Abstract

Few studies have highlighted the perceptions of teachers and school staff carrying out an intervention about future parenthood at special upper secondary schools. The aim of the study was to explore the experiences of teachers and school staff when implementing an intervention using the Toolkit “Children—what does that involve?” and the Real-Care-Baby (RCB) simulator. Four focus groups interviews were conducted 2019–2020 with 16 teachers and school staff involved in the intervention for students with intellectual disabilities. The intervention consisted of 13 lessons during school hours and caring sessions with the RCB simulator which resembles a three-month-old baby. Supportive school principals and colleagues were a prerequisite to conduct the intervention. Participants extended their teaching role with a sense of social responsibility and created a deeper relationship with the students. Through the intervention, the students gained important insights about parenting. The study shows that implementing an intervention requires a consensus-oriented organisation of education in collaboration with motivated colleagues and supportive parents. The teachers and school staff are well suited to provide adapted knowledge of future parenting and support the students to make informed choices about adult life and parenthood.

1. Introduction

Individuals with intellectual disability has the same right as anyone to be parents but gaining knowledge about future parenting is rarely done at school. The UN Convention on the Human Rights of Persons with Disabilities guarantees, e.g., the right of persons with disabilities to an inclusive education system at all levels, the right to make choices and decisions to become a parent (Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, 61/106). Research indicates that the number of individuals with intellectual disabilities that have given birth has increased (Coren et al., Citation2018). Research shows that parents with intellectual disabilities can improve their parenting skills, and important aspects in improved parenting skills are time spent in the parenting project, the intensity of services, tailored education, community engagement and client—worker relationships (Augsberger et al., Citation2020). While several interventions have been developed to assist people with intellectual disabilities in parenting and increase their parenting skills (Coren et al., Citation2018; Feldman & Tahir, Citation2016), few have focused on future parenting and providing a base for choices and decisions for young people with intellectual disabilities.

Attitudes towards sexuality have changed in recent years and a study found that professionals working with young people with intellectual disabilities in schools are open-minded to the sexuality of individuals with intellectual disabilities but feel unprepared and challenged to deal with reproduction and parenthood (Wickström et al., Citation2020). Another study suggests that teacher education and training programmes need to address societal norms and equip teachers with skills that manage complex information in the classroom, especially concerning sexual and reproductive health and rights, mandatory in Swedish schools for over 50 years (Nelson et al., Citation2020; WHO, Citation2009).

Early pregnancies are more common in adolescent girls with mild or moderate intellectual difficulties compared to other adolescent girls (18.4% vs. 3.3%) and Swedish register studies show that teenagers with intellectual disabilities are six times more likely to be parents than other teenagers (Höglund et al., Citation2012a, Citation2012b).

It is vital to find ways to support young people with knowledge before parenthood and it is reasonable to believe that the special school is such an arena. Implementing an intervention at special upper secondary schools is challenging, independent of the content of the intervention. A survey of special education teachers reports several barriers (e.g., knowledge gaps, faculty attitudes, lack of resources) concerning the intervention process (Werts et al., Citation2014). A study shows that schools face considerable challenges when implementing evidence-based interventions at schools with limited resources (e.g. funding, personnel, materials, time) and personnel training (Iovannone et al., Citation2019). In addition, the intervention was considered acceptable due to a coach offering support to the teachers. Developing and implementing evidence-based practices (EBPs) might improve outcomes for students with intellectual disabilities. A systematic review found that performance feedback played an important role and that such feedback increased the special teachers’ fidelity to EBPs (Schles & Robertson, Citation2019). Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) was developed two decades ago as a framework to explain the success or failure of implementation projects (Kitson et al., Citation1998). PARIHS proposed that successfully implementing evidence into practice was a function of three interactive core elements: evidence, context and facilitation (Bergström et al., Citation2020; Ullrich et al., Citation2014). The evidence for parental skills teaching suggests that behavioural based interventions are more effective than lesson booklets (Wilson et al., Citation2014).

An intervention model was created to provide students at special upper secondary school with intellectual disabilities with knowledge and experiences as a basis for informed decisions about future parenthood (Janeslätt et al., Citation2019). The intervention included educational sessions with adapted knowledge using the Parenting Toolkit, Children—what does that involve? (ASVZ) and caring sessions with the Real-Care-Baby (RCB) simulator. Previous studies focused on attitudes to parenthood and four of these studies found that the attitudes to parenting changed after intervention with the RCB simulator as the participants learned about the caring responsibilities, difficulties and challenges (de Anda, Citation2006; Jang & Lin, Citation2017; Roberts & McCowan, Citation2004; Wistoft et al., Citation2013).

The feasibility of the intervention model was tested in a study that showed that the model could be used in special schools for young people with intellectual disabilities (Janeslätt et al., 2018). The participants were individually interviewed after the intervention and the results revealed that the school-based intervention, combining theoretical and adapted knowledge and experience, promote student insights into future parenting (Randell et al., Citation2021).

