?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Informal sector (IFS) activities are viable in reducing poverty among women. Yet, the full potential of IFS in reducing poverty among women may not be realised when women encounter challenges which could retard the attainment of United Nations poverty-related Sustainable Development targets. In Ghana, there is a paucity of studies regarding constraints faced by women in the IFS. The purpose of this study was to explore challenges faced by women in the IFS in Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana to inform policy direction. A sample of 356 women recruited through simple random sampling technique was involved in a cross sectional survey. The study found that 30.9% faced a myriad of challenges comprising inadequate customers, non-payment of debts, high taxes and license fees, unavailability of finance, lack of space, lack of capital equipment and difficulties with existing regulations. The study revealed a significant association between age and challenges with IFS activities. The study established a statistically significant difference between spatial location and challenges faced by women in the IFS activity. Policy recommendations that seek to counter these barriers have been offered for implementation.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Poverty and unemployment remain major problems in many developing countries. The informal sector (IFS) provides a good path to avert this challenge. In spite of its contribution to national growth and improvement in the wellbeing of those who are involved in it, the IFS presents challenges which make it difficult for its operators to reap the full benefits of the sector. In the Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana, we explore the challenges women in the IFS face. The results revealed that whiles space, limited access to credit and high taxes remain a challenge, inadequate customers is the major constraint the women encounter. We recommend that stakeholders should incorporate IFS activities into city planning while at the same time collaborating with relevant financial institutions to provide adequate financial support to women in the IFS activities.

1. Introduction

Poverty has become global agenda. Evidence from literature indicates that 86% of the global poor are found in developing economies (World Bank, Citation2018). In low income countries, 77% of the working age population earn below $2 a day (World Bank, Citation2016). In developing world, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, poverty reduction has come to represent the main goal of development interventions (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], Citation2018). Over the past decade, issues of women’s empowerment have been recognized explicitly as a key for social and economic development (CitationOrganisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2011). This is in line with poverty and gender related targets enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals one and five for Agenda 2030 which seeks to eradicate poverty in all its forms everywhere and achievement of gender equality and empowerment of all women irrespective of their location.

Women are noted to be representing 70% of the global poor (Golla, Malhortra, Nanda, & Mehra, Citation2011) hence in recent times, poverty reduction programmes have given considerable attention to vulnerable groups with women taking the centre stage because such programmes are geared towards ensuring poverty reduction, women empowerment and socio economic advancement. In Ghana for example, women’s access to factors of production such as land, labour and capital is minimal making their poverty situation worse (Abu-Salia, Osmannu, & Ahmed, Citation2015). These hindrances influence what jobs are considered appropriate for them and thus limiting their earning potential in the labour market. On average, women earn 57% income of that of men per hour in Ghana (Osei- Asibey, Citation2014). These challenges women encounter in the society put them in a more disadvantaged position to be poorer and at risk of hunger.

The subordinate status and limited access of women into the formal labour market has resulted in many seeking refuge in the informal sector (IFS) (Kishor & Gupta, Citation2009; Osei- Asibey, Citation2014). The IFS employs about two-thirds of the global active labour force and has contributed to poverty reduction (Chen, Citation2008; World Bank, Citation2009; Chant, Citation2012; UN, Citation2018). Majority of informal economy workers across the globe are women (Tinuke, Citation2012). In sub-Saharan Africa the IFS has helped to reduce extreme poverty; 84% of women non-agricultural workers are informally employed compared to 63% of male non-agricultural workers (CitationInternational Labour Organisation [ILO], 2002). This suggests that the role of women in the IFS cannot be overemphasized. In Ghana, women constitute about 90% of the labour force in the informal economy (CitationGhana Statistical Service [GSS], 2013). Women tend to be concentrated more in the informal employment, so supporting them is a key pathway to reducing women’s poverty and gender inequality.

The IFS employs about 63% of the urban labour force in developing countries (ILO, Citation2000). Female representation in the urban IFS is higher in many countries across the globe especially in developing countries (Tinuke, Citation2012). With the already constraints women face in society and barrier in the formal job market, female labour participation in the urban space is predominantly informal (Carrol, Citation2011; Ramani et al, Citation2013). The sector has been of great benefit to women in diverse ways in terms of employment, income and realisation of self-esteem (Forkuor, Peprah, & Alhassan, Citation2017).

High rates of rural-urban migration and urbanization have increased the population of major cities in Ghana and Kumasi is no exception. Its prime location (intermediate region between the north and south of the country) and its characteristic radial road network has made the city a preferred trading centre for other regions of the country and beyond (GSS, Citation2012). The influx of migrants with various background characteristics and abilities (skilled and unskilled labour) has outstripped the city’s openings in the formal job market creating a gap in the labour market. This means that the IFS is the only hope to bridge this employment gap. Location of women within the IFS is linked to their ability to fully realise their potential and opportunities which will lead the path to poverty reduction. It is therefore necessary to identify and understand the informal activities of women in order to determine how their activities have helped in reducing poverty among women in the Kumasi metropolis.

The significance of IFS activities is gradually emerging worldwide (Darbi & Knott, Citation2016), as a tool to reducing poverty (Chidoko & Makuyana, Citation2012), which has been noted as a key challenge to humanity (Sutter et al., Citation2019). Thus, IFS activities are viable in reducing poverty among women in the IFS. Yet, the full potential of IFS in reducing poverty among women may not be realised when women encounter challenges which could retard the attainment of United Nations poverty-related Sustainable Development targets. In Ghana, there are limited studies regarding constraints faced by women in the IFS. It is therefore necessary to identify and understand the characteristics of women in the IFS in order to determine the root cause of the challenges they encounter in their economic activities. It will also help to provide practical recommendations and solutions in addressing such predicaments to reduce poverty of women in the metropolis. The study is worth investigating as it contributes to the country’s effort in the path to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals one and five which seek to eradicate poverty and promote gender equality through female empowerment. Specifically, the study examines factors that pose hindrances to the informal activities of the women in the Kumasi Metropolis.

2. Theoretical perspective

Current conceptualizations of the informal economy postulate that the IFS, its operators and activities can only be better appreciated and understood if discussions are set along the path of theories and the entirety of the sector. This study draws insights on feminism theory which postulates that males and females ought to enjoy equal status politically, economically and socially (Ropers-Huilman, Citation2002). Generally, by inference, the theory states the relevance of women in the IFS as a potential pathway to poverty reduction among women (Tong, Citation2009). When the share of female labour force participation rises, it results in faster economic growth (World Bank, Citation2012). Multiple identities such as nationality, ethnic identities, social class, sexual orientations and even ideology spanning from the generation of these feminist theories, manage to influence the interpretation of the concept (Hooks, Citation2000). Delmar (Citation1986) asserts that, the term adopts a restrictive usage in terms of specific concerns and particular groups. This brings to focus three main principles that underline feminist theories and from which they originated (Ropers-Huilman, Citation2002). First of all, women are unique and have something valuable to contribute to the society (far and near). Secondly, women’s participation in the society has been passive, their potential stifled and unable to receive rewards as a result of stigmatization and oppression they face. Thirdly, feminist research should do more than critique. It is imperative for feminist theorists to pay particular attention at the micro level to capture issues and work towards social transformation. Inferring from these principles, the primary aim of feminist theory hinges on the recognition and liberation of women to empower them for the benefit of the whole society.

