Abstract

The democratisation of politics in most post-colonial formations like Nigeria has not been successful in terms of reducing the incidence of voter intimidation, ballot box snatching/stuffing, multiple voting, falsification of results and other associated electoral malfeasance. Thus, electoral democracy in the country is inseparable from monumental and brazen electoral manipulations. Besides the role of civil society organisations and other principal stakeholders in elections, the introduction of a biometric smart card reader for the authentication of voters’ cards seems to have made most of these electoral ills largely unworkable. Specifically, this essay investigated the role of the card reader in improving the credibility of the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria. The study is a qualitative research and it relied on the cybernetics model of communications theory. It found that the novel technology has rekindled the confidence of most Nigerian voters and international partners. Consequently, e-voting should be adopted as a tool for curbing electoral fraud in the country.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Elections in Nigeria and many less developed countries of the world have continued to witness low voters’ turnout because of electoral malpractices. This is the case especially with the 2003 and 2007 general elections in Nigeria. Among others, this article argues that the deployment of digital technology during the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria has made most traditional electoral malpractices very unfashionable. Although the application of the novel technology experienced some hitches during the elections, it has been able to rekindle the confidence of most Nigerian voters and international development partners in Nigeria’s electoral democracy as well as accounted for the drastic drop in the volume of post-election litigations. As a result, the article recommends the full deployment of e-voting as elixir of electoral fraud in the country.

1. Introduction

Free, fair and credible elections are central to electoral democracy and provide a vital means of empowering citizens to hold their leaders accountable. In a multi-party democracy, it behoves both the elected and appointed government officials at all levels of the political system to render periodic accounts of their stewardship to the populace. However, the accountability of public officials in Nigeria has been undermined by the fact that elections in the country are perennially fraught with irregularities. The democratisation of politics has been unsuccessful in arresting electoral frauds perpetrated by different political parties and megalomaniac politicians. It has also been unable to address the administrative misconduct of officials of Nigeria’s Election Management Body (EMB), the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC). The collapse of the First and Second Republics, and also the abortion of the Third Republic through the annulment of the 12 June 1993 Presidential Election are clear indicators of the failure of previous attempts to democratise elections in Nigeria (Omotola, Citation2010).

Elections are important elements of modern representative government. They typify the democratic process; hence, the abolition of elections is often interpreted as the abolition of democracy. Accordingly, “elections are so clearly tied to the growth and development of representative democratic government that they are now generally held to be the single most important indicator of the presence or absence of such government” (Nnoli, Citation2003, p. 220). They are meaningfully democratic if they are free, fair, participatory, credible, competitive and legitimate. Elections are, therefore, adjudged to have met these criteria

when they are administered by a neutral authority; when the electoral administration is sufficiently competent and resourceful to take specific precautions against fraud; when the police, military and courts treat competing candidates and parties impartially; when contenders all have access to the public media; when electoral districts and rules do not grossly handicap the opposition; … when the secret of the ballot is protected; when virtually all adults can vote; when procedures for organizing and counting the votes are widely known; and when there are transparent and impartial procedures for resolving election complaints and disputes (Diamond, Citation2008, p. 25).

However, the historical significance of electoral democracy for human progress does not necessarily mean that in every country elections adequately reflect these traits, or contribute to the material and political wellbeing of the masses of the population. Hitherto, the electoral system in Nigeria has failed to meet the above benchmark enumerated in Diamond. Since the return to civil rule in 1999, elections had been characterised by ineffective administration at all stages and levels (before, during and after), resulting in discredited outcomes. This was largely due to the weak institutionalisation of the primary agencies of electoral administration, particularly the INEC and Nigerian political parties. The INEC is deficient of institutional, administrative and financial autonomy with an attendant lack of professionalism and recurrent political interference. In addition, the desperation of many Nigerian politicians to win at all costs has compromised election administration in the country. The procedures for organising and counting the votes are generally not transparent. The foregoing deficiencies of the EMB have been heightened by the nature and character of the Nigerian state, which thrives on low autonomisation (Ake, Citation1985; Ibeanu, Citation1993; Nwangwu & Ononogbu, Citation2016). Consequently, many eligible voters have become apathetic not because they do not want to participate; they believe their votes would not count.

Fledgling African democracies have persistent difficulties in registering their electors and establishing their identity. Following the polemics about the quality of existing voter rolls, some of these countries have recently introduced reforms to their voter registration systems, such as the adoption of voter identities and of biometric technology. Gelb and Clark (Citation2013) aver that biometric identification systems are already in widespread use for voter registration. Thus, as of early 2013, 34 of the world’s low- and middle-income countries had adopted biometric technology as part of their voter identification system. For instance, different kinds of biometric infrastructure have been used in some African states like Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Zambia with varying degrees of success, to improve transparency in recent elections.

One of the real issues of the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria was the use of innovative anti-rigging biometric devices. The administration of the elections witnessed the use of smart card reader (SCR) for the authentication of biometric Permanent Voters’ Cards (PVCs) and the accreditation of voters. The introduction of these devices was necessitated by the fact that reliable voter registration and identification mechanism are among the preconditions for free, fair and credible elections. However, the legality of the device was questioned. Although section 52 of the Electoral Act 2010 proscribes electronic voting (e-voting), the SCR is a form of identification, not a means of casting a ballot. The use of the SCR in some quarters experienced glitches in its functionality, thereby leading to manual accreditation of some voters. This attracted negative reactions which consequently fuelled the erroneous conclusion that the Nigerian electoral system is not ripe for the application of such technology. However, it emboldened many disenchanted voters to exercise their franchise because of the assurance and confidence that the new system brought.

Although the role of digital technology in improving free, fair and credible elections has been widely acknowledged by officials of EMBs and pro-democracy activists, it has not attracted sufficient attention in the literature. On the contrary, some of the extant studies in this subject have questioned the seeming rush for the deployment of digital technologies in election administration (Barkan, Citation2013; Cheeseman, Lynch, & Willis, Citation2018; Evrensel, Citation2010; Gelb & Clark, Citation2013; Yard, Citation2010). For instance, Yard (Citation2010) addresses the “progress and pitfalls” of new technology deployed by state electoral commissions. In particular, he distinguishes electoral efficiency from electoral transparency and argues that while technology can help to achieve both goals, it tends to be implemented in a way that promotes the former over the latter. By the same token, Evrensel (Citation2010) emphasises the organisation and logistical challenges that digital voting technology often generates. Similarly, Barkan (Citation2013) posits that new technology in Africa often fails because insufficient attention is paid to the broader management structures it needs to function. In other contexts, studies have questioned the cost of digital solutions and highlighted how automation can improve the efficiency of one aspect of the electoral process but leave other major issues, such as voter intimidation, unaddressed (Carlos, Lalata, Despi, & Carlos, Citation2010; Montjoy, Citation2010). In corroboration, Gelb and Clark (Citation2013) argue that digital technology usually encourages a narrow focus on some aspects of the electoral process to the utter neglect of the broader political environment and campaigns. In sum, Cheeseman et al. (Citation2018) argue that the growing use of these technologies has been driven by what they termed “the fetishization of technology” rather than by rigorous assessment of their effectiveness. Accordingly, such devices may create significant opportunities for corruption that vitiate their avowed impact.

