Abstract

Agro-silvo-pastoral productions occupy an important place in the economy of Niger. Agricultural activities, however, take place in difficult conditions, which intensifies the issue of gender inequality. In the regions of Maradi and Zinder, this inequality stems from a set of factors that disadvantage women. Yet, women contribute over 50% to meeting the household’s food needs in Niger. It is therefore important to question what are the initiatives facilitating women’s access to and control of land. Thus, one of the main challenges to women’s progress remains access to land. This article analyzes women’s access to land-related strategies in the regions of Maradi and Zinder. Two villages in the region of Maradi (Dan Dadi and Foura Guirké) and two others in the Zinder region (Garin Tamdji and Kaouri Touareg) served as data collection sites. The qualitative method was the one used in data collection (through the semi-structured interviews) as well as in their analysis (through triangulation). The outcome of the study provided results that indicate that socio-cultural constraints limit the initiatives developed to promote women’s access to land. Thus, the sustainability of the control of land by woman passes through a community solution and on the basis of a consensus that will have a guarantee from the customary and administrative authorities to give it a certain legitimacy.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In rural Niger, the land use system is characterized by the existence of the collective fields and individual fields belonging to women and young people. But today, due to population growth, climatic and socio-cultural constraints, women are struggling to access and, better, to control their land resources. However, it is recognized that they participate in agricultural production and that most of their products are intended to meet the needs of households. Faced with this trend towards the defeminization of agriculture, initiatives aimed at promoting women’s access to and control over land are being developed by many actors. However, their robustness depends on the deposit it receives from the community and local authorities.

1. Introduction

The regions of Maradi and Zinder are among the most densely populated in Niger with densities of 84.7 and 23.5 inhabitants per km2 respectively (Institut National de la Statistique [INS], Citation2015a, Citation2015b). They have a land use rate of around 36.3% according to the results of the general census of agriculture and livestock (République du Niger, Projet GCP/NER/041/EC, Citation2007). This phenomenon is gaining momentum with population growth, the average rates of which are 3.7% for Maradi and 4.7% for Zinder in 2012, (RGP/H, 2012). This situation causes a doubling of the population in less than 20 years; besides, the fertility rate stands at 8.4 children per woman in Maradi and 8.5 in Zinder (INS, Citation2015a, Citation2015b). The demographic weight generates strong pressure, accentuating the fragmentation of agricultural land and the development of a multitude of land transactions. The lifestyles of the rural population are characterized by the existence of socio-economic differentiations between farms, corresponding in particular to an inequality in the access and management of natural resources, particularly land.

This inequality is fueled by the persistence of customary rules and the pre-eminence of men’s decision-making power over land access and control.

In addition, the Economic and Social Development plan (PDES 2017–2021) adopted by the Government of Niger, is part of its third strategic axis “Acceleration of economic growth and transformation of the rural world”, promotion of women’s economic opportunities and reduction of inequity and inequality between gender. The notion of gender picks up the specificity of socially constructed relationships between the two sexes (Droy, Dubois, Rasolofo, & Andrianjaka, Citation2001). The PDES defines and frames sectoral policies in the implementation of actions in favor of gender. It is fully in line with the Global Action Plan for Women’s Decade adopted in 1975 by 100 nations in Mexico City, one of the main themes of which is “the integration of women into economic development” (Droy, Citation1985). In spite of this, it is now settling in these regions, new land changes that further entrench women’s insecurity. So, what are the factors of women’s land insecurity in these areas and the strategies developed to address them? This article has a dual purpose.

analyze the factors of land insecurity for women in the regions of Maradi and Zinder;

analyze the strategies developed for women to access and control land in the regions of Maradi and Zinder.

Composed at 80% of peasants, the population of these regions practices mainly agriculture. However, agricultural activities are nevertheless taking place in difficult conditions, characterized by climatic uncertainties and soil fragility. Indeed, with the exception of a few pastoral enclaves and uncultivated areas unsuitable for agriculture, all the land is subject to continuous agricultural exploitation with the disappearance of fallow land. Some authors describe it as a “blocked agrarian system” (Raynaut, 1975 quoted by Diarra & Monimart, Citation2006). This difficulty explains to a large extent the elements of physical and socio-economic crisis that these regions are experiencing. Land crisis is reflected in the high level of crumbling cropland, particularly in Maradi region. Indeed, nearly 72% of farms have less than two hectares of low-productivity dune land. In fact, this situation is general in practically the entire agricultural zone of the two regions (Yamba, Citation2017). Productive activities are dominated by men who decide on the use of productive and reproductive resources. As a result, even if these resources belong to the woman, she cannot use them at her convenience. The land issue at the level of the study areas is characterized by several constraints whose negative repercussions on the living conditions of the rural populations are important. Worse, the environmental changes lead to a significant decrease of agro-silvo-pastoral productions. As a result, the food insecurity of rural households is worsening and the issues related to productive resources are more important than ever. The fragmentation of the farms thus operated destroys the economic viability of most of the production units, which are now engaged in a process of individualization of relations with production.

