Abstract

This paper attempts to show the importance of sacred natural sites (SNS) among indigenous peoples and local communities serving as the locus of maintenance, continuity and expressions of religious identity drawing lessons from Sidama nation of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Regional State of Ethiopia. The paper further addresses the relationship between SNS and ancestor veneration and their mutual interdependence and preservation, exploring the socio-ecological and biocultural foundations of the interrelationship between the two systems, the dynamics of religious syncretism, and the resilience and challenges of threat facing the two systems. The paper argues that SNS and ancestor worship systems and the mutual interrelationships that exist therein are resilient social-ecological systems, created and maintained dynamically as biocultural diversity realities in historical ecological framework through human–environment interactions over millennia; and that SNS are, therefore, critical in supporting nature protection and strengthening local traditions and institutions such as ancestor worship as form of religious identity expression.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This paper attempts to show the importance of sacred natural sites among indigenous peoples and local communities serving as the locus of maintenance, continuity and expressions of religious identity drawing lessons from Sidama nation of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Regional State of Ethiopia. The paper further addresses the relationship between sacred sites and ancestor veneration and their mutual interdependence and preservation, exploring the interrelationship between the two systems, the dynamics of religious mixing, and the resilience and challenges of threat facing the two systems. The paper argues that sacred sites and ancestor veneration systems are resilient social-ecological systems, created and maintained dynamically as biocultural diversity realities in historical framework through human–environment interactions over millennia; and that sacred sites are critical in supporting nature protection and strengthening local traditions such as ancestor worship as a form of religious identity expression.

1. Background and introduction

Sacred natural sites (SNS) are the physical entities and natural landscapes such as trees, forest areas, mountains caves, rivers, that are set apart as holy by virtue of societal beliefs and values (Verschuuren, Citation2010). Ancestor worship is a form of traditional, animistic religion whereby deceased ancestral figures occupy central places in the religious ideologies and day to day life practices of the community (Ukpong, Citation1983; von Heland & Folke, Citation2014). The interdependence between SNS and ancestor worship are being recognized as salient components in the social, conservation and policy sciences dimensions of the biocultural diversity literature (Higgins-Zogib, Dudley, Mallarach, & Mansourian, Citation2010; Sponsel, Citation2012). Studies documenting the role of indigenous institutions such as ancestor worship have received growing attention from disciplinary perspectives in anthropology, religious studies and related fields of scholarship. The biocultural diversity and conservation literature often devote significant attention to the role SNS play in biodiversity conservation (Maffi & Woodley, Citation2010; Sponsel, Citation2008) and the contributions of religion, both mainstream and traditional, to the environment and sustainable development (Bhagwat, Dudley, & Harrop, Citation2011). The relevance of SNS in the practice, continuity and maintenance of ancestor worship and the intimate ties the latter has with the SNS has received little attention in the literature.

Empirical studies exploring the interdependence between SNS and ancestor worship and their relevance for society and the environment in Ethiopia has received little attention. Emerging studies have generally focused on the role SNS play in the conservation of biodiversity components such as endangered fauna and flora. Other studies have attempted to provide anthropological, socio-economic or jurisprudence relevance of ancestor worship and sacred sites, failing to address the socio-ecological and biocultural values that bind the two (see for example, (Hamer, Citation2002).

This paper attempts to show the importance of SNS among indigenous peoples and local communities serving as the locus of maintenance, continuity and expressions of religious identity (Posey, Citation1999; Sponel, Citation2001; Sponsel, Citation2016), drawing a lesson from the Sidama of Ethiopia. The paper further addresses the relationship between SNS and ancestor worship, exploring the socio-ecological and biocultural foundations of the interrelationship between the two systems, the dynamics of religious syncretism, and the threats facing the two systems.

2. Materials and methods

This research draws on my research engagements among the Sidama in south-western Ethiopian, conducting commissioned studies for the Southern Regional Government of Ethiopia (SNNPRS) in general (2008–2013) and my own PhD fieldwork (June 2012- May 2013) as part of a PhD study at the University of Kent, the United Kingdom. Lessons from these fieldworks and data are drawn to document coupled human (religious traditions) and biodiversity systems. The studies employed broadly qualitative techniques and data relevant for the present paper were collected using mixed methods comprising an assortment of tools and materials, including inventories of sacred groves; observation of past and current use of the SNS for religious and related purposes; interviews, groups discussions and household surveys documenting how individuals, households and various components of local community perceived, behaved and practiced with respect of SNS and ancestor worship. Data were analyzed using NVivo 10. Findings from the household survey were integrated as corroborative information for qualitative analysis.

3. Significance and novelty of the paper

This paper contributes towards filling the gaps in the literature about our knowledge and understanding of the connection between SNS and ancestor worship; and the nature and relevance of SNS in the practice, maintenance and continuity of ancestor worship as a viable and resilient religious identity. The lessons drawn based on the case materials from Sidama are hoped to shed some light on the status of SNS as the locus of religious identity expression; the principles drawn from the millennia of salutary and nature-friendly relationship that existed between SNS and ancestor worship may also contribute towards creating and promoting the healthy human-nature relationship at a global scale.

4. Results

4.1. The study community: the landscape and the people

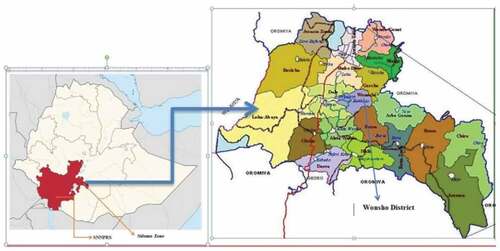

The present political-administrative region, known as Sidama Zone, is one of the major administrative areas in Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ Regional State (SNNPRS), located about 275 km southwest of Addis Ababa (Figure ).

The land is characterized by varieties of topographic, climatic and agro-ecological features. The Great East African Rift Valley divides Sidama land into two, the western lowlands and eastern highlands. The altitude ranges from 500 masl in the west to 3500 masl in the eastern highlands, with mean annual temperature and rainfall of 10–27 0c and 800–1600 ml, respectively (Yilma, Citation2013). The local botanical environment, ecology and agricultural landscape is rich in a diverse and dense floristic community, from massive, high-growing native trees to the ubiquitous and popular Eucalyptus, as well as other recently introduced exotic trees. These serve multiple needs including agroforestry; firewood; aesthetics and ornament; herbal medicine; shade for crops, animals and humans; soil fertility management; income sources and food security supplement.

The land is also home to many sacred forests, where various tree species and other biodiversity are conserved. These, along with traditional agroforestry, support an extractive form of conservation of otherwise endangered native tree species and diverse flora (Asfaw, Citation2003). Intensive crop cultivation, cash crop production and animal husbandry form the basis of the economy. The major food crops include maize, sugar beet, false banana, wheat, peas, beans, yam and taro, while the major cash crops are coffee, çaate (Catha edulis), banana and various other fruit trees.

