Abstract

This paper considers the contention that higher density neighbourhoods can lead to enhanced liveability, and examines the idea and role of neighbourhood to achieve this aim and policy goal. It reports on the findings from fifty-seven in-depth qualitative interviews. Residents interviewed all currently live in attached dwellings in four Auckland neighbourhoods. As is the case across much of Auckland, these areas are all experiencing considerable density increases. Conclusions drawn indicate that if higher density living is to be embraced in future neighbourhoods, the changing ways that residents are defining their neighbourhoods must be acknowledged and incorporated in to urban planning policy and strategy directives. The changing spatial role that neighbourhood amenities play in meeting the liveability expectations of residents must also be understood and provided for if enhanced liveability is to be achieved at higher densities.

Public Interest Statement

Large cities in Australia and New Zealand have urban policies that locate new development around existing suburban transit centres at higher densities. The result is a significant increase of people living at densities in apartments and terrace houses. To be successful, research shows that higher density neighbourhoods must be complemented with a strong sense of identity, and appropriate amenities that enhance liveability. Two issues are examined: how do residents living at higher density in suburban locations define their idea of “neighbourhood”, and to what extent do associated amenities enhance liveability? This is explored through interviews with residents living at higher density in Auckland. We found that where higher density living is embraced, the variable ways that residents define and use their neighbourhoods requires a more nuanced urban design response. Moreover, findings support the notion that local amenities and neighbourhood walkability significantly contribute towards the experience of liveability. This underscores the importance of investment in public spaces and amenity for higher density housing to be successful.

1. Introduction

Many Australia and New Zealand cities have well-established urban growth management strategies to curtail low density sprawl and accommodate urban growth through intensification, underpinned by the concepts of sustainability and resilience thinking (Clark, Lloyd, Wong, & Jain, Citation2002). Intensification strategies typically involve establishing an urban boundary to prevent sprawl, and directing future development at higher densities to peripheral “greenfield” areas within the boundary, and intensification at existing urban centres. The latter involves intensified development at, and around, existing transit and retail centres of varying scales (local, town and metropolitan) spread across the urban area, as “transit-oriented development”.

Urban intensification over the past two decades has led to significant increases in the provision of higher density housing, using attached housing types such as terrace houses and apartments, in most large cities in Australasia (Auckland Council, Citation2012; Australian Government, Citation2012; Buxton & Tieman, Citation2004; CHRANZ, Citation2011; Randolph, Citation2006; Yeoman & Akehurst, Citation2015). In Australia, this change is seen by Randolph (Citation2006) as “a revolution” where “little over a generation ago, living in flats (apartments) was a minority pastime” (p. 473). The designation of intensified development at town centres spread across urban regions, is also leading to higher density development in suburban contexts. In Auckland, New Zealand, for example, while the provision of apartments in the CBD has increased 28% over the past ten years, there has been a 173% increase in suburban areas (CABRE, Citation2017).

In contexts where lower density suburban lifestyles remain an aspirational goal (Bryson, Citation2017; Haarhoff et al., Citation2012), a key issue is the extent to which living at higher density in attached forms of housing will deliver liveability for residents? Indeed, newer iterations of urban intensification policies argue that higher density enhances liveability (Haarhoff, Beattie, & Dupuis, Citation2016). For example, the Auckland Plan (Auckland Auckland Council, Citation2012, p. 2) aims to establish the “world’s most liveable city”, where:

higher-density neighbourhoods offer opportunities to create healthy stimulating and beautiful urban environments … (that) enhance social cohesion and interaction by attracting people across all demographic groups to a mix of cafes, restaurants, shops, services and well-designed public spaces … meeting the full spectrum of people’s everyday needs … (Auckland Auckland Council, Citation2012, p. 42)

Delivering enhanced liveability in the context of higher density depends as much on the quality of the housing as it does on the quality, accessibility and amenity of the neighbourhood context (Haarhoff et al., Citation2016). Fincher and Gooder (Citation2007) underscore this understanding from their study of housing in Melbourne, finding that “more than for single family housing … medium density housing means home outside the domestic space of family privacy … it means a lived experience of belonging to an immediate community” (Fincher & Gooder, Citation2007, p. 181). In a similar way, Haarhoff et al. (Citation2016, p. 13) concluded from a study of living at density in Auckland that “the local environment contributes to urban resident’s sense of housing satisfaction, and hence the perception of liveability”.

The role of public spaces and associated amenities of the neighbourhood (such as parks, shops, schools, and so on) take on increasing significance as density increases. In a sense, the amenity of the private backyard typical to lower density suburban development is replaced by the shared amenity of public spaces at higher densities. We argue that the perceived public amenity of higher density neighbourhoods will increasingly be a key factor considered in making housing choices aligned with life-stage, affordability and other personal circumstances (Allen, Citation2016; Foord, Citation2010; Haarhoff et al., Citation2016; Yeoman & Akehurst, Citation2015).

Two questions are raised in this paper concerning the enhanced role of neighbourhoods in the context of higher density living: how do residents conceptualise neighbourhood, and to what extent does neighbourhood amenity contribute towards their perceptions of liveability? This is approached in two ways: firstly, by identifying how residents perceive the idea of neighbourhood, and secondly, by investigating the role of neighbourhood amenities in delivering perceived liveability outcomes. We report on findings from a survey of residents living at higher density in four Auckland neighbourhoods designated for intensification.

2. The idea and role of neighbourhoods

Minnery, Knight, Byrne, and Spencer (Citation2009) point out that “the idea of the ‘neighbourhood’ has an iconic position in planning” (p. 472), shaping both planning theory and practice. Similarly, Sullivan and Taylor (Citation2007) comment that the idea of the neighbourhood “… has become increasingly powerful in urban policy and academic discourse” (p. 21). Underscored by Kallus and Law-Yone (Citation1997), they describe neighbourhoods as “comprehensive residential systems” which are “crucial to the design and planning of the urban environment” (p. 108).