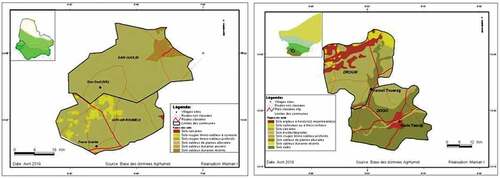

In the region of Maradi (Figure ), the sites of Foura Guirké and Dan Dady are located in an area with fossil valleys whose flows are temporary (Goulbi) and where market gardening is practiced. In addition, Garim Tamdji and Kaouri Touareg (Zinder region) are located in an area where there are wet basins and dune and silty-clay soils generally for off-season crops. From an agroecological point of view, the municipalities of Dogo (Zinder region) and Guidan Roumdji (Maradi region) are located in the Sahelo-Sudan zone. Those of Droum (Zinder region) and Dan Goulbi (Maradi region) are located on both sides of the Sahelo-Sudan and Sahelian zone. In these areas, in addition to agriculture, women carry out various economic activities: small livestock, processing and marketing of agricultural products. Income from these activities, although low and oriented towards a logic of social security, often constitute levers of access to land resources.

This study aims to elucidate the main women’s constraints of access to agricultural land in the study region. Then, it highlights the different strategies developed with a view to improving access conditions and control of land by women. It reveals that individual strategies are in most cases obsolete. So, to avoid a silent defeminization of agriculture, despite the important role that women play in meeting household food needs, strategies (community and exogenous) must be supported by the community and strongly supported by the local authorities (customary and administrative).

The main factors of land tenure insecurity for women involve the weight of tradition, population growth and increase in livestock and climate change and variability. Traditionally, the activities which require significant physical effort have been mainly devoted to men. Also, if due to the virilocality principle (Diarra & Monimart, Citation2006), the woman who moves too far from the village, through marriage, loses all rights on the land (Droy, Citation1985), then the stability of her marriage constitutes, a key factor that determines her access to land during the union (Issoufou, Citation2008). Population growth, increased livestock and climate change and variability have resulted in strong pressures on natural resources (Dambo, Citation2017). Their combined effect is a factor of the relative scarcity of land. In most cases, this leads to the plot of land withdrawal exploited by woman. Consequently, it is witnessing a reduction in tenure security for non-owner operators (Hesseling, Citation1994), particularly women.

Women are relied on their men because of their non access to the land and productive resources. Also, it influences their access to complementary resources such as credit (Adamou, Citation2008). This situation increases the economic and social inequalities that penalize women (Adamou, Citation2008). In addition, women’s non-access to land leads to their low or non-participation in the fulfillment of food and especially the nutritional needs of households because the products they cultivate are mainly geared towards them. Ultimately, the women’s insecurity of tenure facilitates their eviction from access and control of the land. Consequently, this leads to the defeminization of agriculture, the corollary of which remains the feminization of poverty on the economic, social and decision-making levels (Diarra & Monimart, Citation2006).

Customary law ensures the rights of women to access land through the “gamana” system. However, their difficulties in accessing land are due to the traditional distribution of social roles; the main role attributed to women being that of reproduction. Due to land saturation, lands allocated to them are the most marginal, which productive activities could not be carried out with good yields (Adamou, Citation2008). As a result, customary law limits women’s land ownership, which means that “the situation of women with access to land ownership is not significant” (Ali, Citation2008).

Regarding economic view, ownership of the land permits women to accumulate their own capital (livestock) which they can mobilize when needed. From a social point of view, marriage is one of the ways in which women have access to the land. However, in the event of a divorce, they are deprived of land parcel which they value. The opportunity they obtain with land ownership relates to the security providing them in a context of marital instability where, overnight, they may find themselves destitute through divorce (Droy, Citation1985).

2. Methodological approach

2.1. Choice of the qualitative approach

To conduct the study, the qualitative approach was chosen. It favors individual or group semi-structured interviews through focus groups. Thus, these interviews concerned several actors and stakeholder groups, namely producers, customary and religious authorities, agents of development projects and technical services, members of land commissions and members of peasant organizations. The interview guide, designed for this purpose, focused on the real land situation of women as well as their strategies to access and control land. In addition, obstacles and opportunities in terms of women’s access to and control over land were discussed. Direct observation has also been used systematically for data collection. It focused on the position of women’s plots (whether plots for irrigated or rainfed crops) on the topo-sequence. This participatory approach is chosen because it allows, on the one hand to collect information concerning the land situation in the study area, the situation of access to and control of land by women in terms of facts and practices; on the other hand, it also makes it possible to grasp the perception of the actors questioned on the land situation of women in the regions of Maradi and Zinder. The technique of direct observation in the field facilitates the analysis of social uses of space and social interactions in space. As part of this study, it allowed us to discover that, in most cases, women only access marginal land, which is not very fertile, therefore requiring significant investment, as is the case in Garin. Tamdji (Figure ). Also, direct observation in the field was an opportunity to discover the level of land crumbling and land saturation (Figure ) in the study area. The entry on the field was made on the basis of the choice of site villages. This choice takes into account ethnic and cultural diversity as well as the nature of agrosystems in both regions.

2.2. Data collection

The data collection was carried out among various actors mentioned above. Thus, eight (08) focus groups, twenty-nine (29) individual interviews and four (4) field visits were organized.

The focus groups, focused on the legal and cultural context of land access and control, took place with four (04) groups of women and with the same number of groups of men. This is indeed a focus group by a group of actors and village site. In addition, sixteen (16) individual interviews were conducted with women, four (4) per village site. It should be noted that in each village site, two (2) interviews were held with women having control over the land and the same with those having no control over the land (Table ).

