Abstract

This study stands at the crossroads of folklorization, ethnicity, and curriculum. It seeks to criticize how the institutionalized production of knowledge about Amazigh folklore in Morocco has contributed to the creation and maintenance of a closed system of linguistic options for representing Amazigh ethnic groups through “folklorizing” their festivals, traditions, music, space, and marriage rituals. To investigate the micropolitics of folklorization in officially produced EFL textbooks in Morocco (1980-present), an integrated critical discourse analysis approach that oscillates between linguistic analysis and sociological analysis has been used. Results show that Amazighs have been mostly activated in relation to behavioral and relational processes and are therefore depicted as passive, deprived of sociological agency, with no effect(s) on others, or on the world. Excessive folklorization, results also indicate, commodifies Amazighs by reducing them to “exotic” commodities to be gazed upon. Amazigh females are caught in the realm of the “physical” and the “sensual” and are, hence, deprived of being represented as “thinkers” and “sayers” in mental and verbal processes. Non-Amazigh festivals and forms of folklore, on the other hand, are encoded primarily in material and transactive processes. Folklorization skews aspects of Amazigh identity to a flat set of criteria, such as “entertainment” and “exoticism”, which would give students a partial view of who Amazighs are mainly by iconizing them in a “celebratory” way which lacks analytical depth, bypassing, thus, significant concepts and topics related to the discrimination and subjugation of minority groups and their symbolic fights for power and social equality.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In this paper, I report on the socio-semantic resources available for the ‘folklorization’ of Amazigh social actors in selected EFL textbooks in Morocco. There are two important areas where this study makes an original contribution. First, the current study provides an important opportunity to advance our understanding of how the discourse of ‘folklorization’ has been imagined, transmitted, taught, and learned, or ignored in Morocco. Second, as far as scope is concerned, it seems that little to almost no attention, to the best of my knowledge, has been allotted to the representation of Amazigh ethnic groups in Moroccan curricula. The current study, it is hoped, will fill this gap by questioning the argumentative patterns that EFL textbook designers have resorted to in sustaining a unified ‘national identity’. This, I argue, will offer a profound and fresh look at identity politics in and through the Moroccan official discourse.

1. Introduction and background

The ethnic composition in Morocco is largely made up of Arabs, the dominant social group, and Amazighs, “the majoritarian minority” (Castellino & Cavanaugh, Citation2013, p. 5). “Scratch a Moroccan, find a Berber”, a telling article title by the American anthropologist David Hart (Citation1999), compels serious attention to the Arab-Amazigh axis in Morocco, and points out to the argument that although Arabs and Amazighs have co-existed side by side in Morocco for many decades, it is quite indisputable that the Amazigh cultural component remains “the backbone” of the Moroccan nation and even the basis of the whole North African ethnic architecture (Hart, Citation2000).

Situated at the crossroads of Africa and Europe, Morocco has often prided itself on being the meeting point for the Arabo-Islamic, Amazigh, African, Jewish and Andalusian civilizations. Morocco’s 2011 constitution has emphasized that the Moroccan cultural identity is shaped by the union of its Arab-Islamist, “Berber” and Saharan-Hassanic components, nurtured and enhanced by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences. However, of all these components, the Amazigh cultural and ethnic component stands out as being the most problematic. Historically, the ancient people of North Africa -from Egypt’s Western Desert to the Atlantic Ocean- have been referred to as “Berbers” (meaning “barbarian” in Greek but see Section 2 for a brief discussion of the appellation “Berber”). Speakers of Tamazight dialects have progressively embraced the ethnonyms Amazighs and Imazighen (the latter means free noble men) over the appellation “Berber”. According to Maddy-Weitzman (Citation1999), Amazighs’ distinguishing feature continues to be the various spoken dialects of a single language: Tamazight (Libyco-Berber, an Afro-Asiatic, previously Hamito- Semitic) (Maddy-Weitzman, Citation1999).

Although Amazighs account for a substantial majority of the population in Morocco, “they do not hold the reins of power or equitably share in it” (Bengio & Ben-Dor, Citation1999). And despite the new constitutional gains that put the Amazigh culture and language on equal footings with Arabs, Amazighs, “the majoritarian minority” (Castellino & Cavanaugh, Citation2013, p. 5) who suffered “censure and gross violence in colonial and postcolonial times” (Merolla, Citation2020, p. 27), have always stood out against political, cultural, and linguistic marginalization. The socio-political demands of the Amazigh movements were initially articulated in the “Charter of Agadir” on 5 August where they openly denounced “the systematic marginalization of the Amazigh language and culture” and militated for the “integration of the Amazigh language and cultures in various areas of cultural and educational programmes” along with the “right to have access to the mass media” (Maddy‐Weitzman, Citation2001, p. 31). In 2011, stirred by the Arab Spring demonstrations and upheavals in North African and Middle East, the political scene in Morocco opened up and the Amazigh political and civic movements soon found their voices (Said et al., Citation2023). The official recognition of Tamazight on constitutional grounds (alongside Arabic) has marked a turning point in Moroccan cultural policy to further strengthen its democratic credentials. Ennaji (Citation2014) contends that despite this, Amazighs today “demand not only linguistic and cultural rights, but also economic opportunities, political rights, and dignity” (p. 93).

Historically, Morocco faced the laborious and complicated task of “nation-building” that requires the fulfilment of a unified and continuing national narrative that would articulate a distinct Moroccan national identity and accommodate the tension between ethnic plurality and political homogeneity. Appeal to the notion of Moroccanness, an imagined-collective national identity built on the discourse of “sameness”, has been instrumental in activating the feelings of national unity and strengthening the inherent quest for cultural purity.

While the country appears to be on the threshold of a democratic breakthrough, Amazighs grievances continue to arise, including, inter alia, the reduction of their socio-cultural identity to folklore status (Said et al., Citation2023). Crawford and Hoffman (Citation2018) argue that the folklorization of Amazigh communities suggests that

change in Berber-speaking communities presents a threat to the perpetuation of Amazigh cultural heritage. Such nostalgic depictions of a segregated Amazigh identity stand in sharp contrast to the accommodating and flexible ways in which both rural and urban Moroccans conduct their social interactions and mutually influence one another (p. 125).

In education, moreover, the situation is even more subtle. Given that official school textbooks, in Venezky’s (Citation1992) terms, are situated in an intermediate position between “latent curriculum” and the “manifest curriculum”, they often used by nation states as ideological tools to convey the “selective traditions and ideologies of dominant social and cultural groups” (Yaqub, Citation2014, p. 222), and to create unquestionable and powerful “common sense” (Apple, Citation2000), especially with those nation-states (re)emerging from the remains of colonialism and struggling “to revive particular national myths and narratives long repressed, obscured, and quite selectively edited” (Yaqub, Citation2014, p. 222, emphasis in original). The power of school textbooks in shoring up a unified, sometimes biased, national identity, especially in multiethnic countries like Morocco, has received considerable attention (Abdou, Citation2017; Cheng, Citation2013; Chu, Citation2015; Gladney, Citation1994; Said, Citation2019, Citation2023; Taylor, Citation2017; White, Citation2009; Zhao, Citation2014). The vast bulk of studies, according to Said et al. (Citation2023), have largely rested on the binary dichotomy between “majority/minority” where the former is “included” and “normalized” whereas the latter is “excluded”, “subjectified”, “marked”, and, above all, “folklorized” (p. 2).

More strikingly, to add, results indicate that the representation of minority ethnic groups conjures up images of cultural folklorization where primitivity, poverty, tradition, and nostalgia form recurrent patterns. According to Gladney (Citation1994), “the widespread definition and representation of the ‘minority’ as exotic, colorful, and ‘primitive’ homogenizes the undefined majority as united, monoethnic, and modern” (p. 93). Consequently, recommendations tend to urge textbook designers to take high-priority actions to ensure that ethnic groups are granted equal and fair representation.

Despite this considerable number of studies dealing with the (under/mis) representation of ethnic groups in school textbooks, there is a noticeable dearth of research, to the best of my knowledge, pertaining to how Amazigh ethnic groups are portrayed/folklorized in school textbooks in Morocco. This indicates that there is a need to understand the various representations of Amazighs that exist in school textbooks.

