Abstract

The presence of gender bias in school textbooks is a global educational challenge often associated with the hidden curricula. However, while the problem has been almost entirely attributed to general education systems little empirical data exists when it comes to higher education. The purpose of this study is, therefore, to shed light on the uncharted terrain of gender representation in textbooks and learning materials in the higher education context. The study combined quantitative and qualitative content analysis approaches to investigate the magnitude of gender bias. The findings generally show considerable male domination in language use (proper and common nouns and pronouns) and portrayal of actors in prestigious professions like scientists, medical doctors, managers, and top government officials while women are depicted as company employees, school psychologists, and fashion models in pictures and other illustrations used in the textbooks. Finally, the article suggests areas for further research and policy interventions.

1. Introduction

Curriculum and textbooks are important avenues of maintaining and reproducing structural inequalities, mainly based on class, race, ethnicity and gender differences and intersections of gender with other social markers (e.g., Southworth et al., Citation2020). Over the past several decades, studies that attempt to unravel the nature and magnitude of gender bias consistently reported that curriculum and textbooks are indeed used to perpetuate patriarchy through inculcating male superiority with the help of school textbooks while relegating women in the fringes of societal life (e.g., Southworth et al., Citation2020). This trend seems consistent across nations despite the geographical and cultural differences (for example, see, in Mirza, Citation2004; Blumberg, Citation2007; Southworth et al., Citation2020) extending from Africa to the Middle East and Asia; and from Europe to the Americas (see in Blumberg, Citation2007).

The literature on the impact of religion on gender relations, it is argued that gender inequality started with Adam and Eve in the garden of haven (e.g., Gilligan, Citation1982; Burk, Citation2014). It is further stressed that Adam represent men as a head and leader, while portraying Eve as a follower representing women’s subsidiary position as preordained since genesis (Burk, Citation2014) rather than a result of social construction. Since then, societal stereotypes continue to assume subsidiary role in society; and as a consequence, the power relations between the two. In almost all cultures, parents, neighbors, communities and institutions differentially treat boys and girls. Whether it is by sheer reflex or by design, people convey expectations that are consistent with traditional stereotypes (Whiting & Edwards, as cited in Sroufe et al., Citation1996). Scholars from behavioral and social sciences offer theoretical explanations how these differential socializations occur. For instance, behavioral psychologists demonstrate that children learn the differential gender roles specifically assigned to men and women as an outcome of the type of reinforcement (i.e. positive or negative) they receive from parents and significant others in their immediate social environment. For example, daughters experience differential treatment when their parents try to support them in learning how to act and think “like girls,” while at the same time helping their sons learn how to act and think “like boys” (in Wood, Citation2009). In the process, boys and girls internalize the deeply ingrained values, norms, and behaviors society expects of them. At school, the process of gender socialization continues to be unabated with renewed vigor involving more agents. Teachers, for their part, inculcate culturally dominant gender norms through activities and tasks while in class or outside the classroom. Sroufe et al. (Citation1996), in this connection, find that teachers assign boys to do manual activities like moving tables and desks while girls were given the task of decorating and cleaning. These findings fit very well into functionalists and Marxists perspectives that school as institution is responsible in maintaining the dominant culture (Bourdieu & Passeron, Citation1977; Giroux, Citation1983) through what came to be known as hidden curriculum. By focusing on textbooks, we try to unpack how hidden curriculum operates to perpetuate patriarchy in Ethiopian higher education context. In concrete terms, the findings existing studies (e.g., Gebremedihin, Citation2007; Yayeh, Citation2019) conducted in Ethiopia show that there is a considerable magnitude of gender bias in primary and secondary school textbooks that calls for further investigation if similar gender bias exists in textbooks or learning materials at university level. Furthermore, given Ethiopia has the lowest literacy rate (51.8%) in sub-Saharan Africa which is 65.6% (World Bank, Citation2020), and low educational attainment and higher education participation rates (10.2%; MOE, Citation2018), as well as low female labor force participation, it is in order to argue that very few women had the chance to embrace liberal gender-role attitudes that disregards social norms and cultural taboos associated with cross gender career or professional choice among women. This might undercut the potency of interactionist view of resistance (Giroux, Citation1983) which posits that children may not fall victim of the hidden curriculum or a gender biased curriculum or textbooks since they are not passive recipients of information, rather they are active in creating and recreating discourse the interaction process, since studies indicate (e.g., Semela, Citation1997, Citation2007; Semela & Miethe, Citation2021) that girls and women in Ethiopian universities still subscribe to traditional roles that makes it hard for them to contradict their own internalized belief systems.

In this article, we attempt to map the change and continuity in terms of keeping the gender balance in developing curriculum and textbooks from primary to higher education. In particular, we explore how much and in what ways gender inequality is “hidden” in textbooks to perpetuate existing unequal gender power-relations through prescribed curricular materials. We would argue that due to the possible effect of gender-biased curriculum materials and textbooks could have in shaping students’ academic and career choice, focusing on first-year students is important to lessen the impact by introducing appropriate reform measures. This paper intends to find out whether women and men are unequally represented in Communicative English textbooks through empirical evidence that shows how the hidden curriculum operates the Communicative English Textbooks that are currently in use. In addition, the evidence we are looking for should show the magnitude of gender bias in gender representation in text, pictures or other forms of textual materials. To that effect, we set out to answer the following specific questions:

How fair the communicative English textbooks are with respect to keeping the balance in gender representation in language use, portrayal of pictures and illustrations in passages, stories and dialogues?

Are the textbooks gender responsive in terms of assigning occupational roles, firstness and depicting gender power relations?

Is there gender dominance or hegemony in first-year Communicative English textbooks?

2. Significance of the study

The study is expected to make several contributions. First, it serves as feedback for curriculum experts, textbook and teaching material writers, editors and educational policy makers. Very specifically, study will help the aforementioned stakeholders to identify factor which affect quality of syllabus and the teaching materials. And, it shows areas where teaching material designers need to consider in ensuring fair gender representation during preparation. The study will also update educational experts, mass media experts and other concerned individuals about the extent of fair gender representation in university level teaching maters. Likewise, it provides information to university instructors about gender treatment in teaching materials, so that they may be aware and set remedial action for observed gaps.

