Abstract

This paper deals with linguistic patterns influences in the formation of architectural forms. Of course, that in the creation of the architectural design, the process of becoming a mental image into a plan is in a semantic chain that always carries the cultural richness of the creator of the work. For this reason, it is necessary to consider the architectural context1 of the author’s cultural and social background. Linguistic patterns are one of the main branches of any culture that have a self-conscious role in shaping human thoughts and insight, but its written aspect sometimes appears unconscious, which is the result of a human interventionist mind. Unfortunately, this aspect of linguistic patterns has not been addressed in the study of architectural works yet. Accordingly, this study, with the help of a group of volunteer students from different nations, has focused on the effects of linguistic patterns on architectural works from the semiotics point of view, and since in the Arabic language the art of design is clear, the study of this language and the works of the Arab architect, “Zaha Hadid” has been selected. The result indicated that the influence of linguistic patterns is undeniable in her designs. On the other hand, the audience in this research was able to find a semantic relationship between linguistic and architectural works, which is the result of sociological and ideological analysis, which relates to the previous perceptions and teachings of the audience. According to the semiotic theory, there is a confession that what the reader infers and understands is important that the author of the work may not explicitly agree with it.

Public Interest Statement

This article focuses on cultural parameters, in particular linguistic patterns, and its impact on the formation of architectural forms. Language patterns are among the first trainings that humans face when they begin to learn in the early stages of. Human beings naturally (consciously and unconsciously) take advantage of this skill to communicate with others and express themselves externally. This study was designed to study this subject choosing a group of architecture students in a four-day workshop. The results indicated that an architectural form can, in its essence, represent a sign based on linguistic patterns that understanding its content requires a common cultural background.

1. Introduction

The sign is a basic element of communication that is received by one of the senses of mankind. For this reason, in the first place, it must be materialistic. Understanding the signs is done by connecting them with social conventions that are most often understood unconsciously (Chandler, Citation2007). On the other hand, the role of communication activities in directing the understanding of signs has always been effective. Based on this view, many theories in semiotic science have been developed that focus on the subject of research in content and meaning, which is more important than rational and functional-oriented criteria. “Rykwert” believed that the visual elements contain content and semantic features that cause the audience to react and this reaction would be directly related to his thoughts and attitudes (Chandler, Citation2007). He regards the relation between the sign and the signifier in texts as dependent on anthropology and sociology (Wigley, Citation2003) Therefore, to understand the visual elements, the study of the human nature is necessary and important.

The research has been carried out by participation of a number of volunteer students from different nations regarding how to understand the signs based on the linguistic patterns of architectural forms. The language patterns in the production of symbols and signs are clearly visible around us, but their impact on creating architectural forms has not been investigated so far. In this study, the Arabic language has been chosen due to its style and flexibility; therefore, a selection of works by the Zaha Hadid, which has been remarkably impressive in Deconstruction, Folding and Jumping Universe, has been chosen. Hadid buildings have fluid characteristics. They are flowing and flowing in nature, and no certain symbol is inferred from them. The perception and personal understanding of individuals to how to create these lines and to examine the influence of language was the focus of this study; but the significance of this study was evident when a number of students referred to religious symbols. In fact, the understanding of content from the context using language patterns led to religious symbols, which are signs. This was the result of intercourse of their subconscious mind with respect to previous education and their educational environment. Most importantly, they have tried to connect and link together with the works of the Arab architect, which has not been addressed so far.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the linguistic patterns in the examination of a text and to extract explicit and hidden interpretations of the text, including architectural texts, which, according to the results of this study, will have a solid position and could lead to extensive studies.

