. This can indicate that students in the latter group were focused on exploring their topics independently through their original inquiries, whereas students in a conventional online exchange by default collaborated with their peers to achieve learning objectives.

7. Discussion and conclusion

7.1. Implications for telecollaboration/communication research

To date, the majority of telecollaborative exchange projects reported in the literature employed one of the three main categories of tasks, such as information exchange, comparison/analysis, and collaboration/product creation (O’Dowd & Waire, Citation2009). While the projected learning outcomes for each of these projects varied and ranged from the exchange of cultural information and the construct of “otherness” to deconstruction of stereotypes (Lewis & O’Dowd, Citation2016), none of these studies had explicitly proposed, developed or tested an inquiry-based framework for cultivating an in-depth intra-cultural knowledge to inform more effective online intercultural communication.

The closest attempt to study telecollaboration in an inquiry-based learning environment was made by O’Dowd (Citation2006) proposing an ethnographic inquiry model in developing learners’ “ability to take the others” perspective and see things through their eyes’ (p. 116). However, given that “it can be quite difficult for teachers to develop in learners a critical cultural awareness during the necessarily short duration of a telecollaborative exchange” (p. 115), O’Dowd has eventually conceded that incorporating such methods into the mainstream curriculum would likely to remain challenging, if not unfeasible (Lewis & O’Dowd, Citation2016, p. 57).

Partly in response to Lewis and O’Dowd (Citation2016), and partly in attempt to explore the notion of savoir apprendre/faire used by Byram (Citation1997) to designate the skills of discovery and interaction, including “an ability to acquire and operationalise new knowledge of cultural practices”, this study was designed to empirically test the use of inquiry-based learning during an intra-group telecollaboration and assess its effect on students’ intra-cultural awareness as well as impact on enhancing the quality of future intercultural communication. The key findings of the study and their broader implications are discussed below.

7.2. Intra-cultural learning and communication

Intra-cultural learning is an important prerequisite for implementing effective online exchanges to enhance learners’ intercultural communicative competence. Both quantitative and qualitative results of this study indicated that telecollaboration among the members of the same group had a positive impact on their intra-cultural learning. Intra-cultural learning appears to be a factor in both unassisted and instructed inquiry-based online exchanges. The examples of such learning are vividly described by students themselves.

‘Discussion with my partner was more interesting than thinking about culture by myself … For example, my partner asked me why Japanese way of greeting is bowing, not shaking hands. Thanks to the question, I could get new knowledge about bowing culture and share it with him’. SIC (S32, Control group)

‘I learned for the first time that Japanese food is an intangible cultural heritage of UNESCO, that octopus is not widely eaten outside of Japan, and that there is an arranged dish called matcha tempura. I was surprised at how much I didn’t know about the food in my own country’. SIC (S16, Experimental group)

Quantitative results have vividly suggested that despite similar levels of reported intra-cultural learning, students who engaged in a more reflective and exploratory research of their culture, have also reported stronger confidence in engaging in intercultural communication. Some qualitative data helped to illustrate it.

First, I learned the word “kawaii” is different from the word “cute”, I didn’t know that until I listened to her presentation. Second, what I learn is that there is hallo kitty café & museum in America. I feel like to go there someday because I like it. Third, I learned that kawaii culture is everywhere in Japan. From my partner’s presentation and my research I could learn lots of new information, if I travel to foreign countries I think I can easily share knowledge about Japan. SIC (S44, Experimental group)

These findings vividly illustrate the importance of intra-cultural knowledge construction, which is consistent with previous scholarship viewing intercultural competence as a by-product of knowledge, skills, and attitudes at the interface between several cultural areas, including the students’ own culture and a target culture (Byram, Citation1997; Risager, Citation2007). It is therefore important for teachers of online intercultural communication to explicitly use strategies aimed at fostering critical cultural awareness, in other words, help their students develop skills of critical evaluation of perspectives, practices, and products in one’s own and other cultures (Byram, Citation1997:53).

