Abstract

This study calls into question whether international aid agencies have involved relevant stakeholders in the tourism development planning process of the Petra region. The paper determines the advantages of the stakeholders’ participation in the tourism planning and development process by reviewing related literature; then, an intensive desk research has been performed to the localization of the study, to establish a platform to answer the study’s question. The study relies on a qualitative data analysis, by conducting a deductive direct content analysis of the planning documents of the Petra region throughout the period of 1968–2014. Inviting the international organization to address development plans did not help the region’s stakeholders to reap the rewards, because the stakeholders did not participate effectively in the planning process. Moreover, the study revealed several barriers to stakeholders’ participation in the region. This study contributes to the advantages of the stakeholders’ integration in the tourism development planning process also it sheds the light on different barriers to tourism planning.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper is a part of the greater effort of investigating the impact of tourism on the local community of the Petra region, Jordan. The purpose of this study, to our research, is to revise the tourism development in the region and to shade the light of the importance of integrating the stakeholders in the planning process. In the case of the Petra region, international agencies were invited to formulate development plans, it was found that the plans did not effectively involve the relative stakeholders. However, there are barriers stood between the integration and the involvement, such as the lack of local expertise and financial funding.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, different approaches have been adopted in tourism planning. Forms of planning that are based on the community-based development have been particularly popular (Dutra, Haworth, & Taboada, Citation2011). Tourism planning today is increasingly expected to involve both the local community and visitors (Cooper, Citation1995). Stakeholder engagement is increasingly becoming a central part of the planning process in tourist destinations (Ruhanen, Citation2009). Hall Citation2008 and Ritchie and Crouch Citation2003 emphasize the importance of the involvement of the stakeholders in the planning process. However, stakeholders’ participation in the planning process represents the most important factor of successful tourism planning (Byrd, Cárdenas, & Greenwood, Citation2008; Simpson, Citation2001).

In developing countries such as Jordan, in one hand, weaknesses exist in the planning framework, on the other hand, tourism represents an industry that is intended to attain economic benefits and facilitate regional development, especially in areas that suffer from a lack of resources and that have weak agricultural and industrial sectors (Harrill, Citation2004). Therefore, the lack of tourism planning experts and the financial resources drive the developing countries’ governments to ask the international agencies to develop tourism plans (Tosun & Jenkins, Citation1998). The methods used in the planning process are mainly influenced by the funder, which are the international agencies. However, While several authors have addressed the implying of stakeholders in the planning process in their studies (Buhalis, Citation2000; Byrd, Citation2007; Crawford, Kotval, Rauhe, & Kotval, Citation2008; Edgell, Allen, Smith, & Swanson, Citation2008; Evans, Campbell, & Stonehouse, Citation2003; Freeman, Citation2010; Hall, Citation2008; Jamal & Getz, Citation1995; Meyers, Budruk, & Andereck, Citation2010; Ritchie & Crouch, Citation2003), there is lack of studying the role of the international consulting agencies in tourism development (Tosun & Jenkins, Citation1998).

However, effective governmental planning and management may stimulate greater development in the nation as a whole. If development is poorly planned and managed, tourism might have a number of negative effects (Harrill, Citation2004; Hejazeen, Citation2007). In general, the government has several orientations to tourism development, such as seeking more positive economic impacts (Pekka Kauppila, Jarkko Saarinen & Riikka Leinonen, Citation2009). Sustainability has been recently appearing in the regional tourism planning (Hall, Citation2007; Cobbinah, Black, Thwaites, Citation2013). Hall (Citation2000) added sustainable tourism planning dimension to what Getz (Citation1987) divided the tourism planning traditions (cited in Treuren & Lane, 2003, p. 13). The last divided them into boosterism, development, physical and community-based approaches. Sustainability approach to tourism planning is defined by two key principles: strategic orientation and stakeholders’ participation (Ruhanen, Citation2009; Simpson, Citation2001).

Previous studies have identified certain barriers to the involvement of local stakeholders in the planning process. A lack of shared vision and long-term strategy have represented the most important factors that inhibit integration approaches (Hatipoglu, Alvarez, & Ertuna, Citation2016; Ladkin & Martinez Bertramini, Citation2002).

The present study adopts the community approach in tourism planning at the regional level, in order to evaluate the involvement of stakeholders in the international agencies’ tourism planning process in the Petra region, Jordan. Moreover, this study aims to contribute towards the quality enhancement of the Petra region tourism and community development plans by accomplishing the following objectives: (i) to determine whether the international aid agencies have integrated the local community in the planning of tourism and community development, and (ii) to identify the barriers of tourism planning and stakeholder participation in the Petra region. To do so, the available planning documents of the international agencies have been analysed using the content analysis method.

The following section will address the literature review of the tourism planning and international aid in the developing countries. Thereafter, the study area’s management history will be explained, to what can provide insight into the several barriers to tourism development in the region. Then, section four will address the analysis process. Afterwards, discussion and conclusion will be provided along with implications and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature review

Carefully planned tourism policies can increase the benefits and decrease the negative impacts of tourism. This has been realised within both the private and public sectors following growing awareness of the detrimental consequences of badly planned tourism policies (Parsa, Citation2015; Ragas & Roberts, Citation2009). In order to be successful and beneficial, tourism planning should include the whole community. This can be achieved through responsible management and planning (Butler, Hall, & Jenkins, Citation1999; Inskeep, Citation1991; Southgate & Sharpley, Citation2002). Accordingly, communities that use or plan to use tourism as a tool for economic development and diversity must develop policies with sustainability principles at their core (Pucako & Ratz, Citation2000; Puppim de Oliveira, Citation2003; Southgate & Sharpley, Citation2002; Yuksel, Bramwell, & Yuksel, Citation1999).

