Abstract

Poverty is a global phenomenon and is observed to be the greatest socioeconomic challenge of the twenty-first century, plaguing both developing and developed countries. For this purpose, several international poverty reduction strategies have been proposed and adopted in Africa. The rate and levels of poverty on the African continent, with particular attention given to the Sub-Saharan Africa is on the rise. The questions addressed in this paper are threefold: What are the challenges of international development strategies for poverty alleviation in local context? What are the contours to poverty measurement and conceptualization globally and in South Africa? How do we understand the unidimensional analysis of poverty and how it affects poverty reduction strategies? It uses existing statistics and research data from Statistics South Africa and other indexes cushioned with over 150 research papers to generate data for the paper. Theme and narrative analysis were used to analyse the data for this paper. In conclusion, the paper contends that the development initiatives implemented in most developing countries, especially in Africa, were unsuitable, where it neither took cognizance of structures, culture nor the dynamics of poverty on the African continent. Consequently, it complicated and compounded the woes of those in poverty in Africa. This is because the policies and programmes adopted tend to favour the West and its allies, the East and its allies, China and its allies, and local bourgeoisie and the elite, at the expense of the local people and those in poverty on the African continent.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The African continent has witnessed several implementation plans or development interventions to uplift its citizens from global partners and stakeholders. Over the past few years, this commitment to raise Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, has led to deepening poverty and a wider inequality rate, due to an increase in the number of the unemployed. The paper demonstrates that for the region (Sub-Saharan Africa) to achieve meaningful development, the region must be able to look inward for its own development, as Western initiatives have not produced the needed trajectory for development. Rather, it has placed the region on a trail of seeking shadows.

1. Introduction

Poverty is a global phenomenon and is observed to be the greatest socioeconomic challenge of the twenty-first century (Serageldin, Citation2000; Martin, Citation2007, p. 1; Ortiz-Ospina, Citation2017). It plagues both developed and developing nations (Ferreira, Lakner and Sanchez, Citation2017). However, it has the tendency of plaguing developing nation more as compared with developed nations (Ortiz-Ospina, Citation2017; Ravallion, Citation2014; Roser & Ortiz-Ospina, Citation2018). This has resulted to certain core challenges in government policies and programmes (Kenny, Citation2017). Some of the encumbrances in developing nations that limit the efficacy of government policies, projects and programmes may include but not limited to shortage in capacities of state structures and systems; weak capacity of government functionaries; policy ambiguity; inept leadership; deficient socio-economic policies; greed and corruption in government; and the general lack of fiscal discipline (Kenny, Citation2017; Ndaguba & Okonkwo, Citation2017; Ndaguba et al. Citation2018). In contrast, there are certain attributes in developed nations that tend to boost its advancement, namely, adequate systems and structures for accelerated development, vibrant public institutions, depoliticized public services, and the creation of varied forms of opportunities for social, cultural, political and economic development (ILO (International Labour Organisation), Citation2003; Jazaïry, Alamgir and Panuccio, Citation1992). Based on the systemic and institutional weakness in developing countries, poverty tends to be more residual there (see Figure ).

Figure 8. Number of social grants disbursed between 2000 and 2016

Figure 1. Comparative analysis of global poverty trends

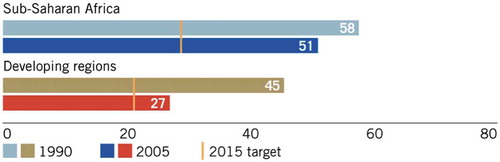

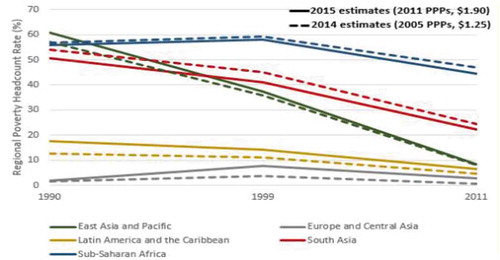

Figure reveals that in Sub-Saharan Africa the rate of poverty increased from 1990 to 1999, while the rate of poverty declined consistently between 2000 and 2011 (Ferreira et al., Citation2015). It must be noted that government policies, projects, interventions, initiatives or programme implemented for poverty alleviation within an epoch determines whether or not poverty will either increase or decrease. This is probably because government policies and programmes veer to anticipate an event (disaster) and strategize to put in place shock absorbers to reduce the number of casualties. Ferreira, Jolliffe and Prydz and the works of Max RoserFootnote1 are similar in many respects in this regard. In Max Roser’s global analogy of poverty 1820–2015, poverty has consistently been on the decline, although it disagreed that poverty was ever on the rise. On the contrary, according to Beegle and UNDESA, poverty levels in Sub-Saharan Africa are on the higher level (see Figure ) (Beegle, Christiaensen, Dabalen, & Gaddis, Citation2016; UNDESA: Africa Renewal, Citation2005).

Beegle et al. (Citation2016) argued that the rate of poverty in Sub-Africa is increased, especially when one takes into cognizance two of the continent dominant economic powers, Nigeria and South Africa, as illustrated in Figure (UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs), Citation2005; Beegie et al. Citation2016; StatsSA, Citation2017); however, for the purpose of limiting this paper only South Africa will be x-rayed in the Sub-Saharan African region. Sub-Saharan Africa comprises of 46 member countries of which South Africa is one (UNDP,Citation n.d.). South Africa is by far one of or the most advanced within the region, where social, infrastructural, political identity and human capacity development are concerned. The data obtained from Statistics South Africa (StatsSA) (Citation2017) revealed a declining trend of poverty between 2006 and 2009, which is in good agreement with that of Ferreira et al.; however, the rate of poverty increased between 2011 and 2015. This is in good agreement with the assertion of Beegie et al., where UNDESA presented no data (see Table ).

Table 1. Poverty measures by sex UBPL (2006–2015) (%)

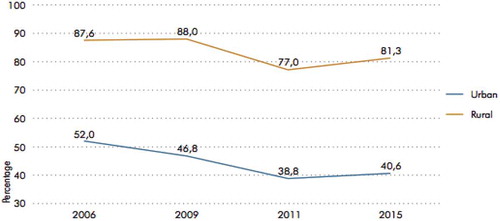

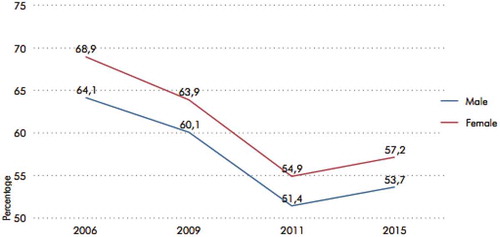

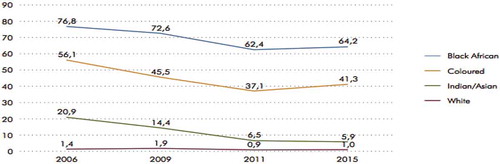

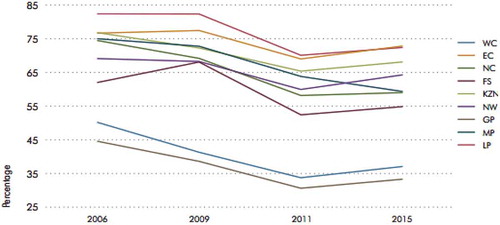

Grounded on the statistics from StatsSA (Citation2017, pp. 57–70) (see Figures –), poverty may be categorized into four categories in South Africa, namely, settlement type, gender-based, population group bound, and province bound. The categorization of poverty is useful for understanding and proffering remedial actions in tackling poverty based on the four categories. For example, a method adopted for poverty reduction in the Western Cape might have marginal effect in the Eastern Cape. For example, Figure demonstrates that there are higher concentrations of those in poverty in rural areas, and that women have greater chances of being in poverty than men (Figure ). Furthermore, black Africans are much more likely to be poor compared to other racial groups (Figure ). Furthermore, province like the Eastern Cape and others that are less economically viable are likely to be much poorer to other provinces. Hence, one may argue that provinces that are not economically viable create a state of uncertainty and vulnerability for its populace, and that location is a factor in poverty discourse. Therefore, to alleviate or reduce poverty in a country like South Africa, one may consider these four contours in poverty analysis (i.e., environment, location, gender, and population group) before poverty intervention.

