Abstract

Today the second most important country after the United States, in the number of ecovillages, and by far, the most prominent in Europe, is Spain. The question to be addressed here is whether this revival or boom of ecovillages in Spain is an incipient social transformation and cultural change, following Erik Olin Wright theory of emancipatory social transformation. This work is divided into five main sections. The first one introduces three different approaches that remark the importance of ecovillages for radical cultural and social studies. The second part explains the methodology performed for the study of 29 ecovillages in Spain, using six critical variables on material interests and ideology, following Wright’s concepts. The third section explored the set of arguments that are mobilized to support and create an ecovillage project in Spain, and its relationship with the neo-rural movement and grouped in two categories: ideology and material interests. The two final sections present some results on the analysis performed for 29 cases, and a discussion on social reproduction practices performed by ecovillages, dividing it between conventional and interstitial strategies, to contrast the discourse of ecovillages with Wright’s theory.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Spain is currently the second most important country after the United States, in number of ecovillages, and by far, the most prominent in Europe. The question to be addressed here is whether this situation is due to an incipient social transformation and cultural change. To answer this question, this research has studied 29 ecovillages around the country, and has analyzed how do they cope with basic needs, such as water or energy supply, food or economic activities to examine if they are introducing alternative anticapitalist practices. Only a minority of these ecovillages, some with a long tradition, can be considered as good examples of projects seeking a profound social transformation.

1. Introduction

When we think of alternative lifestyles, especially communitarian practices critique with capitalist society, ecovillages are often one of the first clear examples that come to mind. In recent years, ecovillages have received renewed interest from academia as an object of study of forms of life radically opposed to the consumerist, materialist, and individualist societies that are the canon of capitalist society. There are at least three approaches interested in focusing research on ecovillages as radical practices. In the first place, the degrowth movement (D’Alisa et al., Citation2015; Latouche, Citation2007) advocates downshifting, and the transition toward more socially and environmentally just societies and against extreme consumerism they propose voluntary simplicity (Latouche, Citation2007), being ecovillages an exciting model for these authors. Secondly, ecovillages are a point of interest for authors that reclaim the commons as a set of practices that historically has characterized many rural areas and that are worth to be rescued for an excellent alternative to capitalism. The commons paradigm has been defended as a good alternative beyond private and statist solutions for the management of natural resources (Ostrom, Citation1990) and in a broader sense, for production and social reproduction, from the housing to family raising, education, or health (Laval & Dardot, Citation2015; Menzies, Citation2014). In this sense, ecovillages as a construction of an emancipatory project that covers all the essential aspects of life, from habitat to food, social relations, work, leisure… is an excellent field of study in which to analyze the obstacles and challenges entailed by the adoption of an alternative lifestyle. Finally, ecovillages practices are often interpreted as exciting examples of the new paradigm and even business model, the so-called sharing economy, especially concerning consumption patterns (Hong & Vicdan, Citation2016) or their social innovation (Avelino et al., Citation2015).

In the case of Spain, for a little more than a decade, coinciding with the beginning of the Great Recession, dozens of alternative projects of intentional communities have appeared, usually in rural areas. Broadly speaking, on the one hand, the expulsion of thousands of people from the labor market by the crisis, together with the impossibility of accessing the housing market on the other, along with a particular rural geography where abandoned villages or with very few neighbors are common to find, are some factors that explain this boom of ecovillages (Carretero, Citation2013), “transition” villages, sustainable housing cooperatives and many other radical experiences. Many people, especially young people, feel unhappy with dominant models of urban life based on consumerism, hypermobility, digital hyperconnectivity, and indebtedness as a way of accessing to housing and basic needs. Therefore, they seek alternative ways of life more in contact with nature, in a community or less consumerist and stressing, being ecovillages, historically one of the most attractive alternative life projects. Nevertheless, one key question to address is how “alternative” is today the landscape of ecovillages in Spain.

Wright’s works on political utopias based on different emancipatory social transformation theories and more precisely his discussions on ideology and material interests is an interesting theoretical background to address this question. Wright (Citation2010) develops an interesting theory for transformation and social emancipation in which proposes three different utopias: ruptural, interstitial, and symbiotic transformations. Ruptural transformations are associated with revolutionary socialist or communist political traditions, with the primary objective of confronting the bourgeoisie and attacking the capitalist state. Interstitial and symbiotic transformations envision a trajectory of change that progressively enlarges the social spaces of social empowerment, but interstitial strategies largely by-pass the state in pursuing this objective while symbiotic strategies try to systematically use the state to advance the process of emancipatory social empowerment (Wright, Citation2010, p. 228). In this sense, interstitial strategies are more associated with anarchism ideology and symbiotic metamorphosis with social-democratic political traditions. The emergence and consolidation of the ecovillage movement is historically framed in interstitial strategies that, rather than opposing the capitalist state, construct alternatives to it, trying to build societies entirely unconnected from the hegemonic capitalist political and economic system. In fact, the author himself proposes the hippy movement as the clearest example of interstitial strategies within a capitalist state.

Wright’s theory of social transformation proposes four clusters of mechanisms through which institutions of various sorts affect the actions of people, individually and collectively: coercion, institutional rules, ideology, and material interests. These constitute mechanisms of capitalist social reproduction to the extent that they, first, obstruct individual and collective actions which would be threatening to capitalist structures of power and privilege, and second, channel actions in such a way that these measures positively contribute to the stability of those social structures, mainly through the means in which they participate in passive reproduction of the capitalist system (Wright, Citation2010, p. 195). To analyze the ecovillage movement through Wright’s theory would require questioning how do they challenge in their every-day practices this cluster of mechanisms imposed by the capitalist State generating some interstitial strategies to face coercion and institutional rules from the State, as well as solving material interests with an alternative ideological approach beyond market logic. This analysis is too broad for this research paper so that the focus will be put only in two of the social reproduction mechanisms proposed by Wright: ideology and material interests, leaving the two others for future contributions.

