Abstract

In recent years, cyberbullying on social media sites has increased among adolescents and even adults. While there are many factors and forms of cyberbullying, schoolchildren are vulnerable groups that are exposed to cyberbullying threats to their mental and emotional health. On the other hand, teachers have the responsibility in the place of the parent while at school, and they need to manage the issue at bay. This study focuses on the identification and analysis of teachers’ advice about cyberbullying, thus leading to the conceptualization of a decision-making model for the school to guide other teachers on this matter. This study is an explorative case study conducted in a prominent, semi-private international school in Lingyi, Shandong Province, China. With the purposive sampling approach, thirty-two teachers volunteered in this study; to recap and describe their encounters through writing in an online survey form. As analysis, their responses were validated for trustworthiness, while codes are checked through member checking, and eventually thematically analyzed to address the research questions. Findings from this study revealed a list of tactics that were categorized into three themes: (a) Preventive measures; (b) Counter-measures, and (c) Corrective measures. Each of these categories highlights specific ways that teachers suggest their students to when confronted with cyberbullying. Thereafter, each category was integrated as a model of decision-making in cyberbullying for improvements to the standard operating protocol of the researched school. In addition, this study proposes more similar research in other school settings so that more advisory tactics can be accumulated to enable education policymakers, school administrators, and teachers to make better decisions to manage issues associated with cyberbullying.

1. Introduction

Social networking sites can cause a lot of anxiety and frustration to people who are victims of cyberbullying (Lu et al., Citation2022). Since President Xi Jinping of China announced a 1-billion-yuan (USD 161 million) campaign in April to help children avoid cyberbullies, the country’s national propaganda department is using its power to urge parents and teachers to watch for bullying and report it if they witness it (Chan et al., Citation2021; Zimbardo, Citation2004). In terms of statistics, more than 100 million internet posts are made in China every day, with around 45 percent of them including health-related information. Most of the time, personal difficulties are associated with issues of mental health (Ge et al., Citation2015).

Recently identified as one of the causes of mental health, Chinese authorities are battling against an epidemic of internet bullying (Zhu et al., Citation2021). The government has asked schools to assist in the fight against cyberbullying, which they call a national disease (Li, Citation2020; Wang, Citation2021). In July 2017, the country’s education ministry declared that all primary and secondary schools would engage in programs aimed at raising awareness about the risks of bullying and educating youths on how to respond when confronted with an unpleasant circumstance. (Stevens et al., Citation2000). Since the 1990s, social media has grown rapidly as a new platform for cyberbullying among children and adolescents (Han et al., Citation2021). In recent times, even adults are now getting into the mix by posting hurtful comments on forums and discussion boards as they seek power or dominance over others (Peng et al., Citation2019). As this study focuses on the phenomenon of social bullying, researchers need to investigate the phenomenon in the context of China’s social media sites, as many lessons could be learned from teachers’ perspectives who have advised students or victims of cyberbullying. Their opinions matter as educators, as this provides an alternative view besides parents who may not be aware of what their children are facing in cyberspace (López-Castro & Priegue, Citation2019).

2. Background

Cyberbullying was first coined by Bill Belsey, a Canadian educator (Belsey, Citation2005). According to scholars, cyberbullying is defined as the act of harassing or threatening others through electronic means, particularly over social media sites like Facebook or Twitter, but can include texts and any other form of online contact such as emailing offensive images (Ansary, Citation2020; Peter & Petermann, Citation2018). Social media and its apps have progressively permeated people’s daily lives because of the broad adoption of mobile devices and have become a vital source of information for interpersonal interactions (Hall, Citation2020). Its quick development and invention transformed the way people communicated quietly and built and enriched a social and cultural form and even profoundly influenced a country’s political operation mode and citizens’ political engagement (Gong et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the extensive use of mobile media and social media has influenced personal identity in a variety of communication activities, including visual communication, and has resulted in issues such as generational inequalities and usage gaps across user groups (S. C. Chen & Lin, Citation2019; V. W. Xu, Citation2022).

On the other hand, the social media landscape in China is very different from the regions of southeast Asia (Bian & Ikeda, Citation2018). China’s social media operates under laws, which consider that information can come to light, and it is not uncommon for Chinese internet users to be detained for posting content on social media that the government deems objectionable (Chen, Citation2021; Yang, Citation2022). As a result, Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and YouTube, among other sites, are prohibited in China not only for security reasons but also for undesirable information that is inappropriate for their residents (Pan, Citation2017). However, China has its versions of social media sites such as include Sina Weibo, Toutiao, QQ, Tencent News, WeChat, and more (Jiang & Fu, Citation2018). China has developed an impressive range of social media platforms with which it can communicate within and with the world (Cui et al., Citation2018). Although these technologies work under China’s platforms, this does not shield users away from cyberbullies (Lyu, Citation2022; Zhang, Citation2021). In other words, cyberbullying knows no boundaries or platforms as it affects people through invasion of privacy, mental and psychological disturbance, and emotional trauma (Huang et al., Citation2021). When it comes to the phenomenon of cyberbullying, many countries around the world have legislation that deals with cyberbullying, but it is still very much in its infancy in Asia. The Chinese government has recently taken steps to address the problem, as well as to offer parents the tools they need to assist their children to stay secure online. (Junke, Citation2020; Marczak & Coyne, Citation2010).

