Abstract

Community participation is a necessary ingredient for infrastructure projects to enhance the level of residential satisfaction and to improve its success rate. Nevertheless, there are socioeconomic and demographic factors, which determine the level of participation in such projects. This paper examines these factors in the residential neighbourhoods of Akure, Nigeria. Data were collected through structured questionnaires and observations. They were subjected to Single-Factor Descriptive Analysis and Categorical Regression Analysis. It showed that stages of participation in housing development, level of education, tenure status, marital status, gender, monthly income, household size, sources of finance, and employment status were significant predictors of levels of community participation in this context, with the exception of age. A p-value of 0.034 was observed indicating that the model of the regression was significant at 0.05. The paper concludes by providing implications, considering the factors for developing strategies for community participation in infrastructure provision in Nigeria.

Public Interest Statement

Community participation in housing development is fast becoming a global phenomenon because the people that are directly affected by such developments are increasingly being recognized as an essential part of the process, in order to achieve enhanced benefits such as residential satisfaction. Providing housing environments and infrastructure that does not consider the actual needs of the users usually leads to unsuitable environments for residents. It is however still an uncommon practice in Nigeria, and there is a need to provide the necessary data needed for incorporating it into Nigerian housing policies. Thus, there is a need to understand the characteristics of the beneficiaries. Socioeconomic characteristics of residents can determine the level of their participation in infrastructure provision. This paper further provided implications, considering the factors for developing strategies for community participation in infrastructure provision in Nigeria.

1. Introduction

It has become increasingly essential to evaluate community participation in infrastructure provision in developing countries. This is because infrastructural facilities in conjunction with the house itself make living habitable for its residents. Housing infrastructure is an important aspect of housing development because the house cannot stand-alone; it requires basic services and infrastructure to function. In fact, one of the most important objectives of economic development is the improvement of production capacity and welfare through availability of sustainable and reliable infrastructure (Obiegbu, Citation2008). However, community participation is an exception rather than the norm in Nigeria due to frequent top-down and paternalistic approach to infrastructure provision.

Due to the nature of neighbourhoods and communities in addition to fluctuating government policies, the factor of change can be inevitable. These changes can also be in the form of community development, by actors such as government agencies. According to Local Government Commission of Scotland (LGC, Citation2015), community change processes affect residents primarily; therefore, they should be allowed to get involved in determining such changes. This is one of the main reasons behind the notion of community participation in housing development.

Cole (Citation2007) observed that in order to get community support for developmental projects, community participation and empowerment are necessary ingredients. Therefore, it is necessary for communities to participate in the planning, provision and maintenance of infrastructure. Community participation according to Samah and Aref (Citation2011) is the engagement of people in the activities within their community. Likewise, community participation as claimed by Leung (Citation2005) is an aspect of community development intended at increasing involvement of residents of the community in housing development, management and community building. Janine (Citation2006) stated that the lack of appropriate community participation in housing infrastructure development would result in failure to establish an authentic and empowering people-centred development. This is because people should be at the centre of developments in order to ensure that such development meet their identified needs. Thus, such identification of needs should not be done through abstraction, but developed within the given context (Till, Citation2005). Consequently, LGC (Citation2015) affirmed that in the end, programmes and projects that develop from an informed public, guided by professionals, are likely to be more creative and locally appropriate than the programmes where the public is excluded from the planning process.

Hence, the strategies implemented to produce what can be considered successful community participation is an aspect not thoroughly considered in the development process (Janine, Citation2006). This is especially so in developing countries like Nigeria. Nuttavuthisit, Jindahra, and Prasarnphanich (Citation2015) supported this claim arguing that the detailed participatory mechanisms that may operate within certain contexts (especially in developing countries) remain under-researched. This is evident in situations where development authorities attempt to provide and maintain infrastructure in neighbourhoods without attempting to identify the actual needs of residents. In such cases they usually assume, and might not successfully meet the needs of the residents of such communities. Thus, this could inhibit the communities from getting involved with government in other aspects of development. Community participation is expedient to ensure that both government and resident communities grow closer to each other, especially for infrastructure provision (Nhlakanipho, Citation2010). This aspect is very vital because such approach empowers the community and ensures that the government schemes are successful in achieving their set goals.