The aim of this paper is, therefore, to assess following Wright’s emancipatory social transformation theories (Wright, Citation2010), whether the current boom of ecovillages emerged in Spain in recent years, could be labeled as radical practices within a broad social transformation project. This research is not an empirical one based on a systematic study of the great variety of ecovillages existing in Spain and their daily practices. The primary purpose here is to confront theory on social emancipation with a key author on the topic like Wright, with the practice in one of the most important cases of intentional community designed precisely as a utopia: ecovillages.

2. Methodology

The starting point for this article was a seminar organized in December 2016 at the Polytechnic University of Valencia (Spain),Footnote1 with the participation of Global Ecovillage Network members, and namely from the Sieben Linden ecovillage in Germany, one of the most prominent and long-lasting ecovillage projects in that country. The theoretical foundations of the paper are based on Wright’s contributions on a theory for social emancipation. A three-step methodology was carried out to assess whether ecovillages in Spain fit to what Wright calls social transformation strategies (Wright, Citation2010). Comparing different literature, a definite definition of ecovillage was chosen: “A human-scale settlement that is intended to be full-featured—providing food, manufacturing, leisure, social opportunities, and commerce—the goal of which is the harmless integration of human activities into the environment in a way that supports healthy human development in physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual ways, and is able to continue into the indefinite future” (Bang, 2005, cited by Kasper, Citation2008). Based on the database of ecovillage projects in Spain (GEN, Citation2016), four sampling criteria discussed in the seminar mentioned above were introduced to have a robust, up-to-date and realist sample of ecovillage projects that fits this definition:

(a) The project had to be active by the time the research was conducted (2017). Many projects were excluded when this criterion was applied because they were still under formation or construction or because they were inactive.

(b) Only communities of more than one family were chosen.

(c) Hotels and tourism-related business activities were excluded, although some of them advertise as “ecovillages.”

(d) Closed religious or spiritual communities in isolated areas, such as alternative or Buddhist centers with no other aim than religious activities, were as well excluded.

After applying these criteria, 29 ecovillages were chosen. Each of them was contacted by email, to collect primary data about how each community cope with basic and material needs. As well, all the information available on the internet about each of these ecovillages was analyzed. A total of six variables were chosen, inspired on the “four windows into sustainability”—ecology, economics, community, and consciousness proposed by Litfin’s analysis on different ecovillages around the world (Litfin, Citation2014). These principles fit with Wright’s definition on material needs and ideology as a tool for social empowerment: (1) Access to water; (2) Energy supply; (3) Food model; (4) Construction techniques; (5) Ownership model, and (6) Economic activities. An Ecovillage Database with 29 cases and six variables was developed (see Table , Annex, Table ).

The first four variables relate to material needs that are usually embedded in market logics in western liberal democracies, such as Spain. Alternative projects seeking to generate their energy, water supply, construction materials, or food production outside market logic, therefore, would be an excellent example of emancipatory social transformation. The other two criteria, refer to essential aspects for an ecovillage project within the socio-economic sphere, that again, can be embedded or contest market-oriented logic or institutions, becoming, therefore, substantial practices within Wright’s definition on emancipatory social transformation practices. In this sense, the community-owned ecovillages, cooperatives, or neo-rural movements reclaiming and developing traditional rural commons were considered excellent examples of interstitial strategies or social empowerment practices, whereas ecovillages with traditional access to land by purchase or rent, were deemed to be noninterstitial or conventional practices. Therefore, from the information provided by ecovillages, each of the six variables was divided into two categories: conventional and interstitial strategies for social reproduction (see Table ).

Table 1. Conventional and interstitial strategies for social reproduction in Spanish ecovillages

Finally, a 3-day visit to one of the most consolidated ecovillages in Spain, the Matavenero (León) case (Fernández, Citation2013), was carried out, along with five short interviews with three open questions (see Annex), in order to contrast some of the analysis carried out and, therefore, to adequately address the final discussion of this research. Following local community rules, no photographs or recording interviews could be included, so that the information obtained during this fieldwork has to be considered as a support qualitative data. The analysis of material interests management (water, energy, construction materials, and food) as well as the political, social, and economic model of each ecovillage (type of ownership and economic activities), complemented with the informal interviews carried out, can give impressive insights to address the central question of this research, about the consideration of ecovillages as radical practices.

3. Exploring ecovillages in a neo-rural context: the case of Spain

According to Dawson (2015, cited by Accioly et al., Citation2017), ecovillages are highly heterogeneous, and it is impossible to describe one model that covers all cases. This heterogeneity stems from their diverse origins including the ideals of self-sufficiency and spiritual inquiry of monasteries, Buddhist movements; ecologist, pacifist, feminist, and alternative education movements; the back-to-the-land and cohousing movements in developed countries and participatory development and technological appropriation movements in the Global South (Litfin, Citation2014). The Global Ecovillage Network (Global Ecovillage Network, Citation2016) defines the term ecovillage as an intentional, traditional, or urban community using local participatory processes to integrate ecological, economic, social, and cultural dimensions of sustainability to regenerate social and natural environments. Nevertheless, this global network remarks the heterogeneity of practices included under the umbrella of the ecovillage concept.

