Abstract

This article presents the results of an investigation, conducted in Sweden, of how inviting tenants to participate in renovation of large-scale housing in marginalized areas can lead to increased tenant power over renovation. The results show that the “Consultation model for renovation” employed, which was developed by the Union of Tenants, gives more power to tenants than previous models used in Sweden, although certain dilemmas exist that seem to be hard to overcome. The article concludes by discussing the role of “consultation models”. It suggests that it would be very interesting if such models not only aimed to give tenants power over renovation—within the framework housing companies are prepared to offer at the time—but also contributed to challenging practices and played a role in system change.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article discusses a new model for consultation of tenants in renovation of rental apartments. The model has been tested in Sweden. The increasing gap between the rich and poor in general worries actors in low-income neighbourhoods. For this reason, giving increased power to tenants is on the agenda. Renovation without influence from tenants has been shown to push them out onto the street or into other vulnerable situations, as rent increases are considerable. The tested model gives more power to tenants and can be considered successful. There are, however, dilemmas that a consultation model alone cannot solve. The article describes four such dilemmas. It concludes by stressing that consultation models should be designed not only to operate within the systemic constraints set by a housing company at the point in time when renovation occurs, but also to change the systems in use.

1. Introduction

Inviting tenants to participate in renovation of large-scale housing in marginalized areas is not common practice, at least not if invited participation means that property owners are ready to actually share power with tenants. Do property owners want to share power? How does it work in practice when they do? This article presents the results of a study on such participation in Sweden.

2. State of the art

Research on participation in renovation of housing has largely focused on renovation aimed at comprehensive energy improvements and renovation involving environmental friendly building materials. There are many studies on tenants’ inclination to accept such improvements (e.g. Blomsterberg & Pedersen, Citation2015; Guerra-Santin et al., Citation2017; Wittenberg & Fleury-Bahi, Citation2016), stating that enhancements must be experienced and visible, and (Ástmarsson, Jensen, & Maslesa, Citation2013) stressing that dealing with “the landlord/tenant dilemma” (if tenants pay the bill for energy, the landlord is not interested in change) implies the need for an array of tools. Others combine this with a focus on innovation (Boess, Citation2017; Gianfrate, Piccardo, Longo, & Giachetta, Citation2017), claiming that technical solutions, such as adding passive-solar to buildings, need to involve tenants in decision-making, as this changes their behaviour, which is required for success. There are others (Calvaresi & Cossa, Citation2013) who have also stressed the need to build trust with tenants, as trust develops a sense of ownership of environmental refurbishment programmes, which is necessary for long-lasting environmental results. These studies often take a critical stance on tenant influence, thinking it complicates sustainable building, as tenants may not want to or be able to afford the changes needed to redirect society towards preventing global warming.

There is another field of research with a more positive view on tenant participation in housing. This research deals with a collaborative housing movement stemming from the German “Baugemeinschaften”, which refers to a group of people acting together as commissioner of a renovation or building project in which they will later live (Czischke, Citation2017). At present, collaborative housing is employed widely in Germany with numerous examples in cities, such as Freiburg, Tübingen and Hamburg, and is supported by the municipalities through institutional innovation and new financing frameworks (Ache & Fedrowitz, Citation2012). Nearly 10% of residents in Tübingen live in such housing schemes. Generally, research on collaborative housing takes a positive view of resident influence, claiming that, apart from leading to high-quality housing for involved inhabitants who are often from the middle class, it may also—in this era of housing market liberalization—open up new interesting market segments for affordable housing.

Tenant participation in renovation is also related to gentrification and social exclusion issues on a larger scale than housing. In this field of research, it is generally stated that residents have very little effect on urban transformation of cities and neighbourhoods. Moreover, such processes are often used to reduce the share of social housing in cities (see, e.g. Redmond & Russell, Citation2008). It has even been claimed that the weak position of tenants, characterized by a tokenist bias, puts up a smokescreen to hide other stakeholders’ interests, for example building companies’ profit interests, and political moves to create a different social mix in neighbourhoods (Gustavsson & Elander, Citation2016). Some researchers go so far as to claim that “the current form of displacement (through renovation) has become a regularized profit strategy, for both public and private housing companies” (Baeten, Westin, Pull, & Molina, Citation2017, p. 631).

Despite this quite negative view on resident involvement in regeneration of neighbourhoods, there are several hopeful studies on tenant participation on an area level using certain tools and methods to connect local activities to national and higher levels. Looking at the US and British studies, Gaventa (Citation2006) claims that citizen engagement in policy processes needs to be analysed thoroughly from a power perspective and suggests using a “power cube” for that purpose. Fung (Citation2006), in the United States, also proposes using a “power cube” as base to form strategies for citizen involvement, and to avoid tokenism. Based on studies conducted in Denmark, Ástmarsson et al. (Citation2013) label their method “a package solution” and agree with the collaborative housing movement (Ache & Fedrowitz, Citation2012), saying that it should consist of legislative changes, financial incentives and dissemination of information. Suschek-Berger and Ornetzeder (Citation2010), based in Austria, present a “flexible model” with seven phases for involving occupants and other stakeholders in large-volume residential refurbishment projects. With experiences in the Netherlands, de Bruijn, Vos, and Ham (Citation2008) offer a “smart renovation toolkit” for fast and efficient renovation of all post-war housing in Europe, linking the owner, the architect, the occupants and the contractor. Domínguez, Camargo, Quijano, Iñarra, and Gómez (Citation2016), working in Spain, focus on citizens’ quality of life by applying their “CITyFiED project methodology” as a strategy for sustainable urban renovation. Studying Swedish contexts, Lind, Annadotter, BjöRk, HöGberg, and Af Klintberg (Citation2016) claim that the “mini, midi, maxi” model may be a useful tool for renovation that enables a high proportion of remaining tenants after refurbishment. Common to these examples of methods that have been tested in connection with renovation, however, is the relatively low degree of autonomy of the tenants. Hence, they are given power in the renovation process, but within a framework that is very limited. The problem with this is closely related to the liberal changes that are taking place on the housing market.

3. A “system switch” in Swedish housing

The changes in Sweden have great similarities with what is happening in the whole of Europe. But because Sweden had a different starting point, with public instead of social housing, there is reason to explain how the changes have affected the country.

By the end of the 1990s, Sweden—considered one of the most equal countries in the world with regard to income at the beginning of the 1980s—had an income differentiation equivalent to that at the beginning of the 1970s (Lindberg, Citation1999, p. 313). Additionally, and as a probable consequence of this development, Sweden has shifted, as has, for example Britain, to policies stressing selective rather than general measures for solving social problems. In fact, during the latter part of the 1990s, Sweden was ranked as the most segregated OECD country, in that the most exposed housing areas in Sweden had the highest share of immigrants in comparison to all other OECD countries (Swedish Government, Citation1998, p. 28).

This development has had a major impact on the housing market in recent decades. According to Clark and Hedin, in Europe “since the early 1990s, the housing sector has been radically reformed in accordance with neoliberal ideology, with far-reaching consequences for the increasingly polarised poor and rich” (Clark & Hedin, Citation2009, p. 173). Baeten et al. show that this also applies to Sweden. They clam that “The Million Program, then one of the main vehicles to install universal welfare in Sweden, has now become one of the main vehicles to actively work against welfare” (Baeten et al., Citation2017, p. 468).

