Abstract

Creativity is the driving force of technological innovation and sustainable economic growth in the knowledge society. A central question, therefore, is how education helps to enhance creativity. As East Asian countries occupy the top of performance tests such as the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), it is most important to understand the type of creativity they stand for. For doing so, we first investigate the revival of Confucianism and its idea of creativity in these countries in comparison with the Western Enlightenment idea of creativity. Secondly, we scrutinize how far these two types of creativity are represented in PISA’s understanding of problem solving which is assumed to require creativity from students. Thirdly, we conduct multilevel regression analyses with data from the 2009 PISA test to find out which learning strategies help to achieve in the PISA test and to close achievement gaps based on socioeconomic family background and how they relate to the two types of creativity. Two countries representing the Confucian tradition, the Republic of Korea and Singapore, and two countries representing the Western tradition, the United States and Canada, serve as test cases. As a culturally diverse world needs both types of creativity, the fundamental question is whether PISA helps them to flourish both.

Public Interest Statement

East Asia has achieved to serve as center of economic growth worldwide. China is going to establish itself as leading economic power of the 21st century. At the same time, East Asian school systems excel at the top of international comparative studies on educational performance. The most influential of these studies is the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) conducted every three years by the OECD, Citation2020. Economists argue that worldwide best education is the basis for the extraordinary economic performance of East Asia. In this study, addressing the revival of Confucianism in East Asia, we demonstrate that PISA favors more the Eastern Confucian type of learning and creativity conducive to incremental innovation as against the Western Enlightenment type of learning and creativity, conducive to radical innovation. We recommend that comprehensive knowledge development needs both types of learning in a complementary relationship.

1. Introduction: Culture, education regime, learning and creativity

According to many experts, a top-performing school system is of central importance for the rise of East Asia—always including Singapore in Southeast Asia in the following—to the most prosperous economic region in the world (Barber & Mourshed, Citation2007; Mourshed et al., Citation2010; Schleicher, Citation2018; Tucker, Citation2011). For education economists, East Asia is the striking proof that good education pays off in hard cash (Hanushek & Woessmann, Citation2015). It is precisely this connection between education and economic advancement that makes East Asia a challenge to the West (Tan, Citation2012a; You, Citation2019). It is also widely claimed that this best performance of East Asian school systems includes that higher performance is not only shown at the top but across all social classes so that family background is less important for educational achievement than in most other countries in the world (Schleicher, Citation2014; cf., however, for more nuanced analyses Teng et al., Citation2019; Kim, Citation2019). Does East Asia’s education regime tell the world how to overcome barriers to educational achievement as well as the continued reproduction of social inequality? Is the so-called Chinese learner a success model for all over the world (cf., Li, Citation2017; Morrison, Citation2006; Sellar & Lingard, Citation2013; Watkins & Biggs, Citation1996)? Apparently, learning in East Asia is superior to learning in other regions of the world, both in terms of quality and equity (cf., Boman, Citation2022; Tan, Citation2012a). Therefore, clarification is needed about the specific features of learning in this region of the world (cf., Kennedy & Lee, Citation2007). As there is broad consensus that creativity is the crucial source of innovation and innovation the key to sustainable economic growth and wellbeing of everybody in the contemporary knowledge society, we have to scrutinize how learning in East Asia stands with regard to creativity in comparison to the West. This is what we do in this study.

The three questions we want to answer are (1) how the Eastern and Western cultures conceive of learning and creativity, (2) how they are represented in tasks of creative problem solving in the PISA test, and (3) how they help to achieve in the PISA test, both in terms of quality and equity, that is in terms of test performance and reducing achievement gaps based on socioeconomic family background. In doing so, we join Komatsu and Rappleye’s (Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2021) plea for “rearticulating PISA” by way of using PISA for reflecting on PISA and its impact on our understanding of creativity in education.

We start with the assumption that learning always takes place in a cultural and institutional setting and applies strategies which are embedded in this setting. They are legitimized by cultural values and set into practice in the institutional context of school systems and schools. An educational regime is a specific arrangement of cultural values, institutions, and institutionalized learning strategies. In this study, we focus on two educational regimes with different cultural roots, institutional practices and learning strategies. These are a Western education regime rooted in the Enlightenment and an Eastern education regime rooted in Confucianism. For reasons of space, we cannot address Hinduism and Buddhism as two other East Asian religions which exert an influence on learning. For highlighting the features of the two chosen regimes in the first step of this study, we start with Max Weber’s (Citation1951) classical comparison of Puritanism and Confucianism in his comparative sociology of religions, and we discuss the current state of research on this subject matter. We spell out the learning strategies embedded in these two cultures and institutionalized school and examination systems.

In the second step, we ask how these learning strategies are reflected in contemporary international educational benchmarking as it is represented by studies like the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) as it started in 2000 and is conducted every three years (OECD, Citation2020). We focus on the meaning of creativity in problem solving in the PISA test. The question is how close the meaning of problem solving in the PISA test is to the Eastern Confucian or Western Enlightenment understanding of creativity. Furthermore, we look at the Global Creativity Index of 2015 to identify how the position of countries in the PISA science ranking of 2015 relates to the position in this index. In the third step, we link our findings about learning in East Asia and the West to the school disciplinary climate and to learning strategies as surveyed in the 2009 PISA test to build a bridge to a statistical analysis based on PISA data from this year.

Learning strategies have not been focused to the same extent in other test waves. Therefore, we chose the 2009 PISA test. As learning strategies are deeply embedded in cultural traditions, they do not change for a long time. And the PISA test has not changed its approach of a highly standardized assessment. Therefore, our results should hold not only for 2009 but also for the more recent test waves and for the foreseeable future. We test with a multilevel regression analysis how far learning strategies, which are more or less close to the preferred mode of learning in East Asia or the West, explain the variance of PISA test scores in reading. Furthermore, we test how far learning strategies, which we interpret as more or less close to East Asian or Western learning, help to reduce the impact of socioeconomic family background on PISA performance. Thus, we investigate how far learning strategies advance both, quality and equity.

For comparison, we include two East/Southeast Asian and two Western countries in the analysis, the Republic of Korea respectively South Korea and Singapore, on the one hand, Canada and the United States, on the other hand. The United States stands for the very liberal idea of Western culture, Canada for the extension of this idea to multiculturalism as a paradigm of tolerance and mutual recognition. In the Republic of Korea, the Confucian method of filling administrative positions through a comprehensive examination system to which the entire educational process is directed was introduced in 958 A.D. To this day, this system is set on self-improvement and discipline, on the integration of the individual into the community. This includes a strict disciplinary regime in school, represented by the absolute authority of the teacher over the students. In modern times, the model of status assignment has been extended beyond administrative positions to the entire employment system through a strict examination regime (Kwon et al., Citation2017; Leighanne, Citation2019). Singapore is a culturally diverse city state assembling people with a Chinese, Malay, Indian or other background. About three quarters of the people identify as Chinese, about 13 to 14% as Malay, about 9 to 10% as Indian, about 3 to 4% as others (Tan, Citation2012b, p. 449). With most people of Chinese origin, it is no surprise that the Confucian heritage is visible in Singaporean everyday life, in family, economy, politics and civil society and certainly in the idea of education and the organization of schools. In 1988, the then Deputy Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong emphasized “community and society before the self, family as the basic unit of society, community support and respect for the individual, consensus, not conflict and racial and religious harmony” as common values shared by all Singaporeans (Tan, Citation2012b, pp. 450–451). These values have been understood as basically Communitarian and Confucian. However, as argued by Tan (Citation2012b) from her interpretation of the Confucian philosophy, there is an overemphasis on community and too little respect for individual rights. Anyway, we can say that schools in Singapore are bearers of a Confucian heritage (cf., Ortmann & Thompson, Citation2016; Sim & Chow, Citation2019).

