Abstract

Eco-aesthetics offers cultural, socio-economic and environmental benefits for building sustainable green infrastructure systems. However, eco-aesthetics in urban green infrastructure is apparently inadequate in developing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), coupled with the high vulnerability of cities in the region to the impacts of climate change and environmental disasters. This creates fragile urban environments that undermine the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in SSA. The need to build more resilient cites in SSA with capabilities to survive and thrive amidst environmental problems is vital to ensure sustainable development. Literature review is used to explore the fundamental theories of eco-aesthetics and its possible contributions towards building resilient cities, with references to the case of a typical developing country in SSA, Ghana. Through discussions, this paper demonstrates how urban planning strategies directed towards eco-aesthetics will help cities, especially in SSA, achieve socio-ecological resilience and the SDGs. In order to successfully realise future proposals for eco-aesthetics in Ghana, three main factors likely to limit the implementation of eco-aesthetics are identified as financial, lack of awareness and land acquisition barriers. Recommendations for overcoming these barriers have been outlined to help promote eco-aesthetics and build socio-ecological resilient cities in Ghana and SSA in general.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper shows how a typical developing country in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) like Ghana is facing major climate change and environmental problems within its cities such as regular and fatal events of floods coupled with the gross pollution and degradation of the natural environment. However, urban green infrastructure (green spaces) which can help mitigate these environmental challenges are given little attention in urban development projects in Ghana and SSA in general. Eco-aesthetics as an emerging field seeks to enhance the way green spaces are designed, experienced and sustained by people especially within cities. This paper shows that, adopting the principles of eco-aesthetics in developing countries in SSA will provide sociocultural, economic and environmental benefits to society. The paper therefore concludes that, implementing eco-aesthetics will help create more resilient cities that can survive and thrive amidst these environmental challenges in Ghana and other developing countries in SSA.

1. Introduction

Global trends show that annual rural–urban migration has resulted in increased population of most towns and cities especially in developing countries of the world (Adams, Citation2009; ARUP, Citation2014; Jankevica, Citation2013). According to McIntyre, Herren, Wakhungu, and Watson (Citation2009), SSA has experienced the highest urban growth since the 1990s at an average rate of 3.5% per year. Major cities in SSA such as Lagos (Nigeria), Libreville (Gabon) and Accra (Ghana) are characterised by high rates of urbanisation which have resulted in upsurges of unplanned urban settlements (McIntyre et al., Citation2009). Ghana, a developing country in West Africa, is no exception to this occurrence as its urban population increased from 43.8% in 2000 to 50.9% in 2010 (Ghana Statistical Service—GSS, Citation2014). According Zigmunde (Citation2007) and Villaseñor, Tulloch, Driscoll, Gibbons, and Lindenmayer (Citation2017), high rate of urbanisation has been the number one cause of urban sprawl which results in decreasing valuable green spaces within and surrounding expanding cities. In Ghana, for instance, deforestation of surrounding urban forests, as well as, the depletion of existing green spaces within cities are some of the major environmental problems affecting urban ecosystems (Mariwah, Osei, & Amenyo-Xa, Citation2017; Potthoff, Citation2005). According to Agbesi (Citation2017), Ghana lost an estimated 2.51 million hectares (33.70%) of its forest cover between 1990 and 2010. Interestingly, during that same period, Ghanaians living in urbanised areas increased from about 5 million in 1990 to almost 14 million in 2010 (World Bank, Citation2015).

Additionally, many urban development projects in Ghana and SSA are also characterised by little or no proper attention to green infrastructure development, as well as the ecological and aesthetic components of urban landscape planning (Avenorgbo, Citation2008; McIntyre et al., Citation2009). The principles of eco-aesthetics are seemingly deficient in public parks and gardens in Ghana which have contributed to their unsustainability over the years. Many of the public parks created for social recreation in Ghana such as the Tema Children’s Park, Efua Sutherland Children’s Park in Accra and the Kumasi Children’s Park are in deteriorating physical conditions and have thus been abandoned by the public (Avenorgbo, Citation2008; Kquofi & Glover, Citation2015; Mensah, Citation2015). However, the cultural importance of public parks for social recreation, as well as their ecological benefits to the environment (biodiversity and micro-climate adaptation) cannot be overemphasised. Urban green infrastructure networks of parks, forestlands, gardens, green corridors and waterways also help enhance natural processes of air, water and temperature, reduce stress, and promote the mental well-being of urban residents (Molla, Citation2015; Tzoulas et al., Citation2007). Eco-aesthetics (Ecological aesthetics) as a concept promotes the planning of cities and communities in accordance with nature (green infrastructure) (Gobster, Citation2010; Marjo & Jeroen, Citation2010). The principles of eco-aesthetics also seek to reconnect urban residents to their natural environment by developing attractive green cities that promote environmental sustainability (Kovacs, LeRoy, Fischer, Lubarsky, & Burke, Citation2006).

Most importantly, the need to plan cities in accordance with nature or green infrastructure has risen in recent years due to the evident changes in global climatic patterns and growing occurrences of natural disasters affecting both developed and developing countries (Bruckner, Citation2012; McIntyre et al., Citation2009). According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (Citation2016), SSA is the most vulnerable region to the impacts of climate change and natural disasters such as floods and droughts which occur recurrently. Ghanaian cities, for example, have experienced several incidences of severe droughts, fire outbreak and floods in the past decade which have resulted in the loss of human lives and destruction of properties (Okyere, Yacouba, & Gilgenbach, Citation2012; Oppong, Citation2011). Since most natural disasters cannot be completely prevented, there is a global call to build more resilient cites with capabilities to survive and thrive amidst increasing environmental problems (Asian Development Bank, Citation2014). Like in most advanced countries of the world, building resilient cities in Ghana and SSA will help lessen the vulnerability of urban systems, infrastructure and people to the impacts of climate change and increasing environmental disasters.

While previous works on the benefits of eco-aesthetics have not been directly linked to building resilient cities, this paper contends that it presents opportunities for cities, especially in SSA to enhance their urban resilience through the use of sustainable green infrastructure networks based on the principles of eco-aesthetics. Again, going through existing literature, there is an apparent gap in Afrocentric perspectives on eco-aesthetics and thus, this paper attempts to help abridge this existing gap by exploring the potential contributions, as well as likely barriers to implementing eco-aesthetics in Ghana; a typical developing country in SSA. The main aim of this paper, therefore, is to explore the fundamental theories of eco-aesthetics as developed from the West, and demonstrate its potential contributions to building resilient cities in Ghana and other developing countries in SSA.

2. Research methodology

This paper uses literature review to analyse and discuss the key theories and principles of eco-aesthetics, as well as explores the possibility of building resilient cities through eco-aesthetics. Kitchenham (Citation2004), Victor (Citation2008) and Tuli (Citation2010) affirm that, literature review is a methodology in its own right with epistemological basis centred on interpretivist–constructivism rather than positivism. The interpretivist–constructivist approach of the literature review method is explorative in nature and relies on the strength of interpreting and constructing knowledge based on what is known and unknown (Tuli, Citation2010). The use of literature review as the method of data gathering is therefore appropriate for the exploratory nature of this paper which seeks to theoretically connect the contributions of eco-aesthetics to building resilient cities.

Three electronic databases; Google Scholar, ScienceDirect and JSTOR, were first searched to identify high impact journals in the areas of ecological planning, urban planning, landscape design, environmental aesthetics, green infrastructure and resilient city. The selection of research articles were from peer reviewed journals published between the years 2005 and 2017. Main journals used for the literature review included Landscape and Urban Planning; Cities; Ecology and Society; Landscape and Ecological Engineering; and Sustainable Cities and Society (see Table ). Keywords used for the literature search were structured to cover synonyms, broader terms and related terms to the research concepts in order to obtain wider search results (Table ).