Against this backdrop, the current research study seeks to problematize some facets of identity politics in Morocco by critically examining how key aspects of the Amazigh identity have been discursively folklorized in officially produced EFL textbooks in Morocco from the early 1980s up to now. More specifically, this study aims at developing the argument that the master narrative in EFL textbooks in Morocco has tended to folklorize Amazigh ethnic groups through instrumentalizing their festivals, traditions, music, and marriage rituals, among other ethnicity markers.

The theoretical background underlying the study’s central argument—the discursive reciprocity between folklorization, ethnicity, and curricula—largely draws on critical discourse analysis (CDA), a multi- and inter-disciplinary approach to the study of discourse and power (Chouliaraki & Fairclough, Citation1999) whose central mission has been to “play an advocatory role for socially discriminated groups” (Wodak & Meyer, Citation2016, p. 17). CDA aims at revealing the reciprocal relationship between linguistic structures and political structures, between discursive action and institutional structures. To examine the discourse of folklorization, the proposed analysis focuses on festivals as recontextualized social practices which, according to Van Leeuwen (Citation2008), include in addition to social actors, social actions, space, and legitimation (official knowledge).

To understand how Moroccan EFL textbooks normalizes folklorization, the analysis draws on Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) social actor approach, which is a concrete application of Hallidayan transitivity system. The study has made use of a nomadic set of concepts that find their critical unity in the “tourist gaze” (Urry, Citation1992), “sociology of the invisible” (Blumer, Citation1969; Scott, Citation2018), “Ethnic Integration Content” (Banks, Citation1989, Citation1999), and “official knowledge” construction in school textbooks (Apple, Citation2000). Data were gathered from 33 EFL textbooks which have been officially produced in Morocco over the last three decades (1980s-present). Following Said (Citation2019, Citation2023), the selected textbooks are assumed to be representative of three main historical periods that mark the evolution of EFL textbooks in Morocco: the Germinal Phase, the Critical Phase, and the Take-off Phase.

2. Amazighs: Finding an identity

The place and role of Amazighs in Moroccan politics has been a challenging issue that “the mere mention of the subject has long been taboo in many Arab states, because it clashed with the twin prevailing visions of the territorial state and pan-Arabism over the past half-century” (Bengio & Ben-Dor, Citation1999, p. vii). Specifically, the interaction between Amazigh social actors and Arabs has been characterized by Islamization and Arabization, which may overlap and reinforce one another without being necessarily mutually exclusive.

For example, Sadiqi (Citation2009) argues that Morocco is a land of Islam and equally a land of Amazighs. This intricate fusion of Islam and “Berberness” represents one of the central characteristics of present-day Morocco (Boukous, Citation2012; Ennaji, Citation2005). While it might be argued that Islam and Amazigh ethnicity are mutually exclusive, Amazighs were historically Islamized and, therefore, followed Sunni Islam as are their non-Berber Arab compatriots in North Africa (Maddy-Weitzman, Citation1999, p. 29).

By the same token, the process of Arabization has affected Amazighs, blurring the distinction between Arabs and other ethnic groups, including Amazighs (Al-Matrafi, Citation2018; Hart, Citation1999). The Arab influence has led to excessive Arabization, complicating the definition of Berber identity. Here, Maddy-Weitzman (Citation1999) correctly argues that “perhaps half of all North Africans have been so thoroughly Arabized over the centuries that they have lost all semblance of their Berber origins” (p. 29). According to this, Many Arab Moroccans are believed to be Arabized Berbers who adopted Arab culture and language for social mobility and/or power. This process of assimilation (Arabization and Islamization) is related to the “de-Berberization” of North Africa (McClanahan, Citation2006); hence, it could be reasonable to suggest that most Arab Moroccans as Arabized Berbers who might have willingly or unwillingly adopted an “Arab” culture and language for purposes of social mobility or access to power and resources.

Ennaji (Citation2014) summarizes the axis of “Islamization”, “Arabization” and “Berberness” by claiming that

Although many Berbers adopted Islam and Arabic, the process of Arabization” that began with the Arab conquest of North Africa in the seventh century and spiraled after independence from the French in the twentieth century did not eradicate the Berber culture. Berbers in Morocco have largely maintained their pre -Islamic traditions and cultural rituals (p. 94).

3. Amazighs: Finding a name

The term(s) used for referring to the Amazigh/Berber ethnic group(s) is disputed, causing both etymological and political confusion. “Berber” has a potentially negative connotation derived from its historical origins. Much of this terminological confusion (Amazigh(s), Berber or Imazighen) can be attributed to the lack of clarity as to the origin of the term “Berber”, which became established under the impetus of colonial ethnography of the nineteenth century. Natives who speak “Berber,” favor “Imazighen”, in the singular “Amazigh”, which means a “free (noble) man” over the appellation “Berber”. The use of “Berber” is regarded as deprecating by Amazigh natives (El Aissati, Citation2001).

According to Merolla (Citation2020, p. 27), although the terms “Amazigh” (sg) and “Imazighen” (pl) have replaced “Berber” in contemporary convention, the latter remains historically ingrained in research discourse. Similarly, Arab sources have used pejorative terms like “al-Barbar”, “lisân al-barbarî” (Berber language), and “al-barbariyya” to refer to Berbers. Likewise, the French term “berberes” carries colonial connotations (Crawford & Hoffman, Citation2018), while the English term “Berbers” is considered neutral and general and, above all, includes Berber varieties spoken beyond Morocco (Sadiqi, Citation1997).

In this context, Said (Citation2019, Citation2023) states that Moroccan scholars, such as Ennaji (Citation2014), Sadiqi (Citation1997), and Youssi (Citation1990), prefer the term “Berber” due to its neutral and general nature in the Anglo-Saxon world. They argue that “Tamazight” refers to a specific variety of Berber and may exclude other tribes like Tashelhit and Tarifit (Sadiqi, Citation1997, p. 12). In this study, extending El Aissati’s (Citation2001, p. 85), we will use the term “Amazigh(s)” instead of “Berber” to refer to the language in general and the natives. This choice tends to accommodate the preferences of the natives and supports the official “appropriation of the term ‘Amazigh’ in Morocco and in Algeria” (Merolla, Citation2020, p. 43).

El Aissati (Citation2001) succinctly summarizes the overall discussion in this section by pointing out that:

The common reasoning one hears, mostly during public meetings, is that the term “Berber” was initially used by the Greeks, then by the Romans, as a derogatory term to refer to people who were considered as “barbarians”. We should note that Romance-language dictionaries, particularly French ones-where so much has been written on Amazigh-simply state that “Berber” is the indigenous language of North- Africans, and reserve two different entries for “Berber” and “Barbare”. In Arabic, a language which is in intense contact with Amazigh, the same entry is used for “Berber” and “Barbarian”, with derivations like “barbara” “to babel”. This can perhaps explain in part the irritation that many Imazighen show when addressed as Berbers. Moreover, the term “Berber” is not used in any of the Amazigh varieties to refer to an Amazigh (p. 58).

4. Amazighs and the chronicles of education reforms in Morocco

The chronicles of education reforms in Morocco have undergone multiple births and baptisms regarding the role and place of Amazighs within the overall educational architecture in the country. After independence, the complex educational landscape inherited from the French colonizers led to various reforms in public education both in terms of theory and practice (Boubkir & Boukamhi, Citation2005). After independence, the National Charter for Education and Training (NCET), adopted in 1999, aimed for better-quality, decentralized, and culturally representative education. Above all, the NCET emphasized boosting Moroccan cultural diversity.

The Charter prioritizes Amazigh integration in education. For example, the 9th Lever stresses teaching Arabic, foreign languages, along with openness to Amazigh. IRCAM (The Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture) seeks the promotion of Amazigh language and culture. On 20 August , King Mohammed VI called for education restructuring in 2015, emphasizing fairness, equality, and quality. The royal speech was officially articulated in a national contract binding all stakeholders under the title of “Strategic Vision” (SV) which recognizes Tamazight as an official language for all Moroccans.The NCET and SV have upgraded the content of school textbooks. The National Directorate of Curricula designs the core curriculum based on ministry specifications. The National Curriculum and White Book address Morocco’s economic, social, and cultural needs while promoting Islamic, Moroccan, and Amazigh language and culture (Chaibi, Citation2009, p. 11).

