Abstract

Sustainable development (SD) has become a popular catchphrase in contemporary development discourse. However, in spite of its pervasiveness and the massive popularity it has garnered over the years, the concept still seems unclear as many people continue to ask questions about its meaning and history, as well as what it entails and implies for development theory and practice. The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the discourse on SD by further explaining the paradigm and its implications for human thinking and actions in the quest for sustainable development. This is done through extensive literature review, combining aspects of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the Recursive Content Abstraction (RCA) analytical approach. The paper finds and argues that the entire issue of sustainable development centres around inter- and intragenerational equity anchored essentially on three-dimensional distinct but interconnected pillars, namely the environment, economy, and society. Decision-makers need to be constantly mindful of the relationships, complementarities, and trade-offs among these pillars and ensure responsible human behaviour and actions at the international, national, community and individual levels in order to uphold and promote the tenets of this paradigm in the interest of human development. More needs to be done by the key players—particularly the United Nations (UN), governments, private sector, and civil society organisations—in terms of policies, education and regulation on social, economic and environmental resource management to ensure that everyone is sustainable development aware, conscious, cultured and compliant.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The paper contributes to the discourse on sustainable development (SD) by clarifying further this concept and/or paradigm, and its implications for human thinking and actions in the quest for sustainable human development. This is done through literature review. The paper finds that the entire issue of SD centres around inter- and intragenerational equity anchored essentially on three distinct but interconnected pillars, namely the environment, economy, and society. Decision-makers need to be constantly mindful of the relationships, complementarities, and tension among these pillars and ensure responsible human behaviour and actions at the international, national, community and individual levels to uphold and promote the tenets of SD in the interest of human development. More needs to be done by the duty-bearers (the UN, governments, private sector and civil society) in terms of resource management, policies, education, and regulation to ensure that everyone is sustainable development aware, conscious, cultured and compliant.

1. Introduction

Sustainable Development (SD) has become a ubiquitous development paradigm—the catchphrase for international aid agencies, the jargon of development planners, the theme of conferences and academic papers, as well as the slogan of development and environmental activists (Ukaga, Maser, & Reichenbach, Citation2011). The concept seems to have attracted the broad-based attention that other development concept lack(ed), and appears poised to remain the pervasive development paradigm for a long time (Scopelliti et al., Citation2018; Shepherd et al., Citation2016). However, notwithstanding its pervasiveness and popularity, murmurs of disenchantment about the concept are rife as people continue to ask questions about its meaning or definition and what it entails as well as implies for development theory and practice, without clear answers forthcoming (Montaldo, Citation2013; Shahzalal & Hassan, Citation2019; Tolba, Citation1984). SD therefore stands the risk of becoming a cliché like appropriate technology—a fashionable and rhetoric phrase—to which everyone pays homage but nobody seems to define with precision and exactitude (Mensah & Enu-Kwesi, Citation2018; Tolba, Citation1984).

In the attempt to move beyond the sustainability rhetoric and pursue a more meaningful agenda for sustainable development, a clear definition of this concept and explanation of its key dimensions are needed (Gray, Citation2010; Mensah & Enu-Kwesi, Citation2018). This need, according to Gray (Citation2010), as cited in Giovannoni and Fabietti (Citation2014), has been advocated by both academics and practitioners in order to promote sustainable development. While it cannot be disputed that literature on SD abounds, issues regarding the concept’s definition, history, pillars, principles and the implications of these for human development, remain unclear to many people. Thus, the profusion of literature notwithstanding, further clarification of the unclear issues about SD is imperative since decision-makers need not only better data and information on the linkages among the principles and pillars of SD, but also enhanced understanding of such linkages and their implication for action in the interest of human development (Abubakar, Citation2017; Hylton, Citation2019). Succinctly put, a concise and coherent discourse on SD is needed to further illuminate the pathway and trajectory to sustainable development in order to encourage citizenship rather than spectatorship. The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to contribute to the intelligibility and articulacy of the discourse on SD by providing more concise information on its meaning, evolution, associated key concepts, dimension, the relationships among the dimensions, the principles, and their implications for global, national and individual actions in the quest for SD. This is significant as it would provide researchers, policymakers and academics, as well as development practitioners and students more information about the paradigm for policy-making, decision-making and further research.

2. Materials and method

The review was guided by aspects of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009; Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, Citation2003). Secondary data were collected through review of relevant materials including articles, theses, conference presentations and other documents available on the internet. The documents were identified through a combination of searches, using keywords and terms associated with SD. These included sustainability, development, sustainable development, economic sustainability, social sustainability, environmental sustainability and sustainable development goals. No date restrictions were imposed on the search as priority was given to the relevance of the materials in terms of their substantial contribution to the ongoing discourse on SD, irrespective of the age of the material. Attempts, however, were made to capture as much recent literature as possible in order to reflect the currency and increasing relevance of the topic.

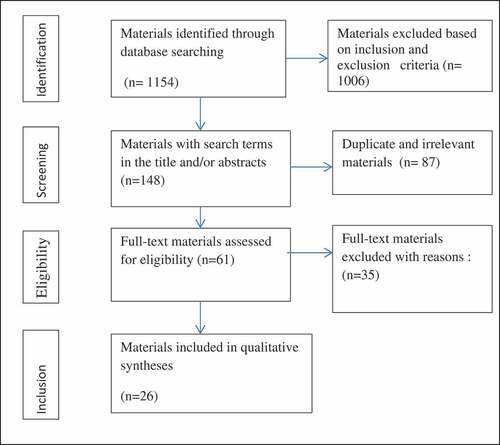

Literature that was not related to sustainability and development was excluded. However, in order to avoid the risk of missing potentially relevant literature, reference lists of selected articles were scanned for related materials to the topic under study. Information, including title and abstract, was reviewed for articles and other publications identified in the search. Selected materials meeting pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and were coherent with the topic of interest were included in the review. The general inclusion criteria were relevance, authority and currency (Browning & Rigolon, Citation2019; Wolf et al., Citation2014). Relevance had to do with how the material had contributed to the SD discourse, while authority refers to whether it had been published by a reputable source or the material had been peer-reviewed or professionally edited, Currency, on the other hand, was defined in terms of whether the material was still influential regarding the debate on SD (Browning & Rigolon, Citation2019) as evidenced, for example, by citations. The initial search criteria identified a total of 1154 references. However, applying the screening and eligibility processes stated above, 61 articles were identified for full-text retrieval, out of which 26 were identified as meeting the final inclusion criteria as shown in Figure .

The full texts were read thoroughly in order to extract the relevant information. Pieces of information gathered were analysed, combining the qualitative content analysis (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005; Mayring, Citation2000) and recursive abstraction (Leshan, Citation2012) techniques. That is, the contents were summarized under themes without coding but with notes; In this regard, the relevant information were summarised repeatedly, guided by the keywords and phrases already mentioned. The series of summarizing, which were manually done, were aimed at bringing out the basic results with regard to the viewpoints of each input data and to remove discrepancies and irrelevant data. The reasons for discarding particular aspects of each summary result were noted while each summary was being prepared in order not to forget the reasons for their exclusion. Pieces of information gathered through the summaries were synthesised, interlinked and paraphrased to make them more condensed, concise, coherent and manageable, being careful not to change the meaning of the data when combining the themes. The end result was a more concise and refined summary of the relevant literature regarding the key issues as presented below.

3. The key issues

The paper focuses on key issues relating to the concepts of development, sustainability and sustainable development. The issues include the history of SD as well as the pillars and principles of this concept. The paper also presents the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the associated debate regarding the trade-offs, complementarities, costs and benefits, as well as what can be done to achieve the “much-talked-about” SD.