Table 1. Data collection techniques

In order to triangulate the data collected on the field, in-depth individual interviews, thirteen (13), were conducted to gather the opinions of the strategic groups. These data complete those collected with women through individual interviews. It should be remembered that the strategic groups are composed of project and technical services agents, customary and religious authorities, members of producer organizations and members of land commissions. In addition, at the spatial level, the scales vary from the local to the regional level, passing through the municipal and district levels.

In addition to all of the techniques mobilized and previously described, the direct observation technique served as a back-up in the constitution of the field data. In both regions, four (4) sites were visited. These visits allowed the description of the sites of Garin Tamdji and Kaouri Touareg (Zinder region) and those of Bakoussomouba and Foura Guirké (Maradi region). Besides, geographical coordinates and photos of some irrigated plots of women were taken. It should be noted that the Bakoussomouba site was visited because it is an example of success in terms of women’s access to land in Maradi region.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Modes of access to agricultural land

Niger’s rural land is governed by a variety of modes of access of varying importance depending on the village. In the study area, the main modes of access are inheritance, gift, loan, purchase, rental and pawning.

Inheritance is a mode of access to land that occurs following the death of the woman’s father or husband. But nowadays, women are more and more rarely accessing this mode of access since they are supposed to belong to another family after their marriage. These results corroborate those of Ouedrago (Citation2013) for whom, the rule generally applied in the customary system, is based on land locking for the benefit of the patrilineal way, with the aim of preserving the family patrimony. But Islamization has introduced profound changes in the land control by women, recognizing women’s right to inherit land. According to a religious leader of Garin Tamdji, “the sharing of the inheritance is done according to the Koranic prescriptions which grant to the male child 2/3 of the land capital and that of the female sex 1/3. Moreover, when a woman loses her husband, she receives the eighth (1/8) of the inheritance, the rest is distributed among her children whatever their number “. But in fact, sharing is usually done under the strong influence of men with the aim of avoiding that the family patrimony is diverted to the benefit of the woman’s family in-law or a third person (in the case of sale). These results confirm those of Charlier, Diop, and Lopez (Citation2016) according to which traditional customary systems are rarely favorable to women and generally favor men’s access to land.

The concern to preserve the family patrimony does not, however, lead to the exclusion of women from land. She accesses it, among other ways by donation that consists of the fact that a landlord gives for free without any consideration a part or totality of a farm to another person or a group of people. The gift is usually made on an individual basis. In the case of the married woman, it is rather a provision, especially by the husband. The access of women to land by donation deserves to be nuanced, since in some localities of Maradi region, it intervenes only after the woman has given birth a second time. According to the respondents, in the event of divorce or death of the husband, the given land is returned to the family patrimony (Cotula, Toulmin, & Hesse, Citation2004). Besides, with land saturation, the donation is becoming increasingly rare, says a woman from the village of Kaouri Touareg. She reports that “My husband has only one farm, I asked him for a piece, he opposed me a categorical refusal with as an explanation the narrowness of the field”.

Although more and more rare, like the donation, the loan is a mode of access to land still in force in the villages studied. It consists in giving a piece of land to another person (men or women) for a fixed period. As far as women are concerned, the duration of the loan is relatively short, even if exceptional cases exist. To this end, a woman from Dan Dady’s village reports “when I divorced from my husband and, so as not to get away from my two children, I asked for a piece of land from the chief of the village that I put in value in order to support them until their maturity […] “. It should be noted, however, that individual loans, especially for women, are rare.

Land saturation, limiting access to land by other social forms of access (gift and loan), makes land a merchant property. It’s getting more and more expensive. For this purpose, women gain access to land through purchase. This monetarization of the land was highlighted by Dambo (Citation2016) in the Dosso region where it is the valley lands, therefore the most fertile, which are particularly concerned. In theory, the presence of a land market can facilitate land access to everyone, including women, and end their marginalization (Moussa, Citation2007). Thus, in the transactions involving them, they are most often represented by their husbands or brothers to whom the task of negotiating prices comes back. As a result, they vouch for the transaction that allowed the woman to access and/or control the land. However, Ubink and Amanor (Citation2008) note that the increasing commercialization of land is undermining women’s rights to land. This could be related to the rising cost of land and the level of poverty in rural areas. Not all rural women are given access by this mode (Daniel & Keith, Citation1998), but rather by renting or pawning.

Access to land being difficult or even impossible because of the social forms of access and purchase due, respectively, to land saturation and poverty, land renting increases in size. This mode of access consists of an owner assigning to another person or a group of persons a piece of land for an amount agreed between the two parties. Its duration is not too long and is renewable.

Unlike renting, the duration of the pawning can be longer or shorter. It even happens that it evolves on sale. It consists of having an owner put a piece of land at the disposal of a person in return for a sum of money that he estimates to be returned at any time according to the opportunities available to them. The pledge is an opportunity for women to become land owners. Generally, the person who pawns his land, when he decides to sell it, first informs the woman with whom he is in a pledge. If she is interested, she simply completes the rest of the money says a woman of Dan Dady in these terms: “My husband is not native to this village; he had therefore not inherited land and was exploiting only a piece of land loaned to him. After the withdrawal of the field, we took a pledge at 20,000 FCFA. After three years of contract, the owner finally gave us the field at 80,000 FCFA. This example demonstrates, if need be, the capacity of local actors, particularly women, to adapt to the context of land pressure.