The participation of the community in the planning process may be considered a form of institution theory, which examines the importance of addressing host community interests in public policy decision-making processes (Thyne & Lawson, Citation2001). Murphy (Citation1985) argues that by involving local communities in community planning decision-making, potential disputes between local people and the central authorities can be avoided, as has been observed in South America (Kent, Citation2006). However, the main barrier to collaborative planning is the absence of a shared vision or the failure to enable all stakeholders to participate (Ladkin & Bertramini Citation2002). Moreover, Hall (Citation2008) has described a new approach that focuses on efficiency, investment return and increased stakeholder participation. Interested groups, stakeholders and government should work together to ensure that the benefits of tourism are enjoyed by locals, increasing the community’s quality of life.

However, the absence of stakeholder participation has been highlighted as the principal challenge to collaborative planning approaches in numerous studies (Sautter & Leisen, Citation1999). For instance, Blackstock (Citation2005, p. 2) has criticised the absence of a shared vision in community-based tourism approaches: “the local community is a homogeneous body capable of making decisions through consensus”. The relational approach confirms the importance of stakeholder participation in tourism planning (Hall, Citation2008). The stakeholder approach highlights the “plurality of organizational interest groups and the political nature of organizational goal setting and policy implementation” (Treuren & Lane, Citation2003, p. 4).

Regarding the location of this study, the Petra region has received little interest from tourism researchers. However, two notable exceptions exist, which examine stakeholders’ engagement in the region’s tourism development. First, Hejazeen (Citation2007) concluded that stakeholders were not formally invited to participate in any strategic plans, and that they did not believe that the strategies developed addressed their issues. This study covered the most important tourism attractions in Jordan, Petra being one of them. In contrast, Alhasanat and Hyasat (Citation2011) claimed that local community representatives were involved at a moderate level in decision-making at Petra.

3. Localization and context of the Petra region

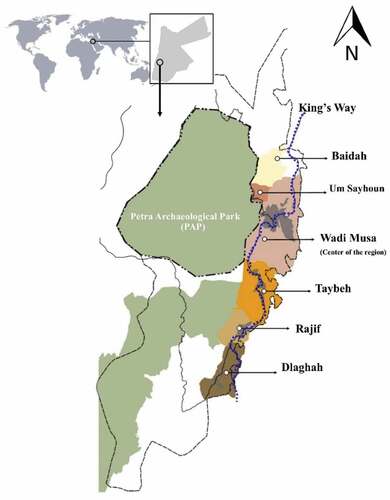

Petra is located 248 km from Amman, the capital of Jordan, via the famous Kings’ Highway, and attracts visitors from Jordan and around the world. Petra Archaeological Park (PAP) is centrally located in the Petra region and covers 264 km2 out of 800 km2 of its area (Figure ).

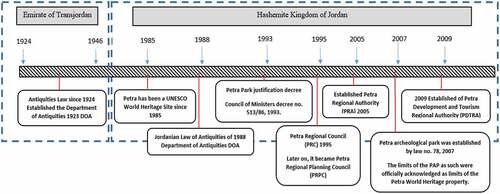

The present borders of the Petra region were set following the establishment of the Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority (PDTRA) in 2009. The PDTRA shares similar roles with other authorities, but it also enjoys financial and administrative independence, reports directly to the Prime Minister, and has its own legislative set-up. The mandate of the PDTRA is to support the protection of the PAP, such as by overseeing tourism management and development, zoning and land use, and the improvement of the socio-economic conditions of local communities. The current system of management is a result of numerous organisational changes since 1924 (Figure ).

Tourism development in many developing countries, including Jordan, began under three decades ago (Telfer & Sharpley, Citation2008). In Jordan’s case, the government started to ask for aid from international organisations in order to develop the industry (Hejazeen, Citation2007). The ancient city of Petra represents the country’s primary tourist destination and is today considered one of the most significant tourist destinations in the world. Organisations from the United States of America (USA) have funded numerous projects aimed at developing tourism in the region, starting in 1968 with the United States National Park Service (US/NPS) and subsequently the United States Aid Agency (USAID). In 2016, the Jordanian government pledged to support the PDTRA following a decline in visitor numbers over a 7-years period (Figure ), an issue of particular concern given that the PDTRA’s main income is dependent on entrance fees.

3.1. Stakeholders of the Petra region

Defining stakeholder groups considered as problematic (Richards & Hall, Citation2000). Stakeholder groups can be classified based on different qualities (e.g. economic and social). however, According to the definition of (Buhalis, Citation2000; Yoon, Citation2002; Carroll & Buchholtz, Citation2009, p. 27; Freeman, Citation2010; Morrison, Citation2013) and more importantly, Simpson (Citation2001) emphasized that the following categorisation is appropriate to identify involved affected parties, especially when it comes to the tourism planning:

Governmental: national, regional and local government, national and regional tourism organisations, government departments with links to tourism.

Visitation: existing visitor groups.

Community: tourism industry operators, non-tourism business practitioners, local community groups, indigenous people’s groups and local residents (Ordinary residents).