3.1. The concept of development

Development, as a concept, has been associated with diverse meanings, interpretations and theories from various scholars. Development is defined as ‘an evolutionary process in which the human capacity increases in terms of initiating new structures, coping with problems, adapting to continuous change, and striving purposefully and creatively to attain new goals (Peet, Citation1999 cited in Du Pisani, Citation2006). According to Reyes (Citation2001) development is understood as a social condition within a nation, in which the needs of its population are satisfied by the rational and sustainable use of natural resources and systems. Todaro and Smith (Citation2006) also define development as a multi-dimensional process that involves major changes in social structures, attitudes, and institutions, as well as economic growth, reduction of inequality, and eradication of absolute poverty. Several theories have been put forward to explain the concept of development. They include the Modernisation, Dependency, World Systems and Globalisation Theories.

The Modernization Theory of development distinguishes between two main categories of society in the world, namely the traditional and modern societies. The theory, according to Tipps (Citation1976), argues that the traditional societies are entangled by norms, beliefs and values, which are hampering their development. Therefore, in order to progress, the traditional societies must emulate the culture of modern societies, which is characterised by accumulation of capital and industrialization which are compatible with development. In essence, this theory seeks to improve the standard of living of traditional societies through economic growth by introducing modern technology (Huntington, Citation1976). This theory is criticised for not taking into account Sen's (Citation1999) view of development regarding freedoms and self-esteem. The Dependency Theory, based on Marxist ideology, debunks the tenets of the Modernization Theory and asserts that industrialization in the developed countries rather subjects poor countries to underdevelopment as a result of the economic surplus of the poor countries being exploited by developed countries (Bodenheimer, Citation1970; Webster, Citation1984). The theory, however, fails to clarify the dependency of the less developed countries on the metropolis in terms of how the developed countries secure access to the economic surplus of the poor countries.

The World Systems Theory posits that international trade specialization and transfer of resources from the periphery (less developed countries) to the core (developed countries) stifle development in the periphery by making them rely on core countries (Petras, Citation1981). The World Systems Theory perceives the world economy as an international hierarchy of unequal relations (Reyes, Citation2001) and that the unequal relations in the exchange between the Third World and First World countries is the source of First World surplus. This contrasts with the classical Marxist Theory, which posits that the surplus results from the capital-labour relation that exists in “production” itself. (Bodenheimer, Citation1970; Reyes, Citation2001) The World System Theory has been criticised for overemphasising the world market while neglecting forces and relations of production. (Petras, Citation1981)

Similar to the World System Theory, the Globalization Theory originates from the global mechanisms of deeper integration of economic transactions among the countries (Portes, Citation1992). However, apart from the economic ties, other key elements for development interpretation as far as globalisation is concerned are the cultural links among nations (Kaplan, Citation1993; Moore, Citation1993), In this cultural orientation, one of the cardinal factors is the increasing flexibility of technology to connect people around the world (Reyes, Citation2001). Therefore, open and easy communication among nations has created grounds for cultural homogenisation, thereby creating a single global society (Waks, Citation2006). Political events no longer take local character but global character. Thus, according to Parjanadze (Citation2009), globalisation is underpinned by political, economic, technological and socio-cultural factors and orientations. Although these developments theories have their weaknesses, they have paved the way for the current global development concepts and paradigm, namely “sustainability” and “sustainable development” (SD).

3.2. Sustainability

Literally, sustainability means a capacity to maintain some entity, outcome or process over time (Basiago, Citation1999). However, in development literature, most academics, researchers and practitioners (Gray & Milne, Citation2013: Tjarve, & Zemīte, Citation2016; Mensah & Enu-Kwesi, Citation2018; Thomas, Citation2015) apply the concept to connote improving and sustaining a healthy economic, ecological and social system for human development. Stoddart (Citation2011) defines sustainability as the efficient and equitable distribution of resources intra-generationally and inter-generationally with the operation of socio-economic activities within the confines of a finite ecosystem. Ben-Eli (Citation2015), on the other hand, sees sustainability as a dynamic equilibrium in the process of interaction between the population and the carrying capacity of its environment such that the population develops to express its full potential without producing irreversible adverse effects on the carrying capacity of the environment upon which it depends. From this standpoint (Thomas, Citation2015) continues that sustainability brings into focus human activities and their ability to satisfy human needs and wants without depleting or exhausting the productive resources at their disposal. This, therefore, provokes thoughts on the manner in which people should lead their economic and social lives drawing on the available ecological resources for human development.

Hák, Janoušková, and Moldan (Citation2016) have argued that transforming global society, environment and economy to a sustainable one is one of the most uphill tasks confronting man today since it is to be done within the context of the planet’s carrying capacity. The World Bank (Citation2017) continues that this calls for innovative approaches to managing realities. In furtherance of this argument, DESA-UN (Citation2018) posits that the ultimate objective of the concept of sustainability, in essence, is to ensure appropriate alignment and equilibrium among society, economy and the environment in terms of the regenerative capacity of the planet’s life-supporting ecosystems. In the view of Gossling-Goidsmiths (Citation2018), it is this dynamic alignment and equilibrium that must be the focus of a meaningful definition of sustainability.

However, as argued by Mensah and Enu-Kwesi (Citation2018), the definition must also emphasise the notion of cross-generational equity, which is clearly an important idea but poses difficulties, since future generations’ needs are neither easy to define nor determine. Based on the foregoing, contemporary theories of sustainability seek to prioritize and integrate social, environmental and economic models in addressing human challenges in a manner that will continually be beneficial to human (Hussain, Chaudhry, & Batool, Citation2014; UNSD, Citation2018b). In this regard, economic models seek to accumulate and use natural and financial capital sustainably; environmental models basically dwell on biodiversity and ecological integrity while social models seek to improve political, cultural, religious, health and educational systems, among others, to continually ensure human dignity and wellbeing (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2012; Evers Citation2018), and for that matter, sustainable development.

3.3. Sustainable development

Sustainable development has become the buzzword in development discourse, having been associated with different definitions, meanings and interpretations. Taken literally, SD would simply mean “development that can be continued either indefinitely or for the given time period (Dernbach, Citation1998, Citation2003; Lele, Citation1991; Stoddart, Citation2011). Structurally, the concept can be seen as a phrase consisting of two words, “sustainable” and “development.” Just as each of the two words that combine to form the concept of SD, that is, “sustainable” and “development”, has been defined variously from various perspectives, the concept of SD has also been looked at from various angles, leading to a plethora of definitions of the concept. Although definitions abound with respect to SD, the most often cited definition of the concept is the one proposed by the Brundtland Commission Report (Schaefer & Crane, Citation2005). The Report defines SD as development that meets the needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meets their own needs.

Acknowledging the pervasiveness of WCED’s definition, Cerin (Citation2006) as well as Abubakar (Citation2017) argues that SD is a core concept within global development policy and agenda. It provides a mechanism through which society can interact with the environment while not risking damaging the resource for the future. Thus, it is a development paradigm as well as concept that calls for improving living standards without jeopardising the earth’s ecosystems or causing environmental challenges such as deforestation and water and air pollution that can result in problems such as climate change and extinction of species (Benaim & Raftis, Citation2008; Browning & Rigolon, Citation2019).