2. Methodology

Of the volunteers in this study, 75 students were selected from all undergraduate students (senior) in architecture and interior architecture. The participants were African, Asian, and European. All of the participants have passed basic architectural lessons, including aesthetics and architectural philosophy, which was very necessary for this study. Students’ selection from different nations (non-Arabs and Non-Muslims) seemed necessary to achieve unexpected concepts. All volunteers were able to analyse the architecture of Hadid, and they were fully acquainted with it. They were asked to draw up a conceptual sign, based on their perceptions and their cultural patterns or using linguistic and environmental patterns, so that their visual perception could be seen in other works by Hadid. The research was carried out in two stages, which the first step was the volunteers’ perception of from her works, which, after the end, the students reflected their personal and initial impressions. In the second stage, students who were successful in discovering linguistic patterns were asked to provide a general conclusion within three days of collective participation, based on discussing and reviewing different perspectives. The results of this study showed that every work of art, and in particular an architecture one, is a vein of hidden concepts that has been unconsciously embedded in it, which can be decoded individually and socially according to the viewpoint of the audience as well as the semantic power.

2.1. An overview of research background

Semiology as an independent science and theory was first introduced by Ferdinand de Saussure at the turn of the 19th century, but its roots can be traced back to the age of Plato and Augustine (Sojoodi, Citation2011). Saussure defines the sign as a physical subject that carries a meaning and is formed by the combination of a signifier (phonological image of the word) and a signified (conceptual image of the word) via a mutual relationship called signification. This relationship is not natural or compulsory, but rather completely conventional and arbitrary. In Saussure’s theory, there is no place for reference and it is completely removed from the equation. In other words, this theory argues that the key to perceive and understand a sign is its relation to other signs based on its structural relationship (Saussure, Citation1983) . Almost simultaneously with Saussure, the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce introduced his theory of signs (semiotics), which classifies the sign into three categories (Table ):

Table 1. Summary of Pierce’s semiotics (Larsen, Citation2005)

1- Icon

2- Index

3- Symbol

Peirce sees the sign as an essential part of human logic that translates the abstraction into a meaning . Pierce’s theory of signs is based on the following three elements:

1- Sign

2- Interpretant (the meaning received from the sign)

3- Object (to which reference is made) (Ahmadi, Citation1993).

In Pierce’s theory, the relation and interaction between these elements is called the semiotic process. This theory is focused not on the sign itself, but rather on the Semiotic. According to Pierce, the importance of a sign originates from the process by which it is produced and interpreted, and this is completely different from the dyadic model theorized by Saussure.

Peirce’s ideas and theory became popular in the 1960s, when semiology was still struggling to answer questions such as, what are the constituting elements of a semiotic system, where is the domain of this science, and how can it be extended to other areas? The subsequent attempts to answer these questions gave rise to a variety of theoretical works, which led to the development of the semiotics of communication and the semiotics of signification. The semiotics of communication is the study of the signs that are created in the domain of a communication and are perceived accordingly and is therefore strongly focused on human language. In contrast, the semiotics of signification assumes that any phenomenon that signifies anything falls within the domain of semiotics. As a result, the latter approach extends over a far larger domain of concepts. One of the notable theorists of the semiotics of signification is Roland Barthes**, who believes in the plurality of meaning in language. According to Barthes, perceivers can always discover more layers of meaning in any sign, and what they perceive varies with their perspective and the state of their society. One of the most important contributions of Barthes is the theorization of the concepts of denotation (direct relation between a signifier and a signified) and connotation (a sign that it self contains a signifier and a signified, and serves as a signifier for another signified) (Barthes, Citation1999) Another figure of great importance in this field is the Italian thinker Umberto Eco. Eco does not associate the semiotics of communication to meaning and signification, and instead believes that the process of communication is limited to the exchange of information between two systems. In other words, he believes that signification process begins right after communication is complete in order to read and interpret the purpose Citation(Eco, 1970/1997). In Eco’s view, the relation between the content and the expression is conventional and the content has a cultural dimension Citation(Eco, 1970/1997). It has been argued that there is a difference between the message source and its recipient in how they interpret the massage, which is because of their differences in education, worldview, social class, ideology, and experience. Thus, the message may not invoke the same meaning for the recipients, as they interpret the message from their own perspectives (Barthes, Citation1999). This theory can be easily applied to the world of art and architecture. In the seventies, Jacques Derrida, the well-known theorist of the School of Deconstruction, rejected the notion of the one-to-one correspondence relation between the signifier and signified. According to Derrida, a signifier does not exclusively refer to a certain signified, but rather to different signified that may vary depending on the audience’s perspective. As an example, he states the concept of freedom and the fact that it may have different meanings for different people. Using the deconstruction theory, he discusses the multiple interpretations of the text and suggests that the text is inherently ambiguous and may have many semantic variations. Thus, because of these syntactic and semantic ambiguities, it is impossible to draw an absolute and complete meaning from a text (Derrida, Citation1966). Derrida believes that one can never reach a final analysis and interpretation of a text, as it only shapes and manifests our interpretation of the world (Derrida, Citation1982).

