?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper identifies the factors influencing women participation in politics in the SADC region. The paper drew from the fact that the 30% average woman participation rate is still only half way to the target of 50% women representation required by the Protocol on Gender and Development of 2008. The paper argues that full and equal participation of both women and men in political decision-making provides a balance that more accurately reflects the composition of society, and may as such enhance the legitimacy of political processes by making them more democratic and responsive to the concerns and perspectives of all segments of society. Based on the pooled OLS and GMM dynamic panel of Blundell and Blond (1998) on 14 SADC countries over the period 2010–2017, the findings show that labor participation, functioning of government, political culture, the overall political participation have a positive relationship with women political participation. Results showed that civil liberties, human development index, electoral process and pluralism have a negative relationship with women political participation. The study recommended that governments, the SADC region, engage political players, especially political parties, to ensure that they actively involve and appoint more women in their political structures.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper identifies the factors influencing women participation in politics in the SADC region. The paper drew from the fact that the 30% average woman participation rate is still only half way to the target of 50% women representation required by the Protocol on Gender and Development of 2008. The paper argues that full and equal participation of both women and men in political decision-making provides a balance that more accurately reflects the composition of society, and may as such enhance the legitimacy of political processes by making them more democratic and responsive to the concerns and perspectives of all segments of society. The paper showed that factors such as labour participation, functioning of government, political culture, the overall political participation create a conducive environment for women political participation. Civil liberties, human development index, electoral process and pluralism were seen to hinder women political participation.

1. Introduction

Women’s full and effective political participation is a matter of human rights, inclusive growth and sustainable development (OECD, Citation2018a). The active participation of women, on equal terms with men, at all levels of decision-making and political involvement is essential to the achievement of equality, sustainable development, peace and democracy and the inclusion of their perspectives and experiences into the decision-making processes. Despite this, Kumar (Citation2018) states that in the twenty-first century, women are facing obstacles in their political participation worldwide. Women around the world at every socio-political level find themselves under-represented in parliament and far removed from decision-making levels. As noted in the Millennium Development Goals (United Nations, Citation2019), women’s equal participation with men in power and decision-making is part of their fundamental right to participate in political life, and at the core of gender equality and women’s empowerment. Strategies to increase women’s participation in politics have been advanced through conventions, protocols and international agreements for gender mainstreaming, but they are yet to prove effective in achieving gender parity in the highest government rankings (Morobane, Citation2014). Half of the world’s population are women, but today women only hold 23% of all seats in parliaments and senates globally (Chalaby, Citation2017; Radu, Citation2018).

Given the fact that many states have ratified international conventions and protocols on gender equality and women political participation, the low level of women’s representation in government and political may be considered a violation of women’s fundamental democratic rights. The African government’s public commitments have not materialized into better protection for women and support for victims and this has made women to play outside the political ground. According to Rop (Citation2013) many African state sign and commit themselves to promoting gender parity in political participation, but end up shelving the agreement. Abuse of office and desire to acquire power through self-centred means has resulted in the state ignoring women concerns. Thus, women continue to be underrepresented in governments across the nation and face barriers that often make it difficult for them to exercise political power and assume leadership positions in the public sphere. The UN (Citation2011) concurs and states that, “women in every part of the world continue to be largely marginalized from the political sphere, often as a result of discriminatory laws, practices, attitudes and gender stereotypes, low levels of education, lack of access to health care and the disproportionate effect of poverty on women”.

Literature has shown that the factors that hamper or facilitate women’s political participation vary with level of socio-economic development, geography, culture, and the type of political system (Shvedova, Citation2005; Alzuabi, Citation2016). In Africa, for instance, women are striving to assert an influential role in determining the course of their states but, they have been faced with many challenges that have actually strengthened their resolve. Moreover, the political environment and conditions are often unfriendly or even hostile to women (Shvedova, Citation2005). Often the after effects of the consequences of abuses that women and girls face during conflicts are ignored and under-reported, especially when it comes to political participation and women involvement in politics and governance. Lack of political will comes from the political parties in Africa who only think of how they can expand power and win elections. Anything that does not give these is seen as impractical. This has jarred the confidence of women in their ability to participate in political processes. In fact, this reflects the reality around the globe. And the Southern African Development Community (SADC) is no different in this global trend. Figures for most of the countries still fall short of the target set by SADC to have 50% women in decision-making positions (SADC, Citation2019). In light of this, this study seeks to examine the factors that influence woman political participation in the SADC region.