Paralleling this liberal turn in policy and practice, a huge housing shortage has developed in Sweden due to the low level of construction in relation to needs. According to the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning, the country needs to build 600,000 residences before 2025. In this situation, Sweden also faces the need to renovate the post-war settlements, especially the one million homes built in bigger cities during the 1960s and 1970s. In 2008, it was stated that 800,000 of these rental apartments would need to be renovated within ten years (Industrial Facts, Citation2008), but only a portion of them have been dealt with. The majority of immigrants in Sweden live in these areas. Thus so far, neither the government nor the municipalities have agreed to subsidize the renovations, despite the fact that critics argue that rental revenues should have been saved for renovation.

Although the pace of renovation is insufficient compared to the needs, a wave of renovation of rental apartments has occurred during recent years. This has resulted in a big protest movement among tenants against the high rents caused by renovation. The rent increases have sometimes landed at 10%, but increases of 30–60% are much more common; there are even examples of 100% increases in rent after renovation. Studies conducted by authorities (Boverket, Citation2014) and academic studies consistently point to these problems. For example, BergenstråHle and Palmstierna (Citation2017) investigated how many tenants would end up with a household income below a reasonable standard if renovation were to continue as it has begun. They found that, with a rent increase of 50%, one third of tenants would be forced to move. And there are very few cheaper alternatives left, meaning either that renovations force people out onto the street or that municipalities subsidize their living costs—which they do more and more infrequently in Sweden these days.

Inspired by the British Staying Put movement (London Tenants Federation, Loretta Lees, Just Space, & SNAG, Citation2014), citizens in the biggest cities in Sweden formed joint protests against renovation plans and support each other in confronting property owners (ThöRn, Krusell, & Widehammar, Citation2016). In some cases, for example for marketing reasons, they have succeeded in changing property owners’ plans, from, for example a 64% increase in rent to more reasonable increases around 15%—which is still high for many tenants. In most cases, however, the tenants have lost the fight. This resulted in the government appointing a “Tenant Investigation” (Citation2017), the aim of which was to increase tenants’ power over renovations. Among other things, the government wanted to change the present circumstance, which is that tenants lose 98% of the cases in court. The investigation suggested several altered practices and changes in law, which await political decisions in 2018.

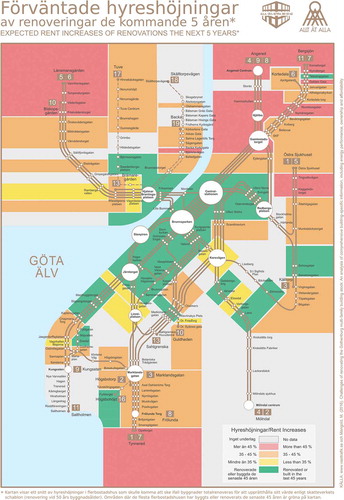

For their part, activists do not have high expectations that changes in law will radically influence practices. The citizen movement against renovation—a movement to support tenants staying put—is therefore still on-going now in 2018. The Union of TenantsFootnote1 in Sweden, with 500,000 members, is one of the actors involved in this fight. When the wave of renovations began, the Union was criticized for being far too passive, partly by the larger citizen movement that developed but also by its own members, who were directly affected and dissatisfied because they had not received support. The Union of Tenants thereafter developed its own form of resistance. Civil society has also developed other associations that are pursuing this fight, for example the association “Everyone should be able to stay”, which supports all civilians who are threatened by displacement due to refurbishment. The association also produces research that can be used to intercede in policy discussions. This “tram map” (see Figure ) visualizes the polarization in the city of Gothenburg (Everyone should be able to stay, Citation2018).

Figure 1. Public housing with rental apartments in Hammarkullen, Gothenburg, Sweden. Photo: Albin Holmgren

Such circumstances for tenants are the same all over the country, not only in the three biggest cities but also in all of the medium-sized cities, all of which have stigmatized housing areas from the 1960s and 1970s—with buildings in need of renovation. Many people in Sweden are affected by the development taking place. If it is true that “the current form of displacement (through renovation) has become a regularized profit strategy, for both public and private housing companies” (Baeten et al., Citation2017, p. 631), what should be done about it?

4. A new model for tenant participation in renovation

The Union of Tenants is a member-driven organization, with many activities carried out at different societal levels even when renovation is not on the agenda. For example, the Union negotiates with all property owners about the yearly rent increase. At the local level, it has a number of activities run by elected representatives. When renovation is imminent, the Union has two roles: supporting all tenants who want support (i.e. not only members) when the property owner communicates with the tenants about the renovation; negotiating for the tenants about the new post-renovation rent levels. The first role has to be agreed upon with each property owner. The second role is decided by the government and always applies. The first role is related to the Swedish law stating that all tenants must individually approve in writing a renovation plan for their apartment allowing the property owner to implement it. If approval is not given, the owner can turn to court and, as mentioned earlier, owners win this battle in 98% of cases. Even if property owners almost always win, they usually seek cooperation with the Union, as it is expected to increase the number of tenants who approve renovation. Going to court takes time and gives owners a bad reputation.

In 2014, the Union of Tenants in the western region of Sweden started developing a new model for tenant participation in renovation, and soon after it began implementation to put the model to the test. The model is called “Consultation model for renovation” (in Swedish Samrådsmodell för renovering). It was partly based on a previous model, but had been improved concerning three specific aspects: increased power for tenants; more explicit process thinking; and caring more about the relationship between tenant consultation and the rent negotiation process.

The model has six phases (see Figure ) with different scenarios, depending on what is happening in the process. There are also checklists linked to each phase. The six phases are:

Pre-process

Dialogue

Negotiation

Approval

Renovation

Assessment

Figure 2. The ‘tram map’ shows that the most vulnerable housing areas, which are situated near the end stations of the trams, are the areas that face more than a 45% increase in rents (marked with colour red) if the property owners continue to renovate as before (Everyone should be able to stay, 2018)

Putting the new model to the test coincided with the initiation of a research project called “Learning Lab Hammarkullen: Codesigning Renovation” (learninglabhammarkullen.se), of which the present author is project leader. The Union of Tenants is part of the research project as a co-funding “practitioner”; the involved actors agreed to investigate the “Consultation model for renovation” and to prepare for and learn from its implementation in the suburb of Hammarkullen, where 125 apartments were facing renovation in a first turn. Hammarkullen was built during the period 1968–1970 and is among the one million homes constructed during the 1960s and 1970s. The apartments relevant for renovation are located in one of the large bright buildings at the back (see the cover image, Figure ).

Figure 3. This process map of the ‘Consultation model for renovation’ with six phases has been developed by the Union of Tentants in western Sweden to help employees in the organization to carry out consultation with tenants prior to renovation. It is accompanied with checklists, and there is a written agreement with each housing company, containing certain paragraphs about how to carry out the dialogue

“Learning Lab Hammarkullen” is a transdisciplinary research project (Carew & Wickson, Citation2010; Posch & Scholz, Citation2006). It aims to develop knowledge concerning how tenants can become involved early in renovation processes, and how they can become involved in actual decision-making. Another participating actor in the research project is the public housing company Bostadsbolaget in Hammarkullen, which owns all of the 2200 rental apartments in the area.

5. Empirical material and method of investigation

Empirically, this article is based on a small study within the research project. The study involves recorded semi-structured qualitative interviews (Kvale, Citation1996) with twenty-two persons concerning the “Consultation model for renovation”. The interviewees were asked about their experiences of consultation within each of the six phases mentioned above. Two types of actors were chosen for interviews: employees and elected representatives from the Union of Tenants (fourteen persons) and employees in public and private housing companies (eight persons). The individual actors from each actor type were chosen by the Union of Tenants based on their recent experience of the consultation model in different municipalities in western Sweden. To ensure anonymity, the interviewees’ names and workplaces were not used when presenting the results of the study.