3. Ethiopian higher education

Before the shift to western, modern education, Ethiopia has an ancient educational system which constituted a higher education component (Amare, Citation1967). With the advent of western-style education in the first decade of the 20th century, however, Ethiopia had launched the first modern school in 1908. Nonetheless, four decades had to elapse until Ethiopia inaugurates its first higher education institution. In 1950, the University College of Addis Ababa (UCAA) was inaugurated as the country’s first ever higher education institution. When UCAA was upgraded to a university status renamed as Haile Selassie I University (HSIU), a decade later it had not yet enrolled women. By the mid-1960s, however, HSIU had managed change the gender mix of its student population by enrolling about 4% females into the overall student population (Balsvik, Citation2005, 21; Semela & Miethe, Citation2021, p. 330).

To be fair, in Ethiopia it is not only in HEIs do females are invisible, but also they are still unequal in proportion at the lower ladders of education. Therefore, the wider gender gap in higher education in Ethiopia did not emerge out of the blue. Instead, the inequality at tertiary level is the continuation of female underrepresentation and underachievement at primary and secondary education even though one can witness the significant improvement over the past three decades in the sheer number of women attending higher education (e.g., Semela et al., Citation2020; Semela & Miethe, Citation2021). However, the question remains, could the quantitative growth in female HE participation represent substantive gender equality? Does the HE system providing equal opportunities for women and men by way of overcoming the impact of hidden curriculum in prescribed textbooks? The present study makes a modest attempt to galvanize the ongoing scholarly debate by bringing up old, yet not adequately answered question: what perpetuate gender inequality in the textbooks and learning materials? Should higher education really be concerned about its curriculum and prescribed learning materials and textbooks? This study may provide a starting point in terms of offering empirical evidence using nationally adopted Freshmen English Language Course textbooks in Ethiopian higher education as an example.

3.1. Education as agent of socialization

In the German educational science literature, two terms often used in connection with what in the English-speaking world refers to as “education”. These terms are Bildung and Erziehung. However, just like education, these terms are associated more broadly with socialization of the child. However, at the same time the terms also represent important differences. In the strictest sense, Bildung is conceived as a deliberately planned system of education designed to educate (i.e. socialize) the child in the formal school system to be an active and useful member of the society. On the other hand, Erziehung goes beyond the boundaries of the narrow school system (or school curriculum) to encompass the child’s learning from parents and extended family, the community, institutions of society (e.g., Church and Mosques, etc.), and the broader national (e.g, culture, economy, politics, geography) and global context in the process of its upbringing (for detailed theoretical analysis, see Dietrich. Citation2015). This implies that Bildung draws its resources from the same source as Erziehung does since, learning experiences and school curriculum draw on the values and norms, and institutions and structures of a given society represents even through the latter characterize the broader process of child socialization. At the same time, the former constitutes clearly stipulated instructional objectives as well as the what, and how of transmitting the desired attitudes, values and norms and knowledge and skills the child should be acquired in schools. As such, formal education (i.e. Bildung), according to Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1997, Citation1977) is an instrument of cultural reproduction that is designed to maintain existing social inequalities, including inequality between men and women (Bourdieu, Citation2003). The process of transmitting these norms and values that perpetuate social inequalities via reproducing culture occur either through openly stated curricular objectives or indirectly through the hidden curriculum.

Durkheim in this vein states, “Society can survive only if there exists among its members a significant degree of homogeneity; education perpetuates and reinforces this homogeneity by fixing in the child, from the beginning, the essential similarities collective life demands” ([1922]Durkhheim, Citation1956, 70). Bourdieu (Citation2003, p. 64) defines education system as “a group of institutional or routine mechanisms by means of which is operated what Durkheim calls, ‘the conservation of a culture inherited from the past”. Endorsing Durkheim, Bourdieu (Citation2003) argues that “educational institutions are given the official mandate to ensure the transmission of the instruments of appropriation of the dominant culture which neglects methodically to transmit the instruments indispensable to the success of its undertaking is bound to become the monopoly of those social classes capable of transmitting by their own means” (pp. 71–72).

In his later writings, Bourdieu (Citation2001) acknowledges the presence of masculine domination in gendered aspect of habitus. He maintains that the educational system, along with the family, the church, and the state, is essential to the reproduction of gender inequality. Herein comes the school curriculum and textbooks as the key elements of a system of education stirring the process of cultural reproduction that ensures the perpetuation of gender hierarchies as “natural” or legitimate not only by men, but also by women. This is how education contributes to the reproduction and legitimation of a cultural system to reinforce masculine privilege (Edgerton et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, Bourdieu draws attention to the traditionally gendered division of labor (e.g., care-giving and service work for women; managerial and technical work for men), and the gendered hierarchy of occupations and professions in the labor market, noting that the degree of feminization of an occupational field is inversely proportional to its power and prestige.

Sociological theories, from structural-functionalism to Marxism and feminist theory concur with the theory of social/cultural reproduction regarding the role of education as a powerful agent of socialization and they also concur with that the process of socialization is not the same for all children as it varies by class/SES and gender among other factors. For instance, for structural-functionalism, education is viewed as instrument of socializing children to fit the demands and expectation of the society in question. And school is considered as a factory that process row materials (in our case row materials being children enrolled into schools). Thus, the role of schools is serving as institutions charged with the responsibility of socializing young people by inculcating the curriculum. Consistently, functionalists view education as an instrument of creating active members (good citizen) of the society not only via its explicit, officially declared curricular objectives, but also through the implicit, officially undeclared hidden curriculum, yet intentionally or unintentionally embedded learning experiences. Marxist sociology for its part considers education as instrument of domination and inequality through unequal distribution of valued resources—for instance, lower class children attend in poorly resourced schools, and taught by unqualified teachers while children of the ruling/middle class children attained high-quality private schools. The interactionist school, on the other hand, stand in contrast with Marxist, and structural-functionalist lines of thinking in analyzing the impact of hidden curriculum including those embedded in school textbooks. One of the widely known theories that subscribe to interactionist school is the theory of resistance. The theory of resistance posit that students are not objects that unquestionably absorb what is taught at school. Instead, they are subjects who not only come to school with their own views and perspectives, but also able actively engage in constructing knowledge and resist external influence (Giroux, Citation1983).

As can be discerned from the forgoing, the study of gender bias in textbooks and curriculum, draw their theoretical backdrops from extant sociological theories advanced to understand the role the education system plays in perpetuating gender inequality by way of differential gender socialization both through decaled curricular objectives and indirectly through openly undeclared, hidden curriculum. However, these theoretical perspectives vary in terms of the robustness of the declared and hidden curriculum in the face of the reflective capacity of agency (the learner). These theoretical standpoints could be broadly classified into two major constellations. One line of thinking comes from theories like structural-functional, Marxist, Feminist theory, and the theory of social and cultural reproduction. The second string of thinking, on the other hand, heavily draws on the theory of resistance. At the core, the two lines of thinking vary in the amount of trust they put on the capacity of agency and structure. While the functionalist and neo-Marxist theories essentially capitalize on the role structure, the theory of resistance put emphasis on the capacity of human agency (e.g., Giroux, Citation1983).

