Abstract

Despite the remarkable ART coverage and associated benefits, people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWH) require home care at the stage IV of HIV progression. Thus, home-based care (HBC) remains an important component of caregiving to PLWH in rural communities, but research on its social aspects is declining. This study explored experiences of households that care for PLWH in the ART era using a case study of Nyamakate resettlement area, Zimbabwe. Data were gathered using household interviews, key informant in-depth interviews, observations and focus group discussions. Most of the households had extended families and the highest number of household members was 13 people. Three family typologies cared for PLWH and these are nuclear, extended and “grandparent” households. Caregivers struggled to offer adequate care due to a number of challenges including lack of income, food shortage, transport problems and burden of care. ARVs were provided free of charge by government and an NGO seldom supported PLWH with food handouts. In conclusion, the HBC across the household structures continue to be stressed by the challenges associated with caring for PLWH even though they are on ART.

Public Interest Statement

Although antiretroviral drugs reduce duration of advanced AIDS morbidity, there is still neeed to care for the terminally ill especially in resource constrained rural areas. This research engaged with 14 households that were caring for terminally ill people who were on drugs in order to understand their expereinces. We found that the structure of households determined the care-givers experiences of caring for HIV infected people. Households with nuclear families tended to be well off and could manage the caring and productive duties. While multi-generational households were characterised by large numbers of children and the aged, care giving and productive roles were a struggle. Care-givers struggled to offer adequate care due to a number of challenges including lack of income, food shortage, transport problems and burden of care. Despite antiretroviral therapy, rural households in Nyamakate Zimbabwe are struggling to cope with the demands of care giving to patients on drugs.

Disclosure statement

We have no competing interests to declare. There are no financial or other profit benefits to be realised from this work other than academic merit.

1. Introduction

Western ideology postulate that a household is supposed to accommodate a nuclear family, which is characterised by people that share direct blood connection. This has led to a narrow definition of household as a person or group of persons, related or unrelated who live together and share a common source of food (FAO, Citation1996). However, not only is the household a production but it is also a consumption, social and demographic unit. This paper adds palliative care to the function and key characteristic of a household unit. Caring for people on ART is increasing dependence on social networks, and the family network is the first point of call as the basic social unit . However, HIV and AIDS have had a long history of modifying the household structure. Before Anti-Retro Viral Therapy (ART) scholars were concerned with the growth of child and female-headed households (Evans, Citation2005; Lindayani, Chen, Wang, & Ko, Citation2018; Tanyi, Pelser, & Okeibunor, Citation2018). With the shift in the burden of care after the advent of ARTs few studies from Southern Africa, have analysed the experiences of households in caring for people on ART. We have not come across a study on care post-ART in Zimbabwe. Hence, this study’s objective is to examine ways that household structures have been modified and caregivers experiences of caring for people living with HIV and AIDS in the Nyamakate area in Zimbabwe. The study shades an in-depth understanding of how HIV and AIDS reshape household’s structure.

Evidence suggests that increasing numbers of patients are being initiated on ART in Zimbabwe (Banks, Zuurmond, Ferrand, & Kuper, Citation2017). Literature highlights the need to control HIV and care for those on ART, and identifies three possible solutions to dealing with the demand for care which are; task-shifting, the training of new mid-level medical workers, and the use of members from the community in a variety of roles as “community health workers” (Campbell et al., Citation2013; Treves-Kagan et al., Citation2016). In resource-limited countries such as Zimbabwe, the use of community members as caregivers is widespread. The Zimbabwean policy promotes diverting terminally ill patients from hospitals to home care services (Ferrand et al., Citation2017), increased number of people will find themselves living with AIDS at home while on ART. In Zimbabwe, studies have documented that rural households disproportionately carry the HIV burden of morbidity and mortality as terminally ill people often migrate to rural areas for care (Campbell et al., Citation2013). Literature has shown an increase of multi-generational households due to the high mortality amongst the middle age group as a result of HIV and AIDS (Hosegood, Preston-Whyte, Busza, Moitse, & Timaeus, Citation2007; Tanyi et al., Citation2018). AIDS has modified the household structure and there is a high prevalence of female-headed households due to women being widowed (Ntozi & Zirimenya, Citation1999; Schatz, Madhavan, & Williams, Citation2011).

2. Background

Southern Africa has made remarkable progress in attaining anti-retroviral (ARV) distribution targets. Out of 12.5 million people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWH) in the region, more than 5.7 million of them were on ARVs by 2015 (Williams et al., Citation2015). Zimbabwe has experienced a declining HIV prevalence from 27.2 in 1998 to 14.0 in 2012 largely due to the ART programme (Mutasa-Apollo et al., Citation2014), however, the disease is still endemic. In Zimbabwe, the National Opportunistic Infection/Antiretroviral Therapy programme was established in April 2004 (Maposa, Citation2016). Since then, ARVs have been provided free of charge from public health institutions and efforts have been made to decentralise the services to the clinic level (Maposa, Citation2016).