On the other hand, many factors are causing cyberbullying to become such a serious issue in China (Li & Hesketh, Citation2021). These include the high percentage of mobile phone ownership and Internet dominance, as well as the offline nature of most of the Chinese culture and social life, where contact between acquaintances and friends is more encouraged than contact between strangers. (Patchin & Hinduja, Citation2006). Where cyberbullying begins is a difficult question to answer, but generally, it is most likely an indirect result of bullying behavior (Li & Hesketh, Citation2021; Y. Xu, Citation2021). Cyberbullies may also be bullied themselves and thus have a very weak sense of self-esteem, making them anxious to lash out at others who they believe have mistreated them in a certain way (Q. Chen & Zhu, Citation2022).

3. Problem Statement

Cyberbullying is any form of bullying which occurs online that is in abundant forms and platforms today (Y. Xu, Citation2021).). Students could be downcast in the classrooms from the effects of cyberbullying from social media, and teachers are the front-liners to detect cases in their day-to-day interactions with them (V. W. Xu, Citation2022; Wang, Citation2021). In the realm of social media, this can include things like sending mean messages, threatening someone’s well-being, or distributing hurtful comments. Cyberbullying can often cause long-lasting emotional and psychological damage to a victim both physically and mentally (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2022; Zhou, Citation2021). On the other hand, teachers are in-loco parents of their students, a Latin word for “in the place of a parent. This term refers to the legal responsibility of a teacher as a substitute parent for the child while at school (Mohammed et al., Citation2014). As such, it is speculated that teachers will likely encounter students who are victims of cyberbullying in their line of work and may also provide their life experiences as stories to tell in this study (Tate, Citation2017). Possibly, teachers in China could provide another perspective to describe cyberbullying cases that may not be known by the student’s parents and is particularly useful for the scholarly base (Rao et al., Citation2019). Many victims of cyberbullying are not expressed through verbal means, but rather, through non-verbal signals such as social withdrawals, mental health issues, anxiety, and low self-esteem (Symons et al., Citation2021). As such, this provides the opportunity for this study to investigate this phenomenon from their advisory perspectives, and ultimately suggest decision-making for teachers in the researched school.

4. Purpose of Study

This study proposes the need to explore teachers’ perspectives on cyberbullying. Relying on their life experience, the objectives are to describe the phenomenon from their encounters, gather relevant advice that is deemed practical to address the problem, and suggest an integrative framework that could be used for teachers to educate, correct, and prevent these cases from escalating in their respective contexts. As such, two research objectives are listed as follows:

To gather teachers’ advice for their students on how to address cyberbullying in the researched school.

To suggest a decision-making model based on teachers’ advice to manage cyberbullying problems in the researched school.

Alternatively, the corresponding research questions are listed in this study:

How do teachers in the researched school advise their students on cyberbullying?

What is the decision-making model that can be conceptualized based on teachers’ advice to manage cyberbullying?

5. Methodology

The research design is using an explorative case study with a qualitative approach. This type of research is usually used in social sciences research (Houghton et al., Citation2015). It involves the use of data from interviews, questionnaires, or observations to identify the reality of how things are for people, as well as what problems they might have (Merriam, Citation1988). In this study, the selected school is a prominent semi-private school located in the city of Linyi, Shandong Province in China. There are approximately 6000 students with 410 teachers in the school. This school is selected due to the consent from the chairman and school management board to conduct research, and there is various contextual uniqueness to its establishment. First, it is an experimental middle school facilitated by one of the top universities in China, and it has a fair number of teacher respondents who have stepped forward to assist in this study. Secondly, these teacher respondents self-volunteered upon the invitation to participate, and they have somehow fulfilled the purposive sample criteria (Suen et al., Citation2014) to at least encounter students who were victims of cyberbullying monthly. As this study focuses on the teacher’s lived experience, thirty-two teachers eventually responded to this study. This constitutes about ten percent of the total population of teachers in the school.

In terms of instrumentation, the researchers used an online survey service provider (White et al., Citation2001), and developed the researcher with the central open-ended question; “What was your best advice given to the student victims of cyberbullying?” In a box, teachers were able to type as much as they want to describe their student’s encounters, followed by the advice given to them. Their transcripts were captured in a spreadsheet, before being transferred to a primary document for analysis (Bailey, Citation2008). The other questions contained in the online survey question consist of their demographic backgrounds and other questions about a larger part of the study (with other research objectives). As far as this article is concerned, the data that is extracted is only concerning the advice given to the students to address the first research question with ATLAS.ti software to produce the result from thematic analysis (Friese, Citation2019). For the second research question, the codes were used to conceptualize a decision-making tree using the ATLAS.ti software through network analysis (Friese, Citation2019).