Looked at as an approach, SD is an approach to development which uses resources in a way that allows them (the resources) to continue to exist for others (Mohieldin, Citation2017). Evers (2017) further relates the concept to the organizing principle for meeting human development goals while at the same time sustaining the ability of natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services upon which the economy and society depend. Considered from this angle, SD aims at achieving social progress, environmental equilibrium and economic growth (Gossling-Goidsmiths, Citation2018; Zhai & Chang, Citation2019). Exploring the demands of SD, Ukaga et al. (Citation2011) emphasised the need to move away from harmful socio-economic activities and rather engage in activities with positive environmental, economic and social impacts.

It is argued that the relevance of SD deepens with the dawn of every day because the population keeps increasing but the natural resources available for the satisfaction of human needs and wants do not. Hák et al. (Citation2016) maintain that, conscious of this phenomenon, global concerns have always been expressed for judicious use of the available resources so that it will always be possible to satisfy the needs of the present generation without undermining the ability of future generations to satisfy theirs. It implies that SD is an effort at guaranteeing a balance among economic growth, environmental integrity and social well-being. This reinforces the argument that, implicit in the concept of SD is intergenerational equity, which recognises both short and the long-term implications of sustainability and SD (Dernbach, Citation1998; Stoddart, Citation2011). According to Kolk (Citation2016), this is achievable through the integration of economic, environmental, and social concerns in decision-making processes. However, it is common for people to treat sustainability and SD as analogues and synonyms but the two concepts are distinguishable. According to Diesendorf (Citation2000) sustainability is the goal or endpoint of a process called sustainable development. Gray (Citation2010) reinforces the point by arguing that, while “sustainability” refers to a state, SD refers to the process for achieving this state.

4. History of sustainable development

Although the concept of SD has gained popularity and prominence in theory, what tends to be neglected and downplayed is the history or evolution of the concept. While the evolution might seem unimportant to some people, it nonetheless could help predict the future trends and flaws and, therefore, provide useful guide now and for the future (Elkington, Citation1999). According to Pigou (Citation1920), historically, SD as a concept, derives from economics as a discipline. The discussion regarding whether the capacity of the Earth’s limited natural resources would be able to continually support the existence of the increasing human population gained prominence with the Malthusian population theory in the early 1800s (Dixon and Fallon, Citation1989; Coomer, Citation1979). As far back as 1789, Malthus postulated that human population tended to grow in a geometric progression, while subsistence could grow in only an arithmetic progression, and for that matter, population growth was likely to outstrip the capacity of the natural resources to support the needs of the increasing population (Rostow & Rostow, Citation1978). Therefore, if measures were not taken to check the rapid population growth rate, exhaustion or depletion of natural resources would occur, resulting in misery for humans (Eblen & Eblen, Citation1994). However, the import of this postulation tended to be ignored in the belief that technology could be developed to cancel such an occurrence. With time, global concerns heightened about the non-renewability of some natural resources which threaten production and long-term economic growth resulting from environmental degradation and pollution (Paxton, Citation1993). This re-awakened consciousness about the possibility of occurrence of Malthus’ postulation and raised questions about whether the path being chattered regarding development was sustainable (Kates et al., Citation2001).

Similarly, examining whether the paradigm of global economic development was “sustainable”, Meadows studied the Limits to Growth in 1972, using data on growth of population, industrial production and pollution (Basiago, Citation1999; Rostow, Citation1978). Meadows concluded that “since the world is physically finite, exponential growth of these three key variables would eventually reach the limit” (Meadows, Citation1972). However, several academicians, researchers and development practitioners (Dernbach, Citation2003; Paxton, Citation1993) argue that the concept of sustainable development received its first major international recognition in 1972 at the UN Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm. According to Daly (Citation1992) and Basiago (Citation1996), although the term was not referred to explicitly, the international community agreed to the notion—now fundamental to sustainable development—that both development and the environment hitherto addressed as separate issues, could be managed in a mutually beneficial way.

Following these developments, the World Commission on Environment and Development, chaired by Gro Harlem Brundtland of Norway, renewed the call for SD, culminating in the development of the Brundtland Report entitled “Our Common Future” in 1987 (Goodland & Daly, Citation1996). As already mentioned, the report defined SD as development that meets the needs of current generation without compromising the ability of future generation to meets their own needs. Central to the Brundtland Commission Report were two key issues: the concept of needs, in particular the essential needs of the world’s poor (to which overriding priority should be given); and the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organisation on the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs (Kates et al., Citation2001).

Jain and Islam (Citation2015) intimate that the Brundtland report engendered the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), known as the Rio Earth Summit, in 1992. The recommendations of the report formed the primary topics of debate at the UNCED. The UNCED had several key outcomes for SD articulated in the conference outcome document, namely Agenda 21 (Worster, Citation1993). It stated that SD should become a priority item on the agenda of the international community” and proceeded to recommend that national strategies be designed and developed to address economic, social and environmental aspects of sustainable development (Allen, Metternicht, & Wiedmann, Citation2018). In 2002 the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD), known as Rio+10, was held in Johannesburg to review progress in implementing the outcomes from the Rio Earth Summit. WSSD developed a plan of implementation for the actions set out in Agenda 21, known as the Johannesburg Plan, and also launched a number of multi-stakeholder partnerships for SD (Mitcham, Citation1995).

In 2012, 20 years after the first Rio Earth Summit, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD) or Rio+ 20 was held. The conference focused on two themes in the context of sustainable development: green economy and an institutional framework (Allen et al., Citation2018). A reaffirmed commitment to SD was key to the conference outcome document, ‘”The Future We Want” to such an extent that the phrase “sustainable development” appears 238 times within the 49 pages (UNSD, Citation2018a). Outcomes of Rio +20 included a process for developing new SDGs, to take effect from 2015 and to encourage focused action on SD in all sectors of global development agenda (Weitz, Carlsen, Nilsson, & Skånberg, Citation2017). Thus, in 2012, SD was identified as one of the five key priorities by the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon in the UN action agenda, highlighting the key role SD should play in international and national development policies, programmes and agenda.

5. Relationships among the environment, economy and society

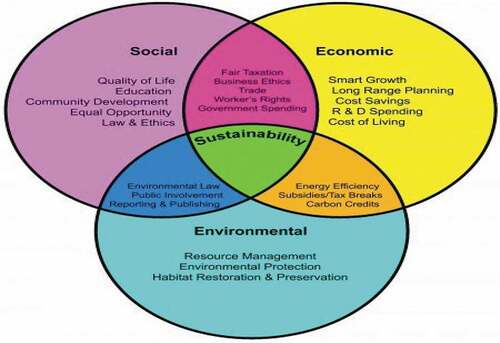

The concept of sustainability appears poised to continue to influence future discourse regarding development science. This, in the view of Porter and van der Linde (Citation1995), implies that the best choices are likely to remain those that meet the needs of society and are environmentally and economically viable, economically and socially equitable as well as socially and environmentally bearable. This leads to three interconnected spheres or domains of sustainability that describe the relationships among the environmental, economic, and social aspects of SD as captured in Figure .