The prevalence of electoral irregularities in many transitional democracies, especially in Africa, has accentuated the clamour for and use of voting technologies to uncover and reduce electoral fraud. Thus, some studies have been quite enthusiastic about the role of digital technology in electoral administration (Gelb & Decker, Citation2012; Golden, Kramon, & Ofosu, Citation2014; Rosset & Pfister, Citation2013). For instance, Rosset and Pfister (Citation2013) acknowledge the role of innovative electoral administration in conflict mitigation. Golden et al. (Citation2014, p. 1) posit that “…electronic voting machines, polling station webcams and biometric identification equipment, offer the promise of rapid, accurate, and ostensibly tamper-proof innovations that are expected to reduce fraud in the processes of registration, voting or vote count aggregation”. Biometric identification machines authenticate the identity of voters by using biometric markers such as fingerprints that are almost impossible to counterfeit. These technologies are particularly useful in settings where governments have not previously established reliable or complete paper-based identification systems for their populations (Gelb & Decker, Citation2012).In this article, we build on these discussions that acknowledge the role of digital technology in electoral administration; drawing essentially from the Nigerian frame of reference. We argue that while the use of the biometric technologies did not entirely make the elections free and fair, they however, accounted for their credibility. Despite challenges, especially in fingerprint verification, the card readers contributed in curbing traditional electoral frauds. Thus, we investigate the role of SCR in improving the credibility of the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria. As shall be seen, this has become mostly evident in building the confidence of relevant stakeholders in Nigeria’s elections as well as in the general reduction in post-election litigations in the country. In the next section, this article discusses the methodological underpinning of the study. This covers both the method of data collection as well as the theoretical framework of analysis, which centres on the cybernetics model of communications theory.

2. Methodology

This study is a qualitative research. It relied basically on the documentary method of data collection as well as field observation during the 2015 General Elections. The documentary method is concerned with the analysis of documents that contain information about a given phenomenon under investigation. According to Payne & Payne (as cited in Mogalakwe, Citation2006, p. 221), “documentary method is the technique used to categorize, investigate, interpret and identify the limitations of physical sources, most commonly written documents whether in the private or public domain”. The method is often considered a monopoly of professional historians, librarians and information science specialists. Hence, it is largely under-utilised and often considered a subsidiary research method in the social sciences. As Kridel (Citationn.d.) argues,

the documentary milieu as a form of archival inquiry seems most pronounced in the area of history with many curriculum historians working extensively with primary documents. Ironically, within the tradition of the social sciences and the field of qualitative research, with its emphasis upon generating data through various means of inquiry, the use of extant documents from the past and present seem somewhat overshadowed (http://www.aera.net/SIG013/Research-Connections/Introduction-to-Documentary-Research).

However, it must be emphasised that the seeming under-utilisation of this method in the social sciences does not make it less rigorous and scientific because it also adheres to the tenets of scientific protocol. Sources of documentary research include historical documents such as laws, declarations, statutes and people’s accounts of events and periods. They also include reports based on official statistics as well as governmental records, mass media, literary texts, drawings and personal documents such as dairies and biographies. The methodological significance of this tool cannot be over-emphasised. It is usually applied to obtain in-depth information, concept/variable clarification to facilitate instrument design and to conduct pilot studies (Biereenu-Nnabugwu, Citation2006). This data gathering technique enables access into the inner recesses of group life, organisational structure, bureaucratic processes as well as the motivations for individual behaviour. According to Johnson and Joslyn (Citation1995, pp. 251–255), documentary method of data collection has the following advantages:

It allows the researcher access to subjects that may be difficult or impossible to obtain through direct personal contact, because they pertain either to the past or to phenomena that are geographically distant.

The use of data gleaned from archival sources is usually important because raw data are often non-reactive. In other words, those writing and preserving the records are in most cases unaware of any future research goal or hypothesis or, for that matter, that the fruits of their labour will be used for research purposes at all. However, record keeping is not always completely non-reactive. Record keepers are less likely to create and preserve records that are embarrassing to them, their friends, or their bosses; that reveal illegal or immoral actions; or that disclose stupidity, greed or other demeaning attributes; or even in some cases, that have security implications.

Documentary method offers the access to records that have existed long enough to permit analyses of political phenomena over time.

Using a written record often enables the researcher to increase sample size above what would be possible through either interviews, questionnaires or other forms of direct observation.

Lastly but most importantly, documentary method of data collection often saves the researcher considerable time and resources. It is usually quicker to consult printed government documents, reference materials, computerised data, and research institute reports than it is to accumulate data ourselves through the survey methods.

The method was useful in identifying information gaps that needed to be filled, formulating the research problem, developing a theoretical framework and articulating the research methodology. This method enabled us to examine the wider literature on digital technology and election administration within the Nigerian frame of reference. The search for literature extended to various sources including scholarly publications, media reports, conference and workshop papers as well as official documents from relevant government agencies.

The mass of data generated were analysed using the qualitative descriptive method. This method moves farther into the domain of interpretation because effort is made to understand not only the manifest but also the latent content of data with a view to discovering patterns or regularities in them. Tables were used for further illumination of the issues in the discourse. The study also utilised the cybernetics model of communications theory through which deeper theoretical insights were elicited as shall be seen below. Consequently, the study was able to interrogate the role of SCR in improving the credibility of the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria.

3. The cybernetics model of communications theory

This study employs the cybernetics model of communications theory as a tool for analysing the role of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in general, and the card reader in particular, in curbing electoral fraud during Nigeria’s 2015 General Elections. The communications theory was developed through the pioneering research efforts of Louis Couffignal, John von Neumann, Norbert Wiener, McCulloch, W. Ross Ashby, Alan Turing, W. Grey Walter and Karl W. Deutsch. In the field of computer technology, cybernetics has become a conceptual relic of communications theory. The significance of Deutsch’s Nerves of government: Models of political communication and control lies in that it is the first attempt to formulate a fully developed theory of politics based on a communications model. He particularly introduced the techniques of cybernetics to the sphere of political analysis. However, it was Wiener’s work Cybernetics that gave the cybernetics model its analytic fervour. Wiener further popularised the social implications of the model, drawing analogies between automatic systems and human institutions in his work, The human use of human beings: Cybernetics and society.

