Abstract

The legal order is not the biological system and cannot be self-sustained; we must rely mainly on officials who sustain it. The paper gives the basic descriptive elements of employee discretion and shows its modus operandi in public institutions. Employee discretion as the mixture of care, generalisation and legal protection is one of the legal state’s cornerstones and represents the constant source of order to sustain the latter’s structure and the quality of (each) government. With the understanding of behaviour of complex adaptive systems, employee discretion can be more fully described, while for its better prediction, digital-era governance is needed in connection with co-production. The paper gives through the elaboration of employee discretion the additional argument for the importance of co-production and based on that gives future paths also for legal science.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The first step towards efforts to standardize and transform the reason, emotions and courage of public employees into public benefits could be a simple recognition that others also have a point in their reasoning and that we do not have to defend our decisions regardless of the price. This recognition is a part of the presented concept of employee discretion as a person’s mental software that assembles means to achieve results. This “walking and thinking human calculator” is employee discretion (do not mistakenly understand it as administrative discretion) as the combination of reasonableness in determining proper criteria and impartiality in their implementation, which in public services both contribute to the overall quality of government. In complex matters, only variety can destroy variety, so a better understanding of employee discretion can be achieved through mutual interactions. This is known also as the co-production of public services.

1. Introduction

The social changes of the eightieth and nineteenth century were—as such changes always are—linked with objective circumstances and societies’ fundamental ideas. Descartes’s rationalism, Newton’s laws of motion and gravity and Laplace’s mechanics and determinism paved the way to the Age of Enlightenment in which Locke, Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau and Montesquieu developed the philosophical, political and legal ideas founded on order, reductionism, predictability and determinism, which reflected—with a high level of trust in the power of human reason—the mechanistic view on the world. Despite Descartes’s reductionist idea by which the nature of complex things can be reduced to the interactions of their parts as might be necessary for their adequate solution (Citation1974), a different path began already with Newton’s gravitational problem of three bodies (Citation1947). Although neither Poincare had solved this problem, a path had been made to chaos theory, to Planck’s quantum hypothesis, Einstein’s theory of relativity, Bohr’s quantum mechanics and the structure of atoms, Schrodinger’s complex molecule and the creation of wave mechanics, Heisenberg and uncertainty principle etc., all the way to the confirmation of the Higgs boson. These theories have changed our views: along determinism and rationalistic elements, there are ways, which unintentionally or unknowingly affect behaviour in different parts and particles. Causes and effects cannot be always directly linked or established, and a whole is more than a sum of its parts; the new, unexpected or emergent properties cannot be returned in previous states (irreversibility). Taking a system apart—and a human is also the complex adaptive system—does not reveal much about its processes because its élan is in relations among different parts.

If we agree with these scientific discoveries, how come we still have the predominantly deterministic, mechanical idea of law, even where the changing human elements come to the fore? Vivid changes in natural science should be reflected also in the liveable, responsive and flexible legal rules (these rules are still mainly apprehended in the legal science as the certain, unchangeable and rigid ones) but as such they would be in conflict with the rule of law, with the (more or less) strict rules that are paradoxically established for pro futuro unknown cases/situations. It turns out that these flexible characteristics are in the legal field, mostly present in a human being, i.e. in an implementer (because rules had been de iure already enacted, and their changes could be—in the absence of technological systems—spotted solely by humans). A valid enactment of rules could therefore mean very little for their implementation. In the latter part penetrate also the non-legal, informal, moral, emotional, psychological and other elements, due to the basic components of nature, human and their relations. A formal law should predispose along the basic deterministic, reductionist and rational elements (at the time of enactment) also the uncertainty, probability, unexpected creation of new rules and practices, their declines and rearrangements (at the time of implementation). People do not have only a tendency for order but also for liberty, for the freedom of complexity, interconnectedness and dependence from the actual or even potential events, conditions, relations and their combinations by which they co-create orders. But—if already an act of observation can confer shape and form reality which has proved the double-slit experiment (Feynman, Leighton, & Sands, Citation1965; Lanza & Berman, Citation2013)—what does this mean for the rule of law and its predictability? How can something be strictly legally prescribed provided that actions depend on a person, his thoughts and observations? These observations on human flexibility and context-sensitivity basically fit into Confucius teaching:

[i]f you try to guide the common people with coercive regulations and keep them in line with punishments, the common people will become evasive and will have no sense of shame. If, however, you guide them with Virtue, and keep them in line by means of ritual, the people will have a sense of shame and will rectify themselves. (Citation2003b, p. 8)

The examination of strict and formal legal instruments without knowing how they are de facto drafted, understood and implemented fails to capture the processes, interactions and practice by which countries’ public institutions are getting their things done. Things are perceived by humans according to their system of “censoring/filtering” messages, while their perceptions depend on their education, lifestyle, values and experiences.

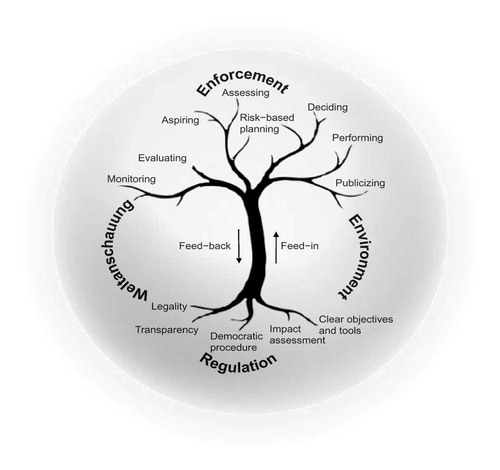

The paper’s goal is to frame and describe this human element by which—with a proposed model of cooperation—the quality of government (QoG) can be put on a higher level. To reach this goal, a focus will be at first on public employees who personally use public power for the implementation of rules (usually named as discretion). Although discretion is important per se, an attention will be given to employees’ personal elements. The employees’ personal and flexible characters and/or personalities will be named as “employee discretion” (ED) as the closest human element to the complex, adaptable and dynamic natural conditions. The paper introduces a new concept of ED as a pre-form of legal discretion, a personal Weltanschauung (used in the public administration) as the deliberately, logically and emotionally understood, fully formed, all-encompassing system of a personal vision of parts, their relations and systems, a personal combination of knowledge, skills and competencies that result in a public employee’s specific official outcomes. ED as the new element will enable easier differentiation among types of discretion and will provide a framework in which discretion is enacted. Based on these elements, the paper’s question is:

Is ED the precondition for the quality of government?