Therefore, to develop and implement strategies for community participation in infrastructure development processes, it is expedient to identify its influencing factors. Although several research studies (Bremer & Bhuiyan, Citation2014; Chengcai, Linsheng, & Shengkui, Citation2012; Elsinga & Hoekstra, Citation2005; Leung, Citation2005; Markovich, Citation2015; Plummer, Citation2000; Yau, Citation2011) have evaluated community participation in housing management and services and the factors influencing them especially in developed countries, little or no empirical work has been done in less developed countries such as Nigeria. It is not advisable to assume that the findings from these developed countries are automatically generalizable to less developed countries. Therefore, it is necessary for similar research to be conducted countries like Nigeria since the state of affairs in these developed countries are not identical to less developed countries.

This study focuses on identifying the factors that influence the level and extent of community participation in the provision of infrastructure in Akure, Nigeria. This is to discover the levels of community involvement in infrastructure provision and the determining factors in Akure, Nigeria. It therefore examined the socioeconomic characteristics of respondents, examined their levels of participation in infrastructure provision, and sought a relationship between them. Previous studies (Elsinga & Hoekstra, Citation2005; Markovich, Citation2015; Plummer, Citation2000) studied the factors that influence community participation in service delivery and community development practices in developed countries especially. Therefore, this research showed how socioeconomic characteristics determine community participation in infrastructure provision in a developing country context. This will provide a basis to argue for involving communities in infrastructure planning and implementations by government agencies and policy makers where necessary. The reminder of the paper is as follows. The next sections present the literature review, study area, conceptual framework, methodology, results and discussions, followed by conclusions and policy implications of the study.

2. Literature review

The concept of community participation is still an exception rather than the norm in several developing countries like Nigeria. King and Hickey (Citation2016) corroborated this by arguing that in much of sub-Saharan Africa, the progress of democratization and developments remain seriously inhibited by the persistence of neo-patrimonial political systems despite the extensive adoption of democracy and increased economic growth. This shows that community participation, being a democratic process of development is also hampered by the political system. However, with proper research like the one presented in this study, the policy makers in the political system could be advised to adopt this approach. This is by highlighting its benefits and advantages, while presenting the issues that can influence community participation in infrastructure development.

While community participation in infrastructure provision is considered very important, several conditions determine its success. These conditions are referred to as factors in this study. A factor refers to something that contributes to or has an influence on the outcome of another thing (Encarta Dictionaries, Citation2009). Factors that are usually considered in the study of community participation are socioeconomic in nature, but other aspects such as housing characteristics are often not considered. Churchman (Citation1987) observed that socioeconomic status has been the most common characteristic considered to be of interest to determine participants in housing development. Yau (Citation2011) highlighted gender, age, educational level, tenure status and household income as factors that influence participation in housing management. Bremer and Bhuiyan (Citation2014) also observed that tenure status and income level influences community participation in community-led infrastructure development. Furthermore, Chengcai et al. (Citation2012) also observed that educational and income level influences participation in ecotourism. According to Plummer (Citation2000), factors affecting community participation include, but not limited to employment status, education, stage of service delivery and quality of service delivery. Likewise, Elsinga and Hoekstra (Citation2005) and Markovich (Citation2015), found that homeowners are more likely to be involved in the community development processes than residents who are not.

Most of these studies considered socioeconomic variables in their study of participation in several spheres, and it would be fitting to identify which of them applies to community participation in infrastructure provision. However, in this study, marital status, stage of participation in housing development, and sources of finance are considered along with these socioeconomic variables due to their potential to influence community participation. This is because, it is necessary to determine whether these factors could determine the level of community participation in infrastructure provision as well. In addition, it is necessary to determine whether the findings from developed countries in this area of research could be applicable to less developed countries such as Nigeria.

The key issue about this study is that, community participation is important in the provision of infrastructure for communities in Nigeria; but this has not been the case because government policies and practices encourage mostly top-down housing development processes. In order to reverse the trend, there is a need to understand how socioeconomic characteristics of communities determine the level of community participation. This would be necessary to plan for community participation in developing countries like Nigeria. More so, approaches developed with little understanding of local contexts may not yield any motivation for community participation (Nuttavuthisit et al., Citation2015).

