Abstract

Informal work procedures are often untapped in organisations because they remain compartmentalised and unavailable for organisational learning. Trends from Auditor General Reports show the metastasising culture of non-compliance in local government and by implication the re-enforcement of procedural compliance in many avenues. This study explores the value informal work procedures can add to building a strong compliance-based culture in South African local governance. The study contributes to knowledge on organisational studies and compliance in local government by moving beyond formal procedural explanations to highlight informal work procedures as critical elements of the municipal compliance discourse. A qualitative methodology using interview data shows that local government managers operate based on informal work practices and procedures, which create a potential for learning and compliance value chain. The findings also suggest that where local government managers are able to consciously create synergies between informal and formal work procedures a municipal culture that supports innovation, compliance and effective performance develops. It is proposed that addressing the gap between “work as imagined” and “work as actually done” can present an opportunity for building compliance through organisational learning.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The positive attributes of informal work procedures are often untapped in organisations. Our results show that a conscious engagement with informal work procedures by managers is beneficial to the organisation. The findings show that this can be achieved through building compliant-based climates through informal work procedures. This involves a conscious effort towards identifying and encouraging positive learning and reflective practice. The study found that this can be achieved through regular meetings and verbal interaction with staff to identify and encourage behaviour within the informal organisational space. The study findings are also significant for practitioners in sectors and contexts where written and formalised work procedures may be a challenge due to literacy, language and other factors.

1. Introduction

From an organisational culture and practice viewpoint, the informal work environment is not new. Indeed, extant literature examines aspects of the informal organisation such as informal learning (Serrat, Citation2017); informal governance or controls (Chwieroth, Citation2012; Goebel & Weißenberger, Citation2017; Singhapakdi & Vitell, Citation2007); informal communication/social exchange (Davison, Ou, & Martinson, Citation2007; Singh, Bains, & Vinnicombe, Citation2002); and informal work climate (Kay & Gorman, Citation2012). These studies also demonstrate the contributions of the informal organisation in areas such as organisational ethics, knowledge sharing, performance and innovation.

Like most informal aspects of the organisation, informal work procedures are non-formalised procedures which develop as a result of the dynamics within and outside the formal and informal organisation. However, informal work procedures are distinct in that they can be nurtured and managed through other forms of the informal organisation. For instance, the nature of social exchange dynamics, employee attitude, commitment and competence leads to gaps between work as imagined and work that is actually done (Antonsen, Almklov, & Fenstad, Citation2008). Taking this argument further, informal knowledge management practices, such as “guanxi” in Chinese management experience, show that mutual reciprocity, employee ties and interdependence engender knowledge sharing where reliable knowledge is scarce (Davison et al., Citation2007). Such informal practice can encourage informal procedures which rather than disrupt organisational processes will add value to the organisation. This requires a work procedures design perspective that recognises informal interpersonal relations and the unpredictability of human behaviour.

In this research we examine how informal work procedures can produce compliance value. Simply put, compliance means meeting the requirements of rule, standard, specification or law. These requirements for compliance manifest as governmental and/or non-governmental regulatory and policy frameworks and include internal business or organisational policies, procedures and guidelines (Benedek, Citation2012, p. 136). Schlager (Citation2005) submits that effective rules are designed based on an understanding of the factors that affect compliance. This implies that regulation goes beyond formal law to the generation of expression and management of emotions (Lange, Citation2002). In this sense, for our purposes, compliance value denotes standards of behaviour that help employees make important judgements on compliance.

To our knowledge, there appears to be limited research on the value of informal work procedures in increasing compliance within organisations. Moreover, while there is evidence that the informal organisational climate such as attachment to organisation and social bonding activities may nurture a compliance-focused culture (Cheng, Yin, Wenli, Holm, & Zhai, Citation2013; Ifinedo, Citation2014) the specific role that informal procedures may play in this regard is as yet unclear.

From a practice perspective, the article interrogates the extent to which managers are consciously open to informal procedures as a critical route to achieving compliance. From a knowledge perspective, this article aims to contribute to understanding compliance in local government by highlighting informal procedures as an important element of the local government compliance discourse.

To this end the article seeks to answer three questions: What is the conceptual scope of informal work procedures? What are the experiences of informal procedures in the municipality? Which practice experiences can yield compliance value through informal work procedures?

1.1. Compliance in South African local government

One of the best ways to measure local government compliance is the Auditor-General of South Africa (AGSA) reports. Compliance from the Auditor General’s purview is an indicator of sound financial and administrative management. The Eastern Cape Province for many years has struggled with audit compliance. Before the 2013/2014 reporting year, no municipality had ever achieved clean audit (unqualified audit with no findings) (AGSA, Citation2014/2015, p. 14). However, in recent years, there have been improvements with more municipalities achieving clean audits (AGSA, Citation2015/2016). While there are improvements, 67% of audit findings in the Eastern Cape are still poor. The Auditor General points to weak municipal accounting systems, the control environment and record management (AGSA, 2017).

The area of focus of the AGSA also spreads to public sector areas where non-compliance affects reported financial and performance information. It is seminal to note that priority is also given to areas where there is a high risk of non-compliance such as (a) adherence to reporting requirements as prescribed in the finance management acts Public Finance Management Act (PFMA) and Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA), (b) adherence to supply chain management prescripts in procuring goods and services and (c) human resource planning and appointment processes. Nevertheless, the onus to prevent and detect non-compliance rests on the leadership within different spheres of government (Nombembe, Citation2011). Literature that relates to compliance within the government departments is not well documented, and AGSA reports do not fully grasp the aspect of compliance to work procedures. In this research we focus on the control environment. Work procedures encompass rules that can be thought of as “controls”. Controls are defined as any process, policy, device, practice or other actions which determine how work is to be performed in a particular context. Within work procedures, controls typically define concrete work/task actions that need to be taken under particular conditions (Praino & Sharit, Citation2016, p. 383). Controls can be distinguished on how they work on the process. Directing controls steer the work process to achieve a specific state, whereas controls that are limiting establish conditions that are to be avoided (Praino & Sharit, Citation2016, p. 384).