For knowledge production based on the actor third type—the tenants—a course in consultation was designed based on what was learnt from the interviews (see Figure ). Hence, a course was designed, based on lessons from the interviews, for explicit use in a suburb like Hammarkullen—a course that would appeal to the tenants and empower them. For this reason, role-play was introduced. The one-day course was carried out with eight tenants in Hammarkullen. The participants were also interviewed as part of the course, which led to learning discussions like those pursued in focus groups (Kvale, Citation1996; Morgan, Citation1988). The Local Union of Tenants chose the participants based on age, sex and spoken languages, as one goal was to test simultaneous interpretation in the course (to Arabic). Besides the eight tenants, six trainers/role players from the Union of Tenants participated, as well as the research project leader. The implemented test of the course was studied through participant observation and filmed/recorded (Dewalt & Dewalt, Citation2010). These tenants, as well, were anonymous when presenting the results of the study. This was on their own request, as they were waiting to start a real consultation process and were worried about power relationships.

Figure 4. The course for tenants on renovation. Role cards and event cards drive the game forward, and the role-play describes through learning-by-doing the relationship between plans for renovation, tenant consultation and rental negotiation. Photo: Jenny Stenberg

Methods used in the empirical analysis include content and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Schreier, Citation2012; Vaismoradi & Bondas, Citation2013); the analysis aimed at identifying themes within the empirical material and determining trends, patterns and correlations between the themes. The analysis was inductive in the sense that the perceived themes came mainly from the empirical material—and were developed in a collaborative learning process with involved “practitioners”—but it was also deductive in the sense that the content was analysed based on theories of power and learning.

6. Theoretical framework for analysis

The present article’s theoretical base includes power analysis in terms of “black boxes” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981), theories of organizational learning focused on “espoused theories”, “theories-in-use”, “double-loop learning” (Argyris & Schön, Citation1995) and “triple-loop learning” (Beairsto & Ruohotie, Citation2003).Footnote2

According to Callon and Latour (Citation1981), micro-actors are individuals, groups, and families, and macro-actors are institutions, organizations, social classes, parties, and states. When power is exercised, the relationship between these two types of actors is formulated. However, what is important here is that there really »is no difference between the actors which is inherent in their nature. All differences in level, size and scope are the result of a battle or a negotiation« (Callon & Latour, Citation1981, p. 279). Therefore, what interested Callon and Latour was not the question of classifying different groups of actors, but of trying to understand the process of how micro-actors became macro-actors.

Callon and Latour (Citation1981) argue that an important foundation for exercising power is the macro-actor’s translation of the micro-actor’s desires as well as the strategy of putting elements into “black boxes”: boxes that can be re-opened by micro-actors when questioning their content:

An actor grows with the number of relations he or she can put, as we say, in black boxes. A black box contains that which no longer needs to be reconsidered, those things whose contents have become a matter of indifference. The more elements one can place in black boxes—modes of thoughts, habits, forces and objects—the broader the construction one can raise. Of course, black boxes never remain fully closed or properly fastened/…/but macro-actors can do as if they were closed and dark (Callon & Latour, Citation1981, p. 285).

Thus, a macro-actor who has put certain elements into “black boxes” does not need to re-negotiate from scratch all the time; this actor may instead use the taken-for-granted assumptions hidden in “black boxes” in new negotiations. “To summarize, macro-actors are micro-actors seated on top of many (leaky) black boxes” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981, p. 286).

“Black boxes” may be re-opened, and that is what usually happens when we see a strong actor in society suddenly changing positions in the hierarchy. The prerequisite for such a change is established when a micro-actor no longer takes for granted the elements in “black boxes” and questions the content—and if this questioning turns out to be successful, the actors change places with regard to their respective strength. “In order to grow we must enrol other wills by translating what they want and by reifying this translation in such a way that none of them can desire anything else any longer” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981, p. 298). In other words, an actor who succeeds in formulating a value base on which several actors may agree is in a position to exercise power.

Thus, in a power analysis, one should search for “black boxes” and the relations or translations between actors that always precede closing or opening “black boxes”. Then one can understand how and why a micro-actor becomes a macro-actor; an action that has taken place results in the exercising of power—an action that relinquishes power to another actor.

Theories of organizational learning are related to the concept of “black boxes” in that the concept analyses why thoughts and habits are put in boxes. It distinguishes between “espoused theories”—theories that persons use to “explain or justify a given pattern of activity” (Argyris and Schön Citation1995, p. 13)—and “theories-in-use”—the real reasons for actions. The “theories-in-use” are often embedded in systems used by members of an organization and are often not visible, which may be one reason why an “espoused theory” is presented. Other reasons may be that “theories-in-use” are not generally or politically accepted or are embarrassing to members of the organization.

Based on these concepts, Argyris and Schön (Citation1995) developed a theory of action for organizational learning. The theory is based on the conviction that change in knowledge is always preceded by an action. This focus on action, consequently, makes the learning process visible; the action per se can reveal whether the learning process has been effective (Argyris & Schön, Citation1995, p. 33). Further, Argyris and Schön argued that an organization starts to learn whenever an individual in the organization inquires into a problematic situation on the organization’s behalf (Argyris & Schön, Citation1995, p. 16). However, for an organization, there are different ways of learning. Argyris and Schön distinguished between “single-loop learning” and “double-loop learning”. The first may be adequate for solving organizational problems when an organization only needs to change its strategies of action; however, these situations are hardly ever a problem for organizations, as the procedures of “single-loop learning” are more or less well known and therefore not particularly interesting to study. To solve more serious problems, organizations need deeper learning:

By double-loop learning, we mean learning that results in a change in the values of theory-in-use, as well as in its strategies and assumptions (Argyris & Schön, Citation1995, p. 21).

Furthermore, a third learning loop has been developed in academia. According to drawing on Beairsto and Ruohotie (Citation2003), “double-loop learning” may be considered to have taken place when there has been a revision of established theories of business, while “triple-loop learning” additionally includes the generation of processes to challenge theories of business (see Figure ). “Triple-loop learning” thus describes a situation in which a process has been initiated that deliberately aims at confronting an organization’s prevailing “theories-in-use”.

Figure 5. ‘Triple-loop learning’ after Beairsto & Ruohotie (2003: 134). Previously presented in Stenberg (Citation2004)

7. Results

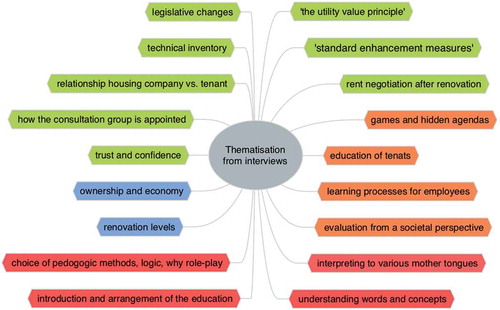

The outcome of the interview study concerning the “Consultation model for renovation” revealed that the new model gives more power over renovation to tenants as compared with the previous model. How much power depends in part on how the agreement is formulated, i.e. what paragraphs of the proposed agreement the respective housing company concurs on with the Union of Tenants, and in part on how the consultation process is carried out. The consultation process was described as highly complex, and the interviewees pointed out a number of themes (see Figure ) they thought needed to be discussed in order to grasp the whole situation and assess the model’s usability.