The implications of semiotic science have influenced many sciences, including architecture. The arts and architecture scholars have come up with extensive studies to better understand the architectural concepts. “Grütter” and “Anthony Antoniades” can be mentioned among them. “Grütter” introduces the types of signs in two dimensions, and “Antoniades” refers to the meaning of metaphor in sign and different from the symbol.

According to the above definitions and the existing theories in the literature, the studies in the field of semiotics can be divided into three major categories:

Syntax: the study of the signs

Semantics: the study of the relationship between the signs and what they represent

Pragmatics: the study of the relationship between the audience and the semiotic structure Dabbagh, Citation2016).

The present study is focused on the pragmatics of architecture.

2.2. First day: reading the text by audience

This study was conducted on June 3rd at the University of The Karadeniz Technique University, Turkey, with the participation of 75 volunteers. In this study, four works by “Hadid” (2009–2012) were presented to the participants. Each of these works has been analysed by Hadid’s opponents and proponents, but there is no common ground between these works so far and just it has been mentioned that Hadid’s works are more deconstructed in term of time line.

Selected works in the order:

Avenues Mall Mosque, Kuwait, 2009

Glasgow Riverside Museum of Transport, Glasgow, UK, 2011

Heydar Aliyev Center, Baku, Azerbaijan, 2012

Pierresvives, Montpellier, France, 2012

And the students focused on these works for four hours. Full Internet access and references. Table – shows student inferences in confronting this research.

Table 2. Avenues Mall Mosque, Kuwait, 2009

Table 3. Glasgow Riverside Museum of Transport

Table 4. Heydar Aliyev Center, Baku, Azerbaijan, 2012

Table 5. Pierresvives, Montpellier, France, 2012

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Semiotics on the works of Hadid and linguistic patterns

In three days, the selected students analysed the project. The matching of samples with Arabic language patterns played an important role in the project. At the end of the third day, they came to a collaborative effort. Students tested their findings for the next two works by Hadid. The notes and results of the students testify to the fact that linguistic patterns can be involved in the formation of architectural forms; especially in the works of Hadid, the traces of calligraphy art and linguistic patterns can be clearly seen that was the purpose of the project. But understanding linguistic patterns requires common cultural education. Occasionally, understanding and expressing linguistic signs leads to induction in future referrals to the work that will be dealt with in a separate article. The results of this research are summarized as follows.

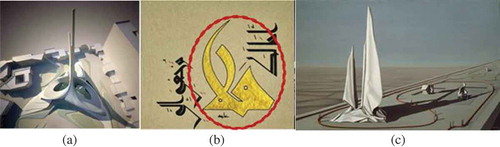

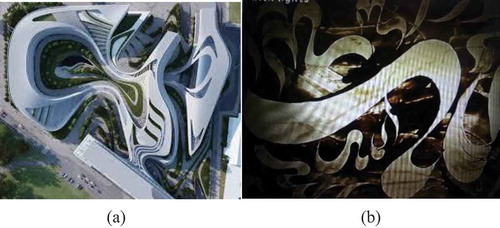

The first example is a mosque in Kuwait (Figure 1()) (Avenues Mosque | Zaha Hadid Architects - Arch2O.com Citationn.d.), which is known to evoke the works of the American Surrealist painter Kay Sage (1898–1963) (Figure ) (In the Third Sleep | The Art Institute of Chicago Citationn.d.), However, participants of this study saw this design as an architectural manifestation of calligraphy symbol known in Islamic culture to represent Ascension (Figure 1()) (Herati, Citation2004), which is a valid interpretation given the architectural form and context of the building.,

Figure 1. (a) The Avenues Mall Mosque (Avenues Mosque | Zaha Hadid Architects Arch2O.com Citationn.d.), (b) The Arabic calligraphy (Herati, Citation2004), (c) The “Kay Sage” painting (In the Third Sleep | The Art Institute of Chicago Citationn.d.)