As of 2014, about 51% of HIV positive people were on ART in Zimbabwe (Banks et al., Citation2017). ARVs are known to prolong and improve the lives of PLWH through reductions in the rate of HIV disease progression, opportunistic infections, morbidity and deaths (Banks et al., Citation2017; Levy et al., Citation2006). Thus, one might argue that with ART HBC should not be an important issue since it is expected that people on the drugs are able-bodied and do not require much care. However, studies have identified the need for palliative care amongst people on ART who have stage IV HIV (Levy et al., Citation2006; Lindayani et al., Citation2018; Tanyi et al., Citation2018). PLWH at the stage IV of HIV progression were found to demand high levels of spiritual and financial support in Indonesia (Lindayani et al. 2017). A number of studies from South Africa have demonstrated the importance of the link between family structure and its socio-economic status and quality of care to PLWH in the household (Hosegood et al., Citation2007; Kagee et al., Citation2011). According to Wringe and others (Citation2010), the concept of home care has changed after the introduction of ART shifting from “care towards a dignified death” to “continuum of care”. The continuum of care approach has been defined by WHO as a network of resources and services that provide holistic and comprehensive support for the ill person and family caregivers (Wringe et al., 2010).

Before ART, home-based care (HBC) program was the leading avenue of care for PLWH exceeding hospitals and clinics. A number of donors, governments and researchers focused and supported HBC in resource-poor countries, but this support has declined with the introduction of ART. Health practitioners and policymakers are not paying much attention to the fact that ART has been shifting treatment from hospital admissions to outpatient setting, literally dumping patients on the households (Levy et al., Citation2006). There is need to consider the challenges and experiences of home-care for PLWH in resource-poor settings in the era of ARVs. Furthermore, poverty and environmental change compromises home care through food insecurity (Chimhowu & Hulme, Citation2006), compromised access to water and sanitation (Mbereko, Scott, & John Chimbari, Citation2016), lack of funds for accessing health services (Levy et al., Citation2006, Lindayani et al., 2017). Appropriate palliative care could alleviate care-related stress (Banks et al., Citation2017; Lindayani et al. 2017). There is limited contemporary research form Zimbabwe on this subject and the potential contribution of the study to ART outcomes warranted this research.

2.1. Description of the study area

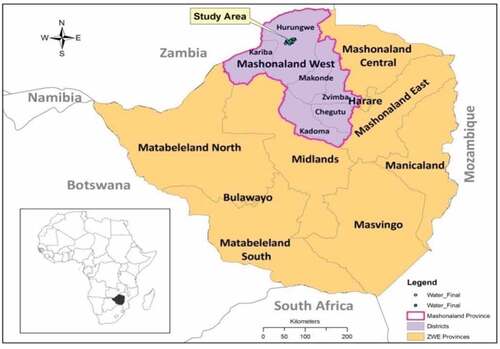

The study was conducted in the Nyamakate resettlement area in Mashonaland west, Zimbabwe (Figure ), between 2011 and 2015. The Nyamakate resettlement is situated in the north-eastern part of Zimbabwe along the Harare-Chirundu highway (trucking corridor).It is located 60 km north of Karoi town. In the north, it borders with Hurungwe and Charara safari areas and Vutismall-scale commercial farms in the south (Figure ). The study area is in natural region four characterised frequent seasonal droughts and severe dry spells during the rainy season. The region supports semi-extensive agricultural systems focusing on livestock, drought resistant fodder crops, cotton and tobacco. The farming system is mainly supported by household labour rather than hired workers.

The Nyamakate community was officially recognised by the government of Zimbabwe in the early-1980s, and this is when infrastructural development started (Mbereko, Scott, & Kupika, Citation2015). Its population grew from 2,500 people in the early 1980s to about 13,000 in 2000 (Chimhowu & Hulme, 2006). The post-mid 1985 planned resettlement of landless black people resulted in a multi-cultural society with people from different ethnic groups being settled in the area. At this time the clinic, schools, water points and the major road networks were constructed. The clinic has a catchment area that stretches for a radius of about 22 km at the furthest point. Karoi is the urban area that provides medical, administrative, social and economic services to the study area. The society is dominantly patriarchal and roles are defined as either feminine or masculine. The dominant economic activities are farming, mining, piece work, artisan contracts and petty trading of merchandise.

HIV and AIDS are pandemic in the Nyamakate resettlement area (Mbereko et al., 2017). The stress posed by HIV and AIDS, drought, insecure land tenure, malaria and poor commodity prices were shown to undermine livelihoods in the Nyamakate resettlement area (Chimhowu and Hulme, 2006; Mbereko et al., Citation2015). In order to cope with the stressors, communities respond by diversifying crop varieties and engaging in off-farm activities such as retail trade and transport sector (Chimhowu & Hulme, 2006). Although households can engage in off-farm activities they retain the hold on the 5 ha plots of land and continue crop production. The selection of the crop to produce is determined to a large extent by anticipated rainfall patterns, market prices and availability of labour (Mbereko et al., Citation2015). State and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) programmes have assisted different populations (such as PLWH and the poor) to cope with livelihoods stressors (Chimhowu & Hulme, 2006).