It is therefore to this extent that this paper ponders on the following research questions that may guide further discussion in this paper: What are the challenges of international development strategies for poverty alleviation in local context? What are the contours to poverty measurement and conceptualization in South Africa? How do we understand the unidimensional analysis of poverty and how it affects poverty reduction strategies? This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 demonstrates the material and methods for deriving the analysis for this paper. Section 3 deals with the challenges of international development in a local context. Section 4 discusses the misfit of poverty analysis. Section 5 provides an analysis of the unidimensional poverty and poverty reduction reform in South Africa.

2. Material and method

In research, there is hardly any method that is considered sacrosanct, especially in social research. Although in social research there are two widely used methods for gathering information for conducting research, quantitative and at the extreme is qualitative. However, between both methods lies the mixed method, which is a combination of numbers and words, respectively. According to Ndaguba (Citation2018), there is no any best way for conducting social research. Hence, the research is dependent on the agility and ability of the researcher to gather synthesize and evaluate reasonable data for answering the research questions under review (Ndaguba, Citation2016, p. 12; Ndaguba et al., 2018). Writing a research methodology is at the centre of any scientific research endeavour, as its gives the reader an understanding as to how information were gathered and the system of analysis. Hence, it gives credence and determines to a large extent the feasibility of achieving both the aims and means in a study. In any case, where the research methodologies are questionable the entire research outcome is questionable.

The modality for gathering data for this paper was principally desktop with search engines as, Catalogue of theses and dissertation of South African Universities (NEXUS); Catalogue of books: Ferdinand Postma Library (North-West University); Chronic Poverty Index; EBSCO EconBiz; Food Agricultural Organisation Database; Google Scholar Index; Statistics South Africa; and World Bank Database. In essence, it has been argued that the bedrock of the desktop research is predominantly the ability to search for reasonable data, synthesize the quality of the data and ensure that the right amount of data are collected and analysed in tandem with the object or question of the paper.

This study adopts an exploratory design method in its analysis by identifying salient factors in poverty reduction from international to local parlance; it demonstrates some not all the reasons for the quagmire resulting in ineffectiveness of international practices for tackling poverty in local context. The desktop research approach used in this study is consistent with both the (quasi) quantitative and qualitative paradigm for collecting data. An average of 250 articles, books, Internet source, and government gazette and other documents were consulted. However, over a hundred of these materials were utilized in answering the research question in this paper.

3. Challenges of international poverty reduction strategies

There are several international poverty reduction strategies proposed and adopted by African countries; however, for the purpose of this literature review, only three of these poverty alleviation strategies will be considered and they include, policy framework and poverty reduction strategy papers (PRSPs), millennium development goals (MDGs), and the structural adjustment programmes (SAP). The Structural Adjustment Programme of the World Bank and others will take the lead.

4. Structural adjustment programmes (1980–1999)

At independence in most African countries, a socialist approach to development was adopted in which case government drives all aspect of economic development. This was at a time when there were global contestation between the West and America vs Russia and Cuba on the development response to Africa and the world. Where America and other Western countries offered capitalism as a response, Russia and Cuba offered communism and socialism as a panacea to individual wealth accumulation. The argument of the latter was that communal growth infers on individual growth and development in general; however, the former (capitalism) offered less government intervention and presence in social enterprise and investment and a liberal market for Africa’s economic development.

The exigencies of the time created a mixed feeling that threatened Africa’s economic growth of the 1970s, due to slow or stagnant economic growth, waning exports, declining social conditions, weak management of the public sector, increasing failures in institutional capacity, increasing debt, price distortion, wage cost, negative growth rates in productive sectors, and waning efficiency and levels of investment (World Bank, Citation1990; Heidhues et al., Citation2004). As a result of the adoption of localization and indigenization policies in virtually all colonial territories post-independence. This according to Heidhues and Obare (Citation2011) led to a high balance of payments, a high budget and cost to maintain state presence, and a significant debt burdens. It must be recognized that the stagnancy was barely two decades into the independence of most African countries (Heidhues and Obare, Citation2011, p. 55).

Africa from time immemorial has been seen as a test-tub for both new products and new philosophies. Therefore, it was only proper that those who hold access to finance play the big brother (such as sponsors of poverty alleviation strategies—International Monetary Fund, International financial Institutions, and the World Bank). It is within this context, that one must see the strategies for alleviating poverty sponsored by International Monetary Fund and the World Bank for economic growth and catch-up of developing countries. One of these strategies for catch-up and economic growth in Africa is the Structural Adjustment Programme, which was rectified by 33 independent countries in Africa in 1980. The idea of SAPs was to transform the stagnant and troubled economies of the African states. The idea “African must run while others walk” demonstrated the optimism of African leaders’ at the early years towards achieving economic sovereignty.

Leaders of the African states were largely influenced by the Prebish-Singer hypothesis “enduring long-term decline of international terms-of-trade in disfavor of primary products, notably food, adopted strategies that focused on industrialization as the engine of economic growth” (Heidhues and Obare, 2011, p. 56). This philosophy derives its strength from the notion of “cheaper by the dozen”, which led to greater woes in most African countries. The essence of this philosophy is to ensure that African leaders and its people prefer imported manufactured product to locally sourced goods and service. This idea of importation led to the institutionalization of Import-Substitution Industrialization (ISI) (Acemoglu et al., Citation2001; Acemoglu, and Robinson, Citation2012). There are two main points to note here, the first is that Africa’s productive capabilities and innovation were truncated, killed and stolen. And on the other hand, employment was thus transferred creating dependence on finished products and the preference for foreign products over locally produced goods were favoured. More worrisome, is that sectors such as, Agriculture and Mining were ascribed secondary role of supplying raw materials (Acemoglu et al., 2001), this has led to a situation whereby African states have resulted in buying the finished goods at a higher price rather than produce this goods locally.

Before, the recommendation and adoption by African leader of the SAPs, several continental strategies and plans for economic growth were disfavoured and rejected by the IMF, WB and the United States of America and Western donors, such as, the Lagos Plan of Action (LPA), and the Regional Food Plan for Africa (AFPLAN) (Heidhues and Obare, 2011, p. 56). Both the LPA and AFPLAN may be traceable to the Bandung Conference of 1955, whose major preoccupation was to build national bourgeois within developing countries and to solve economic conundrums by using local bourgeois.

In giving out the African continent to dinner table of the West, the Berg Report emanated in 1981, titled: Towards accelerated development in Sub-Saharan Africa. The report filled all the wish list of the West, the IMF and the WB, it attributed the blames of economic development to the style of leadership and the nature of the policies adopted by African governments. It took no cognizance of African initiative, culture and diversity or the ideas that birthed or truncated and sabotaged the continental models by the West among others. Rather, it gave a fair rendition to the admiration of the West and the Banks by marshalling seven reasons for the failures in economic growth trajectory in the Sub-Saharan Africa, namely, faulty exchange rate policies, the protection of inefficient producers, extraction of high rents from rural producers, general corruption, gross resource mismanagement, excessive state interventions, and unnecessary subsidization of urban consumers as a reason for stalled development. The core recommendation of the Berg report was capitalism as a means of accelerated economic development in Africa.

In a bid to save Sub-Saharan Africa from economic woes, Heidhues et al. (2004) argues that the core element of the SAPs were predominantly, anti-inflationary macroeconomic stabilization policies, free market development and private sector ownership, privatizing public sectors services and companies, eliminating subsidies and cutting support for social services, dissolving parastatals, and controlling government budget deficit (Nhema, Citation2015; Van De Walle, Citation1989). Also included as a plan for accelerated development of the region is, monetary devaluation and trade liberalization, debt-rescheduling, control of foreign indebtedness and stricter debt management were part of the programmes policy toolkit for economic development (Heidhues and Obare, 2011, p. 58; South African Reserve Bank, Citation2013). Although, in most Western countries (America inclusive) government tends to control to some extent market determinants, the financial markets and free trade is illusive. Social services are provided in forms of social security, government ownership of key market determinant still exists in the twenty-first century. Yet for Africa to get loans through the adjustment programme every social structure has the propensity to lead towards greater wellbeing was erased from continent but strengthened in the West. This raises concerns, as, are the West, IMF and World Bank sabotaging the economic trajectory and development of Sub-Saharan Africa? Though one may argue that the adjustment programme did not perform to its optimum for three reasons, that government in the region paid half-hearted attention or incomplete implementation to the adjustment programme (World Bank, Citation2000), that inappropriate policy design and the lack of coordination played a critical part in the dysfunctional setup of the programme (Cornia and Helleiner, Citation1994; World Bank, Citation2000), and that there was an occasion between 1980s and 1990s that market for primary products deteriorated (Mkandawire and Soludo, Citation1999).