Still, it is unknown how teachers and school staff experienced implementing a future parenting intervention in special upper secondary schools. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore teachers and school staff’s experiences when implementing an intervention using the Toolkit “Children—what does that involve?” and the RCB simulator.

2. Method

Four focus group interviews—two in September 2019 and two in October 2020 - were conducted with schoolteachers and school staff. The focus group interviews were performed by two of the present authors (BH and ER). These interviews lasted between 90 and 129 minutes (total = 6 hours and 47 minutes), and all interviews were audio-recorded with the participants’ permission. Two focus groups were conducted in quiet meeting rooms and distractions were minimal and two focus groups via Zoom due to COVID-19 restrictions. In total, 16 persons (15 females) participated, with most (n = 12) being schoolteachers; however, there were also other professionals, including two classroom assistants and two school counsellors, referred to as school staff.

The interviews were performed in a semi-structured format. A semi-structured interview guide was produced with each topic on a sheet of paper to encourage free and open communication. The interview guide included different areas, such as the intervention, the teachers’ role, the teachers’ challenges in implementing the intervention. Other areas involved supporting the students and informing their parents. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and thematic network analysis (Attride Stirling, Citation2001) was used to analyse the interview transcripts.

2.1. Intervention

The intervention was conducted at eight special upper secondary schools in different municipalities and in total 66 students gave their written consent to participate in the intervention. The students who participated were 16–20 years old and had mild to moderate intellectual disability. A person with an intellectual disability (ID) is defined as an individual with an intelligence quotient (IQ) below 70 and this medical definition of ID is divided into mild (IQ 50–69), moderate (IQ 35–49), severe (IQ 20–34), profound (IQ < 20), other and unspecific (WHO, ICD 10, Fifth edition, Citation2015). It is recommended by Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities that authors should not use an abbreviation to describe intellectual disabilities such as “ID” but instead, use person-first language such as children, teenagers, adults, or people with intellectual disabilities, avoiding acronyms or abbreviations.

The teachers and school staff (2–4 per school) were trained during 1.5 days about current research in the area, the Toolkit and the RCB simulator, including clinical experiences using the RCB simulator. The participating teachers joined a network together with researchers, and meetings held regularly included information, follow-ups, discussing problems, sharing experiences, peer-support and confirmations related to the intervention. Method support was given to all trained teachers and school staff via the recurring network meetings or when needed by phone or Email during the intervention from the study’s method supervisors.

The teachers informed the students’ parents about the new intervention in writing and orally at a parent meeting before initiating the intervention. By involving the parents, teachers could capture the parents’ thoughts as well as respond to their questions during the intervention. The integrity of the students was respected at all times and especially during communication with the parents.

2.2. Toolkit and the RCB-simulator

The parenting Toolkit was created in the Netherlands to fit the needs of young adults with intellectual difficulties and provide a basis for informed parenthood decisions (ASVZ). In this study, introductory cards with questions, “What I wish” and Toolkit “Children—What does that involve” were used. Toolkit was translated into Swedish and then adapted for special schools (Janeslätt et al., Citation2019). The Toolkit consists of five themes: Time, Money, Relationship, Housing and Skills. The intervention included 13 educational sessions provided once a week for 1.5–3 hours and each theme received at least two lessons and two lessons were used to introduce the RCB simulator. At the beginning of the sessions the introductory cards, “What I wish” were used to stimulate discussions about future working life and parenting.

The RCB simulator was created to stimulate discussion about the pros and cons of having a baby, thereby contributing to informed parenthood choices. The RCB simulator resembles a three-month-old child in size and weight and signals diverse needs with sounds recorded from real babies. The carer must interpret and respond to the signals given (hunger, new diaper, rocking, etc.). The level of care is registered in the simulator. In this study the teachers gave the students training in caring for the RCB simulator during lessons. The training was supported by a handbook adapted with pictures. Towards the end of the intervention, the students took the RCB simulator home for 3 week-days and nights. The RCB simulator was programmed for baby sitting during daytime when the student attended school. After the session was completed and the RCB simulator was returned to school, the teacher examined the data to evaluate how well the student had responded to the RCB simulator’s needs and had an individual conversation with the student discussing the student’s experiences of caring for the RCB simulator at home.

2.3. Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee in Uppsala, Sweden (Dnr: 2019–02421) and ethical considerations were taken into account. The participating teachers and school staff were provided with oral and written information about the study and signed an informed and written consent form. Participation in the study was voluntary and all participants had an opportunity to ask questions before and after the interview. Quotations in the results section are for a particular group (groups 1–4); however, quotes are not linked to a particular person or sex for ethical reasons. There was only one male among the 16 participants.

