Abstract

Households living in rural areas of developing countries rely on rain-fed agriculture for their livelihoods and, as such, are highly dependent on climatic conditions. The study is located in Gwanda a dry southern region of Zimbabwe. This study unearths and assesses the livelihood resilience strategies households employ to fight food insecurity in the face of harsh climatic conditions. Thus enhances understanding on how households in the area manage drought and also assist in guiding targeted interventions on areas in similar contexts. The researcher adopted a mixed methods approach were Qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques were used. Data were collected using questionnaires, key informant interviews, focus group discussions and observations. Probability random sampling was used to select 284 respondents. The study revealed that increased frequency and periodicity of drought has created a crisis of food insecurity. To fight this, households engage in several on-farm strategies. These strategies are effective and efficient in reducing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity. Challenges such as the increased frequency and periodicity of drought, environmental degradation, water scarcity, inadequate knowledge and skills and shortage of financial capital reduce the effectiveness of the strategies employed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

An earlier version of this article was presented at the National Symposium on Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation in Zimbabwe on 22 November 2018 at The Bronte Hotel in Harare. I thank its participants, especially Farai Muguwu, the founding Director of the Centre for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG) for useful feedback, as well as the article’s anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. There is no potential conflict of interest on this article. The research work in this paper examines how rural communities adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change, in particular livelihood diversification strategies in the face of water scarcity.

1. Introduction

Climate change and associated stressors influence human development through their support or destabilization of the livelihood systems of the poorest and most vulnerable people. There is now a broad scientific consensus that climate change is unavoidable (IPCC, Citation2007). Recent evidence and projections indicate that global climate change is likely to increase the incidence of natural hazards, including the variability of rainfall, temperature and occurrences of climatic shocks (IPCC, Citation2012). Climate-related issues and farmers’ livelihood strategies are different in different parts of the world. For instance, many farmers in Nepal and north east India suffer from droughts and intermittent floods, whereas coastal Bangladesh is a “hotspot” of climate change (Nicholls et al., Citation2007). As an attempt to overcome some of the climatic and non-climatic challenges, farm households diversify their livelihood sources (Brown, Stephens, Ouma, Murithi, & Barrett, Citation2006).

Over 40% of the earth’s land surface are drylands encompassing arid and semi-arid and dry sub-humid climatic zones that are inhabited by around 2.5 billion people who are mainly dependent upon the natural resource base for their livelihood (MA, Citation2005). The climatic conditions in dryland regions are harsh, there are high temperatures and low and erratic precipitation. These harsh climatic conditions have been exacerbated by climate change and they have caused chronic food insecurity and long-term drop in agricultural production (UNDP, Citation2009). According to Withgott and Breman (Citation2011), since 1985, world grain production per person has fallen by 9% and every 5 s, somewhere in the world, a child starves to death. This implies that research on resilience strategies in the context of harsh climatic conditions is necessary to relieve people from suffering and improve their standards of living.

The prevailing and anticipated harsh climatic conditions are therefore a threat to rural livelihoods and food security in Africa, among other parts of the world. UNDP (Citation2009) reveals that it is estimated that by 2020 between 75 and 250 million people are likely to be exposed to increased water stress and that rain-fed agricultural yields could be reduced by up to 50% if practices remain unchanged in some countries in Africa. As noted by UNDP (Citation2009), these changes will place additional pressure on already overstretched food supply systems in African drylands and undermine further the livelihoods of small scale farmers in areas with high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall. Owing to this, there is need for stepped up efforts to adapt to and mitigate the effects of low and erratic rainfall and temperatures.

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country that is generally dry and warm. Over 70% of the country’s population stays in rural areas and the majority of people in the country depend on agriculture and its related activities (IFAD, Citation2001). Moreover, studies reveal that Zimbabwe is getting more vulnerable to climate changes, and the local climatologists predict that there will be reduced productivity of crop-livestock systems in the country’s marginal rural areas. In addition, negative economic impacts of aridity, such as increased food prices, diversion of resources towards relief, loss of employment opportunities, compromised hydro-based industries and increased poverty and diseases are anticipated due to reduced agricultural production and pressure on food security (Siamachira cited in the Sunday Mail of 10 April 2011).

1.1. Statement of the problem

The debate over climate change has now reached a stage where all but the most extreme contrarians accept that, whatever happens to future greenhouse gas emissions, we are now locked into inevitable changes to climate patterns. Therefore, ways to adapt to climate change and reduce vulnerability have become hot topics of public concern (UNDP, Citation2014),

A better understanding of the factors driving diversification by rural households would therefore provide insights into the role of diversification in poverty reduction, food security and development. It would also help design policies that explicitly address diversification as possible determinants of future levels of welfare and foster institutions to support welfare-improving diversification The majority of households in hot and dry areas such as Ward 11 in Gwanda South whose livelihoods are heavily dependent on rain-fed agriculture are vulnerable to food insecurity as a result of the prevailing and anticipated climatic conditions. .

1.2. Aim of the study

To assess the effectiveness of the livelihood resilience strategies that has been employed by people in the face of harsh climatic conditions in Ward 11 in Gwanda South.

1.3. Objectives of the study

To identify the resilience strategies being built by people.

To evaluate how these strategies have empowered them.

To assess the challenges faced by people in their quest to build resilience.

To make recommendations on what can be done to improve people’s resilience.

1.4. The study area

The study was conducted in ward 11 in Gwanda South which lies in the south-western part of Zimbabwe. Gwanda is located in the hottest and driest region of the country, that is region five with Chiredzi, Beitbridge, Hwange, Malipati and Chirundu (Mujaya & Mereki, Citation2006). It is bordered by Plumtree to the North-west, Bulawayo to the North, Zvishavane to the North-east, Beitbridge to the South and Mwenezi to the South-east (Mandizvidza, Citation2006). Ward 11 is located on the South of Gwanda town, with its furthest village, that is, Mandiwongola, located 91 km away from Gwanda town. It has seven villages namely, Ntalale, Mamsisi, Manayange, Nyambi, Tshongwe, Phumula and Mandiwongola.

1.4.1. Conceptual delimitations

The study was carried out in an area where the temperatures are high, ranging from 22 to 30°C and low and erratic rainfall, averaging 350 mm annually is received (Siamachira cited in the Sunday mail of 10 April 2011). The soils are generally poor, infertile, and sandy and associated with high seepage rates (Mandizvidza, Citation2006). The vegetation consists of Mopane woodlands and Acacia tree/shrub savanna (Mujaya & Mereki, Citation2006). According to Siamachira (Citation2011), every five years, drought occurs for at least three years in Gwanda, where ward 11 is located and small scale agriculture is the main source of livelihood in the study area. Gwanda rural has a population of 116,658 people. Ward 11 has a population of 6,260 which is almost 5% of the population of Gwanda rural. The study area has 1,065 households, which are under the jurisdiction of Chief Mathe (Gwanda Rural district Council, 2012). It also has a rural service centre which consists of a clinic, police station, Agritex office and several shops.