In terms of reliability and validity of the online questionnaire and the responses from the teachers, the language was translated from Chinese to English by one language teacher and then translated back to Chinese by another language expert (Sperber et al., Citation1994). The final version of the two-process translation was compared with the original version to ensure that there is no distortion of meaning and context by the researchers (Yu et al., Citation2004). For its data, the final transcript was compiled into one document for further analysis (Maneesriwongul & Dixon, Citation2004). In terms of data management, the document is uploaded into ATLAS. ti software and coded by the researchers. In addition, the respondents were labeled as P1, P2, P3, etc, indicating Participant Teacher 1, Participant Teacher 2, and so forth. Thereafter, the codes were assigned to each of the responses, resulting in a list of codes to be thematically analyzed to address the research questions. There is also the process of intercoder reliability (using kappa analysis) by three independent coders to check the consistency of the coding process, and the agreement between all three coders yields an above 60% acceptance rate. This meant that the codes are agreeable between the three independent coders and that there is no major distortion from the verbal meanings and context of the transcripts (Burla et al., Citation2008).

6. Findings

In this section, the findings from this study will be presented in sequence, starting from the first research question. Under each of the figures provided, a summary will be presented to aid readers to understand the overall themes that emerged from the analysis of codes. For each code, a quotation will also be provided to support the code, followed by the source and reference line in ATLAS.ti. Thereafter, the second research question will also be presented and answered accordingly to its purpose.

Research question 1: How do teachers in the researched school advise their students on cyberbullying?

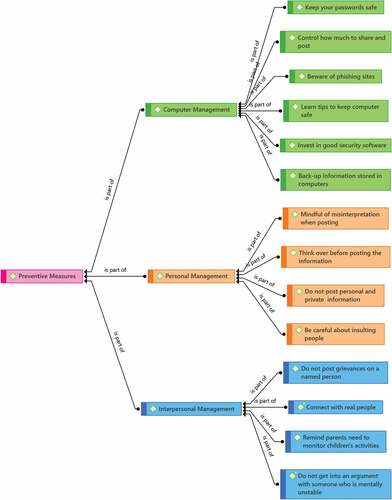

Preventing cyberbullying is a difficult task since it is hard to predict who might become a victim. The teacher respondents have mentioned three key areas to manage when it comes to managing cyber bullies. These three areas are listed under three themes: (a) Preventive measures; (b) Counter-measures, and (c) Corrective measures. Each of the themes will be explained separately according to Figure , Figure , and Figure respectively.

Figure shows the network view of preventive measures of teachers as advice for their students. These measures are clustered into three sub-themes: (a) computer management; (b) personal management; and (c) interpersonal management. For computer management, the teachers highlighted the need for more stringent use of passwords, and to limit the information one share on social media.

As Teacher 16 and Teacher 2 highlighted,

You shouldn’t put all of your passwords in a single location for the same reason that you shouldn’t keep all of your money in a single location. For instance, if you have accounts on several different sites, you should take the time to create a unique password for each of those accounts. Because of this, you won’t be required to keep reusing the same passwords over and over again.

Participant teacher 16, Line 62, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Don’t spend too much time on your pictures and status updates. One thing that many people don’t realize about social media is that it’s all about connections, not just pictures, and videos. If something important happens to you, like getting sick or having a problem at home, you might want to tell your friends and family. You could also post something online for other people to read. Remember that a lot of people will be looking at your pictures and updates no matter what you do. The same goes for photos and videos of your friends and loved ones.

Participant teacher 2, Line 49, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Preventive measures mean any reasonable measures taken by any person in response to an incident, to prevent, minimize, or mitigate loss or damage resulting from cyberbullying. As shown in the transcripts, teachers have also cautioned their students to be aware of phishing sites. This is to keep their computers safe from potential hackers and to invest in good security software to prevent cyberbullies from infringing their personal information. As mentioned by Teacher 11, Teacher 12, and Teacher 14 respectively,

Cyberbullies may have access to personal information such as an address or phone number when they target you online. If they’re searching for someone from the same school or area, they could also know some personal data about you and your family. Alter your search habits or delete all records of previous queries if you are concerned about your privacy being invaded.

Participant teacher 11, Line 58, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

“A lot of people are familiar with the safety tips that apply to cars and homes, but sometimes these things get forgotten when computers are involved.”

Participant teacher 12, Line 59, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Installing software that checks your system for anything out of the norm is the best method to keep your computer secure. There are several of these on the market, but some of the more effective ones are updated daily, so they are often targeted by cyber bullies.

Participant teacher 14, Line 61, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

To safeguard personal information from being leaked and exposed to cyber bullies, Teacher 13 provided this advice to her students,

We’ve all had the experience of misplacing items in our own houses. One of the most popular computer-related inquiries is ‘Where is my backup?’ You must maintain all of your vital data backed up so that you are not forced to restore anything if anything occurs to your computer. Most people save backups on a USB drive, but if you create frequent copies of your papers, retain them as well.

