Abstract

Stimulated by a disjuncture between the expectations and the experiences of conducting research on disability in Zambia, we reflexively reviewed our own research practice to find that it was premised upon an unconscious assumption about the value of productivity. This reflexive finding led us to reflect more deeply about the concept of productivity. From our own observations as health professionals and researchers in the global North complemented by literature, we described a hegemonic conception of productivity that we see to be represented. Through a more conscious articulation of our own approach to research and the responses that we observed from research participants with disabilities in Zambia, we articulated two alternative conceptions of productivity. We propose that the alternative conceptions of productivity are useful to inform more robust disability research in the global South. More generally, these alternative conceptions can be used as resistance to a narrowly conceived notion of productivity.

Public Interest Statement

In this article, we propose some different ways to think about ‘productivity.’ Despite often talking about productivity, we do not see many people who think carefully about what productivity means or why it is so important. We worked on a participatory research project with persons with disabilities in Western Zambia. In looking back, we realized that we had approached the project with the expectation that the research participants would be “productive.”

By thinking more carefully about our experience, identified a few possible meanings of productivity. In identifying these different meanings, we were able to better appreciate our motivations in this research, the ways that research participants interacted with us, and how these might be different from popular understandings of productivity. We find that it can be useful to think more carefully about productivity and the ways that it is valued; this thinking could help us better understand ourselves and others.

1. Introduction

Productivity is a valued quality in numerous fields, either as a disciplinary concept of interest or more generally as a behaviour. Economics might be the prime example of productivity as a specific concept of interest. Contemporary economics is dominated by the notion that prosperity consists of growth to support consumption (Foster, Citation2016); increasing productivity enables growth and consumption for prosperity. Academia is a field in which productivity is seen as a valued behaviour, in which producing is associated with quality (Davies & Bansel, Citation2010). In both of these fields, much thought is given to productivity: how can it be measured and how can it be increased? By contrast, relatively little thought is given to the more fundamental questions of what is it or why is it so valued? In essence, productivity is a concept that is socially ubiquitous in many settings, yet it remains under-theorized.

In this paper, we contribute to theory on productivity by presenting two alternative conceptions of productivity that we identified through reflexive analysis of a research project on disability in Western Zambia (Cleaver, Magalhães, Bond, Polatajko, & Nixon, Citation2016). These understandings of productivity are alternatives to the ways in which we typically hear productivity discussed and see it performed. In presenting these alternatives, we are challenging what we see to be a hegemonic conception of valued ways of being and doing.

Further, we present what we see to be a generalized view of productivity and then an overview of the dominant way in which we see it discussed and enacted. We then introduce ourselves and present the study that provided the opportunity to reflect on productivity in greater detail, including a description of the methodology that we used as a guide for reflexive analysis. The results of the reflexive analysis are then presented, detailing the way in which we used this to articulate two alternative conceptions of productivity.

2. A generalized view of productivity and its hegemonic conception

At its root, we understand productivity to be the quality of producing things, with a wide consideration of what qualifies as “a thing.” This generalized view puts us at odds with Adam Smith and other political economists of his time: whereas Smith and others limited productivity to the making of “a tangible and more or less durable object” (Foster, Citation2016, p. 35), we explicitly include the possibility for services and intangibles. We recognize that our backgrounds as health professionals and academics likely influence our perspective; our entire working careers have been devoted to labours that Adam Smith would consider unproductive. We understand productivity as a phenomenon that could be quantified, but that its quantification is intrinsically tied to the conceptualizations and value assessments of the things produced. With inevitable variability in such conceptualizations and value assessments, we see universal metrics of productivity to be elusive and even unnecessary. Foster (Citation2016, p. 25) describes “the basic notion of productivity as a ratio of outputs to inputs in a production process”; we support this notion if we consider that this ratio also exists in an abstract sense, rather than only a quantifiable one, and that the incorporation of inputs into the definition might bring us closer to the meaning of efficiency.

Despite the breadth of this generalized view of productivity, we are most regularly exposed to a much narrower conception that seems to be so well collectively understood that it crowds out much of the broader notion. We are considering this conception of productivity to be hegemonic, in the sense that social representations constrain possibility (Glăveanu, Citation2009). According to our observations, we are interpreting this hegemonic conception to be the maximization of outputs to enable consumption and comfort. We see this conceptualization as being applicable at various scales (i.e. national, institutional, or individual) and through many mechanisms (e.g. employment, entrepreneurship, household tasks). For us, the most remarkable aspects of this conceptualization relate to value: the considerations of what constitutes a valuable product and the extent to which productivity has become a value in and of itself.

With respect to the considerations of valuable products, we note the interest in those which are identifiable and measurable, even if not tangible. Tangible products are material and therefore easy to quantify, presuming there is agreement on the units. Even if immaterial, it is still possible to identify and measure intangibles. One example of an identified and measured intangible product could be a SMART goal (e.g. O’Neill, Conzemius, Commodore, & Pulsfus, Citation2006): here, an abstract thought is refined into an identifiable unit, which is necessarily measured. Another example would be any service for which a person pays a provider. In the case of service provision, the value of the product is more precisely identified through the use of money as a payment mechanism. Indeed, the quantification of value through price is an ideal in neo-liberal economies of impersonal transactions mediated by money. Tasks or chores would equally be considered valuable products: in the hegemonic conception of productivity, these can be delegated for a price, even if they are more often completed individually.