4. Methodology

A heavy desk research by authors was carried out related to the Petra region and its tourism planning, by gathering data from different sources; including reports from PDTRA and MOTA, newspapers, books and five years observations of one of the authors, in order to examine the involvement of the local community in the planning process.

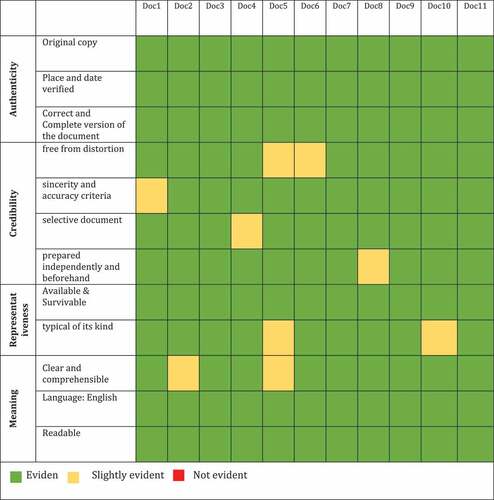

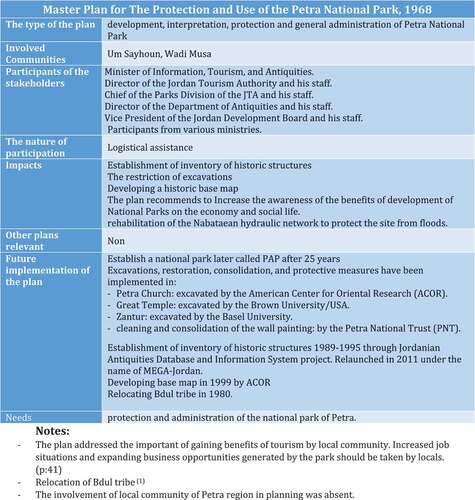

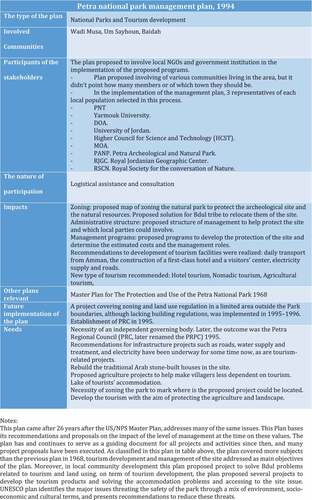

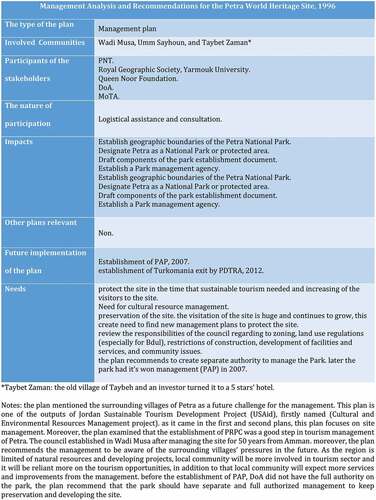

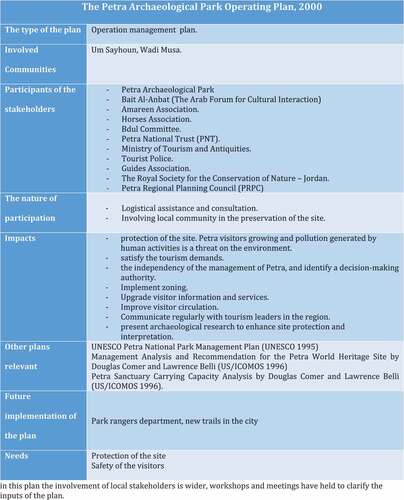

In order to accomplish the research’s objectives, content analysis and documentary research method were performed to analyse the planning documents of the international agencies, which aimed to develop the tourism sector in the Petra region (Table ), these documents are the unit of analysis. According to O’Leary (Citation2014), the type of these documents is Public Records, more precisely, the types of documents were as follows: mediate access, primary source, written text and private documents (Scott, Citation2014). And the number of analysed documents is valid (Bowen, Citation2009; O’Leary, Citation2014) where the quality of the document is elevated. Data were collected by undertaking a latent analysis of planning documents. The plans were issued during the period of 1968–2014, one document was issued 30 years ago, this can be justified by the few numbers of tourism plans of the region, and the linked of the document to other plans and to the study’s objectives.

Table 1. Tourism development plans of the Petra region 1968–2014 (Units of analysis)

The analysis focused on the planning documents that formulated whether to develop the archaeological park or the towns of the region, by international organisations. The archives of planning documents were obtained from the websites and offices (archive) of PDTRA and Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities of Jordan (MOTA) (Appendix A).

It should be noted that some plans are aimed at developing the tourism sector in the country, but during desk research authors decided to include them because they contain information of tourism planning in the Petra region (such as Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Citation1996, Citation1994, Citation1999/United States Aid Agency (USAID) Citation2006, Citation2014).

4.1. Analysis process

In this study, the analysis method is content analysis; however, according to the unit of analysis, authors decided to include the criteria of selecting and handling the documents, which is a process related to the documentary research method illustrated by Scott (Citation2014).