1.2. Research context

The municipality in focus is a local municipality located in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. According to STATSA (Citation2016), the municipality has a population of about 145,358. In terms of education, 95% of that population is without higher education (5% higher education) and 88% not completing secondary school (12% with grade 12) (STATSA, Citation2011). These numbers are also significant in terms of overall literacy levels of the municipal workforce. That notwithstanding, this municipality has consistently maintained an unqualified audit, albeit with findings for the past 7 years. The AGSA reports over the years (2014; 2017) show that

Leadership (especially management) understand their role in maintaining a clean administration through adequate processes. However, commitment to their roles in providing information and guidance is needed in this regard.

Even with this leadership climate, there is repeated non-compliance with legislation.

Another challenge is the dearth of skills which is heightened by municipal overall literacy levels. This may be a challenge in terms of overall compliance, especially formal compliance strategies, which require written documentation.

Although management is addressing issues of internal controls, there has to be an overall municipal strategy to mitigate some of the challenges posed to non-compliance in terms of the workforce.

In this article, we present the value that a conscious approach to using informal work procedures can bring to compliance.

2. Limits of formalised work procedures

Work procedures act as a defensive means against human mistakes that may occur during executing the work to ensure predictability and regularity in human behaviour (Antonsen et al., Citation2008; Brodbeck, Citation2002; Reason, Parker, & Lawton, Citation1998). Thus, they are invaluable in managing areas of work that are prone to human error such as with safety and/or violations such as with compliance.

However, there is evidence to show that the development of control mechanisms through procedural guides has in many cases failed to foster compliance to the procedures as people tend to default to their own way of performing tasks (improvise). Indeed many studies on compliance to Information Systems Policies and Procedures show that informal sanctions tend to have more impact on employee compliance behaviour than formal sanctions (Cheng et al., Citation2013; Hu, Dinev, Hart, & Cooke, Citation2012; Vance & Siponen, Citation2012). In illustrating the limits of compliance-focused procedures on employee ethical behaviour, Paine (Citation1994) argues that legal compliance does not cover the full range of ethical issues experienced daily by employees. In the same vein, establishing compliance procedures to meet compliance with external legal demands on organisations does not guarantee compliance, even where there is threat of detection and punishment because of varying individualised dispositions. These dispositions range from individual’s beliefs or morals (Ariel, Citation2012, p. 28; Fairbass, et al., Citation2015); socialisations (Ifinedo, Citation2014; Safa, Solms, & Furnell, Citation2016); commitment to the organisation (Antonsen et al, Citation2008; Cheng et al., Citation2013); ability to read and understand (knowledge and competence) and procedural justice perceptions such as the extent to which employees feel part of the development and design process (Tyler, Citation1990; Murphy and Tyler, Citation2008; Antonsen, 2008). Thus, employees will tend to act on existing loopholes to solve more pressing day-to-day problems. It is based on these limitations that greater scrutiny has been reserved in extant literature on the role of the informal organisation. For our case we focus particularly on the role of informal procedures.

3. Informal work procedures

While informal work procedures suggest processes outside prescribed rules and standards, from an organisational practice perspective, a consensus definition of informal procedures is more complex. Although studies on the informal organisation abound, there are fewer studies that examine informal work procedures within this framework. Formal work procedures rely on rules and regulations against deviant behaviour (Cheng et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, informal work procedures are relatively unstructured, they have no fixed procedure or strong institutional rules, but employees improvise their work/task processes to achieve desired outcomes, they are bound to specific individuals and their work relationships (Connolly, Lang, Gathegi, & Tygar, Citation2017, p. 121; Stouthuysen, Slabbinck, & Roodhooft, Citation2017, p. 52). Thus, informal work procedures thrive predominantly within an organisation’s social space. This implies that human resource relations and specific organisational culture characteristics influence the development of informal procedures (Kay & Gorman, Citation2012, pp. 92–93).

For the purposes of this study informal procedures are conceptualised as unwritten/documented guidance on work processes, driven by management through effective use of the informal organisation to improve municipal compliance. The study identified three important variables in conceptualising informal procedures:

Extent to which procedures are documented: A clear document structure for procedural guidelines is a standard requirement for formalised procedures. Informal work procedures develop where documented procedures are perceived as burdensome and where employees work outside stipulated provisions (Squires, Moralejo, & Lefort, Citation2007).

The role of communication: Communication is a process of creating and sharing information between parties towards reaching mutual understanding (Rogers, Citation2003). This study views communication as an intangible organisational asset (Malmelin, Citation2007), channelled through informal communication avenues like interpersonal and interactive networks (Roger, 2003).

Feedback and continuous improvement: As will be explored later in this article, informal work procedures provide opportunities for learning and adaptation. As such, informal work procedures are indicative of how feedbacks from the internal and external organisation are harnessed to create organisational learning and change (Brodbeck, Citation2002, p. 394).

3.1. How informal work procedures can create compliance value

To understand informal procedures from the view of compliance, there needs to be an acknowledgement of the role of the external and internal environment on organisational and individual behaviour and the divergent reaction of these two units to these pressures. Thus, the subsequent sections present three important approaches to understanding the compliance value of informal work procedures.

3.1.1. The internal and external environment

Brodbeck’s (Citation2002) work on work procedure design and complexity theory shows that a non-linear approach to work procedures is one which considers organisations as Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) which react to internal and external stimuli. In the South African local government context, fast global changes, increase in political schisms, increasing demands from regulatory institutions, complexities within the intergovernmental relations system, innovation and multifaceted demands from citizens present municipal environments with so much uncertainty. Additionally, actions taken to reduce these uncertainties most times throw organisations into further unpredictability. In such cases, complexity theory can be used to understand organisational behaviour and guide strategy (Mason, Citation2007).