Participant teacher 13, Line 60, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

For the second theme of preventive measures -personal management, the teachers provided valuable input on how to safeguard their students’ well-being from cyberbullying. As shown in Figure above, some of these inputs include being mindful of other people’s misinterpretation if they were to post something, thinking over carefully before posting on social media, and being aware of the consequences of insulting others. As Teacher 3, Teacher 4, and Teacher 27 highlighted respectively,

Consider carefully the messages you send to others, particularly if it’s simply for fun or if the folks on the other end are unknown to you. The simplest approach to avoid being attacked online is to consider things to say before sharing them. Be careful when transmitting communications that might be readily misunderstood by others. When you’re not sure if anything is offensive, don’t publish it.

Participant teacher 3, Line 50, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Posting videos and photos of yourself might be a great way to share your day with a large number of people, but the more information you publish about yourself, the more difficult it will be to keep your identity secure from cyberbullies and other predators. While displaying photos allows relatives and friends to get to know you better, avoid focusing too much on your personal life. Include some information about your life, but avoid specifics that may make it simpler for someone else to profile you.

Participant teacher 4, Line 51, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

If you insult someone and it gets out, it could cost you your friends, your job, and even worse–your freedom

Participant teacher 27, Line 74, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

For the third theme of preventive measures, the teachers spoke about the importance of interpersonal management. In this aspect, Teacher 27 advised students to not post grievances against another named individual on social media as this would invite unnecessary attention and comments from strangers.

Do not post the names of any of your family, relatives, or close ones to see. If it’s something you wouldn’t want strangers to about, don’t post it in the first place

Participant teacher 5, Line 52, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Teacher 1 also highlighted the need to connect with real people on social media and not under any anonymous profiles.

Knowing who you’re chatting with is the greatest method to defend yourself against cyber bullies. The more individuals you keep track of, the more prepared you will be if you ever need their assistance.

Participant teacher 1, Line 48, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

In addition, Teacher 8 mentioned that there is a need for teachers to remind parents to monitor their children’s screen time activities on social media, while Teacher 19 highlights the need to avoid meeting people who may be mentally unstable.

One of the most serious issues individuals face online is that parents do not sufficiently supervise their children’s activities. Because children and teenagers often utilize social services to remain in contact with their peers, parents must ensure that their children maintain open channels of communication. Monitoring what your children do on these sites may help you guarantee that their digital lives are secure.

Participant teacher 8, Line 56, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Cyberbullies are all too happy to spread information gathered via snooping to everyone they know to generate rumors and cause issues (i.e., doxing). This may be quite troublesome, particularly if your work is dependent on your reputation.

Participant teacher 19, Line 67, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

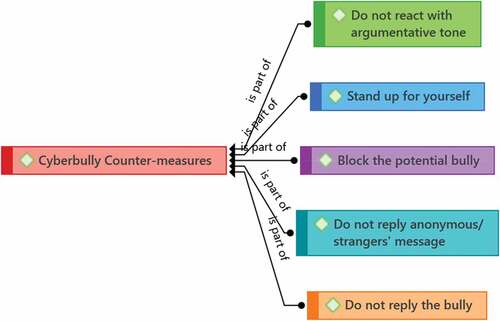

The next section will describe the findings analyzed from teachers’ advice on how to countermeasure a cyber bully. Countermeasure refers to the actions taken to counteract a danger or threat of cyberbullying. This theme is formed to capture what teachers said to their students if they were faced with cyberbullying. Figure is a network view presenting five key ideas.

First, there is a need to not react with an argumentative tone. As Teacher 18 mentioned,

Do not dispute with someone or threaten them with violence or bodily harm. You might be in jail for doing so, and if the threat comes true, the person you threatened could sue you for their injuries.

Participant teacher 18, Line 66, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Teacher 30 added the need to stand up against any attempts to bully,

If cyberbullies are making life difficult for you and your pals, speak up for yourself by discussing the issue with your parents or another adult on your side. People will usually back off and leave you alone if you stick up for yourself.

Participant teacher 30, Line 78, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

There is also a need to block the person involved in the cyberbullying as mentioned by Teacher 9, and to stay non-responsive as highlighted by Teacher 7 subsequently.

Instead of reacting to any messages you may get from someone who is bullying you, report the message and ban the sender. And, if they do get past your barriers and reply, don’t answer back. This will just give them what they want, and your efforts will be in vain.

Participant teacher 9, Line 57, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

If you get a communication from someone in another country, be mindful that they may not be who they seem to be. If you’re conversing with someone from school and you don’t remember seeing them in class, it’s generally better to maintain your distance or not converse with the individual at all.

P7, Line 55, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

As Teacher 9 highlighted, the best strategy is not to reply to the cyberbully,

Instead of reacting to communications from someone who is bullying you, report the message and ban the offender. And, if they do get past your barriers and reply, don’t answer back. This will just give them what they want, and your efforts will be in vain.