2. An overview of the developments of women political participation in southern Africa

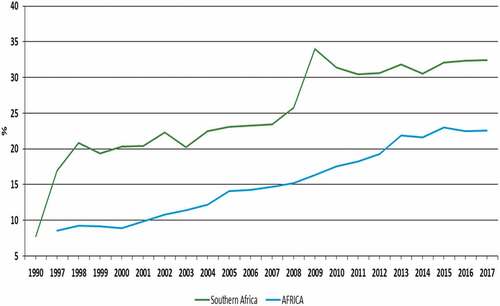

Southern African Development Community (SADC) Member States are proactively working towards equal representation of men and women politics and decision-making positions at all levels such as in Cabinet; Parliament, Council, Management of the Public Services, Chief Executive Officers and Boards of State-Owned Enterprises/Parastatals as well as the Private sector (SADC, Citation2019). In order to promote women participation in politics, SADC adopted the Declaration on Gender and Development in 1997 and the Protocol on Gender and Development in 2008. The former sought to increase women participation in government to 30% by 2005 and the latter sought to ensure that at least 50% of decision-making positions in the public and private sectors are held by women. SADC’s efforts have not gone unrewarded. The SADC region has the highest levels of proportion of seats held by women in parliament in the world. These are displayed in Table and Figure .

Table 1. Proportion of seats held by women in national parliament (%)

Table and Figure show that the proportion of seats held by women in national parliament have been steadily rising in both the SADC region and Africa in general. However, the rate has been much higher in the SADC region that in Africa and the world in general. Although Southern Africa may have numerically significant women’s parliamentary representation, some of the world’s worst performers are also in the SADC region. For example, women have only 6.2% representation in Swaziland (Africa Report, Citation2016), Botswana (9.5%) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (10.3%) (Inter-Parliamentary Union, Citation2019). Furthermore, the 30% average which is above the African is still only half way to the target of 50% women representation required by the Protocol on Gender and Development of 2008. Despite ongoing public support for these sorts of measures, however, the status of women, particularly in areas of politics and governance, has seen only nominal improvement.

Furthermore, wide variations between countries—from 10% WIP in DRC and Botswana, to 44% in Seychelles—means that countries need to adopt different timeframes for achieving gender parity with an outside deadline of 2030 (IAWRT, Citation2019). There are factors that have caused this. Political, socio-economic and cultural barriers predominantly constrain or prevent women’s participation in all SADC countries. The SADC (Citation2016) concurs and states that Patriarchal aspects of traditional cultural systems and male-dominated structures of modern governance are still a factor, although this too is changing, even changing rapidly in some parts of the region, more slowly elsewhere. Other challenges are the continuing structural rigidities within political parties, and lack of political will at various levels.

3. Literature review

Literature has shown that a number of factors act as barriers to woman political participation. Political, socio-economic and cultural barriers predominantly constrain or prevent women’s participation. These and other factors are discussed in this section.

3.1. Violent conflict, sexual violence and war

In many African states, politics is marred by violence, persecution, intimidation and torture. While both genders are victims of this, it presents particular barriers to women’s engagement and political participation. According to the United Nations (Citation2015) an Afrobarometer survey showed that women feel “a sense of vulnerability to political intimidation and violence”. The Afrobarometer survey further showed that in Guinea, for instance, 64% of women say they are very concerned about political intimidation. The effects of war continue for years after the fighting ends. While entire communities suffer the impact of armed conflict, women and girls are often the first to lose their rights to education, to political participation and to livelihoods, among other rights being bluntly violated.

However, there are others who argue that women may decide to engage more actively in public life or participate in politics as a way to cope with the adversities of war. Quantitative studies have shown that the incidence of war and conflict is positively related to political participation. In other words, some studies (Blattman, Citation2009; Bellow and Miguel, Citation2009; Annan, Citation2011 and De Luca & Verpoorten, Citation2015) have found that individuals exposed to wartime violence exhibit higher levels of civic and political engagement after the conflict. For example, Bellows and Miguel (2009) found that conflict-related displacement and deaths in Sierra Leone led to greater political participation and political awareness. Similarly, Blattman (Citation2009) presents evidence for a connection linking past violence in Northern Uganda to increased engagement in politics among (arguably) randomly abducted ex-combatants. Annan et al. (2011) show that women returning from armed groups in Uganda reintegrate socially and are resilient. As survivors of conflict, the expansion of women’s roles in post-conflict reconstruction often leads to the emergence of women’s organizations and networks. Through these organizations and networks, women mobilize to integrate a gendered perspective and women’s representation into peace negotiations and throughout the post‐conflict period (World Bank, Citation2011).