Beyond its capacity to create or acquire value in the hegemonic conception of productivity, we also see productivity as taking on a value in-and-of itself. Around us, we observe friends and colleagues who invest significant effort and derive substantial pride from their productivity. We realize that our perspectives are geographically, culturally, and historically contingent, but also note the reach of the globalized neo-liberal economy. With the neo-liberal imperative for transactional exchanges through the medium of money, enabling the quantification of value production we previously described, we suspect that we are not alone in our observations.

Our observations are primarily interpersonal. Nonetheless, we find these are supported by the macroeconomic perspective presented in Foster’s (Citation2016) “Historical Sociology of Productivist Thought.” Foster’s exploration of the concept of productivity identified a dominant “productivist ideational regime” whereby the conceptual link of productivity and prosperity is so strong that it remains unquestioned despite evidence that it is no longer true (Dufour & Russell, Citation2015). It must be noted that this ideational regime has formed on the foundations of a debt-enabled economy that perpetually races to grow itself into an elusive stability (Lipietz, Citation2013). Accordingly, perpetual growth is an imperative, and it is the civic duty of citizens to contribute to ever increasing levels of consumption and production to support “the economy” (Foster, Citation2016).

Numerous analyses have identified the way in which productivity has been promoted as a valued, and sometimes moral, characteristic by the very people who are expected to be productive. One well-known example of this is Max Weber’s (Citation2001) seminal investigation of the “Protestant Work Ethic.” Weber saw a confluence of characteristics in post-Enlightenment Europe, whereby productivity was seen as a sacred expression of one’s calling, allowing for the widespread development of capitalism. More recently, “productivist behaviour” was accorded “social symbolic value” by farmers in the UK (Burton, Citation2004). Among these farmers, abundant crop production was considered a quality of “a good farmer,” whereas equally profitable alternative activities were viewed in lesser terms. In academia, the anti-productivist scientific movement has been critiqued, without irony, for its potential to negatively affect productivity (Thomaz & Mormul, Citation2014).

3. Our backgrounds and positionalities

Our experiences and worldviews help to explain why we took an interest in this topic and the perspectives that we took to exploring it. Shaun is the PhD student whose thesis research experience stimulated our interest. He came to the research on disability as a physiotherapist who had worked for non-governmental organizations in various locations in the global South (Ashcroft, Griffiths, & Tiffin, Citation2007, p. 124). Through these experiences, he was regularly exposed to a donor-driven perspective of global health, international development, and international relations. This manifested itself through dynamics in which the disadvantaged of the global South depended upon donors for resources, sometimes even for basic needs. Importantly, unlike governmental programming (in principle, at very least), donor-driven programs generally did not have concrete accountability mechanisms to the population that they served (Seckinelgin, Citation2005).

Shaun found two major issues with this donor-driven arrangement. First, it meant that the “beneficiaries” of the services had minimal control over the agenda. Shaun personally encountered these issues through his own work (Cleaver, Citation2016), although there are extensive critiques of this arrangement (e.g. McGoey, Citation2015). A second issue with donor-driven agendas is that of scalability (Liu, Sullivan, Khan, Sachs, & Singh, Citation2011). Since the reach of donor-driven programming is bounded by the amount of resources that the donors are willing or able to share, the boundaries of service are often restrained. With many people in the global South relying upon donor-driven programs with a concomitant lack of control and scalability, Shaun was keen to engage in alternative approaches premised on more collaborative terms.

Lilian is an occupational therapist and senior academic who was a member of Shaun’s doctoral advisory committee. Lilian has experience working with vulnerable groups in Brazil and in Canada. Lilian has been puzzled by some assumptions in people’s perspectives about essential health and social concepts and is alarmed by how these aspects are sometimes neglected by professionals in health and social care despite some scholarly critiques. As an example, she has been interested in attempts to globally standardize and apply concepts such as “quality of life” (Aaronson et al., Citation1992) without much consideration for the different meanings that these intricate concepts entail. Lilian is interested in broadening the dialogue to enable more inclusive conversation (Barcaccia et al., Citation2013).

4. Overview of the study

The fieldwork and analysis experience upon which we are basing this manuscript occurred in the context of Shaun’s doctoral dissertation research project to explore understandings of disability and strategies to improve the situation of persons with disabilities in Western Zambia (Cleaver, Citation2016). This research was grounded in postcolonial disability studies, a research field that is particularly interested in the way that the ongoing legacy of imperialism influences disability (e.g. Grech & Soldatic, Citation2016). The research design was qualitative constructionist (Silverman, Citation2006), and further guided by a critical social science perspective (Eakin, Robertson, Poland, Coburn, & Edwards, Citation1996) with participatory research elements (Herr & Anderson, Citation2005). The participatory elements were important to Shaun as these were direct challenges to the donor-driven approaches to which he had previously been exposed. In designing a study with participatory elements, Shaun took it for granted that he could find, or otherwise create, an environment in which initiative was celebrated and collaboration was desirable. This research project was funded through fellowships from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the W. Garfield Weston Foundation. The project was approved by research ethics committees at [name of university removed], the University of Zambia, and the Zambian Ministry of Health.