Therefore, the failures of SAPs to transforms the Sub-Saharan Africa economically may be summed up in the following, the lack of ownership, ineffectual consultation with stakeholders, the inhumanity and general insensitivity of the programme to locals. One may argue that while SAPs was a failure in the Sub-Saharan African region, it was a success in the West. In that, the idea of free market for Western goods and services to be consumed was established, the high dependency rate of African leaders on Western leaders was achieved, the remote control of the economies of African leaders by Western economies were also realized, higher indebtedness to Western economies was also established and realized, a shift from social approach to development to capitalist approach to development was realized. Therefore, one may conclude that the essence of the Structural Adjustment Programmes were not necessarily to alleviate poverty and set Africa on the path to economic freedom and development but to create greater dependence on the Western countries otherwise former colonial masters. Although, premised on several criticism from scholars and development practitioners the idea of SAPs were repelled and Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility was introduced, and later Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility before then Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility, these were replaced by the Policy Framework and Poverty Strategy Papers (PSRP), which is more or a less a neo-SAPs restructured agenda.

However, the framework for SAPs must not be blurred or fuzzy, in this light one may argue that between 1980 to 1999 five modalities or facility were predominantly used for granting loans to developing countries for poverty reduction by the IMF and the World Bank. These adjustment strategic initiatives may include, the Stand-By-Arrangement (SBA), which is usually a short-term loan within a year or two with higher conditionalities. The Extended Fund Facility (EFF) proposed for countries having severe disequilibria to meet their balance of payment. Structural Adjustment Facility (SAF) and Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF) are long-term loans usually above a 3-year spam, with lower conditionalities, although, programmes under SAF have lower conditionality for repayment than ESAF. However, ESAF was replaced in Citation1999 with the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF), which remains the largest means through which the IMF gives and services loans to developing countries (IMF, Citation2017). The idea for PRGF was to grant loans to countries with a lower interest rate, ensure that the process for the strategy papers are homegrown through consultation among others, which forms the basis for the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) (Garuda, Citation2000—Citation2010., p. 2).

5. Policy framework and poverty reduction strategy papers (PRSP) (1999—ongoing)

Emanating from the collapse, gross inefficiency, rejection and failure of the Structural Adjustment Programmes to set the developing world on the path of economic and human development, the Policy Framework and Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) was proposed and adopted by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank as a set of new of procedures for concessional lending to the poor and Highly Indebted Poor countries (Malaluari and Guttal, Citation2002, p. 2; Levinsohn, Citation2013, p. 1). The goal of the PRSP is three-fold, poverty reduction focused on government, ownership of the procedures and processes by independent counties and stakeholders, and civil society involvement in poverty reduction in developing countries derived from the Comprehensive Development Framework (Dijkstra, Citation2011: World Bank, Citation2004). Principally because, the PRSPs are sets of documents detailing requirements of the IMF, World Bank and Donor agencies for either debt or aid relief for the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) and low-income countries (Dijkstra, Citation2011),Footnote2 as well, it tends to describe the conundrums of poverty alleviation in developing countries, and proposed macroeconomic, social, and structural policies and programmes to reduce poverty (IMF, Citation2016). Been that SAPs did not take cognizance of the human aspect of development, which was a major flaw of the programme. According to Ingram in World Bank (Citation2004), PRSP is a major instrument of the IMF and the World Banks that leans towards using aid control and management as a means for reducing poverty in developing countries.

6. Legacy of mass poverty, conflict and failed state in Sub-Africa

The Sub-Saharan African region is located within the African continent; it has 46 member-states and over 1,050,135,841 billion people, representing 14% of the world population (World Population Review, Citation2018). Nigeria and Ethiopia are amongst the biggest in terms of population, but countries in the Southern Hemisphere are more economically stable viable, Botswana and South Africa. A majority of the citizens in this region are in poverty (see Figure ).

Figure depicts the nature of poverty during the period PRSP was established and the essence why at the time it seemed unavoidable, that the West and the Banks intended to boost economic development in developing countries. More so, it must also be noted that there is a relationship between conflict and mass poverty, and a situation where both are highly prevalent or occurring a failed state situation is inevitable. A state according to political theorist as Max Weber, is described a state as maintaining monopoly of its territorial confines (Weber, Citation1946, Citation2013). A failed state is a polity who’s economic and political system have been compromised and so have become so weakened that it could not technically maintain internal control of its activities, due to varying circumstances which may include but not limited to, paramilitary groups, dominant presence of warlords, and terrorism or armed gangs

This is probably because, a combination of conflict and mass poverty leads to a breakdown in law and order, which constitute a fundamental failure in the part of the government to provide social justice, social welfare, address social morbidity, and the general inability of a government to inadvertently assert authority over its people. In this respect, South Africa was considered a failed state before independence, Zimbabwe, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Kenya, Somalia, Central African Republic, Burundi, Guinea and Guinea Bissau, Chad, Liberia, Mali, Togo and several other Sub-African countries had been referred to as failed state at one time or the other and others are still referred to as failed state even today (Acemoglu, and Robinson, Citation2012; International Monetary Fund, Citation2014). As a result of heightened deficiencies and dysfunctional governance framework and social justice system, perilous road tracks and non-functionality of its production sectors, the educational qualifications are questionable, healthcare are in shambles, and a third of the 46 member-states are unable to generate its income for state functionality internally. The idea of failed or fragile state is summarized as underdevelopment, lack of education and employment opportunities, conflict and political instability, lack of inclusivity and common vision, and ineffective institutions and the weak governance (IMF, 2015—Ndaguba & Okonkwo, Citation2017). Furthermore, most government in Sub-Saharan countries are heavily dependent on the IFI in particular the IMF for loans to sustainably run its internal activities and meet its obligations as a sovereign state.

6.1. The myth and drills of PRSP

There are three widespread fairytale given by the IMF and the World Bank for concessional assistance accessing debt relief that academics needs to refute. These are the ideas of national ownership, pro-poor policies, and poverty reduction in itself.

7. The myth of national identity and ownership

From the prism of IMF and the World Bank, PRSPs presupposes an initiative that is country-driven and should reflects the primacies of each country in fighting poverty. The processes involved in the papers includes, consultation with civil society organizations, the private sector and the government. Pragmatically, the initiative was a mere theoretical postulation, in that, while in the draft reports submitted for getting concessional loans and debt relief to the HIDCs, the CSOs where frustrated all through the process and the private sector were largely ignored. Hence, Dembele (Citation2011) argued that CSOs were frustrated and used as a guinea pig or alibi in drafting the reports for poverty reduction in most African countries. Furthermore, since the IMF and the World Bank had a set of procedures before the grant and loans where received. Most African governments merely put in the PRSPs what the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWI) wishes to see rather than the reality of the state of poverty on the continent. Thus, the misleading analogy of Max Roser of poverty which demonstrate that the number of the poor is about 816 million (constituting 9% of the world population) (Roser, & Ortiz-Ospina, Citation2018), while poverty in Sub-Saharan African region alone is about 800 million, with a half of its children living in extreme poverty (Hodal, Citation2016)

As stated earlier, quantum of evidence are bound from Nigeria to Tanzania, South Africa to Cameroon on the drastic effect of both SAPs and PRSP and BWI policies.Footnote3 More worrisome, is that there is no clear relationship between the policies of the BWI and poverty eradication for those in poverty. More so, core BWI policies have continued to remain relevant and adopted in poverty reduction discourse globally and within the region.