3.2. Electoral contests: voter intimidation, persecution, arbitrary arrests and assassinations

Election violence is a coercive and deliberate strategy used by political actors—incumbents as well as opposition parties—to advance their interests or achieve specific political goals in relation to an electoral contest (Adolfo, Kovacs, Nyström, & Utas, Citation2012). As a consequence, many politicians resort to illicit electoral strategies and make use of militant youth wings, militias or the state security forces to either win the election or strengthen their post-election bargaining position. Electoral violence is one problem that has been identified as a stumbling block to robust participation of women in the political process and in governance. Violence against women is used as a targeted and destructive tool in various ways throughout the electoral cycle to dissuade women from participating as election administrators, voters, and candidates (Para-Mallam, Citation2015). Zakari (Citation2015) further states that violence against women in elections could be overt or subtle; beyond violence that does physical harm, there is violence manifesting in terms of gender-based hate speech, with the sinister aim of deterring women from presenting themselves as candidates or voting elections. Failure to address these electoral barriers creates an atmosphere that makes women to have a negative attitude towards political activities. Behrendt-Kigozi (Citation2012) notes that political violence and the social stigma that politics is a dirty game is a further stumbling block for women to enter politics.

3.3. Institutional factors: party politics

Another mechanism through which violent conflict can induce structural changes that affect the supply of female politicians is institutional. Institutional constraints include barriers such as political systems that operate through rigid schedules that do not take into consideration women’s domestic responsibilities, and the type of electoral quotas used (if any) (Kangas, Haider, Fraser, & Browne, Citation2015). The adoption of new electoral or party rules during or after war may facilitate women’s entry into politics. Lack of adequate support structures to rectify existing codified institutions to include women in political leadership and achieve gender equality in global politics (Morobane, Citation2014). Political parties do not want to implement reforms because they fear they would lose political support and consequently, political power. They, therefore, oppose changes that are likely to make them cede power. Perhaps this might be because of the fact that they would be serving political parties that are patriarchal and practise dirty politics. A number of them appeared to be blindly following political leaders with very little knowledge of what is going on.

3.4. Cultural and traditional norms

According to George (Citation2019) women’s ability to engage politically both within and beyond the voting booth—particularly as community organisers and elected officials—is often shaped by norms that drive wider social structures. Fundamental to the constraints that women face is an entrenched patriarchal system in which family control and decision-making powers are in the hands of males. Traditional beliefs and cultural attitudes—especially as regards women’s roles and status in society—remain strong, particularly in rural areas (Sadie, Citation2005). Traditional roles and the division of labour are still clearly gendered. Social norms that make it more difficult for women to leave their traditionally domestic roles for more public roles outside of the home (Kangas et al., Citation2015). Women’s gender identity is still predominantly conceived of as being domestic in nature, and continues to act as a barrier to women’s entry into formal politics.

3.5. Economic factors

Socio-economic status of women to a greater extent play a significant role in enhancing their participation and representation in political decision-making bodies (Kassa, Citation2015). Women lack the economic base which would enhance their political participation (Suda, 1996 cited in Karuru, Citation2001). The lack of an economic base for women has been a factor in their participation—or lack of—it in politics because the cost of campaigning is very high. Lack of financial resources can limit participation given the costs associated with elections (WPL, Citation2014; Kayuni & Chikadza, Citation2016; Common Wealth, Citation2017). Independent funding and placing limits on campaign spending may support women in overcoming the barriers to political participation. Access to power tends to emerge from familial, communal and economic linkages, and these factors may help explain patterns of participation.

