Abstract

Over the past years, tourism participation has grown from being a luxury to a basic need that every human should enjoy. In developed countries, various mechanisms have been implemented to help local people to actively participate in tourism first as domestic tourists and later as international tourists. In developing countries, domestic tourism has been overlooked leading to it being underdeveloped and under-researched. Using qualitative methodology where in-depth interviews were used to collect data from 45 conveniently selected domestic tourists and tourism suppliers the study sought to analyse Zimbabwe’s domestic tourists travel trends. Study findings revealed that the travel trends were characterised by preference for particular destinations, destinations connectivity, activities, travel times, travel parties and specific spending patterns. It was concluded that Zimbabweans are active domestic tourists though they participate mainly as informal travellers whose travel trends are not tracked and accounted for in formal tourism documentation.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Domestic tourists are an integral component of a nation’s tourism market the world over. However, in developing countries, domestic tourism is overlooked in favour of international tourism which is highly volatile, unpredictable and unreliable. Thus, understanding domestic tourists travel trends will allow tourism suppliers to appreciate the magnitude of domestic tourism and its potential contribution to the tourism industry. Hard facts will be produced that planners and developers will exploit to effectively prepare the tourism industry. The study notes how domestic tourists are travelling and would want to travel presenting authorities with evidence on what they need to work on in order to boost domestic tourism in the country. The study also presented challenges that need to be addressed if domestic tourism in Zimbabwe is to match international standards in value and volume contribution to the tourism industry.

1. Background

Over the years, tourism participation has grown from being a luxury enjoyed by the rich to a right that everyone even the poor should enjoy (McCabe & Diekmann, Citation2015, p. 194). As a result, the value and volume of tourism has increased over the years throughout the world though variations still exist between different geographical regions (Demunter & Dimitrakopoulou, Citation2011, p. 3; Eijgelaar, Peeters, & Piket, Citation2008, p. 4).

Globally domestic tourism is high contributing an average of 75% to the global tourism market (Demunter & Dimitrakopoulou, Citation2011; Ghimire, Citation2013; Yap & Allen, Citation2011). Domestic tourism range from a few moments taken by local people to enjoy what is available within their local community contributing to what Urry and Larsen (Citation2011) referred to as the tourist gaze concept. They can also be daylong trips that are known as excursions (Gallarza, Del Chiappa, & Arteaga, Citation2018; Nagai & Kashiwagi, Citation2018). Other domestic tourists take short-term trips of 1 to 3 days whilst others take long domestic trips of at least 4 days travelling varying distances giving meaning to the variation that Canavan (Citation2012) termed micro and macro-domestic tourism. In essence domestic tourism therefore borders around residents of a particular area partaking in tourism within their area.

Demunter and Dimitrakopoulou (Citation2011) noted; world renowned tourism destination countries such as France, Greece, Italy and Spain had high domestic tourism participation. On the contrary countries such as Belgium, Bulgaria and Luxembourg had less than 5% of its population taking domestic trips. Seemingly then, size of the country and nature of attractions available within it are the major deciding factors in taking domestic trips. In addition to size social status, income, activity availability and access are also critical in influencing domestic tourism participation.

Whilst domestic tourism in developed countries is well documented and accounted for, in developing countries nothing much is known about it (Ndlovu, Nyakunu, & Heath, Citation2011, p. 82). However, in the developing countries there is an emerging new middle class with more disposable income that is enthusiastic about travelling for leisure (Dadvar-Khani, Citation2012; Mariki, Hassan, Maganga, Modest, & Salehe, Citation2011; Mazimhaka, Citation2006; Ndlovu et al., Citation2011) making it necessary to know and invest more in domestic tourism. In Africa, countries such as South Africa, Kenya, Rwanda, Nigeria and Tanzania have made strides to account for their domestic tourism (Mariki et al., Citation2011; Mazimhaka, Citation2007; Rogerson, Citation2015).

1.1. Views on domestic tourism in Zimbabwe

Tourism research in Zimbabwe is still in its infancy with the few studies available focusing on branding, tourism challenges, tourism development; government role in tourism development, tourism marketing and policy effects on tourism.

Mutana and Zinyemba (Citation2013) while researching on rebranding of Zimbabwean tourism product and its packaging noted that Zimbabwe is not ready to rely on domestic tourism. Their main argument being that most Zimbabweans are low-income earners that cannot economically support tourism in Zimbabwe. Whilst the economic value of domestic tourism remains critical one does not need a lot of money to be a domestic tourist (Rogerson & Lisa, Citation2005). It is equally important to note that domestic tourists despite being low spenders are critical for the discovery and eventual development of destinations (Ateljevic & Doorne, Citation2004; Crawford & Sternberg, Citation2015). In this conclusion, the study does not give any details as to how much Zimbabweans are earning and how much they must earn for them to be of value to tourism. At the same time, there seems to be deliberate omission of the informal domestic tourism market and its impact on the tourism industry.

Whilst highlighting Zimbabwean tourism woes between 2001 and 2011, Mkono (Citation2012) noted that African governments including Zimbabwe’s are struggling to stimulate domestic tourism. He argues that the little resources available are channelled towards addressing HIV problems, rehabilitating infrastructure and eradicating poverty. In this viewpoint paper, the author gives the impression that government is the sole stakeholder with ability to influence domestic travel. However, evidence from UK and Russia suggest other stakeholders like workers unions and non-governmental organisations of being instrumental in domestic tourism development (McCabe, Citation2009). This paper being a viewpoint lacks real reasons on the ground as to why the Government is failing to support domestic tourism if at all it is failing.

Chibaya (Citation2013, p. 90), after interviewing three regional managers at Zimbabwe’s destination management organisation (Zimbabwe Tourism Authority) argues that Zimbabwe is struggling to increase domestic tourism as local people have lower disposable income for them to visit local leisure facilities, the economy is negatively affecting domestic tourism, there is poor marketing of tourism to local people and awareness and synergies with private sector to provide special packages for domestic tourists has not yielded the required results. While the study unearthed critical driving forces in the development of domestic tourism in Zimbabwe, the sample size used is too small and made up of employees of the Destination Management Organisation who seem determined to protect their work than give objective views on critical tourism issues. Inclusion of other stakeholders would have triangulated the findings to validate the conclusion made. For example, Kabote et al. (Citation2013, p. 35) found that with dollarisation local people are now able to participate in domestic tourism. These findings contradict Chibaya (Citation2013)’s findings emphasising the need for a balanced study.