For some researchers, neighbourhoods have “a discerned urban scale (more than a single house, less than an entire city), a specific function (housing and related services), and a defined structure (part of a system and a system by itself)” (Kallus & Law-Yone, Citation1997, p. 109). This spatial notion is extended by others to incorporate social constructs about how residents define their neighbourhoods. For example, in the work of Jenks and Dempsey (Citation2007) “‘neighbourhood’ is defined as both a district – a physical construct, describing the areas in which people live, and a community – a social construct, describing the people who live there” (p. 155). Similarly, Chaskin (Citation1997) sees neighbourhood socio-spatially as “the primary unit in which local ties reside and on which community identity and action is based” (Citation1997, p. 528). They are therefore complex experiential socio-spatial constructs, shaped by the people that inhabit them (Sullivan & Taylor, Citation2007, p. 21).

Kallus and Law-Yone (Citation1997) who trace the concept of neighbourhood to the nineteenth century, argue that “beyond the physical neighbourhood and its use as an urban unit (its size, structure, form, organization, specific with the city, and so on), lies always a theoretical hypothesis of the neighbourhood as an idea – a vision of an ideal neighbourhood” (Kallus & Law-Yone, Citation1997, p. 109). At its core, there is a connection in this idea of neighbourhood between the physical spaces and built form of an environment, and the emotional and physical wellbeing of residents and the resultant liveability they experience.

Kallus and Law-Yone (Citation1997) also consider the idea that neighbourhoods are both a product of resident perceptions and in turn shape how residents perceive or define themselves. There are several recent studies that consider neighbourhoods as a product of resident perceptions (Corrado, Corrado, & Santoro, Citation2013; De Vos, Van Acker, & Witlox, Citation2016; Hipp, Citation2010; Leenen, Citation2009; Permentier, Bolt, & van Ham, Citation2011; Saville-Smith, Citation2008; Sirgy & Cornwell, Citation2002). Here, neighbourhoods are defined not by their size or spatial borders, but by how residents perceive the ways in which their daily life needs and lifestyle expectations are being met by the socio-spatial construct of the neighbourhood. Most notably, neighbourhood satisfaction has emerged as a cornerstone of subjective neighbourhood research (Corrado et al., Citation2013; Grogan-Kaylor et al., Citation2006; Guest & Lee, Citation1983; Hipp, Citation2010; Howley, Scott, & Redmond, Citation2009; Oktay & Marans, Citation2010; Ott, Citation2009; Permentier et al., Citation2011; Yang, Citation2008).

Embedded within housing literature is the notion that local amenities have a role to play in influencing residents’ satisfaction, and the liveability they experience, from their neighbourhood environment (Allen, Citation2017; Grogan-Kaylor et al., Citation2006; Hipp, Citation2010). From a survey among Brisbane residents, Buys and Miller (Citation2012) found that neighbourhood satisfaction “was significantly associated with the position of the dwelling and its location with respect to neighbourhood facilities, the quality of outdoor air, reduced noise from emergency service vehicles, as well as satisfaction with the general condition (upkeep/tidiness) of the area and walks” (Buys & Miller, Citation2012, p. 330).

An offshoot of neighbourhood satisfaction is housing satisfaction (also known as dwelling or residential satisfaction) (Buys & Miller, Citation2012; Hourihan, Citation1984; Lee & Park, Citation2010), and to a lesser extent neighbourhood dissatisfaction has also been ratified in the literature (De Vos et al., Citation2016). Satisfaction, at varying scales in the built environment, connects the literature on neighbourhoods to the literature on perceived liveability and is at this nexus of this paper.

3. Methodology

This paper reports on findings from a survey of residents living in higher density housing in Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city with a population of 1.6 million (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2017). The Auckland Plan is the current strategic policy aimed at achieving intensification (Auckland Council, Citation2012). This is given effect though the Unitary Plan that sets an aim for a “quality compact urban form with a clear limit” (Auckland Council, Citation2017). As is the case with similar approaches taken in the larger Australian cities, Auckland is challenged to accommodate growth by transforming and intensifying its current neighbourhoods in such a way that intensification must go hand in hand with the perceived liveability experienced by residents (Allen, Citation2017; Haarhoff et al., Citation2016; Thomas, Walton, & Lamb, Citation2010).

The guiding methodological approach behind this paper is Constructivist Grounded Theory (Allen & Davey, Citation2017; Charmaz, Citation2006), a rigorous methodology which supports the study of complex urban phenomena and provides a responsive way to consider important contemporary urban growth management issues. As formulated, this approach enables the development of evidence-based theory from inductive analysis.

Four case study neighbourhoods were selected, all among the 102 designated centres for intensification in Auckland: Takapuna, Kingsland, Botany, and Te Atatu Peninsula, located in Figure .

They were selected because each presented a different context to provide comparisons, and key characteristics are set out in Table .

Table 1. Key characteristics of the case study areas

The case study neighbourhoods range from 3.6 to 18.9 kilometres from the Auckland CBD, to the north, west, and south-east. Two of the locations were chosen because they are in close proximity to the Auckland CBD, with one (Takapuna) designated as a metropolitan centre (Takapuna). Two are located in outer suburbs/city fringe. The varying locational characteristics were seen to be important in determining if distance from the CBD affected how residents thought about their neighbourhoods and the amenities they used and valued.

Within these case study neighbourhoods, residents in twelve multi-unit developments were interviewed. Each development had a density greater than 35 units/hectare, was at least three years old, and in a location providing access to local amenities (i.e. in a town centre or established neighbourhood). This meant a mix of housing typologies from 3–5 storey apartment complexes, to attached townhouses and units (see examples in Figures ). This range is in line with the diversity of higher density typologies that are increasing in prevalence in Auckland.

Interviewees were recruited over a six-month period through mailbox letter-drops. In total, fifty-seven residents responded from a total of 1,012 mailbox letter-drops. The process of identifying potential case study developments and doing mailbox letter-drops continued until no new information was discovered and data saturation was reached (Jones & Alony, Citation2011, p. 106).