2. The Western Enlightenment and Eastern Confucian modes of learning and creativity

For understanding East Asian education, it is indispensable to go back to Confucius. The fact that Confucianism in China, after half a century of banishment from science, education, politics and business, has regained enormously in importance since the 1980s is undisputed in the research literature. The introduction to an anthology on this revival of Confucianism notes:

“We all know that China’s economy has grown rapidly since the early 1980ʹs … Nevertheless, we often forget that, concomitant with this ‘economic miracle,’ a ‘cultural miracle’ has unfolded. Condemned as a relic of feudalism for more than half a century, Confucianism enjoyed a robust revival during the 1980s and 1990s, as post-Mao China was gradually integrated into the global economy.” (Hon, Citation2017, p. xi)

Since for Confucianism the right education is the cornerstone of the right conduct of life and of society as a whole, any attempt to understand and explain the rise of East Asia—first Japan, then South Korea, Singapore and China—to the leading economic region of the world in the 21st century must begin with a fundamental analysis of this very specific educational regime. From the point of view of historical studies, Max Weber’s (Citation1951, pp. 226–249) contrasting of Confucianism and Puritanism in his comparative sociological studies on world religions may be lacking historical accuracy at one or the other point. However, his approach does not aim at historical details but at constructing ideal types which help to highlight and understand special cultural and structural features in their uniqueness and their consequences for society, independent of their appearance in concrete historical situations. And looking at contemporary research on the revived Confucian roots of education in East Asia, tells us that Weber can still serve as a most valuable guide for understanding the special Confucian type of rationalism in comparison to the Western type of rationalism as it is rooted in Puritanism (Weber, Citation2002).

According to Weber, Confucianism essentially produced an attitude of adjustment to the world, while Puritanism created an attitude of mastery of the world (cf., Münch, Citation2001, pp. 15–33). As Weber (Citation1951) notes, for Confucianism it is important to keep the existing world in harmony, for Puritanism it is about changing an inherently imperfect world according to ethical standards:

“In this is vested the basic difference between the two kinds of rationalism: Confucian rationalism meant rational adjustment to the world; Puritan rationalism meant rational mastery of the world.” (p. 248)

Weber (Citation1951, pp. 227–230) sees in the belief in a Creator God, whose perfection stands in stark contrast to the facticity of the imperfect world, on the one hand, and the absence of such a Creator God, on the other hand, the essential reason for this difference between Puritanism and Confucianism. Puritanism is a religion of redemption with a bourgeois class of adherents that creates a modern order against the traditional order. Confucianism is a cultural religion with a literary civil service class as a carrier stratum that administers an existing order and keeps it in balance. We can also observe this difference in secularized modernity and relate it to the educational process. According to the understanding of the Western Enlightenment, the educational process aims at the mature individual who is capable of thinking beyond the given and changing it according to the standards of reason (Münch, Citation1986, pp. 172–178). According to the understanding of Confucianism, the educational process consists in the self-cultivation of the individual in order to enable him/her to fit into the existing order and thus to preserve the harmony of the world order (Lai, Citation2006).

The old Chinese empire was an administrative state dominated by so-called literary officials. The officials had to go through a special educational process according to the writings of Confucius in order to meet the requirements for filling an administrative post. What was already special at that time, was the extensive examination system—reaching from county exams via provincial and metropolitan exams to the palace exams—to which the entire learning process was tailored (Elman, Citation2013). The system was meritocratic in that sense that every man (but not woman) could try the exams. However, only wealthy families could afford their sons spending years of learning for the exams. Candidates prepared for the exams by exercising sample solutions from previous exams. This was learning in the examination or control mode (Suen & Yu, Citation2006; Elman, Citation2013, pp. 33–34). The repetitive and reproductive character of the educational process also included a pedagogy geared to the strictest discipline (Weber, Citation1951, p. 130). And the civil servant had to continuously prove himself worthy of his position. Weber (Citation1951, p. 129) described this form of “lifelong learning” as “lifelong pennalism”. The performance of the official was recorded meticulously and made public, a precursor of today’s emphasis on comprehensive accountability in New Public Management (Weber, Citation1951, p. 133).

The educational process consisted in learning literary writings that dealt with questions of the good life, but not with specialist administrative issues. The incumbents of the administrative offices were not supposed to be technical specialists, but educated people, so that they could serve as role models for the good life. The scholar was therefore at the top of the status hierarchy, well above the merchants, craftsmen and farmers. This was because it was the scholars themselves who, based on their leading position, determined which way of life should enjoy the highest respect. It was the view that seemed “natural” to the literary official to imagine the world as a well-ordered whole into which the individual must fit so that it does not fall into imbalance. Disturbances of order were to be avoided as far as possible. Nobody wanted to be the cause of a disturbance. Consequently, great importance was attached to saving face in all situations (Weber, Citation1951, p. 237). Questioning the knowledge order and the social order built upon it was unthinkable within this world view. Learning as controlled preparation for exams using material from previous exams implied that the Confucian view of the world shaped thought and action without reflecting on it. Learning meant to reproduce the existing knowledge, but not to criticize it in order to renew it. The fact that the literati went through this socialization process made them well-functioning officials in the old Chinese administrative state. And because imperial China was an administrative state, the civil servants held the leading position in society. In their position, they made the administrative view the dominant view of the world (Weber, Citation1951, pp. 107–141).

The learning process within the Confucian examination system was in the first stage concentrated on pictorial writing (Weber, Citation1951, pp. 123–124). The reproduction of given things is much more and longer in the foreground here than in the practice of the Latin characters. The meaningful component of writing, the understanding of meaning and the use of writing to formulate contexts of meaning and even more so to formulate one’s own thoughts, remains more and longer in the background than when learning the Latin script. This difference is further accentuated when one compares the teacher–student relationship in the Confucian examination system on the one hand and in the Hellenic academy on the other. In Confucianism, the piety of the student toward the teacher is the decisive basic structure, in the Hellenic academy it is the dialogue. The latter is an open process that drives both, teacher and student, not simply to reproduce given knowledge, but to take it as a starting point for developing new knowledge.

Against this contrasting of the reproduction of given knowledge on the one hand and the acquisition and development of knowledge in thesis and antithesis on the other, one could refer to the Confucian analects as answers of the master to questions of the pupils and see in them a form of dialectic (Weber, Citation1951, p. 124). The Analects are a collection of conversations between the master and his students which was compiled after Confucius’ death (473 AD) by his students. In the Socratic dialogue, however, the teacher invites the student to critically examine the ideas presented and to develop his own thoughts, while in the Confucian conversation the master teaches the student to respectfully acquire the given knowledge in order to refine his behavior (Gorry, Citation2011; Lai, Citation2006; Tweed & Lehmann, Citation2002). According to the current state of research, Weber rightly identified traditionalism rooted in the absence of dialogue and the associated hostility to renewal as a characteristic feature of Confucianism. But Daoism also had in common with Confucianism the endeavor to maintain an order and the knowledge of it, not to find new knowledge and create a new order (Weber, Citation1951, p. 205).

However, one could oppose that the imperial examination system was abolished in 1905 and since then, with the interruption of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), the Chinese educational system has been opened to Western influences (Zha, Citation2011), increasingly since 1980, so that it has no significance for the present situation. However, this is not the case. Essential features of this system are still clearly visible in the current predominant role of examinations in the Chinese education system as well as in the other East Asian countries with a Confucian tradition. The National College Entrance Exam (NCEE), which was introduced in 1953 and has since been reformed several times and adapted to Western standards, plays a central role similar to the imperial examination system. However, orientation to Western standards does not exclude that typical features of the imperial examination system remain effective in a new form (Niu, Citation2012, p. 83). Despite all efforts to modernize, examination as dominant part of education continues unchanged and is deeply rooted in the tradition of Confucianism (Zhao, Citation2014, pp. 132, 159–160).

It is by no means the case, however, that there is no place for creativity in the tradition of Confucianism and Daoism. Against this view already speaks that China was superior to the West in technological inventiveness—such as paper, letterpress printing, gunpowder, magnetic compass, porcelain, mechanical clockwork, iron foundry or stirrups—until the 15th century (cf., Needham, Citation1969/2005, pp. 154–217; Münch, Citation1984, pp. 212–216; Staats, Citation2011). It is even argued that the characterization of Confucianism and Daoism as hostile to creativity is merely a Western prejudice and that these teachings simply stand for a different kind of creativity (Tsai, Citation2013). Therefore, we should not simply oppose Western creativity to Eastern “conformism”. The latter would mean—as is indeed Weber’s above-cited position—not to question established norms and knowledge but rather following them strictly. This would be inadequate for characterizing the Eastern culture. We should understand the difference between East and West as a difference in the type of creativity as rooted in these two cultures instead. Western creativity is anchored in the Judeo-Christian tradition, in the Enlightenment and the bourgeois lifestyle, and finally in capitalist entrepreneurship, science and art. Eastern creativity has its roots in the teachings of Confucianism, Daoism, Hinduism and Buddhism of which our focus is on Confucianism because it is the most relevant teaching for the renewed rise of the East to the top in terms of science, technology and economy (cf., Gorry, Citation2011; Tweed & Lehmann, Citation2002).