Oppression of women as viewed by Hardiman, Jackson, and Griffin (Citation2010) is exhibited in three forms; individually, institutional or societal/cultural. From the individual perspective, it could be from a single person to a specific social group as it is in the case of a patriarchal society. In the lens of the institutions, oppression comes in the form of rules, laws, policies and customs enacted by social organisations or institutions which tend to put one group in a more disadvantaged position but favour the other group. In this case, women are considered to be at the unfavourable side. The societal/cultural aspect of oppression emphasizes on rituals, social norms, roles, language art that provide clear indication that one social group is placed higher than the other. To this effect, Hooks (Citation2000) accentuated that the concept of feminism be viewed as a movement to curtail sexism and oppression of women. This means there is the need for global understanding and convergence in thought in addition to workable steps to reverse this social and cultural injustice against women at the global and national levels; then, trickle down to the community level. According to Ropers-Huilman (Citation2002) social transformation should be the absolute goal of feminist movement. This is based on fundamental principles that recognise the potentials and significance of women in every facet of the society’s development and wellbeing of individuals. One positive step towards this direction is empowering women to be economically efficient and independent.

The IFS is an area that has been relevant and convenient for women to gain economic empowerment and reduced poverty among women to enable them contribute to socioeconomic enhancement of themselves, their households and the society. This strongly affirms the liberal feminism traditional perspective that emphasises the capabilities of women. Their thesis espouses that “society has a false belief that women are by nature less intellectually and physically capable than men” (Tong, Citation2009). The angle this approach takes, seems to appreciate the value and potentials of women and allows them to explore opportunities in varied fields to enable them excel in all areas just like men. This is buttressed by Freeman’s (Citation2010) view as he advocates for equal citizenship of women with men. A study by World Bank (Citation2012) revealed that when the share of female labour force participation rises, it results in faster economic growth; an effort worth encouraging because it has the potential of helping developing countries in general to move out of extreme poverty (Klasen & Lamanna, Citation2009).

Women are integral part of the society, hence their value, potential and contributions should be of paramount importance at the global, national and community levels. It is further important to identify the challenges they faced in the IFS to inform policy decision. Thus, the feminist theory serves as a useful theory to investigate the challenges faced by women in the IFS in the Kumasi Metropolis.

3. Profile of the study area

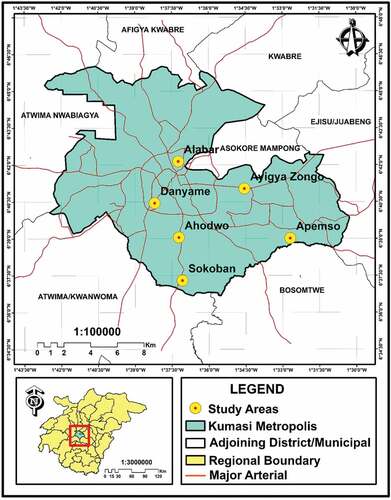

The Kumasi Metropolis is centrally located in the Ashanti Region of Ghana (see figure ). It is located between Latitude 6⁰.35ʹN and 6⁰.40ʹ S and Longitude 1⁰.30ʹ W and 1⁰.35ʹ E and elevated 250 to 300 m above sea level (GSS, Citation2014a). It is the second largest city in Ghana and the administrative capital of Ashanti Region. It is a fast-growing Metropolis with an estimated population of more than two million people and an annual growth rate of about 5.4%. It accommodates about 36.2% of the region’s population with a population density of 8,013 persons/sq.km (Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly, Citation2017). The Metropolis is about 254 square kilometers with a concentric physical structure and a centrally located commercial area. It is estimated that 48, 463ed and 60% of the Metropolis are urban, peri-urban and rural respectively, confirming the fast rate of urbanization (CitationKumasi Metropolitan Assembly [KMA], 2017). There are concentrations of economic activities in the city. The Kumasi Metropolis is noted for vibrant IFS activities by reasons of its interrelated radial road network within and outside Ghana (KMA, Citation2010). Women dominate in the service and trade-related activities. Due to this reason, the Kumasi Metropolis serves as a suitable site to explore challenges faced by women in the IFS.

4. Methodology

4.1. Study philosophy and research design

The research philosophy adopted for the study is pragmatism, which involves a dynamic research approach that is securely grounded in both qualitative and quantitative epistemologies. Pragmatism uses simply what works to achieve desired objective of the study. According to Morgan (Citation2000), pragmatism worldview looks out for what and how to research, based on the intended consequences (what is expected to be achieved). The essence of the choice of mixed method approach, was to ensure that the respondents in a study of this magnitude and intricacies are not denied their subjective views on the phenomena being studied, while the objectivity of the entire research enterprise is guaranteed. Specifically, the study employed concurrent triangulation design. The rationale for this choice was the advantage it has over the sequential model. Concurrent triangulation method results in a shorter period for data collection as both quantitative and qualitative data are gathered in the period in between each other (Creswell, Citation2009).

Research design is considered to constitute the blueprint for the collection, measurement and analysis of data (Kothari, Citation2004). In line with this, the study employed cross-sectional research design. The approach was used to evaluate challenges faced by women in the IFS in Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana.

4.2. Sampling procedure

The study applied the multi-stage sampling procedure in selecting the units of analysis. Six communities within the Kumasi Metropolis were purposively selected which influenced the sample frame. These communities were Danyame and Ahodwo (high-class residential area), Alabar and Ayigya-zongo (slums) and Apemso and Sokoban (periphery). The diverse socio-economic characteristics of the chosen locations offered the opportunity to understand different dimensions regarding challenges faced by women in the IFS in the Kumasi Metropolis. Food vending, petty trading and hawking of general goods and service providers (dressmaking and hairdressing) were of special interest to the researcher due to the high percentage of female representation in the urban areas and Kumasi for that matter. An estimated sample size of 380 women in IFS activities was determined using the formula from Miller and Brewer (Citation2003) as follows: where N= sample frame; n=sample size; ά=margin of error.

Stratified sampling was employed to categorize units of inquiry into the informal activity of researcher’s interest. Proportions for each stratum were worked out. Then, simple random sampling procedure was applied to select the respondents in each stratum for all the six communities. In addition, purposive sampling techniques were used to select 10 key informants because they had in-depth knowledge on challenges faced by IFS workers in the Kumasi metropolis.