3. Data analysis

The data were analysed using thematic network analysis, an illustrative tool for interpreting and analysing qualitative material which include three levels: basic themes, organising themes and global themes (Attride Stirling, Citation2001). Initially, the transcribed interviews were read individually by all authors to gain an overall understanding of the content. Interviews were coded and the codes were clustered into a range of 10 basic themes which were then critically discussed by all authors. Next, the organising themes were created from the basic themes and refined. The network was built by arranging and describing the organising and basic themes and exploring the underlying patterns. Finally, the organising themes were clustered into one global theme, representing the pivotal point of the text. The thematic network was then summarised and the main findings presented. In the decisive step patterns were interpreted, presented and elucidated with verbatim quotes. The steps in the analysis were followed as described by Attride Stirling (Citation2001). All three researchers collaborated in data analysis, discussed the content of the interviews and contributed to the interpretation of the text, and were involved in negotiating the outcome. Reflexivity throughout the research process, and the analyst triangulation, with all authors contributing to the analytical process, aimed to establish credibility and confirmability of this study (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1986).

4. Results

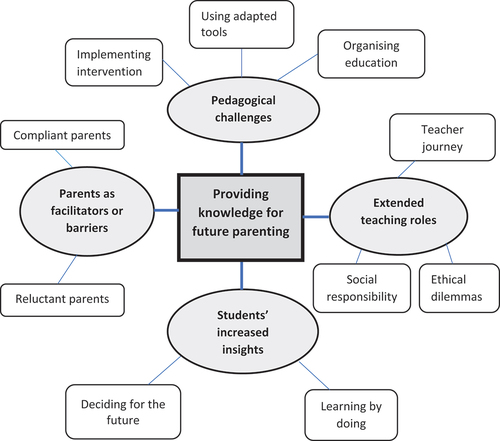

Four organising themes were created: Pedagogical challenges, Extended teaching roles, Parents as facilitators or barriers and Students’ increased insights (Figure ).

Figure 1. An image of a network with important aspects.

These four organising themes constituted one global theme: Providing knowledge for future parenting. This overarching theme expresses the participants’ willingness to conduct the intervention and offer the students adapted knowledge, even if it required considerable effort, as the ordinary teaching role had to be extended to develop and monitor the intervention process. The participants emphasised the importance of providing a basis with both skills and knowledge for students’ future choices and offering a social context at school to reflect, train and acquire knowledge about parenting, child development and care.

5. Pedagogical challenges

Implementing an education programme required several pedagogical challenges, such as being faithful to the intervention model, placing the student’s needs for knowledge at the forefront and a need to cooperate. The organising theme Pedagogical challenges consisted of three basic themes: Implementing intervention, Using adapted tools and Organising education.

5.1. Implementing the intervention

The schoolteachers’ experience of implementing school curriculum made it easier to work with the intervention in a goal-oriented fashion. The schoolteachers perceived that the intervention material required an extended initial work with colleagues regarding students’ already heavy schedules. The participants described that each weekly intervention session started initially with information from the teacher, followed by exercises capturing the session’s theme to serve as a starting point for discussion. The Toolkit was considered adequate and relevant, although some Toolkit questions were deemed abstract and challenging for students to understand.

Initially, some schools had a technical problem and other difficulties with the RCB simulator, which were remedied by the study’s method supervisors or the school’s IT support. Therefore, either method support or a detailed manual was deemed desirable, indicating the need for method support when implementing a new method.

5.2. Using adapted tools

The participants underscored the importance of conducting detailed and thorough preparations for the 13 lessons at the beginning of the contact with the students. Despite having the intervention material adapted to the target group, further explanations were needed to make it easier. Overall, the teachers found the intervention material to be appropriate and easy to follow.

The initial question cards, “What I wish”, made it easier for the students and teachers to focus on the topic and initiate discussions. “We [teachers] think the wish cards are a great entrance to the whole thing; it is a point in having them in the beginning” (G4). The questions sometimes needed to be adapted to the students’ skills and depended on the teachers’ experience of using them. Generally, when the students had difficulty understanding the intervention material, especially the non-native students, the teachers had to explain in their own words to make the material more coherent without changing the content. Because students with mild and moderate intellectual disabilities participated in the intervention, teachers identified a need to adapt the material to those students using pictures to support discussions. A teacher said: “We [teachers] adapted the material slightly, so it was less stressful for the students” (G2). Several teachers experienced this adaptation procedure as an educational challenge. The combination of theory and practice and the use of the RCB simulator were regarded as vital components of the process. A teacher stated, “Practice and theory build a bridge and the RCB is an unbeatable didactic tool in the invention study” (G1). Some groups used the last part of each weekly session to engage and interact with the RCB simulator and read the handbook.