As a qualitative study, hour-long structured interviews were guided by topics covering household structure, dwelling tenure, current employment and travel habits; as well as housing histories and aspirations, using a process and method approved by The University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee. Interviewees were met in a location of their choosing and were asked about the neighbourhood amenities they use, how often, their accessibility, and how they valued them. How residents perceived liveability, their neighbourhoods, and the concepts of urban intensification and density were also explored. Data was coded according to a three-tiered constructivist grounded theory substantive coding process, including open, selective, and theoretical coding.

In total 36 females and 21 males responded to the mailbox letter drops, ranging in age from 23 and 87 (average age was 44). Of the 57 interviewees, 26 were owner-occupiers and 31 were renters. The average length of dwelling tenure was three years, with the shortest being one month and the longest thirteen years. Predominantly, renters had been living at their current address for less than two years that reduced the overall average length of tenure. Seven interviewees lived alone, 25 were couples, six lived with flatmates, and two lived with extended family members. Seventeen had at least one child living at home, and of these, ten had children under seven, with only three having two or more children living at home.

Thirty-six of the interviewees were born in New Zealand and nearly half of these had also spent time living overseas where they were exposed to a range of different lifestyles and housing options. Of the 21 born overseas, only 11 were from countries where English was not their first language. Countries of origin included The United States of America, Australia, Scotland, England, China, Korea, Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, India, Portugal, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Serbia, Jordan, Mozambique, and South Africa. Nineteen of the interviewees had experienced living outside Auckland including Christchurch and Wellington, rural Otago, Napier, Gisborne, Palmerston North, Tauranga, Rotorua, and Tairua. Despite geographic, demographic, and socio-economic variations between the interviewees, clear patterns emerged about their perceptions of neighbourhood and the role of neighbourhood amenities in delivering liveability.

4. The idea of neighbourhood

The “idea” of neighbourhood builds on Kallus and Law-Yone’s (Citation1997) notion of the neighbourhood as an idea perceived by residents. Findings are therefore focused on how neighbourhoods were conceptualised by interviewees, and the patterns that emerged when they were asked to both define and describe them. Building on the interview method of Marans and Stimson (Citation2011, pp. 7, 91) this research also considers the multifaceted nature of neighbourhood satisfaction by asking interviewees how they view their neighbourhoods in terms of their likes and dislikes, and how they thought their neighbourhoods could be improved.

When interviewees living in the same case study development were asked to define their neighbourhood, the outcome was often a different geographical area to that defined by the next interviewee. Most interviewees across all four case studies described their neighbourhoods as both their immediate suburb, but extended to include two to four adjoining suburbs. For example, in Takapuna this included the adjoining suburb of Milford and other suburbs in the area with which interviewees were familiar. In Kingsland, this included the neighbouring areas of Eden Terrace, St Lukes, and Sandringham (within a 10–15 min walk). Other descriptions included distance related accounts such as “two kilometres from the apartment” and “within a thirty-minute walk from my apartment”. It was concluded that while the “core” of each interviewee’s neighbourhood was predominantly focussed around their local walkable environment, the “edges” were so diverse that they were seldom comparable to one another. What emerged was the idea of an agreed “neighbourhood core” but with disparate “neighbourhood edges”, concepts similar to the neighbourhood mapping analysis by Minnery et al. (Citation2009).

Place attachment was a key factor that affected how interviewees conceptualised their neighbourhoods, both socially and spatially. For example, one interviewee described their neighbourhood as mostly their immediate suburb. However, they also felt a connection to another Auckland suburb that was a twenty-minute drive away, due to time they spent there visiting family. They considered that both areas made up their conceptualisation of neighbourhood. Another interviewee who lived in the same development also described their neighbourhood as mostly their immediate suburb. However, they also considered the suburb where they worked to be part of their neighbourhood, since they used both areas to access key daily life amenities such as supermarkets, cafés, green spaces and medical facilities. Others spoke about identifying their neighbourhood as both the area in which they currently lived, as well as the suburb that they had lived previously and/or grown up in, because of the familiarity they still had with these areas. Familiarity was synonymous with place attachment and was in turn a core determinant in how interviewees considered their personal idea of neighbourhood.

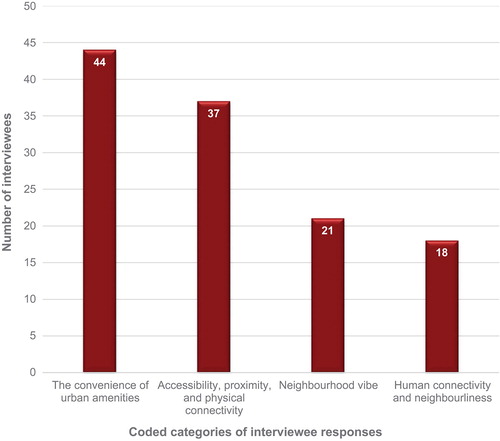

In addition, and in line with the findings of Lee and Campbell (Citation1997), and Jenks and Dempsey (Citation2007), it was found that neighbourhood satisfaction was more multifaceted than a simple binary answer. Identifying their likes and dislikes helped interviewees to think more deeply about how their neighbourhood affected their liveability, and how their acceptance of higher density living might also be affected by their current environment. Responses about what interviewees liked in their neighbourhoods were coded into four categories, shown in Figure . The convenience delivered by local amenities was the most frequently cited reason across all the interviews as to why interviewees liked their neighbourhoods.

Neighbourhood dislikes were less important to interviewees than their neighbourhood likes when it came to how they conceptualised their neighbourhood. Out of fifty-seven interviewees, seventeen were not able to identify any dislikes about their neighbourhood when asked. Of the remaining forty interviewees who could identify neighbourhood dislikes, nineteen cited environmental factors, particularly noise. Neighbourhood dislikes were expressed even though residents felt an overall satisfaction with their neighbourhoods. The process of identifying neighbourhood likes and dislikes engaged interviewees in thinking about, and commenting on, ways in which they would want to subsequently see their neighbourhood improved. Additional neighbourhood amenities were cited by 24 interviewees as a way they would like to see their neighbourhood improved, 17 wanted to see additional or improved infrastructure and 21 were not sure how their neighbourhood could be improved. Together, the neighbourhood likes, dislikes, and improvements data built a picture of neighbourhood satisfaction and how neighbourhoods are conceptualised.