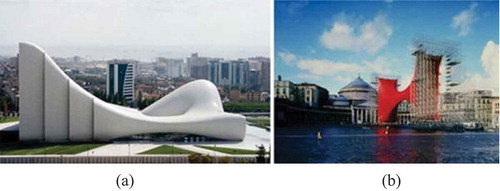

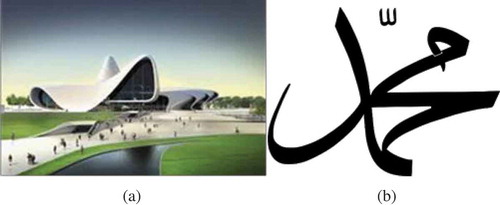

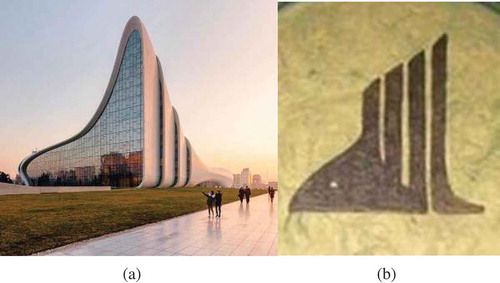

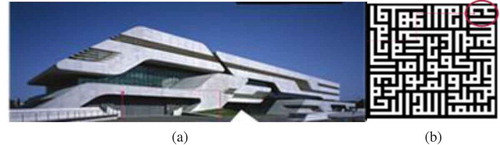

The second examined building was the Heydar Aliyev (Figure ) (Hufton + Crow | Projects | Heydar Aliyev Centre, Citation2014) Cultural Center. It has been suggested that this building is heavily influenced by Anish Kapur’s Taratantara installation (Figure ) (Anish Kapoor : Installing Taratantara, Citation1999). But the participants argued that the facade of this building evokes a calligraphy of the word Muhammad (Figure ) (Fazayelli, Citation1971) (the Prophet of Islam) from the front view (Figure ), (Singhal, Citation2011), and a calligraphy of the word Allah (Fiqure ) (Fazayelli, Citation1971), from the side view (Fiqure ) (Fotos de Centro Cultural Heydar Aliyev, Citationn.d.). Given the importance of these notions among Muslims, participants believed that this building possesses a significant degree of spirituality.

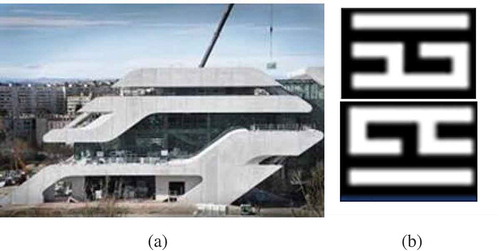

The same trend was also observed in the Glasgow Riverside Museum of Transport (Figure ) (RIVERSIDE MUSEUM, GLASGOW ‹Digital Facade Group, Citation2014). This museum has a Z-shaped plan with structural walls at both ends. These walls not only bear the ceiling, but also allow the glazed sidewalls to stand without any additional support. The participants again observed a degree of similarity between the roof plan and a calligraphy of the word Allah (Fiqure ) (Fazayelli, Citation1971), which is highly unlikely to be the designer’s intention given the museum’s purpose and cultural context and the roof’s general form, which gives room for a wide variety of interpretations.

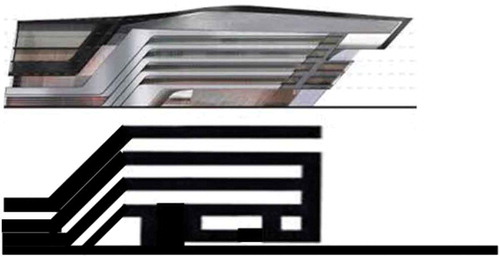

In the following, Zaha Hadid’s design for Beko Masterplan (Figure ) (Beko asterplan - Masterplans - Zaha Hadid Architects, Citation2012) is compared with another calligraphy of the word Allah (Figure ) (Jazayeri, Citation2013).