In their work on tourism development strategies in Zimbabwe, Muzapu and Sibanda (Citation2016) underscored the role the government can play in destination development. Among a foray of strategies, the development and management of domestic tourism through press reports on local attractions and familiarisation tours by role models were given. However, the funding for such programmes which has been blamed for failure of most governments’ programmes is not discussed and the success of such programmes is not indicated as well.

Despite there being little known information about domestic tourism in Zimbabwe, domestic tourism remains vital as it brings many advantages. As such it is important for any country that wishes to take its domestic tourism to higher level to understand its trends.

2. Statement of the problem

Domestic tourism has been overlooked in some developing nations leading to it being underdeveloped and under-researched (see Arrington, Citation2010; Chiutsi, Mukoroverwa, Karigambe, & Mudzengi, Citation2011; Dadvar-Khani, Citation2012; Manwa, Citation2007; Mazimhaka, Citation2007; Moseley, Sturgis, & Wheeler, Citation2007). This is the case despite strong arguments that domestic tourism drives the nature and structure of a country’s tourism industry (Hudson & Ritchie, Citation2002; Manono & Rotich, Citation2013; Ritchie & Crouch, Citation1993).

Neglecting domestic tourism makes it very difficult for governments and other interested organisations to come up with consistent policies for sustainable development as local people are a key stakeholder for the tourism industry (Angelevska-Najdeska & Rakicevik, Citation2012; Eijgelaar et al., Citation2008; Page, Essex, & Causevic, Citation2014). Seemingly, sustainable tourism development may not be fully realised unless it is driven by a vibrant domestic tourism. This study therefore seeks to analyse Zimbabwe’s domestic tourists travel trends.

3. Methodology

This study followed a qualitative inquiry in order to address the objective of the study. Purposive and convenience sampling approaches were followed in identifying study participants. Data were collected in Harare and Bulawayo as these are the two biggest cities where most Zimbabweans converge for various public and private businesses. This approach follows a similar study done in Turkey (see Sirakaya-Turk, Ingram, & Harrill, Citation2008). Data were also collected in Zimbabwe’s prime tourism destination, Victoria Falls. In-depth interviews were held with 25 domestic tourists and 20 tourism suppliers following a set interview guide. The interviews lasted between 30 min and 1 h 20 min. Primary data from interviews were complimented with data from unplanned observations. Data collected were analysed thematically with the aid of Nvivo 11 where charts, tables, figures, pictures and verbatim quotes were used for data presentation.

4. Results and discussion

This study sought out to analyse Zimbabwe’s domestic tourists travel trends. The phrase travel trend is used herein to refer to tendencies exhibited by domestic tourists in choosing where to travel for leisure in the country. A variety of travel trends characterised domestic tourism in Zimbabwe. These included a preference for particular destinations, destination connectivity systems, activities, travel times, travel parties and specific spending patterns.

4.1. Destination preference

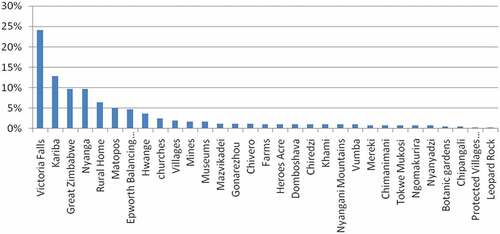

Interviews with selected domestic tourists and tourism suppliers revealed that Zimbabweans preferred to visit mainly 31 destinations in the country. Figure shows the destinations as ranked by domestic tourists and tourism suppliers according to popularity expressed as a percentage of the total number of times each destination was mentioned during the interviews.

Preferred destinations were picked during discussions with interviewees talking about places they visited, places they wanted to visit, destinations they wanted to revisit and those they recommended and would recommend to friends, relatives and acquaintances seeking knowledge about Zimbabwe’s destinations. The top 10 destinations were Victoria Falls, Kariba, Great Zimbabwe, Rural homes, Matopos, Epworth Balancing Rocks, Hwange, Religious congregations, Villages, Mines and Museums.

From Figure , it seems established and well-developed destinations that were popular with international visitors to Zimbabwe were also the preferred destinations for domestic tourists. By doing so, Zimbabweans were exhibiting similar tastes as domestic tourists elsewhere where popular destinations are the ones preferred much (see Rule et al., Citation2003). The major reasons of wanting to visit the already popular places seemed to be summed up by the views of two respondents captured below:

I would love to visit Kariba and Victoria falls because I have heard about the beautiful falls. I want to see for myself. A friend gave me a book on places you can visit for a holiday. Even some of my friends have been to these places and have been telling me stories of how nice these places are.

Would want to visit Nyanga, because I have heard there are Nyangani Mountains so I would want to see them for myself.

The behaviour of wanting to follow the beaten path in tourism is consistent with the symbolic interaction theory (Colton, Citation1987). Interaction theory argues that when interacting people have a tendency of making efforts to keep abreast with fashion or what is trending with those they mix or socialise with. In essence, most domestic tourists wanted to experience life at the most talked about destinations in the country. This trait also seemed to emphasise the fact that local people are not satisfied by just hearing or reading about destinations. They had a strong urge to experience the destinations for themselves.

Having visited popular destinations in one’s country seemed to enhance one’s self-esteem as contained in the following domestic tourists’ observations.

At one time Zimbabweans will visit South Africa and are asked about places in Zimbabwe, and they can’t answer. It is embarrassing to be told about your own country by a foreigner.

Touring local attractions is important to me and my family because everyone should know their country in detail to avoid embarrassing situations like when visiting other countries like USA and coming across books or people talking about things in your country, you should be able to comment positively and from an informed point of view.