Cybernetics is the branch of science concerned with the study of systems of any nature, which are capable of receiving, storing and processing information so as to use it for control. According to Gauba (Citation2003, p. 98), “cybernetics is the study of the operation of control and communication systems; it deals both with biological systems and man-made machinery”. Similarly, “the term cybernetics…covers not only the versions of information theory…but the theory of games, self-controlling machines, computers and the physiology of the nervous system” (Varma, Citation1975, pp. 432–3). The model is based on a multidisciplinary approach, which arose as an offshoot of the Eastonian systems analysis and seeks to explain how actions within a given system generate some changes in its environment (Nwangwu, Citation2015). Thus, “the system codes incoming information, recognises patterns, stores the patterns in its memory unit… recalls information on command, recombines information in new patterns, and applies stored information to problem-solving and decision-making” (Winner, Citation1969, p. 9).

According to Gauba (Citation2003), the problem of communication may be studied in three contexts: communication within the political system, communication between political system and its environment, and communication between two or more political systems. Its analysis involves the study of several components like: the structures meant for sending and receiving messages; the channels used for the purpose of communication (along with their capacities and rates of utilization, expressed in terms of their load and load capacity, rate of flow, amount of lag and gain, that is delay or promptness in responding to the information that is received); processes of storage of information; feedback mechanisms; the codes and languages applied for the purpose of communication, and the contents of the messages transmitted, and so on.

Arising from the foregoing, the basic assumptions of the model are:

It is information that triggers off the change in the suitable receiver, which can be compared with the information required for turning the gun to a particular target.

Society can only be understood through a study of the messages and the communications facilities, which belong to it (Wiener, Citation1948).

If the information flow is smooth and the decision-making system is in a position to respond and react to it in a constructive manner many problems can be resolved.

If governments are constantly looking for the communications channels and linking them up with information they are receiving, they will be able to do more than other governments, which are not aware of the existence of the working of these communications channels in the political system.

A political system goes through the process of innovation, growth and self-transformation when it moves beyond mere adaptation to drastic change, but it has to be extremely tactful both in supervising the mechanism it adopts for the change as well as the strategy with which it wants to bring about the change.

The growing complexity of the world has made the use of ICT for administrative purposes a desideratum. Accordingly, Winner (Citation1969, p. 3) argues that “in a world which has become increasingly complex and bureaucratised, ‘information’ may well provide a form of theoretical shorthand useful for the understanding of how regimes operate and how they tend to break down”. The twenty-first century has been generally characterised as the “electric” or “jet” age in order to underscore the pervasiveness of computer technology in different spheres of human existence. Hence, the practice of politics has increasingly involved the use of electronic mass media, mobile telephony and high-speed digital computers. As an activity in which men and machines participate hand-in-circuit, it is not surprising that the cybernetics model should become plausible as a basis for understanding electoral democracy. Men, machines, and political units all dispose of information from their environments in essentially the same manner. They act on certain varieties of messages and reject others. Progress has now been greatly accelerated by the use of digital computers as a new instrument for stating and testing theories. One of the earliest studies on voting decisions where the cybernetics model was applied is The American voter where Angus Campbell led other researchers to give sophisticated accounts of how computer technology influences electoral processes.

It is pertinent to note that this model is designed to elucidate an understanding of the desirability of achieving credible electoral democracy within the electronic womb of computer technology. Thus, advances in ICT, especially through various social media platforms, appreciably improved the transparency and credibility quotient of the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria. Through Facebook, Twitter, Blackberry Messenger, YouTube, Skype, GSM, SMS, among others, many voters, especially the youths, were mobilised and sensitised on the need for registering, collecting their PVCs and actually voting for candidates of their choice. Moreover, these platforms were used to frustrate criminal attempts to disrupt elections in polling units and collation centres. Thus, relying on election rigging is becoming both obsolete and increasingly difficult, as social media and mobile telephony are breaking down the walls that aided electoral malfeasance in the recent past. More significantly, the use of the digital, computer-based authentication device, SCR, for verification of the biometric PVCs, accreditation of voters and counting of votes during the elections, boosted the overall credibility of the exercise, restored the confidence of most Nigerian voters and international partners in INEC and accounted for a significant reduction in the volume of election petitions filed at the tribunals. In the next section, we overviewed various incidences and gradations of electoral fraud since the return to civil rule on 29 May 1999.

4. Overview of electoral fraud in Nigeria since 1999

The return to civil rule in Nigeria on 29 May 1999 is a product of two futile attempts by Generals Ibrahim Babangida and Sani Abacha to transit to democracy. The process for conducting the 1999 General Elections and the overall outcome were more acceptable and relatively less outrageous than the successive elections of 2003, 2007 and 2011. Although there were isolated sharp practices and irregularities as reported by Transition Monitoring Group (TMG), the Carter Center, National Democratic Institute (NDI), International Republican Institute (IRI) and the European Union Election Observer Mission (EU-EOM), the Alliance for Democracy and the All Peoples Party candidates could not mobilise substantial evidence to reverse the trend.

Nonetheless, the situation during the 2003 General Elections was markedly different. The elections were replete with irregularities and violence. Both domestic and international election observers in their various reports admitted that there were massive electoral malpractices during the general elections. The presidential candidate of the All Nigerian Peoples Party, General Muhammadu Buhari, described the elections as the most fraudulent Nigeria had had since independence and, therefore, called for their cancellation and the constitution of interim government to take over from 29 May 2003 (Odeh, Citation2003). Other electoral misconducts perpetrated by INEC and its unscrupulous officials include unlawful possession of ballot papers and boxes, unlawful possession of authorised/unauthorised voters’ cards, stuffing of ballot boxes, forgery of results, falsification of result sheets, tampering with ballot boxes, collusion with party agents to share unused ballot papers for fat financial rewards and inconsistent application of INEC’s procedures across the country (Ezeani, Citation2005).

The declining quality of Nigerian elections is a threat to democratic consolidation. The 2007 General Elections were the third in the series that map Nigeria’s democratisation since 1999. The elections offered another opportunity for change and power turnover in the country. However, judging by the overall quality and outcomes of the elections, the expectations of many Nigerians and international partners were dashed. The elections were marred by massive irregularities as reported by different accredited election observers like the TMG, The Carter Center, NDI, IRI and EU-EOM. The results of the elections were bitterly contested in an unprecedented but largely non-violent manner. Thus, Aiyede (as cited in Omotola, Citation2010, p. 549) argues that “from the conduct of the elections alone, 1,250 election petitions arose. The presidential election had eight, the gubernatorial 105, the senate 150, the House of Representatives 331, and the State Houses of Assembly 656”. With a few exceptions, especially the gubernatorial elections in Ekiti and Osun States, most of these cases were decided in the final appellate court. For example, the two leading opposition candidates in the presidential election pursued their cases to the Supreme Court where the case was decided in favour of President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). However, results were annulled in several states and at different levels, including the gubernatorial elections in Adamawa, Edo, Ekiti, Kebbi, Kogi, Ondo and Sokoto States. In most of these cases, a re-run was conducted, which the PDP won, save for Edo and Ondo States where declaratory judgments were given, leading to the restoration of the electoral victory of the Action Congress and Labour Party in the respective states.