4. Methodology

4.1. Model specification

The empirical model of this study is related to the work of Manning (Citation2014). Manning (Citation2014) investigated the effects of electoral systems and gender quotas on female representation in national legislatures in 188 countries. In Manning’s (Citation2014) study female political participation was a function of type of electoral system, the presence or absence of a quota system, countries’ level of egalitarianism, level of development, and predominant religion. This study builds on Manning (Citation2014) and formulates the following model:

The model can be expressed in its linear form as:

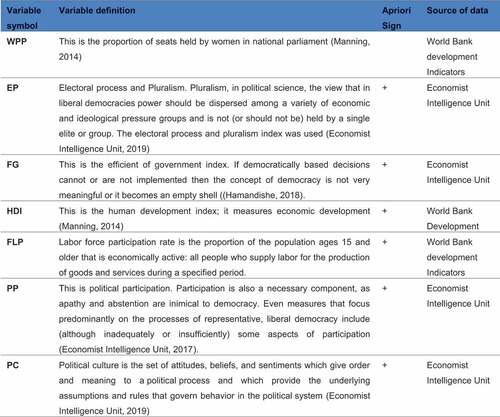

where WPP is the women political participation (proportion of seats held by women in national parliament), EP is the electoral process and pluralism, FG is functioning of government, HDI is human development Index, FLP is female labour participation, PC is political culture, PP is Political Participation and is an error term.

4.2. Sources and description of data

The data used in this study are obtained mainly from the Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy as well as the World Bank. The study employs yearly panel data and the panel data set covers all SADC countries (excluding Comoros and Seychelles. These countries were excluded because they did not have adequate data for key variables) in the years 2010, 2015, 2016 and 2017. Figure shows the description of data.

4.3. Estimation techniques

This study was carried out by static panel data and dynamic panel data analysis under the pooled OLS estimator and the GMM model, respectively. The estimation techniques used are discussed below.

4.3.1. Static model

Nwakuya and Ijomah (Citation2017) claim that in pooled OLS regression we simply pool all observations and estimate the grand regression, ignoring the cross-section and time-series nature of the data, in which case the error term captures everything. Simplest method is just to estimate by OLS with a sample of NT observations, not recognizing panel structure of data. Standard OLS would assume homoskedasticity and no correlation between unit i’s observations in different periods (or between different units in the same period) (Schmidheiny, Citation2018). The pooled OLS estimator ignores the panel structure of the data and simply estimates α, β and γ as:

where W = [ιNT × Z] and ιNT is a NT × 1 vector of ones (Schmidheiny, Citation2018).

The study used the Hausman’s test and the Wald Test to find the best estimation technique. The results from these tests showed that the fixed effects and random effects models were inconsistent when compared to the pooled OLS estimator. Moreover, their results were explosive and so were their normality test results. The results from the pooled panel regression had normal distribution and the results had significant t-values. The study therefore used the pooled OLS estimator.

4.3.2. Dynamic model

In order to corroborate the Pooled regression results, the GMM estimator was used. The GMM estimator has the advantage that it is more efficient than the OLS estimator. It is also widely known as a solution to measurement errors (errors in variables) and omitted variable biases (Guillaumont and Kpodar, Citation2006). Furthermore, it allows for endogenous regressors and takes account of the endogeneity of the lagged dependent variable at the same time. Moreover, it models initial observations for the sake of including the first time period. According to Chowdhury (Citation2016) the GMM dynamic panel estimator makes two assumptions: (i) transient errors are serially uncorrelated;

and (ii) the explanatory variables are not correlated with future realisations of the error component. For the endogenous variables, the study relied on the “internal instruments that are one lag variables” (El Hamma, Citation2016). The GMM procedure used in this study allows the use of lagged independent variables as instruments (Bond, Hoeffler, & Temple, Citation2001).

4.3.3. Robustness checks

To check the validity of the instruments, the J-statistic was applied. The J-statistic, introduced in Hansen (Citation1982), refers to the value of the GMM objective function evaluated using an efficient GMM estimator (Baum & Schaffer, Citation2003; University of Washington, Citation2019). As with other instrumental variable estimators, for the GMM estimator to be identified, there must be at least as many instruments as there are parameters in the model (Eviews, Citation2019). In models where there are the same number of instruments as parameters, the value of the optimized objective function is zero. Baum (Citation2013) concurs and states that the J-statistic will be identically zero for any exactly identified equation, it will be positive for an over-identified equation. If there are more instruments than parameters, the value of the optimized objective function will be greater than zero. The J− statistic acts as an omnibus test statistic for model mis-specification and a large J− statistic indicates a miss-specified model (Baum, Citation2013) and (University of Washington, Citation2019).

The J-statistic of this study turned out to be 15.98. This was high and the study had to drop the Civil Liberties (CL) variable from the variable and instrument list and re-estimated the model again. The J-statistic dropped to 0.711. This is close to zero and it may suggest that the GMM model was exactly identified and the instruments were valid.

5. Presentation of primary findings

Results from the static model (pooled regression) are displayed in Table .