7.3. Inquiry-based learning and telecollaboration

This study concedes that the integration of inquiry-based learning framework into online intercultural exchanges, though previously lacked attention, is a promising field of research with its own unique pedagogic challenges.

The study’s protocol allowed students in the experimental group not only to engage in intra-cultural telecollaboration (such as in control group) but also attempt to discover new intra-cultural knowledge through their original inquiry, with the learners formulating hypotheses and testing them by conducting ethnographic experiments and/or making observations (Keselman, Citation2003; Pedaste et al., Citation2012). The following responses illustrate the experience of conducting an original inquiry.

My topic was about Shinto religion in Japan. I decided to go to the shrine to make my research more creative. Also, because I had a presentation partner, I was more motivated to do this. I was excited about the experience of actually going to shrines, learning something new about them, and then sharing my knowledge with my partner. Active research was fun for me. SIC (S4, Experimental group).

For my research of Japanese cuisine, I actually made ‘dashi’ [Japanese soup stock that is the backbone of many Japanese dishes]. When I was explaining the process of making dashi during my presentation, it was difficult to translate my impressions of the taste and their names into English (which are often unique to Japanese). So we tried to find proper English expressions. For example, we thought that the most appropriate description of the taste ‘maroyaka’ would be ‘mild’. SIC (S28, Experimental group).

One can observe that inquiry-based environment created authentic contexts and improves learning, which is consistent with research in cognitive psychology (Greeno et al., Citation1996). Authentic activities undertaken by students in experimental group provided them with the motivation to acquire new knowledge, an opportunity to incorporate it into their existing knowledge, and conditions in which to apply this knowledge in real life (Edelson et al., Citation1999). Such illustrations were not present in the control groups’ reflections. It is also fair to mention that according to the statistical analysis not many students in the experimental group had a positive attitude toward conducting their original inquiries. The qualitative data have provided some insights into this.

It was very difficult to make a presentation about kimono [a traditional Japanese garment] because there were many things about kimono that I did not know, even though they were familiar to my other classmates. It was a very time-consuming task to research and summarize unique knowledge about the kimono. SIC (S48, Experimental group).

Challenge I faced during the online activity was to research for my final presentation. I had to do a hands-on mini research about my chosen topic and find out something new, interesting and original for my presentation. So, I had to interview my high school friend who was familiar with my topic. SIC (S19, Experimental group).

Although studies supported the effectiveness of inquiry-based learning as an instructional approach (Alfieri et al., Citation2011; Furtak et al., Citation2012), research has also shown that guided inquiry-based learning can also be a challenge to unprepared students. Lewis and O’Dowd (Citation2016) highlighted the existence of “positive evidence suggesting that telecollaborative exchanges support learning, particularly when tasks are carefully designed to encourage focus on form and when online exchange is combined with offline reflection and study”. Instructors should therefore provide explicit scaffolding for developing students’ inquiry skills prior to the launch of a project, focusing specifically on identifying problems, formulating questions, collecting and analysing authentic information, and presenting results and conclusions (Mäeots et al., Citation2008).

7.4. Pedagogical implications

The findings of this quasi-experimental research are in line with previous studies that highlighted the need for a systematic pedagogical approach to the implementation of telecollaborative projects in higher education (Dooly & Masats, Citation2020; O’Dowd, Citation2013). Thus, what should the teachers do to promote inquiry-based intra-/intercultural telecollaboration? Based on the findings of this study, an effective classroom-based implementation of an inquiry-based virtual exchange (or any telecollaboration for that matter) requires teachers’ close attention to the following three sets of issues.

First, an effective inquiry-based telecollaborative project with focus on both intra- and intercultural learning should be well-planned and well-organized (Ismailov, Citation2021a; O’Dowd, Citation2013). Teachers should be trained to design the structure of an exchange with clear objectives, participation criteria, and language use and be based on the interests, L2 proficiency and level of digital literacy of both home and partner university students. These activities should also use various strategies to match learners within or from different institutions and implement motivational online assignments to create effective virtual teamwork and engaging collaborative environment (Ismailov, Citation2021b; Ismailov & Laurier, Citation2021; Ismailov & Ono, Citation2021). Also, teachers who conduct such telecollaborative exchanges should be aware of inquiry-based learning and action research methodologies to assist students to conduct and present their inquiries effectively.