Each published document was reviewed carefully for two reasons, first, to ensure that each document was formulated by a foreign organization and related to our study. Second, according to Scott (Citation2014), the quality of the documents must be considered when it comes to the content analysis. The criteria suggested by Scott (Citation2014) were performed to evaluate the documents to assess the value and validity of this study. These criteria are: authenticity, credibility, representativeness, and meaning (Appendix B). Therefore, content analysis was performed. Content analysis as a research method is used in this study because of its flexibility for analysing text data, and its usefulness to examining trends and patterns in documents (Mcculloch, Citation2004). Moreover, the method has been applied in multiple areas and is considered as a research technique in describing and identifying what is written on a specific subject in texts (Weber, Citation1990). Figure shows the process of the content analysis that adopted from Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008).

Figure 4. Analysis process, adopted from Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008).

The analysis adopted a deductive approach, directed content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) emphasizing previous knowledge of the phenomena and explaining the data to produce a better explanation. The aim of using this method is to go deeper into the documents to generate better understanding about the involvement of stakeholders in the planning process, and using latent content analysis used to find the underlying meaning of the text (Berg, Citation2001; Burns & Grove, Citation2005; Morse & Field, Citation1995).

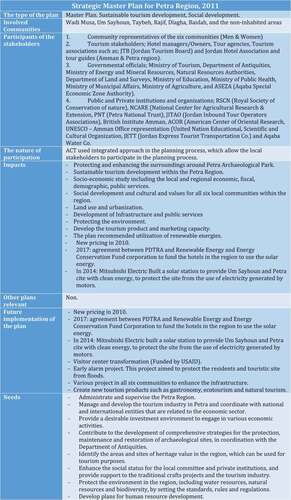

The categories were chosen according to the aim of the study, to provide a means of describing the stakeholders’ participation in the planning process (Cavanagh, Citation1997); moreover, categories were guided by the data provided in the plans during the desk research. Categories selected as follows: The type of the plan, involved communities, Participants of the stakeholders, the nature of participation, Impacts of the plan, Other relevant plans and recommendation and the needs of the plan and Future implementation. Categorization matrix and results of the analysis of some plans are available in Appendix C.

5. Results and discussion

Generally, the results reveal that the stakeholder integration approach has not been effectively incorporated within the planning process, especially ordinary residents. Moreover, the governmental parties did not tend to be involved. The results suggest that the purpose of governmental participation is logistical (i.e. organising the movement, equipment and accommodation of the planning teams). The recommendations of the plans were not seen to apply in the region, at least not immediately. However, geographically, plans from 1968 until 2008, as well as the 2014 plan, covered the touristic area and ancient city of Petra, located west of Wadi Musa and south of Um Sayhoun. Unfortunately, other towns were absent from regional planning processes, aside from in the ATC plan. Stakeholders have not been effectively integrated into the planning process in the Petra region. This is reflected in the fact that until 1994, planning documents focused on the preservation and protection of the archaeological site, without attending to the importance of spreading the benefits of tourism and economic diversification to all communities in the region. Stakeholder participation was notably absent from most of the planning documents.

Petra literature revealed that the results of this study are in the line with the results of Hejazeen (Citation2007), who found that the local community of the Petra region has been excluded from the planning and management process of development projects. Moreover, Alhasanat and Hyasat (Citation2011) also found that individuals in this local community disagree that they have been involved in the planning process. Our findings also correspond with those of Tarawneh and Wray (Citation2017), who note that the local community discussed the requirement to involve key stakeholders in Petra’s development planning process.

5.1. Management and implementations dimension

Between the years of 1934 and 1995, the management of Petra was in Amman, under the MOTA (see Figure ). Such geographical distance between the centre of decision-making and the location in question reduces the efficiency of the work. The changing of management during the period 1968–2007 has influenced the common strategies (Figure ). The negative impact of organisational change has been identified in several studies (DiFonzo, Bordia, & Rosnow, Citation1994; Smeltzer & Zener, Citation1992). Organisational change can have a negative impact on both the performance and shared vision of the organisation. Authors emphasise that lack of involvement of stakeholders may have been affected by instability in the management, reducing the local community’s trust in the management’s decisions. However, residents are now looking forward to participating in the planning process in the development of their region (Alshawagfih, Albrari, & Alananzeh, Citation2015).

From 1968 until 2004, the Petra region was administered under various management and public policies, and the tourism leaders attempted to develop the region throughout the period (Figure ). Consequently, planners from international organisations have encountered difficulties in meeting the plans’ objectives, especially US/NPS (Citation1968, Citation2000) and US/ICOMOS (Citation1996).

The results revealed a lack of strategic planning in the US/NPS, UNESCO and USAID plans. Tourism development was reflected in the establishment of a national park—named the Petra Archaeological Park (PAP) 25 years after the US/PNS (Citation1968) plan—as well as the resettlement of the Bdul tribeFootnote1 from 1985 through 1987.

However, the implementation of the ATC plan was more effective, the management applied the proposals of the ATC plan just one year later. The PDTRA created new tourism products such as gastronomy and ecotourism, in order to increase the positive impact of tourism on the local economy. Subsequently, residents created a tourism local association to take advantage of investment opportunities and to distribute them throughout the society (e.g. Dlagha Tourism Association, Alrajif Tourism Association). Bearing in mind that the community possessed no experience or knowledge to take advantage of the investment opportunities, it is interesting to note that the USAID plan has enhanced women’s involvement in the tourism industry; moreover, following their recommendations, the management launched the Care for Petra campaign.Footnote2

5.2. The involvement of stakeholder

The results show that ordinary residents were totally absent in the United States National Park Service (USNPS) (Citation1968, Citation2000) report, whereas UNESCO (Citation1994) involved three residents from each community. The environmental assessment was the only area in which USAID (Citation2008) involved the local community. Moreover, the involvement of the local tourism association was evident in all plans except the United States National Park Service (USNPS) (Citation1968). With this in mind, the analysis revealed that the nature of participation of the local associations and governmental departments was to provide logistical assistance and to highlight the needs of the region, rather than to identify what was desired by and acceptable for the local community. However, nowadays, the local community is creating their own non-governmental organisations to be involved in the tourism industry and to increase their power in the region (Farajat, Citation2012).