When a foreigner comes to Zimbabwe and seeks information from someone knowledgeable about their country they will be provided with a lot of information that would make them want to explore the country themselves visiting many attractions.

Apart from the generally established and known destinations, noteworthy in the top 10 and a surprise was `rural home’ as a destination in fifth position. These rural homes are not holiday homes as is the case in developed countries where people buy homes wholly or as timeshares in resort areas to retreat to during holidays (see Barnett, Citation2007). In the local context, these are areas where one grew up, most of the relatives reside there, strong life history with that place and normally is considered one’s permanent residence. Zimbabweans have always been seen to love to connect with their friends and relatives most of whom are based in these rural areas (See Dodo, Citation2015).

The respondents also cited a number of destinations that were usually left out of the `radar’ when marketing and promoting tourism destinations in Zimbabwe such as mines, farms and newly developed destinations like Tokwe Mukosi dam. In choosing these destinations domestic tourists considered a number of factors in their travel decisions, such as distance from home or usual place of residence, activities on offer at the destination, destination unfamiliarity and destination prices.

4.1.1. Distance from home

When choosing their destinations domestic tourists gave preference to those destinations closer to their residential areas than distant ones. Fifteen out of 25 domestic tourists interviewed shared this view with their justification seemingly summed by one tourist who said:

I would rather travel to destinations nearer home that are easier to travel to and use less amount of money for fuel.

This statement was a reflection of the harsh economic environment in which people were living in then. It was also a reflection of limited resource availability for tourism purposes. The household income distribution theory seems to shed light on this situation by positing that there are many competing expenses in the home that needs to be covered, with eventual expenditure subject to whether it is the woman or man in control of the household budget (Thomas, Citation1993). The habit of visiting destinations closer to one’s home also lend credit to the `distance decay concept’ (Lew & McKercher, Citation2006; McKercher, Citation2008) which argues that distance is a significant domestic tourism development component. Destinations closer home are visited often than distant destinations as travel logistics becomes complex with an increase in distance from home.

Domestic tourists to destinations closer home are usually left out of the tourists’ taxonomy as they are regarded as excursionists. However, Urry and Larsen (Citation2011)’s tourist gaze concept acknowledges these travellers as tourists arguing that they contribute to the tourism industry through activities, food and other tourism services required by day visitors with the exception of accommodation over and above the tourism benefits accruing to the tourists themselves and host communities.

4.1.2. Activities on offer

Domestic tourists preferred destinations that offered a wide variety of activities than those with a few. As shown in Figure , Victoria Falls and Kariba were the most preferred destinations. These offered a variety of activities that provided a visitor with an opportunity to engage in for some time whilst at one destination. Respondent views on activities seemed to be summed by one who said:

We do not prefer travelling to places such as Chinhoyi Caves and museums because there is not much more to do other than sightseeing and photographing.

Thus, variety in activity offered becomes critical in destination selection especially among people who travel together as families, friends and/or any other grouping. They desire to be different despite being bound by common group demands (Duval, Citation2006).

4.1.3. Destination unfamiliarity

Some domestic tourists also preferred visiting new, unexplored and unique destinations that were not yet mass tourist destinations. No one was sure of what they would encounter at such destinations. This is a typical domestic tourist trait as domestic tourists are known for discovering and promoting new attractions (See Crawford & Sternberg, Citation2015). Examples were Protected Villages (Keeps) that were erected by the then Rhodesian government in 1977 during the liberation war as a counter insurgency strategy (See Mavhunga, Citation2014). Respondents felt it was important to visit such places as the relics of colonial Zimbabwe, reminding people of what the nation went through to gain its independence from Britain, the colonial power. For the young generation, it provides a rallying point for appreciating the history of their country and what their parents had to endure during the war of independence. Whilst the bulk of the relics of the Keeps are gone, the few remaining are a good starting point to sharing rich stories on the war of independence and the environment that local people had to endure during that time. The following statement summed up the need for local people to visit Keeps:

We should take our children to Keeps where the white minority government used to lock us up for days without visiting fields or herding cattle. We saw people being shot and killed whilst crowded in one place without anything to do.

These views present Keeps as Thana tourism sites where death, suffering and grief were common memories (see Collins-Kreiner, Citation2016). However, Thana tourism sites are not common with mass tourism as they tend to invoke bad memories and strong emotions.

Related to tours to Keeps as part of Thana tourism was mine tourism. Mines were not very popular with local people but offered unique experiences. Tourists to these sites were fascinated by the way miners go in and out of mines, the mining process, sad memories of mine accidents, heroic survival and evacuation and deaths as a result of mine collapse and inhaling dangerous gases whilst underground (see Wang et al., Citation2016). For example, the Kandamana Memorial Site established in commemoration of 427 miners who died after an underground explosion on the 6th of June 1972 at Hwange Colliery Number 2 mine shaft.

4.1.4. Destination pricing

Domestic tourists exhibited a trait consistent with other tourists elsewhere where destination choice is based on best price–quality ratio (see Butnaru, Citation2017). More often they went for the lowest possible prices in all segments of the tourism value chain from transport, accommodation through food, services, shopping and tourism activities. Notable destinations mentioned on price–quality ratio included Cleveland Dam, Mukuvisi woodlands, Epworth balancing rocks and Lake Chivero. Entry fees to these areas were very minimal, tourists were allowed to bring own food and drinks, easily accessible by road using both private and public transport at the same time offering a variety of activities for the tourists making touring to such places fall within reach of most domestic tourists.

For overnight visits, tourists were budgeting for entry fees, activities, accommodation, food and transport among others. Both tourism suppliers and domestic tourists seemed to agree on that prices in Zimbabwe were on the high side. This sentiment was aptly summarised by one tourism promoter who said:

We are pricing ourselves out of the business. I think to entice domestic tourists we should work on the law of numbers. There is more to benefit by charging $20 per night and get lots of people coming on a regular basis than charging $100 and get 4 customers per night once in a while. I don’t know the economics we are using. The food is also expensive.