Table 1. List of electronic database, keywords and journals used for literature review

Titles, abstracts and keywords of articles retrieved from the electronic databases were first assessed in order to identify the most relevant literature to the subject area before retrieval of full documents for further assessments. In all, about 200 abstracts we assessed and more than 60 full text articles deemed to be relevant were retrieved and used for this paper. The selection criteria for articles were restricted to cover the socio-cultural as well as aesthetic aspects of urban ecological planning, and thus excluded works that purely focused on the science of ecology (distribution, abundance and interrelationships of living organisms and their habitats). Again, since causal relationships between eco-aesthetics and building resilient cities have seemingly not been covered in previous works, the literature review included studies that somewhat focused on association of the two concepts rather than causation. The selection of literature therefore covered works that highlight the benefits or contributions of ecological planning to urban sustainability issues. Additionally, relevant book publications and online conference articles were also included in the literature review. Other online databases such as the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy were used to obtain philosophical papers on aesthetics and urban ecological planning. All online articles were accessed from August 2016 to October, 2017.

As cited in the introductory part of this paper (p. 3), cities in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are the most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and natural disasters (UNEP, Citation2016). The challenge is further aggravated due to the relatively poorer economies of countries in this region. Exploring new and innovative ways to promote urban resilience will be vital to ensure sustained development in SSA. This paper thus focuses on the case of a typical developing country in SSA; Ghana (see Table ), which exhibits most (if not all) the environmental challenges facing most countries in this region; from the impacts of climate change (droughts, floods, rising sea levels), to gross environmental degradation (pollution, illegal mining and deforestation). A search through academic discourses (textbooks, dissertations and curriculums) in the area of eco-aesthetics at the architecture departments in Ghana, as well as a World Wide Web (WWW) Internet search on the topic as pertains in Ghana yielded no relevant results thus far. Sources of literature were therefore mainly from Eurocentric perspectives which provided a basis to associate concepts to Ghana and other developing countries in SSA. Table provides a brief summary of the research aim, objectives and methods that guided the structure of this paper.

Table 2. Summary of research aim, objectives and methods

The following three (3) main sections present worldviews and theories on eco-aesthetics with an attempt to rationalise its potential contributions to building resilient cities in Ghana and SSA. The first section presents a brief theoretical overview of the fundamental concepts in the development of eco-aesthetics. The second section presents an overview of the concepts and principles of building resilient cities. The third section of this paper discusses the potential contributions of eco-aesthetics to building resilient cities while highlighting the likely barriers to its implementation within the Ghanaian urban space. The paper concludes by presenting a way forward for overcoming these barriers in Ghana in order to help build resilient cities through eco-aesthetics.

3. A theoretical overview of the development of eco-aesthetics

Eco-aesthetics is an interdisciplinary concept that integrates the key elements of aesthetics into the ecological makeup of human oriented environments (Gobster, Citation2010; Kovacs et al., Citation2006). Although intellectual research in eco-aesthetics mainly began with landscape ecologists in the early 1990s in USA, the main underlying theories that informed the ideology stems from a much longer history from four distinct sources: namely, natural science, philosophy, art or design and landscape perception (Gobster, Citation2010). Natural science is by far the main source of theories for the study of eco-aesthetics. Natural scientists such as botanists, biologists and landscape ecologists like Aldo Leopold, Adolf Murie and George Wright were some of the key researchers who contributed to the development of the concept (Kovacs et al., Citation2006). Philosophy provided the understanding of how the human mind perceives beauty (aesthetics) and how such aesthetics could be applied into landscape ecological studies. Art and design especially in the field of architecture helped integrate aesthetic elements such as order, rhythm and unity into landscape design to enhance ecological functions and promote sustainability (Spirn, Citation2011) Landscape perception as the final source of theories for eco-aesthetics, explored several psychophysical methods that helped better explain how people perceive their landscapes and environments (Carlson, Citation2016).

Eco-aesthetics is also closely related to the study of urban ecology. Urban ecology is an emerging field that studies how people and ecological processes coexist in human-dominated settlements (Marzluff et al., Citation2008). Ignatieva, Stewart, and Meurk (Citation2011) assert that:

new models of urban ecological networks should respect, conserve and enhance natural processes. They will improve biodiversity, aesthetics, and cultural identity and be an important framework for creating sustainable cities. (Ignatieva et al., Citation2011, p. 23)

The above quote offers a basis for outlining the four main keywords required to fully grasp the concept of eco-aesthetics: ecology (biodiversity), aesthetics, culture and sustainability. Ecology and aesthetics form the fundamental principles of eco-aesthetics (Spirn, Citation2011). Culture in relation to how people move, interact and perceive their environments also forms a major part of understanding eco-aesthetics (Kovacs et al., Citation2006). Moreover, the subject of sustainability is essential because creating urban landscapes is as complex as how they can be maintained or sustained by people over the long term (Adams, Citation2009). The following sections thus elucidate the essential roles and values of aesthetics, culture and sustainability to eco-aesthetics.

3.1. The value of aesthetics to landscape ecological planning

The question of how aesthetics affects our ecology in relation to how it connects people to their environment has been tackled from Eurocentric perspectives by authors such as Kovacs et al. (Citation2006), Gobster (Citation2010), Marjo and Jeroen (Citation2010) and Toadvine (Citation2010). The word “aesthetics” is a complex philosophical term that is used to imply the nature of beauty, art, taste and with the creation and appreciation of beauty (Oppong & Solomon-Ayeh, Citation2014). Philosophers such as Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and Eaton (Citation1998) in their writings help provide a reasonable understanding of the concepts of aesthetics, taste and beauty. Kant asserts that:

If he says that canary wine is agreeable he is quite content if someone else corrects his terms and reminds him to say instead: It is agreeable to me”… (because) … “Everyone has his own (sense of) taste”…(The case of ‘beauty’ is different from mere ‘agreeableness’ because) …”if he proclaims something to be beautiful, then he requires the same liking from others; he then judges not just for himself but for everyone, and speaks of beauty as if it were a property of things. (Kant & Pluhar, Citation1987, pp. 55–56)

Kant uses the metaphor of the wine taster as an example to explain the difference between taste and beauty (aesthetics). To Kant, taste differs from beauty because taste is subjective (individually-preferred), whereas beauty or aesthetics is a generally accepted attribute of things. Eaton (Citation1998), however, defined aesthetics as any object that seeks to arouse feelings of delight. Unlike Kant’s notion of beauty, Eaton further expanded the definition of aesthetics by emphasising that the term “aesthetic” remains constant whereas “aesthetic values or qualities” are relative to time and cultural factors (Eaton, Citation1998). In the field of architecture, first century (AD) Roman architect Vitruvius, in his “The Ten Books on Architecture” emphasised how any good architecture work should encompass the three elements of “firmitas” (firmness), “utilitas” (usefulness) and “venustas” (beauty or aesthetics) (Rowland & Howe, Citation1991). Venustas or aesthetics according to Vitruvius provides the added value of human pleasure and appreciation of any architectural building or landscape. That is why most works of architecture are generally perceived as a thing of good taste and successful when people perceive them to be beautiful (Oppong & Solomon-Ayeh, Citation2014).

Notably, to advocates of eco-aesthetics, green spaces need not only be perceived as a natural resource to be exploited or harvested, but rather, green areas are self-sufficient bodies that must be capable of being aesthetically admired (Marjo & Jeroen, Citation2010; Toadvine, Citation2010). Aesthetic elements, for example, have been applied successfully in the design of public green spaces in US and other parts of Europe (Kovacs et al., Citation2006). Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1857 plan for New York Central Park, is a classic example of how beauty or aesthetics were interpreted into landscape design for public appreciation and long-term sustainability (Gobster, Citation2010) (Figure ). Olmsted used unique water and green features interconnected with “organic” pathways to enhance both ecological and aesthetic values of the New York Central Park.