In contrast, a more precise definition of the neo-rural concept is easier to find in academic literature. According to Folch (Citation2011), the neo-rural movement could be defined as a group people who leave their place of origin, usually the city, for their own decision, to settle in a rural environment, to establish a community life project. Cultural and artistic movements such as Romanticism, authors such as Thoreau, political movements such as Utopian socialism of Fourier, Owen or Saint-Simon, and in the twentieth century the hippy movement or May 68, and above all the awakening of environmental consciousness, are the ideological referents for both neo-rural and ecovillage movements (Resina & Viestenz, Citation2012; Fernández, Citation2013, p. 3, Accioly et al., Citation2017).

However, in the decision to change the way of life, from a capitalist urban model to an alternative one, for some authors such as Hervieu and Léger (Citation1979), there are other more practical reasons: primarily the lack of job opportunities in the city. Hervieu and Léger (Citation1979) argue that rather than return to the countryside, we should talk about the countryside as a resource for unemployment, crisis, pollution and the bureaucratization of social life. In any case, it is a phenomenon consolidated worldwide after several phases, the last corresponding with the international financial crisis of 2007. “neo-rurals” are today very settled in many rural territories, supposing the emergence of a new territoriality, an original conception of existing relationships between individuals and their biosocial environment, a transition from nonplaces into which many standardized cities have become, to places surrounded by nature and landscape (Nogué, Citation1988, p. 154). In fact, the rural environment becomes for many young people disenchanted with urban life, in a sort of watchtower from which to look at the world, and in a point of reference for the construction of a differentiated identity, as Relph stated:

“The neo-rural is, in fact, an immigrant who needs to take root in his new environment, who needs to create “places” in a space that for him, still has no places. His project of life in contact with nature, his desire to integrate into the rural society that surrounds him, will help him to achieve, with relative ease, “existential interiority” (Relph, 1976, quoted by Nogué, Citation1988).

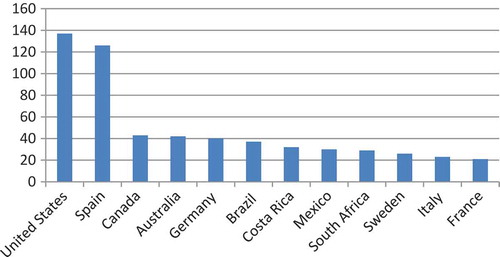

Ecovillages and “‘neo-rurals’” are, therefore, two concepts narrowly linked but apparently differentiated. Nevertheless, there is an important gap of literature upon the analysis on ecovillages through a neo-rural lens, at least for the case of Spain, even though this is today a crucial topic to understand rural areas in this country. At present, according to data from the Global Ecovillage Network, the number of ecovillage projects is well over 1,000 in a total of 110 countries (GEN, Citation2016). Spain occupies no less than the second place in the world in ecovillages, only surpassed by the United States, a nation quite bigger in area and population than any European country (see Figure ).

The success of the neo-rural phenomenon in Spain is due to a set of push-pull factors (Del Romero, Citation2018; Marconi, Citation2015). On the one hand, Spain is a country with 8,116 municipalities of which 4,929, 60%, has less than 1,000 inhabitants and 1,238 has less than 100 inhabitants (INE, Citation2018). The rural exodus and the crisis have been so profound in this country that in almost all the autonomous communities, but especially in the north (Galicia, Asturias, Castile, and Leon and Aragon mainly) it is normal to find abandoned villages and thousands of empty houses and farmyards susceptible of being occupied or inhabited again by “neo-rurals” (Del Romero, Citation2018). Furthermore, many of these places usually have lands of labor, pastures, and forests of good quality. Apart from that, Spain is a Mediterranean country with a pleasant climate that significantly facilitates the development of projects linked to agriculture or livestock. The benign climate of a large part of regressive rural areas makes it possible to grow a vast range of fruit and vegetable varieties even throughout the year. It is also quite accessible from the central urban regions from which the “neo-rurals” come, such as Madrid and Barcelona, or other European cities such as Paris, London, Frankfurt, or Milan. This geographical condition has led, according to some authors, to a “naturbanization” process in some rural areas (Pallarès-Blanch, Prados, & Tulla, Citation2014; Prados, Citation2009). It is defined as the search of new living spaces in unspoilt areas of high environmental and aesthetic quality, often by neo-rural communities, in order to create ecovillages that impulse traditional agricultural activities and other activities based upon the consumption of nature (Prados, Citation2009: VII)

The criticism to urban hyperconnected and exhausting ways of life would be the primary “push factor.” Different contributions develop this process. Guirado (Citation2011) analyzes the motivations for “neo-rurals” coming from different European countries, to change the urban-based life project, to a small intentional community, usually in isolated mountainous areas, and remark the stressing urban life as a critical factor. Cáceres-Feria and Ruiz (Citation2017) broaden this analysis focusing on the role of social, cultural and economic activation played by foreign “neo-rurals” arrived from western European cities to Spanish rural areas in crisis, especially in the 1980s and 1990s, when land regulation and housing permits were less strict. In contrast, Cortes-Vazquez (Citation2014) studies the conflicts of power relations between “neo-rurals” and other social groups in rural through the analysis of everyday practices, concerning the right to use and access local resources. All these authors agree that a critical push factor was indeed the financial crisis, which mainly affected Spain between 2007 and 2014. Some authors studied the massive incorporation of new generations of young people into many ecovillages and rural areas in general (Fanjul, Citation2015; Hilmi & Burbi, Citation2016).