Whilst the figures were hypothetical, the difference between what was and what was expected to be tells a story of how much destinations in Zimbabwe were charging. The promoter’s views were in tandem with those of some domestic tourists as reflected in one of the prospective tourists’ travel plan:

We leave Harare early in the morning maybe between 2am and 3am, get to Kariba around 6 am, have a picnic breakfast to avoid going into these expensive hotels.

Noteworthy, is that for many domestic tourists it was expensive to sleep and eat in hotels in Zimbabwe. As such staying and eating in a hotel was an option for the rich and those on business trips, sponsored by their organisations.

Other forms of accommodation considered as an alternative to sleeping in expensive hotels when holidaying was sleeping with relatives living near the target holiday resort. Hence, combining formal tourism through uptake of activities and informal tourism through staying at a relative’s place creating a hybrid form of tourism that is neither formal nor informal (see Gladstone, Citation2005).

4.2. Destination connectivity system

Destination connectivity here in refers to means by which domestic tourists find their way to, within and from destinations. There were eight means that domestic tourists used that constituted destination connectivity system. As a system, there were times when more than one connectivity means was used to make the trip complete. Figure gives the eight in order of preference.

4.2.1. Own cars

The use of own car emerged as the most common destination connectivity mode used by domestic tourists. This could be attributed to the increasing car ownership as Zimbabweans imported second-hand cars from developed countries like Japan and United Kingdom (Dube, Citation2014).

Domestic tourists had various opinions on the use of own cars. One respondent whilst talking about the accessibility of some attractions had the following to say about access to Matopo Hills (one of the local attractions south of Bulawayo city):

If I want to visit Matopo right now it’s not easy to find a bus and drop somewhere then hike to the attractions. Without own car getting to Matopo is a nightmare.

4.2.2. Taxis

Taxis were used within the destinations to carry tourists around. Tourists were being ferried from terminal points like airports, bus terminus and rail stations to accommodation facilities and places where activities were taking place. Along the way, taxi drivers acted as tour guides as they took time to explain and show tourists around destinations, for example, in Victoria Falls.

In so doing taxi drivers played a positive role in the development of domestic tourism in Zimbabwe. However, not all taxi drivers were contributing positively to domestic tourism with others being accused of overcharging tourists. Some taxi drivers charged for instance $10 for a distance of less than 2 km.

Taxi drivers were taking advantage of people’s lack of knowledge of the area and fear associated with walking in an unfamiliar place. However, such taxi driver behaviours was not unique to Zimbabwe as was found out by Ahn and Ahmed (Citation1994) in South Korea who also established that tourists were generally not happy with being overcharged by taxi drivers.

4.2.3. Bus

There were buses that serviced routes linking tourist destinations with the outside world. They were commonly referred to as chicken buses or non-express buses as they had to stop every now and again to pick and drop passengers along the way (Buenger, Citation2014). These were available on almost all roads in Zimbabwe. These buses were not designated for the tourism industry, but provided a key service and usually at a lower price as their target market was not tourists but the general travelling public. As such, they were mostly used by backpackers (see Höckert, Citation2014) as they did not offer frills. One respondent who once visited Great Zimbabwe said: “We used public transport (bus) to go to Masvingo (Great Zimbabwe) and it was cheap”.

As such chicken buses were popular with lower-income domestic tourists. However, the buses did not offer the convenience that came with using own car or hired buses as they tended to drop people off at bus terminuses which were far from the attractions and accommodation facilities.

Despite the use of chicken buses being common in Zimbabwe, their use by domestic tourists were still low and restricted to destinations where bus terminuses were close to hotels and attractions and also destinations where taxis were easily available like Victoria Falls and Kariba. Chicken buses were rarely used at places like Nyanga, Matopos, Hwange and other parks where one had to go through dangerous terrain to reach accommodation providers or at least offices from which guides could be obtained.

Besides the chicken buses being used as tourism transport by default the buses were at times hired as transport for group tours. Schools and churches, among others, hired buses to carry people on group tours. One tourism service provider noted that:

School visits mainly towards end of school terms are very common, our guides cannot rest as there are bus loads and bus loads. Some are school buses whilst others are hired chicken buses.

There was also the issue of lack of luxury buses specifically meant for tourists. One tour operator raised a concern when he said “There is no luxury bus that links Bulawayo with Victoria Falls”.

Another tourist agreed and bemoaned the lack of luxury buses to key destinations in Zimbabwe,

There is no bus that goes to Kariba that people can just jump into and go to Kariba to see and come back.

As tourism-specific mode of transport, these buses offered unique-specific services that were ideal for a Zimbabwean domestic tourist who had the desire to travel but had limited resources as suggested by one respondent:

If only we had a bus that says we are not going to sleep in Kariba. We leave Harare early in the morning maybe 2-3 am get to Kariba around 6 am have a picnic breakfast without going into these expensive hotels. The Bus takes us to crocodile farm and others, by the end of the day leave around 8 pm to Harare and in the morning you are safe at home.

These luxury buses were required to service tourists offering express services to destinations then taking tourists for tours to specific attractions within the destination. Having convenient or reliable timetable would enable domestic tourists to take weekend holidays. This would promote short-term domestic tourism lasting up to two nights. These findings were consistent with findings in India and Bangladesh (see Ferdaush & Faisal, Citation2014; Shinde & Rizello, Citation2014) where weekend domestic tourism had risen due to the massive use of buses.

Lastly, there were buses owned and operated by touring companies. These were a special class that were usually used as part of a tour package that involved transportation, accommodation, food and activities. For the duration of the tour, the driver and his crew became part of the tour offering such essential services like interpretation, confirming bookings, transferring tourists among others.

4.2.4. Train

Rail transport was mentioned as a preferred destination connectivity mode of transport for domestic tourists in Zimbabwe. One respondent gave a comparative analysis on the use of private cars against the use of trains:

With USD$200.00 in your pocket driving from Bulawayo to and from Harare will take away almost USD$120.00 yet with a train it could be about us$10.00 and you enjoy the view and nature whilst relaxed being ferried to your destination. See the animals and admire them.