Aesthetic values of landscapes, however, are not always aligned with ecological values in some green spaces. According Jankevica (Citation2013), people generally perceive well-manicured and trimmed landscapes as attractive, whereas they perceive natural looking or bio-diverse landscapes as messy and unattractive. Subtle landscape forms such as treeless plains and wetlands, as well as ecologically valuable natural forestlands or wilderness may also be perceived as “scenically unattractive” (Jankevica, Citation2013; Panagopoulos, Citation2009). The concept of eco-aesthetics, however, does not promote the identification of beautiful landscapes, but rather it promotes the aesthetic appreciation of landscapes that provide ecological benefits to the environment (Gobster, Citation2010). Eco-aesthetics thus integrates aesthetic design elements such as unity, contrast, symmetry, order, etc., in landscape planning and design in order to help evoke human appreciation of ecological sensibilities (Kovacs et al., Citation2006).

3.2. The value of culture in eco-aesthetics

According to De Groot and Ramakrishna (Citation2006), culture or cultural preferences have always been linked to ecosystems. The nature of ecosystems and their conditions such as biodiversity, native species, climate conditions and natural processes have always influenced or directed human cultural systems around the world especially relating to issues of habitat design, religious practices, heritage values, and social interactions (Alfaro, Citation2015; Coopera, Bradyc, & Steend, Citation2016; Potthoff, Citation2005). Ecosystems are also capable of providing people with certain “cultural amenities” such as aesthetic appreciation, recreation, spiritual fulfilment, and intellectual development (Alfaro, Citation2015). In Ghana, for instance, certain cultural values or beliefs are attributed to some ecological landscapes such as sacred groves. Sacred groves like the Malshegu sacred grove near Tamale and the Buabeng-Fiema Monkey Sanctuary in Ghana are typical examples of how particular forests and native or endangered species believed to be sacred to the local inhabitants have resulted in the preservation of some natural landscapes in Ghana (Avenorgbo, Citation2008).

In relation to aesthetics, culture also affects the way a person or a group of people perceive beauty and this is related to Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus and taste (Bourdieu, Citation1990; Oppong & Solomon-Ayeh, Citation2014). How a particular group of people perceive their landscape to be attractive or not is always influenced by their acquired social and cultural experiences both individually and as a group (Potthoff, Citation2005). This explains why people from particular cultures such as in Europe or the Americas have specific aesthetic preferences and values that vary significantly from people in other cultures such as in Asia and Africa. The value of culture to eco-aesthetics is therefore highly relevant in the Ghanaian or African socio-cultural context where its people have diverse cultural preferences and values that affect the way they might accept, appreciate and protect their environment. Nonetheless, other research and theories in eco-aesthetics (Marjo & Jeroen, Citation2010) suggest that there are specific aesthetic preferences of landscapes generally desired by all people and across all cultural dynamics. These aesthetic preferences such as “presence of order”, “balance” and “elementary qualities” are referred to as “evolutionary aesthetics”, and are believed to be embedded in our human instincts developed during human evolution (Marjo & Jeroen, Citation2010).

The concept of “cultural ecology” therefore places emphasis on the relevance to cultural processes such as values, beliefs and social organisation in the design of human-oriented environments (Potthoff, Citation2005). Architects and landscape designers such as Ebenezer Howard (1850–1928), Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959), Philip Johnson (1906–2005), Ian Mcharg (1920–2001), Jane Jacobs (1916–2006) and Anne Whiston Spirn are all advocates for ecologically friendly urban environments that utilise aesthetics to help reconnect urban residents to nature. In order to successfully do so, cultural values need to be integrated into the design of human oriented settlements (Marjo & Jeroen, Citation2010). Nassauer (Citation1995) proposes the concept of “cues to care” where familiar cultural or native design elements should be integrated into the design of urban landscapes to help promote their sustainability over the long term.

3.3. Eco-aesthetics and environmental sustainability

The growing incidences of environmental problems such as urban pollution, natural disasters and depletion of green areas especially in SSA have prompted the need for more sustainable approaches to urban planning and design. According to Marjo and Jeroen (Citation2010), urban lands or cityscapes are the receptacles that hold all physical and cultural aspects of people, and thus, they need to be sustained for present use as well as preserved for future generations. Although aesthetics is not ontologically linked with general definitions of sustainability, Nassauer (Citation1995) suggests that aesthetics forms a significant part of realising “culturally sustainable” urban landscapes. The principles of eco-aesthetics promote the creation of ecologically responsive green spaces that are aesthetically pleasing to users or inhabitants in order to make them sustainable. The role of aesthetics or art in sustainability has been further emphasised by Lipton and Watts (Citation2004) who assert that:

Sustainable technologies appeal to our rationality, but…it is a small part of what makes us care about what we care about. To affect values, to create desire, to make people care about something, you have to affect people’s hearts, and bodies, our unconscious dream lives and our imaginations. This is the work art [aesthetics] can do so well. (Lipton & Watts, Citation2004, p. 156)

According to Marjo and Jeroen (Citation2010), adopting the principles of eco-aesthetics will help heighten the awareness and sensitivity levels of people’s interactions with their environment and their impacts on it. When people find their environment and natural surroundings attractive, they tend to appreciate it better, care for it and are more likely to sustain it for future generations (Marjo & Jeroen, Citation2010; Nassauer, Citation1995). In Ghana, for example, environmental issues of urban pollution and poor maintenance practices characterise many of its green spaces such as urban parks, green corridors and open spaces. The pollution of the environment in cities in Ghana consequently results in regular outbreaks of epidemics such as cholera and dysentery especially in the capital city of Accra (Eshun, Citation2017). Also, illegal small-scale mining activities in Ghana, Cote D’ivoire, Nigeria and South Africa are destroying several cultural sites and forest reserves in these countries (Avenorgbo, Citation2008). In Ghana, operations of illegal miners have left several acres of land in mining communities desolate and degraded, and polluted major water bodies such as the Pra, Birim and Densu Rivers in Ghana (Suleiman, Citation2015). These water bodies service major water treatment plants in the country that supply treated water to urban communities; hence, their pollution causes higher water treatment costs and a looming water delivery crisis to urban residents. Care and protection of the environments in Ghana are dangerously inadequate and pose a threat to public health and well-being which intend lessen the quality of life of the people. Other environmental challenges such as recurrent floods and droughts create fragile ecosystems and environments that will undermine the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Ghana. Urban environments in Ghana therefore require innovative urban development strategies directed towards building urban resilience. The following section thus explores the concepts and principles of a resilient city.

4. Resilient cities: Understanding concepts and principles

The concept of “resilient city” has in recent years become a major subject of academic discourses (ARUP, Citation2014; Benedict et al., Citation2001; Jha, Miner, & Stanton-Geddes, Citation2013; Spirn, Citation2011). Resilience as a term emanates from the Latin word resi-lire, which means to “spring back” and was first used in the field of ecology in the 1970s to refer to the ability of a system to maintain stability or recover functionally when exposed to disruption or disturbance (ARUP, Citation2014; Davoudi et al., Citation2012). A resilient system would therefore be one that can resist, absorb and recover from the effects of a disturbance or hazard promptly and efficiently (Jha et al., Citation2013). The concept of resilience is highly relevant to urban planning because the city represents a complex network of interconnected systems that require constant adaptations to changing conditions (Seeliger & Turok, Citation2013; Spirn, Citation2011). The Rockefeller Foundation (Citation2016) defines a resilient city as the capacity of people, systems and infrastructure within a city to survive, adapt, and grow in the midst of increasing “chronic stresses” and “acute shocks”. Chronic stresses are defined as persistent pressures that weaken the fabric of a city on a daily or cyclical basis such as high unemployment, inefficient public transportation systems and droughts (that cause food and water shortages). Acute shocks on the other hand, are sudden, sharp events that threaten a city such as earthquakes, floods, disease outbreaks or terrorist attacks (The Rockefeller Foundation, Citation2016).