1.5. Conceptualization of livelihoods

Consequently, there is a human imperative to frame research and practice on climate change around livelihoods. A livelihood is understood to comprise “the capabilities, assets (stores, resources, claims and access) and activities required for a means of living” (Chambers and Conway, Citation1992). Within the field of development, the concept of livelihoods has drawn from diverse origins to evolve into a more coherent set of ideas during the past two decades. The development of a “sustainable livelihoods framework” accelerated the extension of livelihoods research into the worlds of policy and practice. This framework was developed for use by international agencies to guide programmes for poverty alleviation by situating household livelihood assets within wider sets of ecosystems, cultural contexts and policies that promote or hinder access to these diverse resource inputs (Ashley and Carney, Citation1999; Ellis, Citation1998).

Livelihood resilience therefore highlights the role of human agency, and our individual and collective capacity to respond to stressors. People and their lives are too often reduced to homogenized vulnerable communities or countries, becoming merely “resilient pixels” (Weichselgartner and Kelman (Citation2014).

In contrast, a livelihood resilience approach emphasizes people’s capacity for, and differences in, perceiving risk and taking anticipatory actions, either individually or collectively. Information and resource flows through social networks (as understood in theories of social capital) are vital inputs to resilience, providing informal insurance, and delivering accessible financial, physical and logistical support in the midst of environmental disturbances (Aldrich, Citation2012)

1.6. Threats to sustainable livelihood

1.6.1. Climate change

According to UNDP (Citation2014), climate change is rapidly taking place in dry land regions and it is causing serious reductions in agriculture production whilst agriculture and its linked activities are the backbone of the rural economy. It is estimated that increasing temperatures will expose between 75 and 250 million people to increased water stress by 2020 and that rain-fed agricultural yields could be reduced by up to 50% in some countries in Africa if production systems remain unchanged (Cooper et al, Citation2009). According to UNEP (Citation2009), climate change is aggravating some challenges to rural livelihoods that result from urban expansion, exponential population growth, land degradation and unsustainable farming systems. It reduces the viability of rural livelihood resilience strategies that are being employed to buffer against shocks and stresses in the face of harsh climate conditions.

1.7. On-farm livelihood resilience strategies

1.7.1. Growth of drought tolerant crops

Some drought-resistant crops such as sorghum, millet and chick peas can thrive and yield relatively well even with high water scarcity within the shortened length of the growing season, as they mature before the depletion of soil moisture thereby reducing the threat from dry spells. In addition, maize varieties that stall seed development during periods of drought are selected and grown in drought prone areas for their with drought tolerant characteristics such as their ability to accumulate sugars and salts to protect against water loss (UNDP, Citation2009).

In Zimbabwe, three main small grains are grown in the drier regions of the country, in region III, IV and V. These are sorghum, known as amabele (Ndebele) and mapfunde (Shona), pearl millet, known as inyawithi (Ndebele) and mhunga (Shona) and finger millet, known as uphoko (Ndebele) and rukweza or njera (Shona).

According to Glover (Citation1959), sorghum possesses drought resistance mechanisms, such as deep, extensive and fibrous root systems and an efficient stomatal apparatus. It is tolerant to drought and can grow well on poor sandy soils than other grain crops. Whingwiri, Mashingaidze, and Rukuni (Citation1992) reveal that millet is adapted to warm and dry climates and good yields can be obtained from the crop with as little as 250 mm of rainfall, provided it is well distributed. Cooper et al. (Citation2009) reveal that pearl millet can grow in drier and sandier soils; however, it is not as drought resistant as sorghum because it does not go dormant during drought periods. The crop is praised for its ability to give economic yields, and grow well in soil conditions too poor and too worn out to support other cereal crops. Furthermore, finger millet is a drought tolerant crop grown in the marginal rural areas of Zimbabwe. According to Whingwiri et al. (Citation1992), the crop can produce higher yields from as little as 375 mm of well distributed rainfall and in drier regions, it can ripen in four months, hence it is a useful adaptation crop where late rains are in unreliable.

1.7.2. Crop rotation

According to Bennet (Citation2001), crop rotation is a more or less regularly recurrent succession of different crops on a single piece of land in a planned sequence. This farming practice improves soil productivity as it ensures extraction of nutrients from all levels of the soil which results from the fact that different crops have different rooting depths (Mujaya & Mereki, Citation2006). In addition, crop rotation conserves soil and water and increases the water holding capacity of soils by improving their structure (UNDP, Citation2009). Thus crop rotation is a common livelihood resilience strategy in dryland regions.

1.7.3. The introduction of small scale irrigation

Irrigation is the application of water to the soil for good crop growth. It is practiced if there will be inadequate or no rainfall for farmers to successfully grow crops (Mandizvidza, Citation2006). It seeks to supply moisture when rainfall is totally inadequate for plant growth, extend the growing season and permit growth of crops during the dry season (Mujaya & Mereki, Citation2006). According to UNDP (Citation2009), the introduction of small-scale irrigation has been adopted as a livelihood resilient strategy in dryland regions. It reduces farmers’ dependence on rain-fed agriculture and increases food security.

1.7.4. Conservation tillage

It is a common livelihood resilient strategy in areas with high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall because the residue cover left on the soil reduces water run-off thus allowing more water to penetrate the soil and also reduces evaporation, thus maximizing the use of available water (FAO, Citation1987). However, conservation tillage is time consuming and labour intensive such that many people view it as a resource wasting strategy rather than a valuable livelihood resilience strategy in dryland regions (Weiss, Citation1992).

1.7.5. Agroforestry

According to Nair et al. (Citation2009), woody perennials are able to explore a larger soil volume for water and nutrients, provide better soil cover and reduce surface run-off, all of which reduce the impacts of drought and extreme rainfall. In addition, woody perennials help to build soil carbon which in turn increases efficiency in water and nutrient use. Furthermore, tree-based agricultural systems often provide additional benefits, such as fruits, fodder, fuelwood and timber. By so doing, agroforestry diversifies the production system and buffer against weather related production losses, thus raising small holder resilience against climate impacts.

1.7.6. Supplementary feeding of livestock

Livestock supplementation is common during droughts and many livestock herders or pastoralist staying in areas with harsh climatic conditions has employed it to reduce the death rates of their livestock. Hove, Chakoma, and Nyathi (Citation2004) noted that in areas with seasonal rainfall, important livestock grasses decline drastically in both quality and quantity during the non-rainy season. It is during this period that livestock lose weight or even die if the remaining feed is exhausted. As a result, livestock herders who stay in dryland regions view provision of supplementary feed as a valuable livelihood resilience strategy although poor farmers sometimes fail to purchase commercial livestock feed because of lack of financial capital. As noted by FAO (Citation2007), it is vital for farmers for providing supplementary feeding to provide the desired amount of supplement at the right rate, since the effectiveness and economics of any supplementation programme depends on all animals consuming the desired amount of supplement at the right rate.