3. Materials and methods

Multiple data collection visits were done in 2011 and follow up data collection exercise was done in 2015. The follow up data collection was done in 2015 because this is when the researchers got further funding. Nine out of the 32 villages from the Nyamakate area were conveniently sampled, taking into account the presence of HIV and AIDS patients known to the clinic stuff, accessibility, distance to and the from clinic and availability of accommodation for the researchers and caregiver consent to participate in the study.

This case study used qualitative research methods to explore subjectively lived experiences of households caring for PLWH. In-depth interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs) and observations were used to collect data in 2011. In-depth interviews were done in 14 households from 4 villages. The caregivers were targeted as the respondents. The in-depth interviews gathered data on household structure, illness, treatment, challenges. The face to face in-depth interviews were done using an unstructured interview guide. These were deemed appropriate to gather this data because they allowed exploration of themes that are unique to specific households.

The selection criteria for the 14 families enrolled into this study was based on the following; (i) participants were resident in the Nyamakate area, (ii) at least a person living with HIV within the household/household that had experienced an HIV related death within two months and (iii) the HIV positive person must have been sick to a level that they were incapacitated and needed to be cared for, (iv) the caregiver had to be above 18 years of age. It should be noted that no clinical tests were done to determine HIV seropositivity thus, an individual’s status is based on self, village health workers or relatives reporting results of patient as tested positive to HIV. This study was part of a larger study that recruited 40 participants; however, detailed follow-ups were done with 14 households that met the selection criteria above. Interviews were conducted until no new themes emerged with the 14 caregivers. The accounts of those indirectly and unaffected by HIV and AIDS were excluded from this paper. Purposive sampling was used to select the 14 households with first-hand experience of caring for someone with HIV and AIDS.

Participants for the focus group discussion were drawn from five villages that did not participate in the in-depth interviews. Six out of the eight focus group discussions (FGDs) were done with men and women separately, from three villages. Due to logistical issues, two FGDs were done with men and women combined, from two villages. Convenient sampling was used to select FGD participants. The village heads helped with the recruitment of FGD participants. The researchers set out an inclusion criteria stating that: (i) the person had to be a resident of that village; (ii) the person must be a household head; and (iii) preference was extended to household heads that had experienced an HIV related illness or death within the household. In terms of our exclusion criteria, we ensured that no two people from the same household participated in the same FGD, while all community leaders were excluded from the FGD sample.

Non-participatory observations, recorded as field notes, were used as a complementary method of gathering data. Observations enable researchers to watch events as they unfold rather than relying on someone else to narrate the events to them (Kitchin & Tate, Citation2000). The people were aware they were under observation and did not object. The researchers participated in one village health workers’ meeting and several patient follow-ups and ARV disbursement sessions at the clinic in September 2011. This data was also recorded as field notes.

3.1. Data analysis

All data were translated verbatim then transcribed and entered into NVivo. The transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis with the help of NVivo nodes which were used to organise and store data in sub-thematic categories. The researcher therefore manually interpreted the data.

4. Results

4.1. HIV and AIDS affected households’ socio-demographic characteristics

Out of the 14, HIV and AIDS affected households, four were headed by females. Out of the four female household heads, three were widowed and the other a divorcee. The household heads’ age varied from 32 to 78 years with an average of 56.5 years (Table ). Female household heads were older, with a minimum of 51 years old, while for male-headed households it was 32 years old. The average age of family members of female-headed households was lower compared to male headed households. With the exception of five households, the rest (9) were extended families that included people that were not part of the nuclear family staying in the homestead. Amongst the interviewed households, household 8 had the highest number of members (13 people), while households 5 and 12 had the most number (9 each) of nuclear family members residing in the household. Six of the 14 household heads had reached primary education, three had never been to school, and the others had tertiary education. The data from FGDs show that education was not regarded as important in livelihoods investment. Having a secure source of money to invest into agriculture from off-farm activities was considered more important. FGD participants showed that household labour force was another important factor that affected livelihoods strategies. They indicated that a household with a number of active members that can work in the fields was better than those with grandparents and young children.