5.3. Organising education

For a successful intervention, it was crucial to passing the principal’s gatekeeper position with an intervention that benefited the students’ needs now and in the future. Much effort, generosity and cooperation among the teachers and school staff were needed to organise the education and implement the intervention.

The school principals were significant for the approval and acknowledgement of the intervention. A teacher said: “Our school principal was really interested and understanding from the beginning and has given us free hand throughout the intervention” (G1). There were initial concerns from colleagues who did not appreciate the school hours spent on future parenting interventions. There was also some difficulty scheduling the intervention as the intervention teachers recognised the need to allocate time that could interfere with other school lessons. Other problems described included misunderstandings, feelings of exclusion among colleagues or irritation for lost educational hours, expressed in derogatory remarks (e.g., “playing with a doll”). As the intervention continued, the reluctant teachers became convinced that this intervention was necessary for the students’ future prerequisites. Some teachers pointed out, “When the students informed both classmates and teachers, the teachers” doubt disappeared and the intervention was perceived instead as very important and significant’ (G4).

One key point that emerged throughout the intervention was the strong desire to collaborate. The student assistants were essential participants in the intervention to respond, assist and answer student questions under lunchtime and school breaks in corridors. Some schools had a favourable experience from inviting the school nurse and social counsellor to participate in the intervention. For students and teachers, a successful method was to mention the scheduled lessons as “life skills” or “life after school”, facilitating the legitimacy of the intervention.

6. Extended teaching roles

Extended teaching roles required considering aspects beyond ordinary teaching, including the teacher’s role, social responsibilities and ethical dilemmas. The organising theme Extended teaching roles consisted of three basic themes: Teacher journey, Social responsibility and Ethical dilemmas.

6.1. Teacher journey

Throughout the intervention, the participants reported developing deeper ties with the students by expanding the knowledge area from ordinary education to include life and parenting skills, which involved many emotions and challenges. They also described personal growth and how they developed their professional skills after mastering the lessons in the intervention programme.

The participants described that by responding to the students’ questions and meeting their perspectives, they learned about students’ thinking and lives. In addition to close collaboration with the students, they collaborated with their colleagues to plan and share lessons and teaching assignments. One teacher said: “This intervention has strengthened us teachers because it is an approach that everyone is united around” (G1). They further described how they learned new things and new teaching methods and how to meet student needs. It was an ongoing process to learn how to use the material, and through experience, the participants increased their capacity. The participants described the exchanges of experience around implementing the model as vital and how it stimulated their learning process. The intervention goals differed from ordinary goals: “It is a completely new situation. It is not a knowledge goal we should chase. Now it is another knowledge acquisition—a journey I make together with my students and the knowledge goal is individual” (G1). They had to learn new understandings about effective teaching under these circumstances as the intervention was a novel approach for them. One participant said that in the beginning it was demanding to understand the breadth of the intervention: “I felt a little lost at first. I did not really know what I had agreed to” (G3). Several participants said they were not prepared to deal with so much distress and grief that some students expressed, often related to the students’ upbringing or making difficult future decisions. During the intervention, the participants learned to deal with the emotions underlining the importance of confidentiality which the students appreciated. The participating teachers said the intervention greatly affected them and contributed to new thoughts and reflections on their professional journey.

6.2. Social responsibility

They emphasised the warming up phase at the beginning of the intervention, which started with simple and easy discussions while having a coffee and cake to create a friendly and open atmosphere. The participants further emphasised the importance of involving the students right from the beginning and using question cards “What I wish” with items that consider the students’ view about a future life with or without parenting. One teacher pointed out, “I think it was a good way to begin because it starts a thinking process and reasoning” (G3). Because the students raised different life aspects, the participants believed it essential to not only focus on knowledge and skills but also on the person e.g., the family situation and wellbeing. Several participants shared their thoughts about the social responsibility they felt towards the students, and they mentioned the Swedish Education Act that states that schools must help students develop and practice the citizenship skills they need. One teacher stressed that students become carriers of the problem, explaining: “Make the difficulty visible, discuss it and lift the responsibility from the student’s shoulders” (G1). Contributing to the development and taking responsibility for the future were extended actions beyond school time: “For each lesson we give, for each insight, it may help a couple of parents in the future, that their baby gets a different start in life, and there is nothing so important” (G1). They specified the responsibility school has in preparing students and explained that the intervention was for their students’ future. The students opened up to the participants, making it a huge responsibility for the teachers to be available for the students. One participant said, “You get deep into the students who are part of the intervention; you get so close and see such a development” (G2). The participants experienced many feelings, including sadness and sorrow and they shared grief together with the students.

6.3. Ethical dilemmas

The participants said they had long and extensive discussions with their colleagues about ethical issues: “Among colleagues, we found ways to talk about the future together and ended up having exciting ethical discussions” (G4).