8. Thematizations from interviews

The interviewed employees and elected representatives from the Union of Tenants and the interviewed employees in housing companies provided a similar enumeration of the themes they considered to be important to focus on and discuss, although there were many differences in their descriptions of problem-solving methods meant to increase tenants’ power over renovation. The outlined themes are visible in this picture (see Figure ) where orange themes came from the Union of Tenants, blue from housing companies and green from both. Knowledge production from the third actor type—the tenants—resulted in addition of the red themes.

9. Dilemmas

The analysis of interviews revealed a number of difficult situations or dilemmas including apparent power problems. It turned out that these had something in common; in accordance with the theory of “black boxes” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981), there was always one or more actors who wished a box would be kept closed. The most important such situations or dilemmas are described below.

9.1. One mayor problem is that tenants believe what things cost matters

The most obvious dilemma was the Catch 22 situation in the trinity: (1) “the utility value principle”; (2) “standard enhancement measures” and (3) the procedure of rent negotiation in renovation.

“The utility value principle” (in Swedish bruksvärdesprincipen) exists as a result of social democratic housing policy intended to avoid market rental levels, but to still face market liberalism to some extent when negotiating rents. The first part of the dilemma, “the utility value principle”, is the accepted system for comparing rents, and the idea is that rental apartments—both public and private—with the same utility value shall have the same rent. Location was not evaluated initially, but it has been progressively entered as a criterion. After renovation, a property owner can demand that “a utility value trial” of the stock be conducted, which means that the renovated apartments are compared to similar units in the area and a rent increase can be approved based on the results. Previously, this was only done by private owners, but at present, given the liberalization of the housing market, public owners have also begun demanding such trials to increase their revenues:

Housing companies have changed, ever since 2010. We changed our executive group and CEO, because we have completely different incentives today, we’re supposed to have improved financial conditions, our whatever you call them, and that means that when we renovate, we have to increase rents (Interview, housing company).

The second part of the dilemma, “standard enhancement measures” (in Swedish standardhöjande åtgärd), is a frequently used concept in renovation, and it means that some renovation measures give the property owner the right to increase the rent, while other measures do not. The agreement rests on the assumption that property owners put aside money from rentals for what is called maintenance, i.e. keeping up the standard, but not for renovations that increase the standard. This implies that pipe replacements (in Swedish stambyte) in buildings are not considered a standard enhancement measure, while changing the surface layer in bathrooms after pipe replacements becomes a discussion question, depending on what surface material is chosen. Replacing old material with similar material is not considered a standard enhancement, while different material can be considered standard enhancement:

So do you choose wall and floor tiles to earn money?

Partly.

Or do you choose wall and floor tiles because otherwise you couldn’t afford to renovate?

We choose wall and floor tiles because they make the property more modern,/…/and we choose wall and floor tiles because they increase the property value, and we get more rent. Yes.

(Interview, housing company).

The third part of the dilemma is the procedure of post-renovation rent negotiation. In the “Consultation model for renovation”, the Union of Tenants tried to avoid past problems with tenants’ increasing lack of confidence in the organization caused by post-renovation rent negotiation. Tenants believed that the Union of Tenants was pushing for buildings to be renovated and that the Union was behind the high rent increases. This occurred because the Union of Tenants quite often assumed responsibility for calculating what renovation options would cost, as a result of housing companies presenting either far too low estimates or no calculations at all. Hence, the “Consultation model for renovation” has been designed to bring responsibility for the renovation and its costs back to the owner. The idea is to have a successive rent negotiation in parallel with the process in which tenants are consulted on renovation measures. Thus, rent negotiation is a series of meetings between employees from the Union of Tenants and the housings company, while the consultation on measures is a series of meetings between tenants (supported by the Union of Tenants) and the housings company. The interaction between the processes is handled by one person who participates in both rent negotiation and the consultation.

The interviews show that each of the three parts of the dilemma is complicated. However, as they also affect each other, it is very difficult to handle different situations. For example, tenants in consultation about measures based on the principle of “standard enhancement measures” opted out of certain improvements to keep down the rent, but after the whole process had been clarified, the owner conducted “a utility value trial” and was permitted to raise the rent anyway. Thus, the tenants could have kept the proposed renovation measures and paid the same rent. The difference instead became the owner’s profit.

The threefold question is: Why does the Catch 22 situation in the trinity exist, who are the actors that keep that “black box” closed, and why they are doing it? The interviews show that while employees in both the housing companies and the Union of Tenants keep the box closed, individual tenants are more interested in opening it. The first two stand on different sides of the issue of liberalization of the housing market (more or less market rental levels), while the last ask for transparency in order to understand the logic of tenant consultation and increase the power of tenants over renovation. This is a logical demand from the tenants, as the current procedure is to ask tenants to consider the “standard enhancement measures” without knowing what they will cost in increased rent—an impossible task. The tenants will only (in the best case) learn about the costs right before it is time to give their approval, but by that time it is too late for discussion and change; they can only approve or deny and will not win in court, which makes a denial worthless. Clearly, the “Consultation model for renovation”—which has been implemented to help tenants obtain more power—still has a way to go in addressing these and similar power problems. The Union of Tenants needs to help tenants to open that “black box”, but to do so it in a way that does not allow free market rental levels, as this would not benefit tenants in general.

The next “black box” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981) described by the interviewees was the dilemma of when—and in relation to what kinds of decisions—tenants are invited to consultation:

9.2. Plans for renovation are outlined before tenant consultation

As the interviews were structured around a timeline and discussing the content of the six phases of the process (Pre-process; Dialogue; Negotiation; Approval; Renovation; Assessment), it soon emerged that there were problems related to decisions concerning how renovation would be done. The “Consultation model for renovation” presupposes that these decisions are made at the end of the third phase, but according to the interviewees that was not the reality. Decisions concerning how to renovate had often been made by the housing companies before the Pre-process started.

The decision-making process generally began with the housing company management making an investment decision about renovation of an area, based on external economic analysis, their own internal problem reporting and statistics on material deterioration. To determine the extent of the renovation, a technical inventory was carried out that constituted the basis for budgeting. Only after this inventory had been completed were the renovation plans made available to the tenants, at which point the consultation in collaboration with the Union of Tenants began.

The interviews revealed that in none of the cases had the tenants, or even the Union of Tenants, seen the technical inventory or the content of the other analyses on which the housing company based their decision about renovation. This information was kept in a “black box” and the housings companies were the main actors keeping it closed. As it turned out, however, the interviewees from the Union of Tenants presented no examples showing that they opposed it themselves or that they considered it important to open the box and examine its contents. Still, they described vividly the problems related to its existence, for example that tender documents for the procurement of builders could be posted publicly even before the tenant consultation. Interviewees from housing companies also expressed doubts about the procedures, and some of them stated that they only understood the extent of the problem afterwards. Initially, one interviewee explained, it appeared obvious to make all the decisions about, e.g., renovation of bathrooms, as they considered themselves “the experts”. However, as the process proceeded they had afterthoughts:

The first thing the tenants said was ‘I don’t want an electric towel dryer’ and ‘I don’t want shower doors’, while we started the procurement process.

Including those things?

Exactly! The procurement people thought we needed to make a decision…

(Interview, housing company).

In this context, it should be mentioned that an electric towel dryer and glass shower door are considered “standard enhancing measures”. Moreover, the interviewees from housing companies pointed out the importance of not changing the tender documents after publishing them, because this increases the cost of procurement.