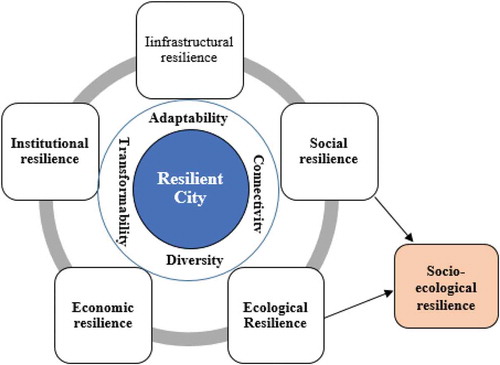

Assessing and improving a city’s resilience is a complex task, and the need to do so has produced researches that aim to classify urban resilience into sub-indicators or resilient components (Biggs, Schlüter, & Schoon, Citation2015; Cutter, Ash, & Emrich, Citation2014; Folke, Biggs, Norström, Reyers, & Rockström, Citation2016; Jha et al., Citation2013; Kotzee & Reyers, Citation2016; Villagra, Herrmann, Quintana, & Sepúlveda, Citation2017). Jha et al. (Citation2013) perhaps provides the foundation for classifying urban resilience into four main indicators: namely, infrastructural resilience, institutional resilience, economic resilience and social resilience. According to Jha et al. (Citation2013), infrastructural resilience is associated with lessening the vulnerability of critical urban facilities to hazards, whereas institutional resilience on the other hand relies on the protection and strengthening of governmental and non-governmental systems that manage an urban area. Economic resilience deals with improving a city’s economic diversity such as employment diversity, whereas social resilience relies on enhancing a community’s social capital and the community’s sense of place (Jha et al., Citation2013). Cutter et al. (Citation2014) and Kotzee and Reyers (Citation2016) promote a fifth component: “ecological resilience”, which assesses the state of ecological buffers, land-use diversity and ecosystem services as crucial indicators for improving the resilience of communities to natural disasters. Villagra et al. (Citation2017), however, make use of the terms “physical” and “environmental” resilience to, respectively, imply the same indicators of ‘infrastructural” and “ecological” resilience used in previous researches.

Resilience Alliance (Citation2010), Davoudi et al. (Citation2012), Biggs et al. (Citation2015), and Folke et al. (Citation2016) on the other hand emphasise the link between social and ecological systems in what is termed as “socio-ecological resilience”. The term socio-ecological resilience is used to imply the capacity to adapt or transform in the face of changing social-ecological systems, particularly unexpected change (natural disasters), in ways that continue to support human well-being (Davoudi et al., Citation2012; Folke et al., Citation2016). The use of the words “adapt” and “transform” in reference to socio-ecological resilience of cities are emphasised as important principles of resilient cities by Allan and Bryant (Citation2011), Biggs et al. (Citation2012) and Folke et al. (Citation2016). Hence, social, infrastructural, economic, institutional and ecological systems in cities are required to possess adaptive and transformative capabilities in order to make them resilient (see Figure ). “Adaptability” is defined as the capacity of a system to adjust to external and internal change through self-organisation and collective learning, whereas “transformability” (also referred to as “flexibility” by Leach, Citation2008) is the ability to evolve into new or innovative configurations when current conditions are deemed unsustainable (Allan & Bryant, Citation2011; Folke et al., Citation2016).

Figure 1. A diagrammatic representation combining the concepts and principles of a resilient city

In addition to adaptability and transformability principles of urban resilience, Leach (Citation2008) emphasises a “diversity” principle for building resilient cities. According to Davoudi et al. (Citation2012), diversity usually requires redundancy, but having multiple or alternative sources is assumed to provide more security of supply in the face of unexpected disturbances. Biggs et al. (Citation2012) however highlight a fourth principle for building resilient systems: “connectivity” which is defined as the manner and extent to which people, resources and wildlife disperse, migrate, or interact in socio-ecological systems (Figure ). Connectivity is an important principle because it prevents the fragmentation of urban systems by fostering links and channels where components of resilience can interact.

4.1. Assessing resilient cities: The Grosvenor research report

Several studies have attempted to assess the resilience of existing cities or communities based on one or more specified indicators or principles (Barkham et al., Citation2014; Chernick, Citation2005; Hofstad & Torfing, Citation2017; Jabaree, Citation2013; Kotzee and Reyers; Citation2016; Vale & Campanella, Citation2005). One such study, the Grosvenor research report conducted by Barkham et al. (Citation2014), assessed the resilience capacity of 60 cities (in advanced and developing countries) using verified datasets based on two indicators; “vulnerability” and “adaptive capacity”. Vulnerability was measured by assessing the impact of climate threats, environmental degradation, availability of resources, infrastructure and community cohesion, whereas adaptive capacity was measured based on strengths of disaster management systems, governmental/institutional systems and access to funding (Barkham et al., Citation2014). Assessing the resilience of varying economies in the world was a major strength of the study by Barkham et al. (Citation2014) as it provided opportunities for comparisons between cities with different socio-economic profiles. Three cities in Canada namely, Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary topped the list of most resilient cities based on the set indicators. The weakest 10 cities including Cairo, Dhaka and Mexico City were in developing counties with high urban population growth rates. These cities were revealed to be most vulnerable due to datasets that pointed out to poor infrastructure provision, inequality, environmental degradation and climate vulnerability. The adaptive capacities of these cities were also weak due to issues relating to poor disaster-risk management, unstable political economies and financial constraints (Barkham et al., Citation2014).

Toronto is ranked the most resilient city in the report because of the significant strides made over the years to help reduce the city’s vulnerability to disasters (flooding) and strengthen its adaptive capacity. Urban green infrastructure is used as a major adaptive strategy for improving socio-ecological resilience in Toronto according to the city’s Environment and Energy Division (Citation2017). Proactive adaptive measures used in Toronto include the planting of more trees in the city to help purify and cool the urban temperature; the installation of permeable surfaces (grass and shrubs) rather than asphalt to reduce storm water runoff; and the reliance on drought-resistant plants (Environment and Energy Division, Citation2017). The case is similar in Vancouver as green infrastructure feature prominently in the city’s “Greenest City 2020 Action Plan”, an ambition to make Vancouver the world’s most environmentally friendly by 2020 (Scruggs, Citation2017). Tyler (Citation2016) also affirms the importance of green infrastructure systems such as wetlands, green roofs and buffer zones in reducing the risk of cities to water hazards such as flooding, hurricanes, tsunamis.

While cities in advanced countries such as Toronto and Vancouver are being adapted for disaster risk management and climate change mitigation, cities in developing countries in SSA (e.g. Ghana, Uganda, Ethiopia, Nigeria, etc.) continue to be most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and natural disasters (McIntyre et al., Citation2009; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Citation2016). Ironically, strategies used by successive governments as resilience interventions in this region (examples are desilting choked drains and the demolishing of structures on waterways) have been reactionary rather than proactive in nature. It is therefore imperative for stakeholders in developing countries to adopt emerging measures that can help strengthen the adaptive capacity and lesson the vulnerability of their cities to climate change. This paper contends that, eco-aesthetics presents a fine opportunity for cities in SSA to enhance their urban resilience. Although this paper has provided a general overview of the various components and principles of building resilient cities thus far, the focus of this paper (which has an urban planning background) will be centred on how eco-aesthetics can be used to strengthen the socio-ecological resilience of cities in SSA.

5. Discussions: Possibilities of building socio-ecological resilient cites through eco-aesthetics with scenarios from Ghana

While the concept of eco-aesthetics seeks to enhance the ecological and aesthetic qualities of green infrastructure systems, it creates opportunities for building “socio-ecological” resilient cities that are capable of adapting to the changing global climate. As mentioned in the foregoing parts of this paper, developing countries in SSA like Ghana suffer the most impacts from acute shocks such as floods and epidemics, as well as, chronic stresses such as severe droughts (McIntyre et al., Citation2009). This paper proposes that the principles of eco-aesthetics (ecology, aesthetics, culture and sustainability) will help build socio-ecological resilient cities in Ghana and other developing countries in SSA.

Implementing an “eco-aesthetic” approach in urban planning in Ghana and other developing countries in SSA will imply creating new and enhancing existing urban green infrastructure systems that provide valuable “ecological”, “social” and “economic” benefits to cities and communities. These benefits derived from eco-aesthetics can be referred to as “ecosystem services” according to Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) (Citation2015). Ecosystem services are defined as the direct and indirect contributions of natural systems to the environment and human well-being (Matlock & Morgan, Citation2011; Pert et al., Citation2015). These ecosystem services are grouped into four (4) main categories in MEA report (2005) as provisioning (material or energy outputs from ecosystems); regulating (promote healthy environmental conditions); cultural (provide ecosystem value to people); and supporting services (provide habitat for biodiversity).