3. The study area

Akure is the capital city of Ondo State in South-Western Nigeria. It is a medium sized city with population of 360, 268 people according to the 2006 National Population and Housing Census (FRN, Citation2009). Using 3% yearly increase, the population of the city for 2016 will be 484, 170 people. Hence, with the population increase, it is expected that the challenges of housing would increase. Akure is located about three hundred and eleven kilometres North East of Lagos, about three hundred and seventy metres above sea level. Additionally, the state has been classified as an oil producing state while Akure has been classified as a Millennium Development City. All these factors contribute to influence population growth of the city.

4. Conceptual framework of the study

The study conceptualized levels of community participation in infrastructure provision as influenced by socioeconomic characteristics of the residents as shown in Figure . Levels of community participation in infrastructure provision were construed as the dependent variable while the socioeconomic characteristics were the independent variables. It hypothesized that these variables would influence the levels of community participation in infrastructure provision. The dependent variable, levels of community participation in infrastructure provision was construed as multifaceted: as self-management, conspiracy, informing, diplomacy/dissimulation, conciliation, partnership and empowerment. Participation should influence residential satisfaction, though it is beyond the scope of this study.

5. Methodology

This study relies on primary data collected through structured questionnaire survey and physical observations. The structure of the questionnaire is according to the themes of the study in order to make the sequence of questions easy to follow, thus easy for the respondents to read. The themes of the study are socioeconomic characteristics of respondents, and the levels of community participation in infrastructure provision. Since the questionnaire is standardized, it ensured that respondents answered to similar questions. The first section relates to the first theme and is about socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents, while the second section is about levels of community participation in infrastructure provision.

The socioeconomic variables were defined as shown in Table , and the respondents were asked to select the correct options from the ones provided in the questionnaire. The levels of community participation as defined Choguill (Citation1996) were adapted to this study. Choguill (Citation1996) was chosen for this study because it identified the levels of community participation specifically for underdeveloped countries like Nigeria. The adapted levels in ascending order include self-management (1: lowest), conspiracy (2), informing (3), diplomacy/dissimulation (4), conciliation (5), partnership (6), and empowerment (7: highest). The above denote how the levels of community participation in infrastructure provision was defined for this study. In Choguill (Citation1996), diplomacy and dissimulation were two different levels. However, for this research, they were used as one single level to suit the study area because of their similarities, in which case the residents are made to believe that they influence decisions, which had been made by others. The respondents were asked to select the option that corresponds with their level of community participation in infrastructure provision.

Table 1. Socioeconomic, demographic and housing characteristics of respondents in the study area

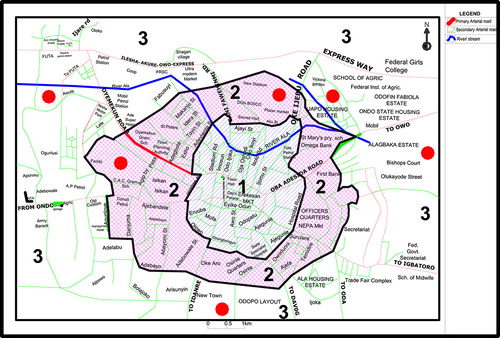

The study areas includes the transitional and peripheral zones of Akure as defined by Owoeye and Omole (Citation2012) shown in Figure . They developed these concentric zones through an application of the Burgess Theory of Concentric Zones to Akure city. Zone 1 is the core of Akure, which is characterized as slum and by spontaneous traditional developments and has been fully developed for several decades. Next to this is Zone 2, which is the transitional zone, and Zone 3 is the peripheral zone, which is farther from the core of the city. This study is limited to households living within the buildings located in the transitional and peripheral concentric zones of the city. This is because housing developments in these zones are more recent and the residents are more likely to provide all the information required for this research. Figure also shows the locations of the areas within each of the concentric zones that make up the study area (represented with large dots).

Figure 2. Road map of Akure with overlay of the concentric zones showing the study areas

Copies of the questionnaire were administered on the transitional and peripheral concentric zones of Akure. The number of housing units in the transitional zone is 1,571 buildings, while for the peripheral zone; it is 3,878 buildings, which brings the total to 5,449 buildings. The sample size for the study is three hundred and fifty-nine, which was generated using Sample Size Calculator, with a confidence level of 95%. This number of questionnaires for each of the zones was determined according to the proportion of their contribution the population size. Simple random sampling was used to select the houses that were studied and heads of households in each house was the basic focus of questionnaire administration and other research enquiries. The percentage return for the questionnaires was 84.7% (304 copies), which was deemed as sufficient for the study. Single-Factor Descriptive Analysis and Categorical Regression Analysis were used in the analysis for this research.