The maladministration of the 2007 General Elections intensified civil activism for electoral reform and pressured the government to grant some limited concessions. Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), pro-democracy forces and opposition political parties fought relentlessly for a comprehensive reform of the electoral system. For example, the Electoral Reform Network and the Centre for Democracy and Development—shining examples of credible election advocacy groups—submitted memoranda to the Mohammed Uwais Electoral Reform Committee and also followed them up in the National Assembly (Omotola, Citation2010). The changes in the leadership of INEC, especially the removal of the controversial and discredited Maurice Iwu and his replacement with Professor Attahiru Jega (a leading political scientist, trade unionist and pro-democracy activist) are some of the gains of the Uwais reform process.

Arising from the implementation of the electoral reform by Yar’Adua/Jonathan administration, the 2011 General Elections were relatively credible, free and fair. Preparation for the elections began as far back as August 2009 with a strategic retreat by INEC in Abuja. This came against the backdrop of a number of challenges that confronted the Commission. One of these was the credibility gap, especially those that arose from the conduct of the 2003 and 2007 General Elections. To overcome these challenges, the first step taken by the Federal Government was to build public confidence on the credibility of the 2011 elections through the appointment of Professor Jega as the new INEC helmsman. The Commission also improved the conduct of the elections, creating a new voters’ register, improving transparency in reporting results, and publicly pledging to hold accountable those who broke the rules (Oladimeji, Olatunji, & Nwogwugwu, Citation2013). Elections were held in most areas of the country in a largely peaceful atmosphere, with fewer reported incidents of violence or blatant police abuses than in previous years. Despite the improvements, there were still incidents of violence, reports of police misconduct, voter intimidation, hijacking of ballot boxes by party thugs, ballot box stuffing, vote buying, multiple voting, over voting, underage voting, falsification of results and other associated electoral irregularities (Oladimeji et al., Citation2013). The outcome of the presidential election also led to the eruption of post-election violence with the attendant destruction of valuable lives (including those of some members of the National Youth Service Corps) and property in states like Bauchi, Gombe, Kaduna, Kano, among others. Corroborating the above, the National Democratic Institute (NDI, Citation2015, p. 6) holds that “the violence…caused over 800 deaths and substantial destruction of property”. It is pertinent to note that the outbreak of violence was not only as a result of poor handling of the elections by INEC but also a practical expression of frustration and disappointment, as well as a demonstration of the “do or die” attitude of the political elite to electoral contests. Utterances of some of the losing candidates and the general inability of politicians to accept defeat did not help matters (Ikeanyibe, Ezeibe, Mbah, & Nwangwu, Citation2018). Thus, CitationIndependent National Electoral Commission (INEC, n.d., p. iv) surmises that “the painstaking approach to the 2015 General Elections is informed by its perception that the 2011 polls, though qualitatively better than many previous elections, was by no means perfect”. In the next section, we shall investigate how the SCR improved the credibility of the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria.

5. Smart card reader and the credibility of the 2015 general elections in Nigeria

The 2015 General Election in Nigeria was the 5th quadrennial election to be held since the end of military rule in 1999. The successful conduct of the 2011 General Elections marked a watershed in Nigeria’s democratic trajectory, as it contrasted sharply with the mismanagement and widespread fraud of previous polls. At the end of the voter registration exercise in 2011, INEC had claimed that a total of 73 million Nigerians had registered, from which the Automated Fingerprint Identification System had removed 800,000 persons for multiple registration (Aziken, Citation2015). Thus, determined to improve the outcome of the 2011 polls, INEC introduced technological innovations, which were used to curb electoral fraud. These included a biometric PVC and card reader machine used to verify the authenticity of the PVC, and also carry out a verification of the intending voter by matching the biometrics obtained from the voter on the spot with those stored on the PVC (Orji, Citation2017). The 2011 voters’ register—Nigeria’s first electronically compiled register—helped in the production of the PVCs that were used in the 2015 General Elections. The card reader is designed to read biometric information in the embedded chip of the PVC. It displays voters’ names and facial images and authenticates their fingerprints. The deployment of the device ensured that each elector voted only in the registration area and polling unit where he or she was registered. Although technology does not offer a solution to all forms of electoral malpractice, the use of the SCRs made it more difficult to brazenly rig the 2015 General Elections.

On 7 March 2015, INEC test ran the reliability of the biometric technology in 225 out of a total of 120,000 polling units, and 358 of the 155,000 voting points that were used for the elections (Idowu, Citation2015). The test run of the device took place in 12 states namely: Delta and Rivers (South-South), Kano and Kebbi (North-West), Anambra and Ebonyi (South-East), Ekiti and Lagos (South-West), Bauchi and Taraba (North-East) as well as Nasarawa and Niger (North-Central). While acknowledging the challenges of the device in confirming fingerprints, the Commission expressed satisfaction that the basic duty of the card reader, that is, to authenticate the genuineness of PVCs, was in almost all cases achieved. According to a press release by Mr Kayode Idowu, the Chief Press Secretary to INEC Chairman, the decision to deploy SCRs for the 2015 General Elections has four main objectives:

To verify PVCs presented by voters at polling units and ensure that they are genuine, INEC-issued (not cloned) cards. This objective was achieved 100%.

To biometrically authenticate the person who presents a PVC at the polling unit and ensure that he/she is the legitimate holder of the card. In this regard, there were a few issues in some states during the public demonstration. Overall, 59% of voters who turned out for the demonstration had their fingerprints successfully authenticated.

To provide disaggregated data of accredited voters in male/female and elderly/youth categories, a disaggregation that is vital for research and planning purposes, but which INEC until now had been unable to achieve. The demonstration fully served this objective.

To send the data of all accredited voters to INEC’s central server, equipping the Commission to be able to audit figures subsequently filed by polling officials at the polling units and, thereby, be able to determine if fraudulent alterations were made. The public demonstration also succeeded wholly in this regard (Idowu, Citation2015, http://inecnigeria.org/inecnews).

As a consequence of the 41% failure rate in (ii) above, the Commission, in agreement with registered political parties, provided that where biometric authentication of a legitimate holder of genuine PVC became problematic, there could be physical authentication of the person and completion of an Incident Form, to allow the person to vote.