1.7.7. Providing water for livestock

According to UNDP (Citation2004), inadequate water supplies in areas with high temperatures and low and erratic precipitation is one of the most limiting factors to livestock productivity especially when there is drought. As a result, livestock herders in areas with harsh climatic conditions water their stock in hand-dug wells at the edge of the pans or occasionally in syndicate boreholes in areas where underground water is not too saline (Mogotsi, Nyangito, & Nyariki, Citation2011). It is believed that provision of water for livestock if surface water sources dry up goes a long way into making sure that people do not lose their livestock in the face of harsh climatic conditions. However, this can be tiresome and labour-intensive to farmers with very big herds of livestock (UNDP, Citation2009).

1.7.8. Moving livestock to other grazing areas

Livestock have to seasonally track the scattered available forage because of the non-equilibrium dynamics of semi-arid ecosystems. According to Mogotsi et al. (Citation2011), movement of livestock to areas with secure water and pastures remains important for herders in dryland regions and when employed it can buffer against animal loss of weight or death.

2. Methodology

The researcher used several questionnaires, interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs) and observations to collect primary data on livelihood resilience strategies in the face of harsh climatic conditions in ward 11 in Gwanda South during the period of November 2016 to March 2017. According to ZIMSTAT (Citation2012) report, ward 11 has a total of 1,075 households. The study used probability sampling methods in the selection of respondents. Specifically, probability random sampling to households that would take part in the study. Computer generated random number tables were used in the selection of respondents (Chitongo, Citation2017) and the random numbers were generated using MS Excel 2010. The sample size calculator (https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/sample-size-calculator/) was used to calculate the required sample size. The calculations were based on the assumption that the population from which the sampled farmers were drawn was normally distributed. The confidence interval for the sample was set at 95% and the margin of error was 5%. Based on the above calculation, the sampled households were 284. Questionnaires comprising of open-ended, multiple response and dichotomous questions were administered to 284 household heads which were selected randomly from four villages, out of the ward’s seven villages. The questions which were included in the questionnaire were about on farm resilience strategies, relevance and appropriateness of livelihood resilience strategies, efficiency, effectiveness and adequacy of livelihood resilience strategies and the challenges faced by households in building resilience in hot and dry regions. Purposive sampling was used to select four villages from the study area’s seven villages namely Tshongwe, Nyambi, Ntalale, Mandiwongola, Mamsisi, Phumula and Manayange. From these Tshongwe, Nyambi, Ntalale and Mandiwongola were selected. Interviews with the key informants were done in the local languages (Ndebele and Sotho) understood by the respondents to avoid misrepresentation. Three interviews were done with local Agriculture Technical and Extension Services (AGRITEX) officer, the village head and an NGO representative who were purposively selected. Data collected from the interviews included the changes in the rainfall patterns, strategies used by the households in Ward 11 and also an evaluation of the strategies and how they have contributed to resilience or rural farmers. Data were also collected through Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and in this case, a total of four FGDs were carried out in Ward 11 in Gwanda South. Each FGD had 10 conveniently selected participants, making a total of 40 respondents. The household heads who did not respond to the questionnaire survey provided information about the on-farm strategies that they use in the face of climate change, the effectiveness of the resilience strategies and the challenges that they face. Before commencing with the actual field survey, a pilot study was done and this helped in eliminating and rephrasing ambiguous questions to inform the final questionnaire.

3. Results and analysis

3.1. Livelihood resilience strategies employed in ward 11 Gwanda South

Table shows the major on-farm livelihood resilience strategies employed in ward 11 in Gwanda South. The multiple responses to an open ended question on the issue of on farm livelihood resilience strategies used in Ward 11 Gwanda South.

Table 1: On farm livelihood resilience strategies in ward 11 Gwanda South

Households in ward 11 Gwanda South engage in several on-farm livelihood resilience strategies to improve productivity of crop-livestock systems in the context of high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall, that is exacerbated by climate change. Most of the strategies they employ focus on improving efficiency in the management, use and storage of rainwater for better yields in crop production and increasing the accessibility of food and water to livestock, vital biological needs which are inadequately supplied by the natural environment, in an attempt to improve the quantity and quality of their livestock.

The results of the study from the key informants and the FGDs indicated that there were a number of on farm strategies which were used by the households. Most of the answers were in-line with the answers provided by the household heads. The following were excerpts from the interviews:

AGRITEX officer: There are a number of on farm strategies which are commonly used as a strategy and these include growing drought resistant crops which do not require a lot of rainfall, providing livestock with supplementary feed and also increasing the spacing distance. These measures go a long way in increasing resilience of the households in Gwanda South.

Village head: The people of Ward 11 mainly rely on the growth of drought resistant crops which can withstand the low rainfall that is always received in this area. Crops such as millet and sorghum which can be sold at high prices.

NGO officer: In Gwanda South and mainly Ward 11, there is erratic rainfall which is received and as a result, cattle are an assert in this place and a number of household heads use supplementary feeds such that the animals can survive.

FGDs. We have a perennial problem of erratic rainfall and the ever increasing temperatures in Gwanda South in general and crops are failing and we are relying on livestock water supplementation. We also supplement the feeds as livestock are a means to survival especially in the times of crop failure.

3.2. Relevance and appropriateness of livelihood resilience strategies employed in ward 11 in Gwanda South

3.2.1. The growth of drought resistant crops

Households in ward 11 in Gwanda South reveal that they rarely come from the fields empty handed when they grow sorghum and pearl millet since these crops are adapted to warm and dry climates and they possess drought resistance mechanisms such as deep, extensive and fibrous root systems and an efficient stomatal apparatus that make them yield well in areas with rainfall below 300 mm. Furthermore, some short seasoned maize varieties are proper and germane for enabling successful crop production in regions with low and erratic rainfall because they stall seed development during periods of drought, some are better at taking up water while others have the ability to accumulate sugars and salts to protect against water loss. This indicates that the growth of drought resistant crops is relevant and appropriate in improving households’ resilience and reducing their vulnerability in the face of high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall.

3.2.2. Intercropping

The growth of more than one crop on the same piece of land simultaneously makes a positive contribution towards reducing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity as farmers practicing it benefit from a balanced diet resulting from the production of different crops with different nutritional values. For example, households in ward 11 in Gwanda South reveal that in most cases they harvest water melons and melons for household consumption and/or for sale if severe drought precludes the successful growing of grain crops. Moreover, they usually harvest at least something from sorghum and millet even if rainfall becomes too little for some short-seasoned maize varieties to yield anything.

Intercropping is a pertinent and apt strategy that can reduce household’s vulnerability to food insecurity in the face of harsh climatic conditions.