Table 1. The socio-demographic profile of the households in the Nyamakate area

A local leader indicated that the mandate for Nyamakate resettlement area, like all other government resettlements, is to produce grain crops to feed the nation. We observed grain inputs being distributed by the rural council on behalf of the government. Amongst the in-depth interview respondents, agriculture was the dominant livelihood strategy amongst other off-farm activities. It was reported in FGDs that tobacco farmers had higher income as compared to those who produced grain crops. The lower income was subscribed to the lower market prices for grain crops as compared to tobacco. FGD participants further indicated that production of grain crops was risky due to the low market prices being offered by the Grain Marketing Board and the frequent droughts. However, tobacco production was reported as demanding more labour than grain crops hence those who could afford the input costs had higher income than other farmers. The income varied greatly (Standard deviation of 399.69) with a minimum of US$20 and a maximum of US$800 and an average of $158.57. Petty trading, remittances, piece-jobs and cross border trading were reported as important off-farm sources of income for households in the Nyamakate area.

4.2. Typologies of family structures for households caring for PLWH

Out of the 14 families caring for PLWH, seven had members on antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), six had terminally sick people not on ARVs, and one experienced a death due to HIV and AIDS (she initiated ART but stopped) during the course of the study. Out of the experiences of the 14 households living with people infected by HIV and AIDS, three family typologies were drawn and these are care of PLWH in a nuclear family setting, households caring for members of the extended family, and grandparents’ families that had experienced multiple episodes of HIV and AIDS across generations.

Five of the 14 households were caring for PLWH within a nuclear family setting. It was noted that in households where either or both parents were sick, livelihoods strategies were negatively affected and income levels were affected. Such families recruited a mature relative from the extended family to provide care and engage in productive activities. Relatives that were usually preferred as caregivers included school drop-outs, school going children in need of fees (if the affected household can pay for fees), siblings, and grandparents to the household. Of the five households caring for the household head, only two could afford engaging paid labour to assist with caring duties and productive activities. It was reported that a family member was tasked with the primary caregiving duties while the hired help would engage in productive work and domestic duties like fetching water, firewood and washing. Those families who could not afford paid labour relied on social networks. Neighbours or relatives would assist the family to care for the sick and donate food to the household. It was reported that nuclear families usually sell some assets in order to care for the family member who is sick. Selling of big assets was problematic for widows since they had to consult with the husband’s family first. One man explained in an FGD that the problem with AIDS is that the husband usually dies first, living control of the family to his kins and the wife jointly. The assets are held in trust for the children and they should not be sold before the children are of age. Some participants indicated that nowadays people are greedy and heartless since they overprotect the deceased’s assets to buy time for the widow to die for them to dispossess the orphans. Household 14 is a typical household caring for the household heads.

Household 14 was recruited in the study in November 2011. The household was in Juliet village. The household was made up of a nuclear family headed by the husband with a wife and three children (Figure ). The husband was a retired electrical technician who had turned to small-scale commercial agricultural farming in the Nyamakate area. With the help of hired labour, the household was into tobacco farming and only produced grain crops for domestic consumption. Their monthly income was ±$800USD per month (Table ). Both the wife and husband were HIV positive and on ART (Figure ), and at the time of the study, the wife was very sick. It was reported that the wife’s medical condition deteriorated to being bedridden towards end of September 2011. The couple received ARVs, check-ups and treatment from the Nyamakate clinic during the doctor’s monthly visits. The husband said, “here and there we have been referred from the [Nyamakate] clinic to Karoi hospital for diagnosis [of opportunistic infections], CD4 count and treatment of conditions that are not manageable at the clinic level.” We observed that the clinic offers limited services that do not include specialised disease management, X-ray and laboratory services. It was reported by both husband and wife that when either of them is sick, it is the duty of the other to take care of the sick one. They indicated that their children help with domestic chores in the household like cooking, cleaning, fetching water and looking after the 2-year-old baby.

By mid-November, the wife’s health continued to deteriorate and the clinic could no longer manage the infections. It was reported that she was referred for specialised medical management from the clinic to Karoi District hospital and later to Chinhoyi Provincial hospital (about 170Km away) for diagnosis and treatment. The husband reported that they had to sell two cows and use part of their savings to cover for the medical and transport costs. Towards the end of December 2011, the husband’s mother who was 77 years old came to help care for the wife and to look after the children. It was reported that in the past the household had engaged a niece to help with caregiving and childminding but she eloped and left the household. The mother-in-law’s assistance was appreciated by the family since the husband could no longer cope with managing the fields, children and caregiving roles. The family reported benefiting from food handouts that were distributed to PLWH who were on the clinic’s ART roll-out programme. In a visit to the household in 2015, both husband and wife were not bedridden although the wife complained of minor pains and feeling weak on some of the days.

The households caring for PLWH from the extended family had heterogeneous realities with HIV and AIDS. Most PLWH were reported to join host households when they are already sick from urban and mining areas. The following statements demonstrate the different circumstances that PLWH joined host households:

He had his wife, but the wife ran away and she went to South Africa before the husband fell very ill. … so the day he was discharged from the hospital for home care, … we came with him here (Interview 11, 17/10/2011).