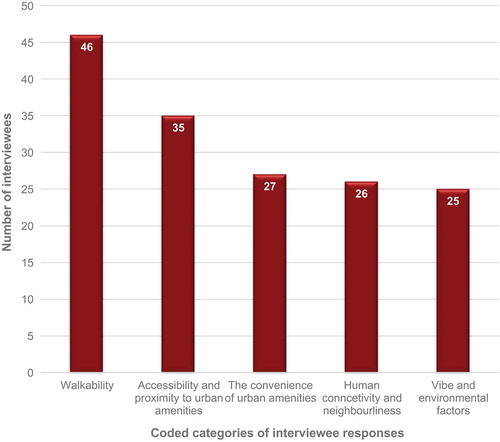

Interviewees were also asked to comment on how they perceived the relationship between what defined their neighbourhood satisfaction and the liveability they felt they derived from their neighbourhood. Five core categories of findings were coded, and shown in Figure .

Walkability was the concept most frequently linked by interviewees to their neighbourhood satisfaction and liveability experiences. It was also the category that overlapped the most with other aspects. For example, the thoughts expressed by interviewees about walkability also covered notions of accessibility to neighbourhood amenities, employment locations, their health and wellbeing, and their sense of pleasure at living in their neighbourhood.

The roles of neighbourhood amenities were also related by interviewees to neighbourhood satisfaction and liveability when they spoke about ease of accessibility. Thirty-five interviewees articulated this relationship, and convenience and choice were articulated by twenty-seven interviewees at various times throughout the interview process. One interviewee commented that neighbourhood amenities “can make things more difficult, or easier, depending on where you live” and another noticed that “good amenities, good quality amenities, would affect how and where you go, when”.

However, perceptions of what proximity and accessibility meant differed among interviewees. For example, one interviewee said that their liveability was improved by the easy accessibility and proximity of a local swimming pool. Another interviewee commented about not using the same pool because they perceived it to be too far to walk and inconvenient to access. The difference was that one interviewee was accustomed to travelling for twenty minutes from their previous dwelling to use a swimming pool, while the other previously had a pool within their apartment complex. Perceptions of proximity were also related to familiarity. For example, the concept of walkability varied: if people knew the route very well, and considered it to be within their neighbourhood, then they were likely to think that an amenity was more easily accessible. Both accessibility and proximity are relative terms and must be considered as factors affecting the perceptions interviewees have of their neighbourhoods.

Ultimately, the research found that there was an underlying importance of walkability in understanding how neighbourhoods are defined and perceived by residents, even with the varied definitions applied to it by interviewees. This is in line with the findings of Mehta (Citation2008) and Sandalack et al. (Citation2013). It was also possible to determine that the desire for convenience, that has become part of modern lifestyles, is a significant factor that affects the neighbourhood satisfaction experienced by residents. Allen (Citation2016) also identifies that “there is a cyclical relationship between accepting urban lifestyles, valuing convenience, and convenience provided by neighbourhood amenities” (p. 135). Considering how neighbourhoods are conceptualised by residents brings together both socio-spatial definitions of neighbourhood, but also multidimensional, and at times very personal, understandings of neighbourhood satisfaction and perceived liveability. It is at the intersection of these findings that discussions on future neighbourhoods can begin.

5. The role of neighbourhood amenities in delivering liveability

Emerging from the previous section is that neighbourhood amenities have a role to play in framing the idea of neighbourhood, and in the satisfaction expressed by residents. This section expands on the role neighbourhood amenities play in contributing to the liveability experienced by residents. Initially, interviewees were questioned about how they defined the term neighbourhood amenities to establish a baseline for assessing their role in delivering liveability. Most interviewees thought amenities were all the services and infrastructure they used in their daily lives. Generally, they found it easier to list examples, rather than define the concept. One interviewee listed, “public transportation, cultural locations like theatres, cinemas, concert halls … educational establishments, libraries, universities, schools, hospitals, entertainment, pubs, bars”. Like this individual, most interviewees considered neighbourhood amenities to include natural, public and commercial amenities that contribute in varying degrees to their daily life needs and their neighbourhood satisfaction. They thought seamlessly about the spatial relationship between their dwellings and the amenities they wanted to live near. Allen (Citation2016) describes how this understanding contrasts with much planning policy and strategy, where amenities are categorised in to silos such as natural, entertainment, or public amenities. These are often attributed to different departments, such as a parks and recreation department that manages open space networks. In total, nine groupings of neighbourhood amenities were identified from interviewee descriptions, and these are shown in Figure , although they must be understood as parts of a whole.

Figure 8. Categories of neighbourhood amenities (Allen, Citation2017)

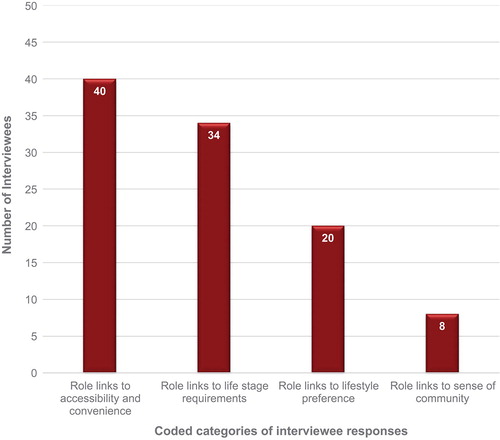

During the interviews, interviewees were asked about how they thought their neighbourhood affected their liveability, and typically continued to articulate their views throughout the remainder of the interview. These views were synthesised in the data coding, and Figure shows responses organised into four categories.