Currently, existing literature that directly link ecosystem services derived from eco-aesthetics to their roles in building resilient cities seems missing thus far. This paper, perhaps for the first time in academic discourses, attempts to aligns the key benefits of eco-aesthetics to their direct contributions to building socio-ecological resilient cities (see Table ). The respective ecosystem services to be provided to cities through eco-aesthetics have also been included in Table . This paper asserts that, an eco-aesthetic approach to urban planning in Ghana and in SSA will generate benefits from all four ecosystem services (regulatory, supporting, cultural and provisioning) (see Table ). This work however acknowledges that the listed contributions in Table are not exhaustive, but rather, they represent the fundamental contributions of eco-aesthetics to building socio-ecological resilient cities.

Table 3. Linking eco-aesthetic benefits to ecosystem services for building resilient cities

From Table , these ecosystem services (regulatory, cultural, supporting and provisioning) provided through eco-aesthetics will help strengthen the ecological and social resilience of cities in Ghana and SSA. This is because, eco-aesthetics promotes the development of green infrastructure systems that provide both ecological and social-cultural benefits to people and the environment. According to Fassbinder (Citation2016), green infrastructure is by far the cheapest way to mitigate some of the major problems facing cities today such as flooding, air pollution, rising temperatures and soil erosion without the additional energy demands. An increase of 10% green infrastructure in an area, for instance, could reduce local temperatures by up to 2°C (Mittermaier, Citation2017). The chlorophyll derived from plants can also absorb up to 30% fine particulate matter in an environment (Fassbinder, Citation2016). Other regulatory and supporting services such as managing storm water runoff and promoting biodiversity, for example, will lesson a city’s vulnerability to flooding, promote more adaptive environments and maintain genetic diversity (McDonald, Citation2017; Syarifi & Yamagata, Citation2014). Building flood resilient cities is highly relevant and timely in Ghana (and other African countries) due to recurrent floods that have hit major cities like Accra and Kumasi (Amoateng, Finlayson, Howard, & Wilson, Citation2017; Boakye, Citation2016).

Moreover, Vargas-Moreno, Meece, and Emperador (Citation2014) and Ni’mah and Lenon (Citation2017) argue that urban green infrastructure (parks, gardens and waterways) is an important adaptation strategy for emerging cities. Green open spaces create adaptation opportunities through the “nurturing of conditions for recovery and renewal” after a natural disturbance such as flooding (Desouza & Flanery, Citation2013; Ni’mah & Lenon, Citation2017). In addition to strengthening the adaptation capacity of cities, social and economic values of real estate and properties surrounding eco-aesthetic green spaces greatly improve (Jankevica, Citation2013; Molla, Citation2015; Young, Citation2006). Aesthetic values provided to people through eco-aesthetics also help ensure the sustainability of such projects over the long term, while cultural and provisioning services providedboost urban social resilience through the creation of “liveable cities” that provide alternative economic returns to urban dwellers.

Finally, global climatic changes and growing environmental problems led the United Nations’ member states in 2015 to pledge to achieve a set of SDGs to end poverty, fight inequality, and tackle climate change by 2030. This paper asserts that the benefits derived from eco-aesthetics outlined in Table will directly and indirectly help to realise 5 out of the 17 SDGs (Goals 3, 11, 13, 14, and 15) in Ghana and other developing countries in SSA. These five goals (good health and well-being; sustainable cities and communities; protect the planet; life below water; and life on earth) can be associated with building socio-ecological resilient cities, especially in relation to climate change adaptation and disaster-risk management. The socio-cultural benefits of eco-aesthetics listed in Table , for instance, will help countries in SSA achieve Goal 3 (good health and well-being) of the SDGs, whereas the ecological benefits of eco-aesthetics will help promote Goals 11, 13, 14, and 15 at the local and global scales. Building socio-ecological resilient cities in SSA will also help save the limited resources of developing countries that would have been used to tackle problems caused by climate change and natural disasters. Given the numerous benefits of eco-aesthetics outlined in this paper thus far, one might expect that cities in Ghana and SSA would adopt these principles in planning directives and future projects. Unfortunately, there exist barriers that may likely limit the implementation of eco-aesthetics in Ghana, and these barriers apparently cut across many developing countries in SSA and are discussed as follows.

5.1. Likely barriers to implementing eco-aesthetics in Ghana

This paper outlines three (3) main likely barriers that may limit cities in Ghana from fully realising future eco-aesthetic proposals: (1) financial constraints, (2) low level of awareness of eco-aesthetics and (3) restricting land tenure systems. The first barrier, perhaps the most obvious in a developing economy, is the inadequate or limited financial resources to support an eco-aesthetic urban planning strategy. Promoting an eco-aesthetic urban planning strategy would require the planting of more diverse plant species (trees, shrubs, flowers, grass, etc.), enhancing the ecosystem of urban waterways (rivers, lagoons, coastal areas, etc.), and the creation of eco-aesthetic public parks and green open spaces. These initiatives come at some costs of implementation, as well as, the additional costs of maintenance of these green infrastructure systems. To a developing country, this is a major challenge since scarce financial resources are overwhelmed by basic needs of a growing population that cover agricultural and economic needs.

However, existing literature reveals that the success or failure of government policies that aim at sustaining the socio-economic sectors is always dependent on the vulnerability of the environment. When the environment is vulnerable and less resilient, its affects public health, livelihoods and aggravates the poverty cycle (GEES, Citation2017). Also, the environmental/ecological benefits of eco-aesthetics do always produce economic advantages (Tyler, Citation2016). The London i-Tree Eco Report, for example, revealed that the city of London derives GBP 132.7 million (USD 161.5 million) annually in quantifiable ecosystem services such as pollution removal, carbon sequestration and storm water management from urban green infrastructure alone (Scruggs, Citation2017). Another study in California in USA also found out that, for every $1 spent on planting and maintenance of urban trees, $5.82 is generated from the benefits of urban trees (McDonald et al., Citation2017). Likewise, Guo and Correa (Citation2013) assert that, adopting green infrastructure as a flood mitigation strategy can save approximately $6.1 million annually in flood-prone communities in USA. Urban planning authorities therefore should not view financial limitations as absolute barriers to implementing eco-aesthetics, but rather they must view them as opportunities to invest in building socio-ecological resilient cities.

Another possible barrier to implementing eco-aesthetics in Ghana will be the apparent lack of public’s awareness of eco-aesthetics and its potential benefits to cities. This lack of awareness of the essential contributions of eco-aesthetics to green infrastructure is a key indicator as to why the concept appears missing in Ghanaian academic discourses as well as urban planning policies at the local and regional levels in Ghana. Interestingly, several studies conducted in the country have revealed that a high percentage of Ghanaians (over 80% of respondents in all cases) claim to be aware of climate change and its effects (Kunkyebe, Citation2015; Müller-Kuckelberg, Citation2012; Ohene-Asante, Citation2015). This seemingly high level of people’s awareness of climate change issues in Ghana is attributable to growing public education via radio stations that transmit in various local languages across the country (Kunkyebe, Citation2015). Conversely, careful searches through academic databases for studies on eco-aesthetics or urban green infrastructure as strategies for flood-risk management and climate change adaptation in Ghana appears non-existent thus far. The subject area also appears missing in existing curriculums of architecture and urban planning related courses in Ghana. This paper, as part of its goals, hopes to stir up research interests and discourses in the field of eco-aesthetics, particularly, its role in building socio-ecological resilient cities in Ghana and other developing countries in SSA.