Some of their colleagues were convinced that they should discourage all students with intellectual disabilities from having children. Other teachers were more open and accepting in their approach. Different views raised several ethical dilemmas, such as the right to have a family. One teacher said, “I think that I should not influence my students but only convey knowledge—it is my mission, but at the same time I cannot help to think of some students that I hope will not have children” (G3). Another teacher had thought about the link between students and injustices, explaining, “I have not previously thought that this target group is so left out in every way” (G3).

7. Parents as facilitators or barriers to the intervention

The participants described that parents had varied possibilities for permitting their teenager to participate in the intervention. The organising theme Parents as facilitators or barriers to the intervention consisted of two basic themes: Compliant parents and Reluctant parents.

7.1. Compliant parents

The teachers informed the parents who participated in the parents’ meeting at school and were interested in the intervention. The participants expressed that several parents stated that they were relieved and grateful to the teachers for their systematic teaching that supported their teenager in such a demanding role as parenthood. Several teachers explained, “The majority of the parents without intellectual disabilities thought it was facilitating and valuable that we talked to their child about these difficult life issues” (G3, G4). Most parents encouraged their teenager to take the RCB simulator home. Some students needed clear and strong support from their parents to cope over several days with the RCB simulator at home. The participants said that some parents felt pleased to contribute to the care of the RCB simulator. They also explained to the teachers that this education was needed to avoid the consequences of early parenthood. One mother had explained to a teacher: If I had received this information in school, I probably would not have had a child so early in my life’ (G2). One participant mentioned that some parents appreciated having their teenager informed about economic matters, money and household finances as a single adult and imaginary parent.

7.2. Reluctant parents

The participants stated that some parents did not want their teenager to care for the RCB simulator at home, despite their teenager’s expressed wish to bring the RCB simulator home. According to one participant, a father said, “I don´t want the RCB simulator at home because I can’t manage it, so I hope she will refrain from doing it [bringing it home]” (G2). The participants assessed that several parents were hesitant or unwilling due to lack of their parenting capacity, thereby avoiding raising the issue of parenting with their teenager. Some parents argued that their teenager did not have to care for the RCB simulator because they could take care of a baby like any other young person. Other parents felt that their teenager was not thinking of parenting at this time in his or her life. The participants stated that parents who were reluctant to attend the parent meetings at school generally provided less support for their teenager. Teachers said, “Several parents who are not present at parent-school meetings broadly have less capacity to help their child with the intervention” (G3).

8. Students’ increased insights

The participants reported that the students gained increased knowledge through lessons and received practical experiences about a young infant’s needs and the care required through training with the RCB simulator, i.e. they learned by doing. The organising theme Students’ increased insights contained two basic themes: Deciding for the future and Learning by doing.

8.1. Deciding for the future

The participants said that the intervention affected the students’ opinions about their present and future choices and decisions. The participating teachers emphasised the students’ own agency in decision-making: “It is not because the students should not have children, but because they should gain knowledge, and we emphasize that almost every time. That they can make their own choices, that’s what’s important” (G4).

One participant explained that some students expressed feelings of sadness when they understood that they might not become parents because they could not cope with the RCB simulator. Another participant concluded, “I saw not only insights and knowledge but also sorrow and joy” (G1).

Some students ascertained that even if they wanted to be parents, they needed support to be a skilled and good parent. According to the participants, taking care of the RCB simulator was personally developing for the students. Although all students had trained in caring for the RCB simulator, many discontinued the intervention before ending the 3-day care period of the RCB simulator at home. One teacher stated: “Some of the students were sensitive for noise and realized that they could not cope with the loud crying sound of the RCB simulator, and could not cope the whole care period” (G1). Regardless of how long the students had the RCB, they all managed to gain invaluable experiences and insights. The participants said that the students understood how difficult and complicated it was with children and that it was even harder than anticipated. One participant stated concerning a student, “The insight came already at school that she was not ready” (G4).

The participants talked about confidentiality and trust among students who had the courage to share sensitive issues with the group. As one participant noted, “We had students who had a challenging childhood. They dare discuss that they don’t want their child to grow up like this” (G2).

8.2. Learning by doing

Participants reported that life skills were discussed among students who had not previously thought about how they would spend their time and money or what skills an imagined future would include. The participants said that the intervention gave the students the opportunity to think about practical living, household finances and budgets.

The training in caring for and understanding the development of the child provided concrete experiences. Practice caring for the RCB simulator gave skills, which improved significantly with training. One student took the RCB outside on school breaks: “A student really wanted to be a father. He was enthusiastic about this and he walked proudly through the school corridors with the RCB” (G2). The participants explained that the students were pleasantly surprised when they managed more than they had initially estimated. Some students were strengthened in their will to become parents, managing the RCB simulator better than expected. “We have a guy who we did not think would have the ability to take care of the RCB; now, he wants to participate again [in the intervention]. He grew enormously when taking care of the RCB” (G2).