For a full presentation of the given question, the next section will present complexity in decision-making from which three kinds of discretion will be elaborated. One of them is ED that will serve for a better description of the QoG in Section 3. The law is what the man perceives it is; in democratic regimes, it is not about Hobbesian Leviathan or Machiavellian Prince, but about systems that should technically catch and transform data into a meaningful information and/or act in the most appropriate manner to connect the human’s perceptions vis-à-vis their expectations and goals. A possibility of such system is given in Section 4 where solutions are proposed for dealing with ED to be able to embrace all ideas in the conclusion. The paper presupposes that by acknowledging the existence of ED and by consequent training and education of civil servants, discretion as such can be better adapted to different contexts and situations—although when one addresses the unknown and flexible personalities, other ideas will probably emerge along the way.

2. Complexity in decision-making understood through practice

Complex is everything consisted from many interconnected parts, but there is more. Our choices reveal what we believe, each our (non)selection forms us through (absent) effects. What is perceived and later recognized as the (in)correct, and what defines a person as a human being, is not only a person’s choice but also his or her pre-chosen and arranged (also by others) system (a frame in which something emerges as a choice in the first place). Duty to act in accordance with the law is never absolute since it must be primarily perceived as such in a person’s mental system, which is on the other hand (re)assembled in a way that mentally, emotionally and physically configures and co-defines it. There is not only one “public interest”; its content contrasts in different practices that are understood by a human interpreter. Berkeley’s immaterialism (Citation2003) or “to be is to be perceived” principle, Sartre’s existentialism (Citation2001) in which we sense simply because we are (because an existence precedes its essence) and the double slit experiment (from quantum theory) that changes results simply by (not) looking it, show a reality in its core as the non-objective. If we paraphrase Kierkegaard’s sentence (Citation1997), “the law (and not only life) can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards”.

If we proceed on a regulatory field, it seems two basic regulatory ideas for good regulation are “if you want to accomplish your goals, you must have appropriate tools to do so”, and “if you want to determine your goals, you must have appropriate facts established with proper tools”. These, apparently right and intuitive ideas can be wrong because they fit into Newton’s second law of motion (Citation1947), as the classic example of a one-way cause–effect thinking. They disregard the mental, internal processes of living organisms (that are able to control aspects of their external environments) (Cziko, Citation2000) that always exceed written rules. This can be showed with the theory of complex adaptive systems, with the concept of emergence:

[a]n emergent property is a global behaviour or structure which appears through interactions of a collection of elements, with no global controller responsible for the behaviour or organization of these elements. The idea of emergence is that it is not reducible to the properties of the elements (Feltz, Crommelinck, & Goujon, Citation2006, p. 241)

All is not only more than the sum of its parts, but what is or could be “all” cannot be known in advance; it emerges irregularly through interaction. The traditional regulatory tools neglect a basic system’s predisposition of interconnections. What will emerge from regulations crucially depends on the interaction of all (legal, factual, personal, organisational, financial etc.) parts. A further characteristic of emergent property is its complex behaviour that emerges from simple rules (Gell-Mann, Citation2002). Rules can exhibit additional “regularities” (the case-law being a clear sign of this), and the former—written and understood in the classic way—cannot address a (more and more) complex environment. The question is how stability can be balanced with dynamism.Footnote1 Although people want the stable, clear and predictable public law, they also want for the same law to be appropriate for flexible and changing circumstances. If rules/regulators do not appropriately address changing contexts, situations will spontaneously—due to the very richness of interactions (Waldrop, Citation1993)—regulate themselves towards their equilibrium (Kauffman, Citation1996; Prigogine & Stengers, Citation1984). Very important for legal rules is to address and/or reflect basic characteristics of complex adaptive systems,Footnote2 and one “way out” for rules is to extrapolate patterns from known details, act on their generic substance and adapt towards new circumstances. The mere fact that we recognize complexity in other scientific areas, but very hardly in the legal science, points to additional elements, which are not taken into full legal consideration, although the law always addresses them—humans themselves.

And a human—without encroaching into his inner personality—can be known solely by his (in)actions. In this line or parallel to legal formalism is legal realism that examines the rule of law not only in its formal part but in its actual use (with this element, it is the closest to real complex adaptive systems). We could name it Ehrlich’s living law as ‘the law that dominates life itself even though it has not been posited in legal propositions’ (Citation2002, p. 493).Footnote3 For Bourdieu (Citation1986), legal formalisations can be understood solely in relation to practices; an existence of a rule does not imply that it is also respected since it interacts with habitus, which is by nature uncertain and vague.Footnote4 One solution to administer flexible environment is to study practices and habitus in institutions as the stable, valued, recurring patterns of behaviour (Huntington, Citation1968), and/or persistent rules that shape, limit, and channel human behaviour (Fukuyama, Citation2014). That complexity can be addressed/revealed solely through practice confirms also Wittgenstein’s language games (Citation1986),Footnote5 the cybernetic idea that the (real) purpose of the system is what it does (Beer, Citation2002) and at the very end even Confucius’s “effortless action” (wu-wei) that represents a perfect human harmony between one’s inner dispositions and external movements (Citation2003a). A crucial unity of knowledge and action, with the second being the natural unfolding of the first, should be reflected also in the law. The law is mainly what real-world experience shows it is.