The third possible barrier to implementing eco-aesthetics especially at the large-scale level would be land acquisition problems associated with the existing land tenure system in Ghana. The existing system involves customary, statutory (constitutional provisions and judicial decisions), and sometimes religious processes. About 80% of land ownership remains largely in the hands of customary authorities and private individuals in Ghana, with a limited state ownership (public land) of about 20% (Narh, Lambini, Sabbi, Pham, & Nguyen, Citation2016). Land acquisition process is usually characterised by lengthy, cumbersome and expensive procedures (Asumadu, Citation2003) that may create difficulties for potential investors to acquire large parcels of land for large scale projects such as ecological parks. Potential investors may also encounter problems of land litigation over the legal right of acquired lands due to the prevalence of some customary owners reselling land to multiple buyers. Despite numerous attempts by successive governments to reform Ghana’s land tenure system (an example: the Lands Commission Act 767 in 2008), land ownership and acquisition still remains a highly contested resource (Narh et al., Citation2016). In the concluding section of this paper therefore, we present possible ways to overcoming these barriers to implementing eco-aesthetics in Ghana.

6. Conclusion: The way forward

The purpose of this paper was to explore how eco-aesthetics can promote urban green infrastructure development and help build resilient cities in Ghana and other developing countries in SSA. Through a theoretical inquiry, this paper has demonstrated how the fields of aesthetics, culture and environmental sustainability have contributed to the development of eco-aesthetics largely in the advanced world. Also, based on existing literature, urban green infrastructure is being used as an adaptive strategy for climate change mitigation and flood-risk management in advanced cities in Canada and USA. Adding to the diverse discourse on urban resilience, this paper supports the use of green infrastructure as an effective urban adaptive strategy against the impacts of climate change. This paper however proposes an “eco-aesthetic” approach for planning urban green infrastructure systems that do not only provide essential ecosystem services, but enhance their aesthetic and cultural values to society as well. These aesthetic and cultural values are what will encourage the sustained human care of urban green infrastructure systems in the long term. In the foregoing section of this paper, three main barriers likely to limit the implementation of eco-aesthetics in urban planning in Ghana have been identified. Overcoming these barriers is thus vital to successfully implement the principles of eco-aesthetics in future urban development projects in Ghana and SSA in general.

To help overcome the barrier of limited financial resources to support eco-aesthetic urban projects, the public sector could network with private investors (public–private partnerships) and other interested stakeholders (Non-Governmental Organisations and religious groups) to mobilise additional funding for such projects. In Ghana for instance, public stakeholder agencies such as the Town and Country Planning Department (TCPD), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Parks and Gardens could partner with NGOs with a green mission as such the Friends of the Earth-Ghana, the Nature and Development Foundation (NDF), and Green Advocacy Ghana (GreenAd) to help raise funding from potential private or foreign investors, as well as corporate bodies. The public sector would however have to put in place some incentives to attract private and foreign investors into future eco-aesthetic urban projects. Additional funding opportunities could be generated when environmental laws such as the EPA Act 490 in Ghana are enforced and strict fines are collected from offenders of these laws. Accumulated collected fines could be used to support urban tree planting activities and regular maintenance activities for urban green spaces.

In relation to the barrier of lack of awareness, a national education and awareness campaign on the benefits of urban green infrastructure and eco-aesthetics will help reorient the public’s attention to their roles in building socio-ecological resilient cities, especially to residents living in most vulnerable cities. Both public and private stakeholders should take advantage of the proliferation of local radio stations to help educate the masses in Ghana. Public education should not only focus on the benefits of large-scale urban green infrastructure projects such as public parks, but also, the public should be sensitised on the role small backyard gardens could play in improving urban green coverage in cities. The importance of backyard gardens to urban green coverage is evident in the city of London where about 25% of the city's “urban forest” is reported to be located in residential gardens (Barkham, Citation2015). Again, public sensitisation of the benefits of eco-aesthetics should begin at the basic level of formal education (say, the benefits of urban trees), through to tertiary level programmes such as Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning. This will help educate future designers on the principles of eco-aesthetics, as well as help raise future generations of green-oriented citizens in Ghana.

Finally, to help overcome land acquisition barriers in Ghana, public authorities such as TCPD, Lands Commission and stakeholder NGOs should serve as mediators for land acquisition between potential private investors and customary land owners (chiefs and private individuals). These public authorities and NGOs possess a sense of credibility and respect, and will therefore smoothen the land acquisition process, as well as help alleviate the problems associated with land litigation. Customary authorities and landowners who are willing to lease (long-term) or sell out parcels of land to potential investors for large-scale eco-aesthetic projects should be compensated or honoured to encourage others to follow suite.

In conclusion, existing literature revealed an apparent gap in Afrocentric studies in the field of eco-aesthetics, as well as, its role in promoting urban resilience. This paper endeavoured to demonstrate how the benefits of eco-aesthetics will directly contribute to building socio-ecological resilient cities that are adaptive to the impacts of climate change and natural disasters. Adopting the principles of eco-aesthetics will produce ecological, social and economic benefits (ecosystem services) that will help lessen the vulnerability of cities in Ghana and SSA, as well as greatly enhance their appearance and sense of place of cities. Again, implementing the principles of eco-aesthetics in urban planning activities will be a step in the right direction to achieving Goals 3, 11, 13, 14 and 15 of the SDGs in developing countries in SSA. Since this paper is theoretical in nature, it serves as a teaser for future research direction to focus on empirical assessments of eco-aesthetics and its quantifiable contributions (ecological, social and economic) in varying cities in SSA. By so doing,this will help abridge the apparent research gap in Afrocentric viewpoints in the field of eco-aesthetics.

Acknowledgements

This paper is adapted from the literature review of an ongoing Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis project in Architectural Studies entitled: “An Inquiry into Eco-aesthetics for Urban Green Infrastructure Development in Ghana” at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ayisha Ida Haruna

Ayisha Ida Haruna is a PhD candidate of architecture at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Ghana, and beneficiary of Erasmus + scholarship at FRA-UAS in Germany. She also holds a Master of Architecture degree from KNUST and her research interests include architectural history and theory, and sustainable urban planning.

Rexford Assasie Oppong

Rexford Assasie Oppong is an architect and associate professor at KNUST (Ghana). He holds a PhD degree in architecture from Liverpool School of Architecture; and Masters in Urban Planning Management from the La Sapienza-University of Rome. His academic interests are in urban/rural settlement studies as well as architectural history and theory.

Alexander Boakye Marful

Alexander Boakye Marful is an architect and lecturer at KNUST (Ghana). He holds a doctorate degree in energy efficient city planning, and a Master of Infrastructure Planning degree from the University of Stuttgart, Germany. His research areas include fractal geometry, infrastructure planning, and resilient community design.

References

- Adams, W. M. (2009). Green development: Environment and sustainability in a developing world (Vol. 3). New York: Routlege.

- Agbesi, K. M. (2017, May 17). News: Galamsey menace––causes, effects and solutions. Retrieved October 2, 2017, from GhanaWeb: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Galamsey-menace-Causes-effects-and-solutions-538404

- Alfaro, R. W. (2015). Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Aesthetic Value of the State of Nebraska by Mapping Geo-Tagged Photographs from Social Media Data of Panoramio and Flickr (Community and Regional Planning Program: Student Projects and Theses). University of Nebraska, Lincoln.

- Allan, P., & Bryant, M. (2011). Resilience as a framework for urbanism and recovery. Journal of Landscape Architecture, 6(2), 43.

- Amoateng, P., Finlayson, C. M., Howard, J., & Wilson, B. (2017). A multi-faceted analysis of annual flood incidences in Kumasi, Ghana. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.09.044

- ARUP. (2014). City resilience framework: City resilience index. London: Author.

- Asian Development Bank. (2014). Urban climate change resilience: A synopsis. Manila: Author.

- Asumadu, K. (2003, May 11). Reform of Ghana’s land tenure system: An opportunity to enhance socio-economic development. Retrieved August 20, 2017, from GhanaWeb: https://mobile.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Reform-Of-Ghana-s-Land-Tenure-System-36246?channel=D1

- Avenorgbo, S. K. (2008, February). Aesthetic impact of Ghanaian socio-cultural practices on the environment and its protection in Ghana (A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) (African Art & Culture). Kumasi, Ghana.