In the analysis on the counterhegemonic potential of some rural communities, including ecovillage projects, some contributions focus on the development of alternatives to cover basic needs outside the market logic (Accioly et al., Citation2017; Halfacree, Citation2007; Litfin, Citation2014; Wilbur, Citation2013). In Spain, some crucial works include the study of alternative food economies, repeasantization, and food sovereignty movements (Calvário, Citation2017; Calvário & Kallis, Citation2017), alternative housing strategies, focusing on rural squatting (Cattaneo & Gavaldà, Citation2010), and a broader literature on bioconstruction and eco-homes construction (Pickerill, Citation2016) and ecovillages as alternative lifestyles (Marconi, Citation2015). These contributions have in common the study of ecovillages in Spain populated by “neo-rurals” coming from urban environments, discontent, or critic with capitalist logic.

4. Coping with ideology and material interests in Spanish ecovillages

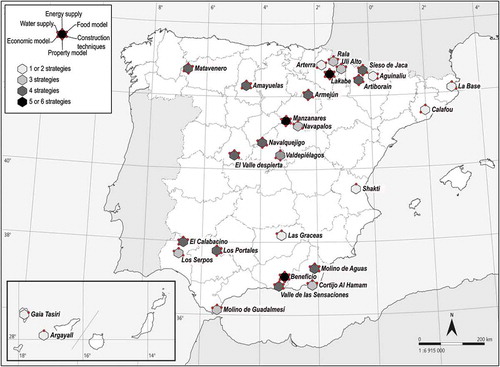

The following two figures show the primary results of the database constructed to address the question whether neo-rural movements are developing in ecovillages emancipatory social transformation practices that could be considered as interstitial strategies and each percentage refer to a number of ecovillages according to the information extracted from each ecovillage. Figure shows in a map the location of the 29 studied ecovillage projects with their approximate population. Figure illustrates how these ecovillages are coping with ideology and material interests, according to Wright’s theory of social transformation, following the methodology exposed in Section 2. It shows how many interstitial strategies have been identified in each ecovillage. Finally, the primary data about the 29 ecovillages can be found in the Annex.

Figure 3. Ideology and material interests in Spanish ecovillages. Ecovillages with interstitial strategies

As it can be stated from Figure , all of the ecovillages studied are found in a rural environment, almost always in mountainous areas far away from the main cities and tourist areas of the country, except perhaps for the two cases in the Canary Islands. 44% are abandoned or partially rehabilitated villages, 24% are rural farms, and 16% are new settlements. Therefore, most of the projects are developed in formerly populated areas. Geographical conditions play a role as well, as we explained in the previous section. Nine ecovillages, 31% of the studied data, are located in Andalusia, a sunny region with soft winters and proper environmental conditions for agriculture purposes. Other territories with the similar Mediterranean or subtropical climatic conditions could be Catalonia, Valencia or the Canary Islands, together with five more ecovillages, so that almost 50% of ecovillages are located in Mediterranean sunny regions. The other 50% is concentrated in inland mountainous areas that offer a combination of available land and abandoned dwellings, with relative good accessibility from central cities, fundamentally Madrid and Barcelona. Ten ecovillages (34,4%), are located less than three hours by car from these urban areas, and the vast majority are accessible from other significant metropolitan regions, such as Valencia, Sevilla, Bilbao, or Saragossa in less than 2 hours.

The results of the analysis of material and ideology interests show a certain heterogeneity nevertheless. A common trend is found for the two first variables: water and energy access. Almost 60% have their water cycle and 62% renewable energy sources. Many ecovillages remark the importance of self-management concerning energy and water in their discourses and project descriptions, and in many cases, it is put into practice as a critical element of the project. This consensus includes as well food sovereignty. The vast majority of ecovillages claim to be looking for alternative food supply chains and self-production linked to permaculture, agro-ecology, or vegan diet defense discourses. Almost 60% of ecovillages have a high degree of food self-production, which is apparently an excellent example of interstitial strategy to face one of the most criticized aspects of conventional social reproduction under capitalism: food, nutrition, and health. Nevertheless, though most ecovillages do have agriculture and livestock activities, hardly a third claim to be 100% natural growers. In this sense, ecovillage projects are not always related to ecological cultivation, since there are many which dedicate themselves to education activities of all kinds, from courses of bioconstruction to yoga or training in permaculture for example, and they still rely on conventional food supply chains.

Consensus on the other three variables is not so clear to find. 55% of ecovillages state unequivocally that the settlement was built with natural, local and ecologic construction materials following bioconstruction criteria. A total of 34.7% follow an alternative or radical model for land access, such as squatting, cooperatives of communal property, and less than 28% have alternative economic or currency models, such as social currencies, barter systems, promotion of local exchange, non capitalist peasantry activities or communal production systems. Beginning with the last variable, this is maybe the most complex to analyze, as it involves job, incomes, relationships with local population, money and necessary living costs, such as education, health or some basic needs that today are hardly supplied in small ecovillages. An excellent example of this complexity is the case of Matavenero. Many inhabitants in ecovillages have different jobs outside the community, whereas other members work for the community, receiving a salary in exchange:

If you come without anything, you can earn a living by helping others (and this is one of the reasons why some people go to ecovillage), but if you have nothing to offer, you need your economy to survive.

Interview 1: Craftsman.

Unlike the first ecovillages that emerged in the 1960s that were mainly devoted to agriculture and livestock or handicrafts (Nogué, Citation1988), there is now a greater diversity of profiles. There are still many ecovillages that combine a profile of farmer and artisan, but a second model is that of ecovillage as a center for training and temporary stay. Lastly, there are a large number of ecovillages, almost a third of which combine a wide range of activities, from the manufacture of handicrafts to a wide range of training, forestry activities or other job places in other villages. Hence, it is difficult to reduce this variety to a binary distribution of conventional or radical economic practices. It is as well interesting to observe, after the study of this variable, the complexity of the relationship between “neo-rurals” and the local population. Only in one case, Valdepiélagos in Madrid, the ecovillage is itself a part of a village, while the rest are in abandoned or isolated areas.