3.2.2.1. Increased crop spacing

From the questionnaires it can be noted that there was less moisture available for plant growth and as such intercropping was a method to conserve moisture. In a region with limited amounts of soil moisture, increased crop spacing is important because it reduces the rate of water uptake by plants thus reducing the quick depletions of soil moisture and increasing chances of its availability throughout crops’ growing season.

3.2.2.2. Conservation agriculture

From the study a number of farmers carried out conservation agriculture which encompasses the techniques of minimum mechanical soil disturbance, top soil management for the creation of a permanent organic cover and crop rotation positively contributes towards improving households’ resilience in the face of high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall. Conservation agriculture is therefore relevant and appropriate as a strategy employed to reduce households’ food insecurity in a dryland region, as it achieves both sustained agricultural production and environmental conservation.

3.2.3. Livestock water supplementation

There are few dams in ward 11 in Gwanda South and these few dams are heavily silted to collect and store adequate water for agricultural uses during the non-rainy season. As a result of siltation combined with other problems such as too low and erratic rainfall and high temperatures, the majority of dams dry up long before the rainy season depriving livestock of water, a vital biological need and exposing them to high mortality rates emanating from water scarcity. Livestock water supplementation is material and appropriate in ensuring livestock survival in a water scarce region. In ward 11 in Gwanda South, it plays an unutterable role in improving the resilience of livestock and people.

3.2.4. Livestock feed supplementation

Livestock feed supplementation is apt and germane in improving the resilience of livestock and ensuring their survival in areas with low, erratic and seasonal rainfall. To make matters worse, this non-rainy season, especially August to October is a critical period during which livestock such as cows and goats are in their final trimester of pregnancy and in need of adequate food and water, which is usually inadequately supplied by the natural environment during the moment. It is therefore fundamental and right for farmers in dryland regions to practice livestock feed supplementation in order to improve the robustness of their livestock and reduce their mortality rates.

Livestock feed supplementation is therefore fitting and applicable in areas with low and erratic rainfall that have a degraded natural resource base, such as ward 11 in Gwanda South.

3.2.5. Moving livestock to better grazing areas

It is apropos and suitable to move livestock to better grazing areas in response to the non-equilibrium dynamics of semi-arid ecosystems such as found in the study area that compel livestock to seasonally track the scattered available forage. This strategy can be adopted instead of livestock water and feed supplementation by farmers with big herds who can hardly provide the desired amounts and quality of food and water supplements to their livestock. Movement of livestock to areas with secure water and pastures increases the accessibility of food and water to livestock, hence, it is worthwhile in improving households’ resilience in the face of harsh climatic conditions.

3.3. Efficiency, effectiveness and adequacy of livelihood resilience strategies employed in ward 11 in Gwanda South

3.3.1. Crop yields

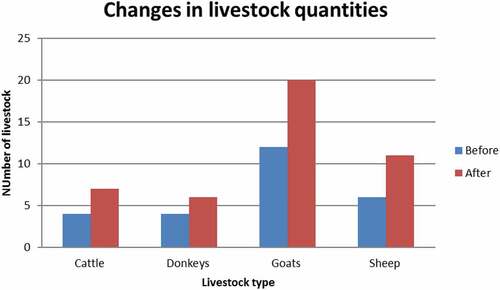

Figure shows changes experienced by households in ward 11 in Gwanda South in crop productivity as a result of the livelihood resilience strategies employed.

Figure 1. Changes in average annual crop yields per household resulting from the livelihood resilience strategies employed.

Livelihood resilience strategies employed by households in ward 11 in Gwanda South are effective and efficient in curtailing their vulnerability to food insecurity in the face of harsh climatic conditions as they increase crop yields. On-farm livelihood resilience strategies such as increased crop spacing, conservation agriculture and intercropping lead to efficiency in the storage and use of the limited amount of soil moisture, thus, increasing its chances of availability throughout the growing season of crops. Additionally, off-farm strategies provide households with financial resources to acquire an improved quality and quantity of agricultural equipment, which usually leads to improved yields. The livelihood resilience strategies employed by households in ward 11 in Gwanda South are effective, efficient and good enough in reducing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity in the face of harsh climatic conditions.

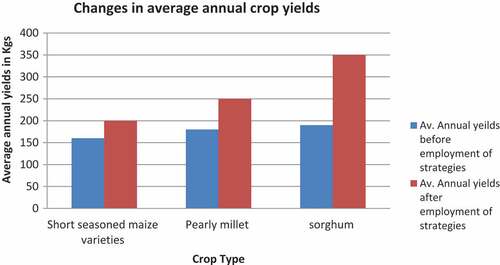

3.3.2. Quantity of livestock

Figure shows changes in livestock quantity that have been brought by livelihood resilience strategies employed in ward 11 in Gwanda South.

The above information endorse the view that the employment of several strategies that is livelihood diversification, usually improve livestock ownership in rural areas By so doing, the livelihood resilience strategies employed by households in ward 11 in Gwanda South curtail their vulnerability to food insecurity since livestock directly provide food in the form of milk and meat to people, generate money that can be used to buy food when sold and are a source of drought power, an essential input in the process of food production in rural areas.

Livelihood resilience strategies employed in ward 11 in Gwanda South have the aptitude to decrease households’ vulnerability to food insecurity in hot and dry regions.

3.4. Challenges faced by households in ward 11 in Gwanda South in their quest to build resilience in a hot and dry region

Based on qualitative data from the interviews with the key informants and the FGDs with the household heads, there were a number of challenges that were indicated to be affecting their quest to build resilience in hot and dry regions. Some of the identified challenges were in the form of increased frequency of droughts which led to water scarcity in the region, environmental degradation in its different forms and shortage of financial capital. Excerpts from the interviews indicated the following:

Agritex officer: Matebeleland South in general has been facing recurrent and unpredictable droughts are among the major challenges that compromise their ability to build sustainable livelihoods. More over the recurrent droughts lead to reduced productivity of crop livestock systems thereby lessening the efficiency and effectiveness of a myriad of on-farm strategies households employ to curtail their vulnerability to food insecurity

Village head: There are very few dams that we have here in Ward 11 and they do not last long as they dry up long before the rainy season around July to August as such there is much pressure on the available boreholes and hinder their ability to meet all the households’ water requirements. This impacts negatively on what people do, limit their room to manoeuvre and increases their vulnerability.

FGDs: The levels of environmental degradation is ever rising in Ward 11 and this can be noted through the depletion of soil, grasslands and forests by both natural and anthropogenic causes and people in their quest to build resilience in the face of harsh climatic conditions and an unstable macroeconomic environment. This decreases households’ productivity on the natural resource. Other than environmental challenges, there is a challenge in the form of lack of financial capital to improve the existing livelihood resilience strategies, introduce some economically viable strategies and sustainably utilize the natural resource base, is in short supply

Results from quantitative data indicated that the challenges which were indicated by the key informants and through the FGDs are the same with the challenges which were indicated by the household heads when they responded to questionnaires. The challenges noted were increasing frequency of droughts, inadequate knowledge and skill, birds and water scarcity during the dry season. The challenges are presented in detail below.