The comparison by the tourist revealed some important aspects for the tourism industry. Domestic tourists believed the cost of travelling should be reasonable and affordable. Trains offer travellers an opportunity to relax and enjoy the scenery from start to finish.

The use of rail as tourism mode of transport was ideal in Zimbabwe where the trains were slow and enabled people to relax and enjoy as diesel and steam locomotives were being used (See Mbohwa, Citation2008). They were ideal for use during long holidays when people had sufficient time to spend travelling. Unfortunately, depreciation and poor maintenance made rail transport in Zimbabwe unreliable forcing people to abandon it in favour of road transport as an alternative (Mbohwa, Citation2008).

Whilst in developing countries rail was for the leisurely traveller, in developed countries trains were being used for weekend travel as they had become very fast and reliable leaving people with little time to enjoy the scenery along the way but to quickly reach their destination and spend time at the destination (see Moyano, Coronado, & Garmendia, Citation2016).

In Victoria Falls there was a newly introduced tram that was taking tourists on a leisurely tour from town to Victoria Falls Bridge. The tram serves as both an attraction on its own offering tourists’ joy rides and as a mode of transport that links the town and the bridge. See Figure .

4.2.5. Air

The use of air transport was mentioned by some travel promoters who noted that it was common among business travellers that were sponsored by their employers. Unfortunately, air transport was only used to connect Harare to Bulawayo and Harare-Bulawayo to Victoria Falls routes. One tourism promoter noted that:

Domestic flights in Zimbabwe are only limited to Victoria Falls with two airlines servicing the route.

Another Bulawayo-based operator bemoaned the lack of air transport to Victoria Falls when he said “there is only one flight per week between Bulawayo and Victoria Falls”.

Whilst there were a few flights to Victoria Falls, there was virtually no air transport available to all other destinations in the country. Thus, despite tourists wanting to use this transport mode, its non-availability forced them to look for alternatives with the majority using cars and buses.

4.2.6. Hired cars

Hired cars were a common transport mode within destinations. These were usually hired by families with the capacity and preferred to travel together to and within destinations. As one tourism promoter noted: “They hire minibuses for group family tours”.

Other tourists that used hired cars were those who could afford to leave their cars back home and fly into the destination. Two tourism promoters made the following observations:

“Fly in customers mostly hire cars to use within the destination”

“Those that fly in usually hire cars and use them for the duration of their stay reflecting different social backgrounds of the tourists”.

Ostensibly the tourism promoters believed that social status had a bearing on the kind of transport that one tourist used compared to the next. The use of air transport was being associated with well to do people who could afford to fly and hire cars.

Those fly in tourists who were not that rich did not hire cars within destinations; instead, they used cars from “transfer companies” to move them around the destinations during their stay.

Other tourists’ who flew into destinations, used public transport or rail transport and also hired cars within the destination. These hired cars from friends and relatives residing within the destinations as pointed out by one respondent:

Others have relatives in Victoria Falls where they get cars from without paying anything and then fuel them and use them during their stay.

4.2.7. Water transport

Water transport took the form of cruises, ferries and boats. Cruises were common in Victoria Falls and Kariba as attractions though they were used as a means of transport at times.

Ferries were commonly used by travellers keen to link two points. Of note were ferries and houseboats that plied the Kariba- Binga—Mulibisi route. Tourists enjoyed the tour along the length of the Kariba Dam upstream or downstream. Along the way, they had the opportunity to see animals, birds, fish and also an opportunity to engage in activities such as swimming, village tours and safari tours. The ferries were in demand as they enabled tourists to save on time, fuel, wear and tear of cars and possibly more than 1000 km if one had to drive to link Kariba and Victoria Falls.

Ferries and houseboats were not recommended by tourism promoters as they did not have regular schedules. Their movements were dependent on supply and demand of the tourists who required the service. The ferries were also considered expensive, charging between USD$65.00 and USD $120.00.

4.3. Preferred activities

Different tourists loved to engage in different activities. In order to satisfy the diverse tastes and preferences of different travellers and their motivations for travel, destinations needed to offer many activities. The ones on demand from domestic tourists were sporting activities that included volleyball, handball, horse riding and canoeing. These were popular with business people mainly as they sought team building activities to reinforce organisational cultures.

On the other hand, destinations like Hwange, Victoria Falls and Matopos that offered nature-based activities like nature walks, game viewing, scenic walks and photographic safaris were common with families. Seemingly families felt these activities offered them an opportunity to bond as they shared similar experiences at the same time.

However, high adrenaline activities such as bungee, rafting, lion walks and cage dives were popular with groups of friends especially the youths. The generational theory sheds lights on youths preferences by talking about recurring cycles of age cohorts that display identifiable patterns of behaviour (Strauss & Howe, Citation1991). The behaviour difference can be attributed to high energy levels and desire to explore new things amongst young generations. One travel promoter said:

Of late we have seen an increase in the number of young adults taking up activities like bungee jumping, white water rafting, zip line and gorge swing.

Such findings on Zimbabwe’s travellers particularly young adults supported earlier work by Sharma, Sehrawat, and Chauhan (Citation2014) and Bogari, Crowther, and Marr (Citation2003) who also noted an increase in the uptake of high adrenaline activities by young people in India and Saudi Arabia, respectively.

Other destinations such as Great Zimbabwe were also popular despite not having much to offer in terms of physical activities. However, the rich history behind the architectural work and the cultural value associated with the stone wall were important in attracting tourists eager to learn. As such the resort was popular with educational tourists ranging from primary school children seeking to understand history and culture to tertiary students in areas like archaeology in search of answers to age old questions around the attraction’s construction amongst others.

Subject to the hype generated by the main attraction at a destination, most of the destinations with single activity were not very popular with the general public but rather were a target for specific groups of people with a special interest in the area. These destinations included museums and art galleries that were common with artists and historians, whilst Chinhoyi Caves, Ngomakurira and Domboshava were popular with those into sightseeing and photographic tourism. Lastly, special places like botanic gardens attracted special interest people with a passion for botany.