Another critical issue is access to a property. The vast majority of neo-rural communities decide to buy or rent land (property model variable), even if the investments required are considerable.Footnote2 Paradoxically, the Spanish rural environment is rich in traditions of community management and cooperatives. Many lands, forests, and pastures, as well as mills, ovens, schools, or houses, nowadays abandoned, were once built and maintained by a local community, and not by a modern Nation state, and therefore were neither private nor private properties (Del Romero, Citation2018). Very few ecovillages, specifically only three, have incorporated in their project the recovery of these commons with the connivance, or knowledge of the local population, and seem to prefer a model based on private property, which is not associated with radical anarchist discourses that rely on squatting or communes as alternative models. This issue could be an excellent example of what Accioly et al. (Citation2017) calls the elitist character of ecovillages from the Global North, with a similar profile that is mainly middle or upper middle class with a high purchase power (Ergas, 2010, cited by Accioly et al., Citation2017).

Finally, ecovillages that claim to be following bioconstruction criteria, local and sustainable materials and techniques, include only 55% of ecovillages. Most other cases recognize that they use conventional materials, such as concrete, plastic or other modern industrial materials that do not fit precisely with the typical cliché of an ecovillage like Thoreau’s cabin in Walden Pond.

5. Discussion: searching a social transformation?

On the one hand, Spanish rural areas seem to be a suitable social lab for ecovillage projects. On the other hand, despite the boom that neo-ruralism has experienced in Spain with the economic crisis, the permanent population integrating all the ecovillages that are part of the Iberian Network of Ecovillages is placed around 10,000 people in an immense rural environment (less than 2,000 with the ecovillages represented in Figure ). The number of projects is considerable, but the overall population involved is symbolic, although in some cases, like Artiborain in the Pyrenees, or Valdepiélagos in Madrid, the population in ecovillages are a significant proportion at the local level.

Considering the variables studied, only two cases, Beneficio in Las Alpujarras (Granada) and Lakabe in Navarra, have clear interstitial strategies that include the different social emancipation strategies linked to the six studied variables, from free right to settle in the case of Beneficio, to a high degree of self-autonomy in basic needs, such as food or economic activities in the case of Lakabe. These two projects have in common to be long-lasting projects begun in the 1980s by different grass-roots initiatives linked to anarchist and hippy movements. In contrast, some recent ecovillages seem to be developing a project in which interstitial strategies or even radical anti-capitalist discourses on their project presentation are hard to find. In some cases, for instance, the decision to access energy or water through solar power or local resources, seems to be, rather a practical decision, than a political one.

The great paradox of the neo-rural movement involved in ecovillages is that the vast majority of inhabitants are urbanites who come precisely from this undesired urban world and without professional skills to work in agriculture, livestock, or handicrafts. In this sense, in many cases, professional recycling is a significant challenge for many newcomers, and many people fail to adapt to the new environment. The members’ description in the majority of ecovillage websites fits with this profile. To this must be added the particular context lived in Spain especially during the years 2011–2014, as it was explained in previous sections, which pushed thousands of families to seek in these projects a way out of the crisis (Carretero, Citation2013). Some mediating organizations such as Embrace the Earth received for years dozens of requests for information on settlements, as well as existing ecovillages. According to this association, it was more the desperation for a very precarious economic situation than the will to change the primary cause for these migrations (Larrañeta, Citation2016). In this sense, some ecovillage projects emerged or acted as a social shelter, rather than a social empowerment initiative. Some of them were formed or strengthened by people willing more to run away from the city, or directly excluded by the job market, rather than willing to begin a new life project in such a community, with an alternative political discourse linked to interstitial strategies.

In contrast, some other cases analyzed here are long-lasting ecovillage projects emerged before the crisis. Apart from the Beneficio and Lakabe case, there are some examples such as Valdepiélagos in Madrid, Matavenero in León, Arterra in Navarra, or Artiborain in the Pyrenees with decades of history, an active community, and a clear discourse linked to the need of an alternative to capitalism and the development of social emancipatory practices. However, in some cases, pragmatism has been imposed on any political objective of building “social alternatives.” The goal of creating more sustainable communities is undoubtedly their primary aspiration, but most of them give up on other structural issues such as land ownership, external or economic relations or the education system. Particularly in the question of property, although there is an explicit criticism of the concept of ownership in many ecovillages, given the legal insecurity of squatting, many projects begin with the purchase of a plot or a house. This is the main difference between the neo-rural movement and the squat movement, which is narrowly linked to anarchist ideas and more present in the cities.

It is perhaps in the field of the economic and social model, where there is more significant heterogeneity of ecovillages. Some of these projects share models inspired by political ecology, with a strong emphasis on equality and equity among members, respect for all sexual orientations as well as the animal world, but its economic model differs little from that of the business logic of any economic organization. Sometimes, rather than ecovillage, some projects seem to have as their main (but not unique) activity the offer of meditation or craftwork courses at unaffordable fees for many people, reinforcing the idea of the consideration of some neo-rural projects in ecovillages again, as elitist.