Responding to opposition to the use of the biometric technology, the Publicity Secretary of the then leading opposition party—All Progressives Congress (APC)—Alhaji Lai Mohammed, notes that:

Nigerians have sacrificed all they can to obtain their PVCs, which are now their most-prized possession. They have also hailed the plan by INEC to use the card reader to give Nigeria credible polls. Only dishonest politicians, those who plan to rig, those who have engaged in a massive purchase of PVCs and those who have something to hide are opposed to use of the machine (Adeyemi, Abubakar and Jimoh, Citation2015).

In corroboration, Professor Jega (as cited in Oche, Citation2015) maintains that it was only those that hitherto nurtured plans to fraudulently manipulate the outcome of the elections that were crying foul over the introduction of the technology.

As observed earlier, the use of the biometric machine during the elections was characterised by malfunctions. These ranged from limited or non-verification of voters’ fingerprints even after authenticating their PVCs; slow accreditation process as a result of poor internet server operations in some locations; to inadequate knowledge of the use of card readers by both INEC officials and voters. These hitches were more rampant during the March Presidential and National Assembly (NASS) elections because some of the polling officials were handling the machine for the first time and failed to peel off the nylon film covers of the lenses to enable accurate biometric reading. Thus, the 28 March elections were characterised by situations whereby:

electronic readers of biometric PVCs failed to verify fingerprints in many instances and resulted in delays in voter accreditation in a high number of polling stations. Where fingerprint scanning failed, there did not appear to be uniform understanding of contingency planning among polling officials, including requirements for large-scale manual verification of voters’ identities against the printed voter registry and the issuance of Incident Forms. When Incident Forms were diligently completed by INEC officials, accreditation was often delayed even further due to the time required to fill out a form for each voter whose fingerprints could not be read (NDI, Citation2015, p. 3).

Generally, problems observed with the SCR during the 2015 General Elections include rejection of fingerprint and even PVCs, especially those brought from other polling units (the rejections were mostly among the elderly); cases of SCRs not working at all; delays in using the SCR in some polling units; network failure; and cases where voters’ pictures did not appear on the card. Others are slow functioning of some SCRs while others did not pick up on time; some cards were not very sensitive to thumbprints while others rejected their passwords initially; cases of low battery strength and in some instances the batteries were completely drained; cases where the SCR did not correspond with the manual; some SCRs stated card mismatch information; some of the cards had incorrect settings; and during the governorship and State House of Assembly (SHA) elections, some card readers still retained data from the 28 March elections (Election Monitor, Citation2015).

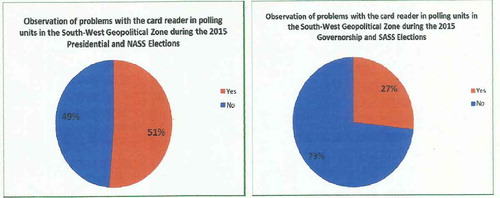

Most of these hitches characterised the presidential and NASS elections. The INEC as an institution improved significantly from the 28 March to the 11 April elections in the area of logistics, materials provision and mastery of biometric technology by polling officers. The Commission was able to correct its mistakes of 28 March to deliver freer, fairer and more credible governorship and SHA elections. With particular reference to the South-West geopolitical zone, the failure rate of SCRs dropped significantly after the Presidential and NASS Elections, as shown in Figure .

While the use of the biometric technologies did not make the elections entirely free and fair, they did, however, account for their credibility. Despite challenges, especially in fingerprint verification, the card readers contributed to curbing electoral fraud. In his post-election assessment, Professor Jega maintains that:

we have made rigging impossible for them (electoral fraudsters) as there is no how the total number of votes cast at the polling unit could exceed the number of accredited persons. Such discrepancy in figures will be immediately spotted. This technology made it impossible for any corrupt electoral officer to connive with any politician to pad-up results. The information stored in both the card readers and the result sheets taken to the ward levels would be retrieved once there is evidence of tampering (Oche, Citation2015).

The credibility of the elections, arising from the use of the anti-rigging technology, can also be deduced from the fact that this is the first time in the electoral annals of Nigeria that candidates would concede defeat and call to congratulate the winners. This happened first at the national level when President Goodluck Jonathan called to congratulate General Muhammadu Buhari on 31 March 2015. This exemplary conduct was emulated by defeated PDP governorship candidates in Niger, Benue, Adamawa, Lagos, Kaduna and Oyo States. It was also the first time so many incumbent governors would lose their senatorial ambitions to opposition party candidates. This happened in Adamawa, Bauchi, Benue, Kebbi and Niger States.

Moreover, contrary to the suggestion that “the country is heading towards a very volatile and vicious electoral contest” (International Crisis Group, Citation2014, p. i) and CLEEN Foundation’s 2014 report that 15 states in Nigeria were most volatile and prone to electoral violence, there was no pronounced violence anywhere, except in Rivers and Akwa Ibom States. The elections in the entire Northern and South-Western Nigeria were generally peaceful. In their reports, observer missions deployed from, among others, the African Union (AU), Commonwealth of Nations, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the EU, also attested to the credibility of the elections. As shown in the next section, these digital devices have strengthened the confidence of development partners and other stakeholders in Nigeria’s elections.

6. Digital technology and confidence building among stakeholders in Nigeria’s elections

As has been shown earlier, prior to the 2011 General Elections, election administrations in Nigeria were fraught with monumental electoral irregularities. In the run-up to the 2015 General Elections, many Nigerians and international development partners expressed doubts about the capacity of INEC to successfully conduct transparent, free, fair and credible elections. These doubts were necessitated by the prevalence of incendiary utterances and calumnious documentaries that targeted the personalities of the leading presidential candidates during the electioneering period. The bellicose rhetoric and hate speeches were seen as a harbinger of election-related violence (Ikeanyibe et al., Citation2018; Mbah, Nwangwu, & Edeh, Citation2017). Thus, in their separate reports, the International Crisis Group, CLEEN Foundation and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) predicted gloomy electoral outcomes for the country. In particular, the Foundation reported that Adamawa, Benue, Borno, Ebonyi, Ekiti, Enugu, Imo, Kaduna, Nasarawa, Osun, Plateau, Rivers, Taraba, Yobe and Zamfara States were most volatile and prone to violence (CLEEN Foundation, Citation2014). On the other hand, National Human Rights Commission (Citation2015, p. 6) reported that “Lagos (South-West), Kaduna (North-West) and Rivers (South-South) States present the three most worrying trends and locations predictive of a high likelihood of significant violence during the 2015 elections”.