Shaun developed the dissertation research project with the guidance of a committee of scholars from Canada, Zambia, and Brazil (including Lilian) and in consultation with national-level Zambian disability self-advocates. The national-level advocates suggested Western Province as a location and connected Shaun with provincial-level advocates, who in turn informed him of the disability groups of which they were aware. These groups included one in the provincial capital of Mongu and another in a rural area of the province. The leaders of the two groups agreed to allow Shaun to approach individual members to seek their consent. Ultimately, there were 81 individual participants from the two groups. The individual participants were primarily persons with disabilities themselves, but also included supportive family members.

The research data for this project were generated through focus group discussions and interviews. Shaun led all data generation activities with the support of a staff of five paid research assistants who were born and raised in Western Zambia. The data generation fieldwork lasted a period of six months in 2014. During this time, Shaun strived to develop contextually-appropriate participatory research relationships with the participating groups and their members in order to create a productive dynamic for knowledge creation and practical action. After the completion of the fieldwork, Shaun conducted thematic data analysis using a six-step process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), with the support of the dissertation advisory committee.

The empirical findings of this research are available in the dissertation (Cleaver, Citation2016), but can be summarized as follows: the participants’ primary understanding of disability was in relation to poverty and the most emphasized strategy to improve the situation of persons with disabilities was help. By help the participants were referring to gifts or grants of material resources from people who possess or have access to such resources. Although the proposed helpers were often other individuals, the participants also regularly identified Shaun as a potential helper in ways that ranged from subtle to direct. When they spoke in this manner, Shaun understood that the participants were requesting material resources from him. These frequent requests occurred despite Shaun having designed the study to pre-empt such possibilities by explicitly communicating in the consent process that participants would receive no direct material benefits.

Shaun had negative emotional reactions to the requests. Having arranged the study around a participatory approach, Shaun felt that he was either executing this approach improperly, or was possibly working with groups that were acting in bad faith. He tried to reduce the frequency of these requests in data generation activities by modifying the dialogue and tried to avoid these happening outside the formal aspects of the research by avoiding interactions in the community. It was only after a cooling off period post-fieldwork that Shaun was able to identify that his reaction was remarkable.

We consider the anecdotes above to be embodied evidence of “disjunctures,” a term used by Mandel (Citation2003, p. 198) to describe a disconnect “between my expectations and experiences in carrying out … fieldwork.” Similar to other doctoral researchers from the global North conducting research in the global South who had experienced disjunctures (Billo & Hiemstra, Citation2013; Mandel, Citation2003; Sultana, Citation2007), we looked back into Shaun’s research process using reflexivity.

5. A reflexive analysis guided by a critical social science perspective (CSSP)

A critical social science perspective (CSSP) (Eakin et al., Citation1996) encourages researchers to take a reflexive posture to their own work, focusing on several key features: assumptions and ideology; the influence of overt, subtle, and covert forms of power; contradiction; and the dialectic between structure and agency. For this reflexive analysis, the features of contradiction, and assumptions and ideology are particularly useful. In a sense, the disjunctures that Shaun experienced were reflections of contradictions between his approach to the research and the results that he was able to identify once he had the insight to understand the data differently.

Guided by a CSSP, we were challenged to use our awareness of this contradiction to shine a light on “the basic assumptions and ideologies underlying the way research problems and methodology are conceived” (Eakin et al., Citation1996, p. 158). We approached our reflexive analysis with the following specific analytic question: what are the assumptions that Shaun took this research that can be made visible by reviewing the disjunctures between research plans and experiences? By asking this question, we identified that Shaun had assumed the values of research participant initiative, collaboration, and contribution. Below, we describe these assumed values in greater detail as well as the ways that we identified them.

5.1. Initiative

Shaun explicitly designed the study to find initiative, particularly through the ways that the participants took initiative to improve their situation. Consistent to this, he understood initiative to be the quality of creating and implementing strategies as potential solutions to important problems.

During the fieldwork phase of the research, it was Shaun’s impression that there were few examples of the participants taking initiative. His lack of detecting initiative, combined with the participants’ requests for help in terms of material resources, initially frustrated him. This combination made Shaun believe that he was unable to find the initiative that the participants wielded, or alternatively, that the participants were just not wielding initiative. Either possibility was distressing: Shaun felt that it was a personal failure if data generation did not detect initiative that was present. Conversely, an absence of initiative on the part of the participants was a failure of theirs.

5.2. Collaboration

In parallel to having designed the study to identify initiative, Shaun also designed it to encourage opportunities to collaborate with at least some of the participants as part of a general action-orientation. Shaun’s impression of collaboration was that it would involve transparent communication about priorities and goals. Shaun hoped that through transparent communication leading to priorities and goals, he and the participants could develop and implement mutually agreeable tactics. The consistency of communication and action was important; an alignment of word and action would be a validation of communication transparency. Furthermore, consistent communication and action would build trust, which could lead to a collaborative relationship. Through the collaboration, at least some participants and Shaun would collectively make contributions (see below) and be productive through the knowledge generated in the research and some related practical activities. The practical activities would likely be realized through the dissemination of knowledge products that were targeted at (mostly local) influential audiences; a tidy synergy between the tasks required in a PhD and those that are useful to participating persons with disabilities.