So, what can be learned from complexity in decision-making? Given the ex-ante impossibility of knowable future effects, and ex-post emergent, unplanned properties, it is of crucial importance that all elements are detected as soon as possible (although their causes–effects are not known; within the frame of emergent properties, also accountability can get a whole new meaning). Every institution or norm being the product of human (who is the complex, adaptive system per se) lives, develops and goes through metamorphoses of its purpose, structure and action. Control can be constantly (re)acquired over new situations that emerge during a change of different conditions or appear during an implementation of rules solely through the permanent feedbacks, (re)organisations and (re)arrangements of elements. This can be done in two ways: by the elimination of changes and/or undesirable behaviour with the code-based or architecture-based techniques (Morgan & Yeung, Citation2007) that prevent undesired behaviours through “attractors” (e.g. civil forfeiture of criminal assets) or by public employees as the major part of governmental apparatus, who channel their and our opinions about what is similar or different, right or wrong, (ir)rational, (in)appropriate, (il)legal etc., to constantly accommodate public systems/rules. Since public employees are in the majority of cases also the ones who draft the above-mentioned attractors, the paper will be focused on them. They do their work according to their perceptions in the specific time and place, so it is of crucial importance to be acknowledged how and what they think. Discretion is a more complex problem than regulation (rights, duties, competencies), because flexibility is needed for solving more (and more) complex public matters, while both can be understood solely through practice. As the first can be applied on the second, the next sections will deal with discretion, its forms and its applicability to be able to better understand the ED, QoG and their relations and/or to present solutions by which ED can be more fully embraced and understood.

2.1. Administrative, political and ED

Despite the notorious word of discretion, there are difficulties in its clearer elaboration: “[t]he most problematic diversion (in terms of extending understanding of administrative leadership) … has been the normative debate about administrative discretion in which schools use extreme cases to make arguments rather than more balanced assessments and recommendations of realistic trends” (Wart, Citation2003, p. 224). Discretion is a convenient general notion by which the employees’ strategies, actions or behaviours can reflect their true meanings. In public institutions are present only the abstract limitations of discretion, because “no amount of discretion can divest an act of the executive power from its character of a law-executing act” (Kelsen and Trevino Citation2005, p. 256), but “this determination is never complete … [because] the higher-level norm cannot be binding with respect to every detail of the act putting it into practice” (Kelsen, Citation1992, p. 78). Despite every effort to elaborate (legal/administrative) discretion, Kelsen believed “traditional jurisprudence has yet not found an objectively plausible way to settle the conflict between will and expression” (Citation1992, p. 81). Lipsky moved from legal discretion with a clear recognition on the importance of street-level bureaucrats, their decisions, routines and devices that “effectively become the public policies they carry out” (Citation2010, p. xiii). Lipsky’s the gap between the reality of practice and public-service ideals is seen also in a gap between the expectations of management reforms and the reality of the culture of accountability (Romzek, Citation2000; Romzek & Ingraham, Citation2000). Nevertheless, there is (still) no clear distinction between the administrative (legal) and political discretion. Among two things, there is always a middle, and this stands also for the mentioned known types of discretion: their middle could be ED (the latter is not formally known, although it is practised on a daily basis even on the larger scale and scope than the previous two).

Discretion as a form of empowerment in public services can be divided into three groups: to administrative (legal) discretion at adjudication, to political discretion at making public policies and to employee (personal) discretion at choosing the most appropriate tools for different situations (and a personal recognition of situations as the situations), where tools are determined in advance, while their usage in different situations is not (and cannot be). Each part indicates a broad flexible power of public administrations: while the elements for the first are determined in the law, the other two are (especially the second, i.e. les actes de gouvernement, or royal prerogatives) recognized as such in the case law. Legal rules consist from words that can be specific and rigid or open-textured and flexible; when they are used in cases where two or more legal alternatives are possible, the public servants use administrative discretion. Political discretion (or a royal prerogative) is known in all countries and it is framed in the basic constitutional competencies of the executive or the legislative branch of power.

On the other hand, ED arises from the (non-)usage of official competencies, from the (in)activation of official powers that are (un)determined for a specific official position and the interpretation of (un)determined legal notions (that can be recognized as reasons for decision and therefore incorporated in legal discretion). ED could be a denominator of the public employee’s will to do—or not to do—something: it can be present also in cases where an employee does not exercise administrative discretion. It is present also where the well-established techniques, procedures or legal standards are enacted (what will an employee do on a particular day, who will he listen, for how long, what usual or non-usual means will he use for a specific assignment, to which problem will give more attention or what facts will be recognized as alarming problems). ED is connected with soft law, with the executive’s material acts, negotiation, communication and constant interaction with citizens and interest groups. The new (regulatory) forms of actions, tools or manners are (re)assembled and (re)arranged according to the contexts of given time and place, where all relevant parameters are in a (temporary) equilibrium. ED does not mean empowering officials to get the job done with more formal jurisdictions; to empower someone is to give or delegate new power or authority. ED is about (in)actions within the existing competencies in the light of future solutions and improvements, which are ex-post acknowledged from a management as essential for the agency’s operations. ED is the most “living thing” (a mix of emotions, reason and courage) in the rules, due to its presentation of human (in)actions, values, (ir)rational thinking, human empathy or emotions, the (sub)conscious and other elements. Combined with the present flexibility, interleaving, intertwining, integration, disintegration, direct and indirect influence on the near and more distant effects along the stability of basic legal principles and human rights (the rule of law and legality, while justice with its righteousness, equitableness, or moral rightness, is closer to the first frame), there can be only a rough idea on the working predispositions of ED.