8. Dissecting the SAPs and PRSPs on local context

Poverty reduction strategies are medium through which the West and the Financial Institutions (International Financial Institutions (IFI), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank) assumes will alleviate poverty in Africa and other developing countries by 25% within a 5-year radius (Torjman, Citation2014). It is a strategy that the Banks uses for granting concessional loans to developing countries, in essence, detecting the nature of expenditure of the lender, while the lender still had to repay the loan.

Noticeably, from the 1980s to date, the IFI including its subsidiaries the World Bank and the IMF have been consistently lending funds to developing countries given certain conditionalities to the lender country (ies). One of such conditions is the adoption of liberal policies and programmes that in most cases favours the idealism of both the Banks and the Western countries than it assist the lender in repaying the loan (Fraser, Citation2005, p. 317). There are two contending views in Fraser’s assertion; one is that there is no clear relationship between poverty reduction and the ability of a country to repay a loan. In that, to repay a loan all a country requires is to ensure it generate enough interest, and interest in itself do not lead to economic prosperity of the poorest in the society, rather its takes from the poorest in a country to service the elite. And secondly, economic growth on the other hand leads to surplus in the economy, which in most cases has no direct correlation to poverty reduction in a country, as South Africa and Nigeria had demonstrated in contemporary poverty analysis studies. In that, while there were improvements in economic growth, there were equally increases in the number of those in poverty 2011–2017 (Ndaguba & Hanyane, Citation2018; StatsSA, Citation2017). This notion therefore contradicts the basis and the whole essence for granting the loans in the first place and questions the Banks motives on either reducing poverty or in birthing or setting developing countries in the path of economic prosperity.

This is possibly because; the Banks are concerned that poverty among other social ills is a perilous concern to socio-economic growth, development and inclusion on the African continent. Partly because, most countries in Africa are both highly indebted and extremely poor (Kassey, Citation2013), but principally because African countries had failed to transform or build its local economy, and strengthen its structures and institutions to become formidable thinkers and actors in the globe. This is not to say, that the Government of African Countries have not attempted to grow their local economy or strengthen its institutions, but primarily because the West and East have in the past sabotaged and placed dangerous sanctions on nations that intended to adopt either socialist or communist approach to development rather than capitalism (see leaders as Kwame Nkrumah, Mahmoud Gaddafi, Nnamdi Azikiwe, Thomas Shankara, Walter Rodney, etc.), the fear of sanction and invasion have resulted in the hazy implementation of the Structural Adjustment Programme that ended up sapping away millions of jobs on the continent (Shah, Citation2013), outsourced the production of good and services to Western and Asian counties, created unemployment in Africa while creating employment for the West and Asia (Cleary, Citation1989, p. 41), and ceding government properties to local capitalist with Western mask among others (Zawalinska, Citation2004). This may be one of the reasons why such homegrown programme as Lagos Plan of Action among others were never implemented. This is to say that from time to time, the world-economies (the West, the East and now Asia) have always had the idea of a slave and a master relationship which is a reason it continually dishes sets of handouts (for Economic Recovery, Structural Adjustment Programmes, Highly Indebted Poor Countries initiatives, Poverty Reduction Strategies, and Millennium Development Goals among others) for the regions development, primarily, because Africa as a continent of 57 independent countries is still a primary producer of goods for economic prosperity and employment of the West and its allies, the East and its allies and now China and its allies. It is in this sense, that the speech of Patrice Lumuba of the Kenya Law School in relevant, Africa at the dinner table.Footnote4 This is to say, what happens in Africa is mainly detected from outside the continent. And the master uses the pond/servant for a purpose it considers right for it, at the expense of its people (see the antecedents of Paul Biya of Cameroon, Mohammad Buhari and Sani Abacha of Nigeria, Cecil Rhodes and Jacob Zuma of former Republic of South Africa, Faure Gnassingbé and Gnassingbé Eyadéma of Togo, etc.). Being the reason both the methodologies and conceptualization of a concept as poverty is defined by a people who have no experience of the concept. This is why it seems that most African countries are on a RAT-RACE in either catching-up or reducing poverty, despite several interventions which worsened rather than reduce poverty in the Sub-Saharan Africa, thus, at the start of the millennial a new international agenda was stipulated for poverty reduction without a formula.

9. Millennium development goals

The millennial brought with it a new international agenda for poverty studies along with other interrelated indicators that tend to alleviate people from poverty. The idea was conceived in Washington and introduced to the world in September of 2000, to save developing countries from drowning (Nwonwu, Citation2008, p. 1). This may include, universal primary education, reduction in child mortality, global partnership for development rather than global recommendations for development, improvement in maternal health which infers on the provision of improved healthcare, combating HIV/AIDs and malaria and other related diseases, environmental sustainability, empower women and promote gender equality, and the eradication of poverty and hunger (Atance, Citation2012). The eight stipulated indicators for the growth and development of developing countries were referred to as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), adopted by 189 countries in the United Nations Summit in September 2000 (Kiyimba, Alowo, and Abaliwano, Citation2011, p. 1; Ndaguba et al., Citation2016a, p. 607).

The MDGs were proposed as a result of the failures of SAPs and the unpopularity of the PRSPs among developing countries and community-led organizations. The MDGs had eight goals, 18 targets and 48 indicators (see Ndaguba et al., Citation2016a, p. 644–648; Ndaguba et al., Citation2016b, p. 609–615). Although the MDGs differed in procedures and processes of the SAPs and PRSPs. In that, the eight targets of the Goals could be summarized as geared towards poverty reduction, this is due to the notion that in developing countries, women are more likely to be in poverty to men. Therefore, there is a need to empower women and ensure equal distribution of wealth between women and men in terms of appointment, selection, placement and remuneration in organizations. More so, proliferation of studies exist establishing a relationship between universal primary education and poverty reduction, child mortality and improved healthcare (Forgét, Citation2013), HIV/AIDs and life expectancy, this is why we argue that most of the eight Goals of the MDGs may be geared towards one goal, poverty eradication and community sensitization. More so Odekon argued that the “financial resources needed for these ambitious goals, however, proved to be enormous and industrial countries as a whole failed to allocate the funds required for the project. Five years later, at the 2005 G-8 Summit in Gleneagles in Scotland, leaders renewed their commitment to fight extreme poverty in Africa with a promise of debt relief and economic and humanitarian assistance. The fine print, however, includes conditions for such assistance, with an emphasis on trade liberalization” (Odekon, Citation2006, p. x).

10. The dawn of the MDGs and the misfit of poverty reduction strategies

In 1995, at the United Nations World Summit for Social Development, world leaders resuscitated the need for poverty eradication and a pledge to halve global poverty was made (UN, Citation1995). This birthed the rise to a policy debate that resulted in the proclamation of the Millennium Development Goals in 2000 (United Nations, Citation2006; Ndaguba et al. 2016a; Ndaguba et al 2016b). To achieve the purpose of halving poverty globally by 2015, the MDGs programme was proposed (UN Citation2006). Other strategies, frameworks and initiatives that had been implemented over the years would include: Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAP) (Bretton Woods Project, Citation2001; Foster, Citation2005; Gumede, Citation2008; Welch, Citation2005); Policy Framework and Poverty Strategy Papers (PSRP) (Hanlon & Pettifor, Citation2000; Bretton Woods Project, 2001); Action Plan for the Reduction of Absolute Poverty (APRAP) (World Bank, Citation2005); Poverty and Social Impact Assessments (PSIA) (World Bank, Citation2005); Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) (World Bank, Citation2005); Poverty Reduction Growth Facility (PRGF) (Welch, Citation2005); Sector-wide approach (SWAP) (World Bank, Citation2005); World Bank Development Comprehensive Framework (CDF) (Bedi, Coudouel, Cox, Goldstein, & Thornton, Citation2006; World Bank, Citation2005); Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (IPRSP) (World Bank, Citation2005; Bedi et al., Citation2006, p. 94); Country Assistance Strategy (CAS) (Horton, Citation2010; World Bank, Citation2005); Antyodaya (Last Man First) (Deaton, Citation2006, p. 4); International Lawyers and Economists against Poverty; Poverty Reduction Support Credit (PRSC) (Horton, Citation2010, p. 3); Private sector intervention (Independent Evaluation IEG (Independent Evaluation Group), Citation2012); and Building human capacity and fostering resilience (World Bank, Citation2017a),