Basically, it can be concluded from the figure that, nearly everything man does or plans to do on earth has implications for the environment, economy or society and for that matter the continued existence and wellbeing of the human race. Akin to this, as argued by Wanamaker (Citation2018), the spheres constitute a set of interrelated concepts which should form the basis of human decisions and actions in the quest for SD. Yang (Citation2019) supports the argument by opining that basically, the figure depicts that proper decisions on sustainable resource management will bring about sustainable growth for sustainable society. Examples of these include decisions on land use, surface water management, agricultural practices, building design and construction, energy management, education, equal opportunities as well as law-making and enforcement (Montaldo, Citation2013; Porter & van der Linde, Citation1995). The argument is that, when the concepts contained in the three spheres of sustainability are applied well to real world situations, everybody wins because natural resources are preserved, the environment is protected, the economy booms and is resilient, social life is good because there is peace and respect for human rights (DESA-UN, Citation2018; Kaivo-oja, Panula-Ontto, Vehmas, & Luukkanen, Citation2013). Kahn (Citation1995) and Basiago (Citation1999) provide a vivid illustration regarding the relationships among economic, social and environmental sustainability, arguing that the three domains must be integrated for sustainability sake. According to Khan (1995) as cited in Bassiago (Citation1999):

“If a man in a given geographical area lacks a job (economic), he is likely to be poor and disenfranchised (social); if he is poor and disenfranchised, he has an incentive to engage in practices that harm ecology, for example, by cutting down trees for firewood to cook his meals and warm his home (environmental). As his actions are aggregated with those of others in his region cutting down trees, deforestation will cause vital minerals to be lost from the soil (environmental). If vital minerals are lost from the soil, the inhabitants will be deprived of the dietary nutrients required to sustain the intellectual performance needed to learn new technologies, for example, how to operate a computer, and this will cause productivity to reduce or stagnate (economic). If productivity stagnates (economic), poor people will remain poor or poorer (social), and the cycle continues.”

The above hypothetical case illustrates the linkages among the three interconnected domains of sustainability and the need to integrate them for SD (Basiago, Citation1999). Although this example may have been oversimplified, it contextualises how the economic, social and environmental substrates of sustainability relate to one another and can foster SD (Basiago, Citation1999; Khan, 1995).

6. Pillars of sustainable development

As a visionary and forward-looking development paradigm, SD emphasises a positive transformation trajectory anchored essentially on social, economic and environmental factors. According to Taylor (Citation2016), the three main issues of sustainable development are economic growth, environmental protection and social equality. Based on this, it can be argued that the concept of SD rests, fundamentally, on three conceptual pillars. These pillars are “economic sustainability”, “social sustainability”, and ‘environmental sustainability.

6.1. Economic sustainability

Economic sustainability implies a system of production that satisfies present consumption levels without compromising future needs (Lobo, Pietriga, & Appert, Citation2015). Traditionally, economists assuming that the supply of natural resources was unlimited, placed undue emphasis on the capacity of the market to allocate resources efficiently (Du & Kang, Citation2016). They also believed that economic growth would be accompanied by the technological advancement to replenish natural resources destroyed in the production process (Cooper & Vargas, Citation2004). However, it has been realised that natural resources are not infinite; besides not all of them can be replenished or are renewable. The growing scale of the economic system has overstretched the natural resource base, prompting a rethink of the traditional economic postulations (Basiago, Citation1996, Citation1999; Du & Kang, Citation2016). This has prompted many academicians to question the feasibility of uncontrolled growth and consumption.

Economies consist of markets where transactions occur. According to Dernbach, (Citation1993), there are guiding frameworks by which transactions are evaluated and decisions about economic activities are made. Three main activities that are carried out in an economy are production, distribution and consumption but the accounting framework used to guide and evaluate the economy with regard to these activities grossly distorts values and this does not augur well for society and the environment (Cao, Citation2017). Allen and Clouth (Citation2012) echo that human life on earth is supported and maintained by utilising the limited natural resources found on the earth. Dernbach (Citation2003) had earlier argued that, due to population growth, human needs like food, clothing, housing increase, but the means and resources available in the world cannot be increased to meet the requirements forever. Furthermore, Retchless and Brewer (Citation2016) argue that, as the main concern seems to be on economic growth, important cost components like the impact of depletion and pollution, for example, are ignored while increasing demand for goods and services continues to drive markets and infringe destructive effects of the environment (UNSD, Citation2018c). Economic sustainability, therefore, requires that decisions are made in the most equitable and fiscally sound way possible, while considering the other aspects of sustainability (Zhai & Chang, Citation2019)

6.2. Social sustainability

Social sustainability encompasses notions of equity, empowerment, accessibility, participation, cultural identity and institutional stability (Daly, Citation1992). The concept implies that people matter since development is about people (Benaim & Raftis, Citation2008). Basically, social sustainability connotes a system of social organization that alleviates poverty (Littig & Grießler, Citation2005). However, in a more fundamental sense, “social sustainability” relates to the nexus between social conditions such as poverty and environmental destruction (Farazmand, Citation2016). In this regard, the theory of social sustainability’ posits that the alleviation of poverty should neither entail unwarranted environmental destruction nor economic instability. It should aim to alleviate poverty within the existing environmental and economic resource base of the society (Kumar, Raizada, & Biswas, Citation2014; Scopelliti et al., Citation2018).

In Saith’s (Citation2006) opinion, at the social level sustainability entails fostering the development of people, communities and cultures to help achieve meaningful life, drawing on proper healthcare, education gender equality, peace and stability across the globe. It is argued (Benaim & Raftis, Citation2008) that social sustainability is not easy to achieve because the social dimension seems complicated and overwhelming. Unlike the environmental and economic systems where flows and cycles are easily observable, the dynamics within the social system are highly intangible and cannot be easily modelled (Benaim & Raftis, Citation2008; Saner, Yiu, & Nguyen, Citation2019). As Everest-Phillips (Citation2014) puts it, “the definition of success within the social system is that “people are not subjected to conditions that undermine their capacity to meet their needs”

According to Kolk (Citation2016) social sustainability is not about ensuring that everyone’s needs are met. Rather, its aims at providing enabling conditions for everyone to have the capacity to realize their needs, if they so desire. Anything that impedes this capacity is considered a barrier, and needs to be addressed in order for individuals, organization or community to make progress towards social sustainability (Brodhag & Taliere, Citation2006; Pierobon, Citation2019). Understanding the nature of social dynamics and how these structures emerge from a systems perspective is of great importance to social sustainability (Lv, Citation2018). Above all, in Gray (Citation2010) and Guo’s (Citation2017) views, social sustainability also encompasses many issues such as human rights, gender equity and equality, public participation and rule of law all of which promote peace and social stability for sustainable development.

6.3. Environmental sustainability

The concept of environmental sustainability is about the natural environment and how it remains productive and resilient to support human life. Environmental sustainability relates to ecosystem integrity and carrying capacity of natural environment (Brodhag & Taliere, Citation2006). It requires that natural capital be sustainably used as a source of economic inputs and as a sink for waste (Goodland & Daly, Citation1996). The implication is that natural resources must be harvested no faster than they can be regenerated while waste must be emitted no faster than they can be assimilated by the environment (Diesendorf, Citation2000; Evers, Citation2018). This is because the earth systems have limits or boundaries within which equilibrium is maintained.

However, the quest for unbridled growth is imposing ever greater demands on the earth system and placing ever greater strain on these limits because technological advancement may fail to support exponential growth. Evidence to support concerns about the sustainability of the environment is increasing (Gilding: ICSU, Citation2017). The effects of climate change, for instance, provide a convincing argument for the need for environmental sustainability. Climate change refers to significant and long-lasting changes in the climate system caused by natural climate variability or by human activities (Coomer, Citation1979). These changes include warming of the atmosphere and oceans, diminishing ice levels, rising sea level, increasing acidification of the oceans and increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases (Du & Kang, Citation2016).

Climate change has already shown signs of affecting biodiversity. In particular, Kumar et al. (Citation2014) have observed that higher temperatures tend to affect the timing of reproduction in animal and plant species, migration patterns of animals and species distributions and population sizes. Ukaga et al. (Citation2011) have argued that while dire predictions abound, the full impacts of global warming are not known. What is clearly advisable, according to Campagnolo et al. (Citation2018) is that, for the sake of sustainability, all societies must adjust to the emerging realities with respect to managing ecosystems and natural limits to growth.