4.3. Ethical issues

It has been established that it is the responsibility of the researcher to respect the dignity, privacy and life of the human subject (Carlson et al., Citation2004; Delamothe & Smith, Citation2004). In conducting this study, attention and care was taken on sensitivity to this fact and tried the very best not to create false expectations that the researcher cannot fulfil. The respondents were made aware that their details would be treated as confidential. Individual right to decline to participate in the study or respond to specific questions deemed very private to them were duly respected. This is because informed written and verbal consent from respondents were sought (Berg, Citation2001).

4.4. Data collection methods and instruments

The data collection instruments employed were questionnaire, interview guides and focus group discussion guides. Whereas the questionnaire was used to take quantitative data, the interview and focus group discussion guides were used to capture qualitative data. The questionnaire was used to obtain information from women in the IFS. The questionnaire focused socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, types of business ownership and challenges faced by women in the IFS. More also, to avoid low return rate and non-responses to questions usually associated with this type of data collection method (questionnaire), the authors adopted direct door stepping questionnaire administration. As a result, six field assistants who are experienced in social science field research were engaged and trained. The purpose was to enable the field assistants to be acquainted with the demand and expectation of the questionnaires administration. This approach was crucial because, it ensured that all the necessary details were captured. The questionnaire was developed in English but translated into Twi for better understanding by the participants. The questionnaire administration lasted between 40 and 45 min on the average.

Aside the questionnaire, interview guides were developed to collect qualitative data. Interview was selected as a qualitative data collection method because of its ability to produce detailed information from the perspective of the interviewee (respondent) without much restriction. The interviews offered the opportunity to obtain information that might have been omitted during the questionnaire survey. The duration of the interviews varied considerably from one interview to another due to the nature of their activity, position and function. The interviews were conducted with IFS workers and key informants who were; one official from the Business Advisory Centre, KMA revenue unit, Food and Hygiene Unit of the Environmental Departments and five financial institutions in the Kumasi metropolis and two officials from Subin and Manhyia Sub-metros. The questions on the interview basically focused on challenges faced by women in the IFS.

Apart from this, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were held with a section of the female IFS operators within the study areas to ascertain the challenges they encounter in their line of business. In all, six FGDs with six members in each group were held. Members of the focus group discussion consisted of one hairdresser, a seamstress, a hawker, a petty trader, a food vendor and a store owner. One FGD in each of the study communities was conducted to aid triangulation of responses given in the questionnaire. The intent was to validate the responses elicited earlier from the sampled women. This technique creates the opportunity to capture issues which individual respondents may have omitted or forgotten and perhaps the researcher overlooked. Both FGDs and interviews were recorded with the consent of interviewees and transcribed later to draw patterns along thematic areas. Whereas the interview lasted between 30 and 35 min, that of the FGDs lasted between 50 and 55 min on the average.

4.5. Data analysis

Quantitative data that were generated through questionnaire administration were analysed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 21). Research techniques such as chi-square and regression were employed. Qualitative data generated were analysed using thematic analysis. This approach enabled the researchers to develop main and sub-themes which reflected on the views of the respondents. The authors read and reviewed the transcripts and interview notes several times to aid in developing the themes for further analysis. The reason for using the thematic analysis was that it helped to identify, analyse and report patterns within data, and also aided in organizing and describing the data in an appropriate manner. In view of the themes developed by the authors, the normative views of the respondents were presented using quotations.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Types of business ownership

The study targeted a sample size of 380 but 356 responded to the survey. Hence, the response rate was 93% with total of 24 respondents declining to take part resulting in a non-response rate of 7%.Within the metropolis, businesses are either owned by an individual (sole proprietor), family partnership or a cooperative society. From the study, it was revealed that approximately 93% of the business ownership of the women in the IFS were operated through sole proprietorship hence operators were considered “self-employed” (see Table ). This strongly affirms the liberal feminism traditional perspective that emphasizes the capabilities of women (Ropers-Huilman, Citation2002). With such opportunity in the IFS, economic and social empowerment of women would be enhanced, appreciating the value and potentials of women and allowing them to explore opportunities in different fields of endeavour especially in the IFS activities.

Operators were involved in their economic venture for myriad reasons which illuminate the relevance of the sector. The study respondents highlighted that they were into sole proprietorship because they wanted to be their own bosses. This depicts the aspiration of women to enjoy economic and social emancipation in order to enhance and recognize their significance, worth and respect as asserted by OECD, (Citation2011) and further strengthens the feminism standpoint and its relevance to women and the society. Again, a conceivable explanation by the section of women who wish to be their own boss stresses the need and desire of the women to establish a balance between household tasks and the dream to attain some level of financial independence. Women who are sole proprietors can arrange their work schedule to balance their responsibility at home such as child nurturing and other house chores. These results confirm assertion by Tong (Citation2009) which dismisses claims by anti-feminist theorist such as Green (Citation1998) that women possess limited intellectual ability and are physically incapable of handling responsibilities beyond their distinctive domestic role. The results also emphasise the significance of the IFS work environment, which makes it possible for the women to perform such dual role effectively. The IFS is characterized by free entry and exit and extremely flexible working hours aside the limited start-up capital that is usually required to operate a business Gaddy and Ickes (Citation1998); Canagarajah and Sethuraman (Citation2001); Becker (Citation2004); Phan and Coxhead (Citation2010). With such features and flexibility, within IFS, the stress and inconveniences for working mothers are reduced. This assertion was confirmed in a qualitative data as some respondents expressed their opinions. They stated:

“Working in the informal sector is very important to me. There is nothing better than being in control of your own business or work. As a working mother, I usually reschedule my time to enable me attend to private issues without the stress of pleasing my boss and asking for permission all the time” [Petty trader (slums)—FGDs].

“I started nursing the thought of working on my own when I was fifteen years. That is why I did not see the need to continue schooling after completing JHS. Since I love to cook I decided to put my hobby into good use. Being in this job gives me the opportunity to take decisions which gives me a great sense of worth, confidence and may be maturity” [Food vendor (periphery)—FGD].

“I live with my ailing grandmother. The nature of my work offers me the flexibility to take good care of her. Before I leave the house every morning I make sure she is comfortable and return home at least once to check up on her before I finish the day’s sales. I am able to do all this because of the nature of my job” [Hawker (periphery)—FGD]

“When I was retrenched from my job as typist, I was very sad and disappointed but decided to put the money I was given into petty trading. Now, not only can I boast of a provision store, I am also a boss who has two assistants. My job also gives me the chance to babysit for my daughter who works in the formal sector” [Store owner (high class area)—interview]

The qualitative data indicate the benefits and significance of sole proprietorship to women in the IFS. Their position as owners of businesses has given them the chance to fulfil many domestic responsibilities that would otherwise have been left unattended to or been given very little attention than they deserved. The data show an interesting connection between the formal and the IFS as operators in the IFS lend helping hands to employees of the formal sector environment where regulations are stricter. For instance, an operator in the IFS, having the opportunity to take care of the grandchild, enable the baby’s mother to have the peace of mind to attend to her work in the formal sector thereby increasing her productivity. Again, it helps to reduce government burden on social welfare in terms of care for the aged and invalids. It also upholds traditional values and the extended family system that is practised in Ghana. Again it gives the operators the chance to build up their confidence and maturity because of the decisions they take for the businesses. These qualities they acquire help them to be useful in other areas of their lives and the society as a whole.