Prior to the fieldwork, a pilot survey was conducted in the study area. This was done to identify possible problems that might arise from the questions during the field survey and if there are any problems with the overall structure of the questionnaire, it may be necessary to amend it at the pilot testing stage. Thus, it was carried out to pre-test the research instrument and assist with the clarity of terms used. Twenty questionnaires were used for the pilot testing in the study area. These were used to run the Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability Test for this study. In order to facilitate meeting of respondents, data was collected during morning and evening hours as well as on weekends, at their homes. The outcome was of assistance in reframing the questionnaire and other research instruments as necessary.

The Cronbach’s Alpha test for reliability was conducted with the research questionnaire for this study. The Cronbach’s Alpha Test yielded a value of 0.788, which means that the sections require no revision. This is because, according to George and Mallery (Citation2003), no revision is required for the questionnaire if the value is 0.7 and above.

6. Result and discussions

6.1. Socioeconomic characteristics of respondents in the study area

In order to have a better understanding of the residents under study, it is necessary to present the frequency distribution of their characteristics as shown in Table . Males are household heads in almost two-thirds (66.4%) of the households in the study area and majority (83.4%) of them are between thirty-one and sixty years of age. Over half (51.9%) of the respondents earn between N50,000 (about $138) and N150,000 (about $416) monthly, while almost three-fourths of them (73.6%) are graduates of higher institutions of learning, which implies that the level of education in the study area is very high. Majority of the respondents (88.2%) are employed in one form or another and have a source of income and over four-fifths (82.6%) of them are married. Over half (51.3%) live in their privately or family owned houses, while for the majority (70.8%), the household size is between 3 and 6 persons. Over half of the respondents (52.6%) were involved in the development of the houses where they live, while almost three-fourths (70.7%) financed their housing through personal savings.

6.2. Levels of community participation in infrastructure provision

It is pertinent to understand the levels of community participation in infrastructure provision in the study area. See Table . A proportion of 57.2% of the respondents indicated that they provide infrastructure in their neighbourhood through self-help efforts without any support from the government, 27.6% indicated that the government provide infrastructure without informing the residents, while 3.2% indicated that government usually informed the residents about such proposed projects. A proportion of 3.9% of the respondents indicated that government consult the community about proposed infrastructure projects but their opinion usually do not count, and 4.6% indicated that government plans the projects but allow the residents to have genuine inputs before construction. A proportion of 2.9% of them indicated that there is a partnership and joint/equal decision between the community and the government, and 0.3% indicated that community have more power and influence over infrastructure projects than the government. This implies that majority (57.2%) of the respondents agree that they are neglected by the government regarding infrastructure provision in their neighbourhood. Moreover, since the neighbourhood infrastructure is important to them, they resort to providing the infrastructure through self-help efforts either as individuals or as a community rather than waiting endlessly for the government to intervene. Preliminary information revealed that, though government provides roads and drainage for few parts of the area, majority of the areas in the neighbourhood do not benefit from such efforts. In fact, the residents opened up several of the roads in the study area instead of the government. It also revealed that throughout the study area, there were no public mains for water supply and the residents resort to self-help efforts to access water for domestic use. Likewise, the communities organize themselves to employ private security guards to safeguard their lives and properties, as a response to government negligence.

Table 2. Level of community participation in housing infrastructure

6.3. Predictors of level of community participation in infrastructure provision

The research investigated the predictors of the level of community participation in infrastructure provision in the study area. Identifying these predictors was viewed as necessary for this research. Hence, Categorical Regression was carried out using optimal scaling method with the criteria for convergence set at 0.00001. In carrying out the analysis, the level of community participation in the provision of infrastructure was the dependent variable, while gender, age, marital status, monthly income, highest level of education, employment status, tenure status, stages of participation in housing development, household size, and sources of finance were the independent (predictor) variables. Stage of participation in housing development is the housing variable included in this research. The result shows that not much of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the regression model with Multiple R = 0.563, and R 2 = 0.371. See Table . This implies that the regression model explains 37.1% of the variance in the level of participation in infrastructure in the study area. The reason for the low value could be other factors that influence community participation in infrastructure provision that are beyond the scope of this research. The ANOVA result shows that F = 1.595, df = 35, p = 0.034, which also implies that the regression model is statistically significant at 0.05. This shows that all the variables together have significant relationship with the level of participation in infrastructure provision. This is in agreement with the findings of Churchman (Citation1987) which observed that socioeconomic variables significantly influence participation in housing development.