Description of the Sidama needs to be situated in the broader Ethiopian and southwestern regional context. Ethiopia is known for its ethnic, cultural, linguistic and livelihood diversities. Having paleo-anthropological and archaeological records of global importance and an ancient civilization, Ethiopia is at the heart of the birthplace of humanity, the Rift Valley of East Africa. Over 85 ethnic groups speaking some 150 dialects exist, making the country one of the most culturally diverse countries of the world (Henze, Citation2000; Munro-Hay, Citation2002; Pankhurst, Citation1995). Communities practicing a plethora of traditional religions and maintaining SNS exist in higher density in the southern and southwestern part of the country and they constitute a great majority of the country’s ethnic groups (Vaughan, Citation2003).

Ethiopia is a home for of a number of religions. The country was one of the first to adopt Christianity in the fourth century and Islam in the eighth century, while Judaism had been in existence for over several hundreds of years before Christianity and Islam in the country (Marcus, Citation1994; Zewde, Citation2001). Indigenous religions thrived in the country for millennia until the introduction and dominance of Christianity and Islam although they are still in existence particularly in the southwestern and southern parts of the country. The 2007 Population and Housing Census provides Christianity (all forms and denominations notably Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, Protestantism and Catholicism combined together) as the most dominant (over 62%) followed by Islam (around 33%) and adherents of traditional faiths at 2.6% (CSA, Citation2012). A small Judaic religion adherent currently exists in the country. Adherents of the Baha’i faith also exist in some urban quarters. The distributions of the religions in the southern Ethiopia where the study community reside follows a more or less similar pattern, with Christianity combined dominant, followed by Islam and traditional religions. However, when the further breakdown is seen, Protestant Christianity is the dominant religion at 55%, followed by Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity at 20%, Islam at around 14%, Roman Catholics at 2.4% and traditional religions at around 1.5% (CSA, Citation2013).

Southwest Ethiopia is noted for being home of over 56 ethnic groups and is well known for its rich mix of peoples, cultures, languages, ecologies, traditional knowledge and livelihoods (Cerulli, Citation1956; van der Lans, Kemper, Nijsten, & Rooijackers, Citation2000; Zewde, Citation2001). The region’s peoples maintain diverse ethnohistorical origins, socio-cultural systems and practice multiple livelihood systems including home gardens, hunting and gathering, pastoral-nomadism, agro-pastoralism, agro-forestry and intensive agriculture (Abebe, Wiersum, & Bongers, Citation2010; Adugna, Citation2014; Asfaw, Citation2003) .

The Sidama are a Cushitic people of east Africa in southwest Ethiopia (Braukämper, Citation1978), with estimated population size over 3 million (CSA, Citation2013), although various other sources estimate the population between 4 and 5 million (Doffana, Citation2017, Citation2018; Hameso, Citation2018; Wansamo, Citation2014). Oral tradition and available historical sources (Braukämper, Citation1973) sources suggest the ancient Cushitic Sidama ancestors were part of the great population movements in the first century AD from North Africa moving towards the south of the continent (Braukämper, Citation2012; Munro-Hay, Citation2002). It is now generally agreed that northeast Africa and the south Arabian Peninsula were hot-spots of Afro-Asiatic peoples, including proto-Cushites of Ethiopia whose descendants include the Sidama.

Sidama traditional socio-political organization is clan-based and patriarchal; each clan being further structured into smaller sub-clans and patrilocally organized villages (Hamer, Citation1970). A form of gerontocratic structure, based on the generational class system, has been a key aspect of the polity and social organization (Hamer, Citation2007; Kumo, Citation2009). The highest rank in the hierarchy was held by the moottee (king). All matters of community importance were discussed in a form of indigenous parliamentary assembly called the Songo.

The moottee oversees the secular politico-defense system; the womma, holder of another high rank, administers religious and cultural affairs. However, there have been variations in the power and responsibilities of such cultural and political positions across clans and over the years (Hamer, Citation2007). The political system contained aspects of traditional democratic and egalitarian values (Aadland, Citation2002; Stanley, Citation1966). This system has been enduring challenges since 1893 (Hameso, Citation1998) when Sidama was incorporated into the Ethiopian nation-state under the reign of Emperor Menilik II (1889–1913) (Donald & James, Citation1986). Currently, the traditional social-political organization has generally been weakened despite a resurgence in recent years.

4.2. Characterizing ancestor worship in Sidama

I examine here origins and general characteristics of ancestor worship in Sidama as a way to situate the ontological and functional basis of sacred sites. The ancestral religion bears the mark and essence of sacredness of the SNS. The prevalence of an ancestor cult as an important social institution, linked to an overarching worldview, has enabled the creation of SNS. Like that of other traditional peoples of Ethiopia, Africa and the world over, the Sidama ancestral religion involves SNS as the loci of worship and important venues for a range of socio-cultural affairs, rituals and community engagements and religious identity expressions (Hamer, Citation2002). Sidama ancestral religion, like other African traditional religions, may be conceptualized as consisting the ancestral beliefs, rituals and institutions that cohere in a folk-theological framework and include notions of the nature of beings, rituals undertaken to reinforce values and the phenomenon of a moral community created through exercise of communal ceremonies and feasts (Durkheim, Citation1965; Keesing, Citation1981).

Sidama ancestral religion displays both monotheistic and polytheistic elements in the sense that the core of the system is belief in Magano (“the Supreme Being”) on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the veneration of annu-akako ayana (“spirits of deceased ancestors”), instrumentalized through sacred trees and forests (Brøgger, Citation1986). Amate woxxa (“the cult of feminine figures”) also has some place in the ancestral religion but it is marginal (Tekile, Tsegay, Dingato, Garsamo, & Bada, Citation2012). The “ancestors-as-mediators” concept is central and the veneration of ancestors a key practice in the religion, as the deceased ancestors are believed to mediate between humans and the creator (Hamer, Citation1976). One such notable ancestor is Abbo, the founding ancestor of a major clan in Sidama, and is the center of traditional religion in a part of Sidama where I had a case study. A major sacred grove (about 93 hectare) stands today as a witness to the memorial of this apical ancestor and currently serves as a key center of socio-cultural, religious, environmental protection and biodiversity conservation significance. The practice of traditional religion is dependent on nature, not only in terms of natural sites and elements providing physical spaces for the conduct of the religion but also the requirement of certain animals and plants for rituals. Different types of animals and plants are used in the various rituals. This though might contribute to biodiversity loss, it is undertaken in a small-scale manner in carefully, ritually controlled ways.

The socio-demographics and social organization of religious rituals and sacred groves There are recognized ritual leadership positions in Sidama traditional religion, combining religious, social and political roles. The Ganna is the ultimate ritual-political leadership position in matters relating to the governance of sacred groves and ancestral rituals. These are masculine. Adherence to ancestral religion and holding leadership positions are prerogatives of adults and older persons.