Focusing on another critical issue linked to the economic and social model, the external relationships in ecovillages, in many cases the relationships between “neo-rurals” and neighbors is tense by the lack of communication of all kinds. Some examples, like Sieso de Jaca, Navalquejigo, or Manzanera had some conflicts with the local population, for instance as a result of squatting of private properties.Footnote3 Although some ecovillages have been active for decades, they are still being watched with suspicion by the local population, who do not understand their philosophy of life, since there are often too few attempts to communicate with local people, who often feel uncomfortable by new settlers with a different cultural background. An important study on the neo-rural movement in the Aragon region arrived at this conclusion after interviewing 23 “neo-rurals” in different villages, six of them admitted being in conflict with the local population (Ibargüen, Citation2004, pp. 36–38).This is the case for instance of Matavenero, a consolidated ecovillage project that nevertheless is hardly known by the local inhabitants of the surrounding villages:

The truth is that they are like a hippy commune. Its inhabitants are quite curious. I only went once from a hiking trail from San Facundo and stopped at the bar for drinks.

Interview 2: Local Inhabitant.

On the other hand, the suspicion is mutual, since many ecovillages have become a focus of alternative tourism and of curiosity from local inhabitants in other cases. Some ecovillage inhabitants usually complain of their loss of privacy, as every day new tourists from different countries come to visit the ecovillage:

“Most of the people who come here take us as fair monkeys, as a tourist attraction, sometimes touching the lack of respect and invasion of privacy. You are at your home and suddenly you are approached with the camera, and they take you pictures, without asking, as if you were a hippie vulgaris ‘‘.

Interview 3: Craftswoman in Matavenero.

This conflict needs to be studied with more detail in future contributions, but indeed is a crucial factor to explain the causes of the reduced number of existing active ecovillages in Spain, as well as the limited social impact in rural areas, even to doubt if some projects seek some social transformation, or rather some sort social isolation.

Finally, to understand the pragmatic will of many of these projects, it should be noted that the role of the State, both of the autonomous governments and of the central government and some local administrations, is apparently a disincentive to this way of life. The taxation they impose, the difficulty of obtaining individual building permits, or the often violent reaction when an ecovillage is installed on public land, are some examples. In some cases, the conflict between the state and some ecovillages scaled to the police occupation of the place, for example in the case of Fraguas, but at least three more cases had similar problems.Footnote4 This shows that the strategy of the transformation of the state can be described as ruptural concerning the movement of ecovillages, which is continually attacked because it is a movement that almost escapes its control, and that Wright’s coercion and institutional law mechanism operates here to limit and discourage ecovillage projects. It is even a cultural clash in the field of education, especially when second-generation ecovillage inhabitants attend high school and they find a completely different lifestyle:

I felt free in Matavenero, and when I went to the high school, I did not know less than the others. I just could not get used to having so many rules. I complained people did not take me seriously. I am 12, and I know already what I want to write or not… there are rules for everything!

Interview 4: Young resident of Matavenero.

To sum up, while it is true that the philosophy shared by almost all ecovillages fits perfectly into some of the interstitial strategies proposed by Wright (Citation2010), especially the development of alternative energy supply or food models, in practice the majority of communities identified as “ecovillages” in Spain, are much less radical than one might expect. Private property, conventional construction materials, or economic activities based on rural tourism, education and spiritual training for a considerable feeFootnote5 are some examples. Here lies one of the essential contradictions found in this study: the defense of some mechanisms that could be linked to interstitial and anticapitalist strategies, such as local and ecologic food production, use of renewable energy resources or bioconstruction techniques, seem to follow a green-washing narrative, in which the main aim, rather than a social empowerment alternative to spread and defend, is the development of a for-profit tourism or education business. It must be added to this, the role played by some ecovillages, rather as a social shelter to cope with austerity, than a voluntary life change for many unemployed youngsters.

In contrast, some other cases, more linked to anarchist, grass-roots, ecologist or feminist movements have shown that, despite technical difficulties, coercion by State, internal contradictions, and other problems, is possible to develop alternative life projects, linked to interstitial strategies, which cover almost all the basic needs. A minority of the ecovillages studied here, around eight or nine including Beneficio, Lakabe, Artiborain, Arterra, Matavenero, Manzanares, or Calafou or Sieso de Jaca, has succeeded so far in offering an alternative life-project almost autonomous and with exciting practices to provide basic needs beyond capitalist market logic, that could be inspiring for other neo-rural willing really to contribute to an emancipatory social transformation.

6. Final remarks

The ecovillage movement in Spain is a phenomenon thoroughly settled and that without a doubt is and will be lasting in time. With more than 120 projects, Spain is one of the countries in the world that has more projects of this type. Nevertheless, this contribution has tried to show, that ecovillages that fit with the traditional academic description of a group of neo-rural settlers trying to begin a social emancipatory project are quite a few because there is an enormous variety of projects that appear under the umbrella of the ecovillage concept.

In many cases, ecovillage projects imply a psychological and professional change of personal development for their members, usually coming from the urban world, and a conscious transition to a more sustainable, and even anticapitalist life model. Nevertheless, in many other cases, neo-rural associations develop ecovillage projects almost wholly disentangled from social transformation discourses. It would be more accurate to speak about a new entrepreneurship or implantation of a new business logic in the rural environment entirely framed in the paradigm of green capitalism. After the analysis performed on the six variables linked to ideology and material interests, following Wright’s theory, is interesting to note that only two cases seem to be developing alternative practices related to almost all basic needs, whereas six cases only formulate limited alternatives on food, water, and energy supply. In this sense, the sample analyzed in this study could be divided into two groups: a minority of radical cases, and the second group of mixed cases, in which for-profit activities, conventional strategies to cover basic needs, and a social function as a shelter against the crisis, play a crucial role.