Secondly, telecollaborative teachers implementing inquiry-based projects should be able to conduct effective in- and out-of-class instruction and facilitation (Dooly & O’Dowd, Citation2018). For example, students might need constant support when designing their original inquiries or when reflecting on culturally dynamic patterns of interaction in follow-up classroom discussions (Golubeva & Guntersdorfer, Citation2020). Also, students might need support in unpacking the results of their inquiries about their country’s culture and sociolinguistics.

Finally, teachers implementing an inquiry-based telecollaboration should be prepared to resolve not only instructional, cognitive, and socio-linguistic challenges when they arise but also the issues stemming from diverse levels of digital literacies among students participating in the exchanges (O’Dowd & Dooly, Citation2020). Therefore, teachers need to choose the appropriate technologies and digital tools to fit both the students’ everyday online practices and the telecollaborative project’s objectives (Vinagre & Corral, Citation2018). Also, teachers should be able to organise and structure real-time student interaction considering the specific affordances and technicalities of synchronous tools such as Zoom, Skype or Microsoft Teams.

7.5. Limitations and suggestions for future research

One of the main limitations of this study was that intra-group telecollaborative exchanges were limited to the exploration of cultural knowledge and they did not explicitly cover language learning (although evidence exists that some students had skilfully addressed both areas). Future studies could fill this gap by assessing linguistic aspects of learning during intra-group telecollaborative exchanges. Such studies might focus on corrective peer feedback, linguistic task design or language-oriented online discussions among members of the same culture. Another limitation was that the study focused exclusively on Japanese students. Future research should be conducted involving learners in other geographic settings. This would allow an in-depth analysis of the effect of other lingua-cultural environments on the quality of intra-cultural telecollaboration.

Finally, this research and related interventions took place during the coronavirus pandemic in Japan when the students were facing major socio-psychological, academic, and motivational obstacles, such as the lack of social interaction and face-to-face communication, cognitive overload necessitated by the need to attend numerous weekly online classes (Ismailov & Ono, Citation2021). Future studies should also be designed and implemented in the post-pandemic environment when both learners and educational institutions around the globe are free from the challenges of the pandemic time.

Code availability

Available upon request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Availability of data and material

Available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Murod Ismailov

Murod Ismailov, PhD, is an assistant professor of communication at the Centre for Education of Global Communication under the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Tsukuba, Japan. Also, he works as an Adjunct Lecturer at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies and the National Police Academy of Japan. His research focuses on learner-centered pedagogy, 4C skills development, e-learning, telecollaboration, and inquiry- and project-based learning. In addition, he is actively involved in numerous research projects and grants supported by the Japanese government addressing topics of intercultural communication, English Medium Instruction (EMI), and social capital/education in the post-Soviet countries. His most recent articles were published in Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, E-Learning and Digital Media, F1000 Research and other international peer-reviewed journals.

References

- Abrams, Z. (2003). The effects of synchronous and asynchronous CMC on oral performance. Modern Language Journal, 87(2), 157–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00184

- Alfieri, L., Brooks, P. J., Aldrich, N. J., & Tenenbaum, H. R. (2011). Does discovery-based instruction enhance learning? Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021017

- Alred, G., Byram, M., & Fleming, M. (eds). (2003). Intercultural Experience and Education. Multilingual Matters.

- Avgousti, M. I. (2018). Intercultural communicative competence and online exchanges: A systematic review. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(8), 819–853. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1455713

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2014). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4: ArXiv preprint arXiv, Journal of Statistical Software. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.io1 https://arxiv.org/abs/1406.5823

- Belz, J., & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Introduction. In J. A. Belz & S. L. Thorne (Eds.), Internet-mediated Intercultural Foreign Language Education (pp. 207–246). Thomson Heinle.