With respect to the attitudes, local people maintain towards sacred groves, while a generally respectful attitude was displayed among the general public, such a posture was rather more intense among women. Married women consider sacred groves and native trees, such as Podocarpus falcatus and Croton macrostachyus, as equivalent to their in-laws. As a female informant reported, “we revere trees very much such as podo under whose shade respected male elders sit. We consider the grove itself as our in-laws.” Their fear and respect is so much so that it is balisha, a taboo that prohibits Sidama women from calling the names and terms for men, objects, places and events that directly or indirectly invoke these names. This is as a show of deep fear and respect for their male-in-laws, living or deceased. When travelling, and if perchance they approach a sacred grove (of their male in-laws), married women are not supposed to walk past or near it, they will even cover their faces and eyes until they pass. It is believed that if a married woman knowingly calls the forbidden name, “she would die or get mad”. Similarly, women pay great homage to certain spatial and topographic entities that bear some ethnohistorical reference to ancestors.

Sidama ancestral religion involves placations, prayers, places addressed to ancestors; and making of vows, requests for healing, wealth, blessings, children, bounteous crops, etc. The use of a designated worship place is an important aspect of social organization. The practitioners would use a family graveyard as a temple to placate spirits of their immediate ancestors while communal sacred groves would be used for worshipping common ancestors at higher clan scales.

Various denominations of Protestant Christianity, notably, the Full Gospel Believers’ Church, the Word of Life Church, the Mennonite Mission and the Lutherans are the dominant mainstream denominations in Sidama in general, while ancestor worship has declined significantly especially since the 1960s following the expansion of missionary work in the region. However, interviews and common observations show that many still practice ancestor worship and those that identify themselves officially as Protestants may also still continue as ancestor worshippers, although clandestinely. Such stance may have some negative impacts on the ancestral religions, denigrating it and this is a major source of challenge to the religion at the present.

In my survey of sacred groves in seven study communities, I identified several formerly existing sacred groves which at the time of the fieldwork (back in 2013) were either completely transformed to other land-use forms or they existed in a severely degraded condition. In former generations, most people believed that trees such as Podocarpus, existing in sacred groves, actually represented ancestors and cutting these trees “was like cutting the flesh of our ancestors.” This exemplifies how changing ethos in attitudes and orientations impacted the socio-ecological balance. Informants, for example, lamented that long years ago, before the introduction of Protectant Christianity and introduction of cash-crops based economy, the land teemed with sacred groves; at that time, there was lush landscape, many wildlife and tree species. However, with increasing supportive policy environments and a back to ancestral culture movement since the 2000s, local informants reported that many people now openly practice their ancestral religion. As one old man noted, “We do not regard our ancestral religion as such in opposition with Christianity or Islam. It is part of our cultural identity. We go to Church, but we also participate in our ancestral rituals.”

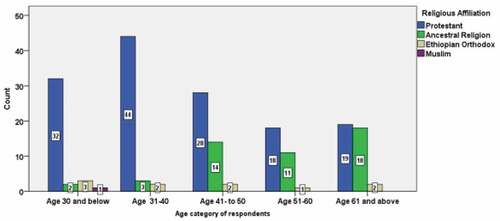

In the household survey, 141 respondents (70.5%) of sample households (n = 200) were Protestant Christians while 24% (48) adhered to ancestral religion. This appears as a microcosm of the overall picture. Adherence to ancestral religion was stronger among older persons. This is quite congruent with the findings from qualitative interviews and general observations. Aged persons in the survey (60 and above) had a significantly higher percentage of following compared to those in age groups below 40 (Figure ).

Figure 2. Religious affiliations by age category of household heads, HHS, September 2012, Sidama, Ethiopia (Source: own survey, 2012–2013).

It is worth pausing at this juncture to investigate religious composition and syncretism found in study households, and to further understand the distribution of sacred sites among other mainstream religions and their views of ancestral traditions. Maintenance of household sacred groves varied across these religious lines. Adherents of ancestral religion were more likely to own and maintain a sacred site. Respondents were asked whether they maintained a grove for non-economic purposes and adherents of ancestral religion were found, quite expectedly, more likely to engage maintaining trees for ritual needs. Practice of ancestral rituals and attitudes towards such are also closely related to religious adherence. Tree-based rituals are the essence of ancestral religion. Attitudes and practices of respondents reveal that differences between various religious groups might be blurred. Reported behavioral and attitudinal positions and actual practices might also differ.

Maintenance of sacred groves in Sidama is directly associated with the practice of ancestral religions. We would expect that the adherents of ancestral religion were more likely to report positive opinions of ancestral rituals. Significantly higher percentage (87.5%) of ancestral religion followers reported engagement in such rituals, while only 29.1% of Protestants reported so. The report by Protestants in the affirmative may show a number of local dynamics in the religious landscape; one is the phenomenon of religious syncretism and coexistence whereby native religious conversion to Protestantism may not be so radical as to require a complete abandoning of ancestral religion. In limited instances such things do occur.

4.3. The interdependence of nature and religion in Sidama ancestral religion

A salient dimension of the relationship between sacred natural sites and ancestor worship in Sidama is the local perception regarding the nature and ontology of sacred groves. Among the Sidama, members of the local community adhering to ancestral religion hold a strong belief that sacred groves in general and some cultural keystone trees in particular did actually emerge not merely through the natural process but by the agency of ancestral spirits. During my fieldwork, thus, it was a common encounter to hear people say that “no human hand planted the trees of the sacred site;” and that some trees of major ritual importance, such as Podocarpus falcatus, found in a major sacred forest were literally “willed into existence by the spirit of the founding ancestor.” In the words of an old man who practiced traditional religion, “The [sacred] forest emerged and was kept by the spirit of [the founding ancestor]. No man planted it. The spirit of the ancestor issued an order for the trees to sprout.” This “divine causation theory” of sacred groves is anthropologically crucial, as they add high value to the cultural capital that constitutes their site protection and tree management framework. The belief that these sites and trees represent ancestors is central in the local perceptions of the relationship between sacred groves and ancestral religion.

An equally salient dimension of the relationship between sacred natural sites and ancestral religion is that sacred groves in general and the shades of culturally keystone trees, in particular, serve as an essential physical space for the conduct of religious rituals. The use of sacred groves or woody trees as temples derives from a belief in the imbuement of such physical places or entities with ancestral spirits. In most instances, the bodies of ancestors are present at the groves and in other instances, they may be absent. Households, clansmen and other concerned community members use sacred groves as valued temples where ancestral rituals of placation, commemoration and thanks-giving are conducted. Not all native trees are eligible for such ritual enactments. Different trees are used in various aspects of the ritual process. Depending on their availability and local variation, the shade of any one of these may be used as temples. However, Podocarpus falcatus stands out as the most valued and honoured of all, defining the sacredness of most of the existing sacred groves. As one old steward of a sacred grove noted, “There is nothing more beautiful than a podo tree.” Another old man said, ‘A neighborhood without a sacred grove [notably a group of podo trees] is like a sick man.” Sadly, such salutary socioecological heritages are also in decline as a widening intergenerational gap is happening and those local people endowed with rich ethnobotanical knowledge and tree venerating values and attitudes are declining (see further in the last section).