In the West, the Enlightenment simply transferred the Judeo-Christian idea of the Creator God to the human individual, who is said to have the ability to break with tradition and create something completely new, ultimately to question an existing order of knowledge and rule and to overthrow it in a revolutionary act. This is already present in Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: “It is written, but I say to you.” Creativity in the Western sense is exactly what Joseph Schumpeter (Citation1943/2013) identified as the central characteristic of the entrepreneur and the source of capitalist economic dynamism: creative destruction. Creativity according to the Confucian teaching, however, consists of learning the teachings of the given tradition and building on it in such a way that it can continue to exist in the future. In Daoism, creativity means to fit into the Dao through meditation in such a way that the human being and nature form a perfect whole. Both conceptions of creativity demand from the human being to work on himself or herself on the way to self-improvement, which is neither an end in itself nor an idealization of the individual but has the sole aim of creating a perfect world order (cf., Lai, Citation2006; Niu, Citation2012). An analysis by Charlene Tan (Citation2016) of the analects (conversations) of Confucius summarizes the understanding of creativity contained therein as follows:

“Confucius demonstrated and advocated a moral and social conception of creativity that emphasizes evolutionary rather than revolutionary changes. Confucius supported incremental changes that were built upon the wisdom of the past, and posited the need for everyone to engage in moral self-cultivation within a community.” (p. 84)

Tan (Citation2016, p. 84) admits that she talks about the idea of creativity rooted in the teaching of Confucius from which the practice of teaching and examining may deviate more or less. She understands her interpretation of Confucian creativity as, on the one hand, a demarcation from the Western type of creativity and, on the other hand, as a philosophical guideline for educational reform in East Asia. Along her Confucian idea of creativity, she also shows that there is a special Confucian kind of critical thinking to be found in the analects. It is a kind of critical thinking which guides practical action as incremental advancement of practice in social harmony which also includes steps of extending the framework of the Dao (Tan, Citation2017).

Of course, the fact that Confucianism was part of an imperial system of rule, for which the preservation of this system was a top priority, played a decisive role in the development of this understanding of creativity. Crucial for the kind of creativity awarded is not the system of ideas alone, but its interweaving with the given institutions of a society (see, Ho & Ho, Citation2008). Creativity in the radical sense needs an environment which allows for exploration and experimentation. This is, for example, missed with teachers who understand creativity only in cognitive terms as a study on South Korean science teachers shows (Seo et al., Citation2005; see, Weber, Citation1951, pp. 107–141).

The great success of East Asian school systems in international performance tests, above all PISA, also raises the question of how far not only reproductive, but also creative abilities are featured. In the research literature, it is seen as paradoxical that Chinese students, like their peers in other East Asian countries, achieve top scores in international performance tests, even though they seem to learn under less favorable conditions and use less effective learning strategies in an examination system that is focused on reproducing canonized knowledge (Watkins & Biggs, Citation1996, Citation2001). Keith Morrison (Citation2006) summarizes the paradox of the successful “Chinese learner” as follows:

“The paradox of the Chinese learner is intriguing for Westerners and Chinese alike. In a nutshell, it questions why, despite using rote learning, memorization, repetition, constant testing, large classes, competitive motivation, examination orientation, authoritarian and didactic teaching and learning methods, passivity and compliance - in short the presence of putative negative features of teaching and learning, together with a supposed absence of many positive features of effective teaching and learning, Chinese students consistently achieve more highly than their Western counterparts, who are highly adaptive, prefer high-level meaning-based learning strategies, and engage in deep learning.” (p. 3)

Morrison discusses ten possible explanations for this paradox. Explanation no. 1 considers the characterization of the Chinese learning culture as Western prejudice (see, Li, Citation2017). Explanation no. 2 simply says that the practices discredited as “putative” are effective, as proven by international performance tests. Explanation no. 3 claims that East Asian students are inherently more intelligent than all other students. Explanation no. 4 sees the main reason for the leading position of East Asian countries in international tests as being the greater diligence of their students. Explanation no. 5 derives from the high effort mentioned in explanation no. 4 that under this condition even less good teaching and learning methods lead to very good test scores because they are compensated by diligence. Explanation no. 6 emphasizes that school and education in the East Asian countries have a high value in the Confucian tradition and form an essential part of the culture. Explanation no. 7 makes the affinity between the typical tasks in international performance tests and the typical tasks in the usual in-country tests responsible for the top results of the East Asian countries. Explanation no. 8 considers East Asian students to be particularly smart “test takers” who, above all, show test intelligence which enables them to achieve top scores in all tests, regardless of their content. Explanation no. 9 draws attention to the so-called Hawthorne Effect, an increase in performance solely due to the high level of attention paid to the test. Explanation no. 10 ultimately recognizes the East Asian culture as the crucial basis for the top results of the countries belonging to this culture.

It is not really possible to distinguish clearly between these ten explanations. They rather revolve around a syndrome in which they meet each other. It is the culture of Confucianism, with its special focus on the piety of the younger with regard to the older, on education as a vehicle for acquiring status, and on a comprehensive examination system with a high degree of standardization that must be passed in order to attain status. The secondary virtues of this syndrome include great diligence, learning in control mode and the acquisition of test intelligence. And it is in the nature of things that, where such a system of testing is practiced, there is a high degree of standardization of test items for reasons of comparability of performance. International performance tests have to proceed in exactly the same way in order to achieve reliable and valid results. This inevitably ends in a high degree of congruence between the national test procedures in East Asia and international performance tests. The international student performance comparisons show therefore an elective affinity with the historically deeply rooted Confucian educational regime and examination system in East Asia (cf., Suen & Yu, Citation2006). This is the common core of the ten explanations identified by Morrison for the leading position of East Asian countries in international student performance tests. And there is every reason to assume that this is also the basis of the top performance of East Asian students going to school in Western countries with very different regimes of school governance (Feniger & Lefstein, Citation2014; Hsin & Xie, Citation2014; Jerrim, Citation2015).

3. Creativity in problem solving in the PISA test

Regarding stimulation of creativity, there are obviously strong indications that according to the Confucian frame the East Asian educational regime does not favor the kind of radicalism that has so far been at least the playbook of Western education rooted in the European Enlightenment. This judgment could be countered by the fact that it is precisely the countries representing this regime which score highest at issues where problem solving is required. Singapore, the Republic of Korea, Japan, Macao, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Taipei (Taiwan) are also on top of this PISA ranking of 2012 with scores between 562 and 534 (OECD, Citation2014, Figure V.2.3). It could be argued that problem solving requires creative skills, which would suggest that the educational regime of East Asian countries is obviously not exclusively focused on reproductive learning. To validate this statement, we need to take a closer look at the problem-solving tasks in the PISA study. The OECD’s (Citation2014) report on PISA 2012 defines problem-solving competence as follows:

“ … an individual’s capacity to engage in cognitive processing to understand and resolve problem situations where a method of solution is not immediately obvious. It includes the willingness to engage with such situations in order to achieve one’s potential as a constructive and reflective citizen.” (p. 30)

It is emphasized that problem solving is a non-routine task and requires dealing with an open situation and being inventive enough to be able to deal with it:

“Although some students may be familiar with the context or the goal of a problem situation that refers to a plausible real-world scenario, the particular problem faced is novel and the ways of achieving the goal are not immediately obvious.” (p. 30)

The study argues that the future labor market will increasingly demand problem-solving skills, and that the employment rate for this type of work will increase significantly, while that for routine activities will decrease significantly. However, it is not only about competent employees. According to the OECD definition, problem-solving skills are also a characteristic feature of “constructive and reflective citizens”. This clearly brings “problem-solving competence” close to “creativity”. However, it would go too far to equate the two terms in their meaning. Solving a problem certainly requires a certain amount of creativity. One must be able to recognize the problem and find a solution. The finding part of the task is the creative process.