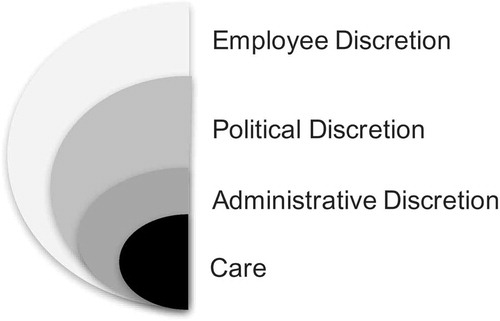

For Davies, informal discretionary power—which was so far the most similar notion to ED—is the lifeblood of an administrative process that includes functions as “initiating, prosecuting, negotiating, settling, contracting, dealing, advising, threatening, publicizing, concealing, planning, recommending and supervising” (Citation1977, p. 440), and the most awesome discretionary power is the “omnipresent power to do nothing” (Davis & Pierce, Citation1994, p. 105). The interpretation and implementation of rules fall within the scope of ED because they give to rules—within a specific context—their meanings and effects. For public bodies, the right question is not only for what, where and how much discretion can be given but how this discretion emerges and evolves in accordance with the situation. This holds especially if “there are no recipes for creating good interpretations” (Raz, Citation2009, p. 117). Officials combine the interpretations of formal commands with their activity and/or creativity, while legislators can only use their power to command. Besides the formal (parliamentary) obligations, a result depends on the (executive) context of the case, on the employee’s character and his personal (rational, emotional, ethical cognitive, skills and competencies) characteristics. Complexity in decision-making shows the legal/non-legal frame as too small and one-dimensional to embrace the complex relations between ED and discretion, but it can be assumed ED that is the widest type of discretion that embraces other types of discretion, seen in Figure .

ED could be accepted as an integral element of public decision-making, the element in which the courts’ standards and executive implementations circulate, co-interact and co-inform one another. ED should be tackled by courts from a contextual, personal decision maker’s point of view and legal goals vis-à-vis the imperatives of accountability, transparency and justification. To be able to understand ED, to circumvent arbitrariness, capriciousness or other obvious errors of law and of fact, its basic elements should be known, and this is the content of the next section.

2.2. ED, care and action

Ideas about (un)efficient norms do not arise only from the legal understanding of a problem; the problem of interpretation is not based only in the law, but in the clarity and acumen of an individual, balanced with legal norms, in his understanding (construction) of reality. ED is an official’s power of judgement as ability to apply rules/actions in a specific case; along impossibility to find the unbreakable, deterministic and objective legal rules, remains a space where ED is present, i.e. between a rule and the non-rule, between “is” and “ought” problem.

Such inference is not covered by logic [because] traditional or deductive logic admits only three attitudes to any proposition, definite proof, disproof, or blank ignorance. But no number of previous instances of a rule will provide a deductive proof that the rule will hold in a new instance. There is always the formal possibility of an exception. (Jeffreys, Citation1998, p. 2)

ED is this kind of (in)formal possibility of exception. How could therefore at least a rough frame be given? Based on the description of ED (the high degree of complexity, emergence, mental state, ability to solve unforeseen problems, creativity and learning new things), it is always connected with employees, in our case with public employees. To Hegel, only “[i]n the conduct and character of officers the laws and decisions of government touch individuality, and are given reality. On this depend on the satisfaction and confidence of the citizens in the government” (Citation2001, p. 238). For many citizens, the executives have a “suspicious” discretion that must be “tamed”, but ED is the necessary part of all adaptable rules, needed for the effective public policies: an official’s mental state cannot be easily addressed with another set of rules, because they have different denominators that can be put together only on a higher, meta(systemic)-level that combines mentality with rules and vice versa. Like care, also the assessment, appropriateness and reasonableness are mental operations that cannot be put down in advance, so only paths to walk on when dealing with these operations (that are without practice, only logical or emotional forms) can be given. These paths can be named as the official’s care for people, the environment, nature or other things and can be shown in Figure .

Traditional tools to control actions of public institutions use the similar element as it is present in EDFootnote6: the legal principle of care is the element of ED in which interpretation can take many directions (even a view that is completely reverse from a written rule). A personal attitude of public employees cannot be learned, but it can be (intuitively) enhanced and calibrated with others by practice. There is no guarantee whatever in the past experiences that a rule—that was valid in all previous instances—will not break down in the next case. By using care, it could be presumed a public employee’s inner intention to proclaim something as legally valid and his personal convictions that something is the law can recognize this new occasion as the legal one as a psychological fact of validity and/or a sense of fulfilling a legal norm. Weltanschauung of an official (or ED) is his primary ideomotor; intertwined in relations with other people, with the awareness of multiplicative and mutually supportive (in)actions of legal protection, care is the starting point from which (in)formal competences with the subjective ability to apply authority over a person or a thing operates. A decision that should be or is already made always depends on a public employee’s preparedness or will to recognize, make and implement it as such.