The participants described the progress of the students when the RCB was in the classroom. From the beginning, the students were annoyed and angry because the RCB was loud and disturbed their concentration during lessons. Later, they could see another behaviour, one in which the students interacted and supported each other in the care of the RCB.

9. Discussion

This study explored teachers and school staff’s experiences during an intervention and our findings showed that implementing an intervention was a complicated process.

9.1. Structure and organisation

The participants shared many similarities in what they considered essential elements of the intervention. They emphasised the importance of organisational structure and factors as a prerequisite that included understanding and cooperating colleagues and a supportive school principal to arrange time and space on the school schedule for the intervention. Interaction between participants in the intervention and the structures in which the intervention is embedded influence the outcomes (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2015). Translation from research to practice and ensuring high-quality implementation involves both the intervention model and the support system. In addition, conducting the intervention is related to the students and teachers’ school culture and context (Domitrovich et al., Citation2008). Research has shown that the resources supporting school interventions e.g., funds, materials, space, equipment, a responsible leader and positive school culture facilitate the implementation process (Owens, Citation2001).

Support from a coach to teachers has proven to be valuable when implementing interventions (Iovannone et al., Citation2019). In this study, support from researchers and skilled professionals who provide method support through exercise and methods during the intervention were underlined by the participants. Of the three core elements in PARIHS (evidence, context, facilitation) (Bergström et al., Citation2020; Ullrich et al., Citation2014), this study showed the importance of easily accessible method support as an important facilitator. In line with Ullrich et al. (Citation2014) a context receptive to implementation, such as consensus-oriented organisation and supportive principal, had a positive contribution to the intervention.

9.2. Teaching role

The participants emphasised their teacher role in which social responsibility and ethical dilemmas were part of the reflections that extended beyond their usual teaching practices. The teachers had their journey to teach in a new, overlooked area. The professional and psychological characteristics of the implementer e.g., the teacher is an essential aspect influencing implementing (Domitrovich et al., Citation2008; Nelson et al., Citation2020). The participants gained competence and increased their knowledge concerning implementing the intervention, largely because of the adapted didactic tools that facilitated teaching and discussions. Knowledge about the intervention can influence an implementer’s perceptions, perceived effectiveness and understanding regarding higher treatment integrity (Dusenbury et al., Citation2003). The participants had in-depth discussions with the students, which helped increase the students’ ability to discuss skills related to family life. They also had spontaneous discussions with their colleagues regarding ethical questions, including the inalienable right to have children. Establishing a trustworthy relationship with the students can enhance the teacher’s ability to work effectively with personal and sensitive issues (Löfgren-Mårtenson, Citation2009). Consistent with Timmerman (Citation2009), our participants felt it was essential to create a safe environment for the students.

The teachers reported difficulty inducing the students not to be concerned about taking home the RCB stimulator. Sometimes the teachers had to deal with discouraged students. These emotions would often arise when they failed to take care of the RCB simulator at home or discerned a lack of parent support. The participating teachers invested emotional energy in both the intervention and relationships when supporting the students towards an adult existence that includes parenting skills. These efforts required a genuine interest, courage and commitment, which the participants strongly expressed.

9.3. Including parents

The successful intervention was strongly influenced by parent attitudes towards future parenting. The parents of the students were reasoning differently, and some were aware that their teenager could take care of a child, some may not. Studies show that collaboration between teachers and parents strengthens teacher-parent relationships and communication between school and home is vital for behaviour change, improved social values and good citizenry (Garbacz et al., Citation2017; Đurišić & Bunijevac, Citation2017). Nelson et al. (Citation2020) suggest that unsupportive home environments hinder children from developing knowledge and understanding in special areas, results that also emerged in our study.

Most of the supportive parents were grateful and emphasised the teachers’ efforts to provide knowledge in important life areas that the parents found challenging. The teachers noted that it was evident that some parents had cognitive difficulties that prevented them from supporting their teenager, especially when the RCB simulator would be taken home.

9.4. Learning for the future

The students increased their insights about future decisions and learned by doing based on their practical experiences. The teachers needed to adapt the material to some students, even though the intervention’s content was mostly well adapted to persons with intellectual disabilities. The teachers emphasised the need to provide knowledge using the Toolkit and creating practical learning opportunities through the RCB. Such knowledge could be used to provide a basis for future decisions. Similar results were found in a previous interview study of students (Randell et al., Citation2021).

The teachers perceived the model to be a useful tool to provide a base for the students to make informed choices about their future life, including parenthood and what steps to consider before having a child. For some students, postponing parenthood was their primary choice; others were confident to live a life without children.

Future research with a larger sample is needed to determine whether the intervention can influence young people’s attitudes and offer new insights to support them to make informed choices about adult life and parenthood. The intervention enhanced teachers and school staff’s ability to deal with sensitive topics about future parenting. The intervention also allowed the students to act independently and make their own choices, highlighting the capacity of them. This type of intervention could also be of value for families and society by enhancing inclusion, empowerment and equality for young people with intellectual disabilities.