Despite, these global poverty reduction strategies and frameworks listed above, Williamson (Citation2003) and Bedi et al. (Citation2006, p. 13), had argued that poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa recorded is rising. Premised on the argument by Williamson, Bedi et al, Beegle et al, and Statistics South Africa one may conclude that none of the above listed and exempted poverty reduction initiatives triggered a sustained shift toward greater effectiveness or efficiency in development initiatives in relation to Sub-Saharan Africa in general and South Africa in particular. Resulting from the failures of international programmes and strategies to alleviate or eradicate poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa had adopted certain strategies, mechanisms, programmes and instruments for alleviating poverty in rural and urban centres in the country due to the failures of SAPs, PRSP, and MDGs, namely: Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative of South Africa; Black Economic Empowerment; Community Works Programme; Expanded Public Works Programme; Home-Based Community Care; Kha ri Guide Mass Literacy Campaign; Local Economic Development; Municipal Infrastructure Grant; National School Nutrition Programme; Neighbouring Development Grant Programme; New Growth Path; Operation Phakisa; Reconstruction and Development Programme; Small Enterprise Finance Agency; Social grants and social benefit packages; Social Security System; and Youth Economic Participation. Although, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution and some other strategies were predicated on the PRSP requirement and the austerity measure of SAPs which heightened and intensified poverty in the country.

One must note that as pregnant and congenial as these strategies, instruments and approaches were towards reducing poverty in the country, it is yet to produce sustained and sufficient outcomes that addresses chronic poverty in the county. In fact, reports from StatsSA (Citation2017) demonstrate on the contrary that poverty have been on the rise, although this may not exclusively be attributed solely to the limited or weak interventionist strategies for poverty alleviation. However, it is a principal factor, since poverty intervention should pilot economic activities that improve the living conditions of the people therein.

11. Misfit of poverty analysis—contours to poverty measurement and conceptualization in South Africa

The third phase creates an analysis for understanding poverty and poverty analysis. It is essential to note that the concept poverty is not entirely new to man, but its levels, dynamics, index and the measurability thereof overtime have remained problematic. Been the reason, variations exists as to the notion of poverty and its measurement. While the World Bank, UN and other financial and beverage industries sees extremely poverty as spending below $1.90 or food intake of 2,000 calories per day (Ndaguba and Ijeoma, Citation2017). Other international agencies as Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), Department for International Development (DFID) and Governance and Social Development Resource Centre (GSDRC). Scholars in International Development as: Sarah White, Selcuk Beduk, Sarah Bracking, Patrick Bond, Julian May, Stiglitz, Amatyr Sen, James Ferguson, Jeffrey Sachs, Budlender, Andrew Shepherd and Rogan among others have devoted years making an argument for the multidimensionalizm of poverty to no avail in developing countries.

The strategies and interventions adopted in South Africa (as an aspiring developed nation) differ from interventions and strategies from countries like the United States of America, Australia, and New Zealand among other developed nations. In that, these countries utilize the multidimensional measurement criteria for poverty analysis and a country that uses the unidimensional analysis always result to fighting hunger rather than poverty. Reducing poverty by adopting strategies that give people relief material as food and finances can only assist them to reach the 2,000 calories daily consumption. This does not alleviate poverty but simply alleviates hunger. For a country like America among others who use the multidimensional poverty analysis, their poverty alleviation strategies go beyond the provision of food stamps and social security for sustenance. In that, they prioritize other dimensions (e.g. capacity building, improved educational and vocational training, health, standard of living, science and technology among others) that lead to the reduction of poverty. Noteworthy is that the notion of multidimensional measurement is linked to desire fulfilment theories of Martha Nussbaum (Citation1994). More important is that the philosophy of Nussbaum’s theory of desire fulfilment surrounds the argument that the purpose for human existence is not merely to fill their stomachs. Rather to harness all their capabilities to live a satisfactory and fulfilling life (Nussbaum, Citation1988; White, Gaines, & Jha, Citation2014), that food or income alone cannot guarantee (Graham, Citation2011).

An extensive literature survey (internationally and locally) revealed that the level of poverty is on the rise (Beegle et al., Citation2016, StatsSA, Citation2017). Despite several strategies and policy programmes implemented over the years to reduce poverty globally (for example Action Plan for the Reduction of Absolute Poverty; Poverty and Social Impact Assessments; and Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility) and locally (for example Black Economic Empowerment; Community Works Programme; and Expanded Public Works Programme), poverty remains persistent (Beegle et al., Citation2016). To this extent, this paper argues that there are several problems that have inhibited poverty reduction strategies and frameworks from addressing poverty in South Africa and elsewhere (Gumede, Citation2008; Luiz & Chibba, Citation2012; Taylor, Citation2013; White, Citation2016). One of these problems is the fact that conventional policy frameworks are premised on outdated notions of poverty (see Orshansky, Citation1963, p. 65; Ravallion, Citation1992; Deaton, Citation2006). In that, conventional policy frameworks for poverty alleviation, such as the United Nation’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals, the World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAP), and in South Africa programmes as, Growth, Employment and Redistribution programme (GEAR), have not significantly reduced poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa in general and South Africa in particular (Beegle et al., Citation2016; StatsSA, Citation2017). This is probably because there exist a discrepancy in the measurement and conceptualization of poverty, this disparity as to the best-fit method agreeable between scholars (Budlender, Bond, Leibhrandt, Reddy, Pogge among others) and government (StatsSA and Social Development) to analyse poverty demonstrates the lack of comprehension of what is poverty. Till date, there are proliferations of studies (Gumede, Citation2008, Citation2009; StatsSA, Citation2017; Budlender, Woolard, and Leibbrandt, Citation2015a; Bond, Citation2016) contentiously debating which method is appropriate or best fit for poverty analysis from a multidimensional or unidimensional perspective.

Official discourse on poverty in South Africa and the wider Sub-Saharan African region have continued to rely on the unidimensional measurement for poverty predicated upon income or consumption (Gumede, Citation2008). It is thus evident philosophically, socially, politically, and methodologically that there is tension when the concept poverty is mentioned (Deaton, Citation2006). This is perhaps because the concept poverty is vague, and its vagueness is sometime misapplied, misused, misplaced or overtly misunderstood. This is possibly why it is difficult to formulate strategies that are responsive to poverty (Gumede, Citation2008, Citation2009; Sida, 2017). Thus, the inability to measure or conceptualize poverty adequately has led to poorly designed, framed, adopted and implemented strategies for poverty reduction that have yield over the years no satisfactory result in South Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa (Deaton, Citation2006).

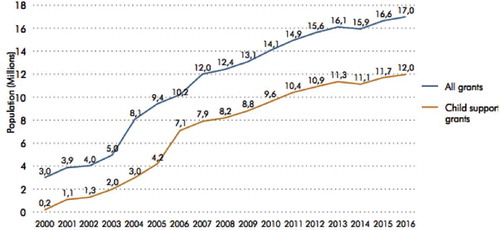

Since the way government perceives and conceptualize poverty determines to a significant extent the way government approaches it, in that, perception precedes intervention (Odekon, Citation2006). Therefore, in an instance were a government perceives poverty from a limited stance of income or consumption, the implication involved is that the method adopted for reducing poverty by such a government will also be limited from capturing effectively all the dimensions of poverty. This is probably why the South African Government have reduced its obligation towards reducing poverty to merely making social grants and food stamps available to those in poverty (see figure ). As Deaton (Citation2006) argues, when poverty is perceived from a limited dimension of money or consumption, government intervention will typically revolve around government creating benefits (e.g. money or food stamps) that enables citizens attain the 2,000 calories on the one hand, or/and make finances available through social security grants to cover sustenance needs (Deaton, Citation2006).

By implementing these strategies of social grant and food stamps to alleviate poverty in South Africa, the Government of South Africa seem to have created a form of state dependence, especially in rural communities in South Africa who can no longer live without this government subsidy.