He was working in South Africa. Someone we did not know phoned to inform us that our son was seriously ill in Johannesburg. We asked them to send him on a bus to Harare. I went to fetch him in Harare then came with him here (Interview 12, 23/10/2011).

She fell sick at her husband’s family home. Then the husband’s family summoned me to their homestead. When I went there the situation was bad [the husband was also sick] and it was suggested that I bring her here for care taking (Interview 13, 23/10/2011).

My other sister was left at the township by the husband. She sent word to inform us that she had been abandoned at the township and she required to be fetched. We had to go and get her from the township with a scotch cart. When we got to the township we did not find the husband, he had already returned to Harare. He had not even paid lobola (Interview 2, 13/09/2011).

FGD and household-interview participants lamented the lack of material support from the sending communities and other relatives. FGD participants preferred caring for someone who had supported the household in the past. It was also reported that some of the extended family members would have not remitted or visited their families when they were still able-bodied and working. One old man who participated in an FGD said it is as if they were only good for burying people who would have enjoyed their lives in towns. Such attitudes were reported as negatively affecting caregiving for PLWH from the extended family who were sick and in need of care. Women who participated in an FGD were of the opinion that female relatives who engaged in sex work usually remit and take care of their parents, siblings and/or children in the Nyamakate area than those who would have eloped and started a family. It was reported that females who would have eloped and established families elsewhere lacked support from the husbands’ family. The maiden families were left with the responsibility of looking after their beloved until they pass away. It was reported that in most of the cases these women will not be on ARV treatment when they come for support. Some start ART at Nyamakate clinic, however, most of them would be wasted and have compromised chances of recovery. It was also reported that extended family members living with HIV and AIDS are not registered with the local leadership and it takes time for them to benefit from handouts or donor support. FGD participants noted that the quality of care given to a person living with HIV and AIDS depended on the care giver’s attitudes, social network, whether one is on ARVS or not and the socio-economic status of the host household.

Out of the five households that fit this family typology, we selected one case that will be discussed in detail. Household 7 was recruited into the study in July 2011 and it is in village 27a. The nuclear family has four members and two members of the extended family joined the household for care and another two by birth (Figure ). A widow who was 53 years old was the household head. She lived with two HIV and AIDS patients [a male and female] who were not her biological children (Figure ). We observed that the male was very sick and bedridden while and the female was sick and used a wheelchair for mobility. The household head stated that her brother’s son and her sister’s daughter were aged 27 and 23, respectively. The household head reported that she was born normal, but her walking ability was compromised when she became very sick. She indicated that her health had improved a lot especially after she enrolled on ART. When the female patient’s father passed away, when she was 23 years old, she stayed with her mother [Participant’s elder sister].

My elder sister who used to take care of her [the patient] had a stroke which she is not recovering from. So she came to me for caring since she was already ill. It is believed [within the family] that her HIV and AIDS illness caused my sister who is the mother to have a stroke out of stress. My brothers do not want to see or help her [patient] because she is responsible for her mother’s sickness. (Interview 17, 28/09/2011).

The household head reported that the sick male’s parents passed away when he was still in high school. At that stage, their family was staying in Harare. The household head said,

without an income, he was forced to move out of the rented house and akaenda kunojingirisa munyika ine meno iyi [he went to fend for himself in this rough country] ainge ari munhu mutsvenehameno paakapoyirawo [he was a good man but am not sure where he went wrong and contracted HIV]. (Interview 7, 28/09/2011).

She added that he was brought here by his friends, who seldom send food or money for his upkeep. Furthermore, this household receives food handouts from the local clinic. According to the household head, their major challenges include shortage of labour, patient transport to and from the clinic, food insecurity and money for further tests to be done in Karoi for the girl. She said the household’s income is erratic and she does not have major assets to sell to raise income for medical bills. My daughters engage in piece work and petty trading, but they do not release their money, we only benefit when they buy food and everyone shares.

The third household type is Grandparent structure. This household type is unique in that the household is headed by a grandparent and usually has grandchildren. It was reported that grandparents assumed the caregiving role of their sick children and grandchildren (who are usually orphaned). FGD participants highlighted shortage of labour, food and transport to take the patient to the clinic when sick or to attend the monthly doctor’s visit. The grandparents interviewed complained of painful legs and limbs, hence could not walk to the clinic. Shortage of manpower was reported as a major theme. The grandparents’ households were usually composed of people who are either too old or too young to do productive work. Some of the grandparents’ families rely on remittances. The aged household heads interviewed indicated that they do not like to rely on remittances because they preferred working the land for themselves for food.