Relating the discussion to a spatial perspective, it was noted that 91.8, 91.6 and 94.2% of the respondents who reside in high class, slums and periphery respectively were intosole proprietorship. This demonstrates that sole proprietorship dominates the economic activities of respondents in the periphery indicating the desire for most people in these areas to own their businesses. This response somewhat deviates from the original perception of the author since one would have expected family partnership to be the most common business ownership type in the periphery since external family system is stronger in such areas. The study did not find any statistically significant difference between business ownership types by spatial location (P = 0.277). The implication is that one’s spatial location in terms of residence does not explain his/her ownership of a business.

5.2. General limitations of women in the IFS activity

When the respondents were asked whether they encounter challenges with respect to their present activity, approximately 31% of them responded affirmatively whereas 69% responded otherwise (see Table ). The data expose the importance of business activity to the IFS operators. It was not surprising to find that some of the respondents were faced with challenges regarding their activities because a number of studies had pointed out that women who are involved in IFS activity face challenges (Mwau, Citation2009; Cheluget, Citation2013; Mwangi & Bwisa, Citation2013; Ackah & Vuvor, Citation2011). From a spatial perspective, the study revealed that 37.7, 20 and 32.4% of the respondents from a high class residential area, slums and the periphery encounter challenges with IFS activity.

The study observed that most of the respondents from a high class residential area are more likely to encounter challenges with their activity compared with those in the slums and the periphery. In a chi-square analysis performed to estimate whether there is a statistically significant difference regarding challenges IFS women in Kumasi Metropolis face and their spatial location, the study found a statistically significant relationship between the two variables tested (P = 0.018). The suggestion is that the challenges faced by the respondents are not uniform across different geographical areas. The implication is that policy makers and metropolitan authorities in their quest to address challenges faced by women in the IFS should apply a spatial lens and that more attention should be focused on women in a high class residential area.

5.3. Specific constraints faced by women in the IFS activity

Based on the results as indicated in Table , seven constraints including lack of customers, non-payment of debts, heavy taxes and license fees, unavailability of finance, lack of space, lack of capital equipment and difficulties with existing regulations were identified and examined. These were further categorized into two based on the proportion of the responses in the quantitative data. Hence the sub-section was broadly grouped into lack of customers and other specific constraints.

Table 1. Characteristics of economic activities of informal sector operators by spatial location

Table 2. Constraints of women in the IFS activities

Table 3. Specific challenges faced by female IFS operators

5.3.1. Inadequate customers

Inadequate customers were identified in both quantitative and the qualitative study as a constraint of women in the IFS activity. In the quantitative aspect of the study, 32.9% of the respondents mentioned inadequate customers for their economic activities as a major constraint they faced. Many of the respondents considered customer base as lifeline to business growth so it is no wonder they see it as one of the biggest challenges they face in their business activities. The findings stress the connection between location and viability of economic activity as IFS operators in both the periphery and urban core desired locations that have high customer base or have the potential of attracting great proportion of customers. The results expose the mental capabilities of the women in assessing business viability and taking good business decisions. This supports the fundamental principles of the feminist theory which recognise the potentials of women towards socio-economic empowerment (Ropers-Huilman, Citation2002). Some of the respondents stated:

“Customers are very important to me due to my line of business. As a food vendor, I cannot afford to return home with my food because it is not possible to offer it on sale the next day. When the customer base is low, I cannot sell enough and this can affect my income” Being the head of household a lot of responsibilities rest on me [Food vendor (slums)-FGD].

“When I opened my salon in this area, business was very good because I was the only one in this vicinity but now there are so many of us. Unfortunately, some of my young clients visit the new and fancy shops in the area because they feel they are more trendy. This development is having a serious toll on my business” [Hair dresser, (periphery)—FGD].

“I feel I do not attract many customers because I only have few items in my shop. Sometimes when customers come around and ask of many things that are not available I can read from their faces that they are disappointed. If I could stock my shelves more, I think I could attract customers” [Store owner, (slums)—FGD].

"I thought working from home as a mother will be helpful. In both ways (domestic chores and business wise) however, it is becoming difficult for me to attract and maintain customers. This area is too quiet. Many people work in the town so they usually buy things they need when they are coming home. So the number of people who buy from me are very few. It is affecting the business capital” [Petty trader, (periphery) -FGD].

“Business is not good these days. I have to walk around for a long time before I can sell this pan of roasted corn and groundnut and walking is becoming more difficult because I am not as young as I used to be, as a result, I take many breaks which I believe influences the number of customers I meet” [Hawker, (slums) FGD].

The quotations from the respondents highlight the relationship between socio economic characteristics of female IFS workers and success of economic activity. They indicate that age for instance is a significant determinant of challenges female IFS operators encounter. It shows an inverse relationship between age and the number of hours worked in a day based on the type of economic activity one is involved in. This could also impact on the number of customers contacted in a day. For instance, a hairdresser well advanced in age might want to work for shorter hours because her strength cannot keep up with the pace of work. In this case, clients will question her availability and gradually redirect their focus to other service providers in the same category who are always available.

The agglomeration (localisation) of informal activities can have negative effects. Too many offer of services/goods at this level in comparison with the potential demand is likely to affect output of the business. This is in line with views by, Mukim (Citation2011) that most informal activities are usually found clustered within the same area which creates competition. On the other hand, the competition could be viewed with positive approach because it has the tendency to unearth hidden potentials of IFS business operators in order for them to stay relevant and remain in business. The nexus between IFS and feminism theory is re-emphasised.

Analysing inadequate customers as a challenge the women face from the spatial perspective, the study observed that 37.7% of the respondents from a high class residential area identified lack of customers as a challenge faced by women in the IFS compared to 29.5 and 30.9% in slums and the periphery respectively on the same issue. It is inferred from this data that a lot of the women from the high residential area saw lack of customers as a major challenge compared to their counterparts in the other two locations of the study (slums and the periphery). This could be due to the fact that operators in high class residential area charge higher prices for their product/services which tend to deter majority of customers from engaging their services. This is what some two respondents from the high class area stated:

“Business is not what it used to be. I thought I was doing my best but I do not understand why the customers have reduced so much. Sometimes it crosses my mind that cost might be part of the issue. But I make it a point to give customers the best service which in my opinion is a good deal. Business is not going well enough for me” [A thirty-six-year-old seamstress (high class area)—interview].

Another respondent declared:

“Time changes! Back in those days you wouldn’t come to me here by this time. I used to finish the day’s sales after lunch time which was helpful because it gave me ample time to prepare for the next day and also have some rest. I don’t know where the customers have vanished to but my observation is that there are a lot more of us here now than when I started selling here. May be the competition is high these days” [Food vendor, (high class area)—interview].