3. ED as the element of QoG

As formalism needs informality to present the unity, the same stands for the formal rule of law vis-à-vis informal ED. Although the rule of law is one of the cornerstones of democratic societies, it cannot per se reveal personal contexts that are present prior-and-post decision-making. This is done by employees who bring it to life in their (in)formal practices. Due to the second law of thermodynamics—like in all equilibrium systems—order tends to disappear and “requires a constant source of mass or energy or both to sustain the ordered structure … [because of this] no general laws could predict the detailed behaviour of all nonequilibrium systems” (Kauffman, Citation1996, pp. 12–13). The public institutions as non-equilibrium systems must fill new (HamiltonianFootnote7) energy in their actions to sustain order; this can be done by communication, negotiation, persuasion, participation and other elements that are present in ED. With otherwise suitable and sufficient skills, knowledge, experience etc. care is one of the most important elements of a competent state. The latter has to be in balance with democracy and strong rule of law (Fukuyama, Citation2014). This balance of the public institutions depends on ED as the will to balance/rationalise something at all; by this, it becomes the essential part of the QoG. ED is only a part of QoG (it is “QoG from the individual standpoint”), because the latter is not an individual level construct; it is a higher level construct—such as local government, state/province-level government or country-level government—so the overall values of individuals can be related to QoG. In a cross-country setting, some authors have already shown that national culture—as “the universal level in one’s mental software” (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, Citation2010, p. 6) and/or the collective mental programming that differentiates the individuals of a nation from others—can influence the cross-country differences in governments (Hofstede et al., Citation2010; Klasing, Citation2013; Tabellini, Citation2008). Although QoG is not an individual level construct, the individual can have his impact on QoG solely from his individual standpoint, from his ED. Due to this “deficit”, QoG is here elaborated from the mentioned standpoint, focused on ED. QoG is here presented with the help of Holmberg and Rothstein’s QoG as impartiality in the exercise of public power (Citation2012). They define impartiality as a condition “[w]hen implementing laws and policies, government officials shall not take anything about the citizen or case into consideration that is not beforehand stipulated in the policy or the law” (Citation2012, p. 24). Their definition is correctly focused on officials (plural), because QoG at the end represents the overall results of all of them; their procedural definition of QoG is also fairly precise, but they do not include in QoG reasonableness as something that is stipulated in the policy or the law as its material and legal elementFootnote8 from which impartiality is derived in the first place. A legal norm cannot be abused only when the corruption, clientelism, favouritism, discrimination, patronage, nepotism or undue support to special interest groups occurs, but it can be abused also when an unreasonable (even absurd) decision is implemented equally for everyone. Every servant should do his best to respect human dignity and equality; this “best way” is too complex to put it down due to its relations to the human character and context of its use, but it could be nevertheless shown how reasonableness can be included into QoG to have a better view on ED. By the exclusion of reasonableness, Holmberg and Rothstein could not exclude only the first but also—according to the number of possibilities in a set of 2n items (22 = 4)—other three possibilities. QoG can be more fully described with the combination of impartiality and reasonableness and vice versa than only with impartiality. The combination of impartiality and rationality gives four options and their outcomes.Footnote9,Footnote10

The above-given options show that corruption is not possible only at the implementation phase but can be even greater in a phase when criteria are set (systemic, organised corruption); they show also the combinations II and IV as the best. QoG (as was already said it is a higher level construct, but it can be viewed from the individual’s level, i.e. what the individual can help to have better QoG) is therefore not only impartiality, but it is the combination of reasonableness in determining proper criteria and impartiality in their implementation (in each and all cases together), which are mutually intertwined (merge into one another). A result is shown in relations between care and justice and between legitimacy and fairness. Neutrality means diligence and fairness for everyone, while reasonableness means objectivity (equality) and justice for all. The newly proposed “four-corner” definition of QoG serves both for the determination of reasonable criteria for all (in the context of the assessment of situations) and for adjudication in individual cases: after a reasonable determination of objective criteria follows their impartial applications that through their feedbacks return into the first.

The proposed definition of QoG is similar to the definition of the rule of law (QoG = RL) used by the World Justice Project,Footnote11 while the Project’s nine factors of the rule of law indexFootnote12 crucially depend on or are the very ED itself. The latter could be on the other hand through perceptions synonymous with the rule of law definition used by the World Bank.Footnote13 If QoG (and the rule of law) is defined with the above-proposed definition and description—what does this means for ED? QoG was only descriptively presented, while a direction of future behaviour, i.e. of ED (although it cannot be fully predicted), could be in the mix of emotional, rational, social and system’s intelligence. ED is the official’s intangible “living and active processor” that (re)assembles means and people to achieve results. This “walking and thinking human calculators” are in the first step no other than public employees. The first step in a lot of cases could be already a simple recognition that others may also have a point in their reasoning, and we do not have to defend our decisions regardless of the price. Although this at least sounds good, it is still not clear enough and practical how to act in daily life; although we found the combination of reasonableness in determining proper criteria and impartiality in their implementation as the promising approach, we still do not know how to deal with these terms. A promising path towards solution is given below.

4. A path to deal with ED

To more fully understand ED, we must comprehend complexity. For this goal, a cybernetic view will be used due to its focus on the adaptive, sensitive, responsive and viable institutional model of social organisations (Ashby, Citation1957; Beer, Citation1994; Beer & Eno, Citation2009). Ashby’s law of requisite variety tells us that only variety can destroy variety,Footnote14 and to deal with different difficulties, there must be a similar number of responses, which is (at least) as characteristic as problems expressed. To the problem of complexity in decision-making can be therefore approached only with the same or similar amount of complexity. Conant–Ashby theorem states that “every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system” (Conant & Ashby, Citation1970). This cybernetic rule basically says decisions are only as good as decision makers. A regulatory goal therefore suggests a model sufficiently similar to reality, while the essential feature of a good regulator is in its blockage of the flow of diverse disturbances to some essential variables that reflect the same disturbances. Due to the law of requisite variety, control can be constantly (re)acquired not only by public employees but also by other persons (their perceptions, opinions and actions). If the public interest is the interest of the public, the latter should have a say and a foot in it. Practical solutions to problems can give only people; they control ED through employees’ and theirs (in)actions, i.e. results. Similar ideas that (basically) emphasize public participation can be found at numerous scholars, but as practice shows, this approach is clearly not enough for QoG. The latter can be put on a higher level methodically with the people’s participation combined with IT platforms, if a system’s point of view is presented and used to generate a public opinion as the aggregation of people’s inputs, outputs and feedbacks that display the world through the people’s eyes. These dispositions are formed on the self-organisation as one of the basic elements of complex adaptive systems that tend to progress towards a state of equilibrium (Ashby Citation1960; Foester Citation1960; Gershenson & Heylighen, Citation2003). The more diverse opinions are represented, the more complementary bits of truth can be given. A step towards a practical solution could be in the models of collective wisdom or collective intelligence (Brabham, Citation2013; Briskin, Erickson, Ott, & Callanan, Citation2009; Landemore & Elster, Citation2012; Surowiecki, Citation2005; Tovey, Citation2008) that in search of optimal decisions involve a great number of people, patterns, networks, connections and diversity. This approach is generally named as “digital-era governance” (DEG) which involves “reintegrating functions into the governmental sphere, adopting holistic and needs-oriented structures and progressing digitalization of administrative processes” (Dunleavy, Margetts, Bastow, & Tinkler, Citation2005, p. 467). As these models incorporate the interconnected people, they also reflect the adaptive and emergent complex systems that are by their rearrangements able to control their internal and external environments through the change of input parameters based on a system’s goals vis-à-vis outputs. ED as the idea could be therefore theoretically amplified by DEG, while these ideas could be established only practically as the final evaluator of their merit.