Shaun did engage in some collaboration during the dissertation fieldwork, but it was more elusive than foreseen, and occurred on terms that seemed somewhat problematic. During the early phases of fieldwork with the participants, there were very few who seemed to relate to his intention to collaborate. A more common understanding of his role that was communicated by the participants (more or less explicitly depending upon the interaction) was that it was Shaun’s role to provide material resources to the participants. This understanding of his role was antithetical to his intention, and therefore a disjuncture between expectation and actual experience.

5.3. Contribution

Unlike initiative and collaboration, Shaun did not explicitly declare his interest in contribution as part of the study design. Instead, he expected contributions to flow out of initiative and collaboration, with individuals and collectives contributing in useful and fulfilling ways. The Oxford Dictionary online (Citation2018) defines contribution as “the part played … in bringing about a result or helping something to advance.” Taking this definition and applying it to the situation he was trying to create through the study, we might have understood contributions to be instances of people devoting effort towards the possibility of a valued outcome. In this sense, Shaun thought that it would be rewarding and valuable for the participants to be able to contribute to their own well-being and that of other persons with disabilities. Contributions would therefore have a component of self-realization in the doing and a component of valued outcome after the doing was done. Furthermore, through the process of contributing, the participants would shape the outputs to be those that were meaningful. Therefore, contribution simultaneously links input and output, while linking process and potential outcome, such that all are more appreciated and of higher quality.

In the experience of the fieldwork, Shaun perceived few examples of participants contributing. If we think of contributions as doing things, what Shaun saw instead was the participants asking for things. According to the approach that Shaun took to the research, doing and asking were mutually exclusive activities in opposition to one another. In trying to create an environment to foster doing, the constant presence and prominence of asking left Shaun disappointed; he presumed that he was either unable to find the contributions that were happening or unable to facilitate opportunities for the participants to contribute.

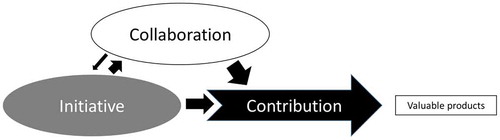

Through reflexive analysis using a CSSP, we identified a series of related assumptions that Shaun took to the research process. When we reflected upon these assumptions collectively, we realized that we could visually represent the way that these assumptions were connected to one another (see Figure ). We consider the collective visual representation to be one conception of productivity. Through our reflexive analysis, we have reason to believe that Shaun approached this research with the expectation that he would support the participants to be productive as per the presentation in Figure .

Despite the evidence demonstrating Shaun’s drive for participant productivity in the research design, this drive was only made visible by its apparent absence. Shaun found no reason to think explicitly about productivity until the time he assessed the participants to be unproductive.

6. Theorizing productivity

We recognized Shaun’s interest as productivity, in the sense that it was consistent to our generalized view. However, we also recognized that Shaun’s approach to productivity seemed to have distinctive features from what we have called the hegemonic conception of productivity. This contrast of conceptions incentivized us to theorize productivity according to the assumptions that Shaun took into this research process. Furthermore, recognizing the contrast between Shaun’s approach to the research and the interaction of the participants, we were also incentivized to theorize productivity from a possible standpoint of the participants. We offer both of these as potential alternative representations (Glăveanu, Citation2009) to the hegemonic conception of productivity.

6.1. Alternative conception #1: Productivity as independent satisfaction of needs

From experience in other locations of the global South, Shaun foresaw the possibility that disability would be associated with scarcity. The association with scarcity was later confirmed in the empirical findings of the research, whereby participants spoke of suffering and a lack of material resources. Also from experience elsewhere, Shaun foresaw the possibility that the scarcity related to disability could be countered through donor support, but that this support would entail significant donor control (McGoey, Citation2015). In contrast to donor support, persons with disabilities could create or acquire valuable products to counter scarcity by being productive. We propose that the goal of this conception of productivity, toward which Shaun unconsciously oriented his research involvement, is the independent satisfaction of needs.

As previously demonstrated in the reflexive analysis leading to Figure , when understood this way, productivity entails initiative, collaboration, and contribution. More literally, initiative entails an expenditure of effort and intent, elements that can be accurately re-identified as toil or trade. Collaboration primarily leads to an infusion of ideas, although it can also result in an important increase in energy. Collaboration can therefore reinforce or synergize the efforts and intentions of those who initiated the productive process. Importantly, this process should result in outputs of valuable products.

Productivity as the independent satisfaction of needs overlaps with the hegemonic conception of productivity in their interest in producing outputs. Despite this commonality, we see many more points of difference, and even divergence, between these two conceptions. To substantiate these points, we draw upon a phenomenon that we see to be aligned with productivity as the independent satisfaction of needs. The phenomenon that we have chosen to draw upon is that of appropriate technologies, “technologies that are easily and economically used from readily available resources by local communities in the developing world” (Pearce, Albritton, Grant, Steed, & Zelenika, Citation2012).