Nonetheless, the above-average performance by the security agencies, the success of civic education and of course the introduction of biometric devices by INEC built confidence and a positive disposition of Nigerians, Election Observer Mission (EOMs) and development partners in the capacity of the Commission. The disposition of many Nigerian voters towards the novel anti-rigging technology was amply demonstrated through their level of participation during the elections. This confidence was based on their conviction that their votes would not only be counted, but actually did count. In its report, the NDI (Citation2015, p. 2) notes that:

the elections highlighted strong and enthusiastic commitment of Nigerians to democratic processes and the possibility of determining the leadership of the country through peaceful, transparent and credible elections….Nigerian voters conducted themselves in a peaceful and orderly manner on election days and politicians across the spectrum should recognize and respect this public manifestation of citizens’ commitment to the democratic process.

Although voters’ turnout varied across different geo-political zones and polling units in the country, there were long queues of enthusiastic voters who conducted themselves in a largely peaceful manner. In many instances, during the period before the arrival of poll workers and materials, citizen volunteers organised the crowd by handing out slips of paper with numbers in the order in which voters arrived, so as to facilitate crowd control and orderly conduct once the accreditation process began (NDI, Citation2015). The report also indicates that a high number of women and youth were well represented in voting lines on election days. In most cases, special consideration was given to pregnant and nursing women, the aged and persons with disabilities in order to facilitate speedy accreditation and voting. In those polling sites in which card readers did not properly capture fingerprints, voters remained generally patient and calm. Even among those who were displaced through the coordinated attacks of Boko Haram insurgents in Adamawa, Borno and Yobe States, the desire to participate in the electoral process remained resonate. According to Election Monitor (Citation2015, p. 82):

States with the highest voter turnout were Akwa-Ibom, Rivers, Bayelsa, Delta and Jigawa all having above 60% voter turnout. The state with the lowest voter turnout was Lagos State. Other states with relatively low turnout of voters are Ogun, Edo, Anambra, Abia, Kogi, Borno and FCT (30 to 39%). The national average voter turnout is 47% when considering those who came out for accreditation.

Table shows the overall voters’ turnout from the 36 states of the federation and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) during the 2015 Presidential and NASS Elections.

Table 1. Voters’ turnout from the 28 March 2015 presidential and NASS elections

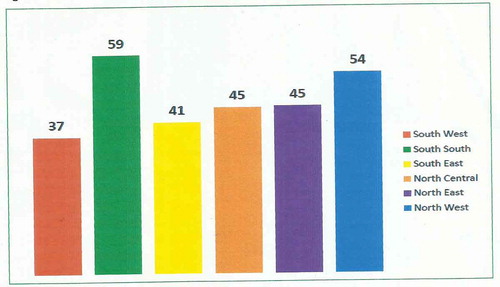

Election Monitor further reports that on a geo-political zone basis, the South-South had the greatest voter turnout with 59%, closely followed by the North-West with 54%. The South-West had the lowest turnout in the country with just 37%. Figure shows the percentage of voters’ turnout per geo-political zone. Predictably, the regions that produced the two leading presidential candidates had the two highest levels of voter turnout. The average national voter turnout in the 2015 General Elections was 47%. In relation to the average voter turnout of 52.2%, 64.8%, 57.2% and 52% for 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2011 respectively, it is evident that voter turnout has been falling while voter registration has been increasing. However, figures for previous voter turnouts are inaccurate due to the fraud and manipulation that characterised the elections.

Moreover, reports from accredited domestic and international EOMs unanimously described the elections as peaceful and generally credible. The observers attributed the credibility of the elections to, among others, the INEC’s insistence on the use of the PVCs and SCR for the elections. They particularly applauded Nigerian voters for their maturity, orderliness and commitment towards the success of the polls. According to the Commonwealth EOM’s report, the elections mark an important step forward for democracy in Africa’s most populous country and a key member of the Commonwealth. Notwithstanding the organisational and technical deficiencies, the conduct of the elections was generally peaceful and transparent (Ndujihe & Kumolu, Citation2015). In the same vein, the former Ghanaian President and Head of the ECOWAS EOM, Mr John Kufuor, reported that Nigeria’s feat with regard to the elections is a pride not only to Nigerians, but also to West Africa and the whole of the African continent. Similarly, the United States Government noted that the peaceful conduct of the elections had demonstrated to the world the strength of Nigeria’s commitment to democratic principles. By turning out in large numbers, and sometimes waiting all day to cast their votes, Nigerians have come together to decide the future of their country peacefully (Adamu, Citation2015). President Barrack Obama particularly praised INEC and Professor Jega for what independent international observers deemed largely peaceful and orderly elections. Thus, the president of Voters’ Awareness Initiative, Wale Ogunade, surmises that the INEC Chairman and his team have gained 80% confidence of Nigerians as a result of the deployment of a technology-based approach in handling the elections (Sunday Independent, 26 April 2015).

As a corollary, the three principal genres of development partners that work with INEC, through their EOMs, equally affirmed the credibility of the elections. These development partners as shown in Table are embassies and high commissions, multilateral development agencies, and foundations. These partners have assisted the INEC in the pursuit of its onerous primary objective of conducting free, fair and credible elections. The bulk of support from them is found in four main areas, namely: technical assistance, training support, experience sharing and support for retreats.

Table 2. Classification of INEC’s development partners

The EOMs’ unanimous acclamation of the outcome of the 2015 General Elections indicate that these international development partners now have more confidence in INEC and Nigeria’s elections. As a result, they are also keener to partner with INEC in order to ensure that future elections in the country are truly free, fair and credible. Moreover, some of these development partners demonstrated their goodwill to Nigeria through the request of the Group of Seven (G-7), an informal bloc of most industrialised countries. They asked the President-elect, General Muhammadu Buhari, to prepare a wish list for consideration during their 41st Summit held in Bavaria between 7 and 8 June 2015. Thus, the outreach programme for invited heads of governments and global institutions offered President Buhari the opportunity to meet with Angela Merkel, Barrack Obama, Francois Hollande, David Cameron, Stephen Harper, Shinzo Abe, Jim Yong Kim, Ban Ki Moon, Angel Gurria, Christine Lagarde and Guy Rider of Germany, USA, France, UK, Canada, Japan, the World Bank Group, the United Nations, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the International Monetary Fund and the International Labour Organization respectively. Needless to say, this gesture is a demonstration of the confidence these partners have in the electoral process that produced the present government in Nigeria. In the next section, we discussed how the deployment of digital technology accounted for the general reduction in post-election litigations in 2015.

7. Digital technology and general reduction in election petitions

Elections in Nigeria are coterminous with brinkmanship and legal fireworks. Post-election dispute resolution is, therefore, a key activity, which brings final closure to the electoral process. Both the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and the Electoral Act 2010 create the necessary ambience for election petition tribunals to adjudicate on petitions filed by complainants against the conduct of elections. Thus, the court is the only institution after INEC that can determine the winner of an election, or review and reverse the pronouncement of the returning officer on a poll.