Figure 9. The perceived role neighbourhood amenities played in delivering liveability for interviewees

Most interviewees saw the role of neighbourhood amenities as multifaceted and posited a variety of overlapping responses in terms of the relationship they saw between neighbourhood amenities and liveability. With regards to liveability, 40 of the 57 interviewees saw the role of neighbourhood amenities as linked to the convenience and accessibility of the goods and services they used and valued in their daily lives. One spoke about appreciating that their gym was in close proximity to a “great local café” where they could meet friends before or after their gym session. Another spoke of going to the local pub with their sports team following a practice or game. Several parents spoke about getting a treat for themselves, such as a coffee, while taking their children to the park or to a swimming lesson.

Also shown in Figure , the role of neighbourhood amenities was linked by thirty-four interviewees to the liveability they desired at different life stages. For example, one interviewee suggested elderly people might want a quiet café during the day or for afternoon tea, whereas young people might want to get a coffee early in the morning on their way to work and might also want somewhere where they could stop in for a drink after work.

It followed that interviewees saw neighbourhood amenities as having a role in meeting lifestyle preferences. One interviewee had chosen to live in their current home due to lifestyle preferences, because, “It’s close to everything … places we like to go out to, where all our friends live”. Interviewees most frequently cited food-related amenities as a form of entertainment, which added to their neighbourhood satisfaction. Others linked sports and recreation amenities to entertainment: using local parks, beaches, and reserves for leisure activities, going to gym classes or watching sports at recreation amenities. Five interviewees spoke about events-based entertainment. For example, one interviewee commented that for entertainment they went to events, such as the annual Chinese lantern festival or the weekly market. Eight interviewees linked the role of neighbourhood amenities to creating a sense of community and giving residents options that can help them engage with and feel connected to the neighbourhoods in which they live. Interviewees spoke about gaining a sense of community by participating in sporting activities, meeting up with friends, or meeting new friends at these amenities.

Although many interviewees referred to their use of online shopping and services, the human interactions made possible in the physical spaces created by neighbourhood amenities remained of primary importance for all of the interviewees. Human interactions positively affected their overall neighbourhood satisfaction. Neighbourhood amenities add to the social complexity and cohesiveness of neighbourhoods.

Furthermore, food-related amenities were considered most important in delivering liveability, with supermarkets specifically mentioned the most frequently. Recreation amenities and public spaces, particularly parks, were also favoured. Most interviewees also considered the best way to improve a neighbourhood in preparation for intensification was to add additional amenities to ensure liveability was maintained. Natural amenities, such as regional parks, featured most strongly when interviewees were considering which neighbourhood amenities were the most important to enhance or develop in this case.

It was also found that the liveability experienced by residents is likely to be enhanced when certain complementary neighbourhood amenities are spatially grouped close to one another. Residents valued highly the ability to use a wide range of amenities sequentially or concurrently, without needing to travel very far. The idea raised by this research is therefore that the strategic provision of additional amenities in a neighbourhood corresponds to the increased acceptance of higher density living without adversely affecting liveability. Examples mentioned included the opportunity for a parent to drop one child at day-care, grab a coffee or takeaway breakfast, and then take the other child and/or their dog to explore a local park, all in walking distance from home; and the opportunity to sit with friends in a park after a game of indoor soccer at the gym, with picnic lunches that had been bought nearby.

6. Discussion

The findings support a contention that to understand how future neighbourhoods need evolve to maintain or enhance liveability outcomes, we must understand how residents define, perceive, and use their neighbourhoods. This is of greater importance at higher densities, and includes understanding how residents define, perceive, and use the neighbourhood amenities around them.

Asking interviewees to first define their neighbourhoods, before asking about their neighbourhood satisfaction, was shown in this research to be important because otherwise it is unclear whether they are talking about comparable geographic areas and urban scales or completely diverse ones. In line with the research of Minnery et al. (Citation2009), interviewees in this study also seemed “to have a far more nuanced view of neighbourhood boundaries than do planners and other policy-makers” (p. 491). The findings also align with the work of Coulton, Korbin, Chan, and Su (Citation2001) who assert that “researchers should not assume the similarity of resident- and census-defined neighbourhoods” (p. 381). This proved a useful observation in the research, because interviewees’ ideas of neighbourhoods rarely aligned with the official census definitions. Similarly, Lee and Campbell (Citation1997) asked: “Does the word ‘neighbourhood’ serve as a common frame of reference across individuals and settings, or is it largely an idiosyncratic concept?” (p. 926). Despite overlaps in the core areas (Minnery et al., Citation2009), interviewees in this study defined as their neighbourhoods in idiosyncratic ways when conceptualising the idea of neighbourhood.

The findings strongly align with Chaskin’s (Citation1997) “concept of neighbourhood” as a network, where “an individual’s neighbour networks and neighbouring behaviour may vary by gender, age, ethnicity, family circumstances, and socioeconomic status. Such networks are also affected by the neighbourhood context in which they develop” (p. 537). This research took that notion a step further and argues that for individual understandings of neighbourhood satisfaction to be of value in improving liveability outcomes, networks of neighbourhood amenities across a city must be considered throughout local framework planning. In line with Chaskin (Citation1997), the findings concur with the view that:

There is no universal way of delineating the neighbourhood as a unit. Rather, neighbourhoods must be identified and defined heuristically, guided by specific programmatic aims, informed by a theoretical understanding of neighbourhood and a recognition of its complications on the ground, and based on a particular understanding of the meaning and use of neighbourhood (as defined by residents, local organizations, government officials, and actors in the private sector) in the particular context in which a program or intervention is to be based (p. 541).

Equally Chaskin (Citation1997), and Durose and Richardson (Citation2009), consider that neighbourhood is also a “salient” idea because what people mean by neighbourhood is different for different groups of citizens, who have different relationships to neighbourhoods (Durose & Richardson, Citation2009, p. 40). In turn, they add that “it is more appropriate to understand neighbourhoods not as simple spatial or geographical units, but as socially constructed realities” (Durose & Richardson, Citation2009, p. 43). They caution, in alignment with the findings of this research, that “the dominance of “economic” and “political” rationales means that neighbourhoods are defined and implemented at too large a scale, and based on political control rather than people’s day-to-day experiences” (p. 43).