The current rate of biodiversity loss exceeds the natural rate of extinction (UNSD, Citation2018c). The boundaries of the world’s biomes are expected to change with climate change as species are expected to shift to higher latitudes and altitudes and as global vegetation cover changes (Peters & Lovejoy (Citation1992) cited in Kappelle, Van Vuuren & Baas (Citation1999). If species are not able to adjust to unfamiliar geographical distributions, their chances of survival will be reduced. It is predicted that, by the year 2080, about 20% of coastal wetlands could be lost due to sea-level rise (UNSD, Citation2018c). All of these are important issues of environmental sustainability because as already pointed out, they have implications for how the natural environment remains productively stable and resilient to support human life and development.

7. The sustainable development goals

Sustainable development relates to the principle of meeting human development goals while at the same time sustaining the ability of natural systems to provide the natural resources and ecosystem services upon which the economy and society depend (Cerin, Citation2006). While the concept of sustainable development has been relevant since time immemorial, it can be argued that the relevance deepens with the dawn of every day because the population keeps increasing but the natural resources available to humankind do not. Conscious of this phenomenon, global concerns have always been expressed for judicious use of the available resources.

The latest of such concerns translated into the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The MDGs were a sequel to the SDGs. The MDGs marked a historic global mobilisation to achieve a set of important social priorities worldwide (Breuer, Janetschek, & Malerba, Citation2019). However, in spite of the relative effectiveness of the MDGs, not all the targets of the eight goals were achieved after being rolled out for 15 years (2000–2015), hence, the introduction of the SDGs to continue with the development agenda. As part of this new development roadmap, the UN approved the 2030 Agenda (SDGs), which are a call to action to protect the planet, end poverty and guarantee the well-being of people (Taylor, Citation2016). The 17 SDGs primarily seek to achieve the following summarised objectives.

Eradicate poverty and hunger, guaranteeing a healthy life

Universalize access to basic services such as water, sanitation and sustainable energy

Support the generation of development opportunities through inclusive education and decent work

Foster innovation and resilient infrastructure, creating communities and cities able to produce and consume sustainably

Reduce inequality in the world, especially that concerning gender

Care for the environmental integrity through combatting climate change and protecting the oceans and land ecosystems

Promote collaboration between different social agents to create an environment of peace and ensure responsible consumption and production

(Hylton, Citation2019; Saner et al., Citation2019; UN, p. 2017).

According to the United Nation Communications Group (UNCG) and the Civil Society Organisation (CSO) [2017] platform on SDGs in Ghana, the SDGs are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030. Adopted by 193 countries, the SDGs came into effect in January 2016, and aim to foster economic growth, ensure social inclusion and protect the environment. The UNCG-CSO (2017) argues that the SDGs encourage a spirit of partnership among governments, private sector, research, academia and civil society organisations (CSOs)—with support of the UN. This partnership is meant to ensure that the right choices are made now to improve life, in a sustainable way, for future generations (Breuer et al., Citation2019).

Agenda 2030 has five overarching themes, known as the five Ps: people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnerships, which span across the 17 SDGs (Hylton, Citation2019; Guo, Citation2017; Zhai & Chang, Citation2019). They are intended to tackle the root causes of poverty, covering areas such as hunger, health, education, gender equality, water and sanitation, energy, economic growth, industry, innovation & infrastructure, inequalities, sustainable cities and communities, consumption & production, climate change, natural resources, and peace and justice. It can be argued from the SDGs that, sustainable development aims at achieving social progress, environmental equilibrium and economic growth.

8. The debate about the SDGs

A key feature of the SDGs is that their development objectives and targets are basically interdependent but interlinked (Tosun & Leininger, Citation2017). It is argued that the SDGs entail complementarities or synergies as well as trade-offs or tensions which have implications for global and national contexts. The complementarities imply that addressing one goal could help to address some others at the same time. For instance, addressing issues of climate change could have co-benefits for energy security, health, biodiversity, and oceans (Le Blanc, Citation2015). As opined by Fasoli (Citation2018), what needs to be noted is that, the SDGs are not standalone goals. They are interconnected, implying that achieving one goal leads to achieving another and, therefore, they should be seen as indispensable pieces in a big and complex puzzle (Kumar et al., Citation2014). In order to take advantage of the complementarities among the SDGs, Taylor (Citation2016) suggests that the various countries review the numerous targets to identify the ones most likely to be catalytic as well as those that have multi-pronged impacts, while also aiming to implement the entire agenda. This choice, according to Meurs and Quid (Citation2018), would have to be informed by country-specific priorities and resource availability. It is also worth noting that because of the complementarities of many of the goals and target areas, a single indicator may serve to measure progress across some goals and targets.

The complementarities and synergies aside, the SDGs also have trade-offs and tensions which come with difficult choices that may result in winners and losers, at least in the short term. For example, Espey (Citation2015) argues that biodiversity could be threatened if forests are cut down for purposes of increasing agricultural production for food security, while Mensah and Enu-Kwesi (Citation2018) also argue that food security could be in danger if food crops are switched to biofuel production for energy security. The implication is that, striking the delicate balance between achieving high levels of economic growth that contributes to poverty reduction and the preservation of the environment is not easy.

It is further argued that the SDGs have competing stakeholder interests attached to them. In Le Blanc’s (Citation2015) view, tackling the issue of climate change (Goal 13) is a good example of the competing interest. That is, those affected in the short term, such as fossil fuel business entities and their workers would consider themselves as “losers” if they are compelled to change, even though society as a whole will be the ultimate “winner” in the long term by avoiding the risks and impacts of climate change (Tosun & Leininger, Citation2017). Keitsch (Citation2018) continues that the trade-offs can present governance issues, in the case of complex problems within the SDGs where the interests of different stakeholders conflict. Another key challenge according to Spahn (Citation2018) is ensuring responsibility and accountability for progress towards meeting the SDGs. Several commentators, researchers and academics (Mohieldin, Citation2017; Taylor, Citation2016; Yin, Citation2016) are of the opinion that this calls for appropriate indicators and ways of monitoring and evaluating progress on the SDGs, especially at the national level (Kanie & Biermann, Citation2017). In this regard, it would be important to measure both inputs and output in order to check whether the various countries are investing what they set out to invest by way of addressing the issues, as well as tracking outcomes to check if they are actually achieving the set goals and targets (Allen et al., Citation2018; Breuer et al., Citation2019).

The UN Conference on SD, held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 2012, brought some key issues to the fore, including decent jobs, energy, sustainable cities, food security and sustainable agriculture, water, oceans and disaster readiness which call for priority attention. In the area of food and agriculture for instance, DESA (Citation2013) estimates that about 800 million people are undernourished globally, and about 220 million hectares of additional land would be needed to feed the world’s growing population by 2030. An estimated value of revenue and savings from achieving the SDGs in food and agriculture is $2.3 trillion. The top three opportunities in food systems are food waste reduction, reforestation and development of low-income food markets which are estimated to create 71 million jobs in the food markets, including 21 million across Africa and 22 million in India, where ample cropland and current low productivity pave the way for growth. (DESA, Citation2013)

According to Ritchie and Roser (Citation2018), over half of the global population already resides in urban areas and this is expected to increase further to two-thirds by 2050. This will create socio-economic costs and benefits in many sectors. Businesses can take advantage of creating healthy and liveable cities to expand their operations, thus boosting employment. According to Jaeger, Banaji, and Calnek-Sugin (Citation2017), potential profit from achieving the SDGs in cities is estimated at $3.7 trillion with approximately 166 million new jobs being in the areas of building, vehicle efficiency, affordable housing, and other urban opportunities. More than 1.5 billion additional energy consumers are anticipated by 2030 which is estimated to create about 86 million jobs and revenue of $4.3 trillion through potential payoff of circular models, renewable energy, energy efficiency and energy access. Furthermore, in Jaeger, Banaji, and Calnek-Sugin’s, (Citation2017) estimation, about $1.8 trillion revenue is potentially available from improved healthcare that takes advantage of technological innovation and other improvements in connection with the global health system, which is expected to create approximately 46 million jobs through new business opportunities in health.