Complexity theory is a process-based model in the study of organisational change which lays a strong emphasis on the complexity of the internal and external environment and the complexities pressures from these environment impose on the organisation. Mason (Citation2007, p. 10) defines complexity as the measure of heterogeneity or diversity in the internal environment (values, culture, demands for performance, behaviour of management, etc.) and environmental factors (such as department, customers, suppliers, the legislative, socio-political and technology). For our case, the value of chaos and complexity is in the cultivation of an alternative “process of order” (Mason & Dobbelstein, Citation2016). Although outside the control of the manager, self-organisation is generated through interactions between other agents in the system (e.g. employees, citizens, suppliers) towards creative and innovative responses. This in turn leads to the “emergence” of new actions right at the edge of the chaos (Mason & Dobbelstein, Citation2016). Brodbeck’s (Citation2002) study into procedure design suggests that emergent behaviour is inevitable within a CAS due to the personalisation of procedures and the aim will be to harness continuous bottom-up information streams generated through discretionary problem-solving practices. These experiences create patterns of emergent learning which must be supported by management (Serrat, Citation2017). Thus, for compliance purposes, it is vital to effectively safeguard and harness this type of feedback into the organisational decision-making system, through the management of continuous changes imposed by the internal and external environment.

3.1.2. Individual behaviour as a reaction to stimuli

Many studies on compliance focus on individual psychological dispositions of attitude and intentions in decision-making processes involving ethical dilemma or intention to comply (Goebel & WeiBenberger, Citation2017, p. 506; Helmreich, Citation2000, p. 467). We examine two approaches to human reaction to environmental stimuli, the first is through a frame that imposes more restrictions (through prescribed work procedures) towards ensuring rule-based compliance; the other is through a frame that engenders a compliant-based organisational culture through informal work procedures.

Ensuring rule compliance through formalised procedures: The preoccupation with formalised and rule-based procedures has led to the suggestion that organisations “depersonalised” emergent informal learning, social elements and norms from informal practice into formalised procedures (Brodbeck, Citation2002, pp. 382–383). Formalised work procedures portend traditional approaches to work procedures much in the form of control of human behaviour (Brodbeck, Citation2002, Reason et al., Citation1998). Work procedures in this form are important in helping the diffusion of organisational knowledge and practice (Squires et al., Citation2007). They also serve a legal function through compliance among many other uses. Nevertheless, there is little value to a procedural system which is not adhered to. We argue that informal procedures can also produce individual compliance through a compliant-based culture.

Engendering a compliant-based culture through informal procedures: There is empirical evidence that links informal procedures to the distance between operational-level employees and work procedures originators at management level. This results in a mismatching of work procedures as prescribed and the actual events taking place on the ground (Antonsen, 2008, p. 2). Some studies also suggest that informal work procedures are initiated in spaces where human error and violations become routinised (Reason et al., Citation1998, pp. 291–292). Depending on what the internal organisational environment looks like (e.g. relationships between management and employees, performance pressures from organisation), some errors and violations can result in extensive organisational fracture. However, there is empirical evidence to suggest that errors at the early stage of learning or practice are necessary to reinforce avoidance and practice (Dyre, Tabor, Ringsted, & Tolsgaard, Citation2017). This is in line with Reason et al.’s (Citation1998, p. 291) argument that there are errors and violations without immediate consequences and which have the added value of making work easier and faster. Thus, errors or violation provide for experiential learning where employees may “benefit from imperfect practice as a means to achieving perfect practice” (Dyre et al., Citation2017, p. 204). To accomplish this goal, employees need to make a conscious effort to recognise and reflect on errors or violations as opportunities for learning and experience (Dyre et al., Citation2017). We thus posit that informal work procedures can occur within the space of violations which have no detrimental or immediate consequences. This is suggested as an important management focus in creating a compliance-based culture.

3.1.3. Organisational behaviour as a reaction to stimuli

Organisational behaviour is stimulated through an organisational climate where routine behaviours are implicitly cultivated, supported and rewarded. This is the organisational space where the diffusion of intangibles such as verbal and interactional arrangements and cognitive biases are used as tools for indirect assimilation of particular organisational values (Kay & Gorman, Citation2012, pp. 92–93). In this case these values are tied to what we term here as a compliance-driven work climate. Compliance in this case becomes a reflection of an organisational culture, rather than an imposition. We argue that this culture can be perpetuated by the nurturing of the indirect assimilation of values based on practice experiences of organisational procedures. This is the shared values concept of compliance (Paine, Citation1994). We define a compliance-driven work climate as organisational routine behaviour which must reflect the organisation’s shared values as a commitment to consistency in fulfilling its legal regulatory and ethical responsibilities. We therefore argue that the identification, recognition and reinforcement of informal procedure streams can help grow a compliance-driven work climate.

The next section presents our research findings from interviews with managers. The findings aim to answer the research questions and establish some examples of informal work procedure as observed in practice.

4. Methodology

This was a descriptive and exploratory case study. A qualitative method was adopted to investigate informal work dimensions related to work procedures in the municipality under investigation. Atieno (Citation2009) expounds that qualitative methods are good at simplifying and managing data without destroying complexity and context. Qualitative methods are also highly appropriate for questions where pre-emptive reduction of the data will prevent discovery. Given the focus on informal work procedures, a case study design was preferred as it allowed the investigation to retain the holistic and meaningful opinions of the respondents. Additionally, the nature of the topic necessitated an inductive approach which aimed to find emerging meanings and alternatives in finding compliance value in informal procedures in certain contexts. In this case, as with many municipalities in South Africa, the local municipality is situated in a semi-rural area, straddling urban and very rural communities, these departments represent a diverse demography of employees (e.g. age, education, position). This context is seen as having relevance for informal application of work procedures.