A problem similar to that with bathroom furnishing has also been described by interviewees in relation to bathroom wall and floor materials. When tenants in one housing area opposed the choice of ceramic tiles, instead of plastic wallpaper and carpets, upon realising the rent increase it entailed, none of the interviewed housing companies met their demands. The interviews revealed that decisions about ceramic tiles were always taken high up in the organization long before any consultation with tenants, based on the circumstances described above in relation to the first dilemma. What was even more interesting in this example was the complication that the consultation group of tenants chosen to represent everybody were the people who had to receive all this criticism from the rest of the tenants, although they had never actually chosen ceramic tiles, a choice that housing company employees presented as self-evident. It should also be mentioned that installing ceramic tiles in bathrooms is considered a “standard enhancing measure” when the pre-renovation surfaces were plastic. Moreover, installing ceramic tiles in all bathrooms had already been put in the tender documents for procurement, which had been published.

The actual interviewed housing company employees, however, later regretted their point of view. Not because ceramics in all bathrooms was a bad choice from an environmental and economic perspective, but because by not opening up for criticism in the process before taking a decision, they missed information provided by the tenants concerning how they could act to ensure the tenants could continue living there. Instead, most of the tenants were forced to move. Because the municipality remains responsible for its citizens, this only created costs elsewhere when people were forced to leave their neighbourhood and move to poorer, even more vulnerable areas. Additionally, the housing company did not learn how to renovate in a broadly sustainable way, and it continued making the same mistakes with the rest of its stock. The employees pointed out that it was their insecurity and ignorance that made it difficult for them to change their views in time. Thus, education of housing company employees, leading to organizational learning (Argyris & Schön, Citation1995), would provide better conditions for transferring power to tenants.

The rehetoric around this dilemma seen in the interviews was interesting to note. Especially the way it was presented by the interviewees for the tenants. As it seems, none of them told the “theory-in-use” for the tenants—thus they did not say that the reason why ceramic tiles were chosen was because this was the best for the housing company from an economic point of view. Instead, several different “espoused theories” seem to have been presented to the tenants to convince them to accept the choice of ceramics (already decided on, which was not always clear to the tenants). Examples of “espoused theories” were to say that most tenants want ceramic tiles (which they had not asked yet), it is not possible to put ceramic tiles in some bathrooms and not in others (which is fully possible), plastic alternatives harm the building (which is not true if handled well), ceramic tiles are cheaper in the long run (which is not self-evident; plastic alternatives do not last as long, but cost less). There is also sometimes cross-reference to “pipe replacement”, a concept that is a “black box” in itself, as most tenants, especially those who do not speak Swedish well, do not know what this means. The “espoused theory” was then outlined as follows: we have to change the pipes, it is inevitable technically (which is not true, there are other ways), which makes it necessary to put up ceramic tiles (which is completely unrelated to pipe replacement). Hence, what housing companies do when plans for renovation are outlined prior to tenant consultation is to take decisions over the tenants’ heads concerning whether they can afford renovation to a higher standard or whether they will maintain the standard they have. Housing companies are very interested in keeping that “black box” closed, and most of them do not let tenants challenge it at all. Actually, the Union of Tenants plays a role in keeping that “black box” sealed. Even if several of the interviewed union employees and elected representatives considered the issue very problematic, there is nothing in the “Consultation model for renovation” that prevents this dilemma from happening. The only opponents of that “black box” are the tenants who face the problem in consultation, but by that time it is too late.

This is also affected, of course, by the fact that 98% of tenants lose in court if they do not sign the approval for renovation and the housing company goes to trial to get the right to renovate. Housing companies are therefore confident that they have the right to take these kinds of decisions. In fact the court, the chairman of the board and the jurymen are all actors who sit on this “black box” and help in keeping it closed. The fact that the government appointed a Tenant Investigation (Citation2017) on the matter, proposing changes in the law and praxis, makes the government an actor trying to open this “black box”. It will be evident by the end of 2018 whether the policy contributes to reassessment.

There is another new phenomenon associated with renovation in Sweden, which is to offer different renovation options. Often three options are given, called “mini, midi, maxi” (Lind et al., Citation2016). The options are already packaged when presented to the tenants and all options generally entail a rent increase—the lowest maybe 10% and the highest 60%. Offering three complete options does not really result in increased power for tenants. The content of each option is equally difficult—or even harder—to influence, as this is presented as a developed, democratic working method. The question of why being given options is of interest to the tenants has not been answered. Nor has the question of why three options, instead of five or ten, is answered. Still another question has not been addressed: Why are the options so thoroughly packaged that they cannot be altered. Last but not least, there is the question of why a “zero-alternative” (no rent increase) is not the answer. In this respect, the “mini, midi, maxi” approach may be described as a “black box” in itself. It is presented as applying developed democracy in the renovation process, but does not give more power to tenants. The actors sitting on that “black box” are mainly the housing companies, but again, the Union of Tenants helps them keep it sealed by not challenging them.

Another phenomenon is “incremental rental increase” (in Swedish hyrestrappan). The concept means that the rent increase is spread over several years. One of the interviewees made a pertinent comment:

I really think it’s a lot. Really./…/That the rents go up so much I don’t know if I could have managed, imagine if you live in an area and pay 6,500-7,000 crowns now and then the rent is suddenly way over 10,000 crowns, that’s a really big adjustment. We’ve tried to overcome it, or like I say, we try to fool the tenants, to get them to learn to live with it. So we phase it in, I mean you pay a fourth of the rent increase year one, half year two, three quarters year three and full rent for the first time year four (Interview, housing company).

When these large rent increases are discussed, “incremental rental increase” often comes up in response, oddly silencing the frequent critic. It may thus also be considered a “black box”. Given that politicians in Sweden agree in policy documents that nobody should be forced to move due to renovation, it is a cynical response—especially when offered to the most vulnerable part of the population. In the same way, it may be considered a “back box” used to avoid presenting rent increases in percentage after renovation. It is a trend among housing companies to only present the increase in crowns, the motivation (“espoused theory”) being that it is easier for tenants to understand. However, omitting percentages makes it difficult to compare across areas, which tenants would be well served to do when involved in a renovation consultation and when searching for support from people in the same situation in other cities. It seems possible that the reason for not presenting percentages is that doing so makes it obvious that the increase is high and that it can easily be compared to others; the “theory-in-use” would thus instead be “to pour oil on the waves”.

The next “black box” described by the interviewees is the dilemma of the target group of the renovation:

9.3. For whom rental housing neighbourhoods are renovated

In Sweden, due to the prevalent economic and ethnic housing segregation and knowing that there is no social housing but instead public housing, large-scale housing neighbourhoods in the outskirts of cities largely accommodate working-class residents, often with low wages. These are the areas that are now facing renovation. Against that background, it is especially interesting that the question concerning the renovation money that should have been put away never received any response. That is truly a “black box”, and many actors are sitting on it. The interviewees did not develop that theme much, instead it was seen more as a matter of course that the money was not available. However, the related issue of for whom rental neighbourhoods are actually being renovated came up frequently. The absence of any renovation money legitimizes a focus on the middle class. There is general political confidence in the notion that attracting middle-class residents to a municipality or a neighbourhood can solve many of the place’s problems, partly because new middle-class residents pay high taxes, partly because they have great purchasing power, and partly because they are thought to reduce the stigma that large-scale working-class neighbourhoods suffer from.