As temples, sacred sites play a crucial role in serving the practitioners helping them to express and enact their religious values (and preserve them through practice), to meet the deep longings of the practitioners’ psycho-social and spiritual quests, and to thus reinforce their religious identities amidst tough competition for religious allegiance. The actual enactments of such beliefs and practices in turn work towards preserving the ancestral religion, for example, through preventing forest clearing for agriculture, settlement or extractive enterprises.

To reiterate, ancestral religious traditions, institutions, and events that support and depend on sacred forests and trees have existed in Sidama for an unknown, but presumably a long time. The desire to honour, placate, and commemorate ancestors is an overriding element in rituals. A remark from an adherent of ancestral religion seems to be a typical representation of the core ethos: “For us as Sidama, in our ancestral tradition, we cannot separate our cultural trees [such as podo, sycamores, etc.] and our ancestral culture … . Our Sidama ancestral culture [such as ancestor veneration] is unthinkable without sacred groves and trees.” Conduct of ancestral rituals under the shade of native trees is one salient reason that necessitates sacred sites and their maintenance.

A range of related but distinct rituals that use trees and sacred sites as important objects take place centring around ancestors and bringing clan and community members together through communal participation in these rituals. One such manifestation of ancestral religion is what locals call the dasho, as an informant describes it: “Dasho is our main get-together event which takes place every seven or 8 years and it is a forum that attracts the faithful from all over the Sidama land. They congregate at a major sacred grove [such as Abo Wonsho, a major sacred grove in Sidama land]. The dasho event is so named as it connotes the mass sacrifice of oxen when blood flows like flood and people feast on meat venerating their ancestors.” The rituals are important symbols of respect and recognition for ancestors and the belief in their continuing presence among the people.

Although ancestral religion appears to be more substantively linked to nature than other the other religions in the region, other religious traditions also express and promote a mutual relationship with nature. During the fieldwork, I had the opportunity to visit some Ethiopian Orthodox Church premises where many important native trees were preserved. Nationally, research shows that over 34,000 Ethiopian Orthodox churches in the country existed, which were often considered as “an island of trees” (Eshete, Citation2007).

4.4. Sacred groves and dynamics of religious syncretism

The term “syncretism” denotes the coalescence of cultural traits in its broadest sense but is often employed with reference to religion. Syncretism in religion is an important phenomenon in Ethiopia. As a religiously diverse country, with two major world religions present from their beginnings, there has been the opportunity for syncretism driven by multiple factors in Ethiopia. Aspects of native religions and identities existed in syncretic ways among communities throughout southwest Ethiopia, although native religions were often shrouded under the cloak of mainstream religions (Girma, Citation2012). Syncretism may, thus, be an important factor in the continuity of at least certain elements of traditional religions in southwest Ethiopia.

Among the Sidama, ancestor worship maintains a dynamic relationship with other religions, particularly Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Islam, although some informant who reported membership in these religions often tended to see ancestral religions as a form of cult, a tendency that is much more pronounced among the Protestant Christians, particularly the Full Gospel denomination. A Sidama informant who reported his membership as Full Gospel noted that “my church does not generally encourage people to attend the ritual events of the ancestral religion.” Syncretism of religious ideas, symbols and practices are plainly evident, as is the case in many other parts of southwest Ethiopia (Braukamper, Citation1992), demonstrating that ancestral religion is not just a homogenous entity; rather, it has creatively incorporated elements through dynamic interactions with other systems of thought and institutions, affecting and being affected thereby. At the time of the fieldwork, it was not uncommon to observe or hear local reports about practitioners of ancestor worship exhibiting syncretic ideas and behaviors, participating in the rituals of mainstream religions; on the other hand, practitioners of mainstream religion also (particularly those adhering to Islam and Ethiopian Orthodox Church- EOC) often took part in the rituals and services rendered by ancestral religion. Syncretism between ancestral religion and Islam and EOC was much more pronounced. These religions are less likely to require radical dissociation from ancestral rituals compared to Protestant Christianity.

It may be thus argued that, as the data supports, complex interactions exist among the different religions in Sidama. While the reasons for such variations may require a further investigation in its own right, it may be worth noting at this juncture that the interaction between ancestral religion and Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Islam on the one hand and ancestral religion and Protestantism on the other may be explained by what most informants refer to as the degree of strictness in rules and demands required from adherents of the “main” religions and the existence of similar religious ethos between the traditional religion and the other “dominant” religions. As one informant noted, “Sidama ancestral religious adherents feel more at home with Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Islam because there are similar practices and beliefs such as the veneration of mediators between diving being and humans.” Another informant noted, citing the case of the sacred cite temple at a major sacred grove in Sidama, the Abo Wonsho, that it is modeled after church buildings of Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity. There are, for example, three sacred enclosures in increasing degree of holiness in the Abo Wonsho sacred site temple (the outer most enclosure where most people can access, the second enclosure where a limited number of people may access and the third holiest inner enclosure where only the holy priests may gain access).

Regarding the variation in degree of syncretism between ancestral religion and Islam on the one hand and ancestral religion and Protestantism on the other, informants noted that the ethnohistorical account in their traditional religion possess a claim to the Islamic origin of the identity of the founding ancestor of one of the main Sidama clan founders, though such view was not shared among all informants. It was for example, possible to observe Islamic individuals holding their religious vigils at the sacred site during our field observation. Protestantism was reported as the least likely to embrace the ethos and rituals of ancestral religion, requiring the strictest rules from tis members. As a church elder of a Full Gospel Church at one of the study localities reported, “our church passes strict codes regarding association with ancestral religious rituals; although we may take part in general communal affairs together with adherents of ancestral religion, no one of our church members may partake in eating the ritual meat.”

The phenomenon of religious syncretism and co-existence is, therefore, an important factor in the present social landscape of the community. Progressive increase in the phenomenon was confirmed and was generally salutary for the continuity of ancestral traditions, useful tree-based traditions and overall conservation outcomes for sacred sites and trees. Tree-based traditions include planting native trees as a sign of respect and remembrance for deceased ancestors, use of tree shades for executing rituals, social gatherings, and employment of trees in various ways as part of a range of traditional ceremonies.

In recent years, increasing levels of community engagement, local government actions and, especially, the educated members, have worked towards both creating and fostering this religious syncretism and coexistence on the one hand, and countering the rather radical stances of denigration of ancestral rituals, on the other. A locally elite (educated informant) reported “During the Dergue era [Socialist Regime, 1974–1991], it was common to hide one’s ancestral religious identity; ritual leaders were often harassed, groves were cut down; now since the fall of Dergue, such hostility towards ancestral religious traditions has declined; people are now more likely to see ancestral religion as a cultural identity.” In local school curricula (particularly at elementary levels), as part of ecological and scientific education, topics on useful values relating to environment and biodiversity conservation are often included, as a local school principal noted, “We often encourage our students to get more aquatinted with their ancestral traditions. There are sacred groves visit programs. Students also engage in tree planting in affected scared site areas.”