Prior to the 2015 General Elections, the then Chief Justice of Nigeria, Mahmud Mohammed, inaugurated 242 judges who were selected to serve at various election petition tribunals. In constituting the tribunals, the Chief Justice was obviously envisaging the likelihood of aggrieved candidates and parties seeking judicial redress. Under section 134 of the Electoral Act 2010, all petitions must be filed within 21 days of the declaration of the result of an election. Unlike the 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2011 General Elections, the 2015 elections have witnessed a general reduction in election litigations. The total number of petitions filed after the 2003 General Elections was 560. By 2007, the petitions increased to 1,290. A total of 731 elections petitions were filed at the various Election Petition Tribunals across the Federation after the 2011 General Elections (INEC, Citationn.d.) However, the electoral reforms of the Yar’Adua/Jonathan administration largely accounted for the significant reduction in petitions filed in 2011 to 731. Table summarises all the elections petitions filed after the 2011 elections.

Table 3. Summary of the 2011 election petitions

Although data on the exact number of petitions filed at the tribunal after the 2015 General Elections is sketchy, indications are that there is a significant reduction across the country. Following the expiration of the 21 days statutorily allowed for petitions after the declaration of results, there was no petition filed at the Presidential Election Petition Tribunal (Appeal Court) which has original jurisdiction according to section 239 (1) (a) of the Nigerian Constitution. This is a radical departure from the past elections of 2003, 2007 and 2011 in which the results of the presidential elections were contested from the Appeal Court to the Supreme Court. President Jonathan of the PDP conceded defeat and congratulated General Buhari on 31 March 2015. Arguably, this is a mark of confidence in the credibility of the elections, which witnessed significant reduction in electoral fraud.

This exemplary conduct of President Jonathan was emulated by many defeated PDP governorship and NASS candidates in States like Adamawa, Benue, Kaduna, Lagos, Niger and Oyo among others. Unlike in the 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2011 elections, there was no avalanche of electoral petitions in 2015. However, some governorship, national and state assembly candidates filed petitions at the various designated tribunals. A breakdown of the petitions shows that the South-South and South-East geopolitical zones recorded the highest cases of 95 and 93 petitions respectively. Delta State tops the chart in the South-South with 40 petitions, while Imo takes the lead in the South-East with 38 cases (Mac-Leva & Ibrahim, Citation2015). There is virtually no petition from the entire North-West while North-East and North-Central have fewer than 30 petitions each. This differential must be understood in the context of a massive failure by the SCR to read biometric information contained in the PVCs and to accredit voters in Southern Nigeria. This made the use of manual accreditation inevitable in these regions. Similarly, electoral violence was more pervasive in these areas, especially Akwa-Ibom and Rivers States. Table shows the volume of election petitions from each zone following the expiration of the 21 days statutorily allowed for petitions after results are declared.

Table 4. Election petitions from each zone after the 2015 general elections

8. Conclusion

This article investigated the role of SCR in improving the credibility of the 2015 General Elections in Nigeria. Using the cybernetics model of communications theory, it found that the deployment of SCR had rekindled the confidence of many Nigerian voters and those of development partners in INEC and Nigeria’s elections. It found that while the use of biometric technologies did not entirely make the elections free and fair, they however, accounted for their credibility. Despite challenges, especially in fingerprint verification, the card readers contributed in curbing pervasive electoral fraud. Consequently, the outcome of the elections conduced to confidence building among relevant stakeholders as well as in the significant drop in the volume of election petitions filed by aggrieved candidates and political parties. This is because of the use of the digital device for organising voters (authentication of PVCs and accreditation of voters) and counting votes (validation of the total votes cast by querying the machine). The paper also found that the governorship, NASS and SHA petitions filed at the tribunals in Abia, Akwa-Ibom, Delta, Ebonyi, Imo, Rivers, Taraba, among others, were due to the general failure or non-use of the SCR for voters’ accreditation and PVC authentication.

Arising from the foregoing, INEC should maintain the usage of card readers in all subsequent elections. Despite the hiccups associated with the use of the machines, it is very important that they continue to be used in all subsequent elections. The 2015 General Elections show that technology has merit and is the way to go in future elections. Accreditation of voters should also be done simultaneously with voting. The reason for having accreditation and then voting is to prevent voters who wish to vote at more than one polling unit on election day from doing so. The card reader makes it impossible to be accredited in two places as it only works with the PVC specifically programmed for each polling unit. Thus, there is no major reason to continue separating the two activities as the card reader has addressed this issue. More fundamentally, INEC should embark on full implementation of e-voting and other technology-based approaches to election administrations. To achieve this, however, the Commission should work with the NASS to get section 52 of the Electoral Act 2010 amended. It is also important to test run the e-voting on smaller mid-season elections in Bayelsa, Kogi, Edo, Ondo, Anambra, Ekiti and Osun States before the main deployment of 2019 as only a phased implementation would give maximum impact.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chikodiri Nwangwu

Chikodiri Nwangwu is a lecturer at University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN) with a specialization in political economy. His research interests include election studies, security, regionalism, and gender and development. He is a member of NPSA and AROCSA. He has published well-researched articles in reputable journals, including Review of African Political Economy and Japanese Journal of Political Science. Email: [email protected].

Vincent Chidi Onah

Vincent Chidi Onah is a lecturer in the Department of Political Science, UNN. He holds a PhD in Public Administration. He has published well-researched articles in reputable journals. His research interests include public policy, development studies, elections, and peace and conflict studies. Email: [email protected].

Otu Akanu Otu

Otu Akanu Otu is a senior lecturer at Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu-Alike Ikwo, Ebonyi State. He holds PhD in Public Administration (Human Resource Management) from UNN. He has published in refereed journals. His research interests include public policy, human resource management, and election studies. Email: [email protected].

References

- Adamu, S. (2015, April 24). Appraising the success of 2015 elections. Leadership. Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://www.nigerianobservernews.com/2015/04/26/appraising-thesuccess-of-2015-election/

- Adeyemi, M., Abubakar, M., & Jimoh, A. M. (2015, March 5). PDP, APC trade words over use of card reader for polls. The Guardian. Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://www.ngrguardiannews.com/2015/03/pdp-apc-trade-words-over-use-of-cardreader-for-polls/

- Ake, C. (1985). The future of the state in Africa. International Political Science Review, 6(1), 105–114. doi:10.1177/019251218500600111

- Aziken, E. (2015, March, 12). Card readers: Lessons from other lands. Vanguard. Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://www.vanguardngr.com/2015/03/card-readers-lessons-from-otherlands/

- Barkan, J. (2013). Kenya’s 2013 elections: Technology is not democracy. Journal of Democracy, 24(3), 156–165. doi:10.1353/jod.2013.0046

- Biereenu-Nnabugwu, M. (2006). Methodology of political inquiry: Issues and techniques of research methods in political science. Enugu: Quintagon Publishers.