In conceptual terms, the strengthening of interstitial strategies would require, first of all, a complex debate within the ecovillage communities and networks, such as the Global Ecovillage Network and Red Ibérica de Ecoaldeas, upon the disentanglement between ecovillages as social transformation projects, from other for-profit green capitalism projects. From a practical point of view, the strengthening of the interstitial strategies that many ecovillages defend in their philosophy of life, could find in rural popular culture a fundamental support. Many of these cultures are and have been historically cultures of resistance against the unifying and modernizing trends of capitalists’ Nation-States and have even sustained a community quite similar to degrowth principles. The vast majority of traditional agriculture activities are inherently ecological, the paradigm of the commons versus private property was much more present in rural societies than previously thought, and even systems of economic exchange based on barter were common until a few years ago. The study and incorporation of traditional rural culture in modern ecovillages could be the catalyst for the ecovillage phenomenon to be much more widespread in a rural environment, which desperately needs initiatives that contribute urgently to its revitalization, and for the interstitial strategies to be consolidated in many ways in more ecovillages.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Luis Del Romero Renau

Recartografías (remapping in Spanish) is a land stewardship nonprofit association and a research group at the University of Valencia.

We are, therefore, an action-research group based at the University of Valencia formed by researchers and professors from the field of geography, environmental science, environmental law and political science that make research on new territorial, urban practices and environmental from the point of view of ecological economics and political ecology.

Our research is divided into four different lines:

(a) Study of urban and spatial conflicts

(b) Study of the causes and dynamics of shrinking rural areas

(c) Study of alternative, participative, and inclusive spatial planning tools

(d) These three lines are studied from the perspective of political ecology

Luis Del Romero is one of the members of this research group, specialized in urban and rural conflicts, and is an Assistant Professor at the University of Valencia.

Notes

1. The seminar was organized from academics coming from different ecovillage projects, especially for young researchers and PhD students, with a general topic of “Trans-disciplinary research in art, science, and society.” Visit: http://dparq.upv.es/sin-categoria/jornada-practica-y-metodos-de-investigacion-transdisciplinaria-entre-arte-y-ciencia-recartografias-e-iniciativas-innovadoras-sostenibles.

2. Some Real estate agencies in Spain have included abandoned villages in their offer. Prices range from 50 or 60.000 euros for isolated houses, to 4 or 5 million euro for an entire village or a castle. Usually these properties need a full restoration project that can double the selling price. See: www.aldeasabandonadas.com.

3. Sieso de Jaca and Navalquejigo are long lasting squatting communities that have a long history of legal and social conflicts with traditional neighbors (El Faro, Citation2017; Puebla, Citation2015). The case of Manzanares in Soria even had an episode of physical aggression and harassment to some neo-rural activists (Claramunt, Citation2015).

4. Fraguas is an abandoned municipality within a public forest squatted in 2013 by a group of 12 “neo-rurals.” They were evicted by the police in spring 2017 and some of them accused of a “serious offense against spatial planning” in a hugely depopulated area which today belongs to the municipality of Monasterio (Guadalajara) with only 16 permanent inhabitants. They have been sentenced to 2 years in prison. Many other cases of ecovillages studied here had different legal problems with local and regional governments mainly, as El Calabacino, Sieso de Jaca or Matavenero, due to land use prohibition in protected areas, even if these projects develop in abandoned villages with no natural values.

5. Some of the ecovillages offer one or 2-day courses for 250–300 euros, while minimum wage in Spain for 2018 is 24 euros per day (SEPE, Citation2018).

References

- Accioly, M. D., Loureiro, C. F. B., Chevitarese, L., & Souza, C. M. E. (2017). The meaning and relevance of ecovillages for the construction of sustainable societal alternatives. Ambiente y Sociedade, 20(3), são paulo july/sept. 2017. doi:10.1590/1809-4422asoc0083v2032017

- Avelino, F., Dumitru, A., Longhurst, N., Wittmayer, J., Hielscher, S., Weaver, P., ... Strasser, T. (2015). Transitions towards new economies? A transformative social innovation perspective (Working Paper. TRANSIT working paper #3). Brighton.

- Cáceres-Feria, R., & Ruiz, E. (2017). Forasteros residentes y turismo de base local. Reflexiones desde Alájar (Andalucía, España). Gazeta de Antropología, 33(1), art. 06.

- Calvário, R. (2017). Food sovereignty and new peasantries: On re-peasantization and counter-hegemonic contestations in the Basque territory. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 44(2), 402–420. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1259219

- Calvário, R., & Kallis, G. (2017). Alternative food economies and transformative politics in times of crisis: Insights from the Basque Country and Greece. Antipode, 49(3), 597–616. doi:10.1111/anti.v49.3

- Carretero, R. (2013). La huida al mundo rural para escapar de la crisis: “En la ciudad no teníamos ni para comer.” In Huffington Post, 10th March 2018. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.es/2013/03/10/la-huida-al-mundo-rural-por-la-crisis_n_2817366.html

- Cattaneo, C., & Gavaldà, M. (2010). The experience of rurban squats in Collserola, Barcelona: What kind of degrowth? Journal of Cleaner Production, 18, 581–589. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.01.010

- Claramunt, B. A. (2015) AGresión en Manzanares, Soria. Portal libertario OACA. Retrieved from http://www.portaloaca.com/opinion/10634-agresion-en-manzanares-soria.html

- Cortes-Vazquez, J. A. (2014). A natural life: “neo-rurals” and the power of everyday practices in protected areas. Journal of Political Ecology, 21(1), 493–515. doi:10.2458/jpe.v21i1

- D'Alisa, G., Kallis, G., & De Maria, F. (2015). Decrecimiento, vocabulario para una nueva era. Barcelona: Icaria.