3.4.1. Increased frequency and periodicity of drought

Households in ward 11 in Gwanda South who depend on rain-fed agriculture reveal that recurrent and unpredictable droughts are among the major challenges that compromise their ability to build sustainable livelihoods. This reduces productivity of crop livestock systems thereby lessening the efficiency and effectiveness of a myriad of on-farm strategies households employ to curtail their vulnerability to food insecurity. Moreover, it makes agricultural based strategies to be more intensive and exclusive to some poor households who make the majority of rural households. Studies conducted reveal that the pastures are becoming more and more poor such that livestock feed supplementation now require the purchasing of a lot of commercial stock feed which is beyond the reach of many poor households. Furthermore, increased temperatures cause additional loss of moisture from the soil and increases crop failure in the context of several strategies, such as intercropping, increased crop spacing and growth of drought resistant crops. For example, in the 2011 to 2012 farming season, 45% of households in ward 11 in Gwanda South did not harvest anything, yet they employed a myriad of livelihood resilience strategies to improve productivity in crop production.

The increased frequency and periodicity of drought challenge and compromise households’ efforts to subsist on the land and gradually erodes their resilience in the face of harsh climatic conditions.

3.4.2. Water scarcity

Water, a vital part of the natural capital, has become a scarce commodity in ward 11 in Gwanda South largely because of the increased frequency and periodicity of drought that is exacerbated by the uneven distribution occurrence and availability of water sources. The few dams that are available dry up long before the rainy season around July to August which adds pressure on boreholes and hinder their ability to meet all the households’ water requirements.

3.4.3. Environmental Degradation

The potentially renewable resources such as soil, grasslands and forests in ward 11 in Gwanda South have been depleted or destructed by natural causes and people in their quest to build resilience in the face of harsh climatic conditions and an unstable macroeconomic environment. Additionally, it hinders the employment and viability of off-farm natural-resource based strategies, such as wildlife harvesting, firewood selling and river and pit sand selling, which could be safety nets to the majority of poor households without financial capital required for capital intensive strategies, such as poultry farming, formal trading and vending.

Environmental degradation obstruct households’ efforts to curtail their vulnerability to food insecurity in the face of harsh climatic conditions.

3.4.4. Shortage of financial capital

In ward 11 in Gwanda South, financial capital to improve the existing livelihood resilience strategies, introduce some economically viable strategies and sustainably utilize the natural resource base, is in short supply. Consequently, more than half of households in the study area are failing to move their livestock from a water stressed region with poor grazing land to better grazing areas. In addition, some households are compelled to watch their livestock starving to death as they lack the financial resources necessary for them to acquire commercial livestock feed supplements. Moreover, some households are economically weak to enjoy the benefits of livestock feed supplementation whose effectiveness and economics depends on all animals consuming the desired amount of supplement at the right rate. Furthermore, trapped in a cycle of money scarcity, the majority of households are unable to acquire production inputs essential for sustainable utilization of natural resources and they are compelled to engage in detrimental livelihood activities, such as deforestation, gold panning and illegal river/pit sand obstruction, thus further degrading the natural resource base on which they depend and extending their vulnerability context. More so, shortage of financial capital compel some households to waste their precious time on less-yielding strategies such basket and mat-making and to abstain from high-yielding and capital intensive strategies, such as poultry keeping, tailoring and hair-dressing.

3.4.5. Inadequate knowledge and skills

A larger percentage of households in the study area have low levels of education to build sustainable livelihoods. They lack the capacity to fully utilize the assets they have and improve their resilience in the face of harsh climatic conditions. For example, unaware of their negative results, they engage in detrimental agricultural habits such as cultivation of steep slopes, down-slope cultivation, stream-bank cultivation and overgrazing, thereby further degrading their of their limited open water sources through siltation, this widening their vulnerability context. Less appropriate and inadequate knowledge and skills limit households’ ability to manoeuvre in their quest to fabricate resilience in the face of harsh climatic conditions.

3.4.6. Granivorous birds

Granivorous (seed eating) birds such as doves and red billed quella birds cause extensive damage to drought resistant small grain crops such as millet and sorghum, which can thrive and yield relatively well even with high water scarcity within the shortened length of the growing season. Normally, these birds feed on grass seeds but, in the absence of these, they attack crops mainly at the dough stage, sucking out the soft grain.

Grainvorous birds, among other pests curtail the effectiveness and efficiency of the growth of drought resistant crops as a valuable livelihood resilience strategy employed to fight food insecurity.

4. Discussion

The results of the study indicated that drought resistant crops are the best option in dry regions and this is in line with the observation made by UNDP (Citation2009), households in ward 11 in Gwanda South view the growth of drought resistant crops as an indispensable tool in adapting to high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall. Drought-tolerant, fast growing crops such as sorghum, pearl millet and some short seasoned maize varieties can thrive and yield relatively well even with high water scarcity within the shortened length of the growing season. They mature before the depletion of soil moisture thereby reducing the threat from dry spells (Dar, Citation2009). They are therefore apt and apropos have production in regions with low and erratic rainfall as the enable households in the study area to harvest at least something from crop production in a region with low agricultural potential.

Findings from the study showed that Intercropping was a way in which the households in Ward 11 would built their resilience. The findings corroborate with Potter et al. (Citation2008) who indicated that intercropping is associated with higher yields per unit area compared to when a single crop is grown. This results from the fact that some crops such as legumes improve soil fertility through nitrogen fixation (Mujaya & Mereki, Citation2006), and that with several crops grown, farmers have a wider range of sources of harvests. Furthermore, intercropping is a valuable risk aversion strategy that usually provides farmers with other crops to fall back on if others fail. Intercropping is vital and necessary in regions with limited water amounts as it leads to efficiency in the use and management of rain-water through reducing evapo-transpiration and soil erosion due to improved crop coverage of the soil (FAO, Citation1987). Studies carried out testify this as they indicate that the growth of drought-resistant grain crops intercropped with legumes such as groundnuts, beans and roundnuts and creepers, including melons, water melons and pumpkins, leads to delayed depletion of soil moisture compared to the growth of a single crop.

Research findings indicated that intercropping was also a strategy used by households for the purposes of moisture conservation and this strategy enables households to harvest at least something in a region defined by Vincent and Thomas (Citation1961) as having too low and erratic rainfall that precludes the growing of even drought resistant crops, further giving testimony to the revelation made by Whingwiri et al. (Citation1992) that drought resistant crops such as pearl millet can generate good yields with as little as 250 mm of rainfall provided they are well distributed. In the content of high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall, increased crop spacing in relevant and appropriate in reducing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity. The results showed that conservation agriculture was a strategy used by households in Ward 11 in Gwanda South and the results are supported by FAO (Citation1987), households practicing rain-fed agriculture in a region with harsh climatic conditions applaud it for increasing efficiency in rainwater use through leaving some crop residues on the land on which new crops are grown, thereby leading to reduced surface run-off and increased infiltration, nutrient cycling and water holding capacity.