A key attribute of descriptive or exploratory case study is that it tries to illuminate sets of decisions, why they were taken, how they were taken, how they were implemented and with what results. This is important for this particular research as it helped in consolidating all the responses from different managers and countering subjectivity in the process. For the interviews we purposively sampled seven departmental managers who are responsible for the development of work procedures and monitoring employees` compliance to these procedures. These included managers from the departments of infrastructure, public participation, community service, finance and corporate services. These units are the bedrock of municipal administration and services. Of the seven managers interviewed, four had established careers in local government as managers working in different municipalities across South Africa. Data was collected through face-to-face interviews using voice recorders and transcribed, to document the responses in writing. The questions consisted of open-ended questions aimed at providing thick descriptions, producing critical comments and added insight on how informal procedures can add compliance value.

To ensure credibility, applicability, value and trustworthiness, the entry into the municipality was established through the formal contact with and approval from the case municipality. The reasons for the research and ethical clearance for the research were discussed with managers in a meeting at the municipal grounds. Additionally, transcribed interviews were presented to the interviewees to confirm the validity of answers they provided. To strengthen the results of the data generated from face-to-face interviews with municipal managers, triangulation was employed through the presentation of data to the rank and file employees who could validate the responses of the managerial employees. Furthermore, essential ethical issues such as anonymity and confidentiality were observed by assuring the respondents that every effort would be made to ensure that the information they provided could not be traced back to them in reports, presentations and other forms of the study data dissemination. Finally findings were further validated by confirming results with other evidence from literature.

For data analysis, we used qualitative content analysis which has been defined as “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns”, (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005, p. 1278). Qualitative content analysis emphasises an integrated view of speech/texts and their specific contexts. Atlas.ti software was employed to analyse content texts, the broad objectives relating to this study were coded (based on theoretical definitions of categories) and linked to quotations from the interviews in order to come up with a consolidated response through networking.

To this end, we linked the responses and consolidated the views and opinions of different managers from the municipality under study relating to the informal work procedures use and compliance. Our particular focus was to examine meanings, themes and patterns that may be manifest or latent in the particular text. The following guided our process. We read the transcript and labelled relevant pieces in line with their receptiveness, and we created important categories to show emphasis from respondents; confirmations and deviations from the literature. The aim was to consolidate texts that inform the research questions related to the application of informal work procedures in the municipality.

4.1. Findings and discussions

The findings and discussion aim to answer the following research questions presented in the introduction: (a) What are the experiences of informal work procedures in the municipality? (b) Which practice experiences can yield compliance value through informal work procedures? We identified emerging themes and categorised them (as indicated in Table ).

Table 1. Themes and categories

4.2. Informal work procedures in the municipality

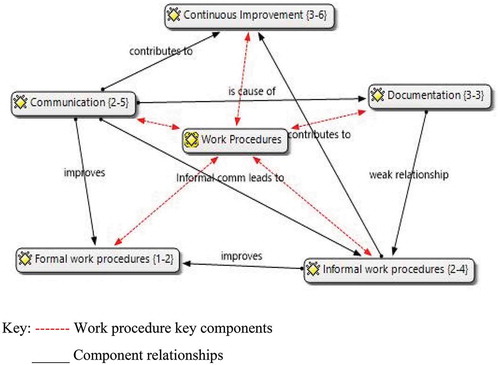

Literature on work procedures presents the key elements that are imperative in analysing the influence informal work procedures have in developing and strengthening formal work procedures. Figure shows the networks and relationships that exist among work procedure indicators such as communication, documentation and continuous improvement.

Figure 1. The influence of informal work procedures on the development and improvement of work procedures

Figure explores the nature of the relationship which exists amongst the components which contribute to the adoption and use of work procedures. Probes from the interviews revealed that communication and documentation are important aspects contributing to compliance with work procedures. However, explorative analysis shows that lack of documentation and informal communication within the municipal set-up often leads to the application of informal work procedures which managers believe can be tapped to contribute to continuous improvement and improve compliance to formalised work procedures.

Reason et al. (Citation1998) argue that over-prescription in detailed work procedures in institutions often leads to the development and adoption of informal procedures meant to perform tasks faster. Additionally, under-prescription also results in employees developing their own procedures and routines in executing tasks. While our study did not examine the extent of over- or under-prescription of work procedures, findings on formal work procedures indicated that where the municipality may have developed policy and procedure manuals, the extent of compliance with those procedures as seen in the Auditor General’s reports over the years has been a challenge (AGSA, Citation2015/2016; 2017). Our findings also mirror this state of affairs. However, there are also glimpses of creative uses of informal work procedures. This has significance for the municipality and others like it, where perceived attitudinal and self-efficacy limitations (e.g. ability to read and understand procedures) may hamper compliance.

4.3. Experience with formalised documented procedures

To get insights on the prevalence of informal work procedures, respondents related on the extent to which employees in the municipality have applied informal work procedures to perform their tasks and the extent to which the informal work procedures can be helpful. Evidence from the interviews explores the fact that the major contributing factor towards the adoption of informal procedures is the experience with formalised documented procedures. The findings showed a mixed response in terms of work procedures documentation. The more technically demanding departments seemed to have more documented procedures. A lot of the documented procedures were developed to comply with processes prescribed by regulation and government regulatory institutions like the National Treasury (e.g. maintenance plans, Supply Chain Management). Departments that are heavily legislated such as those dealing with human resources also seemed to have more documented procedures.

Additionally, findings show that documented procedures have not been fully cascaded down and unpacked to the level and understanding of general workers. In this sense it seems that documents on work procedures are meant for certain groups such as managers. Hence the development and use of informal work procedures.