5. Conceptual framework

5.1. Ethnic diversity and curricula

To proceed with discussing folklorization, a clear definition of “ethnicity” and “school textbooks” is required. Identity is based on the concept of “similarity”, where perceived identical things are the same. For instance, Edwards (Citation2009) defines identity as the “sameness” of an individual in all conditions, pointing out that a person is themselves and not someone else (p. 19).

Social scientists have not reached a consensus on the definition and effects of ethnicity, and that despite extensive research “nothing close to a consensus has emerged about not only what its effects are but also what it is” (Hale, Citation2004, p. 458). Ethnic identity is considered fluid and malleable, challenging stable and coherent definitions (Hale, Citation2004; Harris & Findley, Citation2014; Phillips, Citation2007; Romero, Citation2014). Compared to similar constructs such as race, ethnicity has gained more studious attention (Phillips, Citation2007, p. 16–17). In this study, ethnicity is defined as a socio-cognitive organizing principle that is socially marked (Brekhus, Citation1998) and politically imagined (Anderson, Citation1991).

Related to the above conceptualizations is the traditional link between language and identity which is inevitably an undertaking fraught with opportunities for failure (Joseph, Citation2004). The language-identity tie is both challenging and complex to discuss separately. Ethnic identity is often defined in relation to linguistic identity within a nation state with a central focus on language, power, and identity politics. Joseph (Citation2004) presents a comprehensive understanding of identity as a linguistic phenomenon, intertwined with nationality, ethnicity, and religion.

This study focuses on how language contributes to the partial creation of situated identity configurations in Moroccan curricula. Norton (Citation2010, p. 351) emphasizes the importance of analyzing language learning within social, historical, and cultural contexts, and how learners and teachers navigate diverse positions within those contexts. According to Hart (Citation2000), the Arab-Amazigh axis is essentially a linguistic one, where Amazighs represent both the most autochthonous as well as, very recently, the most change-resistant and conservative element of the population” (p. 8).

In the context of education, school textbooks reflect political choices, educational paradigms, cultural understandings, and language strategies. Apple (Citation1993) argues that the curriculum is not neutral but shaped by selective traditions and visions of legitimate knowledge. Therefore, the curriculum “is never simply a neutral assemblage of knowledge, somehow appearing in the texts and classrooms of a nation. It is always part of a selective tradition, someone’s selection, some group’s vision of legitimate knowledge” (p. 221). Textbooks offer insights into the social and political contexts of education, as they focus on specific elements of imagined culture (Bokhorst-Heng & Williams, Citation2016).

In the past 30 years, more information on minority representation has emerged. For example, Zhao (Citation2014) examines national identity construction in Chinese political education textbooks, identifying two legitimation strategies that are often employed in the discursive construction of national sameness. By the same token, Mugaddam and Aljak (Citation2013) analyze the discursive mechanisms used in constructing a unified Sudanese national identity in an EFL textbook (SPINE3). They find a biased representation favoring an Arabic and Islamic identity. Copts, an Egyptian Christian minority, are understudied in terms of representation. Abdou (Citation2017), in a similar context, proposes an integrated framework for analyzing minority representations in history textbooks, using a textual analysis of Egyptian history textbooks from 1890 to 2017. The study reveals a consistently smaller space allocated to Coptic history compared to other eras, limiting their contributions to the nation’s socio-historical narrative.

Limited research, however, exists on the discursive representation of Amazighs in education curricula in Morocco, with notable exceptions such as Said (Citation2019, Citation2023) and Said et al. (Citation2023). Said (Citation2023) critically analyzes the portrayal of Amazigh social actors in Moroccan EFL textbooks, combining linguistic and sociological perspectives. The study examines a wide range of officially produced EFL textbooks in Morocco, revealing the suppression, fixation, cataloging, and backgrounding of Amazighs . Furthermore, the study highlights the exclusionary stance promoted by the official discourse and recommends integrating more comprehensive ethnic knowledge in Moroccan EFL textbooks. In the same way, , Said et al. (Citation2023) conduct a case study on the emancipatory potential of complexification in challenging dominant discourses about Amazighs in a selected EFL textbook, Al Massar. The results demonstrate that the analyzed textbook promotes a more progressive position on Amazighs, challenging prevailing naturalized views. However, overall, there is a lack of research on the discursive representation of Amazighs in Moroccan education curricula.

5.2. Folklorization

Untiedt (Citation2006) defines folklore as the traditional knowledge of a culture which encompasses traditional and time-honored practices passed down through generations. This definition highlights the significance of understanding the historical context to fully value folklore. In the context of folklorizing ethnicity, Jiménez-Tovar and Lavička (Citation2019), for instance, argue that when folklore is commodified, it becomes a political weapon exploited by states for cultural supremacy. Folklorization is perceived as a hegemonic force that leads to alienation, fossilization, decontextualization, homogenization, commodification, and standardization (Denes, Citation2015, p. 3). This equates with “Ethnic tourism” (Hsieh, Citation2019) which contributes to the processes of folklorization and commodification, thus reducing ethnic groups to tourist commodities. Urry (Citation1992) argues that in the “tourist gaze”:

there has to be something distinctive to be gazed upon, that the signs collected by tourists have to be visually extraordinary. They are set off from everyday life and experience. The tourist gaze endows the tourist experience with a striking, almost sacred experience(p. 137).

Tourism shapes cultural images of ethnic groups, constructing an imagined “primitive” or “original” culture. Official textbooks can activate folklore elements, transforming or exploiting material culture for tourist gratification (Hsieh, Citation2019, p. 89).

Previous studies have invariably reported on the link coupling gender, ethnicity, commodification, and folklorization, and leading to the theorization of “the feminization of ethnicity” (Starrels et al., Citation1994). School textbooks often depict singing and dancing backgrounds with more female actors than males (Slimi, Citation2009; White, Citation2009). Such portrayals in textbooks commodify and objectify minority women, denying their individuality and subjectivity. Ethnic identities become increasingly commodified as they come under the laws of the market, marking the move from “identity to commodity” (Gladney, Citation1994; Leeman & Martínez, Citation2007; Slimi, Citation2009; Starrels et al., Citation1994; White, Citation2009; Zhao & Postiglione, Citation2010).

Folklorization and social (in)visibility are investigated based on theoretical insights from “the sociology of the invisible” (Blumer, Citation1969; Scott, Citation2018) where dominant social actors remain anonymous and unspecified, and their identity realized through indefinite pronouns. Weak social actors, on the other hand, are differentiated for discursive visibility, leading to stereotyping and exclusion. In CDA ideology is most powerful when it is invisible and naturalized. This explains why “visibility” breeds differentiation, stereotyping, exclusion, and discursive marginalization (Blumer, Citation1969; Janks, Citation1997; Scott, Citation2018; Slimi, Citation2009; Van Leeuwen, Citation2008; Zhao, Citation2014).

To cope with the situation, a substantial body of studies implies the need for an informed “Ethnic Content Integration Model” (Banks, Citation1989, Citation1999). Banks’ model aims to integrate ethnic content at deeper levels, moving beyond the superficial “celebratory” way which lacks analytical depth, and bypasses significant concepts and topics related to the discrimination and subjugation of minority groups and their symbolic fights for power and social equality. Banks (Citation1989, Citation1999) highlights the model’s ability to analyze the shallow inclusion of folklorization, overlooking discrimination, subjugation, and power struggles. Folklores can trivialize ethnic cultures, reinforce stereotypes, and perpetuate misconceptions (Banks, Citation1999, p. 18).

6. Methodology

6.1. Guiding question

This research seeks to address the following question:

How have key elements of Amazigh folklore contributed to a specific construction of ethnicity in Moroccan EFL textbooks (1980s-present)?

6.2. Guiding approach

Analysts within the CDA paradigm are divided along “how much linguistic theory and how much social theory to integrate in an ideal analysis” (Lauritsen, Citation2006, p. 43). This translates into whether analysts focus on the micro or the macro politics of discourse. The reconciliation of the two perspectives holds a great promise for the present study, allowing for a flexible oscillation between linguistic and social analysis. This, it is believed, is “what makes CDA a systematic method, rather than a haphazard analysis of discourse and power” (Rogers & Rogers, Citation2004, p. 7).