The findings of the study showed that there was shortage of forage for animals and as such there was need to introduce supplements. In the quest to improve the resilience of their livestock and themselves in a region with low agricultural potential, the employment of livestock water supplementation is relevant as UNDP (Citation2009) identifies inadequate water supplies in areas with high temperatures and low and erratic precipitation as one of the major limiting factors to livestock productivity especially when there is drought. As Hove et al. (Citation2004) observe, in semi-arid regions, important livestock grasses decline drastically in both quantity and quality during the non-rainy seasons leading to loss of weight and increased mortality rates in livestock. Furthermore, threats to sustainable livelihoods including, but not limited to climate change, hazards such as drought and environmental degradation have rendered livestock production based on the veld alone, identified as the most suitable agricultural activity in region five by Vincent and Thomas (Citation1961), risky and unsuitable. The natural pasture is severely deforestated to adequately meet all the nutritional needs for livestock both in quality and quantity.

Results indicated that there are a number of strategies that were introduced as measures for livelihood diversification. noted by scholars, such as Potter et al. (Citation2008), Bernsterin, Crow, and Johnson (Citation1991) and Satge et al. (Citation2002). This results from the fact that on-farm strategies such as gold panning, harvesting of mopane worms and internal saving and lending clubs, generate financial capital that can be used to buy livestock and some inputs required in their rearing and off-farm strategies such as livestock water and food supplementation improve the quality of livestock and reduce their mortality rates (Mogotsi et al., Citation2011).

The study identified a number of challenges that affected and increased frequency of droughts was one of them and these findings are further supported by Siamachira cited in the Sunday Mail of 10 April (Citation2011) every five years, drought occurs for at least three years in ward 11 in Gwanda South, among other wards in Gwanda. The increased droughts lead to water scarcity which impacts negatively on what people do, limit their room to manoeuvre and increases their vulnerability substantiating Potter et al. (Citation2008)’s assertion that those with few assets (five capitals) have a wider vulnerability context. Studies conducted in ward 11 in Gwanda South reveal that water scarcity hinders the introduction of some necessary strategies such as growth of grain crops under irrigation, make some strategies such as livestock water supplementation to be intensive and leads to diversion of the limited production inputs such as time and labour into the search for water. Water scarcity impede the ability of households to build sustainable livelihoods in hot and dry regions.

Findings indicated that environmental degradation was a challenge in Gwanda South specifically in Ward 11. The effects of the environmental degradation were that there was a decrease in households’ productivity on the natural resource base as Munowenyu (Citation1999) states that a degraded environment does not produce much to meet human needs and improve people’s living standards. Studies conducted corroborate this as they show that environmental degradation reduces grazing and cropping land and reduces the water carrying capacity of open water sources such as dams through siltation, thus, threatening the very existence of people and their livestock and reducing the viability of on-farm livelihood resilience strategies employed. As noted by Bebbington (Citation1999) trapped in the cycle of inadequate knowledge and skills (human capital) households’ efforts to diversify more widely and successfully are hampered if not completely thwarted.

Findings indicated that birds are a challenge in Ward 11 and the same was indicated by Civil Protection Organization of Zimbabwe (2009), who indicated that ward 11 in Gwanda South reveal that these birds are a threat to food security and they have forced some farmers to shift from growing the usual drought tolerant small grain cereals to growing maize which is not eaten by the birds. Consequently, the crop failure rate has increased because the climatic conditions in the area are too harsh for normal maize growth (Siamachira cited in the Sunday Mail of 10 April 2011).

5. Conclusion

Households in hot and dry areas including ward 11 in Gwanda South are vulnerable to food insecurity as a result of the prevailing and anticipated high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall. In ward 11 in Gwanda South, more than half of the households are trapped in a cycle of food insecurity characterized by less than three meals per day. To curtail this, they employ a myriad of livelihood resilience strategies both within and outside the agricultural field. The majority of these strategies are apt, germane, efficient, effective and good enough in lessening households’ vulnerability to food insecurity but they are inadequate in quality and quantity to fully eradicate it. Challenges such as the increased frequency and periodicity of drought, water scarcity and environmental degradation, shortage of financial capital, inadequate knowledge and skills and attack of drought tolerant small grains by granivorous birds reduce the effectiveness and efficiency of the strategies employed.

The most common on-farm strategies employed in ward 11 in Gwanda South are growth of drought resistant crops, conservation agriculture, increased crop spacing, intercropping, livestock water supplementation, livestock feed supplementation and moving livestock to better grazing areas. In addition to on-farm strategies, off-farm strategies including but not limited to gold panning, harvesting of mopane norms, food for work projects, internal saving and lending clubs, vending and basket and mat making are afoot. The preceding strategies help households to butter the adverse effects of high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall and thus lower their exposure to drought risk and in return avert or minimize their vulnerability to food insecurity.

The growth of drought resistant crops combined with other livelihood resilience strategies such as conservation agriculture, increased crop spacing and intercropping are appropriate and relevant in reducing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity in hot and dry regions. Studies conducted in ward 11 in Gwanda South reveal that they lead to efficiency in the management storage and use of the limited soil moisture, thereby increasing its chances of availability throughout crops’ growing season. In addition, they have enabled and improved crop production in a region that has been defined by Vincent and Thomas (Citation1961) as having low and erratic rainfall that precludes the growing of even drought resistant crops. By so doing they positively contribute towards curtailing households vulnerability context in the face of harsh climatic conditions.

Furthermore, strategies such as livestock water supplementation, livestock feed supplementation and moving livestock to better grazing areas are pertinent and proper in improving productivity and robustness of livestock in the face of harsh climatic conditions. They increase the accessibility of food and water that are necessary to achieving the growth potential of livestock, but inadequately supplied by the natural environment. Consequently, they benefit the performance, health welfare and growth rate of animals and also reduce their mortality rates. Thus they improve the resilience of livestock and households rearing them.

Moreover, the employment off-farm strategies is apt, germane effective, efficient and adequate in curtailing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity because, as noted by Bernsterin et al. (Citation1991) off-farm production activities augment agricultural yields, reduce households’ dependence on unreliable rain-fed agriculture and provide them with something to lean back on if agriculture fails to meet some or all their nutritional requirements. Off-farm production activities have the aptitude to lessen households’ vulnerability to food insecurity in hot and dry regions with low agricultural potential.