Below are responses from managers of three different departments:

There are procedures but they are not written down. So when (one) gets inducted to the institution, (he or she) learns how to do things not because they read from somewhere but because they have been inducted and follow suit without even demanding to see where it is written. (Respondent 1)

Some are documented, some are not. But critically they are informed by the policies as policies outline how to go about certain processes without necessarily referring to them as procedure manuals. (Respondent 2)

Those that we have are documented, though we have a lot of them that are not documented. (Respondent 3)

In my department, a lot of them are documented. (Respondent 4)

Probes also revealed what seems to be a general aversion to documented procedures by employees.

Each individual knows what responsibility he/she has in terms of the task at hand. So if we can get that working I think most of the things will be covered well. This is so because most of the people do not like to deal with documentation, but as long as everyone knows their tasks, especially the supervisors who have the task of giving instructions and monitoring the employees, it will be much better. (Respondent 3)

These statements should also be taken within the context of the overall makeup of the municipality. What was clear was that whether documented or not verbal communication seems to be the overwhelming preferred route to communicating work procedures.

4.4. The role of communication

Communication is an intangible organisational asset (Malmelin, Citation2007) and is a critical element that ensures the routinisation and reinforcement of procedural compliance. “Formal communication is achieved through pre-defined channels set by organisations (Broome & Rosander, Citation2016). On the contrary, informal communication is more relational than formal. It is not backed by any pre-determined channels and can happen anywhere within the organisation. Since it is not defined by any channels, it is without any paper trail or official documentation.” In the municipality, employees are made aware of formalised procedures through numerous scheduled measures ranging from monthly departmental information meetings, active participation in the business plans, workshops and refresher courses as well as the provision of documented work manuals to employees although this seems to be more of an exception than the norm. The municipal norm in this regard is through verbal instructions, information-sharing sessions and informal meetings. In one department, the informal information-sharing sessions are run by the adoption of “tools box talk” on an ad hoc basis where the manager and his/her subordinates gather and discuss the best steps and mechanisms to carry out their daily tasks. These can be classified as informal because they are not scheduled and documented. The practical examples of communication indicate a preference for informal communication. To further buttress this point some respondents stated:

… I think each department has to create a session whereby they meet regularly because constantly pushing paperwork in front of people is not going to work. I think sitting down with people, discussing issues around what is happening is going to help rather than just telling them what to do. (Respondent 4)

… we will make sure that sub-meetings take place as they are very important because the major reason with these meetings is to pick up problems early before they erupt to bigger problems. (Respondent 5)

We have information sharing meetings at institutional level and at departmental levels we have monthly management meetings where we discuss how things are done and to correct deviations. (However) those are not written procedures, they are just spoken (by the word of mouth). (Respondent 1)

The value of these communication streams must be highlighted especially in terms of the composition of the workforce in the municipality and in many other municipalities in the district under investigation. Average literacy rates in the municipality could be a consideration especially given that only about 15% and 9% of the population in the district have completed grade 12 or higher, respectively (AGSA, Citation2015/2016, p.196). In this case, apart from perhaps attitudinal dispositions to the use of work procedure manuals, capability and self-efficacy perceptions will limit the awareness and application of work procedures by many employees should these procedures not be verbally communicated.

Also, the preference for informal communication or knowledge sharing is not unique to this South African local government experience, as is explored in the Chinese “guanxi” practice (Davison et al., Citation2007) and the Japanese “quality circles” (Blaga & Boer, Citation2014). Much like with the Chinese example, these information sessions seem to be a recognised opportunity for communication and communicating procedures. However, there seems to be a dearth of a uniform deliberate municipality approach to consciously embrace these as opportunities to build a compliance-driven climate.

4.5. Feedback and continuous improvement

Although the managers expressed a difficulty in monitoring all the procedures (since a lot of them are not documented), interviews showed that informal work procedures are taking place in the municipality. This was further buttressed by assertions from two respondents who reiterated that many of their staff, especially those that are experienced in their jobs, hardly revisit those work procedure manuals that are documented. This also gives room for the application of informal work procedures. To further buttress this notion, an assertion from the texts justifies that there are a lot of informal work procedures and this has to do with culture of the institution:

… there is a culture of doing things informally. As long as there is a gap, employees will come up with their own informal ways of carrying out tasks. More often than not, as managers we are concerned with the outcome. If that particular procedure achieves an outcome, it does not matter how that person has done it so we leave it up to them. (Respondent 1)

This suggests that managers may be interested in the end goal which sometimes is to the detriment of compliance to work procedures. However, we also argue that end goal interest can foster important lessons for compliance as argued by Reason, et al., (Citation1998, p. 291). A conscious and deliberate effort in managing these informal procedures (especially those without immediate consequences) allows for learning and innovation in setting what we have termed in this article as a “compliant-driven climate”.

A noteworthy detail here is that the above respondent manages a department where most of the staff members are menial workers. Employees in this position tend to have low literacy levels. As such, the unit adopts a creative approach with the “tools box talk”, where staff gather and discuss the best steps (allowed within the limits of the prescribed dictates) to carry out their daily tasks. Text reveals important uses of this forum, first as a participatory feedback learning process:

… we say, this is the task … do you feel how you are doing it achieves the results that we desire? They will come up with ideas.

The second is a continuous improvement avenue:

… you then suggest how things should be done to improve the process, because you have to do things differently to achieve different results and that is the mentality I have introduced when I came here.

Another example of an informal procedure from textual analysis is where the municipality prioritises the municipal database of unemployed graduates as an important step in recruitment.

It’s very little of informal procedures that I will say … but I get reminded of one of the procedures, informal as it may be … we are saying let’s look into this data-base of people within this area … coming from the wards … so that is informal and it is not recorded anywhere so it can assist to a large extent … (Respondent 4)

This is indicative of where managers can allow employees to act within certain discretionary boundaries as far as the limits of the law will allow. This has implications for compliance by identifying compliance boundaries and allowing employees discretion within those boundaries.