Figure 2. (a) The Heydar Aliyev Cultural Center (Hufton + Crow | Projects | Heydar Aliyev Centre, Citation2014), (b) The Taratantara. Anish Kapoor (Anish Kapoor: Installing Taratantara, Citation1999)

Figure 3. (a) The Heydar Aliyev. Front façade (Singhal, Citation2011), (b) The Arabic calligraphy of the word “Mohammed” (Fazayeli, Citation1971)

Figure 4. (a) The Heydar Aliyev. side façade (Fotosde Centro Cultural Heydar Aliyev, Citationn.d.), (b) The Arabic calligraphy of the word “Allah” (Fazayeli, Citation1971)

Figure 5. (a) The Riverside Museum (RIVERSIDE MUSEUM, GLASGOW ‹Digital Facade Group, Citation2014), (b) The calligraphy of the word “Allah” (Fazayeli, Citation1971)

Figure 6. (a) The Beko Masterplan (Beko asterplan - Masterplans - Zaha Hadid Architects, Citation2012), (b) The Arabic calligraphy of the word “Allah” (Jazayeri, Citation2013)

The exquisite curved lines shown in the above figure reveal the possible mental and cultural marks of designer’s origins in her work. This design has a sense of fluidity as well as unity, as if this integration originates from a single source manifested in the same body. In the figures below, the same trend can be seen in the front façade of the Pierresvives building (Figure ), which is designed by Hadid and the Library and Learning Centre of the Vienna University of Economics, which is designed by Cornelius Schlotthauer in collaboration with Hadid. (Figure ), ) (Hof, Citation2012) are similar to the Kufic Bannai script (Figure ), ) (Herati, Citation2004) that can be easily found in many decorations of Muslim religious buildings, and Library and Learning Centre, Vienna, (Figure ) (Zaha Hadid Architects · Library & Learning …. - Divisare, Citation2009) also seems to be partially inspired by the art of calligraphy.

Figure 7. (a) The Pierres Vives building. Perspective façade(Hof, Citation2012), (b) The Kufic script “Bannai” (Herati, Citation2004)

Figure 8. (a) The Pierres Vives building Side façade (Hof, Citation2012), (b) The Kufic script “Bannai” (Herati, Citation2004)

Figure 9. The Library and Learning Centre, Vienna Compared to Kufic Script (Zaha Hadid Architects, Library & Learning …. - Divisare, Citation2009)

The possible impact of Arabic calligraphy on these works of Zaha Hadid seems evident, and there are also many other examples that are not included in this study. Certainly, Hadid’s works do not propagate any ideological message, and the mentioned similarities are likely to be due to her cultural origins. A good response to the critics who describe Hadid’s works as fragmented and detached is perhaps to recommend further study of the art of Arabic calligraphy, because, from this perspective, there appears to be a coherence in Hadid’s works, which seems to be very symbolic.

The results of this study can underscore the importance of writing aspect of the linguistic patterns in designing lines.

3.2. Extension of the form content to signification and symbol

There are many interpretations of the term “form” in architecture. From the semiotic perspective, the form is a completely abstract concept referring to the relationship between the building’s visual aspects and dimensions and constitutes the basis for meaning-making. Each sign in the form can represent a system of meanings. In architecture, the form can be studied in two ways: analysis of the shape, and analysis of surface or plastic dimension. Shape analysis involves the study of the form’s main lines and geometry and more specifically the position and orientation of the components with respect to each other. The surface/plastic analysis is concentrated on surface properties like colour and texture, and the abstract relationship between the main constituents of the form, or in other words, the form’s expressive character. The expression of an architectural form is a function of its plastic manifestation, but in terms of content, the form is linked to the audience’s mindset and perspective. In terms of discourse and content, each form evokes the audience’s mental image of the world (discursive memory) and familiar places, cultures, and ethnicities in the context of the architectural space (Dabbagh, Citation2014). Upon observing the form, the mind of audience begins a process of figurativization followed by thematization. In fact, the attempt of the audience to find implicit meanings in the form is the result of this process. Thus, uniformity of these notions may contribute to better understanding of architectural forms (Leach, Citation2008)

From this brief description of the relationship between the constituents of form and content, it can be concluded that these two do not necessarily have a one-to-one correspondence relationship (Neumann, Citation1986). In other words, the architectural form and space act in tandem as a communication process so as to induce a communicative reaction in the audience.

