Abstract

The topic of safe fish consumption among women is complex both in its audience (women who are or could become pregnant) and its message (it is important to eat fish for its many nutritional benefits but because mercury levels vary by species, it is important to make informed choices about which species to eat). These complexities have led to confusion and fish avoidance in this population. Ideal messages about fish consumption have been suggested in the literature, but a more nuanced approach to message delivery that addresses subtleties, such as style and format of information, is needed for women to optimally use the materials. To explore how to package and deliver messages that describe and promote safe fish consumption, we conducted focus groups among women in our target population. Findings were used to design a visually appealing brochure and interactive, mobile-responsive website with recipes and a format that echoes and links to Pinterest. By delivering complex messages using a mode (easily accessible), style (photo-centric) and format (interactive, with recipes similar to Pinterest) desired by women, we have created an opportunity for repeated exposure to appealing fish images and recipes. Ideally, such exposure also piques curiosity and encourages women to seek out more complex fish information and consume safe fish during pregnancy.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Fish has many important nutrients, especially for developing babies. However, women who are or could become pregnant often (mistakenly) avoid fish altogether because of concerns about mercury. Research has been done on the types of fish consumption messages that work best, but these messages do not realize their potential if women do not read them. The goal of our study was to carry out focus groups to understand how women want to receive fish consumption messages, and then to develop materials in the mode, style, and format these women requested. Women in our focus groups said they wanted fish consumption information available at their fingertips, and that they wanted photos and recipes, among other things. Based on this information, we developed a brochure and mobile-responsive website with appealing pictures, recipes, and a Pinterest-like format to promote fish consumption among women who are or could become pregnant.

1. Introduction

The topic of safe fish consumption among women is complex both in its audience—women who are or could become pregnant—and in its message—it is important to eat fish for its many nutritional benefits but because mercury levels vary by species, it is important to make informed choices about which species to eat. Because of concerns about mercury and lack of knowledge about which fish are safe, many women consume less fish during pregnancy than they did before pregnancy, or even avoid fish altogether while pregnant (Bloomingdale et al., Citation2010; Connelly, Lauber, Niederdeppe, & Knuth, Citation2014). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that women 16–45 years of age consume 3.7 ounces of fish per week, and pregnant women in the United States report eating 1.8 ounces per week (Lando, Fein, & Choinière, Citation2012; U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Citation2014). These quantities are much lower than both the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the joint FDA-U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) recommendations of 8–12 ounces per week for pregnant women (U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) & U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA), Citation2017; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Agriculture, Citation2015). This difference between recommended and actual fish consumption reveals a disconnect between available information about safe fish consumption and women’s choices about eating fish. The first step to bridge this gap is to learn more from women about their beliefs, behaviors, and desires surrounding this topic. Our work sought to better understand the mode, style, and format of fish consumption information delivery desired by our target population, and then to develop materials to promote safe fish consumption based on those desires.

Fish is beneficial in that it is an essential component of a healthy diet: low in saturated fat with high-quality protein and a broad vitamin and micronutrient profile (Institute of Medicine, Citation2007). In particular, fish is a good source of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), two fatty acids that play a significant role in cardiovascular health (Vannice & Rasmussen, Citation2014). Fish consumption before and during pregnancy is especially beneficial because DHA is an essential contributor to optimal fetal neurodevelopment (Koletzko, Cetin, & Brenna, Citation2007). The FDA and U.S. EPA describe fish and shellfish as important components of a healthy diet, especially for women and young children, but recommend that women who are or may become pregnant consume types of fish and shellfish that are lower in mercury, as the developing fetal brain is highly sensitive to this neurotoxin. In addition to these federal recommendations, all 50 states and some U.S. territories and tribal lands have guidelines for choosing low-mercury fish (FDA & U.S. EPA, Citation2017).

When asked why they avoid fish, women have given a variety of reasons. Semi-structured phone interviews revealed three key themes that prevent or discourage pregnant women in Australia from eating fish: external factors including cost, access, household fish consumption norms, and sustainability concerns related to country of origin; individual preferences including taste and odor of fish and nausea during pregnancy; and confidence in choosing and preparing fish (Lucas, Starling, McMahon, & Charlton, Citation2016). Many of these sentiments are echoed internationally as well: a literature review of fish and seafood consumer purchasing behavior found that the most important barriers to fish consumption were a sensory disliking of fish (i.e., taste, smell, and texture), perceived lack of convenience and self-efficacy in preparation, health concerns, and fish price and availability (Carlucci et al., Citation2015).