Participant teacher 9, Line 57, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

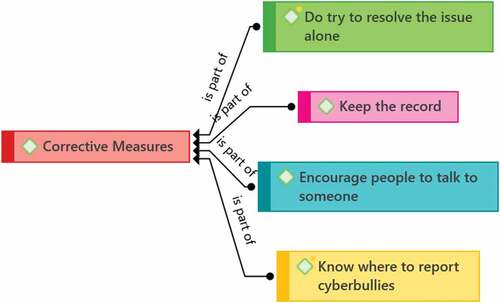

The last theme found in the analysis was concerning corrective measures. This theme is classified on what the teachers gave as advice for their students who have experienced cyberbullying.

Concerning Figure , Teacher 21 highlighted the need to not resolve the issue alone,

Do try to resolve the issue at hand. Nobody should have to cope with cyberbullying on their own. If you are a victim of this kind of conduct (or know someone who is), speak to your parents or a trusted adult. In addition to discussing how they should handle the issue, it is critical to provide them with as much information as possible so that they can appropriately report it.

Participant teacher 21, Line 69, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

For Teacher 10, he mentioned the need to keep all evidence and records of conversation in case one needs it in the future,

Whenever you encounter an issue that needs you to take action (for example, reporting someone), make a note of all the circumstances so that you may quickly report the occurrence or discuss it with a trustworthy friend or adult. Save copies of communications and keep track of who sent them to you if feasible

Participant teacher 10, Line 58, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Teacher 23 mentioned that it is also important for students to not keep the cyberbullying incident to themselves and be encouraged to talk about it.

Many individuals are afraid to discuss bullying because they fear getting in trouble or having their concerns dismissed. Instead of allowing people to believe that, urge them to speak with someone who can assist them by displaying some of the suggestions on this page.

Participant teacher 23, Line 71, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

Lastly, Teacher 6 mentioned that it is important not just to what to report, but where to report the incident of cyberbullying to the right people,

Tell someone if you’re being harassed—This one is very straightforward: if someone or a group of individuals is harassing you and won’t leave you alone, inform your parents or a trusted adult. Nobody should have to cope with bullying alone.

Participant teacher 6, Line 54, Quotation from ATLAS.ti

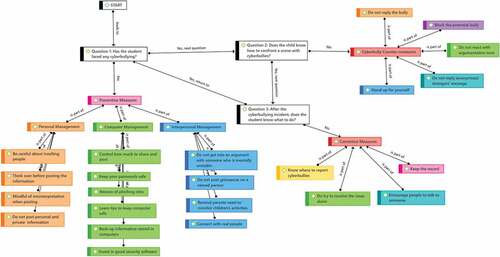

Research Question 2: What is the decision-making model that can be conceptualized based on teachers’ advice to manage to cyberbully?

Figure below is a conceptualized model based on data to guide teachers in the researched school to manage cyberbullying cases. Since the researched school population is homogenous and unique in its own school culture, there are more contextual applications to this model. As such, this model cannot be generalized to other schools in China as the circumstances of cyberbullying may be different. However, there is a possibility for knowledge transfer to readers, if they find that this model could be applied in a similar context, or that it can also be used as a reference to improve their standard operating procedures in their respective schools.

Figure 4. Conceptualization of Decision-making model based on teachers’ advice to manage cyberbullying in the researched school.

According to Figure , teachers in the researched school could always ask three questions if they suspect their students are facing problems of cyberbullying. First, they need to probe and confirm with their students if they are facing the problem recently. Based on the dichotomous answer, there will be two paths: (a) If the answer is “No”, this would lead to preventive measures that were analyzed in the previous research question; or (b) If the answer is “Yes”, this would lead to the next question. Like the dichotomous paths, teachers would be able to decide if the student knows how to confront a scene with cyber bullies, or not. If their answer is ‘No”, then this would lead to Cyberbully Counter Measures (as previously described), or if their answer is “Yes” this could lead to the last question. Finally, the student will be asked if he/she knows what to do after the cyberbullying incident. If the answer is ‘Yes’ this will return to learning more about preventive measures, while conversely, there will be corrective measures (as previously described) if their answer is ‘No’. Ultimately, this model is important because it can be used as a point of reference for teachers” decision-making. Likewise, more cycles of research could be carried out in the future on this issue to add to the list of preventive measures, countermeasures, and corrective measures that will be sustainable for the researched school.

7. Discussions

This study identifies, accumulates, and analyses the multiple pieces of advice given by teachers in the school who had encountered students with cyberbullying issues. A study needs to be conducted under a homogenous school culture so that the model can be applied contextually, and hopefully, more attempts can be made to continue this form of research in the school so that teachers and continue to build on the list of preventive measures, countermeasures, and corrective measures. The model conceptualized from this study serves as organizational learning and a guide to improving their existing standard operating protocol. It is also important that while there are many forms and instances of cyberbullying, teachers can be trained and be professionally competent to educate students to differentiate between perpetrators, victims, and bystanders in social media as mentioned by Guo et al. (Citation2021). From the teachers’ perspectives, they need to know what to do, be ready for the unexpected, and improve their organizational practices to address cyberbullying problems (Jabulani & Edward, Citation2021).