Table 2. Panel pooled regression

Results from the static model are similar in terms of their signs to those of the dynamic model. Results from the dynamic model are presented in Table .

Table 3. GMM results

Results show that there is a statistically significant negative relationship between electoral process and pluralism and women political participation. In other words, countries with efficient levels of electoral process and pluralism are likely to have low levels of women political participation. The results are surprising because the condition of having free and fair competitive elections, and satisfying related aspects of political freedom, is clearly the basic requirement for effective female participation in politics. However, empirical evidence support the findings from this study. For instance, an OECD (Citation2018b) report stated that though the tide is shifting, and women are becoming increasingly involved in political life with each new election—they face specific barriers in accessing political office. Various obstacles—often interwoven—include restricted access to financial resources, gender stereotypes, and traditional social norms. Literature also shows that women are lobbied to support election campaigns and they are blindly encouraged to be vocal in elections campaigns but silent in political decision-making (Sindhuja & Murugan, Citation2017; Cheeseman & Dodsworth, Citation2019). When the elections are over, they are expected to be silent and this limits their political participation. This then limits their political participation hence a negative relationship between electoral process and pluralism and women political participation.

Results also show that there is a statistically significant positive relationship between the functioning of government and women political participation. In other words, countries with poor functioning of government are likely to have low levels of women political participation. The results make sense because if decisions cannot or are not implemented effectively and efficiently then policies that seek to promote gender equality and women political participation will be ineffective. Results are also consistent with empirical literature. It has been seen that a good number of African governments (including SADC countries) have developed policies and laws to achieve and promote gender equality (which can be a necessary condition for woman political participation) (Global Partnership for Education, Citation2018). When the government is efficient governance will also be efficient. The doctrines of democratic governance and human rights are premised on the notion of equal participation by all citizens in any country. This is why it is important for women to have equal and meaningful representation and participation in all facets of governance (Hamandishe, Citation2018).

Results show that there is a statistically significant negative relationship between the Human development index and women political participation. In other words, countries with higher levels of human development are likely to have low levels of women political participation. The results are surprising because when there is development, political participation is also expected from all spheres of life. However, the results are consistent with empirical findings. For instance, Cabeza-García, Del Brio, and Oscanoa-Victorio (Citation2018) note that for the existence of a positive relationship between the presence of women in parliament and economic growth, little empirical evidence is available. There are factors that hinder women from participating in politics even though their economic status may have improved. These included cultural factors (Kunovich, Paxton, & Hughes, Citation2007; Kassa, Citation2015) the patriarchal nature of household set up in Africa (Komath, Citation2014; Kumari, Citation2014). Even in countries where women have made gains in employment or education, they face cultural barriers to participation in politics (Kunovich et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, it has been seen that even when their economic status is improving, woman may spend devote less time to other activities (including politics) and spend farm more time on household chores and family care responsibilities (Kassa, Citation2015). Furthermore, the nature of household set-ups in SADC and African countries, the results may make sense. Many women are depended on their husbands and male bread winners and even if they can get more income from them, they may not voluntarily participate in politics because of the control their male counterparts have on them. Seyedeh, Hasnita, and Hossein (Citation2010) also revealed that most of women are financially dependent on their husbands or relatives. So they may not be possible to them to enter in political campaign. Kassa (Citation2015) states that most African women are always dependent on men economically which is the main cause for their low participation to politics.

Results show that there is a statistically significant positive relationship between the female labour participation and women political participation. In other words, countries with high labour participation levels are likely to have high levels of women political participation. According to Kassa (Citation2015) it’s a fact women’s participation in political life depends largely on their access to employment which gives them not only material independence but also certain professional skills and grater self-confidence. So that access to means of production and finances has a direct relationship and influence on the participation of women in political institutions. Furthermore, female labour force participation may reduce women dependence on men. When women are not dependent on men they might participant in politics without any restrictions (Kassa, Citation2015).

Results show that there is a statistically insignificant positive relationship between political culture and women political participation. This relationship is not significant in the dynamic model (GMM). However, the relationship is significant in the static model. Ndirangu, Onkware, and Chitere (Citation2017) states that an egalitarian culture fosters women’s involvement in electoral politics, but hierarchical culture impedes it. How favorably or unfavorably the society views women’s involvement in politics depends on where its culture lies in the egalitarian-hierarchical cultural spectrum. Women experience greater obstacles toward political office in societies where traditional attitudes reign, but modernization, value changes and the fading of cultural barriers, results in younger generations of women in post-industrial societies experiencing less resistance to entering political offices (Ndirangu et al., Citation2017).