4. Gender biasness and textbooks

Biases are viewed as flaws in judgment associated with different factors, including people’s tendency to draw hasty generalizations based on inadequate data, opinions or beliefs (Georgescu & Bernard, Citation2008; INEE, Citation2010). It also represents distorted images and understandings of people, objects, processes and phenomena. Distorted and unfair characterization and application of a person, situation and idea are common forms of such biases. When such kind of discriminatory characterizations are made on the basis of the individual’s gender, it is usually referred as gender biasness or inequality. According to UNESCO (Citation2009) gender bias is defined as a prejudices or distorted images/characterizations generated by gender difference—they can be positive (generalizing features considered valuable) or negative (generalizing features considered bad or appalling). In the same vein, Mukherjee (Citation2015) defines gender bias as differentiating people as male and female on the basis of gender or gender-based functions and treating them uniquely in the matter of social function, or treating them unjustly in the distribution or burdens and benefits in society. The two definitions commonly portray that gender bias is labeling or associating various characters or roles to individuals on the basis of their gender category.

Gender biasness has a negative impact on both individual and societal development (UNESCO, Citation2009). At individual level, gender biasness may result in low self-esteem and frustrations. At the same time, it hinders boys and girls from achieving their full potential and restricts their roles in society and family because of biased expectations. At community level, gender biasness hinders social harmony and justice. In broader context, it creates negative models for children and young people who are attending schools regularly (Christopher Colclough, Citation2004). Thus, teaching leaning materials, which often guide the teaching and learning process, it is important to stress on ensuring gender equality.

5. Conceptual framework

Gender as one of the social constructs which are described in the contents of learning materials being used at various levels of education. Scholars in the area of gender studies and education (Barton & Sakwa, Citation2012; Joumard, Citation2021; Mustapha, Citation2014) have sorted out different variables which are closely associated with gender representation in teaching materials. The materials are often prone to gender biasness unless considerable attention is given during preparation. On the other hand, such biasness can be depicted and curbed through analyzing the material in the light of key variables associated with gender representation.

Analysis of gender representation in teaching materials usually employs basic variables which demonstrate gender representation. However, scholars often suggest different textbook related variables that are to be used later as categories of analysis. In this regard, Gebremedihin (Citation2007) points out them as occupational role and character trait. Blumberg (Citation2007) lists variables like visibility, stereotyping, balance and selectivity, reality and fragmentation and isolation. On the other hand, the nature of narrations (gender visibility, image and hegemony) and sensitivity of illustrations (occupational roles and power relationships between men and women) are depicted as core variables by Yayeh (Citation2019). Others (Malova, Citation2012; Melesse & Yayeh, Citation2020; Nunno et al., Citation2017), employed five main variables: language use (focusing on gender-related proper nouns, pronouns, and common nouns), illustrations (focusing on visibility), occupational roles, topic domination, and firstness were the variables.

The above authors in the area have presented different variables which are ranging from simple language us to complex social interpretation (hegemony and domination). However, the variables employed for scope of analysis differ among the authors. In the current study, a comprehensive list of variables has been used to disclose the full picture of gender representation in the selected teaching material. The list was developed not only by critically analyzing the meanings of each variables but also through comparing and contrasting the concepts to sort out the overlapping variables. Accordingly, language use, visibility, hegemony, occupational role, topic domination, and firstness were the key variables.

6. Methodology

This study set out to examine the role of hidden curriculum in reproducing existing gender inequalities through examining prescribed textbooks and learning materials currently implemented in public higher education institutions (HEIs). In so doing, it set out to scrutinize the magnitude and nature of gender balance in Freshman English textbooks, titled Communicative English Skills I & II. In line with this, we draw on Sambell and McDowell (Citation1998) definition of “Hidden curriculum” which states: “What is implicit and embedded in educational experiences in contrast with the formal statements in the curricula and the surface features of educational interactions” (pp.391–392). Furthermore, we assessed the two prescribed textbooks to unravel to what extent the declared policies and constitutional provisions that promise to ensure gender equality in education (FDRE, Citation1995) translate into practice through curriculum and textbooks.

7. The teaching material/textbook and sampling

The teaching material was prepared for the course entitled “Communicative English Language Skills I and II” which is being offered as a common course to all first-year students joining Ethiopian universities. It was published by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (MoSHE) in 2019. The material is presented in 170 (78 for part I and 92 for part II) pages with 10 units (5 units each). The rationale behind selecting the material: Communicative English Skills is that language teaching materials often contain various texts and illustrations representing the realities and practices that exist in the society. In addition, the reason for selecting such advanced level (university) teaching material is that gender roles are represented in a more sophisticated way which even demonstrates the perception of higher intellectual/academic community on gender-based issues.

Many scholars (e.g., Fraenkel & Wallen, Citation2006; Gebremedihin, Citation2007; Yayeh, Citation2019) suggest purposive sampling as a widely used technique in the content analysis approach. In the case of this study, too, the teaching material under consideration was not sampled in terms of chapters, passages, stories, and illustrations, or other features. Rather, all parts and contents of the teaching material were taken into consideration for analysis. The material contained five units having various passages, dialogues and illustrations. Accordingly, all the contents in the five units were thoroughly examined based on the identified categories for gender-based analysis. The two English textbooks were made up of 10 units of which each of the courses (I and II) constitutes 5 units.

8. Analytical framework

A volume of research that examined gender bias in school textbooks suggest that the frequently employed methodology has been content analysis (e.g., Wafa, Citation2021; Southworth et al., Citation2020; K. A. Neuendorf, Citation2011; Mirza, Citation2004; Blumberg, Citation2007). For instance, a comprehensive study that explored gender bias in social science textbooks in the U.S, predominantly employed content analysis based on frequency counts (as cited in Southworth et al., Citation2020). Nonetheless, recent studies (e.g., K. A. Neuendorf, Citation2011; Southworth et al., Citation2020) strongly recommend a combination of qualitative and quantitative approach to better explain gender bias beyond frequency counts (Blumberg, Citation2007). In lieu of this, Wafa (Citation2021) employed qualitative and quantitative (mixed) approach. According to her, each textbook was analyzed using both quantitative and qualitative analysis. The quantitative analyses focus on the frequency of visual representation, and gender of authors while the qualitative analyses focuses on description of gender-sensitive language, division of labor, and depiction (brave, intelligent, etc.) and gender of leading characters (Wafa, Citation2021, p. 379). In this study, data generation followed quantitative-qualitative (QUAL-QUANT) procedure where the quantitative data was obtained using frequency count while qualitative data was interpreted in line with Southworth et al. (Citation2020) based on the meanings (the implicit messages it represented or portrayed) from pictures and other images in the textbooks under consideration.