4.5. Challenges and the future facing SNS and ancestral religion

Observation of existing objective conditions indicates that there has been downward spiral in ancestral traditions since the onset of the twentieth century in general and the pace of the change accelerated, particularly since the 1950s and 1960s, with the intensification of demographic changes, expansion of modern religions and related socio-economic transformations. Most local informants generally agree with this assessment. Significant challenges to sacred groves exist, thereby posing dangers to ancestor worship.

Large-scale sacred forests particularly meet the local community’s livelihood needs in such areas as firewood, fodder gathering, wild-honey collection, harvesting medicinal plants, wild edibles, obtaining drinking water for humans and cattle, among others. Furthermore, households in closer proximity to such sacred forests also derive other services such as bathing in rivers and springs, washing clothes, conducting market exchanges, tethering or tending cattle, equines or small ruminants. While many of these practices may be sustainable, they are nonetheless progressively losing their traditional ethos as people become more and more orientated towards meeting their livelihood challenges.

Rapid population growth and increasing livelihood challenges have been generating changes in the social structures, economic organization, land use and cover types and priorities, including the conversion of formerly forested areas of sacred lands. Farmland scarcity is one of the effects of this process. These also generate growing socio-economic demands, such as fuel needs and cash to support decreasing food self-sufficiency. The increasing demand for firewood and the allure of gaining cash through the sale of charcoal and firewood in local markets for growing urban demands are also related major drivers.

State policies and development interventions further pose significant challenges, as local people agree. According to informants, much of the land was teeming with sacred groves and practice of ancestor worship was thriving; however, with the incorporation of Sidama into the Ethiopian nation-state since the 1890s, the nature-culture linkage as deteriorated as government policies and development interventions often forced removal of forest areas to clear for establishment of town settlements, government office building, market places, schools, and roads. Coupled with the introduction of market-oriented cash crops (often as part of state agricultural modernization policy) these processes have particularly escalated since the 1950s and 1960s, although there are signs of improvement since the current government took power in the 1990s. Some, however, accuse the current government as a cause for ethnic tensions and conflicts through its ethnic-based regional divisions stating that this is in some places a factor in increased encroachments into church forests and other forest areas (see for example Berahne-Selassie, Citation2008).

Given the reality of increasing livelihood and population increase challenges on sacred sites and ancestral traditions, it may be argued that cultural diversity is being eroded and indigenous values are in dramatic retreat. This may further suggest that the positive roles of ancestral traditions are more of historical significance. Further, this may entail a threat to the future of sacred sites in the region affecting future human-environment interactions. I argue there is on one hand a veritable sign of danger leading sacred sites to lose their power as the years go by, as the intergenerational gaps in attitudes towards sacred sites is a cause for concern. On the other hand, as presented above, recent positive policy environments have encouraged a resurgence in ancestral traditions and support for sacred groves and ancestral religion. This is further supported by national, regional and local protection initiatives. For example, a collaborative governance between the sacred grove stewardship and the local district government have recently stepped up the protection of sacred groves, penalizing those who transgress and fell down trees from sacred groves.

5. Discussion

5.1. Sacred nature and traditional religion: an ethnographic review

Sacred sites and traditional religions have had an inextricable affinity; paleo-anthropological research suggest that the origin of sacred sites can be traced to what some call “the cult of ancestor worship,” which has been in existence for the past 50,000 years (Verschuuren, Citation2010). It is important to note that globally, sacred sites tend to concentrate in regions where traditional religion and biodiversity flourish (Bhagwat et al., Citation2011). Where traditional religion persists, mainly in parts of Sub Saharan Africa, South America, Southeast Asia and other less developed nations (Park, Citation1994), sacred natural sites in the form of ancestral burial grounds, groves, palaver trees, initiation grounds, etc., have played a central role in these religious systems. Traditional conceptions of plants, animals and environment, in general, are best understood as what scholars call an eco-centric view of nature. Biodiversity and the natural world, in general, are part of the holistic web of animate and inanimate life that comprises all living forms, as well as the insentient natural world (Ingold, Citation1992).

Ethiopia’s over 85 distinct ethnic groups maintain age-old environmental and biodiversity knowledge systems and institutions. These systems and concepts are generally reflections of the broader frameworks of the people’s conceptions of nature and the place of humans in it. The country’s major faith groups, Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and Islam are linked to and internationally recognized for UNESCO world heritage sites. The former with its widespread national presence (over 34,000 such churches), owns thousands of fragments of sacred groves including the last remnants of Afro-montane tropical forest (Massey, Bhagwat, & Minnis, Citation2014). However, despite a lack of systemic documentation and mapping of the country’s bicultural diversity areas vis-à-vis ancestral religions, common observations show a high concentration of such areas in those parts of the country where ancestral religions show relatively higher degrees of robustness.

Thus, in Sidama and many of communities in Africa and beyond, sacred groves are the important locus for ancestral religious practice and the ancestral spirits and gods are believed to inhabit forests (Deil, Heike, & Mohamed, Citation2008; Gottlieb, Citation2008; Siebert, Citation2008). Sacred forests in Sidama are embodiments of deceased ancestors. Totemic symbolization of trees and animal species from time immemorial has been an important aspect of cultures in Ethiopia, and across the world. In Sidama and among other ethnic groups in the country, a range of native tree species such as Podocarpus falcatus and Ficus vasta, Olea play key roles in ritual representations and contacts with the spirit world (Negash, Citation2010).

Across time and space, this is evident in a work Rival (Citation1998) edited wherein contributors attempt to address various theoretical and empirical dimensions of the “social lives” of trees and “the extent to which trees serve as symbols of trans-generational continuity” in different societies and cultures. Trees form the basis and mediums for meditation, worship, mysticism and related engagements among Amazonian Indians (Freedman, Citation2010; Nabhan, Pynes, & Joe, Citation2002; Schultes & Raffauf, Citation1992), Mayans (Anderson, Citation1996), indigenous peoples of the Indian sub-continent (Rao, Citation2002; Shiva, Citation1998) and China (Hsu, Citation2010), to name but a few. In short, as Rival (Citation1998) argues, trees occupy a key place in symbolism with somewhat near-universal relevance across time and space.

Sidama consideration of key ritual trees as very embodiments of ancestors is an instance of how traditional communities, custodians of sacred groves, owners of totemic trees, shamans and herbalists in general, approach trees as anthropomorphic beings (Schultes & Raffauf, Citation1992), as those that connect humans to gods and the spirit world (Pennacchio, Jefferson, & Havens, Citation2010). Traditional people hold a view of nature infused with the soul of itself, giving non-human life the capacity to be embodied and capable of possessing moral codes (Ellen & Fukui, Citation1996). Such a view provides animals and plants human dispositions and behaviours (Descola & Pálsson, Citation1996). This idea is echoed in what (Ǻrthem, Citation1996) calls “eco-cosmology”, which he argues is a concept that best captures the traditional model of human-environment relationship.