A better understanding of ED can be achieved only through mutual (inter) actions. By this, we basically described what is already known as the co-production of public services (Loeffler & Bovaird, Citation2016; Osborne, Radnor, & Strokosch, Citation2016; Osborne & Strokosch, Citation2013; Radnor, Osborne, Kinder, & Mutton, Citation2014). Loeffler and Bovaird define it as “public services, service users and communities making better use of each other’s assets and resources to achieve better outcomes or improved efficiency” (Citation2016, p. 1006). ED through the multiple and diverse people’s needs and interests through their aggregation in DEG can give the impartial implementation of reasonable criteria and a reasonable determination of objective criteria (the definition of QoG) while their implementation can be based solely in practice for which co-production—or other different forms of public–private collaboration/engagement—is needed. The importance of ED and/or co-production for the law should not be forgotten; the present public law does not fully embrace the importance of ED (do not mistakenly understand it as administrative discretion). The latter should involve citizens not only in the decision-making (public consultation, participation and negotiation, elections, legislative networks, IT platforms for collective wisdom) but also actively in the implementation phase (along the known qui tam actions or civil actions in the name of the state and popular actions, also new ways for public–private competition, autonomy, active citizens’ engagement in the delivery of public services) for which the legal science should develop or (temporarily/experimentally) use new legal techniques (e.g. the experimental [the limited time and scope with the evaluation of rules’ results], diagram [norms are easier to understand through partial and more visual steps] and different scenario [different norms for different values according to changing contexts] norms, probability, sampling, Bayes nets, IT-based rules and actions). These ways are yet to be explored in the practice of public law and public administrations.

5. Conclusion

Legal efforts to standardize, quantify and transform the knowledge, reason, emotions and courage of public employees into public benefits can never be complete; many elements depend on a human, who adapts, learns, chooses, compares, interprets and reacts on elements from the environment. The rule of law is linked not only with orders or with decision-makers who made them but is fully vivid only in their (emerging) interactions. Complex, the lifelike behaviour is a result of simple rules unfolding from the bottom up, like the life itself. The interesting and complex behaviour can emerge from a collection of extremely simple components. A top-level echelon of decision-makers cannot tell each person what to do in every situation, and the top-level systems are forever running into combinations of events they do not know how to handle but are needed to keep parts together. If they are too rigid, they block the system’s ability to learn, evolve and adapt, while if they are too open, there is no system at all. Constantly changing environments can be handled mostly by trial and error. A recipe to handle complexity can be accomplished in two steps: if the public official and his regulatory and/or implementation stance (be open to new information, compare them with existent ones, make new hypotheses, test them, see what happens, acknowledge mistakes, remake operations and try again; be aware of details and never forget the basic legal principles and human rights) is present, and as the second, if many officials (with such stance) independently, but mutually with other people/citizens at the same time, do things in a “e-co-manner” (electronic communication, co-innovation, co-operation etc.). Although the paper started with the aim to more fully describe the state of affairs within the public administration, it ends with the importance of co-production.

Based on the overall description of ED as the active motor or processor that is present in each public official as a human being, the question from the introduction (“Is ED the precondition for the quality of government”?) can be partially answered as positive, while for a whole answer, other people are needed in active and collaborative manner. ED is not only here to stay—it was always here. If left alone, it will manage itself according to the employees’ personal interests, desires and worldviews, for the good (or bad) of a whole organisation. ED as the “living, active processor” (re)assembles means and people to achieve goals; the first step for ED’s fuller understanding could be achieved with education and training, the second with a communication system in which the official’s personal insights for care, legitimacy, fairness and justice are put in parallel with other officials’ and citizens’ notions, and the third step with their active, practical cooperation, collaboration or coproduction. Usually, the best is not a matter of price, but a matter of value. And the latter can be formed only in mutual actions and their results. If governments give citizens real possibilities for their active engagement in the administration of public affairs given that citizens use them, QoG could be better. ED can be encompassed only with the same amount of employees/citizens’ discretion. According to Maistre’s quote (“every country has the government it deserves”), it is up to us what we will (not) do.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mirko Pečarič

Mirko Pečarič has obtained Master of Science and PhD at the Faculty of Law, University of Ljubljana. He has passed also the national law exam. In 2013, the Government of the Republic of Slovenia appointed him as the State Secretary at the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport. As the associate professor, he teaches the courses of Administrative Law, Public services and Introduction to Law. He wrote a series of legal opinions and requirements for the assessment of the constitutionality of laws; he is the author of four monographs and numerous scientific articles. The research reported in this paper relates to wider concepts of co-production of public services and values in the public administration.