9. Data source, organization, and analysis

In line with the analytical framework discussed above, we generated two separate datasets i.e. quantitative data and qualitative data. Using the course textbooks titled: Communicative English Language Skills: Part I and Part II, we created quantitative data based on content analysis. In so doing, we draw on previous studies conducted in Ethiopian general education textbooks (e.g., Gebremedihin, Citation2007; Yayeh, Citation2019) to select the specific elements that were to be included in the dataset. Accordingly, the units of analysis were extracted from the course materials (textbooks) specifically focusing on textual and visual data which included words, phrases, sentences, paragraphs in passages; and, photographs used in the textbooks as illustrations that reflect gender representations.

9.1. Creating codes and categories

Categories were developed in line with past textbook research in Ethiopian context (e.g., Gebremedihin, Citation2007; Melesse & Yayeh, Citation2020; Yayeh, Citation2019). For instance, Gebremedihin (Citation2007) classified gender representation in school textbooks into two: occupational role and character trait, whereas Yayeh (Citation2019) depicts two major evaluation criteria: nature of narrations and sensitivity of illustrations. In the first criterion, attention was given to issues of gender visibility, image and hegemony. The second criterion taps on occupational roles and power relationships between men and women. More recently, Melesse and Yayeh (Citation2020) used five major categories to assess gender balance in school textbooks. According to these authors, language use (focusing on gender-related proper nouns, pronouns, and common nouns), illustrations (focusing on visibility), occupational roles, topic domination, and firstness were the themes. Similar categories were used to study gender balance in English Language textbooks in many African countries including in Ghana (e.g., Nunno et al., Citation2017), Kenya (e.g., Malova, Citation2012), Nigeria (e.g., Mustapha, Citation2014), and Uganda (e.g., Barton & Sakwa, Citation2012). Nonetheless, none of them attempted to combine quantitative and qualitative data as it helps to complement or triangulate their findings that are based on content analysis (e.g., K. A. Neuendorf, Citation2011; Flick, Citation2014). Heeding to these recommendations, the present study combined qualitative and quantitative data analysis on the textual and visual data obtained using the six categories, namely, language use (focusing on gender-related proper nouns, pronouns, and common nouns), visibility/illustrations, hegemony (feminine and masculine character trait associated various professions), occupational role, topic domination, and firstness (appearing first) in text.

9.2. Data organization and analysis

Once the categories were determined, data gathering and organization were carried out as follows: First, the two textbooks of the course: Communicative English Skills were accessed and made available. Then, a checklist having the main categories and units of analysis was prepared and duplicated. Following that, gender-related contents had been extracted from each unit (passage, dialogues, sentences and illustrations) of the material to the designed checklist carefully. Then, the data was organized in the identified categories for analysis.

9.2.1. Quantitative analysis (QUANT)

The quantitative data generated based on content analysis was analyzed using descriptive statistics and chi-square test of independence. The descriptive statistics was used to see the frequencies of gender-related words, phrases, dialogues, and images (mainly photographs), and then followed by further tests of statistical significance using chi-square analysis to find out the existence of meaningful gender differences across the six categories.

9.2.2. Qualitative analysis (QUAL)

The qualitative data were of two types. The first one involves narrative texts which include sentences, dialogues, or paragraphs used in the textbooks. On the other hand, the second data type captured images—mainly pictures or photographs used as illustrations. The narrative textual data were analyzed using ethnographic, descriptive analysis method using the six categories developed earlier to identify the elements of gender (in)balance. The other data type consists of images, i.e. pictures or photographs, which were used to illustrate stories or actions presented in narrative form. This data type was analyzed based on the responses of two expert judges who were given the task of assessing the gendered aspects of images or photographs that send implicit or explicit messages of bias towards a particular gender group. Agreement between the two judges on the presence or absence of gender bias should be confirmed by their consistent descriptions of the implicit/explicit messages or stories represented by the images to qualify for inclusion in the data analysis and interpretation. This is because of the fact that the photos/images used in this study were not produced by the researchers. Instead, they were extracted from the textbooks. Under the circumstances, we preferred to draw on objective hermeneutics which, according to Flick (Citation2014, p. 452), focuses on the reconstruction of meaning structures. And, the two expert judges were the ones who reconstructed the meaning structures by closely observing and interpreting what the photos represent in relation to gender relations in Ethiopian society.

On the other hand, analyzing images is influenced by our “ways of seeing” (Berger Citation1972; in Flick, Citation2014, p. 340), because while reconstructing meaning, individuals not only relay on their repertoire, but their perceptions and judgments could be influenced by their idiosyncrasies (Banks, Citation2014). To minimize these impacts, the judges were given the following instructions: (a) to assess the images and photographs such that whether or not the pictures depicted in the textbooks represent gender equality, and (b) to indicate their impressions about the messages represented in writing.

The present study has attempted to ensure the trustworthiness of the qualitative data through employing various techniques. First, the credibility of the findings, which is an important component of trustworthiness, was verified using methodological and data triangulation since multiple qualitative techniques like data from illustrations and participants’ interview were used. The other technique was conformability which indicates getting closed to the objective reality or fact (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2003). In the due course of the study, live data was collected from women/girls through interview to disclose the facts on the depicted variables. Likewise, direct quotations and images were also included in the entire data to reveal the existing reality.

10. Results and discussions

As described earlier on, the content analysis of the two textbooks was made in two ways. First, we made frequency counts of indicators of gender representation indicators based on the six categories: language use, visibility in illustrations, occupational role, hegemony/topic domination and firstness. Similarly, the same categories were used to extract discursive statements, dialogues, sentences and paragraphs reflecting gender representation constitutes the qualitative dataset. In the paragraphs that follow, the gender balance in the “Communicative English Language Skills” course textbooks will be discussed simultaneously analyzing the quantitative and qualitative datasets.

10.1. Language use

Language use is one of the six categories under which we organized the datasets to examine gender balance in the Freshman English textbooks. This category analyzes words, phrases, dialogues with respect to the use of gender-related common nouns (e.g., man, boy, father, son, husband, brother, and uncle for males; girl, mother, daughter, wife, sister, and, aunt for female; pronouns (he, him, his for male and she, her, hers for female); and proper nouns. The frequencies of occurrences in the entire textbooks were counted as shown in Table .