Because of these perceived barriers to fish consumption and the topic’s complexity, promotion of this topic for this population requires a nuanced approach (Bloomingdale et al., Citation2010; Connelly, Smith, Lauber, Niederdeppe, & Knuth, Citation2013). Messaging should be succinct, describe positive nutritional characteristics unique to fish, and use terminology such as “women who are or could become pregnant” rather than “women of child-bearing age” (Connelly et al., Citation2014, Citation2013). Other literature suggests that messaging should refer to safe consumption frequencies rather than portion sizes; incorporate visual images; be grouped into low, medium, and high mercury level categories; and clearly describe the population whom the recommendations are for (Tan, Ujihara, Kent, & Hendrickson, Citation2011).

While the messaging itself has been researched, source, style, format, and accessibility of this information are all subtleties that can affect if and how messaging is received. “…All else being equal, the more people who are reached with a message and the more frequently they hear it, the more likely they are to respond” (Hornik, Citation2002, p. 13). Exposure to public health messages has been identified as a “central issue” in designing public education programs (Hornik, Citation2002); even if messages are well-crafted, they are ineffective if packaged and delivered in a way that people do not notice or read (Cha et al., Citation2014).

To determine the best way to package and deliver fish consumption messages, we conducted focus groups among women who are or could become pregnant. Here, we present the findings of the focus groups and how they were used to inform a brochure and website design to optimally describe and promote safe fish consumption.

2. Methods

2.1. Focus groups

Focus group recruitment began by randomly selecting 900 eligible English-speaking women aged 18-40 years who are members of a large (>1.5 million members and 1 million patients nationwide) Midwestern insurer and medical group and live in the Minneapolis/St. Paul or Duluth metro areas of Minnesota. In order to be considered an eligible member, membership had to be current in the first quarter of 2015 with no more than a one-month break in eligibility. Six hundred eligible women from the Minneapolis/St. Paul metro area and 300 from the Duluth area were selected, with the expectation that a large number of women would be screened out.

Potentially eligible women were sent a letter that described the study, asked for their participation, and gave them the option to opt out before receiving a phone call. Following HealthPartners Institute's standard study recruitment procedures, recruitment calls were made by trained telephone interviewers at various times of day and days of the week. Individuals who were reached via phone were asked up to four screening questions to: (a) gauge their ability and willingness to articulate responses in a group discussion setting, (b) determine if they avoid fish for religious or medical reasons, (c) determine if the individual is a vegan or vegetarian who avoids fish, and (d) ascertain likelihood of their having children in the future. Those who met screening criteria were asked if they would like to participate in a future discussion about fish consumption. Individuals who agreed to participate signed a consent form before the focus groups began and received a $50 gift card for participating.

Focus groups were held at community locations not affiliated with religious or ideological beliefs, able to accommodate meals, and with free parking. The focus group script was iteratively developed and pilot-tested with a group of women similar to the target population. It included a series of seven questions for the women about (a) their patterns of and barriers to fish consumption, (b) where and how they would like to receive information about safe fish consumption, and (c) their opinions of the existing state fish consumption guidelines (see Appendix A for focus group questions). Focus groups were facilitated by a member of the study team with focus group facilitation experience. The focus groups were recorded and notes were taken by a study team member familiar with the project. A staff scientist from Minnesota Department of Health was also present. This person was careful not to interrupt the discussion or jeopardize the quality of the data, but rather spoke up at the end of the discussion to address any questions and to correct any potentially misleading comments. Given the important health implications of too little fish consumed or too much high-mercury fish consumed, it was important to the team that any misinformation was corrected after the focus group wrapped up. Additionally, either the principal investigator or the project manager or both sat in during some of the focus groups to observe the discussion. The protocol was approved by both HealthPartners' and Minnesota Department of Health's Institutional Review Boards.

2.2. Analysis

Focus group recordings were used to clarify and add details to notes taken during the focus groups. Responses were captured in affinity diagrams to tally frequency of identical or highly similar responses and combine contextual duplicates. A thematic analysis of the notes was then completed by the facilitator and note-taker, who grouped respondents’ answers into 14 key themes, 3 of which are presented in this article. Only positive responses (i.e., what respondents want rather than what they don’t want) where n > 1 are shown here. Findings from past research and existing literature were compiled and combined with our focus group results to design our final fish consumption materials. This article focuses on application of the focus group findings to the design of the materials. Though we touch on many of the focus group results, this article only presents the focus group findings that were used in the material design process.