6.3. Textbooks analyzed: Sampling design

Although there appears to be no accepted canon of data sampling procedures in CDA, data collection remains an inescapable phase and almost never completely excluded (Wodak & Meyer, Citation2016). Given that we could not exhaustively examine all the Moroccan EFL textbooks, a decision was made to sample the existing corpus. Sampling was guided by the concerns of balance and representativeness. The corpus came from 33 officially produced EFL textbooks which have been developed, approved and distributed by the Moroccan Ministry of Education, which oversees all operations related to the production and circulation of teaching and learning materials in all Moroccan public and private schools and institutions, and have been required to be used in every school, public or private (This included ancillaries such as teachers’ books and workbooks. Appendix 1). More importantly, the selected textbooks were distributed over three periods that match the historical development of EFL textbooks in Morocco: The Germinal Phase, the Critical Phase and the Take-off Phase (Said, Citation2019). The periodization scheme proposed in Said (Citation2019) is briefly sketched below:

The Germinal Phase [from early 1980s to the late 1990s]. This represents the incipient phase that gave rise to the first “genuine” Moroccan EFL textbooks designed by Moroccan textbook committees.

The Critical Phase [the mid-1990s- mid-2000]. This was a critical-transitory period because it did not last for a long time and also because it was set at the crossroads of internationalization and localization.

The Take-off Phase [from mid-2000 up to now]. This phase witnesses new, transparent, and more diverse structures in the designing of EFL textbooks.

Additionally, the examined textbooks come from and cover all grade levels (from 9th grade to 2nd year baccalaureate level) (Appendix 1).

The methodological choices outlined above aim to balance non-probability and probability sampling (Kothari, Citation2004). I employed a mixed sampling design, combining probability and non-probability sampling, with a focus on stratified sampling. Stratified sampling identifies distinct subpopulations (strata) within the population, enhancing organization and homogeneity. This method ensures representation from each stratum, either in equal proportions or according to predefined criteria, resulting in a more reliable and detailed understanding of the population (Kothari, Citation2004; Krippendorff, Citation2004). The obtained picture is, consequently, more homogeneous than the total population. Stratified sampling, in brief, yields more reliable and detailed information.

The selection of specific EFL textbooks has been carried out according to five criteria which reflect the spirit of the stratified mixed sampling design. The first criterion is chronological, and it specifies different EFL textbooks from each phase. The second and the third criteria are concerned with level (one textbook for each level) and stream (Arts and Humanities vs. Science). The fourth and fifth criteria specify the selection of teachers’ guides and students’ workbooks. This kind of sampling has helped me avoid generalizations about all EFL textbooks, and instead seek common patterns and interpretations advanced by these textbooks.

6.4. Units of analysis

To specify the “ethnic units” of analysis, I categorized Amazighs as social actors referred to as “Amazighs”, “Imazighen”, or “Berber”. In some cases, the ethnic identity of Amazigh social actors in relation folklore episodes was unclear. Trained raters used socio-cultural traits to identify the ethnicity based on visuals and verbal references such as traditions, place, dress, language, among other ethnicity markers. Similar procedures were applied to identify Arab social actors. However, because of the Arabs’ predominant socio-political status in Morocco they were often unmarked, representing them simply as “Moroccans”. “Moroccanness” was naturalized and swapped in the textbooks with a “standard” image indicating a simplified “Moroccanness”. This step enhanced inter-rater reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: α = 0.90 to α = 0.94). Finally, folklore episodes were analyzed using critical sociosemantic categories introduced below.

6.5. Procedures of analysis

Silverman (Citation1993) notes that one of the dilemmas facing researchers- CDA analysts as well—is “how our research can be both intellectually challenging and rigorous and critical” (p. 144). One way of fulfilling Silverman’s requirement is to combine quantitative and qualitative methods. However, this combination can be effective only if we avoid what Wodak and Meyer (Citation2016) ironically call “cherry picking”, or merely choosing the examples that best fit the researchers’ assumptions (p. 11). Therefore, the analysis I proposed in this study observed three steps.

First, in analyzing the folklore narratives of Amazighs vis-à-vis the dominant narratives, I adopted a holistic and integrated framework (Abdou, Citation2017) that critically examined the micropolitics of folklorization by focusing on the defining properties of folklores, mainly, festivals, music, cultural artefacts, systems of knowledge, and space. Technically, a decision was made to analyze the available representational choices and argumentation strategies that Moroccan EFL textbook designers have drawn to folklorize Amazighs.

Second, once the defining properties of folklorization were identified, the analysis went on to examine the discursive aspects of meaning in relation to social actors, social actions (process), and circumstances (when/where). Key elements from transitivity processes (Halliday, Citation1985), Agency Analysis (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012) and socio-semantic inventory of Social Actors Approach (Van Leeuwen, Citation2008) were also applied. The examined element included:

Social actors/participants: This involves both “the ‘doer’ of the process as well as the ‘dons-tos’ who are at the receiving end of the action; participants may be people, things or abstract concepts” (Machine & Mayer, 2012). This step was combined with Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) socio-semantic inventory which consists of “inclusion”, “role allocation”, “genericization and specification”.

Social actions/processes which are analyzed in terms of verbs and verbal groups system. According to Halliday (Citation1985), this system is divided up into six processes: material, mental, relational, behavioral, verbal, and existential. Material processes construe “doings” and ‘happenings, involving two participants: an “Actor”, and a “Goal”. Mental processes construe “sensing”, or “consciousness”. Relational processes encode processes of “being”, “having” or “being at”. Behavioral processes construe physiological behaviors such as smiling or breathing. Behavioral processes are, however, often caught between material and mental processes because the physical and mental aspects of processes are inseparable. In this context, Halliday (Citation1985) notes that “the behaviour is typically a conscious being, like the Senser, but the process functions more like one of ‘doing’” (p. 128). Verbal processes are processes of “saying”; they represent “symbolizations involving a symbol source, the Sayer” (Matthiessen et al., Citation2010, p. 238). Existential processes constitute the last type in the system of transitivity processes. These processes entail that something exists, happens, or occurs.

The last step in the analysis consisted of two complementary moves. First, tables of frequencies and percentages summarizing folklore narratives of Amazigh (and Arabs) were generated. After computing frequencies and proportions, a series of Chi-square tests of significance was employed, when needed, to examine the significant differences between either Amazigh and Arab social groups or in terms of each analytical category.

Second, to assess the findings from multiple vantage perspectives, the results of the tables of frequencies and percentages were brought under the critical radar of the theoretical apparatus developed in the theoretical part, such as “the sociology of the invisible”, “official knowledge”, “ethnic content integration”, “commodification”, and “ethnic tourism”.

7. Findings and discussion

School textbooks bear visible, and more than often imperceptible, traces of what Williams (Citation2014) calls the “social effect of schooling” which describes “how things were, what happened, and how they came to be the way they are now” (p. 1). This means that in the process of the selective representation, ethnic groups and their cultures are seriously underrepresented, marginalized (Chu, Citation2015), and/or left unimagined in the official state narrative (Anderson, Citation1991). Critiquing the ideology of the Moroccan EFL textbook narratives by investigating how Amazighs, through the discourse of folklorisation, have been imagined, taught and learned, or ignored, are major issues that this study aims at researching. While the overall aim is to evaluate the state’s official response to cultural and ethnic diversity to promote equity and national unity, the specific aim is to deconstruct and make visible the mechanisms through which Moroccan ELF textbooks might become the ideological state apparatuses.

To examine the discourse of folklorisation, the proposed analysis focuses on festivals as recontextualised social practices which include in addition to social actors, actions, time, space, and legitimation. Folklorization rests (among other things) on festivals, music, cultural artefacts, systems of knowledge and space. I analyzed these facets of folklorization separately, examining the chains of contextualization for each component in terms of social actors (participants), social actions (processes), and legitimation (knowledge).

7.1. Festivals

A total of 13 instances of festivals were identified. Table shows the occurrence of these festivals according to whether they have been identified as exclusively Amazigh or left unmarked and therefore belong to the all-inclusive component: Moroccan(s). Amazigh festivals have been included significantly more than the non-Amazigh ones. The results of the Chi-square test (p > 0.05) indicate that the observed difference is not statistically significant.