All these elements mentioned above reveal, the increasing difficulty of women in accessing agricultural land through social forms of access in the study area. The access by the purchase being limited by their level of poverty, the women access and control the land due to the hiring and the pledge on condition that they access to information about the transaction by the land advertising.

3.2. Constraints of access and control of land by women

As a production base, land represents a source of security and social prestige for the peasant. It is a gain inherited. The various transactions to which it is subject are also modes of access. In the regions of Maradi and Zinder, as elsewhere in Africa, its access is governed by different modes, both legally and culturally (Cotula et al., Citation2004; Daniel & Keith, Citation1998; Ubink & Amanor, Citation2008). However, from the legal or cultural point of view, various constraints limit women’s access to and control over land. They can be economic, social (Oumarou & Dambo, Citation2017) and institutional (Institut National de la Statistique/United Nations Development Program [INS/UNDP], Citation2012; Lawali, Mormont, & Yamba, Citation2014).

In both regions, the land structure and organization of production within the domestic unit are very similar. From this point of view, we distinguish the collective field “gandou” and the individual plots “gamana”. The “gandou” corresponds to all lands cultivated collectively by a household. All members of this production unit participate in the agricultural production (Guengant and Banoin, Citation2003) and consume these goods under the responsibility of the head of the household unit to whom the agrarian decisions are returned. In terms of use and consumption of production, responsibilities are shared with a key role for women. They excel in the processing of agroforestry and pastoral products. The “gamana” is a plot of land allocated to lower-level domestic units, including women living under the supervision of the head of the household unit. The maintenance and products belong to the person who works on them (Guengant and Banoin, Citation2003). Today, this gift of land is becoming scarce in the area because of land saturation (Figure ), which impacts on women’s access to land, a local practice once accepted by all. If in the past, traditional regimes have protected women’s rights to work and manage enough land, these rights have been eroded by a number of factors including changing socio-economic conditions and land scarcity (FAO, 2002 cited by Klaus, Citation2006). Thus, we are witnessing an attempt to silently exclude women from access to and control of land in spite of the fact that in many developing countries women produce most of the food consumed by their families and communities (Klaus, Citation2006), and they are therefore the key to food security (Quisumbing, 1995 cited by Klaus, Citation2006). This silent exclusion of women from access to and control of land has important social and food security implications for households. In fact, on the social level, the migrations of women are a perfect illustration of this. From a food security perspective, the repercussions are reflected in the malnutrition of children.

Figure 2. Land saturation at Kaouri Touareg: absence of fallow and excessive crumbling of land

From the socio-cultural point of view, the laborious work including farming is mainly done by men that assure the family’s protection and care. Thus, a farmer who wants to show his social success spares his wife from fieldwork as illustrated by this testimony collected during a focus group with men in Kaouri Touareg: “As soon as she gets married, the woman is supported by her husband. She does not have to work the land to support herself. That’s why men do not care much about giving women land to cultivate. “ Besides, some women are denied their share of inheritance in the name of the virilocality principle (Diarra & Monimart, Citation2006). The testimony of a woman from the village of Dan Dady confirms this perception: “[…] following the death of our father, my elder half-brother refused to give me my share of inheritance, asking me to report to court if necessary. To pose this act is contrary to the social values, which forced me to give up my right “. This is a perfect illustration of an attempt to oust the women from access and control of land. These results fit well with those of Doka and Monimarthe, (2004) cited by Lawali et al. (Citation2014) according to which, the mechanism of locking in of land rights by refusing to share inheritance, the misappropriation of land rights of women are all factors that favor discrimination and the crowding out of vulnerable groups from access to land.

It is also important to note that some religious considerations leave little chance for the woman to access the land. These include confinement (Diarra & Monimart, Citation2006), which confines the woman to a small family space that prevents her from leaving home during the day. In this sense, a religious leader in the village of Garin Tamdji expresses himself in these terms: “Women must not leave the house without valid reasons or without fulfilling certain conditions. To leave the house under the gaze of men is to commit a sin. In this case, women must stay at home and be cared for by men”. According to this conception, women are not allowed to engage in any activity outside their compounds. And, the same religious leader to add that “men who let women work land do not know what they do, a woman must not practice irrigated crops alongside men while exposing her body […] “. These religious considerations constitute a real limit to women’s access to and control of land. These results align perfectly with those of Diarra and Monimart (Citation2006) for whom religion serves as a cover for the total exclusion of women from the land. In view of the above, everything suggests that traditional customary systems are rarely favorable to women’s access to land (Charlier et al., Citation2016).

Finally, another constraint that women face is the agricultural fitness of the land allocated to them, if they happen to get it. Field investigations have shown that the plots allocated to them are generally marginal (Cotula et al., Citation2004) and poor (Figure ). This figure that reproduces the landscape of the Garin Tamdji site, locates the market gardening plots of women at the level of the low glacis. Pedologically this landscape unit has medium-quality soils compared to those occupied by men and located on the terraces of the river. These results align perfectly with those of Virginie, Andrew, and Emily (Citation2015) according to which women cultivate household-oriented products on land that is often less fertile.