However, if we recall the distinction between paradigm shift and puzzle solving within the framework of a dominant paradigm in Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Kuhn, Citation1962/2012), then puzzle solving—which is a form of problem solving—is a practice of normal science. This means that while problem solving is a process of discovery and requires creativity, it does so only to a modest degree in comparison to the paradigm shift. Problem solving does not call existing knowledge into question, but rather mobilizes the available explicit and implicit knowledge. It is part of an everyday practice in which problems are solved by looking for similarities of the new situation with previously experienced situations. The unfamiliar is brought into relation with the familiar and thus becomes understandable and manageable.

If one looks at the tasks that are classified as problem solving in the OECD study, it can be seen that this type of creativity proceeds on existing pathways. These are tasks from everyday life for which it is not school knowledge that needs to be activated but everyday experience. For example, an MP3 player, air conditioning or a ticket machine must be operated (OECD, Citation2014, pp. 35–40). Another task is to use a network map of traffic routes in a city to determine in which suburb three friends living in different suburbs can meet if none of the three should be on the move for more than 15 minutes (OECD, Citation2014, pp. 41–44). None of these tasks requires the questioning and criticism of existing knowledge, the exploration of the background of this knowledge and the reflective handling of it.

Rather, the focus is on the activation of existing explicit and implicit everyday knowledge. Finding a solution to a problem can therefore only be described as creative in a limited sense, but not in the radical sense, for example, when Joseph Schumpeter (Citation1943/2013) speaks of the creative destruction by the entrepreneur in the process of economic innovation, or Thomas Kuhn (Citation1962/2012) of the paradigm shift in science, or when Paul Feyerabend (Citation1975/1993) makes a plea against method in order to increase the chances of knowledge progress. In these cases, old practice and old knowledge must be questioned and overcome to be replaced by new practice and new knowledge. In the special awarding of this very creative force, Western culture still differs from the culture of East Asia (cf., Münch, Citation2001). The top position of the East Asian countries in the PISA ranking of problem-solving competence therefore does not prove that their educational regime is also a model for the stimulation of creativity in the radical sense. The most obvious explanation for the fact that the East Asian countries, as in reading, mathematics and science, are also on top of the PISA league table when it comes to problem solving is, therefore, that they are more accustomed to taking tests, attach greater importance to the test and simply make more effort, which is encouraged by singing the national anthem before the test.

The fact that the one-sided focus on the reproduction of what has been learned and its application to solve problems hinders creativity and innovation in the radical sense has, however, been lamented since the 1990s (Zhao, Citation2014). Kai-ming Cheng (Citation2011) notes, for example:

“Teaching and learning, especially in secondary schools, still follow the examination syllabi, and school activities are oriented toward exam preparation. Subjects such as music and art, and in some cases even physical education, are often not offered because the exams do not cover those subjects. Students work long hours every day and into the weekends, often taking additional exam-prep classes. As noted earlier, private tutorials, most of them profit-making, are widespread, almost a household necessity.” (p. 30)

In response to criticism referring to too little emphasis on creative learning at school, reforms have been undertaken and are still in process in various East Asian countries (cf., Kennedy & Lee, Citation2007, chapters 7, 8). The government of Singapore, for example, has geared its teaching guidelines toward promoting creativity and innovation. A number of catchwords express this new objective: the “thinking school”, “the IT master plan”, “national education”, “content reduction”, “project work”, “innovation and enterprise”, “teach less, learn more” (Deng & Gopinathan, Citation2016, pp. 457–458; cf., Kennedy, Citation2013). The aim is to consolidate Singapore’s position of a so-called high-performing education system (HPES). However, extensive studies of school practice between 2004 and 2010 by Deng and Gopinathan (Citation2016) reveal that frontal teaching and preparation for performance tests still dominate learning at school and that there is no sign of lessons aimed at stimulating creativity and critical faculties in the radical sense:

“At the policy and rhetorical level, Singapore fits well the description of a high performing system in the HPES literature - ‘unleashing’ the power of ICT for learning … and promoting a ‘thinking pedagogy’ for ‘deep learning’ … However, as noted earlier, at the classroom level, meaningful use of ICT, teaching for deep understanding, and opportunities for critical and creative thinking are still very limited and uncommon.”. (p. 461)

Deng and Gopinathan conclude from this finding that the PISA test must have a high affinity to the learning regime that still prevails in Singapore, as in the other East Asian countries, and which particularly rewards exam-oriented learning, but not critical faculties and creativity (pp. 463–464; cf., Koh et al., Citation2012; Lim, Citation2010). For Deng and Gopinathan, the high performance of these countries in tasks that require problem solving, as put forward by the OECD, is only proof that PISA tests standardized problem solving, but not creative thinking in the radical sense (p. 464; cf., Zhao, Citation2014). Further evidence confirming that the PISA test is at odds with radical creativity and critical thinking is provided by a study which proves in a regression analysis that conservatism (a preference for traditionalism, conformity and security) is the best predictor of higher PISA test scores in all three tested disciplines (Benoliel & Berkovich, Citation2018).

Ma et al. (Citation2013) have proven that learning in control mode pays off in the PISA test. We understand this learning strategy as representative of Confucian learning as scrutinized so far. In their search for explanatory factors for the PISA success in 2009 of six East Asian school systems—Hong Kong (China), Japan, the Republic of Korea, Shanghai (China), Singapore and Taipei (Taiwan)—using a two-level hierarchical linear model, the authors identified two factors that proved to be the most effective in all six countries for reading as well as for mathematics and science: school discipline as a school characteristic and the application of the control strategy along with using meta-cognitive skills in learning as a student characteristic. Both features characterize an educational regime that places the greatest emphasis on disciplined and controlled learning. School discipline means that the teachers have strict control over what is taught, while the application of the control strategy means learning in examination mode, i.e., learners continually check their own learning progress. This is also closer to the exam situation than mere memorizing or elaborating, both of which have proven to be less effective. It is clear that these two factors reward the reproduction of a knowledge system more than its questioning. Learning in the control mode may be close to what is characterized as combination of motivation to learn, memorization and seeking understanding in deep instead of surface learning as reason for the extraordinary performance of East Asian students (Kember, Citation2016). Further evidence for achieving in the PISA test through learning controlled by teachers is provided by the fact that teacher-directed but not enquiry-based learning is correlated with higher PISA science scores (OECD, Citation2016, Figures. II.2.13, II.2.14, II.2.19). As Komatsu and Rappleye (Citation2017b) show, these results prove that the PISA test favors a learning strategy which contradicts the promotion of student-centered learning (see also, Sjøberg, Citation2018). According to their wording this is teacher-centered learning II as against student-centered learning I (see also, Seo et al., Citation2005). However, as Jerrim et al. (Citation2020) show for England, inquiry-based teaching, is not effective in generating higher examination scores in general, beyond PISA. This finding reveals a tension between the two, and PISA seems to favor the examination mode of learning.

Further evidence for an insufficient representation of creativity in the more radical sense in PISA is provided by a look at the Global Creativity Index. Success in the PISA test is at odds with a leading position in the Global Creativity Index (Florida et al., Citation2015; Tienken, Citation2008). Western countries in the midfield of the PISA test occupy the top positions in the Global Creativity Index, while the East Asian leaders in the PISA league table are only found in a midfield position of this index with the single exception of the special case of the wealthy city state of Singapore . We may object that this effect is due to a typically Western understanding of creativity in the Global Creativity Index. Nevertheless, this type of creativity stands for centuries of progress in science and technology so that a turn away from it by adopting the Confucian learning regime would bring this development to a halt. This assessment of the Confucian learning regime does by no means deny that this regime has its own merits and has made its contribution to the remarkable catch-up technological and economic development of East Asia. However, there are good reasons to take this effect as an indicator of incremental innovation and catch-up economic development but not as an indicator of economic development based on radical innovation. As far as we are interested in radical innovation there must be enough space for explorative and experimental learning and critical argumentation, as paradigmatically explained by John Dewey (Citation1897). And there is reason for concern that an undisputed worldwide rule of the PISA learning regime undermines the institutional basis of a creativity-supporting learning culture in the tradition of the Western Enlightenment (Grey & Morris, Citation2022; Tienken, Citation2017).