Another significant deficiency is the nature of ambiguous strategic policy documents for alleviating poverty, non-consultation with communities and the general secrecy in government business. Ambiguity hampers objectivity, which in turn has an impact on the total outcome of procedure, task or process such as: the development of comprehensive strategies, the planning of poverty reduction endeavours, and the design of operational guidelines are hampered by ambiguity.

Generally secrecy in government fuels corruption, nepotism and indiscipline, which infers on the capabilities of poverty reduction institutions to realize their mandate of effectively reducing poverty (Baier, March, & Saetren, Citation1986; De Kumar, Citation2012, p. 133). Additionally, community involvement in identifying community programmes and projects for social and economic development is typically lacking (Deaton, Citation2006).

This goes to demonstrate that the government has enormous role to play in other to promote and enhance the effectiveness of poverty reduction programmes. Therefore, one may argue that the primary role of government in a capitalist economy is to create conducive atmosphere for businesses to flourish by designing policies and programmes for this purpose (Wolpe, Citation1972). However, in socialist states, the primary role of government is to design policies and programmes that seek to improve the social wellbeing of the people they govern. Therefore, for countries practicing a mixture of capitalism and socialism, there is a need for a fusion of business models in social enterprise. In the case of South Africa where such tendencies are found, there exist a void in praxis and in theory in community driven strategies utilizing business models for alleviating poverty or for creating sustainable businesses and economies in local municipalities.

The nexus between public administration and poverty reduction is long established. Poverty reduction is within the scope of public administration as a discipline, which deals with development policy (Raipa, Citation2002). Development policy is concerned with activities of government that tends to reduce the incidence of poverty, promote the realization of sustainable development globally, and the implementation of the fundamental rights to human dignity (Liu, Yu, & Wang, Citation2015; MFAF, Citation2018).

Poverty is the dearth or scarcity of certain material or non-material possession for subsistence (UNESCO, Citation2015). Yet, it seems that the South African Government largely ignores the non-material aspects of poverty (Bond, Citation2016; Budlender, Leibbrandt, & Woolard, Citation2015a, Citation2015b; Gumede, Citation2008). This is problematic for poverty alleviation strategists, because the way poverty is perceived determines the strategies and frameworks proposed and adopted for reducing poverty within a locality or sphere/tier (Deaton, Citation2006).

11.1. National and local government strategies for poverty alleviation

The decentralization and localization of national government strategies in the local sphere are enshrined in Section 152(b) and (e) and Section 152(2) of the 1996 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. These sections stipulate that local government must promote social and economic development, and encourage community involvement in matters concerning them.

Figure demonstrates that the Eastern Cape (EC) houses most of the individuals in poverty in the country. Statistics reveals that 72,9% of its population is living below the standardized Upper-Bound Poverty Line (UBPL) (StatsSA, Citation2017, p. 65). Elsewhere, it was established that there are principally two main reasons why poverty may reside in a province or area, either that there are limited economic opportunities and activities or there is a lack of government presence through social development and community emancipation projects.

11.2. Eastern cape and its structures

The Eastern Cape has two metropolitan municipalities, six district municipalities, and 31 local municipalities. Among the 31 local municipalities is the Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality (RMLM) within the Amathole District in Buffalo City Metropolitan municipality. On the 3rd of August 2016, there was a merger between Nxube and Nkonkobe local municipalities in the Amathole District to form the Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality (RMLM). The need for the merger of the two local municipalities was primarily to stimulate economic recovery of the municipality, in other words, to make the municipality economically viable (RMLM, Citation2017).

11.3. Medium of poverty intervention in local municipalities

In most municipalities in South Africa, especially local municipalities including the Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality, the modalities for poverty alleviation are mainly employment and empowerment (RMLM, Citation2017). The nature of employment by local municipalities is inadequate as a result of the amount payable for such a job monthly (e.g., of jobs—cleaners, gardeners and messengers) (R1, 500 per month an equivalent of USD$140) (RMLM, Citation2017). This amounts to about R50 per day (equivalent of USD$4 per day for an 8 h shift). This method for poverty alleviation is flawed on the amount payable, in that, the amount payable to these employees (R50) can hardly sustain a family unit per day. Additionally, the idea extended family members who are unemployed lean to those family members that have an income constitute another depth of the nature of working poor. This notion complicates the variable and escalates the cost in the standard of living at the municipal area, including the 6% increment on the cost goods and services in the country annually. This could be one of the reasons why poverty have consistently increased since 2011, especially in rural provinces (StatsSA, Citation2016, Citation2017).

Imaging the above description, Luiz and Chibba (Citation2011) argued that there is a need for a change in policies that addresses poverty, unemployment and inequality. This is in order to avoid a repetition of the orthodox mechanisms for tackling poverty in the country. Probably for the reason that conventional methods (e.g., economic growth, social grant and food stamps, etc.) for alleviating poverty in the country and internationally have not been beneficial to the South African populace and the Sub-Saharan region (Beegle et al., Citation2016; StatsSA, Citation2017). Therefore, new approaches and initiative should emerge, especially those that are community driven, innovative and eclectic in character (Chibba & Luiz, Citation2011).

12. Unidimensional poverty and poverty reduction reform in South Africa

In Charles Dickens novel titled, David Copperfield, the character Mr. Wilkins Micawber portrayed an eloquent understanding of the poverty threshold. As he frequently observes, “income twenty shillings, expenses nineteen shillings and six pence—result, happiness; Income twenty shillings, expenses twenty shillings and six pence—result, misery” (Deaton, Citation2006, p. 8).

This analogy is what Deaton referred to as, complete nonsense. The disturbing scenario about this is that this same method is what is been used in South Africa and the wider African continent in determining those in poverty from those out of poverty embedded in the argument of income vs expenditure measurement.

It is a truism that unhappiness is not a result of the lack of food/money, but a result of unfulfilled desires or expectations. Unfulfilled desires in the long run breed frustration. A frustrated individual is then a risk/threat to society. Hence, it has been argued elsewhere that insecurity and crime are some of the attributes of unfulfilled desires, negative psychology and an inadequate quality of life other than the lack of food. It is important to flaw the notion that the lack of food manifests itself in illicit desires of individuals in society. Hence, in South Africa, one is considered to be poor or to have escaped poverty, based on the methodologies of unidimensional poverty measurement and conceptualization, that is money and consumption. Thus, whether an individual is six Rands, six Cents or six million above the poverty line that individual is denied any form of intervention. Hence, the need for a multidimensional approach in the measurement of poverty in South Africa, which capture and takes into cognizance other dimensions that, initiates economic and personal development not merely of poor health, inadequate living standard, disempowerment, lack of education, and threat from violence and poor quality of work. But must also incorporate threats or factors that creates an atmosphere for increased poverty, education that does not fit industrial needs, improper family system, single parenthood, women entrepreneurship, and multinational and national wolves (exploitation). This other indicators are proposed on the basis that the multidimensional index as proposed in 2010 by OPHI is not all-inclusion given South Africa’s history and development trajectory.

The 2017 StatsSA report is a testament that a multidimensional measurement perception is due for poverty analysis in South Africa. Though the report demonstrated an oscillated perception of poverty trend, from 66.6% (31,6 millions persons) in 2006 (with a population of about 49 million) to 53% (27,3 million persons) in 2011, but increased to 55,5% (30.4 million person) in 2015 (with a population of 55.2 million) (StatsSA, Citation2017). It buttress the point made by Sen, Nussbaum, Alkire, Ravallion (recent), Reddy, Pogge, Foster, Greer, Thorbecke, Budlender, Marley, and Bond among others, such as, “money is numbers and numbers never end. If it takes money to be happy, (one’s) search for happiness will never end.” In the same context, if all a government cares about is to be seen as reducing poverty, the unidimensional measure for poverty analysis is opted. It is succinct to state that without multidimensional attributes given to improving the quality of life, the fulfilment of an individual’s desire, and an improved engagement with communities on issues that confront them. The rate of dependency and poverty will continue to increase in South Africa (see Figure ).

13. The twist and turns of measurement and conceptualization of poverty

The way and manner poverty is conceived determines to a greater extent the way it is measured. When it is conceptualized from a unidimensional method, it is limited and exclusive to money and food, when it conceptualized from the multidimensional perspective, in some case, its ambiguous and other times unrealistic (Deaton, Citation2006). Whether one conceptualizes it from unidimensional or multidimensional perspectives there are still several limitations. In that, the pattern globally and in Sub-Saharan Africa for dealing with those that fall under the unidimensional poverty threshold is through the provision of food stamps and money. This is probably because the unidimensional poverty only takes into cognizance both variables—food and income.