One of the interviewees from a housing company said that the focus on the middle class has become crucial to housing policy in the municipality. Because there is a huge housing shortage in the country, the municipality has invested in building new housing to attract the middle class. Due to the unusually high building costs in Sweden, these buildings cannot—even if populated with middle-class people—bear their own costs through rents alone. According to the interviewee, this meant that the municipality’s investment in renovation of the older stock had to wait. This was the view despite the fact that the renovation needs of the old stock are great: there are, e.g., many reported water leaks, buildings must be more energy-efficient to meet government standards, and tenants complain of poor maintenance. The interviewee maintained that this development indicates that municipal money has been used to subsidize middle-class accommodations in newly built apartments, while working-class people still have to live in unrenovated apartments. Moreover, if these apartments actually were renovated, the renovation process would be carried out with the same goal in mind, namely to improve the neighbourhood by renovating in a way that attracts the middle class. According to the interviewee, the reason for this, besides the general positive expectations mentioned above, is that no renovations can bear their own costs. Thus, the fact that renovation money has not been put away over the years, together with liberalization of the housing market, also legitimizes the practice of renovating rental apartments for anyone other than the people already living in them. The idea of creating another neighbourhood, through renovation, is the underlying theory: the “theory-in-use”. That is the reason the housing company wants “standard enhancements measures”.

The interviewee described this as a Catch 22 situation. On the one hand, he is required to conduct dialogue with tenants on how they want the owner to renovate their homes; on the other hand, he is expected to implement the management’s idea of attracting the middle class. These are two roads going in opposite directions. Forming a trustworthy relationship under such circumstances is not possible, and this is why the consultation process did not work well—it appears to have been a sham even if this was in no way the intention of the housing company employees. In the case mentioned, the expected high rents caused many tenants to act to get away from the area rather than to engage in the consultation. The housing company assisted in this process and offered other alternative accommodations in other neighbourhoods (cheaper, but also waiting to be renovated). Even if this is meant to support the tenants, it implies that the public housing company actively helped to complete the process of gentrification they had started—a process in which working-class people are forced to move around, with all that this entails in terms of broken social ties and children having to change schools.

Again, the court is yet another actor sitting on this “black box” and helping to keep it closed. According to interviewees from the Union of Tenants, the praxis of the court in these cases has been to assess two questions. First, whether or not the housing company is entitled to raise the standard. This has been allowed if there are other apartments in the area of higher standard. The logic is that there is an assumed “general citizen” who wants an improved standard if such a standard exists in the area. Second, the court considers whether there are technical reasons for renovation. Here, it relies on the technical inventory (“black box”) and on building legislation. Thus, none of the court’s assessment criteria includes the person actually living in the apartment. The tenant’s financial situation is similarly not included. The court does not include the rent or the rent increase in its assessment.

Renovation plans are, thus, not made based on the existing tenants’ personal economy. The question here is how anyone with honest intent could to draw up a plan for consultation with tenants about renovation under such circumstances.

This “black box” of “for whom rental housing neighbourhoods are renovated” is opposed at higher levels of society by the Union of Tenants. Several of the interviewees from the Union described the dilemma, and it was taken into account when designing the “Consultation model for renovation”. However, the reduced social responsibility of public housing companies is a trend that continues despite a great deal of criticism.

The next and last “black box” described by the interviewees is “the conception of the tenants”, thus the interviewees’ picture of who the tenants are and how they think tenants can be involved in consultation.

9.4. Who are the tenants? Are they considered competent? how should they be chosen for participation in consultation on renovation?

If, despite the difficulties described above, consultation with tenants on renovation is on the agenda, how should such a process be implemented? When interviewing employees, it was interesting to note that there were considerable differences in their views on how consultation should be carried out. These differences first became visible when discussing the question of how a “consultation group” (in Swedish samrådsgrupp) should be appointed.

Before the “Consultation model for renovation” was implemented, it was common for tenants to be hand picked by a housing company to participate in a “reference group”. Those preferring that procedure thought the group should be “representative” of the area, thus that it should correspond to the area with respect to gender, age, ethnicity, etc. The persons would then, in the consultation process, be free to present their own individual perspectives on renovation because the group’s composition ensured that all perspectives were represented. Hence, these interviewees advocated that a mother knows enough about other mothers to speak for them. It should be added that the housing company has the power to determine which tenants to choose when the “reference group” procedure is applied. They may decide not to ask people who are perceived as troublesome when taking the initiative in acquiring knowledge about the process and talking with others. Such individuals, however, could be excellent representatives of their neighbours, as they may not be afraid to question taken-for-granted ideas. The image of who the tenants are varied a great deal. Some of the interviewees from housing companies actually thought they should not have to form tenant groups at all; they regarded themselves as “good” property owners and excellent representatives of the tenants. They felt they only needed to knock on doors and ask questions of a more practical nature concerning the condition of the apartments. Group discussions were viewed as neither possible nor recommended. These interviewees were admittedly in the minority, but nonetheless noticeable. It seems clear that some housing companies would still apply such methods if the Union of Tenants had not pushed for another development.

Forming representative groups had, however, often been experienced as quite difficult. Many of the interviewees actually found it very problematic that certain groups were never represented, for example ethnic groups that are particularly vulnerable to being excluded from society, or tenants with a very low income. The idea therefore came from the Union of Tenants to develop an empowerment process, whereby elected tenants would take on the traditional democratic role of representing all other tenants in the dialogue about renovation processes.

This is why the new model included a paragraph stating that a “consultation group” is to be chosen by tenants at a public meeting. Those preferring that procedure wanted the persons to “represent” all other tenants in the area, thus to assume responsibility for carrying out a democratic process in the area, working to find out what all tenants need and want and conveying that to the housing company. For that to become a reality, the persons in the group needed to be elected and the election should be run by the tenants, not the housing company or the Union of Tenants:

I’m going to offer suggestions about how they can represent all of the tenants, maybe identify a number of tools. I’ll never express my views on the basic offerings, that isn’t my role here, but more… to suggest, that is, coach them, along this path. And I think that on that point it’s really important that… or I see my role, that I leave it to them… because I also have power, you know. I know a lot about how we work, so I could easily have set my own agenda, but I relinquish all my power to them. Still, I’m responsible for the process moving forward. I think it’s very important, if you’re going to work like I do as operations developer and have lots of responsibility, that they feel secure with that role, but they’re the ones with the power (Interview, Union of Tenants).

The different opinions expressed in the interviews about how to choose tenants were largely split between the housing companies and the Union of Tenants. The new model may be seen as the Union of Tenants’ way of opposing the “black box” of how to choose tenants—a “black box” that housing companies have been sitting on for some time. The Union of Tenants has not succeeded, however, in opposing this “black box” forever; they have to re-negotiate it every time a renovation agreement with a housing company is written. There are examples of when important parts of the agreement have been removed. For instance, the text “representatives of tenants are elected at a housing meeting” had been deleted in one case the interviewees referred to. Unfortunately, in the governmental Tenant Investigation (Citation2017), the tenants were not recognized as a group, giving them collective rights by law. Thus, as long as such things are not statutory, actors like the Union of Tenants must constantly monitor tenants” rights in relation to renovation.

Another dividing line between the interviewees from housing companies and those from the Union of Tenants was the view on tenants’ competence. While the former spoke about presenting easy-to-understand and clear options to choose from, the latter talked about designing courses to help tenants develop the knowledge and skills needed to gain more power in the process. Using simultaneous interpretation to tenants’ mother tongue during consultation was an example that directly highlights tenants’ already existing skills, something that housing companies lose when they persist in merely providing information in Swedish. The interviews concerning the course implemented to empower tenants highlighted the importance of teaching tenants the exact meaning of all the concepts used in consultation on renovation and of doing so in their mother tongues, as the concepts are difficult to understand. If the goal is to transfer power to the tenants, this is a necessary condition, as knowledge of the concepts empowers them. Some examples of concepts that were difficult for the tenants to understand are partly common terms such as “rent negotiation”, “elected representative” and “regular maintenance”, while others were less commonly used in everyday life, such as “standard enhancement measures” and “the utility value principle”. There were around 50 such concepts in use in renovation, and the suggestion came up to write them on cards and translate them on the back side into three or four of the most common languages spoken in the neighbourhood. Implementing such proposals may seem obvious, but the fact is that, in consultation on renovation, translation to the tenants’ mother tongues is not standard practice in Sweden. Rather the contrary. Most housing companies, both private and public, actually prioritize residents learning Swedish over offering clear information and communication.