- Del Romero, L. (2018). Despoblación y abandono de la España rural. El imposible vencido. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch.

- El Faro del Guadarrama (2017, March 31). Un pueblo abandonado a sus suerte. El Faro. Retrieved from http://www.elfarodelguadarrama.com/noticia/48787/el-reportaje/navalquejigo:-un-pueblo-abandonado-a-su-suerte.html

- Fanjul, S. (2015, June 5). De vuelta al campo. EL País. https://elpais.com/elpais/2015/06/05/ciencia/1433506840_516130.html

- Fernández, O. (2013). Entre la evasión y la nostalgia. Estrategias de la neoruralidad desde la economía social. Gazeta de Antropología, 29(2), artículo 06.

- Folch, R. (2011). El movimiento neorrural en el Prepirineo de Lleida: El caso de la Terreta. In L. Díaz, O. Fernández, & P. Tomé ( coords.), Lugares, Tiempos, Memorias. La antropología Ibérica en el siglo XXI (pp. 2197–2206). León: Universidad de León.

- Global Ecovillage Network. (2016). What is an ecovillage? Retrieved from https://ecovillage.org/projects/what-is-an-ecovillage/

- Guirado, C. (2011). Tornant a la muntanya. Migració, ruralitat i canvi social al Pirineu Català. El cas del Pallars Sobirà ( PhD Thesis). Barcelona: Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Halfacree, K. (2007). Back-to-the-land in the twenty-first century – Making connections with rurality. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 98, 3–8. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2007.00371.x

- Hervieu, B., & Léger, D. (1979). Le retour à la nature, « au fond de la forêt…l’État ». Paris: Le Seuil.

- Hilmi, A., & Burbi, S. (2016). Peasant farming, a refuge in times of crises. Development, 59(3–4), 229–236. doi:10.1057/s41301-017-0109-6

- Hong, S., & Vicdan, H. (2016, January). Re-imagining the utopian: Transformation of a sustainable lifestyle in ecovillages. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 120–136. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.07.026

- Ibargüen, J. M. (2004): Neorrurales: Dificultades durante el proceso de asentamiento en el medio rural aragonés una visión a través de sus experiencias. In CEDDAR Informes, 2004-3 (p. 56).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2018). Padrón municipal de habitantes a 1 de enero de 2017. Retrieved from www.ine.es

- Kasper, D. V. S. (2008). Redefining community in the ecovillage. Human Ecology Review, 15(1), 13.

- Larrañeta, A. (2016). ¿A vivir al campo? Ahora más por deseo y con un proyecto de autoempleo que por necesidad. 20 Minutos. Retrieved from http://www.20minutos.es/noticia/2755406/0/vivir-campo-neorurales-despoblacion-espana/#xtor=AD-15&xts=467263

- Latouche, S. (2007). Le pari de la décroissance. Paris: Fayard.

- Laval, P., & Dardot, P. (2015). Común. Barcelona: Gedisa.

- Litfin, K. (2014). Ecovillages: Lessons for sustainable community (p. 224). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Marconi, V. (2015). Eco-villages in Catalonia: The rise of new green models in times of crisis. Catalan news. Agència Catalana de Notícies. Retreived from http://www.catalannews.com/life-style/item/eco-villages-in-catalonia-the-rise-of-new-green-models-in-times-of-crisis

- Menzies, H. (2014). Reclaiming the commons for the common good. Gabriola Island: New Society Publisher.

- Nogué, J. (1988). El fenómeno neorrural. Agricultura y sociedad, 47, 145–175.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pallarès-Blanch, M., Prados, M. J., & Tulla, A. F. (2014). Naturbanization and urban-rural dynamics in Spain: Case study of new rural landscapes in Andalusia and Catalonia. European Countryside, 2, 118–160. doi:10.2478/euco-2014-0008

- Pickerill, J. (2016). Eco-homes. People, place and politics. London: Zed books.

- Prados, M. J. (Ed.). (2009). Naturbanization. New identities and processes for rural-natural areas. Leiden: CPR Press.

- Puebla, P. (2015, November 6th). Los repobladores de Sieso de Jaca claman por que se les reconozca dónde viven. In El Heraldo de Aragón. Retrieved from https://www.heraldo.es/noticias/aragon/2015/11/05/los_repobladores_sieso_jaca_claman_por_que_les_reconozca_donde_viven_610303_300.html

- Resina, J. R., & Viestenz, W. (Ed.). (2012). The new ruralism: An epistemology of transformed space. Madrid: Iberoamericana/Vervuert.

- SEPE. (2018). Publicado en el BOE el salario mínimo interprofesional para 2018. Retrieved from http://www.sepe.es/contenidos/comunicacion/noticias/smi_2018.html

- Wilbur, A. (2013). Growing a radical ruralism: Back-to-the-land as practice and ideal. Geography Compass, 7, 149–160. doi:10.1111/gec3.12023

- Wright, E. (2010). Envisioning real utopias. New York, NY: Verso.

Annex

Table A1. Complete list of ecovillages with basic data

Interviews:

The primary open questions addressed in the interviews are:

Pros and cons of ecovillage living in Matavenero

How do you cover basic needs? Water and energy supply, food, housing, and job.

Social relationships within and outside the community

By express wish of some interviewees, in some cases its name is not included.

Minus, craftman, one of the first settlers in Matavenero

Man interviewed in Bembibre

Craftwoman, one of the first settlers in Matavenero

Elgar Carpenter, student, born in Matavenero.