- Belz, J., & Kinginger, C. (2003). Discourse options and the development of pragmatic competence by classroom learners of German: The case of address forms. Language Learning, 53(4), 591–647. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9922.2003.00238.x

- Bueno-Alastuey, M. C., & Kleban, M. (2016). Matching linguistic and pedagogical objectives in a telecollaboration project: A case study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(1), 148–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.904360

- Bybee, R., Taylor, J. A., Gardner, A., Van Scotter, P., Carlson Powell, J., Westbrook, A., & Landes, N. (2006). The BSCS 5E Instructional Model: Origins and effectiveness. BSCS, Colorado Springs, CO.

- Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Multilingual Matters.

- Chaney, D. C. (2001). From Ways of Life to Lifestyle: Rethinking culture as ideology and sensibility. In L. James (Ed.), Culture in the Communication Age (pp. 75–88). Routledge.

- Çiftçi, E. Y. (2016). A review of research on intercultural learning through computer-based digital technologies. Educational Technology & Society, 19(2), 313–327.

- Çiftçi, E., & Savaş, P. (2018). The role of telecollaboration in language and intercultural learning: A synthesis of studies published between 2010 and 2015. ReCALL, 30(3), 278–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344017000313

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavior sciences (2nd ed.). West Publishing Company.

- Collier, M. J., Ribeau, S. A., & Hecht, M. L. (1986). Intracultural communication rules and outcomes within three domestic cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10(4), 439–457. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(86)90044-1

- Conover, W. J., & Iman, R. L. (1981). Rank transformations as a bridge between parametric and nonparametric statistics. The American Statistician, 35(3), 124–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1981.10479327

- Corbett, J. (2003). An Intercultural Approach to English Language Teaching. Multilingual Matters.

- Cormode, G., & Krishnamurthy, B. (2008). Key differences between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0. First Monday, 13(6). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v13i6.2125

- Crawford-Lange, L. M., & Lange, D. (1987). Integrating language and culture: How to do it. Theory into Practice, 26(4), 258–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00405848709543284

- Cunningham, D. J. (2016). Request modification in synchronous computer-mediated communication: The role of focused instruction. The Modern Language Journal, 100(2), 484–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12332

- DeCarlo, L. T. (1997). On the meaning and use of kurtosis. Psychological Methods, 2(3), 292–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.2.3.292

- Dooly, M. (2017). Telecollaboration. In A. C. Chappele & S. Sh (Eds.), The Handbook of Technology and Second Language Teaching and Learning (pp. 169–183). John Willey & Sons, Inc.

- Dooly, M., & O’Dowd, R. (2018). Telecollaboration in the foreign language classroom: A review of its origins and its application to language teaching practices. In M. Dooly & R. O’Dowd (Eds.), In this together: Teachers’ experiences with transnational, telecollaborative language learning projects (pp. 11–34). Peter Lang.

- Dooly, M., & Masats, D. (2020). ‘What do you zinc about the project?’: Examples of technology-enhanced project-based language learning. In G. Beckett & T. Slater (Eds.), Global perspectives on project-based language learning, teaching, and assessment: Key approaches, Technology Tools, and Frameworks (pp. 126–145). Routledge.

- Dussias, P. E. (2006). Morphological development in Spanish-American telecollaboration. In J. A. Belz & S. L. Thorne (Eds.), Internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education (pp. 121–146). Thomson Heinle.

- Edelson, D., Gordin, D., & Pea, R. (1999). Addressing the challenge of inquiry-based learning through technology and curriculum design. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 8, 391–450.

- Field, A. (2017). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: North American edition. Sage Publications.

- Furstenberg, G., & Levet, S. (2010). Integrating Telecollaboration into the Language Classroom: Some Insights. In S. Guth & F. Helm (Eds.), Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, Literacies and Intercultural Learning in the 21st Century (pp. 305–336). Peter Lang.