Table 1. The occurrences of festivals in Moroccan EFL textbooks

Bringing the discursive inclusion of the unmarked Moroccan festivals under the critical radar of Scott (Citation2018)’s notion of sociological markedness, it seems that festivals identified as “Moroccan” were represented as normative, mundane, and therefore were left invisible. However, festivals which were identified as Amazigh were named, marked, and presented as worthy of analysis. In other words, the discourse of folklorization depicts the Amazigh ethnic component as distinctive, interesting, and therefore worthy to be made visible. This selective construction of knowledge of Amazigh ethnic groups highlights the visible ethnic features “where the ethnic groups included most often are not always the most populous ones, but mostly the ones with observable ethnic and cultural characteristics” (Chu, Citation2015, p. 477).

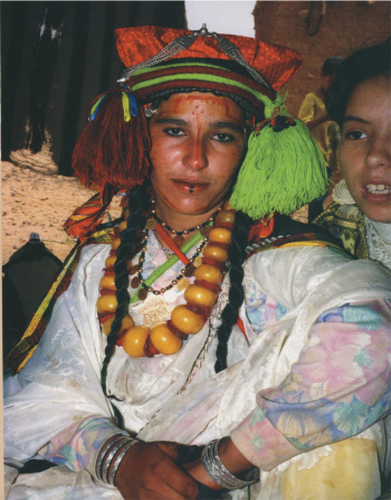

Among the various festivals that Amazighs celebrate in Morocco, Imilchil Marriage Festival has received considerable attention by Moroccan EFL textbook designers. According to Said et al. (Citation2023), this festival continues to assert itself as the only occasion through which Amazighs have been made visible. Over-presenting this festival has iconized Amazighs inside and outside Morocco, rendering them folklorized “others” in Morocco and “exotic” commodities to be gazed upon by tourists outside Morocco—a gaze akin to and reminiscent of a former colonial or orientalist gaze. In terms of multimodality, the Imilchil Marriage Festival has been allocated considerable linguistic and visual space throughout the three phases, marking a discursive association between Amazighs and marriage festivals.

A more focused way of studying the grammar of the folklorizing Amazighs would entail the reduction of folklorization to its essential discursive elements; namely, social actors, actions, place, and knowledge.

7.1.1. Social actors and actions

Given the centrality of gender as an analytical category in the discursive representation of Amazighs, three questions are in order: who has been included in the state’s narrative discourse of “folklorization”? How have Moroccan EFL textbooks depicted the included social actors? And to what end? Table indicates that female social actors were included with more frequency compared to males. The difference between the two included social actors fell just short of statistical significance.

Table 2. Results of the linguistic inclusion of male and female social actors

In CDA, however, the analysis needs to further examine the role(s) that Amazigh women were given to play in this “festival” discourse. These roles, to draw on Van Leeuwen (Citation2008) for example, can be reallocated whereby social relations between participants are rearranged, allowing Amazigh females to be either activated (examples 1, 2), or passivated (example 3). Activation means social actors are depicted as “active, dynamic forces”, whereas passivation occurs when participants are the recipient of, or “at the receiving end” of an activity (Van Leeuwen, Citation2008).

Example 1: Young women wear their best clothes and beautiful silver jewellery (FSE, p. 216).

Example 2: Some (women) are veiled but most do without this and show off their beauty, enhances with rouge for their cheeks and kohl for their eyes. They wear a rounded spangled headdress if they have never been married or a pointed one if they are divorced or widowed (Gateway1, p. 72).

Example 3: Henna, a reddish-brown organic dye; is applied to the bride’s hands and feet before the wedding to ward off evil eye. (Ticket 1, p. 110)

Evidence in Table shows that Amazigh females have been activated more significantly than being passivated, which leads to the assumption that Amazigh women have been assigned active roles. Chi-square reveals that the difference is significant.

Table 3. Results of role allocation for female social actors

However, being activated cannot qualify as an indicator of power, equal or fair representation. To further investigate the functional properties of the activities wherein Amazigh women have been activated, Halliday and Matthiessen (Citation2004)’s transitivity model has been used. Table shows that Amazigh women have been mostly activated in relation to behavioral and relational processes more significantly than other processes.

Table 4. Results of processes featuring Amazigh women

Two important properties render the analysis of behavioral processes relevant here. First, behavioral processes are non-transactive, requiring only one participant. When the actions and reactions of Amazigh females are behavioralized, they are represented as ordinary actions, without substance, intention or impact, and are ultimately depicted in socially low status. Van Leeuwen (Citation2008) explains that “the ability to ‘transact’ requires a certain power, and the greater that power, the greater the range of ‘goals’ that may be affected by an actor’s actions” (p. 62).

Second, excessive representation of social actors in terms of behavioral processes casts females in the realm of the “physical” and the “sensual” and, hence, deprives them of being represented as “thinkers” and “sayers” in mental and verbal processes. The emphasis falls on emotional outcomes, cravings, desires, and wishes. Again, as Van Leeuwen (Citation2008) observes “the greater the power of social actors, the more likely it is that cognitive, rather than affective, reactions will be attributed to them” (p. 58). The examined textbooks often display aquatic sceneries, in whose proximity Amazigh women stand reminiscent of the heartrending Issli and Tsslit folktale. This picturesque depiction, however, never goes anywhere near exposing nudity or what would certainly be considered indecency in a conservative society such as Morocco.

7.1.2. Knowledge construction

As was indicated in Table , festivals in Morocco are either exclusively Amazigh or inclusively Moroccan (Arab). However, there are several interesting contrasts which can be discussed using the sociology of the invisible and the categories of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL). The sociological lenses predict that the exclusively Amazigh festivals have been discursively marked and therefore straightforwardly identified; the second type of festivals, however, has been left unidentified, and thus discursively invisible. These two types of festivals seem to articulate two perspectives of knowledge construction, with the first being embedded in the mythical, and ultimately lending itself to irrationality, and the second deeply rooted in the real and hence embodying rationality and wisdom (Said et al., Citation2023).

A more concrete way of highlighting the discursive discrepancies between the two types of festivals can be seen through utilizing tools from Halliday’s SFL (transitivity) and Van Leeuwen’s tools of CDA. Example (4) and (5) describe two non-Amazigh festivals: Asilah festival and the Wax Lantern festival respectively.

Example 4: The festival of Assilah is a cultural event [where] professional Moroccan artists, members of The Moroccan Plastic Arts Association, take part in a campaign to improve the urban environment … it contributes to a greater consciousness of art, vision and imagination. Asilah’s history goes back 3,600 years. Asilah was once an important commercial centre and a crossroads between East and West (Further Steps to English, p. 188).

Example 5: The Wax Lantern Festival or Dor Esh Shemaa. This colourful festival took place yesterday on the eve of the Mawlid, a feast celebrating the birth of the Prophet Muhammad. Some people say that the Wax Lantern Festival is of Turkish origin and was introduced into Morocco in the sixteenth century. Others claim this festival dates back to the times of the corsairs of Sale (Further Steps to English, p. 213).

First, in terms of the transitivity system, non-Amazigh (Moroccan) festivals are encoded primarily in material processes which are often transactive and, therefore, require a “doer” or “agent” whose influence on the surrounding is tangible. Assilah festival, for instance, requires active social actors who can “paint”, “hold”, “decorate” and “move”. Likewise, The Wax Lantern festival is encoded in terms of material and mental processes. Amazigh festivals, on the other hand, are encoded in behavioral processes (dance, smile, sing etc.) which do not require a goal and, therefore, lack social agency. These processes also point out that Amazigh social actors lack “voice” to talk about themselves; they are “represented” ”described”, “photographed”, and ”talked about”. Being silenced, the discourse sets limits to what Amazighs can think, say, or do, with speechlessness as “a necessary condition of being the gazed-upon” (Schein, 2000, p. 234, as cited in Zhao & Postiglione, Citation2010, p. 329).

Second, the discursive construction of participants contrasts sharply across the two types of festivals. While Amazigh festivals passively foreground females, both linguistically and visually, over males, non-Amazigh festivals blur this distinction, including both female and male social actors and representing them on equal footing. The third noteworthy distinction is related to the discursive construction of space, being a political index of power. While Amazigh festivals are exclusively tribal and rural, and thus betraying an allusion to “primitiveness”, non-Amazigh festivals are predominantly encoded in urban spaces such as cities, and hence symbolizing modernity.