Hunting was an activity that was practised by few as noted by one safari operator:

My Zimbabwean clients are very minimal, dominated by the white Zimbabweans and a few black Zimbabweans especially those with some military background.

4.4. Travelling times

Travelling times were the actual periods during the week, month or year when people travelled for tourism purposes. Zimbabweans showed different travelling times subject to the type of people that made the travelling party.

Families comprising of couples only did not have specifically identifiable travelling time. Rather, they were travelling almost throughout the year with increases noted at destinations during special events as people congregated for the event.

Families seemed to have their travelling times restricted by the availability of free time for the children. As such, they tended to travel during weekends for short holidays when kids were not at school. They also travelled during school holidays and public holidays. One tourist observed that:

… favourable travel time is Christmas holidays you go with family to celebrate and have some bit of fun.

In similar view, a tourism supplier said

Some rural people come together as families, churches especially during public holidays, groups of 10 family members- a brother come from South Africa say lets go out and they come here.

As for the working class who hardly had any time to travel as they worked for at least five days a week, they tended to travel during festive season and public holidays when companies and government departments are shut.

Business tourists travelled almost throughout the year consistently with a slight boom towards the end of the year. The surge was attributed to annual retreats by organisations to strategize for the following year.

I have been to Victoria Falls on business trips, contacting clients and having vital strategic meetings.

4.5. Travel parties

Travel parties were the identifiable groupings of people travelling together for tourism purposes. The study findings revealed that travel parties comprised families, friends, workmates, church mates, class or school mates and solo travellers.

4.5.1. Families

Families took various shapes and sizes. There were couples with honeymooners being the most common. Older couples (retired empty nesters) were also participating in domestic tourism.

Some people nowadays want to wed in tourist destinations and have their pictures taken at these attractions.

Another promoter weighed in

We have old couples that come here on their anniversaries just to enjoy themselves.

Besides couples, there were family groupings. These were usually young to middle-aged couples whose children were still dependent upon them.

Some families had grandparents, young adults and grandchildren making three or four generations travelling together on a holiday. This was common with families where a child is based in the diaspora and they come usually during the festive seasons they take their parents and children for holidays.

Some people based in the diaspora would also engage their siblings and their families and together went for a holiday making a big family group of up to 15 people. These were distinctive with their use of minibuses that accommodated large groups of people. Some used three to five cars and would travel in convoy formation as a family.

4.5.2. Friends

Groups of friends made up of old friends now scattered all over the country and beyond were coming together for holidays within Zimbabwe. These were of almost the same age range and same sex (male or female). The group sizes varied between four and eight. They were conspicuous by their use of a single car as a group, drinking and eating habits. As one such tourist explained:

We visited Matopos and Victoria Falls as a group of old friends (8) using a private car having fun all the way

Some take advantage of local attractions and visit them to show off such attractions to their visitors as and when they get friends who resides outside the community.

As a local place it is convenient so we take our visitors there. We go as friends and families using public transport.

Other groups of friends were made of family friends who decided to travel in order to help one another grow socially, spiritually and psychologically. One tourist who once had such a trip remembered:

In Nyanga in 1998 we went with a family friend, couple who were having problems. After a week in Nyanga we managed to have their problems resolved in that relaxing environment. It benefits socially to go on holiday

4.5.3. Workmates

Workmates were usually sponsored by their employer to go on a leisure holiday or business trip. They showed formal characteristics where there was too much mutual respect mainly built around work relations and positions in organisations. As observed by one tourist

We do farm visits with work colleagues as part of weekend tourism. Others have farms and others don’t. Because of diversity in knowledge we share knowledge and experiences.

Those workmates on business trips were identifiable by their routines which included closed-door meetings, team building activities and uptake of activities based more on group decision than individual decision.

4.5.4. Church groups

Churches were having retreats as congregations, special groups like pastors’ fellowship, men’s fellowship, women’s fellowship and youth fellowship among others. While holding the function at a tourist destination, they stayed in hotels, ate in fine restaurants, took time to visit attractions within the destination, undertook some activities and also bought some artefacts to take home as reminders for the time at the destination.

There were also religious congregations at the founder’s places of origin such as congregations at John Marange’s home area in Marange area by Marange Apostolic Sect members and retreats by Zion Christian Church members at Defe Dopota area where the founder Samuel Mutendi originated from.

Some tourists also mentioned participating in popular prayer nights by Pentecostal churches in Zimbabwe. Two notable examples were identified. These were Judgement Night hosted by the United Family Interdenominational Church founder Emmanuel Makandiwa in Harare around August annually. The other popular then was the Night of Turnaround hosted by Prophetic Healing and Deliverance Ministries founder Walter Magaya around November annually.

These gatherings were primarily for spiritual upliftment. The guests to these functions used hotels, hired cars, buses and also had an opportunity to explore attractions within the vicinity.

4.6. Expenditure patterns

Expenditure patterns were the ways in which domestic tourists spent their money as tourists from the time they left home to the time they got back home from a tour. Whilst on holiday, domestic tourists exhibited some expenditure patterns worth noting.

Domestic tourists were keen to buy artefacts associated with a particular destination. For example, tourists to Kariba bought mainly artefacts associated with the mythical Nyaminyami spirit and those to Victoria Falls preferred items that symbolised the falls. One tourist explained that “we buy curios for us to remember the destination with” and there is no better reminder than an artefact that resembles the actual key attraction to a destination.

However, not all artefacts were popular with domestic tourists as noted by one supplier:

…in terms of souvenirs it is still very low (purchase), the feeling is that we know these things, we can make these things

Seemingly domestic tourists wanted reminders and were particular about what to buy and what not to buy. They made sure they got something that really resembled the destination rather than something too general that would want them to explain to someone later when they show off their curios back home to friends and relatives who had never been to the destination.