Notes

1. This is the basic reason why many statistically based papers are de facto not effective: they describe the past, while the life constantly changes, it is context-sensitive and/or differently evolves in the future. The world’s problems would have been resolved long ago, if everything written in statistically based paper had been true. Many papers are apparently scientific because they contain some “numbers”, despite their ineffectiveness. Life does not follow numbers—they are only one useful way to present it, but they are not its essence. Many papers (and reviewers) have replaced this order, but this is not the subject of this paper.

2. Holland (Citation1995, pp. 10–37) among them enumerates the aggregation, tagging, nonlinearity, flows, diversity, internal models and building blocks.

3. Regulation can be all encompassing; it is not only the command-and-control regulation but it can be a thing or a process by which changes occur in practice. Not only in complex, but also in all states—if we understand regulation as every kind of action that affects or shapes conduct—regulation is always decentred (if we look at it from the standpoint of effects, it is the most regulated when it is implemented).

4. Between objects, through institutions and, in bodies, through incorporations is present “the permanent battle within the field as its motor. We see, incidentally, that there is no antinomy between structure and history and that which defines the structure of the field … is also the principle of its dynamic” (Bourdieu, Citation1980, pp. 200).

5. Wittgenstein has rejected the paradox of following and breaking the rule by treating action in accordance with the rule as its practice: “there is a way of grasping a rule which is not an interpretation, but which is exhibited in what we call ‘obeying the rule’ and ‘going against it’ in actual cases…. And hence also ‘obeying a rule’ is a practice” (Wittgenstein, Citation1986, pp. 81).

6. The courts have many times imposed new obligations to the Executive with the help of flexible legal principles, as the principle of care (diligence) can demonstrate (T-167/94, Detlef Nölle v Council [1995], C-269/90, Hauptzollamt München-Mitte v. Technische Universität München [1991]).

7. Energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government…. It is not less essential to the steady administration of the laws, to the protection of property against those irregular and high handed combinations, which sometimes interrupt the ordinary course of justice, to the security of liberty against the enterprises and assaults of ambition, of faction and of anarchy (Hamilton, Citation2010, pp. 471–72).

8. Due to its non-inclusion, they reach the following conclusion: “when a policy has been decided upon by the political system, be it deemed just or unjust according to whatever universal theory of justice one would apply, QoG implies that it has to be implemented in accordance with the principle of impartiality” (Holmberg and Rothstein, Citation2012, p. 26).

9. I. Impartial implementation of irrational criteria (the result is carelessness and inefficiency), or vice versa—irrational criteria are determined impartially (the result is a lack of diligence or failure). II. Impartial implementation of reasonable criteria (biased unreasonable determination of criteria is not possible because through a conscious awareness of biased [negligent] approach their identifier is still “reasonable”; the result is justice, fairness, efficiency and effectiveness) III. A reasonable determination of biased criteria (the result is corruption, ineffectiveness), or vice versa—the biased implementation of reasonable criteria (the result of corruption, inefficiency).

IV. A reasonable determination of objective criteria (the result is legitimacy, diligence, efficiency and effectiveness).

10. With the help of Figure is shown that reasonableness in determining proper criteria and impartiality in their implementation are similar to the power of generalisation and to care that are the building elements of ED. A sign in the shape of number “8” represents the vertically put the sign for infinity “∞” that represents an external rotation on the path of number 8 (from 1 with a determination of hypothesis to 5 and then back to 1 with its change).

11. To the World Justice Project, the rule of law is a system in which the following four universal principles are upheld: (1) The government and its officials and agents, as well as individuals and private entities, are accountable under the law. (2) The laws are clear, publicised, stable and just; are applied evenly; and protect fundamental rights, including the security of persons and property. (3) The process by which the laws are enacted, administered and enforced is accessible, fair and efficient. (4) Justice is delivered timely by competent, ethical and independent representatives and neutrals, who are of sufficient number, have adequate resources and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve (Citation2016, p. 9).

12. Constraints on government powers, absence of corruption, open government, fundamental rights, order and security, regulatory enforcement, civil justice, criminal justice and informal justice.

13. Rule of law captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence (Kaufmann, Kraay, & Mastruzzi, Citation2010, p. 3).

14. If the variety of the outcomes is to be reduced to some assigned number … variety must be increased to at least the appropriate minimum. Only variety … can force down the variety of the outcomes (Ashby, Citation1957, p. 206).

References

- Ashby, W. R. (1957). An introduction to cybernetics. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Ashby, W. R. (1960). Design for a brain: The origin of adaptive behavior. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Beer, S. (1994). Beyond dispute: The invention of team syntegrity. Chichester; New York: Wiley.

- Beer, S. (2002). What is cybernetics? Kybernetes, 31(2), 209–219. doi:10.1108/03684920210417283

- Beer, S., & Eno, B. (2009). Think before you think: social complexity and knowledge of knowing. Wavestone Press.

- Berkeley, G. (2003). A treatise concerning the principles of human knowledge. (T. J. McCormack, Eds.) New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

- Bourdieu, P. (1980). Questions de sociologie. Paris: Minuit.

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). Habitus, code et codification. Actes de La Recherche En Sciences Sociales, 64(1), 40–44. doi:10.3406/arss.1986.2335

- Brabham, D. C. (2013). Crowdsourcing. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Briskin, A., Erickson, S., Ott, J., & Callanan, T. (2009). The power of collective wisdom and the trap of collective folly. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Conant, R. C., & Ashby, W. R. (1970). Every good regulator of a system must be a model of that system. International Journal of Systems Science, 1(2), 89–97. doi:10.1080/00207727008920220

- Confucius. (2003a). Analects: With selections from traditional commentaries. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

- Confucius. (2003b). Confucius analects: With selections from traditional commentaries. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Cziko, G. (2000). The things we do: Using the lessons of bernard and darwin to understand the what, how, and why of our behavior. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Davis, K. C. (1977). Administrative law; cases-text-problems (6 ed.). St. Paul: West Pub. Co.