3. Results

After, up to eight phone call attempts were made to the randomly identified sample of 900 women, 155 indicated interest. Forty women were screened out as a result of the screening questions: 2 individuals were not able to articulate thoughts well enough for a group discussion setting (as discerned by HealthPartners Institute phone interviewers), 3 individuals were vegan or vegetarian avoiding fish, and 35 individuals self-identified as unlikely to have children in the future. An additional 4 individuals did not want to participate in the small group discussion, leaving 111 women. Of these, 63 were not able to attend the focus groups at the date and time they were offered, leaving 48 individuals. In total, 37 women were scheduled to attend one of seven focus groups in October and November 2015 and 24 ultimately participated. Five focus groups were held in Minneapolis/St. Paul; two groups had two attendees each, one had three attendees, one had four attendees, and one had five attendees. Two focus groups were held in Duluth; the focus groups here had five and three attendees, respectively. No further demographics beyond those required for focus group screening were collected as they were not considered germane to study goals.

Each focus group lasted approximately 70 min. First, As introductory questions, women were asked introductory questions about their patterns of and barriers to fish consumption. The majority of women reported eating fish one time per month, and salmon was the most preferred fish to eat. Barriers to fish consumption included a lack of knowledge in fish preparation, the perception that fish preparation is difficult and time-consuming, and that the smell, taste, or both, of fish is unappealing.

3.1. Preferred decision-making venue

When asked “Where are you when making a choice about what fish to eat or buy,” women reported making fish-related decisions in stores, restaurants, and at home. A few mentioned Pinterest specifically:

“I go to Pinterest. I get a lot of ideas from there before I go shopping.”

“I call myself a Pinhead because I am always on Pinterest. I get recipes. I like trying new stuff but I am not that brave when it comes to fish.”

3.2. Application of results: decision-making venue

Because women reported making fish consumption decisions in stores and restaurants and requested information that would be accessible virtually anywhere, in addition to our paper brochure we designed a mobile-responsive website. To bridge the gap between the paper brochure and website, we referenced the website in the brochure and also included an icon that encourages women to take and pin a photo of the brochure on Pinterest, as seen in Figure . Table expands on the ways we applied feedback on preferred decision-making venue to our brochure and website design.

Table 1. Preferred venue for making decisions about fish purchases: focus group responses and application of feedback

3.3. Preferred format of information and use of current guidelines

Regarding the preferred format of information about safe fish consumption, women most desired information on fish packaging, followed by recipes. Overall, they reported wanting recipes that are easily accessible—for instance on their phones via a QR code, website or an app. They also wanted stylistic elements such as pictures or charts:

“I would want to have that information when I am shopping. It would be cool to have a little picture or QR code that you could scan, something that I could think about when I am shopping.”

During focus groups, the facilitator distributed the current version of the state health department’s fish consumption guidelines and asked participants about their preferred use of the information in its current format. The most common response was that they would take a picture of the guidelines to access on their phone. Women also mentioned putting the guidelines on their refrigerator, sharing with others, putting the guidelines on Pinterest, and using them in the grocery store when shopping.

3.4. Application of results: preferred format and use of current guidelines

Because our focus group participants desired, among other things, appealing photos and recipes, we worked with a graphic designer and developed the brochure with enticing images similar to those seen on Pinterest. The back cover of the brochure also has a fish recipe as requested. Women reported that they would use the current guidelines brochure by taking a photo and saving it on their phone; to encourage this, we included the photo icon mentioned above (Figure ).