When the audience sees an architectural work, the form and space will be randomly and arbitrarily classified in their unconsciousness, and then, for each observation, a meaning will be made based on their existing visual memory and subjective knowledge. In the present study, a group of architecture students was asked to act as the audience of the several works of the famous architect (Basirat, Citation2010) Zaha Hadid, the designs of whom is widely believed to be devoid of symbolism. The works of Zaha Hadid have a form of complexity, which originates from her trans-geographic and trans-temporal attitude towards language. Most of Hadid’s works have a tendency to escape from discourse language, that is, the general perception of meanings and signs that have an inner logic. In other words, her works can be viewed as material facts that cannot be completely described by language; the facts for which language lose its expression, figurativization, and thematization ability. The decoding and interpretation of Hadid’s works from this trans-language perspective could be very interesting. Zaha Hadid has given the title “queen of the curve” because of her mastery in using curved lines and avoiding right and repeated angles. Hadid’s method has been influenced by the art paradigms such as Suprematism and constructivism (Nicolai, Citation2006). In a New Yorker article, John Seabrook describes Hadid as one of the architects who are deeply influenced by the Kazimir Malevich’s abstract universe (Hadid has always acknowledged this a truth) ***. In a lecture on the Pritzker Architecture Prize, Hadid stated that abstraction opens the possibility of unfettered invention. When Seabrook asked her to explain this comment, Hadid said that abstraction show her how the lines should intersect and added “I wanted to capture a line, and the way a line changes and distorts when you try to follow it through a building, as it passes through regions of light and shadow”. Looking at this interview and Hadid’s cultural background, one may argue that Hadid’s power to use the curvatures or capture a line in the form could be partly due to her acquaintance with Arabic calligraphy***. Calligraphy is a form of line composition originated from the artist’s taste and creativity. One feature of calligraphy is the artist’s freedom in drawing the work; an illustration of lines that expresses the concept intended by its creator. Calligraphy is among the most important forms of Islamic and oriental art, and is known to be a few thousand years old.(Seabrook, Citation2009) Looking at the Arabic alphabet and words, one may see that how they may have had an impact on how Hadid designed the lines in her works. This effect can be better recognized in comparison with the works of other artists influenced by similar arts. These include the painters such as Franz Kline, whose abstract works have been influenced by the Chinese alphabets, the American painter Mark Tobey (1890–1976), who was one of the first abstract painters that consciously used the expression and structure of the Japanese alphabets to achieve intuitive expression in painting, or even Pierre Soulages, Hans Hartung, Adolph Gottlieb and Sam Francis, the abstractionist painters who created creative art by taking inspiration from the alphabets of the Far East (Panahi ghahar, Citation2013). In the world of architecture, many have used simple line forms for artistic creation of architectural forms. Examples include the works of Bjarke Ingels architecture group, most notably the w building in the Walter district, or the works of GRAFT International Architecture Group, which, for example, used the L-shaped forms in the design of a building in Sankt Augustin, Germany. Line-based signs can be found in the works of many artists, but Hadid has taken full advantage of this feature, and it could be the unfamiliarity of the Western audience with the oriental art that makes her architectural language appear detached. In contrast, the oriental audience view the Hadid’s works differently, which is because of their acquaintance with Arabic calligraphy.