Unlike previous-mentioned plans, the ATC plan was quite distinctive from the others. Its planners involved stakeholders in a wide range of ways; ordinary residents participated in the planning process, meetings and questionnaires were conducted with stakeholders in order to determine the needs of the local community, and the ATC proposed development projects that were deemed congruent with local visions and values. Moreover, the ATC plan was the only one that covered the whole region and that proposed projects to develop all six villages. Consequent the integration approach of the ATC’s plan, it has achieved remarkable results, and its recommendations are implemented by tourism leaders. The success of this plan encapsulates the value of using the integration approach in tourism planning. Fennell (Citation2014) has emphasised the importance of including all local community parties in the planning process. Effective strategic planning is a social phenomenon, involving stakeholders of different types and at different times (Bryson, Citation2017).

5.3. Barriers of stakeholder’s integration

Previous studies have identified the barriers that can limit stakeholder participation in an integrated or community-based tourism planning process. These may include a lack of clear leadership or shared vision (Blackstock, Citation2005; Ladkin & Martinez Bertramini, Citation2002; Sautter & Leisen, Citation1999). Moreover, Moscardo (Citation2011) has argued that local communities may lose influence over tourism development where they lack knowledge of the planning and development process.

Other barriers might include development weaknesses in the region, such as administrative impediments that have inhibited the achievement of successful development outcomes (Tosun, Citation2000), and cultural impediments pertaining to the local community’s limited awareness or understanding of tourism. Literature has identified similar barriers to local community participation (Damhoureyeh, Disi, Al-Khader, & Abu-Dieye, Citation2011; Tarawneh & Wray, Citation2017), and have attributed a lack of participation to limited human and economic resources. In addition to a lack of institutional and human capacity, Tarawneh and Wray (Citation2017) have recognised the influence of political conflicts on sustainable development in the Petra region. This also represents a common barrier to participatory planning approaches in other tourism destinations (Bornhorst, Ritchie, & Sheehan, Citation2010).

Literature has identified knowledge and experience as central to stakeholder power in tourism development (Byrd et al., Citation2008; Moscardo, Citation2011; Tosun, Citation2000). The results illustrate a lack of knowledge and awareness amongst stakeholders, which is in the line with findings of a previous study in Turkey and developing countries (Hatipoglu et al., Citation2016; Tosun, Citation2000).

In this study, the majority of stakeholder participation was limited to governmental parties such as MOTA, whose participation was predominantly logistical. Such findings reinforce our argument about barriers and reflect the relative importance of government power in the planning process in the Petra region. However, after a year of overseeing the region’s tourism planning, the management realised that a long-term plan was required to enhance tourism and community development in the region. The ATC consultation plan represented the first step towards managing Petra’s tourism development.

Recently, the management has provided investment facilities to those wishing to invest in the region and prepares a feasibility study for each project. Five major projects aimed at developing the region and funded by the Jordanian government are being overseen (PDTRA, Citation2019).

Indeed, in their vision to develop the tourism product, the management has recently started to move away from a product-led approach focused upon exhibits and education, and towards a more tourist-oriented approach that focuses on consumer preferences and the quality of personal experiences (Alazaizeh Citation2014; Apostolakis & Jaffry, Citation2005). Challenges in facilitating stakeholder participation in the planning process are connected with a lack of planning experience or sustainable vision amongst development leaders in the Petra region, as well as a shortage of funding from the Jordanian government.

The planners involved some of the region’s organisations, we specifically sought to identify the reasons for the lack of integration of stakeholders and whether this would affect the implementation of the plan. It is also important to acknowledge that Petra has a local leadership that includes tribes, whose power, number and public status can vary considerably. This creates obstacles to management in terms of the development of the region. Regarding this aspect, authors recommend a special integration approach in order to create a balance between tourism development, citizen satisfaction and the preservation of the ancient city of Petra and other its tourist attractions. This can be achieved by offering young citizens in the region the ability to become part of its development planning. Moreover, give the region its own decision when it comes to the commissioner’s election.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we investigated the stakeholders’ participation in the tourism planning of international organization in the Petra region. We used the available documents of those plans and analysed their content. The findings of this study have some important implications for the authorities responsible for the management of the Petra region. The results indicate the importance of using the integration approach and involving stakeholders in the planning process has had positive effects in the Petra region. The support of local residents is essential when it comes to the tourism planning (Gursoy, Chi, & Dyer, Citation2010). Thus, the community-based approach is required for the region. And that requires an alteration in the balance of power among the stakeholders (Bahaire & Elliott-White, Citation1999). This balance can be accomplished by training local tourism planners, the Petra region will, therefore, remain dependent on international organization. Moreover, in order to facilitate tourism planning in the Petra region, all levels of the stakeholders need to be empowered, integrated and engaged in the planning process, and relatedly, sustainable tourism issues need to be taken more seriously.