From this study, it is worth knowing that Cyberbullying differs from traditional bullying in that it may be anonymous and there are no physical consequences. However, scholars have also mentioned that cyberbullying and physical bullying are both related and often co-occur (Pichel et al., Citation2021). With the rise of social media and possibly increased screen times of students, online communication inevitably allows people to bully others anonymously in written or visual form, and this is also consistent with the findings from Menendez (Citation2020). Other scholars have also highlighted that while cyberbullying culprits may never meet the person they are bullying, the effects can still be incredibly hurtful to the emotional and psychological well-being of victims (Armitage, Citation2021). This fact is also found in the descriptions provided by the participants in this study. In addition, scholars have also highlighted that since cyberbullies are often hiding behind a computer or mobile device, they do not have empathy, and therefore feel less remorse afterward (Nocentini et al., Citation2010).

Recent studies have clearly shown that cyberbullying affects the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral states of students all over the world (Doumas & Midgett, Citation2021). Many Chinese individuals have also used virtual private networks to access international social media sites like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, etc., just as in other nations across the world (VPNs; Anderson, Citation2012). This feature provides a degree of protection against China’s censorship by encrypting data being sent between their computer and the website while also masking their location. Unfortunately, VPNs also enable internet users to access the web anonymously, and this increases the probability of toxic communications and cyberbullying (Chan et al., Citation2021). As mentioned by the teacher participants of this study, students must be taught how to manage their computer security to avoid uninvited guests, hackers, or invitations to communicate with dangerous people. They must also learn how to manage themselves, avoid joining wrong groups on social media, or be taught interpersonal skills such as (conflict management) when dealing with difficult people online. These suggestions are also suggested by other scholars like Nappa et al. (Citation2021). From this study, teachers can refer to the conceptualized model to learn about countermeasures and corrective measures that are also important to manage the situation. Lastly, this study proposes that teachers be trained to educate their students about the potential cause, its symptoms, and techniques to manage to cyberbully better in the researched school. Likewise, this conceptualized model could be improved elsewhere in China as needed.

8. Conclusions

With the advancement of digital technology and social media sites, cyberbullying has become a global issue that will have a significant impact on the development of China’s young people Junke, Citation2020). As cyberbullying can take many forms, there must be must awareness for students when using social networks or platforms. Cyberbullies take advantage of the vulnerable, underdeveloped psychological state of adolescents, and this negatively affects their thinking, emotions, and behaviors. The severity can be worse than standard school bullying, with sufferers unable to manage their daily responsibilities. There was already evidence that shows that cyberbullying leads to stress, and ultimately suicide (Peng et al., Citation2019). Education policymakers felt that is needful to offer countermeasures based on teachers’ experiences to construct a protection framework for youth cyberbullying in China and preserve legitimate rights and interests (Zhou, Citation2021).

This study has achieved its core research objectives and adds to the body of knowledge in cyberbullying. In essence, teachers’ perceptions are important, and their advice should be compiled from more research so that education policymakers, school administrators, and teachers can decide on their actions to battle the rising mental health problems among students in China. From this study, it is known that teachers in the researched school have provided their advice to students through prevention, countermeasures, and corrections of the problem. In conclusion, more can be done by teachers to add to the list of tactics so that school communities can learn to manage this issue more effectively and sustainably. This action will help support the understanding of a myriad of factors that are causing cyberbullying to become such a serious issue in China (Li & Hesketh, Citation2021), and this study calls for future actions to manage this issue from the teacher and students’ level of trust and relationship in the classroom.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Han Zhao

Han Zhao has a Bachelor of Science from the University of Essex in July 2022. His research interests include accounting and finance, banking, and quantitative finance. She is also the recipient of the Dean’s List for the Faculty of Social Sciences in 2021. Currently, she is a masters’ student at the University of Manchester with a specialization in management.

Hao Weng

Hao Weng has an MBA background, and currently serving as one of the board of directors in Vanda International Education Group

Qiming Weng

Qiming Weng is the CEO of Vanda International Education Group

Zhaoyuan Huang

Zhaoyuan Huang received his master’s degree in Economics from the University of Malaya in August 2022. His research interests are in macroeconomics, microeconomics, the economics of education, and educational psychology. He published “Different Types of Taxes On Economic Growth In China” as the first author in Modern Economics & Management.

Kenny Cheah Soon Lee

Kenny Cheah Soon Lee is currently the Chair of CRELAMP (Center for Research in Educational Leadership, Administration, Management and Policy), and a Senior Lecturer based in the Faculty of Education, University Malaya. He is the recipient of the private research grant from Vanda International Education Group

References

- Anderson, D. (2012). Splinternet behind the great firewall of China: Once China opened its door to the world, it could not close it again. Queue, 10(11), 40–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/2390756.2405036

- Ansary, N. S. (2020). Cyberbullying: Concepts, theories, and correlates informing evidence-based best practices for prevention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50(1), 101343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.101343

- Armitage, R. (2021). Bullying in children: Impact on child health. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 5(1), e000939. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000939

- Bailey, J. (2008). First steps in qualitative data analysis: Transcribing. Family Practice, 25(2), 127–131. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn003

- Belsey, B. (2005). Cyberbullying: An Emerging Threat to the Always On Generation. http://www.cyberbullying.ca/pdf/Cyberbullying_Article_by_Bill_ Belsey.pdf

- Bian, Y., & Ikeda, K . (2018). Encyclopedia of Social Network Analysis and Mining (pp. 417–433).