Results show that there is a statistically significant positive relationship between political participation and women political participation. In other words countries with high political participation levels are likely to have high levels of women political participation. Democracies flourish when all citizens (including women) are willing to take part in public debate, elect representatives and join political parties (Economist Intelligence Unit, Citation2017). Without this broad, sustaining participation, democracy begins to wither and become the preserve of small, select groups especially male-controlled and dominated institutions.

6. Summary and recommendations

This paper identifies the factors influencing women participation in politics in the SADC region. The paper showed that political participation, as measured by the proportion of seats held by females in parliament, is much higher in the SADC region that in Africa and the world in general. This is impressive but it was also noted that some of the world’s worst performers, in terms of women political participations, are also in the SADC region. Furthermore, the 30% average which is above the African is still only half way to the target of 50% women representation required by the Protocol on Gender and Development of 2008. The paper argues that full and equal participation of both women and men in political decision-making provides a balance that more accurately reflects the composition of society, and may as such enhance the legitimacy of political processes by making them more democratic and responsive to the concerns and perspectives of all segments of society.

Based on the pooled OLS and GMM dynamic panel on 14 SADC countries over the period 2010–2017, the results showed that labour participation, functioning of government, political culture, the overall political participation have a positive relationship with women political participation. Results further showed that civil liberties, human development index, electoral process and pluralism have a negative relationship with women political participation. Based on these results, the paper makes the following recommendations:

Firstly, there is need for governments to engage political parties to ensure that they include more women on their candidates list. Political parties should become the institutional vehicle through which women’s participation in politics is enhanced especially in facilitating their participation within party structures and over election periods. Secondly, there is more need to engage women through awareness campaigns. Women need to be educated and be informed that political participation is not limited to election campaigns and mobilisation. They also need to know that for political participation to be inclusive there should be equal participation by both women and men. Thirdly, governments should provide more funds to independent female political politicians and also to political parties that have a considerable and accepted number of female political candidates. This will make political parties to involve more women for political office. Fourthly, governments should promote the economic emancipation of women. When women are economically emancipated, they will be able to make their decisions independently and this may pave way for them to enter politics without being restricted by their male counterparts (who may be breadwinners or husbands at home).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Courage Mlambo

Dr Courage Mlambo’s research interests lie in Development Economics, Politics and Economics in general. However, his research and publication repertoire is versatile including Economics of regulation, Monetary Economics, Labour economics, Macroeconomics, Social Justice, Politics, Banking and Finance. So far he has published more than 10 papers in internationally recognized journals.

Forget Kapingura

Dr F. Kapingura is a senior Lecturer at the University of Fort Hare in South Africa.

References

- Adolfo, E. V., Kovacs, M. S., Nyström, D., & Utas, M. (2012). Electoral violence in Africa. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:556709/fulltext01.pdf

- Africa Report. (2016). Africa sees a boost in the number of women legislators. Retrieved from https://www.theafricareport.com/2909/africa-sees-a-boost-in-the-number-of-women-legislators/

- Alzuabi, A. Z. (2016). Socio-political participation of kuwaiti women in the development process: Current state and challenges ahead. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5062044/

- Annan, J., Blattman, C., Mazurana, D., & Karlson, K. (2011). Civil war, reintegration, and gender in northern uganda. Journal of Conflict Resolution. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0022002711408013

- Baum, C. F. (2013). IV and IV-GMM. Retrieved from http://www.ncer.edu.au/resources/documents/IVandGMM.pdf

- Baum, C. F., & Schaffer, M. E. (2003). Instrumental variables and GMM: Estimation and testing. Retrieved from https://tind-customer-agecon.s3.amazonaws.com/45314139-34f9-4de4-bd97-229251b51857?response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3D%22sjart_st0030.pdf%22&response-content-type=application%2Fpdf&AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAXL7W7Q3XHXDVDQYS&Expires=1557844872&Signature=4EXupFxkZ%2Fo4jKElK8RevN7m844%3D

- Behrendt-Kigozi, H. (2012). Empowerment of women in politics. Retrieved from https://www.kas.de/veranstaltungsberichte/detail/-/content/empowerment-of-women-in-politics

- Bellow, J., & Miguel, E. (2009). War and local collective action in sierra leone. Journal of Public Economics, 93, 1144–13.