The case of sacred forest sites and some socio-culturally important trees serving as religious temples and worship objects is a key aspect of the issue of identity and culture. In a highly changing world in general and in a regional context where various religions compete for pre-eminence, the mainstream religions often supplant the ancestral religions (Hamer, Citation2002). Having sacred forests and socio-culturally imbued trees as religious objects is an important tool and evidence for local communities to show the vitality of their ancestral religious identity (Maffi & Woodley, Citation2010). The fact of ancestral religions vitally linked to a botanical territorial scale, thereby supporting biodiversity and the environment in general, is an important dimension that provides a crucial benefit for ancestral religions. It helps generate positive attitudes and sympathies from the government and other concerned agents, although it is also often seen as patronizing and romanticizing (Igoe, Citation2004; Johnston, Citation2006). Sacred forest sites make this possible.

Wonsho-Sidama ancestral religious institutions utilize sacred forests sites, trees and other landscapes, as mediums of worship, not the objects of worship in the sense that people venerate trees or groves per se. The services the latter provide for the former are one of the salient positive outcomes of maintaining sacred forests and native trees. What (Cunningham, Citation2001) calls a “theology of the environment” explains the ancestral religion whereby veneration of ancestors is central. Such a system is in turn possible through the spatio-temporal, symbolic and practical services sacred forests provide.

The ontology of sacred sites and biodiversity is enmeshed with the local-ancestral traditions. In the ethnological and ethnobotanical worldviews, sacred forests, landscapes and individual native woody trees are “mirror images” of local community, their identity embodying their past, present and future (Baindur, Citation2009; Fincke & Oviedo, Citation2008; Nazarea, Citation1999). Divine entities and ancestral spirits inhabiting sacred landscapes become not only vital parts but also are foundational cornerstones of this ontological reality for the local custodian community. From a local viewpoint, therefore, Wonsho sacred landscapes, sacred forests and ritual trees may be defined as “living entities in the social-spiritual realm,” entities that mirror the ancestors, the ethnohistorical past, the present identity and their ethnic future. An implicit idea that equates sacred forests and other sacred entities with one’s own identity, ancestors and historic past binds tree biodiversity with cultural diversity (Nazarea, Citation2006).

Sacred forest sites and native trees of Wonsho, Sidama are maintained; therefore, in a very important philosophical sense, to reinforce this time-honored identity, protect and demarcate this sacred spatial-temporal reality, show continued allegiance to ancestral spirits, placate and acknowledge them. In an important sense, therefore, the existence of sacred groves is founded on the socio-cultural and cosmological values and needs, not with a conscious desire for conserving biodiversity. Maintenance of sacred forest sites and protecting native trees is both a solemn end in itself and a social, sacred process for the local community.

5.2. Resilience and dynamism of sacred groves and ancestral religion

There are both threats (thus decline) and resilience (persistence) in both the sacred groves and the ancestor veneration. The topic attempts to transmit this message from early on: the mutual interdependence and resilience of sacred groves and ancestor veneration in the study community. Both the ancestor veneration and sacred groves are resilient and, at the same time, facing veritable threats. They are resilient to the threats of notably Protestantism and additionally the increasing challenges of socio-economic/poverty issues, leading people to prioritize more economic, material needs (which seem urgent) than social, spiritual priorities. The ancestor veneration and sacred groves are further resilient to the processes of modernization, changing sociocultural values and increasing influences of modern education and expansion of market-based economy arrangements. It is important here to note about the dynamic nature of sacred natural sites and ancestral religion.

With increasing recognition of traditional resource management and the relevance of indigenous knowledge systems, recent years have seen a growing interest in the sacred natural sites of the third world such as sacred groves in Africa with respect to understanding their origin, maintenance motivations and characteristics. A popular view about them has been one that saw sacred groves and traditional governance systems as relics from the primeval past. But emerging research has now shown that sacred groves and associated traditional institutions of governance are human artifacts and historically changing, shaped by human action over time (Sheridan & Nyamweru, Citation2008). They are ecologically and socially dynamic and complex, with changing meanings and compositions (Chouin, Citation2002).

Factors such as religious innovations, modern education, urbanization and cultural globalization pose potent challenges to biodiversity supporting ancestral institutions, putting a particularly growing pressure on Sidama traditional religion and sacred forests—the core of the ancestral traditions—over the past 110 years in general, and since the mid-20th century in particular, causing its drastic decline (Hamer, Citation2002), a fact that quite well aligns with similar processes around the world (Bodley, Citation1999). Existing sacred forests and ancestral religions are declining. Beneath the outward facts of the decline of sacred sites and ancestral religion, though, there exist dynamic processes whereby syncretism and interactions among the diverse worldviews sometimes happen to support ancestral institutions, adding to its continuity.

6. Conclusion

Understanding of local conceptions of custodian communities’ sacred histories that derive their sacredness from myths about founding ancestors; the intricacies of common ethnic roots and clan structures based on collective understandings; the social institutions and religious rituals that operate to validate and concretize these conceptions, etc., are crucial to understand the geography of sacred sites in Sidama and the nation at large. This especially becomes more important when we consider sacred sites that derive their validation from their association with the religious traditions of ancestor veneration, which is probably as old as humanity itself.

Sacred natural sites are showcases for the existence, maintenance and preservation of biocultural diversity (Loh & Harmon, Citation2014). Components of sacred nature such as ritual trees, historical-cultural heritage sites, groves, mountains, rivers, etc. make core physical and social loci for the practicing religious rituals. Sacred natural sites are, therefore, critical in supporting nature protection and strengthening local traditions and institutions such as ancestor worship in a traditional African society such as the Sidama of Ethiopia.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the Christensen Fund for providing me a financial scholarship to purse my PhD at the School of Anthropology & Conservation, University of Kent, the United Kingdom (2011–2015), from which this paper derives. I also want to thank Dr Rajindra Puri for his critical supervision and mentoring during my PhD study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zerihun Doda Doffana

An alumnus of University of Kent, UK (PhD- Anthropology & Conservation-2015); and AAU, Ethiopia (MA, Social Anthropology- 2001), I am an Assistant Professor at Department of Environment & Climate Change, Ethiopian Civil Service University (ECSU). I have over 22 years’ teaching, research and academic management experiences, undertaking mixed methods and ethnographic research on the interface of sociology and anthropology of identity, heritages, development, environment and and traditional resource use and management. Various publications arising from this engagement have been in use by the wider public and among universities. I have published in reputable media including the SAGE Handbook of Nature, Malaria Journal, COGENT Food & Agriculture, and COGENT Social Sciences. I have also served as reviewer for reputable journals including BMC Public Health, COGENT Environmental Sciences, SAGE Open.

References

- Aadland, O. (2002). Sera: Traditionalism or living democratic values?: A case study among the Sidama of South Ethiopia. In B. Zewde, & S. Pausewang, Ethiopia: The challenge of democracy from below (pp. 29–16). Uppsala: Forum for Social Studies.