5. Conclusion

The study sought to analyse Zimbabwe’s domestic tourists travel trends. The study revealed the following six major trends exhibited by Zimbabwe’s domestic tourists. Specifically, domestic tourists have preferred destinations characterised by established destinations and little known destinations as they sought to satisfy their travelling needs. Secondly, they used a destination connectivity system made up of own cars, taxis, walking, buses, trains, airplanes and cruises. Thirdly, they preferred destinations that offered many activities such as sports, high adrenaline activities like skywalk, and relaxing activities like nature walks. Fourthly they preferred travelling during school holidays and public holidays. Fifthly they travelled as families, friends, workmates or church groups. Lastly, domestic tourists were generally low spenders with money spend mainly on artefacts that symbolises the destination visited. The study recommends that potential investors and policy makers explore further and develop the areas exhibited by the domestic tourists to realise major economic benefits from domestic tourism. Meaningful exploitation of domestic tourism by maximising on the trends exhibited would increase tourism benefits to the tourism industry, country and the touring individuals.

Cover Page

Source: Author

Image: Protected Village No. 10, Rhodesia- This protected village stands alone in the Chiweshe Trust Land North of Salisbury. The village, a sea of thatched roof huts, is ringed with barbed wire and security lights. On the hill above the huts is the tower, where security forces keep watch and fight off night guerrilla attacks. Source gettyimages.co.uk

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Forbes Kabote

Forbes Kabote is a Dr in Tourism Management and Lecturer in the Department of Travel, Leisure and Recreation - School of Hospitality and Tourism at Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe. His research interests are in domestic tourism, sustainable tourism development, dark tourism, tourism economics and destination management. This research was part of a broader study on domestic tourism and sustainable tourism development that sought to explore mechanisms for optimising the exploitation of domestic tourism for sustainable tourism development in Zimbabwe. The work was supervised by Dr Patrick Walter Mamimine and Professor Zororo Muranda both of Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe.

References

- Ahn, J.-Y., & Ahmed, Z. U. (1994). South Korea’s: Emerging tourism industry. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 35(2), 84–18.

- Angelevska-Najdeska, K., & Rakicevik, G. (2012). Planning of sustainable tourism development. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 44, 210–220. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.022

- Arrington, A. L. (2010). Competing for tourists at Victoria Falls: A historical consideration of the effects of government involvement. Development Southern Africa, 27(5), 773–787. doi:10.1080/0376835X.2010.522838

- Ateljevic, I., & Doorne, S. (2004). Cultural circuits of tourism: Commodities, place, and re-consumption. A Companion to Tourism, 291–302.

- Barnett, R. (2007). Central and Eastern Europe: Real estate development within the second and holiday home markets. Journal of Retail & Leisure Property, 6(2), 137–142. doi:10.1057/palgrave.rlp.5100052

- Bogari, N. B., Crowther, G., & Marr, N. (2003). Motivation for domestic tourism: A case study of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Tourism Analysis, 8(2), 137–141. doi:10.3727/108354203774076625

- Buenger, A. (2014). My experience at GARBO cooperative: Auto-ethnography about fair trade and rural tourism in Peñas Blancas, Nicaragua. The Ohio State University.

- Butnaru, G. I. (2017). Quality of services–key factor for the image creation of tourist destination. EuroEconomica, 36, 1.

- Canavan. (2012). The extent and role of domestic tourism in a small Island. Journal of Travel Research, 52(3), 340–352. doi:10.1177/0047287512467700

- Chibaya, T. (2013). From ‘Zimbabwe Africa’s Paradise to Zimbabwe A world of wonders’: Benefits and challenges of rebranding Zimbabwe as a tourist destination. Developing Country Studies, 13(5), 84–91.

- Chiutsi, S., Mukoroverwa, M., Karigambe, P., & Mudzengi, B. K. (2011). The theory and practice of ecotourism in Southern Africa. Journal of Hospitality Management and Tourism, 2(2), 14–21.

- Collins-Kreiner, N. (2016). Dark tourism as/is pilgrimage. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(12), 1185–1189. doi:10.1080/13683500.2015.1078299

- Colton, C. W. (1987). Leisure, recreation, tourism: A symbolic interactionism view. Annals of Tourism Research, 14(3), 345–360. doi:10.1016/0160-7383(87)90107-1

- Crawford, C., & Sternberg, J. (2015). Ecotourism regulation and the move to a green economy. Tourism in the Green Economy, 87.

- Dadvar-Khani, F. (2012). Participation of rural community and tourism development in Iran. Community Development, 43(2), 259–277. doi:10.1080/15575330.2011.604423

- Demunter, C., & Dimitrakopoulou, C. (2011). Industry, trade and services; Population and social conditions. Europe: European Commission.

- Dodo, O. (2015). Traditional taboos defined: Conflict prevention myths and realities. Harare: IDA Publishers.

- Dube, G. (2014). Informal sector tax administration in Zimbabwe. Public Administration and Development, 34(1), 48–62. doi:10.1002/pad.v34.1

- Duval, D. T. (2006). Grid/group theory and its applicability to tourism and migration. Tourism Geographies, 8(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/14616680500392424

- Eijgelaar, E., Peeters, P., & Piket, P. (2008). Domestic and international tourism in a globalized world. Documento presentado en Research Committee RC50l International Sociological Association Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, Noviembre, 24-26.

- Ferdaush, J., & Faisal, H. (2014). Tourism potentiality & development of Bangladesh: Applicability of pragmatic governmental management policy. Journal of Management and Science, 4(1), 71–78.

- Gallarza, M. G., Del Chiappa, G., & Arteaga, F. (2018). Value-satisfaction-loyalty chain in tourism: A case study from the hotel sector. In The Routledge handbook of destination marketing (pp. 163–176). Routledge.

- Ghimire, K. B. (2013). The native tourist: Mass tourism within developing countries. Routledge.

- Gladstone, D. L. (2005). From pilgrimage to package tour: Travel and tourism in the third world. Routledge.

- Höckert, E. (2014). Unlearning through hospitality. In Disruptive tourism and its untidy guests (pp. 96–121). Springer.