4. Learning strategies, educational achievement and closing of achievement gaps: A multilevel regression analysis

4.1. Theory

As we have learned, according to Weber and also the current state of research, the basic difference in the idea of learning and its link to creativity between Western Enlightenment and Eastern Confucianism can be spelled out in an ideal-typically pointed emphasis as follows: (1) Learning in the mode of Western Enlightenment means exploring new ways of thinking with the ability to deviate from existing knowledge to replace old thinking with new thinking in a dialogical relationship between student and teacher, preparing for mastering the world in a society of self-responsible individuals. Creativity here is destruction of existing knowledge and practices and their replacement by new ones. This furthers first of all radical innovation in a revolutionary process. (2) Learning in the mode of Confucianism means extending existing knowledge with the ability to adapt it to new situations and challenges to harmonize old thinking with new thinking in a respectful relationship of questions and answers between student and teacher, preparing for the appropriate embedding of the individual in society so that harmony is maintained. Creativity here is the evolutionary development of existing knowledge. This allows first of all for incremental innovation in an evolutionary process.

For Weber, these are two opposing types of rationalism in approaching the challenges of human life in society. It is established thinking that modernity first emerged in Europe based on the Western type of learning with a history that reaches from Hellenic philosophy to the Enlightenment that implies a dynamically changing world driven by the permanent replacement of old knowledge by new knowledge. This does, however, not preclude, that there has always been a counterpart to the revolutionary overturn of knowledge in the West itself. Revolutionary dynamics has always been in interaction with its other, that is incremental innovation in the sense of extending existing knowledge. With the rise of East Asia to the position of outstanding achievement in not only economic but also scientific and technological terms, evolutionary development of knowledge and incremental innovation have gained new recognition as another type of modernity. We see here in the context of learning, creativity, knowledge creation and innovation what Shmuel Eisenstadt (Citation2002) has called multiple modernities. And it might be characteristic for the future that East and West complement each other with two types of modernity both needed for the development of knowledge.

Looking at international comparative tests of learning outcomes like PISA, the question is how the two types of learning and creativity outlined so far are represented in these tests. Our hypothesis is that the ranking of East Asian school systems rooted in the Confucian mode of learning on top of PISA says that PISA favors more the Eastern Confucian type of learning than the Western Enlightenment type. A first prove of this hypothesis is our finding in the previous section that problem solving in the PISA test is closer to adaptive learning than explorative learning.

A further proof is that positions in the PISA ranking are not directly reflected in the ranking of the Global Creativity Index. In order, the test this hypothesis further on we look at the disciplinary climate at school and the learning strategies of students as surveyed along with the PISA test. First, we assume that learning at school within the Confucian culture takes place in a disciplinary climate which is stronger than in countries representing the Western culture. The PISA survey asks principals about how far learning is hindered by teacher or student absenteeism and students about their assessment of the disciplinary climate in class. We take these variables as representing the disciplinary climate in class. As already mentioned, the PISA test of 2009 is the only one in which learning strategies were directly focused, which is why we take data from this test wave to examine the effect of disciplinary climate and learning strategies on the PISA score of students (OECD, Citation2010a, pp. 48-52; Citation2010b, 94-98). As the learning strategies are oriented to reading, the reading score serves as dependent variable.

For measuring the disciplinary climate on school level, we use the following variables from the principal survey:

Extent to which student learning is hindered by: Teacher absenteeism: not at all

Extent to which student learning is hindered by: Student absenteeism: not at all

From the student survey an index of the following items is taken for measuring the disciplinary climate in class as experienced by the students:

How often do these things happen in your <test language lessons>? Never or hardly ever, in some lessons, in most lessons, in all lessons:

Students don’t listen to what the teacher says

There is noise and disorder

The teacher has to wait a long time for the students to <quieten down>

Students cannot work well

Students don’t start working for a long time after the lesson begins

(OECD, Citation2008, Q36)

In the 2009 survey, three learning strategies were asked from students: (1) memorization, (2) control and (3) elaboration (OECD, Citation2010a, p. 48). These strategies are defined by the following item parameters:

Student learning strategies: four response categories varying from “almost never”, “sometimes”, “often” to “almost always”

Memorization strategies

“When I study, I try to memorize everything that is covered in the text

When I study, I try to memorize as many details as possible

When I study, I read the text so many times that I can recite it

When I study, I read the text over and over again”

Elaboration strategies

“When I study, I try to relate new information to prior knowledge acquired in other subjects

When I study, I figure out how the information might be useful outside school

When I study, I try to understand the material better by relating it to my own experiences

When I study, I figure out how the text information fits in with what happens in real life”

Control strategies

“When I study, I start by figuring out what exactly I need to learn

When I study, I check if I understand what I have read

When I study, I try to figure out which concepts I still haven’t really understood

When I study and I don’t understand something, I look for additional information to clarify this”

(OECD, Citation2012, Tables 16.12 to 16.14, p. 293).

A factor analysis reveals, however, that the items regarding learning strategies entailed in Question no. 27 of the student questionnaire are loading on four factors. In order to discriminate clearly between different learning strategies, we therefore include four strategies in our analysis. The first two items of what is called memorization strategy in the OECD report we also take as memorization strategy, the second two we call internalization strategy. Of the OECD’s elaboration strategy, the second, third and fourth items constitute the transfer/elaboration strategy while the first item is deleted in our analysis. The control strategy in our analysis consists of the second, third and fourth items of the OECD’s control strategy.

The items representing the memorization strategy and similarly the items of the internalization strategy unmistakably show students who prepare directly for a test in which they have to reproduce what is written in given texts. Control strategies are also directly oriented to preparing for a test. The students are focused on what exactly is required by the test, what of this required knowledge they already master and what they do not yet master and must concentrate on. This is a learning strategy which is typical for test takers, and which is favored by standardized tests. And as tests have to be all the more standardized the larger the number of students, schools and countries who have to be compared in their competences, this kind of test regime should reward control strategies of learning. The more often such standardized tests are conducted, the more learning takes place as direct preparation for the exam. It is learning in the examination mode complemented by teaching to the test.

In contrast, the transfer/elaboration strategy takes students away from direct exam preparation. It opens new avenues of extending knowledge but entails the danger of dealing with things that are not directly related to the test and may even hinder a straightforward test preparation. We assume that this learning strategy is not conducive to excel in standardized tests like PISA. Taking into account the outstanding role of examination and preparation for exams in the imperial Confucian tradition of recruitment to civil service as well as in its modern counterpart of allocating personnel to occupational positions we may postulate: It seems to be fair to speak of a kind of “elective affinity” between the regime of standardized testing as globally disseminated by PISA and the renaissance of Confucian learning in East Asia. In contrast, what is called “elaboration strategy” in the PISA survey of 2009 or transfer/elaboration strategy in our analysis looks more like learning according to the idea of exploring new fields whose success cannot be predicted exactly. Therefore, it is not a wise strategy of preparing for a standardized test. Here, we may speak of a conflicting relationship between PISA and the Western tradition of explorative learning as paradigmatically explained by John Dewey (Citation1897).

If the hypothesis holds that PISA favors the adaptive Confucian type of learning, particularly control should be more effective in raising PISA scores than transfer/elaboration , not only in East Asian countries but also in Western countries. We therefore look at the effects of these learning strategies in two Eastern and two Western countries: South Korea and Singapore, the United States and Canada. Furthermore, explorative learning and radical innovation might be achieved more by elites but less by the broad mass of students, while adaptive learning and incremental innovation might be more inclusive and attainable for all. We should see this difference in the effect of individual student and average school socioeconomic status on PISA scores in comparing the two Eastern and two Western countries and in looking at the effects of different learning strategies. The question therefore is, how far the emphasis on adaptive learning can reduce the impact of student and school socioeconomic status on PISA scores. If there is an effect, focusing on adaptive learning strategies can help to reduce the impact of socioeconomic family background on learning outcomes everywhere, thus providing for quality and equity.