Figure 3. Location of women’s market gardening lands in Garin Tamdji

Land as a primary resource for rural populations, its ownership is therefore an important issue. Aware of the challenges around this resource, it appeared necessary for the State of Niger to change the legal framework in terms of land management, namely the country’s rural one. A traditional land tenure review process got initiated. Thus, the ad hoc law (law 60–28 of 1960) was promulgated at the end of the colonial period. Subsequently, it has been amended and supplemented several times, including Ordinance 93–015 of 1993 establishing the Orientation Principles of the Rural Code and Ordinance 2010/29 of 2010 on Pastoralism. It advocates equity in access to natural resources. Thus, the ordinance 93–015 of 1993, in its Article 4, stipulates that: “rural natural resources are part of the common heritage of the Nation. All Nigeriens have an equal vocation to access it without discrimination of sex or social origin “. In order to put this into practice and ensure better management of rural land, the State creates the Land Commission (CoFo) and determines its composition through article 118 of the above-mentioned ordinance. The “CoFo is a framework for consultation, reflection and decision-making on natural resource management and conflict prevention”. However, wishing to take into account the traditional legislation, the rural code has locked itself into a contradiction. The formal law says that men and women have the same right of access to land. The Islamic law states that in the case of inheritance the woman receives 1/3 or 1/8 depending on whether she inherits from her father or husband. This situation is consistent with that recalled by Klaus (Citation2006) indicating that women often have only limited access to land. Thus, the situation of women with access to land ownership is insignificant, despite the favorable provisions reserved for it by Koranic law and civil law in this area (Najros, Citation2008).

Thought for a better management of natural resources, the land commissions (CoFo) would no doubt ensure these missions had it not been for the non-completion of the process of their implementation and the operating difficulties that most of them face. The difficulties of operation are related to the lack of material and human resources. From a human point of view, the shortage of support staff and the predominance of volunteer staff that lack adequate training in establishing land transaction documents, are the main constraint of CoFo in the study area, especially in the region of Zinder. In terms of equipment, this includes the lack of working tools such as GPS receivers for land registry and logistical means for travel. Added to this is the need for training in their use. In addition, some actors (customary chiefs), especially in the Zinder region, see these structures as a counter power of their secular authority; they feel no enthusiasm to make them work. Moreover, the persistence of the issuance of non-formal land transaction documents by some traditional chiefs, in the form of “small paper” are other obstacles to the proper functioning of these structures. Apart from these weaknesses related to the functionality of CoFo, technical gaps remain. Field investigations have revealed that there is a real problem of information management, so that women are little or not at all informed about the content of the rural code and the role that these institutions could play in terms of land security. This situation is much more worrying in Zinder because of the difficulties faced by the land commissions of the region. But these operating difficulties are not unique to the CoFo of the regions of Maradi and Zinder, the same difficulties were also noted by Dambo (Citation2017) for the CoFo of the region of Dosso. When they are put in place and functional, it is largely thanks to the necessary support provided to them by the development partners. In this context, how could they do their job properly?

3.3. Access and control strategies

The different modes of access to the land exposed, show the limits of the control of the land by the woman. Women seldom safely hold the land they work on (Klaus, Citation2006). They own only 1% to 2% of agricultural land in Developing Countries (PED) (FAO, 2010 cited by Robert, Citation2011). Yet, agricultural development requires women’s investment in production and therefore their control of land. To this end, various strategies are developed by various actors. These strategies can be classified into three categories: individual, community and exogenous.

3.3.1. Individual strategies

They relate to income-generating activities practiced by women. This is the tontine and the fattening, to which are added bank loans and money transfer. Women gain access to land through the financial resources mobilized through these activities. To this end, various testimonies were collected regarding the role played by these activities for women’s access to and control over land.

The tontine consists of a periodic contribution. It enables women to mobilize financial resources, which enable them to access land through purchase and pledge. To this end, a woman member of the “Némi Naka” group of Garin Tamdji tells us this: “We are thirty in our group and each week we collect 6,000 FCFA. At the end of each month the total is paid to one of the members. When I received my payment of 24,000 F, I gave a fee to access the small piece of land that I have been operating for five years now. This is also the case in the region of Maradi as shown by the testimony of a resident of Dan Gado: “the pledge allowed me to have my own land. With my participation in the tontine, I was able to buy a land. Initially, it was a pledge contract that bound me to the owner of the field. Then he asked me for another sum of money. In the end, he finally gave me the field in question. “

Fattening (ovine and bovine) is one of the Income Generating Activities [AGR] regularly practiced by women in the sites studied. It consists of fattening an animal in order to enhance its market value. To this end, a woman from Kaouri Touareg says this: “… the bull that I fattened was sold at 265,500 FCFA. This sum allowed me to repay my debts and buy a piece of land at 230,000 FCFA”. The practice of these AGRs facilitates access to bank loans for women from microfinance institutions.

Low interest rate bank loans strengthen the financing capacity of AGRs. These are often projects that accompany these structures by guaranteeing the sums lent, as explained by the Gender officer of Zinder’s Family Farming Development Project (PRODAF): “In the context of our interventions, we finance activities in a shared cost. To this end, we are guiding women and women’s organizations to financial institutions with a share of the guarantee. We have conventions with ASUSU and BAGRI “.

Money transfer is another source of AGRs funding. It is carried out by a member of a household to the benefit of the latter. In this case, altruism remains the one and only motivating reason (Maman et al., Citation2015). When properly managed, it allows the household to come true. To this end, a woman from Foura Guirké describes her situation as follows: “… the transfers made by my two sons settled in Lagos (Nigeria) allowed me to acquire a piece of land worth 355,000 FCFA “.