Finally, the two types of festivals draw on three legitimizing topos: Rationalization, Sanctification and Mythologization. The example of Assilah festival “rationalizes” art through appeal to high canonized culture. It is a moment when art is celebrated in an “intellectual” manner and where the “elites” gather to “discuss” and “reflect” on cultural issues. The Wax Lantern festival, on the other hand, is legitimized through appeal to the authority of religion, constructing itself as a companion to the “Mawlid”, a feast celebrating the birth of the Prophet Muhammad. Accordingly, The Wax Lantern echoes the holy and therefore “sanctifies” its presence as an institutionalized knowledge. Amazigh festivals are legitimized through appeal to the myth of Tisli and Isli, constructing its legitimacy underneath the rational and outside the holy.

7.2. Music

The uneven construction of the official knowledge with respect to festivals continues to assert its presence through other forms of folklorization such as music and handicraft, casting more doubt on “the art for art’s sake” belief. I compared the representation Amazigh music to the Andalusian one (examples 6 and 7), juxtaposing them along various axes.

Example (6): Most people call it Andalusian Music. AL ALA means the instrument. The word is used to differentiate it from the old religious vocal chant where the use of an instrument was banned. This type of music was born of the fusion of Arab and Andalusian Culture, a fusion which took over eight centuries … Andalusian Music is savant and subtle. It used to be within the reach of only a small intellectual elite … (Quick Way, 2, p. 31).

Example (7): MEET THE MASTER MIND-BEHIND ANDALUSIAN MUSIC. When he died in 857, Ziryab- the nightingale- was already recognised as the most remarkable musician who had ever lived. We owe Andalusian music to Ziryab: we also owe to him some of the finest songs ever sung- Al Muwashahat. (EIL3, p. 137).

First, the mode of representing Amazigh music is predominantly visual compared to the multimodal representation of Andalusian music. The choice of one mode over the other is critically significant, with the pictorial constructing a direct appeal to the eye, to the material, to the concrete and, above all, to the physical; and with the linguistic, signifying the cognitive, the abstract and the “intellectual”. The representation of Andalusian music seems to assume both roles. Second, the (Arabo) Andalusian music has been reserved for the elite. In (6), we read the Andalusian Music is both savant and subtle, weaving an implicit allusion to other types of music thought to be “subtle” and “savant”, say, the opera which combines entertainment and “high knowledge” in the production of art. The examples also maintain that Andalusian music has been reserved for the intellectuals, and thus, lending further “halo” to it. Example (7) underlines the master mind behind the Andalusian music as a nightingale and the most remarkable musician who had ever lived. On the other hand, Amazigh music, say Ahwach, is represented as an outdoor type of music, set against natural backgrounds (often mountains), with female and male singers and dancers. The representation often foregrounds female dancers and singers both in quality and in number. Linguistically, the discourse seems to be taciturn when it comes to articulating the socio-intellectual history of Amazigh’s songs, presenting them as objects, or “moments” for entertainment.

7.3. Handicrafts: From pride to profit

The analyzed textbooks from the three phases asserted a strong link between Amazigh identity and traditional carpet weaving. The centrality of these symbolic processes in the representation of Amazighs, especially women, conjures up orientalistic, almost De La Croix style depictions, where color and exoticism reigns supreme as to distract from essence. In this respect, Becker (Citation2006), succinctly summarized the scene, giving women the role of an artist:

Berber women are artists. They weave brightly coloured carpets… They embroider brightly coloured motifs on their indigo head coverings and on special occasions wear elaborate silver and amber jewellery (Figure ). Women both create and wear the artistic symbols of Berber identity, making the decorated female body itself a symbol of that identity (p. 42).

Figure 1. Brightly colored motifs and elaborate silver and amber jewelry that ‘Berber’ women occasionally wear (Becker, Citation2006, p. 43).

The qualitative analysis has detected a discursive shift from pride to profit, from symbolic goods, traditionally meant for everyday use, to commodities, strengthened by the hegemony of the tourist gaze, which indexes an orientation towards the rationality of the new economy (Dlaske, Citation2014). Textiles, for instance, stand significantly in Amazigh culture where Amazigh women are recognized for their vibrantly traditional carpets, coverings, and clothes. However, traditional Amazigh textiles started to lose part of their primary function and become more and more valued for their market worth, marking a shift from identity to commodity. Modern Moroccan EFL textbooks (Take-off Phase) seem to embody this shift from the trope of pride to that of profit. Example (8) evokes associations to nativeness and up-to-datedness, giving carpets a global outlook, and treating them as sources of economic gain, as part of the tourist industry.

Example (8):

DIALOGUE TWO

Mrs. Baker opens the catalogue. Aicha sits down next to her

They’re fantastic! Look at this one.

This one is the Salé design and this one on the right-hand page is an Amazigh carpet from the Middle Atlas. It’s handmade and not very expensive.

Oh! How beautiful! Ok Aicha, you know, they’re all gorgeous, but I need to see Mark’s opinion.

(Al-Masar, p. 86).

The exchange above demonstrates how Amazigh carpets, the emblem of pride associated with Amazigh cultural heritage, enter a new reconfiguration of profit to become cherished as a source of economic advantage. Moroccan EFL textbooks seem to be giving a material form to Amazigh consciousness (Becker, Citation2006), commodifying metaphors of motherhood (ibid), and above all valuing what Urry (Citation1992) describes as the “tourist gaze”, which “reduces ethnic minority creatives to manifestations of a collective ethnic identity automatically creating a paradox of creativity without a creative subject” (Zanoni et al., Citation2017, p. 330). Finally, while commodification reveals the ‘beautiful, “the attractive, and ‘the bright’ side of Amazigh traditional handicrafts, it also hides the hardships and sufferings Amazigh women undergo in making these commodities to meet the tourists” demand. Put differently, the folklorization and commodification of Amazigh traditional tropes conceal a bitter reality of precariousness and marginalization.

7.4. Space

Analyzing how discourse is spatialized helped form a conceptual ground for our discussion of the representation of Amazighs, where spatialization is mainly political, serving as cause and effect in power relations. One needs to understand the meanings and functions of the constructed space; in Van Leeuwen’s (Citation2008) words, we need to examine “the grammar of space” and link it to the ideological construction of “ethnicity”. The analysis reveals that visually as well as linguistically, Moroccan EFL textbooks have been saturated with meanings which reproduce the image of Amazighs as rural and mountain dwellers. This essentially pastoral perspective has resulted in various representations of Amazighs, ranging over romanticized, commodified, and gendered spaces.

7.4.1. Romanticized space

When it comes to the discursive construction of space, tribalism and rurality seem to accompany the representation of Amazighs under both folklorized and non- folklorized discourses. First, the excessive ideological construction of Amazighs as essentially rural leads to their portrayal as “virtuous children of nature” (Anderson, Citation2007, as cited in Slimi, Citation2009, p. 86), who are continuously set in a ‘background of a natural landscape containing hills, plants and grass. This stereotypical depiction not only tokenizes them but removes the complexities of the daily lives, depicting them as “unspoiled ethnic Other” (Varutti, Citation2014, p. 183).

Second, being essentially rural, a sense of “nostalgia” might be built in the way Amazighs are portrayed as “reservoirs of still-extant authenticity” (Schein, 1994, p. 72, as cited in Zhao & Postiglione, Citation2010), or a counterweight to modernity. Amazighs are portrayed as leading a “traditional” life in a setting that is on the brink of nature, contributing more authenticity and exoticism to the representation. In a similar context, Slimi (Citation2009) points out that rural depiction of ethnic groups helps draw a clear line between them and “mainstream” society, setting them apart “from the urban metropolises, from realms of education, employment and other activities of ‘civility’” (p. 87).