We carry out a multilevel regression analysis focused on the effect of disciplinary climate and learning strategies on educational performance in comparison to the socioeconomic status of students and schools. The question is whether the disciplinary climate in class and certain learning strategies do not only help to improve PISA outcomes but also to reduce performance gaps based on socioeconomic family background. We compare the United States, Canada, Singapore and South Korea to highlight the differences between highly innovative liberal and highly disciplined Confucian education regimes. The choice of the two Western and two Confucian countries is based on their difference in socioeconomic homogeneity measured by the Gini index of household incomes. Other things being equal, we assume that the impact of socioeconomic background on the PISA score of students should be higher in a country of higher socioeconomic inequality. Of the four countries chosen for our analysis, of the two Western countries, the United States features a much higher socioeconomic inequality than Canada, of the two Confucian countries, Singapore features a much higher socioeconomic inequality than South Korea. According to World Bank data respectively Singapore Department of Statistics data the Gini index of household incomes in 2009 was 40.6 for the United States, 33.8 for Canada, 47.8 for Singapore and 32.3 for South Korea (Singapore Department of Statistics, Citation2010; World Bank, Citation2022). For having these contrasts in social inequality in the analysis, we select these two Western and two Confucian countries. This is also the reason why we could not take China for representing the Confucian culture. China is not included as a whole country in the PISA test of 2009, but only with metropolitan areas, that is Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Macao which are not representative for China and for which the Gini index of China would not apply directly.

4.2. Data and methods

The multilevel regression models conducted in this step of our analysis comprise of two levels. The first features variables on student level, the second on school level. More precisely, we employ a random slope, random intercept multilevel linear regression model (Snijders & Bosker, Citation1994, pp. 120–124). We applied Snijders and Bosker’s (Citation1994) R2 to calculate the goodness-of-fit of our models. Z-standardization was applied to ensure comparability of effect sizes, and student weights, provided by the OECD, were included to compensate for missing observations on student level. For descriptive statistics and regression diagnostics see appendices A and B.

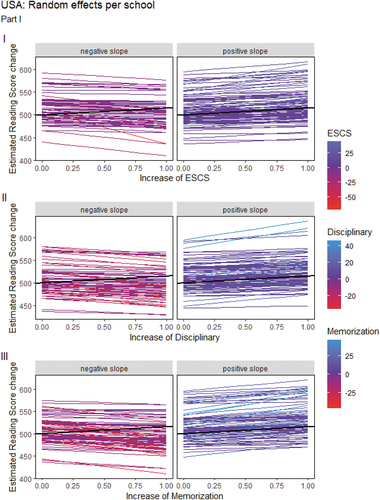

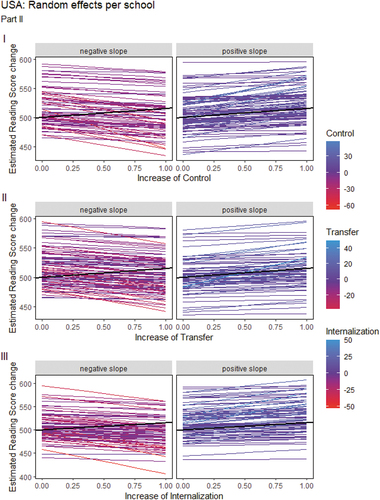

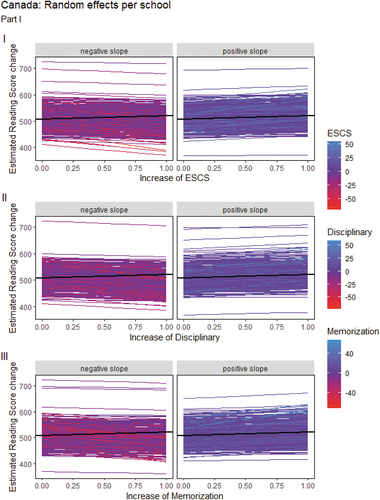

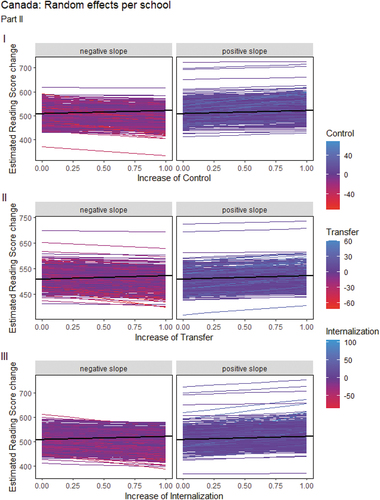

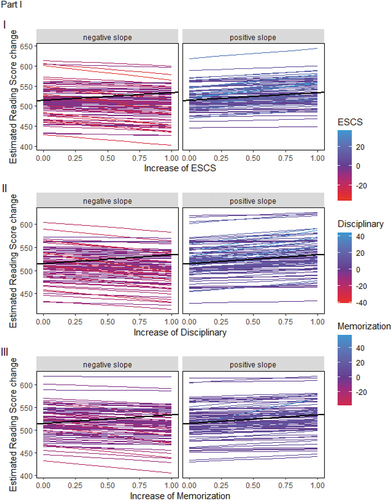

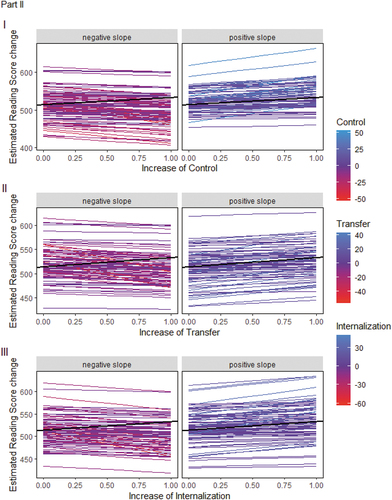

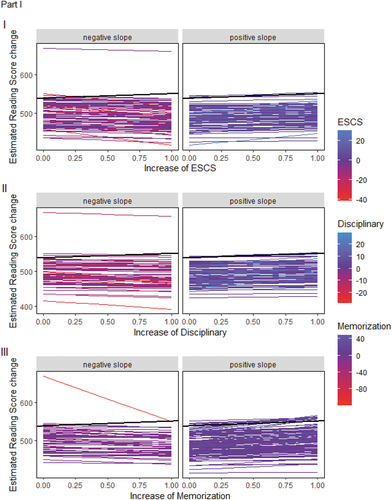

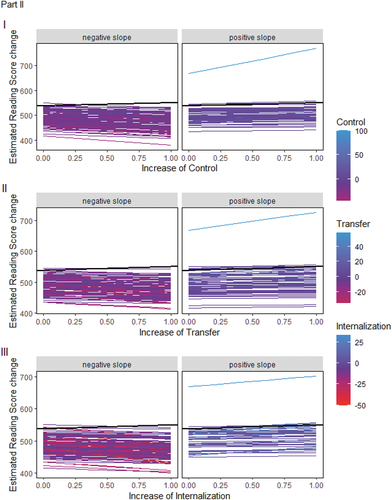

Our regression analysis comprises of seven models. We begin with variables on the student level, continue with adding variables on the school level, go on with controls for ESCS, disciplinary climate and learning strategies, and end with including interactions between the four learning strategies and the student ESCS in the full model. Model one addresses the students’ index of economic, social and cultural status (ESCS). The “ESCS is a composite score built by indicators of parental education, highest parental occupation, and home possessions including books” (OECD, Citation2017, pp. 339–340). The second model estimates the association between students’ learning strategies and the PISA reading score, namely memorization strategies, control strategies, transfer/elaboration strategies, and internalization strategies. The third model introduces variables regarding disciplinary climate and the mean student ESCS value per school. Disciplinary climate is constructed from items that measure whether students listen to the teacher or not, noisiness and disorderliness in class, the time it takes the students to be quiet and to participate in the lessons and the students’ working conditions (OECD, Citation2017, p. 314). At the same time, the average ESCS is a measure of social inequality between schools. Model four includes all variables and controls for the ESCS, and adds ESCS as random effect, meaning that the slope of ESCS could vary between schools.Footnote1 For better interpretation, the random effects are depicted as slopes in appendix B. Model five includes the random effect of disciplinary climate in addition to ESCS, model six the random effect of the four learning strategies in addition to ESCS and disciplinary climate. Model seven is the full model and includes additionally the interaction of the four learning strategies with the ESCS as fixed effects and the six random effects introduced in models four to six. Results are provided in Tables .