A young lady had to say in a FGD:

I am not too sure if I am facing this challenge because my business is new in this area. When my friend suggested I situate my business in this area, I did not hesitate because I thought it was a good decision and the area looked ok. But now I am beginning to have my doubt. My client capacity is too low for me but I am working hard and looking forward to brighter days ahead” [Hair dresser, (high class area)—FGD].

5.3.2. Non-payment of debts

The study revealed non-payment of debts among customers as another constraint or challenge faced by women in the IFS in the study area. However, only 4.8% of the respondents reported non-payment of debts as a constraint they face. This was relatively on the low side. It was observed that 5.3% of the respondents from the slums indicated non-payment of debts as a challenge faced by women in the IFS. Money is vital in IFS activity because it enables operators to expand their business activities and make it more attractive. When it is tied up in debts, it can have unfavourable effect on the business.

In an interview, a young lady from the slums explained:

“As a result of goodwill, I sometimes acquire some of my goods on credit so when people delay payment of debts it has serious repercussions on my image and the business as well. Some of my customers are family relations and good friends living in this same community. It is sad they like to put me in a tight corner” [Petty trader (slums) FGD].

Another respondent added:

It is really not fair when after staying up for days to work to meet deadlines, the payments are done in instalment and sometimes not completed at all. In this area, work does not come frequently so during festive season I take the opportunity to cash in but unfortunately some customers can’t be trusted” [Seamstress, (slums)—FGD].

One study participant from the Periphery indicated:

“It is interesting, sometimes you are so relieved after walking around with these items and someone asks to purchase one or two items on credit. But when we give the items on credit, they don’t want to pay. This affects our activity” [Hawker, (periphery)—FGD].

The qualitative data above provide evidence that inability or refusal of customers to pay their debts has the potential of negatively affecting the activity of IFS workers. It also highlights the effect of location and the socio economic characteristics of its residence. Customers with less economic capacity as indicated in the study, find it difficult to fulfil their part of the commercial transaction. Operators who are away from the central place have fewer customer base and informal activities are slower so they are obliged to part with their wares/goods without focusing much on the repercussion with regard to payment. Again, it shows that when the socio economic level of the client base is low, it can diminish the success rate of economic activities.

5.3.3. Taxes and licence fees

The study revealed that 4.5% of the respondents reported high taxes and licence fees as a constraint to IFS activity in the study area. Taxes are important sources of revenue to government and a great channel that enables the economy to grow whiles at the same time, it aids in the provision of socio economic welfare of citizens. There are ample evidence that the costs of formalization and the local tax burden inhibit many entrepreneurs attempting to start new small enterprises (Kuiper & van der Ree, Citation2006). However, it also has the potential of being a stumbling block to the growth of small businesses or economic activities. This is the situation many of the respondents encountered. In an interview and focus group discussions conducted with the study participants, it became clear that metropolitan authorities impose high taxes on IFS workers as evident in the quotations below:

“You can see that we don’t earn a lot from this activity, but the taxes are high for us. Sometimes you buy things on credit to make the store look nice and attractive but when the officer comes round and sees the items they send your container licence rate to a higher level. We can’t bear with that. It is affecting our activity negatively” [Store owner, (high class residential area)—interview].

“These days’ business is not so brisk and the materials needed for the running of the business are getting more expensive so when the tax issues come in, it becomes a big challenge for me” [Hair dresser, (high class residential area)—interview].

“I am not saying that it is wrong to pay tax and the metropolitan assembly does not have the right to collect any tax from us. However, the type of taxes and the amount is what I am not happy about. Can you imagine, apart from the daily toll I pay, the officials come around every three months to collect GHS 30 as licencing fee. Sometimes I feel it is blatant extortion and I am not happy at all. It is such a drain on the business” [petty trader, (slums)—FGD].

A 40-year-old woman also indicated:

In fact, when the officials from KMA office come around to talk about taxes, I feel like shutting down the business to go home and rest, especially when I consider the tiny size of my shop and what I am making out of it. Sometimes, they need to watch, listen and consider” [Store owner, (periphery)—FGD].

Another respondent added:

In my opinion, those of us who have just started should be allowed to work for a little while before bothering us with taxes. It takes money to start the business as you may know so, our purses might be empty. I feel when that happens it will help many new businesses in the metropolis” [Seamstress, (high class area)—FGD].

The study observed that, 9.8% of respondents from a high class residential area representing the highest proportion in the study areas responded that taxes and licencing fees are limitations to them. The percentage of respondents from a high class residential area that cited taxes and licence fees as a challenge to IFS activity in the study area exceeded those from the slums and the periphery and this was statistically significant (P = 0.002). The plausible reason is that many of the respondents in the high class area operated in permanent structures which attract licence and tax from the Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly (KMA) compared to those in slums and the periphery which operate in makeshift structures and homes. An interview with an official from the revenue department revealed:

“Container taxes and property rates are charged based on the prime nature of the location. Thus the higher the location’s status, the higher the tax” [Revenue officer, KMA—interview].

The implication is that business enterprises located at the nodal point or close to it are considered to have higher market size and there attracts higher taxes.

5.3.4. Unavailability of credit

Approximately 7% of the study participants reported that unavailability of finance was a constraint they were facing in their activities. The unavailability of finance revealed was in the form of limited loans received from the various banking institutions. Qualitative data obtained from respondents throw more light on the nature of financial constraints. This is what some of the respondents said:

“All they ask for is collateral such as land, house, car etc. but how can small businesses afford that. As a single mother with many mouths to feed and care for I barely have enough to take care of the family let alone save to obtain a property. But I feel when people like us are given a little push financially, we will be able to do better in our economic endeavour” [Petty trader (periphery)—FGD].

“Sometimes you may have good intentions of expanding your business but the banks will say bring this and that property as well as guarantors. This pushes some people to other money lenders who charge exorbitant interest rates. It’s a big problem” [Store owner, (slums)—FGD].

“In fact, the banks should try and help us. The other day I went to one of the traditional banks to get a loan of GHS 2000.00 but they refused without consideration because I am not a salary worker and I had not property to use as loans. The five hundred Ghana cedi loan I obtained from a money lender attracted an interest of almost 40%. That was pure extortion” [Hairdresser (periphery)—FGD].

It is sad and interesting when the micro finance companies refuse to lend money to people to start a business. I find it difficult to comprehend that policy they have. I thought they are here to help us” [Hawker, (slums)- FGD].

Another woman added:

“I like the idea and activities of the savings and loan companies but when they give you a range for the loan it makes me wonder. With the nature of my job, I feel if I am granted a loan higher than the range given me, I would be able to get a wider variety of the fish I retail. This will attract more customers and gradually improve my business” [Petty trader, (high class area)—interview].