- Barkham, P. (2015, August 15). Introducing ‘treeconomics’: How street trees can save our cities. Retrieved August 20, 2017, from the guardian Web site: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/aug/15/treeconomics-street-trees-cities-sheffield-itree

- Barkham, R., Brown, K., Parpa, C., Breen, C., Carver, S., & Hooton, C. (2014). Resilient cities: A Grosvenor research report. London. Retrieved October 2, 2017, from http://www.grosvenor.com/news-views-research/research/2014/resilient%20cities%20research%20report/

- Benedict, M. A., & McMahon, E. T. (2001). Green Infrastructure: Smart conservation for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Sprawl Watch Clearinghouse.

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Biggs, D., Bohensky, E. L., BurnSilver, S., Cundill, G., … West, P. C. (2012). Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. Annual Reviews Environment Resources, 37, 3.1–3.28.

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., & Schoon, M. L. (Eds.). (2015). Principles for building resilience: Sustaining ecosystem services in social-ecological systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316014240

- Boakye, P. (2016). These photos of the flooding in Accra will break your heart. Retrieved October 25, 2016, from OMGVoice: http://omgvoice.com/news/accra-floods-2016/

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. (R. Nice, Trans.) Stanford/California: Stanford University Press.

- Bruckner, M. (2012). Climate change vulnerability and the identification of least developed countries. CDP Background Paper No. 15.

- Carlson, A. (2016). Environmental aesthetics. The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved November 30, 2016, from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2016/entries/environmental-aesthetics

- Chernick, H. (2005). Resilient city: The economic impact of 9/11. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Coopera, N., Bradyc, E., & Steend, H. (2016). Aesthetic and spiritual values of ecosystems: Recognising the ontological and axiological plurality of cultural ecosystem ‘services’. Ecosystem Services, 21, 218–229.

- Cutter, S. L., Ash, K. D., & Emrich, C. T. (2014). The geographies of community disaster resilience. Glob Environment Chang, 29, 65–77.

- Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., … Davoudi, S. (2012). Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? “Reframing” resilience: Challenges for planning theory and practice interacting traps: Resilience assessment of a pasture management system in Northern Afghanistan Urban Resilience. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 299–333. doi:10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

- De Groot, R., & Ramakrishna, P. S. (2006). Cultural and Amenity Services. In Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Ed.), Ecosystems and human well-being: Current state and trends: Findings of the Condition and Trends working group (pp. 455–476). Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

- Desouza, K. C., & Flanery, T. H. (2013). Designing, planning, and managing resilient cities: A conceptual framework. Cities, 35, 89–99.

- Eaton, M. M. (1998). Locating the aesthtic. In C. Korsmeyer (Ed.), Aesthetics: The big questions (pp. 84–91). New Jersey, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Environment and Energy Division. (2017). Climate change adaptation: Towards a resilient city. Retrieved October 2, 2017, from City of Toronto Web site: https://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=78cfa84c9f6e1410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

- Eshun, A. F. (2017, May 9). Galamsey: An enemy of Ghana’s arable lands and water bodies. Retrieved October 2, 2017, from GhanaWeb: https://mobile.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/features/Galamsey-An-enemy-of-Ghana-s-arable-lands-and-water-bodies-536226

- Fassbinder, H. (2016). A biotope-city-quartier for Vienna. Biotope City Journal. Retrieved May 10, 2017, from http://www.biotope-city.net/article/biotope-city-quartier-vienna

- Folke, C., Biggs, R., Norström, A. V., Reyers, B., & Rockström, J. (2016). Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecology and Society, 21(3), 41.

- GEES (Grenotek Energy and Environmental Services). (2017, February 21). The true state of Ghana’s environment. Retrieved October 2, 2017, from https://grenotek.wordpress.com/2017/02/21/the-true-state-of-ghanas-environment/

- Ghana Statistical Service (GSS). (2014). 2010 population and housing census. Ghana: Kumasi Metropolitan. District Assemble report.

- Gobster, P. H. (2010). Development of ecological aesthetics in the west: A Landscape perception and assessment perspective. Academic Research, 4, 2–12.

- Guo, Q., & Correa, C. (2013). The impacts of green infrastructure on flood level reduction for the Raritan river: Modeling assessment. In C. L. Patterson, S. D. Struck, & D. J. Murray, Jr. (Eds.), World environmental and water resources congress 2013. Cincinnati, Ohio: American Society of Civil Engineers.

- Hofstad, H., & Torfing, J. (2017). Towards a climate-resilient city: Collaborative innovation for a ‘green shift’ in Oslo. In R. Alvarez Fernandez, S. Zubelzu, & R. Martinez (Eds.), Carbon Footprint and the Industrial Life Cycle (pp. 221–242). Cham, Bavania: Springer.

- Ignatieva, M., Stewart, G., & Meurk, C. (2011). Planning and design of ecological networks in urban areas. Landscape and Ecological Engineering, 7, 17–25.

- Jabaree, Y. (2013). Planning the resilient city: Concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities, 31, 220–229.

- Jankevica, M. (2013). Evaluation of landscape ecological aesthetics of green spaces in Latvian large cities. Science – Future of Lithuania, 5(3), 208–215. doi:10.3846/mla.2013.38

- Jha, A. K., Miner, T. W., & Stanton-Geddes, Z. (2013). Building urban resilience: Principles, tools, and practice. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

- Kant, I., & Pluhar, W. S. (1987). Immanuel Kant: Critique of judgment. Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing.

- Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Joint Technical Report.

- Kotzee, I., & Reyers, B. (2016). Piloting a social-ecological index for measuring flood resilience: A composite index approach. Ecological Indicators, 60, 45–53. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.06.018

- Kovacs, Z. I., LeRoy, C. J., Fischer, D. G., Lubarsky, S., & Burke, W. (2006). Aesthetics and ecology. Journal of Ecological Anthropology, 10, 61–65.

- Kquofi, S., & Glover, R. (2015). Interrelationships between natural and ‘artificial’ environments: A study of household aesthetics in Ghana. European Journal of Engineering and Technology, 3(7), 6–15.

- Kunkyebe, S. (2015). Local knowledge and response to deforestation and climate change phenomena among different livelihood groups. A dissertation submitted to the university of Ghana, Legon, in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of ma development studies degree. Retrieved August 20, 2017, from http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/handle/123456789/8476

- Leach, M. (2008). Re-framing resilience: A symposium report. Brighton: STEPS Centre.

- Leff, M. (2016). The sustainable urban forest: A step-by-step approach. Philadelphia: Davey Institute/USDA Forest Service.

- Lipton, A., & Watts, T. (2004). From signs to sculptural places; Ecoart: Ecological art. In H. Prigann, H. Strelow, & V. David (Eds.), Ecological aesthetics: Art in Eenvironmental Ddesign: Theory and practice (H. Prigann, Trans.). Basel/Berlin/Boston: Birkhäuser Publishers.

- Mariwah, S., Osei, K. N., & Amenyo-Xa, M. S. (2017). Urban land use/land cover changes in the Tema metropolitan area (1990–2010). GeoJournal, 82(2), 247–258.

- Marjo, L. V., & Jeroen, M. (2010). Sustainable city, appealing city. 46th ISOCARP Congress on “Sustainable city/developing world”. Nairobi: ISOCARP.

- Marzluff, J. M., Shulenberger, E., Endlicher, W., Alberti, M., Bradley, G., & Ryan, C. (ed.). (2008). Urban ecology – An international perspective on the interaction between humans and nature. New York: Springer.