According to this first alternative conception of productivity, individuals and communities in the global South could use appropriate technologies to satisfy their needs more independently than what could be achieved by regularly receiving donations or through exploitative market forces. Critically, the active ingredients of appropriate technologies are abundant: new ideas, the initiative of individuals and collectives, and material resources that are readily available because they are not controlled or claimed by more powerful actors (United Nations Economic & Social Commission for Asia & the Pacific (UN ESCAP), Citation1997). Disadvantaged peoples could therefore deploy appropriate technologies without having to compete, contest, or succumb to coercion from more powerful players, thereby improving their lives while strengthening their autonomy.

Seen through the logic of the hegemonic conception of productivity, appropriate technologies would be valued differently. We argue that the hegemonic conception of productivity is not inclined to seek independence from powerful forces; its orientation is instead toward the maximal production of value for consumption and comfort. From the hegemonic conception of productivity, appropriate technologies would be advantageous only in those cases where their use resulted in more output, or more valued output, than could be achieved by other means.

The value of alternative technologies in this conception of productivity illuminates an important additional element: just as the phenomenon of appropriate technologies was promoted most enthusiastically by people different than local communities in the developing world, so was this conception of productivity. Productivity as an independent satisfaction of needs was unconsciously proposed by Shaun in a research setting and then further developed as a discrete idea with the guidance of colleagues. This process of development was done by outsiders to the groups from which it was seen to be most applicable; persons with disabilities who are experiencing poverty. This is not to say that productivity has never before been thought of this way, but rather that it was the orientation of the researcher, not the researched, in this situation. In approaching scientific literature with a different perspective, we were able to identify similarities between this conception of productivity and a “doctrine of sustainability” that informed HIV programming in Malawi (Swidler & Watkins, Citation2009). Using a different vocabulary, Swidler and Watkins (Citation2009) identify a similar phenomenon: outsiders promoting an agenda of community mobilisation, supported by only minimal resources, for the purpose of community self-sufficiency.

The characteristic of being developed by outsiders does not mean that this conception of productivity is without merit. Instead, alternative conception #1 could be seen as an idea that is made available to local communities as one approach among many for people to use for their own development. Nonetheless, in situations of power imbalances, there might only be a subtle distinction between an influential party—like an apparently privileged visiting researcher—making options available, as compared to imposing them upon others.

6.2. Alternative conception #2: Productively building helping relationships

Recognizing the possibility of alternative conception #1—unconsciously pursued, then more carefully articulated, by outsiders—opened a space for us to ask the following question: how could productivity be conceived from the perspectives of the participants to this research? To answer this question, we reviewed the interactions between Shaun and the participants and reflected upon the ways in which these interactions might be aligned with our generalized view.

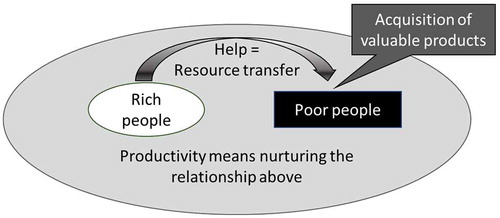

Through the data generation activities, the participants expressed that there were products that were important to them: material resources such as money, food, clothing, housing, and equipment (Cleaver, Citation2016). The participants also expressed that these products could be acquired through help from others who had access to these resources. Although not apparent to Shaun at the time, the participants’ frequent requests for material resources and discussions of help could have been components of a process to cultivate Shaun as a potential helper. According to this alternative reading, the participants were active as producers in creating a relationship to enable the distribution of valuable products from people who had these products to those who needed them (see Figure ). This conception of productivity is distinct from both the hegemonic conception of productivity and productivity as the independent satisfaction of needs in that “the thing” produced is not an output, but is instead a relationship.

For us to see the participants’ interactions as productive, we needed to revisit our perspectives with respect to the types of activities that can be considered economic. Although we have different positionalities, each of us was sufficiently enculturated in the modern (i.e. post-Enlightenment) cultural and economic thought to conceive human relations as essentially distinct from the economic activities of acquiring resources (Mauss, Citation1990). This view persists despite seeing evidence of economic relationships in own cultures. While neither one of us would accuse an entrepreneur of being unproductive for talking about business and trying to build a relationship with potential investors, we somehow saw the participants as unproductive for talking about their needs and trying to build a relationship with Shaun.

Our inability to see this potential conception of productivity might have also been due to the understanding of the role of the researcher in the local political economy. We understood Shaun’s role to be knowledge generation, which could have indirect economic impacts by enabling initiative and contribution through collaboration. By contrast, the participants could have seen a direct economic role for Shaun through help provision. By returning to the actual experiences of the research, and peeling back the layers of how things could or should fit together, it seems highly plausible that the participants were being productive during the data generation through their efforts to build helping relationships. These helping relationships are consistent with the relationships that Maranz (Citation2001) described as a fundamental feature of “African economies.”