This dividing line in how the tenants are viewed also has consequences in broader contexts. Are they considered temporary “guests” on someone else’s property? Or are they considered citizens with certain rights over their rental homes? The Union of Tenants has, for example encountered resistance to keeping certain paragraphs in the agreements on renovation—paragraphs that prevent power over temporary vacant apartments from being given to the housing company instead of the tenants. When a housing company sees people as temporary guests, it is obvious to them that they own the right to apartments that are empty for various reasons. In the vast majority of cases, these apartments are refurbished to the maximum and are subject to the highest rent increases. According the interviewees, none of them had chosen to renovate vacant apartments to the lowest possible standard—that is, to strive for more affordable and not less affordable housing in the city. This pattern of action among housing companies prevents people with low incomes from staying in a housing area after renovation and drives gentrification. This is obviously not beneficial to all existing tenants and should be discussed in public democratic fora. In addition, tenants who wish to move to an apartment of different size or in another place in connection with renovation will be hindered from doing so, as the number of apartments available for exchange in the area has been reduced to zero prior to renovation. Moreover, housing companies sometimes deliberately keep many apartments empty before renovation, and the problems can become quite serious. Thus, they consciously, and in opposition to the intention of the law, shift power over renovation of rental apartments from tenants to themselves.

The question of vacant apartments can be considered a “black box” insofar as it is something housing companies try to avoid discussing. And even if the Union of Tenants frequently opposes it, its ambitions are quite low level compared to the problems it causes tenants, which is clear because, in many cases, these paragraphs have been removed from contracts.

There are several “espoused theories” presented by interviewees that defend removing the current paragraph from the agreement. One often-mentioned argument is that the housing companies need vacant apartments for temporary use for tenants while renovating their apartments. Another argument mentioned by several interviewees was that the paragraph about vacant apartments would not correspond with the municipality’s queue system. Really solving these problems, however, has not been discussed. Both arguments can be overcome quite easily, especially in the present period of severe housing shortages when people wait 5–10 years before getting a rental apartment. Thus, the people in the queue would probably gladly agree to contribute knowledge and opinions to a renovation process, even though they would have to wait half a year to move in. It would also be possible to hand over the power to renovate vacant apartments to the tenants as a group—thus to the “consultation group”—thus recognizing their competence to decide what is good for the area. As mentioned above, in the interviews the visible “theory-in-use” for not acting to give tenants power over the vacant apartments is related to views on the tenants. Most housing companies in the study, both private and public, obviously consider tenants their “guests”, and this is also inherent in our terminology—the literal English translation of the Swedish word for tenant is “rental guest”. The other part of the “theory-in-use” is related to financial matters. The housing companies want to maintain power over the vacant apartments to make a profit.

To sum up the fourth dilemma, a shift in power implies an altered view of who the tenants are, their competence, and how they may be consulted in renovation processes. There is an urgent need for the discussion on the dividing line between “reference group” and “consultation group” to continue. The fact that the “consultation group” is actually chosen by the tenants to represent others is one of the changes that may have the greatest potential to increase tenants’ power. The democratic ambitions of the “consultation group”, stemming from the Union of Tenants, have obviously not been adequately communicated to housing company employees, as they still prefer old patterns of action. Of course, one could say that this is just a matter of power and that housing companies have more power than the Union of Tenants, however the interviews revealed a great interest on the part of most of the housing company employees in welcoming a shift in tenant influence on renovation. This as a consequence of the increasing gap between the rich and the poor in general, which they believe is unsustainable, and its specific consequences for neighbourhoods where low-income people live.

10. Discussion and conclusions

The results from analysing the interviews and from participant observation have led to the discussion of four dilemmas:

One mayor problem is that tenants believe that what things cost matters

The plans for renovation are outlined before tenant consultation

For whom rental housing neighbourhoods are renovated

The tenants: Who are they? Are they considered competent? How should they be chosen to participate in consultation on renovation?

The dilemmas were outlined using theories on power, especially discussions about “black boxes” (Callon & Latour, Citation1981), “espoused theory”, and “theory-in-use” (Argyris & Schön, Citation1995). From a pessimistic perspective, it would be logical to conclude that it is very difficult to increase tenants’ power over renovation unless the property owners want it, as the dilemmas described by the interviewees do seem to be very difficult to overcome. From a more optimistic perspective, however, it is possible to conclude that using the “Consultation model for renovation” has really opened the door to change. If one also takes a process perspective instead of a direct outcome perspective only, the conclusions change.

What if the “Consultation model” can actually serve the purpose of opening “black boxes”? The role of the Union of Tenants would then be to help micro-actors in the “consultation group” to learn about “espoused theories” and how to separate them from “theories-in-use”, for tenants to become knowledgeable and powerful enough to oppose “black boxes” and then also help them to succeed in challenging macro-actors and opening “black boxes” for reconsideration—in transparent processes where all concerned tenants can understand and discuss it. Such a view on the “Consultation model” would then imply that it should not only lead to tenants getting more power over renovation within the systemic constraints set by the housing company at the point in time when renovation occurs, but also to changing the systems the housing company uses in renovation processes. Without this objective, there is a risk that the “Consultation model” for tenant participation in renovation would only have a symbolic effect—so-called “tokenism” using Arnsteins’ (Citation1969) language—rather than leading to a real shift of power that benefits tenants.

As mentioned above, changing systems requires “double-loop” (Argyris & Schön, Citation1995) or “triple-loop learning” (Beairsto & Ruohotie, Citation2003) (134), in contrast with “single-loop learning”, which is useful for change of strategies only. One example of necessary systemic change mentioned by the interviewees was the praxis used when actors carry out rent negotiations. Neither the Union of Tenants nor the housing companies had an answer for how to change that system and, more seriously, none of them had investigating this problem and seeking a solution on their agenda. Presumably, this is an undeveloped area because it is a “wicked problem” (Ritchey, Citation2011) that requires “double-loop-learning” with the involvement of many different actors. The reason change is not taking place is because the different actors needed for such a change to occur now only meet when negotiating—they do not meet to learn and succeed with “triple-loop learning”.

Another example of necessary system change was the municipal queue systems for rental apartments. How could such a system be developed to serve renovation processes as well? This too is a “wicked problem” requiring “triple-loop learning” in which many actors need to participate, especially tenants involved in renovation of their homes. Developing such a queue system is, thus, not something for a web technician to solve alone.

A third example of needed systemic change mentioned concerns how housing companies do procurement of renovation. It may seem obvious that one cannot shop before asking what to buy, however, as was also apparent in the interview study, this dilemma is actually not discussed much, and therefore the “Consultation model” in use in these cases must obviously be labelled “tokenism”. This is because it only asks tenants what they want in extremely tight frameworks—sometimes without even acknowledging what the framework is when the dialogue is in progress. Finding a new praxis for procurement of renovation that is well integrated with increased tenant power over renovation is clearly a “wicked problem” that requires “triple-loop-learning”.