The myriad livelihood resilience strategies employed by households in ward 11 in Gwanda South have improved the consumption patterns of the majority of households and uplifted 34% of households in the study area to food security, contextually characterized by the ability to have three meals per day. Additionally, they have led to an improvement in the average annual crop yields, quality and quantity of livestock and production equipment owned and average annual earnings per household. Therefore, they have gone a long way into decreasing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity, thus they can serve this purpose in other communities in semi arid regions.

Households in hot and dry regions, who are vulnerable to food insecurity, emanating from the prevailing and anticipated harsh climatic conditions, engage in a myriad of livelihood resilience strategies to curtail their vulnerability. This fluidity and flexibility is necessary in regions exposed to a deep and wide vulnerability context because it creates a potrtfolio of livelihoods with different risk attributes so that risks can be managed exante and that recovery is easier ex post (Reardon cited in Mogotsi, Ngangito and Nyariki, Citation2011). The livelihood resilience strategies employed in ward 11 in Gwanda South empower households through improving crop yields, the quality and quantity of livestock and production equipment and income generation which in turn improve their consumption patterns. They further demonstrate the fighting spirit of households subsisting in drought prone regions with low agricultural potential, despite often being portrayed as passive victims.

6. Recommendations

6.1. Early warning systems and improved climate information

As a result of climate change, it is increasingly becoming difficult to predict the amount and timing of rainfall. Under such conditions, early warning systems and improved climate information can help farmers to take appropriate actions in a timely manner depending on expected weather conditions (UNDP, Citation2009). For example, early maturing varieties of drought resistant crops can be planted when rains are expected to start late and commercial livestock feed can be bought and stored in advance if severe drought is expected. Climate information dissemination to all rural dwellers should be facilitated and improved so that even those without access to the common mass media such as newspapers, televisions and radios will access the information and act upon it.

6.2. The construction of more dams and desiltation of existing ones

Dams are in short supply in ward 11 in Gwanda South and the existing ones are heavily sited to harvest and store adequate water for use during the long dry season. Consequently, the local people and various stakeholders involved in rural development should cohere resources and construct new dams and also desilt the existing ones. This will maximize the collection and storage of rainwater, solve or reduce the problem of water scarcity, facilitate growth of grain crops under irrigation, reduce pressure on boreholes and increase agricultural productivity. It could be far much better if efforts are made to construct the Thuli-Munyange (Elliot) Dam which was proposed in 1961 on the Thuli River by the colonial government.

According to Chibi, Kandori and Maakore (Citation2005), this dam has a carrying capacity of 33 mm3. It is expected to reduce or eradicate water scarcity in some parts of Gwanda South which include ward 11 when it is constructed and becomes operational. The construction of more dams and or the desiltation of existing dams may go a long way into curtailing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity as it will increase the quantity of rain water that will be harvested, stored and used in different production activities including agriculture, the centricity of food production in rural areas.

6.3. The introduction of large scale irrigation

The introduction of irrigation that can enable households to produce grain crops such as maize, wheat, sorghum and millet on a large scale can make a positive contribution towards households’ quest to improve their resilience in dryland regions. This may reduce their dependence on rain-fed agriculture which often leads to varied crop yields, crop failures and the risks of food insecurity (UNDP, Citation2009). It can also increase overall household food security and income. Furthermore, in a water stressed region, with high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall, irrigation can be more helpful as it will supply moisture when rainfall is totally inadequate for plant growth, permit the growth of crops during the dry season and extend the rainy season when it becomes too short (Mujaya & Mereki, Citation2006). This is likely to increase agricultural productivity and in turn curtail households’ food insecurity in hot and dry regions.

6.4. The harvesting and controlled feeding of all crop residues to livestock

The increased and controlled harvesting and feeding of all crop residues to livestock is a cost-effective measure that can benefit households in hot and dry regions and enable them to subsist in the face of harsh climatic conditions (Hove et al., Citation2004). According to Clatworthy (Citation1999), crop residues have a relatively high feed value and should be used as stock feed. Soon after harvesting and/or the realization that crops have really failed to yield anything, crop residues may be harvested and carefully stored to be used as livestock feed during drought and dry seasons, when the quantity and quality of pastures are low. This may lead to efficiency in the use of resources as it would increase the utilization of crop residues and decrease the sum of money that can be spent on the purchasing of commercial stock feed.

The harvesting and controlled feeding of all crop residues to livestock is a cost-effective measure of improving livestock productivity in the face of harsh climatic conditions. It can efficiently curtail households’ food insecurity within the context of financial capital scarcity.

6.5. Rotational grazing

Grazing schemes incorporating simple grazing rotations can improve the quality of the veld and halt the problem of environmental degradation through increasing uniformity of utilization of grazing land (Civil protection organization of Zimbabwe, 2009). Studies conducted in ward 11 in Gwanda South reveal that, under uncontrolled grazing, favoured areas and palatable plants are continuously defoliated without adequate rest. Thus, rotational grazing is one option available to give them a chance to grow out and increase in vigour. At least five paddocks per ward can be established and sustainably used and managed by communities with the assistance of stakeholders involved in rural development, such as the government and NGOs. According to Hove et al. (Citation2004), five paddocks are the minimum number which accords with both the technical and the physiological needs of rotational grazing systems.

Rotational grazing would increase the quality of the veld and uniformity of utilization of grazing land. Consequently, it can improve livestock productivity and thwart environmental degradation, thus positively contributing towards curtailing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity in hot and dry regions.

6.6. Improved soil and water management

Improved soil and water management is essential for maintaining the production of fodder and food crops under conditions with high temperatures and low and erratic rainfall (FAO, 2007). Soil erosion may be minimized or controlled through the reduction of surface water run-off by improving soil surface cover and the construction of physical structures, such as terraces and contour ridges. This also leads to increased infiltration, improved soil fertility and water conservation. However, in reality poor households are often reluctant to invest in improving soil and water management. This calls for the need for the stakeholders involved in rural development to put in place incentives for investments in better management of soil and water. It also calls for intensification of educational campaigns about the benefits of improved soil and water management that will make households to be more willing and able to invest in this vital and necessary strategy.

Improving soil and water management lead to efficiency in the use and storage of limited rain water, thus it can positively contribute towards decreasing households’ vulnerability to food insecurity in water stressed regions with high temperatures.

6.7. Provision of safety nets

In a region where droughts have seized to become surprises and are generally an expected phenomena, stakeholders involved in rural development, including the government and NGOs must always be well equipped to help people cope with them. There must always be an insurance that prevents the damage done in bad years from eliminating the gains made in better years (UNDP, Citation2009). This strategy would be expensive, but, if applied wisely and carefully, it can reduce the costs incurred when food insecurity is fought as it comes.