- Abebe, T., Wiersum, K. F., & Bongers, F. (2010). Spatial and temporal variation in crop diversity in agroforestry homegardens of southern Ethiopia. Agroforestry Systems, 78(3), 309–322. doi:10.1007/s10457-009-9246-6

- Adugna, A. (2014). Southern nations nationalities and peoples demography and health. Retrieved from www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Orgwebsite

- Anderson, E. N. (1996). Ecologies of the heart: Emotion, belief, and the environment: Emotion, belief, and the environment. Oxford University Press.

- Ǻrthem, K. (1996). Cosmic food web: Human-nature relatedness in northwest Amazon. In P. Descola & G. Pálsson (Eds.), Nature and society: Anthropological perspectives (pp. 185–204). London: Routledge.

- Asfaw, Z. (2003). Tree species diversity, topsoil conditions and arbuscular mycorrhizal association in the Sidama traditional agroforestry land use, southern Ethiopia (Doctoral thesis). Retrieved from http://pub.epsilon.slu.se/214/

- Baindur, M. (2009). Nature as non-terrestrial: Sacred natural landscapes and place in Indian vedic and purānic thought. History, 6, 43–58.

- Berahne-Selassie, T. (2008). The socio-poliics of Ethiopia sacred groves. In M. J. Sheridan, & C. Nyamweru, African sacred groves: Ecological dynamics and social change (pp. 103–117). Athens, GA: Ohio University Press.

- Bhagwat, S. A., Dudley, N., & Harrop, S. R. (2011). Religious following in biodiversity hotspots: Challenges and opportunities for conservation and development. Conservation Letters, 4(3), 234–240. doi:10.1111/j.1755-263X.2011.00169.x

- Bodley, J. H. (1999). Victims of progress (Fourth ed.). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Pub. Co.

- Braukamper, U. (1992). Aspects of religious syncretism in southern Ethiopia. Journal of Religion in Africa, 22(3), 194–207.

- Braukämper, U. (1973). The correlation of oral traditions and historical records in southern Ethiopia: A case study of the Hadiya/Sidamo Past. Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 11(2), 29–50.

- Braukämper, U. (1978). The Ethnogenesis of Sidama. Paris. Abbay, 9, 123–130.

- Braukämper, U. (2012). A history of the Hadiyya in Southern Ethiopia: Translated from German by Geraldine Krause (Auflage: 1., Aufl.). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, O.

- Brøgger, J. (1986). Belief and experience among the Sidamo: A case study towards an anthro- pology of knowledge. Oslo: Norwegian University Press.

- Cerulli, E. (1956). Peoples of south-west Ethiopia and its borderland. Rome: International African Institute.

- Chouin, G. (2002). Sacred groves in history: Pathways to the social shaping of forest landscapes in coastal Ghana. IDS Bulletin, 33(1). Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/502137/Sacred_Groves_in_History_Pathways_to_the_Social_Shaping_of_Forest_Landscapes_in_Coastal_Ghana

- CSA. (2012). 2007 population and housing census of Ethiopia summary report. Retrieved from http://www.ethiopianvision.com/2007Census.pdf

- CSA. (2013). Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at wereda level from 2014 – 2017. Retrieved from http://www.csa.gov.et/images/general/news/pop_pro_wer_2014-2017_final

- Cunningham, A. B. (2001). Applied ethnobotany: People, wild plant use and conservation. London: Routledge.

- Deil, U., Heike, C., & Mohamed, B. (2008). Sacred groves in moroco vegetation mosaics and biological alues. In M. J. Sheridan & C. Nyamweru, African Sacred Groves: Ecological dynamics and social change (pp. 87–103). Athens, GA: Ohio University Press.

- Descola, P., & Pálsson, G. (Eds.). (1996). Nature and society: Anthropological perspectives. London: Routledge.

- Doffana, Z. D. (2017). Sacred natural sites, herbal medicine, medicinal plants and their conservation in Sidama, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 3(1), 1365399. doi:10.1080/23311932.2017.1365399

- Doffana, Z. D. (2018). The role of sacred natural sites in conflict resolution: Lessons from the wonsho sacred forests of Sidama, Ethiopia. In The SAGE Handbook of nature: Three volume set (Vols. 1–3, pp. 938–967). doi:10.4135/9781473983007

- Donald, D., & James, W. (1986). The southern Marches of imperial Ethiopia. Essays in history and social anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Durkheim, E. (1965). The elementary forms of the religious life. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Ellen, R. F., & Fukui, K. (1996). Redefining nature: Ecology, culture and domestication. Oxford, UK: Berg 3PL.

- Eshete, A. W. (2007). Ethiopian church forests: Opportunities and challenges for restoration ( PhD thesis). Wageningen University. Retrieved from https://www.wageningenur.nl/en/show/Ethiopian-church-forests-opportunities-and-challenges-for-restoration.htm

- Fincke, A., & Oviedo, G. (2008, October). Bio-cultural diversity and indigenous peoples journey (pp. 6–9). Barcelona, Spain: IUCN - World Conservation Congress.

- Freedman, F. B. (2010). Shamanic Plants and Gender in the Healing Forest. In E. Hsu & S. Harris (Eds.), Plants, health and healing on the interface of ethnobotany and medical anthropology (pp. 135–178). New York, NY: Beghahn Books.

- Girma, M. (2012). Understanding religion and social change in Ethiopia. Retrieved from http://www.bing.com/search?q=Understanding+Religion+and+Social+Change+in+Ethiopia+Toward+a+Hermeneutic+of+Covenant+Mohammed+Girma&pc=MOZI&form=MOZLBR

- Gottlieb, U. (2008). Loggers v. Spirits in the beng forest, cote dIvire. In M. J. Sheridan & C. Nyamweru (Eds.), African sacred groves: Ecological dynamics and social change (pp. 149–164). Athens, GA: Ohio University Press.

- Hamer, J. (1970). Sidamo generational class cycles. A political gerontocracy. Afica, 40, 50–70.

- Hamer, J. (2007). Decentralization as a solution to the problem of cultured diversity: An example from Ethiopia (Vol. 77, pp. 207–225).

- Hamer, J. H. (1976). Myth, ritual and the authority of elders in an Ethiopian society. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 46(4), 327–339. doi:10.2307/1159297

- Hamer, J. H. (2002). The religious conversion process among the Sidāma of North-East Africa. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 72(4), 598. doi:10.2307/3556703

- Hameso, S. (1998). The coalition of colonized nations: The Sidama perspective. Journal of Oromo Studies, 5(1 & 2), 105–133.

- Hameso, S. (2018). Farmers and policy-makers’ perceptions of climate change in Ethiopia. Climate and Development, 10(4), 347–359. doi:10.1080/17565529.2017.1291408

- Henze, P. B. (2000). Layers of time: History of Ethiopia (First UK Ed). London: C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd.

- Higgins-Zogib, L., Dudley, N., Mallarach, J.-M., & Mansourian, S. (2010). Beyond belief: Linking faiths and protected areas to support biodiversity conservation. Retrieved from http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:238018

- Hsu, E. (2010). Quing hao (Herba Artemisae annuae) in the Chinese materia medica. In E. Hsu & S. Harris (Eds.), Health and healing on the interface of ethnobotany and medical anthropology (pp. 83–130). New York, NY: Beghahn Books.