- Furtak, E. M., Seidel, T., Iverson, H., & Briggs, D. C. (2012). Experimental and quasi-experimental studies of inquiry-based science teaching. Review of Educational Research, 82(3), 300–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312457206

- Godwin-Jones, R. (2019). Telecollaboration as an approach to developing intercultural communication competence. Language Learning & Technology, 23(3), 8–28. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44691

- Godwin-Jones, R. (2020). Building the porous classroom: An expanded model for blended language learning. Language Learning & Technology, 24(3), 1–18. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44731

- Golubeva, I., & Guntersdorfer, I. (2020). Addressing empathy in intercultural virtual exchange: A preliminary framework. In M. Hauck & A. Müller-Hartmann (Eds.), Virtual exchange and 21st century teacher education: short papers from the 2019 EVALUATE conference (pp. 117–126). Dublin: Research-publishing.net.

- Greeno, J., Collins, A., & Resnick, L. B. (1996). Cognition and learning. In R. Calfee & D. Berliner (Eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology (pp. 15–46). New York: Macmillan.

- Guth, S., & Helm, F. (2010). Introduction. In S. Guth & F. Helm (Eds.), Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, Literacies and Intercultural Learning in the 21st Century (pp. 13–35). Peter Lang.

- House, J. (2003). Misunderstanding in intercultural university encounters. In J. House, G. Kasper, & S. Ross (Eds.), Misunderstanding in Social Life: Discourse Approaches to Problematic Talk (pp. 22–56). Longman.

- Ismailov, M. (2021a). Conceptualizing an inquiry-based lingua-cultural learning through telecollaborative exchanges. F1000Research, 10, 677. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.55128.2

- Ismailov, M. (2021b). “Designing motivating online assignments and telecollaborative tasks in the time of a pandemic: Evidence from a post-course survey study in Japan.” In E. Langran & L. Archambault (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 600–609). Waynesville: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14390888.v1

- Ismailov, M., & Laurier, J. (2021). We are in “the breakout room.” Now what? An e-portfolio study of virtual team processes involving undergraduate online learners. E-Learning and Digital Media, 204275302110397. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/20427530211039710

- Ismailov, M., & Ono, Y. (2021). Assignment Design and its Effects on Japanese College Freshmen’s Motivation in L2 Emergency Online Courses: A Qualitative Study. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00569-7

- Kecskes, I. (2008). Dueling context: A dynamic model of meaning. Journal of Pragmatics, 40(3), 385–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.12.004

- Kecskes, I. (2012). Interculturality and intercultural pragmatics. In J. Jackson (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication (pp. 67–84)). Routledge.

- Kern, R. (2006). Perspectives on technology in learning and teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 183–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/40264516

- Keselman, A. (2003). Supporting inquiry learning by promoting normative understanding of multivariable causality. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 40(9), 898–921. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.10115

- Kim, E., & Brown, L. (2014). Negotiating pragmatic competence in computer mediated communication: The case of Korean address terms. CALICO Journal, 31(3), 264–284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11139/cj.31.3.264-284

- Lee, L. (2002). Enhancing learners’ communication skills through synchronous electronic interaction and task-based instruction. Foreign Language Annals, 35(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2002.tb01829.x

- Lewis, T., & O’Dowd, R. (2016). Online intercultural exchange and foreign language learning: A systematic review. In R. O’Dowd & T. Lewis (Eds.), Online intercultural exchange: Policy, pedagogy, practice (pp. 21–68). Routledge.

- Lewis, T., Chanier, T., & Youngs, B. (2011). Special issue commentary. Language Learning & Technology, 15(1), 3–9.

- Liaw, M.-L., & Master, B.-L. (2010). Understanding telecollaboration through an analysis of intercultural discourse. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220903467301

- Mäeots, M., Pedaste, M., & Sarapuu, T. (2008) Transforming students’ inquiry skills with computer-based simulations. 8th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, 1–5 July, Santander: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic (22, 276–282). Biochemia Medica.