We use the case of household 6 to understand the nuances in the experiences of grandparent households that care for PLWH and orphans (see Figure ). Household 6 is from village 27a and it was recruited into the study in September 2011. At the time of recruitment, the household was headed by a woman who was 59 years of age and had never attended school (Table ). The household relies on agriculture and remittances for survival. The household reported that they were food insecure and would eat wild edible vegetation and small animals. The 11 years old grandson had to hunt small animals such as mice, hare, squirrels, and birds, in order to get enough food to eat. The granddaughter who was 14 years old, helped in caregiving to an HIV positive toddler who was 2 years old and carried out other household duties. At the time of recruiting the household, a daughter to the household head was HIV positive and bedridden while one of her three sons had recently passed away from AIDS leaving a wife and three children. The household head assumed care for her granddaughter and grandson from her deceased son. The granddaughter was HIV positive and on medication. This granddaughter who is two years old is suffering from HIV and AIDS. She said, “She has never suckled breast milk from birth, but I think the tablets are helping her” (Interview 6, 28/09/2011). Although the mother (daughter-in-law) to the grandchildren was alive she was reported to be very sick and being cared for by her own family.

When we went for the data collection trip in 2015, the bedridden daughter to the household head had passed on in 2014, leaving two orphaned children, one was HIV positive. The household head reported that she had fallen sick after discontinuing ARVs. It was becoming too much for her to be taken to the clinic in a wheelbarrow or borrowed scotch cart for about 9Km. The grandmother lamented over the burden of care, she said, “The mother [her daughter] of these two only told me their totems but I do not know their fathers … yes they are from different fathers. Worse, their fathers never paid even a cent or bought me groceries” (Interview 6, 28/09/2011). The old grandmother had a number of challenges including lack of transport to escort the HIV positive for medical check-ups and getting drugs from the clinic, shortage of food and the burden of caring for five children without an income.

4.3. ART and the Nyamakate community

The community is well-informed about the doctor’s monthly visits and they go to the clinic on these occasions or bring their relatives to receive the anti-retroviral drugs. All representatives of the HIV and AIDS affected households sampled for this study testified that their patients were receiving treatment and support from the clinic. GOAL (an NGO) was reported to be supporting the ART through food handouts to malnourished PLWH on ART. One of the health workers explained the recruitment criteria for GOAL food beneficiaries:

GOAL is giving out food hand-outs to patients especially those who are on the ARTs programme. We, the health workers, identify under-weight and malnourished patients when they come for monthly check ups at the health centre. These patients benefit from food-hand-outs provided by GOAL. Furthermore, children we discharge from the health centre are referred to the GOAL feeding scheme (Key informant Interview 51, 05/12/2011).

According to interview and FGD participants, ARVs were minimising duration of morbidity and early mortality from HIV and AIDS in Nyamakate. During the data collection exercise the researchers interviewed some households with members who are on ARVs, and they were grateful for the ARV programme. One participant said, “Do you see these three children … their mother is on ARVs. … they would have been orphans if it were not for the tablets” (Interview 9, 14/10/2011).

Another participant said,

I came back [from hospital] and am surviving on ARVs as we speak. I can now work for my children and myself, you cannot even tell that I am sick. I work very hard to get food to stay healthy. I go to sell merchandise in Zambia and around Nyamakate (Interview 8, 14/10/2011).

Interviewed participants observed that PLWH on ARVs, fall sick for a short period of time before they pass, unlike in the past before the ART, when one became bedridden for a long time before passing. One participant is of the opinion that, “The ARV programme is helping in reducing stigma and fears associated with HIV testing” (Interview 12, 23/10/2011).

5. Discussion and conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate the importance of HBC to PLWH despite the successes of ARTs in reducing morbidity and bedridden patients in rural settings. The findings of this study corroborate studies that demonstrate that HIV and AIDS challenges the African family structure through caring for PLWH (Hosegood et al., Citation2007; Tanyi et al., Citation2018). Studies have shown that caregiving demands enormous time and effort, especially at the terminal stage of AIDS (Tanyi et al., Citation2018). This study supports these observations and emphasises the need for care in this era of ART. There is heterogeneity in the study participants’ experiences in caring for people on ART and they explained the hardships and sacrifices that are associated with PLWH in the Nyamakate rural setting. Although most of the studies on caregiving for PLWHW and family structure do not make reference to ART, we agree with scholars that argue that care to people on ARTs in poor settings (like Nyamakate) needs to be understood (Levy et al., Citation2006; Lindayani et al., Citation2018; Treves-Kagan et al., Citation2016). We noted that most households were struggling to meet the required material support and going through multiple episodes of the impacts of HIV and AIDS that include sickness, death and orphans. HIV and AIDS pose challenges for relatively poor families through food insecurity and financial constraints for medicine and transport to take patients to the clinic.