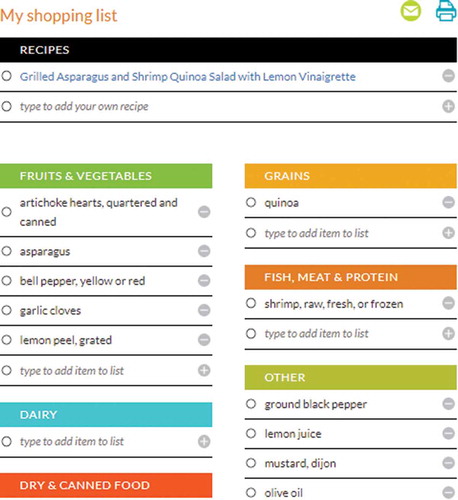

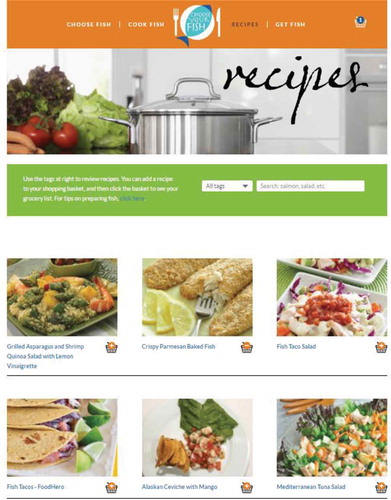

We applied these findings to the website by building the site (www.ChooseYourFish.org) to include a fish recipe page with a photo-centric format similar to Pinterest. Women reported wanting to share the existing fish consumption guidelines via Pinterest, so our recipe page has neatly arranged square pictures as seen in Figure , and all recipes have a link to “pin” the information directly to Pinterest. Because women revealed a desire for fish information with which they can interact, we incorporated some additional interactive design elements into our website. Users can interact with the site by toggling cells on a fish flavor and texture profile table, allowing them to select fish by taste, texture, mercury level and species, and to access recipes of fish with those desired qualities. Additionally, they can add fish recipes of interest to a shopping basket, which then produces a grocery list based on the recipe ingredients and can be edited, printed or emailed as desired (Figure ). Tables and show how our focus group participants’ desires regarding format and style of information and preferred use of existing guidelines (respectively) were applied to our brochure and website design.

Table 2. Preferred format for obtaining information about fish: focus group responses and application of feedback

Table 3. Preferred use of current state fish consumption guidelines: focus group responses and application of feedback

Figure 2. Layout of the ChooseYourFish.org recipe page, with a design and format similar to Pinterest. Photos are included in the website with permission from ChopChop; Food Hero, Oregon State University Extension Service; Spend Smart Eat Smart, Iowa State University Extension and Outreach; and What’s Cooking? USDA Mixing Bowl

4. Discussion

With messages derived from past studies (Connelly, Lauber, Niederdeppe, & Knuth, Citation2012; Connelly et al., Citation2013) and existing literature, we designed a brochure and a mobile-responsive website to promote safe fish consumption among our target population in the preferred design elements (easily accessible mode, photo-heavy style, and interactive format with recipes and a Pinterest-like feel) derived from our focus groups.

Mobile-friendly modes that are interactive and include recipes and visually appealing images desired by some focus group participants are consistent with past research on this population’s preferred methods of receiving health information (Fisher & Clayton, Citation2012; Hearn, Miller, & Fletcher, Citation2013). Together many of the desired design elements align with the style and format of Pinterest, which some of our respondents mentioned specifically by name.

Pinterest is a social network on which users can “pin” images to their own virtual bulletin boards and explore what other users have pinned. Other public health campaigns have successfully used Pinterest to promote their messages. MyPlate, a U.S. Department of Agriculture program about healthy eating, has social media presence on Pinterest, Facebook, and Twitter; of the three, their Pinterest account has the most followers, with 210,000 people currently following the MyPlate Recipes page (“MyPlate Recipes,”; Post, Eder, Maniscalco, Johnson-Bailey, & Bard, Citation2013). Additionally, the Oregon State University Extension Nutrition Education Program’s Food Hero project found Pinterest most useful for its simple and visual organization methods and as a way to direct users to their website (Tobey & Manore, Citation2014).

The highly visual and interactive nature of Pinterest makes it amenable to passive intake of a wide variety of new topics. In their study on motivational dimensions behind Pinterest, Mull and Lee conclude that “…[Pinterest] users are not exclusively visiting Pinterest to learn, but rather learning is a by-product of exploring the site in search of interesting ideas and images” (Mull & Lee, Citation2014). Because safe fish consumption is a complex topic with many perceived barriers to consumption, the concept should be introduced in a format women desire and at a time when they are open-minded and receptive to new ideas. Basic principles of health education program design include using multiple communication channels and encouraging natural social diffusion of messages (Hornik, Citation2002); in support of this principle, our materials allow emailing and sharing of information via social media. Given that food and drink is the No. 1 pinned category on Pinterest for women (Ottoni et al., Citation2013), Pinterest can increase women’s exposure to information about fish consumption via pictures and recipes and encourage them to try fish despite any previous fish aversions. Repeated exposure to appealing fish images combined with recipe ideas can increase curiosity and lead women to seek out fish guidelines and other more complex information; the learning is a secondary outcome but an outcome nonetheless.