When conceptualized and measured from a multidimensional perspective, of which most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa abstain from, its still does not give a good example of how to understand poverty (Deaton, Citation2006). What if: we fix our health system and educate more people, does it mean that the standard of living will ultimately improve? This might not be the case, in Africa today, according to the ILO (International Labour Organisation) (Citation2003; Citation2018); the African continent has the highest number of working poor. It has the highest number of educated people in Africa’s history. Out of 17,000,000.00 graduates churned out by the over 668 universities in Africa, over 10,000,000.00 university graduates are unemployed. This goes to show that education alone might not be an automatic ticket out of poverty “no longer the key to success”.Footnote5

Perhaps, one would wonder, is unemployment not one of the issues conceived by Dudley Seers as a default to development in Todaro Smith’s book in 1977? Then why continue to make intervention based on means that do not bring about an adequate end? If the world and South Africa must be seen as fighting poverty, it must be perceived that it is fighting towards giving its citizens the ability of fulfilling their desire (what is referred to in America as the American Dream).

South African leaders must understand that the excitement and fulfilment of those during apartheid was simple, liberation, and after the liberation of the country from erstwhile colonialist, the next was to improve the living standard of the people. This, the country still awaits and these are some of the reasons why the frustration and negative psychological activities still rages as radical economic transformation, land grab, racism among others. This argument is premised on the notion that the end of humans need is to live a fulfilled and satisfactory life, rather than to fill their belly. For anyone who fills the belly today will certainly get hungry the next day. But those whose desires are fulfilled move towards having some level of dignity.

This is not to dismiss the assumptions and prepositions of various methodologies for measuring poverty on either unidimensional or multidimensional perspectives, but the argument is that if all indicators are not well established according the context for which such an analysis is presented, what then will be the purpose of the measurement in the first place? If it cannot grasp all the surrounding indicators and do not give the right solutions to poverty alleviation, then of what good is measurement in itself? For these we are uncertain that there is not an existing one-size-fit-all-approach solution to these problems. Since it has been established that poverty analysis determines interventions, then the idea of a measurement must that takes into cognizance every variable that causes poverty, which makes those in poverty to remain in poverty and helpless, including those close to the peripheral of the poverty threshold as well. For these set of people/household not to fall back into poverty, Statistics in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Africa in particular must capture factors as, the death of a father or breed winner and sudden poverty. These are debilitating uncertainties, about the extent of uncertainties that could plague a family in the African context, but are largely ignored in any measurement criterion. Though these might come at no simple fix, but it’s worth the try to set a nation towards a flourishing trajectory, that increases the chances of happiness and fulfilled desires.

In summary the notion of poverty reduction, poverty analysis and the roles of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in either poverty reduction, measurement or conceptualization is problematic because it was never the mandate or the role of either the IMF or the Bank. In that the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank conceived at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 by 44 nations with the sole aim of creating stable frameworks for post-war global economy. The IMF in its original visions statement was to promote steady growth and also ensure full employment by offering unconditional loans to establishing instruments to stabilize exchange rates, restoring economies in crisis and facilitating currency exchange. This vision was abandoned due to pressures from US representatives; rather than the IMF to offer loans unconditionally it resulted to offering loans based on strict conditions, which later form the austerity measure programmes or the structural adjustment. However, over the years critics have berated the nature of the conditions for the loans, which have in more ways than one resulted in several policy change and increase in poverty and instability in the African region. Due to policies that had worsened lax labour, decimated social safety nets and environmental standards in African countries (Lockwood, Citation2005). The idea for the establishment of the World Bank (The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) on the other hand, was primarily to fund the infrastructural damages cause by the World War II. It visions were thwarted in the 1950s, and the Bank’s attention turned from funding infrastructural development to industrial development projects, particularly, not in Europe but in Asia, Latin America and Africa. Resulting from the unpreparedness of the Bank and the IMF for the challenge of the future, many scholars and activists have argued that the aggressive dealings of the IMF and the Bank have exacerbated the debt crisis in developing nations and devastated indigenous communality, the local ecologies and economies. Since, importation was a prerequisite for loans by either the Bank or the IMF.

14. Limitations

Regardless of how meticulous, polemic or thought-out a research/er is, he or she cannot cover all the aspect of any topic, much less, poverty. Poverty is a deep problem in Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa in particular and medium towards reducing this plague have not been fruitful. To this end, several studies have postulated or analysed varied reasons (corruption, slow economic growth, income inequality, unemployment, colonialism among others (see works of Budlender, Bond, Gumede, Alkire, White, Nussbaum, Woollard, Braithwaite, Ravallion, Roser, World Bank, IMF, etc.) for the consistency and continuity of poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. Given that one single research paper may never cover all sectors of a research as poverty, in this paper, we do not pretend or argue to have covered all the challenges of international development, poverty alleviation strategies, and measurement and conceptualization issues. However, we argue that international development strategies for poverty alleviation contravene methodologies for local and community economic development in local context. Hence, our argument in this paper is that, local and community economic development agenda in local context should dictate or govern international development strategies for poverty alleviation.

15. Conclusion

Some believe that the world changes with the wisdom of the old. I think that the idealism, innovation, energy and “can do” attitude of the youth is even more powerful. That is my hope for India too, 800 million youth joining hands to transform our nation. To put the light of hope in every eye, and the joy of belief in every heart. Lift people out of poverty, put clean water and sanitation within the reach of all, make healthcare available to all. A roof over every head. I know it is possible.” Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India (2014).

Never in the history of man have we seen so much wealth, yet so much poverty. The persistence of poverty in the globe in general and Sub-Saharan Africa in particular is a moral indictment of world leaders and global capitalists (Ndaguba et al., 2016). Poverty is a deep-seated, complex and a pervasive reality, plaguing developing and least developed countries the most. In 2003, ILO decried the levels and intensity of global poverty, demonstrating that a half of the world’s population live on less than US$2 per day, and more than a billion struggle on less than a dollar per day (ILO (International Labour Organisation), Citation2003, p. 1). More importantly, is that vicious circle of poverty were primarily not the main concerns of either the SAPs or the PRSPs, which may include, poor healthcare, low productivity, shortened life expectancy, mass retrenchment, privatization of government assets, poor government regulation of primary goods and services, ineffective social and economic systems, structural and systemic failures of government functionaries, institutional failures and integration, political and economic instability, poor balance of trade, insufficient international support on homegrown solutions to local problems, and the doctrine of individualism to Africa’s social support systems. These deficiencies constitute in many respects the reason why the SAPs, the PRSPs and the MDGs where circumstantial in responding to the many challenges confronting Sub-Saharan Africa.

To understand these challenges, one must note that of the 54 countries in Africa, over 30 are among the Least Developed Countries, and most of these 34 countries have significant amount of both natural and human resource that could propel human and infrastructural development to compete amongst the world (UNECA, Citation2014, p. xiv). More so, the nature, height and depth of both conflict and corruption have reduced in many ways the abilities of most countries within the region to elevate from the peril of poverty and in turn become transform (Ndaguba et al. 2018).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

E. A. Ndaguba

E. A. Ndaguba specialises in poverty reduction, community economic development, stakeholder theory, international development and global partnership.

Barry Hanyane

Barry Hanyane is a Professor at the North West University specialising in governance, poverty alleviation, monitoring and evaluation, gender studies, corruption and generally public administration and politics.

Notes

1. Max Roser’s analogy of poverty from 1820 to 2016 will be analysed in the preceding paper.

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson. J. A. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty (1st ed.). New York, NY: Crown.

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369-1401.

- Atance, L. A. (2012). Millennium development goals for Sub-Saharan Africa. EOI. Retrived June 4, 2018, from www.eoi.es/blogs/lauraambros/2012/01/17/millenium-development-goals-for-sub-saharan-africa/

- Baier, V. E., March, J. G., & Saetren, H. (1986). Implementation and ambiguity. Scandinavian Journal of Management Studies, 2(3–4), 197–212. doi:10.1016/0281-7527(86)90016-2

- Bedi, T., Coudouel, A., Cox, M., Goldstein, M., & Thornton, N. (2006). Beyond the numbers: Understanding the institutions for monitoring poverty reduction strategies. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank.