Finally, this study serves tourism leaders in Petra and Jordan to prepare effective tourism plans and strategies. Moreover, it helps to evaluate the international aid to tourism planning. It provides a better understanding of the barriers that stands between the tourism development and implementation of the recommendations of the plans. The selected documents can be used as units of research the sustainable tourism development in the Petra region.

Correction

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1627637).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Moayad Mohammad Alrwajfah

Moayad Mohammad Alrwajfah is a tourism researcher and doctoral candidate at the University of Malaga (Spain). He holds a master degree in business administration (MBA) from Mutah University (Jordan). His research interests concentrate on community-based tourism management. His works focus on the societies and their culture as the key of future tourism, by investigating sustainable tourism development, community-based tourism and tourism impacts. He approached these concepts from his field of work in Petra, Jordan.

Notes

1. A Jordanian Bedouin tribe that lived in Petra site until 1987. The tribe follows a semi-nomadic way of life, living in Petra’ caves during the winter and relocating with their tents in the summer. With the mass influx of tourists to Petra, the Bdul moved to a nearby village named Um Sayhoun. Today, 3,000 people live there. Most of them work in the tourist industry around Petra as guides, souvenir-sellers and escorts of animals, including donkeys, camels, horses and mules, which are used for transportation at the Petra site.

2. This aimed to protect the site, provide welfare for animals, and prevent child labour at the tourist site.

References

- Alazaizeh, M. 2014, “Sustainable Heritage tourism: A tourist-oriented approach for managing Petra archaeological park, Jordan”, PhD thesis, Paper 1430. Available at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1430

- Alhasanat, S. A., & Hyasat, A. S. (2011). Sociocultural impacts of tourism on the local community in Petra, Jordan. Jordan Journal of Social Science, 4(1), 144–21. https://journals.ju.edu.jo/JJSS/article/view/2255

- Alshawagfih, K. F., Albrari, D. D., & Alananzeh, O. A. (2015). Tourist development in Petra Province: Wadi musa as a case study. European Journal of Social Sciences, 49(4), 438–451. http://www.europeanjournalofsocialsciences.com/issues/EJSS_49_4.html

- Apostolakis, A., & Jaffry, S. (2005). A choice modeling application for Greek heritage attractions. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 309–318. doi:10.1177/0047287504272035

- ATC Consultants (ATC). (2011). The strategic master plan for the Petra region, prepared for the Petra development and tourism authority. Retrived from https://www.planetizen.com/files/plans/Strategic%20Master%20Plan%20for%20Petra%20Region.pdf

- Bahaire, T., & Elliott-White, M. (1999). Community participation in tourism planning and development in the historic city of York, England. Current Issues in Tourism, 2(2–3), 243–276. doi:10.1080/13683509908667854

- Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Blackstock, K. (2005). A critical look at community based tourism. Community Development Journal, 40(1), 39–49. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsi005

- Bornhorst, T., Ritchie, J. B., & Sheehan, L. (2010). Determinants of tourism success for DMOs and destinations: An empirical examination of stakeholders’ perspectives. Tourism Management, 31(5), 572–589. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2009.06.008

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method.

- Bryson, J. M. (2017). Strategic planning for public and nonprofit organizations: A guide to strengthening and sustaining organizational achievement (5th ed.). Newark: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management, 21(1), 97–116. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00095-3

- Burns, N., & Grove, S. (2005). The practice of nursing research: Conduct, critique, and utilization. Michigan: Elsevier/Saunders.

- Butler, R., Hall, C., & Jenkins, J. (1999). Tourism and recreation in rural areas. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Byrd, E. (2007). Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: Applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Review, 6(22), 6–13. doi:10.1108/16605370780000309

- Byrd, E. T., Cárdenas, D. A., & Greenwood, J. B. (2008). Factors of stakeholder understanding of tourism: The case of Eastern North Carolina. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(3), 192–204. doi:10.1057/thr.2008.21

- Carroll, A., & Buchholtz, A. (2009). Business and society: Ethics and stakeholder management. Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

- Cavanagh, S. (1997). Content analysis: Concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Researcher, 4(3), 5–16. doi:10.7748/nr.4.3.5.s2

- Cobbinah, P., Black, R., & Thwaites, R. (2013). Tourism planning in developing countries: Review of concepts and sustainability issues. International Journal of Environmental Ecological, Geological and Mining Engineering, 7(4), 211-218.

- Cooper, C. (1995). Strategic planning for sustainable tourism: The case of the offshore islands of the UK. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 3(4), 191–209. doi:10.1080/09669589509510726

- Crawford, P., Kotval, Z., Rauhe, W., & Kotval, Z. (2008). Social capital development in participatory community planning and design. Town Planning Review, 79(5), 533–553. doi:10.3828/tpr.79.5.5

- Damhoureyeh, S., Disi, S., Al-Khader, I., & Abu-Dieye, M. H. (2011). Development of a zoning management plan for Petra Archaeological Park (PAP), Jordan. Natural Science, 3(12), 1040–1049. doi:10.4236/ns.2011.312130

- DiFonzo, N., Bordia, P., & Rosnow, R. L. (1994). Reining in rumors. Organizational Dynamics, 23(1), 47–62. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(94)90087-6

- Dutra, L. X. C., Haworth, R., & Taboada, M. B. (2011). An integrated approach to tourism planning in a developing nation: A case study from Beloi (Timor-Leste). In D. Dredge & J. Jenkins (Eds.), Stories of practice: tourism policy and planning (pp. 269–293). Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- Edgell, D. L., Allen, M. D. M., Smith, G., & Swanson, J. (2008). Tourism policy and planning: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Amsterdam: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Evans, N., Campbell, D., & Stonehouse, G. (2003). Strategic management for travel and tourism. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Farajat, S. (2012). The participation of local communities in the tourism industry at Petra. In D. C. Comer (Ed.), Tourism and archaeological heritage management at Petra (pp. 145–165). New York, NY: Springer Briefs in Archaeological Heritage Management.