Table 3. Model summary and coefficients of socio-economic predictors of participation in housing infrastructure

Out of the ten variables used, nine were significant predictors of the level of participation in infrastructure provision. As shown in Table , the variables in the order of their importance include stage of participation in housing development (β = 0.270), level of education (β = 0.268), monthly income (β = −0.254), employment status (β = −0.232). Others are source of finance (β = 0.216), household size (β = −0.216), tenure status (β = −0.189), marital status (β = 0.188), and gender (β = −0.174). The result implies that most of the socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents contributed to community participation in the provision of infrastructure.

The strongest significant predictor however, is stage of participation in housing development. This implies that in this context, stage of participation in housing development contributed the most in predicting the level of participation in housing development. This was not surprising because, it is during the stages that the residents familiarize themselves with the neighbourhood and with their would-be neighbours before they eventually move in to live there. This assists in making them an integral part of the community. This is different from renters that do not have the opportunity to familiarize themselves with the community before moving in, and therefore may not be quickly integrated with them. This is in consonance with the findings of Plummer (Citation2000) that observed that stage of service delivery influences participation.

The respondents’ level of education was also a significant predictor in this model and this was not surprising. The level of education in this context was very high and educated people tend to know the importance of being involved in shaping how their neighborhood changes. Educational level also tends to make people to be curious of goings-on in their neighbourhoods and increases their willingness to participate. This agrees with Yau (Citation2011) and Chengcai et al. (Citation2012) which observed that level of education influences level of participation.

Monthly income was also a significant predictor of level of participation in this context. This was expected because, when people participate in infrastructure provision, money is usually involved. In addition, this influences their decision to be involved in infrastructure provision in their neighbourhood. This agrees with Yau (Citation2011), Chengcai et al. (Citation2012), Bremer and Bhuiyan (Citation2014), which observed that income influences level of participation. Employment status was also a significant predictor of the level of participation in infrastructure provision. This is expected because; it is when people are employed that they can earn income. Hence, with higher income comes the possibility of owning a house as is common in this part of the world. In addition, people with higher income tend to own vehicle and this would increase their interest in being involved in developing the physical infrastructure in their neighbourhoods. This enables them to be able to achieve several of their goals in life and they would usually be interested in developing their neighbourhood. This agrees with the findings of Plummer (Citation2000), which observed that employment status influences level of participation.

Source of finance was also a significant predictor in this model and this was not surprising. This is because, when people have access to money to finance a house, they could think about participating in the design of such houses. In this context, majority (70.7%) of the respondents financed their houses through personal savings, while the remainder financed their houses through one form of borrowing or another. This shows that most were able to save for their housing. Household size is also significant predictor in this context. This is expected because people desire the best living environment for their families.

Tenure status was also a significant predictor in this model and this was not surprising. This is because tenure status of respondents goes a long way in determining residents’ interest in being involved in infrastructure provision. People are more willing to be involved in provision of infrastructure when they are homeowners than when they are renters, and the reason is not far-fetched. Homeowners are less likely to move from the neighbourhood unlike renters, and their interest in its development would be higher than renters, who are characterized with more mobility. Preliminary information discovered that even though the community associations were meant for all residents, almost all the people that attend regularly are homeowners. Tenure status predicts the level of participation in infrastructure provision and this agrees with the findings of Yau (Citation2011) and Markovich (Citation2015).

Marital status is also a significant predictor in this context and this was expected. Marital status is significant because most (82.6%) of the respondents are married and this influences the level of participation in infrastructure provision. People that have families tend to desire to have a befitting place of abode for their families to live in; and this influences their decision to participate in deciding house such environments would be shaped.

Similarly, gender was found to be a significant predictor of level of participation in infrastructure provision in this research, and this is in agreement with the findings of Yau (Citation2011). Majority of the respondents (66.4%) are male, who are also household heads, as is common in the Nigerian culture. In addition, usually household heads (mostly males) are involved in participation in the study. In spite of the fact that women also participate in housing development in the study area, they are in the minority. Preliminary investigation reveals that men and women alike, as well as youths and older residents are part of the community organization and development; and they all are involved in the community development.