The quotations from the respondents emphasise the status of financial capital as an important livelihood asset capable of reducing poverty and improving standard of living of the vulnerable. Again, the qualitative data exhibit frustrations some female IFS operators encounter in a bid to improve their socio economic standing. This assertion is in line with previous studies which established that a limited number of small and medium scale workers succeed in accessing funding from financial institutions, the main reason being failure to meet lending requirements, chief among them being provision of collateral security (Gangata & Matavire, Citation2013; Gichuki, Njeru, & Tirimba, Citation2014). Thus, the inability of the IFS workers to provide these collateral security hinders their ability to secure loans from banks (Vuvor & Ackah, Citation2011). Aside this, there are high loan processing fees, high rates of legal fees, high rates of interest, high cost of credit insurance and high expenses incurred in travelling in the process looking for credit which further exacerbate their problems (Mwangi & Bwisa, Citation2013).

Thus, financial institutions should consider developing credit products that would attract more IFS workers to secure loans. Women are integral part of the society and have something good to offer towards the development of themselves and their community, therefore, receiving the necessary support in this direction will enhance their capabilities. The close loop model (Ramani et al., Citation2013) highlights collaboration between women’s group or policy makers and IFS workers to identifying specific needs of female IFS workers through a two-way communication in a fair and relaxed environment. The fruits of such collaboration yield results that help to put relevant interventions in place to limit their vulnerability in the urban economic sector. This is expedient since the urban economy is purely a cash oriented and ability for the poor household survival is dependent on the IFS participation.

The study further discovered from interviews and focus group discussions with the participants that limited financial supports were received from family members and friends to expand businesses. Such social capital as identified in the livelihood assets of sustainable livelihood is beneficial. Narrowing the argument to spatial perspective, 7.4, 6.3 and 7.9% of the respondents from a high class residential area, slums and the periphery cited that unavailability of finance was a constraint to the operation of their activity. It was further noted that the percentage of the respondents from the periphery were more likely to encounter the above mentioned challenge than their respective counterparts from a high class residential area and slums. However, this disparity was not statistically significant (P = 0.898).

A 20-year-old commented:

“My primary desire was to go into sewing but my family didn’t have the means so I settled for hair dressing because I didn’t need to buy any equipment to start my training and even the business. I perch in this corner to braid people’s hair. Had it not been the financial constraints I believe I would have had a better place and more customers” [Hair dresser, (periphery)—interview].

5.3.5. Lack of space

About 6% of the respondents indicated lack of space as a constraint of women in the IFS activity in the study area. It was deduced from the results of the study that the percentage of respondents who indicated lack of space as a challenge facing women in the IFS were more in the high class area (11%) than those from the slums and the periphery. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.17).

In a focus group discussion, some of the respondents stated:

“It is rather unfortunate when you are so eager to work and yet there is no space available to you to commence your commercial activity. I couldn’t turn down the offer from my uncle to squeeze in front of his shop to sell my food. I must say business is good at this location but I cannot expand my commercial activity because of the limited available space to me. I am more or less a squatter” [food vendor, (high class area) FGD].

“I live close to the central business district so obtaining a shop or business location will be very big opportunity and helpful but that seems like an illusion because of lack of space. I am there forced to carry my goods around to sell. It makes me tired and I can carry a small quantity at a time” [Hawker, (slums) FGD].

“Space, beautification, decongestion and traffic are some of the popular words we hear from the KMA officials. I wonder if they think about us. Maybe they sometimes forget we also have families we need to take care of” [Petty trader at (slums)—FGD].

“It was such a hustle for me to when I needed a space to sell. I wanted a space close to the lorry station because that was a busy place and I am sure I could have attracted many customers but the whole area was used up and the available one was too expensivefor me to afford. So I decide to settle here but I can only say I am managing” [Petty trader, periphery—FGD].

The comments from the women underscore the prominence of location to economic activities. In line with the findings of this study, Mwau (Citation2009) in his study on planning challenges facing IFS activities in Kangemi, Nairobi cited inadequate trading spaces as challenges facing women in the IFS. This could be attributed to poor urban planning in the study area and Ghana as a whole. An interview with official from KMA revealed:

“Spaces are made available at designated areas within the metropolis but traders, particularly women prefer to work at the nodal point where they think customers are readily available” [official KMA, interview]

These issues call for the need to integrate informal activities into spatial planning in order to prevent limited number of space for IFS workers. The spatial planning department should involve all stakeholders including IFS operators so that their challenges could be captured and necessary adjustment made during the planning and implementation stages. Such action will help the informal worker to comply and easily adjust to spatial planning in the metropolis and improve the activities.

5.3.6. Lack of capital equipment

The study revealed that 5. 9% of the respondents faced lack of capital equipment as a constraint in undertaking their activity. These category of respondents were mainly in the service provision activity (hairdressers and seamstresses). When respondents were asked about the challenges they faced in their business this is what some respondents stated:

“It quite uncomfortable to see many clients wait for their turn to use the only two hair dryers I have. The sad thing is only one of them works well because both of them are used/second hand hair dryers. I feel it is impacting on the progress and income of the business” [Hairdresser (slums)-FGD].

“My biggest problem right now is the hand machine I am using. It takes a lot of effort and hard work. Often I end the day’s job with shoulder pains and it takes long to complete the work compared to the electric machine. I am trying to save for the electric one but my responsibility as head of household is making it difficult” [Seamstress, (periphery)-FGD].

“Considering the location I am operating, I need to impress the customers with my fancy looking gadgets in the area of cosmetics and beauty to attract specific client but these ones are very expensive so it is making it very difficult to achieve this dream” [Hairdresser, (high class area) interview].

Responses from the interviews and focus group conducted reveal the needs of the respondents and importance of capital equipment. It also shows the diverse socio economic backgrounds of operators in the sector. Results from the quantitative data showed that 9, 6.3 and 2.9% of the respondents respectively from a high class residential area, slums and the periphery noted lack of capital equipment as a constraint they faced regarding the operation of their activity. It was noted from the data provided by the study participants that the percentage of the respondents who indicated lack of capital equipment as a constraint faced in the IFS was higher than those from the slums and the periphery.

5.3.7. Difficulties with existing regulations

The study found that 3.9% of the respondents were faced with a constraint such as difficulties with existing regulations (such as payment of property licence, container licence and yearly medical screening for food vendor). A respondent commented:

“I am concerned about the medical certificate fee. When I started about eight years ago, it used to be GHs 8.00 then it went up to GHs12.00. Just last year, they increased it to GHs 30.00. It is a big challenge to me especially now that business is not too good because I have relocated” [Food vendor (slums)-interview].

About 4.9 and 5.8% of the respondents respectively from a high class residential area and the periphery faced this constraint. It was noted that the number of respondents from the periphery who indicated difficulties with existing regulation as a constraint faced by women in the IFS was higher compared to the other locations within the study area.