7. Discussion: Implications for research and limitations

Inspired by an experience of disjuncture during the conduct of research fieldwork, we have used reflexive analysis to identify assumptions that we took into the research process. We found that our assumptions were related to productivity, an under-considered concept that we see circulating in society. This finding drew us to explore productivity in greater detail, describing the way in which we most commonly see it discussed and enacted, and also two alternative conceptions that we elaborated more specifically from our research experiences. From the totality of this analysis and reflection, we now discuss the implications and the limitations of this analysis.

7.1. Implications

We think that the most important implication of this theoretical paper is a comprehensive one: to draw attention to the possibility that productivity is being understood in a narrow manner, at least in the social circles that we travel, but that things need not be this way. This implication has broad relevance for research, advocacy, and policy purposes. In addition to this, this paper demonstrates the value of a reflexive analysis using a CSSP (Eakin et al., Citation1996), an implication that is broadly applicable to researchers operating from a constructionist paradigm.

7.2. Specific implications for disability research in the global South

The reflexive analysis and subsequent theorizing have implications more specific to disability research in the global South. Most proximally, the analysis and theorizing enabled a change of perspective that was crucial to the empirical analysis of Shaun’s thesis research on disability in Western Zambia. Through this change in perspective, it was possible for Shaun to see the help requested by the participants and as a valid strategy to improve their situation, rather than an indication of dependence (e.g. Knack, Citation2001). Postcolonial disability scholars point to the ways in which the most prominent understandings of disability for research, policy, and practice are those developed according to the concerns and realities of the global North (Grech & Soldatic, Citation2016; Miles, Citation2007). Could Shaun’s interest in productivity have been inadvertently influenced by the hegemonic conception of productivity that we see as being particularly potent in the global North? We think that this is possible, such that the assumption about the importance of productivity could even be reflective of a productivist ideational regime (Eakin et al., Citation1996; Foster, Citation2016). Given this dynamic, we think that it can be useful for disability researchers to actively consider the way in which the hegemonic conception of productivity could affect their own perspectives. This is particularly relevant, seeing as persons with disabilities are especially vulnerable to productivism, the “cultural and material invalidation of those considered to be unable to work” (Mladenov, Citation2017).

7.3. Limitations of the reflexive analysis

Reflexivity has been critiqued as an exercise where researchers can “fall into an infinite regress of excessive self-analysis” (Finlay, Citation2002, p. 532). Such critiques are obvious concerns. On the flip side, reflexivity is seen as an essential element of research conducted from constructionist epistemologies (Breuer & Roth, Citation2003) and in the service of social justice (Hall, Citation1996). For these reasons, reflexivity cannot be ignored. Weighing the concerns about reflexivity with its necessity and its potential compels us to identify the limitations of this analysis.

This reflexive analysis is not intended to be deterministic. Instead, it provides an opening for further considerations. The origin of this analysis was personal and emotional, beginning with an exploration of things that felt remarkable. It is from this foundation that the intellectual analysis guided by a CSSP continued. The reflexive question that we asked, about the assumptions that led to the disjunctures, was by no means the only one possible, but it was consistent with the personal and emotional impetus for the reflexive analysis. Like all knowledge generated in a constructionist epistemology, this reflexive analysis is partial and contextual. Nonetheless, its value to illuminate the taken-for-granted outweighs its limitations.

7.4. Limitations of the theoretical contribution

Our approach to theorizing was firmly grounded in our perspective and worldview, one which might be admittedly different from the perspectives and worldviews of the participants. We take ownership for this grounding, and believe that it allowed us to create useful alternative perspectives to a largely unquestioned phenomenon. Nonetheless, had this paper been devised from the worldview of the participants, there is reason to believe that it would have been very different. In theorizing the participants’ interactions in the research field as productivity, there is a risk that we are culturally appropriating ways of being that are conceived in very different terms. We are aware of the power that we have as the narrators of this account and acknowledge the risk of cultural appropriation (Rogers, Citation2006). Concurrently, see the alternative perspectives that we have created here as valuable in broadening our worldview to new possibilities and understanding.

We have presented the conceptions of productivity as discrete entities to be consistent with our observations and for clarity: this style of presentation emphasizes the contrasts. Nonetheless, there is reason to believe that aspects of these discrete presentations could operate simultaneously. Indeed, having identified productivity as a concept of interest, we were able to locate references to it in research on disability in South Africa, a country that is geographically near and culturally similar to Zambia.

Van Niekerk, Lorenzo, and Mdlokolo (Citation2006) conducted an intervention aimed at poverty alleviation for persons with disabilities. Entrepreneurial training for these participants “afforded them the opportunity to become productive members of their community and to contribute financially to the economic independence of their respective families” (Van Niekerk et al., Citation2006, p. 329). Furthermore, the authors cite the necessity of individuals contributing to the community in order to belong to that community, as per the traditional African philosophy of ubuntu (see also, Metz, Citation2017). Similar to the conception that Shaun took into his research, Van Niekerk et al. (Citation2006) seem to emphasize the importance of productivity for the satisfaction of needs. However, different from alternative conception #1 described in this paper, Van Niekerk et al. (Citation2006) do not prioritize independence from external donors. Instead, their conception of productivity involves a combination of independence and interdependence, whereby resource-generation through toil or trade is important for family and community life. In the language of the participants of Shaun’s research, if successful, Van Niekerk et al.’s (Citation2006) entrepreneurial training would allow persons with disabilities the opportunity to provide help to their family and community.