- Mughan, T. (1999). Intercultural competence for language students in higher education. Language Learning Journal, 20(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09571739985200281

- O’Dowd, R. (2006). The use of videoconferencing and e-mail as mediators of intercultural student ethnography. In J. A. Belz & S. Thorne (Eds.), Internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education (pp. 86–120). Heinle and Heinle.

- O’Dowd, R. (2012). Intercultural communicative competence through telecollaboration. In J. Jackson (Ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Intercultural Communication (pp. 340–356). Routledge.

- O’Dowd, R. (2013). The Competences of the Telecollaborative Teacher. The Language Learning Journal, 43(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2013.853374

- O’Dowd, R., & Dooly, M. (2020). Intercultural communicative competence through telecollaboration and virtual exchange. In J. Jackson (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of language and intercultural communication (2nd ed., pp. 361–375). Routledge.

- O’Dowd, R., & Waire, P. (2009). Critical issues in telecollaborative task design. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220902778369

- Osborne, J., & Waters, E. (2002). Four assumptions of multiple regression that researchers should always test. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 8(2), 1–9.

- Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Leijen, Ä., & Sarapuu, S. (2012). Improving students’ inquiry skills through reflection and self-regulation scaffolds. Technology, Instruction, Cognition and Learning, 9, 81–95.

- Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siimana, L. A., de Jong, T., van Riesen, S., Kamp, E. T., Manoli, C. C., Zacharia, Z. C., & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003

- Pinker, S. (1999). How the mind works. W.W. Norton.

- Pituch, K. A., & Stevens, J. P. (2015). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (6th ed.). Routledge Academic. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315814919

- Risager, K. (2007). Language and Culture Pedagogy: From a National to a Transnational Paradigm. Multilingual Matters.

- Samovar, L., & Porter, R. (2001). Communication Between Cultures. Thomson Learning.

- Sato, M., & Loewen, S. (Eds.). (2019). Evidence-Based Second Language Pedagogy: A Collection of Instructed Second Language Acquisition Studies (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351190558

- Silverman, D. (2005). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. Sage Publications.

- Su, Y. (2018). Assessing Taiwanese college students’ intercultural sensitivity, EFL interests, attitudes toward native English speakers, ethnocentrism, and their interrelation. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0380-7

- Thomas, M., & Yamazaki, K. (2021). Project-based language learning and CALL. From virtual exchange to social justice. Equinox.

- Thorne, S. L. (2010). The ‘Intercultural Turn’ and Language Learning in the Crucible of New Media. In S. Guth & F. Helm (Eds.), Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, Literacies and Intercultural Learning in the 21st Century (pp. 139–164). Peter Lang.

- Ursachi, G., Horodnic, I. A., & Zait, A. (2015). How Reliable are Measurement Scales? External Factors with Indirect Influence on Reliability Estimators. Procedia. Economics and Finance, 20, 679–686. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00123-9

- Vinagre, M., & Corral, A. (2018). Evaluative language for rapport building in virtual collaboration: An analysis of Appraisal in computer-mediated interaction. Journal of Language and Intercultural Communication, 18(3), 335–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2017.1378227

- White, B., & Frederiksen, J. R. (1998). Inquiry, modelling, and metacognition: Making science accessible to all students. Cognition and Instruction, 16(1), 3–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci1601_2

- Yeh, H.-C., Tseng, -S.-S., & Heng, L. (2020). Enhancing EFL students’ intracultural learning through virtual reality. Interactive Learning Environments. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.17346251-10

Appendix

Table A1. Factor Loadings for the Rotated Factors

Appendix 2

Table A2. Factor structure and internal consistency reliability of questionnaire items

Appendix 3

Open-ended questionnaire prompts (qualitative data)

In at least 50 words, describe collaboration with your partner.

In at least 50 words. describe challenges you faced during the online exchange.

In at least 50 words. describe interpersonal relationships during the online exchange.

In at least 50 words. describe three things you have learned from your partner’s presentation and during the chat discussion.