- Davis, K. C., & Pierce, R. J. (1994). Administrative law treatise (3 ed.). Boston: Little, Brown.

- Descartes, R., Spinoza, B. D., & Leibniz, G. W. V. (1974). The rationalists: Descartes: Discourse on method & meditations; spinoza: Ethics; leibniz: monadolo gy & discourse on metaphysics. New York: Anchor Books.

- Dunleavy, P., Margetts, H., Bastow, S., & Tinkler, J. (2005). New public management is dead–long live digital-era governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. doi:10.1093/jopart/mui057

- Ehrlich, E. (2002). Fundamental principles of the sociology of law. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Feltz, B., Crommelinck, M., & Goujon, P. (2006). Self-organization and emergence in life sciences. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Feynman, R. P., Leighton, R. B., & Sands, M. (1965). The feynman lectures on physics. Vol. Later Printing edition. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

- Foester, H. (1960). On self-organizing systems and their environment. In M. C. Yovits & S. Cameron (Eds.), Self-organizing systems (pp. 31–50). London: Pergamon Press.

- Fukuyama, F. (2014). Political order and political decay: From the industrial revolution to the globalization of democracy. London: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Gell-Mann, M. (2002). The quark and the jaguar (VIII ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman & Company.

- Gershenson, C., & Heylighen, F. (2003). When can we call a system self-organizing? In J. Ziegler, T. Christaller, P. Dittrich, & J. T. Kim (Eds.), Advances in artificial life, lecture notes in computer science (pp. 606–614). Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Hamilton, A. (2010). The Federalist. (J. E. Cooke, edited). Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

- Hegel, G., & Fredrich, W. (2001). Philosophy of right. Ontario: Batoche Books.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3 ed.). Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill.

- Holland, J. H. (1995). Hidden order: How adaptation builds complexity. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

- Holmberg, S., & Rothstein, B. (2012). Good government: The relevance of political science. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Huntington, S. P. (1968). Political order in changing societies. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Jeffreys, H. (1998). Theory of probability (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kauffman, S. (1996). At home in the universe: The search for the laws of self-organization and complexity. Reprint edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. 2010. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. SSRN Scholarly Paper. ID 1682130. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network.

- Kelsen, H. (1992). Introduction to the problems of legal theory: A translation of the first edition of the reine rechtslehre or pure theory of law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kelsen, H., & Javier Trevino, A. (2005). General theory of law and state. New Brunswick, N.J: Transaction Publishers.

- Kierkegaard, S. (1997). Skrifter (Vol. 18). Copenhagen: Søren Kierkegaard Research Center.

- Klasing, M. J. (2013). Cultural dimensions, collective values and their importance for institutions. Journal of Comparative Economics, 41(2), 447–467. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2012.09.003

- Landemore, H., & Elster, J. (eds). (2012). Collective wisdom: principles and mechanisms. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lanza, R., & Berman, B. (2013). Biocentrism: How life and consciousness are the keys to understanding the true nature of the universe. Dallas: BenBella Books, Inc.

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public service. 30th Anniversary Expanded Edition. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Loeffler, E., & Bovaird, T. (2016). User and community co-production of public services: What does the evidence tell us? International Journal of Public Administration, 39(13), 1006–1019.

- Morgan, B., & Yeung, K. (2007). An introduction to law and regulation: Text and materials. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Motte, A., & Cajori, F. Newton. (Eds.). (1947). Sir Isaac Newton’s mathematical principles of natural philosophy and his system of the world. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Osborne, S. P., Radnor, Z., & Strokosch, K. (2016). Co-production and the co-creation of value in public services: A suitable case for treatment? Public Management Review, 18(5), 639–653. doi:10.1080/14719037.2015.1111927

- Osborne, S. P., & Strokosch, K. (2013). It takes two to tango? Understanding the co-production of public services by integrating the services management and public administration perspectives. British Journal of Management, 24, S31–47. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12010

- Prigogine, I., & Stengers, I. (1984). Order out of chaos. New York, N.Y: Bantam Books.

- Radnor, Z., Osborne, S. P., Kinder, T., & Mutton, J. (2014). Operationalizing co-production in public services delivery: The contribution of service blueprinting. Public Management Review, 16(3), 402–423. doi:10.1080/14719037.2013.848923

- Raz, J. (2009). Between authority and interpretation: On the theory of law and practical reason. Oxford: OUP Oxford.

- Romzek, B. S. (2000). Dynamics of public sector accountability in an era of reform. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 66(1), 21–44. doi:10.1177/0020852300661004

- Romzek, B. S., & Ingraham, P. W. (2000). Cross pressures of accountability: Initiative, command, and failure in the Ron Brown plane crash. Public Administration Review, 60(3), 240–253. doi:10.1111/0033-3352.00084

- Sartre, J.-P. (2001). Jean-Paul Sartre: Basic writings. S. Priest edited by. London: Psychology Press.

- Surowiecki, J. (2005). The wisdom of crowds. Reprint edition. New York, NY: Anchor.

- Tabellini, G. (2008). Institutions and culture. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(2–3), 255–294. doi:10.1162/JEEA.2008.6.2-3.255

- Tovey, M. (ed). (2008). Collective intelligence: Creating a prosperous world at peace. Oakton: Earth Intelligence Network.

- Waldrop, M. M. (1993). Complexity: The emerging science at the edge of order and chaos. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Wart, M. V. (2003). Public-sector leadership theory: An assessment. Public Administration Review, 63(2), 214–228. doi:10.1111/1540-6210.00281

- Wittgenstein, L. (1986). Philosophical investigations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- World Justice Project. 2016. The WJP rule of law index 2016. World Justice Project. https://worldjusticeproject.org/sites/default/files/documents/RoLI_Final-Digital_0.pdf, accessed May 5, 2017.