- Burla, L., Knierim, B., Barth, J., Liewald, K., Duetz, M., & Abel, T. (2008). From text to codings: Intercoder reliability assessment in qualitative content analysis. Nursing Research, 57(2), 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NNR.0000313482.33917.7d

- Chan, T. K., Cheung, C. M., & Lee, Z. W. (2021). Cyberbullying on social networking sites: A literature review and future research directions. Information & Management, 58(2), 103411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2020.103411

- Chen, Z. T. (2021). Poetic prosumption of animation, comic, game and novel in a post-socialist China: A case of a popular video-sharing social media Bilibili as heterotopia. Journal of Consumer Culture, 21(2), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540518787574

- Chen, S. C., & Lin, C. P. (2019). Understanding the effect of social media marketing activities: The mediation of social identification, perceived value, and satisfaction. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 140, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.11.025

- Chen, Q., & Zhu, Y. (2022). Cyberbullying victimisation among adolescents in China: Coping strategies and the role of self‐compassion. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(3), e677–e686. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13438

- Cui, Y., Xie, X., & Liu, Y. (2018). Social media and mobility landscape: Uncovering spatial patterns of urban human mobility with multi source data. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering, 12(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11783-018-1068-1

- Doumas, D. M., & Midgett, A. (2021). The association between witnessing cyberbullying and depressive symptoms and social anxiety among elementary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 58(3), 622–637. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22467

- Friese, S. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS. ti. Sage.

- Ge, Y., Se, J., & Zhang, J. (2015). Research on relationship among internet-addiction, personality traits and mental health of urban left-behind children. Global Journal of Health Science, 7(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v7n4p60

- Gong, M., Yu, L., & Luqman, A. (2020). Understanding the formation mechanism of mobile social networking site addiction: Evidence from WeChat users. Behaviour & Information Technology, 39(11), 1176–1191. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1653993

- Guo, S., Liu, J., & Wang, J. (2021). Cyberbullying roles among adolescents: A social-ecological theory perspective. Journal of School Violence, 20(2), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2020.1862674

- Hall, J. A. (2020). Relating through technology: Everyday social interaction. Cambridge University Press.

- Han, Z., Wang, Z., & Li, Y. (2021). Cyberbullying involvement, resilient coping, and loneliness of adolescents during COVID-19 in rural China. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2275. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.664612

- Houghton, C., Murphy, K., Shaw, D., & Casey, D. (2015). Qualitative case study data analysis: An example from practice. Nurse Researcher, 22(5), 8–12. https://journals.rcni.com/nurse-researcher/qualitative-case-study-data-analysis-an-example-from-practice-nr.22.5.8.e1307

- Huang, J., Zhong, Z., Zhang, H., & Li, L. (2021). Cyberbullying in social media and online games among Chinese college students and its associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094819

- Jabulani, N., & Edward, L. M. (2021). The whole-school approach to manage cyberbullying: Lessons from South African schools. Journal of Educational Studies, 20(1), 55–75. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/ejc-jeds_v20_n1_a5

- Jiang, M., & Fu, K. W. (2018). Chinese social media and big data: Big data, big brother, big profit? Policy & Internet, 10(4), 372–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.187

- Junke, X. (2020). Legal Regulation of Cyberbullying—From a Chinese perspective. In 2020 IEEE Intl Conf on Dependable, Autonomic and Secure Computing, Intl Conf on Pervasive Intelligence and Computing, Intl Conf on Cloud and Big Data Computing, Intl Conf on Cyber Science and Technology Congress (DASC/PiCom/CBDCom/CyberSciTech) (pp. 322–327). IEEE.

- Li, W. (2020). The language of bullying: Social issues on Chinese websites. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 53, 101453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101453

- Li, J., & Hesketh, T. (2021). Experiences and perspectives of traditional bullying and cyberbullying among adolescents in Mainland China-implications for policy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2688. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.672223

- López-Castro, L., & Priegue, D. (2019). Influence of family variables on cyberbullying perpetration and victimization: A systematic literature review. Social Sciences, 8(3), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030098

- Lu, S., Zhao, L., Lai, L., Shi, C., & Jiang, W. (2022). How do Chinese people view cyberbullying? A text analysis based on social media. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1822. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031822

- Lyu, Y. (2022). Cyberbully and cyber populism in China’s social media. In 2021 International Conference on Education, Language and Art (ICELA 2021) (pp. 683–688). Atlantis Press.