5.4. Factors associated with challenges faced by women in the IFS activity

A binary logistic regression analysis was performed to ascertain socio demographic factors (such as age, education, marital status, household and education of husband) associated with challenges faced by women in the IFS activity. The dependent variable was challenges faced in the activity. The dependent variable was measured as dichotomous and based on the question; "do you encounter any challenge with IFS activity"? The response was “yes” or “no” and was measured as ‘1’ or ‘0’ respectively.

5.4.1. Age and challenges faced by women in the IFS

The study revealed that respondents who were above 60 years were 8 times more likely to encounter challenges in the IFS compared with their counterparts who were 30 years or less and this was statistically significant (OR = 8.00, CI: 1.194–53.591, p = 0.032) (see Table ). Thus the study revealed a statistically significant association between age of the respondents and challenges faced in the IFS. The implication is that an older woman will be deficient in strength and will not be able to work for longer hours. They are more likely to find it challenging to engage in activities that are more strenuous. This will in turn affect their income and the livelihood of the family.

5.4.2. Marital status and challenges faced by women in the IFS

The study found no statistically significant difference between marital statuses and challenges faced by women in the IFS. Even though the study revealed that widowed was 3.9 times more likely to encounter challenges with their engagement in informal activity, it was not statistically significant (OR = 3.909, CI: 0.235–65.0, p = 0.342) as indicated in the Table .

Table 4. Age and challenges faced by women in the IFS

Table 6. Education and challenges by women in the IFS

Table 7. Education of husband and challenges faced in the IFS

Table 8. Family size and challenges faced by women in the IFS

Table 5. Marital status and challenges faced by women in the IFS

5.4.3. Education of the respondents and challenges faced by women in the IFS

When the education of the respondents was compared with challenges faced by women in the IFS, the results showed no statistically significant association. However, it was observed that those with JHS/JSS/Middle school levels of education were 0.461 less likely to encounter challenges with their activity compared with those with no level of education (OR = 0.461, CI: 0.100–2.123, p = 0.32) (see Table ). The data suggest that with their experience with basic education they are able to understand issues better especially ones that concern formalised institution and make better and informed decisions, which have the potential to limit their vulnerability to shocks and challenges in the urban IFS economy.

5.4.4. Education of husband and challenges faced in the IFS

There was no statistically significant difference when the education of the husband was tested to determine whether it has an impact on challenges faced by women in the IFS. However, it was observed that those women whose husbands’ education is up to JHS/JSS/Middle School, are less likely to encounter challenges in their IFS activities (OR = 0.288; CI = 0.055–1478; p = 0.136) (see Table ). The implication is that such category of women is likely to receive support from their partners because they are all found in the IFS and are relatively enlightened due to their educational backgrounds. The other possibility is that the husbands may have been in the sector for much longer period and have had the chance to learn the strategies for overcoming many of the challenges in the IFS activities. Thus, the husbands are in a better position to offer good advise that can help their businesses.

5.4.5. Family size and challenges faced by women in the IFS

When binary logistic regression analysis was performed to ascertain whether family size has influence or can predict challenges faced by women in the IFS, the results showed no statistically significant association. However, it was observed that those with 3–4 family size were less (2.520) likely to encounter challenges with their activity compared with those with larger family size (OR = 2.520; C. I = 0.480–13.224; p = 0.275) (see Table ).

5.5. Conclusion

The study explored challenges faced by women in the IFS in Kumasi Metropolis of Ghana. The study revealed that 93% of the business ownership of the women in the IFS were operated through sole proprietorship hence operators were considered 'self-employed'. The study further found that out of the 30.9% of the respondents who faced challenges with their present activities and for that matter their involvement in IFS activity, 32.9% of them face inadequate customers as major constraints. The findings accentuate the causality between location and viability of economic activity. The results vindicate the central place theory as IFS operators in both the periphery and urban core sought locations that have high customer base or have the potential of attracting great proportion of customers. The study established a statistically significant difference between spatial locations and challenges by women in the IFS activity. The study revealed a significant association between age and challenges faced by women in the IFS .

The study has several policy implications that need to be remarked. First, the findings suggest that for women in the IFS to achieve the maximum benefits from their activities, there is the need to address the challenges they face in their quest to engage in IFS activities. Such measures should consider socio-demographic profiles of women in the IFS. This is partly because socio-demographic factors such as age play a key role in the challenges faced by women in the IFS. This study is also critical in contributing towards the realisation of the United Nations poverty-related Sustainable Development Goals such as reducing poverty, eradicating hunger, improving good health and well-being, quality education and reducing gender inequality by improving economic empowerment, and enhancing the female voice in decision-making.

6. Recommendations

Based on the findings emerging from this study, we recommend that the government, management of Kumasi Metropolis and Ghana Revenue Authority should reduce taxes imposed on women in the informal activity to enable them improve their activities. The revenue authorities and management of Kumasi Metropolis should dialogue and establish tax rates which are moderate enough for all the categories of IFS businesses in the metropolis. We again recommend the incorporation of activities of IFS workers into spatial planning. To this end, the spatial planning department should involve all stakeholders including IFS operators so that their challenges could be captured and necessary adjustments made during the planning and implementation stages. Also, there is the need for institutions such as the Ministry of Gender and Social Protection, National Board for Small Industries, the office of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises as well as the Business Advisory Centre to liaise with appropriate financial institutions to increase female access to credit and savings through more accessible and affordable public and private financial mechanisms.

Conflict of Interest

We declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Veronica Peprah

Veronica Peprah holds a PhD in Geography and Rural development from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana. She obtained her MSc in Development Management in the same institution. Her research interest covers Livelihood, Empowerment, Informal Activities, Spatial Analysis, Poverty Reduction and Public Health. Her research mainly focuses on qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. The authors of this research form a team of upward researchers who collaborated to explore how urban female IFS operators recognise their performance and the constraints which impede their efforts towards poverty reduction.

References

- Abu-Salia, R., Osmannu, I. K., & Ahmed, A. (2015). Coping with the challenges of urbanization in low income areas: an analysis of the livelihood systems of slum dwellers of the Wa Municipality, Ghana. Current Urban Studies, 3(02), 105–23. doi:10.4236/cus.2015.32010

- World Bank. (2009). The world bank annual report. Washington, DC : World Bank. p. 64.

- Becker, K. (2004). The informal economy: Fact finding study. Stockholm: SIDA. (Volume and Page Number).

- Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Qualitative-Research-MethodsSocial-Sciences/dp/0205318479

- Canagarajah, S., & Sethuraman, S. V. (2001). Social protection and the informal sector in developing countries: Challenges and opportunities. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Carlson, L. E., Angen, M., Cullum, J., Goodey, E., Koopmans, J., Lamont, L., & Simpson, J. S. A. (2004). High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. British Journal of Cancer, 90(12), 2297. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887

- Carrol, E. (2011). Taxing Ghana’s informal sector: The experience of women, Christian Aid Occasional Working paper, Number 7.

- Chant, S. (2012). Feminization of poverty. The Wiley-Blackwell encyclopedia of globalization, USA. (PUBLISHERS).