Jenks and Dempsey (Citation2007) rationalise a threefold perception of neighbourhood by residents: “my neighbourhood”, “our neighbourhood”, and “the neighbourhood” (p. 160). They consider that their rationalisation calls in to question the traditional 400 metre circle in which it is argued “key services, including primary school, open space, a food shop and pub, should be accessible” from residents homes (Jenks & Dempsey, Citation2007, p. 162). Because “residents may consider their neighbourhood to include services and facilities that are further away than the catchment areas proposed in theory and practice” (Citation2007, p. 162) Jenks and Dempsey argue that “such prescribed distances may not therefore correspond to boundaries identified by residents, particularly in largely residential neighbourhoods” (Citation2007, p. 162). This alludes to the complex understandings of accessibility and proximity which are identified by this study as areas which would benefit from further detailed research. Research which builds on the findings presented here, and the threefold perception of neighbourhood defined by Jenks and Dempsey (Citation2007), would no doubt also benefit from considering the connections and disconnections between perceived and prescribed walking distances.

Furthermore, in this research, both neighbourhood satisfaction and liveability were found to be closely aligned to the seamless integration of a mix of amenities. The perceived proximity and accessibility of neighbourhood amenities to an interviewee’s home was considered to deliver lifestyle convenience and in turn neighbourhood satisfaction. As a result, the strategic integration and placement of amenities in a neighbourhood is understood to be integral to also delivering liveability. This is in line with the research of Sullivan and Taylor (Citation2007) who found that neighbourhoods are valuable to citizens if “key features provide positive comfort and support” (p. 25) because “individuals’ relationship with and experience of the neighbourhood is contingent on a variety of factors” (p. 25).

Sullivan and Taylor (Citation2007) go on to argue that “the subjective, even dialectical, nature of the neighbourhood experience poses an important dilemma for policy makers who seek to determine what are ‘successful’ and ‘unsuccessful’ neighbourhoods” (p. 27). This paper cautions about the realism of current intensification policies and strategies in their desire to deliver liveability for residents. The idea that a network of neighbourhood amenities plays a role in providing liveability outcomes is often inferred, but not explored, in both policy and strategy documents, and intensification literature. Hansen and Winther (Citation2010) suggest that while “neighbourhood amenities as growth drivers have been given much attention in urban and regional studies” (p. 1), internationally, an exploration of the meaning and perceived value of neighbourhood amenities for, and by, residents has seldom followed. This is in part due to a disconnect between research which considers emergent forms of urbanism and the practical “real world” delivery of complex fine-grain neighbourhoods offering a variety of neighbourhood amenities and housing typologies (Allen, Citation2016).

Further research focussed on how residents use and value neighbourhood amenities seamlessly across their neighbourhood must be undertaken if we are to develop a more nuanced understanding of the liveability outcomes that could be experienced in future neighbourhoods. This requires neighbourhood amenities to be considered as a single category, as they relate to liveability, irrespective of whether they are public sector amenities provided by councils (such as parks, public squares and recreational facilities) or market driven private sector amenities (such as cafés, restaurants, retail and other goods or services). It also points to the realisation that viewing neighbourhoods as having a purely residential function does not best serve the liveability expectations of residents.

A better understanding of how residents are making trade-offs between suburban and urban lifestyle options is critical to understanding the relationship between neighbourhood amenities, perceived liveability, and the development of future neighbourhoods. The first step in the process of guiding existing neighbourhoods towards the neighbourhoods we need in the future, is a prioritisation of the strategic integration of neighbourhood amenities in line with a greater variety of higher density housing typologies. Beattie and Haarhoff (Citation2011, p. 10), for example, comment on the increasing interest in urban-style living by observing that reforming existing neighbourhoods “is a serious area of research and practice yet to be more fully explored”. Similarly, Rowland (Citation2010, p. 32) hypothesises that future neighbourhoods will be lively centres “with a range of commercial, retail and cultural activities with small squares and convivial meeting places in which these activities can take place”. Schmitz (Citation2003, p. 13) considers that the best future neighbourhoods will be “places where people can build their lives, where they can make social connections, educate their children, obtain the goods and services that meet their daily needs, and even earn their livelihoods”.

7. Conclusion

Our findings underscore the strong alignment between neighbourhood satisfaction and liveability, they were also found to be closely aligned to the seamless integration of a mix of amenities within and beyond neighbourhoods. Indeed, evaluations of housing intensification over the past decade clearly demonstrate housing satisfaction and liveability are the result of both the quality of the housing, and the amenity of the neighbourhood in which it is located. This has been codified in urban planning through the promotion of urban intensification as transit-oriented development (TOD) that concentrates development at, and around, existing transit and retail centres. Moreover, also linked to the idea of successful neighbourhoods is “walkability”, achieved by locating higher density housing within walkable catchments (so-called “ped-sheds”), typically between 400–800 metres of an urban centre.

Our findings, along with others, reinforce the significance of public and retail amenities enhancing neighbourhood satisfaction and liveability, reinforced in our findings by a strong association between walkability and liveability. However, our findings challenge the assumption that neighbourhoods can be reduced to physical entities such as TOD catchments, that do not reflect the complexities of how residents use their neighbourhoods daily. As reported, while there is a “core” set of amenities that most residents will share, resident engagement with, and movement to, the wider urban environment is very varied and driven by personal needs. Neighbourhoods in this sense are far more fluid and variable than those defined by TOD walking catchments. Our findings also suggest that residents think seamlessly about the spatial relationships between their dwellings and the amenities of the neighbourhood. The nine overlapping categories of neighbourhood amenities found in our research contrast with the more typical distinction between public and private sector, or reductionist “mixed use” land use zoning.