9.5. Strengths and limitations

The present study was part of a randomised controlled intervention study, not reported here. One strength was that the present study included teachers and school staff who were motivated to participate and who had extensive training and experience working with students with intellectual disabilities. Another strength was that all focus group interviews were conducted by the same two authors following the same procedure. All interviews followed the same topic guide, and each question was shown on a sheet of paper to facilitate keeping focus during the group interviews. Within each question area discussions were stimulated by follow-up questions by the interviewers contributing to creation of rich data and authenticity. Further, a strength of our study was that the participants were recruited from a wide geographical area that included sparse and dense populations, covering small and large schools. The basic themes were presented including numerous rich quotes, contributing to authenticity (Graham, Citation2015). Trustworthiness (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1986) was enhanced by describing the process in detail to allow the reader to follow the analytical process.

A limitation could be that the interviewer was known to the participants from the network meetings held with the participants from schools and the researchers. A close relationship might allow some data to be collected that might not have been possible if the participants did not know the interviewer. Still, an unknown interviewer could enable the participants to feel free to criticise the intervention. Findings from qualitative studies are not meant to be generalised; the study was conducted in Sweden and the transferability of the findings might therefore be limited. However, we believe that the results from the study are transferable to other special upper secondary schools, at least in a Nordic context due to the similarities in the school systems.

10. Conclusion

The study showed that participating teachers at special upper secondary schools were important actors who provided adapted knowledge on probable future parenting for students with intellectual difficulties. The teachers expanded their teaching role through challenging teaching situations and discussions related to real-life situations. The ultimate goal of the intervention was to enhance the chances of young people with intellectual difficulties to become full citizens of society. The intervention required a consensus-oriented organisation in close collaboration with motivated colleagues and supportive parents. The teachers and school staff are well suited to provide knowledge for future parenting and support the students to make informed choices about adult life and parenthood.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eva Randell

Eva Randell, Associated professor of Social Work, Department of social work, Uppsala university, defended her thesis 2016 at Umeå University, Sweden. Her research is focusing on adolescent health, youth with intellectual disability, collaboration for children in need of special support, family support and interventions for parents with intellectual disability and cognitive difficulties.

Gunnel Janeslätt

Gunnel Janeslätt, PhD, MSc, OT(reg), defended her thesis 2009 at Karolinska Institutet, Sweden. Her research is focusing on time processing ability and daily time management in children, youth, adults and elderly with cognitive disabilities. In this process, she aims at developing and evaluating assessments and interventions to improve daily functioning in persons with limited daily time management. During the past ten years, she has added research in parents with cognitive limitations with special interest in evaluation methods for intervention.

Berit Höglund

Berit Höglund, Associated professor in Reproductive health, defended her thesis 2012 at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her research is focusing on pregnancy, childbirth and parenting among women with intellectual disability. Furthermore, contraception and ethical dilemmas at counselling among women with intellectual disability. Additionally, she added youth with intellectual disability, and special interest in evaluation methods for intervention.

References

- Attride Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100307

- Augsberger, A., Zeitlin, W., Rao, T., Weisberg, D., & Toraif, N. (2020). Examining a child welfare parenting intervention for parents with intellectual disabilities. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520958489

- Bergström, A., Ehrenberg, A., Eldh, A. C., Graham, I. D., Gustafsson, K., Harvey, G., Hunter, S., Kitson, A., Rycroft-Malone, J., & Wallin, L. (2020). The use of the PARIHS framework in implementation research and practice—a citation analysis of the literature. Implementation Science, 15(1), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-01003-0

- Coren, E., Ramsbotham, K., & Gschwandtner, M. (2018). Parent training interventions for parents with intellectual disability. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(7), 7. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007987.pub3

- de Anda, D. (2006). Baby think it over: Evaluation of an infant simulation intervention for adolescent pregnancy prevention. Health & Social Work, 31(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/31.1.26

- Domitrovich, C. E., Bradshaw, C. P., Poduska, J. M., Hoagwood, K., Buckley, J. A., Olin, S., Romanelli, L. H., Leaf, P. J., Greenberg, M. T., & Ialongo, N. S. (2008). Maximizing the implementation quality of evidence-based preventive interventions in schools: A conceptual framework. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 1(3), 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2008.9715730

- Đurišić, M., & Bunijevac, M. (2017). Parental involvement as a important factor for successful education. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 7(3), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.291

- Dusenbury, L., Brannigan, R., Falco, M., & Hansen, W. B. (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research, 18(2), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/18.2.237

- Feldman, M. A., & Tahir, M. (2016). Skills training for parents with intellectual disabilities. In Handbook of evidence-based practices in intellectual and developmental disabilities (pp. 615–631). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26583-4_23