Meanwhile, in their study on disability grants, also in South Africa, Hansen and Sait (Citation2011) present the relation of disability, ubuntu, and productivity in a different light. According to Hansen and Sait (Citation2011), persons with disabilities can support their communities and build connections by sharing state-sponsored social welfare resources. Persons with disabilities are active agents in these productive activities, but like alternative conception #2, resources are acquired through mechanisms that do not include toil or trade. Similar to the participants in Van Niekerk et al.’s (Citation2006) research, it seemed to be the expectation of participants in Hansen and Sait’s (Citation2011) study that they would share resources once acquired, putting themselves in the position of helpers.

8. Final considerations

Through this reflexive analysis of disjunctures experienced during doctoral dissertation research on disability in Western Zambia, it was possible to identify a deeply held assumption about the importance of productivity on the part the researcher. Identification of this assumption opened a space for us to explore conceptions of productivity, including a hegemonic conception of maximizing outputs and two alternative conceptions that a wide selection of actors can draw upon for inspiration. This analysis also shone a light on specific implications for postcolonial disability research.

Funding

Shaun Cleaver was funded for this dissertation research by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Fellowship and a W. Garfield Weston Doctoral Fellowship.

Acknowledgements

The research was conducted under the supervision of Stephanie Nixon and Helene Polatajko. Doctoral advisory committee member Virginia Bond and research assistants Patrah Kapolesa, Miyanda Lastford Malambo, Lynn Akufuna Nalikena, Aongola Mwangala, and Kashela Chibinda were crucial to this project’s success. In addition, colleagues at the Zambian Federation of Disability Organisations (ZAFOD) and the Western Province offices of the Government of Zambia’s Department of Social Welfare provided important connections and assistance.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shaun Cleaver

Dr Shaun Cleaver completed his PhD research in the Rehabilitation Science Institute at the University of Toronto. He has continued to work with persons with disabilities in Western Zambia and is now a postdoctoral fellow at McGill University. His current work is focused on disability policy, particularly the new Social Cash Transfer program that has recently been rolled out in Zambia. The research reported in this paper allows Shaun to approach his ongoing research relationships with greater acceptance and understanding.

Lilian Magalhães

Dr Lilian Magalhães is an adjunct professor at the Federal University of Sao Carlos, Brazil. Her current research interests focus on emancipatory health practices, community engagement, and inclusion. She usually adopts innovative visual methods, which afford interesting venues to convey the participants “narratives of marginalization and occupational injustice”.

References

- Aaronson, N. K. , Acquadro, C. , Alonso, J. , Apolone, G. , Bucquet, D. , Bullinger, M. , … Ware, Jr, J. E. (1992). International quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. Quality of Life Research , 1 (5), 349–351.10.1007/BF00434949

- Ashcroft, B. , Griffiths, G. , & Tiffin, H. (2007). Post-colonial studies: The key concepts (2nd ed.). Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- Barcaccia, B. , Esposito, G. , Matarese, M. , Bertolaso, M. , Elvira, M. , & De Marinis, M. G. (2013). Defining quality of life: A wild-goose chase? Europe’s Journal of Psychology , 9 (1), 185–203.10.5964/ejop.v9i1.484

- Billo, E. , & Hiemstra, N. (2013). Mediating messiness: Expanding ideas of flexibility, reflexivity, and embodiment in fieldwork. Gender, Place & Culture , 20 (3), 313–328.10.1080/0966369X.2012.674929

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3 , 77–101.10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Breuer, F. , & W.-M., Roth . (2003). Subjectivity and reflexivity in the social sciences: Epistemic windows and methodical consequences. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research , 4 (2), Art. 25.

- Burton, R. J. F. (2004). Seeing Through the ‘Good Farmer’s’ Eyes: Towards Developing an Understanding of the Social Symbolic Value of ‘Productivist’ Behaviour. Sociologia Ruralis , 44 (2), 195–215.10.1111/soru.2004.44.issue-2

- Cleaver, S. (2016). Postcolonial encounters with disability: Exploring disability and ways forward together with persons with disabilities in Western Zambia ( Doctoral diss.). University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

- Cleaver, S. , Magalhães, L. , Bond, V. , Polatajko, H. , & Nixon, S. (2016). Research principles and research experiences: Critical reflection on conducting a PhD dissertation on global health and disability. Disability and the Global South. , 3 (2), 1022–1043.

- Contribution . (2018). In Oxford Dictionaries . Retrieved April 3, 2018, from http://en.oxforddictionaries.com

- Davies, B. , & Bansel, P. (2010). Governmentality and academic work: Shaping the Hearts and Minds of Academic Workers. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing , 26 (3), 5–20.

- Dufour, M. , & Russell, E. (2015). Why Isn’t productivity more popular? A bargaining power approach to the pay/productivity linkage in Canada. International Productivity Monitor , 28 , 47–62.