- Fennell, D. (2014). Ecotourism: An Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Freeman, R. E. (2010). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Getz, D. (1987) Tourism planning and research: Traditions, models and futures. Paper presented at the Australian Travel Research Workshop, Bunbury, Western Australia, 5–6 November.

- Gursoy, D., Chi, C. G., & Dyer, P. (2010). Locals’ attitudes toward mass and alternative tourism: The case of sunshine coast, Australia. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 381–394. doi:10.1177/0047287509346853

- Hall, C. M. (2007). Introduction to tourism in Australia. Frenchs Forest, N.S.W: Pearson Education Australia.

- Hall, C. M. (2008). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships (2 ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

- Harrill, R. (2004). Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: A literature review with implications for tourism planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 18, 251–266. doi:10.1177/0885412203260306

- Hatipoglu, B., Alvarez, M. D., & Ertuna, B. (2016). Barriers to stakeholder involvement in the planning of sustainable tourism: The case of the Thrace region in Turkey. Journal of Cleaner Production, 111, 306–3017. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.11.059

- Hejazeen, E. G. (2007). Tourism and local communities in Jordan: Perception, attitudes and impacts. München: Profil Verlag.

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Inskeep, E. (1991). Tourism planning: An integrated and sustainable development approach. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Jamal, T., & Getz, D. (1995). Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). (1994). Jordan country tourism development plan survey. Retrieved from https://libportal.jica.go.jp/library/HICSBooks/DetailsSearch.php

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). (1996). Tourism development plan in the Hashemite Kingdome Of Jordan. Nippon Koei Co., Ltd., Padeco Co., Ltd., Regional Planning International Co., Ltd. Retrieved from https://libportal.jica.go.jp/library/HICSBooks/DetailsSearch.php

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). (1999). The study on the tourism development plan in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: Final report. Pt. II. -Development plans for priority areas. Retrieved from https://libportal.jica.go.jp/library/HICSBooks/DetailsSearch.php

- Kauppila, P., Saarinen, J., & Leinonen, R. (2009). Sustainable tourism planning and regional development in peripheries: A nordic view. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9(4), 424–435. doi: 10.1080/15022250903175274

- Kent, M. (2006). From reeds to tourism: The Transformation of territorial conflicts in the titicaca national reserve. Current Issues in Tourism, 9(1), 86–103. doi:10.1080/13683500608668240

- Ladkin, A., & Martinez Bertramini, A. (2002). Collaborative tourism planning: A case study of Cusco, Peru. Current Issues Tourism, 5(2), 71–93. doi:10.1080/13683500208667909

- Mcculloch, G. (2004). Documentary Research. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203464588

- Meyers, D., Budruk, M., & Andereck, K. (2010). Stakeholder involvement in destination level sustainable tourism indicator development: The case of a southwestern U.S. mining town. In R. Phillips & M. Budruk (Eds.), Quality of life and community indicators for parks, recreation and tourism management (pp. 185-199). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Morrison, A. M. (2013). Marketing and managing tourism destinations. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Morse, J. M., & Field, P. A. (1995). Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Moscardo, G. (2011). Exploring social representations of tourism planning: Issues for governance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4–5), 423–436. doi:10.1080/09669582.2011.558625

- Murphy, P. E. (1985). Tourism: A community approach. London: Routledge.

- O’Leary, Z. (2014). The essential guide to doing your research project (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Parsa, H. G. (2015). Sustainability, social responsibility, and innovations in tourism and hospitality. Oakville, ON: Apple Academic Press.

- Petra development and tourism region authority. (2019) Recent projects in the Petra region. Retrieved from http://pdtra.gov.jo/Pages/viewpage?pageID=8

- Pucako, L., & Ratz, T. (2000). Tourist and residents perceptions of physical impacts of tourism at Lake Balaton, Hungary: Issues for sustainable tourism management. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 8(6), 458–478. doi:10.1080/09669580008667380

- Puppim de Oliveira, J. A. (2003). Governmental responses to tourism development: Three Brazilian case studies. Tourism Management, 24(1), 97–110. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00046-8

- Ragas, M. W., & Roberts, M. S. (2009). Communicating corporate social responsibility and brand sincerity: A case study of chipotle Mexican grill’s “food with integrity” program”. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 3(4), 264–280. doi:10.1080/15531180903218697

- Richards, G., & Hall, D. (2000). The community: A sustainable concept in tourism development? In G. Richards & D. Hall (Eds.), Tourism and sustainable community development. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203464915

- Ritchie, B. J. R., & Crouch, G. I. (2003). The competitive destination: A sustainable tourism perspective. UK: CAB International.