4. Conclusion

It is clear that the written language is interpretable and meaningful according to the code that it carries. Indications of linguistic signs may, explicitly or implicitly, depending on the perceptual knowledge of the individual, which certainly transmits a kind of work and experience to the audience. Written language is a kind of discursive design, and a design can be very close to writing. However, the subjective perceptions of individuals in the context of a text are directly linked to previous teachings and their culture. Such studies in the concepts of linguistic patterns require the full knowledge of language and semantic systems, including the understanding of images and words that cannot be understood except by education or experience. On the one hand, in different societies different cultural interactions are practiced. In such a way that in this research, individuals are most likely to be affected by their ideological environment, which is clearly evident in Arab and Muslim societies. Of course, it should be noted that inspiration from culture has always existed in the creation of an effect, which in some cases the author of text (the architect) is sceptical of its original source, and he knows several other factors in its emergence more effective than the root.

This research attempted to illustrate the relationship between linguistic patterns and architectural forms; in addition, the efforts of the mind to achieve hidden layers in a text are illustrated. Making such an interpretation in a text underscores the importance of cultural science in semiotic science.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cengiz Tavşan

Cengiz Tavşan received the Ph.D. Degree in Architecture from University of (KTÜ), Turkey, in 2000. Since October 2010, he has been with the Department of Architecture, KTÜ, where he was an Assistant Professor, became an Associate Professor in 2013. Dr. Tavşan is a Fellow of the Turkish National Academy of Architecture. In 2016, Niloufar Akbarzadeh began working with Dr. Tavsan. They have begun a study on the impact of culture on the formation of architectural forms at KTÜ University, and, accordingly, plan and hold different workshops.

Notes

1. context: refers to architectural works.

References

- Ahmadi, B. (1993). Structure and text interpretation. Tehran: Markaz Entesharat (in Persian). (First published 1992). pp. 327. ISBN: 978-964-305-205-8

- Dabbagh, A. M. (2016). Architectural reading from the point of view of semiotics. 1735-9333. (Vol. 113, pp. 17–22). Tehran: Database (magiran) (in Persian), Hekmat & Marefat.

- Barthes, R. (1999). Elements Semiology. A. Levers, C. Smith, Hill, & Wang (ed.), (pp. 978–0374521462). New York, NY: Hill&Wang.

- Basirat, A. (2010). Zaha Hadid: The resurrection against the reality of conventional things and stockholm language syndromet. Fars-Marvdasht: Journal of Anthropology and Culture(in persian).

- Beko Masterplan - Masterplans - Zaha Hadid Architects. (2012). Retrieved from www.zaha-hadid.com/masterplans/beko-masterplan/

- Caroline, D. (2016). Queen of the curve’ Zaha Hadid dies aged 65 from heart attack. USA: Booth,Robert and Brown Mark,guardian.

- Chandler, D. (2007). Semiotics: The basics (2 ed.). London: Routledge ISBN-13: 978-0415363754

- Derrida, J. (1966). LA STRUCTURE, LE SIGNS ET LE JEU DANS LE DISCOURS DES SCIENCES HUMAINES, Conference prononcee au Colloque international de I’Universite’ Johns Hopkins Baltomore) sur Les Langages critiques et les sciences de I’homme (pp. 1966). Paris: Johns Hopkins University.

- Derrida, J. (1982). Margins of philosophy. [trans.] Bass.Alan. USA: University of Chicago Press(second edition). 978–0226143262.

- Eco, U. (1979/1997). Function and sign: The semiotics of architecture in rethinking architecture: A reader in cultural theory. (N. Leach, ed.). London: Routlege. 978-0415128261

- Fazayelli, H. (1971). Atlas line. Esfehan: Mashal (in Persian).

- Fotos de Centro Cultural Heydar Aliyev. (n.d.). Retrieved from Minube: https://www.minube.com/fotos/rincon/3711636

- Ghaeminia, A. (2006). Semiotics and philosophy of language 1735-0743 Issue 27 (pp. 3 -24). Tehran: Mind magazine(in persian).

- Herati, M. M. (2004). Application of lines in graphic arts, line application (1st ed.). Tehran, Tehran: kamale honar(in persian). doi: ISBN 2004: 0-49-7254-964

- Hof, S. (2012, September). Pierres Vives / Zaha Hadid Architects | ArchDaily. Retrieved from https://www.archdaily.com/.../pierres-vives-zaha-hadid-archi.