In order to avoid over generalisation of the impacts of HIV and AIDS on family structure, we came up with three typologies of household impacts of the disease. Comparatively, nucleus families’ experiences of PLWH on ARVs was better as compared to extended and grandparents households. Household socio-economic status, available labour, attitudes and locus of decision-making is important in the quality and access to medical care. For example, household 1 decided to sell assets and use family savings for care and specialised medical expenses. Such sacrifices were absent in extended household care since care within this structure was mainly dependent on attitudes of the caregivers. It was reported that patients that supported the host household before they were sick were getting better care than those who did not remit money or material things. It has been observed that in the case of sickness the household re-allocates household labour roles (De Waal et al., Citation2005; Mbereko et al., 2017). This can be explained by the fact that a caregiving role causes income loss, not only because the ill person is no longer productive but also that the caregiver sacrifices productive work to take up the caregiving role.

Literature has documented that HIV and AIDS have added another dimension to the role of the elderly in society by making them caregivers to their children and orphans (Hosegood et al., Citation2007; Kagee et al., Citation2011). Traditionally, the African family has a hierarchy of relationships and there are roles ascribed to each generation level. According to Ntozi and Zirimenya (1999), the function of grandparents is to help in the upbringing of the children and guiding the household head (father). Southern Africa studies show shifts in the function of grandparents in the era of HIV and AIDS as they increasingly have to take up a caregiving role while using their resources from pensions, assets and social networks (Hosegood et al., Citation2007; Kagee et al., Citation2011). In this study, even with the ART, the grandparents assume the roles of fending for the orphans and caregiving activities. The grandparents’ households were multi-generational, characterised by predominantly aged and young people. This is important because the household structure has an influence on caregiving and household financial status. The findings show that PLWH get government supplied ARVs for free but they cannot afford food and other needs. Although further assistance is offered by NGOs, it was reported that this assistance was not only sporadic but also benefited very few people.

In conclusion, the HBC continues to be stressed by the challenges associated with caring for PLWH even though they are on ART. All three household structures in the Nyamakate community are struggling to cope with the care needs of PLWH in the home setting, since the disease results in income and asset loss, food insecurity, labour shortage and shifts in household roles. The link between household structure, socio-economic status and attitude of caregivers determine the quality of care for PLWH in home settings. The lack of adequate institutional social welfare support means that the Nyamakate households have limited support besides the ARVs. The study was qualitative; hence, it limits generalisation of the findings, but the paper makes an important contribution to understanding HBC in the era of ART in rural Zimbabwe. There is limited research on this topic in contemporary Zimbabwe. The household structure, care giver’s attitude and socio-economic status can contribute positively to drug adherence and retention rates. We recommend that the ART programme in rural Zimbabwe looks beyond the clinic and hospital realities of the programme by considering poverty that compromises health outcomes of patients taking ARVs.

Ethical issues

The study was given full approval by the Humanities and Social Sciences research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal and the clearance number is HSS/0349/011D. Clearance was sought from the Nyamakate gatekeepers that ranged from village through the District and Provincial Administrators’ offices.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding from HEARD. We appreciate the support and contributions of the following institutions to this work: Department of Environmental Science (formerly Department of Natural Resources), Chinhoyi University of Technology; School of Built Environment and Development Studies (formerly School of Development Studies), University of KwaZulu-Natal; and the Hurungwe Rural District Council. We are thankful to S. Chosa and M. T. Mbereko for their assistants with data collection.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mbereko Alexio

Mbereko Alexio is a senior lecturer/researcher at the Women’s University in Africa where he is currently lecturing in child rights and protection, conflict, peace and transformation and advanced research methods. He is interested in research on social-ecological systems, public health issues and climate change.

Scott Dianne

Scott Dianne specializes in urban geography with interest in the field of environmental and climate change governance, environmental politics and sustainable urban development. She is also a co-editor of a book on the co-production of development and climate change knowledge for the city of Cape Town. She is a research professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Venganai Hellen

Venganai Hellen is in the field of gender. In 2016, she was involved in research spearheaded by the Economics department at Stellenbosch University on traditional and contemporary roles of African women in politics in Sub-Saharan Africa. She is a senior lecturer at the Women’s University in Africa where she lecturer in gender studies.

References

- Banks, L. M., Zuurmond, M., Ferrand, R., & Kuper, H. (2017). Knowledge of HIV-related disabilities and challenges in accessing care: Qualitative research from Zimbabwe. PloS one, 12(8), e0181144. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181144

- Campbell, C., Scott, K., Nhamo, M., Nyamukapa, C., Madanhire, C., Skovdal, M., & Gregson, S. (2013). Social capital and HIV competent communities: The role of community groups in managing HIV/AIDS in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care, 25(sup1), S114–S122. doi:10.1080/09540121.2012.748170

- Chimhowu, A., & Hulme, D. (2006). Livelihood dynamics in planned and spontaneous resettlement in zimbabwe: Converging and vulnerable. World Development, 34(4), 728–750. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.08.011

- De Waal, A., Tumushabe, J., & Mandani, M., & Kilama. B (2005). HIV and AIDS and changing vulnerability to crisis in Tanzania: Implications for food security and poverty reduction. Presented at HIV and AIDS and food and nutrtional security meeting, 14–16 April, Durban, South Africa.