Third, it seems that the discourse not only depicts Amazigh social actors as “virtuous children of nature”, but also specifies the types of activities which are supposed to strengthen this representation. The most common occupation associated with Amazighs in this discourse is that of animal husbandry, depicting them as shepherded both linguistically and visually. This romanticized portrayal of space obscures the very hard reality of those inhabiting it. The same beautiful Atlas Mountains are likely to hide a plethora of socioeconomic problems such as access to health care, education, and transport infrastructure. Agyeman (1989 as cited in Bryant & Pini, Citation2011, p. 41) explains that ‘the countryside is seen in static terms; a repository of the best of what is (was) English in that it is good, pure, and untouched. However, obscured and marginalized within this representation of rurality is “the racialized Other”.

7.4.2. Commodified space

Once romanticized, Amazigh spatial arrangements can also be commodified, reduced to commodities for tourists to gaze upon. Otherwise stated, space loses its bearing and becomes fragmented; loses its meaning and becomes functional, and finally, loses its identity markers and becomes available for all and to all, giving rise to the tourist gaze, which catalogues, seals, generalizes space and its inhabitants, and increases its value in the tourist market. This makes space the subject to rational economic calculations.

The moral overtones of this economic shift permeated narratives like entertainment, tourism, and cultural diversity. However, as Zhao and Postiglione (Citation2010) explain, the commodification of space ‘constructs an image of ethnic minorities as “Others” based on unique ethnic features, such as history, customs, religion, and residence in areas popular with tourists (p. 325). Similarly, excessive commodification of space eclipses the various social problems left unsaid behind the beautiful landscape such as poverty, illiteracy, housing, water shortage, electricity, health care, etc. Commodification appears to mitigate and at times even beautify these problems.

Before we proceed any further, a note on the periodization scheme proposed by Said (Citation2019, Citation2023) should be briefly highlighted. Said’s periodization scheme includes the Germinal Phase (early 1980s to mid-1995), Critical Phase (mid-1990s to mid-2000), and Take-off Phase (mid-2000 to present). However, the preliminary analysis reveals that the boundaries between these phases are not clear-cut as folklorization of Amazighs persists throughout. One textbook, Al Massar (originally designed for Common Core student), stands out as an exception, representing Amazighs as active agents challenging mainstream stereotypes. This supports Said’s model but warrants further investigation on a larger scale.

8. The critical relevance of folklorization

Textbooks are socially and politically constructed, with selective inclusion of facts/events based on complex criteria. This process transforms content during publication (Fowler, Citation1991). Selection becomes purely ideological, providing a partial view of Amazighs, reducing their aspects to criteria like “entertainment,” “exoticism,” and “unfamiliarity.” Hence, folklore is not just reported but made, filtered, restricted, and reported for explicit/implicit purposes. Folklorization “formalizes stereotypes of the minority”, and thus, skew our view of Moroccan society as a whole (Crawford & Hoffman, Citation2018). The folklorization of Amazigh social groups, permanently encapsulated in ethnic festivals, takes a mythological form at best and a superstitious interpretation at worst. These mythological forms of festivals seem to cast Amazighs into an irrational, unreal and static world. It is in this way that folklorized representations, Crawford and Hoffman (Citation2018) argue, suggest that change in Amazigh-speaking communities is likely to present a threat to the perpetuation of Amazigh cultural heritage.

By placing the Amazigh social groups within the borders of irrationality, Moroccan EFL textbooks seem to contribute to a different kind of reason, one that contests the idea of social and economic progress. This folklorized representation is also linked to the construction of Amazigh as “nostalgic”, “traditional” and “primitive” people whose lives, knowledge, and beliefs are deeply entrenched in primitive modes of thinking.

The Amazigh culture has been transformed into a historical, mythical, and mystic discourse, detached from any ties with the present. The mythologization of Amazighs has rendered them museum-like creatures (Anderson, Citation1991). We no longer see contemporary or alive people; instead, we encounter only “dead” or “replicated” images of dead people. This explains why Amazighs are written about in the past tense, and the language used often frames them as nearly extinct. They are portrayed as imaginary people living in an imaginary world, cut off from the present and cast away in the past. Anderson (Citation1991) offers a chapter titled “Census, Map, Museum,” which he designates as the three “institutions of power” (p. 163) that are likely to constitute key elements of the “grammar” of imagined communities.

Folklorization breeds “Otherness” whereby Amazigh social actors are “Othered” by reference to what they do. Too much folklorization of their way of life would result in “characterizing”, “cataloguing” and “reduction”. These cognitive organizing principles have the power to seal, generalize, exaggerate and ultimately “Other” ethnic groups. For example, Amazighs are catalogued as “dancers” and “singers” who are singing and dancing all the time and whose actions and reactions are meant to “entertain”. This narrative echoes a common stereotypical construction of ethnic minorities as “all natural-born singers and dancers” (Zhao & Postiglione, Citation2010). The emerging EFL narrative tends to “romanticize” Amazigh social actors as “traditional” (if not primitive), “colorful” and happy people who “sing and dance, twirl and whirl, showing their happiness to be part of the homeland” (Gladney, Citation2004, p. 54).

From a CDA perspective, ethnic (mis)representations (stories) play a pivotal cognitive role in shaping individual and groups’ attitudes. While such perspectives have been given different names, their critical significance can be seen in two main instances. First, the excessive folklorization of Amazighs becomes part of people’s “figured world” (Gee, Citation2004), which refers to the linguistic and pictorial affordances people use to make sense of the world (Rogers & Rogers, Citation2004). For example, folklore episodes about Amazighs convert into “discourse models”, storylines, narratives, and explanatory frameworks that disseminate in a specific culture. According to Gee (Citation2004), “we use words based, as well, on stories, theories, or models in our minds about what is “normal” or “typical” or “the way the world should be or is” (p. 42). For this reason, instances of folklorization can be analyzed as “simplified theories of the world that are meant to help people go on about the business of life when one is not allowed the time to think through and research everything before acting” (p. 42).

Another critical insight comes from Van Dijk’s (Citation1999) social cognitive framework to the analysis of racism, where we can link folklorization to the creation and dissemination of an overall social mental model for representing, and ultimately categorizing, Amazighs. The over-occurrence of Imilchil marriage festival, for instance, forms a unique social mental model which, in addition to events, includes an evaluation of that event. Subsequent generations of Moroccan EFL textbooks keep recalling the same festival, with each time updating old models, or building new ones and authorizing selective aspects of Amazighs’ socio-cultural identity. Van Dijk’s (Citation1999) argument can also be translated to the observation that determining the significance of ethnic content, textbook designers, teachers and students, make reference to mental categories such as “frames”, “schemata”, and “general propositions”, subsumed under “stereotypes.” These unconscious mental categories serve as “pigeon-hole into which events and individuals can be sorted, thereby making such events and individuals comprehensible” (Fowler, Citation1991, p. 17).

9. Conclusion

Official school textbooks constitute what Apple (Citation2000) calls the state’s “official knowledge”. This study is a response to scholarly calls to critically explore the ways such an “official knowledge” is linguistically recontextualized, construed, represented and ultimately legitimized (or delegitimized). Zooming on Amazighs, a majoritarian minority in Morocco, the study develops a nomadic perspective that examines how the discourse of folklorization contributes to the creation of a closed set of linguistic options for the representation of Amazigh social actors.

Taking inspiration from CDA, the current study has shown that the folklorization of Amazighs equates with the dissemination of socio-political awareness into aesthetic and pedagogical texts which serve myriad of “interests”, so often legitimized under entertainment, discovery and multicultural teaching, with EFL textbooks not only creating a specific profile for Amazighs but also defining it, legitimizing it, reducing it, decontextualizing it, and above all, maintaining it in pedagogical texts and visuals.

The study argued that the content of Moroccan EFL textbooks is not an arbitrary assemblage of “facts” about Amazighs but a highly constructed congregation of beliefs, theories, and propositions. Folklore is not only manifest, and thus reported on in texts, but it is rather made, filtered, restricted, and then reported on to satisfy explicit and implicit ends. The folklorization of Amazigh social groups, permanently encapsulated in ethnic festivals, takes a mythological form at best and a superstitious interpretation at worst. These mythological forms of festivals seem to cast Amazighs into an irrational, unreal and static world. It is in this way that folklorized representations, Crawford and Hoffman (Citation2018) argue, suggest that change in Amazigh-speaking communities is likely to present a threat to the perpetuation of Amazigh cultural heritage.