- Garbacz, S. A., Herman, K. C., Thompson, A. M., & Reinke, W. M. (2017). Family engagement in education and intervention: Implementation and evaluation to maximize family, school, and student outcomes. Journal of School Psychology, 62, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.04.002

- Graham, C. R. (2015). Case studies: An authentic research method. In Conducting research in online and blended learning environments (pp. 97–113). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315814605-8

- Greenhalgh, T., Wong, G., Jagosh, J., Greenhalgh, J., Manzano, A., Westhorp, G., & Pawson, R. (2015). Protocol—the RAMESES II study: Developing guidance and reporting standards for realist evaluation: Figure 1. British Medical Journal Open, 5(8), e008567. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008567

- Höglund, B., Lindgren, P., & Larsson, M. (2012a). Newborns of mothers with intellectual disability have a higher risk of perinatal death and being small for gestational age. Acta Obstetrica Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(12), 1409–1414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01537.x

- Höglund, B., Lindgren, P., & Larsson, M. (2012b). Pregnancy and birth outcomes of women with intellectual disability in Sweden: A national register study. Acta Obstetrica Et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 91(12), 1381–1387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01509.x

- Iovannone, R., Iadarola, S., Hodges, S., Haynes, R., Stark, C., McFee, K., Grace, S., & Anderson, C. M. (2019). An extra set of hands: A qualitative analysis of stakeholder perspectives on implementation of a modular approach to school adoption of evidence-based interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 9(2), 25–40.

- Janeslätt, G., Larsson, M., Wickström, M., Springer, L., & Höglund, B. (2019). An intervention using the parenting toolkit “Children-what does it involve?” and the real-care-baby simulator among students with intellectual disability-A feasibility study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(2), 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12535

- Jang, L.-F., & Lin, Y.-M. (2017). The learning effects of using infant simulators in family life education: A study of undergraduate students in Taiwan. International Journal Of Research Studies in Educational Technology, 6(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrset.2017.1703

- Kitson, A., Harvey, G., & McCormack, B. (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. BMJ Quality & Safety, 7(3), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.7.3.149

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986(30), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1427

- Löfgren-Mårtenson, L. (2009). Hur gör man? Om sex- och samlevnadskunskap i särskolan [How Do You Do It? on Sex Education in Special Needs Schools.]. Argument.

- Nelson, B., Odberg Pettersson, K., & Emmelin, M. (2020). Experiences of teaching sexual and reproductive health to students with intellectual disabilities. Sex Education, 20(4), 398–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2019.1707652

- Owens, R. G. (2001). Organizational behavior in education: Instructional Leadership and School Reform (7th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

- Randell, E., Janeslätt, G., & Höglund, B. (2021). A school-based intervention can promote insight into future parenting in students with intellectual disabilities—A Swedish interviewstudy. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(2), 471–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12810

- Roberts, S. W., & McCowan, R. J. (2004). The effectiveness of infant simulators. Adolescence, 39(155), 475–487.

- Schles, R. A., & Robertson, R. E. (2019). The role of performance feedback and implementation of evidence-based practices for preservice special education teachers and student outcomes: A review of the literature. Teacher Education and Special Education, 42(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417736571

- Timmerman, G. (2009). Teaching skills and personal characteristics of sex education teachers. Teaching & Teacher Education, 25(3), 500–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.08.008

- Ullrich, P. M., Sahay, A., & Stetler, C. B. (2014). Use of implementation theory: A focus on PARIHS. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 11(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12016

- UN documents. 61/106. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Retrieved from http://www.un-documents.net/a61r106.htm#article-23

- Werts, M. G., Carpenter, E. S., & Fewell, C. (2014). Barriers and benefits to response to intervention: Perceptions of special education teachers. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 33(2), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/875687051403300202

- WHO (World Health Organization). (2009). Promoting sexual and reproductive health for persons with disabilities: WHO/UNFPA guidance note. WHO.

- Wickström, M., Larsson, M., & Höglund, B. (2020). How can sexual and reproductive health and rights be enhanced for young people with intellectual disability? –focus group interviews with staff in Sweden. Reproductive Health, 17(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00928-5

- Wilson, S., McKenzie, K., Quayle, E., & Murray, G. (2014). A systematic review of interventions to promote social support and parenting skills in parents with an intellectual disability. Child: Care, Health and Development, 40(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12023

- Wistoft, K., Stovgaard, M., & Sundhed, G. S. (2013). Virkningsevaluering Af Brugen Af Baby simulator I Familie- Og Seksualundervisning I Grønland, 1–73. https://pure.au.dk/portal/files/53329513/rapport_evaluering_dukkeprojekt_gr_nland.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2015). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, Fifth edition, 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/246208. Retrieved 20230514