6.8. Intensification of non-form production

In a region with low agricultural potential, where climate change is expected to further reduce crop-livestock yields by up to 50% if production systems remain unchanged, intensification of on-farm production seems to be a prerequisite for reduced vulnerability to food insecurity for both people and livestock. There is need for an over haul of people’s attitude towards off-farm production activities. They must stop viewing them as activities serving to supplement agricultural yields and give them equal or more value than agriculture. This can increase households’ income from off-farm production activities and in turn lessen their vulnerability to food insecurity.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leonard Chitongo

Leonard Chitongo is a hardworking and self-motivated person and is always excited to face new challenges in his academic career. He is a permanent full time senior lecturer in the department of Rural and Urban Development at Great Zimbabwe University. He has a strong interest in carrying out research on issues that affect people’s livelihoods. To date he has published several articles on rural and urban livelihoods, housing, environmental management and public policy analysis.

References

- Aldrich, D. (2012). Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. Chicago, IL: University Chicago Press.

- Ashley, C., & Carney, D. (1999). Sustainable livelihoods: Lessons from early experience. London: Department for International Development (DFID).

- Bebbington, A. (1999). Capitals and capabilities: Aframework for analysing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty in the andes. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Bennet, T. (2001). Sustainable approach to development. A case of Ethiopia. London: Nelson and Sons.

- Bernsterin, H., Crow, B., & Johnson, H. (1991). Rural livelihoods: Cries and responses. New York: Oxford.

- Brown, R., Stephens, C., Ouma, J., Murithi, M., & Barrett, C. (2006). Livelihood strategies in the rural Kenyan highlands. African Journal of Agriculture Resource Economics, 1(1), 21–19.

- Chambers, R. and Conway, G. (1992). Sustainable rural livelihoods: Practical concepts for the 21st century, IDs discussion paper 296. Brighton. Institute of Development Studies.

- Chibi, T., Kandori, C., & Makone, B. F. (2005). Mzingwane catchment outline plan. Bulawayo: Zimbabwe National Water Authority.

- Chitongo, L. (2017) The efficacy of smallholder Tobacco farmers on rural development in Zimbabwe. PhD thesis, University of the Free State, South Africa.

- Clatworthy, J.N. (1999). Feed Resources for Small Scale Livestock Producers in Zimbabwe. Marondera Glasslands Research.

- Cooper, P., Rao, K. P. C., Singh, P., Dime, J., Traore, P. S., Rao, K., Dixit, P., Twomlow, S. (2009). Farming with current and future climate risk. Advancing a hypothesis of hope for rain-fed agriculture in the semi-arid tropics. Journal of SAT Agricultural Research in Review, 7, 1-19.

- Dar, W. D. (2009). Winning the Gamble Against the Monsoons. The Hindu. July 05. http://www.hundu.com/2009/07/05/stories/2009070555380900htm

- Ellis, F. (1998). Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. The Journal of Development Studies, 35, 1–38. doi:10.1080/00220389808422553

- FAO. (1987). Soil and water conservation in semi arid areas. Soil resources, management and conservation service division. Rome: Author.

- FAO. (2007). Animal feed impact on food security. Rome: FAO.

- Glover, J. (1959). The apparent behaviour of maize and sorghum stomata during and after drought. The Journal of Agricultural Science/Volume, 53(3), 412-416.

- Hove, L., Chakoma, C., & Nyathi, P. (2004). The potential of the tree legume leaves as supplements in diets for ruminants in Zimbabwe. Harare: Department of Research and Specialist Services.

- IFAD. (2001). Current issues in international rural development. London: ZED Books.

- IPCC. (2007). Summary for policymakers. In M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P. Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden, & C. E. Hanson (Eds.), Climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (Vols. 7–22). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2012). Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, … P. M. Midgley (Eds.), A special report of working groups I and II of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge, UK, and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- MA. (2005). Ecosystems and human well being: Dissertation synthesis. Washington, D. C.: World Resources Institute.

- Mandizvidza, M. (2006). Dynamics of agriculture. Harare: College Press.

- Mogotsi, K., Nyangito, M. M., & Nyariki, D. M. (2011). Drought management strategies among agro-pastoral communities in non-equilibrium kalahari esosystems. Environmental Research Journal, http://www.medwelljournals.com/fulltesxt/?doi=erj.2011.156.162

- Mujaya, I. M., & Mereki, B. (2006). Agriculture today. General agriculture, crop husbandry and decorative horticulture. Harare: ZPH Publishers.

- Munowenyu, E. (1999). Introduction to geographical thought and environmental studies. Module GED 101. Harare: Zimbabwe Open University.

- Nicholls, R. J., Wong, P. P., Burkett, V. R., Codignotto, J. O., Hay, J. E., McLean, R. F., … Woodroffe, C. D. (2007). Coastal systems and low-lying areas. climate change 2007: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. In M. L. Parry, O. F. Canziani, J. P. Palutikof, P. J. van der Linden, & C. E. Hanson (Eds.), Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 315–356). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Potter, R., Binns, T., Elliot, J. A., Smith, D. W. (2008). Geographies of development: An introduction to development studies. London: Pearson Education Limited.

- Ramachandran Nair, P. K., Nair, V. D., Kumar, B. M., Haile, S. G. (2009). Soil carbon sequestration in tropical agroforestry systems: A feasibility appraisal. Environmental Science and Policy, 12(8), 1099–1111. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2009.01.010

- Satge, R., Holloway, A., Mullins, D., Nchabaleng, L., Ward, P. (2002). Learning about livelihoods. Insights from Southern Africa. Oxford: Oxfam.

- Siamachira, J. (2011). Regional food security under threat. Cited in the Sunday Mail Of, 10(April), 2011.

- UNDP. (2004, February). User’s guidebook for the adaptation policy framework. United Nations Development Programme (p. 33). UK: Cambridge University Press.

- UNDP. (2009). Climate change in the African drylands: Options and opportunities for adaptation and mitigation. Nairobi: Author.

- UNDP. (2014). Sustaining human progress: Reducing vulnerabilities and building resilience (Human Development Report 2014). New York: United Nations Development Program.

- UNEP. (2009). Ecosystems management approach in UNEP’s medium-term strategy, 2010–2013. Environment for Development. http://www.unep.org.

- Vincent, B., & Thomas, T. (1961). The land husbandry act of southern rhodesia. London: Oxford University Press.

- Weichselgartner, J., & Kelman, I. (2014). Geographies of resilience: Challenges and opportunities of a descriptive concept. Progress in Human Geography. doi:10.1177/0309132513518834

- Weiss, P. (1992). Focus on geography: The human and economic environment of southern africa. Harare: College Press.

- Whingwiri, E. E., Mashingaidze, K., & Rukuni, M. (1992). Small-Scale Agriculture in Zimbabwe. Harare: Rockwood Publishers.

- Withgott, J., & Breman, S. (2011). Essential environment: The science behind the stones. London: Pearson.

- ZIMSTAT. (2012). Poverty and poverty datum line analysis in Zimbabwe 2011/12. Harare: ZIMSTAT.