From the discussions so far, there is clear indication that informal work procedures are prevalent in the municipality. The principal question of this article is whether compliance value can be harnessed from these informal procedures. We argue that given the unique context of this municipality not only do informal procedures have value, they also show promise as innovative tools in growing a compliant-focused climate or, as one of the respondents proposes, developing “a mentality” of compliance.

Based on literature and these findings we suggest that municipalities can grow a compliance-driven work climate by nurturing the indirect assimilation of values through routine behaviours (such as “tools box” meetings and frequent information sharing) which reflect the organisation’s values as a commitment to compliance. We also argue that informal procedures as defined by us will provide routinised, non-regimented and verbally articulated avenues through which employees are allowed certain levels of discretion to push the envelope and (through trial and error) learn from mistakes towards meeting compliance requirements.

4.6. Conscious and deliberate openness to the compliance role of informal procedures

Compliance is a heavy term in local government as the emphasis placed on local government compliance and clean administration has led to adverse attitudinal dispositions of local government officials towards regulatory requirements in terms of compliance (PARI, Citation2015, p. 15; Dlamini, Citation2016). Our article takes the view that dispositions towards compliance should be less about the material outcomes of audit compliance, but more about using more of the informal organisation, in particular informal work procedures, to build a compliance-driven climate or culture. To this end, based on textual data we identify an important theme which is the need for a conscious and deliberate openness by managers to the use of informal procedures.

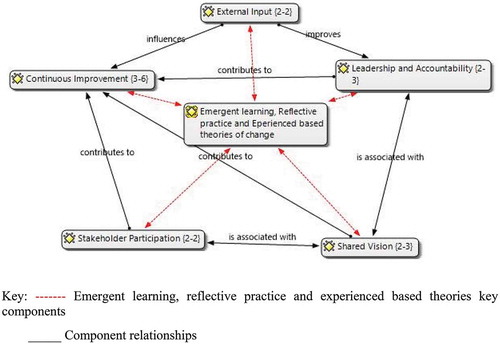

Here we identified three categories for assessment: recognition of emergent learning, experienced-based theories of change and engagement in reflective practice. Figure shows analysis drawn from Atlas.ti which links responses-related emergent learning, reflective practices and experienced-based theories of change to various aspects that contribute to effective management of informal work procedures towards growing a compliant-driven climate.

Figure 2. Factors influencing emergent learning, reflective practice and experience-based theories of change

The figure explores the relationships which exist among the aspects attributed to emergent learning, reflective practice and experienced-based theories of change. Content analysis revealed that compliance culture can be cultivated through the sharing and tapping of the skills that emanate from informal work procedures. Important aspects such as stakeholder participation, shared vision within an institution, continuous improvement, external input as well as leadership and accountability influence one another to ensure that employees and other stakeholders play a role in creating or changing the organisational culture.

4.7. Recognition of emergent learning

As suggested earlier, emergent learning can be seen as new action which comes from practice at the edge of chaos (Mason & Dobbelstein, Citation2016). Management recognition of emergent learning will encourage knowledge sharing of procedural best practices, create opportunities for informal sharing of work procedures and cultivate a culture that is supportive of new approaches generated through a focus on failures and unintended outcomes as opportunities for new approaches (Serrat, Citation2017). While findings show evidence of such management support of emergent learning through the “tool-box talks”, further scrutiny on the matter reveals that this is not a municipal-wide phenomenon.

4.8. Experience-based theories of change

For our study, an experience-based theory of change highlights the role of employees in creating or changing organisational culture. Serrat, (Citation2017, p. 60) associates intellectually curious employees with the ability to “develop experience-based theories of change and continuously test these in practice with colleagues”. This point is buttressed by one respondent who noted that people are resourceful naturally and have natural wisdom and that sometimes people thought to be uneducated have better and effective ways of carrying out tasks even though they are not documented. In this regard, the insights from employees are important in tapping into unique skills to carry out tasks and mainstreaming them as routine practice culture within acceptable standards. This will engender a compliance-driven climate that encourages participation of employees through the sharing of procedures with least violation or error implications.

For our research purposes we view this as a double-edged management responsibility. First, a responsibility to recognise the better and effective ways of carrying out tasks, which is integral to the desired change expected. Second, possessing the skill to effect such change through a commitment to bottom-up information sourcing and sharing. This skill will be based also on the knowledge and understanding of the development and the application of work procedures.

In this regard, findings show that the leadership and expertise of the management in relation to development of work procedures is limited. The respondents agreed that they have a bigger role to play in developing and crafting work procedures to suit their different environments and circumstances. With regard to training on work procedures and processes, texts analysis uncovered that managers rely on their previous experiences to develop formal work procedures and monitor employees’ compliance to them. Three out of five respondents reiterated that they have not received any formal training and only two noted that the standard operating procedures they crafted were developed through the experience they have gathered over the years working in municipalities. Skill and expertise limitations present a challenge in developing a culture of compliance as managers might have limited skills in terms of developing and monitoring work procedures (formal or informal). According to one manager:

Since I arrived here there has never been a session that was called to develop procedures. By the way it is every manager`s responsibility to develop procedures according to the area of expertise in which he/she is in charge of because sometimes one has to tailor work procedures to suit specific environments.

To reflect, there is limited training available to managers on the development and application of work procedures. However, managers are expected to develop and monitor the use of work procedures. For many, what they know is through years of experience of working in municipal government and some of the learning is consolidated in some of the informal approaches managers use in the communication and monitoring of work procedures towards compliance.