The non-significant predictor is age of respondents (p = 0.871). Age was not found to be significant in this context, and this finding differs from that of Yau (Citation2011), which observed that age is a factor that influences participation. The reason that age is not significant is that because, majority of the respondents (83.4%) are between the ages of thirty-one and sixty years, and these are the very active years of life. In addition, in this context, all adults are eligible to participate as long as they are resident in that community. Thus, the question of age determining peoples’ level of participation in infrastructure provision does not arise.

This study highlighted the relationship between socioeconomic characteristics of respondents and community participation in infrastructure provision. However, this study has some limitations. The regression model used in this study could explain a low (37.1%) percentage of the variation in participation in house design in this context. However, other variables beyond the scope of this study could explain the remaining percentage. Another limitation could be the use of sampling for the research, in which case other samples from the same research population could generate a different result.

7. Conclusion and implications of the result

This paper examined the factors that are predictors of level of participation in infrastructure provision. It assessed how socioeconomic factors influence the levels of community participation in the provision of infrastructure. The study showed that self-help is the major source of infrastructure in the study area. This shows that the government neglect of communities infrastructure needs is high in the study area, and they therefore resort to providing the necessary infrastructure for themselves.

The study also showed that some of the socioeconomic variables are indeed significant predictors of participation in infrastructure provision, confirming what some previous studies have found out. This study has been able to provide some answers to this in addition to conducting further research on other variables. It showed that stages of participation in housing development, is the strongest significant predictor of level of participation in infrastructure provision; and that other significant predictors are level of education, tenure status, marital status, gender, monthly income, household size, sources of finance, and employment status. However, age was not significant a predictor in this context.

The predictive power of the regression model in the level of participation in infrastructure was found to be low with R 2 of 0.371. This relationship is also significant since p-value = 0.034. This means that these variables together significantly predict the level of community participation in infrastructure provision. This implies that in developing strategies for community participation in infrastructure provision, socioeconomic factors should be considered in order to enhance the success of such endeavours.

This study generates information base to inform housing policy in Nigeria. It should assist in development of strategies for community participation in infrastructure provision since the influencing factors are known. For instance, since employment status is a significant predictor in this context, government authorities could use it as a criterion to determine the level of participation in the design of housing projects. This is because they would have the financial means meet their obligations in infrastructure provision process. Tenure status could also be used, where owner-occupiers could have a higher level of participation than other groups because they would live there in the longer term and because of their status as owners. However, this does not imply that other groups should not participate in the process. This is fundamental in realizing the goals of community participation in infrastructure provision, and contributes immensely to achieving higher residential satisfaction. Therefore, policy makers in Nigeria should adopt community participation in infrastructure provision because it has the potential to enhance sustainable housing development and encourage people-centred development.

However, it is possible for the result to be different in another context. Therefore, further research is required in order to examine this relationship in order to discover what the result would be in other contexts. What other variables can significantly predict the level of participation in infrastructure provision? Are these results peculiar to this context, or will it be the same in other similar contexts? Answering such questions in future research will be required by developers and policy makers in the development of infrastructure for communities. It is through such knowledge that the process of infrastructure provision could be refined as necessary. Consequently, in developing strategies for community participation in infrastructure provision, it is necessary to identify the influencing factors in order to come up with comprehensive strategies that would work. This is fundamental if the goals of community participation and community development are to be realized.

Funding

The authors received no direct funding for this research.

Acknowledgments

This research is a part of an ongoing Doctor of Philosophy Research on Residents’ Participation in Housing. The authors wish to thank the Administration of the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria for providing the facilities and support that made this research possible.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alexander Adeyemi Fakere

Fakere, Alexander Adeyemi is a lecturer at the Department of Architecture, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. He obtained his BSc degree at Imo State University, Owerri in 2001. He also obtained his MTech and PhD degrees at the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. His research interests are participatory design in housing, residential satisfaction, housing settlement studies, sustainability, behavioural architecture, and urban design. This article is of interest to policy makers and government authorities in Nigeria and Africa because it aims to justify the reason that beneficiaries must be part of the process planning and implementation of infrastructure projects.