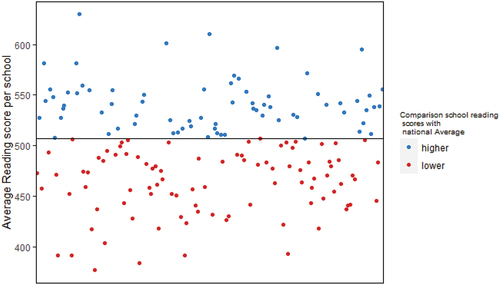

Table 1. PISA reading score 2009, United States

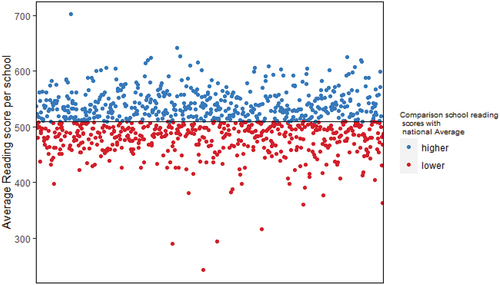

Table 2. PISA reading score 2009, Canada

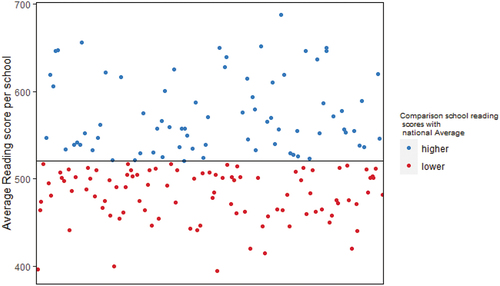

Table 3. PISA reading score 2009, South Korea

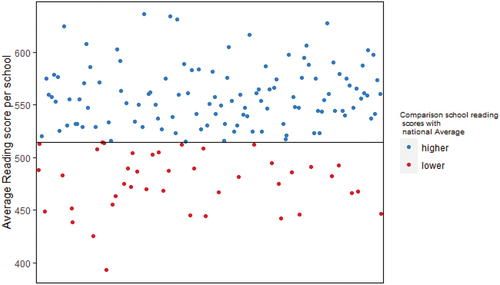

Table 4. PISA reading score 2009, Singapore

4.3. Results

Beginning with model one, we see positive, highly significant (p < 0.001) and robust associations of the students’ ESCS with the PISA reading score in all four countries. The strongest association between student-level ESCS and the PISA reading score is given in the two countries with highest inequality of household incomes according to the Gini index, namely in the U.S. and in Singapore. (β = 23.39*** and β = 22.57***). That means, with one unit of standard deviation in the student-level ESCS the PISA reading score rises by 23.39 respectively 22.57 points. The student-level ESCS explains 10% variance on student level and 58% on school level in the U.S., 13% variance on student level and 43% on school level in Singapore. The association remains robust after controlling for all other fixed effects and after including all random effects in the full model. The student-level ESCS is also associated with the PISA reading score with strongest significance and highest robustness in Canada and South Korea, but yields lower effect strength and explained variance, presumably due to lower inequality of household incomes (β = 16.49*** and β = 10.63***; explained variance on student level 6% and 4%, on school level 34% and 27%).

Model two shows strong, highly significant, and highly robust associations of the control strategy of learning with the PISA reading score in all four countries (U.S. β = 35.28 ***, Canada β = 35.39 ***, South Korea β = 21.2 ***, Singapore β = 27.47 ***). Except for a positive significant and robust association of the internalization strategy with the PISA reading score in the case of South Korea, all other learning strategies are either significantly, negatively, and robustly associated or not significantly associated with PISA reading scores. Nevertheless, the internalization strategy shows a smaller effect size throughout the models. The explained variance of the four learning strategies altogether—taking into account the mostly negative association of three of them—is 18% on student level and 35% on school level in the U.S., 21% and 36% in Canada, 21% and 36% in South Korea, and 15% and 35% in Singapore. Hence, except for the internalization strategy in South Korea, of the strategies which have often been associated with Confucianism only the control mode of learning helps to achieve in PISA. More importantly, this holds also true for the two Eastern and the two Western countries. In contrast, we witness that the transfer/elaboration strategy is significantly, negatively, and robustly associated with PISA achievement scores. This implies that a more explorative kind of learning compared to the control strategy is associated with lower PISA-scores. As this learning strategy is closest to the learning type of Western Enlightenment, we may conclude that PISA rewards the Confucian and punishes the Enlightenment type of learning.

In model three, the school ESCS and, except for South Korea, the disciplinary climate but not the variables regarding student and teacher absenteeism show a significant and robust association with PISA reading scores, most so in the U.S. and in Singapore, followed by South Korea regarding school ESCS but not disciplinary climate, least so in Canada. We must consider here that South Korea is characterized by high-school discipline in general, which is why our school discipline variable is neither robust nor yields effects significantly different from zero. The explained variance in the PISA reading score increases, most so in the U.S. and in Singapore, less so in South Korea and Canada. Again, this result is linked to higher income inequality in the U.S. and in Singapore compared to South Korea and Canada.

Controls of ESCS, disciplinary climate and learning strategies in models four to seven add to explained variance in PISA reading scores in all four countries with highest explained variance again in the two countries showing highest income inequality. This is especially caused by the inclusion of random effects, which increase the variance explained on student level significantly, but reduce the explained variance on school level slightly with the exception of South Korea. This is attributable to one outlier school included in South Korea, which combines an extremely high PISA reading score as intercept with a positive slope. This is especially true when random effects of learning strategies are included.

In every country under scrutiny, we see positive values for the random effects included in our models. This indicates that with increasing values for ESCS, disciplinary climate, and learning strategies, the differences between schools increase. In other words: we witness that the effects of social inequality increase between schools, but the effects within schools (fixed effects) remain stable. This means that despite differences among schools, which get even stronger when learning strategies are applied, disciplinary climate and differences in ESCS are considered, the effects of social inequality and control strategies remain stable. Regardless of which school a student goes to in the four countries, the control strategy of learning ideally associated with Confucianism significantly increases PISA scores everywhere. At the same time, our result shows that there are stable effects of social inequality regardless of whether a student goes to a school that has a high ESCS or low ESCS on average. Even more, the disadvantage tends to increase the higher the average ESCS of the school and the lower the ESCS of the students at these schools.

Turning to the explained variance in the full models, we witness that 51% variance on student level and 91% variance on school level is explained in the U.S., 54% and 85% in Singapore, 59% and 62% in Canada respectively. Due to the outlier in South Korea, explained variance is at 31% on student level and 87% on school level in model five to change in models six and seven to 50% on student level and 26 respectively 27% on school level. Nevertheless, the school ESCS shows a significant and highly robust association with the PISA reading score which is nearly as strong as in Singapore, indicating considerable stratification of schools according to average school ESCS and average PISA reading score.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The Confucian type of learning and creativity is different to a type of learning and creativity that originated in Western culture and culminated in the Enlightenment (cf., Münch, Citation2001). It favors incremental innovation, whereas the Enlightenment type of learning enables radical innovation. On the one hand, learning shall result in the self-improvement of the individual, on the other hand, it shall make the single individual an independent person who can reflect and judge critically any claims of knowledge validity. In order to acquire this capacity, learning has to provide chances of creative exploration of new ways of thinking, experimentation and critical argumentation in collaboration with schoolmates. Yet our findings imply that this type of learning is incompatible with a regime of learning that puts primary emphasis on monitoring through extensive testing and is even punished by lower PISA scores. As it is established on the basis of making achievement in the PISA test the benchmark for best performing school systems, schooling systems with emphasis on creative, out of the box learning will gain lower scores compared to schooling systems which rely on the control-strategy of learning and will become a negative foliage for educational reforms according to the logic of “naming and shaming” introduced by the OECD PISAtest. At the same time, the Confucian mode of learning and creativity is established as role model for schools worldwide.

As our study shows, learning in the control mode is the one and single mode of learning which is significantly positive in its effect on PISA reading scores throughout all countries involved and throughout all models. The memorization and internalization strategies are significantly and negatively associated with PISA reading scores throughout all countries and models except for the internalization strategy in the case of South Korea. Possibly, the students’ understanding of internalization is close to the control strategy in this country. Transfer respectively elaboration strategies are closer to creativity and radical innovation in the Western Enlightenment sense but are significantly negative in their association with PISA reading scores in all four countries, indicating that PISA does not reward creativity in learning in the more radical sense.