- Igoe, J. (2004). Conservation and globalization: A study of the national parks and indigenous communities from East Africa to South Dakota. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth.

- Ingold, T. (1992). Culture and the perception of the environment. In E. Croll & D. Parkin (Eds.), Bush base: Forest farm culture, environment and development (pp. 39–57). London: Rutledge.

- Johnston, A. M. (2006). Is the sacred for sale? Tourism and indigenous peoples. London: Earthscan.

- Keesing, R. M. (1981). Cultural anthropology: A contemporary perspective (2Rev ed.). New York, NY: Thomson Learning.

- Kumo, W. L. (2009, May 10). The Sidama people of Africa: An overview of history, culture and economy: Part I. Retrieved from http://worancha.blogspot.co.uk/2013/02/the-sidama-people-of-africa-overview-of.html

- Loh, J., & Harmon, D. (2014). Biocultural diversity threatened species, endangered languages. Retrieved from http://biocultural.webeden.co.uk

- Maffi, L., & Woodley, E. (2010). Biocultural diversity conservation: A global sourcebook. London, UK: Earthscan.

- Marcus, H. G. (1994). A history of Ethiopia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Massey, A., Bhagwat, S., & Minnis, K. (2014). Religious Forest Sites. Retrieved from Biodiversity Institute website http://www.biodiversity.ox.ac.uk/researchthemes/biodiversity-beyond-protected-areas/religious-forest-sites/

- Munro-Hay, S. (2002). Ethiopia, the unknown land: A cultural and historical guide. London: I.B.Tauris.

- Nabhan, G. P., Pynes, P., & Joe, T. (2002). Where biological and cultural diversity converge: safeguarding endemic species and language in the colorado Plateau. In J. R. Stepp, F. S. Wyndham, & R. K. Zarger (Eds.), Ethnobiology and cultural diversity (pp. 60–71). Athens, Georgia: The International Society of Ethnobiology.

- Nazarea, V. D. (Ed.). (1999). Ethnoecology: Situated knowledge/located lives. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Nazarea, V. D. (2006). Local knowledge and memory in biodiversity conservation. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35(1), 317–335. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.35.081705.123252

- Negash, L. (2010). A selection of Ethiopia’s indigenous trees: Biology, uses and propagation techniques. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University Press.

- Pankhurst, R. (1995). A social history of Ethiopia: The Northern and Central Highlands from early medieval times to the rise of emperor T Ewodros II (1st American ed.). Trenton, NJ: Red Sea Press,U.S.

- Park, C. C. (1994). Sacred worlds: An introduction to geography and religion. London, UK: Routledge.

- Pennacchio, M., Jefferson, L., & Havens, K. (2010). Uses and abuses of plant-derived smoke: Its ethnobotany as hallucinogen, perfume, incense, and medicine. New York, NY: OUP USA.

- Posey, D. A. (1999). Introduction: Culture and nature—the inextricable link. In D. A. Posey (Ed.), Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity (pp. 1–18). Nairobi: United Nations Environment Program.

- Rao, R. R. (2002). tribal wisdom and conservation of biological diversity: The Indian scenario. In J. R. Stepp, F. S. Wyndham, & R. K. Zarger (Eds.), Ethnobiology and biocultural diversity: Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Ethnobiology. Athens, GA: International Society of Ethnobiology : Distributed by the University of Georgia Press.

- Rival, L. (1998). The social life of trees: Anthropological perspectives on tree symbolism. Oxford, UK: Berg 3PL.

- Schultes, R. E., & Raffauf, R. F. (1992). Vine of the soul: Medicine men, their plants and rituals in the Colombian Amazonia. Oracle, Arizona: Synergetic Press Inc.,U.S.

- Sheridan, M. J., & Nyamweru, C. (2008). African sacred groves: Ecological dynamics and social change, 200. Athens: London: Ohio University Press.

- Shiva, V. (1998). Biopiracy: The plunder of nature and knowledge. London, UK: The Gaya Foundation.

- Siebert, U. (2008). Are sacred forests in northern benin ’traditional consevation areas? Examples from the bassila region. In M. J. Sheridan & C. Nyamweru (Eds.), African sacred groves: Ecological dynamics and social change (pp. 164–178). Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Sponel, L. E. (2001). Do anthropologists need religion, and vice versa?: Adventures and dangers in spiritual ecology. In C. L. Crumley (Ed.), New directions in anthropology and environment: Intersections (pp. 177–200). Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Sponsel, L. E. (2008). Spiritual ecology, sacred places, and biodiversity conservation. Retrieved from http://www.eoearth.org/view/article/51cbeecf7896bb431f69a6f4

- Sponsel, L. E. (2012). Spiritual ecology: A quiet revolution. Santa Barbara: Praeger Publishers Inc.

- Sponsel, L. E. (2016). Spiritual ecology, sacred places, and biodiversity conservation. Routledge Handbook of Environmental Anthropology. doi:10.4324/9781315768946.ch11

- Stanley, S. (1966). The political system of the Sidama. In The proceedings of the third inter-national conerence on Ethiopian Studies: Vol. III. Addis Ababa.

- Tekile, M., Tsegay, Z., Dingato, G. G., Garsamo, D., & Bada, B. (2012). The history and culture of the Sidama Nation. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Sidama Zone Culture, Tourism & Government Communication Affairs Department, Hawassa.

- Ukpong, J. S. (1983). The problem of god and sacrifice in African traditional religion. Journal of Religion in Africa, 14(3), 187–203. doi:10.2307/1594914

- van der Lans, J., Kemper, F., Nijsten, C., & Rooijackers, M. (2000). Religion, social cohesion and subjective well-being: An empirical study among Muslim youngsters in The Netherlands. Archiv Für Religionspsychologie/Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 23, 29–40. doi:10.1163/157361200X00041

- Vaughan, S. (2003). Ethnicity and power in Ethiopia ( PhD Dissertation). The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved from https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/1842/605/2/vaughanphd.pdf

- Verschuuren, B. (2010). Sacred natural sites: Conserving nature and culture. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/5990541/Sacred_Natural_Sites_Conserving_Nature_and_Culture

- von Heland, J., & Folke, C. (2014). A social contract with the ancestors—Culture and ecosystem services in southern Madagascar. Global Environmental Change, 24, 251–264. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.11.003

- Wansamo, K. (2014). Introduction to Sidama religion. Retrieved from http://www.afrikaworld.net/afrel/sidama.htm

- Yilma, K. (2013). Zonal diagnosis and intervention plan Sidama zone, SNNP Region. Retrieved from The Livestock and Irrigation Value chains for Ethiopian Smallholders (LIVES) website http://lives-ethiopia.wikispaces.com/file/view/Sidama+zonal+report-+final.pdf

- Zewde, B. (2001). A history of modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991: Updated and revised edition (2nd Revised ed.). Oxford, England: James Currey.