- Carlos, C. R., Lalata, D. M., Despi, D. C., & Carlos, P. R. (2010). Democratic deficits in the Philippines: What is to be done? Quezon City: Center for Political and Democratic Reform.

- Cheeseman, N., Lynch, G., & Willis, J. (2018). Digital dilemmas: The unintended consequences of election technology. Democratization, 25(8), 1397–1418. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1470165

- CLEEN Foundation. (2014). Security threat assessment: Towards 2015 elections. Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://www.cleen.org/2015%20Election%20Security%20Threat%20Assessment%20April%202014.pdf

- Diamond, L. (2008). The spirit of democracy: The struggle to build free societies throughout the world. New York: Times Books.

- Election Monitor. (2015). 2015 general elections observation report. Akure: Author.

- Evrensel, A. (2010). Introduction. In A. Evrensel (Ed.), Voter registration in Africa: A comparative analysis (pp. 1–56). Johannesburg: EISA.

- Ezeani, O. (2005). Electoral malpractices in Nigeria: The case of 2003 general elections. In G. Onu & A. Momoh (Eds.), Elections and democratic consolidation in Nigeria (pp. 413–431). Lagos: A Publication of Nigerian Political Science Association.

- Gauba, O. P. (2003). An introduction to political theory (4th ed.). New Delhi: Macmillan India Ltd.

- Gelb, A., & Clark, J. (2013). Identification for development: The biometrics revolution (Centre for Global Development Working Paper No. 315). Retrieved March 27, 2015, from https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/159149/1426862_file_Biometric_ID_for_Development.pdf

- Gelb, A., & Decker, C. (2012). Cash at your fingertips: Biometric technology for transfers in developing countries. Review of Policy Research, 29(1), 91–117. doi:10.1111/ropr.2012.29.issue-1

- Golden, M., Kramon, E., & Ofosu, G. (2014). Electoral fraud and biometric identification machine failure in a competitive democracy. Retrieved March 27, 2015, from http://golden.polisci.ucla.edu/workinprogress/golden-kramon-ofosu.pdf

- Ibeanu, O. O. (1993). The state and the market: Reflections on Ake’s analysis of the state in the periphery. Africa Development, 18(3), 117–131.

- Idowu, K. (2015). INEC statement on card reader demonstration. Retrieved March 15, 2015, from http://inecnigeria.org/?inecnews=inec-statement-on-card-reader-demonstration

- Ikeanyibe, O., Ezeibe, C., Mbah, P., & Nwangwu, C. (2018). Political campaign and democratisation: Interrogating the use of hate speech in the 2011 and 2015 general elections in Nigeria. Journal of Language and Politics, 17(1), 92–117. doi:10.1075/jlp.16010

- Independent National Electoral Commission. (n.d.). Report on the 2011 general elections. Abuja: Author.

- International Crisis Group. (2014). Nigeria’s dangerous 2015 elections: Limiting the violence. Belgium: Author.

- Johnson, J. B., & Joslyn, R. A. (1995). Political science research methods. Delaware: CQ Press.

- Kridel, C. (n.d.). An introduction to documentary research. Retrieved October 10, 2018, from http://www.aera.net/SIG013/Research-Connections/Introduction-to-Documentary-Research

- Mac-Leva, F., & Ibrahim, H. (2015, May 10). 2015 elections: 297 petitions taken to tribunals. Daily Trust. Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://www.dailytrust.com.ng/sunday/index.php/interview/20653-2015-elections-297-petitions-taken-to-tribunals

- Mbah, P., Nwangwu, C., & Edeh, H. (2017). Elite politics and the emergence of Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria. TRAMES: A Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 21(2), 173–190. doi:10.3176/tr.2017.2.06

- Mogalakwe, M. (2006). The use of documentary research methods in social research. African Sociological Review, 10(1), 221–230.

- Montjoy, R. S. (2010). The changing nature…and costs…of election administration. Public Administration Review, 70(6), 867–875. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02218.x

- National Democratic Institute. (2015). Statement of the national democratic institute’s international observer mission to Nigeria’s March 28 presidential and legislative elections. Abuja: Author.

- National Human Rights Commission. (2015). A pre-election report and advisory on violence in Nigeria’s 2015 general elections. Abuja: Author.

- Ndujihe, C., & Kumolu, C. (2015, May 2). 2015: Are the polls really credible, free and fair? Vanguard. Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://www.vanguardngr.com/2015/05/2015-arethe-polls-really-credible-free-and-fair/

- Nnoli, O. (2003). Introduction to politics (2nd ed.). Enugu: PACREP.

- Nwangwu, C. (2015). Biometric voting technology and the 2015 general elections in Nigeria. Paper presented at a Two-Day National Conference on The 2015 General Elections in Nigeria: The Real Issues organized by the Electoral Institute, at the Electoral Institute Complex, INEC Annex, Opposite Diplomatic Zone, Central Business District, Abuja on 27–28 July 2015 Retrieved from http://www.inecnigeria.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Conference-Paper-by-Chikodiri-Nwangwu.pdf

- Nwangwu, C., & Ononogbu, O. (2016). Electoral laws and monitoring of campaign financing during the 2015 presidential election in Nigeria. Japanese Journal of Political Science, 17(4), 614–634. doi:10.1017/S1468109916000268

- Oche, M. (2015, April 5). Elections: What difference did card readers make? Leadership. Retrieved May 12, 2015, from http://leadership.ng/news/423212/elections-what-differencedid-card-readers-make

- Odeh, J. (2003). This madness called election 2003. Enugu: SNAAP Press Limited.

- Oladimeji, A., Olatunji, A., & Nwogwugwu, N. (2013). A critical appraisal of the management of 2011 general elections and implications for Nigeria’s future democratic development. Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 2(5), 109–121. doi:10.12816/0001192

- Omotola, S. (2010). Elections and democratic transition in Nigeria under the fourth republic. African Affairs, 109(437), 535–553. doi:10.1093/afraf/adq040

- Orji, N. (2017). Preventive action and conflict mitigation in Nigeria’s 2015 elections. Democratization, 24(4), 707–723. doi:10.1080/13510347.2016.1191067

- Rosset, J., & Pfister, M. (2013). What makes for peaceful post-conflict elections? Berne: Swiss Peace.

- Varma, S. P. (1975). Modern political theory. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House PVT Ltd.

- Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Winner, L. (1969). Cybernetics and political language. Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 14, 1–17.

- Yard, M. (2010). Preface. In M. Yard (Ed.), Direct democracy: Progress and pitfalls of election technology (pp. 8–12). Washington, D.C: International Foundation for Electoral Systems.