All these strategies participate in the acquisition of agricultural land to the benefit of women but in a timid manner. Indeed, they do not allow a large number of women to access land, which gives them a small visible aspect.

These strategies participate in the acquisition of agricultural land for women benefit, but in a timid manner. Indeed, they do not allow a large number of women to access and control land, which gives these strategies an invisible character. Their impact on access to and control of land on account of women are less. These results confirm the assertion of FAO (2010), cited by Robert (Citation2011), that women own only 1% to 2% of agricultural land in developing countries.

3.3.2. Community strategies

Given the timidity and lack of visibility of individual strategies, and in order to allow a large number of women to access and control agricultural land, community strategies are developing. This is the “Gayamna/Gamana, land renting and the regrouping of women in associative movement.

To allow women and young people to access to land, households allocate a piece of land to them. Commonly called “Gayamna” or “Gamana”, it consists of the provision of a piece of land. It may come from the woman’s father, husband or father-in-law (Burnet and Rwanda Initiative for Sustainable Development, Citation2003; Cotula et al., Citation2004; Daniel & Keith, Citation1998). However, the woman may lose this right to use in case of divorce or following the death of her husband (Cotula et al., Citation2004). In any case, this provision is most often conditioned by the availability of land. Also, the rights exercised by women on this plot are quite limited.

Access to land through the system of “Gayamna” is becoming increasingly rare due to land insufficiency; some heads of households rent land for the benefit of their women. Much more developed in the region of Zinder than in that of Maradi, this access strategy offers no guarantee in the same way as the “Gayamna”. Indeed, the husband may decide to terminate the contract.

The sustainability of these strategies being unsatisfactory, in a context of land saturation, women are organized into an associative group; another strategy that allows them to access to land. These associative movements, although impelled from the outside, remain a community initiative. This approach seems to be the most appropriate way to allow women to access and have control over land. These movements make them essential actors in the life of their community. Indeed, they are involved in all community management structures, particularly in the monitoring and evaluation committees of the activities implemented by the projects. One of the positive effects is the speaking in village assembly and in the mixed meetings. This gives the woman a negotiating power, which is indispensable for defending her material interests.

These strategies, developed at the community level, allow women access to land without any discrimination, in particular through the Gayamna/Gamana system and grouping in associations. However, since they are not very diversified, it is appropriate that they be promoted by external actors to those communities by facilitating local conventions. This confirms the assertions of Moussa (Citation2007) for whom, these local conventions, when properly conducted, take into account the rights of all users, including marginalized groups like women.

3.3.3. Exogenous strategies

Given the trend towards the de-feminization of agriculture whose corollary remains the feminization of poverty, in the broad sense of the word: economic, social, decision-making (Diarra & Monimart, Citation2006), strategies are carried by partners intervening in favor of women’s access to land. Increasingly, these partners advocate greater feminization of agriculture by accompanying organized women. Their interventions focus on crops (rainfed and gardening), but with more emphasis on gardening. In order to facilitate women’s access to and control of land, several activities are carried out. These include capacity building, support for land acquisition and agricultural development.

Capacity building for rural producers consists of training producers (women and men) on crop techniques. It is done through the field peasant schools. Indeed, gardening requires a minimum of know-how. This is why the partners intervene in capacity building through the organization of the field schools. Their modalities consist of acquiring land (loan, donation or purchase) to the benefit of the members of this field peasant school and respecting the quota for women (30% of the workforce). Thanks to this modality, some women return to agricultural activities because they arouse their will to practice gardening.

In terms of support for access and land acquisition, various activities are carried out by external actors to support women. As such, we can mention the work of recovery of degraded land and fattening.

In response to the problem of land degradation, external partners intervene to restore degraded resources through land recovery works. Following this work to recover degraded lands, women are being supported to access these recovered lands. To this end, a Zinder REGIS-ER project officer states: “With the conservation culture mechanism (BDL), women have been able to access the land. It is in fact to recover the degraded lands and make them available to women’s groups according to the terms of a loan. These women grow rain-fed sorrel, okra, and so on. “

Fattening is another strategy developed by partners to improve women’s access to and control of land. It consists of a kit, composed of three goats and a he-goat given to a woman. The latter passes the said kit to another woman after fifteen (15) months. The births made during this period come back to her. These animals constitute a kind of savings on foot, easily mobilizable in case of need of acquisition of a plot of land.

The partners’ interventions in terms of improving women’s access to land are fundamentally oriented towards communication, information, mobilization and advocacy (FAO Citation2008) and the development of acquired sites. The development involves the sinking of wells, fence making, the acquisition and installation of irrigation systems (Figure ). This is in fact a huge investment that is beyond the reach of the majority of women in rural areas where the poverty rate was 65.7% in rural areas (République du Niger, Citation2007). Given these difficulties, external actors specifically support women organized in groups. When the land is acquired, these external actors facilitate the establishment of land transactions to secure the land. Once this stage is completed, follow the other interventions (landscaping and equipment in California network).