Additionally, environmentally-friendly infrastructure is needed for increased economic output and productivity (Waage et al., Citation2015). Kappelle et al. (Citation1999) have pointed out that infrastructure investment in developing countries will need to increase from US$0.9 trillion to US$2.3 trillion per year by 2020. These figures include an amount of US$200–$300 billion required to ensure that infrastructure entails lower emissions and more resilience to climate change. According to UNDP (Citation2012), a relatively low estimate of the total annual climate change mitigation and adaptation costs through 2030 is $249 billion; and this addresses only one threat (global warming) to the global environmental commons. However, official development assistance (ODA) constitutes a relatively small pool of finance, at approximately $130 billion annually (UNDP Citation2012). Other costs of implementing the SDG include risks of over-exploitation and the huge financial resources needed for the various investments. These show some of the socio-economic costs and benefits of SD but metrics for assessing the impacts of SDGs remain controversial (Campagnolo et al, Citation2018).

Given the debate about the costs and benefits, the trade-offs, complementarities and complexities inherent in the SDGs, the pertinent question that arises relates to how the UN can make countries respect the SDGs. In this regard, it is advisable that the UN takes into account different national realities, capacities and levels of development and respect national policies and priorities, ensuring that they are focused on SD (Tosun & Leininger, Citation2017). Although all the SDGs apply generally to both developing and developed countries, the challenges they present may be different in different national contexts (O’Neill, Fanning, Lamb,& Steinberger, Citation2018). Therefore, UN should emphasise universality with country-specific approach to the global goals (Allen et al., Citation2018). The UN could impress upon the developed countries such as the US, UK, Japan and Canada to sustainably transform their own societies and economies while contributing to achieving SD in the developing countries. The UN should support countries by facilitating approaches that are conducive to meaningful participation, engagement and dialogue as well as capacity building for all countries. The UN could promote good governance and support inclusive education, regulation and efficient resource allocation in all countries (Collste, Pedercini, & Cornell, Citation2017). The UN could promote appropriate technology and innovation as evidence shows that the trade-off between environmental and economic outcomes, for instance, can be overcome through the use of appropriate technology. Above all, Breuer et al. (Citation2019) add that the UN should involve not only governments, but also other key stakeholders such as private sector, NGOs, and civil society in the global agenda and create feedback loops to hold all responsible entities accountable to make sure that the SDGs are actually implemented.

9. Principles of sustainable development

Achieving SD hinges on a number of principles. However, the preponderant message in regard to the principles of sustainable development (Ji, Citation2018: Mensah & EnuKwesi Citation2018) gravitates towards the economy, environment and society. Specifically, they relate, among others, to conservation of ecosystem and biodiversity, production systems, population control, human resource management, conservation of progressive culture and people’s participation (Ben-Eli, Citation2015; Molinoari et al., Citation2019).

One key principle of SD is the conservation of the ecosystem. There is the need to conserve the ecosystem and biodiversity because without these, living organism will cease to exist. The limited means and resources on the earth cannot be enough for the unlimited needs of the people. Over-exploitation of the resources has negative effects on the environment and, therefore, for development to be sustainable, exploitation of the natural resources must be within the carrying capacity of the earth (Kanie & Biermann, Citation2017). This means development activities must be carried out according to the capacity of the earth. That is why it is important, for instance, to have alternative sources of energy such as solar, instead of depending heavily on petroleum products and hydro-electricity (Molinoari et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, in order to achieve SD, there is the need for population control (Taylor, Citation2016). People eke out aliving by utilizing the limited resources on the earth. However, due to population growth, human needs like food, clothing and housing increase while the resources available in the world for meeting these needs cannot always be increased to meet the requirements. Therefore, population control and management are essential for SD.

Wang (Citation2016) opines that proper human resource management is another important principle of SD. It is the people who have to ensure that the principles are adopted and adhered to. It is people who have the responsibility to utilise and conserve the environment. It is people who have to ensure that there is peace. This makes the role of human resource in the quest for SD critical. It implies that the human knowledge and skill in caring for the environment, economy and society need to be developed (Collste et al., Citation2017). This can be done basically through education and training as well as proper healthcare services since a sound mind resides in a sound body. These elements could also assist in developing positive attitude towards nature. Education can also influence society towards conserving the environment and appreciating human values as well as acceptable production methods.

It is also argued that, the process of SD must be participatory in order to be successful and sustainable (Guo, Citation2017). The argument, which connotes the systems theory, is premised on the notion that SD cannot happen through the efforts of only one person or organisation. It is a collective responsibility which requires the participation of all people and relevant entities. SD is built on the principle of participation, which requires positive attitudes of the people so that meaningful progress can be achieved with responsibility and accountability for stability.

Additionally, SD thrives on promoting progressive social traditions, customs and political culture (Tjarve, & Zemīte, Citation2016; Lele, Citation1991). Progressive traditional and political culture must be developed and maintained or upheld and built upon to not only hold the society together but also help to value and conserve the environment for SD. In a nutshell, the underlying summative principle of SD is the systematic integration of environmental, social, and economic concerns into all aspects of decision-making across generations. The SDGs reflect a balanced agenda of economic, social and environmental goals and targets. In achieving the SDGs, countries will need to recognise and appreciate the existence of potential trade-offs and devise ways to handle them. They should also identify complementarities which can promote meaningful progress.

10. Conclusion

SD has attracted much attention in the academic, governance, planning and development intervention space. A wide range of governmental and non-governmental entities appear to have embraced it as an appropriate development paradigm. This is because most, if not all proponents and advocates of the paradigm, virtually seem to concur that the challenges confronting humankind today such as climate change, depletion of ozone layer, water scarcity, loss of vegetation, inequality, insecurity, hunger, deprivation and poverty can be addressed by adhering to the tenets and principles of SD.

The ultimate aim of SD is to achieve a balance among environmental, economic and social sustainability, thus, making these the pillars on which SD rests. While not assuming a definitive posture, sustainability of society can be said to depend on the availability of proper health systems, peace and respect for human rights, decent work, gender equality, quality education and rule of law. Sustainability of economy, on the other hand, depends on adoption of appropriate production, distribution and consumption while sustainability of the environment is driven by proper physical planning and land use as well as conservation of ecology or biodiversity. Although the literature is awash with a plethora of definitions and interpretations of SD, implicit in the pervasive viewpoints about the concept is intergenerational equity, which recognises both the short and long-term implications of sustainability in order to address the needs of both the current and future generations.

SD cannot be achieved through isolated initiatives, but rather integrated efforts at various levels, comprising social, environmental and economic aspects. The successful implementation of the SDGs will rely upon disentangling complex interactions among the goals and their targets. An integrated approach towards sustainability would require realising the potentials of its key dimensional pillars simultaneously, as well as managing the tensions, trade-offs and synergies among these dimensions. More importantly, in managing the tensions of sustainability and sustainable development, a key role has to be played by international organisations and agencies such as the UN, government of various countries, nongovernmental organisations and civil society organisations.