4.9. Reflective practice

Reflective practice is about taking a step back and contemplating the discrepancy observed or experienced between what occurs and what was expected (Osterman, Citation1990). The respondents agreed that there was a lot of constructive and effective input which can be drawn from informal work procedures to improve compliance and performance of the municipality. One respondent noted that continuous improvement of work procedures ensures that employees develop and improve the manner in which they carry out day-to-day tasks. This means that no matter how good some employees might be in carrying out tasks there is need to continue learning as there are always changes that require new skills and techniques. The respondent went further to assert that it is imperative for the municipality to find new measures based on the informal work procedures to carry out tasks and find the best ways to bring change. Despite these views, further investigation shows that while much of work procedures are largely informal in the municipality a deliberate attention to the opportunities they present through encouraging reflective practice is lacking.

To highlight best avenues for reflective learning, Serrat (Citation2009) suggests that reflective practice flourishes in teamwork where people experience a high level of psychological safety and trust. From our findings, while interviewees point to regular informational sessions and briefing sessions with employees, the extent to which these sessions can be considered spaces which engender psychological safety and trust is not known. However, the description of the tool box talk sessions presents perhaps a semblance of such a team activity that is participatory, reflective and feedback conscious.

Before they go … we gather at the back of the yard where we discuss and consult with employees to ask whether what they do achieve the results. At the end you suggest how things should be done to improve. If you want to have different results, you got to change the way you do things and that is the mentality I have introduced since I arrived. One on one talk is also important because some individuals have difficulties in understanding so they need attention on a one on one basis. (Respondent 1)

5. Conclusion and recommendation: practice experience on the compliance value of informal work procedures

We argue that the first step in using formal procedures for compliance is ensuring the ability of end users to understand and imbibe procedural requirements. We have argued that more than breaking down these requirements in understandable forms, allowing space for informal procedures will encourage the identification and use of compliance-based emergent learning and theories of change coming from end user experiences. Moreover, informal work procedures have the potential to feed much needed information into the development and continuous improvement of official work procedures.

A compliant culture is not devoid of informal work procedures; in fact we argue that it is imperative to it. Internal control systems and organisational control (formal compliance with policies and procedures) aim to achieve compliance, efficiencies, performance and limit unethical conduct and corrupt practices. Evidence from the case study shows that informal procedures and processes seem to be the default in practice. The point of departure of the article is in presenting experiences that promote the compliance value of informal work procedures.

Finally, the article identifies important qualifications of informal procedural measures that municipal management must highlight and promote towards growing compliance in local government management practice. It argues that compliant-based climates can be fostered through informal work procedures. To achieve this, organisations must be able to identify distinctions between:

informal work procedures in need of formalising

informal work procedures needed for building appropriate climate for compliance

informal work procedures that are detrimental to compliance

The first and second can be termed “safe”. To routinise “safe” informal procedures we recommend a conscious effort towards identifying emergent learning, experience-based theories of change and reflective practice through regular meetings and verbal interaction with staff to identify and encourage informal work procedures that have compliance value.

Acknowledgement

This work was partially supported by the UIC Grants (Nos. R1050, the Zhuhai Premier Discipline Grant).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ogochukwu Nzewi

Ogochukwu Nzewi is an Associate Professor in the Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Management and Commerce, University of Fort Hare. Her research interests are versatile in the broader area of research into the theory and evolution of institutions as social and political actors within the polity. This article was based on field work findings from her National Research Foundation grant examining the utilisation of work procedures in local government.

Modeni Sibanda

Modeni Sibanda is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Management and Commerce at the University of Fort Hare. He has researched and published articles on governance, regional integration, intergovernmental relations, organisational culture and local governance.

Nqobile Sikhosana

Nqobile Sikhosana is a doctoral student of the Department of Public Administration and worked as a research assistant and corresponding author on the project.

Maxwell Sentiwe

Maxwell Sentiwe is also a doctoral student and a research assistant on the project.

References

- AGSA. (2014/2015). Integrated Annual Report. Retrieved from https://www.agsa.co.za/Reporting/AnnualReports.aspx

- AGSA, (2015/2016). MFMA annexure 2 audit opinions over 5 years. Retrieved from https://www.agsa.co.za/Documents.

- Antonsen, S., Almklov, P., & Fenstad, J. (2008). Reducing the gap between procedures and practice – lessons from a successful safety intervention. Safety and Science Monitor, 12(2), 1–16.

- Ariel, B. (2012). Deterrence and moral persuasion effects on corporate tax compliance: Findings from a randomised controlled trial. Criminology, 50, 27–69. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00256.x

- Atieno, O. P. (2009). An analysis of the strengths and limitation of qualitative and quantitative research paradigms. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 13, 13–18.

- Benedek, P. (2012). Compliance management – A new response to legal and business challenges. Acta Polytechnica Hungarica, 9(3), 135–148.

- Blaga, P., & Boer, J. (2014). Human resources, quality circles and innovation. Procedia Economics and Finance, 15, 1458–1462. doi:10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00611-X

- Brodbeck, P. W. (2002). Complexity theory and organisation procedure design. Business Process Management Journal, 8(4), 377–404. doi:10.1108/14637150210435026

- Broome., M., Ko., S., & Rosander, E. (2016). The role of formal internal communication in organizational identification: A case study of two Swedish offices. Sweden: Jonkoping University.

- Cheng, L. O., Yin, L., Wenli, L., Holm, E., & Zhai, Q. (2013). Understanding the violation of IS security policy in organisations: An integrated model based on social control and deterrence theory. Computer Security, 39, 447–459. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2013.09.009

- Chwieroth, J. M. (2012). “The silent revolution”: How the staff exercise informal governance over IMF lending, The Review of International Organizations, Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/46623

- Connolly, L. Y., Lang, M., Gathegi, J., & Tygar, D. J. (2017). Organisational culture, procedural countermeasures, and employee security behaviour: A qualitative study. Information and Computer Security, 25(2), 118–136. doi:10.1108/ICS-03-2017-0013

- Davison, R. M., Ou, C. X. J., & Martinson, M. G. (2007). Interpersonal knowledge in China: The impact of Guanxi in social media. Information and Management, Retrieved from www.sciencedirect.com/article/pii.