Figure 4. Foura Guirké’s women gardening site, realized by a partner

This is the example of the village of Bakoussomouba (district of Guidan Roumdji) whose women have benefited from USAID’s intervention through the NGOs Save the Children and World Vision. In addition, these partners support women in agricultural inputs and train them in Zai, a water and soil conservation technique. This is the case in the villages of Dan Dady and Dan Gado in the region of Maradi. Admittedly, this made it possible to practice rain-fed agriculture by several women. But it should be remembered that access to land is difficult for women without the intervention of these actors, especially for market gardening. However, external actors see their impetus for improving women’s access and control of land, which is often slowed by a number of constraints. The latter reside in the fact that women only have access to marginal lands (Figure ) that require significant investment on the one hand, and their low level of education makes them less receptive to innovation. To overcome these constraints, all the actors intervening in the field must work to the benefit of the evolution of mentalities in favor of: (1) women’s access to land and (2) recognition by law and habits and customs of the status of women as farmers (Bureau de la Coopération Suisse à Bamako, Citation2013).

4. Conclusion

It is clear that the ways in which women can access land are varied. But with land saturation in relation to population growth, women’s access to land through inheritance and especially donation is becoming increasingly rare. Moreover, when she manages to access it, particularly through the provision of a piece of land by her husband, she usually does not exercise any control. Indeed, no act of transaction is established for this purpose. This makes precarious woman’s access to land since she is often disqualified from this land in case of divorce or death of her husband. In addition, in order to ensure sustainable control of acquired land, women make use of various possibilities, depending on the nature of the land transaction. For inheritance, purchase and pledge, formal transaction documents are established by the land commission. But, the vulnerability factors of women in action, such a development may lead to a de-feminization of agricultural activities in the near future. Indeed, because of their low purchasing power, there are few women who individually access to land through modes requiring the mobilization of financial resources. To do this, they offer themselves the possibility of associating themselves, outside of their family environment, to access a land that they use in common. This movement is encouraged and supported by partners working in the rural development sector (projects, programs and NGOs). It is thanks to their intervention that certain initiatives, favoring the access and control of land by women, are locally taken. Institutional and legal texts must advocate secure access for women to productive resources. The actors in charge of the application of these texts must work for the acceptance of these by the populations through their effective implication both in the process of their elaboration and of implementation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maman Issoufou

Dr Maman Issoufou, Dr Dambo Lawali and Pr Yamba Boubacar are teacher - researchers in the geography department of Abdou Moumouni University. Members of the Research Laboratory on Sahelo-Saharan Territories: Planning - Development, their areas of intervention include the planning of rural areas, land, climate change, GIS and resilience. They have published numerous research articles in renowned journals.

Oumarou Amadou

Dr Oumarou Amadou is a teacher - researcher in the sociology and anthropology department of the University of Niamey. His areas of specialization are the analysis of public service delivery and the dynamics of rural societies; His articles are published in international newspapers and magazines.

Dambo Lawali

Dr Ibrahim Habibou is a temporary employee in the Geography department of the University of Niamey. As land specialist, he is currently a consultant at the MCC.

Oumarou M. Saidou

Oumarou M. Saidou is a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology. Research assistant at LASDEL, his thesis work focuses on: constraints to public policies regarding floods in the city of Niamey.

References

- Adamou, M. (2008). Projet intrants. Promotion de l’utilisation des intrants agricoles par les organisations de producteurs (pp. 82–87). In Projet FAO - Dimitra (Septembre 2008). Accès à la terre en milieu rural en Afrique: stratégies de lutte contre les inégalités de genre, Bruxelles, Belgique, 166p. En ligne. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/3/ak159f/ak159f.pdf

- Ali, A. (2008). La femme rurale et le problème foncier agricole au Niger. In Projet FAO - Dimitra (Septembre 2008). Accès à la terre en milieu rural en Afrique: stratégies de lutte contre les inégalités de genre (pp. 50–15). Bruxelles, Belgique. 166p.

- Bureau de la Coopération Suisse à Bamako. (2013). Contrôle des femmes et des jeunes sur les ressources foncières agricoles: Expérience de la Coopération Suisse au Mali. Études de cas: Programme d’aménagement et de valorisation pacifique des espaces et du foncier agricole (AVAL) et programme d’appui à la promotion de l’économie locale (APEL) dans la région de Sikasso. Récupéré de https://www.eda.admin.ch/content/dam/countries/countries-content/mali/fr/resource_fr_222224.pdf

- Burnet, J. E. & Rwanda Initiative for Sustainable Development. (2003). Culture, practice, and law: Women’s access to land in Rwanda (Paper 1). Anthropology Faculty Publications. Retrieved from htt://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_facpub/1.

- Charlier, S., Diop, S. F., & Lopez, G. (2016). Les modes de gouvernance foncière au prisme d’une approche genre. Études de cas au Niger, au Sénégal et en Bolivie (pp. 4). Récupéré de http://www.landaccessforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Synth%C3%A8se_Les-modes-de-gouvernance-fonci%C3%A8re-au-prisme-dune-approche-genre-1.pdf

- Cotula, L., Toulmin, C., & Hesse, C. (2004). Land tenure and administration in Africa: Lessons of experience and emerging issues (pp. 51). London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Dambo, L. (2016). Monétarisation du foncier à Dosso: Décryptage d’une dynamique à enjeux multiples. Revue de Géographie Tropicale et d’Environnement, 2, Pp: 63–79.

- Dambo, L. (2017, Octobre). Défis d’une expérience innovante de gestion moderne du foncier à Dosso, au Niger. In Revue de Géographie de l’Université de Ouagadougou (RGO) Numéro 006 (Vol. 1, ISSN Edition numérique: 2424-7375, pp. 219–240), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

- Daniel, M., & Keith, W. (1998, January). Land tenure and food security: A review of concepts, evidence, and methods. Research paper 129 (pp. 41). Madison: Land tenure center, University of Wisconsin.