SD thrives on the commitment of people and so in order to translate the concept into action, public participation should be increased. All people must be aware and acknowledge that their survival and the survival of the future generation depend on responsible behaviour regarding consumption and production, environment and progressives social values. It is only by integrating the pillars can negative synergies be arrested, positive synergies fostered, and meaningful SD made to happen. It implies that economic, social and environmental “sustainability” form elements of a dynamic system. They cannot be pursued in isolation for “SD” to flourish; therefore all decisions should seek to encourage positive growth and equilibrium within the natural system. Although ensuring sustainable development is everyone’s business, global, regional, national organisations as well as governments and civil society organisations are advised and expected to show ownership, leadership and citizenship.

11. Implications

Governments of all countries should promote “smart growth” through proper land use and alignment of their economies with nature’s regeneration capacity. All countries should adopt appropriate production and consumption practices that fully align with the planet’s ecological processes. This could be done through taxation and subsidy policies which accentuate the acceptable and eliminate unacceptable outcomes. In this respect, all countries should, for example, regarding pollution, enforce the polluter-pays-principle whereby governments require environment-polluting entities to bear the costs of their pollution rather than impose those costs on others or on the environment.

Population growth should be checked through population policies backed by legal frameworks. Unless special action is taken, population growth coupled with increased resource consumption beyond what the earth can accommodate, will lead to the decline in or the collapse of the environment, economy and society. All countries need to have population policies that seek to check unbridled population growth. In this connection, the UN should have a global policy on population growth and ensure that member countries comply with the policy.

There is the need for all countries to formulate and implement social policies that foster tolerance, social cohesion and justice as cornerstones of social interactions. This can be done by enshrining universal human rights within a framework of citizenship, inclusion, equity and effective political governance.

There should be constant education on SD by the UN and the governments of all countries as well as civil society organisation to all people resident everywhere. The sensitisation programmes should be directed at ensuring that every country’s residents understand the concept and principles of sustainable development and engage in responsible environmental, economic and social behaviour as well as accountable stewardship.

Sustainable development requires the generation and application of creative ideas and innovative design and techniques. For this reason, the UN should partner with governments, private sector, development agencies and civil society organisations (CSOs) to provide strong institutional and financial support for universities and other research institutions for research into education, agriculture, physical development planning and land use, information and communication technology and health systems. All these should be backed by appropriate legal frameworks and strict enforcement of regulations to ensure that all the stakeholder comply with the SD agenda.

In prosecuting the SD agenda, UN should acknowledge and consider different national capacities and levels of development and respect national policies and priorities. The UN should also ensure that all countries emphasise universality with country-specific approach to the global goals, and encourage the developed countries to support the developing ones in the implementation of the global agenda.

12. Limitations and suggestions for further research

One major criticism that is often levelled against recursive abstraction as an analytical framework is that, the final conclusions could be distant from the underlying data, depending on how the summaries are carried out. The author, cognizant of the fact that poor initial summaries will certainly yield an inaccurate final report, took care to document, through systematic notes, the reasoning behind each summary step regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria from the intermediate summaries. However, in spite of the measures to avoid the influence of this possible methodological flaw on the outcome of this paper, the author does not arrogate to himself the virtue of perfection in the production of the paper. Furthermore, although about 98% of the materials consulted for this paper was in English, the rest were in other languages such as Chinese, which had either been translated into English or used in other articles written in English by other researchers, academicians and practitioners. The possible inherent weaknesses in these respects are acknowledged irrespective of the author’s conviction about their negligible significance, if any. Additionally, while the paper has dealt with the essential issues about SD, namely concepts, history, dimensions, principles, pillars, and the implications of these for decision-making and action, issues of the three-dimensional pillars need to be taken one by one and dealt with more intensively as they constitute the foundation of the SD agenda.

Correction

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1683296)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Justice Mensah

Justice Mensah is a Research Fellow at the Directorate of Academic Planning and Quality Assurance of the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. He holds a Doctor of Philosophy degree in Development Studies, a Master of Philosophy in Development Studies, and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Economics, all from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. His research interests include Environmental Sanitation Management, Livelihood Empowerment, Quality Assurance in Higher Education Institutions, and Sustainable Development. His most recent articles were published in the Higher Education Evaluation and Development journal, and Journal of Integrative Environmental Sciences

References

- Abubakar, I. R. (2017). Access to sanitation facilities among nigerian households: Determinants and sustainability implications. College of Architecture and Planning, University of Dammam, Saudi Arabia; Sustainability, 9(4), 547. doi:10.3390/su9040547

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York: Crown.

- Allen, C., & Clouth, S. (2012). Green economy, green growth, and low-carbon development – history, definitions and a guide to recent publications. UNDESA: A guidebook to the Green Economy. Retreived from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/GE%20Guidebook.pdf

- Allen, C., Metternicht, G., & Wiedmann, T. (2018). Prioritising SDG targets: Assessing baselines, gaps and interlinkages. Sustainability Science, 14(2), 421–438. doi: 10.1007/s11625-018-0596-81

- Basiago, A. D. (1996). The search for the sustainable city in. 20th century urban planning. The Environmentalist, 16, 135–21. doi:10.1007/BF01325104

- Basiago, A. D. (1999). Economic, social, and environmental sustainability in development theory and urban planning practice: The environmentalist. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Benaim, C. A., & Raftis, L. (2008). The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Guidance and Application: Thesis submitted for completion of Master of Strategic Leadership towards Sustainability, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karlskrona, Sweden

- Ben-Eli, M. (2015) Sustainability: Definition and five core principles a new framework the sustainability laboratory New York, NY[email protected] | www.sustainabilitylabs.

- Bodenheimer, S. (1970). Dependency and imperialism: The roots of Latin American underdevelopment (Vol. (1970), pp. 49–53). New York: NACLA.

- Breuer, A., Janetschek, H., & Malerba, D. (2019). Translating sustainable development goal (SDG)Interdependencies into policy advice: Sustainability. Bonn, Germany: MDPI German Development Institute (DIE).

- Brodhag, C., & Taliere, S. (2006). Sustainable development strategies: Tools for policy coherence. Natural Resources Forum, 30, 136–145. doi:10.1111/narf.2006.30.issue-2

- Browning, M., & Rigolon, A. (2019). School green space and its impact on academic performance: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(3), 429. doi:10.3390/ijerph16030429

- Campagnolo, L., Carraro, C., Eboli, F., Farnia, L., Parrado, R., & Pierfederici, R. (2018). The ex-ante evaluation of achieving sustainable development goals. Social Indicators Research, 136, 73–116. doi:10.1007/s11205-017-1572-x

- Cao, J. G.; Emission. (2017). Trading contract and its regulation. Journal of Chongqing University(Social Science Edition), 23, 84–90.

- Cerin, P. (2006). Bringing economic opportunity into line with environmental influence: A discussion on the coase theorem and the Porter and van der Linde hypothesis. Ecological Economics, 56, 209–225. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.01.016

- Collste, D., Pedercini, M., & Cornell, S. E. (2017). Policy coherence to achieve the SDGs: Using integrated simulation models to assess effective policies. Sustainability Science, 12, 921–931. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0457-x

- Coomer, J. (1979). Quest for a sustainable society. Oxford: Pergamon.