Undoubtedly, further research on a larger scale is essential to examine, firstly, whether other studies that have been published in the French/Arabic language are available. The present study has mainly relied on existing studies in English. Possible studies in French or Arabic are likely to strengthen or challenge some of the arguments advanced in this study. Second, due to practical constraints, the current study runs short of providing a comprehensive analysis to other textbooks (other than the EFL ones); this could be addressed by future researchers.

Finally, it should be noted, following Said et al. (Citation2023, p. 8) that,

it is none of our intentions to claim that folklore is necessarily untrue or old fashioned, nor to demonize Moroccan EFL textbooks, or to imply that Amazigh folklore is “primitive”, “simple”, or “fake”, with no artistic, creative, or expressive dimensions (Sims & Stephens, Citation2011). Instead, we seek to criticize the institutionalized production of knowledge about Amazighs and how Moroccan EFL textbooks have contributed to the creation and maintenance of a closed system of multimodal options for the configuration and reconfiguration of Amazighs, defining and redefining canons of taste and value.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdou, E. D. (2017). Copts in Egyptian history textbooks: Towards an integrated framework for analysing minority representations. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(4), 476–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2017.1398352

- Al-Matrafi, H. (2018). The Controversy of the Term Arab/s throughout Time. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 6(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2018.61006

- Anderson, B. R. O. G. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

- Apple, M. W. (1993). The politics of official knowledge: Does a national curriculum make sense? Teachers College Record, 95(2), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146819309500206

- Apple, M. W. (2000). Official knowledge: Democratic education in a conservative age. Routledge.

- Banks, J. (1989). Multicultural education: Characteristics and goals. In J. Banks & C. Banks (Eds.), Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives (pp. 3–31). Allyn.

- Banks, J. A. (1999). An introduction to Multicultural education (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

- Becker, C. (2006). Amazigh textiles and dress in Morocco Metaphors of Motherhood. African Arts, 39(3), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.1162/afar.2006.39.3.42

- Bengio, O., & Ben-Dor, L. (1999). Preface. In O. Bengio & G. Ben-Dor (Eds.), Minorities and the state in the Arab World (pp. vii–viii). Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685854119

- Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Prentice Hall.

- Bokhorst-Heng, W. D., & Williams, J. H. (2016). (Re)constructing memory: School textbooks, identity, and the pedagogies and politics of imagining community. In W. D. Bokhorst-Heng & J. H. Williams (Eds.), (Re) Constructing memory: Textbooks, identity, nation, and state (pp. 1–24). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-509-8_1

- Boubkir, A., & Boukamhi, A. (2005). Educational reforms in Morocco: Are the new directions feasible? In A. T. Al-Bataineh & M. A. Nur-Awaleh (Eds.), International education systems and contemporary education reforms (pp. 19–36). University Press of America.

- Boukous, A. (2012). Revitalizing the Amazigh language: Stakes, challenges, and strategies. ( K. Bensoukas, Trans.). Publication of IRCAM.

- Brekhus, W. (1998). A sociology of the Unmarked: Redirecting our focus. Sociological Theory, 16(1), 34–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00041

- Bryant, L., & Pini, B. (2011). Gender and rurality. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203848289.

- Castellino, J., & Cavanaugh, K. A. (2013). Minority rights in the Middle East. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Chaibi, A. (2009). The national curriculum: Statement of values and aims of the English curriculum – Guidelines to Middle School. Available at: https://waliye.men.gov.ma/Ar/curriculum1/Documents/langue%20Anglaise.pdf

- Cheng, Q. (2013). Tradition and modernity: The discursive construction of national identity in Chinese textbooks [ Doctoral dissertation, retrieved from ProQuest dissertations and theses]. ( UMI Microform. 3556236).

- Chouliaraki, L., & Fairclough, N. (1999). Discourse in late modernity: Rethinking critical discourse analysis. Edinburgh University Press.

- Chu, Y. (2015). The power of knowledge: A critical analysis of the depiction of ethnic minorities in China’s elementary textbooks. Race, Ethnicity & Education, 18(4), 469–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2015.1013460

- Crawford, D., & Hoffman, K. E. (2018). Essentially Amazigh: Urban berbers and the global village. In K. Lacey (Ed.), The Arab-African and Islamic world: Interdisciplinary studies (pp. 117–131). Peter Lang.

- Denes, A. (2015). Folklorizing northern khmer identity in Thailand: Intangible cultural heritage and the production of “good culture. Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1355/sj30-1a

- Dlaske, K. (2014). Semiotics of pride and profit: Interrogating commodification in indigenous handicraft production. Social Semiotics, 24(5), 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2014.943459

- Edwards, J. (2009). Language and identity: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- El Aissati, A. E. (2001). Ethnic identity, language shift, and the amazigh voice in Morocco and Algeria. Race, Gender & Class, 8(3), 57–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41674983

- Ennaji, M. (2005). Multilingualism, cultural Identity, And Education in Morocco. Springer.

- Ennaji, M. (2014). Recognizing the Berber language in Morocco: A step for democratization. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 15(2), 93–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43773631

- Fowler, R. (1991). Language in the news. Routledge.

- Gee, J. P. (2004). Discourse analysis: What makes it critical? In R. Rogers (Ed.), An introduction to critical discourse analysis in education (pp. 19–50). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Gladney, D. C. (1994). Representing Nationality in China: Refiguring majority/minority identities. The Journal of Asian Studies, 53(1), 92–123. https://doi.org/10.2307/2059528

- Hale, H. E. (2004). Explaining ethnicity. Comparative Political Studies, 37(4), 458–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414003262906. Sage Publications.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1985). Introduction to functional grammar. Arnold.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. (2004). An Introduction to functional grammar. Arnold.

- Harris, A. S., & Findley, M. G. (2014). Is ethnicity identifiable? Lessons from an experiment in South Africa. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 58(1), 4–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002712459710

- Hart, D. M. (1999). Scratch a Moroccan, find a Berber. The Journal of North African Studies, 4(2), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629389908718359

- Hart, D. M. (2000). Tribe and Society in Rural Morocco. Psychology Press.

- Hsieh, S. (2019). Representing aborigines: Modelling Taiwan’s ‘mountain culture. In K. Yoshino (Ed.), Consuming Ethnicity and Nationalism: Asian experiences (pp. 89–111). Routledge.

- Janks, H. (1997). Critical discourse analysis as a research tool. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 18(3), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/0159630970180302

- Jiménez-Tovar, S., & Lavička, M. (2019). Folklorized politics: How Chinese soft power works in Central Asia. Asian Ethnicity, 21(2), 244–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2019.1610355

- Joseph, J. E. (2004). Language and identity : National, ethnic, religious. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Age International Publishers.

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications.

- Lauritsen, J. A. (2006). Governing literacy: A critical discourse analysis of the United Nations decades of literacy, 1990–2000 and 2003–2012 [ Doctoral dissertation]. Cornell University, The Graduate School of Cornell University.

- Leeman, J., & Martínez, G. (2007). From identity to commodity: Ideologies of Spanish in Heritage language textbooks. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 4(1), 35–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427580701340741

- Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis : A multimodal introduction. SAGE.

- Maddy‐Weitzman, B. (2001). Contested identities: Berbers, ‘Berberism’ and the state in North Africa. The Journal of North African Studies, 6(3), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629380108718442

- Maddy-Weitzman, B. (1999). The Berber question in Algeria: Nationalism in the making? In O. Bengio & G. Ben-Dor (Eds.), Minorities and the State in the Arab World (pp. 29–52). Lynne Rienner Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781685854119-003

- Matthiessen, C., Teruya, K. T., & Lam, V. (2010). Key terms in systemic functional linguistics. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- McClanahan, E. (2006). Discourse and the North African Berber identity: an inquiry into authority [ Doctoral dissertation, school of interdisciplinary studies]. Western College Program, Miami University Oxford. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_etd/send_file/send?accession=muhonors1144794306&disposition=inline

- Merolla, D. (2020). Amazigh/Berber literature and “Literary space”. a contested minority situation in (North) African literatures. In T. Ojaide & J. Ashuntantang (Eds.), Routledge handbook of minority discourses in African literature (pp. 27–47). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429354229-5

- Mugaddam, A. H., & Aljak, N. S. (2013). Identity construction and negotiation through an EFL syllabus in Sudan. Arab World English Journal, 4, 78–94.