These conclusions should be of interest to urban planners promoting higher density development – that a nuanced understanding of how neighbourhoods function and are defined requires more flexible thinking. Also of importance in this regard is the underscoring of the need for development authorities to ensure sufficient investment in the public spaces that contribute towards to a resident’s sense of enhanced liveability. Similarly, to create appropriate and flexible arrangements to encourage market investment in a range of commercial services to complement public facilities. Moreover, despite our finding supporting the idea of a core set of amenities that define a neighbourhood, movement is not constrained within a walkable catchment of this area. Schooling, bulk shopping, visiting friends and places of work lie outside this neighbour precincts for most residents, requiring a more nuanced understanding of how best to support movement demands while aiming to reduce car dependency. Shared forms of transport such as “Uber”, offer one such possible solution. Further targeted research to consider the level of density that is needed to provide a diverse range of “core” urban amenities for a in a neighbourhood to be walkable, and serve diverse demographics, would be beneficial.

While supported the necessity for urban intensification in countries such as New Zealand and Australia that historically have been dominated by low density suburban sprawl, it is essential for urban planning and urban design to embrace and understanding of how neighbourhoods residents through their lived experiencers shape the idea of neighbourhoods. The neighbourhood amenities residents use most frequently are the ones that most directly contribute to the satisfaction they derive from their neighbourhoods, yet all neighbourhood amenities they use and value contribute to the liveability they derive from living in their city. It is within this paradigm that future neighbourhoods must also be considered, if their successful development is to embody liveable outcomes.

Funding

This article was supported by funding from the National Science Challenge 11—Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities: Ko ngā wā kāinga hei whakamahorahora.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the residents who gave of their time to be interviewed as part of this research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Natalie Allen

Dr Natalie Allen is Director of The Urban Advisory Ltd, an urban strategy consultancy based in New Zealand. With a background in architecture and a PhD in urban design, Natalie values thinking across all scales of design. Natalie specialises in neighbourhood development advice and medium density housing issues. Her research is focussed on the relationships between delivering urban intensification and maintaining or enhancing the liveability experienced by residents. Professor of Architecture Errol Haarhoff and Dr Lee Beattie (Director: Urban Planning) are both in the School of Architecture and Planning, at The University of Auckland. They have been studying urban growth management in New World cities for the past ten years. This work involves comparative analyses of Vancouver, Portland, Auckland, Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne and Perth. Professor Haarhoff is now leading one of six strategic research areas in a National Science Challenge: Building Better Homes, Towns and Cities: Shaping Place: Future Neighbourhoods.

References

- Allen, N. (2016). Quality of urban life and intensification: Understanding housing choices, trade-offs, and the role of urban amenities (Doctor of Philosophy). The University of Auckland, Auckland.

- Allen, N. (2017). Delivering liveable neighbourhoods: What does this mean to residents? Paper presented at the 10th Making Cities Liveable Conference Brisbane.

- Allen, N. , & Davey, M. (2017). The value of constructivist grounded theory for built environment researchers. Journal of Planning Education and Research , 1 (11), doi:10.1177/0739456X17695195

- Auckland Council . (2012). Auckland plan . Auckland: Author.

- Auckland Council . (2017). Unitary plan . Auckland: Author.

- Australian Government . (2012). State of Australian cities . Canberra: Department of Infrastructure and Transport, Major Cities Unit.

- Beattie, L. , & Haarhoff, E. (2011). Questions about ‘smart growth:’ A critical appraisal of urban growth strategies in Australasian and North American cities . Paper presented at the New Urbanism and Smart Transport Conference, Perth.

- Bryson, K. (2017). The New Zealand housing preferences survey: Attitudes towards medium-density housing . Wellington: BRANZ.

- Buxton, M. , & Tieman, G. (2004). Urban consolidation in Melbourne 1988–2003: The policy and practice . Melbourne: RMIT Publishing.

- Buys, L. , & Miller, E. (2012). Residential satisfaction in inner urban higher density Brisbane, Australia: Role of dwelling design, neighbourhood and neighbours. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management , 55 (3), 319–338.10.1080/09640568.2011.597592

- CABRE . (2017). Auckland marketflash – The apartment cycle in numbers . Retrieved from https://www.cbre.com/

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

- Chaskin, R. (1997). Perspectives on neighborhood and community: A review of the literature. Social Service Review , 71 (4), 521–547.10.1086/604277

- CHRANZ . (2011). Improving the design, quality and affordability of residential intensification in New Zealand . Auckland: CityScope Consultants/Centre for Housing Research Atearoa New Zealand. Retrieved November 30, 2015, from http://www.chranz.co.nz/pdfs/improving-the-design-quality-affordability-residential-intensification.pdf

- Clark, T. , Lloyd, R. , Wong, K. , & Jain, P. (2002). Amenities drive urban growth. Journal of Urban Affairs , 24 (5), 493–515.10.1111/1467-9906.00134

- Corrado, G. , Corrado, L. , & Santoro, E. (2013). On the individual and social determinants of neighbourhood satisfaction and attachment. Regional studies: Journal of the Regional Studies Association , 47 , 544–562.10.1080/00343404.2011.587797

- Coulton, C. , Korbin, J. , Chan, T. , & Su, M. (2001). Mapping residents’ perceptions of neighborhood boundaries: A methodological note. American Journal of Community Psychology , 29 (2), 371–383.10.1023/A:1010303419034

- De Vos, J. , Van Acker, V. , & Witlox, F. (2016). Urban sprawl: Neighbourhood dissatisfaction and urban preferences. Some evidence from Flanders. Urban Geography , 37 (6), 839–862.10.1080/02723638.2015.1118955

- Durose, C. , & Richardson, L. (2009). ‘Neighbourhood’: A site for policy action, governance … and empowerment? In C. Durose , S. Greasley , & L. Richardson (Eds.), Changing local governance, changing citizens (pp. 31–52). University of Bristol: Policy Press.10.1332/policypress/9781847422170.001.0001

- Fincher, R. , & Gooder, H. (2007). At home with diversity in medium-density housing. Housing, Theory and Society , 24 (3), 166–182.10.1080/14036090701374530

- Foord, J. (2010). Mixed-use trade-offs: How to live and work in a ‘compact city’ neighbourhood. Built Environment , 36 (1), 47–62.10.2148/benv.36.1.47

- Grogan-Kaylor, A. , Woolley, M. , Mowbray, C. , Reischl, T. , Guster, M. , Karb, R. , & Alaimo, K. (2006). Predictors of neighborhood satisfaction. Journal of Community Practice , 14 (4), 27–50.10.1300/J125v14n04_03

- Guest, A. , & Lee, B. (1983). Determinants of neighborhood satisfaction: A metropolitan-level analysis. The Sociological Quarterly , 24 (2), 287–303. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1983.tb00703.x

- Haarhoff, E. , Beattie, L. , Dixon, J. , Dupuis, A. , Lysnar, P. , & Murphy, L. (2012). Future intensive: Insights for Auckland’s housing . Auckland: The University of Auckland; Transforming Cities.