- Matlock, M. D., & Morgan, R. A. (2011). Ecological engineering design: Restoring and conserving ecosystem services. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- McDonald, R. (2017). Urban trees: A smart investment in public health. Retrieved October 18, 2017, from 100 RESILIENT CITIES Web site: http://www.100resilientcities.org/urban-trees-a-smart-investment-public-health/

- McDonald, R., Aljabar, L., Aubuchon, C., Birnbaum, H. G., Chandler, C., Toomey, B., … Zeiper, M. (2017). Funding trees for health: An analysis of finance and policy actions to enable tree planting for public health. The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved from https://thought-leadership-production.s3.amazonaws.com/2017/09/19/15/24/13/b408e102-561f-4116-822c-2265b4fdc079/Trees4Health_FINAL.pdf

- McIntyre, B. D., Herren, H. R., Wakhungu, J., & Watson, R. T., & (editors). (2009). Agriculture at crossroad: Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) report. International assessment of agricultural knowledge, science and technology for development (IAASTD). Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Mensah, A. (2015, October 20). Ghana’s economy––Efua Sutherland children’s park: Drawing the parallels. Retrieved November 29, 2016, from LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ghanas-economy-efua-sutherland-childrens-park-drawing-mensah

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). (2015). Retrieved October 2, 2017, from https://www.millenniumassessment.org/en/index.html

- Mittermaier, P. (2017, August 21). To protect vulnerable populations, plant more trees. Retrieved October 2, 2017, from 100 Resilient Cities Web site: http://www.100resilientcities.org/protect-vulnerable-populations-plant-trees/

- Molla, M. B. (2015). The value of urban green infrastructure and its environmental response in urban ecosystem: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Sciences, 4(2), 89–101.

- Müller-Kuckelberg, K. (2012). Climate change and its impact on the livelihood of farmers and agricultural workers in Ghana. A Report for FES Ghana.

- Narh, P., Lambini, C. K., Sabbi, M., Pham, V. D., & Nguyen, T. T. (2016). Land sector reforms in Ghana, Kenya and Vietnam: A comparative analysis of their effectiveness. Land, 5(8). doi:10.3390/land5020008

- Nassauer, J. I. (1995). Messy ecosystems, orderly frames. Landscape Journal, 14(2), 161–170.

- Ni’mah, N. M., & Lenon, S. (2017). Urban greenspace for resilient city in the future: Case study of Yogyakarta City. 3rd International conference of planning in the era of uncertainty. 70. IOP Publishing. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/70/1/012058

- Ohene-Asante, N. S. (2015). Climate change awareness and risk perception in Ghana: A case study of communities around the muni-pomadze ramsar site. A thesis submitted to the university of Ghana, Legon in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of master of philosophy degree in climate change and sustainable development. Retrieved August 20, 2017, from http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh/handle/123456789/21146

- Okyere, C. Y., Yacouba, Y., & Gilgenbach, D. (2012, November). The problem of annual occurrence of floods in Accra: An integration of hydrological, economic and political perspectives. ZEF––Center for Development research; Interdisciplinary Term Paper. Bonn University.

- Oppong, B. K. (2011, October). Environmental Hazards in Ghanaian Cities: The incidence of Annual Floods along the Aboabo River in the Kumasi Metropolitan Area (KMA) of the Ashanti Region of Ghana (A Thesis submitted to the Department of Geography and Rural Development, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts). Faculty of Social Sciences; College of Art and Social Sciences, Kumasi, Ghana.

- Oppong, R. A., & Solomon-Ayeh, B. (2014). Theories of taste and beauty in architecture with some examples from Asante, Ghana. International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology, 4(4), 163–173.

- Panagopoulos, T. (2009). Linking forestry, sustainability and aesthetics. Ecological economics, 68(10), 2485–2489.

- Pert, P. L., Hill, R., Maclean, K., Dale, A., Rist, P., Schmideri, J., … Tawake, L. (2015). Mapping cultural ecosystem services with rainforest aboriginal peoples: Integrating biocultural diversity, governance and social variation. Ecosystem Services, 13, 41–56.

- Potthoff, K. (2005). Human Landscape Ecology (MNFEL 330/RFEL 3031). Selected Term Papers 2003/2004. NTNU-Trondheim, Department of Geography. Trondheim: Acta Geographica–Trondheim, Series A, Nr. 10..

- Resilience Alliance. (2010). Assessing resilience in social-ecological systems: A workbook for practitioners (Vol. 2). Resilience Alliance. Retrieved. August 20, 2016 http://www.resalliance.org/3871.php

- Rowland, D., & Howe, T. N. (1991). Vitruvius. Ten books on architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Scruggs, G. (2017, January 30). Urban forests increasingly central to planning in poor and rich countries alike. Retrieved August 20, 2017, from Citiscope Web site: http://citiscope.org/story/2017/urban-forests-increasingly-central-planning-poor-and-rich-countries-alike

- Seeliger, L., & Turok, I. (2013). Towards sustainable cities: Extending resilience with insights from vulnerability and transition theory. Sustainability, 5, 2108–2128. doi:10.3390/su5052108

- Spirn, A. W. (2011). Ecological urbanism: A framework for the design of resilient cities. In S. T. Pickett, M. L. Cadenasso, & B. P. McGrath (Eds.), Resilience in ecology and urban design: Linking theory and practice for sustainable cities. Dordrecht, Netherlands: SpringerScience + Business Media.

- Suleiman, M. (2015). The impact of mining in Ghana. Retrieved October 15, 2016, from http://www.graphic.com.gh/features/opinion/the-impact-of-mining-in-ghana.html

- Syarifi, A., & Yamagata, Y. (2014). Resilient urban planning: Major principles and criteria. Energy Procedia, 61, 1491–1495.

- The Rockefeller Foundation. (2016). 100 RESILIENT CITIES; What is urban resilience? Retrieved October 25, 2016, from http://www.100resilientcities.org/resilience#/-_/

- Toadvine, T. (2010). Ecological Aesthetics. In H. R. Sepp & L. Embree (Eds.), Handbook of phenomenological aesthetics (Vol. 59, pp. 85–91). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Science + Business Media.

- Tuli, F. (2010). The basis of distinction between qualitative and quantitative research in social science: Reflection on ontological, epistemological and methodological perspectives. Ethiopian Journal of Education and Science, 6(1), 97–108.

- Tyler, J. (2016). Sustainable hazard mitigation exploring the importance of green infrastructure in building disaster resilient communities. Consilience, 15, 134–145.

- Tzoulas, K., Korpela, K., Venn, S., Yli-Pelkonen, V., Ka´Zmiercza, A., Niemela, J., & James, P. (2007). Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using green infrastructure: A literature review. Landscape and Urban Planning, 81, 167–178.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2016). UNEP FRONTIERS 2016 REPORT: Emerging issues of environmental concern. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.

- Vale, L. J., & Campanella, T. J. (Eds.). (2005). The resilient city: How modern cities recover from disaster. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vargas-Moreno, J. C., Meece, B., & Emperador, S. (2014). A framework for using open green spaces for climate change adaptation and resilience in Barranquilla, Colombia. Proceedings of the resilient cities 2014 congress, 5th global forum on urban resilience and adaptation. Bonn, Germany.

- Victor, L. (2008). Systematic reviewing. United Kingdom: Social research UPDATE. Department of Sociology, University of Surrey. Retrieved November 30, 2016 http://www.soc.surrey.ac.uk/sru/

- Villagra, P., Herrmann, M. G., Quintana, C., & Sepúlveda, R. D. (2017). Community resilience to tsunamis along the Southeastern Pacific: A multivariate approach incorporating physical, environmental, and social indicators. Natural Hazards, 88(2), 1087–1111.

- Villaseñor, N. R., Tulloch, A. I., Driscoll, D. A., Gibbons, P., & Lindenmayer, D. B. (2017). Compact development minimizes the impacts of urban growth on native mammals. Journal of Applied Ecology, 54, 794–804. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12800

- World Bank. (2015). Rising through cities in Ghana: Ghana urbanization review overview report. Washington DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

- Young, G. (2006). Parks and Cities. Retrieved from Gerbera.org: http://www.gerbera.org/landscaping-magazine/landscape-sa-index/january-february-2006/parks-and-cities.

- Zigmunde, D. (2007). Evaluation criteria of protected landscape aesthetic quality. In Latvia University of Agriculture (Ed.), Research for Rural Development 2007: International scientific conference proceedings (pp. 196-203). Jelgava, Latvia: Drukatava Ltd.