- Blattman, C. (2009). From violence to voting: War and political participation in uganda. American Political Science Review. Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/from-violence-to-voting-war-and-political-participation-in-uganda/ADC2215665477FE69F4DAA6B23826501

- Bond, S. R., Hoeffler, A., & Temple, J. (2001). GMM estimation of empirical growth models. Retrieved from https://www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/users/bond/CEPR-DP3048.PDF

- Cabeza-García, L., Del Brio, E. B., & Oscanoa-Victorio, M. L. (2018). Gender factors and inclusive economic growth: The silent revolution. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/a/gam/jsusta/v10y2018i1p121-d125733.html

- Chalaby, O. (2017). Ranked and mapped: Which countries have the most women in parliament. Retrieved from https://apolitical.co/solution_article/which-countries-have-most-women-in-parliament/

- Cheeseman, N., & Dodsworth, S. (2019). Why African democracies are failing women — And what we can do to fix it. Retrieved from https://mg.co.za/article/2019-03-08-00-why-african-democracies-are-failing-women-and-what-we-can-do-to-fix-it

- Chowdhury, M. (2016). Financial development, remittances and economic growth: Evidence using a dynamic panel estimation. Margin, 10(1), 35–54. doi:10.1177/0973801015612666

- Common Wealth. (2017). Women’s political participation in the commonwealth. Retrieved from http://thecommonwealth.org/media/news/women%E2%80%99s-political-participation-commonwealth

- De Luca, G. D., & Verpoorten, M. (2015). Civil war and political participation: Evidence from Uganda. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 64(1), 113–141. doi:10.1086/682957

- Economist Intelligence Unit. (2017). Democracy Index 2017: Free speech under attack. Retrieved from https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadFile?gId=34079

- El Hamma, I. (2016). Linking remittances with financial development and institutions: A study from selected MENA countries. Retrieved from https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01655353/document

- E-views. (2019). Instrumental variables and gmm. Retrieved from http://www.eviews.com/help/helpintro.html#page/content/gmmiv-Instrumental_Variables_and_GMM.html

- George, R. (2019). Gender norms and women’s political participation: Global trends and findings on norm change. Retrieved from https://www.alignplatform.org/resources/2019/02/gender-norms-and-womens-political-participation-global-trends-and-findings-norm

- Global Partnership for Education. (2018). How African policies are promoting gender equality in education: Today we celebrate international day of the girl. Retrieved from https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/how-african-policies-are-promoting-gender-equality-education

- Guillaumont, S., & Kpodar, K. R. (2006). Development Financier, Instabilit Finan- Cire et Croissance Conomique” Economie et Prvision, 174, 87–111.

- Hamandishe, A. (2018). Rethinking women’s political participation in Zimbabwe’s elections. Retrieved from https://www.africaportal.org/features/rethinking-womens-political-participation-zimbabwes-elections/

- Hansen, L. P. (1982). Hansenlarge sample properties of generalized methods of moments estimators. Econometrica, 50, 1029–1054.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2019). Women in national parliaments. Retrieved from http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/ClaSSif.htm

- Kangas, A., Haider, H., Fraser, E., & Browne, E. (2015). Gender and governance. Retrieved from https://gsdrc.org/topic-guides/gender/gender-and-governance/

- Karuru, L. N. (2001). Factors influencing women’s political participation in Klbera division, Nairobi. Retrieved from http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/11295/21070/Karuru_Factors%20Influencing%20Women%27s%20Political%20Participation%20In%20Klbera%20Division%2C%20Nairobi.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- Kassa, S. (2015). Challenges and opportunities of women political participation in Ethiopia. Retrieved from https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/challenges-and-opportunities-of-women-political-participation-in-ethiopia-2375-4389-1000162.php?aid=64938

- Kayuni, H. M., & Chikadza, F. K. (2016). The gatekeepers: Political participation of women in Malawi. Retrieved from https://www.cmi.no/publications/5929-gatekeepers-political-participation-women-malawi

- Komath, A. (2014). Patriarchal barrier women politics. Retrieved from http://iknowpolitics.org/en/knowledge-library/opinion-pieces/patriarchal-barrier-women-politics

- Kumar, P. (2018). Participation of women in politics: Worldwide experience. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327057539_Participation_of_Women_in_Politics_Worldwide_experience

- Kumari, R. (2014). Patriarchal politics: The struggle for genuine democracy in contemporary India. Retrieved from https://www.boell.de/en/2014/02/26/patriarchal-politics-struggle-genuine-democracy-contemporary-india

- Kunovich, L., Paxton, P., & Hughes, M. (2007). Gender in politics. Annual Review of Sociology.