- Cooper, P. J., & Vargas, M. (2004). Implementing sustainable development: From global policy to local action. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Daly, H. E. (1992). U.N. conferences on environment and development: retrospect on Stockholm and prospects for Rio. Ecological Economics : the Journal of the International Society for Ecological Economics, 5, 9–14. doi:10.1016/0921-8009(92)90018-N

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs [DESA]. (2013). World Economic and Social Survey 2013 Sustainable Development Challenges E/2013/50/Rev. 1 ST/ESA/344 D

- Dernbach, J. C. (1993). The Other Ninety-Six Percent. Environmental Forum, p. 10, January/February 1993 Widener Law School Legal Studies Research Paper No. 13–20.

- Dernbach, J. C. (1998). Sustainable development as a framework for national governance. Case Western Reserve Law Review, 49(1), 1–103.

- Dernbach, J. C. (2003). Achieving sustainable development: The Centrality and multiple facets of integrated decision making. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 10, 247–285. doi:10.2979/gls.2003.10.1.247

- DESA-UN. (2018, April 4). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017. https://undesa.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html

- Diesendorf, M. (2000). Sustainability and sustainable development. In D. Dunphy, J. Benveniste, A. Griffiths, & P. Sutton (Eds.), Sustainability: The corporate challenge of the 21st century (pp. 2, 19–37). Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

- Dixon, J. A., & Fallon, L. A. (1989). The concept of sustainability: Origins, extensions, and usefulness for policy. Society & Natural Resources, 2(1), 73–84.

- Du Pisani, J. A. (2006). Sustainable development – historical roots of the concept. Environmental Sciences, 3(2), 83–96. doi:10.1080/15693430600688831

- Du, Q., & Kang, J. T. (2016). Tentative ideas on the reform of exercising state ownership of natural resources: Preliminary thoughts on establishing a state-owned natural resources supervision and administration commission. Jiangxi Social Science, 6, 160.

- Eblen, R. A., & Eblen, W. R. (1994). Encyclopedia of the environment. Houghton: Mifflin Co.

- Elkington, J., & Rowlands, I. H. (1999). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Alternatives Journal, 25(4), 42.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Espey, J. (2015). Getting started with the SDGs: Emerging questions from the first 30 days of SDG implementation in Colombia. United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network. [http://unsdsn.org/blog/news/2015/10/30/

- Everest-Phillips, M. (2014). Small, so simple? Complexity in small island developing states. Singapore: UNDP Global Centre for Public Service Excellence.

- Evers, B. A. (2018) Why adopt the Sustainable Development Goals? The case of multinationals in the Colombian coffee and extractive sector: Master Thesis Erasmus University Rotterdam

- Farazmand, A. (2016). Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance. Amsterdam: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_2760-1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313794820

- Fasoli, E. (2018). The possibilities for nongovernmental organizations promoting environmental protection to claim damages in relation to the environment in France, Italy, the Netherlands and Portugal. Review of European Community and International Environmental Law, 2017(26), 30–37.

- Giovannoni, E., & Fabietti, G. (2014). What is sustainability? A review of concepts and its applicability: Department of Business and Law, University of Siena, Siena, Italy Integrated Reporting, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-02168-3_2

- Goodland, R., & Daly, H. (1996). Environmental sustainability: Universal and non-negotiable: Ecological applications, 6(4), 1002–1017. Wiley.

- Gossling-Goidsmiths, J. (2018). Sustainable development goals and uncertainty visualization. Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation of the University of Twente in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Cartography.

- Gray, R. (2010). Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability … and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organisations and the planet. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(1), 47–62. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2009.04.006

- Guo, F. (2017). The spirit and characteristic of the general provisions of civil law. Law and Economics, 3, 5–16, 54.

- Hák, T., Janoušková, S., & Moldan, B. (2016). Sustainable development goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecological Indicators, 60(1), 565–573. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.08.003

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Huntington, S. (1976). The Change to Change: Modernization, development and politics (Vols. 30–31, pp. 45). New York: Free Press.

- Hussain, F., Chaudhry, M. N., & Batool, S. A. (2014). Assessment of key parameters in municipal solid waste management: a prerequisite for sustainability. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 21(6), 519–525. doi:10.1080/13504509.2014.971452

- Hylton, K. N. (2019). When should we prefer tort law to environmental regulation? Washburn Law Journal, 41, 515–534. Sustainability 2019, 11, 294.

- ICSU. (2017). A guide to SDG interactions: From science to implementation. D. J. Griggs, M. Nilsson, A. Stevance, & D. McCollum (Eds.), Paris: International Council for Science. (ICSU).10.24948/2017.01.

- Jaeger, J., Banaji, F., & Calnek-Sugin, T. (2017). By the numbers: How business benefits from the sustainable development goals. Washington, DC: World Resource Institute. https://www.wri.org/blog/2017/04/

- Jain, A., & Islam, M. (2015). A preliminary analysis of the impact of UN MDGs and Rio +20 on corporate social accountability practices. In D. Crowther & M. A. Islam (Eds.), Sustainability After Rio developments in corporate governance and responsibility (Vol. 8, pp. 81–102). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Ji, G. H. (2018). The evolution of the policy environment for climate change migration in Bangladesh: Competing narratives, coalitions and power. Development Policy Review. Wiley. doi: 10.1111/dpr.12384.

- Kahn, M. (1995). Concepts, definitions, and key issues in sustainable development: The outlook for the future. Proceedings of the 1995 International Sustainable Development Research Conference (pp. 2–13), Manchester, England.

- Kaivo-oja, J., Panula-Ontto, J., Vehmas, J., & Luukkanen, J. (2013). Relationships of the dimensions of sustainability as measured by the sustainable society index framework. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology. doi:10.1080/13504509.2013.860056

- Kanie, N., & Biermann, F. (2017). Governing through goals; sustainable development goals as governance innovation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Kaplan, B. (1993). Social change in the capitalist world. Beverly Hills, California: SAGE.

- Kappelle, M., Van Vuuren, M. M., & Baas, P. (1999). Effects of climate change on biodiversity: A review and identification of key research issues. Biodiversity & Conservation, 8(10), 1383–1397.

- Kates, R. W., Clark, W. C., Corell, R., Hall, J. M., Jaeger, C. C., Lowe, I., … Dickson, N. M. (2001). Sustainability science. Science, 292, 641–642. doi:10.1126/science.292.5522.1627b

- Keitsch, M. (2018). Structuring ethical interpretations of the sustainable development goals—Concepts, implications and progress. Sustainability, 10, 829. doi:10.3390/su10030829

- Kolk, A. (2016). The social responsibility of international business: From ethics and the environment to CSR and sustainable development. Journal of World Business, 51(1), 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2015.08.010

- Kumar, S., Raizada, A., & Biswas, H. (2014). Prioritising development planning in the Indian semi-arid Deccan using sustainable livelihood security index approach. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 21, 4. Taylor and Francis Group. doi:10.1080/13504509.2014.886309.

- Le Blanc, D. (2015). Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustainable Development, 23, 176–187. doi:10.1002/sd.1582

- Lele, S. M. (1991, June). Sustainable development: A critical review. World Development, 19(6), 607–662. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(91)90197-P

- Leshan, D. (2012). Strategic communication. A six step guide to using recursive abstraction applied to the qualitative analysis of interview data. London: Pangpang.

- Littig, B., & Grießler, E. (2005). Social sustainability: a catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 8, 65–79. doi:10.1504/IJSD.2005.007375

- Lobo, M.-J., Pietriga, E., & Appert, C. (2015). An evaluation of interactive map comparison techniques. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’15 (pp.3573–3582). New York, USA: ACM Press. doi:10.1145/2702123.2702130

- Lv, Z. M. (2018). Research group. The implementation outline of the “Green Principle” in civil code. China Law Sci, 1, 7–8.

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), 2–00.