- Evans, R. M. (2005). Social networks, migration, and care in Tanzania: Caregivers’ and children’s resilience to coping with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Children and Poverty, 11(2), 111–129. doi:10.1080/10796120500195527

- FAO. (1996). Declaration on world food security. Rome: Author.

- Ferrand, R. A., Simms, V., Dauya, E., Bandason, T., Mchugh, G., Mujuru, H., … Weiss, H. A. (2017). The effect of community-based support for caregivers on the risk of virological failure in children and adolescents with HIV in Harare, Zimbabwe (ZENITH): An open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 1(3), 175–183. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30051-2

- Hosegood, V., Preston-Whyte, E., Busza, J., Moitse, S., & Timaeus, I. M. (2007). Revealing the full extent of households’ experiences of HIV and AIDS in rural South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 65(6), 1249–1259. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.002

- Kagee, A., Remien, R. H., Berkman, A., Hoffman, S., Campos, L., & Swartz, L. (2011). Structural barriers to ART adherence in Southern Africa: Challenges and potential ways forward. Global Public Health, 6(1), 83–97. doi:10.1080/17441691003796387

- Kitchin, R., & Tate, N. J. (2000). Conducting research in human geography: Theory methodology and practice. London: Pentice hall.

- Levy, A. R., James, D., Johnston, K. M., Hogg, R. S., Harrigan, P. R., Harrigan, B. P., & Montaner, J. S. (2006). The direct costs of HIV/AIDS care. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 6(3), 171–177. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70413-3

- Lindayani, L., Chen, Y. C., Wang, J. D., & Ko, N. Y. (2018). Complex problems, care demands, and quality of life among people living with HIV in the antiretroviral era in Indonesia. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 29(2), 300–309. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2017.10.002

- Maposa, I. (2016). Survival modelling and analysis of HIV/AIDS patients on HIV care and antiretroviral treatment to determine longevity prognostic factors. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.ru/scholar?hl=ru≈sdt=0%2C5&q=Maposa%2C+I.+%282016%29.+Survival+modelling+and+analysis+of+HIV%2FAIDS+patients+on+HIV+care+and+antiretroviral+treatment+to+determine+longevity+prognostic+factors.&btnG=

- Mbereko, A., Scott, D., & John Chimbari, M. (2016). The relationship between HIV and AIDS and water scarcity in Nyamakate resettlements land, north-central Zimbabwe. African Journal of AIDS Research, 15(4), 349–357. doi:10.2989/16085906.2016.1247735

- Mbereko, A., Scott, D., & Kupika, L. O. (2015). First generation land reform in Zimbabwe: Historical and institutional dynamics informing household’s vulnerability in the Nyamakate resettlement community. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 7(3), 21–40.

- Mutasa-Apollo, T., Shiraishi, R. W., Takarinda, K. C., Dzangare, J., Mugurungi, O., Murungu, J., … Woodfill, C. J. (2014). Patient retention, clinical outcomes and attrition-associated factors of HIV-infected patients enrolled in Zimbabwe’s national antiretroviral therapy programme, 2007–2010. PloS one, 9(1), e86305. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086305

- Ntozi, J., & Zirimenya, S. (1999). Changes in household composition and family structure during the aids epidemic in Uganda. In I. Oruboloye, J. Caldwell, & J. Ntozi (Eds.), The continuing hiv/aids epidemic in africa: responses and coping strategies pp. 193–209. Canberra: Health Transition Centre, Australian National University.

- Schatz, E., Madhavan, S., & Williams, J. (2011). Female-headed households contending with aids-related hardship in rural south africa. Health & Place, 17(2), 598–605. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.017

- Tanyi, P. L., Pelser, A., & Okeibunor, J. (2018). HIV/AIDS and older adults in Cameroon: Emerging issues and implications for caregiving and policy-making. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 15(1), 7–19. doi:10.1080/17290376.2018.1433059

- Treves-Kagan, S., Steward, W. T., Ntswane, L., Haller, R., Gilvydis, J. M., Gulati, H., … Lippman, S. A. (2016). Why increasing availability of ART is not enough: A rapid, community-based study on how HIV-related stigma impacts engagement to care in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health, 16(87), 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2639-8

- Williams, B. G., Gouws, E., Somse, P., Mmelesi, M., Lwamba, C., Chikoko, T., … Damisoni, H. (2015). Epidemiological trends for HIV in southern Africa: Implications for reaching the elimination targets. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 12(2), 196–206. doi:10.1007/s11904-015-0264-x

- Wringe, A., Cataldo, F., Stevenson, N., & Fakoya, A. (2010). Delivering comprehensive home-based care programmes for hiv: A review of lessons learned and challenges ahead in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Health Policy and Planning, 25(5), 352–362. doi:10.1093/heapol/czq005