Table 1. Gender representation in language use

Table shows the observed (actual) frequencies of language elements specified above. As it can be seen, the actual frequencies of most common nouns, proper nouns and pronouns signifying males outnumber those of females. Specifically, out of 381 occurrences, the proportional share of males accounts for about 61.1% (n = 233) of the total while female actors constitute the remaining 39% (n = 148). To determine whether the observed gender differences were statistically significant, a chi-square test was computed. As expected, the results reveal that the observed differences between masculine and feminine elements embedded in language use was statistically significant (Chi-Square = 18.96, p < .01; df = 1). This finding concurs with Gebremedihin (Citation2007), Yayeh (Citation2019), Melesse and Yayeh (Citation2020), and Dejene (Citation2017) who conducted similar studies on Ethiopian primary and secondary school textbooks. Related studies in other sub-Saharan African countries such as Ghana (Nunno et al., Citation2017), Kenya (Malova, Citation2012) and Uganda (Barton & Sakwa, Citation2012) also came up with consistent results. Furthermore, the present findings also concur with the results of a multi-nation study research focusing on social science textbooks (e.g., Blumberg, Citation2007).

Apart from the findings that are based on quantifiable elements of the “Language use” category, the qualitative analysis of textual data provided further evidence consistent with quantitative findings. In this regard, the dialogues presented below shade light how maintaining gender balance is overlooked in conversations used as examples or illustrations in English textbooks.

As it can be seen in Dialogue I, the interaction between Betru (male) with Tedla (male) could be modified to be between a male and a female instead of letting the conversation dominated by men.

Dialogue I

“What are you doing here, Tedla? I haven’t seen you since June.”

“I’ve just come back from my holiday in Nekemte.”

“Did you enjoy it?”

“I love Ireland. And the people in Nekemte were so friendly.”

(Source: Communicative English II, p. 58)

Dialogue II

Jack! Welcome back! How was the trip?

I am very exhausted. You know, I was annoyed with the man who sat next to me on the plane. He talked all the time.

Oh, really? What did he talk about?

Actually, it was unbelievable. He was talking about my friend, Grace, the whole time. He was in love with my friend whom he met last year but left him after only a month.

Oh! What a small world.

(Source: Communicative English II, p. 64)

On the other hand, the second dialogue (see Dialogue II), is totally controlled by males. Masculine nouns like “Jack” and Pronouns like “he”, “him” are interchangeably used throughout the conversation. Even the speakers’ names, which represent the gender category, become “A” and “B”. This can be considered as a wasted opportunity to ensure gender representation in the text.

10.2. Images as stereotypic messages

As described earlier in the methods section, images/photographs used in the textbooks were the focus of our scrutiny. In the quantitative analysis, we merely counted how frequently female and male subjects are depicted in all photographs or images used. In qualitative analysis, however, we focused on the question: To what extent these images/photographs send gender-balanced messages and which ones represent a stereotypic portrayal of females and males.

In the quantitative content analysis, which was based on counting the frequencies of occurrences of female and male subjects, the textbooks seem to have kept the balance. In this connection, 16 images/photographs are used in the textbooks (see Table ).

Table 2. Gender representation in pictures/images used in the material

Of these, eight images/photographs depict women and the remaining eight depict men. As such, at face value no gender difference was found as far as the frequency of portrayal of the two gender groups. This finding is inconsistent with Melesse and Yayeh (Citation2020) which reportedly found masculine dominance in pictures and images used in English language textbooks. Furthermore, in Uganda, Barton and Sakwa (Citation2012) reported that females are under-representation in illustrations; women make up only 20.7%, while men constitute 79.3% of the illustrations. Likewise, Pilley (Citation2013) reported that females are under-represented in the pictures used in South African grade 10 Business Study Books. These inconsistencies with the present finding may be attributed to the increased pressure on textbook writers and curriculum designers to keep the gender balance in Ethiopian higher education where several policy measures are undertaken to increase participation of women (see, in Semela et al., Citation2020; Semela & Miethe, Citation2021). This suggests that students do not have the chance to escape the gender stereotypes that appeal to their attention through the implicit and explicit messages sent via the same images which still have the potency to shape attitudes along traditional gender stereotypic lines, a situation which we will discuss in turn.

Accordingly, the picture below (see Picture 1) represents a rather subtle message since it depicts a man performing a typical traditionally feminine task of feminine alongside with several other women in Awramba Community of Northern Ethiopia, where men and women purportedly engage in all household activities without drawing stereotypic boundaries (Ebrie, Citation2015; Joumard, Citation2021).

Apart from depicting both men and women in the pictures that many tend to endorse as a balanced representation in the textbooks (Table ), some pictures, for example, the one in Figure , portray the male character as a leader having influential personality as he was pictured in the front-middle position. This interpretation is similar to Wafa’s (Citation2021) analysis of gender bias in Egyptian school textbooks.

Figure 1. A Man and several women depicted spinning to make cotton trades

In this vein, the two female professionals who worked as judges for the above picture confirmed the same. The following script is extracted from what one of the Judges had to say:

In the above picture, we can see that there are attempts to ensure gender equality as there is a man who is working with women. But, the number of males and females is not proportional since there is only one male in the group. Likewise, the picture portrays that the leading role in the task was provided to the man though there were many women in the picture. This shows that still there is an attempt to bring males in the leadership role regardless of the number of females in the category. [J1_P1]

Briefly, yet more revealing reflections from the judges of the second picture (Figure , above) are as follows:

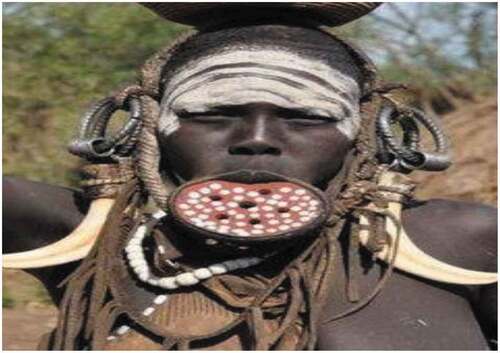

Figure 2. A Surma girl depicted going to the market (Southern Ethiopia). Source: Communicative English I, p. 42

The aims of the picture seem to depicts a woman beautify themselves in that specific culture in more stereotypic sense. [J1_P2]

Another judge states,

The woman pictured [above] seems to be performing her household chores … I see she carried something over her head … may be a container maid of clay [not very visible, though]. I don’t think this sends a message of gender equality. [J2_P2]

As it can evident, females were more likely to be supplementary characters, wear revealing clothes, and be portrayed as attractive and innocent. This suggests that using the frequency of men and women appearing in textbooks or learning materials as a measure of gender representation is inaccurate, if not misleading. Looking at the messages being conveyed, intentionally or otherwise, portrays the existing gender power relations in Ethiopian society that positions women as inferior to men. In this connection, our findings concur with Woyshner (Citation2006) who argue that the focus on the quantity of females in social studies textbooks rather than on the quality or significance of their actions which relegates women’s agency as supplemental denying their indispensable role in society including their cultural significance as a group (D. Sadker & Zittleman, Citation2007).