- Haarhoff, E. , Beattie, L. , & Dupuis, A. (2016). Does higher density housing enhance liveability? Case studies of housing intensification in Auckland. Cogent Social Sciences , 2 , 1243289.

- Hansen, H. , & Winther, L. (2010). Amenities and urban and regional development: Critique of a new growth paradigm . Paper presented at the Regional Studies Association Annual International Conference, Pécs, Hungary.

- Hipp, J. (2010). What is the ‘neighbourhood’ in neighbourhood satisfaction? Comparing the effects of structural characteristics measured at the micro-neighbourhood and tract levels. Urban Studies , 47 , 2517–2536.10.1177/0042098009359950

- Hourihan, K. (1984). Residential satisfaction, neighbourhood attributes, and personal characteristics: An exploratory path analysis in Cork, Ireland . Environment and Planning A.

- Howley, P. , Scott, M. , & Redmond, D. (2009). Sustainability versus liveability: An investigation of neighbourhood satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management , 52 (6), 847–864.10.1080/09640560903083798

- Jenks, M. , & Dempsey, N. (2007). Defining the neighbourhood: Challenges for empirical research. Town Planning Review , 78 (2), 152–177.

- Jones, M. , & Alony, I. (2011). Guiding the use of grounded theory in doctoral studies – An example from the Australian film industry. International Journal of Doctoral Studies , 6 , 95–114.10.28945/1429

- Kallus, R. , & Law-Yone, H. (1997). Neighbourhood - The metamorphosis of an Idea. Journal of Architecture and Planning Research , 14 (2), 107–125.

- Lee, B. , & Campbell, K. (1997). Common ground? Urban neighborhoods as survey respondents see them. Social Science Quarterly , 78 (4), 922–936.

- Lee, E. , & Park, N. (2010). Housing satisfaction and quality of life among temporary residents in the United States. Housing and Society , 37 (1), 43–67.10.1080/08882746.2010.11430580

- Leenen, J. P. M. (2009). Perceived liveability in Dutch neighbourhoods: The influence of individual characteristics and characteristics of the residential area on Dutch citizen’s neighbourhood satisfaction . Universiteit van Tilburg. Sociologie.

- Marans, R. , & Stimson, R. (Eds.). (2011). Investigating quality of urban life: Theory, methods, and empirical research . Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands.

- Mehta, V. (2008). Walkable streets: Pedestrian behavior, perceptions and attitudes. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability , 1 (3), 217–245.

- Minnery, J. , Knight, J. , Byrne, J. , & Spencer, J. (2009). Bounding neighbourhoods: How do residents do it? Planning Practice & Research Planning Practice & Research , 24 (4), 471–493.10.1080/02697450903327170

- Oktay, D. , & Marans, R. W. (2010). Overall quality of urban life and neighborhood satisfaction: A household survey in the walled city of famagusta. Open House International: Housing and the Built Environment: Theories, Tools And Practice , 35 (3), 27–36.

- Ott, C. (2009). Does housing make a community livable? Housing consumption and neighborhood satisfaction in metropolitan areas (Master of Public Policy). Georgetown University, Washington, DC.

- Permentier, M. , Bolt, G. , & van Ham, M. (2011). Determinants of neighbourhood satisfaction and perception of neighbourhood reputation. Urban Studies , 48 , 977–996.10.1177/0042098010367860

- Randolph, B. (2006). Delivering the compact city in Australia: Current trends and future implications ( 6).

- Rowland, J. (2010). The 21st century suburb. Urban Design International , 115 , 31–33.

- Sandalack, B. , Alaniz Uribe, F. , Eshghzadeh Zanjani, A. , Shiell, A. , McCormack, G. , & Doyle-Baker, P. (2013). Neighbourhood type and walkshed size. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability , 6 (3), 236–255.

- Saville-Smith, K. (2009). A national survey of neighbourhood experiences and characteristics: Opportunities for data use . Auckland: Beacon Pathway Limited. Retrieved from http://www.beaconpathway.co.nz/images/uploads/Public_Report_NH3102(4)_National_Neighbourhoods_Data.pdf

- Schmitz, A. (2003). New shape of suburbia: Trends in residential development . Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute.

- Sirgy, J. , & Cornwell, T. (2002). How neighbourhood features affect quality of life. Social Indicators Research , 59 , 79–114.10.1023/A:1016021108513

- Statistics New Zealand . (2017). Statistics New Zealand website . Retrieved from http://www.stats.govt.nz/

- Sullivan, H. , & Taylor, M. (2007). Theories of ‘neighbourhood’ in urban policy. In I. Smith , E. Lepine , & M. Taylor (Eds.), Disadvantaged by where you live?: Neighbourhood governance in contemporary urban policy (pp. 21–42). University of Bristol: Policy Press.

- Thomas, J. , Walton, D. , & Lamb, S. (2010). The influence of simulated home and neighbourhood densification on perceived liveability. Social Indicators Research , 104 (2), 253–269.

- Yang, Y. (2008). A tale of two cities: Physical form and neighborhood satisfaction in metropolitan Portland and Charlotte. Journal of the American Planning Association , 74 (3), 307–323.10.1080/01944360802215546

- Yeoman, R. , & Akehurst, G. (2015). The housing we’d choose: A study of housing preferences, choices and trade-offs in Auckland (Auckland Council technical report, TR2015/016). Prepared by Market Economics Limited for Auckland Council. Auckland: Market Economics Limited.