What, therefore, remains as the single significantly positive and robust learning strategy is learning in the control mode. We may interpret this strategy as learning in the examination mode. This is a type of learning which includes the procedure of an examination directly in the learning process. We think that this type of learning keeps creative exploring in narrow limits and rewards unquestioned reproduction of the existing order of knowledge. Remarkably, this holds for the two liberal Western countries and the two East/Southeast Asian countries in our analysis alike. This interpretation of our results is supported by the significantly positive and robust effect of the disciplinary climate on PISA scores in all four countries. Apparently, Western students adopt the Eastern mode of learning to perform best in the PISA test. This is true, even after controlled for the student’s socioeconomic status and the differing effects between schools, as indicated by the random effects in our models.

Statistically, we see significant and robust associations of socioeconomic status of individual students and schools with PISA reading scores with considerable explained variance in this score throughout all countries and models, most so in the U.S. and in Singapore, the two countries showing highest income inequality. Disciplinary climate (except for generally highly disciplined South Korea) and learning in control mode add explained variance on the student level but are partly absorbed by socioeconomic status. That is, independent of the respective school under observation, better off students might be more disciplined and apply the more successful learning strategies to achieve in the PISA test. Therefore, we should not expect more than a small significant closing of the socioeconomic achievement gap by exerting more disciplinary pressure and applying the most successful learning strategies across all socioeconomic classes. Despite all efforts, the impact of students’ socioeconomic status on their educational performance has not changed in five decades (Chmielewski, Citation2019). Socioeconomic status is important for PISA achievement in all four countries, particularly in the U.S. and in Singapore, less so in South Korea and in Canada. The better situation in Canada and South Korea is, however, not so much due to a more favorable disciplinary climate and better learning but due to lower social inequality according to the Gini coefficient, and, in Canada additionally, due to a highly selective migration policy so that there is no significant difference between migrant and native students. And we have to take into account that in Canada, as in the U.S., the impact of family background might be underestimated because of the relatively low coverage of 15 years old youth in the test. It is at 83.6% in Canada and 82.2% in the U.S., as compared to 87.9% in South Korea and 94.3% in Singapore in 2009 (cf., Anders et al., Citation2019).

We must also take reliability problems of PISA data into account (Jerrim et al., Citation2017), which are accountable to multiple imputations of the data, the sampling procedure with poor coverage (especially in Canada and the U.S.) and model violations of the underlying latent variable model. The multiple imputation of missing data rests on the family background of the students as well as on the main characteristics of the schools which they attend. In tendence, such an approach might result in smaller deviances between students and thus larger clustering within the classes and schools in regards of the missing values. Additionally, low coverage yields the danger to miscalculate the PISAscores used as dependent variable. Due to this imputation problem, the ESCS measure might be biased to a large extent. Therefore, it is discussed whether the ESCS is appropriate for measuring the socioeconomic status of students (Avvisati, Citation2020; Jerrim & Micklewright, Citation2014; Rutkowski & Rutkowski, Citation2013). An alternative is the international socioeconomic index of occupational status (ISEI) of the father or both parents which is part of the ESCS. According to our previous investigations, differences in outcomes are small, however. And for highly developed countries the complete ESCS seems to be the right index (Muench & Wieczorek, 2022). In combination, both problems yield the possibility of underestimation of the impact of family background on PISA scores in the cases of Canada and the U.S. This means that there might be even greater support for our argument.

Despite these methodological problems, we think that our study contributes to the critical reflection and discussion of the learning regime promoted by PISA (cf., Komatsu & Rappleye, Citation2021). In order to further prove the robustness of our findings we need more studies that make use of other data such as TIMSS (Third International Mathematics and Science Study) and PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study), scrutinize other PISA test years and include other relevant variables in the analysis.

The practical implication of our study for school policy is a warning against an undisputed subjection to a uniform control regime of education as promoted by PISA all over the world (cf., C. Tienken, Citation2017; Zhao, Citation2014). Instead, we want to stress that there are two types of learning, creativity and innovation, one more represented by the Western Enlightenment, the other one more represented by Confucianism. Both complement each other as we need both, radical and incremental innovation. The wellbeing of humankind depends on cultural diversity as much as on biodiversity. International benchmarking through standardized testing like PISA replaces cultural diversity by uniformity. We, therefore, should end assessing school systems, schools, and students with one-size-fits-all standardized tests of this kind. Everybody responsible for education should know that learning is more than preparing for standardized tests. This holds particularly for the protagonists of this kind of education, particularly involving the OECD’s PISA network, the education and testing industries, consultancies, philanthropic foundations, advocacy groups, policy makers and administrators working together in this project (Münch, Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Muench

Richard Muench is Senior Professor of Social Theory and Comparative Macrosociology at Zeppelin University, Friedrichshafen, Emeritus of Excellence at Otto Friedrich University, Bamberg, Germany, and member of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences. He has been a visiting professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, several times, and co-editor of several sociology journals. In 2018, he was awarded for his lifetime achievements by the German Sociological Association. His research focuses on the study of social change in the context of globalization, European integration, and national traditions, with a recent focus on education, schools, and teaching in the competitive state, academic capitalism, and academic careers.

Oliver Wieczorek

Oliver Wieczorek graduated from Otto-Friedrich University, Bamberg, Germany, with a BA, an MA, and a Ph.D. in Sociology. He has been researcher at Otto-Friedrich University, Bamberg, Germany, Zeppelin University, Friedrichshafen, Germany, and is currently senior researcher at the INCHER at the University of Kassel, Germany. His research focuses on the sociology of science and the sociology of secondary and higher education.

Robin Gerl

Robin Gerl graduated from University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany, with a BA in Social Science, and a MA in Empirical Political and Social Research. He has been a researcher at the University of Stuttgart and the Zeppelin University, Friedrichshafen, Germany. His research focuses on empirical methodology and the sociology of education.

Notes

1. Values greater zero indicate that the range of values “spread” across the schools, whereas values smaller zero indicate that with increasing values of the independent variable, the values of the dependent variable get more similar. For example, a positive value for ESCS on school level indicates that for low ESCS values, PISA scores would be more similar compared to higher ESCS values. This could be read that with increasing ESCS differences, the PISA scores are more unequally distributed among schools.

References

- Anders, J., Has, S., Jerrim, J., Shure, N., & Zieger, L. (2019). Is Canada really an education superpower? The impact of exclusions and non-response on results from PISA 2015. Working Paper, No. 19-11. UCL Institute of Education.

- Avvisati, F. (2020). The measure of socio-economic status in PISA: A review and some suggested improvements. Large-scale Assessments in Education, 8(8), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-020-00086-x

- Barber, M., & Mourshed, M. (2007). How the worlds’ best-performing school systems come out on top. McKinsey & Company.

- Benoliel, P., & Berkovich, I. (2018). A cross-national examination of the effect of the Schwartz cultural dimensions on PISA performance assessments. Social Indicators Research, 139(2), 825–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1732-z

- Boman, B. (2022). Educational achievement among East Asian schoolchildren 1967–2020: A thematic review of the literature. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 3, 100168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2022.100168

- Cheng, K. M. (2011). Shanghai: How a big city in a developing country leaped to the head of the class. In M. S. Tucker (Ed.), Surpassing Shanghai: An agenda for American education built on the world’s leading systems (pp. 21–50). Harvard Education Press.

- Chmielewski, A. K. (2019). The global increase in the socioeconomic achievement gap, 1964 to 2015. American Sociological Review, 84(3), 517–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419847165

- Deng, Z., & Gopinathan, S. (2016). PISA and high-performing education systems: Explaining Singapore’s education success. Comparative Education, 52(4), 449–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2016.1219535

- Dewey, J. (1897). My pedagogic creed. School Journal, 54(1), 77–80. https://dewey.pragmatism.org/creed.htm

- Eisenstadt, S. N. (Ed.). (2002). Multiple modernities. Routledge.

- Elman, B. A. (2013). The civil examination system in late imperial China, 1400–1900. Frontiers of History in China, 8(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.3868/s020-002-013-0003-9

- Feniger, Y., & Lefstein, A. (2014). How not to reason with PISA data: An ironic investigation. Journal of Education Policy, 29(6), 845–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2014.892156

- Feyerabend, P. K. (19751993). Against method. Verso.