- Ruhanen, L. (2009). Stakeholder participation in tourism destination planning another case of missing the point? Tourism Recreation Research, 34(3), 283–294. doi:10.1080/02508281.2009.11081603

- Sautter, E. T., & Leisen, B. (1999). Managing stakeholders a tourism planning model. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 312–328. doi:10.1016/S0160-7383(98)00097-8

- Scott, J. (2014). A matter of record: documentary sources in social research. Oxford: Wiley.

- Simpson, K. (2001). Strategic planning and community involvement as contributors to sustainable tourism development. Current Issues in Tourism, 4(1), 3–41. doi:10.1080/13683500108667880

- Smeltzer, L. R., & Zener, M. F. (1992). Development of a model for announcing major layoffs. Group & Organization Management, 17(4), 446–472. doi:10.1177/1059601192174009

- Southgate, C., & Sharpley, R. (2002). Tourism, development and the environment. In R. Sharpley & D. J. Telfer (Eds.), Tourism and development: concepts and issues (pp. 231–262). Toronto: Channel View Publications.

- Tarawneh, M. B., & Wray, M. (2017). Incorporating Neolithic villages at Petra, Jordan: An integrated approach to sustainable tourism. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 12(2), 155–171. doi:10.1080/1743873X.2016.1165231

- Telfer, D., & Sharpley, R. (2008). Tourism and development in the developing world. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203938041

- Thyne, M., & Lawson, R. (2001). Research note: Addressing tourism public policy issues through attitude segmentation of host communities. Current Issues in Tourism, 4(2–4), 392–400. doi:10.1080/13683500108667895

- Tosun, C. (2000). Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management, 21(6), 613–633. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00009-1

- Tosun, C., & Jenkins, C. L. (1998). The evolution of tourism planning in third-world countries: A critique. Progress in Tourism and Hospitality Research Program. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 4, 101–114. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1603(199806)4:2<101::AID-PTH100>3.0.CO;2-Z

- Treuren, G., & Lane, D. (2003). The tourism planning process in the context of organised interests, industry structure, state capacity, accumulation and sustainability. Current Issues in Tourism, 6(1), 1–22. doi:10.1080/13683500308667942

- UNESCO. (1993). A plan for safeguarding Petra and its surroundings, published in the World Heritage newsletter, No. 2. Retrived from http://whc.unesco.org/en/newsletter/2/

- UNESCO. (1994). Petra national park management plan. Paris: Author.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). (2006). Jordan tourism development project (Siyaha). Washington, DC: USAID.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). (2008). Jordan tourism development in the Petra region (JTDPR). Washington, DC: USAID.

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID). (2014). Economic growth through sustainable tourism project. Washington, DC: USAID.

- United States National Park Service (USNPS). (1968). Master plan for the protection and use of the Petra national park. Amman: Petra National Trust.

- United States National Park Service (USNPS). (2000). Petra archaeological park operating plan. Washington DC: USNPS.

- US/ICOMOS. (1996). The study on the management analysis and recommendations for the Petra world heritage site. Washington, DC: Author.

- Weber, R. P. (Ed.). (1990). Basic content analysis (Vol. 49). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yoon, Y. (2002). Development of a structural model for tourism destination competitiveness from stakeholders’ perspectives. Blacksburg, USA: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- Yuksel, F., Bramwell, B., & Yuksel, A. (1999). Stakeholder interviews and tourism planning at pamukkale, Turkey. Tourism Management, 20(3), 351–360. doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00117-4

Appendix A:

Resources of the analyzed documents

As mentioned in the body of the paper, authors retrieved the documents from the archives and websites of the PDTRA and MOTA, however, readers can access the plans using the following links:

JICA plans: https://libportal.jica.go.jp/library/HICSBooks/DetailsSearch.php

USAID plans: https://www.usaid.gov/results-and-data/planning

UNESCO plans: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/326/documents/

Appendix b:

Documentary evidence selection criteria, Scott (Citation2014)

Appendix C:

Raw results of the content analysis

Notes: Between the years of 1934 and 1995, the management of Petra was located in Amman, under the DoA and MoTA. However, after 1 year of running the region, PDTRA realized that they need a long team plan to develop the tourism and community in the region. This trend based on the management’s responsibilities to the region. The aim of the establishment of protected areas and authorities in Jordan is to manage cultural heritage sites. PDTRA aims to develop the region, economically, socially, culturally, and as a tourist destination, as well as contribute to local community development.

The management announced an international request for a plan’s proposal seeking a company to provide a master plan for 20 years. The management requested a plan that should be based on a “study that covers the entire Petra Region, focusing on the main urban areas, and the key natural landscape and environmental areas associated with the UNESCO World Heritage Site and archaeological park. The PAP must be looked at from a strategic point of view, as Park Management Plans have already been developed. The Strategic Master Plan should also address urban efficiency, economic and social development including all six local communities, mobilization of private sector investment and participation, balanced with the protection of the archaeological park itself”. (ATC, Citation2011).

After 43 years of planning, the local community especially the ordinary residents have been involved in the planning process. the consultants of ATC stated that: “Among these stakeholders are governmental institutions, which in specific areas have a strong say (e.g. archaeological protection or use of land), as well as protective bodies such as UNESCO, PNT or RSCN. Of great importance are the local populations of the six communities, the Bedouin tribes (1) with their traditions and all stakeholders involved in the regional tourism industry. Special attention must be paid to the 19 associations and cooperatives located in the region, which already present an encouraging basis for an increasingly active engagement of the regional population in planning for their future well-being”