- Dlamini, P. (2016). Clean audit won’t fix road. Times Live.

- Dyre, L., Tabor, A., Ringsted, C., & Tolsgaard, M. G. (2017). Imperfect practice makes perfect: Error management training improves transfer of learning. Medical Education, 51(2), 196–206. doi:10.1111/medu.13208

- Fairbrass, A., Nuno, A., Bunnefeld, N., & Milner-Gulland, E. (2015). Investigating determinants of compliance with wildlife protection laws: Bird persecution in Portugal. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 62(1), 93–101. doi:10.1007/s10344-015-0977-6

- Goebel, S., & WeiBenberger, B. W. (2017). Effects of management control mechanisms: Towards a more comprehensive analysis. Journal of Business Economics, 87(2), 185–219. doi:10.1007/s11573-016-0816-6

- Helmreich, R. L. (2000). On error management: Lessons from aviation. BMJ, 320, 781–785.

- Hsieh, N., & Shannon, S. F. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hu, Q., Dinev, T., Hart, P., & Cooke, D. (2012). Managing employee compliance with information security policies: The critical role of top management and organisational culture. Decision Science Journal, 4(4), 615–660. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5915.2012.00361.x

- Ifinedo, P. (2014). Information systems security policy compliance: An empirical study of the effects of socialisation, influence, and cognition. Information Management, 51(1), 69–79. doi:10.1016/j.im.2013.10.001

- Kay, F. M., & Gorman, E. H. (2012). Developmental practices, organisational culture and minority representation in organisational leadership: The case of partners in large US firms. The Annals of American Academy of Political and Social Science, 639(1), 91–113. doi:10.1177/0002716211420232

- Lange, B. (2002). The emotional dimension in legal regulation. Journal of Law and Society, 29(1), 197–225. doi:10.1111/1467-6478.00216

- Malmelin, N. (2007). Communication capital modelling; corporate communications as an organizational asset corporate communications. An International Journal, 12(3), 298–310.

- Mason, R. B. (2007). The external environment`s effect on management and strategy: A complexity theory approach. Management Decisions, 45(1), 10–28. doi:10.1108/00251740710718935

- Mason, R. B., & Dobbelstein, T. (2016). The influence of the level of environmental complexity and turbulence on the choice of marketing tactics. Journal of Economics and Behavioural Studies, 8(2), 40–55.

- Murphey, K., & Tyler, T. R. (2008). Procedural justice and compliance behaviour: The mediating role of emotions. European Journal of Psychology, 38, 652–668. doi:10.1002/ejsp.502

- Nombembe, T. M. (2011). Implementing key internal controls to eliminate undesirable audit outcomes. Retrieved from http://www.agsa.co.za/portals/O/AG/implementing_key_internal_controls_to_eliminate_undesirable_audit_outcomes.pdf

- Osterman, K. F. (1990). Reflective practice: A new agenda for education. Education and Urban Society, 22(2), 133–152. doi:10.1177/0013124590022002002

- Paine, L. S. (1994). Managing for organisational integrity. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 106–117.

- Praino, G., & Sharit, J. (2016). Written work procedures: Identifying and understanding their risks and a proposed framework for modelling procedure risk. Safety Science, 82, 382–392. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2015.10.002

- Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), (2015). Red Zone Municipalities Investigation (2013/2014): draft report. Johannesburg: South African Local Government Association.

- Reason, J., Parker, D., & Lawton, R. (1998). Organisational control and safety: The varieties of rule-related behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 71(4), 289–304. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1998.tb00678.x

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

- Safa, N. S., Solms, R. V., & Furnell, S. (2016). Information security policy compliance model in organizations. Computers & Security, 56, 70–82. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2015.10.006

- Schlager, E. (2005). Getting the relationships right in water property rights. In B. R. Bruns, C. Ringler, & R. S. Meinzen-Dick (Eds.), Water rights reform: Lessons for institutional design (pp. 27). Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Serrat, O. (2009). Building a learning organisation. Journal of Asian Development Bank (ADB).

- Serrat, O. (2017). Building a Learning Organization, Knowledge Solutions, Asian Development Bank. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-0983-9_11

- Singh, V., Bains, D., & Vinnicombe, S. (2002). Informal mentoring as an organisational resource. Retrieved from http://www.researchgate.net/publication/223148356-informal_mentoring_as_an_organisational_resource. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2002/er01)

- Singhapakdi, A., & Vitell, S. J. (2007). Institutionalisation of ethics and its consequences: A survey of marketing professionals. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(2), 284–294. doi:10.1007/s11747-007-0030-8

- Squires, J. E., Moralejo, D., & Lefort, S. M. (2007). Exploring the role of organisational policies and procedures in promoting research utilisation in registered nurses. Implementation Science, 2(17), 1–11. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-2-1

- Statistics South Africa, (STATSA). (2011). Census 2011. Retrieved from https://www.statssa.gov.za/P030142011.

- Statistics South Africa, (STATSA). (2016). Community survey 2016 provinces at a glance/statistics South Africa. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- Stouthuysen, K., Slabbinck, H., & Roodhooft, F. (2017). Formal controls and alliance performance: The effects of alliance motivation and informal controls. Management Accounting Research, 37, 49–63. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2017.03.002

- Tyler, T. R. (1990). Why people obey the law: procedural justice, legitimacy and compliance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Vance, A., & Siponen, M. T. (2012). IS security policy violations: A rational choice perspective. Journal of Organisational End User Computing, 24(1), 21–41. doi:10.4018/joeuc.2012010102