11. Priority in text as indicator of gender power relations

In addition to the analyses of “language use” and “representation in images/picture”, we examine gender balance in terms of who appears first in sentences, conversations or dialogue. This proxy indicator of gender balance is dubbed as “Firstness”. In other words, the textual data was assessed based on the questions: who initiates conversation? Who appears first when the two genders come together in sentences/dialogue? However, relaying on quantitative criteria to understand “firstness” is far from adequate as it says very little about the context or the situation that underlay the messages sent through sentences or conversations. To overcome these weaknesses of “firstness” as indicator, we used verbatim data to shade light to provide a context how appearing first in sentences and conversation could be deployed to send implicit messages of gender power relations; which is often conceived as an aspect of hidden curriculum.

11.1. Firstness as a mere frequency

The total frequency count based on “who appears first in sentences and conversations” in the studied textbooks was found to be 23 (see Table ). Of these, female actors appeared 9 times (39%), while male counterparts appeared 14 times (61%). Looking at the sheer frequency of occurrence, males have taken the upper hand. However, we computed a chi-square test to find out the extent to which the difference in the proportional share of female and male actors was statistically significant as shown in Table .

Table 3. Firstness in dialogues and sentences (N = 23)

Contrary to expectations, the observed difference did not achieve statistical significance (Chi-square = 1.08, p = 0.30, df = 1). This may be attributed to the small sample of firstness data we were able to collect form the two textbooks. Notwithstanding this, similar studies conducted in Ethiopia and other sub-Saharan African countries found masculine domination. In Ethiopia, Melesse and Yayeh (Citation2020) found that the ELT textbook was not gender-responsive for it has incorporated paired nouns/pronouns that favored the masculine gender. In Uganda, Barton and Sakwa (Citation2012) revealed that in 67% of the sentences and dialogues English Textbook. Likewise, Malova’s (Citation2012) analysis of secondary school English language textbook in Kenya shows a higher percentage of male actors appear first (62%). In South African Business textbooks, males took “firstness” 52 times in the two textbooks, while females take only 2 times (Pilley, Citation2013).

The qualitative data below provides a more concrete insight into how the existing gender stereotypes are implicitly maintained and reproduced in college classrooms through the hidden curriculum.

Script I

Allison and Nate, a brother and sister, live together in an apartment. They attend university in the same city, so they live together to share expenses. Their parents live in a different city, but they are visiting their children this weekend … ”

(Source: Communicative English II, p. 29)

Dialogue III

I want to speak English more fluently.

You should practice speaking every day.

(Source: Communicative English I, p. 11)

Regarding the sentences (see Script I), one may argue why wouldn’t the names of the actors were reversed (like “Nate and Allison”) or just replaced by other names if maintaining the alphabetical order should be maintained to reverse the gender of the actors (such that the female comes 1st and male 2nd) in the text had the authors been a little careful. Or change by replacing with a slightly modified version like: “Allison and Nate are siblings … ?” Similarly, Dialogue III (see above) shows the positions of the gender nouns in underlined cases. Aman (male) is depicted as initiator of the conversation, while Muna (a female) is portrayed as a respondent at the receiving end. The question here, is not why a male actor initiated the conversation. Instead, the textbook did not provide a second example where a female presented as initiator in order to maintain the widely known stereotype that women should follow men’s led (for detailed review on these stereotypes, see Semela & Miethe, Citation2021).

11.2. Gender division of labor

One of the avenues towards gender equality is ensuring equal educational opportunities for boys and girls to make their own vocational choices. This has been advanced not only by international agreements like UN Sustainable Development Goals, 2015 (Goal 5), but also by several national policies and legislations including in the education sector (Semela & Miethe, Citation2021). Nonetheless, such legal frameworks unable to fully address the impact of hidden curriculum which plays considerable role in perpetuating traditional gender stereotypes in the textbooks prescribed for college students. Textbooks play the role of keeping women in the background. Southworth et al. (Citation2020) illustrate this as follows: “… women’s historical contributions—when noted in a textbook—were largely contained within contributionist boxes rather than integrated into the main body text.” (p. 26). The findings of the present study attests to this investigation how women are depicted textbooks with respect to occupational roles (see Table ).

Table 4. Occupations represented by men and women

As it is indicated in Table , men and women are portrayed across 14 different occupations. In these occupational roles like company workers, cultural models, psychologists, women are portrayed more as contributors while, on the other hand, men are depicted as scientists, doctors, consultants, managers/president which are often considered as positions of power or main actors. Although there has been difference in terms of the frequency of appearance of men and women figures in a textbook, the quality of their representation in the textbook varies considerably. This is why Southworth et al. (Citation2020) criticize the heavy reliance on quantitative content analysis.

In language learning textbooks and materials, it is a commonplace to select examples involving a range of occupations in sentences, stories, dialogues, and the like. Male or female actors assume these occupations so that sensible communication could be made. In doing so, however, gender sensitiveness should come to ensure fair representation of both genders. Contrary to this, the present findings indicate that the majority of prestigious occupations were associated with masculine gender. In addition, closer examination of the occupations/professions assigned underscores the dominance of masculine since many of the professions where men are depicted to be one happen to be those offering higher decision authority like manager, university presidents as well as careers that entail considerable academic training like medical doctors, research scientists, and other prestigious professions suggesting men’s hegemony (see Table ).

Table 5. Professions that symbolize men and women

The textbooks essentially encouraging girls to go for subjects traditionally seen as “feminine,” such as languages, history, and home economics, and avoid mathematics and science, since they are seen as the masculine domain. This happens even when girls want to join science, they are expected to study biology and leave physics and chemistry typically reserved for boys (Leach, Citation2003). In the same way, at the university level, female students are usually associated with the arts, humanities, education, and health, while male students dominate in engineering, science, and computer science. Such choices and perceptions have a greater influence on their future career paths, which potentially limit the type and nature of occupation would opt to take up.

12. Masculine hegemony

The data presented summarizes the frequency counts of professions/occupations associated with female or male actors in the studied textbooks. The data essentially demonstrates what masculine hegemony looks like.