- Hudson, S., & Ritchie, B. (2002). Understanding the domestic market using cluster analysis: A case study of the marketing efforts of Travel Alberta. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 8(3), 263–276. doi:10.1177/135676670200800305

- Kabote, F., Vengesayi, S., Mapingure, C., Mirimi, K., Chimutingiza, F., & Mataruse, R. (2013). Employee perceptions of dollarization and the hospitality industry performance. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research, 2(10), 31.

- Lew, A., & McKercher, B. (2006). Modeling tourist movements: A local destination analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 403–423. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2005.12.002

- Manono, G., & Rotich, D. (2013). Seasonality effects on trends of domestic and international tourism: a case of Nairobi National Park, Kenya. Journal of Natural Sciences Research, 3(1), 131–139.

- Manwa, A. H. (2007). Is Zimbabwe ready to venture into the cultural tourism market? Development Southern Africa, 24(3), 465–474. doi:10.1080/03768350701445558

- Mariki, S., Hassan, S., Maganga, S., Modest, R., & Salehe, F. (2011). Wildlife-based domestic tourism in Tanzania: experiences from northern tourist circuit. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management, 4, 4.

- Mavhunga, C. C. (2014). Transient workspaces: technologies of everyday innovation in Zimbabwe. MIT Press.

- Mazimhaka, J. (2006). The potential impact of domestic tourism on Rwanda’s tourism economy. Johannesburg: School of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand.

- Mazimhaka, J. (2007). Diversifying Rwanda’s tourism industry: a role for domestic tourism. Development Southern Africa, 24(3), 491–504. doi:10.1080/03768350701445590

- Mbohwa, C. (2008). Operating a railway system within a challenging environment: Economic history and experiences of Zimbabwe’s national railways. Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management, 2(1). doi:10.4102/jtscm.v2i1.45

- McCabe, S. (2009). WHO NEEDS A HOLIDAY? EVALUATING SOCIAL TOURISM. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(4), 667–688. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2009.06.005

- McCabe, S., & Diekmann, A. (2015). The rights to tourism: reflections on social tourism and human rights. Tourism Recreation Research, 40(2), 194–204. doi:10.1080/02508281.2015.1049022

- McKercher, B. (2008). The implicit effect of distance on tourist behavior: A comparison of short and long haul pleasure tourists to Hong Kong. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 25(3–4), 367–381. doi:10.1080/10548400802508473

- Mkono, M. (2012). Zimbabwe’s tourism woes in the last decade: Hindsight lessons for African tourism planners and managers. Tourism Planning & Development, 9(2), 205–210. doi:10.1080/21568316.2011.630749

- Moseley, J., Sturgis, L., & Wheeler, M. (2007). Improving domestic tourism in Namibia: Project report. Worcester, Massachusetts: Worcester Polytechnic Institute.

- Moyano, A., Coronado, J. M., & Garmendia, M. (2016). How to choose the most efficient transport mode for weekend tourism journeys: an HSR and private vehicle comparison. The Open Transportation Journal, 10, 1. doi:10.2174/1874447801610010084

- Mutana, S., & Zinyemba, A. Z. (2013). Rebranding the Zimbabwe tourism product: A case for innovative packaging. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 2(4), 95–105.

- Muzapu, R., & Sibanda, M. (2016). Tourism development strategies in Zimbabwe. Management, 6(3), 55–63.

- Nagai, H., & Kashiwagi, S. (2018). Japanese students on educational tourism: current trends and challenges. In Asian youth travellers (pp. 117–134). Springer.

- Ndlovu, Nyakunu, E., & Heath, E. T. (2011). Strategies for developing domestic tourism: A survey of key stakeholders in Namibia. International Journal of Management Cases, 12(4), 82–91. doi:10.5848/APBJ.2011.00017

- Page, Essex, S., & Causevic, S. (2014). Tourist attitudes towards water use in the developing world: A comparative analysis. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10(1), 57–67. doi:10.1016/j.tmp.2014.01.004

- Ritchie, & Crouch, G. (1993). Competitiveness in international tourism: A framework for understanding and analysis. World Tourism Education and Research Centre, University of Calgary.

- Rogerson. (2015). Restructuring the geography of domestic tourism in South Africa. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-economic Series, 29(29), 119–135. doi:10.1515/bog-2015-0029

- Rogerson, & Lisa. (2005). ‘Sho’t left’: Changing domestic tourism in South Africa. Paper presented at the Urban Forum. doi:10.1007/s12132-005-1001-0

- Rule, S., Viljoen, J., Zama, S., Struwig, J., Langa, Z., & Bouare, O. (2003). Visiting friends & relatives (VFR): South Africa’s most popular form of domestic tourism. Africa Insight, 33(1/2), 99–107.

- Sharma, T., Sehrawat, A., & Chauhan, A. (2014). Domestic tourism destination preferences of Indian Youth. Himalyan Journal of Contemporary Research, 3(1).

- Shinde, K. A., & Rizello, K. (2014). A cross-cultural comparison of weekend–trips in religious tourism: Insights from two cultures, two countries (India and Italy). International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 2(2), 3.

- Sirakaya-Turk, E., Ingram, L., & Harrill, R. (2008). Resident typologies within the integrative paradigm of sustaincentric tourism development. Tourism Analysis, 13(5–1), 531–544. doi:10.3727/108354208788160405

- Strauss, W., & Howe, N. (1991). Generations: The history of America’s future, 1584 to 2069. New York.

- Thomas, D. (1993). The distribution of income and expenditure within the household. Annales d’Economie et de Statistique, 109–135. doi:10.2307/20075898

- Urry, J., & Larsen, J. (2011). The tourist gaze 3.0. Sage.

- Wang, Q, Wang, H.O.N.G, & Qi, Z. (2016). An application of nonlinear fuzzy analytic hierarchy process in safety evaluation of coal mine. Safety Science, 86, 78–87. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2016.02.012

- Yap, G. C., & Allen, D. (2011). Investigating other leading indicators influencing Australian domestic tourism demand. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, 81(7), 1365–1374. doi:10.1016/j.matcom.2010.05.005