- Cheluget, D. C. (2013). Effects of access to financial credit on the growth of women owned small retail enterprises in uasingishu county: A case of kapseret constituency. Kenya.

- Chen, M. A. (2008). Informality and Social Protection: Theories and Realities. IDS Bulletin, 39(2), 18–27. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2008.tb00441.x

- Chidoko, C., & Makuyana, G. (2012). The contribution of the informal sector to poverty alleviation in Zimbabwe. Developing Countries Studies, 2(9), 41–44.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Darbi, W. P. K., & Knott, P. (2016). Strategising practices in an informal economy setting: A case of strategic networking. European Management Journal, 34(4), 400–413. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2015.12.009

- Delamothe, T., & Smith, R. (2004). Open access publishing takes off. BMJ, (328), 1. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7445.934

- Delmar, R. (1986). What is Feminism? Accessed from http://www.sfu.ca/~decaste/OISE/page2/files/DelmarFeminism.pdf

- Forkuor, D., Peprah, V., & Alhassan, A. M. (2017). Assessment of the processing and sale of marine fish and its effects on the livelihood of women in Mfantseman Municipality, Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 20(3), 1329–1346. doi:10.1007/s10668-017-9943-7

- Freeman, J. (2010). Concepts in Social Sciences. Feminism. Buckingham: Open University Press Buckingham. Retrieved from https://www.mheducation.co.uk/openup/chapters/0335204155.pdfon 26/ 09/2017

- Gaddy, C., & Ickes, B. W. (1998). To restructure or not to restructure: Informal activities and enterprise behavior in transition. Washington, DC: Mimeo.

- Gangata, K., & Matavire, E. H. M. (2013). Challenges facing SMEs in accessing finance from financial institutions: The case of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. International Journal of Applied Research and Studies, 2(7), 1–10.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2012). Population and housing census, 2010 summary report of final results. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service. ww.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/storage/img/marquee-updater/Census2010_Summary_report_of_final_results.pdf

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2013). 2010 population & housing census. Regional analytical report. Greater Accra Region. Accra: Author.

- Ghana Statistical Service (2014a) 2010 population and housing census, Kumasi analytical report, Accra: GSS.

- Gichuki, J. A. W., Njeru, A., & Tirimba, O. I. (2014). Challenges facing micro and small enterprises in accessing credit facilities in Kangemi Harambee market in Nairobi City County, Kenya. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 4(12), 1–25.

- Golla, A., Malhortra, A., Nanda, P., & Mehra, R., (2011), Understanding and measuring women’s economic empowerment: Definition, framework and indicators. International Center for Research on Women (ICRW). Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://www.icrw.org/pdf_download/1659/download/34839c01dffefeaedd9799c26ebb2ad9

- Green, E. (1998). “Women doing friendship”: An analysis of women’s leisure as a site of identity construction, empowerment and resistance. Leisure Studies, 17(3), 171–85.

- Hardiman, R., Jackson, B. W., & Griffin, P. (2010). Conceptual foundations. In B. Adams, H. Castaneda, Peters, & Zúniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 26–35). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hooks, B. (2000). Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics. Cambridge, MA: South End Press. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Feminism-Everybody-Passionate-bell-hooks/…/0896086283on28/09/2017

- International Labour Office. (2000). Resolution concerning statistics of employment in the informal sector, adopted by the Fifteenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (January 1993). In Current International Recommendations on Labour Statistics, 2000 Edition; International Labour Office, Geneva

- International Labour Organisation. (2002). Decent work and the informal economy: A fair globalization. International Labour Conference: 90th Session, Geneva: International Labour Organization

- Kishor, S., & Gupta, K. (2009). Gender equality and women's empowerment in India. National Family Health Survey (Nfhs-3), (India), 2005-06.

- Klasen, S., & Lamanna, F. (2009). The impact of gender inequality in education and employment on economic growth: New evidence for a panel of countries. Feminist Economics, 15(3), 91–132.

- Kothari, C. R. (2004). Research methodology: Methods and techniques. New Delhi: New Age International Limited.

- Kuiper, M., & van der Ree, K. (2006). Growing out of poverty: Urban job creation and the millennium development goals. Global Urban Development Magazine, 2(1), 1–20.

- Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly (2010). Ghana statistical service. Annual Progress Report. Kumasi

- Kumasi Metropolitan Assembly. (2017). Metropolitan medium-term development plan (2014-2017); Ghana shared growth and development Agenda (GSGDAII). Accra: Ministry of Local Government.

- Miller, R. L., & Brewer, J. D. (2003). A-Z of social research-dictionary of key social science. London: Sage Publications.

- Morgan, A. (2000). What is narrative therapy? (pp. 116). Adelaide: Dulwich Centre Publications.

- Mukim, M. (2011). Does exporting increase productivity? Evidence from India. Manuscript, London school of economics (pp. 1–37).

- Mwangi, H. W., & Bwisa, H. (2013). The effects of entrepreneurial marketing practices on the growth of hair salons: A case study of hair salons in Kiambu Township. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(5), 467.

- Mwau, C. B. (2009). Planning challenges facing informal sector activities in Kangemi, Nairobi (Bachelor’s Thesis), University of Nairobi.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2011). Women’s economic empowerment. Issues paper. Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/dac/gender-development/47561694.pdfon 25/ 10/2017

- Osei- Asibey, E. (2014). Inequalities country report-Ghana. In Pan-African Conference on inequalities in the context of structural transformation, Accra, Ghana.

- Phan, D., & Coxhead, I. (2010). Inter-provincial migration and inequality during vietnam’s transition. Journal of Development Economics, 91, 100–112. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco

- Ramani, S. V., Ajay, T., Tamas, M., Sutapa, C., & Veena, R., (2013). Women entrepreneurs in the informal economy: Is formalization the only solution for business sustainability?. UNU-MERIT Working Paper 2013-018

- Ropers-Huilman, R. (2002). Feminism in the academy: Overview. In A. M. M. Aleman & K. A. Renn (Eds.), Women in higher education: An encyclopedia (pp. 109–118). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- Sutter, C., Bruton, G. D., & Chen, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(1), 197–214.

- Tinuke, M. F. (2012). Women and the informal sector in Nigeria: Implications for development. British Journal of Art and Social Sciences, 4(1), 1.

- Tong, R. (2009). Feminist thought. A more comprehensive introduction. Philadelphia, PA: Westview Press.

- United Nations. (2018). Economic development. New York, USA: Author.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2018). Full and productive employment and decent work: Dialogues at the economic and social council. New York, NY: United Nations publications.

- Ackah, J. & Vuvor, S. (2011). The challenges faced by small & medium enterprises (SMEs) in obtaining credit in Ghana. [Master’s thesis], Blekinge Tekniska Högskola, Blekindge, Sweden.

- Word Bank. (2018). Understanding poverty. The World Bank, Poverty Overview. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview

- World Bank. (2012). World development report: Gender equality and development.

- World Bank (2016). World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends. Washington, DC: World Bank.