The comparison of gender representation based on the nature of the profession in line with feminist or masculine attributes embedded in the textbooks. Specifically, females are depicted as company workers, cultural models, artists, psychologists, celebrities and athletes, while males are portrayed as managers, development consultants, scientists, farmers, medical doctors and presidents. Though both of them were represented by various professions, the nature of representation seems not gender-sensitive/balanced. For example, males were represented by high-level officials like presidents and administrators. Also, they owed top intellectual occupations such as “scientist” and “Medical doctors.” However, females were not represented by profession having the same or equivalent status. So much so that such portrayal sends implicit message to the student that men are the ones who can make scientific discoveries/inventions or the ones who should aspire to become scientists. Likewise, frequent depiction of men as managers or even presidents (as observed in this study) implies that high leadership positions, including being a president, are reserved for men so long as women are excluded in such textbook stories.

The findings also coincide with Barton and Sakwa (Citation2012) who pointed that, in Ugandan English textbooks, women’s occupational roles are not only limited but also restricted mainly to those which are in the domestic sphere and less prestigious. Likewise, in South African grade 10 Business Studies Textbooks, in most situations, only males were depicted as top and middle-level managers, sole proprietors and economic leaders (Pilley, Citation2013). In Nigerian English language textbooks, apart from dominating dialogues and passages, males’ desirable character traits are the foreground, whereas undesirable female characters are portrayed more in the narratives (Mustapha, Citation2014). The finding can also be linked with the Bourdieu’s (Citation2001) gender socialization perspective which acknowledges the presence of masculine supremacy in gendered aspect of habitus that denotes the traditionally gendered division of labor like care-giving and service work for women, and managerial and technical work for men.

Finally, it is to be noted that being gender-responsive doesn’t mean meeting the exact ratio of the two genders in each category of measurement/unit of analysis. But, it means becoming more gender-sensitive and responsive in essence of language, content and images in terms of substance in developing textbooks and other learning resources employed for teaching and learning purposes at different levels. This has a huge contribution to gender equity as the contents in the textbooks/teaching materials have undeniable potential to impart an implicit lesson to students. Leach (Citation2003) states that learners’ extensive exposure to textbooks and other learning materials through years of schooling serves as a powerful medium for socializing young people into dominant patterns of gender relations and gendered behavior, which they will carry with them into adult life.

13. Conclusion

The findings suggest that despite the strong commitment in terms of policies and programs gender equality in education in general, and higher education in particular didn’t seem to achieve the intended objectives when it comes to offering equal playing ground for men and women. One of the key findings in this regard is the fact that the Freshman English (Communicative English Skills) prescribed for undergraduate students in all Ethiopian public universities constitute gender bias. On the other hand, as compared to the findings of previous studies based middle school English textbook (e.g., Melesse & Yayeh, Citation2020), the results of the present study suggest a relative decline in the magnitude of gender bias disfavoring females, especially with respect to the frequency of occurrences of female and male actors in pictures and illustrations in the textbooks. However, there is no such previous empirical evidence to broadly compare the qualitative findings based on text and images. Contrary to the apparent decline in gender bias in terms of frequency count, there is a compelling evidence of unbalanced representation in the qualitative content analysis which examined the bias in the messages of textual materials, i.e., sentences, paragraphs, and dialogue or conversations; and the messages that pictures/photographs used in the studied textbooks send to the students found to be strikingly consistent with gender-specific cultural stereotypes. This may be due to the methodology employed in the present study which combined quantitative and qualitative analyses of textual data. Added to that, the analysis of images/photographs in terms of the kind of occupational roles provided evidence that are more or less consistent with the findings of previous studies (e.g., Barton & Sakwa, Citation2012; Blumberg, Citation2007; Gebremedihin, Citation2007; Malova, Citation2012; Melesse & Yayeh, Citation2020; Pilley, Citation2013).

This study found out textbooks and learning materials at higher education institutions in Ethiopia convey the message that underscores male hegemony as a normal phenomenon without regard to students’ gender identities. Especially in the higher level where the learners are matured enough to carry out independent learning using the materials, such biased, if not discriminatory messages can easily be inculcated into their minds. In addition, the knowledge, information and skills embedded in various teaching materials at any academic level build certain values, norms and biases, which subscribe to the dominant views and beliefs of those who have constructed the curriculum and the learning materials. Thus, the Ministry of Education (MoE) and public universities need to undertake some intervention measures that aims at training with skills of developing gender responsive textbooks, learning materials and modules.

Overall, based on the findings one could safely conclude that (a) Gender bias in curriculum and textbooks is not only limited to the general school system, but the findings clearly indicate that gender bias is the integral part of hidden curriculum in university education. (b) The reliance on quantitative content analysis does not offer a complete understanding gender balance in curriculum and textbooks. As such, our findings reinforce a combination of quantitative and qualitative (QUNT-QUAL) content analysis (K. A. Neuendorf, Citation2011; Southworth et al., Citation2020) is a better approach to capture the nuances of gender representation in textbook and curriculum research to minimize gender bias.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge Bill and Melinda Gates’ Foundation for its financial support to this research through Grant ID INV-019167.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amare, G. (1967). Aims and purposes of Church education in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Education, 1(1), 1–18. https://ejol.aau.edu.et/index.php/EJE/article/view/1112/884

- Balsvik, R. R. (2005). Haile Sellassie’s Students: The Intellectual and Social Background to the Revolution, 1952–1974. Addis Ababa University Press.

- Banks, M. (2014). Analyzing images. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 394–408). Sage.

- Barton, A., & Sakwa, L. (2012). The representation of gender in English textbooks in Uganda. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 20(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2012.669394

- Berger, J.(1972). Ways of Seeing. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. Bohm-Duchen, London

- Blumberg, R. L. (2007). The invisible obstacle to educational equality: Gender bias in textbooks. Prospects, 38(3), 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-009-9086-1

- Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (2003). Qualitative research in education: An introduction to theory and methods. Allyn & Bacon.

- Bourdieu, P. (1997). The forms of capital. In A. H. Halsey, H. Lauder, P. Brown, & A. S. Wells (Eds.), Education: Culture, economy, society (pp. 46–58). Oxford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2001). Masculine Domination. Polity.

- Bourdieu, P. (2003). Cultural and social reproduction. In (C. Jenks, Ed.) Culture: Critical Concepts in Sociology (3rd) (pp.32–45). Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1977). Reproduction in education, society, and culture. Sage.