- Maneesriwongul, W., & Dixon, J. K. (2004). Instrument translation process: A methods review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03185.x

- Marczak, M., & Coyne, I. (2010). Cyberbullying at school: Good practice and legal aspects in the United Kingdom. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 20(2), 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.20.2.182

- Menendez, J. (2020). Cyberbullying victimization and corresponding distress in women of color. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cps_diss/143/

- Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. Jossey-Bass.

- Mohammed, M. O. B., Gbenu, J. P., & Lawal, R. O. (2014). Planning the teacher as in Loco parentis for an effective school system. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(16), 318. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n16p318

- Nappa, M. R., Palladino, B. E., Nocentini, A., & Menesini, E. (2021). Do the face-to-face actions of adults have an online impact? The effects of parent and teacher responses on cyberbullying among students. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 798–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2020.1860746

- Nocentini, A., Calmaestra, J., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Ortega, R., & Menesini, E. (2010). Cyberbullying: Labels, behaviours and definition in three European countries. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 20(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.20.2.129

- Pan, J. (2017). How market dynamics of domestic and foreign social media firms shape strategies of internet censorship. Problems of Post-Communism, 64(3–4), 167–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1181525

- Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2006). Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 4(2), 148–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204006286288

- Peng, Z., Klomek, A. B., Li, L., Su, X., Sillanmäki, L., Chudal, R., & Sourander, A. (2019). Associations between Chinese adolescents subjected to traditional and cyber bullying and suicidal ideation, self-harm and suicide attempts. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2319-9

- Peter, I. K., & Petermann, F. (2018). Cyberbullying: A concept analysis of defining attributes and additional influencing factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 86, 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.013

- Pichel, R., Foody, M., O’Higgins Norman, J., Feijóo, S., Varela, J., & Rial, A. (2021). Bullying, cyberbullying and the overlap: What does age have to do with it? Sustainability, 13(15), 8527. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158527

- Rao, J., Wang, H., Pang, M., Yang, J., Zhang, J., Ye, Y., Dong, X., Wang, S., & Dong, X. (2019). Cyberbullying perpetration and victimisation among junior and senior high school students in Guangzhou, China. Injury Prevention, 25(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042210

- Sperber, A. D., Devellis, R. F., & Boehlecke, B. (1994). Cross-cultural translation: Methodology and validation. Journal of cross-cultural Psychology, 25(4), 501–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022194254006

- Stevens, V., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., & Van Oost, P. (2000). Bullying in Flemish schools: An evaluation of anti‐bullying intervention in primary and secondary schools. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(2), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709900158056

- Suen, L. J. W., Huang, H. M., & Lee, H. H. (2014). A comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Hu Li Za Zhi, 61(3), 105. https://www.proquest.com/openview/56f5d21e88d7b1f484434edd4b42f210/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=866377

- Symons, M. M., Di Carlo, H., & Caboral‐Stevens, M. (2021). Workplace cyberbullying exposed: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 56(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12505

- Tate, B. P. (2017). A case study of policies and procedures to address cyberbullying at a technology-based middle school (Doctoral dissertation, Mercer University).

- Wang, L. (2021). The effects of cyberbullying victimization and personality characteristics on adolescent mental health: An application of the stress process model. Youth & Society, 54(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X21100892

- White, J. A., Carey, L. M., & Dailey, K. A. (2001). Web-based instrumentation in educational survey research. WebNet Journal: Internet Technologies, Applications & Issues, 3(1), 46–50. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/8988/

- Xu, Y. (2021). The invisible aggressive fist: Features of cyberbullying language in China. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law-Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 34(4), 1041–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09746-1

- Xu, V. W. (2022). WeChat and the Sharing of News in Networked China. Digital Journalism, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2053335

- Yang, K. (2022). Beyond parochial activism: cross-regional protests and the changing landscape of popular contention in China. Journal of Contemporary China, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2022.2071907

- Yu, D. S., Lee, D. T., & Woo, J. (2004). Issues and challenges of instrument translation. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 26(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945903260554

- Zhang, S. (2021). From flaming to incited crime: Recognising cyberbullying on Chinese wechat account. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law-Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 34(4), 1093–1116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09790-x

- Zhang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2022). High school cyberbullying and adolescents’ depression in China. In 2021 International Conference on Education, Language and Art (ICELA 2021) (pp. 475–480). Atlantis Press.

- Zhou, S. (2021). Status and risk factors of Chinese teenagers’ exposure to cyberbullying. SAGE Open, 11(4), 21582440211056626. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211056626

- Zhu, Y., Li, W., O’Brien, J. E., & Liu, T. (2021). Parent–child attachment moderates the associations between cyberbullying victimization and adolescents’ health/mental health problems: An exploration of cyberbullying victimization among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17–18), NP9272–NP9298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519854559

- Zimbardo, P. G. (2004). A situationist perspective on the psychology of evil: Understanding how good people are transformed into perpetrators. In A. G. Miller (Ed.), The Social Psychology of Good and Evil (pp. 21–50). https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-16379-002