Last but not least, there is the more comprehensive problem of for whom rental apartments are renovated and the praxis of targeting the middle class when transforming neighbourhoods. This is particularly problematic in Sweden, which employs public housing instead of social housing to provide affordable housing for the population. The most obvious need for system change discussed by the interviewees is strengthening the tenants’ position in relevant laws. As mentioned earlier, this was initiated by the government when appointing a Tenant Investigation (Citation2017), which awaits political decisions in 2018. Critics believe, however, that the proposals in the investigation will not be sufficient even if approved.

Returning to the state of the art, what does the present article contribute to the research, and what are the important areas for future research? The sharpest criticism offered in previous research was that tenants were given power in the renovation process, but only within a very limited framework. The present article has contributed new knowledge, showing that the problems encountered when tenants have power over renovation are going to increase, and should not solely be considered obstacles and difficulties. From a process perspective, these problems can also be considered “triggers for learning” (Krogstrup, Citation1997), and may lead to system change if they are taken into account in new research or directly in praxis. All in all, it may be concluded that “consultation models” involving tenants in renovation actually need to serve the continuous purpose of opening “black boxes” if they are to give tenants increased power over renovation in an overarching and long-lasting perspective. Research on this topic is just as important as assessments of the direct results of using consultation models.

Acknowledgements

This research has been carried out thanks to Formas – The Swedish Research Council for Environment, Agricultural Sciences and Spatial Planning, which has funded the programme ‘National Transdisciplinary Centre of Excellence for Integrated Sustainable Renovation’ (2013-3634-26822-63) of which ‘Learning Lab Hammarkullen’ is a part. One of the cofunding partners, The Union of Tenants, has very actively contributed to the work in Hammarkullen and to the analysis of the empirical material, namely through the efforts of Johanna Lagerborg, Ola Terlegård, Mimmi Allansson and Anna Malmer. Thanks also to all the other participating practitioners in ‘Learning Lab Hammarkullen’: local employees in the public housing company Bostadsbolaget, other contributors in the Union of Tenants, the University of Gothenburg, Rotpartners, and Rise Research Institute.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jenny Stenberg

Jenny Stenberg is Associate Professor in urban design and planning. Her research and teaching focus on social aspects of sustainable development, specifically on citizen participation in planning in stigmatized and segregated areas in Sweden as well as in European, Latin American and African contexts. In terms of research, she has led or been involved in several projects on the theme of citizen participation, for example Urban Empowerment: Cultures of Participation and Learning (urbanempower.se); How can citizen initiatives interplay with invited participation in urban planning? (mellanplats.se); Learning Lab Hammarkullen: Codesigning Renovation (learninglabhammarkullen.se); Children and Youth Codesigning Cities (codesigncities.se), Mapping Inhabitants’ View of a Suburb (maptionnaire.com), Compact Cities?, and Compact Cities in Informal Settlements (compactcities.se). She has also initiated a Master’s course (suburbsdesign.wordpress.com) in which architect and planning students learn to co-design with inhabitants.

Notes

2. These theories have been discussed previously in Stenberg (Citation2004).

References

- Ache, P., & Fedrowitz, M. (2012). The development of co-housing initiatives in Germany. Built Environment, 37, 395–412. doi:10.2148/benv.38.3.395

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1995). Organizational learning II: Theory, method, and practice. Reading Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

- Arnstein, S. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(8), 216–224. doi:10.1080/01944366908977225

- Ástmarsson, B. R., Jensen, P. A., & Maslesa, E. (2013). Sustainable renovation of residential buildings and the landlord/tenant dilemma. Energy Policy, 63, 355–362. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.08.046

- Baeten, G., Westin, S., Pull, E., & Molina, I. (2017). Pressure and violence: Housing renovation and displacement in Sweden. Environment and Planning A, 49(3), 631–651. doi:10.1177/0308518X16676271

- Beairsto, B., & Ruohotie, P. (2003). Empowering professionals as lifelong learners. In B. Beairsto, M. Klein, & P. Ruohotie (Eds.), Professional learning and leadership (pp. 134). Tampere: University of Tampere.

- BergenstråHle, S., & Palmstierna, P. (2017). Var tredje kan tvingas flytta: En rapport om effekterna av hyreshöjningar i samband med standardhöjande åtgärder i Göteborg (Every third may be forced to move: A report on the effects of rent increases in connection with ‘standard enhancement measures’ in Gothenburg). Göteborg: Hyresgästföreningen Västra Sverige i Göteborg, Bo-Analys Vostra konsulter.

- Blomsterberg, A. K., & Pedersen, E. (2015). Tenants acceptance or rejection of major energy renovation of block of flats – IEA annex 56. Energy Procedia, 78, 2346–2351. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2015.11.396

- Boess, S. (2017). Design participation in sustainable renovation and living. In D. V. Keyson, O. Guerra-Santin, & D. Lockton (Eds.), Living labs: Design and assessment of sustainable living (pp. 205). Switzerland: Springer.

- Boverket. (2014). Flyttmönster till följd av omfattande renoveringar (Movement patterns due to extensive renovations). Karlskrona: Author.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Callon, M., & Latour, B. (1981). Unscrewing the big leviathan: How actors macro-structure reality and how sociologists help them to do so. In K. Knorr-Cetina & A. V. Cicourel (Eds.), Advances in social theory and methodology: Toward an integration of micro- and macro-sociologies (pp. 277–303). Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Calvaresi, C., & Cossa, L. (2013). A neighbourhood laboratory for the regeneration of a marginalised suburb in Milan: Towards the creation of a trading zone. In A. Balducci & R. MäNtysalo (Eds.), Urban planning as a trading zone (pp. 95). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Carew, A. L., & Wickson, F. (2010). The TD wheel: A heuristic to shape, support and evaluate transdisciplinary research. Futures, 42, 1146–1155. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2010.04.025

- Clark, E., & Hedin, K. (2009). Circumventing circumscribed neoliberalism: The ‘system switch’ in Swedish housing. In S. Glynn (Ed.), Where the other half lives: Lower income housing in a neoliberal world (pp. 173). Pluto Press.

- Czischke, D. (2017). Collaborative housing and housing providers: Towards an analytical framework of multi-stakeholder collaboration in housing co-production. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(1), 55–81. doi:10.1080/19491247.2017.1331593

- de Bruijn, D., Vos, S., & Ham, M. (2008). SmartRenovation: A new approach to renovation. Paper presented at the PLEA 2008 – 25th Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture (pp. 1). Dublin.

- Dewalt, K., & Dewalt, B. (2010). Participant observation. U.S.: AltaMira Press.

- Domínguez, J. G., Camargo, C. C., Quijano, H. G. P., Iñarra, P. H., & Gómez, L. M. (2016). Cityfied project methodology: An innovative, integrated and open methodology for near zero energy renovation of existing residential districts. Paper presented at the CESB 2016 - Central Europe Towards Sustainable Building 2016: Innovations for Sustainable Future (pp. 515).

- Everyone should be able to stay. (2018). Spårvagnskartan över förväntade hyreshöjningar i Göteborg (The tram map of expected rent increases in Gothenburg). Retrieved from http://allaskakunnabokvar.se/sparvagnskartan/: Alla ska kunna bo kvar (Association Everyone should be able to stay).

- Fung, A. (2006). Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Administration Review, 66(Special Issue), 66–75. doi:10.1111/puar.2006.66.issue-s1

- Gaventa, J. (2006). Finding the spaces for change: A power analysis. IDS Bulletin, Institute of Development Studies, 37(6), 23–33. doi:10.1111/idsb.2006.37.issue-6

- Gianfrate, V., Piccardo, C., Longo, D., & Giachetta, A. (2017). Rethinking social housing: Behavioural patterns and technological innovations. Sustainable Cities and Society, 33, 102–112. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2017.05.015