- Diarra, M., & Monimart, M. (2006). Femmes sans terre, femmes sans repères? Genre, foncier et décentralisation au Niger, IEED. Dossier no. 143 (pp. 57). Récupéré de http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/12535FIIED.pdf

- Droy, I. (1985). Femmes et projets de développement rural en Afrique sub-saharienne. Essai d’analyse a partir d’études de cas (pp. 581). Institut de recherche économique et de planification du développement. Université des sciences sociales de Grenoble.

- Droy, I., Dubois, J. L., Rasolofo, P., & Andrianjaka, N. H. (2001). Femmes et pauvreté en milieu rural: Analyse des inégalités sexuées a partir des observatoires ruraux de Madagascar (pp. 22). Retrieved from https://en.ird.fr/

- FAO & al. (2008). L’accès des femmes à la terre en Afrique de l’Ouest: Problématique et pistes de solutions au Sénégal et au Burkina Faso (p. 50). Récupéré de http://www.fao.org/dimitra

- Guengant and Banoin. (2003). Dynamique des populations, disponibilités en terres et adaptation des régimes fonciers: Le cas du Niger (pp. 144). Rome.

- Hesseling, G. (1994). La notion de la propriété rurale et des contrats d’exploitation au Niger. Comite National du Code Rural, Secrétariat Permanent, Rapport de mission (pp. 24). doi:.S0022-0302(94)77044-2

- Institut National de la Statistique. (2015a). Maradi en chiffres (pp. 2). Niamey, Niger.

- Institut National de la Statistique. (2015b). Zinder en chiffres (pp. 2). Niamey, Niger.

- Institut National de la Statistique/United Nations Development Program. (2012, Novembre). Contribution des femmes aux dépenses des ménages et à la réduction de la pauvreté à Maradi. Récupéré de http://www.undp.org/content/dam/niger/docs/Publications/UNDP-NE-RapportContributionFemmesManages.pdf

- Issoufou, O. (2008). Femmes et développement local: Analyse socioanthropologique de l’organisation foncière au Niger: Le cas de la région de Tillabéry. Sociologie. Université Rennes, 2, 356.

- Klaus, K. (Edition). (2006). Assurer la Sécurité Alimentaire et Nutritionnelle Actions visant à relever le défi global Manuel de référence. In WEnt – Internationale Weiterbildung und Entwicklung gGmbH (Renforcement des capacités et développement international) (pp. 258).

- Lawali, S., Mormont, M., & Yamba, B. (2014). Gouvernance et stratégies locales de sécurisation foncière: étude de cas de la commune rurale de Tchadoua au Niger. [VertigO] La revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement, 14(1), 14.

- Maman, I., Dambo, L., Bode, S., & Yamba, B. (2015). Impact du transfert d’argent sur la résilience des populations rurales du département de filingué: cas du village de louma et de damana. Territoires, sociétés et environnement n°005, 115–124.

- Moussa, D. (2007). Reformes foncières et accès des femmes à la terre au Sahel: Quelles stratégies pour les réseaux? Communication présentée à Rome. 15.

- Najros, E. (Edition), (2008). Accès à la terre en milieu rural en Afrique: Stratégies de lutte contre les inégalités de genre. Bruxelles: Atelier FAO-Dimitra. Récupéré de http://www.fao.org/3/a-ak159f.pdf

- Ouedrago, K. (2013). Etude sur la connectivité entre la question foncière et la gestion de l’eau agricole en Afrique occidentale et central. gWA, FAO, IFAD,CILSS, ARID. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/agwa/docs/Connectivity_srtudy_2013.pdf

- Oumarou, A., & Dambo, L. (2017, juin). L’accès des femmes au foncier irrigable, entre défis et contraintes dans la zone d’intervention du PPI Ruwanmu au Niger. In Revue semestrielle de Géographie du Bénin (BenGEO) Université d’Abomey-Calavi N°21 (pp. 73–97). ISSN: 1840-5800.

- République du Niger. (2007). Stratégie de développement accéléré et de réduction de la pauvreté 2008 – 2012 (pp. 133). Niamey, Niger.

- République du Niger, Projet GCP/NER/041/EC. (2007). Recensement General de l’Agriculture et du Cheptel (RGAC 2005/2007), Vol 3, résultats définitifs (volet agriculture) (pp. 112). Niamey, Niger.

- Robert, A. (2011). Femmes, environnement et développement durable: Un lien qui reste à tisser. Essai présenté au Centre Universitaire de Formation en Environnement en vue de l’obtention du grade de maître en environnement (M.Env) (pp. 87). Québec, Canada: Centre universitaire de formation en environnement, Université de Sherbrooke.

- Ubink, J. M., & Amanor, K. S. (Edited by). (2008). Contesting land and custom in Ghana: State, chief and the citizen (pp. 231 p). Nederlands: Leiden University Press.

- Virginie, L. M., Andrew, N., & Emily, W. (2015). Genre et résilience, Document de travail (pp. 88). London.

- Yamba, B. (2017). Evaluation du projet de sécurisation foncière à l’échelle d’un village du département d’Aguié. Coalition internationale pour l’accès à la terre/SPCR Niger. Niamey, Niger.