Based on this concept, the current phase of our project aims to drive women to ChooseYourFish.org. Learning may happen, but it is not the outcome on which we are focusing at this time. Evaluation of the extent to which our materials resulted in learning and behavior change is planned for future stages of the project.

Our study had some limitations in that our focus groups were conducted with a limited number of participants, and our population was restricted to HealthPartners members living in confined geographic regions: one from a large metro area and another from a smaller city near communities with close cultural connections to fishing. This provided some variation in our sample that, although small, seems to have reached saturation. Though our population was restricted to two specific regions in the state, our sample was recruited randomly, albeit subject to recruitment bias. Our results cannot be generalized to a larger U.S. population, and one should use caution generalizing to women in Minnesota.

5. Summary and conclusions

The message of safe fish consumption among women who are or could become pregnant is complex both in terms of the audience and the message: eat fish for its many nutritional benefits but due to varying mercury levels it is important to make informed choices about which species to eat. This, together with the many barriers to fish consumption, calls for a nuanced approach to message delivery that takes into consideration the accessibility, style, and format of the information, as well as a person’s potential receptivity while receiving the information. Though research has been done on the types of health education messages that are ideal, well-crafted messages do not achieve their desired impact if the target population does not read them.

The current phase of this study, detailed in this article, was to design fish consumption education materials so that our population would read them, by gathering robust input from women who are or could become pregnant. To determine the optimal format and delivery method of these messages, we carried out focus groups among this population. Taking these findings into account and recognizing that they align with the style of Pinterest, we designed our brochure and website to echo the style of Pinterest while allowing for and promoting linkage to the site. This exposure can pique curiosity and encourage women to seek out more complex fish information with the ideal outcome being increased consumption of safe fish during pregnancy. The next phase will be an evaluation among subsets of this population to assess whether or not our materials had these intended effects.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and the Minnesota Department of Health for funding this project.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jennifer Renner

Jennifer Renner, MPH, is a Research Project Manager at HealthPartners Institute Survey Research Center in Bloomington, MN, with a background in public health nutrition and experience in program evaluation. In addition to leading the project management of the joint HealthPartners Institute/Minnesota Department of Health ChooseYourFish initiative, she manages a range of health-related research and evaluation projects, spanning care delivery to specific health conditions. This study, along with the others in her portfolio, gives her the opportunity to translate member and patient feedback into actionable data and desired deliverables that meet the needs of HealthPartners patients, members, and the general population.

References

- Bloomingdale, A., Guthrie, L. B., Price, S., Wright, R. O., Platek, D., Haines, J., & Oken, E. (2010). A qualitative study of fish consumption during pregnancy. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 92(5), 1234–1240. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2010.30070

- Carlucci, D., Nocella, G., De Devitiis, B., Viscecchia, R., Bimbo, F., & Nardone, G. (2015). Consumer purchasing behaviour towards fish and seafood products. Patterns and insights from a sample of international studies. Appetite, 84, 212–227. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.008

- Cha, E., Kim, K. H., Lerner, H. M., Dawkins, C. R., Bello, M. K., Umpierrez, G., & Dunbar, S. B. (2014). Health literacy, self-efficacy, food label use, and diet in young adults. American Journal of Health Behavior, 38(3), 331–339. doi:10.5993/AJHB.38.3.2

- Connelly, N. A., Lauber, T. B., Niederdeppe, J., & Knuth, B. A. (2012). Factors influencing fish consumption among licensed anglers living in the Great Lakes region. Ithaca, NY. Retrieved from http://www2.dnr.cornell.edu/hdru/pubs/fishpubs.html#risk

- Connelly, N. A., Lauber, T. B., Niederdeppe, J., & Knuth, B. A. (2014). How can more women of childbearing age be encouraged to follow fish consumption recommendations? Environmental Research, 135, 88–94. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.027

- Connelly, N. A., Smith, K. K., Lauber, T. B., Niederdeppe, J., & Knuth, B. A. (2013). Factors affecting fish consumption among new mothers living in Minnesota, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Ithaca, NY. Retrieved from http://www2.dnr.cornell.edu/hdru/pubs/fishpubs.html#risk

- Fisher, J., & Clayton, M. (2012). Who gives a tweet: Assessing patients’ interest in the use of social media for health care. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 9(2), 100–108. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6787.2012.00243

- Hearn, L., Miller, M., & Fletcher, A. (2013). Online healthy lifestyle support in the perinatal period: What do women want and do they use it? Australian Journal of Primary Health, 19(4), 313–318. doi:10.1071/PY13039

- Hornik, R. C. (2002). Public health communication: Evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Seafood choices: Balancing benefits and risks. Washington DC: The National Academies Press.