- Burk, D. (2014 March 5). 5 Evidences of Complementarian Gender Roles in Genesis 1-2, Bible & Theology, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/5-evidences-of-complementarian-gender-roles-in-genesis-1-2/

- Colclough, C. (2004, March 2007). Achieving gender equality in education: What does it take? In Prospects 129 (Vol. 34 (1) (pp.11–23). Open file: Gender Equality and Education for All.

- Dejene, W. (2017). A survey of gender representation in social studies textbooks of Ethiopian primary schools. British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioral Science, 21(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJESBS/2017/32754

- Detrich, R. (2015). Treatment integrity: A wicked problem and some solutions. Missouri Association for Behavior Analysis 2015 Conference. http://winginstitute.org/2015-MissouriABA-Presentation-Ronnie-Detrich

- Durkhheim, E. (1956). Education and Sociology. Trans. with an introduction by Sherwood D. Free Press, Fox; Foreword by Talcott Parsons

- Ebrie, S. (2015). Gender role perception among the Awra Amba community. American Journal of Applied Psychology, 3(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajap-3-1-4

- Edgerton, J. D., Peter, T., & Roberts, L. W. (2014). Gendered habitus and gender differences in academic achievement. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 60(1), 182–212. file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/admin,+AJER1311-Galley.pdf

- FDRE. (1995). The constitution of the federal democratic Republic Government of Ethiopia.

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research (5th) ed.). Sage.

- Fraenkel, J. R., & Wallen, N. E. (2006). How to design and evaluate research in education (6th) ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Gebremedihin, E. (2007). Gender bias analysis on grade five and six textbooks of Tigray Region. [Unpublished master’s thesis], Addis Ababa University.

- Georgescu, D., & Bernard, J. (2008). Thinking and Building Peace through Innovative Textbook Design. Report of the inter-regional experts’ meeting on developing guidelines for promoting peace and intercultural understanding through curricula, textbooks and learning materials (14-15 June 2007). UNESCO, UNESCO IBE and ISESCO.

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Harvard University Press.

- Giroux, A. H. (1983). Theories of reproduction and resistance in the new sociology of education: A critical analysis. Harvard Educational Review, 53(3), 257–293. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.53.3.a67x4u33g7682734

- INEE. (2010). Gender equality in and through education. INEE Pocket Guide to Gender. https://inee.org/sites/default/files/resources/INEE_Pocket_Guide_to_Gender_EN_%281%29.pdf

- Joumard, R. (2021). Awra Amba, a utopia between myth and reality. Research Report, University Gustave Eiffel. hal-03199059v2

- Leach, F. (2003). Practicing gender analysis in education. Oxfam.

- Malova, C. (2012). Portrayal of gender roles in Kenyan secondary school textbooks: An ethnographic view with special reference to English. University of Nairobi Library.

- Martin, C. L., & Dinella, L. (2001). Gender-related Development eds. N. J. Smelser & P. B. Balte International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, Pergamon

- Melesse, S. M., & Yayeh, M. (2020). Gender representation in educational materials: A focus on Ethiopian English textbooks. Springe Nature.

- Mirza, M. (2004). Gender Analysis of School Curriculum and Text Books. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000216890

- MOE. (2018). School Improvement Program Guidelines: Improving the quality of education and Students results for all children at primary and secondary schools. A.A.

- Mukherjee, R. (2015). Gender Bias. International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies, 1(VI), 76–84. https://oaji.net/articles/2015/1115-1438667826.pdf

- Mustapha, A. S. (2014). Sex roles in English language textbooks in Nigerian schools. Journal of ELT Applied Linguist, 2(2), 69–81.

- Neuendorf, K. A. (2011). Content analysis—A methodological primer for gender research. Sex Roles, 64(3–4), 276–289. https://academic.csuohio.edu/kneuendorf/vitae/Neuendorf11.pdf

- Nunno, F. K. N., Mensah, D. P., Boahen, E. A., & Nunno, I. E. N. (2017). Analysis of gender representation in basic level English textbooks in Gahana. Journal of Science and Technology, 37(2). https://doi.org/10.4314/just.v37i2.8

- Pilley, P. (2013). Gender representation in contemporary grade 10 business studies textbooks. University of KawaZullu-Natal.

- Sadker, D., & Zittleman, K. (2007). Gender bias: From colonial America to today’s classrooms. In J. A. Banks & C. A. McGee-Banks (Eds.), Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives (6th) ed., pp. 135–169). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sambell, K., & McDowell, L. (1998). The construction of the hidden curriculum: Messages and meanings in the assessment of student learning. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 23(4), 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293980230406

- Semela, T. (1997). The impact of maternal status attributes on gender role orientation and success striving of college girls. Ethiopian Journal of Education, 17(2), 26–41. file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/Tesfaye_MaternalStatus.pdf

- Semela, T. (2007). Identification of factors contributing to gender disparity in an Ethiopian university. Eastern African Social Science Research Review, 23(2),76–95.[ Link to abstract].http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/eas/v023/23.2semela.pdf

- Semela, T., Bekele, H., & Abraham, R. (2020). Navigating the river Nile: The chronicle of female academics in Ethiopian higher education. Gender and Education, 32(3), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2017.1400522

- Semela, T., & Miethe, I. (2021). East Germany in the horn of Africa: Reflections on the GDR’s educational intervention in Ethiopia, ca. 1977–1989. History of Education, 50(5), 663–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/0046760X.2021.1884753

- Southworth, E. M., Cleaver, R., & Herbst, H. (2020). Pushing past the margins” with Micro-Content Analysis: A Tool to Identify Gender-bias in Textbooks. Faculty Creative and Scholarly Works, 35. https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/faculty_staff_works/35

- Sroufe, A. L., Cooper, R. G., & DeHart, G. B. (1996). Child development: Its nature and course (3rd) ed.). MaGraw-Hill Inc.

- UNESCO. (2009). Promoting gender equality through textbooks: A methodological guide.

- Wafa, D. (2021). Reinforced stereotypes: A case study on school textbooks in Egypt. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 22(1), 374–385. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol22/iss1/22

- Wood, J. (2009). Gendered lives: Communication, gender, and culture (8th) ed.). Wadsworth Publishing.

- World Bank. (2020). Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above) - Ethiopia, Sub-Saharan Africa. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS?locations=ET-ZG, retrived on 21 Dec.2020

- Woyshner, C. (2006). Picturing women: Gender, images, and representation in social studies. Social Education, 70(6), 358–362. https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1001001346

- Yayeh, M. (2019). Analyzing curriculum materials from a gender perspective. Grade Eight English Textbook of Ethiopia in Focus.Bahir Dar Journal of Education, 19, 2. file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/322-1879-1-PB.pdf