- Hufton + Crow | Projects | Heydar Aliyev Centre. (2014). Retrieved from www.huftonandcrow.com/projects/.../heydar-aliyev-centre/

- In the Third Sleep | The Art Institute of Chicago (n.d.). Retrieved from www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/53237

- Jazayeri, M. (2013). Kofi's writings: World heritage. Tehran: Aban. doi: 978-600-6413-11-2

- Kapoor, A. (1999). Installing Taratantara. Retrieved from anishkapoor.com/324/installing-taratantara

- Larsen, S. E. (2005). Semiotics:TheEncyclopaediaof language and linguistics (978008–0448541). (K. Brown, ed.). Canada: Elsevier Science.

- Leach, N. (2008). Rethinking architecture a reader in cultural theory. New York: Routlege, 978–0415128261.

- Neumann, N. S. (1986). Semiotics of architectural ornament: A method of analysis, arch and comport. Architecture and Behavior, 3(1), 37-53.

- Nicolai, O. (2006, June 2). Zaha Hadid: A Diva for the digital age. New York, NY: New York Times.

- Panahi Ghahar, F. (2013). The impact of Chinese calligraphy on the painting of abstract expressionism (Vol. 47, pp. 126–147). Tehran: Quarterly Art.

- RIVERSIDE MUSEUM, GLASGOW ‹ Digital Facade Group (2014). Retrieved from www.digitalfacadegroup.com/?page_id=109

- Saussure, F. D. (1983). Course in general linguistics. R. Harris (ed.), (pp. 236). London: Bloomsbury.

- Seabrook, X. (2009, December 21). The abstractionist: Zaha Hadid’s unfettered invention. New York: New Yorker.

- Singhal, S. (2011, November). Heydar Aliyev cultural centre in Baku, Azerbaijan by Zaha Hadid. Retrieved from: https://www10.aeccafe.com/.../heydar-aliyev-cultural-centre

- Sojoodi, F. (2010). Applied semiotics. Tehran: ELM (in Persian). ISBN: 978-964-405-956-8

- Sojoodi, F. (2011). Semiotics: Theory and practice (2nd ed.). Tehran: Elm (in Persian). ISBN: 978-964-224-065-4.

- Wigley, M. (2003). Deconstructivist architecture in deconstruction,crotical concepts in library and cultural studies. J. Culler (Ed.), (Vol. III, pp. 367–385). London: Routlege.

- Zaha. (2009). ARIV Zaha Hadid Architects Library & Learning … - Divisare. Retrieved from https://divisare.com/…/83725-zaha-hadid-architects-library-

- Zaha. (n.d.). Retrieved from ARIV.Zaha Hadid Architects Library & Learning…. - Divisare. (2009). https://divisare.com/.../83725-zaha-hadid-architects-library-

Appendix 1

** Roland Barth was the leading figure in the study of semiotics and its relation to cultural concepts in the 1960’s. He was among the first theorists of visual semiotics. In his seminal book “The Rhetoric of the Image”, a TV advert was taken as an example and analysed from a semiotics perspective to illustrate the mechanism of implicit and explicit signification (Ghaeminia, Citation2006)

*** For example, many early works of Zaha Hadid were rooted in the ideas of Russian Suprematists and their abstract thinking. Hadid’s works were inspired by the mysticism movement, especially the paintings of the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich. This was clearly evident in her graduation project (1977), where she used abstractions and fragmentation inspired by the works of Malevich (Basirat, Citation2010). This method is based on the deconstruction of masses into their base geometry. The same method of fragmentation can also be found in calligraphy. The professional style of Hadid has changed every few years, but in most of her works, there remains a footprint of calligraphy. After hearing about the death of Hadid, the Stirling Prize-winning British architect Amanda Levete stated: “She was an inspiration” (Caroline, Citation2016). Her global impact was profound and her legacy will be felt for many years to come because she shifted the culture of architecture and the way that we experience buildings. When my son was very young, Zaha showed him how to write his name in Arabic. “It was the moment I realized the genesis of her remarkable architectural language” (Caroline, Citation2016).