- Koletzko, B., Cetin, I., & Brenna, J. T., Perinatal Lipid Intake Working Group, Child Health Foundation, Diabetic Pregnancy Study Group, International Society for the Study of Fatty Acids and Lipids. (2007). Dietary fat intakes for pregnant and lactating women.British Journal of Nutrition, 98(05), 873–877. doi:10.1017/S0007114507764747

- Lando, A. M., Fein, S. B., & Choinière, C. J. (2012). Awareness of methylmercury in fish and fish consumption among pregnant and postpartum women and women of childbearing age in the United States. Environmental Research, 116, 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2012.04.002

- Lucas, C., Starling, P., McMahon, A., & Charlton, K. (2016). Erring on the side of caution: Pregnant women’s perceptions of consuming fish in a risk averse society. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 29(4), 418–426. doi:10.1111/jhn.12353

- Mull, I. R., & Lee, S. E. (2014). “PIN” pointing the motivational dimensions behind Pinterest. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 192–200. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.01.011

- MyPlate Recipes. Retrieved from https://www.pinterest.com/MyPlateRecipes/

- Ottoni, R., Pesce, J. P., Las Casas, D. B., Franciscani, G., Jr, Meira, W., Jr, Kumaraguru, P., & Almeida, V. (2013) Ladies first: Analyzing gender roles and behaviors in Pinterest. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Seventh International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Cambridge, MA.

- Post, R. C., Eder, J., Maniscalco, S., Johnson-Bailey, D., & Bard, S. (2013). MyPlate is now reaching more consumers through social media. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 113(6), 754–755. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2013.04.014

- Tan, M. L., Ujihara, A., Kent, L., & Hendrickson, I. (2011). Communicating fish consumption advisories in California: What works, what doesn’t. Risk Analysis, 31(7), 1095–1106. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2010.01559

- Tobey, L. N., & Manore, M. M. (2014). Social media and nutrition education: The food hero experience. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 46(2), 128–133. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2013.09.013

- U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2017) Eating fish: What pregnant women and parents should know. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/Food/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm393070.htm

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, & U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2015). 2015–2020 Dietary guidelines for Americans (8th ed.). Retrieved from https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2014) Quantitative assessment of the net effects on fetal neurodevelopment from eating commercial fish (as measured by IQ and also early age verbal development in children). Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodborneIllnessContaminants/Metals/ucm393211.htm

- Vannice, G., & Rasmussen, H. (2014). Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: Dietary fatty acids for healthy adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114(1), 136–153. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2013.11.001

Appendix A. Focus Group Questions

Describe a meal including fish that you typically eat with family or friends. If you do not eat fish, describe any typical meal. (Warm-up)

For those who don’t eat fish, what keeps from you eating fish?

For those who do eat fish, how often do you eat fish?

How do you choose what fish you eat?

(Probe) Do you choose by species of fish?

What, if anything, keeps you from eating fish more often?

(Probe) What might influence you to eat more fish?

(Possible probe) Please say more about (topic raised by participant)…

As a woman, how do you think about the risks and benefits of eating fish?

(Probe) For those of you who are mothers, how do you think about the risks and benefits of eating fish?

Where are you when making a choice about what fish to eat or buy?

What kind of information might help you make those choices? (note kind and format and what to do with the information)

How would you like this information available to you? (website, brochure, app)

Now that we have talked about what information you want, let’s turn to where you might like to get that information. Think about how you interact with the health care system.

From what point in the care process would you be interested in learning about resources for safe fish consumption (clinic visit, plan info, email through myChart, employer website, prenatal class, letter following cessation of birth control, after-visit summary, direct mail, PSA)?

Is there a person other than your primary care clinician who could provide that information to you?

Please look at this table

How clear is the information?

How likely are you to use this information to choose which fish to eat and how often?

What might make it more useful for you?

Any ideas of what to title this information?