Hezekiah Adedayo Ayoola

Ayoola, Hezekiah Adedayo, is a lecturer at the Department of Architecture at the Federal University of Technology, Akure. He obtained his BTech Degree at Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomosho, Nigeria. He also obtained his MSc and PhD degrees at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. His areas of interest are social milieu in poor neighbourhoods and housing settlement studies.

References

- Bremer, J. , & Bhuiyan, S. H. (2014). Community-led infrastructure development in informal areas in urban Egypt: A case study. Habitat International , 44 , 258–267.10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.07.004

- Chengcai, T. , Linsheng, Z. , & Shengkui, C. (2012). Tibetan attitudes towards community participation and ecotourism. Journal of Resources and Ecology , 3 (1), 8–15.10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2012.01.002

- Choguill, M. B. G. (1996). A ladder of community participation for underdeveloped countries. Habitat International , 20 (3), 431–444.10.1016/0197-3975(96)00020-3

- Churchman, A. (1987). Can resident participation in neighbourhood rehabilitation programs succeed? Israel’s project renewal through a comparative perspective. In I. Altman & A. Wandersman (Eds.), Neighbourhood and community environments (pp. 113–162). New York, NY: Plenum Press.10.1007/978-1-4899-1962-5

- Cole, S. (2007). Tourism, culture and development: Hope, dreams and realities in East Indonesia . Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

- Elsinga, M. , & Hoekstra, J. (2005). Homeownership and housing satisfaction. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment , 20 , 401–424.10.1007/s10901-005-9023-4

- Encarta Dictionaries . (2009). Definition of factor . Albuquerque, NM: Microsoft Encarta, Microsoft Corporation, USA.

- FRN (Federal Republic of Nigeria) . (2009). The 2006 national population and housing census. FRN Official Gazette , 2 , 96.

- George, D. , & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for windows step-by-step: A simple guide and reference (11.0 Update, 4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Janine, D. (2006). Assessing public participation strategies in low-income housing: The Mamre Housing Project ( Masters Diss.). Stellenbosch University of Stellenbosch, South Africa.

- King, S. , & Hickey, S. (2016). Building democracy from below: Lessons from western Uganda. The Journal of Development Studies , 53 (10), 1584–1599. doi:10.1080/00220338.2016.1214719

- Leung, C. C. (2005). Resident participation: A community-building strategy in low-income neighbourhoods (p. 38). Cambridge: Joint Centre for Housing Studies of Havard University.

- Local Government Commission . (2015). Public participation in community planning. Retrieved October 22, 2015, from http://www.lgc.org/participation-tools-better-community-land-use-planning

- Markovich, J. (2015). They seem to divide us: Social mix and inclusion in two traditional Urbanist communities. Housing Studies , 30 (1), 139–168. doi:10.1080/02673037.2014.935707

- Nhlakanipho, S. (2010). An investigation of community participation trends in the rural development process in Nquthu, Northern KwaZulu-Natal (Masters Diss.). University of Zululand, South Africa.

- Nuttavuthisit, K. , Jindahra, P. , & Prasarnphanich, P. (2015). Participatory community development: Evidence from Thailand. Community Development Journal , 50 (1), 55–70.10.1093/cdj/bsu002

- Obiegbu, M. E. (2008). Urban infrastructure and facilities management. In V. C. Nnodu , C. O. Okoye , & S. U. Onwuka (Eds.), Urban environmental problems in Nigeria (pp. 55–70). Nimo: Rex Charles and Patrick.

- Owoeye, J. O. , & Omole, F. K. (2012). Effects of slum formation on a residential core area of Akure, Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Sciences , 1 (3), 159–167.

- Plummer, J. (2000). Municipalities and community participation: A sourcebook for capacity building research for department for international development . London: EarthScan.

- Samah, A. A. , & Aref, F. (2011). The theoretical and conceptual framework and application of community empowerment and participation in processes of community development in Malaysia. Journal of American Science , 7 (2), 186–195.

- Till, J. (2005). The negotiation of hope. In P. B. Jones , D. Petrescu , & J. Till (Eds.), Architecture and participation (pp. 23–41). London: Spon Press.

- Yau, Y. (2011). Collectivism and activism in housing management in Hong Kong. Habitat International , 35 , 327–334. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.11.006