- Eakin, J. , Robertson, A. , Poland, B. , Coburn, D. , & Edwards, R. (1996). Towards a critical social science perspective on health promotion research. Health Promotion International , 11 (2), 157–165.10.1093/heapro/11.2.157

- Finlay, L. (2002). “Outing” the researcher: The provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qualitative Health Research , 12 (4), 531–545.10.1177/104973202129120052

- Foster, K. (2016). Productivity and prosperity: A historical sociology of productivist thought . Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Glăveanu, V. P. (2009). What differences make a difference?: A discussion of hegemony, resistance and representation. Papers on social representations , 18 , 2.1–2.22.

- Grech, S. & Soldatic, K. (Eds.). (2016). Disability in the Global South: The Critical Handbook . Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Hall, S. (1996). Reflexivity in emancipatory action research: Illustrating the researcher’s constitutiveness. In O. Zuber-Skerritt (Ed.), New directions in action research (pp. 23–40). London: Falmer Press.

- Hansen, C. , & Sait, W. (2011). “We too are disabled”: Disability grants and poverty politics in rural South Africa. In A. H. Eide & B. Ingstad (Eds.), Disability and poverty: A global challenge (pp. 93–118). Bristol: The Policy Press.10.1332/policypress/9781847428851.001.0001

- Herr, K. , & Anderson, G. L. (2005). The action research dissertation: A guide for students and faculty . Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.10.4135/9781452226644

- Knack, S. (2001). Aid dependence and the quality of governance: Cross-country empirical tests. Southern Economic Journal , 68 (2), 310–329.10.2307/1061596

- Lipietz, A. (2013). Fears and hopes: The crisis of the liberal-productivist model and its green alternative. Capital & Class , 37 (1), 127–141.10.1177/0309816812474878

- Liu, A. , Sullivan, S. , Khan, M. , Sachs, S. , & Singh, P. (2011). Community health workers in global health: Scale and scalability. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine , 78 (3), 419–435.10.1002/msj.v78.3

- Mandel, J. L. (2003). Negotiating expectations in the field: Gatekeepers, research fatigue and cultural biases. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography , 24 (2), 198–210.10.1111/sjtg.2003.24.issue-2

- Maranz, D. (2001). African friends and money matters . Dallas: SIL International.

- Mauss, M. (1990). The gift: The form for exchange in archaic societies . Translated by W. D. Halls . London: Routledge.

- McGoey, L. (2015). No such thing as a free gift: The gates foundation and the price of philanthropy . New York, NY: Verso Books.

- Metz, T. (2017). Managerialism as anti-social: Some of Ubuntu’s implications for knowledge production. In M. Cross & A. Ndofirepi (Eds.), Knowledge and change in the African University: Volume 2—Re-imagining the Terrain (pp. 139–154). Rotterdam: Sense.10.1007/978-94-6300-845-7

- Miles, M. (2007). International strategies for disability-related work in developing countries: Historical, modern and critical reflections . Retrieved April 2018, from http://www.independentliving.org/docs7/miles200701.html

- Mladenov, T. (2017). From state socialist to neoliberal productivism: Disability policy and invalidation of disabled people in the postsocialist region. Critical Sociology , 43 (7–8), 1109–1123.10.1177/0896920515595843

- O’Neill, J. , Conzemius, A. , Commodore, C. , & Pulsfus, C. (2006). The power of SMART goals: Using goals to improve student learning . Bloomington: Solution Tree Press.

- Pearce, J. , Albritton, S. , Grant, G. , Steed, G. , Zelenika, I. (2012). A new model for enabling innovation in appropriate technology for sustainable development. Sustainability: Science, Practice, & Policy , 8 (2), 42–53.

- Rogers, R. (2006). From cultural exchange to transculturation: A review and reconceptualization of cultural appropriation. Communication Theory , 16 , 474–503.10.1111/comt.2006.16.issue-4

- Seckinelgin, H. (2005). A global disease and its governance: HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa and the agency of NGOs. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations , 11 (3), 351–368.

- Silverman, D. (2006). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- Sultana, F. (2007). Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: Negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies , 6 (3), 374–385.

- Swidler, A. , & Watkins, S. C. (2009). “Teach a man to fish”: The sustainability doctrine and its social consequences. World Development , 37 (7), 1182–1196.10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.11.002

- Thomaz, S. M. , & Mormul, R. P. (2014). Misinterpretation of ‘slow science’ and ‘academic productivism’ may obstruct science in developing countries. Brazilian Journal of Biology , 74 (3), S1–S2.

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP) . (1997). Appropriate paper-based technology (APT). Retrieved April 2018, from http://www.dinf.ne.jp/doc/english/intl/z15/z15005s3/z1500519.html

- Van Niekerk, L. , Lorenzo, T. , & Mdlokolo, P. (2006). Understanding partnerships in developing disabled entrepreneurs through participatory action research. Disability and Rehabilitation , 28 (5), 323–331.10.1080/09638280500166425

- Weber, M. (2001). The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism . Translated by T. Parsons . London: Routledge Classics.