- Beegle, K., Christiaensen, L., Dabalen, A., & Gaddis, I. (2016). Poverty in a rising Africa: Africa poverty report. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Bond, P. (2016). Do government spending and taxation really reduce inequality, or do we need more thorough measurements? A response to the World Bank researchers. Econ3x3. Retrived February 19, 2018, from www.econ3x3.org/article/do-government-spending-and-taxation-really-reduce-inequality-or-do-we-need-more-thorough

- Budlender, J., Leibbrandt, M., & Woolard, I. (2015a). South African poverty lines: a review and two new money-metric thresholds (SALDRU Working Paper Number 151). University of Cape Town

- Budlender, J., Leibbrandt, M., & Woolard, I. (2015b). How current measures underestimate the level of poverty in South Africa. The Conversation. Retrived February 19, 2018, from www.theconversation.com/how-current-measures-underestimate-the-level-of-poverty-in-south-africa-46704

- Chibba, M., & Luiz, J. (2011). Poverty, inequality and unemployment in South Africa: Context, issues and the way forward. Economic Society of Australia’s Economic Papers, 30(3), 307–315. doi:10.1111/j.1759-3441.2011.00129.x

- Chibba, M., & Luiz, J. M. (2011). Poverty, inequality and unemployment in south africa: Context, issues and the way forward, economic papers. The Economic Society of Australia, 30(3), 307-315.

- Cleary, S. (1989). Structural Adjustment in Africa (pp. 41–59). Dublin: TJ’lkaire Development hview. ISSN 0790-94<13.

- Cornia, G.A., & Helleiner, G.K. (1994). From adjustment to development in Africa: Conflict, controversy, consensus? London and Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN:0333613619

- De Kumar, P. (2012). Public policy and systems. Delhi: Pearson.

- Deaton, A. (2006). Measuring Poverty. In A. V. Banerjee, R. Bénabou & D. Mookherjee (Ed.), Understanding Poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dembele, D. M. (2011). Challenges for democratic ownership and development effectiveness. Democratic Ownership and Development Effectiveness: Civil Society Perspectives on Progress since Paris, 93.

- Dijkstra, G. (2011). The PRSP approach and the illusion of improved aid effectiveness: Lessons from Bolivia, Honduras and Nicaragua. Development Policy Review, 1(29), 111–133.

- Ferreira, F., Jolliffe, D. M., & Prydz, E. B. (2015). The international poverty line has just been raised to $1.90 a day, but global poverty is basically unchanged. How is that even possible? The World Bank. Retrived December 3, 2017, from http://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/international-poverty-line-has-just-been-raised-190-day-global-poverty-basically-unchanged-how-even

- Ferreira, F., Lakner. C., & Sanchez, C. (2017). The 2017 global poverty update from the World Bank. World Bank. Retrieved December 05 2018, from https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/governance/2017-global-poverty-update-world-bank

- Forgét, J. (2013). 5 Poverty Statistics on Sub-Saharan Africa. Retrived June 4, 2018, from https://borgenproject.org/5-poverty-statistics-on-sub-saharan-africa/

- Foster, M. (2005). MDG oriented sector and poverty reduction strategies: Lessons from experience in health. The International bank for reconstruction and development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Fraser, A. (2005). Poverty reduction strategy papers. Now who calls the shots? Review of African Political Economy, 32(104–105), 217–340. doi:10.1080/03056240500329346

- Garuda, G. (2000). The distributional effects of imf programs: A cross-country analysis. World Development, 28(6), 1031–1051.

- Graham, C. (2011). Does more money make you happier? Why so much debate? Applied Research Quality Life, 6, 219–239. doi:10.1007/s11482-011-9152-8

- Gumede, V. (2008). Poverty and Second Economy Dynamics in South Africa: An attempt to measure the extent of the problem and clarify concepts (Development Policy Research Unit Working Paper 08/133). Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Gumede, V. (2009). The war on poverty begins. IOL. Retrived February 20, 2018, from www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/the-war-on-poverty-begins-426348

- Hanlon, J., & Pettifor, A. (2000). Kicking the habit: Finding a lasting solution to addictive lending and borrowing - and its corrupting side-effects. London: Jubilee Research Place.

- Heidhues, F., & Nyangito, Atsain, A., H., Padilla, M., Ghersi., & G. Le Vallée, J. (2004). Development strategies and food and nutrition security in Africa: An assessment. 2020 discussion paper No. 38. Washington, D.C.: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Heidhues, F., & Obare, G. (2011). Lessons from structural adjustment programmes and their effects in africa. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture, 50(1), 55-64.

- Hodal, K. (2016). Nearly half all children in Sub-Saharan Africa is extreme poverty, report warns. Retrieved December 05 2018, from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2016/oct/05/nearly-half-all-children-sub-saharan-africa-extreme-poverty-unicef-world-bank-report-warns

- Horton, B. (2010). Poverty Reduction Support Credits: Benin Country Study (IEG Working Paper 2010/12). Washington: Independent Evaluation Group, The World Bank Group. ISBN-10: 1-60244-155-3

- IEG (Independent Evaluation Group). (2012). The private sector and poverty reduction: Lessons from the field. Washington, DC: The Independent Evaluation Group.

- ILO (International Labour Organisation). (2003). Working out of poverty ISBN 92-2-112870-9. Geneva: International Labour Conference 91st Session 2003.

- IMF. (2016). Poverty reduction strategy in IMF-supported program. Washington, DC: Author.

- International Monetary Fund. (2014). Regional economic outlook. Sub-Saharan Africa - Staying the course. Washington, D.C: IMF.

- Jazaïry, I., Alamgir, M., & Panuccio, T. (1992). The State of World Rural Poverty: An Inquiry into Its Causes and Consequences. ISBN 9789290720034. New York, NY: University Press.

- Kassey, K. D. (2013). Global poverty reduction policy and implementation strategies at local level, integrated planning options and challenges in a developing country, Ghana. Merit Research Journal of Art, Social Science and Humanities, 1(6), 076–085.

- Kenny, C. (2017). Do Weak Governments Doom Developing Countries to Poverty? Center for Global Development. Retrived February 20, 2018, from www.cgdev.org/blog/do-weak-governments-doom-developing-countries-poverty

- Kiyimba, J, Alowo, R, & Abaliwano, J. (2011). Localising the millennium development goals in uganda: Opportunities for local leaders (briefing note / wateraid). Kampala, Uganda: WaterAid.

- Levinsohn, J. (2013). The World Bank’s Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Approach: Good Marketing or Good Policy? G-24 Discussion Paper Series April 2003. New York and Geneva, UNITED NATIONS.

- Liu, Q., Yu, M., & Wang, X. (2015). Poverty reduction within the framework of SDGs and Post-2015 Development Agenda. Advances in Climate Change Research, 6(1), 67–73. doi:10.1016/j.accre.2015.09.004

- Lockwood, M. (2005, June 24). We must breed tigers in Africa, The Guardian, 2005.

- Luiz, J., & Chibba, M. (2012). Poverty alleviation Policy makers need to think again. Leadership. Retrived October 12, 2017, from http://www.leadershiponline.co.za/articles/poverty-alleviation-1800.html

- Malaluan, J. J. C., & Guttal, S. (2002). Structural adjustment in the name of the poor: The PRSP in the Lao PDR, Cambodia and Vietnam, Focus on the Global South, Thailand. Retrieved December 05 2018, from https://focusweb.org/content/structural-adjustment-name-poor-prsp-experience-lao-pdr-cambodia-and-viet

- Martin, J. (2007). The 17 great challenges of the twenty-first century. Oxford University. Retrived February 19, 2018, from www.elon.edu/docs/e-web/predictions/17_great_challenges.pdf

- MFAF, (2018, February 12). Goals and principles of Finland’s development policy. Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. Retrived from www.formin.finland.fi/Public/default.aspx?nodeid=49312&contentlan=2&culture=en-US