- Manning, A. (2014). The effects of electoral systems and gender quotas on female representation in national legislatures. Retrieved from http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1595/the-effects-of-electoral-systems-and-gender-quotas-on-female-representation-in-national-legislatures

- Morobane, F. (2014). Women grossly under-represented in international politics. Retrieved from http://www.ngopulse.org/article/women-grossly-under-represented-international-politics

- Ndirangu, N. L., Onkware, K., & Chitere, P. (2017). Influence of political culture on women participation in politics in Nairobi and Kajiado counties. Retrieved from http://strategicjournals.com/index.php/journal/article/view/513

- Nwakuya, M. T., & Ijomah, M. A. (2017). Fixed effect versus random effects modeling in a panel data analysis; A consideration of economic and political indicators in six African countries. International Journal of Statistics and Applications, 7(6), 275–279.

- OECD. (2018a). Women’s political participation in Egypt barriers, opportunities and gender sensitivity of select political institutions. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/mena/governance/womens-political-participation-in-egypt.pdf

- OECD. (2018b). WOMEN’S political participation in JORDAN. Retrieved from www.oecd.org/mena/governance/womens-political-participation-in-jordan.pdf

- Para-Mallam, O. J. (2015). Focus group discussions on violence against women in elections in Kogi state, Nigeria. Stop-Vawie Project: A Report. Retrieved from https://www.ndi.org/files/EXAMPLE_NDI%20Focus%20Group%20Discussion%20Report_Kogi%20State%20Nigeria.docx

- Radu, S. (2018). Women still a rare part of world’s parliaments. Retrieved from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2018-09-04/women-are-still-underrepresented-in-parliaments-around-the-world

- Rop, V. (2013). African women and political participation: A worrying trend. Retrieved from http://www.catholicethics.com/forum-submissions/african-women-and-political-participation-a-worrying-trend

- SADC. (2016). SADC gender and development monitor. Retrieved from https://www.sadc.int/issues/gender/sadc-gender-and-development-monitor-2016/

- SADC. (2019). Women in politics & decision-making. Retrieved from https://www.sadc.int/issues/gender/women-politics/

- Sadie, Y. (2005). Women in political decision-making in the SADC region. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4066648.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A3e02ca47208b5dc4c5e21bb15ee0c3cb

- Schmidheiny, K. (2018). Panel data: Fixed and random effects. Retrieved from https://www.schmidheiny.name/teaching/panel2up.pdf

- Seyedeh, N., Hasnita, K., & Hossein, A. (2010). The financial obstacles of women’s political participation in Iran. UPMIR. Retrieved from http://www.sciencepub.net/report/report0210/06_3810report0210_41_49.pdf

- Shvedova, N. (2005). Obstacles to women’s participation in parliament. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d998/eb3ddb02ef10d7a1b4f1d0fd15dbc95c557f.pdf

- Sindhuja, P., & Murugan, K. R. (2017). Factors impeding women’s political participation - A literature review. International Journal of Applied Research. Retrieved from http://www.allresearchjournal.com/archives/2017/vol3issue4/PartI/3-4-78-866.pdf

- The International Association of Women in Radio & Television. (2019). Women in politics. Retrieved from https://www.iawrt.org/sites/default/files/field/pdf/2016/12/Women%20in%20Politics%202016_mf_102016.pdf

- United Nations. (2011). General assembly 66th session (2011). Retrieved from http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/documents/ga66.htm

- United Nations. (2015). A celebratory rise in women’s political participation. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/april-2015/celebratory-rise-women%E2%80%99s-political-participation

- United Nations. (2019). Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/

- University of Washington. (2019). Generalized method of moments. Retrieved from https://faculty.washington.edu/ezivot/econ583/gmm.pdf

- World Bank. (2011). World development report 2011: Conflict, security and development. Washington DC: Author.

- WPL. (2014). Which are the barriers for women’s participation in politics? (wip/world bank survey). Retrieved from https://www.womenpoliticalleaders.org/barriers-womens-participation-politics-wipworld-bank-survey/

- Zakari. (2015). Halting violence against women in Nigeria’s electoral process. Retrieved from https://guardian.ng/features/halting-violence-against-women-in-nigerias-electoral-process/